- 1Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Gastroenterology, Department of Gastroenterology, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Pazhou Lab, Guangzhou, China

Despite emerging publications have elucidated a functional association between RCN3 and tumors, no evidence about a pan-cancer analysis of RCN3 is available. Our study first conducted a comprehensive assessment of its expression profiles, prognosis value, immune infiltration, and relevant cellular pathways via bioinformatics techniques based on the public database of TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas). RCN3 is highly expressed in most tumors, and it is associated with poor prognosis. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox regression analysis suggested that the high expression of RCN3 was associated with poor overall survival (OS) in pan-cancer, Cox regression analysis also indicated high RCN3 expression was correlated with disease-specific survival (DSS) and progression-free interval (PFI) in most tumors. We observed a regulation function of RCN3 at genetic and epigenetic levels through CNA and DNA methylation using cBioPortal database. Based on Gene Set Enrichment Analysis, we first identified related pathways of RCN3 and its potential biological functions in pan-cancer, RCN3 was implicated in oncogenic pathways, and was related to extracellular matrix and immune regulation. We found that RCN3 positively correlated with the levels of infiltrating cells such as TAMs and CAFs, but negatively correlated with CD8+ T-cells by analyzing immune cell infiltration data we downloaded from published work and online databases, further investigation of the correlation between immunosuppressive genes, chemokines, chemokines receptors, and high RCN3 expression showed a significant positive association in the vast majority of TCGA cancer types. These results indicated its role as an immune regulatory in cancers and suggested that RCN3 is a potential biomarker for immunotherapy. Also, we found that expression of RCN3 was much higher in CRC tissues than in normal tissues with a higher expression level of RCN3 closely correlating to advanced American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage, poor differentiation, increased tumor size, and poor prognosis of CRC. Biological function experiments showed that RCN3 regulated CRC cells’ proliferation and metastasis ability. Upregulation of RCN3 in CRC cells increased the expression of immune related factor, including TGFβ1, IL-10, and IL-6. Thus, our pan-cancer analysis offers a deep understanding of potential oncogenic roles of RCN3 in different cancers.

Introduction

Cancer is a major public health problem (1). Tumor microenvironment (TME) and tumor-infiltrating immune cells have been reported to be closely associated with cancer initiation, progression, and metastasis. Immunosuppression is one of the notable characteristics of TME (2–5). Although breakthroughs have been made in tumor immunotherapy, which holds promise for the clinical cure of patients with malignant tumors, immunotherapy is still not applicable to all patients (6–9). Therefore, finding novel therapeutic biomarkers and strategies is of seminal importance.

Reticulocalbin 3 (RCN3) is a member of the CREC (Cab45/reticulocalbin/ERC45/calumenin) family of multiple EF-hand Ca2+-binding proteins (10, 11). Previous studies suggested that RCN3 functions as an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen protein in the secretory pathway (12, 13). Many studies have revealed that RCN3 participates in biological processes such as apoptosis, ER stress, and collagen fibrillogenesis in tissues producing an extracellular matrix (14–16). In addition, limited studies reported that RCN3 also plays a role in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), melanoma, osteosarcomas, gliomas, and colorectal cancer (17–21). Non-tumor cells like fibroblasts, immune cells in the TME, participate in the tumor biology process through complex interactions with cancer cells (22), previous research has found that fibroblasts with somatic copy number alterations may interact with cancer cells to play synergetic roles in tumor development, and according to the published single-cell multiomics sequencing results, RCN3 is identified as a fibroblast-specific biomarker of poorer prognosis of colorectal cancer (CRC) (21).These results indicated that RCN3 may act as an essential regulator in tumor progression and immunomodulation. However, there is no evidence focused on the association between RCN3 and other tumors, and RCN3 expression in pan-cancer remains unclear.

Our study, for the first time, comprehensively assessed the role of RCN3 in TCGA pan-cancer. We conducted a pan-cancer analysis to explore RCN3 expression signature, genetic alteration characteristics, DNA methylation, prognostic value, and immune regulation relevant pathways. We further investigated the correlation between RCN3 expression with tumor-infiltrating immune cells and immunosuppression-related genes in pan-cancer samples. Our research highlighted the significance of RCN3 in pan-cancer and its potential oncogenic role in influencing immune infiltration and tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment.

Materials and Methods

RCN3 Gene Expression Analysis

RCN3 gene expression data in pan-cancer were obtained from the Tumor Immune Estimation Resource, version 2 (TIMER2) database (http://timer.comp-genomics.org/) (23). We utilized the “ggradar” R package to obtain data on RCN3 expression in 33 TCGA cancer tumors. We downloaded the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) data from UCSC XENA web server (https://xenabrowser.net/) to obtain data on RCN3 gene expression in 31 normal tissues. Furthermore, we applied the “ggpubr” R package to obtain box plots of the RCN3 expression difference between tumor tissues and matched normal tissues of the TCGA project (Supplemental Table S2). Box plots of the RCN3 expression difference in different cancer pathological stages were built based on the “ggplot” R package, which analyzed different clinical stages (stage I, stage II, stage III, and stage IV) of TCGA tumors. Additionally, we employed the UALCAN portal (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html), a website for analyzing cancer omics data including protein expression analysis (24) to profile the expression of the RCN3 total protein between normal samples and tumor samples of breast cancer, colon cancer, ovarian cancer, clear cell RCC (renal cell carcinoma) and UCEC (uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma). TCGA data for pan-cancer analysis of RCN3 were all derived from the UCSC XENA web server.

Genetic Alteration Analysis

The cBioPortal web (https://www.cbioportal.org/) (25, 26), provided us information about genetic alteration characteristics of RCN3. We investigated the alteration frequency, mutation type, and CNA (copy number alteration) of RCN3 in different TCGA tumors. We also used the cBioPortal web to obtain the data on DNA methylation levels of the RCN3 in various cancers.

Survival Prognosis Analysis

The relationship between the expression levels of RCN3 and patients’ overall survival across different types of cancer was evaluated by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. The noteworthy results were visualized as survival curves built using “survminer” and “survival” R packages. The median cutoff values were used as the expression thresholds for dividing the high and low expression groups. Moreover, we also analyzed patients’ prognosis, including OS (overall survival), DFI (disease-free interval), PFI (progression-free interval), and DSS (disease-specific survival) in 33, 28, 32, and 32 TCGA cancer cases, respectively, via univariate Cox proportional-hazards regression analysis. The noteworthy results shown as forest plots were visualized with “survminer” and “survival” R packages. A log-rank P value < 0.05 was considered significant for survival-relevant analysis.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) is a commonly used bioinformatics method that conducts genomes enrichment analyses and searches functional terms and pathways (27). In the present study, we employed GSEA to further explore the potential functions of RCN3 in different cancers. “clusterprofiler” R package was used to perform GO (Gene Ontology) and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) enrichment analysis. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The top 20 categories of each cancer are displayed.

Immune Infiltration Analysis

TIMER2 web server is a commonly used web resource for analyzing tumor-infiltrating immune cells in various cancers (23). We evaluated the association between RCN3 expression levels and immune infiltrates across TCGA tumors, including cancer-associated fibroblasts, immune cells of CD8+ T-cells, and tumor-associated macrophages. The TIMER, EPIC, XCELL, MCPCOUNTER, TIDE, CIBERSORT, CIBERSORT-ABS, and QUANTISEQ algorithms were applied for the estimations. The data were displayed as a heat map and P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. We then downloaded the TCGA expression data samples from previous studies (28). The CIBERSORT tool (29) was used to assess the correlation between the RCN3 expression levels and macrophages levels. The scatterplot data presented the P-values and correlation coefficient. Furthermore, a heat map, which contains correlation coefficient and P-value via Pearson’s correlation test, was applied to construct correlation analysis between RCN3 with tumor immunosuppression-related genes, chemokines, and chemokines receptors.

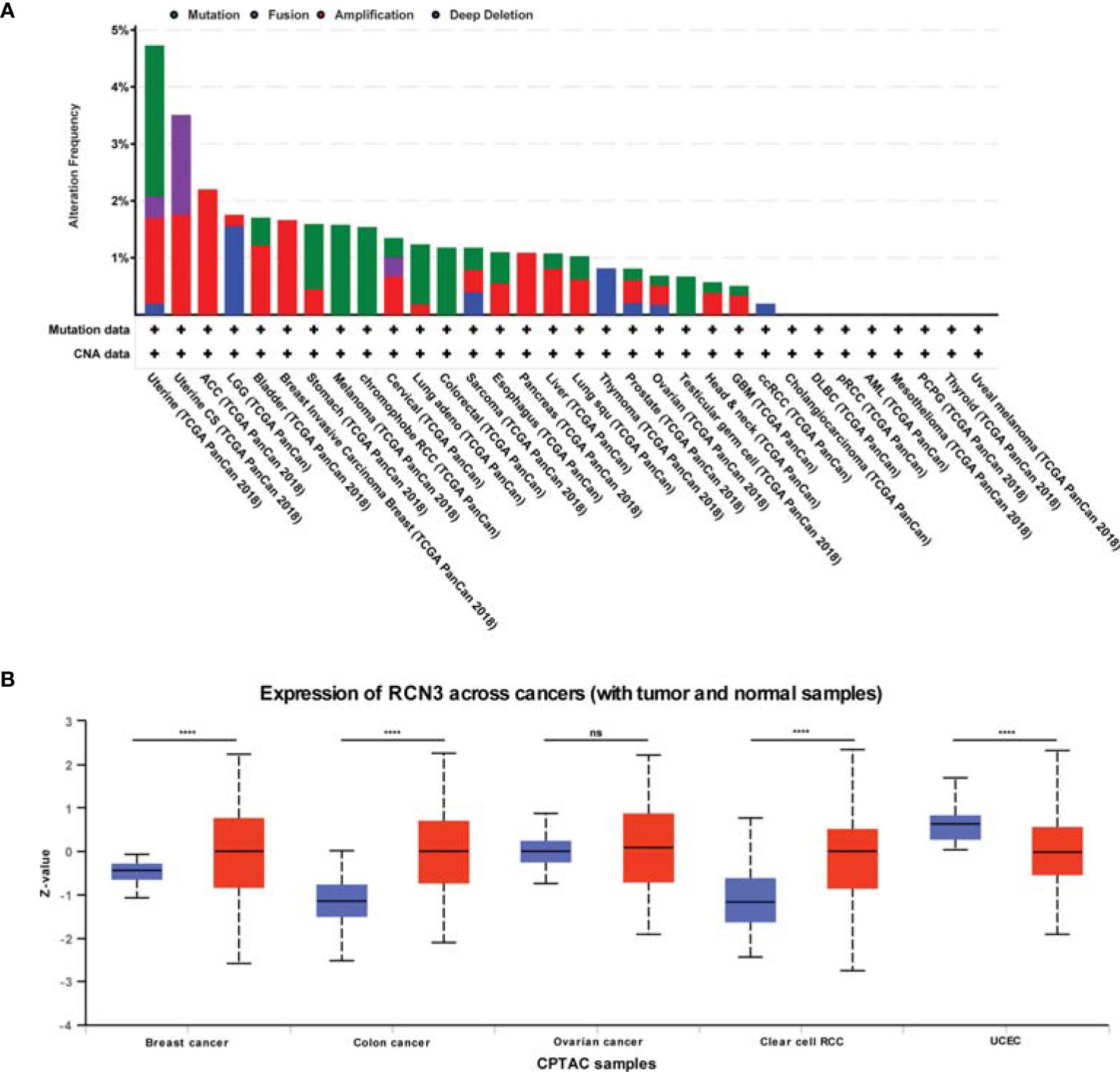

Tissue Microarray and Immunohistochemistry

The TMA containing a total of 89 colon cancer patients, together with the data of pathological staging in accordance with TNM classification of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC, 2010) and overall survival time for all cases (Supplemental Table S1) was obtained from the National Engineering Center for Biochip at Shanghai. The IHC staining of RCN3 with scoring was done as below. The section of TMA was baked at 65°C for 30 min. Then the section was deparaffinized with xylenes and rehydrated. After treatment with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol to quench the endogenous peroxidase activity, the section was submerged into citrate buffer and high-pressure boiled for antigenic retrieval, followed by incubation with 1% bovine serum albumin to block the nonspecific binding. Rabbit anti-RCN3 (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was incubated with the section overnight at 4°C. After washing, the TMA section were treated with anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Zhongshan Biotech, Beijing, China). The tissue section was incubated with 3,3-diaminobenzidin (DAB) and counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. The section was reviewed and scored independently by two observers, based on both the proportion of positively stained tumor cells and the intensity of staining. The proportion of positive tumor cells was scored as follows: 0 (no positive tumor cells), 1 (<10% positive tumor cells), 2 (10–50% positive tumor cells), and 3 (>50% positive tumor cells). The intensity of staining was graded according to the following criteria: 0 (no staining); 1 (weak staining = light yellow), 2 (moderate staining = yellow brown), and 3 (strong staining = brown). The staining index (SI) was calculated as staining intensity score x proportion of positive tumor cells. Using this method of assessment, the expression of RCN3 was scored as 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 9. Cutoff values for RCN3 were chosen based on a measure of heterogeneity by the log-rank test statistical analysis regarding overall survival. An optimal cutoff value was identified: the score of ≥4 was used to define tumors as high RCN3 expression and ≤3 as low expression of RCN3.

In Vitro Cellular Experiment

Human colorectal cancer cell line HCT116 was cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C in 5% CO2. In vitro cellular experiment was shown as follows:

Cell proliferation assay: The stable cell lines were seeded on 96-well plates at an initial density of (1-2×103/well). At each time point, cells were detected by the Cell Counting Kit-8 kit following the kit assay protocol.

Colony formation assays: Cells were seeded on a 6-well plate (200 cells/well) and incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere incubator. After 2 weeks, cells were fixed and stained with hematoxylin. Colonies containing more than 50 cells were counted. Three independent experiments were performed for each cell line.

Cell invasion assays: For invasion assays, the membrane was covered with 40 μl of the BD Matrigel (diluted 1:8 with serum-free medium) in advance. The stable cells (1–1.5 × 105) were seeded into the transwell chambers with serum-free medium while the lower chamber was covered with 500 μl medium supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum. After 48 h incubation at 37°C, cells were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and then stained with 0.5% crystal violet diluted in methanol for 25 min. The membrane was removed and mounted onto glass slides and counted (5 × 200 random fields per membrane). Three independent experiments were performed, and the data are presented as mean ± S.D.

Results

RCN3 Expression Levels in Human Cancers

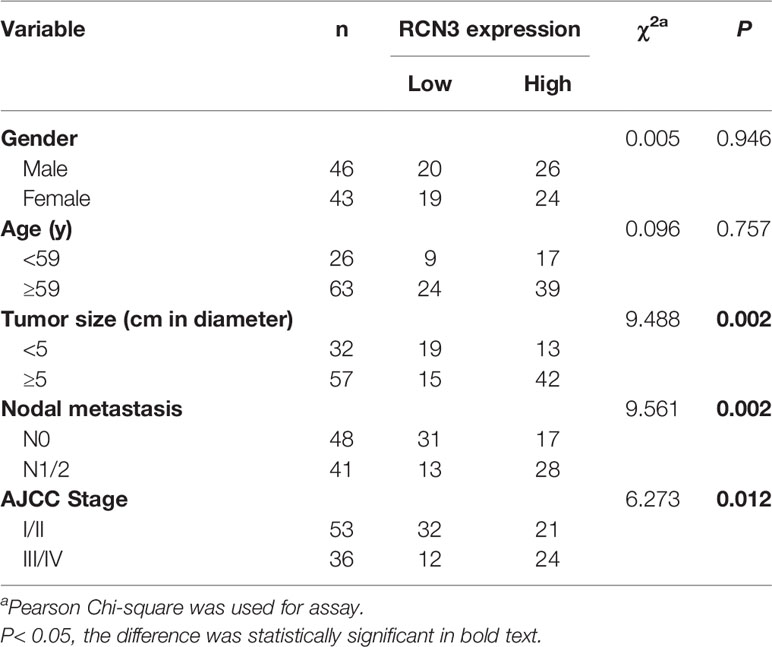

We first analyzed the expression characteristics of RCN3 in tumor and normal tissues from TCGA via TIMER2 database. As shown in Figure 1A, up-expression of RCN3 was observed in most cancer types, such as LUSC (lung squamous cell carcinoma), LUAD (lung adenocarcinoma), LIHC (liver hepatocellular carcinoma), KIRC (kidney renal clear cell carcinoma), HNSC (head and neck squamous cell carcinoma), ESCA (esophageal carcinoma), COAD (colon adenocarcinoma), CHOL (cholangiocarcinoma), BRAC (breast invasive carcinoma), and GBM (glioblastoma multiforme). In contrast, the expression of RCN3 was below that in normal control tissues in KICH (kidney chromophobe) and CESC (cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma). Furthermore, we evaluated the expression levels of RCN3 in different tumor tissues and matched normal tissues using the ggpubr package. RCN3 was found to be overexpressed in BRCA, CHOL, COAD, ESCA, HNSC, KIRC, LUAD, LUSC, and STAD (stomach adenocarcinoma) but was underexpressed in KICH (Supplementary Figures 1A–J). Meanwhile, the expression of RCN3 was analyzed using the data of multiple types of cancers downloaded from TCGA (Figure 1B). Next, we analyzed RCN3 expression in the 31 types of normal tissues through the GTEx dataset, which revealed RCN3 was generally expressed in various tissues (Figure 1C). Collectively, these results indicated that RCN3 has an elevated expression in most cancers.

Figure 1 RCN3 expression levels in different human cancers. (A) The expression level of RCN3 in different tumor tissues and normal tissues was analyzed through TIMER2 database (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001). The radar charts (ggradar package was used for analysis) showing the expression of RCN3 in different cancers from TCGA (B) and in normal tissues of the GTEx (C). Mean expression was the basis of ranking.

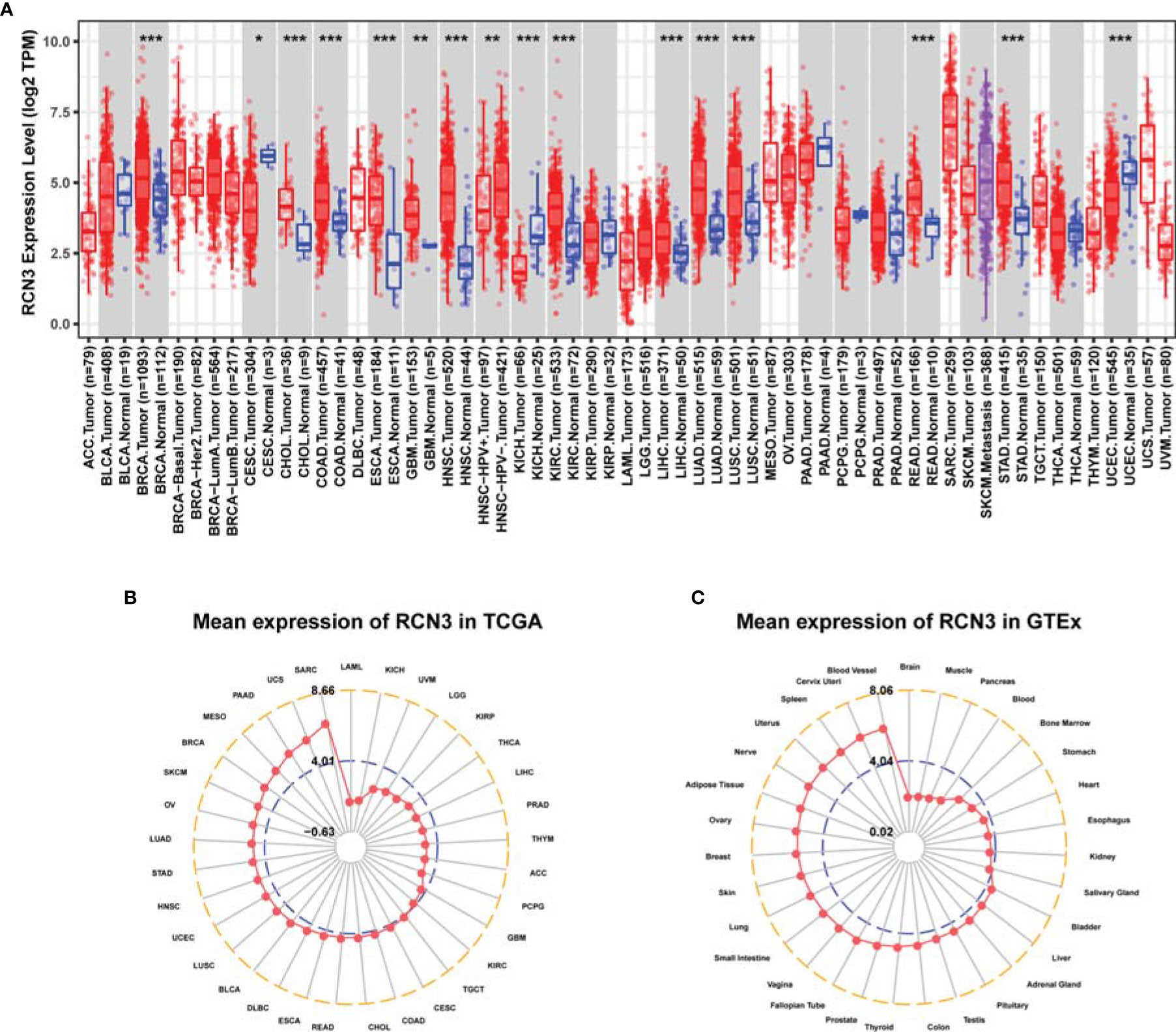

We then explored mRNA expression patterns of RCN3 in different clinical stages. As shown in Figures 2A–I, RCN3 expression varied significantly in different pathological stages of cancers, including ACC (adrenocortical carcinoma), BLCA (bladder urothelial carcinoma), BRCA, COAD, ESCA, HNSC, READ (rectum adenocarcinoma), SKCM (skin cutaneous melanoma), and THCA (thyroid carcinoma).

Figure 2 Correlation between RCN3 expression and pathological stages of cancers in TCGA. (A–I) Box plot showing the relationship of different tumor stages with RCN3 expression in different cancers from TCGA. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001; ns, no significance.

These findings suggest that RCN3 expression levels were higher in higher clinical stages.

CNA and DNA Methylation Alternations of RCN3 in Different Cancers

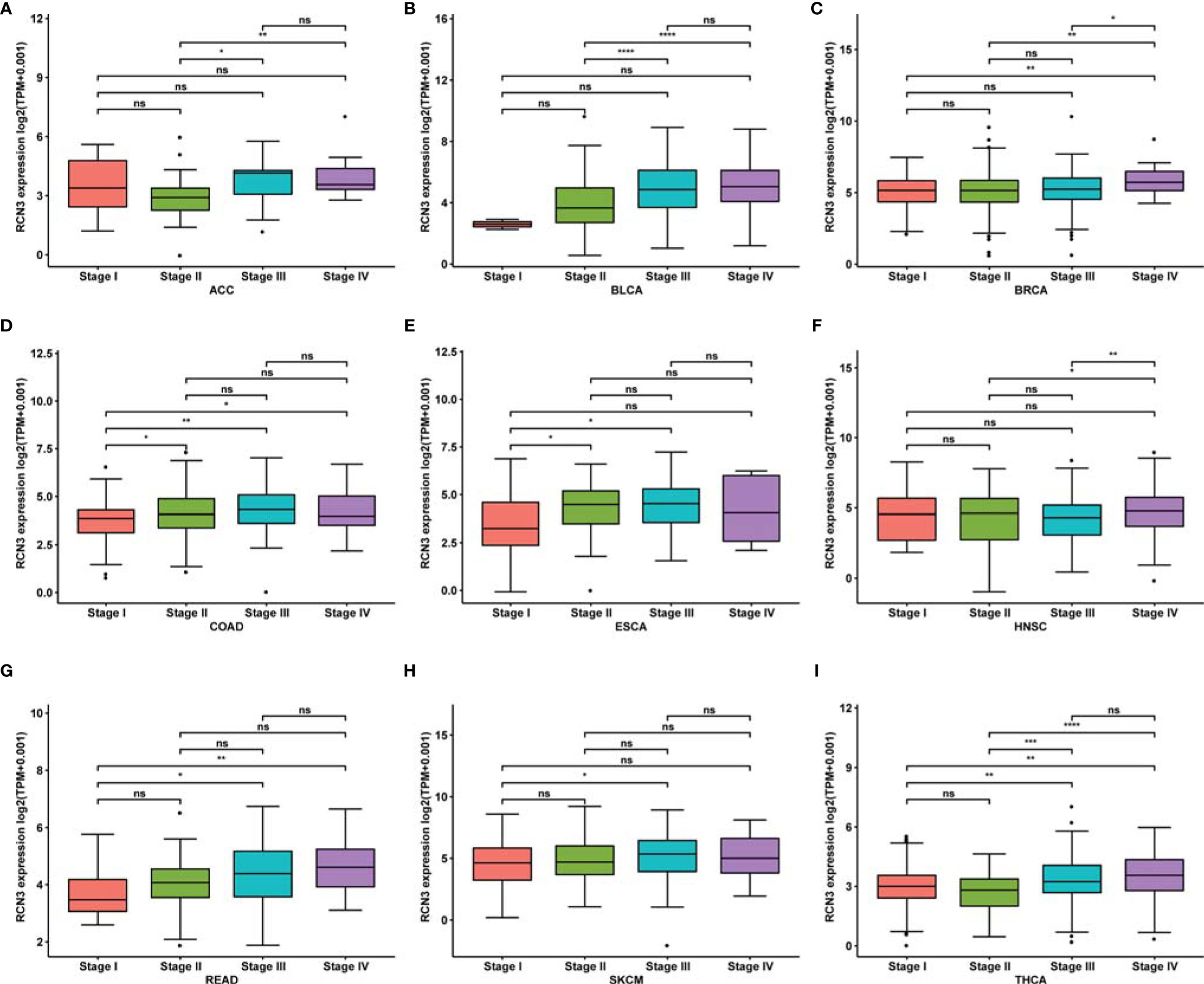

We observed the genetic alteration status of RCN3 using cBioPortal. The highest alteration frequency of RCN3 (>4%) appears for patients with uterine cancers, in which “mutation” is the primary genetic alteration type (Figure 3A). It is worth nothing that all ACC, breast invasive cases, and pancreas tumor cases with gene alteration (>2%, >1%, >1% frequency, respectively) had copy number amplification of RCN3 (Figure 3A). We applied the cBioportal data bank to analyze the relationship between RCN3 expression and relative linear copy-number values. As shown in Supplementary Figure 3, a significant positive correlation was found between RCN3 expression and CNA in READ, SARC (sarcoma), UCEC (uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma), UCS (uterine carcinosarcoma), UVM (uveal melanoma), GBM, LGG (brain lower grade glioma), MESO (mesothelioma), and OV (ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma). After exploring gene expression variation contributed by CNA, we then investigated whether expression of RCN3 was regulated by epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation. We used the cBioportal data bank to explore the correlations between RCN3 expression and promoter DNA methylation levels, the results revealed a significant negative correlation between RCN3 expression and DNA methylation in BLCA, BRCA, CESC, CHOL, LIHC, ESCA, HNSC, KIRC, LIHC, LUAD, LUSC, ESO, PAAD (pancreatic adenocarcinoma), PRAD (prostate adenocarcinoma), READ, SARC, SKCM, STAD, UCEC and UCS (Supplementary Figure 2). Therefore, both genetic alterations and lower DNA methylation levels are likely the contributed factors for the abnormal elevate of RCN3 in most cancers.

Figure 3 CNA and total protein expression levels of RCN3 in human cancers. (A) CNA and mutation frequency data of RCN3 for the TCGA tumors were accessed using the cBioPortal tool. (B) The expression of the RCN3 total protein between normal samples and tumor samples of breast cancer, colon cancer, ovarian cancer, clear cell RCC, and UCEC were determined by UALCAN. ****p < 0.0001; ns, no significance.

We also used the UALCAN tool to determine the expression of the RCN3 total protein between different tumors and normal samples. The results showed higher expression of RCN3 total protein in tumor samples of colon cancer, breast cancer, and clear cell RCC than in normal samples but the opposite result was obtained in UCEC (Figure 3B).

Prognostic Significance of RCN3 Expression in Pan-Cancer

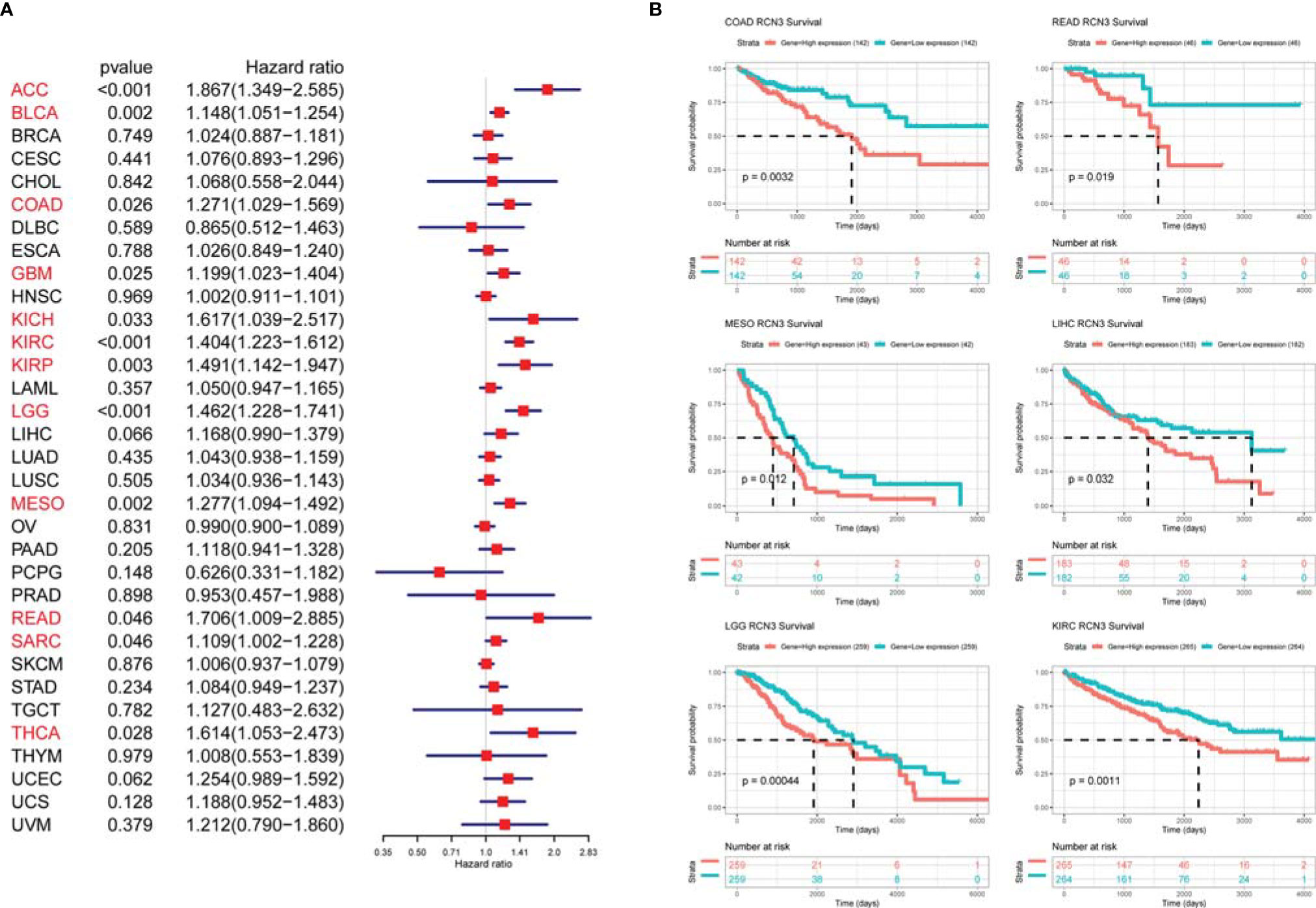

We applied univariate Cox proportional-hazards regression analysis to quantify the relationship between RCN3 expression and overall survival in various cancers. High RCN3 expression was associated with bad prognosis in ACC, BLCA, COAD, GBM, KICH, KIRC, KIRP, LGG, MESO, READ, SARC, and THCA (OS: HR>1, p-value<0.05, Figure 4A). Also, the Kaplan-Meier analysis results indicated that higher expression of RCN3 was related to poor prognosis of OS in COAD, READ, MESO, LIHC, LGG, and KIRC (Figure 4B). Furthermore, our results showed that high RCN3 expression indicated poor DFI in ACC, BRCA, and KIRP (Supplementary Figure 4A); poor PFI in ACC, BLCA, BRCA, KICH, KIRC, KIRP, LGG, MESO, and PRAD (Supplementary Figure 4B); and poor DSS in ACC, BLCA, BRCA, COAD, GBM, KICH, KIRC, KIRP, LGG, and MESO (Supplementary Figure 4C). Also, we found that high expression of RCN3 shared a higher nodal metastasis stage in ACC, COAD, BRCA, and READ (Supplementary Figures 5A–D). A GSVA analysis of 32 cancer types showed that expression of RCN3 significantly correlated with the pathway of epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Supplementary Figure 5E). These findings suggest that high RCN3 expression was generally associated with poor outcomes in pan-cancer analysis.

Figure 4 Relationship of RCN3 expression with survival prognosis in pan-cancer. (A) Univariate Cox proportional-hazards regression used to quantify the relationship of RCN3 with overall survival. High RCN3 expression correlated with bad prognosis in ACC, BLCA, COAD, GBM, KICH, KIRC, KIRP, LGG, MESO, READ, SARC, and THCA (HR>1, p-value<0.05). (B) Kaplan-Meier curves showing higher expression of RCN3 was related to poor prognosis of OS in 6 cancer types. The survival curves with logrank p<0.05 are given.

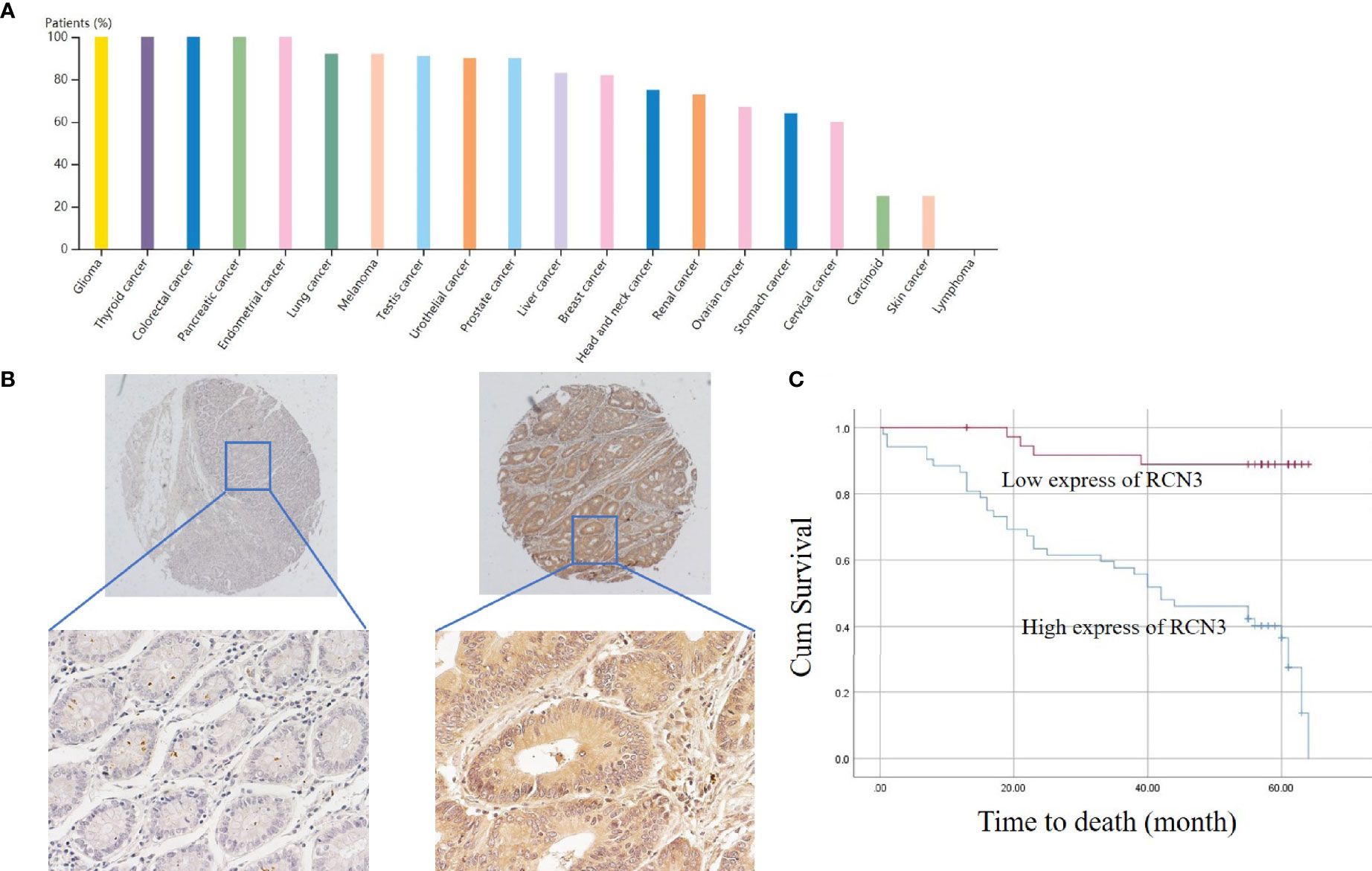

Furthermore, the protein expression level of RCN3 was shown by the human protein atlas, in which we found that the protein level of RCN3 was significantly expressed in most types of cancer, with glioma, thyroid cancer, and colorectal cancer ranked in the top 3 (Figure 5A). To further identify the prognostic significance of RCN3, a TMA of colorectal cancer was carried out. As a result, RCN3 protein was detected in 84 of 89 (94.4%) cases of CRC samples with 52 (61.9%) cases displaying high expression (Table 1 and Figure 5B). Besides, Pearson chi-square tests revealed that the expression of RCN3 was significantly correlated with AJCC (P=0.012) tumor size (P=0.002) and nodal metastasis (P=0.002) (Table 1). Notably, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed that patients with high RCN3 expression had poorer overall survival than patients with low RCN3 expression (39.7 vs. 59.7 months, P=0.000) (Figure 5C). These findings strongly suggest that RCN3 may serve as a potential oncogenic role in CRC.

Figure 5 Protein expression of RCN3 in pan-cancer and its prognosis role in CRC. (A) Protein expression of RCN3 in pan-cancer was shown by the human protein atlas. (B) The protein level of RCN3 was found highly expressed in the TMA containing 89 colon cancer cases. (C) Kaplan–Meier overall survival curves for patients with CRC stratified by low (n = 37) and high (n = 52) expression of RCN3 (P = 0.000).

Enrichment Analysis of RCN3-Related Pathways in Human Cancers

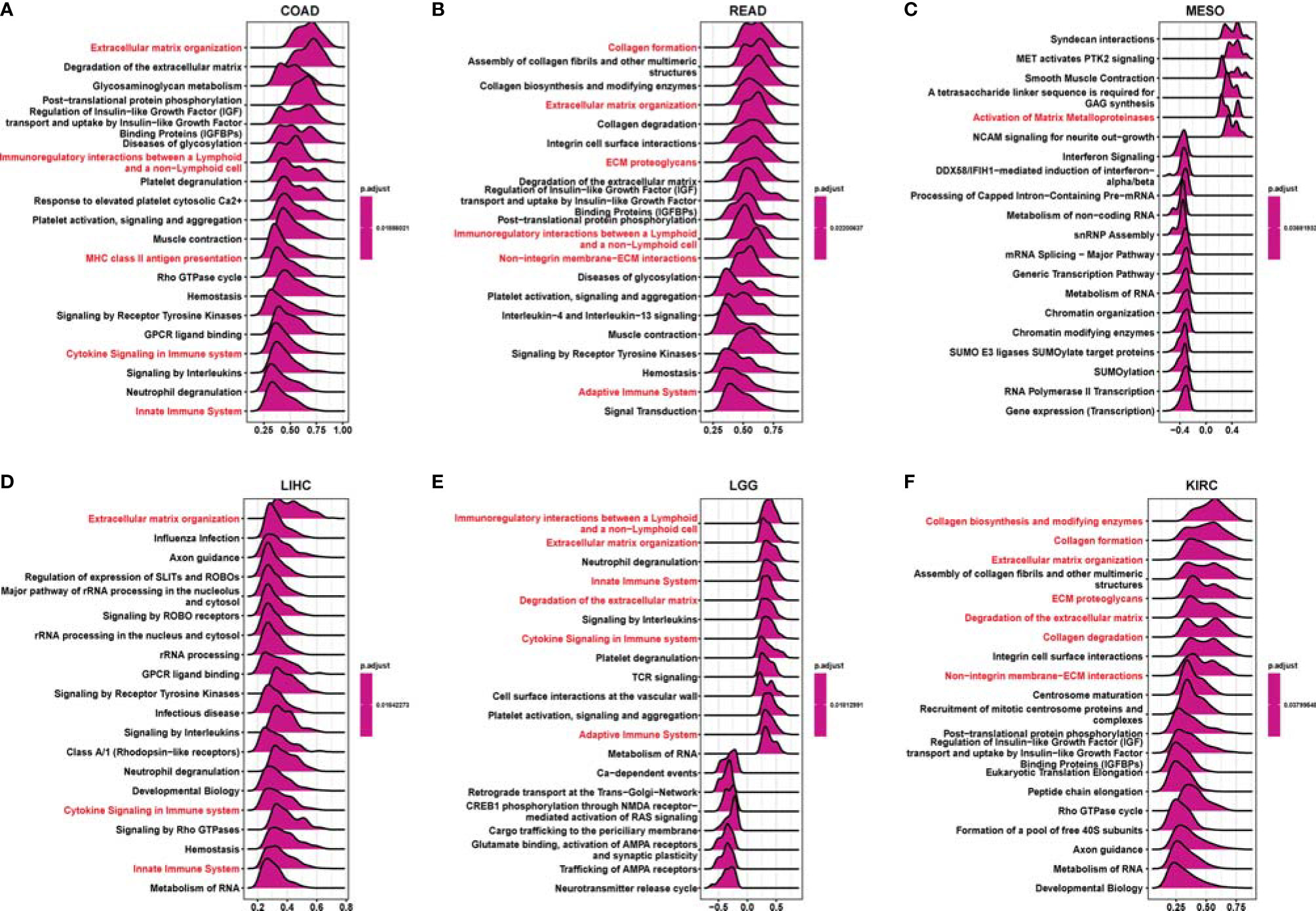

GSEA was performed to further explore the potential biological functions of RCN3 in different cancers. The top 20 categories of each cancer are displayed. The GO GESA results indicated the enrichment in many categories and RCN3 had a main effect on terms about the extracellular matrix-related processes such as “extracellular matrix organization”, “collagen formation”, “ECM proteoglycans”, “non-integrin membrane-ECM interaction”, and “degradation of the extracellular matrix” and immune-related regulation mechanisms such as “cytokine signaling in immune system”, “immunoregulatory interactions between a lymphoid and a non-lymphoid cell”, “innate immune system”, “adaptive immune system”, and “MHC class II antigen presentation” in a large fraction of cancers, including COAD, READ, MESO, LIHC, LGG, and KIRC (Figure 6). KEGG GSEA analysis demonstrated that RCN3 was mainly involved in “ECM − receptor interaction”, “cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction”, “focal adhesion”, “PI3K − Akt signaling pathway”, “chemokine signaling pathway”, “pathways in cancer”, and “Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation” in COAD, READ, MESO, LIHC, LGG, and KIRC (Supplementary Figure 6).

Figure 6 Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of tumor samples with expression of RCN3. (A–F) The plot showing the top 20 categories enriched in GO analysis via GSEA. The extracellular matrix related pathways and immune-related regulation mechanisms (red) were the main enriched terms in a large fraction of cancers, such as COAD, READ, MESO, LIHC, LGG, and KIRC.

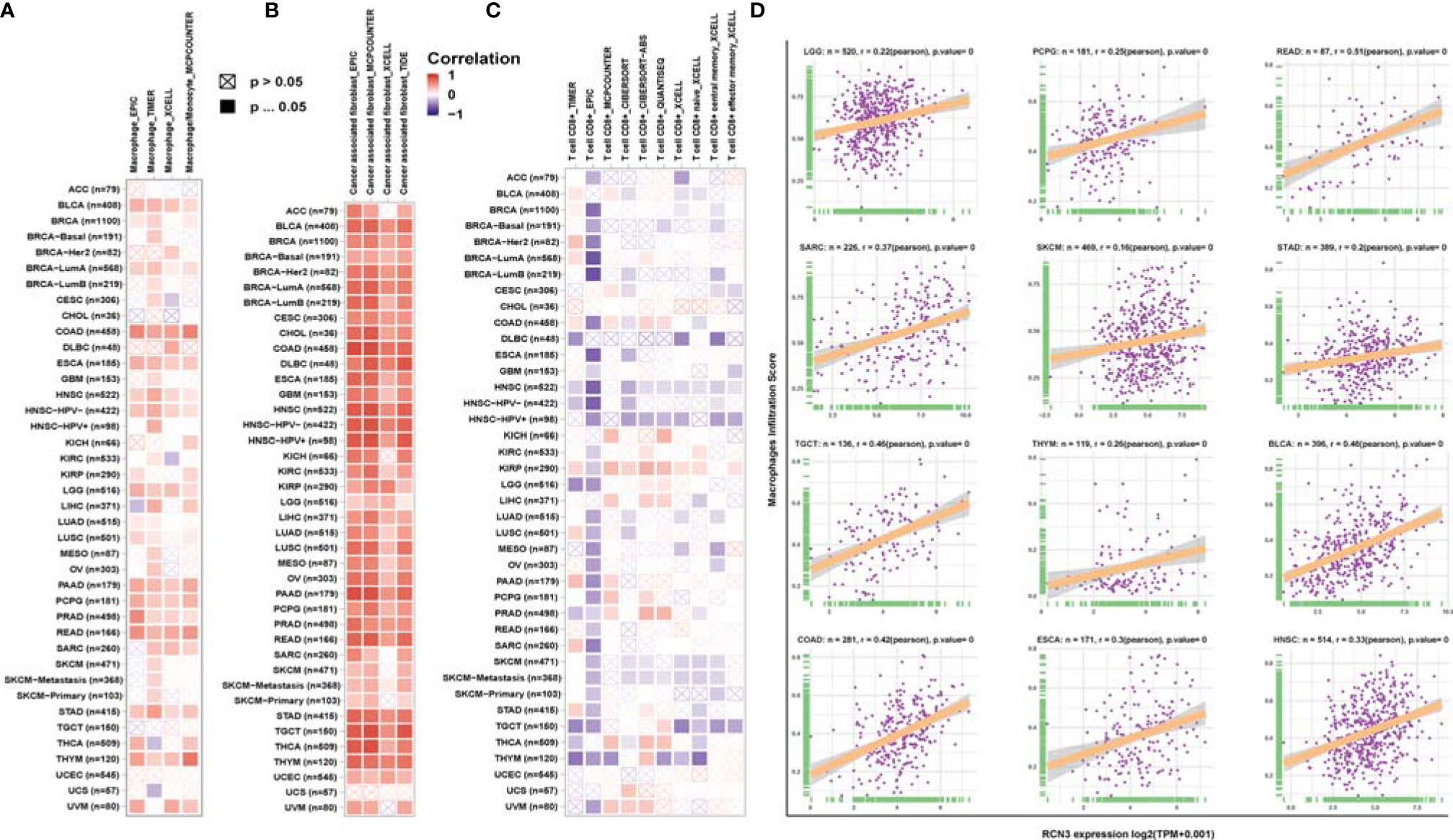

Correlation Analysis of RCN3 Expression and Immune Infiltration Levels Across Cancers

Tumor-infiltrating immune cells in the tumor microenvironment had a close connection with the tumor biology process and cancer patients’ survival (4). Evidence suggests that cancer-associated fibroblasts in the TME affected the function of various tumor-infiltrating immune cells (30–32). Therefore, TIMER, EPIC, XCELL, MCPCOUNTER, TIDE, CIBERSORT, CIBERSORT-ABS, and QUANTISEQ algorithms were used to identify the potential correlation between RCN3 expression and the infiltration level of immune cells in human pan-cancer. We found a statistical positive correlation between the macrophages and RCN3 expression in tumors of BLCA, BRCA-LumA, COAD, ESCA, HNSC, HNSC-HPV-, LGG, PAAD, PCPG, PRAD, READ, STAD, and THYM (Figure 7A) via all or most algorithms we used. We also observed a significant positive correlation of RCN3 expression and the infiltration level of cancer-associated fibroblasts in diverse cancer types of TCGA (Figure 7B) via all or most algorithms we used. Moreover, considering macrophages’ function in suppressing T cells, we investigated the relationship between RCN3 and CD8+ T cells. Our results showed that RCN3 expression level was negatively correlated with the level of immune infiltration of CD8+ T-cells in the tumors of HNSC, HNSC-HPV+, SKCM, and SKCM-metastasis. (Figure 7C). Moreover, the cell-specific expression of RCN3 was also derived using the UALCAN database and found that notheness in solid or nonsolid tumor cells, RCN3 showed a high expression in immune cells and fibroblast cells (Supplementary Figure 7). These results indicated that RCN3 may play an important role in regulating tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment in pan-cancer, with a positive correlation with macrophages and cancer-association fibroblasts but a negative correlation with CD8+ T-cells.

Figure 7 Relationship between RCN3 expression and infiltration levels of immune cells. Based on the TIMER2 database, we analyzed the potential correlation between the expression level of the RCN3 and the infiltration levels of tumor-associated macrophage (A), cancer-associated fibroblasts (B), and CD8+ T cells (C). (D) Correlation analysis of RCN3 expression with macrophages infiltration score in cancers from TCGA by CIBERSORT.

To further verify the relationship between RCN3 expression and infiltration levels of macrophages, correlation analyses were conducted using immune cell infiltration data we downloaded from published work (28), which evaluated immune cells using the CIBERSORT tool. The scatterplot data presented in Figure 7D illustrates that the RCN3 expression levels were positively correlated with the macrophages infiltration score in a variety of cancers like LGG, PCPG, READ, SARC, SKCM, STAD, TGCT, THYM, and BLCA, which is consistent with the results from TIMER.

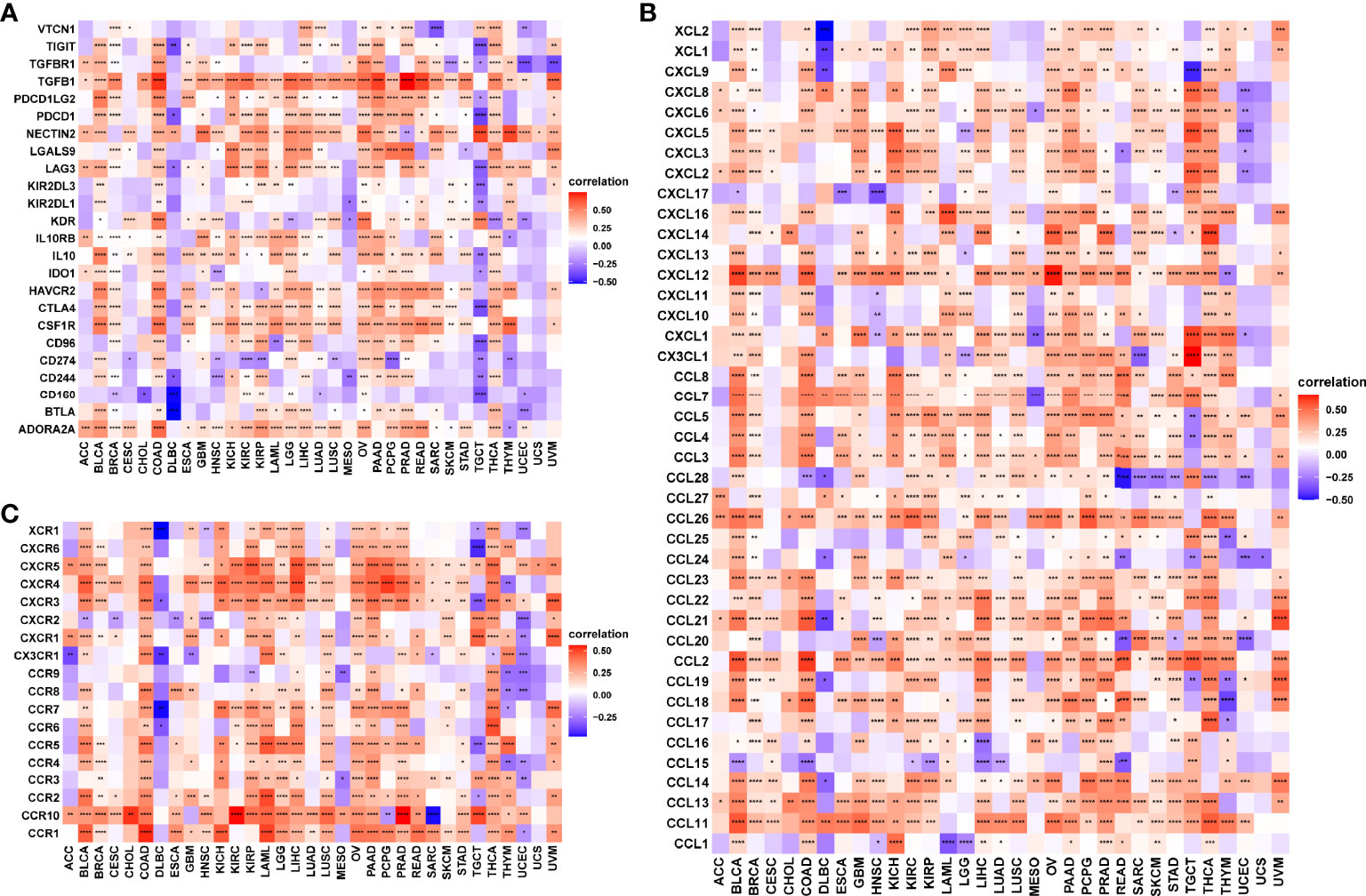

Association of RCN3 Expression with Immuno-Related Genes

Our pan-cancer analysis revealed the significant positive correlations of RCN3 expression with macrophages in most cancers from TCGA. Herein, we applied correlation analysis between RCN3 expression and tumor immunosuppression-related genes for further validation. The heat-map (Figure 8A) according to the correlation between RCN3 and multiple immunoinhibitory molecules including TIGIT, TGFB1, PDCD1LG2, PDCD1, NECTIN2, LGALS9, LAG3, IL10RB, IL10, HAVCR2, CTLA4, CSF1R, CD96, BTLA, and ADORA2A in pan-cancer suggested that most correlations were positive. It is essential to note that TGFB1, which is an effector of immune suppression, showed strong positive correlations with RCN3 expression levels in the vast majority of TCGA cancer types. Moreover, significant correlations were found between almost all tumor immunosuppression-related genes we assessed and RCN3 in COAD. We also focused on the relationship between RCN3 expression and chemokines (Figure 8B) and chemokines receptors (Figure 8C). High RCN3 expression was positively associated with multiple chemokines, especially CXCR5, CXCR4, CXCR3, CCR10, CCR2, and CCR1. RCN3 expression had a significant positive association with various chemokine receptors in different cancers as well. Our results suggested the RCN3 gene plays a vital role in tumor immunity and confirmed that high RCN3 expression level was positively associated with tumor immunosuppression in multiple cancer types. High RCN3 expression indicated tumor immune inhibition status may not be conducive to immunotherapy.

Figure 8 Correlation analysis between RCN3 expression and immuno-related genes. Correlation analysis between RCN3 expression and immunosuppression-related genes (A), chemokines (B), and chemokines receptors (C). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

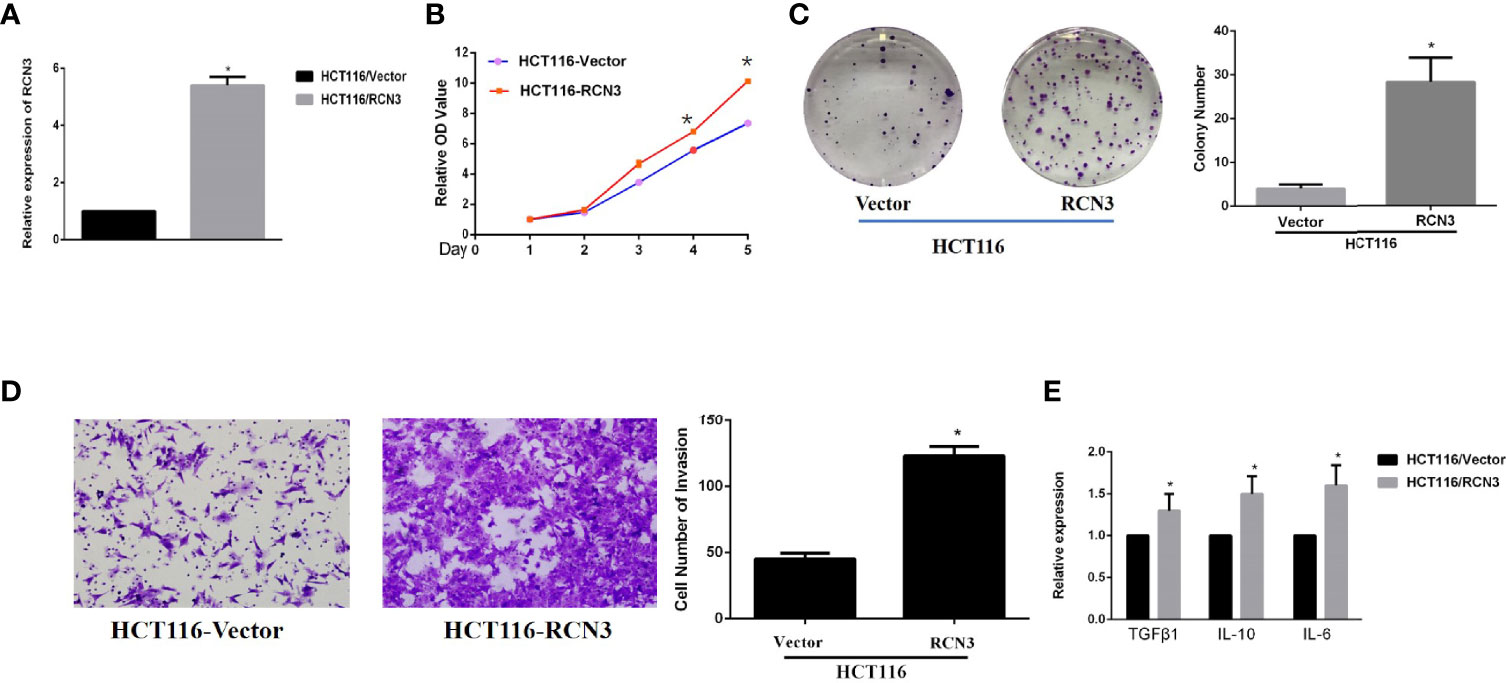

RCN3 Promoted the Proliferation and Invasion Ability and Increased Expression of Tumor Immune Related Gene of CRC Cells In Vitro

Finally, we performed the in vitro experiment in CRC cells to further identify the oncogenic role of RCN3. Interestingly, overexpression of RCN3 exhibited a remarkable promotion of cell proliferation ability and cell colony formation (Figures 9A, B). Also, overexpression of RCN3 in HCT116 cells promotes the invasion ability compared with the control group (Figure 9C).

Figure 9 Fold change of expression level of RCN3’s RNA expression after transfection in HCT-116 was shown (A). Over-expression of RCN3 significantly promotes the proliferation and invasion ability in CRC cells (B-D) and promotes the expression of immune related factor, including TGFβ1, IL-10, and IL-6 (E). *p < 0.05

Moreover, qRT-PCR experiments of the indicated cell lines showed that overexpression of RCN3 showed a significantly increased level of TGFβ1, IL-10, and IL-6, indicating that RCN3 might promote oncogenic progress of CRC with immunological regulation, which also matched our previous bioinfomatic analysis of its pan-cancer role (Figure 9D).

Discussion

Reticulocalbin 3 (RCN3) is known as an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen protein function in the secretory pathway (12, 13). Many studies have revealed that RCN3 participates in a series of biological processes such as apoptosis, ER stress, and collagen fibrillogenesis in tissues producing extracellular matrix (14–16). Despite emerging publications have elucidated a functional association between RCN3 and diversity clinical diseases, such as tumors (17–21), there is no evidence about a pan-cancer analysis of RCN3 based on overall cancers. Whether RCN3 can affect tumor pathogenesis through certain common molecular mechanisms is not yet fully established. Thus, we comprehensively assessed molecular characteristics of RCN3 expression, genetic and epigenetic signature, prognostic value, and its potential oncogenic role in regulating immune infiltration and tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment in TCGA pan-cancer.

We first analyzed RCN3 expression characteristics in tumor and normal tissues from TCGA and GTEx database, RCN3 was highly expressed in most tumors, such as LUSC, LUAD, LIHC, KIRC, HNSC, ESCA, COAD, CHOL, BRAC, and GBM. In contrast, low RCN3 expression was observed only in KICH and CESC. We also detected a correlation between high expression levels of RCN3 and higher pathological stages in ACC, BLCA, BRCA, COAD, ESCA, HNSC, READ, SKCM, and THCA. It has been reported that RCN3 is a biomarker of poorer prognosis of colorectal cancer (21). In this study, our analysis of univariate Cox proportional-hazards regression suggested the link between RCN3 expression and overall survival prognosis in 12 cancer types. Additionally, the Kaplan-Meier analysis also represented a significant correlation between high RCN3 expression and poor clinical prognosis of OS in COAD, READ, MESO, LIHC, LGG, and KIRC. Furthermore, our results also suggested that high RCN3 expression indicated poor DFI, PFI, and DSS in different tumors. Consequently, RCN3 was highly expressed in most cancers and high RCN3 expression was generally associated with poor outcomes in most cancers. To further identify its prognostic roles, we derived a TAM experiment of CRC tissue and found that expression levels of RCN3 significantly correlated with the aggressive characteristics of the cancer (AJCC stage, tumor size, and nodal metastasis) as well as poor survival of patients. These findings are consistent with the pan-cancer analysis and suggested that RCN3 might be a universal tumor biomarker to identify patients with poor clinical outcomes.

Tumor immunotherapy is a promising approach for the treatment of cancer. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), such as anti-CTLA4, anti-PD1, and anti-PDL1, genetically engineered T-cell therapy like CAR T-cell therapy, have improved survival in tumor patients. However, the anti-tumor efficacy remains limited in clinical applications (33–35). One of the major challenges rendering tumors resistant is the aberrant tumor microenvironment (TME). The main components of infiltrating stromal cells in the TME are tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), and they are reported to play a vital role in tumor progression and chemo-resistance (36). A previous article reported that fibroblasts with somatic copy number alterations in the TME play synergetic roles in tumor development through complex interactions with cancer cells, and RCN3 is identified as a fibroblast-specific biomarker of poorer prognosis of colorectal cancer (CRC) (21). In contrast, the tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TLSs), CD8+ T lymphocytes, play a pivotal role in survival prognosis, tumor regression, and antitumor immunity, through weakening CD8+ T cell activation, immunosuppressive factors in TME maintain tumor immune inhibition status (37–39). Thus, TAMs and CAFs are potential target cells for cancer treatment. In our study, using the GSEA tool, we integrated the information that RCN3 had a main effect on the extracellular matrix-related pathways and immune-related regulation mechanisms. Moreover, we identified that RCN3 expression was positively correlated with TAMs and CAFs but negatively correlated with CD8+ T-cells in pan-cancer via TIMER2 and analyzed data from a published work. Our results indicated that RCN3 may play a significant role in regulating tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment in pan-cancer. Furthermore, we investigated the correlations between RCN3 expression and tumor immunosuppression-related genes, chemokines, and chemokines receptors. Many immunoinhibitory molecules such as TIGIT, TGFB1, PDCD1LG2, PDCD1, NECTIN2, LGALS9, LAG3, IL10RB, IL10, HAVCR2, CTLA4, CSF1R, CD96, BTLA, and ADORA2A were positively correlated with RCN3 in most cancer types. Chemokines and chemokine receptors such as CCL2, CCL11, CXCR5, CXCR4, CXCR3, CCR10, CCR2, and CCR1 were also positively correlated with RCN3 expression in most cancer types. The interaction between tumors and tumor immune microenvironment is complicated. Evidence shows that TAMs secret multiple immunosuppressive mediators, such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-B1 and interleukin-10 (IL-10), CCL2-CCR2 pathways, play a crucial role in hindering immunotherapy efficiency tumor and promoting tumor progression (40–43). Our results suggested the RCN3 gene plays a vital role in tumor immunity and high RCN3 expression may indicate tumor immune inhibition status.

Genetic and epigenetic alterations are closely linked to tumorigenesis and tumor immunogenicity, for example, dysregulated DNA methylation can lead to aberrant gene expression and promote cancer onset, which meanwhile may vary response to immune regulation in cancer development (44). Using the cBioPortal tool, we observed the genetic alteration status of RCN3, the results revealed a significant positive correlation between RCN3 expression and CNA. Additionally, there was a significant negative correlation between RCN3 expression and DNA methylation in pan-cancer. To further explore the role of RCN3 in tumorigenesis and immune regulation, we applied GESA KEGG analysis. The results indicated a correlation between RCN3 and oncogenic pathways, such as PI3K − Akt, pathways in cancer, and Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation. The precise molecular mechanisms that RCN3 plays an oncogenic role deserved to be clarified. Our research also has certain limitations. We have limits in our experiments still and the mechanism that can help us better understand the effects of RCN3 both in pan-cancer and colorectal cancer, in which we are interested, remains to be explored. More sufficient in vivo and in vitro experimental evidence should be provided to verify the oncogenic function of RCN3 and clinical trials should be performed to determine the role of RCN3 as an immunotherapeutic biomarker.

In summary, our first pan-cancer analyses explored RCN3 expression characteristics, prognostic significance, immune cell infiltration, and associated pathways using bioinformatics methods. We conducted a comprehensive analysis of RCN3, revealing its potential pro-tumor effect as well as its function of indicating patient prognosis. Importantly, high RCN3 expression often suggests tumor immune inhibition status, which may not be conducive to immunotherapy. Our research validated the importance of RCN3 in cancer and a comprehensive understanding of its role as a therapeutic biomarker is worth further exploration.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

KZ and SL designed the study. JD, YM, XL, and ZH recorded the data. XG and YL analyzed the data. JD and YM drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the submitted version of the paper.

Funding

The project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81802965), the Presidential Foundation of Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University (Grant No. 2020B020), Guangdong gastrointestinal disease research center (No. 2017B020209003), the National Natural Science Funds of China (12026605).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Pazhou Lab, Guangzhou for its support of this research.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2022.811567/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | The expression level of RCN3 in cancers. (A–J) Based on the TCGA data, the expression levels of RCN3 in different tumor tissues and matched normal tissues were analyzed using the ggpubr package.

Supplementary Figure 2 | DNA methylation of RCN3 in human cancers. Using the cBioportal tool, we explored the correlations between RCN3 expression and DNA methylation. R>0.3, P<0.05 is considered statistically significant, and only statistical results are shown here.

Supplementary Figure 3 | CNA of RCN3 in human cancers. Using the cBioportal data bank, we analyzed the relationship between RCN3 expression and relative linear copy-number values. R>0.2, P<0.05 is considered statistically significant, and only statistical results are shown here.

Supplementary Figure 4 | The prognostic significance of RCN3 in pan-cancer. (A) Univariate Cox proportional-hazards regression used to quantify the relationship of RCN3 with DFI (A), PFI (B), and DSS (C). DFI, disease-free interval; PFI, progression-free interval; DSS, disease-specific survival.

Supplementary Figure 5 | Correlation ship of RCN3 and tumor metastasis. High expression of RCN3 share a higher nodal metastasis stage in ACC, COAD, BRCA, and READ (A–D), and a GSVA analysis of 32 cancer types showed that expression of RCN3 significantly correlated with the pathway of epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) (E).

Supplementary Figure 6 | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of RCN3 in pan-cancer. (A–F) The plot shows the top 20 pathways enriched in KEGG analysis via GSEA. Significant KEGG pathways influenced by RCN3 expression in COAD, READ, MESO, LIHC, LGG, and KIRC were analyzed by GSEA.

Supplementary Figure 7 | Cell-specific expression of RCN3 was also derived using the UALCAN database and found that notheness in solid or nonsolid tumor cells, RCN3 showed a high expression in immune cells and fibroblast cells.

Abbreviations

RCC, renal cell carcinoma; UCEC, uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma; LUSC, lung squamous cell carcinoma; LUAD, lung adenocarcinoma; LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; KIRC, kidney renal clear cell carcinoma; HNSC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; ESCA, esophageal carcinoma; COAD, colon adenocarcinoma; CHOL, cholangiocarcinoma; BRAC, breast invasive carcinoma; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; KICH, kidney chromophobe; CESC, cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; ACC, adrenocortical carcinoma; BLCA, bladder urothelial carcinoma; READ, rectum adenocarcinoma; SKCM, skin cutaneous melanoma; THCA, thyroid carcinoma; SARC, sarcoma; UCEC, uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma; UCS, uterine carcinosarcoma; UVM, uveal melanoma; GBM, glioblastoma multiforme; LGG, brain lower grade glioma; MESO, mesothelioma; OV, ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma; PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma; PRAD, prostate adenocarcinoma.

References

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin (2021) 71(1):7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654

2. Jain RK. Normalizing Tumor Microenvironment to Treat Cancer: Bench to Bedside to Biomarkers. J Clin Oncol (2013) 31(17):2205–18. doi: 10.1200/jco.2012.46.3653

3. Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, Ribas A. Primary, Adaptive, and Acquired Resistance to Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell (2017) 168(4):707–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.017

4. Fridman WH, Galon J, Dieu-Nosjean MC, Cremer I, Fisson S, Damotte D, et al. Immune Infiltration in Human Cancer: Prognostic Significance and Disease Control. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol (2011) 344:1–24. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_46

5. Casey SC, Amedei A, Aquilano K, Azmi AS, Benencia F, Bhakta D, et al. Cancer Prevention and Therapy Through the Modulation of the Tumor Microenvironment. Semin Cancer Biol (2015) 35Suppl:S199–223. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.02.007

6. Zhang Y, Chen L. Classification of Advanced Human Cancers Based on Tumor Immunity in the MicroEnvironment (TIME) for Cancer Immunotherapy. JAMA Oncol (2016) 2(11):1403–4. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.2450

7. Hegde PS, Chen DS. Top 10 Challenges in Cancer Immunotherapy. Immunity (2020) 52(1):17–35. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.12.011

8. Ghahremanloo A, Soltani A, Modaresi SMS, Hashemy SI. Recent Advances in the Clinical Development of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy. Cell Oncol (Dordr) (2019) 42(5):609–26. doi: 10.1007/s13402-019-00456-w

9. Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, Shukla SA, Blank C, Zimmer L, et al. Genomic Correlates of Response to CTLA-4 Blockade in Metastatic Melanoma. Science (2015) 350(6257):207–11. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0095

10. Honoré B. The Rapidly Expanding CREC Protein Family: Members, Localization, Function, and Role in Disease. Bioessays (2009) 31(3):262–77. doi: 10.1002/bies.200800186

11. Honoré B, Vorum H. The CREC Family, a Novel Family of Multiple EF-Hand, Low-Affinity Ca(2+)-Binding Proteins Localised to the Secretory Pathway of Mammalian Cells. FEBS Lett (2000) 466(1):11–8. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01780-9

12. Tsuji A, Kikuchi Y, Sato Y, Koide S, Yuasa K, Nagahama M, et al. A Proteomic Approach Reveals Transient Association of Reticulocalbin-3, a Novel Member of the CREC Family, With the Precursor of Subtilisin-Like Proprotein Convertase, PACE4. Biochem J (2006) 396(1):51–9. doi: 10.1042/bj20051524

13. Martínez-Martínez E, Ibarrola J, Fernández-Celis A, Santamaria E, Fernández-Irigoyen J, Rossignol P, et al. Differential Proteomics Identifies Reticulocalbin-3 as a Novel Negative Mediator of Collagen Production in Human Cardiac Fibroblasts. Sci Rep (2017) 7(1):12192. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12305-7

14. Jin J, Li Y, Ren J, Man Lam S, Zhang Y, Hou Y, et al. Neonatal Respiratory Failure With Retarded Perinatal Lung Maturation in Mice Caused by Reticulocalbin 3 Disruption. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (2016) 54(3):410–23. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0036OC

15. Jin J, Shi X, Li Y, Zhang Q, Guo Y, Li C, et al. Reticulocalbin 3 Deficiency in Alveolar Epithelium Exacerbated Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol (2018) 59(3):320–33. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0347OC

16. Park NR, Shetye SS, Bogush I, Keene DR, Tufa S, Hudson DM, et al. Reticulocalbin 3 Is Involved in Postnatal Tendon Development by Regulating Collagen Fibrillogenesis and Cellular Maturation. Sci Rep (2021) 11(1):10868. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90258-8

17. Drucker KL, Kitange GJ, Kollmeyer TM, Law ME, Passe S, Rynearson AL, et al. Characterization and Gene Expression Profiling in Glioma Cell Lines With Deletion of Chromosome 19 Before and After Microcell-Mediated Restoration of Normal Human Chromosome 19. Genes Chromosomes Cancer (2009) 48(10):854–64. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20688

18. Hagedorn M, Siegfried G, Hooks KB, Khatib AM. Integration of Zebrafish Fin Regeneration Genes With Expression Data of Human Tumors in Silico Uncovers Potential Novel Melanoma Markers. Oncotarget (2016) 7(44):71567–79. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12257

19. Hou Y, Li Y, Gong F, Jin J, Huang A, Fang Q, et al. A Preliminary Study on RCN3 Protein Expression in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Lab (2016) 62(3):293–300. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2015.150411

20. Li Y, Liang Q, Wen YQ, Chen LL, Wang LT, Liu YL, et al. Comparative Proteomics Analysis of Human Osteosarcomas and Benign Tumor of Bone. Cancer Genet Cytogenet (2010) 198(2):97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2010.01.003

21. Zhou Y, Bian S, Zhou X, Cui Y, Wang W, Wen L, et al. Single-Cell Multiomics Sequencing Reveals Prevalent Genomic Alterations in Tumor Stromal Cells of Human Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Cell (2020) 38(6):818–28.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.09.015

22. Sahai E, Astsaturov I, Cukierman E, DeNardo DG, Egeblad M, Evans RM, et al. A Framework for Advancing Our Understanding of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Nat Rev Cancer (2020) 20(3):174–86. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0238-1

23. Li T, Fu J, Zeng Z, Cohen D, Li J, Chen Q, et al. TIMER2.0 for Analysis of Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells. Nucleic Acids Res (2020) 48(W1):W509–w514. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa407

24. Chandrashekar DS, Bashel B, Balasubramanya SAH, Creighton CJ, Ponce-Rodriguez I, Chakravarthi B, et al. UALCAN: A Portal for Facilitating Tumor Subgroup Gene Expression and Survival Analyses. Neoplasia (2017) 19(8):649–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2017.05.002

25. Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The Cbio Cancer Genomics Portal: An Open Platform for Exploring Multidimensional Cancer Genomics Data. Cancer Discov (2012) 2(5):401–4. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-12-0095

26. Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, et al. Integrative Analysis of Complex Cancer Genomics and Clinical Profiles Using the Cbioportal. Sci Signal (2013) 6(269):pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088

27. Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis: A Knowledge-Based Approach for Interpreting Genome-Wide Expression Profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2005) 102(43):15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102

28. Thorsson V, Gibbs DL, Brown SD, Wolf D, Bortone DS, Ou Yang TH, et al. The Immune Landscape of Cancer. Immunity (2018) 48(4):812–30.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.023

29. Newman AM, Steen CB, Liu CL, Gentles AJ, Chaudhuri AA, Scherer F, et al. Determining Cell Type Abundance and Expression From Bulk Tissues With Digital Cytometry. Nat Biotechnol (2019) 37(7):773–82. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0114-2

30. Chen X, Song E. Turning Foes to Friends: Targeting Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Nat Rev Drug Discov (2019) 18(2):99–115. doi: 10.1038/s41573-018-0004-1

31. Sliker BH, Campbell PM. Fibroblasts Influence the Efficacy, Resistance, and Future Use of Vaccines and Immunotherapy in Cancer Treatment. Vaccines (Basel) (2021) 9(6):634. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9060634

32. Kwa MQ, Herum KM, Brakebusch C. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts: How do They Contribute to Metastasis? Clin Exp Metastasis (2019) 36(2):71–86. doi: 10.1007/s10585-019-09959-0

33. Pan C, Liu H, Robins E, Song W, Liu D, Li Z, et al. Next-Generation Immuno-Oncology Agents: Current Momentum Shifts in Cancer Immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol (2020) 13(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00862-w

34. June CH, Sadelain M. Chimeric Antigen Receptor Therapy. N Engl J Med (2018) 379(1):64–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1706169

35. Bagley SJ, O’Rourke DM. Clinical Investigation of CAR T Cells for Solid Tumors: Lessons Learned and Future Directions. Pharmacol Ther (2020) 205:107419. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.107419

36. Komohara Y, Takeya M. CAFs and TAMs: Maestros of the Tumour Microenvironment. J Pathol (2017) 241(3):313–5. doi: 10.1002/path.4824

37. Xie Q, Ding J, Chen Y. Role of CD8(+) T Lymphocyte Cells: Interplay With Stromal Cells in Tumor Microenvironment. Acta Pharm Sin B (2021) 11(6):1365–78. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.027

38. Palazon A, Tyrakis PA, Macias D, Veliça P, Rundqvist H, Fitzpatrick S, et al. An HIF-1α/VEGF-A Axis in Cytotoxic T Cells Regulates Tumor Progression. Cancer Cell (2017) 32(5):669–83.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.10.003

39. Zhang N, Yin R, Zhou P, Liu X, Fan P, Qian L, et al. DLL1 Orchestrates CD8+ T Cells to Induce Long-Term Vascular Normalization and Tumor Regression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2021) 118(22):e2020057118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2020057118

40. Noy R, Pollard JW. Tumor-Associated Macrophages: From Mechanisms to Therapy. Immunity (2014) 41(1):49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.010

41. De Palma M, Lewis CE. Macrophage Regulation of Tumor Responses to Anticancer Therapies. Cancer Cell (2013) 23(3):277–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.02.013

42. Locati M, Curtale G, Mantovani A. Diversity, Mechanisms, and Significance of Macrophage Plasticity. Annu Rev Pathol (2020) 15:123–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012718

43. Anderson NR, Minutolo NG, Gill S, Klichinsky M. Macrophage-Based Approaches for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer Res (2021) 81(5):1201–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-20-2990

Keywords: pan-cancer, RCN3, immunotherapy, prognosis, potential biomarker

Citation: Ding J, Meng Y, Han Z, Luo X, Guo X, Li Y, Liu S and Zhuang K (2022) Pan-Cancer Analysis of the Oncogenic and Immunological Role of RCN3: A Potential Biomarker for Prognosis and Immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 12:811567. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.811567

Received: 09 November 2021; Accepted: 25 March 2022;

Published: 16 May 2022.

Edited by:

Jian-Guo Zhou, University of Erlangen Nuremberg, GermanyReviewed by:

Pingping Chen, University of Miami, United StatesWenliang Li, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, United States

Kang Wei, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, China

Copyright © 2022 Ding, Meng, Han, Luo, Guo, Li, Liu and Zhuang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kangmin Zhuang, emttMTAwMkAxMjYuY29t; Side Liu, bGl1c2lkZTIwMTFAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Jian Ding

Jian Ding