94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Oncol. , 05 August 2022

Sec. Gastrointestinal Cancers: Gastric and Esophageal Cancers

Volume 12 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.927119

This article is part of the Research Topic Reviews in Gastrointestinal Cancers View all 35 articles

Objectives: To evaluate the clinical curative effects and toxicity of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for resectable gastric cancer compared to those of neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Methods: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy were performed in patients with resectable gastric cancer.

Results: Seven RCTs were included (601 patients; 302 in the neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy group and 299 in the neoadjuvant chemotherapy group). The neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy group had an increased number of patients with a complete response [odds ratio (OR) = 3.79, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.68–8.54, p = 0.001] and improved objective response rate (OR = 2.78, 95% CI: 1.69–4.57, p < 0.0001), 1-year (OR = 3.51, 95% CI: 1.40–8.81, p = 0.007) and 3-year (OR = 2.14, 95% CI: 1.30–3.50, p = 0.003) survival rates, R0 resection rate (OR = 2.21, 95% CI: 1.39–3.50, p = 0.0008), and complete pathologic response (OR = 4.39, 95% CI: 1.59–12.14, p = 0.004). Regarding the incidence of adverse effects after neoadjuvant therapy, only the occurrence rate of gastrointestinal reaction in the neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy group was higher than that in the neoadjuvant chemotherapy group (OR = 1.76, 95% CI: 1.09–2.85, p = 0.02), and there was no significant difference in other adverse effects. There was no difference in the incidence of postoperative complications between the two groups.

Conclusion: Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for resectable gastric cancer has several advantages in terms of efficacy and safety compared to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Therefore, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy has great potential as an effective therapy for resectable gastric cancers.

Systematic Review Registration: https://inplasy.com/inplasy-2022-3-0164, registration number INPLASY202230164.

Gastric cancer is a malignant tumor with high morbidity and mortality (1). Epidemiological statistics indicate that there were more than one million new cases of gastric cancer and 760,000 deaths in 2020, which rank fifth and fourth, respectively, in the incidence and mortality of cancer worldwide; for patients with advanced gastric cancer, the median survival rate is less than 12 months (2). The incidence is twice as high in men as in women, and the number of new cases continues to increase in younger patients (3). Gastric cancer remains a global health problem.

Surgery is known to play a crucial role in the treatment strategy of gastric cancer, and the prognosis and survival of patients are improved when surgery achieves R0 resection. Preoperative neoadjuvant therapy is the key to achieve R0 resection and has been proven to be effective for potentially resectable gastric cancer (4, 5). Theoretically, an effective preoperative approach can downgrade the tumor stage, facilitate R0 resection, and reduce local relapses and is imperative for patients with potentially resectable gastric cancer (6).

However, it is not clear whether neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) is superior to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (NACRT) in terms of efficacy and safety in potentially resectable gastric carcinoma (7). In 2004, J. A. et al. conducted a multi-institutional trial of NACRT in patients with potentially resectable gastric carcinoma that showed that NACRT caused a substantial pathologic response that resulted in durable survival (8, 9). NACRT followed by surgery and postoperative adjuvant therapy has been clinically recommended for esophageal and gastric junction cancer (10). However, the treatment strategy for non-esophagogastric junction cancer has been controversial, and the application of NACRT for gastric cancer has thus far only been tested in a small number of phase II studies (9). Therefore, in this study, we compared the efficacy and safety of NACRT with those of NACT in resectable gastric cancer through a meta-analysis to provide an evidence-based approach for the treatment of resectable gastric cancer.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses were followed as closely as possible for this systematic review and meta-analysis, and the protocol for this systematic review was registered on the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (202230164) and is available in full on inplasy.com (https://doi.org/10.37766/inplasy2022.3.0164).

The inclusion criteria of the study were as follows:

i. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published worldwide

ii. Patients confirmed by histopathological or cytological examination and assessed by gastroscopy, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to meet the diagnostic criteria for operable gastric cancer

iii. Patients in the experimental group received NACRT, whereas those in the control group received NACT

iv. The objective response rate (ORR), pathologic complete response (pCR), and R0 resection rate were used as primary efficacy outcomes. We evaluated the efficacy of neoadjuvant therapy in the two groups according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours. Complete response (CR): the disappearance of all target lesions. Partial response (PR): at least a 30% decrease in the sum of diameters of target lesions. Progressive disease (PD): at least a 20% increase in the sum of diameters of target lesions, taking as reference the smallest sum on the study. Stable disease (SD): neither sufficient shrinkage to qualify for PR nor sufficient increase to qualify for PD. ORR: the proportion of patients whose tumors shrank to a certain extent and remained there for a certain time, including CR + PR cases. The secondary indicators were survival rate and incidence of adverse reactions, including nausea and vomiting, myelosuppression, anemia, and digestive tract reactions.

The exclusion criteria of the study were as follows:

(i) Review articles, systematic evaluations, animal based experiments, or case reports

(ii) Non-RCTs, observational studies, or retrospective studies

(iii) Repeated articles, studies reporting incomplete or inconsistent outcomes, or having unreasonable trial designs

(iv) Some ongoing clinical trials with no published results

(v) Violation of any of the above inclusion criteria

Two investigators (JC and YG) independently searched PubMed, EMbase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, Chinese Biological Medicine Database, Wanfang Database, and VIP Database; we simultaneously searched for related trials in the International Clinical Trial Registry Platform and the Chinese Clinical Registry up to 1 October 2021. We used the following medical subject headings to search for the terms: stomach neoplasms, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Two investigators filtered the searched articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and when they had differences, a third researcher determined whether the article would be included.

Two investigators (JC and YG) independently reviewed the entire articles for all the eligible studies and extracted relevant data, including the author, year of publication, number of patients, age of patients, interventions, radiotherapy dose, and chemotherapy regimen. Two reviewers (MF and YY) evaluated the quality of the selected articles using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for RCTs and assessed the items in three categories according to the risk of bias (low, unclear, and high risk of bias), including random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), the blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting (reporting bias), and other biases.

All meta-analyses were performed using Cochrane RevMan version 5.3 and Stata (version 13). The results were reported as pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). We used Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistics to evaluate the heterogeneity of all the studies. If the heterogeneity was significant (p < 0.1, I2 > 50.0%), the random effects model was adopted; otherwise, the fixed effects model was used. Potential publication bias was assessed using funnel plots, Egger’s test, and Begg’s test. All p-values were two sided, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

We identified 256 articles for review of the title and abstract (Figure 1) and retrieved the full text of potentially eligible articles for a particular assessment after the initial screening. Seven studies were included in the meta-analysis. A total of 601 patients were enrolled, including 302 in the experimental group and 299 in the control group. The particular characteristics of each enrolled article are summarized thoroughly in Tables 1–3.

We evaluated the quality of all meta-analyses using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing the risk of bias, as shown in Figures 2, 3. Through our assessment, we concluded that all the included articles were randomized controlled trials, of which one article followed allocation concealment and other articles included trials carried out using the method of informed consent. There were no errors in that all the eligible studies adopted random numbers to decide the final treatment and all had completed data, no selective reports, or other deviations.

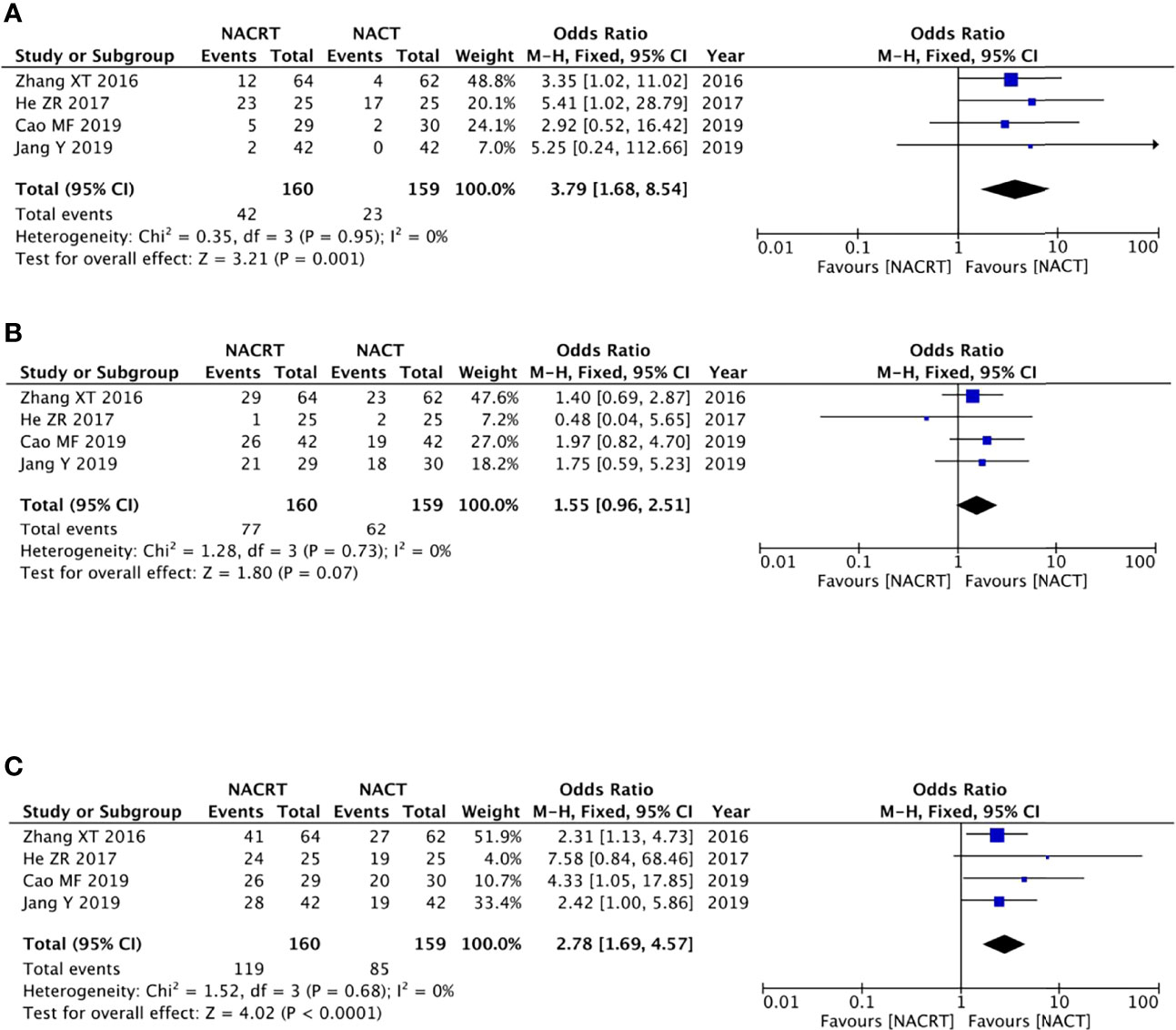

Four of the included articles reported the CR. Because there was no heterogeneity between the studies (p = 0.95, I2 = 0%), we adopted the fixed effects model for meta-analysis, which showed that the CR rate in the NACRT group was higher than that in the NACT group (OR = 3.79, 95% CI: 1.68–8.54, p = 0.001) and that the results were statistically significant (Figure 4A).

Figure 4 Forest plot for the complete response (CR) (A), partial response (PR) (B), and objective response rate (ORR) (C) of the neoadjuvantchemoradiotherapy (NACRT) group and neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) group.

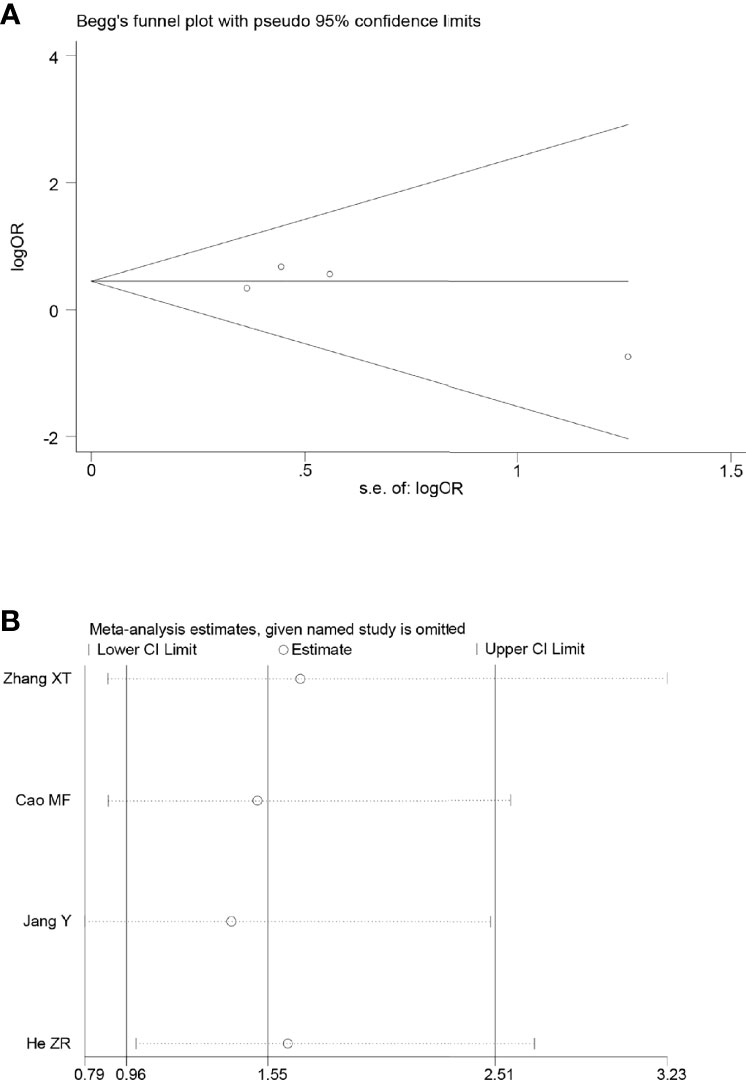

Four of the included articles reported the PR. Because there was no heterogeneity between the studies (p = 0.73, I2 = 0%), we adopted the fixed effects model for meta-analysis, which showed that the results were not statistically significant (OR = 1.55, 95% CI: 0.96–2.51, p = 0.07) (Figure 4B).

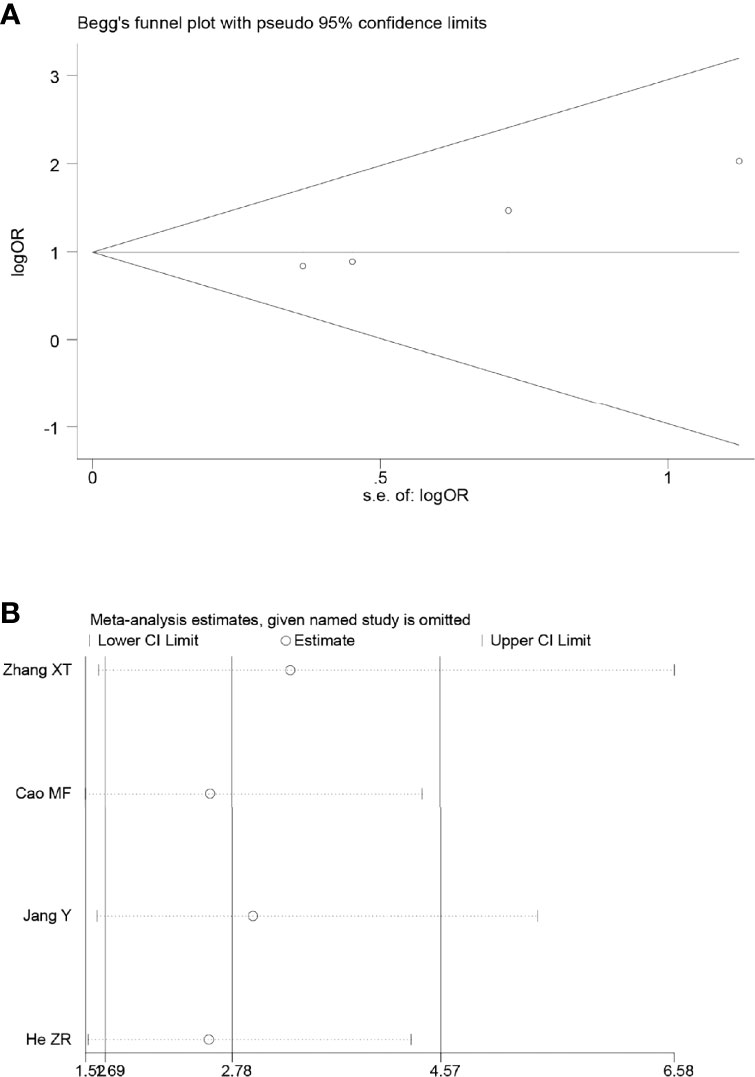

There were four studies that reported the ORR. There was no heterogeneity between the studies (p = 0.68, I2 = 0%); we therefore adopted the fixed effects model for meta-analysis, which showed that the ORR rate in the NACRT group was higher than that in the NACT group (OR = 2.78, 95% CI: 1.69–4.57, p < 0.0001) and that the results were statistically significant (Figure 4C).

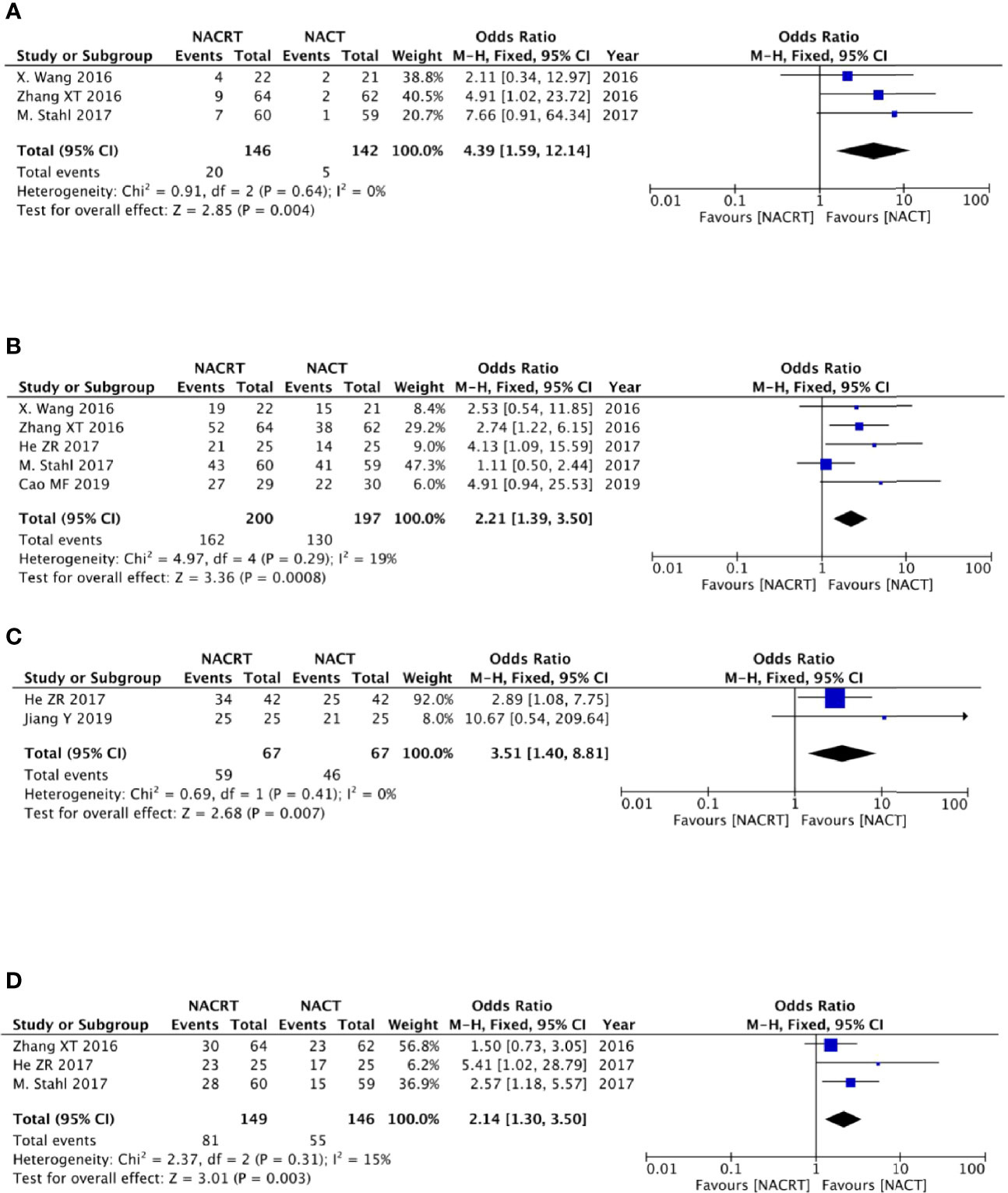

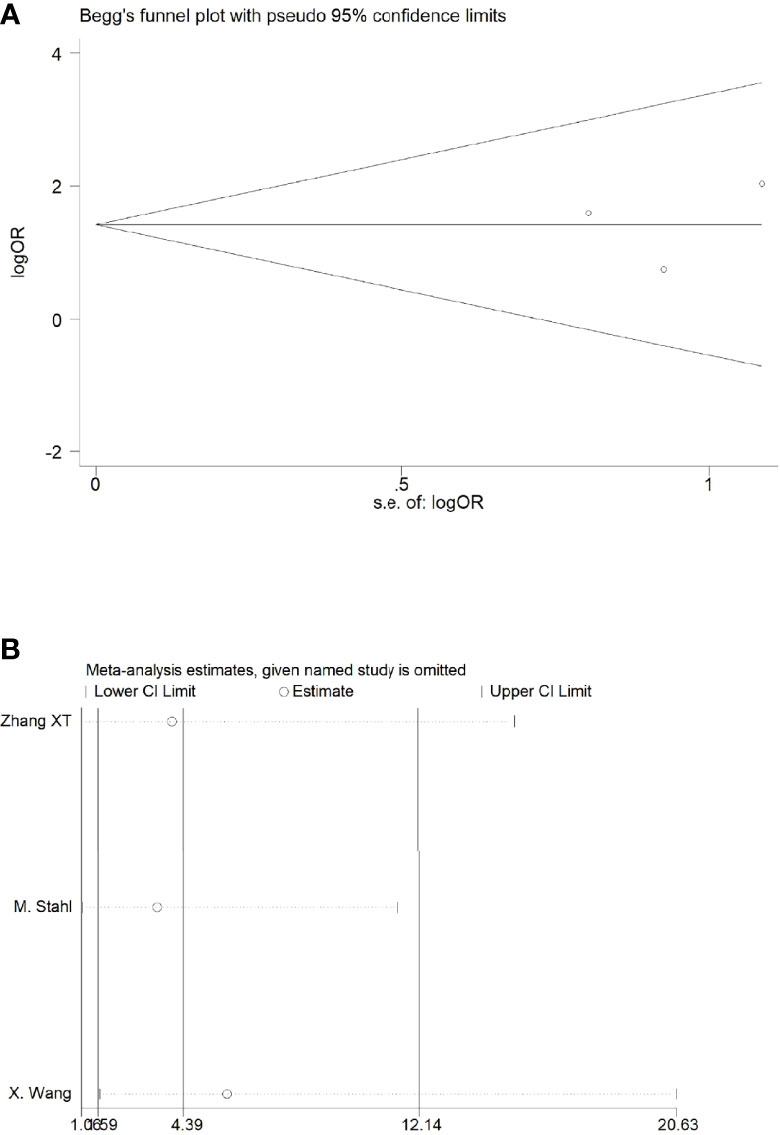

There were three studies among the included articles that reported the pCR. We adopted the fixed effects model for meta-analysis because there was no heterogeneity between the studies (p = 0.64, I2 = 0%), which showed that the pCR rate in the NACRT group was higher than that in the CRT group (OR = 4.39, 95% CI: 1.59–12.14, p = 0.004) and that the results were statistically significant (Figure 5A).

Figure 5 Forest plot for the pathologic complete response (pCR) rate (A), R0 resection rate (B), and 1- and 3-year survival rates (C, D).

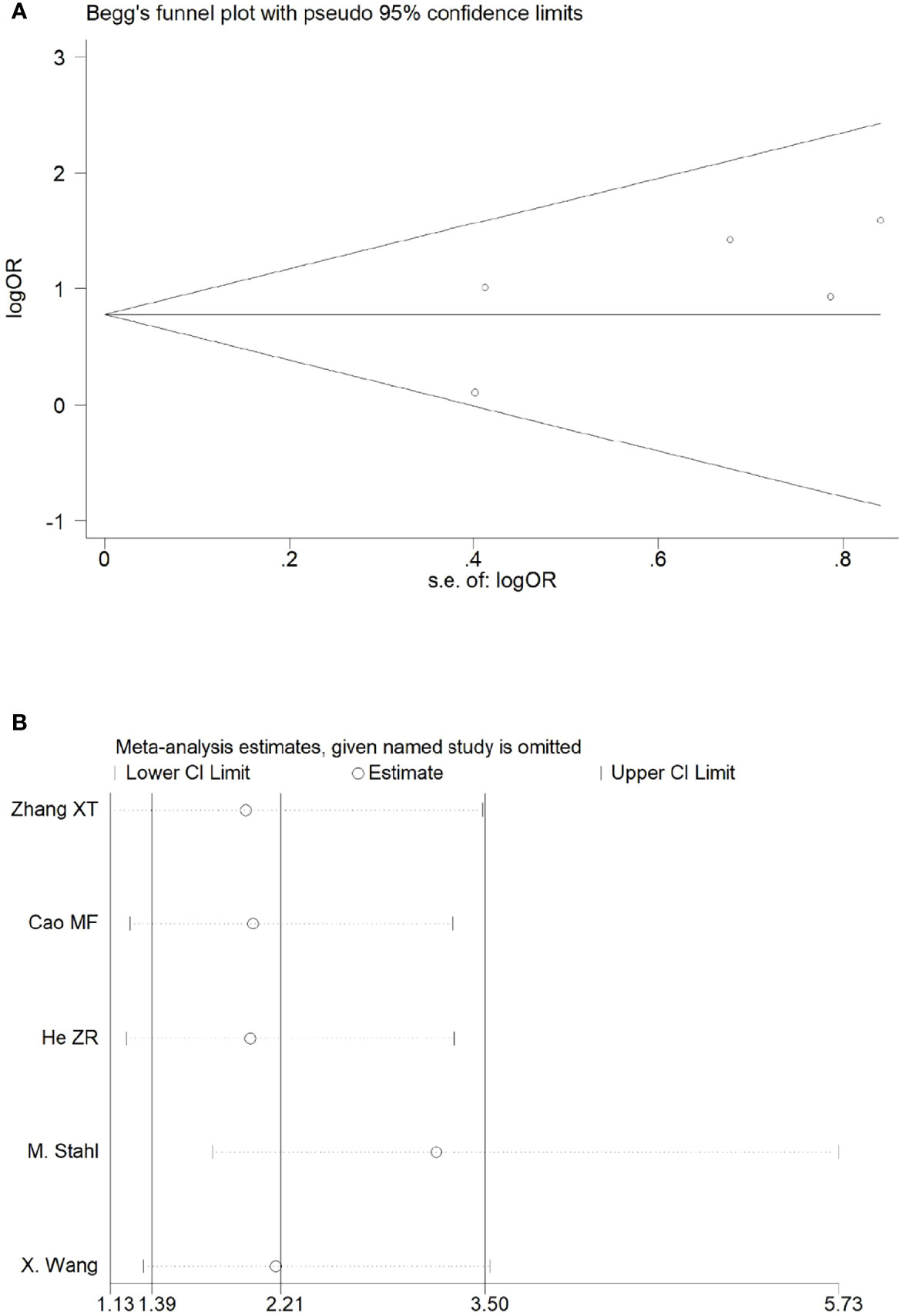

Of the included articles, five studies reported R0 resection rates. No heterogeneity was observed between the studies (p = 0.29, I2 = 19%); we therefore adopted the fixed effects model for meta-analysis, which showed that the R0 resection rate in the NACRT group was higher than that in the NACT group (OR = 2.21, 95% CI: 1.39–3.50, p = 0.0008) and that the results were statistically significant (Figure 5B).

Two studies reported the 1-year survival rate, and three studies reported the 3-year survival rate. Due to the lack of heterogeneity between the studies (p = 0.41, I2 = 0% and p = 0.31, I2 = 15%), we adopted the fixed effects model for meta-analysis, which showed that the 1-year survival rate in the NACRT group was higher than that in the NACT group (OR = 3.51, 95% CI: 1.40–8.81, p = 0.007), and the 3-year survival rate in the NACRT group was also higher than that in the NACT group (OR = 2.14, 95% CI: 1.30–3.50, p = 0.003). The results were all statistically significant (Figures 5C, D).

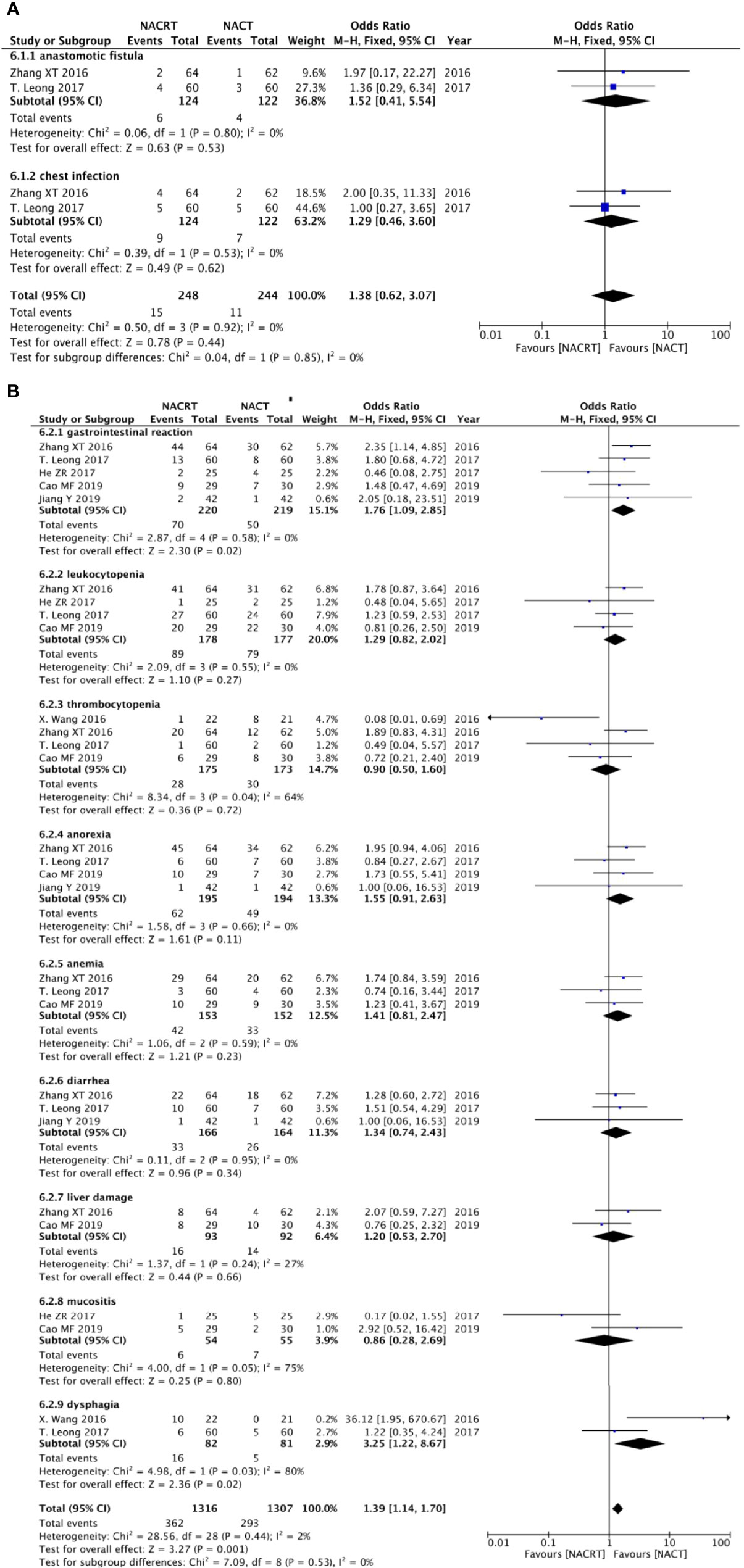

Two of the included articles reported anastomotic leak, and two studies reported abdominal infection. Because no heterogeneity was found between the studies (p = 0.80, I2 = 0% and p = 0.53, I2 = 0%), we adopted the fixed effects model for meta-analysis, which showed that there was no difference in the incidence of anastomotic leak and abdominal infection between the two groups (Figure 6A).

Figure 6 Forest plot for postoperative complications (A) and adverse effects after neoadjuvant therapy (B).

There were five studies that reported gastrointestinal reaction, four studies reported leukocytopenia, four studies indicated thrombocytopenia, four studies reported anorexia, three reported anemia, three indicated diarrhea, two studies mentioned liver damage, two studies reported mucositis, and two studies indicated dysphagia. The results showed that there was no statistical significance in the incidence of adverse reactions, except gastrointestinal reactions that were higher in the NACRT group than in the NACT group (OR = 1.76, 95% CI: 1.09–2.85, p = 0.02), and this result was statistically significant (Figure 6B).

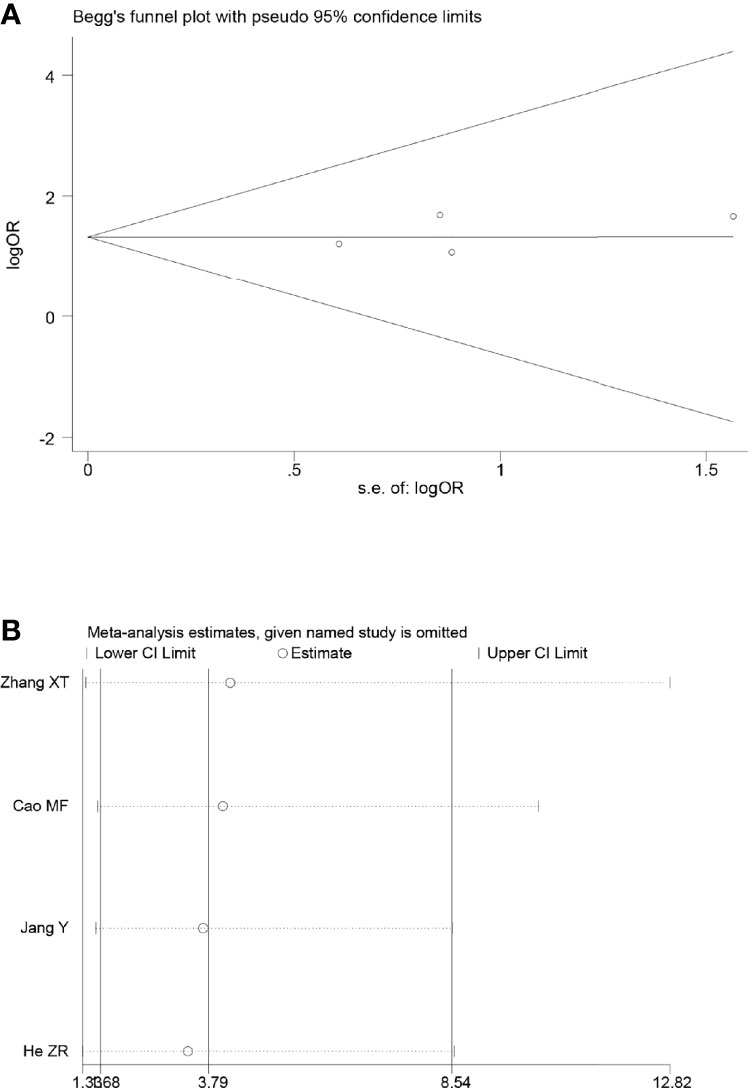

Sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding one study at a time, to assess the influence of each study on the overall results. The results showed that the deletion of any one study had no significant effect on the results (Figures 7B–11B), indicating that the results of this meta-analysis are relatively stable. The publication bias analysis of the seven included articles showed that there was no obvious publication bias in the CR, PR, ORR, pCR rate, and R0 resection rate. Begg’s funnel plot indicated no significant publication bias (Figures 7A–11A).

Figure 7 Begg’s funnel plot (A) and sensitivity analysis (B) of all the included studies for the analysis of CR.

Figure 8 Begg’s funnel plot (A) and sensitivity analysis (B) of all the included studies for the analysis of the R0 resection rate.

Figure 9 Begg’s funnel plot (A) and sensitivity analysis (B) of all the included studies for the analysis of PR. .

Figure 10 Begg’s funnel plot (A) and sensitivity analysis (B) of all the included studies for the analysis of ORR. .

Figure 11 Begg’s funnel plot (A) and sensitivity analysis (B) of all the included studies for the analysis of the pCR rate.

Our study supports the efficacy and safety of NACRT compared to NACT for resectable gastric cancer. Neoadjuvant therapy is effective in reducing the volume of the primary tumor, tumor stage, and lymph node involvement to narrow the range of surgical resection, improve the R0 resection rate, and prolong the survival cycle (19, 20). In addition, neoadjuvant therapy can reduce or eliminate the risk of residual tumor cells and distant metastasis, which are considered to be closely associated with postoperative recurrence and metastasis. Some studies have also shown that pathological reactions after neoadjuvant therapy are closely associated with a reduction in the recurrence rate and overall survival (21–27). Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy + surgery + postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy has become the standard treatment for resectable esophagogastric junction cancer (10). However, the choice of preoperative neoadjuvant therapy for non-esophagogastric junction cancer remains controversial (28, 29). Whether neoadjuvant chemotherapy should be combined with radiotherapy requires more clinical studies to prove its efficacy and safety.

This systematic review included seven RCTs involving 601 patients. The results of our study showed that the NACRT group had an increased number of patients with CR, ORR, and pCR; improved R0 resection rate; and 1-year and 3-year survival rates. In our meta-analysis, the average ORR rate of the NACRT group in the four enrolled articles was 79.1%, compared to 57.9% in the NACT group, and the highest ORR rate was 96% in the study by He ZR (13). Of the seven studies, five reported R0 resection rates; the average R0 resection rate was 83.28% in the NACRT group and 66.31% in the NACT group. In terms of 1-year and 3-year survival rates, the NACRT group had higher survival rates than the NACT group, and the results were statistically significant. Two of the included studies reported the median survival time; the NACRT group had a significantly longer median survival time [27.5 m vs. 22.5 m in the study by Zhang XT (17), and 30.8 m vs. 21.1 m in the study by Stahl M (15)] These results provide sufficient evidence for the efficacy of NACRT in resectable gastric cancer. Moreover, there was no difference in the incidence of adverse effects (except for the occurrence rate of gastrointestinal reactions) and postoperative complications between the two groups after neoadjuvant therapy. In conclusion, it stands to reason that the patients of resectable gastric cancer benefit from NACRT.

Some challenges remain before NACRT can become a standard treatment strategy. First, the adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapies have always been complementary. Results from the CRITIC study of chemotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy after surgery and preoperative chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer showed that postoperative chemoradiotherapy did not improve overall survival (30). However, in the current analysis, only patients who started their allocated postoperative treatment were included, and the per-protocol (PP) analysis of patients who started the allocated postoperative treatment showed that the chemotherapy group had a significantly better 5-year overall survival than the chemoradiotherapy group (31). This study was based on adjuvant therapy administered after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. If neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy is widely used, the choice of postoperative adjuvant therapy should be explored. Second, there are likely biological differences between Eastern and Western countries. Most of our studies were from China, and whether NACRT works for Westerners remains unknown (32). Furthermore, as mentioned above, NACRT is proven to be effective for resectable esophagogastric junction cancers, and the current debate is only about non-esophagogastric junction cancers. Some of our enrolled studies did not clearly define non-esophagogastric junction cancer as the inclusion criteria that might have caused some discrepancy in our research.

This meta-analysis has certain limitations. First, although the included studies were all RCTs, the sample size of some studies was small. Second, the interventions of the enrolled studies, the chemotherapy regimen, or the recommended dose of radiotherapy were inconsistent, which may have caused some degree of bias. The outcome indicators mentioned in this article are not identical. Jiang Y regarded the ORR as the primary efficacy outcome and not the R0 resection rate (12). Leong T [the Trial Of Preoperative therapy for Gastric and Esophagogastric junction AdenocaRcinoma (TOPGEAR)] only reported the interim results regarding adverse effects after neoadjuvant therapy and postoperative complications, whereas we expected the final results of this randomized, phase III trial (14). Several ongoing studies have not published their results (such as the PREACT trial), and we believe that their final results will help our research (33).

In conclusion, our meta-analysis demonstrated the efficacy and safety of NACRT for resectable gastric cancer, providing clinical support for its wide application. However, since some clinical trials have not yet reached their end points, the long-term outcomes and toxicity must be examined to confirm this conclusion.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

JC, YX, and LZ contributed to the conception and design of the study. JC and YY organized the databases and provided methodological support. YG, MF, and YZ performed the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by a key program from the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 81972845; Introduction of Specialist Team in Clinical Medicine of Xuzhou under Grant 2019TD003; Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (SJCX22_1273).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2022.927119/full#supplementary-material

1. Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van Grieken NC, Lordick F. Gastric cancer. Lancet (2020) 396(10251):635–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31288-5

2. Zhang X-Y, Zhang P-Y. Gastric cancer: Somatic genetics as a guide to therapy. J Med Genet (2017) 54(5):305–12. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-104171

3. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin (2021) 71(3):209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

4. Fujitani K. Overview of adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy for resectable gastric cancer in the East. Dig Surg (2013) 30(2):119–29. doi: 10.1159/000350877

5. Knight G, Earle CC, Cosby R, Coburn N, Youssef Y, Malthaner R, et al. Neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy for resectable gastric cancer: A systematic review and practice guideline for North America. Gastric Cancer (2013) 16(1):28–40. doi: 10.1007/s10120-012-0148-3

6. Yan Y, Yang A, Lu L, Zhao Z, Li C, Li W, et al. Impact of neoadjuvant therapy on minimally invasive surgical outcomes in advanced gastric cancer: An international propensity score-matched study. Ann Surg Oncol (2021) 28(3):1428–36. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-09070-9

7. Reddavid R, Sofia S, Chiaro P, Colli F, Trapani R, Esposito L, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer. Is it a must or a fake? World J Gastroenterol (2018) 24(2):274–89. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i2.274

8. Ajani JA, Mansfield PF, Janjan N, Morris J, Pisters PW, Lynch PM, et al. Multi-institutional trial of preoperative chemoradiotherapy in patients with potentially resectable gastric carcinoma. J Clin Oncol (2004) 22(14):2774–80. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.015

9. Ajani JA, Winter K, Okawara GS, Donohue JH, Pisters PWT, Crane CH, et al. Phase II trial of preoperative chemoradiation in patients with localized gastric adenocarcinoma (RTOG 9904): quality of combined modality therapy and pathologic response. J Clin Oncol (2006) 24(24):3953–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4840

10. Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Bentrem DJ, Chao J, Corvera C, Das P, et al. Esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancers, version 2.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw (2019) 17(7):855–83. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0033

11. C MF, P T, W GQ, S ZB, Z Y, G Q, et al. Comparative observation of neoadjuvant concurrent chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy alone in the treatment of stage III esophageal and gastric junction adenocarcinoma. Shandong Med J (2019) 59(8):61–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4840

12. J Y, J S, S Q. Application of preoperative imRT combined with concurrent capecitabine chemotherapy with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in advanced gastric cancer. China Foreign Med Treat (2019) 38(10):118–20. doi: 10.3322/caac.21657

13. H ZR, G WG, H JX, S HB. Effect of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy on locally advanced gastric cancer. Heilongjiang Med J (2017) 30(2):253–6. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.641304

14. Leong T, Smithers BM, Haustermans K, Michael M, Gebski V, Miller D, et al. TOPGEAR: A randomized, phase III trial of perioperative ECF chemotherapy with or without preoperative chemoradiation for resectable gastric cancer: interim results from an international, intergroup trial of the AGITG, TROG, EORTC and CCTG. Ann Surg Oncol (2017) 24(8):2252–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5830-6

15. Stahl M, Walz MK, Riera-Knorrenschild J, Stuschke M, Sandermann A, Bitzer M, et al. Preoperative chemotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced adenocarcinomas of the oesophagogastric junction (POET): Long-term results of a controlled randomised trial. Eur J Cancer. (2017) 81:183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.04.027

16. Stahl M, Walz MK, Stuschke M, Lehmann N, Meyer HJ, Riera-Knorrenschild J, et al. Phase III comparison of preoperative chemotherapy compared with chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. J Of Clin Oncol (2009) 27(6):851–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.0506

17. Zhang XT, Zhang Z, Liu L, Xin YN, Xuan SY. Comparative study of neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced gastric cancer. Chin J Cancer Prev Treat (2016) 23(11):739–43. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0126-4

18. Wang X, Zhao DB, Jin J, Chi Y, Yang L, Tang Y, et al. A randomized phase II trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared with chemoradiation therapy in locally advanced gastroesophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma: Preliminary results. Int J Radiat Oncol (2016) 96(2):S32. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.06.090

19. Joshi SS, Badgwell BD. Current treatment and recent progress in gastric cancer. CA Cancer J Clin (2021) 71(3):264–79. doi: 10.3322/caac.21657

20. Sun J, Wang X, Zhang Z, Zeng Z, Ouyang S, Kang W. The sensitivity prediction of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer. Front Oncol (2021) 11:641304. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.641304

21. Anderson E, LeVee A, Kim S, Atkins K, Guan M, Placencio-Hickok V, et al. A comparison of clinicopathologic outcomes across neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment modalities in resectable gastric cancer. JAMA Netw Open (2021) 4(12):e2138432. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.38432

22. Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, Van de Velde CJH, Nicolson M, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med (2006) 355(1):11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055531

23. Kano M, Hayano K, Hayashi H, Hanari N, Gunji H, Toyozumi T, et al. Survival benefit of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with s-1 plus docetaxel for locally advanced gastric cancer: A propensity score-matched analysis. Ann Surg Oncol (2019) 26(6):1805–13. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07299-7

24. Kochi M, Fujii M, Kanamori N, Kaiga T, Takahashi T, Kobayashi M, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with s-1 and CDDP in advanced gastric cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol (2006) 132(12):781–5. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0126-4

25. Ruf C, Thomusch O, Goos M, Makowiec F, Illerhaus G, Ruf G. Impact of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with PELF-protocoll versus surgery alone in the treatment of advanced gastric carcinoma. BMC Surg (2014) 14:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-14-5

26. Tian S-B, Yu J-C, Kang W-M, Ma Z-Q, Ye X, Yan C, et al. Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy treatment on prognosis of patients with advanced gastric cancer: A retrospective study. Chin Med Sci J (2015) 30(2):84–9. doi: 10.1016/S1001-9294(15)30017-1

27. Ychou M, Boige V, Pignon J-P, Conroy T, Bouché O, Lebreton G, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: An FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trial. J Clin Oncol (2011) 29(13):1715–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0597

28. Sah BK, Zhang B, Zhang H, Li J, Yuan F, Ma T, et al. Neoadjuvant FLOT versus SOX phase II randomized clinical trial for patients with locally advanced gastric cancer. Nat Commun (2020) 11(1):6093. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19965-6

29. Song Z, Wu Y, Yang J, Yang D, Fang X. Progress in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer. Tumour Biol (2017) 39(7):1010428317714626. doi: 10.1177/1010428317714626

30. Cats A, Jansen EPM, van Grieken NCT, Sikorska K, Lind P, Nordsmark M, et al. Chemotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy after surgery and preoperative chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer (CRITICS): An international, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol (2018) 19(5):616–28. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30132-3

31. de Steur WO, van Amelsfoort RM, Hartgrink HH, Putter H, Meershoek-Klein Kranenbarg E, van Grieken NCT, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy is superior to chemoradiation after D2 surgery for gastric cancer in the per-protocol analysis of the randomized CRITICS trial. Ann Oncol (2021) 32(3):360–7. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.11.004

32. Sano T. Adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapy of gastric cancer: A comparison of three pivotal studies. Curr Oncol Rep (2008) 10(3):191–8. doi: 10.1007/s11912-008-0030-y

33. Liu X, Jin J, Cai H, Huang H, Zhao G, Zhou Y, et al. Study protocol of a randomized phase III trial of comparing preoperative chemoradiation with preoperative chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer or esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma: PREACT. J Clin Oncol (2019) 27:851–6. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5728-8

Keywords: resectable gastric cancer, gastrointestinal cancers, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, meta-analysis

Citation: Chen J, Guo Y, Fang M, Yuan Y, Zhu Y, Xin Y and Zhang L (2022) Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for resectable gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 12:927119. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.927119

Received: 23 April 2022; Accepted: 28 June 2022;

Published: 05 August 2022.

Edited by:

Emilio Francesco Giunta, Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, ItalyReviewed by:

Johan Nicolay Wiig, Oslo University Hospital, NorwayCopyright © 2022 Chen, Guo, Fang, Yuan, Zhu, Xin and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yong Xin, ZGVlcDM2OUAxNjMuY29t; Longzhen Zhang, anN4eWZ5emx6QDEyNi5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.