- 1College of Acupuncture and Tuina, The 3rd Teaching Hospital, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

- 2College of Basic Medicine, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

- 3College of International Education, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

- 4Clinical Research Center for Acupuncture and Moxibustion in Sichuan Province, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

- 5Traditional Chinese Medicine Department, People’s Hospital of Deyang City, Deyang, Sichuan, China

Background: Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is one of the most commonly reported symptoms impacting cancer survivors. This study evaluated and compared the effectiveness and safety of acupuncture treatments for CRF.

Methods: We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, China Biology Medicine China National Knowledge Infrastructure, China Science and Technology Journal Database, and WanFang Database from inception to November 2022 to identify eligible randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing acupuncture treatments with sham interventions, waitlist (WL), or usual care (UC) for CRF treatment. The outcomes included the Cancer Fatigue Scale (CFS) and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and pair-wise and Bayesian network meta-analyses were performed using STATA v17.0.

Results: In total, 34 randomized controlled trials featuring 2632 participants were included. In the network meta-analysis, the primary analysis using CFS illustrated that point application (PA) + UC (standardized mean difference [SMD] = −1.33, 95% CI = −2.02, −0.63) had the highest probability of improving CFS, followed by manual acupuncture (MA) + PA (SMD = −1.21, 95% CI = −2.05, −0.38) and MA + UC (SMD = −0.80, 95% CI = −1.50, −0.09). Moreover, the adverse events of these interventions were acceptable.

Conclusion: This study demonstrated that acupuncture was effective and safe on CRF treatment. However, further studies are still warranted by incorporating more large-scale and high-quality RCTs.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO, identifier CRD42022339769.

Introduction

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is one of the most commonly reported symptoms impacting cancer survivors (1). CRF is estimated to occur in up to 90% of patients with cancer during active treatment and 27%–82% of patients after treatment (2). CRF is a common subjective symptom in patients with cancer that usually manifests as weakness, low endurance, and high energy consumption that cannot be relieved by sleep and rest (3). Differing from general fatigue, CRF is accompanied by a series of painful symptoms such as sleep disorders and mental fatigue that reduce patients’ tolerance, interfere with treatment, and seriously affect the quality of life and survival of patients. The incidence of insomnia in tumor-related diseases ranges from 18% to 68% (4, 5). Psychological pressure and negative emotions can easily cause fatigue symptoms, and the development of fatigue symptoms also aggravate the negative emotions of patients. Therefore, the management of CRF and its common comorbid symptoms (e.g., sleep disturbance) is an urgent issue during cancer treatment.

The etiology of CRF is multifactorial, and it consists of physiological, biochemical, and psychological factors that usually coexist and have additive effects. CRF can be attributed directly to cancer itself as well as its complications, the side effects of treatments, and patients’ comorbidities and psychosocial factors. CRF probably starts in the skeletal muscles because of a progressive reduction of physical activity (sometimes with physical interruption), but the brain is also critical as a central regulator of fatigue perception. A recent review found a positive correlation between fatigue and the circulating levels of inflammatory markers; in particular, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1, and neopterin levels were significantly associated with CRF (1, 6, 7). The complexity of the etiological factors makes CRF difficult to treat. Conventional medical approaches can provide relief for some of the abovementioned symptoms, but often, solutions are limited (8, 9). The lack of proven effective treatments for CRF in conventional medical care leaves this common and distressful illness underreported and undertreated (10).

Acupuncture is widely used in palliative cancer care among Chinese populations. CRF is equivalent to the category of deficiency syndrome in traditional Chinese medicine. It is the main pathogenesis of the insufficiency of Zang-fu organs, qi and blood, Yin and Yang, and exhaustion after long deficiency (11). Numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses (8, 12–14) suggest that acupuncture has clinical applications in the management of CRF. It was reported that acupuncture is commonly used to treat CRF to improve quality of life in patients with cancer (3, 15–25). However, are all types of acupuncture therapy efficacious in treating cancer-related symptoms and which acupuncture therapies provide the greatest efficacy? As an extension of pairwise meta-analysis of two treatments, network meta-analysis has recently attracted many researchers in evidence-based medicine because it simultaneously synthesizes both direct and indirect evidence from multiple treatments and thus facilitates better decision making. The Bayesian hierarchical model is a popular method to implement network meta-analysis, and it is generally considered more powerful than conventional pairwise meta-analysis, leading to more precise effect estimates with narrower credible intervals (26, 27). We conducted a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (3, 16, 19–25, 28–52) to determine the efficacy of acupuncture therapies in CRF.

Methods

The reporting of this Network Meta-analysis follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Network Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement (53, 54).

Protocol and registration

This network meta-analysis was registered on the PROSPERO platform (number: CRD42022339769) and reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis checklist (55).

Eligibility criteria and exclusion criteria

Types of studies

All articles reporting RCTs published in English or Chinese were eligible without any regional and publication restrictions. The first period of the randomized cross-over trials was applied. Conversely, non-randomized clinical studies, quasi-RCTs, cluster RCTs, case reports, and studies for which no data were available were excluded.

Types of participants

Trials enrolling adults with any type of cancer (≥18 years) were eligible. All cancer types were included because we assumed that CRF is a general cancer problem and that the working mechanisms and effects of the different interventions targeting CRF would be similar across all cancer diagnoses.

Types of interventions

Acupuncture therapies were considered, including manual acupuncture (MA), electroacupuncture (EA), point application (PA), acupressure (AU), and transcutaneous electric acupoint stimulation (TEAS).

Types of comparators

The control interventions included conventional treatment, usual care (UC), Chinese medicine (CM), sham acupuncture (SA), waitlist (WL), or no intervention, as well as other techniques. Laser acupuncture, acupoint injection, moxibustion, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation were excluded.

Types of outcome measurements

We included studies that covered at least one of the relevant outcomes. Our network meta-analysis primarily aimed to compare and rank the efficacy of acupuncture methods using the Cancer Fatigue Scale (CFS) and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Using the CFS score, the primary acceptable outcomes were fatigue symptoms, as numerous previous studies reported the use of fatigue scales including the Revised Piper Fatigue Scale (56, 57), Piper Fatigue Scale, Brief Fatigue Inventory (56), and Karnofsky Performance Status (58). We divided fatigue into three levels: mild, 1–3 points; moderate, 4–6 points, and severe, 7–10 points (19). Regarding the secondary outcome, sleep quality was assessed using PSQI before and after the intervention. The 19-item PSQI instrument produces a global sleep quality score and seven specific component scores: quality, latency, duration, disturbance, habitual sleep efficiency, use of sleeping medications, and daytime dysfunction. Global scores range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating worse sleep quality and greater sleep disturbance (59).

Search strategy

Searching strategies

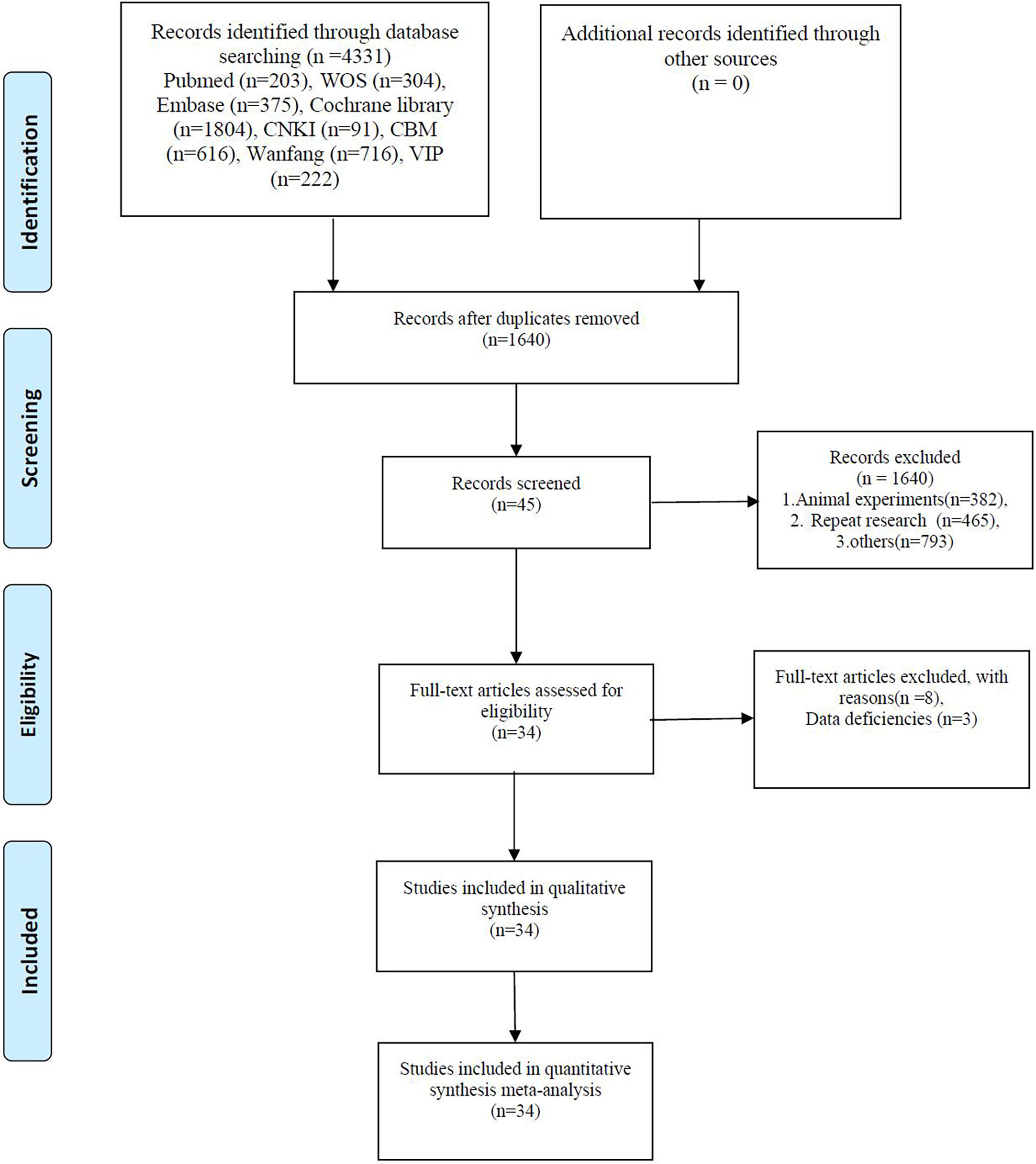

Eight databases, including PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, China Biology Medicine, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and China Science and Technology Journal Database, were used (Figure 1). Databases were systematically searched from inception to November 2022 for correlative RCTs using the following keywords: “cancer related fatigue,” “cancer associated fatigue,” “acupuncture,” “electroacupuncture,” “point application,” “TEAS,” “transcutaneous electric acupoint stimulation,” “electroacupuncture,” “acupressure,” “randomized controlled trials,” and “RCT.” Two reviewers first screened the literature by scanning the titles and abstracts and then read the full text of potentially eligible trials to decide whether they should be included in the meta-analysis. The database search strategy is presented in Appendix Supplementary Materials.

Study selection and data extraction

Data were extracted by two reviewers independently. Disagreements concerning data extraction were resolved by discussion. TH and YHC independently screened titles, abstracts, and keywords to identify duplicate trials and clearly ineligible studies for exclusion. Subsequently, the full text of the studies was examined to ensure that they met the inclusion criteria. Disagreements regarding study eligibility were resolved by a third reviewer.

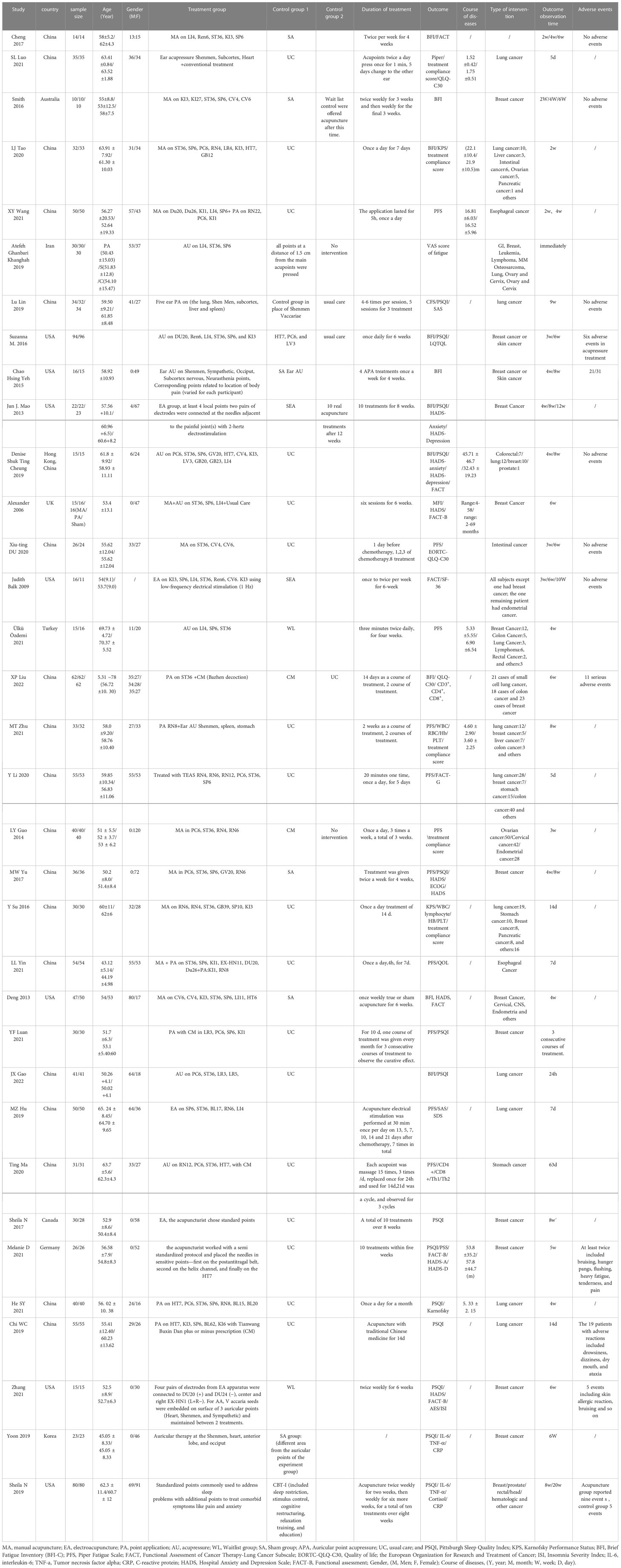

The risk of bias of methodological quality was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias (ROB2) Tool. This tool comprised six parts (randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, selection of the reported result, and overall bias) and ranked the methodological quality as some concerns, low risk, or high risk. A third party (ZW or FL) was consulted to assist in the final decision-making process. The ROB 2 plot was generated using the revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB2).

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

RevMan 5.3 was used to analyze the data. Pre–post differences were used as outcome indicators for each included study. Further, three-arm RCTs were separated into two arms for all possible combinations in the meta-analysis. The fixed-effects model utilized the Mantel–Haenszel procedure; otherwise, the random-effects model adopting the Der Simonian–Laird procedure was used. The I2 statistic and p value were used to identify and measure the heterogeneity among the studies. Low, moderate, and high heterogeneity were indicated by I2 values of <25%, 25%–50%, and >50%, respectively. P ≤ 0.1 was considered indicative of significant heterogeneity (60, 61). All data were analyzed with a 95% confidence interval (CI). We first performed pair-wise meta-analysis, followed by network meta-analysis. Pair-wise meta-analysis compared acupuncture treatment to the control. For continuous data, we calculated the standardized mean difference (SMD) or mean difference (MD) between treatments for CFS and PSQI scores. Cohen benchmarks for interpreting the magnitude of the SMD scores were used, where a result of ≤0.20 is considered a small effect, 0.50 is defined as moderate, and a large effect is >0.80 (62). A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the robustness of the results in CFS and PSQI scores. This step repeated the primary analysis with a modified dataset based on assumptions of quality or study size. This led us to investigate whether these factors might have any effect on the main results. The sensitivity analysis was performed using STATA 17.0 software. The statistical method was used to assess the stability of results from direct comparisons to verify whether the NMA results were reliable.

Publication bias

We generated a funnel plot to provide digital-based modeling of the results and eliminate bias (63).

Quality of evidence

Using Grades of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) (64), the overall quality of evidence was assessed and ranked as high, moderate, low, or critically low.

Results

Selection of eligible studies

After the primary search process, we identified 4331 potentially relevant studies from these databases. After eliminating 465 duplicates as well as animal studies, reviews, and protocols, 45 articles were retained. Following a full-text assessment, 11 articles were excluded, and 34 RCTs were included in this systematic review (65).

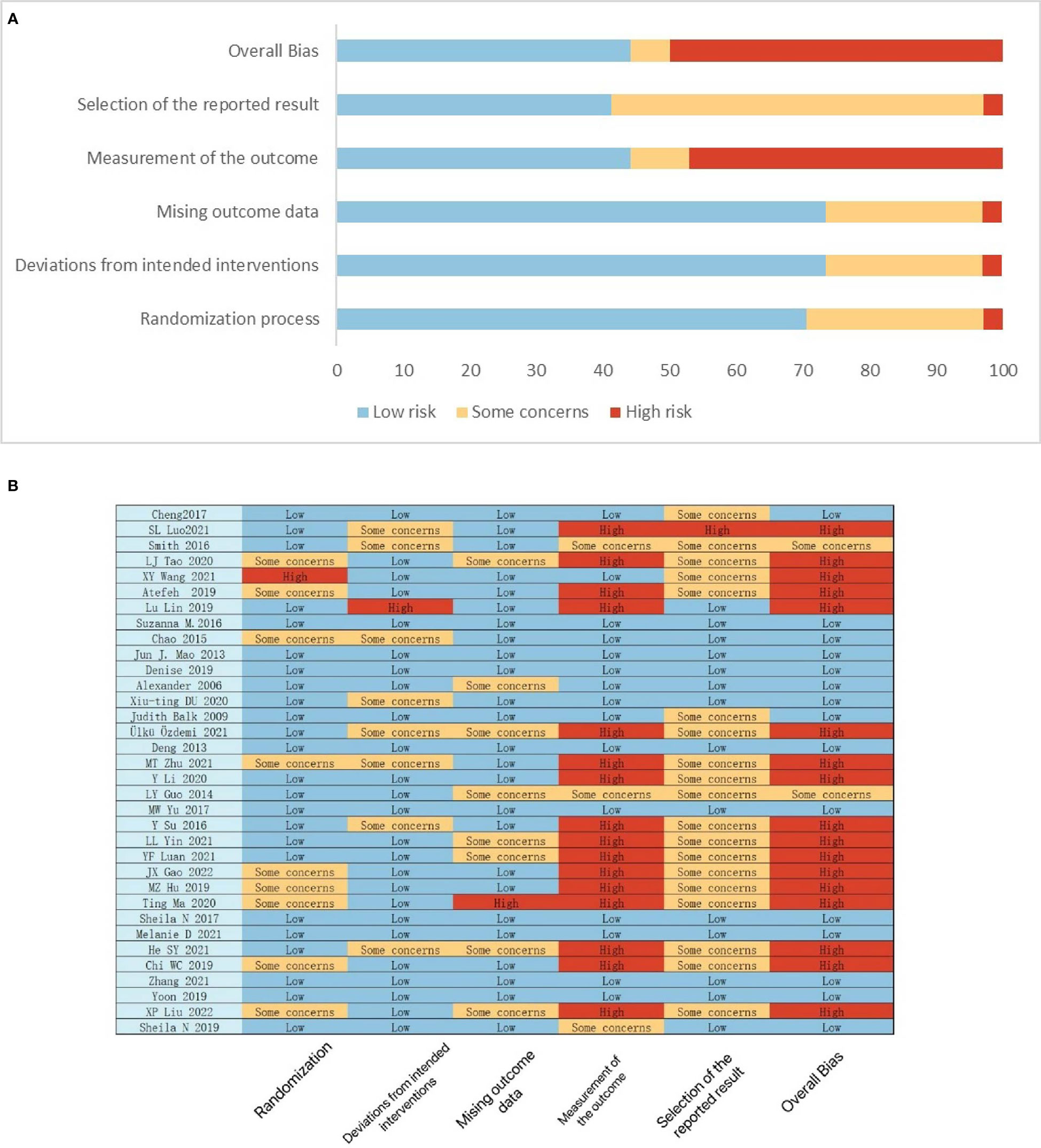

Characteristics of the included studies

Of the studies included in the final Bayesian meta-analysis, 18 RCTs (3, 15, 17, 21, 22, 24, 25, 32, 35–38, 42, 43, 47, 48, 52, 66) were published in Chinese, whereas 16 RCTs (16, 19, 23, 29–31, 34, 39–41, 44–46, 49–51) were written in English. The studies also included four three-arm (40, 42, 43, 48) and 29 two-arm studies. All 34 articles were published between 2006 and 2022, and they included a total of 2632 participants. Among the 34 trials, the mean age of the included patients ranged 43.12–69.73 years. Meanwhile, 33 studies provided details of the treatment acupoints, and all trials described the insertion technique. The interventions in these studies included MA, MA + UC, EA, AU + PA, PA, PA + UC, AU, TEAS, TEAS + UC, and other combinations with UC (including cancer-related drugs, CM, cognitive behavioral therapy, and waitlist [no intervention]). The detailed information of the included studies is presented in Table 1.

Risk of bias among the included RCTs

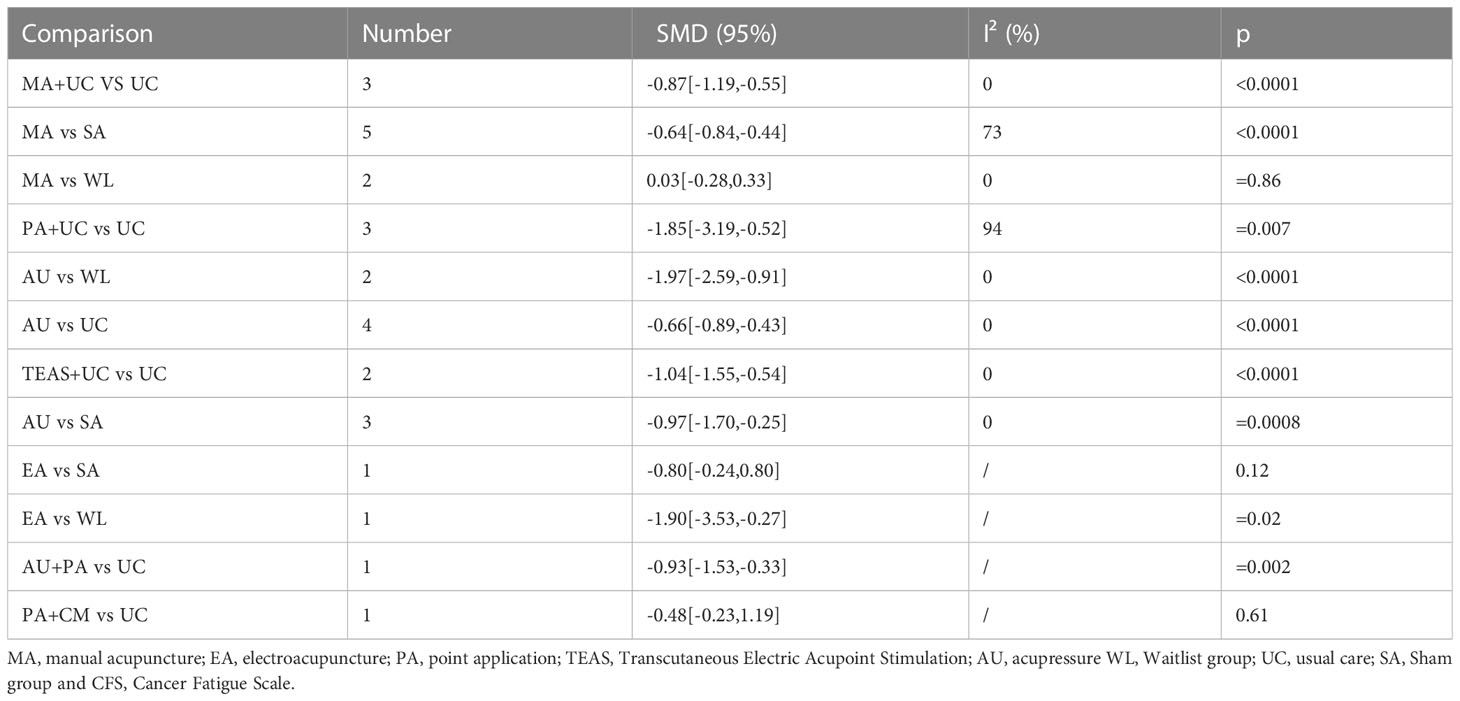

The Cochrane ROB 2 Tool was used to assess the quality of all 34 trials included in our study. According to RoB 2, Two RCTs (40, 48) were rated as having some concerns regarding the risk of bias, and 17 RCTs (16, 20, 23, 24, 29, 31, 34, 37–39, 41, 44, 46, 47, 49–51) were rated as having a high risk of bias. Major sources of concerns include blind method leading to the outcome have been influenced by intervention, and a lack of prospectively developed analysis plans, which could have contributed to possible selection of reported results. The remaining 15 RCTs were rated as having a low risk of bias. SL Luo et al. (16) had a critical risk of measurement of the outcome due to outcome inappropriate. The detailed results of the risk of bias analyses are available in Figure 2.

Results of the comparative effectiveness of the interventions

Pair-wise meta-analysis

Regarding the primary outcome, the meta-analysis revealed that the most commonly compared modalities were MA and SA (n = 5). The analysis found that MA + UC (SMD = −0.87, 95% CI = −1.19, −0.55; I2 = 0), PA + UC (SMD = −1.85, 95% CI = −3.19, −0.52; I2 = 94) and TEAS + UC (SMD = −1.04, 95% CI = −1.55, −0.54; I2 = 0) were showed statistically effect to usual care, the quality of the evidence were low. AU (SMD = −0.66, 95% CI = −0.89, −0.43; I2 = 0), the quality of the evidence was moderate. PA + AU (SMD = −0.93, 95% CI = −1.53, −0.33) were superior to UC, the quality of the evidence was low. Meanwhile, MA (SMD = −0.64, 95% CI = −0.84, −0.44; I2 = 73%) and AU (SMD = −0.97, 95% CI = −1.70, −0.25; I2 = 0) displayed beneficial effects compared with SA, the quality of the evidence was moderate. AU (SMD = −1.97, 95% CI = −2.59, −0.91; I2 = 0) was beneficial compared with WL, the quality of the evidence was moderate. And EA (SMD = −1.90, 95% CI = −3.53, −0.27) were beneficial compared with WL, the quality of the evidence was low. Detailed results are presented in Table 2.

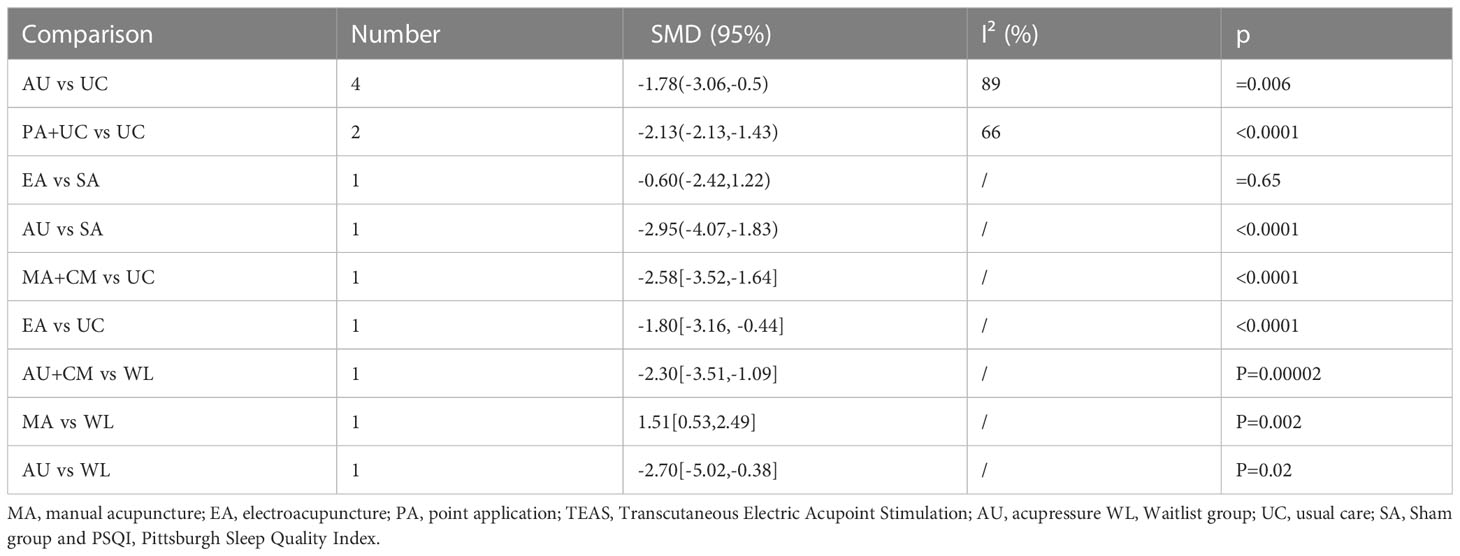

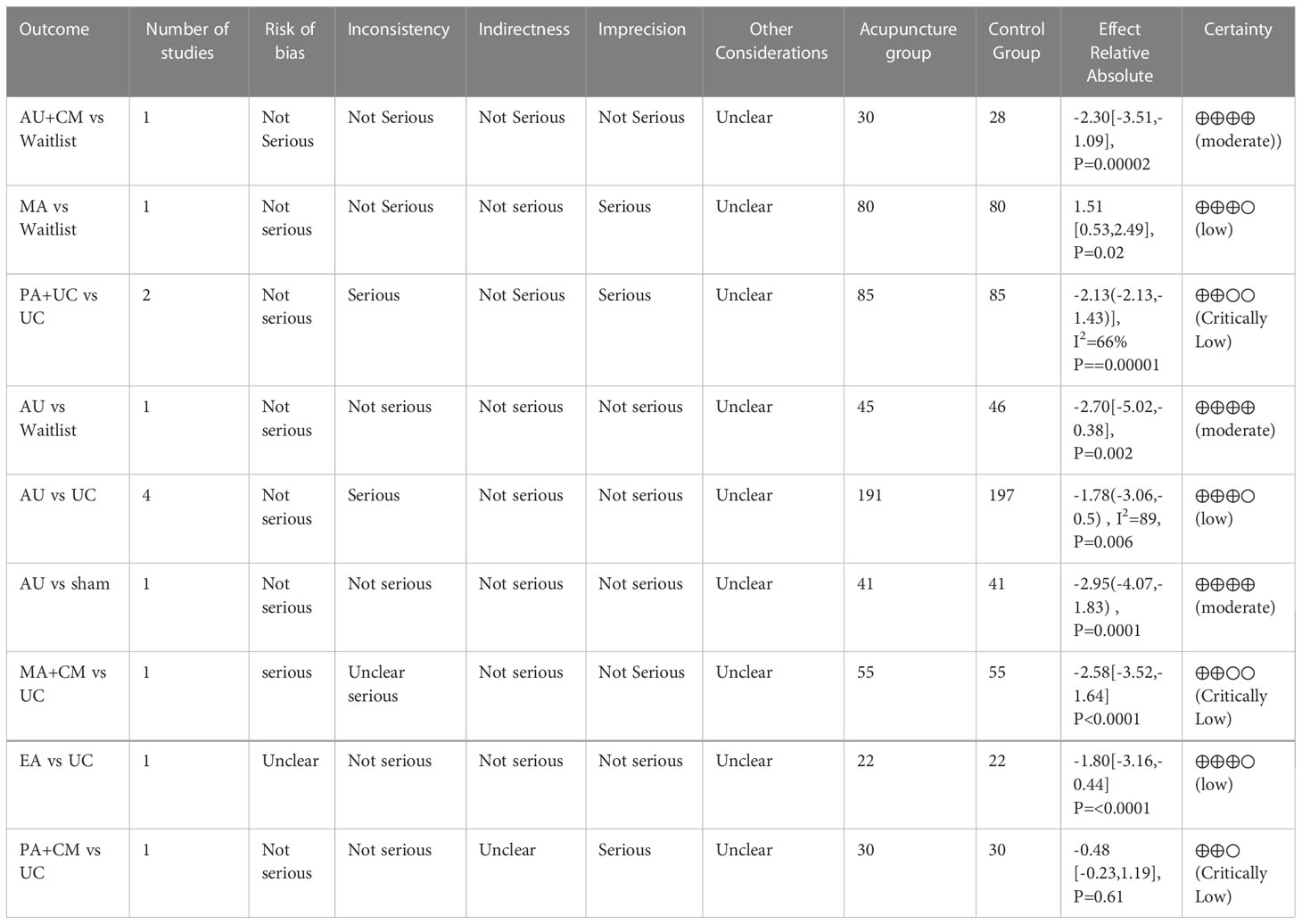

Concerning PSQI, 13 studies compared different interventions. AU (SMD = −1.78, 95% CI = –3.06, −0.5; I2 = 89%), PA + UC (SMD = −2.13, 95% CI = −2.13, −1.43; I2 = 66), MA + CM (SMD = −2.58, 95% CI = −3.52, −1.64) produced significantly better outcomes than UC the quality of the evidence was critically low. And EA (SMD = −1.80, 95% CI = −3.16, −0.44), was showed significantly better outcomes than UC, the quality of the evidence was low. AU (SMD = −2.95, 95% CI, −4.07, −1.83) displayed better efficacy than SA, the quality of the evidence was moderate. AU + CM (SMD = −2.30, 95% CI, −3.51, −1.09) and AU (SMD = −2.70, 95% CI = −5.02, −0.38) produced significantly better outcomes than WL, the quality of the evidence was moderate. No significant differences were noted between EA and SC or between MA and WL. Detailed results are presented in Table 3.

Network meta-analysis

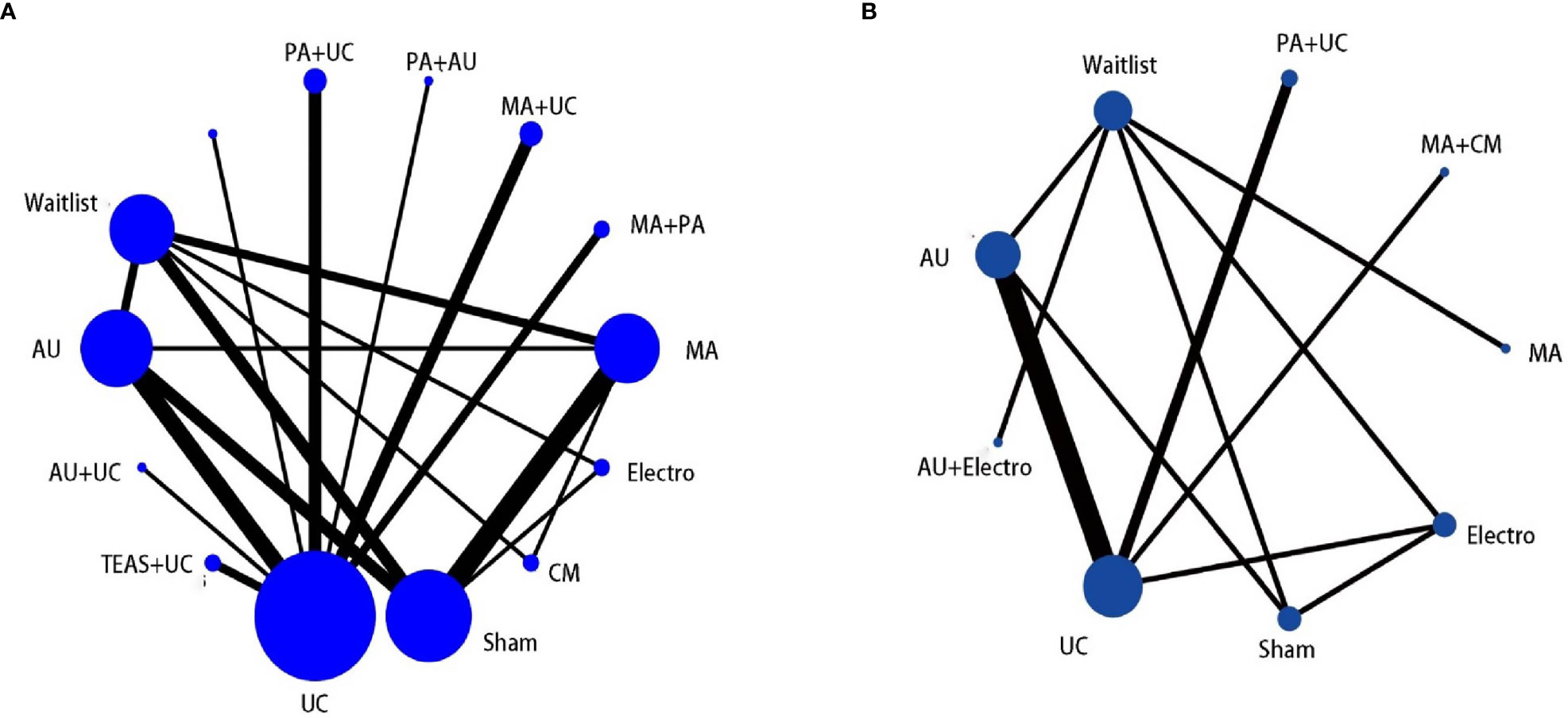

All 34 RCTs were included in this analysis. This study revealed that the most study comparison for CFS was acupuncture versus SA (n = 5), whereas that for PSQI was acupuncture versus UC (n = 4). The network plot is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3 (A) The network graph of different interventions of CFS; (B) The network graph of different interventions of PSQI.

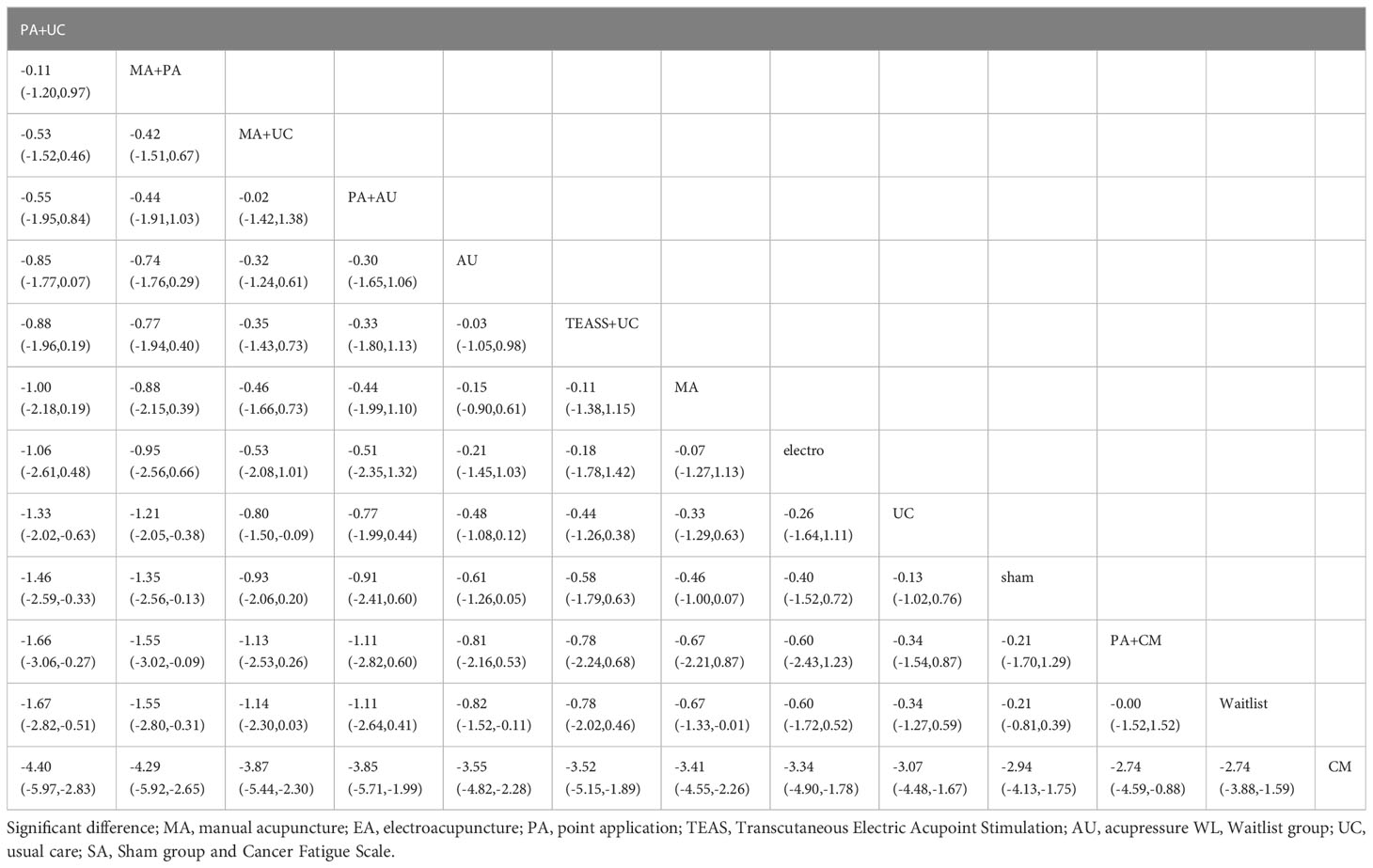

Concerning CSF, the network plot illustrated that the most common comparison was MA and SA (n = 5). The analysis found that PA + UC (SMD = −1.33, 95% CI = −2.02, −0.63), MA + PA (SMD = −1.21, 95% CI = −2.05, −0.38) and MA + UC (SMD = −0.80, 95% CI = −1.50, −0.09) were superior to UC. PA + UC (SMD = −1.46, 95% CI, −2.59, −0.33) and MA + PA (SMD = −1.35, 95% CI, −2.56, −0.13) displayed beneficial effects compared with SA. PA + UC (SMD = −1.67, 95% CI = −2.82, −0.51), MA + PA (SMD = −1.55, 95% CI = −2.80, −0.31), AU (SMD = −0.82, 95% CI, −1.52, −0.11), and MA (SMD = −0.67, 95% CI = −1.33, −0.01) were more beneficial than WL Table 4.

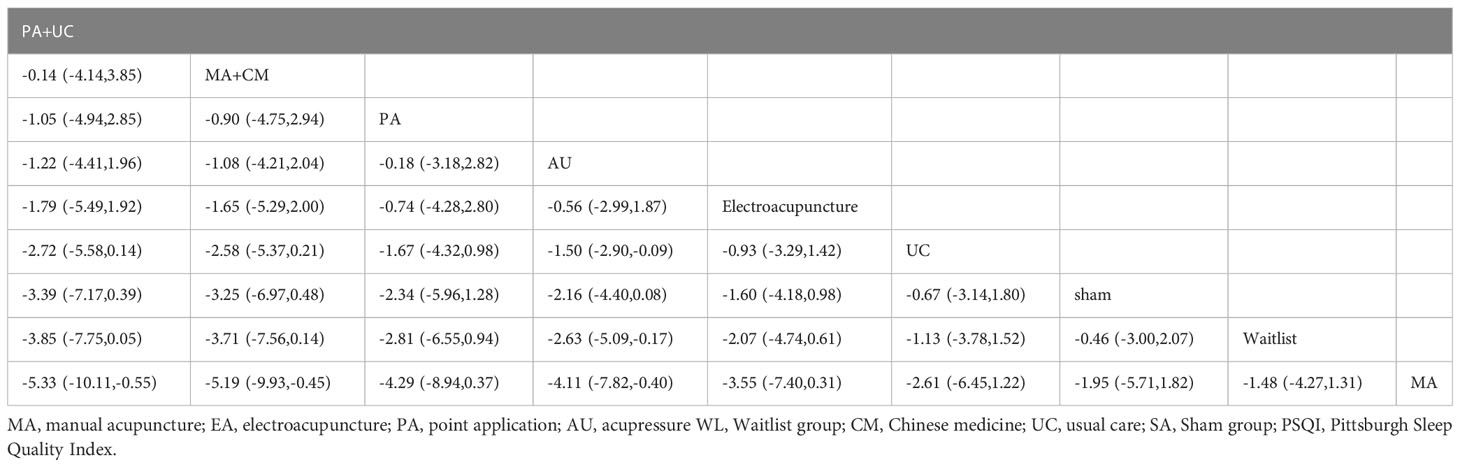

Concerning PSQI, AU was more effective than UC (MD = −1.50, 95% CI = −2.90, −0.09) and WL (MD = −2.63, 95% CI = −5.09, −0.17). Further analysis revealed that PA + UC (MD = −5.33, 95% CI = −10.11, −0.55), MA + CM (MD = −5.19, 95% CI = −9.93, −0.45), and AU (MD = −4.11, 95% CI = −7.82, −0.40) were more beneficial than MA Table 5.

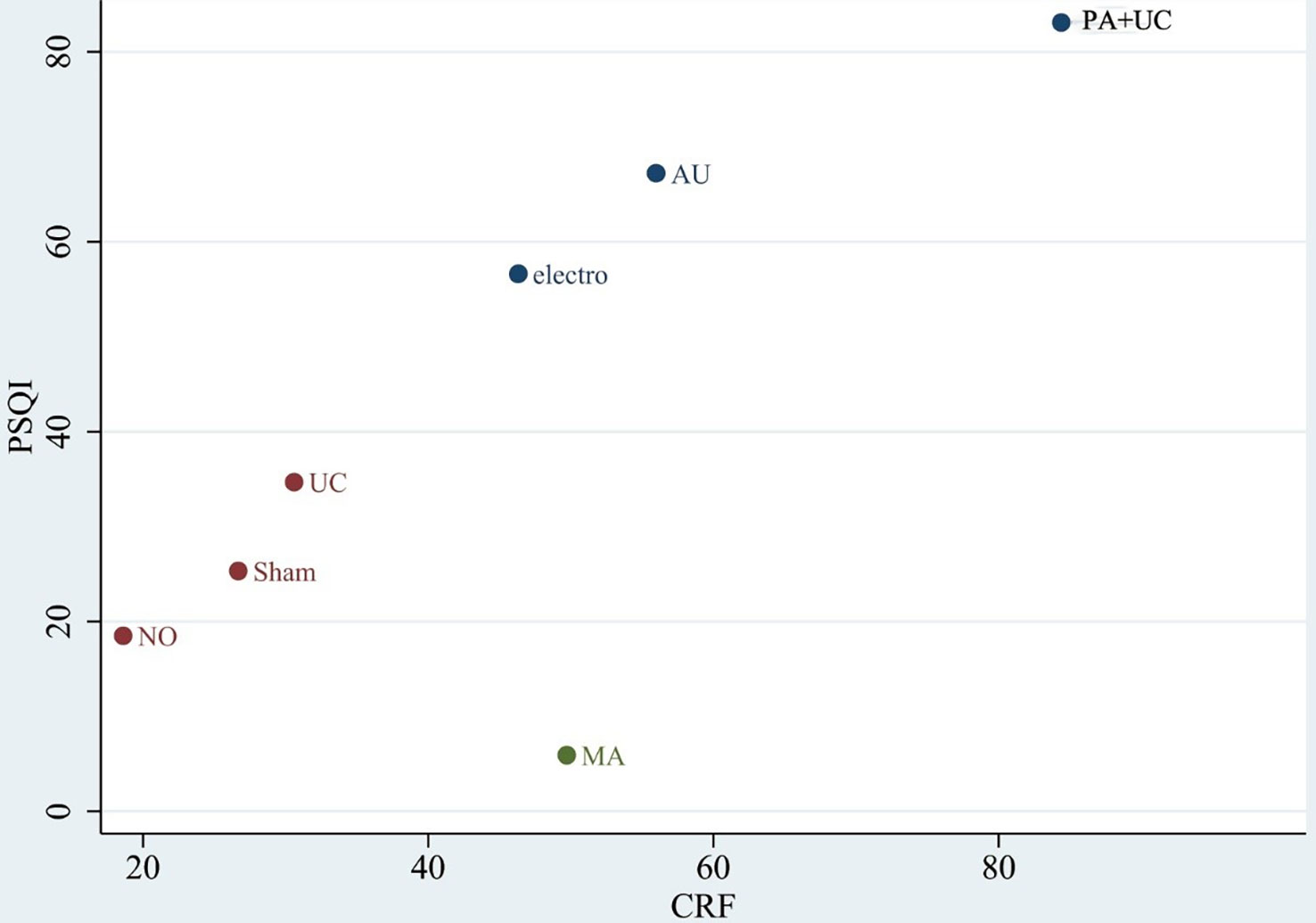

Rank probabilities of the interventions

We performed network meta-analysis using the consistency model, and a ranking probability figure was generated for CFS. Based on the figure, AU + UC, PA + UC, and MA + PA were the three most effective treatment modalities in the analysis. The cumulative SUCRA represents the probability that each intervention ameliorates the symptoms of CRF. This analysis revealed that AU + UC (100%) exhibited the highest probability of relieving CRF symptoms, followed by PA + UC (84.4%), MA + PA (80.6%), MA + UC (66.9%), PA + AU (64.2%), AU (56.0%), TEAS + UC (52.3%), MA (49.7%), EA (46.0%), UC (30.6%), SA (26.4%), PA + CM (23.6%), WL (18.6%), and CM (0.0%) Figure 4A.

Figure 4 (A)The figure of ranking probability of reduction in CFS; (B) The figure of ranking probability of reduction PSQI.

We performed Bayesian analysis via the consistency model, and a ranking probability figure was generated for PSQI. PA + UC, AU, and EA were the three most effective methods in the analysis. Based on the cumulative SUCRA, PA + AU (83.1%) displayed the highest probability of improving PSQI, followed by AU (67.2%), EA (56.6%), UC (34.7%), SA (25.3%), WL (18.5%), and MA (5.9%) Figure 4B.

Safety

Notably, only 13 RCTs described safety data. The therapies included MA, PA, and EA, PA caused bruising and minor comfort skin trauma. Acupuncture caused pain, headache, heavy eyelids, fatigue, and tenderness. These adverse events were acceptable. However, serious events including bronchospasm, low blood counts, renal failure nausea, vomiting, and small bowel obstruction also existed and required additional attention Table 1.

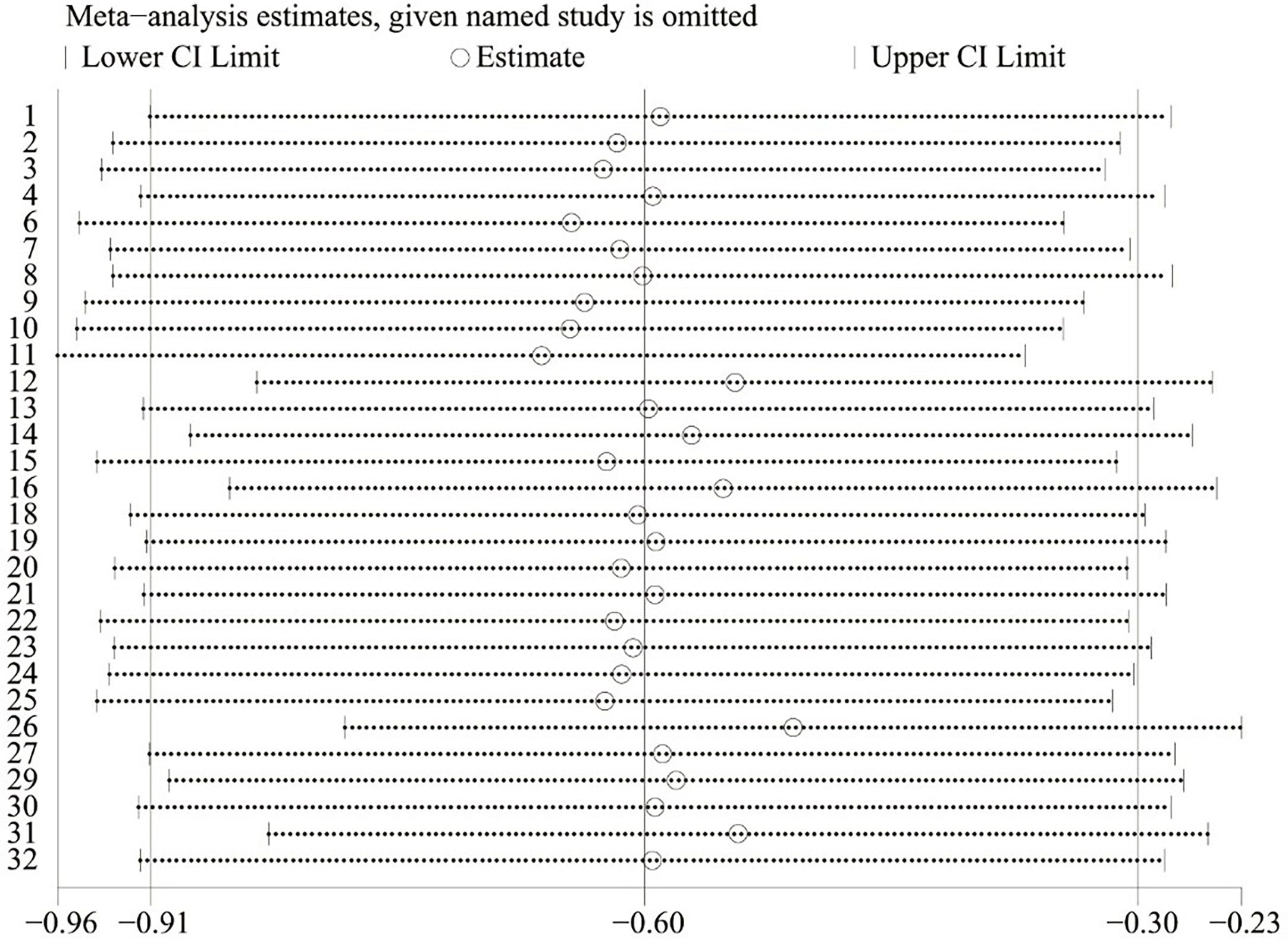

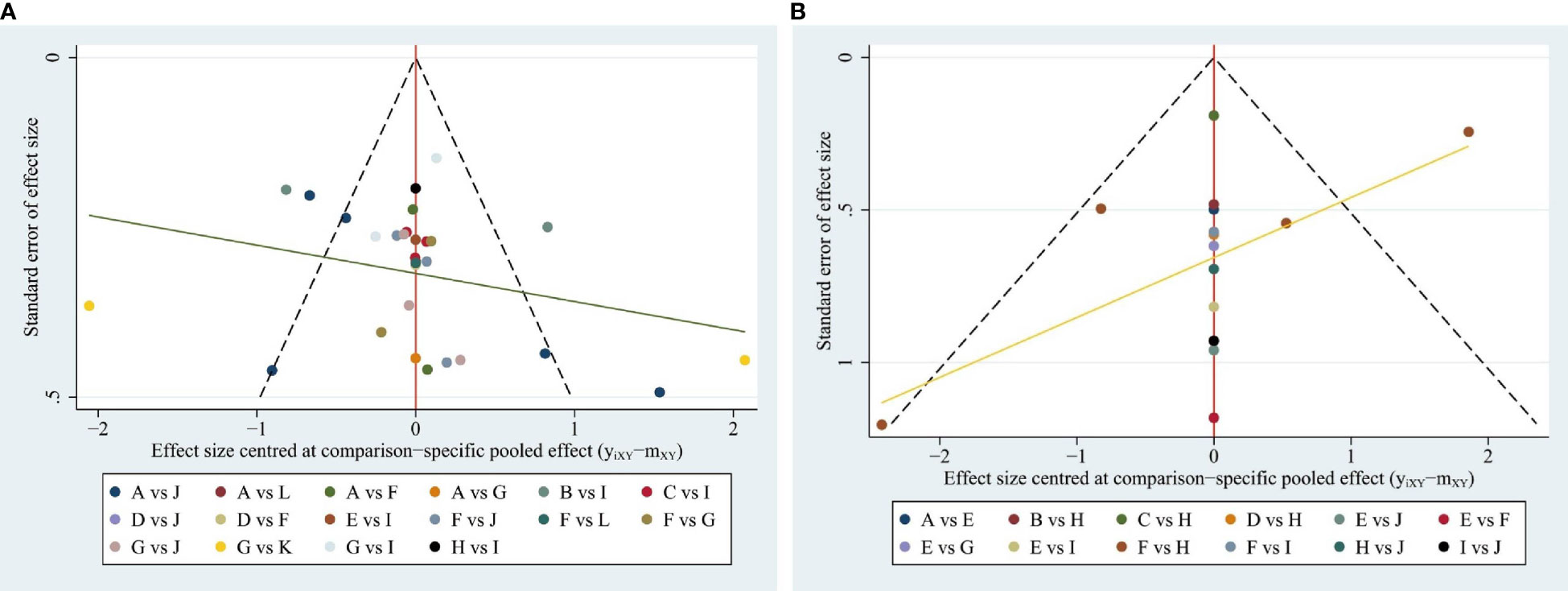

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the results of all included studies in the fatigue scores, and results were less likely to be biased and unreliable Figure 5.

Cluster ranking plot of different treatments

The clustered ranking plot was based on cluster analysis of SUCRA for CFS and PSQI. Seven interventions with data for CFS and PSQI were analyzed. The results illustrated that PA + UC was most effective in improving both CFS and PSQI Figure 6.

Figure 6 Clustered ranking plot. The plot is based on cluster analysis of surface under the cumulative ranking curves (SUCRA) values. Each plot shows the SUCRA values for two outcomes CFS: Cancer Fatigue Scale (CFS) and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).

Publication bias

Publication bias was evaluated by comparing the symmetry of the funnel plot. As presented in Figure 7. The figure demonstrated a decreased likelihood of small sample effects. However, there was no strong and powerful evidence of these small study effects across the outcomes. To determine whether potential publication bias existed in the reviewed literature, Egger’s test was also carried out. The results of Egger’s test (P = 0.910) demonstrated no small-study effects and bias concerning fatigue scores (67, 68).

Figure 7 (A) Funnel plot for the network meta-analysis in CFS; (B) Funnel plot for the network meta-analysis in PSQI.

Quality of evidence

According to the GRADE tool, the quality of the two outcomes (CFS and PSQI) was moderately to critically low. Because of risks of bias, inconsistency, and imprecision, most evidence was rated low Tables 6, 7.

Discussion

As it includes physical, mental, and emotional aspects, CRF is a multidimensional illness, and it can significantly affect patients’ lives. Approximately one-third of women experience moderate-to-severe persistent fatigue up to 10 years after the end of cancer treatment (69, 70). Additionally, persistent fatigue is associated with higher rates of poor sleep (70), and approximately 40%–70% of breast cancer survivors report sleep problems years after their diagnoses (71–73). These studies provided a mechanistic basis for the efficacy of acupuncture against CRF. Numerous studies found that the symptoms of fatigue (18, 42, 43, 47) and poor sleep (32, 52, 66) were alleviated by acupuncture. However, acupuncture therapies are complex, requiring significant manpower and high expenditures. Therefore, this network meta-analysis aimed to identify the optimal acupuncture therapy for patients with cancer using the most comprehensive information.

Recently, complementary approaches such as acupuncture have been increasingly scrutinized as alternate strategies for cancer-related symptom management. Acupuncture is recommended by National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, especially for patients who have finished anticancer treatment and are defined as cancer survivors. Its efficacy and safety have been tested in a number of RCTs (74–76). Among the 34 trials included in this study, ST36 (stomach meridian), KI3, SP6 (convergent acupoint of the liver, spleen, and kidney Yin channels), and energy-associated points (77) including LI4 and DU20 can be considered the core acupoint combinations for treating CRF. In traditional Chinese medicine theory, blockages in the body’s life energy (Qi) are believed to be responsible for illness and disease (14). One study (78) found that acupuncture might alleviate fatigue by influencing neuter regulation, endocrine regulation, immune regulation, rhythm regulation, and other aspects of cancer fatigue (79).

This meta-analysis of the efficacy of different acupuncture treatments for CRF yielded reliable results. First, in the pair-wise meta-analysis, EA, AU displayed significantly better efficacy in improving CRF than WL. In addition, MA + UC, PA + UC, AU, TEAS + UC, and AU + PA had better efficacy than UC. Meanwhile, concerning sleep quality, AU, PA + UC, MA + CM, and EA displayed better efficacy than UC. Moreover, the network Bayesian meta-analysis indicated that PA + UC was a more optimal treatment than CM and MA for improving CFS and PSQI scores. Moreover, 13 trials reported the adverse events. Six studies recorded no adverse events. One study (22) reported serious events (including bronchospasm, low blood counts, and renal failure). Six studies reported mild acupuncture-related adverse events (e.g., pain, bruising, tenderness). In addition, this network meta-analysis had several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, it was the first network meta-analysis to evaluate and compare several different acupuncture therapies for the treatment of CRF. The SUCRA were utilized in this study to evaluate changes in CRF and sleep quality following various acupuncture treatments.

However, the study also included some limitations. First, the search language was limited to Chinese and English, which might inevitably cause bias. Second, some interventions included were poorly studied, which might lead to insufficient statistical efficiency. Third, we evaluated which acupuncture procedures would be the best alternative to conventional treatment, and the types of Western drugs and routine rehabilitation exercise were not studied separately. This was mainly because of the multitude of such treatments and their applications. These issues will be the focus of future studies. Fourth, the GRADE tool determined that the overall quality of evidence obtained from included studies was low. Fifth, considerable heterogeneity was noted in certain outcomes of pair-wise meta-analysis and might be attributed to the clinical, statistical, and methodological differences. Subgroup analysis was infeasible due to the insufficient number of studies included, and sensitivity analysis confirmed the reliability of the results.

Given that the reported outcomes of this study were subjective symptom scores, blinding of outcomes evaluators should be applied in RCTs to reduce bias and increase the reliability of the results. The RCT methodology of the included studies was generally poor because most of the risk items were unclear, particularly allocation concealment and blinding. In the future, we recommend researchers follow the CONSORT reporting statement to improve reporting quality. In addition, we recommend that the protocols should be registered.

Conclusion

This Bayesian network meta-analysis demonstrated that acupuncture was an effective and safe strategy for alleviating cancer-related fatigue. However, due to the undesirable heterogeneity and quality of the included RCTs, the results should be interpreted with caution. Further studies are warranted by incorporating more large-scale and high-quality RCTs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

HT and YHC designed the search strategy. GXX, MSS and CYY performed the literature search. HT and LYH screened the studies for eligibility and wrote the first draft the manuscript. CYY, QL, and LYH performed the data extractions. HT, LYH, CYY conducted the statistical analyses. ZW, LZ and FRL were responsible for the manuscript editing and review of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from Key Research Program of Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (Nos. 2021YFS0087 and 2021ZYD0103).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2023.1071326/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Bower JE. Cancer-related fatigue–mechanisms, risk factors, and treatments. Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2014) 11(10):597–609. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.127

2. Kirshbaum M. Cancer-related fatigue: a review of nursing interventions. Br J Community Nurs (2010) 15(5):214–6, 218-9. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2010.15.5.47945

3. Zick SM, Sen A, Wyatt GK, Murphy SL, Arnedt JT, Harris RE. Investigation of 2 types of self-administered acupressure for persistent cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer survivors: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol (2016) 2(11):1470–6. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1867

4. Li J, Zhu C, Liu C, Su Y, Peng X, Hu X. Effectiveness of eHealth interventions for cancer-related pain, fatigue, and sleep disorders in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Nurs Scholarsh (2022) 54(2):184–90. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12729

5. Zhou ES, Partridge AH, Syrjala KL, Michaud AL, Recklitis CJ. Evaluation and treatment of insomnia in adult cancer survivorship programs. J Cancer Surviv (2017) 11(1):74–9. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0564-1

6. Morrow GR. Cancer-related fatigue: causes, consequences, and management. Oncologist (2007) 12 Suppl 1:1–3. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-1

7. Ryan JL, Carroll JK, Ryan EP, Mustian KM, Fiscella K, Morrow GR. Mechanisms of cancer-related fatigue. Oncologist (2007) 12 Suppl 1:22–34. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-22

8. Finnegan-John J, Molassiotis A, Richardson A, Ream E. A systematic review of complementary and alternative medicine interventions for the management of cancer-related fatigue. Integr Cancer Ther (2013) 12(4):276–90. doi: 10.1177/1534735413485816

9. Mustian KM, Alfano CM, Heckler C, Kleckner AS, Kleckner IR, Leach CR, et al. Comparison of pharmaceutical, psychological, and exercise treatments for cancer-related fatigue: A meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol (2017) 3(7):961–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6914

10. David A, Hausner D, Frenkel M. Cancer-related fatigue-is there a role for complementary and integrative medicine? Curr Oncol Rep (2021) 23(12):145. doi: 10.1007/s11912-021-01135-6

11. Wang L, Xie Z, Wu X, Lv Q. Clinical observation of TCM syndrome differentiation on treatment of cancer-related fatigue in patients with breast cancer. China J Traditional Chin Med Pharm (2016) 12(31):5375–8.

12. Jang A, Brown C, Lamoury G, Morgia M, Boyle F, Marr I, et al. The effects of acupuncture on cancer-related fatigue: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Integr Cancer Ther (2020) 19:1534735420949679. doi: 10.1177/1534735420949679

13. Posadzki P, Moon TW, Choi TY, Park TY, Lee MS, Ernst E. Acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Support Care Canc (2013) 21(7):2067–73. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1765-z

14. Tao WW, Jiang H, Tao XM, Jiang P, Sha LY, Sun XC. Effects of acupuncture, tuina, tai chi, qigong, and traditional Chinese medicine five-element music therapy on symptom management and quality of life for cancer patients: A meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage (2016) 51(4):728–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.11.027

15. Cheng CS, Chen LY, Ning ZY, Zhang CY, Chen H, Chen Z, et al. Acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue in lung cancer patients: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. Supportive Care Cancer: Off J Multinat Assoc Supportive Care Canc (2017) 25(12):3807–14. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3812-7

16. Luo S, Liu Q, Wen R, Ge Y. Effect of evidence-based nursing combined with auricular point and finger pressure on cancer-related fatigue in patients with lung cancer undergoing radiotherapy. Chin Med Modern Distance Educ of China (2021) 19(24):145–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-2779.2021.24.055

17. Cheung DST, Yeung WF, Chau PH, Lam TC, Yang M, Lai K, et al. Patient-centred, self-administered acupressure for Chinese advanced cancer patients experiencing fatigue and co-occurring symptoms: A pilot randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) (2020) 00:e13314. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13314

18. Molassiotis A, Bardy J, Finnegan-John J, Mackereth P, Ryder WD, Filshie J, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of acupuncture self-needling as maintenance therapy for cancer-related fatigue after therapist-delivered acupuncture. Ann Oncol (2013) 24(6):1645–52. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt034

19. Du XT, Tian W, Liu B, Li. Prevention and treatment of acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue caused by chemotherapy of intestinal cancer: A randomize d controlle d trial. World J Acupuncture-Moxibustion (2021) 31(02):83–8.

20. Liu X, Li X, Chen X, Gao W. Bazhen decoction combined with acupoint application in the treatment of cancer-related fatigue. Chin J Clin Oncol Rehabil (2022) 29(03):328–32. doi: 10.13455/j.cnki.cjcor.2022.03.18.

21. Yeh CH, Chien LC, Lin WC, Bovbjerg DH, van Londen GJ. Pilot randomized controlled trial of auricular point acupressure to manage symptom clusters of pain, fatigue, and disturbed sleep in breast cancer patients. Cancer Nursing (2016) 39(5):402–10. doi: 10.1097/ncc.0000000000000303

22. Deng G, Chan Y, Sjoberg D, Vickers A, Yeung KS, Kris M, et al. Acupuncture for the treatment of post-chemotherapy chronic fatigue: a randomized, blinded, sham-controlled trial. Support Care Canc (2013) 21(6):1735–41. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1720-z

23. Yin L, Chen J, Qi Y, Zhang R. Effect of acupuncture combined with acupoint application on swallowing function and cancer-related fatigue of advanced esophageal cancer patients. J Esophageal Dis (2021) 3(03):218–21. doi: 10.15926/j.cnki.issn2096-7381.2021.03.014

24. Li Y, Zhang H, Liu Z, Hu L, Liu H, Yuan L, et al. Clinical effect of transcutaneous electric acupoint stimulation in the treatment of cancer-related fatigue after chemotherapy. China Med Herald (2020) 17(12):149–68.

25. Zhang J, Qin Z, So TH, Chen H, Lam WL, Yam LL, et al. Electroacupuncture plus auricular acupressure for chemotherapy-associated insomnia in breast cancer patients: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Integr Cancer Ther (2021) 20:15347354211019103. doi: 10.1177/15347354211019103

26. Lin L, Chu H, Hodges JS. On evidence cycles in network meta-analysis. Stat Interface (2020) 13(4):425–36. doi: 10.4310/sii.2020.v13.n4.a1

27. Rucker G, Petropoulou M, Schwarzer G. Network meta-analysis of multicomponent interventions. Biom J (2020) 62(3):808–21. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201800167

28. Cheung DST, Yeung WF, Chau PH, Lam TC, Yang M, Lai K, et al. Patient-centred, self-administered acupressure for Chinese advanced cancer patients experiencing fatigue and co-occurring symptoms: A pilot randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) (2022) 31(5):e13314. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13314

29. Chi W, Wang B, Yang F, Jiang Q, Jiang J. Clinical effect of acupuncture combined with medicine in the treatment of insomnia caused by cancer in patients with non-small cell lung cancer after chemotherapy. China Med Herald (2019) 16(23):114–7.

30. Huang F, Zhao Y. Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation for cancer-related fatigue : Randomized controlled trial. Chin J Rehabil Med (2019) 34(06):688–92.

31. Gao J, Zhang L. Influence of TCM emotional nursing combined with acupoint massage on sleep quality and cancer-related fatigue in chemotherapy patients with lung cancer. Clin Med Engineering (2022) 29(01):125–6. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4659.2022.01.0125

32. Garland SN, Xie SX, Li Q, Seluzicki C, Basal C, Mao JJ. Comparative effectiveness of electro-acupuncture versus gabapentin for sleep disturbances in breast cancer survivors with hot flashes: a randomized trial. Menopause (2017) 24(5):517–23. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000779

33. Halpin DMG, Criner GJ, Papi A, Singh D, Anzueto A, Martinez FJ, et al. Global initiative for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease. the 2020 GOLD science committee report on COVID-19 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2021) 203(1):24–36. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202009-3533SO

34. He S. Clinical observation of Chinese medicine acupoint application in the treatment of cancer induced insomnia in patients with lung cancer chemotherapy. Chin J Traditional Med Sci Technol (2021) 28(02):281–3.

35. Hoxtermann MD, Buner K, Haller H, Kohl W, Dobos G, Reinisch M, et al. Efficacy and safety of auricular acupuncture for the treatment of insomnia in breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Cancers (Basel) (2021) 13(16):2–16. doi: 10.3390/cancers13164082

36. Balk J, Day R, Rosenzweig M, Beriwal S. Pilot, randomized, modified, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue. J Soc Integr Oncol (2009) 7(1):1–11.

37. Khanghah AG, Rizi MS, Nabi BN, Adib M, Leili EKN. Effects of acupressure on fatigue in patients with cancer who underwent chemotherapy. J acupuncture meridian Stud (2019) 12(4):103–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jams.2019.07.003

38. Lin L, Zhang Y, Qian HY, Xu JL, Xie CY, Dong B, et al. Auricular acupressure for cancer-related fatigue during lung cancer chemotherapy: a randomised trial. BMJ Support Palliat Care (2021) 11(1):32–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-001937

39. Tao L, Lu D, Liu T, Chen F, Du J. Clinical study of needling fatigue group points in treating cancer related fatigue of qi and blood deficiency. J Clin Acupuncture Moxibustion. (2020) 36(08):4–8.

40. Guo SL LY, Peng Y, et al. Effect of acupuncture therapy on cancer related fatigue of patients with gynecological malignant tumor after chemotherapy. J Clin Acupuncture Moxibustion (2014) 30(06):67–70.

41. Ma T, Wang P, Zhu J, Wang S, Chu J, Song C, et al. Effect of xingjian decoction combined with acupoint application on cancer fatigue of advanced gastric cancer the effect on the immune function of patients. Shaanxi J Traditional Chin Med (2020) 10(41):1410–3. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-7369.2020.10.019

42. Mao JJ, Farrar JT, Bruner D, Zee J, Bowman M, Seluzicki C, et al. Electroacupuncture for fatigue, sleep, and psychological distress in breast cancer patients with aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia: A randomized trial. Cancer (2014) 120(23):3744–51. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28917

43. Molassiotis A, Sylt P, Diggins H. The management of cancer-related fatigue after chemotherapy with acupuncture and acupressure: a randomised controlled trial. Complement Ther Med (2007) 15(4):228–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2006.09.009

44. Zhu M, Chu Z, Huang J, Wen T, Huang J, Ma J. Evaluation of the clinical efficacy of topical application of shiquan DabuJiawei formula at the navel and acupressure with magnetic ear beads for cancer-related fatigue. Modern Chin Clin Med (2021) 28(01):1–6.

45. Yu M, Li D, Yang G, Xu Y, Wang X. Effects of acupuncture on cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer patients at the rehabilitation stage: A randomized controlled trial. China Med Herald (2017) 14(19):89–93.

46. Hu M, Zhao J, Gu D, Xu Y, Yan X. Effect of percutaneous acupoint electrical stimulation combined with emotional Release therapy on patients with lung cancer chemotherapy. J Qilu Nurs (2019) 25(19):31–3. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-7256.2019.19.009

47. Ozdemir U, Tasci S. Acupressure for cancer-related fatigue in elderly cancer patients: A randomized controlled study. Altern Ther Health Med (2021).

48. Smith C, Carmady B, Thornton C, Perz J, Ussher JM. The effect of acupuncture on post-cancer fatigue and well-being for women recovering from breast cancer: A pilot randomised controlled trial. Acupunct Med (2013) 31(1):9–15. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2012-010228

49. Wang XY. Effects of acupoint application combined with acupuncture and moxibustion on swallowing function and cancer-related fatigue in patients with advanced esophageal cancer. Chin J Mod Nurs (2021) 27(13):1784–8.

50. Su YZ, Xia LM. Clinical study on acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue due to spleen-kidney deficiency. Shanghai J Acu-mox (2016) 35(07):830–2. doi: 10.13460/j.issn.1005-0957.2016.07.0830

51. Luan Y, Zhang Y, Pan J, Yang X. Clinical observation on improving cancer-induced fatigue of patients with liver qi stagnation type breast cancer by applying shu mediation yu anshen prescription at acupoint. Yunnan J Traditional Chin Med Materia Med (2021) 42(09):62–5. doi: 10.16254/j.cnki.53-1120/r.2021.09.020. Yang YLYZJPX.

52. Yoon HG, Park H. The effect of auricular acupressure on sleep in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: A single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Appl Nurs Res (2019) 48:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2019.05.009

53. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (2021), 1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

54. Sonbol MB, Riaz IB, Naqvi SAA, Almquist DR, Mina S, Almasri J, et al. Systemic therapy and sequencing options in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol (2020) 6(12):e204930. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.4930

55. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (2011) 343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928

56. Jiang XJ, Yang XY, Xue X, Xu C, Yang X, Liu K, et al. Research progress on assessment tools and evaluation indexes of cancer-induced fatigue. Chin J Nurs (2012) 47(09):859–61.

57. Reeve BB, Stover AM, Alfano CM, Smith AW, Ballard-Barbash R, Bernstein L, et al. The piper fatigue scale-12 (PFS-12): psychometric findings and item reduction in a cohort of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2012) 136(1):9–20. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2212-4

58. Xue X, Xu C, Yang X, Liu K, Zhang J, Chu L, et al. An analysis on KPS score for chemotherapy patients with cancer in liaoning province. China Cancer (2013) 22(08):635–7. doi: 10.11735/j.issn.1004-0242.2013.08.A0

59. Huang Y, Zhu M. Increased global PSQI score is associated with depressive symptoms in an adult population from the united states. Nat Sci Sleep (2020) 12:487–95. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S256625

60. Li HT, Zhou YB, Liu JM. The impact of cesarean section on offspring overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond). (2013) 37(7):893–9. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.195

61. The Cochrane Collaboration. The cochrane collaboration, cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. London, UK: The UK Cochrane Centre, United Kingdom (2011).

63. Salanti G, Ades AE, Ioannidis JP. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol (2011) 64(2):163–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.016

64. Puhan MA, Schunemann HJ, Murad MH, Li T, Brignardello-Petersen R, Singh JA, et al. A GRADE working group approach for rating the quality of treatment effect estimates from network meta-analysis. BMJ (2014) 349:g5630. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5630

65. Hua Z, Zhai F, Tian J, Gao C, Xu P, Zhang F, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral Chinese patent medicines as adjuvant treatment for unstable angina pectoris on the national essential drugs list of China: A protocol for a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Open (2019) 9(9):e026136. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026136

66. Garland SN, Xie SX, DuHamel K, Bao T, Li Q, Barg FK, et al. Acupuncture versus cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in cancer survivors: A randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst (2019) 111(12):1323–31. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz050

67. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (1997) 315(7109):629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

68. Salanti G, Ades AE, Ioannidis JPA. Using network meta-analysis to evaluate the existence of small-study effects in a network of interventions. Res Synth Methods (2012) 3(2):161–76. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.57

69. Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Bernaards C, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, et al. Fatigue in long-term breast carcinoma survivors: A longitudinal investigation. Cancer (2006) 106(4):751–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21671

70. Minton O, Stone P. How common is fatigue in disease-free breast cancer survivors? A systematic review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2008) 112(1):5–13. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9831-1

71. Haidinger R, Bauerfeind I. Long-term side effects of adjuvant therapy in primary breast cancer patients: Results of a web-based survey. Breast Care (Basel) (2019) 14(2):111–6. doi: 10.1159/000497233

72. Savard J, Ivers H, Villa J, Caplette-Gingras A, Morin CM. Natural course of insomnia comorbid with cancer: an 18-month longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol (2011) 29(26):3580–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.2247

73. Schmidt ME, Wiskemann J, Steindorf K. Quality of life, problems, and needs of disease-free breast cancer survivors 5 years after diagnosis. Qual Life Res (2018) 27(8):2077–86. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1866-8

74. Hilfiker R, Meichtry A, Eicher M, Nilsson Balfe L, Knols RH, Verra ML, et al. Exercise and other non-pharmaceutical interventions for cancer-related fatigue in patients during or after cancer treatment: A systematic review incorporating an indirect-comparisons meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med (2018) 52(10):651–8. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096422

75. Lau CHY, Wu X, Chung VCH, Liu X, Hui EP, Cramer H, et al. Acupuncture and related therapies for symptom management in palliative cancer care: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Med (Baltimore) (2016) 95(9):e2901. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002901

76. MacPherson H, Thomas K, Walters S, Fitter M. The York acupuncture safety study: prospective survey of 34 000 treatments by traditional acupuncturists. BMJ (2001) 323(7311):486–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7311.486

77. XN. Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion (Third Edition 2010) by Xinnong Cheng. Beijing: Foreign Language Press (2009).

78. Su CX, Wang LQ, Grant SJ, Liu JP. Chinese Herbal medicine for cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Complement Ther Med (2014) 22(3):567–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2014.04.007

Keywords: acupuncture, acupuncture therapy, cancer-related fatigue, network meta-analysis, systematic review

Citation: Tian H, Chen Y, Sun M, Huang L, Xu G, Yang C, Luo Q, Zhao L, Wei Z and Liang F (2023) Acupuncture therapies for cancer-related fatigue: A Bayesian network meta-analysis and systematic review. Front. Oncol. 13:1071326. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1071326

Received: 16 October 2022; Accepted: 21 February 2023;

Published: 27 March 2023.

Edited by:

Ye Yang, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, ChinaReviewed by:

I-Shiang Tzeng, National Taipei University, TaiwanLuwen Zhu, Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine, China

Copyright © 2023 Tian, Chen, Sun, Huang, Xu, Yang, Luo, Zhao, Wei and Liang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ling Zhao, emhhb2xpbmdAY2R1dGNtLmVkdS5jbg==; Zheng Wei, d2Vpemhlbmc0MjVAMTI2LmNvbQ==; Fanrong Liang, YWN1cmVzZWFyY2hAMTI2LmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Hao Tian

Hao Tian Yunhui Chen

Yunhui Chen Mingsheng Sun1,2,3

Mingsheng Sun1,2,3 Liuyang Huang

Liuyang Huang Guixing Xu

Guixing Xu Fanrong Liang

Fanrong Liang