95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Oncol. , 06 August 2019

Sec. Molecular and Cellular Oncology

Volume 9 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.00739

This article is part of the Research Topic Roles Of Non-coding RNAs In Tumor Growth And Development View all 21 articles

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a class of more than 200 nucleotides RNA transcripts which have limited protein coding capacity. They regulate numerous biological processes in cancers through diverse molecular mechanisms. Aberrant expression of lncRNAs has been frequently associated with human cancer. Furthermore, the tumor microenvironment (TME) is composed of different cells such as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), endothelial cells and infiltrated immune cells, and all of which participate in communication with tumor cells affecting the progression of tumor. LncRNAs are directly and indirectly involved in the crosstalk between stromal cells and tumor cells and dysregulated lncRNAs expression in these cells could drive tumorigenesis. In this review, we explore the influence of aberrantly expressed lncRNAs in tumor progression, clarify the critical roles of lncRNAs in the TME, summarize findings on crosstalk between infiltrated immune cells, CAFs, endothelial cells, and tumor cells via lncRNAs, and discuss the promise of lncRNAs as tumor diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a diverse class of transcribed RNA molecules that are more than 200 nucleotides with limited protein coding potential (1, 2). Current estimates, from the GENCODE database (www.gencodegenes.org), indicate that the human genome contains ~16,000 lncRNA genes that encode more than 28,000 distinct lncRNAs. Many lncRNAs have emerged as critical players in regulating numerous biological processes in cancer, such as differentiation, cell cycle regulation, and immune response (3–5). They can directly act as tumor suppressors or oncogenes, or are regulated by well-known tumor suppressors or oncogenes, at transcriptional or post-transcriptional levels (6, 7). Furthermore, emerging evidence have shown that dysregulated lncRNAs are greatly involved in various cancers (8–10). For instance, the PCA3 (also called DD3) and PCGEM1 were the first lncRNAs that were associated with cancer because they were overexpressed in prostate cancer (11, 12). PCA3 might be used as a biomarker for the diagnosis of prostate cancer and PCGEM1 involved in c-MYC activation and androgen receptor transcriptional activation was associated with the progression of prostate cancer (13, 14). Moreover, lncRNA MALAT1 was reported to be overexpressed in multiple cancer types, such as colorectal cancer, non-small cell lung cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC); its expression was also correlated with tumor progression and poor prognosis (15–18). Importantly, these studies suggested that aberrantly expressed lncRNAs can be used as biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and prognosis as well as potential targets for cancer therapy.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a complicated physiological and biochemical system that plays critical functions in tumorigenesis, progression, and metastasis (19–21). In addition to tumor cells, the TME consists mainly of the extracellular matrix (ECM), the tumor vascular system, other non-malignant cells as well as the acidic and hypoxic environment of the tumor (21, 22). With the development of biological technology, different cell types have been identified in the TME, including cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), fat cells, endothelial cells, and infiltrated immune cells such as T lymphocytes, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and tumor-associated macrophages (22–24). Most of these stromal cells significantly contribute to the initiation and progression of tumors. In recent years, a growing appreciation of the TME indicated that lncRNAs play significant roles in the interactions between tumor cells and stromal cells (25–30). In this review, we discuss the role of lncRNAs in the crosstalk between CAFs, endothelial cells, infiltrated immune cells and tumor cells, and the promise of lncRNAs in cancer treatment, to increase our knowledge of the function of lncRNAs within the TME and lay a foundation for lncRNA-based anti-tumor treatment strategies.

CAFs, one of the most abundant stromal cells in the TME, are critically involved in tumor progression (31, 32). CAFs modulate the biology of cancer cells through releasing numerous regulatory factors, such as chemokines, cytokines and growth factors, and thus these cells affect the progression of tumor (31, 33). Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), which is secreted by CAFs, is a critical factor promoting the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis of cancer cells such as bladder cancer cells and breast cancer cells (34, 35). And the secretion of TGF-β1 by CAFs induces the metastatic activity of cancer cells by regulating the expression of lncRNAs. For instance, CAFs promoted EMT of bladder cancer cells by activating the transcription of lncRNA-ZEB2NAT via TGF-β1 secretion (34). Similarly, TGF-β1 secreted by CAFs upregualted lncRNA HOTAIR expression to promote EMT and metastasis in breast cancer (35). Furthermore, in oral squamous cell carcinoma, LncRNA-CAF could elevate the expression of cytokine IL-33 to promote the activation of CAFs, leading to proliferation of tumor cells. In return, tumor cells also secreted exosomes including LncRNA-CAF to stroma and increased LncRNA-CAF levels for the activation of CAFs (36).In addition, LINC00092 was found to be upregulated in response to the CAF-secreted chemokine CXCL14 in ovarian cancer cells. Simultaneously, LINC00092, which induced a glycolytic phenotype of ovarian cancer cells, was critical for the maintenance of CAF-like features by interacting with PFKFB2 (37). Therefore, LncRNA-CAF and LINC00092 were served as significant modulators of feedback loop in the cancer cells and CAFs, which were critical for the progression of cancer. Collectively, these studies indicated the importance of lncRNAs in the interaction between the CAFs and cancer cells and provided a potential application for lncRNAs as targets of cancer treatment.

Endothelial cells, which line the interior surface of blood vessels, are important components of stroma in TME (26, 38). They are believed to be critical for angiogenesis and tumor metastasis, and lncRNAs may affect the progression of tumor through modulating the biological behavior of endothelial cells. LncRNA H19, for instance, was reported to be significantly upregulated in glioma-associated endothelial cells cultured in glioma-conditioned medium. Knockdown of H19 inhibited glioma-induced endothelial cell proliferation, migration and tube formation in vitro. Mechanistic evidence revealed that H19 modulated the biological behavior of glioma-associated endothelial cells by suppressing miR-29a (39). Furthermore, lncRNA-APC1 played an important tumor-suppressive role in the pathogenesis of colorectal carcinoma. Following mechanism studies showed that lncRNA-APC1 decreased exosome production in colorectal carcinoma cells through reducing the stability of Rab5b mRNA, and this action suppressed tumor angiogenesis through inhibiting the overactivation of the MAPK pathway in endothelial cells (40). In summary, dysregulated lncRNAs affect the biological behavior of endothelial cells by diverse mechanisms, thus modulating specific lncRNA expression in tumor cells or/and endothelial cells may have a significant effect on the progression of cancer.

TAMs are important regulators of the TME, and might regulate tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis (41). Two major functional types of macrophages have been identified, including classically activated (M1) and alternatively activated (M2) macrophages (23, 41, 42). M1 macrophages participate in the Th1-type inflammatory response and have anti-tumorigenic functions, while M2 macrophages promote anti-inflammatory responses and have a pro-tumorigenic role (23, 43, 44). Several studies have indicated that lncRNAs could modulate M2 polarization of macrophages to affect tumor cells migration and invasion. For example, lncRNA CCAT1 could modulate the TME of prostate cancer through regulating macrophages polarization. Knockdown of lncRNA CCAT1 enhanced macrophages polarization to M2 through upregulating the expression of miR-148a and further promoted prostate cancer cells migration and invasion (45). LncRNA NIFK-AS1 also played a key role in modulating the polarization of TAMs in endometrial cancer. It could suppress M2 macrophages polarization by inhibiting miR-146a, thus reducing the endometrial cancer cells proliferation, migration and invasion (46). Moreover, a cell model-based microarray analysis was used to detect lncRNAs involved in M2 polarization and lncRNA-MM2P was found to be upregulated during M2 polarization. In addition, further studies demonstrated that lncRNA-MM2P promoted M2 polarization of macrophages by reducing phosphorylation on STAT6, then affecting macrophage-mediated tumorigenesis and tumor growth (47).

Furthermore, CCL2, which is produced by different tumor types, plays a critical role in tumor metastasis (48, 49). Tumor-derived CCL2 is released into the TME and recruits macrophages to tumor cells, which contribute to tumor cells proliferation, angiogenesis, and immune response evasion (48, 50). It has been demonstrated that lncRNAs could modulate the TME by regulating the expression of CCL2 and further affected metastasis. For example, lncRNA LNMAT1 was greatly upregulated in lymph node-metastatic bladder cancer. The authors showed that LNMAT1 activated the transcription of CCL2 through enhancing hnRNPL-mediated H3K4me3 at the CCL2 promoter. Moreover, LNMAT1-induced CCL2 regulated the TME through recruiting TAMs, ultimately resulting in lymphatic metastasis of bladder cancer (51). Similarly, the expression of lnc-BM was markedly upregulated in breast cancer cells. High expression of lnc-BM also promoted breast cancer brain metastasis in preclinical mouse models. Mechanistically, lnc-BM induced STAT3-dependent expression of CCL2 to attract macrophages to cancer cells, thus enhancing breast cancer brain metastasis (52).

MDSCs generated in the bone marrow are one of the major components of TME, and these cells play a critical role in cancer progression by suppressing immune responses (53, 54). MDSCs have immunosuppressive activity in pathological conditions through numerous mechanisms involving inducible NO synthase (iNOS), arginase 1 (ARG1), oxygen species (ROS), and nitric oxide (NO) (54, 55). It has been demonstrated that several lncRNAs such as lnc-chop, lnc-C/EBPβ, and lncRNA Pvt1 contributed to the regulation of the immunosuppressive function of MDSCs through modulating the production of ROS and NO or ROS and ARG1.

Notably, lnc-chop interacted with CHOP and the C/EBPβ isoform LIP to increase the activity of C/EBPβ and upregulate target transcripts, such as ARG1, NOS2, COX2, and NOX2. High levels of these target transcripts could result in the production of ROS and NO, thus promoting tumor growth by enhancing the immunosuppression function of MDSCs (56). In contrast, a recent study found that lnc-C/EBPβinhabited the activation of C/EBPβ, decreased the expression of NO and ROS, and further suppressed the immunosuppressive capacity of MDSCs in the tumor environment (57). Granulocytic MDSCs (G-MDSCs) constitute ~70–80% of MDSCs in cancer patients and tumor-bearing mice (58–60). A recent study showed that LncRNA Pvt1 was critical in modulating the immunosuppressive activity of G-MDSCs. The author found that lncRNA Pvt1 knockdown significantly suppressed G-MDSC-mediated immunosuppression in vitro by decreasing the level of ROS and ARG1. In addition, knockdown of lncRNA Pvt1 delayed tumor progression in tumor-bearing mice by inhibiting the function of G-MDSCs (61). These findings suggest that lncRNAs play significant roles in the control of tumor-associated MDSCs and lncRNAs may be potential antitumor immunotherapy targets.

T cells, a predominant immune cell type in the TME, can exert both tumor promoting and suppressive functions, as determined by their effector functions (24, 62). LncRNAs have been gradually recognized as modulators of T cell development, activation and differentiation (63). CD8+ T cells, major population of T cells, are prominent anti-tumor cells in TME (60). Recent studies have shown that lncRNAs could modulate the function of CD8+ T cells in the TME through diverse mechanisms, further affecting the progression of cancer. Lnc-Tim3 was found to be upregulated and negatively correlated with the production of IL-2 and IFN-γ in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells of patients with HCC. Mechanistically, lnc-Tim3 bound to Tim-3 and induced nuclear translocation of Bat3 in HCC, which compromised anti-tumor immunity by promoting CD8 + T cell exhaustion (64). Moreover, lnc-sox5 was significantly upregulated in colorectal cancer tissues and lnc-sox5 knockdown promoted the cytotoxicity and infiltration of CD8+T cells. Mechanistic evidence revealed that lnc-sox5 regulated the CD8+T cell infiltration and cytotoxicity through modulating the expression of IDO and therefore affecting the progression of colorectal cancer (65). These data indicate that lnc-Tim3 and lnc-sox5 play different roles in modulating the CD8+T cells to affect the progression of tumor.

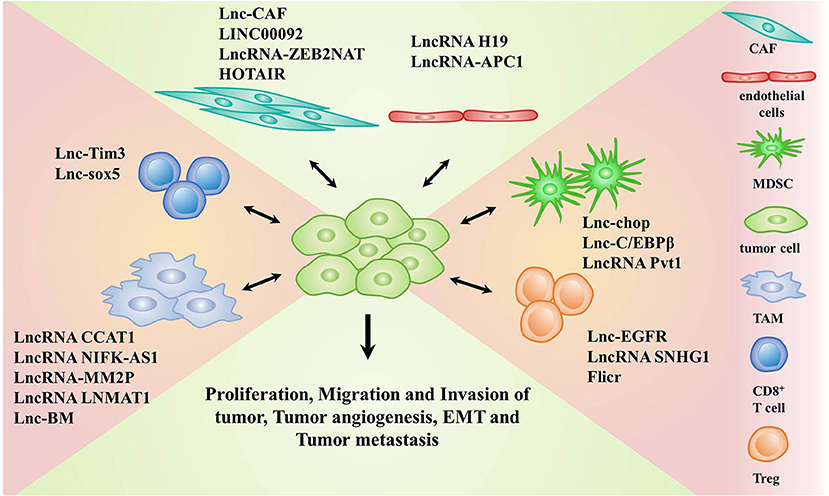

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are an immunosuppressive subset of CD4+ T cells, which may contribute to the suppression of anti-tumor immunity as they frequently accumulate in the TME (66, 67). Several studies have revealed that some lncRNAs such as lnc-EGFR, lncRNA SNHG1, and Flicr modulated the function of Tregs. Among them, lnc-EGFR was found to be overexpressed in Tregs of patients with HCC. It stimulated the differentiation of Tregs and promoted the growth of tumor in an EGFR-dependent manner. Mechanistic evidence revealed that lnc-EGFR specially bound to EGFR and enhanced AP-1/NF-AT1/Foxp3 signaling, leading to Treg differentiation, and HCC progression (68). LncRNA SNHG1 was also reported to promote the differentiation of Tregs. Knockdown of lncRNA SNHG1 could suppress Treg differentiation by increasing the expression of miR-448 and reducing level of IDO, further alleviating the immune escape in breast cancer (69). Moreover, Flicr, a lncRNA, was reported to enhance the immunosuppressive function of Tregs by modulating the expression of Foxp3. So, Flicr might be associated with tumors, but its roles in the TME remains unclear (70). Collectively, these data indicate that the targeting of specific lncRNAs in T cells is promising for tumor therapy. LncRNAs involved in the communication between tumor cells and stromal cells are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Figure 1. LncRNAs implicated in the crosstalk between stromal cells and tumor cells. Stromal cells include cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs), endothelial cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), CD8+T cells, and regulatory T cells (Tregs).

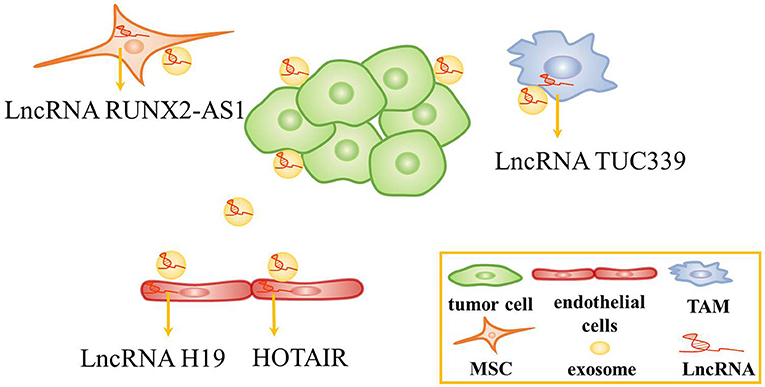

Exosomes are critical mediators in intercellular communication through carrying intracellular components including DNA, RNA and protein to the recipient cells (71, 72). Tumor-derived exosomes can be used to change the TME, affect tumor cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and so on (73–75). In recent years, the role of exosomal lncRNAs in the TME has garnered increasing attention (28, 76). Several studies have shown that tumor cell-derived exosomal lncRNAs could affect the function of stromal cells in the TME (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The role of exosomes in the tumor microenvironment. Tumor cells-derived exosomal lncRNAs are transferred to endothelial cells, tumor-associated macrophage (TAMs), and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) to alter the function of these cells.

Recent studies have revealed that tumor cell-derived exosomal lncRNAs are conveyed to endothelial cells to affect angiogenesis. For instance, lncRNA H19 was found to be highly expressed in CD90+ liver cancer cells. Interestingly, lncRNA H19, which was packed inside exosomes secreted by CD90+ liver cancer cells, was conveyed to and internalized by endothelial cells. Then, lncRNA H19 promoted angiogenesis by increasing VEGF production and release (77). Similarly, HOTAIR was abundant and was packed inside exosomes in glioma cells. Exosomal HOTAIR was transferred to endothelial cells, stimulating angiogenesis by upregulating the expression of VEGFA (78).

In addition, exosomal lncRNAs has been found to be transferred to macrophages and mesenchymal stem cells to alter the function of these cells. In HCC, TUC339 was identified as a kind of lncRNA abundant in tumor-derived exosomes and could be transferred from tumor cells to macrophages. Then, exosomal lncRNA TUC339 regulated macrophage cytokine production, M1/M2 polarization and phagocytosis, while the regulation mechanism needs further investigation (79). Besides, lncRNA RUNX2-AS1 could be packed inside exosomes and transmitted to mesenchymal stem cells. It might suppress the osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by modulating the expression of RUNX2 in multiple myeloma (80). Taken together, several studies revealed that tumor cells-derived exosomes could regulate the TME and affect tumor progression. Thus, tumor cells-derived exosomes containing lncRNAs might be served as biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Numerous lncRNAs are aberrantly expressed in different cancer types, and their expression levels are associated with the initiation and progression of tumors (81). Recent and ongoing studies have improved our understanding of the role of lncRNAs in tumor biology (82). LncRNAs are emerging as novel molecules involved in tumor progression and are acted as promising biomarkers and therapeutic targets in cancer (83–85).

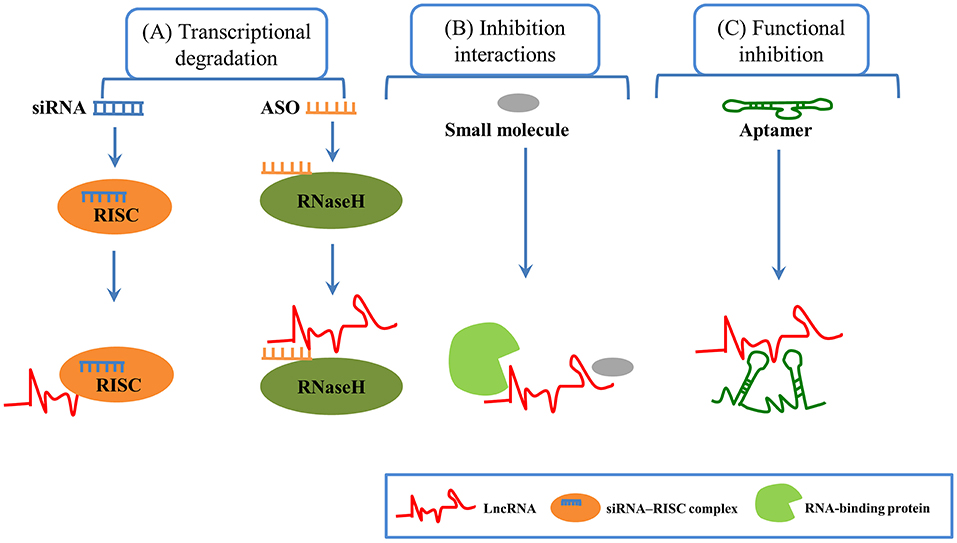

Due to their physiological and pathological roles in cancer, lncRNAs should be considered as candidates for biomarkers in cancer diagnostics and prognoses (29, 86, 87). For example, serum lncRNA HOTAIR was significantly higher in glioblastoma multiforme patients than in normal controls, which can be served as a novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in this disease (88). Similarly, exosomal lncRNA UEGC1 in the plasma was remarkably upregulated in early gastric cancer, indicating it might be a promising biomarker for early gastric cancer diagnosis (89). In a study of 246 subjects including 126 gastric cancer patients and 120 healthy controls, serum exosomal lncRNA HOTTIP was identified as a potential biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis in gastric cancer (90). LncRNAs are also emerging as therapeutic targets for cancer (91). Several features of lncRNAs need to be considered to support lncRNAs as therapeutic targets. First, lncRNAs structural complexity and participation in multicomponent complexes affords few potential targetable key residues to regulate structure-based interactions. Second, lncRNAs can play critical regulatory roles in gene expression and their expression levels are often lower than protein-coding genes. Third, lncRNAs are expressed in a tissue or cell-type specific manner, making them potential efficacious targets for tumor therapy. In addition, lncRNAs may also participate in cell-to-cell communication (84, 86, 92). LncRNAs can be targeted by multiple approaches, such as antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs), short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), aptamers, and small molecule inhibitor (Figure 3). ASOs also have already shown success in modulating coding genes involved in different kinds of solid tumors and other disease (93–96). ASOs are emerging as a potential therapeutic approach for targeting cancer-associated lncRNAs (97). For example, in the MMTV-PyMT mouse mammary carcinoma model, MALAT1 could promote tumor growth and metastasis. Then, in this model, the application of ASOs against MALAT1 resulted in slower tumor proliferation and a reduction in metastasis (98). Moreover, in a mouse xenograft model, MALAT1 ASOs was effective in suppressing lung cancer spreading (99). Thus, MALAT1 may be a potential therapeutic target, and MALAT1 ASOs may be a promising therapy approach for several types of cancer, but further assessment will be needed. A great number of studies have shown that siRNAs are used to against their target mRNAs for different disorders including cancer and metabolic disorders (100, 101). A few lncRNAs were silenced using siRNAs in cell lines (100, 102). However, preclinical studies using siRNAs/shRNAs to target lncRNAs were very limited. In human breast cancer cell lines, siRNA-mediated downregulation of HOTAIR inhibited cancer cell viability and matrix invasion (103). In human prostate cancer cell lines, siRNAs directed against MALAT led to suppression of cancer cell growth, migration and invasion (104). Moreover, subcutaneous injection of gastric cancer cell lines transfected with HOTAIR shRNA suppressed engraftment efficiency in nude mice (105). Aptamers can specifically bind to their target lncRNAs depending on the 3-dimensional shape of the lncRNA structures. Several reports have demonstrated promising effects of aptamers to modulate RNA functions, thus aptamers may be potential therapeutic agents to target lncRNAs. For example, Ayatollahi et al. demonstrated the aptamer-targeted Bcl-xL shRNAs delivery into lung cancer cells using alkyl modified PAMAM dendrimers (106). Small molecule inhibitors targeting a unique triple-helical structural element in lncRNAs (such as MALAT1 and NEAT1) are likely to destabilize the transcript to confer a therapeutic effect, although this needs further exploration (107–110).

Figure 3. LncRNA-based therapeutic methods in cancer. (A) Transcriptional degradation: Short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), which are double-stranded RNAs, can degrade target RNAs through RISC (RNA-induced silencing complex). Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), which are single-stranded oligonucleotide sequence, offer specific complementarity, and Rnase H-mediated degradation of target lncRNA. (B) Inhibition interactions: Small molecules can inhibit the interaction between lncRNAs and protein. (C) Functional inhibition: Aptamers (short RNA or DNA oligonucleotides with 3-dimensional structure) can bind to their target lncRNAs at specific structural regions.

LncRNAs are multifunctional molecules that play critical roles in various biological processes, and dysregulated lncRNAs are often associated with a variety of pathophysiological conditions, such as cancer. We reviewed the recently published studies involving of lncRNAs in the TME. Emerging evidence indicates that lncRNAs play critical roles in modulating the TME and tumor progression. In addition, we described the crosstalk of lncRNAs between immune cells, CAFs, endothelial cells, and tumor cells in the TME and the promise of lncRNAs as tumor diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets.

Finally, tumor cells are thought to produce lncRNA-containing exosomes and tumor-derived exosomal lncRNAs may mediate direct communication between tumor cells and the TME, as illustrated in this review. Further research is still required to better understand the role of lncRNAs in the TME. In the future, lncRNAs may be used in strategies for early cancer detection, monitoring treatment responses and targeted cancer therapy.

DC and LW were the major contributors in writing the manuscript. TL and JT performed the literature search. HL and QW revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Spizzo R, Almeida MI, Colombatti A, Calin GA. Long non-coding RNAs and cancer: a new frontier of translational research? Oncogene. (2012) 31:4577–87. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.621

2. Nagano T, Fraser P. No-nonsense functions for long noncoding RNAs. Cell. (2011) 145:178–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.014

3. Guttman M, Amit I, Garber M, French C, Lin MF, Feldser D, et al. Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature. (2009) 458:223–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07672

4. Qiu M, Xu Y, Wang J, Zhang E, Sun M, Zheng Y, et al. A novel lncRNA, LUADT1, promotes lung adenocarcinoma proliferation via the epigenetic suppression of p27. Cell Death Dis. (2015) 6:e1858. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.203

5. Bach DH, Lee SK. Long noncoding RNAs in cancer cells. Cancer Lett. (2018) 419:152–66. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.01.053

6. Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Lau SK, Boutros PC, Khosravi F, Jurisica I, Andrulis IL, et al. The c-Myc oncogene directly induces the H19 noncoding RNA by allele-specific binding to potentiate tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. (2006) 66:5330–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0037

7. Huarte M, Guttman M, Feldser D, Garber M, Koziol MJ, Kenzelmann-Broz D, et al. A large intergenic noncoding RNA induced by p53 mediates global gene repression in the p53 response. Cell. (2010) 142:409–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.040

8. Iyer MK, Niknafs YS, Malik R, Singhal U, Sahu A, Hosono Y, et al. The landscape of long noncoding RNAs in the human transcriptome. Nat Genet. (2015) 47:199–208. doi: 10.1038/ng.3192

9. Ling H, Vincent K, Pichler M, Fodde R, Berindan-Neagoe I, Slack FJ, et al. Junk DNA and the long non-coding RNA twist in cancer genetics. Oncogene. (2015) 34:5003–11. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.456

10. Tsai MC, Spitale RC, Chang HY. Long intergenic noncoding RNAs: new links in cancer progression. Cancer Res. (2011) 71:3–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2483

11. Bussemakers MJ, van Bokhoven A, Verhaegh GW, Smit FP, Karthaus HF, Schalken JA, et al. DD3: a new prostate-specific gene, highly overexpressed in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. (1999) 59:5975–9. PubMed PMID: 10606244.

12. Srikantan V, Zou Z, Petrovics G, Xu L, Augustus M, Davis L, et al. PCGEM1, a prostate-specific gene, is overexpressed in prostate cancer. Proce Natl Acad Sci USA. (2000) 97:12216–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.12216

13. Hessels D, Klein Gunnewiek JM, van Oort I, Karthaus HF, van Leenders GJ, et al. DD3(PCA3)-based molecular urine analysis for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. (2003) 44:8–15; discussion−6. PubMed PMID: 12814669. doi: 10.1016/S0302-2838(03)00201-X

14. Yang L, Lin C, Jin C, Yang JC, Tanasa B, Li W, et al. lncRNA-dependent mechanisms of androgen-receptor-regulated gene activation programs. Nature. (2013) 500:598–602. doi: 10.1038/nature12451

15. Ji P, Diederichs S, Wang W, Boing S, Metzger R, Schneider PM, et al. MALAT-1, a novel noncoding RNA, and thymosin beta4 predict metastasis and survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene. (2003) 22:8031–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206928

16. Amodio N, Raimondi L, Juli G, Stamato MA, Caracciolo D, Tagliaferri P, et al. MALAT1: a druggable long non-coding RNA for targeted anti-cancer approaches. J Hematol Oncol. (2018) 11:63. doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0606-4

17. Schmidt LH, Spieker T, Koschmieder S, Schaffers S, Humberg J, Jungen D, et al. The long noncoding MALAT-1 RNA indicates a poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer and induces migration and tumor growth. J Thorac Oncol. (2011) 6:1984–92. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182307eac

18. Li Q, Dai Y, Wang F, Hou S. Differentially expressed long non-coding RNAs and the prognostic potential in colorectal cancer. Neoplasma. (2016) 63:977–83. doi: 10.4149/neo_2016_617

19. Singh SR, Rameshwar P, Siegel P. Targeting tumor microenvironment in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. (2016) 380:203–4. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.04.009

20. Balkwill FR, Capasso M, Hagemann T. The tumor microenvironment at a glance. J Cell Sci. (2012) 125(Pt 23):5591–6. doi: 10.1242/jcs.116392

21. Chen Q, Liu G, Liu S, Su H, Wang Y, Li J, et al. Remodeling the tumor microenvironment with emerging nanotherapeutics. Trends Pharmacol Sci. (2018) 39:59–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2017.10.009

22. Jiang X, Wang J, Deng X, Xiong F, Ge J, Xiang B, et al. Role of the tumor microenvironment in PD-L1/PD-1-mediated tumor immune escape. Mol Cancer. (2019) 18:10. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0928-4

23. Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. (2013) 19:1423–37. doi: 10.1038/nm.3394

24. Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. (2010) 140:883–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025

25. Yang N, Zhu S, Lv X, Qiao Y, Liu YJ, Chen J. MicroRNAs: pleiotropic regulators in the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:2491. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02491

26. Kohlhapp FJ, Mitra AK, Lengyel E, Peter ME. MicroRNAs as mediators and communicators between cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment. Oncogene. (2015) 34:5857–68. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.89

27. Rupaimoole R, Calin GA, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood AK. miRNA deregulation in cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Discov. (2016) 6:235–46. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0893

28. Sun Z, Yang S, Zhou Q, Wang G, Song J, Li Z, et al. Emerging role of exosome-derived long non-coding RNAs in tumor microenvironment. Mol Cancer. (2018) 17:82. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0831-z

29. Lin YH, Wu MH, Yeh CT, Lin KH. Long non-coding RNAs as mediators of tumor microenvironment and liver cancer cell communication. Int J Mol Sci. (2018) 19:E3742. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123742

30. Del Vecchio F, Lee GH, Hawezi J, Bhome R, Pugh S, Sayan E, et al. Long non-coding RNAs within the tumour microenvironment and their role in tumour-stroma cross-talk. Cancer Lett. (2018) 421:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.02.022

31. Chen X, Song E. Turning foes to friends: targeting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2019) 18:99–115. doi: 10.1038/s41573-018-0004-1

32. Kalluri R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. (2016) 16:582–98. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.73

33. Gaggioli C, Hooper S, Hidalgo-Carcedo C, Grosse R, Marshall JF, Harrington K, et al. Fibroblast-led collective invasion of carcinoma cells with differing roles for RhoGTPases in leading and following cells. Nat Cell Biol. (2007) 9:1392–400. doi: 10.1038/ncb1658

34. Zhuang J, Lu Q, Shen B, Huang X, Shen L, Zheng X, et al. TGFbeta1 secreted by cancer-associated fibroblasts induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition of bladder cancer cells through lncRNA-ZEB2NAT. Sci Rep. (2015) 5:11924. doi: 10.1038/srep11924

35. Ren Y, Jia HH, Xu YQ, Zhou X, Zhao XH, Wang YF, et al. Paracrine and epigenetic control of CAF-induced metastasis: the role of HOTAIR stimulated by TGF-ss1 secretion. Molecul Cancer. (2018) 17:5. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0758-4

36. Ding L, Ren J, Zhang D, Li Y, Huang X, Hu Q, et al. A novel stromal lncRNA signature reprograms fibroblasts to promote the growth of oral squamous cell carcinoma via LncRNA-CAF/interleukin-33. Carcinogenesis. (2018) 39:397–406. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgy006

37. Zhao L, Ji G, Le X, Wang C, Xu L, Feng M, et al. Long noncoding RNA LINC00092 acts in cancer-associated fibroblasts to drive glycolysis and progression of ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. (2017) 77:1369–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1615

38. Junttila MR, de Sauvage FJ. Influence of tumour micro-environment heterogeneity on therapeutic response. Nature. (2013) 501:346–54. doi: 10.1038/nature12626

39. Jia P, Cai H, Liu X, Chen J, Ma J, Wang P, et al. Long non-coding RNA H19 regulates glioma angiogenesis and the biological behavior of glioma-associated endothelial cells by inhibiting microRNA-29a. Cancer Lett. (2016) 381:359–69. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.08.009

40. Wang FW, Cao CH, Han K, Zhao YX, Cai MY, Xiang ZC, et al. APC-activated long noncoding RNA inhibits colorectal carcinoma pathogenesis through reduction of exosome production. J Clin Invest. (2019) 129:727–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI122478

41. Yang L, Zhang Y. Tumor-associated macrophages, potential targets for cancer treatment. Biomarker Res. (2017) 5:25. doi: 10.1186/s40364-017-0106-7

42. Allavena P, Sica A, Garlanda C, Mantovani A. The Yin-Yang of tumor-associated macrophages in neoplastic progression and immune surveillance. Immunol Rev. (2008) 222:155–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00607.x

43. Lewis CE, Harney AS, Pollard JW. The multifaceted role of perivascular macrophages in tumors. Cancer Cell. (2016) 30:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.05.017

44. Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. (2010) 11:889–96. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937

45. Liu J, Ding D, Jiang Z, Du T, Liu J, Kong Z. Long non-coding RNA CCAT1/miR-148a/PKCzeta prevents cell migration of prostate cancer by altering macrophage polarization. Prostate. (2019) 79:105–12. doi: 10.1002/pros.23716

46. Zhou YX, Zhao W, Mao LW, Wang YL, Xia LQ, Cao M, et al. Long non-coding RNA NIFK-AS1 inhibits M2 polarization of macrophages in endometrial cancer through targeting miR-146a. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. (2018) 104:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2018.08.017

47. Cao J, Dong R, Jiang L, Gong Y, Yuan M, You J, et al. LncRNA-MM2P identified as a modulator of macrophage M2 polarization. Cancer Immunol Res. (2019) 7:292–305. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0145

48. Bonapace L, Coissieux MM, Wyckoff J, Mertz KD, Varga Z, Junt T, et al. Cessation of CCL2 inhibition accelerates breast cancer metastasis by promoting angiogenesis. Nature. (2014) 515:130–3. doi: 10.1038/nature13862

49. Zhang J, Lu Y, Pienta KJ. Multiple roles of chemokine. (C-C motif) ligand 2 in promoting prostate cancer growth. J Natl Cancer Institute. (2010) 102:522–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq044

50. Pena CG, Nakada Y, Saatcioglu HD, Aloisio GM, Cuevas I, Zhang S, et al. LKB1 loss promotes endometrial cancer progression via CCL2-dependent macrophage recruitment. J Clin Invest. (2015) 125:4063–76. doi: 10.1172/JCI82152

51. Chen C, He W, Huang J, Wang B, Li H, Cai Q, et al. LNMAT1 promotes lymphatic metastasis of bladder cancer via CCL2 dependent macrophage recruitment. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:3826. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06152-x

52. Wang S, Liang K, Hu Q, Li P, Song J, Yang Y, et al. JAK2-binding long noncoding RNA promotes breast cancer brain metastasis. J Clin Invest. (2017) 127:4498–515. doi: 10.1172/JCI91553

53. Kumar V, Patel S, Tcyganov E, Gabrilovich DI. The nature of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. (2016) 37:208–20. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.01.004

54. Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. (2009) 9:162–74. doi: 10.1038/nri2506

55. Bronte V, Zanovello P. Regulation of immune responses by L-arginine metabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. (2005) 5:641–54. doi: 10.1038/nri1668

56. Gao Y, Wang T, Li Y, Zhang Y, Yang R. Lnc-chop promotes immunosuppressive function of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor and inflammatory environments. J Immunol. (2018) 200:2603–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701721

57. Gao Y, Sun W, Shang W, Li Y, Zhang D, Wang T, et al. Lnc-C/EBPbeta negatively regulates the suppressive function of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Immunol Res. (2018) 6:1352–63. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0108

58. Movahedi K, Guilliams M, Van den Bossche J, Van den Bergh R, Gysemans C, Beschin A, et al. Identification of discrete tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations with distinct T cell-suppressive activity. Blood. (2008) 111:4233–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099226

59. Lang S, Bruderek K, Kaspar C, Hoing B, Kanaan O, Dominas N, et al. Clinical relevance and suppressive capacity of human myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets. Clin Cancer Res. (2018) 24:4834–44. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3726

60. Tian X, Tian J, Tang X, Rui K, Zhang Y, Ma J, et al. Particulate beta-glucan regulates the immunosuppression of granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells by inhibiting NFIA expression. Oncoimmunology. (2015) 4:e1038687. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1038687

61. Zheng Y, Tian X, Wang T, Xia X, Cao F, Tian J, et al. Long noncoding RNA Pvt1 regulates the immunosuppression activity of granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. Molecular Cancer. (2019) 18:61. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0978-2

62. Gonzalez H, Hagerling C, Werb Z. Roles of the immune system in cancer: from tumor initiation to metastatic progression. Genes Dev. (2018) 32:1267–84. doi: 10.1101/gad.314617.118

63. Heward JA, Lindsay MA. Long non-coding RNAs in the regulation of the immune response. Trends Immunol. (2014) 35:408–19. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.07.005

64. Ji J, Yin Y, Ju H, Xu X, Liu W, Fu Q, et al. Long non-coding RNA Lnc-Tim3 exacerbates CD8 T cell exhaustion via binding to Tim-3 and inducing nuclear translocation of Bat3 in HCC. Cell Death Dis. (2018) 9:478. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0528-7

65. Wu K, Zhao Z, Liu K, Zhang J, Li G, Wang L. Long noncoding RNA lnc-sox5 modulates CRC tumorigenesis by unbalancing tumor microenvironment. Cell Cycle. (2017) 16:1295–301. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2017.1317416

66. Togashi Y, Shitara K, Nishikawa H. Regulatory T cells in cancer immunosuppression - implications for anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2019). 16:356–71. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0175-7

67. Speiser DE, Ho PC, Verdeil G. Regulatory circuits of T cell function in cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. (2016) 16:599–611. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.80

68. Jiang R, Tang J, Chen Y, Deng L, Ji J, Xie Y, et al. The long noncoding RNA lnc-EGFR stimulates T-regulatory cells differentiation thus promoting hepatocellular carcinoma immune evasion. Nat Commun. (2017) 8:15129. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15129

69. Pei X, Wang X, Li H. LncRNA SNHG1 regulates the differentiation of Treg cells and affects the immune escape of breast cancer via regulating miR-448/IDO. Int J Biol Macromolecul. (2018) 118(Pt A):24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.06.033

70. Zemmour D, Pratama A, Loughhead SM, Mathis D, Benoist C. Flicr, a long noncoding RNA, modulates Foxp3 expression and autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2017) 114:E3472–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1700946114

71. Maas SLN, Breakefield XO, Weaver AM. Extracellular vesicles: unique intercellular delivery vehicles. Trends Cell Biol. (2017) 27:172–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.11.003

72. Qu L, Ding J, Chen C, Wu ZJ, Liu B, Gao Y, et al. Exosome-transmitted lncARSR promotes sunitinib resistance in renal cancer by acting as a competing endogenous RNA. Cancer Cell. (2016) 29:653–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.03.004

73. Zhou R, Chen KK, Zhang J, Xiao B, Huang Z, Ju C, et al. The decade of exosomal long RNA species: an emerging cancer antagonist. Molecul Cancer. (2018) 17:75. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0823-z

74. Whiteside TL. Tumor-derived exosomes and their role in cancer progression. Adv Clin Chem. (2016) 74:103–41. doi: 10.1016/bs.acc.2015.12.005

75. Teng Y, Ren Y, Hu X, Mu J, Samykutty A, Zhuang X, et al. MVP-mediated exosomal sorting of miR-193a promotes colon cancer progression. Nat Commun. (2017) 8:14448. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14448

76. Fan Q, Yang L, Zhang X, Peng X, Wei S, Su D, et al. The emerging role of exosome-derived non-coding RNAs in cancer biology. Cancer Lett. (2018) 414:107–15. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.10.040

77. Conigliaro A, Costa V, Lo Dico A, Saieva L, Buccheri S, Dieli F, et al. CD90+ liver cancer cells modulate endothelial cell phenotype through the release of exosomes containing H19 lncRNA. Molecul Cancer. (2015) 14:155. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0426-x

78. Ma X, Li Z, Li T, Zhu L, Li Z, Tian N. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR enhances angiogenesis by induction of VEGFA expression in glioma cells and transmission to endothelial cells via glioma cell derived-extracellular vesicles. Am J Transl Res. (2017) 9:5012–21.

79. Li X, Lei Y, Wu M, Li N. Regulation of macrophage activation and polarization by HCC-derived exosomal lncRNA TUC339. Int J Molecul Sci. (2018) 19:E2958. doi: 10.3390/ijms19102958

80. Li B, Xu H, Han H, Song S, Zhang X, Ouyang L, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of lncRUNX2-AS1 from multiple myeloma cells to MSCs contributes to osteogenesis. Oncogene. (2018) 37:5508–19. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0359-0

81. Lin C, Yang L. Long noncoding RNA in cancer: wiring signaling circuitry. Trends Cell Biol. (2018) 28:287–301. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.11.008

82. Evans JR, Feng FY, Chinnaiyan AM. The bright side of dark matter: lncRNAs in cancer. J Clin Invest. (2016) 126:2775–82. doi: 10.1172/JCI84421

83. Prensner JR, Chinnaiyan AM. The emergence of lncRNAs in cancer biology. Cancer Discov. (2011) 1:391–407. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0209

84. Fatica A, Bozzoni I. Long non-coding RNAs: new players in cell differentiation and development. Nat Rev Genet. (2014) 15:7–21. doi: 10.1038/nrg3606

85. Huarte M. The emerging role of lncRNAs in cancer. Nat Med. (2015) 21:1253–61. doi: 10.1038/nm.3981

86. Parasramka MA, Maji S, Matsuda A, Yan IK, Patel T. Long non-coding RNAs as novel targets for therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Pharmacol Therapeut. (2016) 161:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.03.004

87. Chen L, Dzakah EE, Shan G. Targetable long non-coding RNAs in cancer treatments. Cancer Lett. (2018) 418:119–24. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.01.042

88. Tan SK, Pastori C, Penas C, Komotar RJ, Ivan ME, Wahlestedt C, et al. Serum long noncoding RNA HOTAIR as a novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in glioblastoma multiforme. Molecul Cancer. (2018) 17:74. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0822-0

89. Lin LY, Yang L, Zeng Q, Wang L, Chen ML, Zhao ZH, et al. Tumor-originated exosomal lncUEGC1 as a circulating biomarker for early-stage gastric cancer. Molecul Cancer. (2018) 17:84. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0834-9

90. Zhao R, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Yang Y, Zheng X, Li X, et al. Exosomal long noncoding RNA HOTTIP as potential novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarker test for gastric cancer. Molecul Cancer. (2018) 17:68. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0817-x

91. Schmitt AM, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs in cancer pathways. Cancer Cell. (2016) 29:452–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.03.010

92. Cabili MN, Trapnell C, Goff L, Koziol M, Tazon-Vega B, Regev A, et al. Integrative annotation of human large intergenic noncoding RNAs reveals global properties and specific subclasses. Genes Dev. (2011) 25:1915–27. doi: 10.1101/gad.17446611

93. Buller HR, Bethune C, Bhanot S, Gailani D, Monia BP, Raskob GE, et al. Factor XI antisense oligonucleotide for prevention of venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med. (2015) 372:232–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1405760

94. Gaudet D, Brisson D, Tremblay K, Alexander VJ, Singleton W, Hughes SG, et al. Targeting APOC3 in the familial chylomicronemia syndrome. N Engl J Med.. (2014) 371:2200–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1400284

95. Hong D, Kurzrock R, Kim Y, Woessner R, Younes A, Nemunaitis J, et al. AZD9150, a next-generation antisense oligonucleotide inhibitor of STAT3 with early evidence of clinical activity in lymphoma and lung cancer. Sci Transl Med. (2015) 7:314ra185. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac5272

96. Meng L, Ward AJ, Chun S, Bennett CF, Beaudet AL, Rigo F. Towards a therapy for Angelman syndrome by targeting a long non-coding RNA. Nature. (2015) 518:409–12. doi: 10.1038/nature13975

97. Ling H, Fabbri M, Calin GA. MicroRNAs and other non-coding RNAs as targets for anticancer drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2013) 12:847–65. doi: 10.1038/nrd4140

98. Arun G, Diermeier S, Akerman M, Chang KC, Wilkinson JE, Hearn S, et al. Differentiation of mammary tumors and reduction in metastasis upon Malat1 lncRNA loss. Genes Dev. (2016) 30:34–51. doi: 10.1101/gad.270959.115

99. Gutschner T, Hammerle M, Eissmann M, Hsu J, Kim Y, Hung G, et al. The noncoding RNA MALAT1 is a critical regulator of the metastasis phenotype of lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. (2013) 73:1180–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2850

100. Vickers TA, Koo S, Bennett CF, Crooke ST, Dean NM, Baker BF. Efficient reduction of target RNAs by small interfering RNA and RNase H-dependent antisense agents. A comparative analysis. J Biol Chem. (2003) 278:7108–18. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210326200

101. Petrocca F, Altschuler G, Tan SM, Mendillo ML, Yan H, Jerry DJ, et al. A genome-wide siRNA screen identifies proteasome addiction as a vulnerability of basal-like triple-negative breast cancer cells. Cancer Cell. (2013) 24:182–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.07.008

102. Morrissey DV, Lockridge JA, Shaw L, Blanchard K, Jensen K, Breen W, et al. Potent and persistent in vivo anti-HBV activity of chemically modified siRNAs. Nat Biotechnol. (2005) 23:1002–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt1122

103. Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings HM, Wong DJ, et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature. (2010) 464:1071–6. doi: 10.1038/nature08975

104. Ren S, Liu Y, Xu W, Sun Y, Lu J, Wang F, et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT-1 is a new potential therapeutic target for castration resistant prostate cancer. J Urol. (2013) 190:2278–87. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.07.001

105. Endo H, Shiroki T, Nakagawa T, Yokoyama M, Tamai K, Yamanami H, et al. Enhanced expression of long non-coding RNA HOTAIR is associated with the development of gastric cancer. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e77070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077070

106. Ayatollahi S, Salmasi Z, Hashemi M, Askarian S, Oskuee RK, Abnous K, et al. Aptamer-targeted delivery of Bcl-xL shRNA using alkyl modified PAMAM dendrimers into lung cancer cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. (2017) 92:210–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.10.005

107. Wilusz JE, JnBaptiste CK, Lu LY, Kuhn CD, Joshua-Tor L, Sharp PA. A triple helix stabilizes the 3' ends of long noncoding RNAs that lack poly(A) tails. Genes Dev. (2012) 26:2392–407. doi: 10.1101/gad.204438.112

108. Brown JA, Bulkley D, Wang J, Valenstein ML, Yario TA, Steitz TA, et al. Structural insights into the stabilization of MALAT1 noncoding RNA by a bipartite triple helix. Nat Struct Molecul Biol. (2014) 21:633–40. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2844

109. Zhang B, Mao YS, Diermeier SD, Novikova IV, Nawrocki EP, Jones TA, et al. Identification and Characterization of a Class of MALAT1-like Genomic Loci. Cell Rep. (2017) 19:1723–38. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.006

Keywords: long non-coding RNA, tumor microenvironment, stromal cells, exosomes, therapy

Citation: Chen D, Lu T, Tan J, Li H, Wang Q and Wei L (2019) Long Non-coding RNAs as Communicators and Mediators Between the Tumor Microenvironment and Cancer Cells. Front. Oncol. 9:739. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00739

Received: 09 May 2019; Accepted: 23 July 2019;

Published: 06 August 2019.

Edited by:

Cecilia Ana Suarez, National Council for Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET), ArgentinaReviewed by:

Xingming Jiang, Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, ChinaCopyright © 2019 Chen, Lu, Tan, Li, Wang and Wei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Liangzhou Wei, d2VpbGlhbmd6aG91NjJAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.