94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol. , 10 May 2022

Sec. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention

Volume 12 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.832657

This article is part of the Research Topic Cancer Prevention, Treatment and Survivorship in the LGBTQIA Community View all 15 articles

Jane M. Ussher*†

Jane M. Ussher*† Rosalie Power†

Rosalie Power† Janette Perz

Janette Perz Alexandra J. Hawkey

Alexandra J. Hawkey Kimberley Allison and on behalf of The Out with Cancer Study Team

Kimberley Allison and on behalf of The Out with Cancer Study TeamBackground: Awareness of the specific needs of LGBTQI cancer patients has led to calls for inclusivity, cultural competence, cultural safety and cultural humility in cancer care. Examination of oncology healthcare professionals’ (HCP) perspectives is central to identifying barriers and facilitators to inclusive LGBTQI cancer care.

Study Aim: This study examined oncology HCPs perspectives in relation to LGBTQI cancer care, and the implications of HCP perspectives and practices for LGBTQI patients and their caregivers.

Method: 357 oncology HCPs in nursing (40%), medical (24%), allied health (19%) and leadership (11%) positions took part in a survey; 48 HCPs completed an interview. 430 LGBTQI patients, representing a range of tumor types, sexual and gender identities, age and intersex status, and 132 carers completed a survey, and 104 LGBTQI patients and 31 carers undertook an interview. Data were analysed using thematic discourse analysis.

Results: Three HCP subject positions – ways of thinking and behaving in relation to the self and LGBTQI patients – were identified:’Inclusive and reflective’ practitioners characterized LGBTQI patients as potentially vulnerable and offered inclusive care, drawing on an affirmative construction of LGBTQI health. This resulted in LGBTQI patients and their carers feeling safe and respected, willing to disclose sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) status, and satisfied with cancer care. ‘Egalitarian practitioners’ drew on discourses of ethical responsibility, positioning themselves as treating all patients the same, not seeing the relevance of SOGI information. This was associated with absence of LGBTQI-specific information, patient and carer anxiety about disclosure of SOGI, feelings of invisibility, and dissatisfaction with healthcare. ‘Anti-inclusive’ practitioners’ expressed open hostility and prejudice towards LGBTQI patients, reflecting a cultural discourse of homophobia and transphobia. This was associated with patient and carer distress, feelings of negative judgement, and exclusion of same-gender partners.

Conclusion: Derogatory views and descriptions of LGBTQI patients, and cis-normative practices need to be challenged, to ensure that HCPs offer inclusive and affirmative care. Building HCP’s communicative competence to work with LGBTQI patients needs to become an essential part of basic training and ongoing professional development. Visible indicators of LGBTQI inclusivity are essential, alongside targeted resources and information for LGBTQI people.

Attention to the nature and impact of interactions between oncology healthcare professionals (HCPs) and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (trans), queer, and intersex (LGBTQI) patients is increasing (1, 2). This follows recognition of the vulnerability and unique concerns of this underserved patient population, who have a high rate of unmet needs (3–6). LGBTQI individuals are at higher risk of cancer compared with the general population (4, 5, 7), but are less likely to engage in cancer screening or have a regular healthcare provider (8–10). More specifically, LGBTQI patients report high levels of dissatisfaction with cancer healthcare (3, 11), barriers to accessing cancer services (3), and difficulties in communication with HCPs (4, 12). This includes heteronormative assumptions on the part of HCPs, or overt HCP hostility and discrimination, leading to LGBTQI patient anxiety associated with disclosure of sexual orientation or gender identity (SOGI) (4, 12–14). The absence of LGBTQI-specific cancer information or support serves to render LGBTQI people and their carers invisible (4, 15). Unique psychosocial challenges are often not acknowledged or addressed by HCPs, including sexual concerns related to same-gender relationships (15–17), the impact of minority stress (18), absence of support from biological family (6, 19), and the specific concerns of trans and intersex individuals (20–22). As a result, many LGBTQI individuals report anxiety, isolation and frustration throughout their cancer care (3, 4), leading to higher rates of distress (20, 23, 24) and lower quality of life (18), compared with the general cancer population.

Awareness of the unmet needs of LGBTQI patients has led to calls for HCPs to be trained in the practice of inclusive and affirmative cancer care (3, 5, 6), variously described as cultural competence (2, 25–27), cultural humility (28), or cultural safety (29). Whilst these concepts were originally developed to address health inequities experienced by indigenous people (30), they are increasingly being applied to other marginalised populations (29), including LGBTQI people (31). Culturally competent healthcare involves cultural awareness, cultural knowledge and cultural skill, applied in all areas of practice, including the clinical setting, administration, policy development, and HCP education (32). The concept of cultural humility places less emphasis on acquisition of specific communication skills, focusing on the ongoing commitment of HCPs to engage in self-reflection and to addressing power imbalances implicit in patient-HCP interactions through open and empathic supportive interactions (30, 33, 34). Cultural safety focuses on creating an environment within the healthcare system that is emotionally, socially and physically safe, with no actions taken to challenge or diminish the identities of an individual (30, 35). HCPs who practice cultural safety are responsive to the personal circumstances and cultural needs of their patients and are free from bias and discrimination in a way that the patients experience as safe (30, 35). Inclusive and affirmative LGBTQI cancer care involves these three complementary concepts: cultural competence, cultural humility and cultural safety.

Consideration of oncology HCPs’ perspectives is central to identifying barriers and facilitators of the provision of inclusive and affirmative LGBTQI cancer care (2). Greater knowledge of LGBTQI healthcare needs is associated with positive attitudes and intentions to offer inclusive and affirmative care for LGBTQI cancer patients (36–38). However, surveys of oncology physicians (1, 2, 37), radiation therapists (39), nurses and other advanced care professionals (36, 38, 40, 41) consistently report low levels of knowledge about LGBTQI patients. This includes lack of knowledge about cancer risk factors and psychosocial vulnerabilities specific to LGBTQI people (1, 38, 40), and feeling ill-informed about LGBTQI cancer patients’ unique needs (2, 39, 42). Lack of knowledge has implications for HCP confidence and comfort in treating LGBTQI patients (1, 2, 37), with sexual health (43), fertility (44), and the needs of trans (1, 14, 45) and intersex patients (41) being areas where communication challenges are most likely. Moreover, even the majority of HCPs who report being comfortable treating LGBTQI patients in cancer care surveys (1, 2, 40, 42), report a desire for education and training (1, 36, 37, 41) focused on the needs and best ways of working with the LGBTQI population.

A number of strategies and models have been developed to raise HCPs awareness of LGBTQI patients, with the aim of improving communicative competence (4, 6, 28, 42). Such models operate on the premise that if HCPs are knowledgeable of the unique needs of LGBQTI patients with cancer, and provided with guidelines on how to communicate appropriately, they will do so. Underpinning these models and strategies is a ‘one size fits all’ approach, which assumes a universality of context and complexity in HCP-LGBTQI patient interactions. This does not account for HCPs often engaging in negotiating information provision and communication on a case-by-case basis, in a context that is shaped by the interaction of structural, personal and socio-cultural constraints (43). Little attention has been paid to the ways in which socio-cultural constructions of LGBTQI people, and the subject positions adopted by HCPs in relation to LGBTQI patients, inhibit or facilitate the provision of affirmative and inclusive cancer care, and the impact of HCP subject positions on patients. This is the focus of the present study.

It has been recognized that it is important to understand the “nuances of communication” that occur between HCPs and LGBTQI patients, in particular challenges in when and how to address sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) disclosure (14), in order to develop effective and targeted communicative competence interventions for HCPs. It is also important to be cognizant of the intersection of identities of LGBTQI patients, including age, sexual orientation, gender identity and cultural background, which may influence healthcare interactions (20). With the exception of two mixed-methods studies that included open-ended survey responses (14, 45), previous research on HCP perspectives on LGBTQI cancer care has utilized quantitative survey methods. There is a need for in-depth qualitative methods, including interviews and open-ended survey responses, to develop deeper, richly textured insight into the subject positions adopted by HCPs in relation to LGBTQI cancer care, and the implications of HCP positioning and practice for patients (43, 45). There is also a need for research that includes the perspectives of medical, nursing and allied HCPs, as well as those in leadership positions, in a range of clinical settings (37), reflecting the multidisciplinary model of care cancer (46). Most published studies to date focus on USA-based oncology physicians (1, 2, 37, 45), with a minority including oncology social workers (42), advanced healthcare practitioners (36), or nurses (38).

Research on the perspectives of LGBTQI cancer patients has identified that in the absence of visible indicators (e.g., rainbow flag) that health care settings or individual HCPs are inclusive and affirmative, many LGBTQI people fear that they will face HCP hostility and discrimination, and be offered substandard cancer care (4, 12, 13, 47, 48). Patients who experience negative HCP reactions can experience distress and disengagement with cancer care (4, 12, 13). Previous research on patient perspectives on interactions with oncology HCPs has focused on cisgender adults with breast or prostate cancer, who identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual (4, 6, 20). There is need for research that includes the perspectives of LGBTQI individuals across a wider range of cancer types, adolescents and young adults (AYAs), as well as transgender, gender diverse and intersex people with cancer (20). There is also a need to include the perspectives of partners and other caregivers, an understudied group in cancer research who report high rates of distress (49, 50). For LGBTQI people, caregiving is often provided by ‘chosen family’ (51), which includes intimate partners and friends (19).

The aim of the present study was to examine the construction and experience of LGBTQI cancer care from the perspective of HCPs, LGBTQI patients and their caregivers, using qualitative methods. The research questions were: What subject positions do oncology HCPs occupy in relation to the provision of care to LGBTQI people? What are the implications of HCP positions for LGBTQI patients and their caregivers?

AYA, Adolescents and young adults

HCP, Healthcare professionals

iKT, Integrated knowledge translation

LGB, Lesbian, gay and bisexual

LGBQ, Lesbian, gay, bisexual and queer

LGBT, Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender

LGBTQI, Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and/or intersex

SGM, Sexual and gender minority

SOGI, Sexual orientation and gender identity

TGD, Transgender and gender diverse

This cross-sectional study was part of a broader mixed-methods project, the ‘Out with Cancer Study’ (41, 52). The overall project examined LGBTQI cancer and cancer care from the perspectives of LGBTQI patients and their caregivers, and HCPs; audited Australian cancer resources for LGBTQI cultural competence and reviewed international LGBTQI cancer resources; and produced targeted LGBTQI cancer resources and healthcare professional practice guidelines (Figure 1). This paper presents the analysis of qualitative survey responses and interviews related to interactions between oncology HCPs with LGBTQI patients and their partners and other caregivers (carers). The survey facilitated data collection from a large group of LGBTQI individuals, including a range of sexual and gender identities, ages, and tumor types, with the interviews allowing for in-depth exploration of experiences in a selected sub-section of survey respondents (Figure 1).

In the study design, data collection, analysis and dissemination, we drew on principles of integrated knowledge translation (iKT), a dynamic process of collaboration between researchers and knowledge users to achieve actionable research outcomes (53). Following principles of iKT, a steering committee comprising LGBTQI people with cancer, cancer HCPs and representatives from LGBTQI health and cancer support organizations were actively involved throughout all stages of the study. Ethics approval was provided by Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee (H12664). All participants provided informed consent.

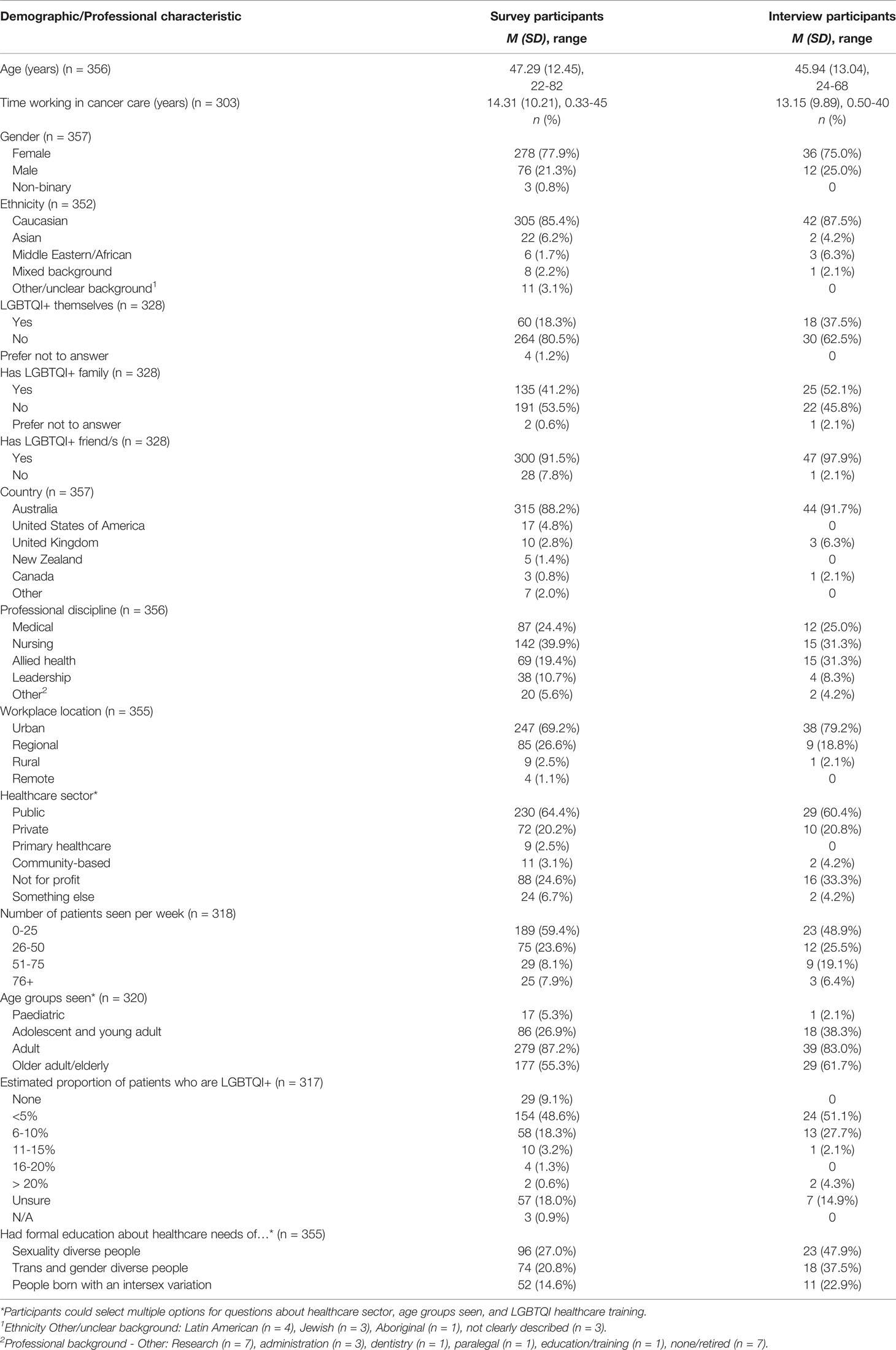

HCPs providing services to people with cancer and their carers were eligible to participate in this study. Participants were recruited through targeted advertisements on social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter), via professional networks (e.g., Clinical Oncology Society of Australia, Cancer Nursing Society of Australia) and through cancer-related community organizations. We specifically targeted oncology medical practitioners, nurses, allied health professionals (e.g., social workers, psychologists, occupational and physiotherapists) and individuals working in leadership roles in cancer care, health and preventative agencies such as support group leaders, program/service managers and consumer representatives/advocates. The study procedures and quantitative survey results from HCPs have been published elsewhere (41). Briefly, a sample of 357 HCPs working with people with cancer in nursing (40%), medical (24%), allied health (19%) and leadership (11%) positions, took part in an online anonymous survey. The majority (88%) were based in Australia, with a mean age of 47 (SD =10), and an average of 14 years’ experience in cancer care (see Table 1 for HCP demographics). Survey participants were invited to volunteer for a follow-up interview to examine their perspectives on LGBTQI cancer care in more detail. Of those who agreed to participate, a subset of 48 HCPs was selected, representing a range of professional backgrounds and gender identities. The one-to-one interviews lasted between 30 to 60 minutes, and were recorded. The study was open to HCPs from May 2020 to March 2021.

Table 1 Sociodemographic and Professional Characteristics of Participating Health Care Professionals.

A sample of 430 LGBTQI people who currently or previously had cancer (patients) with a range of tumor types and 132 partners or other caregivers (carers), aged 15 years and older, took part in an online anonymous survey, the details and results of which are published elsewhere (54). Table 2 contains demographic details of the survey participants, by patients and carers. The majority of patients were living in Australia (72.3%), Caucasian (85.2%), and identified themselves as lesbian, gay or homosexual (73.7%), with 10.9% identifying as bisexual, and 10.5% as queer. Greater diversity was evident in participants’ gender identities: 50.2% were cis women, 33.7% cis men, 16.1% TGD. Thirty-one (7.2%) participants reported intersex variation. The average patient age was 52.5 years (SD 15.7), with 22% in the AYA age-group (age 16-39).

Survey participants were invited to take part in an interview for the purpose of understanding their experiences in greater depth. A subset of 104 LGBTQI patients and 31 partners/carers, representing a cross-section of participants in gender, sexuality, age and tumor type, completed a 60-minute interview. Table 3 provides a demographic breakdown of interview participants, by gender, sexuality and intersex status. The study was open internationally, although recruitment focused on Australia and other English-speaking countries such as the USA, UK, New Zealand and Canada. Participants were recruited through social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram), cancer and LGBTQI community organizations (including the study partner organizations), cancer research databases (e.g., Register 4, ANZUP), LGBTQI community events (e.g., Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras) and cancer support groups. The study was open to LGBTQI patients and their partners/carers from September 2019 to September 2021.

The HCP survey (41) assessed attitudes toward LGBTQI cancer care, knowledge of LGBTQI health needs and LGBTQI inclusive practice behaviors. At the end of each section, HCP participants were asked to provide written responses to the open-ended question, “is there anything you would like to tell us about your answers to these questions?”. The LGBTQI patient survey assessed demographics, minority stress, disclosure, satisfaction with care, health literacy, end of life care issues, social support and relationships and sexual, physical and emotional wellbeing [described in (54)]. The carer survey assessed the same items, with the addition of items about caregiving experiences. At the end of most quantitative items, LGBTQI patients and partners/carers were asked to provide written responses to the open-ended question, “is there anything you would like to tell us about this issue?”, with responses ranging from one sentence to 15 sentences, with an average of 2 sentences. This paper focuses on qualitative responses to items on HCP interactions and the provision of cancer care, across participant groups.

Semi-structured interviews with HCPs, LGBTQI patients and carers were completed over the telephone or online using videoconferencing software, depending on the preference of the participant. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatum. Healthcare professionals were asked about their experiences providing care for LGBTQI patients, including how they identified LGBTQI patients, how well their workplaces were meeting the needs of LGBTQI patients and carers, and what they considered were important issues for LGBTQI patients and carers. LGBTQI patients and carers were asked about their experiences of cancer care, including interactions with HCPs, decision-making pertaining to disclosure of their LGBTQI status and the consequences of this for their cancer care; the impact of cancer on their lives, including on their identities; relationships and sexual wellbeing; support networks and experiences of finding information as an LGBTQI cancer patient. This paper focuses on HCP interactions and disclosure of LGBTQI status in cancer care.

Thematic discourse analysis or decomposition (55–57) was used to examine the qualitative survey responses and interviews. This analytic technique combines post-structuralist discursive approaches (58, 59) with thematic analysis (60), informed by the notion that meanings are socially formed through discourse (61). In this context, discourse refers to a ‘set of statements that cohere around common meanings and values… (that) are a product of social factors, powers and practices, rather than an individual’s set of ideas’ [(62), p.231]. Discourse analysis focuses on the subject positions that are taken up in talk, and their consequences in interactions for the self and others, including the way someone speaks or is spoken to, how a speaker describes herself and others, and the broader social discourse that a speaker draws upon (63, 64). Once a person takes up a particular subject position, they see the world from the vantage point of that position, influenced by the “particular images, metaphors, storylines and concepts which are made relevant within the particular discursive practice in which they are positioned” (61). Subject positions are not fixed, and are not properties of the individual, which means that participants may adopt more than one subject position, or move between subject positions (61). The possibility of choice is implicitly present, because there are many potentially contradictory discursive practices in which each person could engage (61).

The focus of analysis in this paper is on the subject positions made available to oncology HCPs through discourse and the implications of these subject positions for LGBTQI patients and carers. The analysis was conducted using an inductive approach, with the development of discursive themes and identification of subject positions being data driven, rather than based on pre-existing research on HCP interactions with LGBTQI cancer patients and carers. HCP, patient and carer interviews were transcribed, verified for accuracy by reading the transcripts while listening to the audio-recording and then de-identified by replacing participant names with pseudonyms. Through a collaborative process with stakeholder committee members, a subset of interviews for HCPs, patients and carers were independently read and re-read to identify first-order codes within the HCP and patient/carer data sets that represented commonality across accounts, such as ‘lack of knowledge’, ‘discrimination’ (HCPs) ‘feeling unsafe’, ‘difficulties in communication’ (patients/carers). Each team member brought suggestions of the first order codes to the meeting and the final coding frames for HCPs and patients/carers were devised through a process of consensus. This included codes such as ‘culturally safe care, services and support’, ‘barriers to providing good LGBTQI care’, ‘experiences with LGBTQ patients and carers’ (HCPs); and ‘disclosure of identity’, ‘positive/negative interactions with HCPs’ (patients/carers). Open-ended survey and interview data were coded by four members of the research team using NVivo. Consistency in coding across codes and coders was checked by a senior member of the team. Coded data were read through and summarized in a tabular format to facilitate identification of commonalities in the data. The codes were then re-organized and grouped into discursive themes focused on subject positions adopted by HCPs in relation to LGBTQI cancer care and the implications of these subject positions for patients and carers. Themes were then refined through discussion, reorganized and, when consensus was reached, final themes and sub-themes developed. Throughout, the analysis was informed by an intersectional theoretical framework. This acknowledges the interaction and mutually constitutive nature of gender, sexual identity, age and other categories of difference in individual lives and social practices, and the association of these arrangements with health and wellbeing (65).

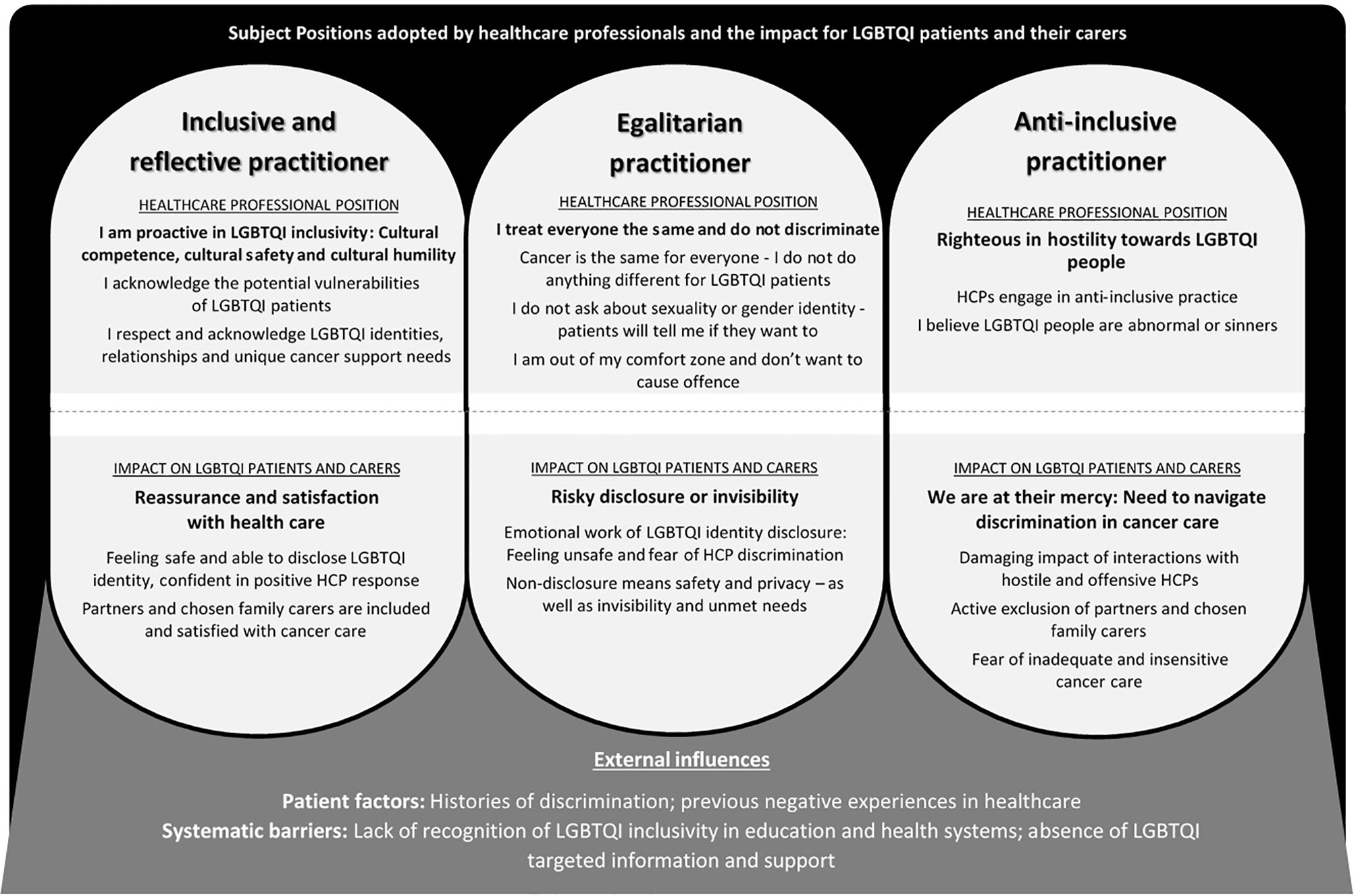

Three subject positions adopted by HCPs were identified (Figure 2): Inclusive and Reflective practitioner; Egalitarian practitioner; and Anti-Inclusive practitioner. HCPs adopted these subject positions across the range of professional backgrounds, gender, sexual orientation and age groups. A number of HCPs adopted more than one subject position, with adoption of the Inclusive and Reflective Practitioner in some contexts and the Egalitarian Practitioner in others, identified. Each subject position had direct consequences for the positioning and experiences of LGBTQI patients and their carers (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Subject Positions Adopted by Health Care Professionals and the Impact for LGBTQI Patients and their Carers.

In the presentation of results below, we outline each HCP subject position, followed by the patient and carer accounts of interactions with HCPs who adopted this subject position. Key demographic details are provided for longer quotes; Med= medical practitioner, Allied = allied health worker. LGBTQI patients and carers are identified by pseudonyms (interview participants) or “survey”, with demographic details of age, SOGI and intersex status, and cancer type provided for longer quotes (medical intervention = intervention to prevent cancer). In the patient/carer sections, participants who are carers are identified as such; all other quotes are from patients. For readability, demographic details for HCP and LGBTQI patient/carer short quotes are provided in Table 4, alongside a longer version of the quote for readability.

HCPs who adopted a position of inclusive and reflective practice demonstrated cultural competence, proactively creating a place of cultural safety for LGBTQI patients and their partners through practicing cultural humility. The starting point was HCP awareness of the need to “differentiate between people depending on what their sexuality or their gender is” and being open to “change the way we care for people” [Izzie, Allied, 28, Straight], based on this knowledge. Cultural humility also involved HCPs acknowledging the potential vulnerability of LGBTQI people, who may need “more care” because of “extra mental health factors” resulting from “societal discrimination” and potential difficulties in “coming out to family”, or the “potential trauma involved in transitioning” [Amy, Nurse, 55, Lesbian]. HCP recognition of the “legacy of trauma” within healthcare contexts was also evident. This included a “legacy of fear” that LGBTQI identity is “not going to be recognized” or that partners will be excluded by HCPs. As a medical HCP commented:

There’s a legacy of fear within the queer community that you, as a queer person and your queer partner in a queer relationship, are not going to be recognized, and so if something takes a turn for the worse, in terms of somebody’s health, that the partner will be locked out of the room because they’re not officially married, and people fear that. [Suzanne, Med, 40, Queer]

Services could also be “scary” for “people who are intersex” and have had “medical interventions done to you”, meaning that interactions with HCPs in the context of cancer “could be a triggering thing” [Lexie, Allied, 27, Straight].

Inclusive and reflective practitioners recognized “barriers” to patient disclosure of LGBTQI identity within a cis-heteronormative healthcare context. For example, it was recognized that individuals “in that vulnerable situation” have to “go through hoops” and be “brave enough to speak up not knowing what the response is going to be” if they chose to disclose their LGBTQI identity, often having to correct the heteronormative “assumptions” of HCPs [Emily, Allied, 54, Lesbian]. For some HCPs, self-reflection as a “queer person”1 precipitated this awareness; for others it was from having LGBTQI friends or family, hearing a “talk at a conference”, or “doing my own research”. Interactions with LGBTQI patients could also result in a moment of enlightenment. For example, one HCP said, “it just really hit me, that it shouldn’t be this way” when a gay male patient “was more worried what I would think about him having a same-sex partner, than actually that he had cancer” [Patrick, Med, 57, Straight].

HCPs who adopted a position of inclusive and reflective practice endeavored to ensure LGBTQI patients and their partners felt “welcomed”2 and “safe”3 by facilitating supportive healthcare interactions within a model of person centred care. Actively demonstrating openness, understanding, respect and acceptance of LGBTQI identities and relationships without a sense of superiority were key attributes of this practice. This reflected an understanding among HCPs that “it’s actually more important to understand and respect who [patients] are before we start telling them what they should or shouldn’t do” [Ayomi, Med, 35, Straight]. Central to inclusive practice was respect for “people’s terminology and self-identification” as well as “really respecting and making their relationship or relationships visible”4. Understanding and respect were central to “collaborative decision-making and engagement of our patients”, manifested through “non-judgmental communication and support” and “meeting people where they are at”, rather than “pigeon-holing them in a certain place” [Paula, Program manager, 59, Lesbian].

Sensitivity to the unique meaning of treatment-induced changes for LGBTQI people was part of inclusive practice. This might include the impact of hair loss on “somebody who is trans and they’ve grown out their hair”5, “weight loss or weight gain on body image and identity for gay men”6, the need for information about the “resumption of anal sex after prostate radiotherapy”7, or safe sex information that “doesn’t focus on using a condom”8 for lesbian couples. Absence of support networks of some LGBTQI people was also acknowledged: “when you’re looking at an age group of gay men in their 50s and 60s. Life has been difficult for them. Often, they don’t have any family support. They rely on friends for their support” [Cindy, Nurse, 58, Straight]. However, at the same time, not “making assumptions” about the impact of cancer in an individual patient and a willingness to discuss patient needs and concerns were central to inclusive care.

It depends on the individual. If it’s important to them, I think it’s important that they know it’s a platform they are welcome to talk about it. And that’s why I think we need to have an environment that’s very welcoming, but not assume that everybody wants to declare everything all the time. [Melanie, Nurse, 50, Straight]

A cornerstone of inclusive and reflective practice was acknowledgement that it was the responsibility of HCPs to facilitate LGBTQI identity disclosure actively at first meetings with patients, through avoiding cis-heteronormative language and assumptions, “bringing things up proactively” [Russell, Med, 42, Gay]. This could be done through asking questions about “support networks” and “who somebody has in their life, who’s going to support them through their cancer diagnosis”9. This then gives the HCP the opportunity to acknowledge the patient’s SOGI status.

I will ask exploring questions around a partner, who’s caring for you, who’s around, who are your supports. And often that sort of open question, to just invite them to describe a bit more, enables them to say, “well, it’s my partner and she is”. And that sort of gives me the opportunity then to acknowledge that they’re same sex attracted [Alison, Allied, 66, Straight].

Directly addressing the question of gender identity by saying to a patient “I’m just going to ask you a few questions about sexuality and gender. And I was just wondering, you know, how do you identify?” can also serve to “provide the space” to allow people to “make the decision themselves as to how much they want to share with you” [Brooke, Nurse, 30, Straight] as a trans or non-binary person.

Respectful reflective practice includes recognition that it is important “to be aware that sometimes the name in the medical notes is not the preferred name” of trans and non-binary patients. This meant it was important “to be very sure, to never dead name them”10 [use the name given at birth, before gender affirmation]. If a HCP is unsure about terminology, the identity label, or the name a patient prefers to use, the solution was to “ask them” rather than worrying about “getting pronouns correct”. Avoiding incorrect heteronormative assumptions about the support person of a patient is also important. One HCP said “over the years I’ve found you can make judgments thinking it’s a brother, but it’s a partner or even a father” and thus the solution was to “ask them who they have come with today and often they’ll say, oh, this is my partner. We’ve been together X number of years” [Cindy, Nurse, 58, Straight].

Many HCPs recognized the positive impact of affirmative and inclusive practice on patients in a context where they might be expecting to experience prejudice or discrimination. One medical practitioner who welcomed a male patient’s male partner said, “it was almost like a wall of ice just broke. He [the patient] actually became teary almost of, like of relief” [Patrick, Med, 57, Straight]. A lesbian patient’s wife was described as initially “very defensive of their relationship and her place of next of kin” because of “backlash” at a previous religious hospital, but became “much calmer” once she was “aware that we [the HCPs] took her position as the patient’s partner and main support person seriously” [Survey, Nurse, 27, Straight]. Affirmative and reflective practitioners spent the time “establishing a relationship and letting them [LGBTQI patients] feel that they can talk to you if they want to”, knowing that “over time they tell you all sorts of things” if they feel “safe” [Cindy, Nurse, 58, Straight].

Most HCPs who adopted a position of inclusive and reflective practitioners accepted that it was the responsibility of HCPs to “do the work” to understand the evolving language and terms associated with SOGI identities, and “sit with” their own “discomfort”, if they were unsure about how to interact with LGBTQI patients, reflecting cultural safety and humility.

I think it should sit with us to do our own work to understand the history, to stay abreast of all the evolving language and terms. I think the discomfort as clinicians, we have to be the ones to sit with that. It should not be patients or their families who are feeling like they can’t either disclose important information for their care. And I think as individuals we need to figure out how we can provide better care and more equitable care across all of our patients and keep learning and pushing those agendas through our own teams and organizations [Brooke, Nurse, 30, Straight]

Inclusive and reflective HCPs acknowledged gaps in their own knowledge and confidence, with many commenting on the need for training and communication in addressing the needs of trans and intersex patients. For example, HCPs told us: “say you were a medical practitioner who had no idea what it was to be intersex or trans or non-binary gender, it’s really essential to do your own research and communicate with the patient around about exactly what their own goals and their beliefs and their values are” [Suzanne, Med, 40, Queer]; and “it’s even harder for somebody who’s gender nonconforming or trans to navigate the health care system. I didn’t really deal with that. I’m trying to, trying to learn and do better” [Emily, Allied, 54, Lesbian]. Lack of “support from the top” [Allison, Allied, 66, Straight] for HCP training and education on LGBTQI inclusivity made this process difficult: “We’re hungry for knowledge, I think we have the capacity. We just don’t know where to channel that capacity, and it would be nice to come from a place that’s official” [Amelia, Nurse, 34, Lesbian].

It was recognized that it was the responsibility of those designing healthcare settings and services to provide visible signifiers of inclusivity, such as rainbow flags, stickers and posters in waiting rooms, specific information for LGBTQI people on websites, and identification of gender diversity and sexual orientation on intake forms. This would be “comforting” and indicate “this is a safe space”, making a “big difference for the [LGBTQI] communities” for whom the healthcare setting is potentially “daunting”11. However, the majority of inclusive and reflective HCPs described visible signifiers of LGBTQI inclusion in their workplace as an ideal that they would like to aspire to, or “something we could do” to indicate “we respect and celebrate gender diverse individuals here”12, rather than the practice at their current place of work. Systemic barriers to signs of inclusivity included difficulties in “accessing the [LGBTQI] material … and we have to get approval from further up the line to do these sort of things” [Cindy, Nurse, 58, Straight]. Others identified the need for education of management and colleagues about LGBTQI inclusivity. For example, one HCP demonstrated agency in adding gender diversity and sexual orientation to patient registration forms and “that was promptly taken off because we had a few patient complaints”. She reflected that “in retrospect, I should have done a bit of teaching and said, ‘right, this is why we’re putting this on there’” [Naomi, Allied, 28, Straight]. Financial barriers in introducing “new models of care” were also identified: “I have to have the business-y, the budget-y hat on. How will this save money. Instead of spending more money. Because we are constrained by that” [Deborah, Nurse, 36, Straight]. These accounts indicate acknowledgement of the institutional barriers to provision of affirmative and inclusive cancer care.

LGBTQI patients and their carers described interactions with HCPs who adopted a position of inclusive and reflective practice as having direct and positive consequences. Visible signifiers of LGBTQI inclusivity, such as rainbow flags, provided “reassurance” that patients were “going to a safe space”, with “correct values” because of “knowing that the hospital you’re going to is going to be nonjudgmental and treat you as anybody else” [Nathan, Partner, 50, Gay, Head/Neck]. HCPs who were clearly comfortable working with LGBTQI patients served to facilitate feelings of safety, as a carer told us, “I was very lucky to have an accepting environment, especially in the aspects of [HCPs] being comfortable and making me feel safe” [Survey, Daughter, 20, Queer, Adrenal]. Interactions with HCPs who openly identified as part of the LGBTQI community were highly valued in relation to feelings of safety: “out medical staff made me feel safe”; “My GP is a lesbian. I feel very safe”.

Feeling safe meant that patients were confident in disclosure of LGBTQI identity, in the knowledge that they would be accepted without judgement, “my sexuality has mainly been treated as a non-issue. My GP is a gay man so it is openly discussed”12; “medical staff never judged my gayness”. Patients and carers commended HCPs who avoided heteronormative assumptions when asking questions, “my experience with the medical practitioners has been positive and inclusive. They have not presumed my sexuality and have asked open questions” [Survey, 43, Gay, Leukaemia]. A lesbian patient with lymphatic cancer praised HCPs who “interacted positively with my children, with my partner and with me”13, through asking her children what did they call their two mothers. Sensitivity of HCPs to LGBTQI patients’ fear of discrimination, as well as confidentiality in response to disclosure of identity, was also valued.

My medical team knew that I was transgender and that I feared discrimination. They were very supportive and went an extra step to reassure me. My status as a trans female remained as knowledge with only those that it impacted in my treatment [Survey, 68, Straight, Transgender Female, Head/Neck].

Many patients and carers positioned geographical location as a factor in instilling confidence that they would receive affirmative and inclusive healthcare. For example, participants told us, “I think living and being treated in the inner city means you can take a fair punt on disclosing to health professionals” [Survey, 75, Lesbian, Breast] and “I might not be as accepted as a lesbian in different parts of Sydney and in regional, rural or remote areas of Australia” [Survey, 55, Lesbian, Head/Neck]. Conversely, others valued living in a “rural, small-town area where everyone knows everyone” and which contributed to “being respected”14.

Partner and chosen family inclusion in decision-making processes and day-to-day interactions with HCPs was an important consequence of feeling safe and being able to disclose identity in an accepting and inclusive health care environment. Many patients introduced their partner at a first meeting, “I was deliberately out to my nurses and doctor who’s a world expert. They handled it well, acknowledged my husband, and we use joint decision-making” [Survey, 63, Gay, Prostate]. A lesbian patient said, “I had no trouble at all. My girlfriend participated in meetings and there was never an eyebrow raised or any exclusionary gestures made towards me or her” [Rita, Patient, 61, Lesbian, Cervical). Many partners reported that there was “no sign of [HCP] discomfort or not knowing how to handle it”, which meant that they “felt at ease being there as his same-sex partner”15.

HCPs who went beyond non-discriminatory practice in demonstrating cultural safety were highly valued by patients and their carers. One participant said that HCPs “embraced family irrespective of make-up of family”. The partner of a gay man said his husband’s GP had “no issue with (us) going in the consulting room together” and “were just so excited when we got married” [Anthony, Partner, 65, Gay, Prostate]. A lesbian participant described the warmth of HCPs towards her wife:

I usually introduce [wife’s name] as my wife, and we haven’t had anyone flinch or look twice or nothing. We’ve both been included in everything, so they’ll just call us in and just take both our hands on every occasion. Last time when we left the oncologist because my results were really promising he grabbed both of us and gave us a big hug and said ‘you are such a good team’ [Martha, 48, Lesbian, Bowel].

Being able to disclose LGBTQI identity and include partners and other chosen family without meeting prejudice or judgement was also associated with satisfaction with health care, with HCPs described as “brilliant”, “fantastic”, “excellent”, or “great”. For example, participants told us: “All the nurses knew. And all of them were great”; “My own GP is absolutely brilliant … very caring, nonjudgmental and he’s been very good”. Satisfaction was also linked to HCPs being “respectful”, a key attribute of inclusive care. As the trans intersex partner of a woman with breast cancer told us:

As far as the medical people have been with us, we had zero issues. They have always been respectful, and I would always go to an appointment … everyone in the hospitals, doctor’s surgery was brilliant. Surprisingly brilliant. There was never a problem [Kai, Partner, 50s, Bisexual, Trans, Intersex, Breast].

Others said “all of the medical staff involved treated me with respect. They also treated my wife with respect [and] I felt acknowledged and respected as a partner and carer” [Survey, 69, Lesbian, Endometrial]. HCPs acknowledging LGBTQI status, while treating the patient “as a person” was manifestation of this respect, “he just treats the person as a person he doesn’t go, ‘Oh well, I’m going to have to put a label on you now because you told me that you’re bisexual’” [Grace, 56, Bisexual, Cervical]. In combination, this resulted in the positioning of HCPs as “really fantastic in terms of communicating (and) supporting” [Ruby, Partner, 60, Lesbian, Bowel], “really great”, “really good”, and as “exceptional”.

HCPs who adopted the subject position of egalitarian practitioners reported that they treated “everyone the same”, regardless of gender and sexuality. Many HCPs stated that cancer was the same for everyone and “I don’t see that there’s a huge difference in the care of the cancer itself” [Omar, Med, 60, Straight], hence “I don’t think there’s a need to do anything different” for LGBTQI people [Patrick, Med, 57, Straight]. As long as patients were “getting good care for their cancers”, organizations were believed to be “doing enough”, with “other problems identified” being “referred to psychological services”, implicitly pathologizing LGBTQI identities [Kylie, Nurse, 60, Straight]. LGBTQI patients were considered to be no different from any other cancer patient in facing “concerns about survival and the concerns of recurrence of disease”, or in palliative care, “the same end of life physical, emotional and psychosocial issues”.

As a gastroenterologist I don’t think it’s that important. For treating cancer, so you’re talking about people coming in for chemotherapy, sitting for hours, feeling sick. I think there it might be important to have something visual for them … that you are welcome here. I don’t think in my context there’s necessarily a need to do anything different … we don’t have anything special for them [Patrick, Med, 57, Straight].

HCPs told us that information about “safe sex in regards to treatment … doesn’t need to be any different for a gay or straight person” [Darren, Allied, 53, Gay] and hence “I try to treat everyone the same”16. Some HCPs positioned others as responsible for affirmative and inclusive care, arguing that there was no need for acknowledgment of LGBTQI status in “frontline care work”, because “support services probably are doing all that stuff” [Melanie, Nurse, 50, Straight]. Others made a distinction between cancers of the reproductive organs, such as prostate and breast cancer that “might affect their identity” and cancers such as lung, gastrointestinal and bowel cancer “where the effect is the same. It’s kind of fairly similar regardless of your gender or your sexuality” [Ayomi, Med, 35, Straight]. Many egalitarian HCPs reported “comfort and confidence” in providing cancer care for LGBTQI patients even though they had not “looked outside for training or things that exist that could help my knowledge” [Cristina, Allied, 35, Straight].

Egalitarian HCPs believed that there was no need to “display anything” that was explicitly LGBTQI inclusive, such as “wear a rainbow lanyard”, or “do anything that says I’m one of the people you’re welcome to talk to” [Melanie, Nurse, 50, Straight] because they were “friendly to everyone” [Ken, Med, 50, Straight]. Drawing on discourses of ethical responsibility, these HCPs said that all patients were “given the same respect and care, no matter race colour or sexual outlook” [Valentina, Nurse, 56, Straight] and LGBTQI patients were treated “how I would treat every other patient” [Kylie, Nurse, 60, Straight]. A number of HCPs who adopted the position of egalitarian practitioner stated that they were unsure why there was a need to “single out a particular population” as “surely we are well past that”, and “if you start being too demonstrative being LGBT friendly, it almost … draws particular attention to it” [Brett, Med, 37, Gay]. Many HCPs positioned themselves as “inclusive” and non-discriminatory because they treat everyone equally, providing the same “high quality” service to “anyone who needs it [Cristina, Allied, 35, Straight].

I do think that we are quite inclusive and we don’t discriminate. Therefore … we’re treating everyone equally, and I think that’s what it should be about, is everyone getting equally good support [Darren, Allied, 53, Gay].

From this standpoint, LGBTQI identity disclosure was positioned as irrelevant to the provision of patient care, including disclosure of sexuality, gender identity and intersex status. This draws on a discourse of equality, suggesting that everyone is treated the same, rather than equity, whereby everyone is provided with what they need for good healthcare provision.

HCPs who adopted the position of egalitarian practitioner did not explicitly facilitate disclosure of LGBTQI status as it was assumed that “people that want to tell you and feel comfortable with you will tell you”17. As a result, disclosure was “very much patient-led”. Some healthcare professionals did use neutral language to ask about “social networks”, such as, “who’s in their life?” or “do you have a partner?”18 if they “sensed” or “picked up” that the patient may be LGBQTI, suggesting awareness of the importance of inclusivity. However, it was acknowledged that “if they didn’t have a partner then maybe it wouldn’t come up. It doesn’t get asked at all” [Amelia, Nurse, 35, Lesbian]. Patients who did not appear to the HCP to be LGBTQI would also be overlooked as the HCP would not adopt neutral language. Equally, identification of a person as trans, non-binary or having an intersex variation would not follow on from questions about social networks or partners, resulting in HCPs “missing people”.

I don’t tend to ask people. I don’t proactively ask people do you identify as LGBTIQ. I sort of pick up on it if it’s there. But, you know, that probably means that even I am missing people. Sometimes, I’ve been in a situation where I’ve had a trans patient, for example, and they just really pass. I’ve only realized that they are trans when I do a physical exam [Suzanne, Med, 40, Queer].

This HCP did demonstrate some reflectivity, commenting, “it’s maybe something that I could improve on in my own practice”, but explained “it’s not sort of something that’s taught to us”.

A number of HCPs accounted for the fact that they did not ask about LGBTQI status, or actively facilitate disclosure, by stating that they did not want to “make assumptions” due to the fear they would be seen to be “overstepping” or “going down a track that could be offensive” to non-LGBTQI patients [Darren, Allied, 53, Gay]. It was also argued that some “people that did identify [as LGBTQI] might think ‘it’s none of your business’” or might experience the HCP as voyeuristically “gaping” at them, or respond negatively to uninformed or “insensitive” HCP questions. Other HCPs were concerned about displaying LGBTQI inclusive signage because of concern “it would antagonize one or more of my conservative patients” [Lynette, Med, 58, Lesbian] and “there are still a lot of people out there who are not comfortable with gay and lesbian couples” [Patrick, Med, 57, Straight]. As a result, HCP participants said, “it’s probably better to stay neutral” and let “patients … identify to you” or “lead the conversation”19.

After a patient’s disclosure, a number of HCPs were concerned that they “would offend somebody because of my lack of information” [Katrina, Allied, 64 Straight] or were “worried about calling them the appropriate term”, “which could serve to “take away from them just being my patient and treating them well” [Survey, Nurse, 48, Straight]. More specifically, lack of knowledge and confidence in “language to do with transgender people” was described as making a number of HCPs feel “inadequate and probably a little bit embarrassed” or “nervous and cautious” [Kelly, Nurse, 60, Straight]. This was because of a fear that their “capacity to actually get it wrong is massive”, which could “cause offence or damage rapport” [Leanne, Allied, 47, Straight]. As a result of this “fear of stepping on toes with fear of being offensive”, many HCPs simply said “nothing at all”, which was acknowledged by some to be “not very good either” [Alia, Allied, 31, Straight].

HCPs who adopted a position of egalitarian practitioner and did not “open up” the discussion of SOGI status, were seen by patients and their carers as assuming a patient was “straight” and cisgender, and that their partner was “a friend”. This was a source of dissatisfaction with healthcare, which LGBTQI participants said, “really pisses me off” and “creates a lot of stress”, because “if they didn’t make that assumption automatically that I was heterosexual then I think it would have been a lot easier to handle” [Christine, 53, Lesbian, Ovarian and Uterine]. Failure to acknowledge gender diversity was also a concern for many patients.

What I would have liked them to do was to ask me what pronouns I would like. Would I like to be called ‘he’ or ‘him’ or ‘she’ and ‘her’ or ‘they’ and ‘them’. They didn’t ask [Lauren, 63, Queer, Trans, Prostate]

Egalitarian practice puts the onus on patients and their carers to disclose in a context where they are unsure about the response they will receive from HCPs. As one participant reported, “having to explain every time that you are not straight was another layer of things to worry about or have to deal with. I already had enough going on just with the treatment” [Survey, 56, Lesbian, Breast]. The “anxiety around disclosure” and repeated decision-making before an encounter with a new HCP about “when do I bring it up, how do I bring it up?” [Dylan, 32, Gay, Non-binary, Leukemia] was described as “emotionally extremely draining” [Scott, 55, Gay, Trans man, Multiple] and “a little bit wearing after a while” [Paulette, 67, Lesbian, Colorectal]. LGBTQI patients and their carers were thus “on a merry-go-round” of “outing yourself the whole time” as well as “outing your partner if they’re with you”. This meant they were leaving themselves open to HCPs “not being too receptive”, fearing that HCPs will “change their mindset and how they treat you” after disclosure. This was “emotional effort” and a “burden” on LGBTQI patients [Paulette, 67, Lesbian, Colorectal].

Being part of a marginalized community brings additional pressures and stresses, and the anticipation of potential discrimination, or everyday misunderstanding, is always there. This creates additional burdens which impact on health and wellbeing. This awareness needs to be out there [Survey, 52, Lesbian, Breast].

There were a number of ways LGBTQI patients and carers responded to their uncertainty about HCP responses to disclosure. Some individuals would assess “the vibes they [HCPs] give off”20 at a first meeting, or “call the doctor’s office and tell them in advance so I can gauge their reaction before I go in”. Selective disclosure on a “needs basis” was also reported, only happening if the patient “considered it relevant” to their care or felt confident in a positive HCP response. Others, most commonly older cisgender gay and lesbian cisgender individuals, said that they were “always open and honest with our providers”, and because I am “out and comfortable with who I am” or “proud of who I am. I don’t hide any more”, expecting “others to treat me accordingly, especially around such an emotional and fraught issue as cancer” [Survey, Carer, 77, Lesbian, Ovarian] and include their partner in all discussions. Some self-proclaimed “very out” participants reported a more “assertive” response, refusing to “tolerate any kind of homophobic bullshit”, or saying, “if you don’t like who I am, I don’t care, you’re shit” [Rita, 50, Lesbian, Cervical].

If HCPs who adopted a position of egalitarian practitioner responded positively to LGBTQI disclosure, this had positive consequences in terms of patient satisfaction, engagement with care and inclusion of partners, as reported in interactions with inclusive practitioners. For example, a carer of her partner with ovarian cancer, said she was “always wary wherever I am … judging it all the time so that I can act appropriately to be safe”, but “not once did I feel a lesser person or was judged”, even though “a few of the health care professionals might have made a mistake and thought that we were sisters”. She drew on a metaphor of horse training to describe how she interacted with HCPs:

I used to breed horses and train and break horses, so we had this joke that I always had someone else to break in. But we do it very well. And I think it is very helpful in how they [HCPs] treat you. You know, they’re humans and they lack knowledge as well. It’s a two-way street. But I didn’t feel any homophobic times through all of [partner’s name]’s treatment, which I think is just amazing. It just goes to show how far we’ve come [Claire, Carer, 66, Lesbian, Ovarian].

However, many other LGBTQI patients and carers reported feeling “judged”, or positioned as a “weirdo” or as a “Martian” following SOGI disclosure in interactions with HCPs who were well meaning but “needed more education on inclusivity and how to discuss these topics without being offensive” [Survey, Partner, 20, Queer, Non-binary/Gender-fluid, Breast]. For example, a non-binary participant reported feeling like a “fascinating test subject” whose use was in educating HCPs, while paying for the privilege through private health care.

I find it really hard to even transfer between medical professionals because people want to hold on to me cause I’m like a valuable patient to have on their books. There was one health practitioner last year … I just felt like she was ripping me off and just finding me really fascinating, like I was like educating her and then paying for it at the same time. [Jessie, 37, Queer, Non-binary/Gender-fluid, Medical intervention, multiple cancers]

Some participants dealt with visible HCP discomfort or lack of knowledge calmly by being “personable and engaging” and assuming HCPs would accept them: “I’ve never made being gay a ‘problem’ and if there was a ‘problem’. I have always approached its resolution in a caring open way” [Survey, 67, Gay, Prostate]. Others reported feeling “a bit uncomfortable” because of the obvious “discomfort” of HCPs following disclosure, or felt it was “insulting and insensitive” to have the impact of cancer dismissed after they disclosed.

I had two people (HCPs) say, ‘it doesn’t matter, you’re a lesbian’. And I said, ‘I don’t understand what you mean, why does it not matter that I’ve got cancer because I’m a lesbian?’ And after the blushing, they go ‘well you’re not having [penetrative] sex’… There was an assumption that it’s okay to have breast cancer if you’re lesbian because a lover will understand your situation or your lack of sex drive, and it won’t matter because you’re not with a bloke. [Myra, 68, Lesbian, Breast]

Lack of HCP awareness of the intersection of cultural identity and LGBTQI identity was also commented upon. For example, a participant from a Chinese cultural background said, “few [HCPs] consider the points of differentiation for lesbians from culturally and linguistically different backgrounds” [Violet, 53, Lesbian, Uterine], and an Aboriginal man told us, “there’s a lot of complexity around the intersection of sexuality and cultural background and race, and health care settings in Australia are not geared towards acceptance around that” [Ryan, 60, Gay, Prostate]. HCP assumptions based on the cultural background of the patient were sometimes incorrect: “I’m not out to my parents and there were a lot of cultural assumptions. Being Chinese the doctors were assuming that my parents should be involved in the decision making, whether or not I wanted them to be involved” [Ash, 40, Non-binary, Bisexual, Unknown cancer].

Many LGBTQI patients and carers dealt with uncertainty about HCP responses to disclosure by choosing not to disclose their SOGI status. As one participant told us, “Doctors? They never ask; I never tell” [Survey, 69, Queer, Prostate]. Non-disclosure had both positive and negative consequences. Some participants described concealment of LGBTQI status as “easier” and “safer” because the “cost-benefit”21 analysis of coming out resulted in feelings of “trepidation”, with disclosure positioned as “too scary” and “even opening this conversation” as “often-impossible”. It was believed that “in not being out, you get treated better”, with some participants describing a sense of agency in “determin[ing] when and how others know”, thereby allowing them to avoid discrimination.

I always tick women on the forms because it’s so discriminatory if I don’t. It is just absolutely not worth it to me to identify as anything other than cis in the health system because people make a mockery of trans bodies. I ride off the privilege of my gender fluidity constantly in order to grin and bear it, deal with the cis-normativity that it takes to avoid that aspect of discrimination. [Jessie, 37, Queer, Non-binary/Gender-fluid, Medical Intervention, multiple cancers]

Ticking “woman on the forms” was not without cost, however, with Jessie saying “I had to sacrifice that part of my identity to get treatment in the health system”. This had negative implications for their health, as they had “come to points in my life where I’ve avoided help seeking or opted out of the health system just because I couldn’t be a binary person that day”.

For others, LGBTQI status was deemed “irrelevant” or “not necessary to declare” in relation to cancer care as it was “nobody’s business what I do in my private life”22. However, non-disclosure meant that cis-heteronormative assumptions remained unchallenged, which could leave individuals feeling “awkward and uncomfortable”, “silenced”, “angry”, “guilty” and “not understood”, because their LGBTQI status was erased or made invisible by HCPs.

Frustration was common when requests for LGBTQI specific information were ignored, or “general information” provided in response to requests. For example, the response to a gay man who asked for information about “what to look out for” when having sex after treatment was “a verbal off the cuff ‘practice safe sex’, in general terms” [Carter, 21, Gay, Leukemia]. The “absence of targeted information” and support to address LGBTQI patient needs reinforced feelings of invisibility as “there wasn’t anything specific to same-gender couples”23, or for “trans and non-binary bodies” available for most participants. As one carer commented, “It’s really difficult to find support [online or face-to-face groups] that include lesbian women. My partner had a gynecological cancer, so all the supports were aimed at male partners” [Survey, Partner, 54, Lesbian, Ovarian]. Another said, “there are resources for carers and resources for individuals with cancer, what is lacking are services who understand the complexities when you add LGBTQI+ into the mix” [Survey, Parent, 40, Queer, Non-binary/Gender-fluid, Colorectal]. This led to many patients and carers feeling “despondent” and “isolated by mainstream cancer supports”.

HCPs who adopted a position of anti-inclusive practice demonstrated negative attitudes or outright hostility toward LGBTQI patients. This was evident in the accounts of a small minority of HCP participants who complained that the “abnormal behaviour” of LGBTQI people was being “forced” onto them and that they “just don’t need to hear about their (patients) sexual orientation if it has nothing to do with treating their condition” [Survey, Nurse, 61, Straight].

I don’t see why everyone has to force their sexual orientation on others. Heterosexual people don’t go around talking about their sexual orientation. I am now forced into hearing about and watching abnormal behavior on TV and more advertisement of non-heterosexuals. [Survey, Nurse, 61, Straight].

More commonly, the anti-inclusive practices of colleagues were observed by other HCP participants. This included accounts of HCPs who were righteous in their exclusion of LGBTQI patients, feeling “entitled” to their beliefs “that homosexuality is wrong”24. HCPs were observed to behave in “insulting”, “disgusting” and “unnecessary” ways that “show lack of understanding and lack of respect” for LGBTQI patients. This was particularly acute in relation to trans patients. For example, HCPs described observing “misgendering practices” by “a few of the doctors and some nurses” in an outpatients clinic; or HCPs “intentionally using the wrong pronouns and saying derogatory things” [Amelia, Nurse, 35, Straight] about a trans patient who was attending for an appointment; and behavior described as “an aggressive act” and “micro-aggressions” [Amy, Nurse, 55, Lesbian]. HCPs also reported anti-inclusive practices in the form of “insidious and subtle”25 micro-aggressions. This included colleagues “tutt[ing] under their breath” at “the badges around the place saying trans ally”, or providing “lip service” to LGBTQI inclusion, while concealing their “implicit biases” because they were “too clever to be openly discriminate” [Jodi, Allied, 39, Lesbian].

Some HCPs acknowledged that the anti-inclusive practices they observed had material consequences, with cis-heteronormative assumptions about patients resulting in “important pieces of information … missing from that interaction”, which meant that “the patient might not feel safe to ask the questions, clarify or seek support” [Tammy, Nurse, 48, Straight]. One HCP observed the withholding of fertility preservation advice for a man because he was gay:

The consultant looked at me and said, ‘oh, I don’t think that’ll be an issue’. I knew that the consultant was assuming he was gay, but then taking that next step and assuming that he wouldn’t be having children. To me, that wasn’t an appropriate assumption to make [Ayomi, Med, 35, Straight].

It was acknowledged that anti-inclusive comments between colleagues could be damaging because “even if the patient didn’t hear, it’s still encouraging that sort of culture in the workplace” [Amelia, Nurse, 35, Straight].

Many of the HCPs recognized that challenging anti-inclusive practice observed in colleagues was important. HCPs who it was assumed were “well-meaning” and “don’t come from a bad place” were seen to “need a bit of a fact check” about comments that were “really just not appropriate” or “careless”. However, trying to “educate” colleagues “who are prejudiced to LGBTQI patients” and are coming “from a place of harm” [Alia, Allied, 31, Straight] was reported to be more difficult, as negative attitudes and “discrimination” toward LGBTQI people was often “ingrained”. HCPs explained that they “could spend three minutes or three hours here and your mind might never be changed” [Jessica, Nurse, 38, Straight], as “there’s a lot of bigots out there and there’s a lot of bias still in health” [Kelly, Nurse, 68, Straight]. Others explained that prejudicial behaviour on the part of their colleagues that “could go to disciplinary action” was not pursued, in part due to lack of confidence that “upper management would have really recognized the importance” [Amy, Nurse, 55, Lesbian].

The impact of anti-inclusive practice on LGBTQI patients and their carers was universally described as negative and damaging. A substantial number of patients and carers concurred, “not everyone in the medical team was accepting or supportive”, providing examples including doctors, nurses and allied health professionals. LGBTQI patients and their carers described having to navigate the “constant”, “covert” and “daily discrimination” in cancer care. Believed to be “everywhere”, anti-inclusive HCPs were described as “positively hostile”, “dismissive”, “paternalistic and judgmental” of LGBTQI patients. This resulted in the feeling of “being treated like a lesser person”26 because it can “gradually chip away at your confidence and sense of self-worth”27. It was “stressful” to sense a negative “vibe” from an anti-inclusive HCP, suggesting that they “don’t want you here”, leading to feelings of “distrust” towards HCPs.

2011_may_w_g2.ddsIn health, where you are just naked all the time … everything that is intimate and important to me has been clinically invaded by people who don’t respect me for who I am. So those people are everywhere. That systemic discrimination makes me distrust people in the system who do really good work and do really care [Jessie, 37, Queer, Non-binary/Gender-fluid, Medical Intervention].

Some anti-inclusive HCPs were reported to change from being “warm and helpful” to “cold” and “shorter in their responses”, or to have “stopped speaking to me” when patients disclosed their sexual orientation, intersex variation, or trans status:

Two of my specialists stopped speaking to me after my sharing about being intersex. It’s clear there is a great deal of stigma surrounding it [Terry, 40, Queer, Non-Binary, Intersex, Medical Intervention]

Due to my gender presentation, I often felt mainstream services did not willingly engage with me or provide me with the support I needed [Survey, Parent, 40, Queer, Non-binary/Gender-fluid, Colorectal]

I’ve had some that I’ve said I’m gay and they’ve just sort of shut down after” [Aaron, 32, Gay, Bowel].

Some HCPs were overtly exclusionary, stating to patients that they don’t agree with “that sort of thing’”, or that the patient was not “living according to God’s will” because of being gay. One HCP reportedly “dropped her hand and said ‘not in this hospital’ and left” [Myra, 61, Lesbian, Breast] when she realized she was discussing assisted reproduction with a lesbian woman. Patients also told us that their HCP ignored their disclosures of identity, for a participant said; “I had told him that I was a gay woman. He still asked to talk to my husband” leaving her feeling as though “he didn’t see me”, “didn’t hear me”, “didn’t understand who I was” [Barbara, 48, Lesbian, Uterine]. Trans and non-binary patients explained that it could be “difficult” to get HCPs to “use gender-neutral language”, including one young person who “had to beg” their oncologist “to stop mis-gendering me”. These responses to disclosure reinforced “distrust” and a distinct lack of safety. As one participant told us:

I don’t feel safe. I have to think ALL THE TIME in medical situations if it’s safe to come out. Correcting, educating, making formal complaints – I am enraged that my energy has been taken up by this my whole life when I’m in pain; very sick; recovering; scared. [Survey, 39, Queer femme, Medical Intervention].

Offensive comments or actions by HCPs could also be a source of distress for LGBTQI patients. For example, one lesbian participant reported, “a doctor told me I shouldn’t have an issue with her putting her fingers inside of me ‘to test’ something … because ‘people like you like this kind of thing’” [Survey, 40, Lesbian, Cervical]. A bisexual woman who disclosed to her doctor that her fiancé was a woman was asked “do you consider yourself to be a man?”, leading to the reflection “that was another situation where I become the educator instead of being a patient” [Catherine, 61, Bisexual, Vulval]. Anti-inclusive practices were experienced as more all-pervasive for some patients living in regional and rural locations, because HCPs can “get away with having biases and being discriminatory when there are limited options for the patients” [Survey, 63, Straight, Breast]. As a trans participant told us, “If you live in one of the small towns, you don’t get to choose who your GP is. They might be very transphobic and you’re stuck with them” [Victor, 47, Straight, Trans Man, Ovarian].

Many partners and other carers reported being impacted upon by anti-inclusive practices, feeling that HCPs were “reluctant” to engage with them, or treated them as “lesser than” because they were not “a heterosexual white individual”28. Partners reported, “you just get that look or that raised eyebrow, or you don’t get referred to properly”29, with HCPs “insisting on referring to me as his friend” despite “being told we were married”. Another HCP “questioned” whether the patient had “other family”, as though they were “looking for more legitimate people to engage with”30. Patients also spoke of partner exclusion:

My radiation oncologist clearly thought my life was absolutely disgusting, refused to acknowledge my partner. If she was in an appointment with me, he’d just completely ignore her. I had ticked the de facto box and he actually scribbled out my tick on that box and put single [Catherine, 41, Lesbian, Vulval].

Another patient told us that it was “difficult for my partner to get any answers and yet when my parents turned up they were more than happy to talk to them” [Survey, 42, Lesbian, Uterine]. Administrative staff, who selectively applied hospital policies, also perpetrated “woeful” exclusionary practices. For example, a lesbian lung cancer patient’s wife and partner of 25 years was required “to stay outside” on the basis that she “wasn’t family yet”, an incident that happened just before marriage equality was legalized in Australia. Hostilities were also extended to chosen family, such as “lesbian friends” who would “come and visit” such as being treated “quite offhandedly”, “eye rolling” and with lack of “respect” [Elsie, 55, Lesbian, Lung]. Intentional refusal to recognize LGBTQI partners had “horrible” consequences for one gay man who, despite having “power of attorney and enduring guardianship” for his partner, found that “the doctor in charge wouldn’t let me see my partner when he was dying because we’re gay”. He concluded “I think the doctor just did not like gay people”, evidenced by broader homophobic assumptions on display:

I felt my partner wasn’t treated with dignity and respect. And I wasn’t treated with any dignity or respect when my partner was dying. They were quite rough, without even warning me. Like he’s from out of space or like he’s got AIDS. Taking it for granted because he’s gay then he’s got AIDS [Neal, 68, Gay, Prostate].

Numerous LGBTQI patients reported instances wherein they perceived their medical care to be inadequate, or feared being denied health care services because they were LGBTQI, with direct implications or their willingness to engage in cancer healthcare. As one young lymphoma patient told us, “what if people don’t want to treat me because they don’t want me to live because I’m gay” [Oscar, 27, Gay, Lymphoma]. Issues included, “difficulty engaging” HCPs “because of my presentation as non-binary/trans”31; being misdiagnosed due to beliefs that “gay people are overdramatic or hypochondriacs”32; “fertility issues” not being discussed “as part of cancer care because I’m gay”; and being denied “pain relief” after an operation “because the nurse doesn’t like trans people”33.

When we go into a random appointment, we might be looking at someone who actually wants us dead. That is how hard it is to get medical care. You’ve randomly got to work out a way to protect yourself against someone who really doesn’t know where the problem is and hates your guts [Scott, 55, Gay, Trans man, Multiple].

Patients also reported the distress they experienced following encounters with HCPs who deliberately enforced cis-heteronormative ideals through their clinical decision-making. For example, one HCP was reportedly “focused entirely” on maintaining a lesbian patient’s vagina with dilators post-surgery “so that a man could put his penis in it” if she decided to be in “a proper relationship one day”. This was despite the patient telling him “that was not an issue, he [HCP] would just ignore me, just talk over the top of me” [Catherine, 61, Bisexual, Vulval]. A number of participants reported feeling judged in their choices in relation to reconstruction following breast surgery. A non-binary participant said that they “had to fight really hard to not have a reconstruction after a mastectomy”, and another patient said that there was a “lack of understanding” of LGBTQI patients’ “desire to go flat” [Jasper, 50, Queer, Breast]. A carer told us:

My partners’ surgeon made her feel like a weirdo for the plastic surgery options she requested and didn’t really know how to be neutral on the topic of gender nonconformity and transgender identities with her other patients. She needed more education around how to discuss these topics without being offensive and making us feel like total oddballs for who we are [Survey, Partner, 33, Queer, Breast].

LGBTQI patients and their carers reported detrimental impacts of anti-inclusive and exclusionary care, including feeling as though it “prevents me from help-seeking for my current maintenance care” [Patricia, 65, Lesbian, Uterine]. Although many patients positioned themselves as “assertive” in their lives generally, in the context of cancer care they reported feeling “at the mercy” of their HCPs [Hannah, Partner, 45, Lesbian, Uterine]. A number of patients reported feeling that “you can’t really complain” and that “not seeing that person again” was “not a choice that you get”, as anti-inclusive HCPs may be “the only thing standing between you and death at that point in time. You don’t have the luxury of just walking out” [Catherine, 61, Bisexual, Vulval].

The aim of the present study was to examine the construction and experience of LGBTQI cancer care from the perspective of HCPs, LGBTQI patients and their caregivers. We identified three subject positions adopted by HCPs in relation to the provision of care to LGBTQI people: inclusive and reflective practitioner, egalitarian practitioner, and anti-inclusive practitioner, which had implications for LGBTQI cancer patients and their partners, and other chosen family caregivers.

HCPs who took up the subject position of inclusive and reflective practitioner demonstrated LGBTQI cultural competence and cultural humility, creating a place of cultural safety (33–35) for LGBTQI patients and their carers, through a range of inclusive verbal and non-verbal strategies (1, 14, 45). Inclusive and reflective HCPs regarded LGBTQI patients as potentially vulnerable and needing nuanced care, following best practice models of person-centered care tailored to individual patient needs (66). They recognized the impact of societal discrimination and the legacy of trauma in health care, including difficulties related to disclosure of SOGI status (67) and violations to bodily autonomy for some intersex patients (68), drawing on an affirmative construction of LGBTQI health (69). Inclusive and reflective HCPs acknowledged the need for sensitivity and acceptance of SOGI status in interactions with LGBTQI patients, and the intersection of identities in LGBTQI patient outcomes, including sexuality, gender, age and cultural background, which can lead to discrimination across “multiple axes of oppression” (20). Inclusive HCP practice involved non-judgmental respectful treatment and welcoming and open dialogue, accompanied by reflective awareness of gaps in their own personal knowledge and skills (1, 14, 45). The importance of knowing patients’ SOGI status information was acknowledged (14, 28), and the assumption that all patients are heterosexual and cisgender was avoided, by HCPs taking responsibility to facilitate disclosure of patient SOGI status, and including partners and other chosen family in consultations and care. Inclusive and reflective HCPs recognized the importance of the relationship between clinicians and LGBTQI patients in the provision of affirmative health care (31).