94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Oncol. , 25 March 2020

Sec. Women's Cancer

Volume 10 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.00361

This article is part of the Research Topic Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer: Current Concepts of Prevention and Treatment View all 7 articles

Every cancer carries genomic mutations. Although almost all these mutations arise after fertilization, a minimal count of cancer predisposition mutations are already present at the time of genesis of germ cells. Of the cancer predisposition genes identified to date, BRCA1 and BRCA2 have been determined to be associated with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Such cancer predisposition genes have recently been attracting attention owing to the emergence of molecular genetics, thus, affecting the strategy of cancer prevention, diagnostics, and therapeutics. In this review, we summarize the molecular significance of these two BRCA genes. First, we provide a brief history of BRCA1 and BRCA2, including their identification as cancer predisposition genes and recognition as members in the Fanconi anemia pathway. Next, we describe the molecular function and interaction of BRCA proteins, and thereafter, describe the patterns of BRCA dysfunction. Subsequently, we present emerging evidence on mutational signatures to determine the effects of BRCA disorders on the mutational process in cancer cells. Currently, BRCA genes serve as principal targets for clinical molecular oncology, be they germline or sporadic mutations. Moreover, comprehensive cancer genome analyses enable us to not only recognize the current status of the known cancer driver gene mutations but also divulge the past mutational processes and predict the future biological behavior of cancer through the molecular trajectory of genomic alterations.

Cancer cells harbor several genetic mutations and epigenetic modifications, which are believed to have arisen from sequential and multistage neoplastic processes (1). However, the mechanism of cellular transformation remains unclear because each oncogenic event is broken down into a molecular reaction, which seems to occur stochastically and independently during oncogenic events in each cancer case. Even if comprehensive genomic data are available, it is still difficult to determine the correct order of genomic alteration.

A possible breakthrough in the understanding of the evolutional process of cancer cells in vivo was provided by studies conducted on the hereditary cancer syndrome, which is due to a germline mutation of the cancer predisposition gene (2, 3). Before the establishment of molecular evidence, clinicians had insights into the familial breast cancer (4). Subsequently, genetic and reverse-genetic research revealed the initial and the following steps in the neoplastic process, which has contributed to novel strategies for cancer prevention, diagnostics, and therapeutics.

The main purpose of this review is to summarize the molecular biology associated with the representative cancer predisposition genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2, and to speculate on the missing link between normal and cancer cells.

Cancer predisposition genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2, were first discovered in the genetic study on familial breast cancer (5) (Table 1). At that time, linkage analyses with DNA polymorphic markers were detecting the causal relationships between certain genetic diseases and specific genomic loci (6). Similarly, a variable number tandem repeat marker known as D17S74, revealed that the candidate familial breast cancer gene is located at chromosome 17q21 (7). Thereafter, this locus, also called the “breast cancer, early onset,” or BRCA1, was indexed for the comprehensive genetic disease database, Mendelian inheritance in Man (MIM), and was given the reference number 113705 (8). After the inter-laboratory competition over 4 years (9), positional cloning of BRCA1 was first achieved using an emerging technique which required the use of bacterial artificial chromosomes (10). In contrast, the second breast cancer predisposition gene, BRCA2, was discovered at chromosome 13q12 by other DNA polymorphic markers, D13S260, and DS13S263 (11), and registered with the MIM number 600185. The discovery of the second breast cancer predisposing gene was followed by the BRCA1 cloning, and subsequently, the race to clone BRCA2 was completed the following year by the same research team (12).

Both BRCA1 and BRCA2 are large genes, which consist of ~100 and 70 kb, respectively; the largest exon of both the BRCA genes is exon 11. Although these genetic features resemble the proof of breast and ovarian cancer predisposing gene family at the first glance, there is no homology between BRCA1 and BRCA2 (13). BRCA1 contains a nuclear localization sequence (NLS) and three functional domains; RING, coiled coil, and BRCT domains interact with the BRCA1-associated RING domain protein (BARD1), the partner and localizer of BRCA2 (PALB2), and several other proteins that include abraxas (ABRA1), CtBP interactive protein (CtIP), and BRCA1-interacting protein C-terminal helicase 1 (BRIP1), respectively (13). These interactions lead to versatile functions of BRCA1: DNA damage sensing, cell cycling regulation, E3 ubiquitin ligase activity, chromatin remodeling, and homologous recombination (HR). In contrast, BRCA2 has NLS, eight BRC repeats (14), and a DNA binding domain. Unlike BRCA1, the functional domains of BRCA2 are principally associated with the HR-related proteins, including RAD51 and deleted in split-hand/split foot protein 1 (DSS1) (15, 16). Therefore, the unique molecular traits of each BRCA protein create a difference between BRCA1- and BRCA2-mutated cancers.

As a common function between BRCA1 and BRCA2, HR is an essential DNA repair system that enables the error-free recovery of double strand breaks (DSBs) (17). DSBs are the most severe DNA damage, the accumulation of which results in genetic translocation and cell death (18). In the condition of homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) by BRCA dysfunction, restoration of DSBs depends on an error-prone repair machinery, known as non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). Such an HRD, also called genomic instability, is advantageous for the progression of BRCA-associated cancer to effectively gain sequence and structural variance, especially in the early phase.

Because BRCA1 and BRCA2 account for ~25% of the familial breast and ovarian cancers (19), this section describes other breast and ovarian cancer predisposition genes. A linkage analysis study revealed that the third candidate hereditary breast cancer gene, BRCA3, was suspected at the BRCA2 neighboring locus, 13q21-22, in intact BRCA1/BRCA2 Nordic cohorts (20); however, the replication study failed to demonstrate the cancer susceptibility (21). These findings suggest that the current genetics-based research has been unable to identify the next cancer predisposition gene or that all BRCA genes have already been found.

Another technique to identify novel breast and ovarian cancer genes is to identify a gene cluster, such as BRCA genes, that play a role in the DNA repair system. Remarkably, HR is related to the Fanconi anemia (FA) pathway, which mediates repair of the interstrand crosslink (ICL) (22). FA is an inherited hematopoietic disorder that gives rise to myelodysplastic syndrome and leukemia. To date, over 20 genes have been identified as FA predisposing genes, and the germline mutation of the FANCA gene accounts for approximately two-thirds of FA cases (23). Most of the FA genes play an important role in the formation of the FA core complex, which binds at the ICL site and then activates the downstream signaling to repair this severely damaged DNA. Finally, the damaged sequence is removed by HR. Therefore, the defective FA pathway leads to cancer predisposition through genetic instability, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 dysfunction.

Considering the functional significance of HR in the FA pathway, BRCA1 and BRCA2 have been refocused as FA susceptibility genes. Of the eight FA genes detected, FANCD1 was identified as BRCA2 (24). In contrast, BRCA1 has been recently recognized as FANCS (25). However, germline mutations of BRCA genes lead to bone marrow failure less frequently than mutations in other FA genes, likely because they are absent from the FA core complex.

Individuals with germline mutations of the FA genes are susceptible not only to hematopoietic but also to solid malignancies. Multiple gene panel studies have revealed that inherited breast and ovarian cancers rarely harbor germline mutations of FA genes, including BRIP1/FANCJ, PALB2/FANCN, and RAD51C/FANCO (26). Based on the latest National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guideline (27), PALB2 is categorized as a gene associated with breast cancer risk, whereas BRIP1 and RAD51C are categorized as genes associated with ovarian cancer risk.

The remaining clinically significant, inherited breast and ovarian cancer genes are the so-called cancer predisposition genes: ATM, CDH1, CHEK2, mismatch repair genes, NBN, NF1, PTEN, RAD51D, STK11, and TP53 (27). Therefore, an investigation of these cancer predisposition genes is effective in detecting the pathogenic allele in the case of the non-BRCA inherited breast and ovarian cancer.

Although numerous germline BRCA mutations, also called sequence variants, have been reported to date, not all the variants lead to predisposition to cancer. Therefore, interpretation of the clinical significance of the detected mutation is a challenge in medical practice. To determine whether the detected sequence variant is pathogenic or not, the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG), together with the Association for Molecular Pathology and the College of American Pathologist, issued the revised universal guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants (28). Based on the evidence of pathogenicity or benignity, this guideline classifies the sequence variants into five categories: pathogenic, likely pathogenic, uncertain significance, likely benign, and benign. In practice, pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants require further medical management, whereas other variants do not require such intervention. Nevertheless, variants of uncertain significance, which are found in up to 20% of BRCA1/BRCA2 genetic tests (29), need follow-up to monitor the manifestation of the true nature of the variants; e.g., variant reclassification programs. The major databases and platforms that contain information on BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants are as follows: BRCA Exchange (30), ClinVar (31), the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD) (32), the Leiden Open Variation Database (LOVD) (33), the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA (CIMBA) (34), and the Evidence-based Network for the Interpretation of Germline Mutant Allele (ENIGMA) (35).

Recently, the international collaboration study conducted by CIMBA clarified different cancer risks related to BRCA genes (36). Consistent with the previous studies (37–39), both BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes contain several cancer risk regions. The ovarian cancer cluster region (OCCR) of both BRCA1 and BRCA2 largely overlaps with exon 11, whereas the breast cancer cluster regions (BCCRs) are located on the exterior of exon 11. The mutation in these cancer cluster regions leads to increased cancer risk of the corresponding organ. Additionally, the mutational type of the BRCA genes also affects the breast and ovarian cancer risk. Collectively, the diversity of the BRCA sequence variants implies not only the general cancer risk but also the specific susceptible organ, and, therefore, the detailed classification of the pathogenic variants would be effective to determine the optimal medical management.

The dysregulation of the BRCA genes arises not only from genetic alternations but also from epigenetic modifications. At the transcriptional level, BRCA1 is regulated by the DNA methylation status at its upstream CpG island (40–42). Consistent with the promoter hypermethylation, BRCA1 is silenced in sporadic breast and ovarian cancer (43, 44). The aberrant BRCA1 promoter methylation is found in approximately one-ninth of ovarian cancer tumors (45–47) and in one-fourth of breast basal-like tumors (48), suggesting that BRCA1 silencing is considered a leading non-genetic case of BRCA1 inactivation in sporadic wild-type BRCA cancer. The comprehensive ovarian cancer genomic studies revealed that hypermethylated-BRCA1 ovarian cancer with platinum therapy had a similar prognosis as the intact BRCA cancer, whereas BRCA1/BRCA2-mutated ovarian cancer showed better prognosis than the wild-type cancer (46, 47). On the other hand, cancer with homologous BRCA1 hypermethylation showed a good response to an emerging therapeutic agent (described in a later section), the PARP inhibitor, which was same as the response of cancer with BRCA germline mutation (49). These evidences suggest that quantitative methylation analysis of BRCA1 promoter would be needed to predict the clinical behavior of hypermethylated BRCA1 cancer.

Conversely, the functional significance of the nearest CpG islands of BRCA2 still remains unclear. Unlike BRCA1, BRCA2 promoter methylation is not considered a leading cause of BRCA2 dysfunction (45–48, 50). However, the specific CpG site methylation is a possible marker of germline BRCA mutations (51). Because functional significance of the aberrant methylation still remains unclear, further investigations would be needed.

Reversion is defined as the secondary mutation of an inherited mutant gene, which restores normal function in somatic cells (52). For example, the pathogenic BRCA allele sometimes reverts to the wild-type sequence via an additional point mutation (back mutation) (53, 54). Conversely, additional insertion/deletion of BRCA genes amends the altered reading frame normally (in-frame mutations), thus, converting it to the non-pathogenic allele. These genetic alterations are considered to be a late stage oncogenic event to reactivate the HR pathway, and it consequently renders the cancer cells resistance to lethal DNA damage. Interestingly, approximately a quarter to half of ovarian cancers with germline BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations exhibit the reversion of the inherited mutation and chemoresistance after chemotherapy (47, 55, 56), suggesting that in vivo retrieval of BRCA function is a potent oncogenic event to resist unwanted DNA damage.

The forthcoming breakthrough in carcinogenesis research is the “mutation signature,” which stands for a unique pattern of genetic alterations in somatic cells. Given that every mutation arises from a specific molecular reaction, the characteristic sets of the genetic alterations are good evidence for mutational processes in cancer cells. This concept enables researchers to convert the vast genomic data on cancer cells into evidence on the current status of cancer-related genes and sheds light on the history of cancer progression.

Owing to the emerging technology, such as next-generation sequencing (57), the first series of comprehensive somatic mutation research successfully demonstrated the close relationship between a certain type of cancer and mutational signatures. Briefly, the melanoma cell line frequently carried C>T and/or CC>TT transition, which is consistent with the effect of ultraviolet light exposure on pyrimidine bases (58). Conversely, the small-cell lung cancer cell line harbored predominantly G>T, G>A, and A>G transitions, which are interpreted as the modification of purine bases by tobacco smoke carcinogens (59). Interestingly, both studies also highlighted the presence of other mutational signatures, suggesting that somatic cells experience multiple mutational processes in vivo.

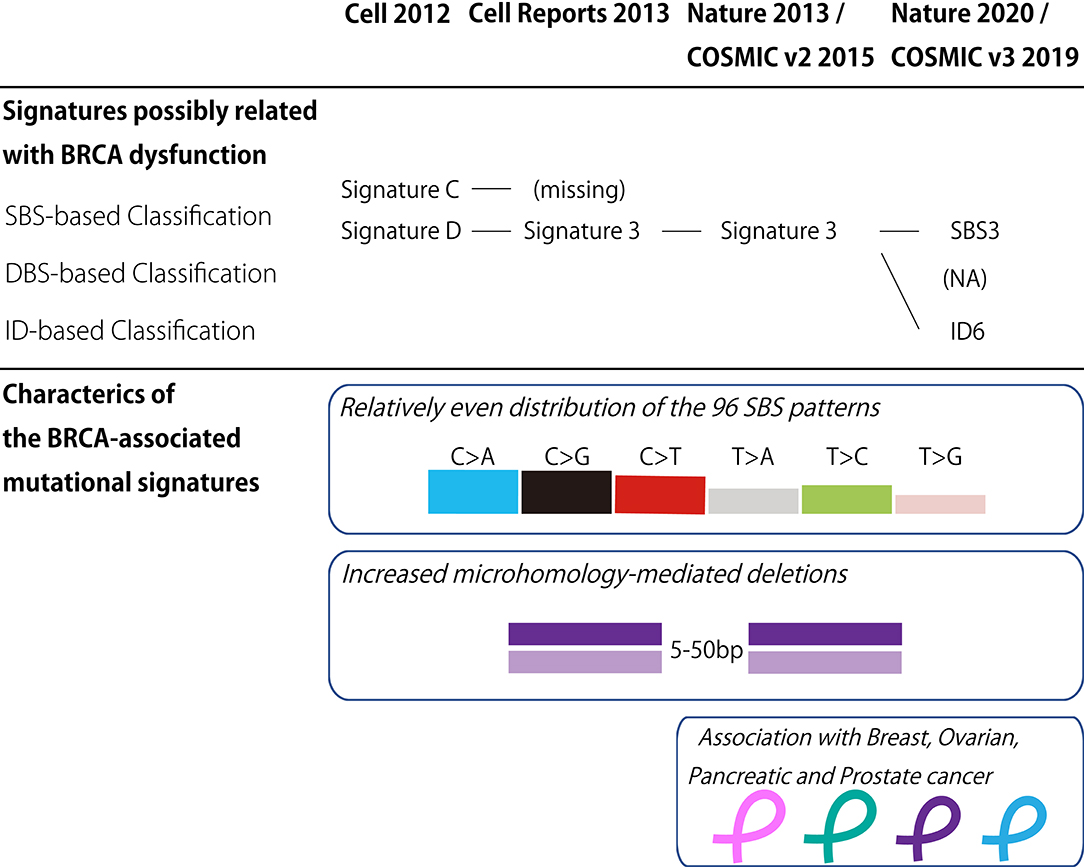

In the last decade, the classification of mutational signatures has rapidly progressed (Figure 1). The classification of mutational signatures was first initiated in a whole-genome study of human breast cancers (60). Owing to the complementation between pyrimidine and purine nucleobases in the double helices, all single base substitutions (also known as point mutations) can be summarized into the following six patterns: C>A/G>T, C>G/G>C, C>T/G>A, T>A/A>T, T>C/A>G, and T>G/A>C transitions. Additionally, to consider the sequence context of the mutated base, these six mutation classes are further subdivided into 96 trinucleotides patterns by referring to the neighboring bases: the 5′- and 3′-base (each base has four types). By analyzing these 96 trinucleotides patterns in 21 different types of breast cancers with mathematical models, five distinctive molecular signatures were extracted. The mutational spectrum of these signatures possibly reflected either aging (spontaneous deamination of 5-methyl-cytosine: Signature A), overexpression of cytidine deaminase belonging to the APOBEC family (Signatures B and E), or BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations (Signatures C and D). Unlike the other mutational signatures, the BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation-associated signatures were unique in regard to the relatively equal distribution of the 96 trinucleotides patterns. Additionally, BRCA1/BRCA2-mutated cancer carried microhomology-mediated deletions more frequently compared with the wild-type cancers. These genomic abnormalities are likely due to the dysfunction of HR when double strand breaks occur. Subsequently, the additional breast cancer genome study failed to reproduce the Signature C-like pattern; thus, the BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation associated Signatures C and D was combined into Signature 3 (61).

Figure 1. BRCA-associated mutational signature. (Upper panel) Classification of the mutational signatures possibly related with BRCA dysfunction. The details of each classification are found in the references 60, 61, 62, and 64. (Lower panel) Characteristics of the BRCA-associated mutational signatures. COSMIC, the Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Cancer; v2, version 2; v3, version 3; SBS, Single base substitution; DBS, Double base substitution; ID, Small insertion and deletion; NA, not applicable.

Thereafter, the international collaborative research group analyzed the large collection of somatic mutations for various cancer types to identify further detailed classes of mutational signatures (62). Although this study identified the 21 distinctive patterns of mutational signatures, the etiology remained unknown for approximately half of the mutational signatures. The mutational signature for BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations, or Signature 3, was reconfirmed in this study, and documented in version 2 of the Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) mutational signatures (63).

To date, the classification of mutational signatures continues to evolve. Version 3 of COSMIC mutational signatures is composed of three conceptual sets: Single Base Substitution (SBS), Double Base Substitution (DBS), and Small Insertion and Deletion (ID) Signatures (64). This detailed scheme sorts the BRCA1/BRCA2-associated mutational signature into SBS and ID. In other words, the relatively equal SBS distribution and microhomology-mediated deletions of Signature 3 are interpreted as SBS3 and ID6, respectively.

The analysis of mutational signatures reveals the DNA damage and repair processes of the cancer genome, which arise from the specific molecular reaction. Given the close relationship between Signature 3 and BRCA mutations, this genome-wide mutational pattern would be applied to the analysis of cancer genome (50, 65). Increased Signature 3 activity was observed not only in the dysfunction of BRCA1 and BRCA2 but also in the inactivation of other HR-related genes, including the PALB2 germline mutation and RAD51C hypermethylation. Remarkably, the increased Signature 3 activity is significantly associated with biallelic mutation, loss of heterozygosity, or epigenetic silencing of the HR-related genes. In contrast, HR-related incomplete inactivation of the gene, e.g., a monoallelic mutation, did not achieve significant Signature 3 enrichment. Therefore, Signature 3 is the circumstantial evidence of HRD, and a good predictor of pathogenic variants of HR-related genes.

The link between BRCA mutations and specific types of cancer has been emerging. The recent TCGA study addressed the molecular classification of gynecologic and breast cancers, and acknowledged the existence of a subset of cancers with BRCA-associated mutational signatures (66). In breast cancer, BRCA1-mutated carcinoma is significantly associated with the basal-like subtype that exhibits negative expression of the estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PGR), and ERBB2/HER2 (67–69). Additionally, BRCA1-mutated and basal-like breast cancer are high grade carcinomas with frequent TP53 mutations (70, 71), indicating that coexisting BRCA1 and TP53 mutations facilitate breast cancer progression. In comparison with BRCA1-mutated cancer, BRCA2-mutated breast carcinomas frequently express ER and PGR; additionally, HER2 is expressed at the same frequency (69). Furthermore, the histological grade of BRCA2-mutated breast carcinoma is generally lower than that of BRCA1-mutated breast carcinoma. Regarding the histological type, lobular carcinoma is typically prevalent in the BRCA2-carriers, whereas medullary carcinoma is more common in BRCA1-carriers.

Lately, in the breast surgical specimens of BRCA-carriers, the dedicated histological examination revealed a distinctive pathologic condition known as “hyaline fibrous involution” (72). Lee et al. reported that hyaline fibrous involution was frequently associated with BRCA-mutated perimenopausal women. This unusual histological finding, including diffuse thickening of the fibrous band in the benign breast lobule, likely arises from the abnormal DNA repair state in non-neoplastic breast epithelium. Although this atrophic-like alteration is a promising premalignant lesion that is rarely found in the benign breast disease, we believe that hyaline fibrous involution is an unexpected chance to suspect inherited cancer in cases without genetical test and clinical history.

Conversely, ovarian cancer among BRCA-carriers tends to be the most frequent histological type; it is a high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) (73). HGSC is a representative type II carcinoma (74), which almost always exhibits high grade nuclear atypia arising from TP53 mutations (46). The prophylactic surgical specimens revealed that the fallopian tube sometimes contained serous intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC) with TP53 mutations even in asymptomatic BRCA-carriers (75, 76). Interestingly, the putative precursor lesion of STIC, or the p53 signature (77), which already carries the TP53 mutation, is also sometimes found in the fallopian tube, regardless of the BRCA genotype. Additionally, the TP53 mutation type of the p53 signature is occasionally discordant with that of HGSC (78). These findings suggest that the functional significance of BRCA mutations is the promotion of neoplastic cells rather than the initiation of minute precursors. Additionally, they suggest that inherited ovarian cancer is most probably an inherited “tubal” cancer, on the basis of the tubal origin theory of HGSC (79).

Notably, HGSC with BRCA dysregulations, including BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations and BRCA1 promoter hypermethylation, are associated with specific morphological “SET” patterns: Solid, pseudoEndometrioid, and Transitional cell carcinoma-like histology (80, 81). Recognition of the SET variant is in line with the recent diagnostic concept for ovarian carcinoma; there are five major histological types that reflect unique molecular characteristics and precursor lesions, and mixed-type ovarian carcinoma accounts for a rare fraction of ovarian epithelial malignancies (82). Although ovarian transitional cell carcinoma was a distinct entity (83), this malignant tumor was incorporated into HGSC in the World Health Organization 2014 classification because of the similarity of the molecular characteristics between the two carcinomas (84). Importantly, SET-type HGSC shows good therapeutic response compared to the conventional-type HGSC, likely due to the HRD arising from BRCA dysregulation. Thus, the SET pattern is a diagnostic and therapeutic predictor for HGSC; therefore, pathological examination still remains important in the era of molecular oncology.

Another possible genetic-pathologic correlation between clear cell carcinoma (CCC) and BRCA2 mutations (85, 86) seems contradictory to the findings of other research groups (87, 88). Because CCC is a type I carcinoma that originates from endometriosis-related cysts or lesions (74), the pathogenesis of CCC is generally unrelated to the above-mentioned high-grade serous carcinogenesis. Nevertheless, three mixed CCC and HGSC cases were reported based on immunohistochemical and genetic analyses (82). The two of the three mixed CCC and HGSC cases were true combined type I and II carcinomas, whereas the remaining case was pure HGSC. These findings suggest that CCC and HGSC might arise from the common precursor cells or that CCC is sometimes misinterpreted as a HGSC by histological assessment only. Therefore, further data are needed to confirm this ovarian genetic-pathologic correlation.

In addition to breast and ovarian cancers, pancreatic and prostate cancers rarely harbor BRCA mutations (89, 90) and BRCA-associated signatures (62, 64). The clinical sequence studies reveal that the germline BRCA2 mutation is detected in ~5% of metastatic prostate carcinoma cases (91–93). Histologically, BRCA2-mutated prostate carcinoma is associated with high grade histology (94, 95), including ductal (96) and endocrine (97, 98) differentiation. On the other hand, pancreatic cancer also harbors BRCA2 mutations. Of the common types of cancer, including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and neuroendocrine tumors (PanNET), ~4 and 1% of PDAC and PanNET possess germline BRCA2 mutations, respectively (99, 100). These findings suggest that mutated BRCA2-carriers should exercise caution regarding the development of extra-mammary and uterine adnexal cancers.

Because breast and ovarian cancer predisposition genes were identified, the principal strategy of hereditary cancer management involves the early detection of cancer by frequent medical checks, including mammogram, breast MRI, transvaginal ultrasound, and serum CA-125 test, frequently referred to as surveillance. In some cases, this entails the surgical removal of the susceptible organs, if deemed medically necessary. Traditionally, pathogenic BRCA-carriers require a prophylactic surgery to prevent breast and/or ovarian cancer even in their reproductive age (101). The resected breasts and uterine adnexa contain premalignant lesions and/or microscopic carcinomas (102, 103), which imply the presence of candidates for future malignancy. Indeed, BRCA-carriers sometimes suffer from contralateral breast cancer after the first breast cancer. Therefore, bilateral mastectomy is effective to prevent multiple and hererochronous cancer. In addition, in a recent study, it was revealed that oophorectomy slightly assisted in decreasing contralateral breast cancer (104).

Recent molecular and clinical evidence endorses molecular therapy for BRCA-mutated cancer. As described previously, BRCA-mutated cancer generally exhibits high-grade histology and aggressive phenotypes but responds favorably to platinum-containing chemotherapy (105–108). Such platinum sensitivity is probably due to BRCA-associated HRD that fails to recover platinum-induced ICL (109).

A novel molecular treatment using poly (ADP–ribose) polymerase (PARP)-inhibitor is also based on HRD in the BRCA-mutated cancer cells. PARP1 is a cardinal DNA repair molecule in the case of single strand breaks (SSB) (110). Inhibition of PARP1 results in the occurrence of DSBs, which is the failure of the replication fork through SSB repair (111, 112), as well as the disturbance of the NHEJ repair pathway, by blocking the chromatin remodeler known as CHD2 (113). Together, PARP1 inhibitor and HRD accumulate the critical DSB damage in the BRCA-mutated cancer cells. Consistent with the results of these in vitro studies, PARP inhibitors have the effect of suppressing the BRCA-mutated cancer regardless of the cancer type (114–117). Currently, clinical use of these promising drugs has been approved by the FDA (118). In the future, genetic testing of the BRCA mutation would be necessary to determine the optimal therapeutic plan for individuals with advanced cancer.

As the molecular functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2 have been elucidated, the clinical focus on these cancer predisposition genes shifts toward the development of therapeutic strategies. Additionally, comprehensive cancer genome analysis illustrates not only the present status of cancer related genes but also the past and ongoing mutational processes arising from specific molecular reactions. In the future, the prospective biological behavior of cancer will be predicted via the molecular trajectory of genomic alteration.

YH contributed to the conception of the work and wrote the manuscript. MT, MM, and AH contributed to the revisions of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the submitted manuscript.

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP18K15207.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr, Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. (2013) 339:1546–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122

3. Rahman N. Realizing the promise of cancer predisposition genes. Nature. (2014) 505:302–8. doi: 10.1038/nature12981

4. Papadrianos E, Haagensen CD, Cooley E. Cancer of the breast as a familial disease. Ann Surg. (1967) 165:10–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196701000-00002

5. Narod SA, Foulkes WD. BRCA1 and BRCA2: 1994 and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. (2004) 4:665–76. doi: 10.1038/nrc1431

6. Nakamura Y, Leppert M, O'Connell P, Wolff R, Holm T, Culver M, et al. Variable number of tandem repeat (VNTR) markers for human gene mapping. Science. (1987) 235:1616–22. doi: 10.1126/science.3029872

7. Hall JM, Lee MK, Newman B, Morrow JE, Anderson LA, Huey B, et al. Linkage of early-onset familial breast cancer to chromosome 17q21. Science. (1990) 250:1684–9. doi: 10.1126/science.2270482

8. McKusick VA. Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Catalogs of Autosomal Dominant, Autosomal Recessive and X-Linked Phenotypes. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press (1992).

10. Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal PA, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. (1994) 266:66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954

11. Wooster R, Neuhausen SL, Mangion J, Quirk Y, Ford D, Collins N, et al. Localization of a breast cancer susceptibility gene, BRCA2, to chromosome 13q12-13. Science. (1994) 265:2088–90. doi: 10.1126/science.8091231

12. Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, Swift S, Seal S, Mangion J, et al. Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature. (1995) 378:789–92. doi: 10.1038/378789a0

13. Roy R, Chun J, Powell SN. BRCA1 and BRCA2: different roles in a common pathway of genome protection. Nat Rev Cancer. (2011) 12:68–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc3181

14. Bork P, Blomberg N, Nilges M. Internal repeats in the BRCA2 protein sequence. Nat Genet. (1996) 13:22–3. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-22

15. Suwaki N, Klare K, Tarsounas M. RAD51 paralogs: roles in DNA damage signalling, recombinational repair and tumorigenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. (2011) 22:898–905. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.07.019

16. Yang H, Jeffrey PD, Miller J, Kinnucan E, Sun Y, Thoma NH, et al. BRCA2 function in DNA binding and recombination from a BRCA2-DSS1-ssDNA structure. Science. (2002) 297:1837–48. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5588.1837

17. Zhang H, Tombline G, Weber BL. BRCA1, BRCA2, and DNA damage response: collision or collusion? Cell. (1998) 92:433–6. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80936-8

18. Byrum AK, Vindigni A, Mosammaparast N. Defining and modulating ‘BRCAness'. Trends Cell Biol. (2019) 29:740–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2019.06.005

19. Nielsen FC, van Overeem Hansen T, Sorensen CS. Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: new genes in confined pathways. Nat Rev Cancer. (2016) 16:599–612. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.72

20. Kainu T, Juo SH, Desper R, Schaffer AA, Gillanders E, Rozenblum E, et al. Somatic deletions in hereditary breast cancers implicate 13q21 as a putative novel breast cancer susceptibility locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2000) 97:9603–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9603

21. Thompson D, Szabo CI, Mangion J, Oldenburg RA, Odefrey F, Seal S, et al. Evaluation of linkage of breast cancer to the putative BRCA3 locus on chromosome 13q21 in 128 multiple case families from the breast cancer linkage consortium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2002) 99:827–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012584499

22. Katsuki Y, Takata M. Defects in homologous recombination repair behind the human diseases: FA and HBOC. Endocr Relat Cancer. (2016) 23:T19–37. doi: 10.1530/ERC-16-0221

23. Nepal M, Che R, Zhang J, Ma C, Fei P. Fanconi anemia signaling and cancer. Trends Cancer. (2017) 3:840–56. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.10.005

24. Howlett NG, Taniguchi T, Olson S, Cox B, Waisfisz Q, de Die-Smulders C, et al. Biallelic inactivation of BRCA2 in Fanconi anemia. Science. (2002) 297:606–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1073834

25. Sawyer SL, Tian L, Kahkonen M, Schwartzentruber J, Kircher M, University of Washington Centre for Mendelian Genomics, et al. Biallelic mutations in BRCA1 cause a new Fanconi anemia subtype. Cancer Discov. (2015) 5:135–42. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-1156

26. Catana A, Apostu AP, Antemie RG. Multi gene panel testing for hereditary breast cancer - is it ready to be used? Med Pharm Rep. (2019) 92:220–5. doi: 10.15386/mpr-1083

27. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2019 Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian. (2019) Available online at: https://www.nccn.org/ (accessed March 31, 2019).

28. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet Med. (2015) 17:405–23. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30

29. Eccles DM, Mitchell G, Monteiro AN, Schmutzler R, Couch FJ, Spurdle AB, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing-pitfalls and recommendations for managing variants of uncertain clinical significance. Ann Oncol. (2015) 26:2057–65. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv278

30. Cline MS, Liao RG, Parsons MT, Paten B, Alquaddoomi F, Antoniou A, et al. BRCA Challenge: BRCA exchange as a global resource for variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2. PLoS Genet. (2018) 14:e1007752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007752

31. Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Riley GR, Jang W, Rubinstein WS, Church DM, et al. ClinVar: public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. (2014) 42:D980–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1113

32. Stenson PD, Mort M, Ball EV, Evans K, Hayden M, Heywood S, et al. The human gene mutation database: towards a comprehensive repository of inherited mutation data for medical research, genetic diagnosis and next-generation sequencing studies. Hum Genet. (2017) 136:665–77. doi: 10.1007/s00439-017-1779-6

33. Fokkema IF, Taschner PE, Schaafsma GC, Celli J, Laros JF, den Dunnen JT. LOVD v.2.0: the next generation in gene variant databases. Hum Mutat. (2011) 32:557–63. doi: 10.1002/humu.21438

34. Chenevix-Trench G, Milne RL, Antoniou AC, Couch FJ, Easton DF, Goldgar DE, et al. An international initiative to identify genetic modifiers of cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the consortium of investigators of modifiers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 (CIMBA). Breast Cancer Res. (2007) 9:104. doi: 10.1186/bcr1670

35. Spurdle AB, Healey S, Devereau A, Hogervorst FB, Monteiro AN, Nathanson KL, et al. ENIGMA–evidence-based network for the interpretation of germline mutant alleles: an international initiative to evaluate risk and clinical significance associated with sequence variation in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Hum Mutat. (2012) 33:2–7. doi: 10.1002/humu.21628

36. Rebbeck TR, Mitra N, Wan F, Sinilnikova OM, Healey S, McGuffog L, et al. Association of type and location of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with risk of breast and ovarian cancer. JAMA. (2015) 313:1347–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5985

37. Gayther SA, Warren W, Mazoyer S, Russell PA, Harrington PA, Chiano M, et al. Germline mutations of the BRCA1 gene in breast and ovarian cancer families provide evidence for a genotype-phenotype correlation. Nat Genet. (1995) 11:428–33. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-428

38. Gayther SA, Mangion J, Russell P, Seal S, Barfoot R, Ponder BA, et al. Variation of risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with different germline mutations of the BRCA2 gene. Nat Genet. (1997) 15:103–5. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-103

39. Thompson D, Easton D, Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Variation in BRCA1 cancer risks by mutation position. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2002) 11:329–36. Available online at: https://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/11/4/329

40. Mancini DN, Rodenhiser DI, Ainsworth PJ, O'Malley FP, Singh SM, Xing W, et al. CpG methylation within the 5' regulatory region of the BRCA1 gene is tumor specific and includes a putative CREB binding site. Oncogene. (1998) 16:1161–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201630

41. Rice JC, Massey-Brown KS, Futscher BW. Aberrant methylation of the BRCA1 CpG island promoter is associated with decreased BRCA1 mRNA in sporadic breast cancer cells. Oncogene. (1998) 17:1807–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202086

42. Veeck J, Ropero S, Setien F, Gonzalez-Suarez E, Osorio A, Benitez J, et al. BRCA1 CpG island hypermethylation predicts sensitivity to poly(adenosine diphosphate)-ribose polymerase inhibitors. J Clin Oncol. (2010) 28:e563–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1010

43. Catteau A, Harris WH, Xu CF, Solomon E. Methylation of the BRCA1 promoter region in sporadic breast and ovarian cancer: correlation with disease characteristics. Oncogene. (1999) 18:1957–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202509

44. Esteller M, Silva JM, Dominguez G, Bonilla F, Matias-Guiu X, Lerma E, et al. Promoter hypermethylation and BRCA1 inactivation in sporadic breast and ovarian tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2000) 92:564–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.7.564

45. Turner N, Tutt A, Ashworth A. Hallmarks of 'BRCAness' in sporadic cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. (2004) 4:814–9. doi: 10.1038/nrc1457

46. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. (2011) 474:609–15. doi: 10.1038/nature10166

47. Patch AM, Christie EL, Etemadmoghadam D, Garsed DW, George J, Fereday S, et al. Whole-genome characterization of chemoresistant ovarian cancer. Nature. (2015) 521:489–94. doi: 10.1038/nature14410

48. Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. (2012) 490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412

49. Kondrashova O, Topp M, Nesic K, Lieschke E, Ho GY, Harrell MI, et al. Methylation of all BRCA1 copies predicts response to the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in ovarian carcinoma. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:3970. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05564-z

50. Polak P, Kim J, Braunstein LZ, Karlic R, Haradhavala NJ, Tiao G, et al. A mutational signature reveals alterations underlying deficient homologous recombination repair in breast cancer. Nat Genet. (2017) 49:1476–86. doi: 10.1038/ng.3934

51. Vos S, van Diest PJ, Moelans CB. A systematic review on the frequency of BRCA promoter methylation in breast and ovarian carcinomas of BRCA germline mutation carriers: mutually exclusive, or not? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. (2018) 127:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.05.008

52. Hirschhorn R. In vivo reversion to normal of inherited mutations in humans. J Med Genet. (2003) 40:721–8. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.10.721

53. Swisher EM, Sakai W, Karlan BY, Wurz K, Urban N, Taniguchi T. Secondary BRCA1 mutations in BRCA1-mutated ovarian carcinomas with platinum resistance. Cancer Res. (2008) 68:2581–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0088

54. Sakai W, Swisher EM, Karlan BY, Agarwal MK, Higgins J, Friedman C, et al. Secondary mutations as a mechanism of cisplatin resistance in BRCA2-mutated cancers. Nature. (2008) 451:1116–20. doi: 10.1038/nature06633

55. Kondrashova O, Nguyen M, Shield-Artin K, Tinker AV, Teng NNH, Harrell MI, et al. Secondary somatic mutations restoring RAD51C and RAD51D associated with acquired resistance to the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in high-grade ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Discov. (2017) 7:984–98. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0419

56. Norquist B, Wurz KA, Pennil CC, Garcia R, Gross J, Sakai W, et al. Secondary somatic mutations restoring BRCA1/2 predict chemotherapy resistance in hereditary ovarian carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. (2011) 29:3008–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.2980

57. Levy SE, Myers RM. Advancements in next-generation sequencing. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. (2016) 17:95–115. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-083115-022413

58. Pleasance ED, Cheetham RK, Stephens PJ, McBride DJ, Humphray SJ, Greenman CD, et al. A comprehensive catalogue of somatic mutations from a human cancer genome. Nature. (2010) 463:191–6. doi: 10.1038/nature08658

59. Pleasance ED, Stephens PJ, O'Meara S, McBride DJ, Meynert A, Jones D, et al. A small-cell lung cancer genome with complex signatures of tobacco exposure. Nature. (2010) 463:184–90. doi: 10.1038/nature08629

60. Nik-Zainal S, Alexandrov LB, Wedge DC, van Loo P, Greenman CD, Raine K, et al. Mutational processes molding the genomes of 21 breast cancers. Cell. (2012) 149:979–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.024

61. Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Campbell PJ, Stratton MR. Deciphering signatures of mutational processes operative in human cancer. Cell Rep. (2013) 3:246–59. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.12.008

62. Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SA, Behjati S, Biankin AV, et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. (2013) 500:415–21. doi: 10.1038/nature12477

63. Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, Sondka Z, Beare DM, Bindal N, et al. COSMIC: the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. (2019) 47:D941–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1015

64. Alexandrov LB, Kim J, Haradhvala NJ, Huang MN, Ng AWT, Wu Y, et al. The repertoire of mutational signatures in human cancer. Nature. (2020) 578:94–101. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1943-3

65. Davies H, Glodzik D, Morganella S, Yates LR, Staaf J, Zou X, et al. HRDetect is a predictor of BRCA1 and BRCA2 deficiency based on mutational signatures. Nat Med. (2017) 23:517–25. doi: 10.1038/nm.4292

66. Berger AC, Korkut A, Kanchi RS, Hegde AM, Lenoir W, Liu W, et al. A comprehensive pan-cancer molecular study of gynecologic and breast cancers. Cancer Cell. (2018) 33:690–705. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.014

67. Sorlie T, Tibshirani R, Parker J, Hastie T, Marron JS, Nobel A, et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2003) 100:8418–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932692100

68. Foulkes WD, Stefansson IM, Chappuis PO, Begin LR, Goffin JR, Wong N, et al. Germline BRCA1 mutations and a basal epithelial phenotype in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2003) 95:1482–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg050

69. Mavaddat N, Barrowdale D, Andrulis IL, Domchek SM, Eccles D, Nevanlinna H, et al. Pathology of breast and ovarian cancers among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from the consortium of investigators of modifiers of BRCA1/2 (CIMBA). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2012) 21:134–47. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0775

70. Manie E, Vincent-Salomon A, Lehmann-Che J, Pierron G, Turpin E, Warcoin M, et al. High frequency of TP53 mutation in BRCA1 and sporadic basal-like carcinomas but not in BRCA1 luminal breast tumors. Cancer Res. (2009) 69:663–71. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1560

71. Holstege H, Horlings HM, Velds A, Langerød A, Børresen-Dale AL, van de Vijver MJ, et al. BRCA1-mutated and basal-like breast cancers have similar aCGH profiles and a high incidence of protein truncating TP53 mutations. BMC Cancer. (2010) 10:654. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-654

72. Lee HE, Arshad M, Brahmbhatt RD, Hoskin TL, Winham SJ, Frost MH, et al. Hyaline fibrous involution of breast lobules: a histologic finding associated with germline BRCA mutation. Mod Pathol. (2019) 32:1263–70. doi: 10.1038/s41379-019-0217-9

73. Hatano Y, Hatano K, Tamada M, Morishige KI, Tomita H, Yanai H, et al. A comprehensive review of ovarian serous carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol. (2019) 26:329–39. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000243

74. Kurman RJ, Shih IM. The dualistic model of ovarian carcinogenesis: revisited, revised, and expanded. Am J Pathol. (2016) 186:733–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.11.011

75. Piek JM, van Diest PJ, Zweemer RP, Jansen JW, Poort-Keesom RJ, Menko FH, et al. Dysplastic changes in prophylactically removed Fallopian tubes of women predisposed to developing ovarian cancer. J Pathol. (2001) 195:451–6. doi: 10.1002/path.1000

76. Carcangiu ML, Radice P, Manoukian S, Spatti G, Gobbo M, Pensotti V, et al. Atypical epithelial proliferation in fallopian tubes in prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy specimens from BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutation carriers. Int J Gynecol Pathol. (2004) 23:35–40. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000101082.35393.84

77. Lee Y, Miron A, Drapkin R, Nucci MR, Medeiros F, Saleemuddin A, et al. A candidate precursor to serous carcinoma that originates in the distal fallopian tube. J Pathol. (2007) 211:26–35. doi: 10.1002/path.2091

78. Hatano Y, Fukuda S, Makino H, Tomita H, Morishige KI, Hara A. High-grade serous carcinoma with discordant p53 signature: report of a case with new insight regarding high-grade serous carcinogenesis. Diagn Pathol. (2018) 13:24. doi: 10.1186/s13000-018-0702-3

79. Soong TR, Howitt BE, Miron A, Horowitz NS, Campbell F, Feltmate CM, et al. Evidence for lineage continuity between early serous proliferations (ESPs) in the Fallopian tube and disseminated high-grade serous carcinomas. J Pathol. (2018) 246:344–51. doi: 10.1002/path.5145

80. Soslow RA, Han G, Park KJ, Garg K, Olvera N, Spriggs DR, et al. Morphologic patterns associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 genotype in ovarian carcinoma. Mod Pathol. (2012) 25:625–36. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.183

81. Howitt BE, Hanamornroongruang S, Lin DI, Conner JE, Schulte S, Horowitz N, et al. Evidence for a dualistic model of high-grade serous carcinoma: BRCA mutation status, histology, and tubal intraepithelial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. (2015) 39:287–93. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000369

82. Mackenzie R, Talhouk A, Eshragh S, Lau S, Cheung D, Chow C, et al. Morphologic and molecular characteristics of mixed epithelial ovarian cancers. Am J Surg Pathol. (2015) 39:1548–57. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000476

83. Austin RM, Norris HJ. Malignant Brenner tumor and transitional cell carcinoma of the ovary: a comparison. Int J Gynecol Pathol. (1987) 6:29–39. doi: 10.1097/00004347-198703000-00004

84. Hatano Y, Tamada M, Asano N, Hayasaki Y, Tomita H, Morishige KI, et al. High-grade serous ovarian carcinoma with mucinous differentiation: report of a rare and unique case suggesting transition from the “SET” feature of high-grade serous carcinoma to the “STEM” feature. Diagn Pathol. (2019) 14:4. doi: 10.1186/s13000-019-0781-9

85. Takahashi H, Chiu HC, Bandera CA, Behbakht K, Liu PC, Couch FJ, et al. Mutations of the BRCA2 gene in ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Res. (1996) 56:2738–41.

86. Goodheart MJ, Rose SL, Hattermann-Zogg M, Smith BJ, de Young BR, Buller RE. BRCA2 alteration is important in clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Clin Genet. (2009) 76:161–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01207.x

87. Press JZ, de Luca A, Boyd N, Young S, Troussard A, Ridge Y, et al. Ovarian carcinomas with genetic and epigenetic BRCA1 loss have distinct molecular abnormalities. BMC Cancer. (2008) 8:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-17

88. Norquist BM, Harrell MI, Brady MF, Walsh T, Lee MK, Gulsuner S, et al. Inherited mutations in women with ovarian carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. (2016) 2:482–90. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5495

89. van Asperen CJ, Brohet RM, Meijers-Heijboer EJ, Hoogerbrugge N, Verhoef S, Vasen HF, et al. Cancer risks in BRCA2 families: estimates for sites other than breast and ovary. J Med Genet. (2005) 42:711–9. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.028829

90. Mersch J, Jackson MA, Park M, Nebgen D, Peterson SK, Singletary C, et al. Cancers associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations other than breast and ovarian. Cancer. (2015) 121:269–75. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29041

91. Robinson D, van Allen EM, Wu YM, Schultz N, Lonigro RJ, Mosquera JM, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. (2015) 161:1215–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.001

92. Pritchard CC, Mateo J, Walsh MF, de Sarkar N, Abida W, Beltran H, et al. Inherited DNA-repair gene mutations in men with metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. (2016) 375:443–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603144

93. Annala M, Struss WJ, Warner EW, Beja K, Vandekerkhove G, Wong A, et al. Treatment outcomes and tumor loss of heterozygosity in germline DNA repair-deficient prostate cancer. Eur Urol. (2017) 72:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.02.023

94. Gallagher DJ, Gaudet MM, Pal P, Kirchhoff T, Balistreri L, Vora K, et al. Germline BRCA mutations denote a clinicopathologic subset of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. (2010) 16:2115–21. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2871

95. Na R, Zheng SL, Han M, Yu H, Jiang D, Shah S, et al. Germline mutations in ATM and BRCA1/2 distinguish risk for lethal and indolent prostate cancer and are associated with early age at death. Eur Urol. (2017) 71:740–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.11.033

96. Risbridger GP, Taylor RA, Clouston D, Sliwinski A, Thorne H, Hunter S, et al. Patient-derived xenografts reveal that intraductal carcinoma of the prostate is a prominent pathology in BRCA2 mutation carriers with prostate cancer and correlates with poor prognosis. Eur Urol. (2015) 67:496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.08.007

97. Beltran H, Prandi D, Mosquera JM, Benelli M, Puca L, Cyrta J, et al. Divergent clonal evolution of castration-resistant neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Nat Med. (2016) 22:298–305. doi: 10.1038/nm.4045

98. Chedgy EC, Vandekerkhove G, Herberts C, Annala M, Donoghue AJ, Sigouros M, et al. Biallelic tumour suppressor loss and DNA repair defects in de novo small-cell prostate carcinoma. J Pathol. (2018) 246:244–53. doi: 10.1002/path.5137

99. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. (2017) 32:185–203.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.07.007

100. Scarpa A, Chang DK, Nones K, Corbo V, Patch AM, Bailey P, et al. Whole-genome landscape of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Nature. (2017) 543:65–71. doi: 10.1038/nature21063

101. Hartmann LC, Lindor NM. The role of risk-reducing surgery in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. (2016) 374:454–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1503523

102. Hoogerbrugge N, Bult P, de Widt-Levert LM, Beex LV, Kiemeney LA, Ligtenberg MJ, et al. High prevalence of premalignant lesions in prophylactically removed breasts from women at hereditary risk for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2003) 21:41–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.137

103. Powell CB, Kenley E, Chen LM, Crawford B, McLennan J, Zaloudek C, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA mutation carriers: role of serial sectioning in the detection of occult malignancy. J Clin Oncol. (2005) 23:127–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.109

104. Kotsopoulos J, Lubinski J, Lynch HT, Tung N, Armel S, Senter L, et al. Oophorectomy and risk of contralateral breast cancer among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2019) 175:443–9. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05162-7

105. Byrski T, Gronwald J, Huzarski T, Grzybowska E, Budryk M, Stawicka M, et al. Pathologic complete response rates in young women with BRCA1-positive breast cancers after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. (2010) 28:375–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7019

106. Golan T, Kanji ZS, Epelbaum R, Devaud N, Dagan E, Holter S, et al. Overall survival and clinical characteristics of pancreatic cancer in BRCA mutation carriers. Br J Cancer. (2014) 111:1132–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.418

107. Cheng HH, Pritchard CC, Boyd T, Nelson PS, Montgomery B. Biallelic inactivation of BRCA2 in platinum-sensitive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. (2016) 69:992–5. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.11.022

108. Mylavarapu S, Das A, Roy M. Role of BRCA mutations in the modulation of response to platinum therapy. Front Oncol. (2018) 8:16. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00016

109. Deans AJ, West SC. DNA interstrand crosslink repair and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. (2011) 11:467–80. doi: 10.1038/nrc3088

110. Gupte R, Liu Z, Kraus WL. PARPs and ADP-ribosylation: recent advances linking molecular functions to biological outcomes. Genes Dev. (2017) 31:101–26. doi: 10.1101/gad.291518.116

111. Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. (2005) 434:913–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03443

112. Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. (2005) 434:917–21. doi: 10.1038/nature03445

113. Luijsterburg MS, de Krijger I, Wiegant WW, Shah RG, Smeenk G, de Groot AJL, et al. PARP1 links CHD2-mediated chromatin expansion and H3.3 deposition to DNA repair by non-homologous end-joining. Mol Cell. (2016) 61:547–62. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.01.019

114. Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, Miranda S, Mossop H, Perez-Lopez R, et al. DNA-repair defects and olaparib in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. (2015) 373:1697–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506859

115. Lyons TG, Robson ME. Resurrection of PARP inhibitors in breast cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. (2018) 16:1150–6. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.7031

116. Friedlander M, Gebski V, Gibbs E, Davies L, Bloomfield R, Hilpert F, et al. Health-related quality of life and patient-centred outcomes with olaparib maintenance after chemotherapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT Ov-21): a placebo-controlled, phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. (2018) 19:1126–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30343-7

117. Golan T, Hammel P, Reni M, van Cutsem E, Macarulla T, Hall MJ, et al. Maintenance olaparib for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. (2019) 381:317–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903387

Keywords: breast, ovary, pancreas, prostate, BRCA1, BRCA2, cancer predisposition gene, mutational signature

Citation: Hatano Y, Tamada M, Matsuo M and Hara A (2020) Molecular Trajectory of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations. Front. Oncol. 10:361. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00361

Received: 06 December 2019; Accepted: 02 March 2020;

Published: 25 March 2020.

Edited by:

Anne Grabenstetter, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Nicole Williams, The Ohio State University, United StatesCopyright © 2020 Hatano, Tamada, Matsuo and Hara. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuichiro Hatano, eXVoYUBnaWZ1LXUuYWMuanA=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.