94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CASE REPORT article

Front. Oncol., 28 April 2023

Sec. Head and Neck Cancer

Volume 13 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1024908

Yu Zhang1,2†

Yu Zhang1,2† Bei Lin2†

Bei Lin2† Kai-ning Lu3†

Kai-ning Lu3† Yue-ping Teng4

Yue-ping Teng4 Tian-han Zhou5

Tian-han Zhou5 Jia-yang Da6

Jia-yang Da6 Fan Wu1

Fan Wu1 Gang Pan1

Gang Pan1 Ding-cun Luo1,2*

Ding-cun Luo1,2*Thyroid cancer can be divided into two types according to its cellular origin, i.e., malignant tumors originating from thyroid cells and cancers that metastasize to the thyroid from other sites, the latter of which are, clinically rare. This article reports the diagnosis and treatment of a rectal neuroendocrine neoplasm metastasis to the thyroid. No similar cases have been reported before. This case suggests that when evaluating thyroid tumors, clinicians should not only carefully identify the clinical features of the tumor but also pay special attention to the patient’s history of tumors, especially neuroendocrine neoplasms. For definite secondary thyroid malignancies, neck surgery is feasible if the thyroid is the only site of metastasis; otherwise, the subsequent diagnosis and treatment plan should be determined after a comprehensive evaluation of the primary tumor and patient’s general condition.

Thyroid metastases (TMs) refer to a class of diseases that metastasize from nonthyroid malignancies to the thyroid. A retrospective study by Ghossein CA (1) found that the incidence of TM was 0.36% among all patients with thyroid malignancies who visited the center from 2003 to 2019. According to Tang Q (2), who reviewed the literature from 1979 to 2021, the most common origins of metastasis in these patients were renal cell carcinoma (48.1%), colorectal cancer (10.4%), lung cancer (8.3%), breast cancer (7.8%) and sarcoma (4.0%). The majority of colorectal cancer metastases to the thyroid originate from colorectal adenocarcinoma (3–5), and no cases of metastasis from rectal neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) to the thyroid gland have been reported. Herein, we report a case of rectal NEN metastasis to the thyroid and discuss the diagnosis and treatment of this patient. This study aims to improve clinicians’ ability to diagnose and treat TM and improve patient survival rate and quality of life.

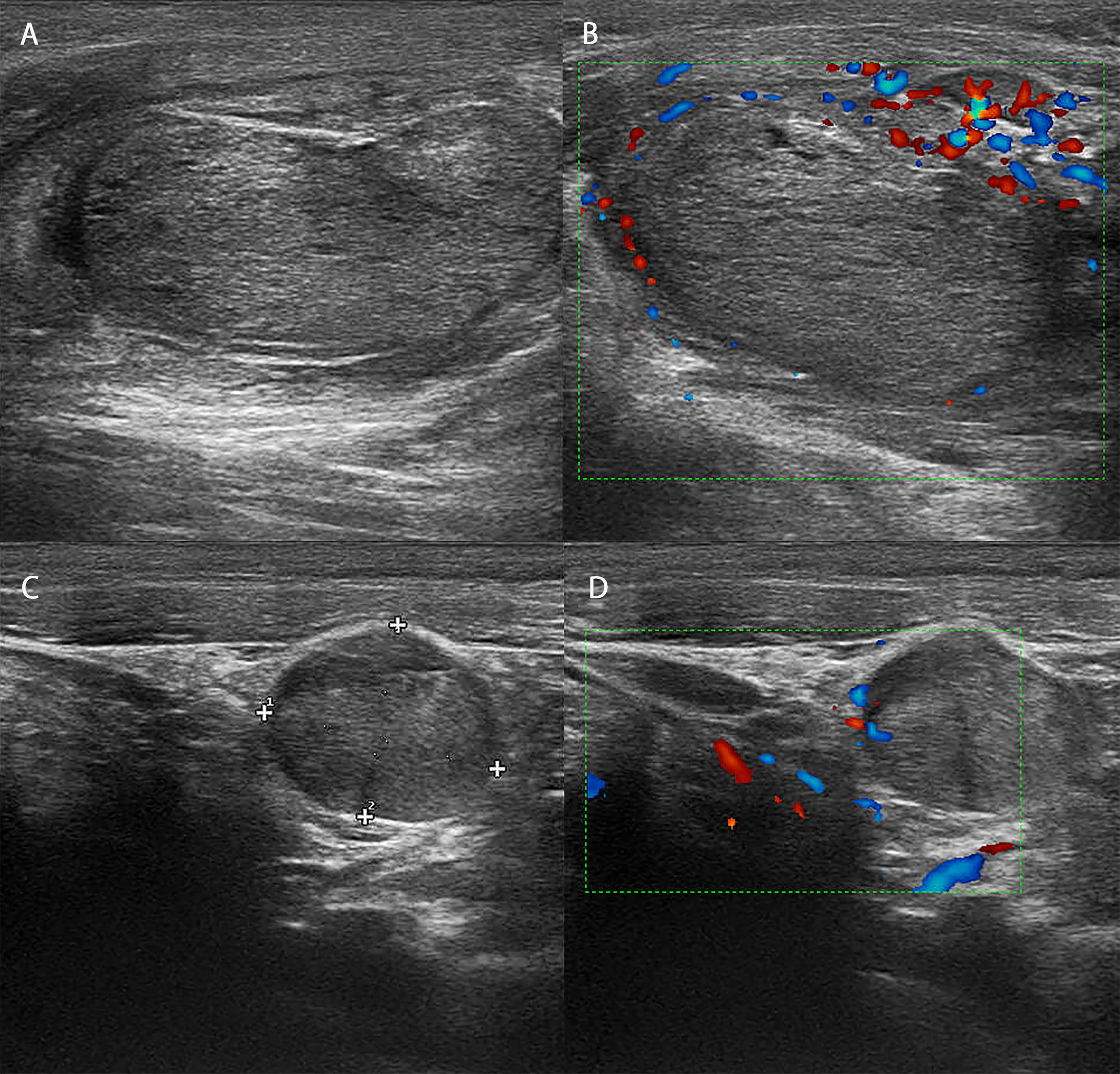

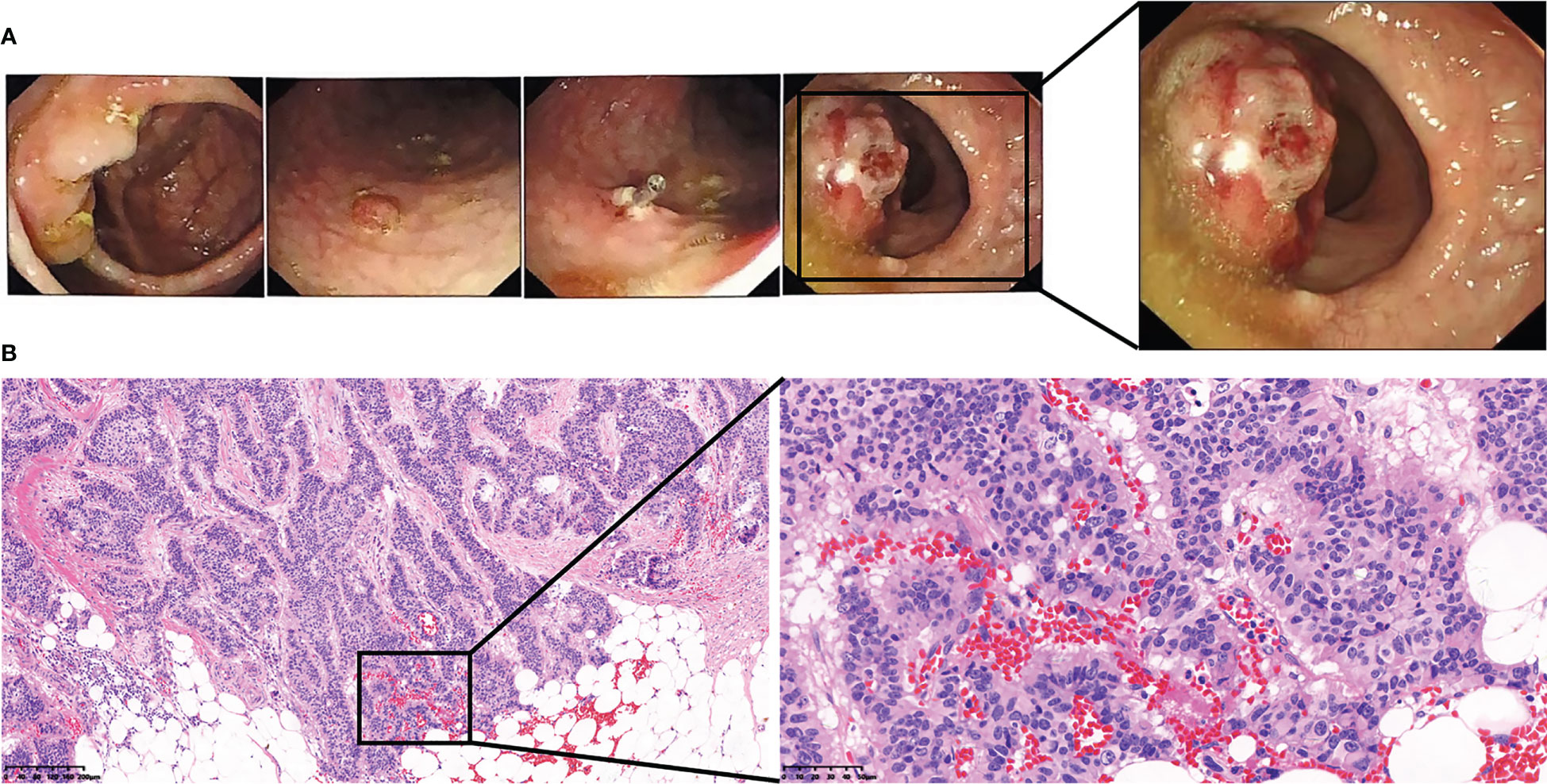

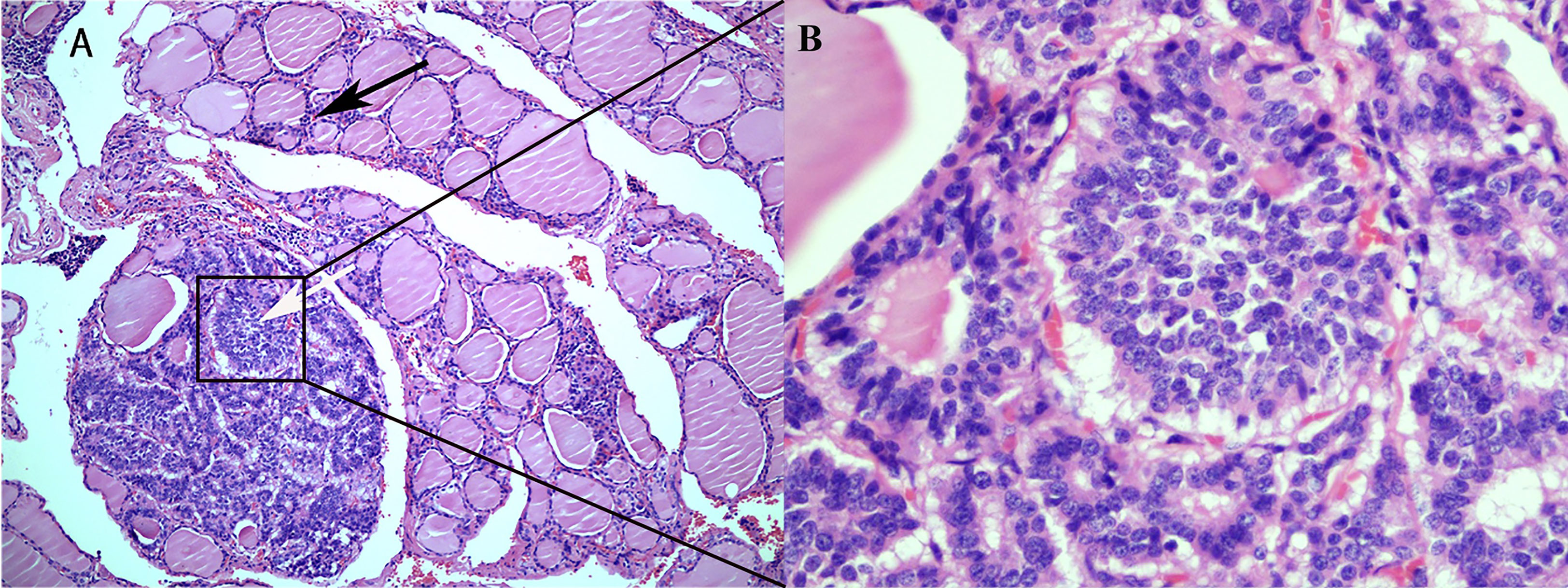

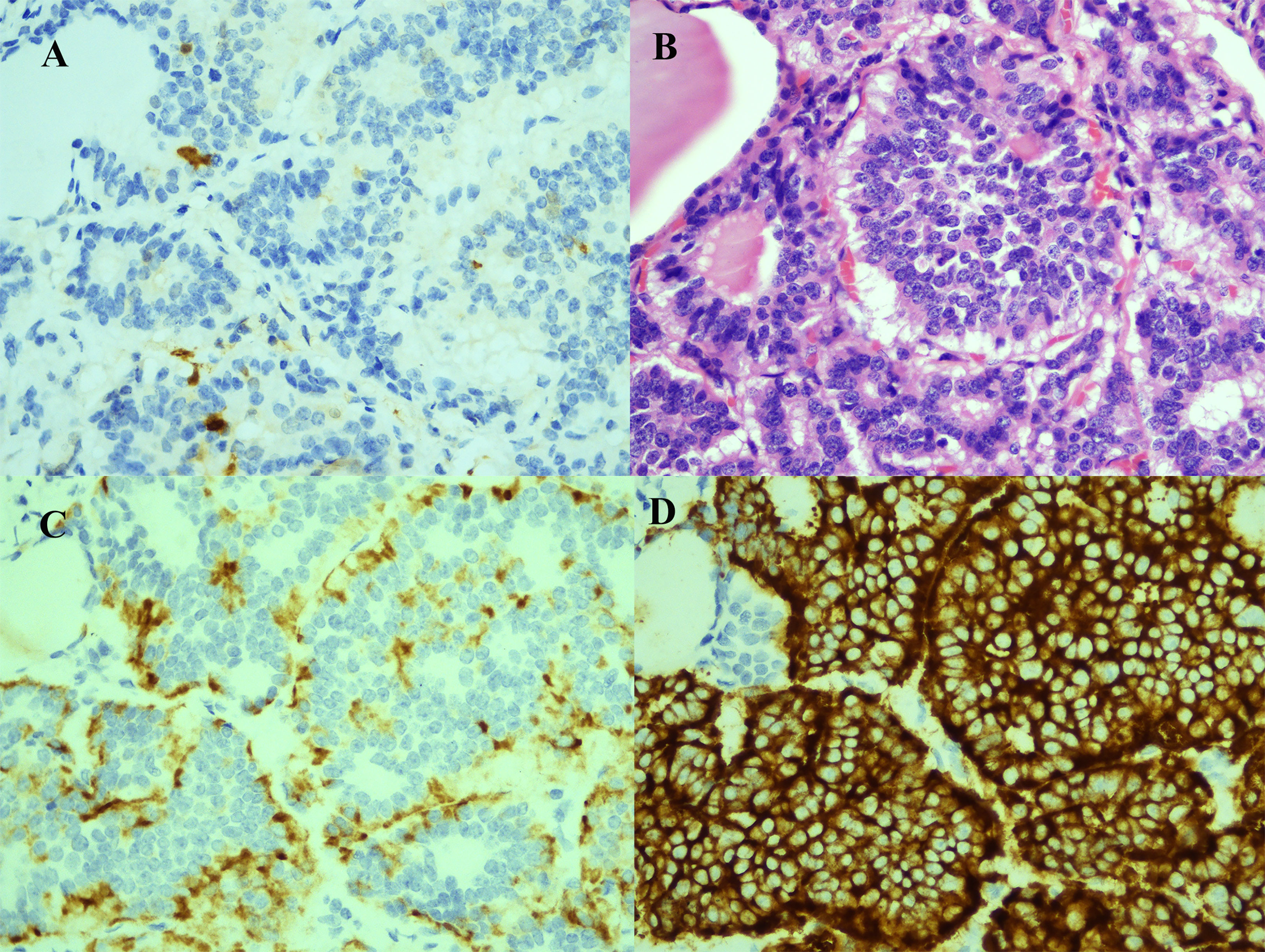

A 56-year-old woman presented with neck pain 1 month after the discovery of a thyroid nodule that developed 1 year prior. The patient was first found to have thyroid nodules by ultrasound in August 2017 (the details are unknown), and there were no symptoms of compression, hoarseness, palpitation, low-grade fever, or choking at that time. However, as the patient was only three months post-rectal cancer surgery and had a significant reaction to chemotherapy, she was extremely weak. The patient and their family chose to have regular follow-up examinations without further treatment for the thyroid nodules. Through regular follow-ups, the thyroid nodules grew larger and were accompanied by mild neck pain and enlarged surrounding lymph nodes. Therefore, the patient came to our hospital for further examination In September 2018, the patient came to the clinic after experiencing neck pain without other obvious discomfort. When palpating the thyroid gland in this patient, bilateral hard masses could be felt, measuring approximately 1.5*1.5 cm in size, with an unclear boundary, tenderness and rigidity, and the masses moved up and down with swallowing. Moreover, swollen and hard lymph nodes could be palpated on both sides of the neck, with a maximum size of approximately 2.0*1.0 cm. The rest of the physical examination showed no obvious abnormalities. Color Doppler ultrasound (Figure 1) and computed tomography (CT) showed multiple nodules with increased signals in the bilateral lobes of the patient’s thyroid; among them, the largest nodule on the right side was 2.0*2.0 cm and the largest nodule on the left side was 1.0*1.5 cm. The results of routine laboratory tests, including for those for thyroid function (T3, T4, TSH), liver and kidney function, and tumor markers (AFP, CEA, CA-199, CA-125, CA-153, CA-242), were normal. To further clarify the condition of the patient’s lesions, we performed a puncture biopsy. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) revealed the presence of suspicious tumor cells in the left thyroid nodule and infiltration or metastasis of malignant tumor cells in the left cervical lymph nodes. In May 2017, the patient underwent enteroscopy because bloody stools for 8 months and aggravated for the last 2 months. The result of enteroscopy suggested a rectal mass (Figure 2A) and the patient had previously undergone radical rectal resection for a rectal neuroendocrine neoplasm (NEN). The postoperative pathology showed a neuroendocrine tumor (Figure 2B), with a tumor size of 3.1cm*2.5cm, and the immunohistochemical results showed CK7[-], CK20[focal +], CKpan[+], Syn[+], CgA[-], CDX2[-], CD56[+], Ki67[5-10%], and EMA[partially+]. The postoperative pathology showed that the endocrine tumor of the rectum was a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor, WHO grade 2 (G2), stage IIIB. Chemotherapy with etoposide 120 mg + cisplatin 60 mg (EP regimen) was given for two cycles one month after surgery. The patient failed to continue chemotherapy due to personal reasons, and no abnormalities were found in subsequent reexaminations. Since the patient had no other distant metastatic lesions, we performed bilateral total thyroidectomy + bilateral central lymph node dissection on October 31, 2018. Postoperative pathology suggested bilateral metastatic thyroid NENs (Figure 3) and the immunohistochemical results showed CK[+], TG[-], TTF1 slightly scattered[+], HBME-1[-], S-100[-], Calcitonin[-], CgA[+], Syn[+], Ki-67[+] 10-20%, CK19 [+], CK20[-], PAX 8[-], CEA[-], CDX2[-] and SATB2[-] (Figure 4).

Figure 1 Ultrasound image and blood flow diagram of the patient’s lesion. (A) Ultrasound showed that there was an isoechoic nodule in the right lobe of the patient, with a size of approximately 2*2 cm, a regular shape, and an uneven halo around the edge. (B) Blood flow map showed poor blood flow in the patient’s right nodule. (C) Ultrasound showed that there was an isoechoic nodule in the right lobe of the patient, approximately 1.5*1 cm in size, with a regular shape and an uneven halo around the edge. (D) The blood flow map showed that the patient’s left nodule did not have rich blood flow.

Figure 2 The patient’s preoperative colonoscopy images and pathological images of rectal tumors. (A) The patient’s preoperative colonoscopy images. (B) The patient’s preoperative pathological images of rectal tumors.

Figure 3 Histological findings of a rectal neuroendocrine tumor metastasized to the thyroid. (A) Rectal neuroendocrine tumors are indicated by white arrows, and normal thyroid epithelial cells are indicated by black arrows (HE; 100X). (B) Metastatic neuroendocrine tumor without normal thyroid tissue (HE; 400X).

Figure 4 Immunohistochemical and cytological evidence of rectal neuroendocrine tumor metastasis to the thyroid. (A) Cancer cells negative for S-100 (S-100; 400X). (B) HE staining demonstrated typical neuroendocrine tumor morphology (HE; 400X). (C) Cancer cells positive for CgA (CgA; 400X). (D) Cancer cells positive for Syn (Syn; 400X).

The patient underwent regular follow-up after surgery. In January 2019, liver metastases were detected in another examination, followed by multiple metastases in bone and the pelvis. Oxaliplatin 130 mg D1+ S-1 60 mg d1-7 (SOX), anlotinib, irinotecan 260 mg d1 q2w and other drugs were used successively. Ultimately, the patient died of liver metastasis in May 2022, but there was no sign of recurrence in the neck.

Although the thyroid has an abundant blood supply, metastatic thyroid cancer is extremely rare (1, 6, 7). R.A. Willis (8) proposed two hypotheses to explain this phenomenon: 1. The faster blood flow in the thyroid prevents the adhesion of cancer cells. 2. The high oxygen saturation and high iodine content of the thyroid gland are not conducive to the growth of cancer cells. Metastatic cancer often occurs in thyroid tissue with existing lesions, such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, nodular goiter, and follicular adenoma. These basic lesions lead to changes in the thyroid microenvironment, which may create favorable conditions for the growth of metastatic cancer cells. However, there was no basic thyroid disease in this patient, so the cause of metastasis in this patient needs to be further explored. Moreover, the TMs in this patient were from a rectal neuroendocrine tumor, which is different from previous reports; thus, this case report has certain significance as a reference (9).

NENs are rare and highly heterogeneous tumors originating from neuroendocrine organs or cells. The most common site of occurrence is the gastrointestinal tract, and rectal NENs are more common in Asian people. The latest domestic research data in Japan show that rectal NENs account for 53% (10) of all gastrointestinal tract NENs, which is much higher than the rate of 28.6% in the United States (11). The data of 11,329 patients with NENs in the US SEER database between 1988 and 2012 showed a distant metastasis rate of 2% for tumors with a diameter ≤10 mm, 2.4% for those with a diameter 11-19 mm, and 12% for those with a diameter ≥20 mm. Therefore, clinicians, especially those in Asia, should pay attention to the existence of rectal NENs and the risk of distant metastasis.

TM has an insidious onset and often has no obvious clinical symptoms. Some patients may develop such tumors decades after the primary tumor is resected (12). Therefore, clinicians should remain alert to the possibility of metastatic thyroid cancer in patients with a history of malignancy and thyroid nodules. Color Doppler ultrasonography is the primary method recommended by domestic and foreign guidelines for the diagnosis of thyroid nodules, and this modality can also play an important role in the diagnosis of TMs. TMs have similar ultrasound characteristics similar to those of primary lesions, but their manifestations are diverse; they most commonly present as thyroid nodules or even areas with diffuse and uneven echogenicity. The main ultrasonographic manifestations of nodules are as follows: multiple lesions, large size, unclear boundary, irregular shape, solid, hypoechoic, calcification, and rich blood flow (13). In contrast to the above conclusions, the ultrasound images of this patient showed isoechoic nodules with clear boundaries, a regular shape, an uneven solid halo around the edge, and poor blood flow, which may be related to the different characteristics of the primary tumor. There was a high risk of misdiagnosis based on the B-mode ultrasound image of this patient, and such metastases should be carefully differentiated from the primary thyroid tumor and comprehensively judged based on the patient’s medical history. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is the first choice for patients with suspected metastatic thyroid cancer. FNAC is simple and easy to perform, and it is the best method for preoperative diagnosis (9). A multi-institution study report on FNAC showed that 87% of TM patients could be diagnosed with thyroid malignancy by FNAC, and 93% of them could be specifically diagnosed with TM (14). In this paper, preoperative FNAC indicated the possibility of malignancy, which provided an important basis for clinical decision-making. In conclusion, the diagnosis of TM should be based on ultrasound, FNAC and the patient’s past medical history.

Due to the very low incidence of TM, there are still no guidelines for its treatment. Most scholars believe that to achieve local neck control or even a cure, surgical treatment is the priority for patients whose thyroid is the only site of metastasis and whose primary cancer can be resected and cured (15–17). Considering that there was no evidence of distant metastasis, bilateral thyroid nodules were present, and the possibility of malignancy was confirmed by left puncture, bilateral total thyroidectomy and bilateral central lymph node dissection were performed for this patient at our hospital. Although the patient had multiple systemic metastases after surgery, there was no obvious recurrence in the neck, and a local cure was achieved, which was consistent with the above literature. It is worth noting that most TM patients have multiple systemic metastases at the same time (18–20), and a study by Stergianos S (21) noted out that 81% of patients will have metastases in parts of the body other than the thyroid. The author believes that when TM occurs, it likely indicates that the human body is under a high tumor burden, and that probability of multiple metastases throughout the body is high. Therefore, it is recommended that regular and timely general examinations be conducted after the discovery of TM and that the frequency of examinations should be increased. If the patient has multiple systemic metastases, treatment should be considered according to the primary lesion and the site of metastasis.

The prognosis of TM remains controversial. Most scholars believe that the prognosis of TM is generally poor. The median survival time reported in previous literature is 8.8-34.0 months (15, 21, 22), and the five-year overall survival rate is 11%-58% (1, 23, 24). Factors associated with prognosis include the type of primary tumor (20) and the occurrence time, number, size, and location of the metastatic tumors (25). For example, Stergianos S (21) reported that the survival rate of TM patients was higher when the primary tumor was renal cell carcinoma, versus other types of primary tumors. This may be related to renal cell carcinoma having a low degree of invasiveness and malignancy. A report by Beutner U (26) also posted that the median survival time of TM patients with renal cell carcinoma was 6.5 years after active surgical treatment, while the median survival time of TM patients with other primary tumors was only 4.7 years after surgical treatment. However, Papi G (27) believed that the overall survival time of cancer patients was not correlated with the presence or absence of TM. In summary, the prognosis of TM needs to be confirmed with more long-term follow-up data from large-scale, multicenter studies.

In conclusion, clinicians should remain alert to the possibility of TM in patients with thyroid nodules and a history of other malignancies to avoid missed diagnosis, misdiagnosis, and delayed treatment. Additionally, B-mode ultrasound and FNAC are important methods to assist clinicians in the diagnosis of TM. Furthermore, clinicians should consider the risk of multiple systemic metastases when patients present with TM, and surgical treatment is a good option for patients with only TM. However, for patients with multiple metastases, the choice of local surgery or comprehensive systemic treatment needs to be further verified by more follow-up data from large-sample, multicenter studies.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

YZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing. BL: Writing - Review & Editing. K-NL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Resources, Writing - Original Draft. Y-PT: Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision. T-HZ: Resources, Data Curation, Supervision. J-YD: Formal analysis, Resources, Data Curation. FW: Formal analysis, Resources. GP: Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Review & Editing. D-CL: Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The Project of Medical Scientific and Technology Program in Hangzhou (grant number A20200432). Zhejiang Province Basic Public Welfare Research Program Project (grant number GF22H165705). Zhejiang Province science and technology plan projects (grant number 2022KY939).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Ghossein CA, Khimraj A, Dogan S, Xu B. Metastasis to the thyroid gland: a single-institution 16-year experience[J]. Histopathology (2021) 78(4):508–19. doi: 10.1111/his.14246

2. Tang Q, Wang Z. Metastases to the thyroid gland: what can we Do?[J]. Cancers (Basel) (2022) 14(12):3017. doi: 10.3390/cancers14123017

3. Amante MA, Real IO, Bermudez G. Thyroid metastasis from rectal adenocarcinoma[J]. BMJ Case Rep (2018) 2018:bcr2018225549. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-225549

4. Rojo-Abecia M, Rivera-Alonso D, Herrero-Álvarez S, Ochagavía-Cámara S, Torres-García AJ. Thyroid metastases from colorectal cancer 14 years later: a case report and literature review[J]. Cir Cir (2020) 88(4):508–10. doi: 10.24875/ciru.19001130

5. Yeo SJ, Kim KJ, Kim BY, Jung CH, Lee SW, Kwak JJ, et al. Metastasis of colon cancer to medullary thyroid carcinoma: a case report[J]. J Korean Med Sci (2014) 29(10):1432–5. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.10.1432

6. Zivaljevic V, Jovanovic M, Perunicic V, Paunovic I. Surgical treatment of metastasis to the thyroid gland: a single center experience and literature review[J]. Hippokratia (2018) 22(3):137–40.

7. Zhang X, Gu X, Li JG, Hu XJ. Metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma to the thyroid gland with widespread nodal involvement: a case report[J]. World J Clin cases (2020) 8(19):4588–94. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4588

9. Nguyen M, He G, Lam AK. Clinicopathological and molecular features of secondary cancer (Metastasis) to the thyroid and advances in Management[J]. Int J Mol Sci (2022) 23(6):3242. doi: 10.3390/ijms23063242

10. Masui T, Ito T, Komoto I, Uemoto S. Recent epidemiology of patients with gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NEN) in Japan: a population-based study[J]. BMC Cancer (2020) 20(1):1104. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07581-y

11. Xu Z, Wang L, Dai S, Chen M, Li F, Sun J, et al. Epidemiologic trends of and factors associated with overall survival for patients with gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in the united States[J]. JAMA Netw Open (2021) 4(9):e2124750. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.24750

12. Mattavelli F, Collini P, Pizzi N, Gervasoni C, Pennacchioli E, Mazzaferro V. Thyroid as a target of metastases. a case of foregut neuroendocrine carcinoma with multiple abdominal metastases and a thyroid localization after 21 years[J]. Tumori (2008) 94(1):110–3. doi: 10.1177/030089160809400119

13. Battistella E, Pomba L, Mattara G, Franzato B, Toniato A. Metastases to the thyroid gland: review of incidence, clinical presentation, diagnostic problems and surgery, our experience[J]. J Endocrinol Invest (2020) 43(11):1555–60. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01282-w

14. Pusztaszeri M, Wang H, Cibas ES, Powers CN, Bongiovanni M, Ali S, et al. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of secondary neoplasms of the thyroid gland: a multi-institutional study of 62 cases[J]. Cancer Cytopathol (2015) 123(1):19–29. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21494

15. Manatakis DK, Tasis N, Antonopoulou MI, Kordelas A, Balalis D, Korkolis DP, et al. Colorectal cancer metastases to the thyroid gland-a systematic review: colorectal cancer thyroid metastases[J]. Hormones (Athens) (2021) 20(1):85–91. doi: 10.1007/s42000-020-00255-1

16. Straccia P, Mosseri C, Brunelli C, Rossi ED, Lombardi CP, Fadda G, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of metastases to the thyroid gland: a meta-Analysis[J]. Endocrine Pathol (2017) 28(2):112–20. doi: 10.1007/s12022-017-9475-6

17. Wang X, Huang Y, Zheng Z, Cao W, Chen B, Wang X. Metastases to the thyroid gland: a retrospective analysis of 21 patients[J]. J Cancer Res Ther (2018) 14(7):1515–8. doi: 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_435_16

18. Pensabene M, Stanzione B, Cerillo I, Ciancia G, Cozzolino I, Ruocco R, et al. It is no longer the time to disregard thyroid metastases from breast cancer: a case report and review of the literature[J]. BMC Cancer (2018) 18(1):146. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4054-x

19. Wu ZH, Dai JY, Shi JN, Fang MY, Cao J. Thyroid metastasis from chondrosarcoma[J]. Med (Baltimore) (2019) 98(47):e18043. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000018043

20. Chung AY, Tran TB, Brumund KT, Weisman RA, Bouvet M. Metastases to the thyroid: a review of the literature from the last decade[J]. Thyroid (2012) 22(3):258–68. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0154

21. Stergianos S, Juhlin CC, Zedenius J, Calissendorff J, Falhammar H. Metastasis to the thyroid gland: characterization and survival of an institutional series spanning 28 years[J]. Eur J Surg Oncol (2021) 47(6):1364–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2021.02.018

22. Romero Arenas MA, Ryu H, Lee S, Morris LF, Grubbs EG, Lee JE, et al. The role of thyroidectomy in metastatic disease to the thyroid gland[J]. Ann Surg Oncol (2014) 21(2):434–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3282-1

23. Kaliszewski K, Szkudlarek D, Kasperczak M, Nowak Ł. Clear cell renal carcinoma metastasis mimicking primary thyroid tumor[J]. Pol Arch Intern Med (2019) 129(3):211–4. doi: 10.20452/pamw.4425

24. Iesalnieks I, Winter H, Bareck E, Sotiropoulos GC, Goretzki PE, Klinkhammer-Schalke M, et al. Thyroid metastases of renal cell carcinoma: clinical course in 45 patients undergoing surgery. assessment of factors affecting patients’ survival[J]. Thyroid (2008) 18(6):615–24. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0343

25. Nixon IJ, Coca-Pelaz A, Kaleva AI, Triantafyllou A, Angelos P, Owen RP, et al. Metastasis to the thyroid gland: a critical Review[J]. Ann Surg Oncol (2017) 24(6):1533–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5683-4

26. Beutner U, Leowardi C, Bork U, Lüthi C, Tarantino I, Pahernik S, et al. Survival after renal cell carcinoma metastasis to the thyroid: single center experience and systematic review of the literature[J]. Thyroid (2015) 25(3):314–24. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0498

Keywords: neuroendocrine tumor, neoplasm metastasis, thyroid gland, rectal cancer, FNA

Citation: Zhang Y, Lin B, Lu K-n, Teng Y-p, Zhou T-h, Da J-y, Wu F, Pan G and Luo D-c (2023) Neuroendocrine neoplasm with metastasis to the thyroid: a case report and literature review. Front. Oncol. 13:1024908. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1024908

Received: 22 August 2022; Accepted: 12 April 2023;

Published: 28 April 2023.

Edited by:

Pinuccia Faviana, University of Pisa, ItalyReviewed by:

Zheyu Yang, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Zhang, Lin, Lu, Teng, Zhou, Da, Wu, Pan and Luo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ding-cun Luo, bGRjNjVAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.