95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Oncol. , 07 July 2020

Sec. Radiation Oncology

Volume 10 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.01120

This article is part of the Research Topic Cell Signaling Mediating Critical Radiation Responses View all 15 articles

Radiotherapy has been used in the clinic for more than one century and it is recognized as one of the main methods in the treatment of malignant tumors. Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription 3 (STAT3) is reported to be upregulated in many tumor types, and it is believed to be involved in the tumorigenesis, development and malignant behaviors of tumors. Previous studies also found that STAT3 contributes to chemo-resistance of various tumor types. Recently, many studies reported that STAT3 is involved in the response of tumor cells to radiotherapy. But until now, the role of the STAT3 in radioresistance has not been systematically demonstrated. In this study, we will review the radioresistance induced by STAT3 and relative solutions will be discussed.

With the development of technology and our understanding of tumors, there are multiple methods for the treatment of tumors, such as surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and immunotherapy. Among all these approaches to treatment, radiotherapy is one of the most cost-effective methods for the treatment of various cancers. Since its introduction into the clinic, radiotherapy has existed for more than one century, which shows that its efficiency is well-approved (1). But for some tumor types, radiotherapy doesn't work so well. Until now, we have recognized that after irradiation treatment, tumor cells develop complicated mechanisms, like DNA repair, cell cycle arrest, and autophagy, to protect themselves so as to survive (2–4). As a result, most tumor cells will develop radioresistance, which leads to the failure of radiotherapy. Although many methods have been used to overcome radioresistance, their efficiency is not as what we have expected (5, 6). Thus, more research is needed to help us have a better understanding of radioresistance.

Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription 3 (STAT3), one of the most important intracellular transcription factors, is reported to be constitutively activated in most tumor types (7, 8). Many cytokines, hormones and growth factors are involved in the activation of STAT3, among which canonical Janus kinase (JAK) is the most studied (9). STAT3 plays an important role in cell proliferation, and is also involved in anti-apoptosis process (9). Besides, STAT3 also promotes angiogenesis, invasiveness and immunosuppression in cancer (10–12). All these functions are related to STAT3's role in controlling gene transcription. Previously, STAT3 was recognized as a direct transcription factor. For example, STAT3 regulates pro-survival gene expression to increase apoptotic resistance in cancer. But more and more recent studies discover that STAT3 also regulates gene expression through DNA methylation and chromatin modulation (9).

Previously, STAT3 is reported to be involved in chemo-resistance and this is well-reviewed by Tan et al. (13). Recently, more and more studies showed that STAT3 contributed to radioresistance. Huang et al. showed that sorafenib and its derivative could increase the anti-tumor effect of radiotherapy by inhibiting STAT3 (14, 15). Lau et al. found that blocking STAT3 could inhibit radiation-induced malignant progression, such as increased migration and invasion (16). These studies have shown that STAT3 is not only involved in tumorigenesis and tumor development, but also leads to chemo- and radio-resistance. Here, we mainly review the role of STAT3 in mediating radioresistance from points of apoptosis, aggressive behaviors, DNA damage repair, cancer stem cells. And novel modalities to reverse the failure of radiotherapy will be discussed.

Apoptosis is essential for the maintenance of normal physiological functions in normal cells. But anti-apoptosis process could be induced in tumor cells after chemo- or radio-therapy, so as to help them survive (17).

The B cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) family of proteins are important among all the factors that are involved in regulating programmed cell death or apoptosis (18). BCL-2 family of proteins are mainly mitochondria localized and involved in the release of cytochrome C, an essential mediator of apoptosis (19, 20). They possess BH 1–4 domains and have the function of maintaining mitochondrial integrity. STAT3 is involved in tumorigenesis by activating anti-apoptotic proteins, like surviving (17, 21). Conversely, inhibiting STAT3 increases apoptosis (22, 23). Besides, a study found that heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) has anti-apoptosis effect by preventing JNK-induced phosphorylation and inhibiting BCL-2 and BCL-XL, so as to maintain the stability of mitochondria (24). STAT3 can affect the Hsp70 promoter and increases its expression in cancer cells, mediating the upregulation of antiapoptotic proteins (25). As a result, we assume that inhibiting STAT3 could decrease the expression of antiapoptotic proteins, leading to apoptosis.

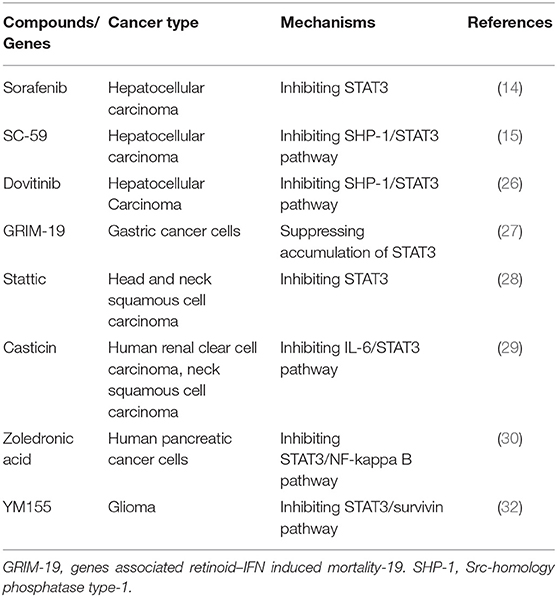

Until now, there are a large number of studies showing that inhibiting STAT3 increases radiosensitivity in numerous tumor types (14, 15, 26–31), which are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. A summary of pre-clinical studies in which STAT3-targeted compounds are used to enhance the radiosensitivity of malignant tumors by inducing apoptosis.

Studies showed that STAT3 is one of the most important regulators of survivin (33, 34). Survivin, a member of the inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) family and one of the most important anti-apoptotic proteins, is found highly expressed in various cancer types, making it a potential anticancer target (35, 36).

Several studies found that inhibiting survivin could enhance radiosensitivity in various tumor types. Grdina et al. found that the expression of survivin upregulated after irradiation treatment and increased survivin promoted cell survival, while knocking down survivin with siRNA abrogated this adaptive response (37). Iwasa et al. showed that YM155, an inhibitor of survivin, enhanced radiosensitivity in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines (38). Qin et al. showed that YM155 increases radiosensitivity in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by the inhibiting cell cycle checkpoint and homologous recombination repair (32).

But these studies didn't demonstrate whether the radiosensitive effect of YM155 is STAT3-dependent. Our recent study found that YM155 decreased the activity of STAT3 and increased the radiosensitivity of glioblastoma, one of the most radioresistant tumor types. This might provide some clues for the role of STAT3/survivin pathway in the radioresistance of various neoplasms (31). Further studies are warranted to clarify the direct interaction between STAT3 and survivin after irradiation treatment.

Although irradiation kills cancers, we have to recognize that it can also induce carcinogenesis. The carcinogenic potential of ionizing radiations could be traced back to 1902 and more radiation-induced (RI) neoplasia have been observed (39, 40). Over the last 45 years, 296 cases of radiation-induced brain tumors have been reported.

Except for RT tumors, more and more studies discovered that radiation might enhance malignant progression, like aggressive migration and invasion in cancer cells (16, 41–45). This will induce more extensive spread of tumor cells, which is a contributing factor to tumor relapse and recurrence (46, 47).

Among all the mechanisms that explaining radiation-induced migration and invasion, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) accounting for the most. In the process of EMT, epithelial characteristics will be downregulated and mesenchymal characteristics will be gained in epithelial cells. This phenomena were reported by Elizabeth Hay in the early 1980s (48). Cancer cells underwent EMT will acquire elevated capabilities to invade and disseminate to distant sites, which increases its malignance.

Previous studies showed that among all signaling pathways that are involved in EMT, STAT3 is one of the most important (49–51). Many studies found that irradiation actually promoted EMT process (43, 52, 53). Lau et al. found that blocking STAT3 decreased radiation-induced malignant behaviors in glioma (16). Our previous study showed that YM155 not only decreased DNA damage repair, but also decreased radiation-induced invasion and reversed EMT by inhibiting STAT3, which was a promising radiosensitizer in the treatment of cancer (31). But whether it has the same effect in other tumor types is still unknown.

Except for EMT process, there are other mechanisms to explain for the increased invasive ability induced by irradiation (42, 54–61), which are summarized in Table 2. But whether they have relationships with STAT3 is still unknown.

Yu et al. showed that irradiated breast cancer cells could promote the invasion of non-irradiated tumor cells and angiogenesis through IL-6/STAT3 signaling (62). This might explain that STAT3 plays a role in radiation-induced bystander effect (RIBE) (63). RIBE happens when irradiated cells affect non-irradiated cells through gap junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) or the release of soluble factors (64). Results induced by RIBE are still unclear. Some studies found decreased survival in unirradiated cells, whereas others observed that RIBE helped irradiated cells survive (65).

Duan et al. showed that irradiation of normal brain before tumor cell implantation contributed to aggressive tumor growth, which suggested a brain tumor microenvironment-induced, tumor-extrinsic effect (66). Tumor microenvironment (TM) is mainly composed of epithelial cells, stromal cells, extracellular matrix (ECM) components or immune cells (67). The concept of TM can be traced back to 1889, when Paget put forward the concept, “seed and soil” (68). The role of TM in tumorigenesis and development is attracting more and more attention. Studies also found that TM contributed to chemo- or radio-resistance (67, 69, 70).

Recent studies also verified the important role of STAT3 in tumor microenvironment. A study by Chang et al. concluded that IL-6/JAK/STAT3 pathways played a key role in regulating the tumor microenvironment that promoted growth, invasion, and metastasis (71). Deng et al. reported that sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor type 1 (S1PR1)-STAT3 signaling was activated in pre-metastatic sites, contributing to the formation of pre-metastatic niche (72). Bohrer et al. found that upregulation of the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR)-STAT3 signaling in breast cancer cells led to a hyaluronan-rich microenvironment, which helped tumor progression (73).

STAT3 also established an immunosuppressive microenvironment to promote the growth and metastasis breast cancer (74). All these studies showed that STAT3 played an important role in tumor microenvironment-induced aggressive behaviors, which made STAT3 a promising target in the radiorensitization of cancers. A study by Gao et al. showed that myeloid cell-specific inhibition of Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9)/STAT3 signaling enhanced the antitumor effect of irradiation (75). More studies are warranted in the future to verify whether targeting STAT3 is efficient in inhibiting irradiation-induced malignant behaviors of cancers.

Ionizing radiation damages DNA mainly in two ways, by direct and indirect action. Direct action occurs by ionization in the DNA molecule itself. On the other hand, ionization of water produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and these free radical species (in particular the OH radical) damage DNA by indirect action (31). The efficacy of radiotherapy is mainly determined by DNA damage. However, radioresistance can be induced after repeat radiotherapy treatment. Among all the cellular processes that are involved in the development of radioresistance, DNA damage repair is one of the most important factors (76).

When DNA damage occurs, a series of sequential reactions are induced to maintain the consistency and integrity of genetic material. These reactions are called DNA damage repair (77). Among all the pathways that are involved in DNA damage repair, ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM)- check-point kinase 2 (Chk2) and ATM and Rad3-related (ATR)- check-point kinase 1 (Chk1) signaling pathways are the best studied. ATM and ATR are recognized as the central components of the DNA damage response (78, 79). When DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) occur, ATM is upregulated and activates the phosphorylation of important proteins like check-point kinase 2 (Chk2), p53, and BRCA1 (80, 81). ATR initiates the late phosphorylation of p53 and check-point kinase 1 (Chk1) (82, 83). Details can be seen in the review by Zhang et al. (84).

There are various types of DNA damage, like base damage, deletion, insertion, exon skipping, single strand breaks and double strand breaks (DSBs). Among them, DSBs are the most lethal. There are mainly two mechanism in repairing DSBs, non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR). In the process of NHEJ, ligation occurs regardless of whether the ends come from the same chromosome. As a result, mistakes might occur. On the other hand, HR uses the information that is usually from the sister chromatid to repair damaged DNA. So, HR has a higher accuracy in repairing DNA (76).

Recently, more and more studies showed that STAT3 was involved in DNA damage repair. STAT3 was reported to be involved in the regulation of breast cancer susceptibility gene 1 (BRCA1), an important factor in DNA damage repair, especially HR (85, 86). Barry et al. showed that knocking down STAT3 impaired the efficiency of damage repair by downregulating the ATM-Chk2 and ATR-Chk1 pathways (87). Essential meiotic endonuclease 1 homolog 1 (Eme1), a key endonuclease involved in DNA repair, was reported to be the downstream of STAT3 (88–90).Chen et al. showed that silencing Jumonji domain-containing protein 2B (JMJD2B) activated DNA damage by the suppression of STAT3 signaling (91). All these studies suggested that STAT3 was part of DNA damage repair mechanisms. But it is still insufficient to conclude that STAT3 is directly participating in DNA damage repair. What's more, these studies are not enough to show that it is ubiquitous for STAT3 to be involved in DNA damage repair. Studies like knocking down STAT3 to test the efficiency of HR or NHEJ are needed in the future.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are a group of cells with characteristics of self-renewing, multipotent, and tumor-initiating. Recently more and more studies showed that most malignant cancer cells were derived from CSCs (92, 93). CSCs have high expression of anti-apoptotic proteins and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) pump, and all these contribute to its chemo- or radio-resistant feature (94–96). Many studies showed that STAT3 was one of the most important factors in maintaining the phenotype of CSCs (97–99). Besides, STAT3 also suppressed differentiation-related genes (100). In the aspect of radiotherapy, recent studies found that STAT3 and CCS were closely connected in contributing to radioresistance. Lee et al. found that STAT3 was involved in enhancing cancer stemness and radioresistant properties (101). Shi et al. showed that ibrutinib, a Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, could impair radioresistance by inactivating STAT3 in glioma stem cells (102). A study by Park et al. showed that JAK2/STAT3/ cyclin D2 (CCND2) pathway promoted colorectal cancer stem cell persistence and radioresistance (103). Gao et al. found that lemonin, a triterpenoid compound, enhanced radiosensitivity by attenuating Stat3-induced cell stemness (104). Many studies have been done to find out the underlying mechanisms of CSCs in radioresistance. A review by Skvortsova et al. showed that the ability of DNA damage repair was enhanced in CSCs, so as to help them defend against ROS (105). Arnold found that radiation expanded cancer stem cell populations and can induce stemness in nonstem cells in a STAT3-dependent manner (106). Since ionizing radiation causes cell death by DNA damage, here we mainly focus on how CSCs respond to DNA damage. Until now, little is known about the DNA repair mechanisms in CSCs. But more and more attention has been paid to the role of ROS in CSC survival and radiation resistance (107).

High ROS levels affect many aspects of tumor biology and one of the most important roles is that it induces DNA damage and genomic instability (108). Normally, single strand breaks (SSBs) are the main DNA damage type after ROS treatment and can be repaired through nucleotide or base excision repair (NER/BER) (109). But the accumulation of SSBs can lead to stalling of the replication fork or error in replication, which ultimately induces more lethal DNA damage type, DSBs. A study showed that CSCs possess lower concentrations of ROS than do non-stem cancer cells (96). Studies also found that inhibiting ROS scavenging machinery could enhance radiosensitivity in CSCs (110, 111). Lu et al. found that niclosamide, an inhibitor of STAT3, increased the radiosensitivity in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells via triggering the production of ROS (112). Their study showed that inhibiting STAT3 and increasing ROS led to radiosensitivity. But they didn't illustrate enough evidence to prove the relationship between STAT3 and ROS in DNA damage repair.

Intracellular ROS is mainly produced by the mitochondria, and another source is NADPH oxidases (NOXs) (113). Initially, mitochondria ROS production is unwanted by cells. Recently, more and more studies found that STAT3 was actively involved in regulating the activity of mitochondria. Lapp et al. found that activating STAT3 decreased mitochondrial ROS production by upregulating the expression of uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) (114). Meier et al. showed that phosphorylation of Ser727 in STAT3 recruited mitochondrially localized STAT3 (115). But phospho-Stat3Y705 is not responsible for the STAT3 mitochondrial translocation (115–117). What's more, a recent study by Cheng et al. found that selectively inhibiting mitochondrial STAT3 could provide a promising target for chemotherapy (118). As a result, we assume that mitochondrial STAT3 may be a potential target in enhancing the radioresensitizing effect of cancer cells. More studies are warranted in the future.

Persistent activation of STAT3 in various tumor types makes STAT3 a specific and promising target in anticancer treatment. Inhibiting STAT3 by STAT3 dominant negative molecules, decoy oligonucleotides, and peptidomimetics is proven efficient in numerous preclinical studies.

STAT3 is well-known for its roles in tumor initiation and development. Besides, STAT3 also leads to chemo- or radio-resistance. In this review, we mainly focused on the role of STAT3 in response to radiotherapy, and the underlying mechanisms including but not limited to apoptosis, aggressive behaviors, DNA damage repair, cancer stem cells were discussed (Supplementary Figure 1). Except for the mechanisms we have discussed above, there are still other explanations for STAT3's role in radioresistance. Hypoxia is also a well-known factor that contributes to radioresistance in many tumor types. Hypoxia induces the production of ROS by mitochondrial electron transport chain. It also activates Hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs), important factors which will induce malignant behaviors and proliferation of tumor cells under hypoxia. Mitochondrial ROS stabilizes HIF1 and HIF2 by inhibiting prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) (119, 120). Studies showed that NSC74859 and stattic, two inhibitors of STAT3, enhanced radiosensitivity by inhibiting hypoxia- and radiation-induced STAT3 activation in esophageal cancer (121, 122).

On the other hand, we have to realize that STAT3 has many other functions except for disease formation and progression, like cardioprotection, liver protection, and obesity (123–126). As a result, targeting STAT3 may have many side effects. For example, strong inhibitors of STAT3 could cause fatigue, diarrhea, infection, and periphery nervous system toxicities (127).

Although the inhibitors of STAT3 have been studied and proven to be efficient in preclinic for 20 years, they showed poor anti-tumor effect in clinical trials (17). Recently, drug repurposing, a method based on the theory that established drugs may have many other mechanisms except for their well-known indications, has gained increased attention (128). Drug repurposing has advantages such as highly approved safety, avoiding laborious and expensive drug development processes. As a result, testing FDA-approved drugs may help us find potential inhibitors of STAT3 and promote its quick translation into clinic to treat human cancers. In conclusion, the role of STAT3 in the radio-response of cancer has been paid more and more attention to. STAT3 is becoming a promising target in the radiosensitization of cancer.

XW, XZ, and NY contributed to conception and manuscript writing. XW and CQ searched the literature. NY supervised the whole writing work. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81702475, 81803045, 81903126), Medical Science Technology Development Program of Shandong Province (2018WS103), and The Jinan Science and Technology Bureau of Shandong Province (201704083).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2020.01120/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1. Radioresistance caused by signaling pathways related to STAT3. Radiation induced anti-apoptosis is mediated by STAT3-HSP70-BCL2 family members pathways. After radiation treatment, STAT3 promoted aggressive behaviors in tumor cells through epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), radiation-induced bystander effect (RIBE) and tumor microenvironment (TM). STAT3 contributes to DNA damage repair through ATM-Chk2 and ATR-Chk1 pathways. Cancer stemness and reactive oxygen species (ROS) depletion are also involved in STAT3-induced radioresistance.

1. Zhang X, Wang J, Li X, Wang D. Lysosomes contribute to radioresistance in cancer. Cancer Lett. (2018) 439:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.08.029

2. Pilie PG, Tang C, Mills GB, Yap TA. State-of-the-art strategies for targeting the DNA damage response in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2018) 16:81–104. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0114-z

3. Branzei D, Foiani M. Regulation of DNA repair throughout the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2008) 9:297–308. doi: 10.1038/nrm2351

4. Czarny P, Pawlowska E, Bialkowska-Warzecha J, Kaarniranta K, Blasiak J. Autophagy in DNA damage response. Int J Mol Sci. (2015) 16:2641–62. doi: 10.3390/ijms16022641

5. Nelson DF, Diener-West M, Horton J, Chang CH, Schoenfeld D, Nelson JS. Combined modality approach to treatment of malignant gliomas–re-evaluation of RTOG 7401/ECOG 1374 with long-term follow-up: a joint study of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. NCI Monogr. (1988) 279–84.

6. Chan JL, Lee SW, Fraass BA, Normolle DP, Greenberg HS, Junck LR, et al. Survival and failure patterns of high-grade gliomas after three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. (2002) 20:1635–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1635

7. Furtek SL, Backos DS, Matheson CJ, Reigan P. Strategies and approaches of targeting STAT3 for cancer treatment. ACS Chem Biol. (2016) 11:308–18. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00945

8. Banerjee K, Resat H. Constitutive activation of STAT3 in breast cancer cells: a review. Int J Cancer. (2016) 138:2570–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29923

9. Yu H, Lee H, Herrmann A, Buettner R, Jove R. Revisiting STAT3 signalling in cancer: new and unexpected biological functions. Nat Rev Cancer. (2014) 14:736–46. doi: 10.1038/nrc3818

10. Bournazou E, Bromberg J. Targeting the tumor microenvironment: JAK-STAT3 signaling. Jak Stat. (2013) 2:e23828. doi: 10.4161/jkst.23828

11. Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat Rev Cancer. (2009) 9:798–809. doi: 10.1038/nrc2734

12. Yu H, Jove R. The STATs of cancer–new molecular targets come of age. Nat Rev Cancer. (2004) 4:97–105. doi: 10.1038/nrc1275

13. Tan FH, Putoczki TL, Stylli SS, Luwor RB. The role of STAT3 signaling in mediating tumor resistance to cancer therapy. Curr Drug Targets. (2014) 15:1341–53. doi: 10.2174/1389450115666141120104146

14. Huang CY, Lin CS, Tai WT, Hsieh CY, Shiau CW, Cheng AL, et al. Sorafenib enhances radiation-induced apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting STAT3. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. (2013) 86:456–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.01.025

15. Huang CY, Tai WT, Hsieh CY, Hsu WM, Lai YJ, Chen LJ, et al. A sorafenib derivative and novel SHP-1 agonist, SC-59, acts synergistically with radiotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through inhibition of STAT3. Cancer Lett. (2014) 349:136–43. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.04.006

16. Lau J, Ilkhanizadeh S, Wang S, Miroshnikova YA, Salvatierra NA, Wong RA, et al. STAT3 blockade inhibits radiation-induced malignant progression in Glioma. Cancer Res. (2015) 75:4302–11. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3331

17. Siveen KS, Sikka S, Surana R, Dai X, Zhang J, Kumar AP, et al. Targeting the STAT3 signaling pathway in cancer: role of synthetic and natural inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2014) 1845:136–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2013.12.005

18. Chipuk JE, Moldoveanu T, Llambi F, Parsons MJ, Green DR. The BCL-2 family reunion. Mol Cell. (2010) 37:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.025

19. Krajewski S, Tanaka S, Takayama S, Schibler MJ, Fenton W, Reed JC. Investigation of the subcellular distribution of the bcl-2 oncoprotein: residence in the nuclear envelope, endoplasmic reticulum, and outer mitochondrial membranes. Cancer Res. (1993) 53:4701–14.

20. Opferman JT, Kothari A. Anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family members in development. Cell Death Differ. (2018) 25:37–45. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.170

21. Fukada T, Hibi M, Yamanaka Y, Takahashi-Tezuka M, Fujitani Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Two signals are necessary for cell proliferation induced by a cytokine receptor gp130: involvement of STAT3 in anti-apoptosis. Immunity. (1996) 5:449–60. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80501-4

22. Epling-Burnette PK, Liu JH, Catlett-Falcone R, Turkson J, Oshiro M, Kothapalli R, et al. Inhibition of STAT3 signaling leads to apoptosis of leukemic large granular lymphocytes and decreased Mcl-1 expression. J Clin Invest. (2001) 107:351–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI9940

23. Daino H, Matsumura I, Takada K, Odajima J, Tanaka H, Ueda S, et al. Induction of apoptosis by extracellular ubiquitin in human hematopoietic cells: possible involvement of STAT3 degradation by proteasome pathway in interleukin 6-dependent hematopoietic cells. Blood. (2000) 95:2577–85. doi: 10.1182/blood.V95.8.2577.008k17_2577_2585

24. Zorzi E, Bonvini P. Inducible hsp70 in the regulation of cancer cell survival: analysis of chaperone induction, expression and activity. Cancers. (2011) 3:3921–56. doi: 10.3390/cancers3043921

25. Whitesell L, Lindquist S. Inhibiting the transcription factor HSF1 as an anticancer strategy. Expert Opin Ther. (2009) 13:469–78. doi: 10.1517/14728220902832697

26. Huang CY, Tai WT, Wu SY, Shih CT, Chen MH, Tsai MH, et al. Dovitinib acts as a novel radiosensitizer in hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting SHP-1/STAT3 signaling. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. (2016) 95:761–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.01.016

27. Bu X, Zhao C, Wang W, Zhang N. GRIM-19 inhibits the STAT3 signaling pathway and sensitizes gastric cancer cells to radiation. Gene. (2013) 512:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.10.057

28. Adachi M, Cui C, Dodge CT, Bhayani MK, Lai SY. Targeting STAT3 inhibits growth and enhances radiosensitivity in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. (2012) 48:1220–6. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.06.006

29. Lee JH, Kim C, Ko JH, Jung YY, Jung SH, Kim E, et al. Casticin inhibits growth and enhances ionizing radiation-induced apoptosis through the suppression of STAT3 signaling cascade. J Cell Biochem. (2019) 120:9787–98. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28259

30. You Y, Wang Q, Li H, Ma Y, Deng Y, Ye Z, et al. Zoledronic acid exhibits radio-sensitizing activity in human pancreatic cancer cells via inactivation of STAT3/NF-kappaB signaling. Onco Targets Ther. (2019) 12:4323–30. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S202516

31. Zhang X, Wang X, Xu R, Ji J, Xu Y, Han M, et al. YM155 decreases radiation-induced invasion and reverses epithelial-mesenchymal transition by targeting STAT3 in glioblastoma. J Transl Med. (2018) 16:79. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1451-5

32. Qin Q, Cheng H, Lu J, Zhan L, Zheng J, Cai J, et al. Small-molecule survivin inhibitor YM155 enhances radiosensitization in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by the abrogation of G2 checkpoint and suppression of homologous recombination repair. J Hematol Oncol. (2014) 7:62. doi: 10.1186/s13045-014-0062-8

33. Sehara Y, Sawicka K, Hwang JY, Latuszek-Barrantes A, Etgen AM, Zukin RS. Survivin Is a transcriptional target of STAT3 critical to estradiol neuroprotection in global ischemia. J Neurosci. (2013) 33:12364–74. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1852-13.2013

34. Chuang YF, Huang SW, Hsu YF, Yu MC, Ou G, Huang WJ, et al. WMJ-8-B, a novel hydroxamate derivative, induces MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell death via the SHP-1-STAT3-survivin cascade. Br J Pharmacol. (2017) 174:2941–61. doi: 10.1111/bph.13929

35. Rauch A, Hennig D, Schafer C, Wirth M, Marx C, Heinzel T, et al. Survivin and YM155: how faithful is the liaison? Biochim Biophys Acta. (2014) 1845:202–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.01.003

36. Chen X, Duan N, Zhang C, Zhang W. Survivin and tumorigenesis: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. J Cancer. (2016) 7:314–23. doi: 10.7150/jca.13332

37. Grdina DJ, Murley JS, Miller RC, Mauceri HJ, Sutton HG, Li JJ, et al. A survivin-associated adaptive response in radiation therapy. Cancer Res. (2013) 73:4418–28. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4640

38. Iwasa T, Okamoto I, Suzuki M, Nakahara T, Yamanaka K, Hatashita E, et al. Radiosensitizing effect of YM155, a novel small-molecule survivin suppressant, in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. (2008) 14:6496–504. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0468

39. Giannini L, Incandela F, Fiore M, Gronchi A, Stacchiotti S, Sangalli C, et al. Radiation-induced sarcoma of the head and neck: a review of the literature. Front Oncol. (2018) 8:449. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00449

40. Wang Y, Song S, Su X, Wu J, Dai Z, Cui D, et al. Radiation-induced glioblastoma with rhabdoid characteristics following treatment for medulloblastoma: a case report and review of the literature. Mol Clin Oncol. (2018) 9:415–8. doi: 10.3892/mco.2018.1703

41. Kegelman TP, Wu B, Das SK, Talukdar S, Beckta JM, Hu B, et al. Inhibition of radiation-induced glioblastoma invasion by genetic and pharmacological targeting of MDA-9/Syntenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2017) 114:370–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616100114

42. Park CM, Park MJ, Kwak HJ, Lee HC, Kim MS, Lee SH, et al. Ionizing radiation enhances matrix metalloproteinase-2 secretion and invasion of glioma cells through Src/epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated p38/Akt and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathways. Cancer Res. (2006) 66:8511–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4340

43. Cui YH, Suh Y, Lee HJ, Yoo KC, Uddin N, Jeong YJ, et al. Radiation promotes invasiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer cells through granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor. Oncogene. (2015) 34:5372–82. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.466

44. Wild-Bode C, Weller M, Rimner A, Dichgans J, Wick W. Sublethal irradiation promotes migration and invasiveness of glioma cells: implications for radiotherapy of human glioblastoma. Cancer Res. (2001) 61:2744–50.

45. Jung CH, Kim EM, Song JY, Park JK, Um HD. Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase 2 mediates gamma-irradiation-induced cancer cell invasion. Exp Mol Med. (2019) 51:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0207-5

46. Vehlow A, Cordes N. Invasion as target for therapy of glioblastoma multiforme. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2013) 1836:236–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2013.07.001

47. Fiveash JB, Spencer SA. Role of radiation therapy and radiosurgery in glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer J. (2003) 9:222–9. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200305000-00010

48. Hay ED. An overview of epithelio-mesenchymal transformation. Acta Anat. (1995) 154:8–20. doi: 10.1159/000147748

49. Yadav A, Kumar B, Datta J, Teknos TN, Kumar P. IL-6 promotes head and neck tumor metastasis by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the JAK-STAT3-SNAIL signaling pathway. Mol Cancer Res. (2011) 9:1658–67. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0271

50. Rokavec M, Oner MG, Li H, Jackstadt R, Jiang L, Lodygin D, et al. IL-6R/STAT3/miR-34a feedback loop promotes EMT-mediated colorectal cancer invasion and metastasis. J Clin Invest. (2014) 124:1853–67. doi: 10.1172/JCI73531

51. Lamouille S, Xu J, Derynck R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2014) 15:178–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm3758

52. Zhou YC, Liu JY, Li J, Zhang J, Xu YQ, Zhang HW, et al. Ionizing radiation promotes migration and invasion of cancer cells through transforming growth factor-beta-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. (2011) 81:1530–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.06.1956

53. Liu W, Huang YJ, Liu C, Yang YY, Liu H, Cui JG, et al. Inhibition of TBK1 attenuates radiation-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition of A549 human lung cancer cells via activation of GSK-3beta and repression of ZEB1. Lab Invest. (2014) 94:362–70. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.153

54. Xuan X, Li S, Lou X, Zheng X, Li Y, Wang F, et al. Stat3 promotes invasion of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma through up-regulation of MMP2. Mol Biol Rep. (2015) 42:907–15. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3828-8

55. Desmarais G, Charest G, Therriault H, Shi M, Fortin D, Bujold R, et al. Infiltration of F98 glioma cells in Fischer rat brain is temporary stimulated by radiation. Int J Rad Biol. (2016) 92:444–50. doi: 10.1080/09553002.2016.1175682

56. Wang SC, Yu CF, Hong JH, Tsai CS, Chiang CS. Radiation therapy-induced tumor invasiveness is associated with SDF-1-regulated macrophage mobilization and vasculogenesis. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e69182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069182

57. Birch JL, Strathdee K, Gilmour L, Vallatos A, McDonald L, Kouzeli A, et al. A novel small-molecule inhibitor of MRCK prevents radiation-driven invasion in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. (2018) 78:6509–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-1697

58. Unbekandt M, Croft DR, Crighton D, Mezna M, McArthur D, McConnell P, et al. A novel small-molecule MRCK inhibitor blocks cancer cell invasion. Cell Commun Signal. (2014) 12:54. doi: 10.1186/s12964-014-0054-x

59. Unbekandt M, Olson MF. The actin-myosin regulatory MRCK kinases: regulation, biological functions and associations with human cancer. J Mol Med. (2014) 92:217–25. doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1133-6

60. Unbekandt M, Belshaw S, Bower J, Clarke M, Cordes J, Crighton D, et al. Discovery of potent and selective MRCK inhibitors with therapeutic effect on skin cancer. Cancer Res. (2018) 78:2096–114. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2870

61. Zhou W, Yu X, Sun S, Zhang X, Yang W, Zhang J, et al. Increased expression of MMP-2 and MMP-9 indicates poor prognosis in glioma recurrence. Biomed Pharmacother. (2019) 118:109369. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109369

62. Yu YC, Yang PM, Chuah QY, Huang YH, Peng CW, Lee YJ, et al. Radiation-induced senescence in securin-deficient cancer cells promotes cell invasion involving the IL-6/STAT3 and PDGF-BB/PDGFR pathways. Sci Rep. (2013) 3:1675. doi: 10.1038/srep01675

63. Peng Y, Zhang M, Zheng L, Liang Q, Li H, Chen JT, et al. Cysteine protease cathepsin B mediates radiation-induced bystander effects. Nature. (2017) 547:458–62. doi: 10.1038/nature23284

64. Prise KM, O'Sullivan JM. Radiation-induced bystander signalling in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. (2009) 9:351–60. doi: 10.1038/nrc2603

65. Rzeszowska-Wolny J, Przybyszewski WM, Widel M. Ionizing radiation-induced bystander effects, potential targets for modulation of radiotherapy. Eur J Pharmacol. (2009) 625:156–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.07.028

66. Duan C, Yang R, Yuan L, Engelbach JA, Tsien CI, Rich KM, et al. Late effects of radiation prime the brain microenvironment for accelerated tumor growth. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. (2018) 103:190–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.08.033

67. Casey SC, Vaccari M, Al-Mulla F, Al-Temaimi R, Amedei A, Barcellos-Hoff MH, et al. The effect of environmental chemicals on the tumor microenvironment. Carcinogenesis. (2015) 36(Suppl. 1):S160–83. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgv035

68. Paget S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. 1889. Cancer Metastasis Rev. (1989) 8:98–101.

69. Fidoamore A, Cristiano L, Antonosante A, d'Angelo M, Di Giacomo E, Astarita C, et al. Glioblastoma stem cells microenvironment: the paracrine roles of the niche in drug and radioresistance. Stem Cells Int. (2016) 2016:6809105. doi: 10.1155/2016/6809105

70. Zhang X, Ding K, Wang J, Li X, Zhao P. Chemoresistance caused by the microenvironment of glioblastoma and the corresponding solutions. Biomed Pharmacother. (2018) 109:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.063

71. Chang Q, Bournazou E, Sansone P, Berishaj M, Gao SP, Daly L, et al. The IL-6/JAK/Stat3 feed-forward loop drives tumorigenesis and metastasis. Neoplasia. (2013) 15:848–62. doi: 10.1593/neo.13706

72. Deng J, Liu Y, Lee H, Herrmann A, Zhang W, Zhang C, et al. S1PR1-STAT3 signaling is crucial for myeloid cell colonization at future metastatic sites. Cancer Cell. (2012) 21:642–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.039

73. Bohrer LR, Chuntova P, Bade LK, Beadnell TC, Leon RP, Brady NJ, et al. Activation of the FGFR-STAT3 pathway in breast cancer cells induces a hyaluronan-rich microenvironment that licenses tumor formation. Cancer Res. (2014) 74:374–86. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2469

74. Jones LM, Broz ML, Ranger JJ, Ozcelik J, Ahn R, Zuo D, et al. STAT3 establishes an immunosuppressive microenvironment during the early stages of breast carcinogenesis to promote tumor growth and metastasis. Cancer Res. (2016) 76:1416–28. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2770

75. Gao C, Kozlowska A, Nechaev S, Li H, Zhang Q, Hossain DM, et al. TLR9 signaling in the tumor microenvironment initiates cancer recurrence after radiotherapy. Cancer Res. (2013) 73:7211–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1314

76. Zhang X, Xu R, Zhang C, Xu Y, Han M, Huang B, et al. Trifluoperazine, a novel autophagy inhibitor, increases radiosensitivity in glioblastoma by impairing homologous recombination. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. (2017) 36:118. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0588-z

77. Campillo-Marcos I, Lazo PA. Olaparib and ionizing radiation trigger a cooperative DNA-damage repair response that is impaired by depletion of the VRK1 chromatin kinase. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. (2019) 38:203. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1204-1

78. Jiang M, Zhao L, Gamez M, Imperiale MJ. Roles of ATM and ATR-mediated DNA damage responses during lytic BK polyomavirus infection. PLoS Pathog. (2012) 8:e1002898. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002898

79. Yan S, Sorrell M, Berman Z. Functional interplay between ATM/ATR-mediated DNA damage response and DNA repair pathways in oxidative stress. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2014) 71:3951–67. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1666-4

80. Zhou BB, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature. (2000) 408:433–9. doi: 10.1038/35044005

81. Zhang J, Willers H, Feng Z, Ghosh JC, Kim S, Weaver DT, et al. Chk2 phosphorylation of BRCA1 regulates DNA double-strand break repair. Mol Cell Biol. (2004) 24:708–18. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.2.708-718.2004

82. Liu Q, Guntuku S, Cui XS, Matsuoka S, Cortez D, Tamai K, et al. Chk1 is an essential kinase that is regulated by Atr and required for the G(2)/M DNA damage checkpoint. Genes Dev. (2000) 14:1448–59. doi: 10.1101/gad.14.12.1448

83. Zhao H, Piwnica-Worms H. ATR-mediated checkpoint pathways regulate phosphorylation and activation of human Chk1. Mol Cell Biol. (2001) 21:4129–39. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.13.4129-4139.2001

84. Zhang D, Tang B, Xie X, Xiao YF, Yang SM, Zhang JW. The interplay between DNA repair and autophagy in cancer therapy. Cancer Biol Therapy. (2015) 16:1005–13. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1046022

85. Gao B, Shen X, Kunos G, Meng Q, Goldberg ID, Rosen EM, et al. Constitutive activation of JAK-STAT3 signaling by BRCA1 in human prostate cancer cells. FEBS Lett. (2001) 488:179–84. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)02430-3

86. Xu F, Li X, Yan L, Yuan N, Fang Y, Cao Y, et al. Autophagy promotes the repair of radiation-induced DNA damage in bone marrow hematopoietic cells via enhanced STAT3 signaling. Rad Res. (2017) 187:382–96. doi: 10.1667/RR14640.1

87. Barry SP, Townsend PA, Knight RA, Scarabelli TM, Latchman DS, Stephanou A. STAT3 modulates the DNA damage response pathway. Int J Exp Pathol. (2010) 91:506–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2010.00734.x

88. Vigneron A, Gamelin E, Coqueret O. The EGFR-STAT3 oncogenic pathway up-regulates the Eme1 endonuclease to reduce DNA damage after topoisomerase I inhibition. Cancer Res. (2008) 68:815–25. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5115

89. Weinandy A, Piroth MD, Goswami A, Nolte K, Sellhaus B, Gerardo-Nava J, et al. Cetuximab induces eme1-mediated DNA repair: a novel mechanism for cetuximab resistance. Neoplasia. (2014) 16:207–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2014.03.004

90. Courapied S, Sellier H, de Carne Trecesson S, Vigneron A, Bernard AC, Gamelin E, et al. The cdk5 kinase regulates the STAT3 transcription factor to prevent DNA damage upon topoisomerase I inhibition. J Biol Chem. (2010) 285:26765–78. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.092304

91. Chen L, Fu L, Kong X, Xu J, Wang Z, Ma X, et al. Jumonji domain-containing protein 2B silencing induces DNA damage response via STAT3 pathway in colorectal cancer. British J Cancer. (2014) 110:1014–26. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.808

92. Pattabiraman DR, Weinberg RA. Tackling the cancer stem cells - what challenges do they pose? Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2014) 13:497–512. doi: 10.1038/nrd4253

93. Chen J, Li Y, Yu TS, McKay RM, Burns DK, Kernie SG, et al. A restricted cell population propagates glioblastoma growth after chemotherapy. Nature. (2012) 488:522–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11287

94. Eyler CE, Rich JN. Survival of the fittest: cancer stem cells in therapeutic resistance and angiogenesis. J Clin Oncol. (2008) 26:2839–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.1829

95. Li X, Lewis MT, Huang J, Gutierrez C, Osborne CK, Wu MF, et al. Intrinsic resistance of tumorigenic breast cancer cells to chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2008) 100:672–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn123

96. Diehn M, Cho RW, Lobo NA, Kalisky T, Dorie MJ, Kulp AN, et al. Association of reactive oxygen species levels and radioresistance in cancer stem cells. Nature. (2009) 458:780–3. doi: 10.1038/nature07733

97. Marotta LL, Almendro V, Marusyk A, Shipitsin M, Schemme J, Walker SR, et al. The JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway is required for growth of CD44(+)CD24(-) stem cell-like breast cancer cells in human tumors. J Clin Invest. (2011) 121:2723–35. doi: 10.1172/JCI44745

98. Schroeder A, Herrmann A, Cherryholmes G, Kowolik C, Buettner R, Pal S, et al. Loss of androgen receptor expression promotes a stem-like cell phenotype in prostate cancer through STAT3 signaling. Cancer Res. (2014) 74:1227–37. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0594

99. Sherry MM, Reeves A, Wu JK, Cochran BH. STAT3 is required for proliferation and maintenance of multipotency in glioblastoma stem cells. Stem Cells. (2009) 27:2383–92. doi: 10.1002/stem.185

100. Carro MS, Lim WK, Alvarez MJ, Bollo RJ, Zhao X, Snyder EY, et al. The transcriptional network for mesenchymal transformation of brain tumours. Nature. (2010) 463:318–25. doi: 10.1038/nature08712

101. Lee JH, Choi SI, Kim RK, Cho EW, Kim IG. Tescalcin/c-Src/IGF1Rbeta-mediated STAT3 activation enhances cancer stemness and radioresistant properties through ALDH1. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:10711. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29142-x

102. Shi Y, Guryanova OA, Zhou W, Liu C, Huang Z, Fang X, et al. Ibrutinib inactivates BMX-STAT3 in glioma stem cells to impair malignant growth and radioresistance. Sci Transl Med. (2018) 10:eaah6816. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aah6816

103. Park SY, Lee CJ, Choi JH, Kim JH, Kim JW, Kim JY, et al. The JAK2/STAT3/CCND2 Axis promotes colorectal Cancer stem cell persistence and radioresistance. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. (2019) 38:399. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1405-7

104. Gao L, Sang JZ, Cao H. Limonin enhances the radiosensitivity of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells via attenuating Stat3-induced cell stemness. Biomed Pharmacother. (2019) 118:109366. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109366

105. Skvortsova I, Debbage P, Kumar V, Skvortsov S. Radiation resistance: cancer stem cells (CSCs) and their enigmatic pro-survival signaling. Semin Cancer Biol. (2015) 35:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.09.009

106. Arnold KM, Opdenaker LM, Flynn NJ, Appeah DK, Sims-Mourtada J. Radiation induces an inflammatory response that results in STAT3-dependent changes in cellular plasticity and radioresistance of breast cancer stem-like cells. Int J Radiat Biol. (2020) 96:434–47. doi: 10.1080/09553002.2020.1705423

107. Ogawa K, Yoshioka Y, Isohashi F, Seo Y, Yoshida K, Yamazaki H. Radiotherapy targeting cancer stem cells: current views and future perspectives. AntiCancer Res. (2013) 33:747–54.

108. Turgeon MO, Perry NJS, Poulogiannis G. DNA damage, repair, and cancer metabolism. Front Oncol. (2018) 8:15. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00015

109. Lindahl T. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature. (1993) 362:709–15. doi: 10.1038/362709a0

110. Sappington DR, Siegel ER, Hiatt G, Desai A, Penney RB, Jamshidi-Parsian A, et al. Glutamine drives glutathione synthesis and contributes to radiation sensitivity of A549 and H460 lung cancer cell lines. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2016) 1860:836–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.01.021

111. Xiang L, Xie G, Liu C, Zhou J, Chen J, Yu S, et al. Knock-down of glutaminase 2 expression decreases glutathione, NADH, and sensitizes cervical cancer to ionizing radiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2013) 1833:2996–3005. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.08.003

112. Lu L, Dong J, Wang L, Xia Q, Zhang D, Kim H, et al. Activation of STAT3 and Bcl-2 and reduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) promote radioresistance in breast cancer and overcome of radioresistance with niclosamide. Oncogene. (2018) 37:5292–304. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0340-y

113. Dan Dunn J, Alvarez LA, Zhang X, Soldati T. Reactive oxygen species and mitochondria: a nexus of cellular homeostasis. Redox Biol. (2015) 6:472–85. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.09.005

114. Lapp DW, Zhang SS, Barnstable CJ. Stat3 mediates LIF-induced protection of astrocytes against toxic ROS by upregulating the UPC2 mRNA pool. Glia. (2014) 62:159–70. doi: 10.1002/glia.22594

115. Meier JA, Hyun M, Cantwell M, Raza A, Mertens C, Raje V, et al. Stress-induced dynamic regulation of mitochondrial STAT3 and its association with cyclophilin D reduce mitochondrial ROS production. Sci Signal. (2017) 10:eaag2588. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aag2588

116. Gough DJ, Corlett A, Schlessinger K, Wegrzyn J, Larner AC, Levy DE. Mitochondrial STAT3 supports Ras-dependent oncogenic transformation. Science. (2009) 324:1713–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1171721

117. Wagner EF, Nebreda AR. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer. (2009) 9:537–49. doi: 10.1038/nrc2694

118. Cheng X, Peuckert C, Wolfl S. Essential role of mitochondrial Stat3 in p38(MAPK) mediated apoptosis under oxidative stress. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:15388. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15342-4

119. Chandel NS, McClintock DS, Feliciano CE, Wood TM, Melendez JA, Rodriguez AM, et al. Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochondrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha during hypoxia: a mechanism of O2 sensing. J Biol Chem. (2000) 275:25130–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001914200

120. Chae YC, Vaira V, Caino MC, Tang HY, Seo JH, Kossenkov AV, et al. Mitochondrial Akt regulation of hypoxic tumor reprogramming. Cancer Cell. (2016) 30:257–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.07.004

121. Zhang C, Yang X, Zhang Q, Guo Q, He J, Qin Q, et al. STAT3 inhibitor NSC74859 radiosensitizes esophageal cancer via the downregulation of HIF-1alpha. Tumour Biol. (2014) 35:9793–9. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2207-3

122. Zhang Q, Zhang C, He J, Guo Q, Hu D, Yang X, et al. STAT3 inhibitor stattic enhances radiosensitivity in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. (2015) 36:2135–42. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2823-y

123. Boengler K, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Drexler H, Heusch G, Schulz R. The myocardial JAK/STAT pathway: from protection to failure. Pharmacol Ther. (2008) 120:172–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.08.002

124. Obana M, Maeda M, Takeda K, Hayama A, Mohri T, Yamashita T, et al. Therapeutic activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 by interleukin-11 ameliorates cardiac fibrosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation. (2010) 121:684–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.893677

125. Mair M, Zollner G, Schneller D, Musteanu M, Fickert P, Gumhold J, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 protects from liver injury and fibrosis in a mouse model of sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. (2010) 138:2499–508. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.049

126. Wang P, Yang FJ, Du H, Guan YF, Xu TY, Xu XW, et al. Involvement of leptin receptor long isoform (LepRb)-STAT3 signaling pathway in brain fat mass- and obesity-associated (FTO) downregulation during energy restriction. Mol Med. (2011) 17:523–32. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.000134

127. Beebe JD, Liu JY, Zhang JT. Two decades of research in discovery of anticancer drugs targeting STAT3, how close are we? Pharmacol Ther. (2018) 191:74–91. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.06.006

Keywords: STAT3, apoptosis, aggressive behaviors, cancer cell stemness, reactive oxygen species

Citation: Wang X, Zhang X, Qiu C and Yang N (2020) STAT3 Contributes to Radioresistance in Cancer. Front. Oncol. 10:1120. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01120

Received: 06 February 2020; Accepted: 04 June 2020;

Published: 07 July 2020.

Edited by:

Carsten Herskind, University of Heidelberg, GermanyReviewed by:

James William Jacobberger, Case Western Reserve University, United StatesCopyright © 2020 Wang, Zhang, Qiu and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ning Yang, eWFuZ25pbmdAc2R1LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.