95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol. , 08 December 2022

Sec. Gastrointestinal Cancers: Gastric and Esophageal Cancers

Volume 12 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.986762

This article is part of the Research Topic Methods in Gastrointestinal Cancers View all 51 articles

Background: Sintilimab plus chemotherapy (SIDCHM) is more effective than placebo plus chemotherapy (PLCHM) for advanced or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). However, considering the high cost of sintilimab, this study evaluated the cost-effectiveness of SIDCHM in comparison with PLCHM for advanced or metastatic ESCC from the Chinese healthcare system perspective.

Methods: Polymorphic Markov models were constructed to simulate the course and cost of SIDCHM. Treatment drug costs were calculated at national list prices and clinical data, other costs, and utility values were extracted from the reference literature. Primary outcomes included quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs). The robustness of the model was verified by one-way sensitivity analysis and probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA).

Results: SIDCHM obtained 1.03 QALYs at $24,044.49, whereas the effectiveness and cost of PLCHM were 0.67 QALYs and $14,166.24, respectively. The ICER for SIDCHM versus PLCHM was $23,458.08/QALY. The utility of the PFS state was the parameter that had the greatest effect on the ICER. The PSA showed that SIDCHM had an 86% probability of being cost-effective at the willingness-to-pay threshold of 3* Chinese gross domestic product per capita ($37,653/QALY).

Conclusion: From the Chinese healthcare system perspective, SIDCHM is considered a cost-effective treatment option compared with PLCHM as first-line therapy for advanced or metastatic ESCC.

Esophageal cancer (EC) is one of the most frequently occurring malignancies of the digestive tract, ranking seventh in the incidence of malignant tumors worldwide; it is also a very aggressive and lethal disease (1, 2). In the histological subtype, the most common EC is squamous cell carcinoma (2), and the rate of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is high in China, accounting for more than half of all patients with ESCC worldwide (3). Platinum drugs in combination with fluorouracil or paclitaxel are recommended as a standard first-line therapy currently for advanced or metastatic ESCC (4). In China, platinum plus paclitaxel is generally used, and platinum plus fluorouracil was chosen in preference in other countries (5). However, the median survival of patients with ESCC treated with standard first-line therapy is only 7.0–13.0 months, with very unsatisfactory results (6). The development of new therapy protocols for patients with advanced or metastatic ESCC, as a result, is an urgent matter.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) which enhances the antitumor activity of T cells by blocking the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) or cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) pathways, has shown breakthroughs in cancer therapy and has been effective in the treatment of EC in recent years (7, 8). The outcome of the phase II study by Xu et al. showed that the PD-1 inhibitor sintilimab significantly improved the overall survival of patients with advanced or metastatic ESCC after first-line chemotherapy compared to chemotherapy (9). A recent investigational phase III clinical study (ORIENT-15) evaluated the effect of sintilimab or placebo in combined chemotherapy (cisplatin plus paclitaxel or fluorouracil) as first-line therapy for unresectable locally advanced, recurrent, or metastatic ESCC. Sintilimab plus chemotherapy (SIDCHM) showed encouraging results with significant advantages in overall survival (OS, 16.7 vs 12.5 months, P < 0.001) and progression-free survival (PFS, 7.2 vs 5.7 months, P < 0.001) in comparison with placebo plus chemotherapy (PLCHM) (5).

Despite the significant advantages of sintilimab in the treatment of advanced or metastatic ESCC, we cannot ignore its high costs. Therefore, an economic evaluation of SIDCHM as a first-line treatment for advanced or metastatic ESCC based on the ORIENT-15 trial from the Chinese healthcare system perspective was designed.

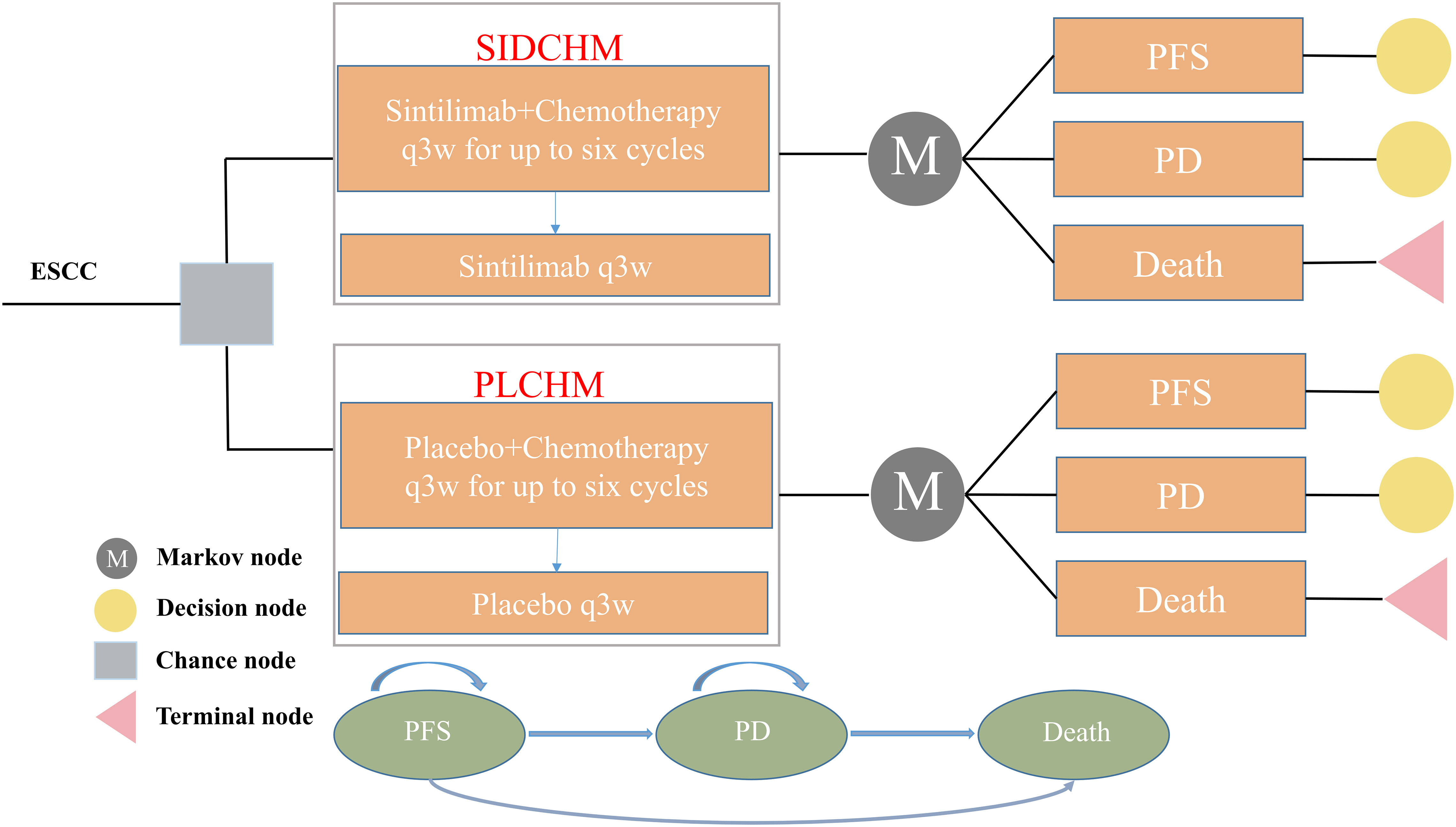

A Markov model was constructed to simulate the cost and effectiveness of SIDCHM, compared with PLCHM, as treatment in the first line for patients with advanced or metastatic ESCC in China. TreeAge Pro 2022 (TreeAge Software, LLC, USA) was used to develop the model and the R software (version 4.2.0) program was used for statistical analyses. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were numerically digitized to select the best-fit survival distribution. Finally, the Weibull survival distribution was used to generate the probability of metastasis for SIDCHM and PLCHM (Table 1). The model comprised three mutually exclusive health states: PFS, progressive disease (PD), and death (Figure 1) and has a run time of approximately 6 years (to be determined by the time at which 99% of the patients are assumed to die), and each cycle is 21 days long in this model. Through each cycle, patients either hold their assigned health status or advance to new health status and are not allowed to revert to their former health status. The background mortality rate in a Chinese context (10) was also calculated in the model. The output data we eventually had from the model was the total cost, quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). We set the willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold at $37,653 (three times China’s GDP in 2021 per capita), as recommended by the World Health Organization, and consider the treatment option cost-effective if the ICER is below our predefined WTP threshold.

Figure 1 The Markov model simulates outcomes for the ORIENT-15 trial. All patients with ESCC started with PFS state and received treatment with SIDCHM or PLCHM. ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression-free survival; PLCHM, placebo plus chemotherapy; SIDCHM, sintilimab plus chemotherapy.

Data on the clinical efficacy and adverse events were obtained from the ORIENT-15 trial (5). The trial screened patients of ESCC (Their inclusivity criteria were age≥18 years with histologically unresectable locally regionally advanced, recurrent, or metastatic ESCC; unsuitable for curative surgery or definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy; no prior history of systemic therapy, etc.) and then randomized eligible ones to either the SIDCHM group or the PLCHM group. Sintilimab or placebo was administered per cycle (21 days) until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity developed. Chemotherapy drugs (cisplatin plus paclitaxel or fluorouracil) were also given once every 21 days, that is, cisplatin at 75 mg/m2 per cycle, paclitaxel at 175 mg/m 2 per cycle, or fluorouracil at 800 mg/m2 per cycle. Chemotherapy was provided for up to six cycles; thereafter, treatment was continued with sintilimab or placebo until disease progression or unendurable toxicity. Sintilimab or placebo lasted for a maximum of 24 months. If chemotherapy is not resistible, sintilimab or placebo was provided. Chemotherapy (cisplatin plus paclitaxel or fluorouracil) was not convertible during the study. We assumed that patients of the SIDCHM group received 200 mg of sintilimab and that patients in both arms received the best supportive care (BSC) after disease progression occurs.

We have only calculated direct medical costs, including costs of drugs, tests (e.g., laboratory tests and radiological tests), follow-up, end-of-life care, management of adverse events of severe grade >3, and BSC. Drug costs were based on national tender prices, and other costs were based on published publications. Prices were adjusted to 2021 prices using the China Statistics Bureau Medical Price Index. All costs were expressed in dollars and converted at the average of the 2021 exchange rate (1 dollar = 6.45 RMB). The utility values for PD and PFS were taken from the published literature (11) as there were no relevant quality-of-life data from the ORIENT-15 trial. Costs and utilities were discounted, and the discounted value was 3% per year.

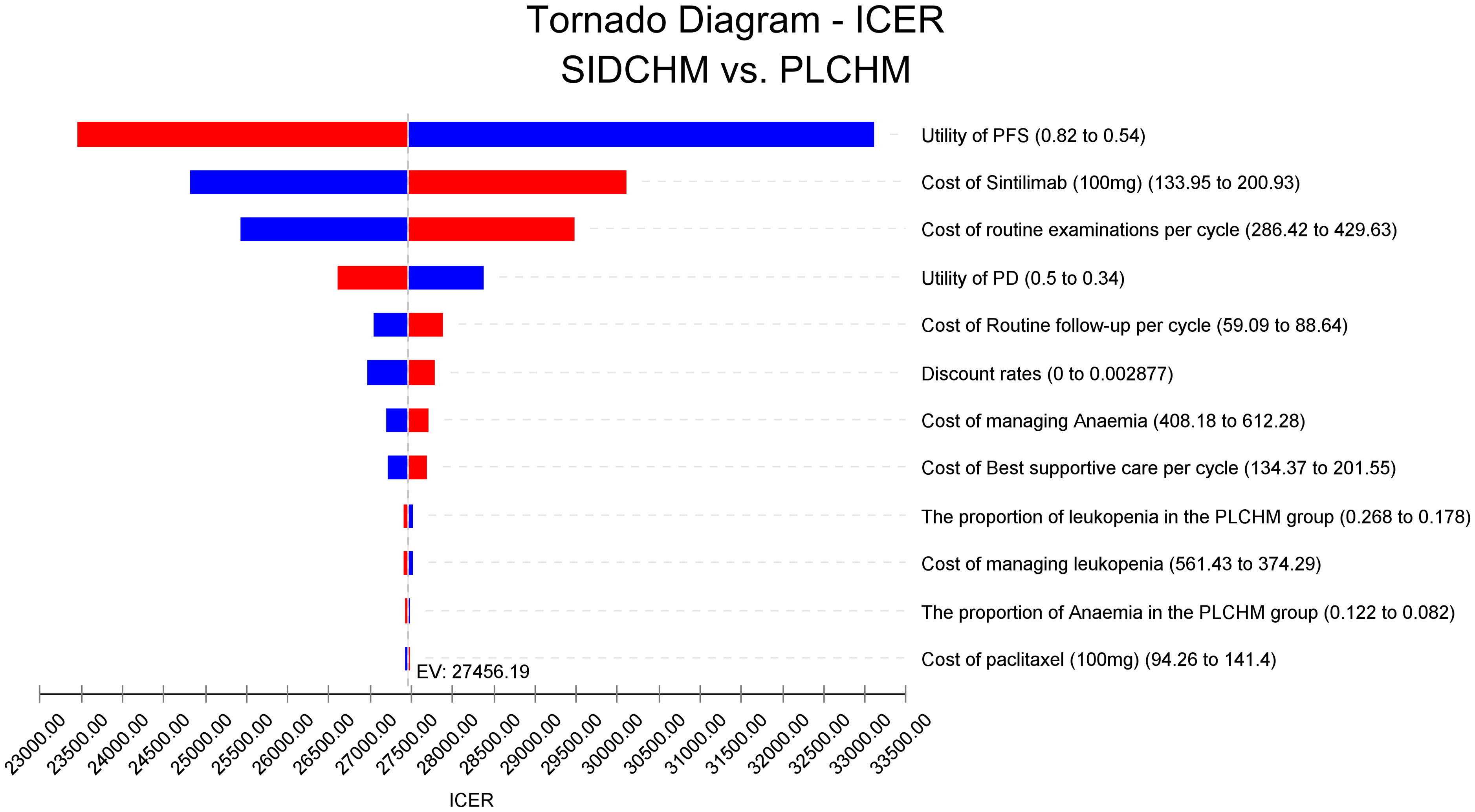

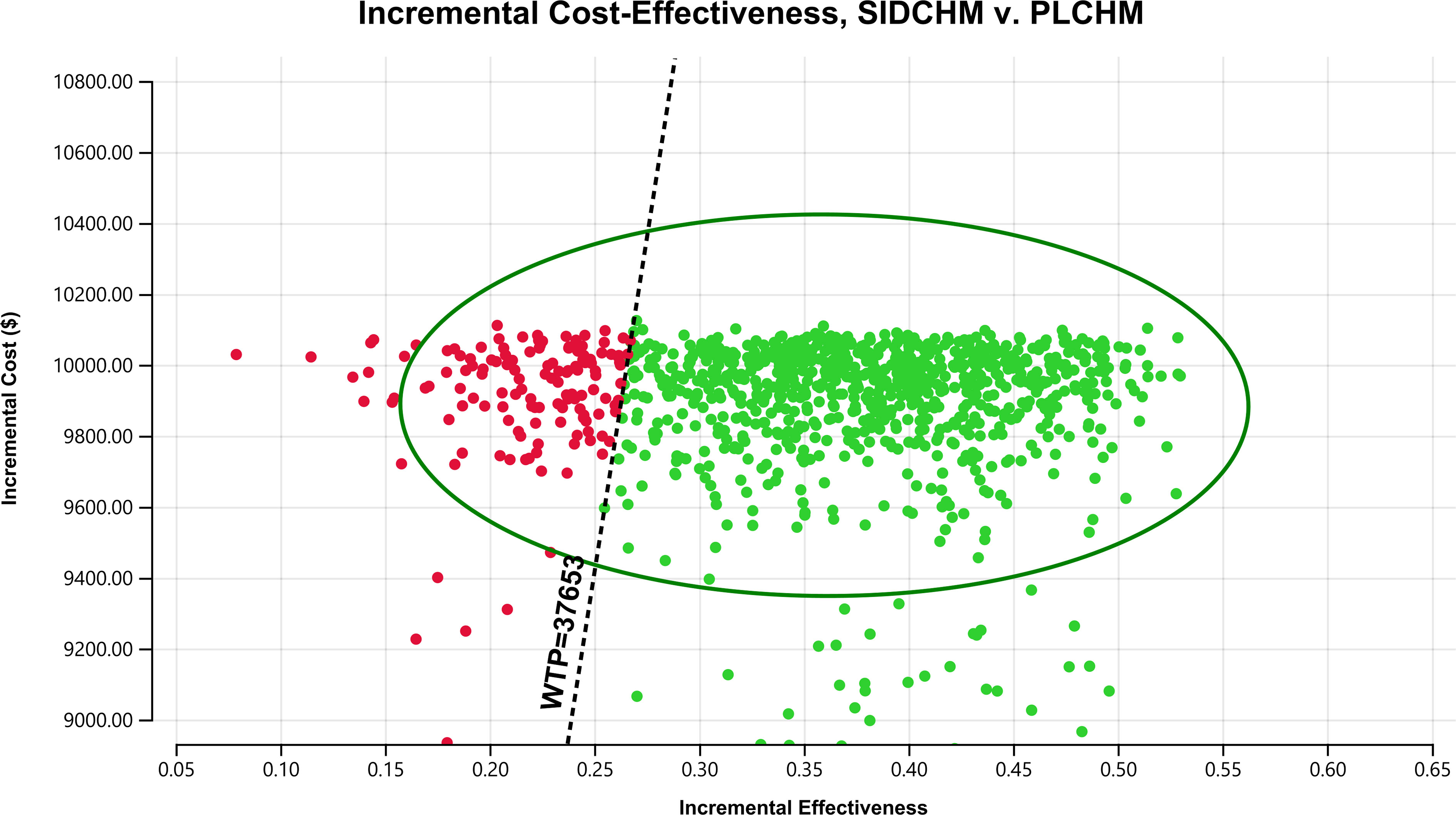

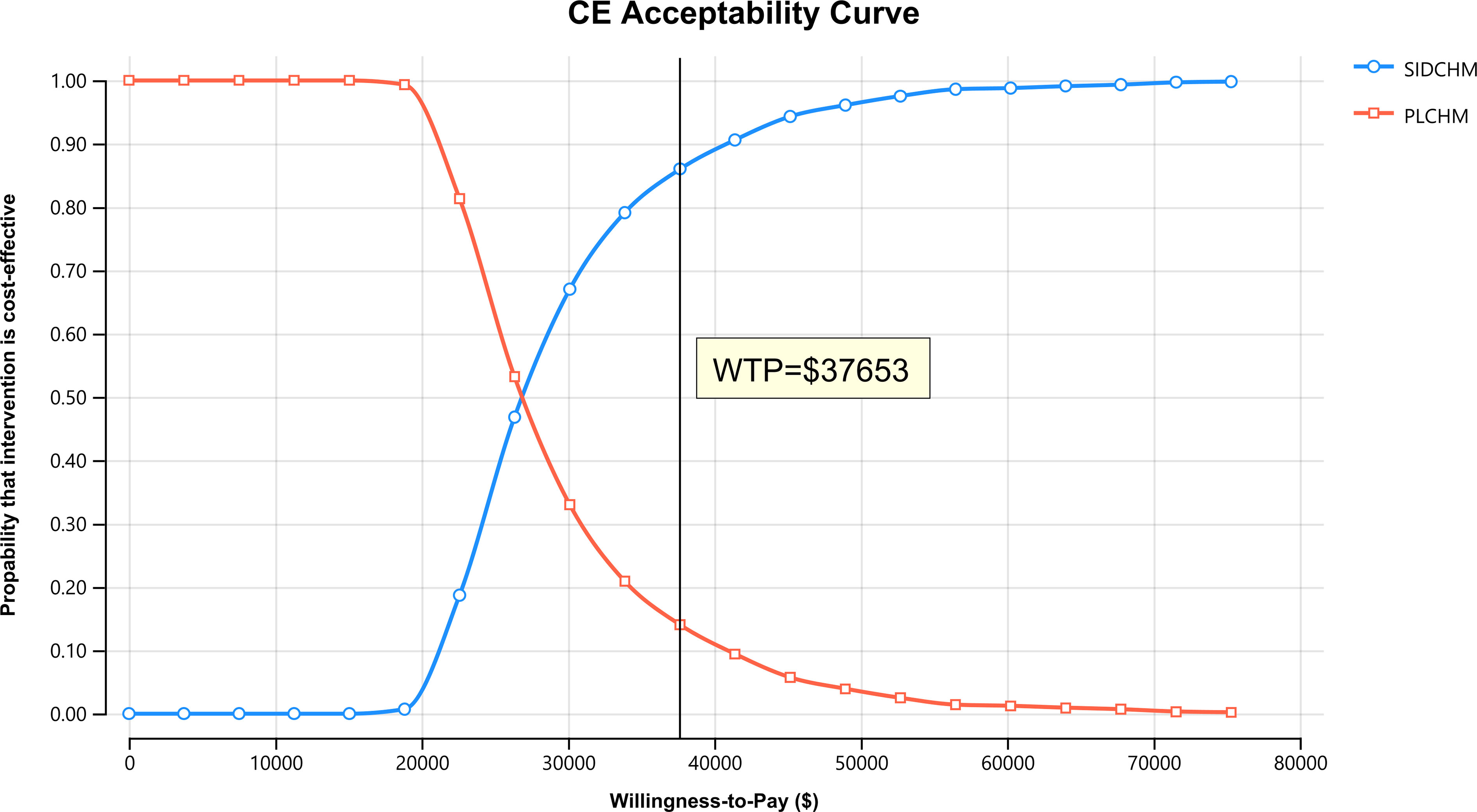

To examine the robustness of the model, this study provides a sensitivity analysis of our model, including one-way sensitivity analysis and probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA). We adjusted all of the variables up or down within a specified range to establish the most economically influential parameters for the one-way sensitivity analysis. The final results were represented as a Tornado diagram. The maximum and minimum values of these variables were extracted from the literature, and in the presence of missing data the base value of ±20% was used, and the discount rate was used as the lower and upper limits of 0 and 5%, respectively (Table 2). The PSA was used to verify the effect of the factors on the uncertainty of the results, and we performed 1000 replications of Monte Carlo simulations with all parameters assigned with the distribution appropriate in the model (Table 2). The results were expressed as a probabilistic scatter plot and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves.

We performed subgroup analyses of all patients by using subgroup-specific hazard ratios reported from the ORIENT-15 trial (5) based on the method of Hoyle et al. (18).

The base case showed that the SIDCHM group achieved 1.03 QALYs at $24,044.49. The effectiveness was 0.67 QALYs at $14,166.24 in the PLCHM group. The incremental effect and cost of SIDCHM compared with PLCHM were 0.36 QALYs and $9878.25, respectively. The ICER for SIDCHM compared with PLCHM was $23458.08/QALY (Table 3). In China, SIDCHM is a cost-effective treatment strategy compared to PLCHM when the cost-effectiveness WTP threshold is $37,653/QALY.

In the one-way sensitivity analysis, results were presented in a Tornado diagram (Figure 2). The utility value of PFS and the cost of sintilimab (100 mg) had the most important influences on the results of the model, and the parameters that had relatively minor effects on the model were the cost of laboratory tests and radiological examinations, the utility value of PD, cost of follow-up, etc. However, even if the values of these variables were changed, the ICER was always below our predefined WTP threshold. The results of the PSA are expressed as a probabilistic scatter plot (Figure 3) and cost-effectiveness acceptance curve (Figure 4), with an 86% probability that the SIDCHM group was cost-effective compared with the PLCHM group when the WTP threshold was $37,653.

Figure 2 One-way sensitivity analyses of SIDCHM in comparison with PLCHM in China. BSA, body surface area; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression-free survival; PLCHM, placebo plus chemotherapy; SIDCHM, sintilimab plus chemotherapy7.

Figure 3 A probabilistic scatter plot of the ICER between the SIDCHM group and the PLCHM group. Each point means the ICER for 1 simulation. Ellipses are used to indicate 95% confidence intervals. Points that lie below the ICER threshold represent cost-effective simulations. ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; PLCHM, placebo plus chemotherapy; SIDCHM, sintilimab plus chemotherapy; WTP, willingness-to-pay.

Figure 4 The cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for the SIDCHM treatment option compared to the PLCHM treatment option. PLCHM, placebo plus chemotherapy; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; SIDCHM, sintilimab plus chemotherapy; WTP, willingness-to-pay.

For most subgroups, the ICER of SIDCHM compared with PLCHM was less than the WTP threshold of $37653/QALY, ranging from $26751.55/QALY (probabilities of cost-effectiveness, 87.1%) in patients with age ≥50 years to $335806.56/QALY (probabilities of cost-effectiveness, 53.6%) in patients with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status =0 (Table 4). Only in the subgroup of patients with programmed cell death ligand 1 expression (CPS)<1, the ICER of SIDCHM compared with PLCHM was higher than the WTP threshold of $37653/QALY (Table 4).

In China, EC is the fourth most frequent cause of cancer death and the sixth most prevalent type of cancer, with 300,000 deaths and approximately 320,000 new cases in 2020 (19). ESCC histologically is more prevalent in China, accounting for 90% of all EC cases (20, 21). Palliative chemotherapy as first-line therapy for advanced or metastatic ESCC not only has a restricted survival advantage but also has a poor prognosis and a high number of adverse effects. ICI can significantly improve survival duration and quality of living in a variety of cancers through the inhibition of CTLA-4 or PD-1 pathways (22, 23). ICI plus chemotherapy has become the standard first-line therapeutic option for advanced or metastatic ESCC according to the 2022 guideline for EC treatment (24). Paclitaxel plus cisplatin in combination with camrelizumab is the first-line therapy choice for advanced or metastatic ESCC. The cisplatin plus fluorouracil chemotherapy regimen is combined with pembrolizumab as the first-line treatment for advanced or metastatic EC. Thus far, to the best of our knowledge, only two economic evaluations of camrelizumab or pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy as a first-line treatment option compared with chemotherapy alone for advanced or metastatic EC have been conducted, but neither is cost-effective (11, 25). From a Chinese healthcare system perspective, Zhang et al. concluded that the probability of camrelizumab in addition to chemotherapy being cost-effective as a first-line treatment option for advanced or metastatic ESCC was lower than about 1% when compared with conventional chemotherapy at a cost-effectiveness threshold of $31,498.70, and the factor that had the greatest impact on the ICER was the cost of 200 mg of camrelizumab (11). The results of the economics study by Zhu et al. revealed that the first-line regimen of pembrolizumab plus fluorouracil and cisplatin for EC may not be as cost-effective as fluorouracil and cisplatin from a Chinese economic perspective, and the sensitivity analysis found that the price effect of pembrolizumab was the greatest (25). The high price of ICI will be a major constraint in making it a cost-effective solution. Therefore, searching for an ICI that is less expensive and has good results in treating advanced or metastatic ESCC is essential. Sintilimab is an ICI Self-developed in China and has a significant price advantage over other ICIs imported abroad. More promisingly, in the ORIENT-15 study, Lu et al. used SIDCHM for the first time to treat advanced or metastatic ESCC and showed that compared to chemotherapy, SIDCHM provided significantly better survival outcomes to patients with advanced or metastatic ESCC, with relative increases in median survival and PFS of 33.6% and 26.3%, respectively, with no obvious differences found in the incidence of adverse events (5). Undeniably, sintilimab may be an important option for immunotherapy in advanced or metastatic ESCC. However, the price of sintilimab is still high compared with chemotherapy, which may significantly increase healthcare expenditures, and previous economic analyses regarding the first-line treatment of advanced or metastatic ESCC with ICI have not been cost-effective from the Chinese healthcare system perspective (11, 25). Therefore, a cost-benefit analysis of sintilimab for advanced or metastatic ESCC is imperative.

Based on the ORIENT-15 trial (5), our economic analysis showed that compared with that of PLCHM, the ICER of SIDCHM as first-line therapy for advanced or metastatic ESCC in China was $23,458.08/QALY, and the probability of SIDCHM being cost-effective was 86% when the WTP threshold was set at $37,653/QALY. A major innovation in our study is the discovery of cost-effective first-line ICI therapeutic options for advanced or metastatic ESCC. The results of the subgroup analysis showed that most subgroups of patients preferred treatment with ADCHM owing to >50% probability of cost-effectiveness as compared to PLCHM, except for subgroups with programmed cell death ligand 1 expression (CPS)<1. A few pharmacoeconomic evaluations were conducted on sintilimab, with only three studies retrieved in PubMed, but their economic results were all cost-effective, which is consistent with our findings. Two economic studies using clinical data from the ORIENT-32 trial (26) demonstrated that compared with sorafenib, sintilimab plus bevacizumab may provide a cost-effective treatment for Chinese patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (14, 27). Rui et al. reported that sintilimab plus chemotherapy as a first-line therapeutic option for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer of locally advanced or metastatic was more cost-effective in China in comparison with karilizumab plus chemotherapy (28). Therefore, to reduce the economic burden of medical treatment and provide more accessibility to Chinese patients, more attention should be paid to whether to use SIDCHM as a first-line therapeutic option for advanced or metastatic ESCC compared to other ICIs from the perspective of policymaking in China. In other words, the present results have a significant reference value for the Chinese healthcare system in developing first-line therapeutic options for advanced or metastatic ESCC. We believe very strongly that SIDCHM has also the potential to become a cost-effective therapeutic option for other cancers because of its price advantage and positive anti-tumor effect, which needs more economic research.

Inevitably, this study has some limitations. First, given the shortage of long-term survival data, we must consider using the Weibull survival model to make inferences about survival outside of the follow-up time, which may not provide an accurate reflection of real-world conditions. We will update our cost-effectiveness analysis when longer-term data on survival becomes available. Second, in the setting of disease progression, we chose to offer BSC to all patients due to the absence of relevant survival datasets for the enrolled patients, which may not accurately represent clinical practice at this time. We will analyze this further when relevant treatment costs and survival data for patients after progression are available. Third, in the model, we considered only the most common serious adverse events (SAEs) of level 3 and higher. The sensitivity analyses showed that the economic results were insensitive to SAE-associated. Fourth, although 7% of the patients in the ORIENT-15 trial received chemotherapy that was different from the preferred regimen in China, which may affect the economic evaluation in China, the results of the sensitivity analysis do not support the finding that this affected the economic results. Fifth, we had assumed that all patients chose 200 mg of sintilimab in the model, which is different from the real clinical situation. However, this would strengthen our economic results rather than change them because it raises the cost of the SIDCHM group. Sixth, changes in exchange rates affect direct medical costs, but the results of the one-factor sensitivity analysis indicate that healthcare costs do not change the results of the model when they change within the range we set. Finally, given the lack of relevant survival utility values for China, the utility values in this present study were obtained from other countries, which may result in model outcome bias. However, the results of the sensitivity analysis suggest that this does not affect the results of our economic evaluation. Despite these limitations, which cannot be ignored, this study is important as an economic reference for Chinese decision-makers to decide whether SIDCHM can be used as a first-line therapeutic option for advanced or metastatic ESCC.

Current relevant guidelines for advanced or metastatic ESCC do not recommend SIDCHM as a first-line treatment option. However, the results of this study suggest that from the Chinese healthcare system perspective, SIDCHM is a cost-effective therapy choice for advanced or metastatic ESCC compared with conventional chemotherapy. Our findings will provide an important economic basis for the Chinese healthcare system to decide whether to use SIDCHM as a first-line treatment option for advanced or metastatic ESCC.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Study design and supervision: MY, YHu, and ZC. Data analysis and interpretation: QW and WZ. Data collection: YHe and RC. Manuscript writing: MY. Final approval of the manuscript: All authors.

This study was supported in Social Development Project of Fuzhou Science and Technology Department (Grant number: 2021-S-108), Startup Fund for scientific research, Fujian Medical University (Grant number: 2019QH1301, 2021QH1203), and Mindong Hospital Science Fund (Grant number: 2022YN005). This study was not supported by any pharmaceutical company.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2022.986762/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure | (A) Survival curves for model and the ORIENT-15 trial in the SIDCHM group. (B) Survival curves for model and the ORIENT-15 trial in the PLCHM group. OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PLCHM, placebo plus chemotherapy.

1. Jiang Y, Zhang J, Zhao J, Li Z, Chen H, Qiao Y, et al. TOPK promotes metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by activating the Src/GSK3β/STAT3 signaling pathway via γ-catenin. BMC Cancer (2019) 19:1264. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6453-z

2. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

3. GBD 2017 Oesophageal Cancer Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of oesophageal cancer and its attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territorie-2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol (2020) 5:582–97. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30007-8

4. Kitagawa Y, Uno T, Oyama T, Kato K, Kato H, Kawakubo H, et al. Esophageal cancer practice guidelines 2017 edited by the Japan esophageal society: part 2. Esophagus (2019) 16:25–43. doi: 10.1007/s10388-018-0642-8

5. Lu Z, Wang J, Shu Y, Liu L, Kong L, Yang L, et al. Sintilimab versus placebo in combination with chemotherapy as first line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ORIENT-15): Multicentre, randomised, double blind, phase 3 trial. BMJ (Clinical Res ed.) (2022) 377:e068714. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068714

6. Luo H, Lu J, Bai Y, Mao T, Wang J, Fan Q, et al. Effect of camrelizumab vs placebo added to chemotherapy on survival and progression-free survival in patients with advanced or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: The ESCORT-1st randomized clinical trial. JAMA (2021) 326:916–25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.12836

7. Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, Esteban E, Felip E, De Angelis F, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-Small-Cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med (2018) 378:2078–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005

8. Huang J, Xu J, Chen Y, Zhuang W, Zhang Y, Chen Z, et al. Camrelizumab versus investigator's choice of chemotherapy as second-line therapy for advanced or metastatic oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCORT): A multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol (2020) 21:832–42. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30110-8

9. Xu J, Li Y, Fan Q, Shu Y, Yang L, Cui T, et al. Clinical and biomarker analyses of sintilimab versus chemotherapy as second-line therapy for advanced or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: A randomized, open-label phase 2 study (ORIENT-2). Nat Commun (2022) 13:857. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28408-3

10. Compiled by National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2021). Available at: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2021/indexch.htm (Accessed July 2, 2022).

11. Zhang Q, Wu P, He X, Ding Y, Shu Y. Cost-effectiveness analysis of camrelizumab vs. placebo added to chemotherapy as first-line therapy for advanced or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in China. Front Oncol (2021) 11:790373. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.790373

12. Li M, Lin S, Wilson L, Huang P, Wang H, Lai S, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of hepatic arterial infusion of FOLFOX combined sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein invasion. Front Oncol (2021) 11:562135. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.562135

13. Li S, Peng L, Tan C, Zeng X, Wan X, Luo X, et al. Cost-effectiveness of ramucirumab plus paclitaxel as a second-line therapy for advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal cancer in China. PloS One (2020) 15:e0232240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232240

14. Peng Y, Zeng X, Peng L, Liu Q, Yi L, Luo X, et al. Sintilimab plus bevacizumab biosimilar versus sorafenib as first-line treatment for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Front Pharmacol (2022) 13:778505. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.778505

15. Zhang PF, Xie D, Li Q. Cost-effectiveness analysis of nivolumab in the second-line treatment for advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Future Oncol (London England) (2020) 16:1189–98. doi: 10.2217/fon-2019-0821

16. Wu B, Li T, Cai J, Xu Y, Zhao G. Cost-effectiveness analysis of adjuvant chemotherapies in patients presenting with gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy. BMC Cancer (2014) 14:984. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-984

17. Insinga RP, Vanness DJ, Feliciano JL, Vandormael K, Traore S, Burke T. Cost-effectiveness of pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy in the 1st line treatment of non-squamous NSCLC in the US. J Med Econ (2018) 21:1191–205. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2018.1521416

18. Hoyle M, Green C, Thompson-Coon J, Liu Z, Welch K, Moxham T, et al. Cost-effectiveness of temsirolimus for first line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Value Health (2010) 13(1):61–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00617.x

19. Cao W, Chen HD, Yu YW, Li N, Chen WQ. Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: A secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chin Med J (2021) 134:783–91. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001474

20. Lin Y, Totsuka Y, He Y, Kikuchi S, Qiao Y, Ueda J, et al. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer in Japan and China. J Epidemiol (2013) 23:233–42. doi: 10.2188/jea.je20120162

21. He Y, Li D, Shan B, Liang D, Shi J, Chen W, et al. Incidence and mortality of esophagus cancer in chin-2012. Chin J Cancer Res (2019) 31:426–34. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2019.03.04

22. Galluzzi L, Humeau J, Buqué A, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunostimulation with chemotherapy in the era of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2020) 17:725–41. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-0413-z

23. Bagchi S, Yuan R, Engleman EG. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: Clinical impact and mechanisms of response and resistance. Annu Rev Pathol (2021) 16:223–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-042020-042741

24. Notice of the general office of the national health and health commission on printing distributing the guidelines for the treatment of oncology and hematology-related diseases, (2022 edition) (2022). Available at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s2911/202204/a0e67177df1f439898683e1333957c74.shtml (Accessed July 2, 2022).

25. Zhu Y, Liu K, Ding D, Zhou Y, Peng L. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced esophageal cancer: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Adv Ther (2022) 39:2614–29. doi: 10.1007/s12325-022-02101-9

26. Ren Z, Xu J, Bai Y, Xu A, Cang S, Du C, et al. Sintilimab plus a bevacizumab biosimilar (IBI305) versus sorafenib in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (ORIENT-32): A randomised, open-label, phase 2-3 study. Lancet Oncol (2021) 22:977–90. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00252-7

27. Zhou T, Cao Y, Wang X, Yang L, Wang Z, Ma A, et al. Economic evaluation of sintilimab plus bevacizumab versus sorafenib as a first-line treatment for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv Ther (2022) 39:2165–77. doi: 10.1007/s12325-022-02079-4

28. Rui M, Fei Z, Wang Y, Zhang X, Ma A, Sun H, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of sintilimab + chemotherapy versus camrelizumab + chemotherapy for the treatment of first-line locally advanced or metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC in China. J Med Econ (2022) 25:618–29. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2022.2071066

Keywords: cost-effectiveness, sintilimab plus chemotherapy, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, first-line treatment, placebo plus chemotherapy

Citation: You M, Huang Y, Cai Z, Wu Q, Zhu W, He Y and Chen R (2022) Cost-effectiveness analysis of sintilimab plus chemotherapy for advanced or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 12:986762. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.986762

Received: 05 July 2022; Accepted: 15 November 2022;

Published: 08 December 2022.

Edited by:

Zhendong Jin, Second Military Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Antonino Maniaci, University of Catania, ItalyCopyright © 2022 You, Huang, Cai, Wu, Zhu, He and Chen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ying He, aGV5aW5nMjQ3OEAxNjMuY29t; Ruijia Chen, cnVpamlhY2hlbjUwM0AxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.