- 1Department of Oncology, University of Torino Medical School, Turin, Italy

- 2Candiolo Cancer Institute, FPO-IRCCS, Turin, Italy

Tumors driven by mutant KRAS are among the most aggressive and refractory to treatment. Unfortunately, despite the efforts, targeting alterations of this GTPase, either directly or by acting on the downstream signaling cascades, has been, so far, largely unsuccessful. However, recently, novel therapeutic opportunities are emerging based on the effect that this oncogenic lesion exerts in rewiring the cancer cell metabolism. Cancer cells that become dependent on KRAS-driven metabolic adaptations are sensitive to the inhibition of these metabolic routes, revealing novel therapeutic windows of intervention. In general, mutant KRAS fosters tumor growth by shifting cancer cell metabolism toward anabolic pathways. Depending on the tumor, KRAS-driven metabolic rewiring occurs by up-regulating rate-limiting enzymes involved in amino acid, fatty acid, or nucleotide biosynthesis, and by stimulating scavenging pathways such as macropinocytosis and autophagy, which, in turn, provide building blocks to the anabolic routes, also maintaining the energy levels and the cell redox potential (1). This review will discuss the most recent findings on mutant KRAS metabolic reliance in tumor models of pancreatic and non-small-cell lung cancer, also highlighting the role that these metabolic adaptations play in resistance to target therapy. The effects of constitutive KRAS activation in glycolysis elevation, amino acids metabolism reprogramming, fatty acid turnover, and nucleotide biosynthesis will be discussed also in the context of different genetic landscapes.

Introduction

KRAS mutations can promote all the key aspects of cancer cell metabolism. It elevates glucose, glutamine and fatty acids uptake and consumption to sustain biosynthetic pathways and the cell redox potential. All these functions are regulated by a number of events, here summarized in three major points, that cooperate with mutant Kras in metabolic reprogramming and specify metabolic adaptation in different tumor types.

(i) Similarly to other oncogenic lesions (2), the effect of KRAS mutations in metabolic adaptation can differ in distinct tumor types depending on the tissue of origin. This has been revealed by comparing the metabolic adaptations of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) driven by Kras mutations and Trp53 deletion in mice. These two cancer types, despite sharing the same genetic alteration, use branched-chain amino acids differently. While NSCLCs incorporate free branched-chain amino acids into tissue protein and use them as nitrogen source, uptake of these amino acids and expression of key enzymes responsible for their catabolism are decreased in PDACs (3).

(ii) Cancer cells carrying mutant Kras crosstalk with the microenvironment, exchanging cytokines, growth factors, and metabolites to improve metabolic adaptation and overcome low nutrients availability (4–6).

(iii) Finally, a number of concomitant genetic alterations have been shown to cooperate with KRAS mutations in sustaining specific metabolic adaptations (7–10).

In this framework, the purpose of this review is to discuss the most recent findings on the interplay between Kras and metabolism focusing on metabolic dependencies of mutant Kras-driven lung and pancreatic cancers that could be attractive as therapeutic targets.

Mutant KRAS and Glucose Metabolism

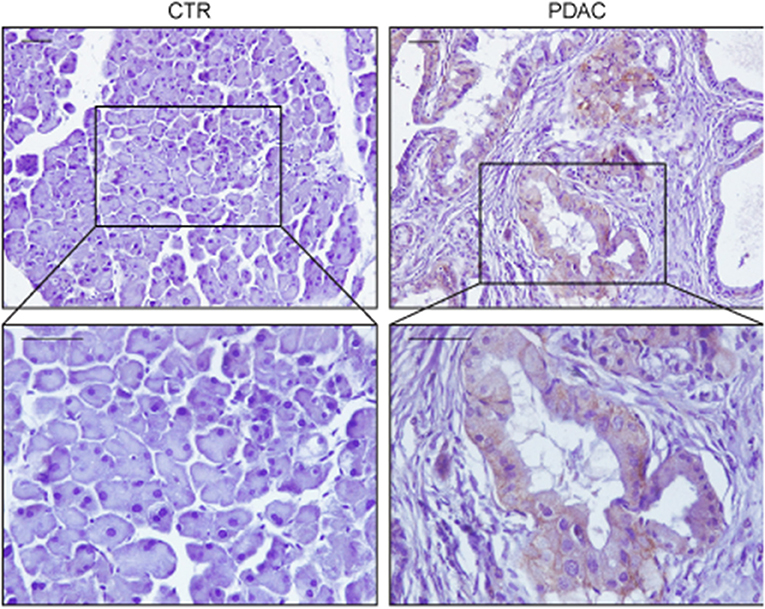

The involvement of the Ras oncogene in metabolic reprogramming has been initially revealed by its ability to promote glycolysis (11). In pancreatic cancer, KRAS mutations are an early event being detectable in the initial lesions known as pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias (PanIN), which can progress in infiltrating ductal carcinomas through the acquisition of additional genetic alterations (12). In mouse models, PanIN lesions rapidly evolve in aggressive PDACs when Kras mutations are combined with Trp53 loss (13). Elevation of glycolysis is a distinguishing feature of Kras-driven tumorigenesis. Indeed, in the Kras mutant NSCLC model, inhibition of increased lactate production, which results from high rates of glycolysis, severely impacts on disease progression (14). Moreover, increased expression of the facilitative glucose transporter GLUT1, which fosters glycolysis by increasing glucose uptake (15), can be invariably detected in Kras mutant pancreatic lesions (16, 17) (Figure 1). The major outcome of increased glycolysis is the generation of intermediates that can be used as building blocks by other metabolic routes to synthetize nucleotides, amino acids, and fatty acids which are required by the rapidly dividing cells to generate the tumor mass (20). Indeed, elevation of glycolysis by Kras channels glucose intermediates in the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) and in the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (21). Using a KrasG12D inducible PDAC murine model (also carrying deletion of p53), abrogation of KrasG12D expression causes tumor regression that is accompanied by severe reduction of the expression of GLUT1 and rate-limiting glycolytic enzymes, and of the amount of glycolytic intermediates as revealed by both metabolomics and transcriptomic studies (21). These metabolites fuel the non-oxidative arm of PPP whose primary function is to produce the nucleotide precursor ribose-5-phosphate. Mechanistically, activation of MAPK by Kras up-regulates Myc-directed transcription. In turn, this increases the expression of the glycolytic enzymes that promote glucose uptake and consumption, and of the PPP enzyme RPIA. RPIA catalyzes the conversion of ribose-5-phosphate in ribulose-5-phosphate, thus fueling nucleotides biosynthesis (21, 22). In agreement, inhibition of PPP suppresses xenograft tumor growth indicating that mutant Kras, by increasing glucose uptake and consumption, sustains biosynthetic pathways leading to nucleotide production finally maintaining tumor growth (21). Interestingly, nucleosides supplementation can rescue cell death caused by Kras knockdown in mutant Kras-addicted PDAC cell lines without promoting cell proliferation suggesting that the metabolic function of Kras can be uncoupled from its functions in proliferation (22).

Figure 1. Representative immunohistochemistry stainings of GLUT1 in sections of pancreas from a wild type mouse (CTR) or from a mouse expressing KrasG12V in the acinar/centroacinar lineages (Elas-tTA/tetOFF-Cre;K-Ras+/LSL G12V Geo) (18). GLUT1 is up-regulated specifically in most tumor cells, with mixed membranous/intracellular localization. In each case pancreas was formalin fixed, paraffin embedded and slices were processed as described in Pupo et al. (19). Briefly, paraffin removal was performed with two 10 min steps in Xylene, rehydrated in decreasing concentration of ethanol, and antigen retrieval was performed using 2100 Antigen Retriever/R-Universal buffer (Aptum Biologics). Slices were permeabilized with 0.2% TritonX, saturated in 5% goat serum/BSA and endogenous peroxidase was inhibited by H2O2 incubation. Staining was performed with anti-GLUT1 antibody (AbCam, 1:200) and secondary antibody anti-Rabbit-HRP (Dako). Immunoreactivity was developed using DAB chromogen (Dako). Scale bars are 50 μm.

The genetic landscape of the tumor cooperates with KRAS mutations in the elevation of glycolysis to promote cancer growth and dissemination. In pancreatic cancer, overexpression of paraoxonase 2 (PON2), a target of p53 transcriptional repression, has been found to join forces with mutant Kras to elevate glycolysis. PON2 increases glucose uptake by binding to GLUT1 thus preventing interaction of the latter with the inhibitory protein STOM (7). PON2 overexpression controls the cell starvation response and increases glucose uptake to protect pancreatic cancer cells from detachment-induced cell death, which, in part, occurs through suppression of the AMPK/FOXO3A/PUMA signaling pathway (7). AMPK is a highly conserved kinase that works as a sensor of low cellular energy and that can either repress or promote tumor growth depending on tumor type and context (23). Here, pharmacological activation of the AMPK pathway inhibits growth of tumors generated by subcutaneous injection of PDAC cancer cells revealing a potential metabolic druggable vulnerability (7).

Scavenging Pathways and Amino Acid Metabolism in KRAS Mutant Cancer Cells

KRAS mutations are known to stimulate processes such as macropinocytosis and autophagy that can scavenge nutrients from, respectively, external and internal compartments to sustain cancer cell survival under condition of nutrient deprivation [reviewed in Kimmelman (1)]. Both these two scavenging pathways generate vesicles, macropinosomes, and autophagosomes, which ultimately fuse with lysosomes to release their cargoes for degradation. In the lysosomes, breakdown of nutrients provides the cell with pools of free amino acids, lipids, nucleotides and glucose that can be used by the anabolic pathways for synthetizing novel macromolecules (1, 24). Interestingly, both in Kras mutant lung and pancreatic cancers, the lysosomal compartment undergoes expansion thanks to the increased activity of the transcription factors Tfeb/Tfe3 (25, 26), which are responsible for lysosomal biogenesis (27, 28). In Kras-driven NSCLC, glucose starvation activates AMPK that promotes dephosphorylation and nuclear translocation of Tfeb and Tfe3 (25). Accordingly, Tfe3 activity is required for growth of mouse lung tumors and increased expression of lysosomal genes correlates with accelerated disease recurrence in human lung adenocarcinoma patients (25). Similarly, upregulation and increased nuclear residence of Tfe3 sustain pancreatic tumor growth (26). Of note, overexpression of Mitf, which belongs to this family of transcription factors, promotes progression of Kras mutant PanIN lesions in PDAC indicating that increased lysosomal activity plays a driver function in mutant Kras tumors (26).

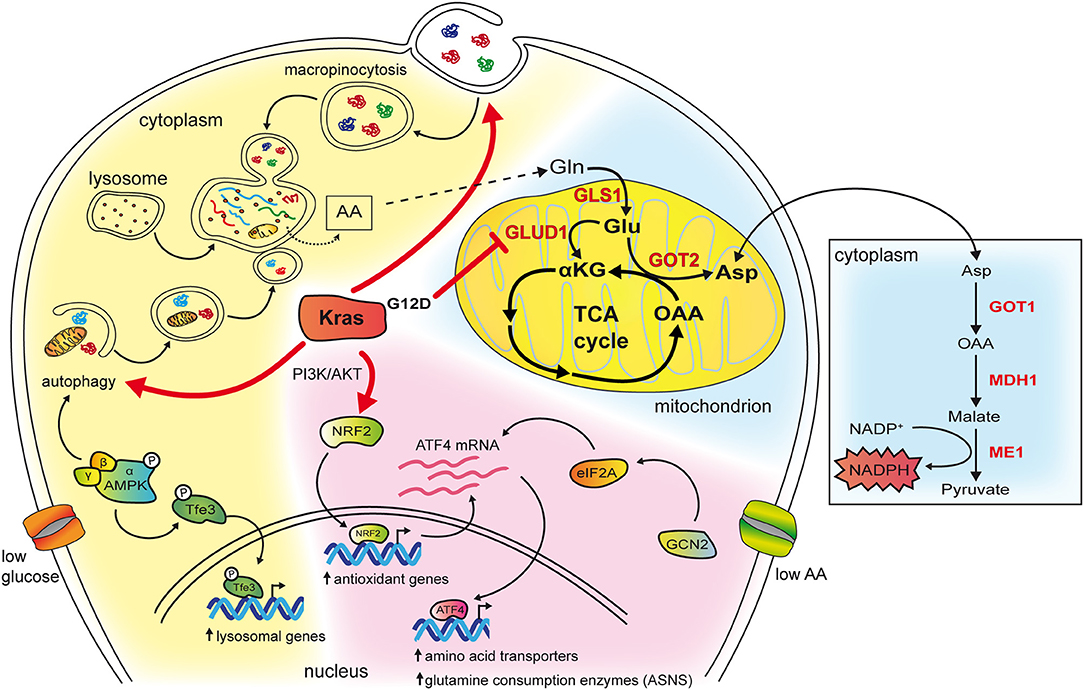

Macropinocytosis is a non-selective actin-dependent endocytic process that uptakes nutrients from the extracellular environment in large intracytoplasmatic vesicles (29). In tumors, macropinocytosis works as a feeding mechanism to overcome high nutrients demand and support metabolic flexibility and adaptation. KRAS mutations have been shown to stimulate macropinocytosis allowing for large uptake of albumin, the most abundant serum protein, which is degraded in lysosomes to increase the intracellular pool of amino acids (30, 31). Breakdown of albumin provides amino acids that feed the central carbon metabolism (30) and, among them, glutamine, is avidly used by Kras transformed cells for anaplerosis and nucleotide production (30, 32) (Figure 2). Indeed, in Kras mutant pancreatic cancer cells, glutamine is the major carbon source and is consumed via a non-canonical pathway. In the majority of non-transformed cells, in mitochondria, glutamine-derived glutamate is converted, by the enzyme glutamate dehydrogenase (GLUD1), in α-ketoglutarate to fuel the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. Instead, in PDAC cells, glutamate is used by the mitochondrial aspartate transaminase GOT2 to produce aspartate and α-ketoglutarate. Aspartate is transported in the cytoplasm where it is converted to oxaloacetate, by the aspartate transaminase GOT1, then into malate and pyruvate thus elevating the NADPH/NADP+ ratio, which, in turn, sustains the cell redox potential (33) (Figure 2). In agreement, genetic deletion of any enzyme in the pathway elevates production of reactive oxygen species, diminishes the amount of reduced glutathione, and results in suppression of PDAC growth both in vitro and in vivo (33). Kras drives the alternative glutamine consumption pathway by up regulating transcription of GOT1 and reducing expression of GLUD1. While this pathway is essential for PDAC growth, it seems to be dispensable in non-transformed cells. This offers a therapeutic option to this type of tumors also considering that its inhibition might synergize with therapies that increase intracellular reactive oxygen species such as chemotherapy and radiation (33). Along this line, Kras mutant cells that have become resistant to cisplatin, a compound that works by increasing the reactive oxygen species in the cytoplasm, display elevation of glutamine consumption and anti-oxidant capacity (34). Knock down of GOT1 in the resistant cells reduces their proliferation suggesting that Kras-mediated metabolic reprogramming of glutamine consumption contributes to the acquired resistance to platinum-based drugs (34).

Figure 2. The cartoon schematizes some of the effects of mutant Kras in reprogramming amino acid metabolism. The cytoplasm of the cell has been colored in blue in the background to highlight the role of mutant Kras in PDAC, in pink to represent pathways revealed in NSCLC, in yellow when the mechanisms are common to both tumor types. Kras potentiates both macropinocytosis and autophagy whose vesicles end up in lysosomes, a compartment that is frequently found enlarged in Kras mutant cancer cells. In, NSCLC, in condition of low glucose, this occurs by activating AMPK that phosphorylates Tfe3 resulting in its nuclear translocation and transcription of lysosomal genes. Moreover, AMPK activation increases autophagy initiation and maturation. Breakdown of macromolecules in lysosomes produce free amino acids available to biosynthetic and energy pathways. Among them glutamine can enter the TCA cycle in mitochondria (depicted on the right). In PDAC glutamine is consumed through an alternative pathway (highlighted in red and in the box on the right). In NSCLC, mutant Kras activates the PI3K/AKT pathway that, in condition of low glutamine, favors mRNA expression of the ATF4 transcription factor via the NRF2 factor. In addition, NRF2 is also a key regulator of genes involved in the antioxidant response. Under condition of asparagine deprivation, the GCN2-eIF2 pathway prompts transduction of the ATF4 mRNA into protein, which, in turn, activates the transcription of amino acids transporters and glutamine consuming enzymes. Among them, asparagine synthetase ASNS catalyzes the synthesis of asparagine from glutamine. Asparagine levels and ASNS control proliferation, mTORC1 activation and suppress apoptosis.

The role of Kras in detoxification is also reported in advanced lung cancer, where high frequency of KrasG12D copy gain is observed. This enrichment in mutant alleles promote channeling of glucose-derived metabolites in the TCA cycle and glutathione biosynthesis enhancing the management of reactive oxygen species and increasing the metastatic potential (35). It is of note that upregulation of glutathione is specifically associated with increased mutant gene copy number highlighting a “dose” effect and suggesting therapeutic vulnerability (35).

Macroautophagy (here referred as autophagy) promotes survival under metabolic stress conditions by directing intracellular components to lysosomes via the formation of vesicles known as autophagosomes (24). Even if autophagy does not increment the biomass, as it re-utilizes pre-existing molecules to generate new ones, it supports cell survival under stress condition allowing tumor persistence (36). Autophagy is known to sustain several aspects of Ras transformation, from maintenance of the cell glycolytic capacity (37), of the mitochondrial oxidative metabolism (38), of energy charge and nucleotide pool (39), to the secretion of pro-migratory cytokines (40). Autophagy has complex functions in cancer, being both pro-tumorigenic and tumor suppressive (24), but increasing evidence in mouse models of pancreatic cancer indicates that, especially at later stages of tumorigenesis, autophagy sustains tumor growth [reviewed in Amaravadi and Debnath (41)]. Indeed, pancreatic deletion of the autophagy gene Atg5 in a model of pancreatic cancer driven by oncogenic Kras and the stochastic loss of heterozygosity of Trp53 (KrasG12D; Trp53lox/+), a condition that reproduces the stepwise human development of pancreatic cancer, increases the number of PanIN lesions, but impairs the progression of PanIN to PDAC, prolonging mice survival (42). Moreover, inhibition of autophagy by treatment with hydroxycloroquine causes tumor reduction in KRAS mutant TP53 mutant patients-derived pancreatic cancer xenografts (42). In addition, the effects of intermittent autophagy inhibition, which would mimic patients treatment, have been recently tested using an inducible transgenic PDAC mouse model generated by crossing mice carrying the inducible dominant-negative mutant of the autophagic gene Atg4B with the KrasG12D; Trp53lox/+, mice. In these animals, metronomic impairment of autophagy has been found to delay tumor growth via both cell autonomous, by decreasing proliferation and sensitizing apoptosis in nutrient-restricted areas of the tumor, and non-autonomous, macrophage-mediated, mechanisms (5).

Notably, two recent studies have shown that autophagy inhibition synergizes with pharmacological targeting of the KRAS downstream effectors MEK1/2 or ERK, preventing growth of KRAS-driven pancreatic adenocarcinomas (43, 44). The efficacy of combining these two treatments appears to rely on the fact that inhibition of the MAPK pathway, one of the major pathways downstream KRAS, potentiates autophagy, suggesting that this treatment causes addiction to autophagy. Concomitant treatment with MAPK and autophagy inhibitors might therefore represent a novel strategy to target KRAS-driven cancers (43, 44).

The ability of mutant Kras to model the microenvironment is a long standing observation in PDACs where abrogation of KrasG12D expression, not only affects tumor growth, but also reduces the desmoplastic stroma, which is typical of this type of cancer (18). In PDACs, mutant Kras instructs the microenvironment to sustain tumor growth both by engaging stromal cells that instigate reciprocal signaling (4), and by exploiting stroma-derived alternative fuels (6). This latter function relies on the stroma-associated pancreatic stellate cells that, following stimulation by the cancer cells, activate autophagy and secrete their breakdown products mainly consisting of non-essential amino acids. Among them, alanine, the second most abundant amino acid in proteins, is up-taken by the cancer cells and used as carbon source to run the TCA cycle, and to synthetize other non-essential amino acids and lipids (6).

The role of Kras in mediating the nutrient stress response to reduced amino acid availability has been recently elucidated in NSCLC. Gene expression profiles of lung cancer cell lines with different genetic background have been analyzed in presence of high or low glutamine concentrations with or without concomitant Kras knockdown, to identify a set of genes that are differentially regulated by Kras signaling in response to glutamine availability (45). In low glutamine, Kras regulates over 100 genes. Among them, 39 are controlled by the transcription factor ATF4. Kras increases the expression of ATF4 mRNA through PI3K-AKT-mediated upregulation of the NRF2 transcription factor, which drives the expression of a number of genes mainly involved in the antioxidant response [reviewed in Sullivan et al. (46)]. During nutrient deprivation, activation of the GCN2-p-eIF2 pathway stimulates translation of the ATF4 mRNA, resulting in increased ATF4 protein levels and transcription of target genes responsible for amino acids uptake and metabolism thus regulating cell proliferation and mTORC1 activation (45). Among the ATF4 targets, the enzyme asparagine synthetase (ASNS), which transfers the γ amino group of glutamine to aspartate, yielding asparagine and glutamate, uncovers a key role because it contributes to apoptotic suppression, protein biosynthesis and mTORC1 activation. Consistently, inhibition of AKT impairs Kras-dependent activation of ASNS therefore sensitizing NSCLC tumors to depletion of extracellular asparagine (45). Overall these findings identify KRAS as a master regulator of the transcriptional response to nutrient deprivation that controls amino acids uptake and consumption (schematized in Figure 2). ATF4 has been shown to exert both pro- and anti-oncogenic effects depending on the genetic context and nutrient availability (45). In condition of low glutamine, ATF4 has a protective role toward apoptosis in Kras mutant NSCLC cell lines that carry loss of KEAP1 (45), a deletion that, in humans, affects approximately 20% of Kras-mutant lung adenocarcinomas (8). Keap1 is a ubiquitin ligase that causes degradation of NRF2 [reviewed in Sullivan et al. (46)]. Its loss cooperates with KRAS mutations in lung adenocarcinoma progression by opposing to the oxidative stress barriers during tumorigenesis (8). Of note, Kras mutant Keap1 deficient cancers are dependent on the glutamine anaplerotic pathway as their growth rate in mice is reduced by pharmacological inhibition of the enzyme glutaminase. This suggests that increased NRF2 activation in Kras mutant lung cancer might be exploited as a stratification tool to identify patients that benefit from glutaminase inhibition (8).

In NSCLC, KRAS mutations are often accompanied by loss of the tumor suppressor STK11, which encodes the LKB1 kinase, leading to the formation of aggressive tumors characterized by perturbed nitrogen handling (9). LKB1, through AMPK, suppresses transcription of CPS1, (carbamoyl phosphate synthetase-1), a mitochondrial enzyme that catalyzes the rate-limiting step of the urea cycle. In non-pathological settings, expression of CPS1 is restricted to the liver where robust urea production from ammonia takes place (47). In NSCLC cells bearing both mutant Kras and LKB1 loss, expression of CPS1 produces carbamoyl phosphate in the mitochondria from ammonia and bicarbonate, initiating pyrimidine synthesis (9). Depletion of CPS1 in these cells results in pyrimidine depletion, replication fork stalling and DNA damage finally reducing their ability to grow tumors. Interestingly, wild type Kras cells carrying LKB1 loss express CPS1, but do not depend on it. Thus oncogenic Kras is required to generate CPS1 “addiction.” This addiction might result from the ability of mutant Kras to increase glutaminolysis in mitochondria (33) thus locally generating ammonia that would support carbamoyl phosphate production by CPS1 (9).

Mutant KRAS in Lipid Metabolism

Lipid metabolism, in particular the synthesis of fatty acids, is required for membrane biosynthesis, signaling molecules production and energy storage (48). Recently, it is also emerging as a mechanism to cope with oncogenic stress (49). Mutant Kras has been shown to control both β-oxidation and de novo lipogenesis in NSCLC (49, 50). The role of mutant Kras in fatty acid oxidation has been reported in a transgenic mouse model that expresses the (doxy)-inducible Kras transgene (KrasG12D) in the respiratory epithelium (49). These mice, when fed with doxy, develop lung tumors that completely regress when doxycycline is removed with concomitant significant decrease in the expression of enzymes that control glycolysis and lipid metabolism (49). Among the latters, Acyl-coenzyme A synthetase long chain family member 3 and 4 (Acsl3 and Acsl4) are significantly down regulated in tumors undergoing KrasG12D extinction and Acsl3 seems to contribute the most to the oncogenic phenotype both in vitro and in vivo (49). Acsl3 promotes uptake, retention, and β-oxidation of fatty acids converting them into Acyl-CoA esters. Genetic deletion of Acsl3 in mice does not cause any morphological defects neither during development nor adult life, but impairs mutant Kras tumorigenesis. Acsl3 silencing has likely similar effects as fatty acid synthase pharmacological inhibition opening to new possible therapeutic strategies in NSCLS (49).

The role of Kras in lipogenesis is highlighted by the upregulation of enzymes that control fatty acid metabolism such as ATP citrate lyase, fatty acid synthase and acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase in the KrasG12D lung cancer model (50). Overexpression of both ATP citrate lyase and fatty acid synthase correlates with poor survival and with increased lipogenesis as shown by the higher levels of newly synthetized palmitate and oleate (48, 50).

As for other metabolic adaptations, KRAS mutations work synergistically with additional genetic alterations in reprogramming lipid metabolism. In PDAC arising from intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMNs), KRAS mutations are associated to a gain of function mutation on the gene GNAS (GNASR201C) which encodes Gαs, the stimulatory subunit of heterotrimeric G proteins (10). GNAS mediates G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR)-stimulated cAMP signaling, and its mutation has been identified in different tumor types (10). In double mutant mice carrying inducible GnasR201C expression and KrasG12D mutation, GnasR201C promotes IPMN initiation and sustains tumor formation. Mechanistically, using tumor-derived organoids, GnasR201C has been found to support pancreatic cancer growth via cAMP-PKA signaling that suppresses the salt-inducible kinases (SIKs) (10). Proteomics reveals that this pathway is overall correlated with lipid metabolism and with components of the peroxisome, an organelle required for long-chain fatty acids processing and the generation of ether lipids suggesting that concurrent GNAS and KRAS mutations cooperate in lipid metabolism rewiring (10).

Conclusions

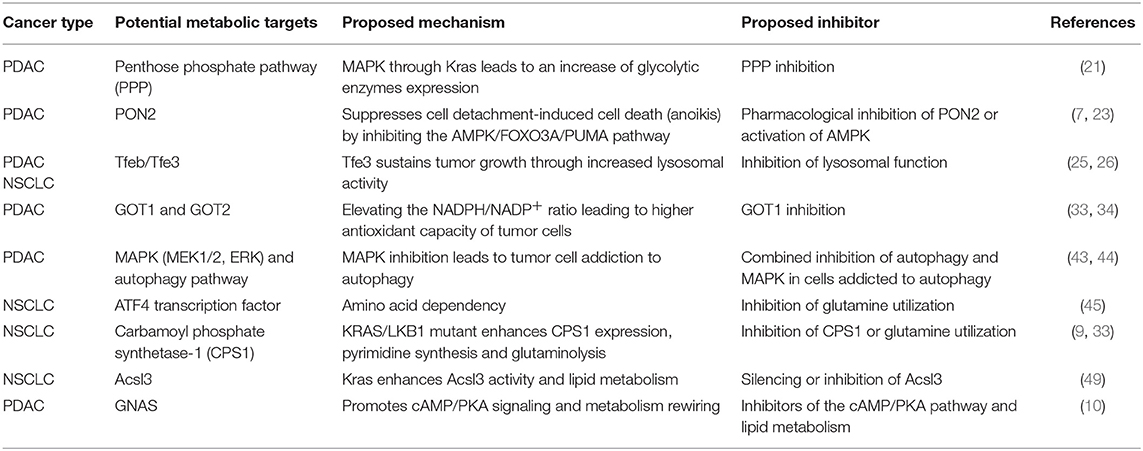

Studies on the role of mutant Kras in rewiring cancer cell metabolism are blooming and the approaches to exploit Kras-driven metabolic vulnerabilities that stem from these findings hold promises, at least in pre-clinical settings, as we summarized in Table 1. A take home message is that metabolic interfering drugs can be attempted, preferentially in combination with other therapies, to tackle Kras mutant cancers but, to be successful, these strategies have to consider the genetic mutational background, the tissue of origin and the crosstalk between the tumor and the microenvironment. It is of note that some of the putative targets including AMPK and autophagy have, depending on the context, pro-tumorigenic functions, while others, such as ATF4, by regulating transcription of distinct set of genes, are endowed with a wide range of downstream functions. This could pose limits to their exploitation as therapeutic targets (23, 51, 52). Moreover, findings on the role of AMPK in KrasG12D-driven lung cancer during glucose starvation (25), and on the KRAS-dependent transcriptional response to nutrient deprivation (45), reveal that the effects of KRAS mutations on metabolic reprogramming are also strongly influenced by the availability of nutrients which can be heterogeneously distributed within the tumor and change over time. There is a lot more to be learned, there are still big research gaps in the field that need to be addressed in future studies. Moreover the interplay with other pathways, such as PPARγ and WNT/β-catenin, involved in metabolic enzymes changes in other cancers (53, 54) should be further investigated. This growing body of knowledge points to the complexity of this system and suggests that analysis of the genetic context and the metabolic activity of the tumor should be combined to identify KRAS-driven metabolic vulnerabilities and stratify patients.

Author Contributions

EP and LL wrote the manuscript. EP and EM performed the staining showed in Figure 1. DA designed Figure 2. FB and LL reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Work in the authors' lab was supported by grants from the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC Investigator Grant, project 15180 to LL, projects 21065 and 18652 to FB), Fondo Ricerca Locale 2017 (University of Turin) to LL, and FPRC 5xmille Ministero Salute 2015 to LL.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Mariano Barbacid for sharing the Elas-tTA/tetOFF-Cre;K-Ras+/LSL G12V Geo mice.

References

1. Kimmelman AC. Metabolic dependencies in RAS-driven cancers. Clin Cancer Res. (2015) 21:1828–34. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2425

2. Yuneva MO, Fan TW, Allen TD, Higashi RM, Ferraris DV, Tsukamoto T, et al. The metabolic profile of tumors depends on both the responsible genetic lesion and tissue type. Cell Metab. (2012) 15:157–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.12.015

3. Mayers JR, Torrence ME, Danai LV, Papagiannakopoulos T, Davidson SM, Bauer MR, et al. Tissue of origin dictates branched-chain amino acid metabolism in mutant Kras-driven cancers. Science. (2016) 353:1161–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5171

4. Tape CJ, Ling S, Dimitriadi M, McMahon KM, Worboys JD, Leong HS, et al. Oncogenic KRAS regulates tumor cell signaling via stromal reciprocation. Cell. (2016) 165:910–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.029

5. Yang A, Herter-Sprie G, Zhang H, Lin EY, Biancur D, Wang X, et al. Autophagy sustains pancreatic cancer growth through both cell-autonomous and nonautonomous mechanisms. Cancer Discov. (2018) 8:276–87. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0952

6. Sousa CM, Biancur DE, Wang X, Halbrook CJ, Sherman MH, Zhang L, et al. Pancreatic stellate cells support tumour metabolism through autophagic alanine secretion. Nature. (2016) 536:479–83. doi: 10.1038/nature19084

7. Nagarajan A, Dogra SK, Sun L, Gandotra N, Ho T, Cai G, et al. Paraoxonase 2 facilitates pancreatic cancer growth and metastasis by stimulating GLUT1-mediated glucose transport. Mol Cell. (2017) 67:685–701.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.07.014

8. Romero R, Sayin VI, Davidson SM, Bauer MR, Singh SX, LeBoeuf SE, et al. Keap1 loss promotes Kras-driven lung cancer and results in dependence on glutaminolysis. Nat Med. (2017) 23:1362–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.4407

9. Kim J, Hu Z, Cai L, Li K, Choi E, Faubert B, et al. CPS1 maintains pyrimidine pools and DNA synthesis in KRAS/LKB1-mutant lung cancer cells. Nature. (2017) 546:168–72. doi: 10.1038/nature22359

10. Patra KC, Kato Y, Mizukami Y, Widholz S, Boukhali M, Revenco I, et al. Mutant GNAS drives pancreatic tumourigenesis by inducing PKA-mediated SIK suppression and reprogramming lipid metabolism. Nat Cell Biol. (2018) 20:811–22. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0122-3

11. Racker E, Resnick RJ, Feldman R. Glycolysis and methylaminoisobutyrate uptake in rat-1 cells transfected with ras or myc oncogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1985) 82:3535–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.11.3535

12. Hruban RH, Wilentz RE, Kern SE. Genetic progression in the pancreatic ducts. Am J Pathol. (2000) 156:1821–5. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65054-7

13. Guerra C, Barbacid M. Genetically engineered mouse models of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Mol Oncol. (2013) 7:232–47. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2013.02.002

14. Xie H, Hanai J, Ren JG, Kats L, Burgess K, Bhargava P, et al. Targeting lactate dehydrogenase–a inhibits tumorigenesis and tumor progression in mouse models of lung cancer and impacts tumor-initiating cells. Cell Metab. (2014) 19:795–809. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.003

15. Barron CC, Bilan PJ, Tsakiridis T, Tsiani E. Facilitative glucose transporters: implications for cancer detection, prognosis and treatment. Metabolism. (2016) 65:124–39. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.10.007

16. Pinho AV, Mawson A, Gill A, Arshi M, Warmerdam M, Giry-Laterriere M, et al. Sirtuin 1 stimulates the proliferation and the expression of glycolysis genes in pancreatic neoplastic lesions. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:74768–78. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11013

17. Basturk O, Singh R, Kaygusuz E, Balci S, Dursun N, Culhaci N, et al. GLUT-1 expression in pancreatic neoplasia: implications in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and prognosis. Pancreas. (2011) 40:187–92. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318201c935

18. Guerra C, Schuhmacher AJ, Cañamero M, Grippo PJ, Verdaguer L, Pérez-Gallego L, et al. Chronic pancreatitis is essential for induction of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by K-Ras oncogenes in adult mice. Cancer Cell. (2007) 11:291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.01.012

19. Pupo E, Ducano N, Lupo B, Vigna E, Avanzato D, Perera T, et al. Rebound effects caused by withdrawal of MET kinase inhibitor are quenched by a MET therapeutic antibody. Cancer Res. (2016) 76:5019–29. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3107

20. DeBerardinis RJ, Chandel NS. Fundamentals of cancer metabolism. Sci Adv. (2016) 2:e1600200. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1600200

21. Ying H, Kimmelman AC, Lyssiotis CA, Hua S, Chu GC, Fletcher-Sananikone E, et al. Oncogenic Kras maintains pancreatic tumors through regulation of anabolic glucose metabolism. Cell. (2012) 149:656–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.058

22. Santana-Codina N, Roeth AA, Zhang Y, Yang A, Mashadova O, Asara JM, et al. Oncogenic KRAS supports pancreatic cancer through regulation of nucleotide synthesis. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:4945. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07472-8

23. Hardie DG. Molecular pathways: is AMPK a friend or a foe in cancer? Clin Cancer Res. (2015) 21:3836–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3300

24. Kimmelman AC, White E. Autophagy and tumor metabolism. Cell Metab. (2017) 25:1037–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.04.004

25. Eichner LJ, Brun SN, Herzig S, Young NP, Curtis SD, Shackelford DB, et al. Genetic analysis reveals AMPK is required to support tumor growth in murine Kras-dependent lung cancer models. Cell Metab. (2019) 29:285–302.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.10.005

26. Perera RM, Stoykova S, Nicolay BN, Ross KN, Fitamant J, Boukhali M, et al. Transcriptional control of autophagy-lysosome function drives pancreatic cancer metabolism. Nature. (2015) 524:361–5. doi: 10.1038/nature14587

27. Sardiello M, Palmieri M, di Ronza A, Medina DL, Valenza M, Gennarino VA, et al. A gene network regulating lysosomal biogenesis and function. Science. (2009) 325:473–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1174447

28. Settembre C, Di Malta C, Polito VA, Garcia Arencibia M, Vetrini F, Erdin S, et al. TFEB links autophagy to lysosomal biogenesis. Science. (2011) 332:1429–33. doi: 10.1126/science.1204592

29. Sigismund S, Confalonieri S, Ciliberto A, Polo S, Scita G, Di Fiore PP. Endocytosis and signaling: cell logistics shape the eukaryotic cell plan. Physiol Rev. (2012) 92:273–366. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2011

30. Commisso C, Davidson SM, Soydaner-Azeloglu RG, Parker SJ, Kamphorst JJ, Hackett S, et al. Macropinocytosis of protein is an amino acid supply route in Ras-transformed cells. Nature. (2013) 497:633–7. doi: 10.1038/nature12138

31. Recouvreux MV, Commisso C. Macropinocytosis: a metabolic adaptation to nutrient stress in cancer. Front Endocrinol. (2017) 8:261. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00261

32. Gaglio D, Soldati C, Vanoni M, Alberghina L, Chiaradonna F. Glutamine deprivation induces abortive s-phase rescued by deoxyribonucleotides in k-ras transformed fibroblasts. PLoS ONE. (2009) 4:e4715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004715

33. Son J, Lyssiotis CA, Ying H, Wang X, Hua S, Ligorio M, et al. Glutamine supports pancreatic cancer growth through a KRAS-regulated metabolic pathway. Nature. (2013) 496:101–5. doi: 10.1038/nature12040

34. Duan G, Shi M, Xie L, Xu M, Wang Y, Yan H, et al. Increased glutamine consumption in cisplatin-resistant cells has a negative impact on cell growth. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:4067. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21831-x

35. Kerr EM, Gaude E, Turrell FK, Frezza C, Martins CP. Mutant Kras copy number defines metabolic reprogramming and therapeutic susceptibilities. Nature. (2016) 531:110–3. doi: 10.1038/nature16967

36. Pavlova NN, Thompson CB. The emerging hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. (2016) 23:27–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.006

37. Lock R, Roy S, Kenific CM, Su JS, Salas E, Ronen SM, et al. Autophagy facilitates glycolysis during Ras-mediated oncogenic transformation. Mol Biol Cell. (2011) 22:165–78. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e10-06-0500

38. Guo JY, Chen HY, Mathew R, Fan J, Strohecker AM, Karsli-Uzunbas G, et al. Activated Ras requires autophagy to maintain oxidative metabolism and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. (2011) 25:460–70. doi: 10.1101/gad.2016311

39. Guo JY, Teng X, Laddha SV, Ma S, Van Nostrand SC, Yang Y, et al. Autophagy provides metabolic substrates to maintain energy charge and nucleotide pools in Ras-driven lung cancer cells. Genes Dev. (2016) 30:1704–17. doi: 10.1101/gad.283416.116

40. Lock R, Kenific CM, Leidal AM, Salas E, Debnath J. Autophagy-dependent production of secreted factors facilitates oncogenic RAS-driven invasion. Cancer Discov. (2014) 4:466–79. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0841

41. Amaravadi R, Debnath J. Mouse models address key concerns regarding autophagy inhibition in cancer therapy. Cancer Discov. (2014) 4:873–5. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0618

42. Yang A, Rajeshkumar NV, Wang X, Yabuuchi S, Alexander BM, Chu GC, et al. Autophagy is critical for pancreatic tumor growth and progression in tumors with p53 alterations. Cancer Discov. (2014) 4:905–13. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0362

43. Kinsey CG, Camolotto SA, Boespflug AM, Guillen KP, Foth M, Truong A, et al. Protective autophagy elicited by RAF → MEK → ERK inhibition suggests a treatment strategy for RAS-driven cancers. Nat Med. (2019) 25:620–7. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0367-9

44. Bryant KL, Stalnecker CA, Zeitouni D, Klomp JE, Peng S, Tikunov AP, et al. Combination of ERK and autophagy inhibition as a treatment approach for pancreatic cancer. Nat Med. (2019) 25:628–40. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0368-8

45. Gwinn DM, Lee AG, Briones-Martin-Del-Campo M, Conn CS, Simpson DR, Scott AI, et al. Oncogenic KRAS regulates amino acid homeostasis and asparagine biosynthesis via ATF4 and alters sensitivity to L-asparaginase. Cancer Cell. (2018) 33:91–107.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.12.003

46. Sullivan LB, Gui DY, Vander Heiden MG. Altered metabolite levels in cancer: implications for tumour biology and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. (2016) 16:680–93. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.85

47. Morris SM. Regulation of enzymes of the urea cycle and arginine metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. (2002) 22:87–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.110801.140547

48. Röhrig F, Schulze A. The multifaceted roles of fatty acid synthesis in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. (2016) 16:732–49. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.89

49. Padanad MS, Konstantinidou G, Venkateswaran N, Melegari M, Rindhe S, Mitsche M, et al. Fatty acid oxidation mediated by Acyl-CoA synthetase long chain 3 is required for mutant KRAS lung tumorigenesis. Cell Rep. (2016) 16:1614–28. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.009

50. Singh A, Ruiz C, Bhalla K, Haley JA, Li QK, Acquaah-Mensah G, et al. De novo lipogenesis represents a therapeutic target in mutant Kras non-small cell lung cancer. FASEB J. (2018) 32:7018–27. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800204

51. Nazio F, Bordi M, Cianfanelli V, Locatelli F, Cecconi F. Autophagy and cancer stem cells: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic applications. Cell Death Differ. (2019) 26:690–702. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0292-y

52. Morselli E, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Vicencio JM, Criollo A, Maiuri MC, et al. Anti- and pro-tumor functions of autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2009) 1793:1524–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.01.006

53. Lecarpentier Y, Claes V, Vallée A, Hébert JL. Thermodynamics in cancers: opposing interactions between PPAR gamma and the canonical WNT/beta-catenin pathway. Clin Transl Med. (2017) 6:14. doi: 10.1186/s40169-017-0144-7

54. Lemieux E, Cagnol S, Beaudry K, Carrier J, Rivard N. Oncogenic KRAS signalling promotes the Wnt/β-catenin pathway through LRP6 in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. (2015) 34:4914–27. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.416

Glossary

The use of capital letters or the italic to indicate KRAS reflects the

nomenclature guidelines here reported.

KRAS human protein.

KRAS human gene.

Kras murine protein.

Kras murine gene.

Keywords: KRAS, PDAC, metabolic rewiring, metabolic adaptability in cancer, NSCLC, gluocose metabolism in cancer, glycolysis

Citation: Pupo E, Avanzato D, Middonti E, Bussolino F and Lanzetti L (2019) KRAS-Driven Metabolic Rewiring Reveals Novel Actionable Targets in Cancer. Front. Oncol. 9:848. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00848

Received: 01 July 2019; Accepted: 19 August 2019;

Published: 30 August 2019.

Edited by:

Alessandro Rimessi, University of Ferrara, ItalyReviewed by:

Chiara Ambrogio, Dana–Farber Cancer Institute, United StatesNikolaos Patsoukis, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, United States

Copyright © 2019 Pupo, Avanzato, Middonti, Bussolino and Lanzetti. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Letizia Lanzetti, bGV0aXppYS5sYW56ZXR0aUBpcmNjLml0

Emanuela Pupo

Emanuela Pupo Daniele Avanzato

Daniele Avanzato Emanuele Middonti1,2

Emanuele Middonti1,2 Letizia Lanzetti

Letizia Lanzetti