- 1Department of Neurology, Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Nagoya, Japan

- 2The Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology and Radiological Science, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 3Department of Integrated Health Sciences, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya, Japan

- 4Department of Radiology, National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology, Ōbu, Japan

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia and a distressing diagnosis for individuals and caregivers. Researchers and clinical trials have mainly focused on β-amyloid plaques, which are hypothesized to be one of the most important factors for neurodegeneration in AD. Meanwhile, recent clinicopathological and radiological studies have shown closer associations of tau pathology rather than β-amyloid pathology with the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s symptoms. Toward a biological definition of biomarker-based research framework for AD, the 2018 National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association working group has updated the ATN classification system for stratifying disease status in accordance with relevant pathological biomarker profiles, such as cerebral β-amyloid deposition, hyperphosphorylated tau, and neurodegeneration. In addition, altered iron metabolism has been considered to interact with abnormal proteins related to AD pathology thorough generating oxidative stress, as some prior histochemical and histopathological studies supported this iron-mediated pathomechanism. Quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) has recently become more popular as a non-invasive magnetic resonance technique to quantify local tissue susceptibility with high spatial resolution, which is sensitive to the presence of iron. The association of cerebral susceptibility values with other pathological biomarkers for AD has been investigated using various QSM techniques; however, direct evidence of these associations remains elusive. In this review, we first briefly describe the principles of QSM. Second, we focus on a large variety of QSM applications, ranging from common applications, such as cerebral iron deposition, to more recent applications, such as the assessment of impaired myelination, quantification of venous oxygen saturation, and measurement of blood– brain barrier function in clinical settings for AD. Third, we mention the relationships among QSM, established biomarkers, and cognitive performance in AD. Finally, we discuss the role of QSM as an imaging biomarker as well as the expectations and limitations of clinically useful diagnostic and therapeutic implications for AD.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia (Scheltens et al., 2016). The pathological hallmarks include deposition of extracellular β-amyloid (Aβ) aggregates as senile plaques and intracellular hyperphosphorylated tau aggregates as neurofibrillary tangles, along with neuronal loss and glial activation (Serrano-Pozo et al., 2011). Over a long period, researchers and clinical trials have mainly focused on Aβ pathology, which is hypothesized to be one of the most important factors in AD pathogenesis. However, recent clinicopathological and radiological data suggest that tau pathology, not Aβ pathology, closely links with onset and progression of Alzheimer’s symptoms (Brier et al., 2016; Aillaud and Funke, 2022) though the relationship and interplay between Aβ and tau pathologies remain controversial (Pourhamzeh et al., 2021). Toward a biological definition of biomarker-based research framework for AD, the 2018 National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association working group has updated the ATN classification system (Jack et al., 2018), whose measures have different roles for definition and staging: A: Aβ biomarkers determine whether an individual is in the Alzheimer’s continuum; T: pathological tau biomarkers determine if an individual in the Alzheimer’s continuum has AD; and N: neurodegenerative biomarkers determine the staging severity of the Alzheimer’s continuum.

In addition to these traditional pathological features, iron deposition has attracted the attention of researchers as a new biomarker reflecting disease severity in AD. Histochemical and histopathological studies have shown evidence of altered iron metabolism and accumulation in AD brain tissues, with iron colocalizing in senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (Tao et al., 2014). These abnormal proteins bind ferric iron and reduce it to the redox-active form, ferrous iron, which reacts with hydrogen peroxide to generate hydroxyl radicals, leading to the ferroptosis pathway (Sayre et al., 2000; Everett et al., 2014; Conrad et al., 2016). Studies in animal models of AD have reported that brain iron chelation can abolish this iron-mediated pathomechanism, reducing downstream oxidative stress and neurofibrillary tangle formation (Smith et al., 1997; Guo C. et al., 2013). Therefore, iron may have a synergistic role with Aβ and tau proteins in key pathophysiological processes leading to AD pathogenesis.

Using advanced imaging techniques, human subjects were investigated in vivo to determine whether their brain iron levels would be altered. Quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) has recently become more popular as a non-invasive magnetic resonance technique with which to quantify local tissue susceptibility with high spatial resolution; this technique is sensitive to the presence of iron (Liu et al., 2009; Shmueli et al., 2009; de Rochefort et al., 2010). In this review, we focused on the associations of established pathological biomarkers for AD with cerebral iron deposition using a conventional QSM technique, as well as more complicated QSM applications, such as an assessment of impaired myelination, quantification of venous oxygen saturation, and measurement of blood–brain barrier function in clinical settings for AD.

Principles of quantitative susceptibility mapping

History of quantitative susceptibility mapping

Magnetic susceptibility between tissues has been utilized as a new type of contrast in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which differs from proton density, T1-, and T2-weighted imaging. The phase signals from materials with different magnetic susceptibilities compared with their neighboring tissues are formed by dipole interactions. The phase image itself is unavailable without post-processing for phase unwrapping, which is performed to deconvolute the dynamic range of −π to π, and background field removal for susceptibility differences at tissue-air boundaries. Thus, phase imaging provides a unique contrast between gray matter, white matter, iron-laden tissues, venous blood vessels, and other tissues with biologically specific magnetic susceptibilities that differ from those of background tissues (Liu et al., 2009; Shmueli et al., 2009; de Rochefort et al., 2010). Susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) is a precursor post-processing technique for QSM that uses the phase as a means of enhancing susceptibility differences (Haacke et al., 2004). Since its development in the mid-1990s (Haacke et al., 1995), SWI has been used in diverse clinical settings, such as in the identification of cerebral microbleeds (Akter et al., 2007; Greenberg et al., 2009; Barnes et al., 2011; Goos et al., 2011; Cheng et al., 2013; Guo L. F. et al., 2013; Linn, 2015; Shams et al., 2015), acute ischemic stroke (Hermier and Nighoghossian, 2004; Tong et al., 2008; Santhosh et al., 2009; Tsui et al., 2009; Chalian et al., 2011; Kesavadas et al., 2011; Baik et al., 2012; Kao et al., 2012; Fujioka et al., 2013; Lou et al., 2014; Meoded et al., 2014; Verma et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2015), vascular malformations (Essig et al., 1999; Choi and Mohr, 2005; Jagadeesan et al., 2011), and magnetic resonance venography (Reichenbach et al., 1997, 1998, 2001; Reichenbach and Haacke, 2001; Neelavalli et al., 2014). However, these approaches are qualitative in nature as SWI is calculated by the summation of magnitude and homodyne-filtered phase signals (Liu et al., 2017). This limitation is currently being addressed with the development of the QSM technique (Liu et al., 2015), which provides a quantitative measure of magnetic susceptibility and has been useful for statistical image analyses (Eskreis-Winkler et al., 2017).

Acquisition and reconstruction protocols for quantitative susceptibility mapping

A 3D gradient-recalled echo sequence with full flow compensation is generally used to acquire QSM data, as this sequence can account for the flow-induced phase shift and capture reliable phase information (Schenck, 1996; Xu et al., 2014). The properties of the gradient echo signal phase images produced by a clinical 3 Tesla MRI scanner are highly dependent on the imaging parameters (Haacke et al., 2015). Multiple echo sequences can acquire phase data more effectively than single-echo sequences. The phase value is dependent on the frequency map and echo time, and it achieves optimal phase contrast and maximal signal-to-noise ratios when the echo time is equal to the T2* value on a specific pixel (Wu et al., 2012). As the optimal echo time is usually different in various tissue types due to the variety of T2* values, it is necessary to combine the frequency map at each echo time based on the weighted averages of the T2* values. The parallel imaging technique is turned on to reduce the scan time as long as the magnitude and phase images are properly reconstructed (Vinayagamani et al., 2021). A high-resolution whole-brain acquisition of 6–12 min is typically implemented. Low spatial resolution and small brain coverage worsen the accuracy of susceptibility values (Karsa et al., 2019).

Susceptibility map reconstruction consists of several post-processing steps, which include phase unwrapping, background field removal, and dipole inversion. As the phase data are limited to the dynamic range from −π to π, a phase unwrapping algorithm is required to calculate the frequency map (i.e., total field map) (Robinson et al., 2017; Karsa and Shmueli, 2019). Then, the background field caused by the air-tissue interface is removed from the total field map to separate the tissue-generated field map (Liu T. et al., 2011; Sun and Wilman, 2014; Zhou et al., 2014; Kan et al., 2016, 2018; Özbay et al., 2017). The susceptibility map is finally reconstructed from the tissue-generated field map using dipole inversion processing (Liu et al., 2009; de Rochefort et al., 2010; Wharton et al., 2010; Wei et al., 2015; Liu Z. et al., 2018; Polak et al., 2020). The mean susceptibility value of the cerebrospinal fluid in the lateral ventricles is usually defined as a zero reference, given that it is essentially water and contains negligible iron (LeVine et al., 1998; Haacke et al., 2015).

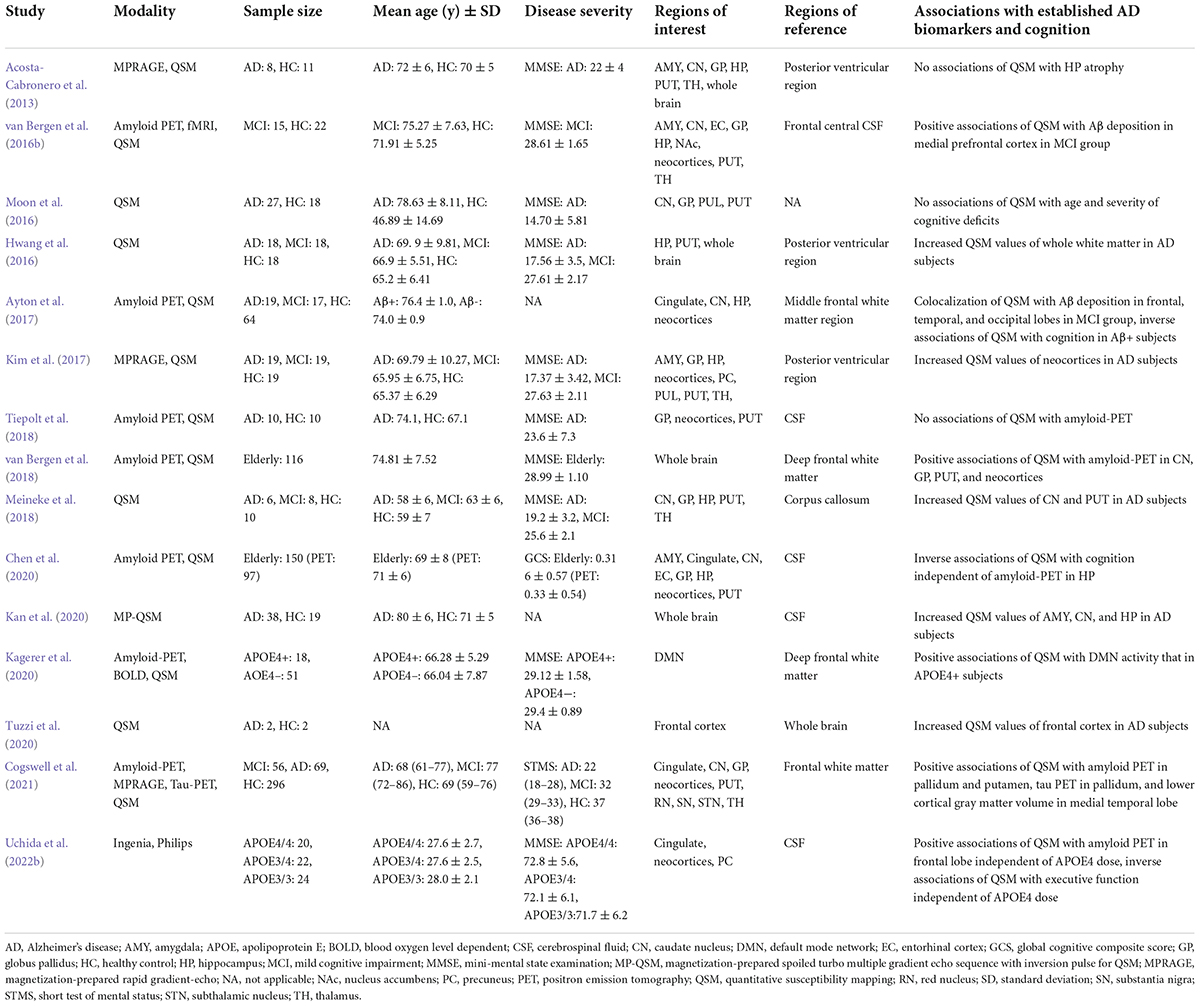

Based on the concept described above, we adopt a gradient echo sequence with the following parameters from our previous study (Uchida et al., 2019): number of echoes: 5; minimal first echo time: 6.4 ms; Δ echo time: 6.4 ms; repetition time: 36 ms, flip angle: 15; field of view: 192 × 192 × 160 mm3; matrix: 192 × 192; and slice thickness: 1 mm, yielding an iso-voxel resolution of 1 mm3 on a 3 Tesla MRI scanner. The QSM reconstruction algorithm includes the Laplacian-based algorithm (Bagher-Ebadian et al., 2008), variable-kernel sophisticated harmonic artifact reduction for phase data to remove the background field owing to the existence of an air–tissue interface (Kan et al., 2016, 2018; Özbay et al., 2017), and improved sparse linear equations and least-squares techniques (Li et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2015). Note that different approaches have been proposed for each post-processing step, which influences the accuracy of the magnetic susceptibility values and the edge of the brain mask (Haacke et al., 2015). Details of MRI acquisition parameters and postprocessing techniques in QSM studies for AD continuum subjects are summarized in Table 1 (Acosta-Cabronero et al., 2013; Hwang et al., 2016; Moon et al., 2016; van Bergen et al., 2016b,2018; Ayton et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2017; Meineke et al., 2018; Tiepolt et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2020; Kagerer et al., 2020; Kan et al., 2020; Tuzzi et al., 2020; Cogswell et al., 2021; Ravanfar et al., 2021; Uchida et al., 2022b).

Table 1. Overview of MRI acquisition parameters and postprocessing techniques in QSM studies for AD continuum subjects.

Clinical applications of quantitative susceptibility mapping

Quantification of iron content

Quantifying tissue iron concentration in vivo is the best clinical application of QSM to understand the role of iron in the pathophysiology of neurological diseases associated with abnormal iron distribution. The mean susceptibilities of the bulk tissue in deep gray matter nuclei have been validated using total iron content ex vivo or in vitro and measured using various modalities, including synchrotron X-ray fluorescence iron mapping (Zheng et al., 2012, 2013), atomic absorption spectrometry (House et al., 2007), and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (Langkammer et al., 2010, 2012b). The challenge is that the estimation of iron concentration in white matter regions is less accurate and more complex due to the counteracting contribution from diamagnetic myelinated neuronal fibers that confounds the interpretation (Langkammer et al., 2012a). Another challenge is the estimation of age-related iron changes in deep gray matter nuclei and myelin changes in white matter regions (Bilgic et al., 2012; Keuken et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018; Ning et al., 2019). In order to draw any conclusions regarding the presence of abnormal iron accumulation, it will be necessary to know the range and variation of normal susceptibilities for all ages. A 4D developmental QSM atlas serves as a template for studying brain iron deposition and myelination/demyelination during normal aging and in various brain diseases (Zhang et al., 2018).

Assessment of myelination

Evaluating white matter alterations in the AD brain, in addition to gray matter alterations, has been of great interest. The magnetic susceptibility of white matter is mainly influenced by iron and myelin components (Shmueli et al., 2009; Haacke et al., 2010). Human brain myelination changes over the entire lifespan (Lebel et al., 2012); it is prominent in the brain development that occurs during early life (Deoni et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2018), in the normal aging processes that occur later in life (Lee et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2018), and during pathological demyelination (Liu C. et al., 2011; Langkammer et al., 2013; Cao et al., 2014). As white matter fiber bundles are myelinated, susceptibility values are more diamagnetic (Li et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2018). Therefore, QSM provides valuable information regarding the temporal and spatial patterns of brain myelination and demyelination. Further research is warranted to quantify the changes in myelin content in various physiological and pathological conditions such as brain development, aging, neurodegenerative diseases, and demyelinating diseases (Vinayagamani et al., 2021).

Measuring venous oxygen saturation

In addition to gray and white matter structures, blood vessels in the brain are also key factors in AD pathogenesis. Close monitoring of central venous oxygenation serves as a novel biomarker for studying cerebral hemodynamics (Eskreis-Winkler et al., 2017), which can aid in understanding the pathophysiology of vascular disorders in which blood oxygen supply is impaired. Differential diagnosis between AD and vascular cognitive impairment is quite difficult because their pathophysiologies are overlapped as well as their concurrence. Brain oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) is differentially altered by AD and vascular cognitive impairment (Jiang et al., 2020). QSM has recently been used to measure venous oxygen saturation; hence, the cerebral metabolic rate for oxygen and OEF can be calculated (Gauthier and Hoge, 2012; Fan et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015; Kudo et al., 2016; Uchida et al., 2022a). Briefly, the OEF calculation from the QSM is expressed as follows:

where Δχ is the susceptibility difference between the vein and surrounding brain tissue, Δχdo is the difference in susceptibility per unit of hematocrit between fully deoxygenated and fully oxygenated blood, Hct is each subject’s hematocrit, and Pv is a correction factor for the partial volume effects that was defined based on the simulated calculation (Kudo et al., 2016). Rapid acquisition of magnetic susceptibility and evaluation of venous oxygen saturation can aid in the determination of predictors for progressive ischemic regions in urgent care settings (Kan et al., 2017, 2019). QSM-derived OEF map shows the area of the penumbra as an indicator of brain cell viability. It has been reported that brain tissues with increased OEF values can predict ischemic penumbral tissues based on diffusion-perfusion mismatch areas defined by a dynamic susceptibility contrast (Uchida et al., 2022a).

Biomarker for neurodegenerative diseases

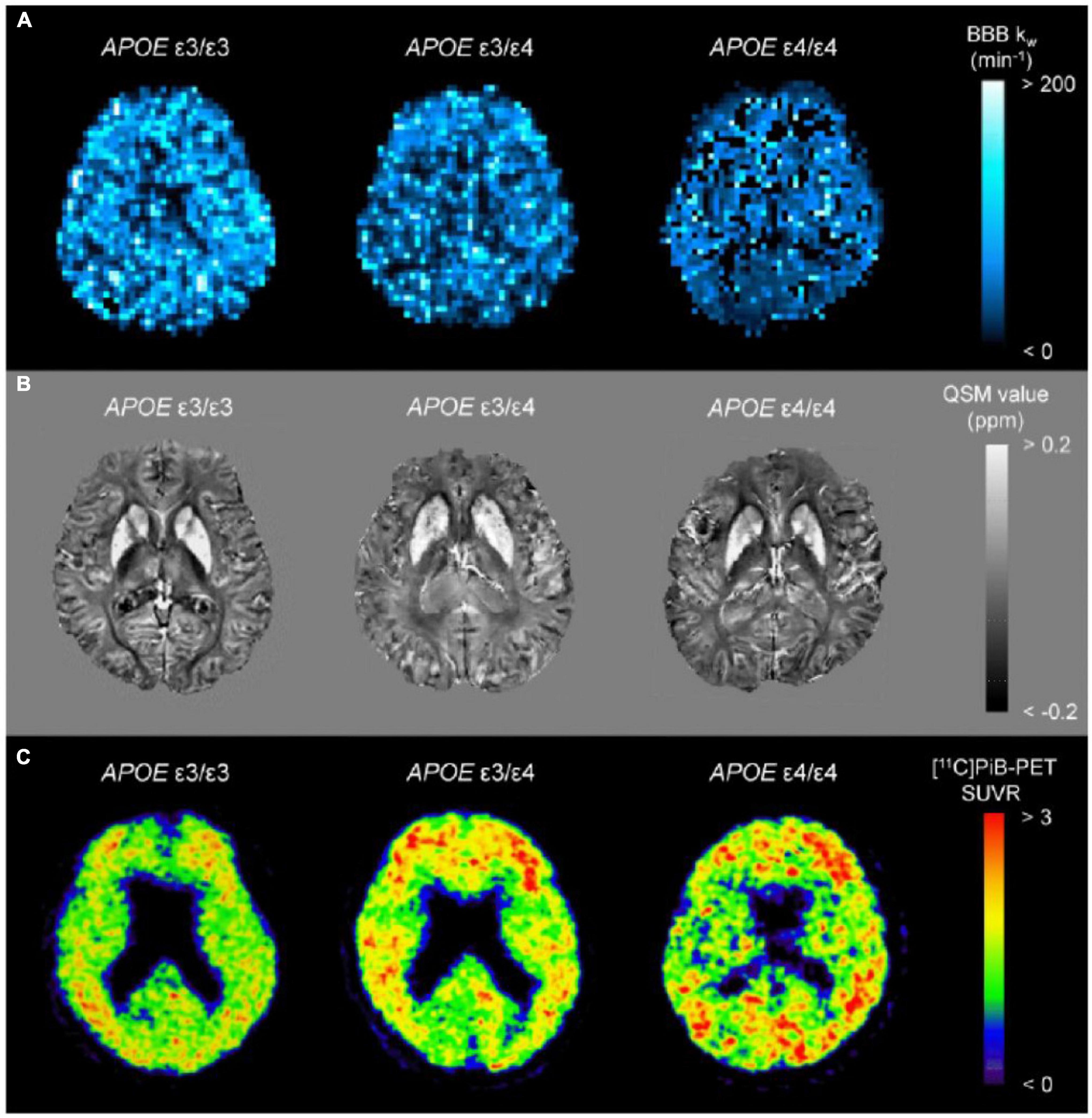

Brain iron accumulation has been proposed as one of the pathomechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease (Langkammer et al., 2016; Acosta-Cabronero et al., 2017; Uchida et al., 2019, 2020b), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Kwan et al., 2012; Acosta-Cabronero et al., 2018a), Huntington’s disease (Domínguez et al., 2016; van Bergen et al., 2016a), and AD (Acosta-Cabronero et al., 2013; Ayton et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2017; Tiepolt et al., 2018; Gong et al., 2019; Cogswell et al., 2021). QSM can be used to detect abnormal iron deposits in specific affected regions of neurodegenerative diseases, such as in the nigrostriatal system for Parkinson’s disease, the motor cortex for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, the basal ganglia for Huntington’s disease, and limbic system for AD. Although abnormally high levels of iron are thought to induce free radicals resulting in neuronal loss and clinical symptoms, whether iron deposition is a cause or a result of neurodegeneration remains elusive. The former is supported by clinicoradiological studies revealing iron leakage owing to blood–brain barrier disruption in small vessel diseases (Mikati et al., 2014; Tariq et al., 2018; Uchida et al., 2020a) and subtle blood–brain barrier dysfunction in early stages of Alzheimer’s continuum with the ε4 allele of APOE gene (Figure 1; Yamanaka et al., 2019).

Figure 1. Representative images from BBB kw map (A), QSM (B), and [11C]PiB-PET SUVR (C) from a APOE ε4 non-carrier (ε3/ε3), a heterozygote (ε3/ε4), and a homozygote (ε4/ε4). The kw map from the homozygote (ε4/ε4) displays the lowest kw values, which are associated with increased SUVRs of [11C]PiB-PET. On the other hand, there were indiscernible differences for QSM among the groups. BBB, blood–brain barrier; PiB, Pittsburgh compound B; QSM, quantitative susceptibility mapping; SUVR, standard uptake value ratio (adapted with permission from Uchida et al., 2022b).

Relationship between quantitative susceptibility mapping and Alzheimer’s disease pathology

Altered iron metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis

Altered iron metabolism has been hypothesized to be associated with the pathogenesis of AD (Ayton et al., 2015). Histochemical and histopathological studies have shown evidence of altered iron metabolism and accumulation in AD brain tissues, with iron colocalizing with Aβ aggregates as senile plaques and intracellular hyperphosphorylated tau aggregates as neurofibrillary tangles (Aillaud and Funke, 2022). QSM has been used to study the relationships between cerebral iron load and established biomarkers for AD (Acosta-Cabronero et al., 2013; Ayton et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2017; Tiepolt et al., 2018; Gong et al., 2019; Cogswell et al., 2021). Overall, these findings suggest that magnetic susceptibility in deep gray matter may be a biomarker for AD pathogenesis. Meanwhile, the sensitivity of QSM for the cerebral cortices is insufficient for reliable detection. This is partly due to superficially eroded masking applied and noise levels, such as adjacent to vessels or edges of the brain mask. An advanced multi-scale approach to QSM can improve the ability to detect susceptibility values in the cerebral cortices (Acosta-Cabronero et al., 2018b).

Association of quantitative susceptibility mapping with Aβ pathology

Senile plaques, which are pathological aggregates of extracellular Aβ proteins, contain iron (Lovell et al., 1998). In an amyloid mouse model of AD, magnetic susceptibility increased over time relative to controls in a longitudinal study, which used a linear mixed effects modeling analysis that incorporated estimates from multiple brain regions (Klohs et al., 2013). Notably, Aβ itself has slightly diamagnetic susceptibility in a phantom experiment (−0.024 to −0.019 ppm) (Gong et al., 2019). Paramagnetic source of β-amyloid plaques in vivo is largely attributed to focal iron deposition (Jack et al., 2004). Accordingly, QSM, which is sensitive to the concentration of iron in brain tissues, may play a key role in tracking the progressive pathology of AD and provide a means to measure the efficacy of iron chelation therapy (Crapper McLachlan et al., 1991; Dixon et al., 2012; Liu J. L. et al., 2018; Cummings et al., 2019).

Association of quantitative susceptibility mapping with tau pathology

Neurofibrillary tangles, which are pathological insoluble aggregates of hyperphosphorylated tau proteins, also contain iron (Good et al., 1992). Susceptibility values of tau protein are diamagnetic as well as Aβ and variable due to echo time (−0.071 to −0.037 ppm) (Gong et al., 2019). In animal models of tau pathology, reactive microglia and astrocytes have been reported to induce neuroinflammation and iron accumulation (Yoshiyama et al., 2007; Maphis et al., 2015). Therefore, QSM may be a sensitive in vivo biomarker for these pathological traits. In an analogous model of tau pathology, semi-automatic segmentation of QSM was employed to calculate magnetic susceptibility in gray matter and white matter regions, and it might be useful for detecting early tau pathological changes (O’Callaghan et al., 2017). These QSM protocols could be incorporated into clinical protocols for human AD and other tauopathies that are currently ongoing.

Association of quantitative susceptibility mapping with neurodegeneration

Based on the ATN system (Jack et al., 2018), biomarkers of neurodegeneration (labeled “N”) include structural MRI, positron emission tomography (PET) with 2-deoxy-2-[fluorine-18]fluoro-D-glucose (18F-FDG-PET), and cerebrospinal fluid total tau proteins. In terms of associations between QSM and structural MRI, voxel-based QSM analyses revealed increased susceptibilities of the hippocampus in patients with AD compared to age-matched cognitively normal controls (Acosta-Cabronero et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2017; Kan et al., 2020), whereas voxel-based morphometry revealed atrophic changes of the hippocampus (Matsuda, 2016; Kan et al., 2020). Additionally, a longitudinal study of cognitively normal adults showed that accumulation of iron in the putamen could predict its shrinkage (Daugherty and Raz, 2016). Although less investigated for associations between QSM and the other biomarkers of neurodegeneration, a combined 18F-FDG-PET and QSM study in different AD cohorts revealed glucose hypometabolism and brain iron accumulation in the hippocampus, temporal, and parietal lobes (Rao et al., 2022).

Association of quantitative susceptibility mapping with cognitive decline

Approximately 10–40% of cognitively normal older individuals have evidence of cerebral Aβ deposition (Jansen et al., 2015), which suggests that Aβ alone may not be sufficient for the development of AD symptoms. Histopathological studies have proposed that Aβ and iron colocalize and act synergistically to affect downstream AD pathogenesis (Smith et al., 1997; Gong et al., 2019). Biochemically, Aβ and tau proteins bind ferric iron and reduce it to its redox-active form, ferrous iron, which reacts with hydrogen peroxide to generate reactive oxygen species that lead to ferroptosis pathway (Sayre et al., 2000; Everett et al., 2014; Conrad et al., 2016). Furthermore, a number of clinicoradiological studies emphasize cerebral iron accumulation combined with Aβ and tau proteins to accelerate cognitive decline (van Bergen et al., 2016b; Ayton et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2017; Tiepolt et al., 2018). However, recent whole-brain analyses of QSM with amyloid and tau PET have revealed contradictory evidence, with each pathologic substrate arising independently and in spatially different areas (Cogswell et al., 2021). In voxel-based QSM and amyloid PET analyses, there were clusters in which iron levels were negatively correlated with Aβ deposits, some of which were associated with global cognition (Chen et al., 2020). Further investigations regarding the interactions among iron, Aβ and tau proteins, and cognitive dysfunction are warranted, along with longitudinal studies to determine whether QSM can predict cognitive decline in patients with early stage AD.

Association of quantitative susceptibility mapping with white matter alteration

Normal white matter regions have negative magnetic susceptibilities due to the presence of myelin, with reference to the cerebrospinal fluid in the ventricle (Wisnieff et al., 2015). Alterations in the magnetic susceptibility of white matter lesions depend on various pathophysiological conditions, including demyelination, ischemia, and expansion of the perivascular space (Sjöbeck et al., 2005). Magnetic susceptibility measurements in white matter using QSM have been shown to be more specifically related to myelin concentration than diffusion tensor imaging (Argyridis et al., 2014). A voxel-based QSM comparison of the whole brain between patients with AD and age-matched cognitively normal controls revealed increased magnetic susceptibilities of the medial temporal lobes in the gray matter and the genu, body, and splenium of the corpus callosum in the white matter (Kan et al., 2020).

Role of quantitative susceptibility mapping as biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease

Alternative biomarker for positron emission tomography remains controversial

Several clinicoradiological studies have investigated the relationship between iron and Aβ deposition as detected using QSM and amyloid PET (van Bergen et al., 2016a,2018; Ayton et al., 2017; Tiepolt et al., 2018). However, these associations remain controversial, with one study showing no significant association in the cortices (Cogswell et al., 2021) and one that showed a positive or negative correlation that depended on the anatomical brain regions (Chen et al., 2020). In individuals with evidence of cerebral Aβ deposition, higher baseline hippocampal iron levels predict an accelerated longitudinal decline in episodic memory, executive dysfunction, and attention (Ayton et al., 2017).

Compared with amyloid PET, the association between QSM and tau PET has been less investigated. Although some studies have found positive correlations between magnetic susceptibility and tau PET standardized uptake value ratios in the basal ganglia and cortices (Choi et al., 2018; Spotorno et al., 2020; Cogswell et al., 2021), these associations were partly caused by off-target binding of tau PET ligands. Postmortem studies using multiple tau tracers have shown that off-target tau binding is secondary to monoamine oxidase and iron deposition in the presence of inflammation (Harada et al., 2018; Lemoine et al., 2018; Baker et al., 2019).

The extent of elevated magnetic susceptibility in QSM and standardized uptake value ratios in amyloid and tau PET do not overlap, which may imply that more complicated factors contribute to these signal changes. When the anterior hippocampus was segmented into seven layers using high-resolution ex vivo MRI, the molecular changes in Aβ and tau protein aggregations had specific effects on the magnetic susceptibilities of AD brain tissues (Zhao et al., 2021). However, layer-specific PET analysis is impractical due to its low resolution.

Expectations

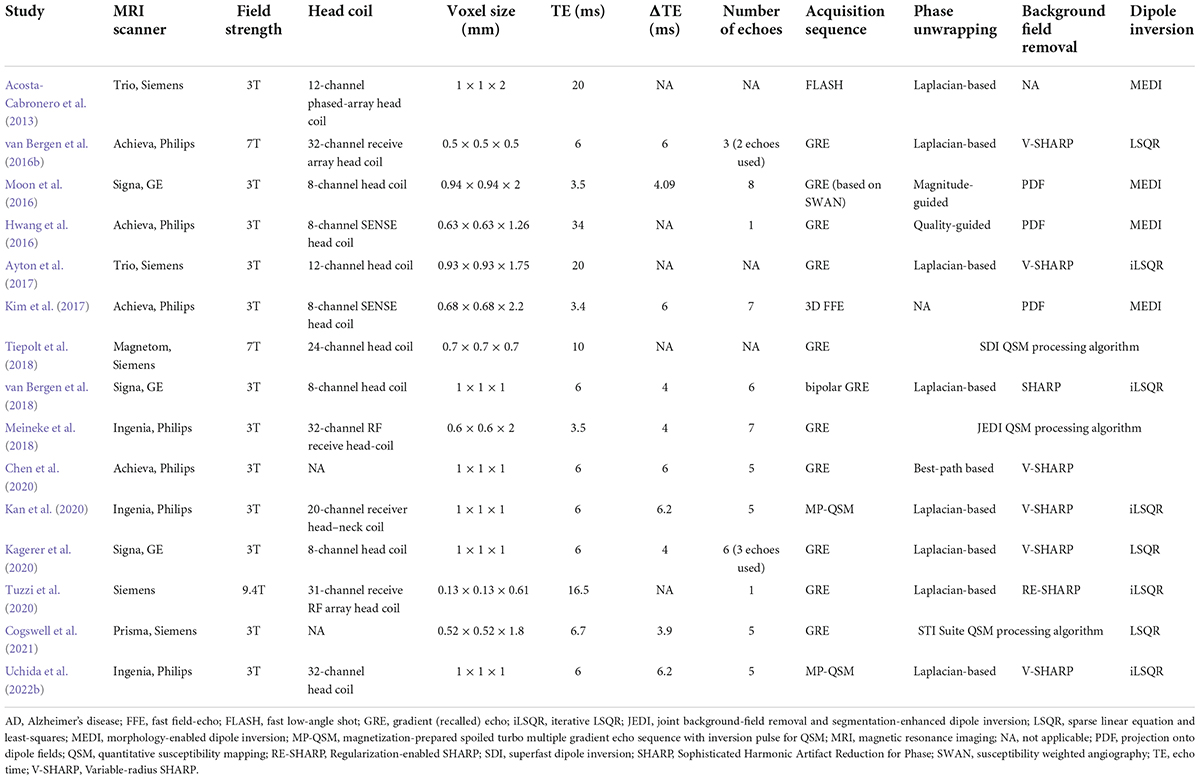

Numerous concomitant disease processes, including altered iron metabolism, contribute to AD pathogenesis. Proteins such as Aβ and tau that are associated with AD pathology are involved in molecular crosstalk with iron homeostatic proteins (Reed et al., 2009). Furthermore, lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress, hallmark features of ferroptosis, are considered an early event in AD pathogenesis (Praticò and Sung, 2004). From the viewpoint of these pathomechanisms related to perturbations in iron homeostasis, iron itself should be included as pathological biomarker for AD (Masaldan et al., 2019), in addition to the proposed ATN classification system (Jack et al., 2018). Taking account of its presence prior to Aβ and tau aggregates, the possibility of iron chelation therapy is implicated (Crapper McLachlan et al., 1991; Smith et al., 1997; Dixon et al., 2012; Guo C. et al., 2013). With current imaging techniques allowing for in vivo quantification of brain iron, Aβ, tau, and neurodegeneration, the efficacy of the disease modifying therapy on these AD pathologies could be more specifically monitored (Borlongan, 2012). An overview of QSM study design and main findings for AD continuum subjects are summarized in Table 2 (Acosta-Cabronero et al., 2013; Hwang et al., 2016; Moon et al., 2016; van Bergen et al., 2016b,2018; Ayton et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2017; Meineke et al., 2018; Tiepolt et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2020; Kagerer et al., 2020; Kan et al., 2020; Tuzzi et al., 2020; Cogswell et al., 2021; Ravanfar et al., 2021; Uchida et al., 2022b).

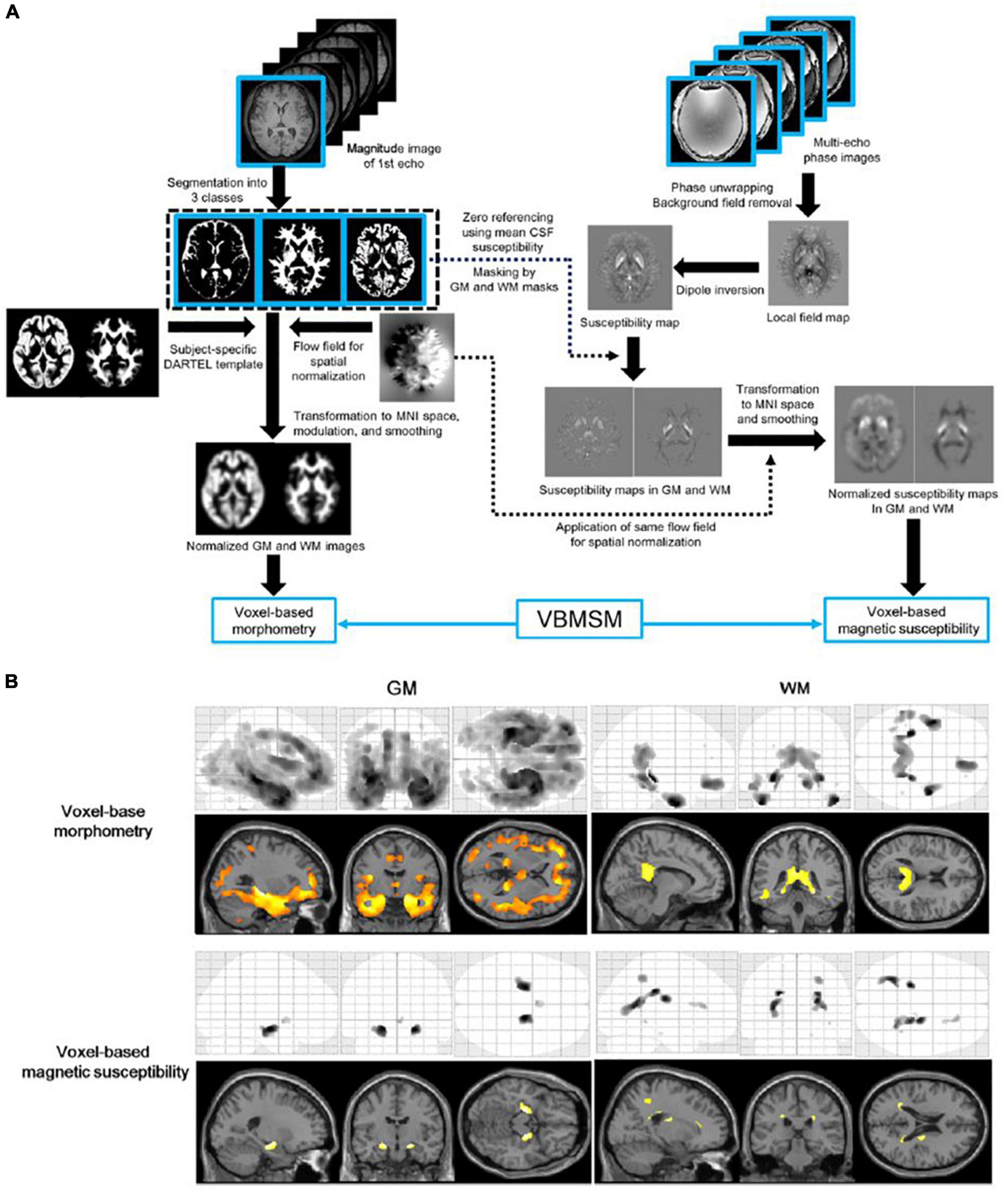

Voxel-based morphometry and QSM analyses are useful for mapping the landscape of whole-brain volume and magnetic susceptibility changes in patients with AD (Ashburner and Friston, 2000; Acosta-Cabronero et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2017). A magnetization-prepared spoiled turbo multiple gradient echo sequence has been developed to simultaneously acquire 3D T1-weighted structural and multi-echo phase images for voxel-based morphometry and QSM analyses (Kan et al., 2020). The key advantage of this technique is that any image registration between these images prior to spatial normalization is unnecessary, as these datasets have exactly the same geometry (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Diagram of voxel-based morphometry and magnetic susceptibility analyses (A) and results of the voxel-based analyses (B). The top of the left-hand panel shows the procedure of the voxel-based morphometry analysis. The top of the right-hand panel shows the procedures of the susceptibility estimation and spatial normalization of the map for the voxel-based magnetic susceptibility analysis. The bottom panel shows the results of voxel-based morphometry and magnetic susceptibility comparisons between elderly volunteers and patients with Alzheimer’s disease. A corrected P-value of < 0.05 with the family-wise error correction was applied as the threshold to detect regional volume decreases and susceptibility increases in the Alzheimer’s disease group. GM, gray matter; VBMSM, voxel-based magnetic susceptibility and morphometry; WM, white matter (adapted with permission from Kan et al., 2020).

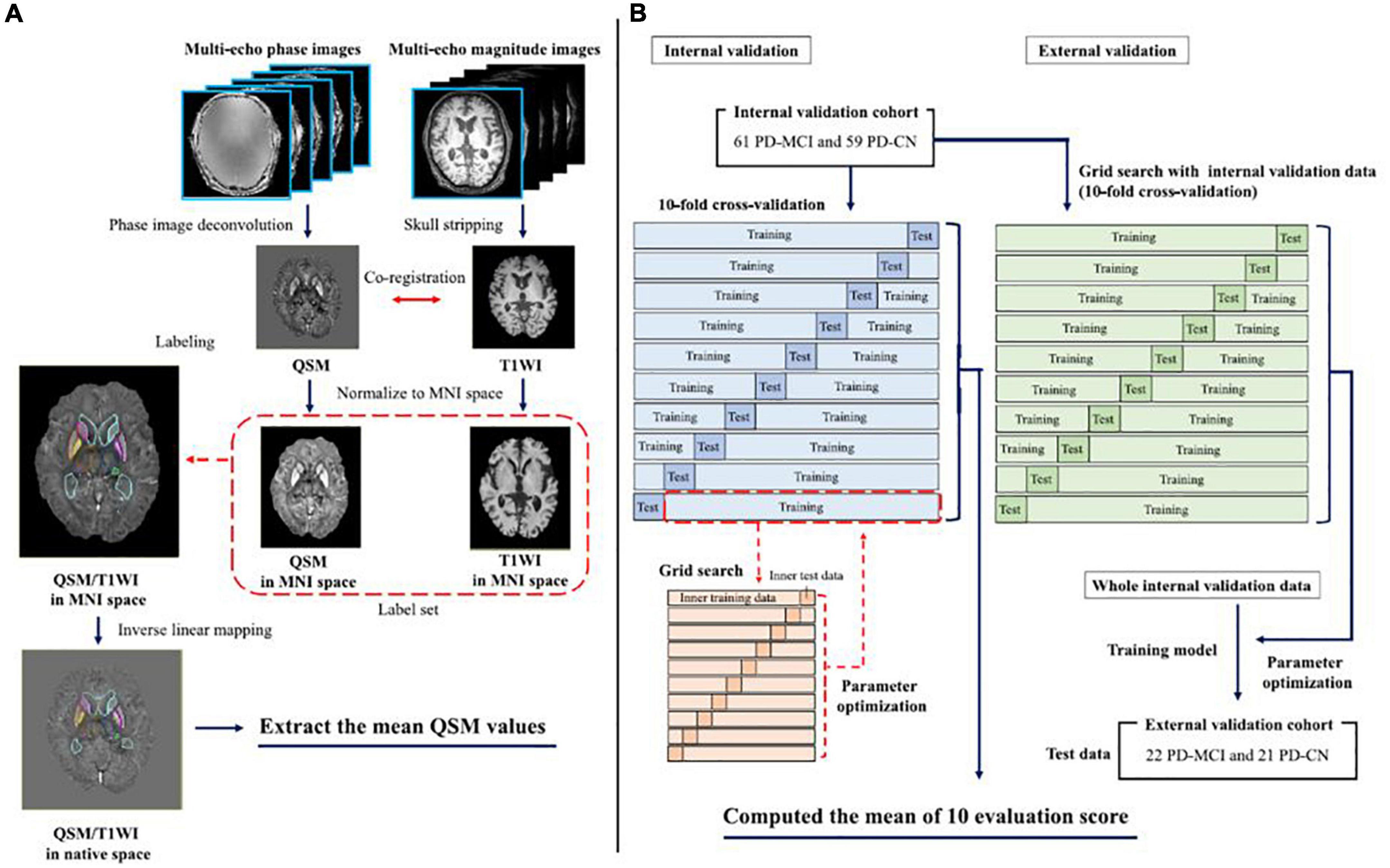

Atlas-based analysis, which can help generate universal and sharable susceptibility measures in a biologically meaningful set of anatomical structures, is also useful (Lim et al., 2013). Moreover, the multi-atlas label-fusion method for automated segmentation of QSM images has been developed as a more accurate quantification tool for determining the magnetic susceptibilities of individuals (Li et al., 2019). Figure 3 shows a machine learning model trained with the extracted magnetic susceptibilities using the multi-atlas label-fusion method to detect early cognitive impairments (Shibata et al., 2022).

Figure 3. The left-hand panel shows the pipeline for the multi-atlas approaches for each individual QSM/T1WI image through the MRICloud platform (https://mricloud.org/) (A). The right-hand panel shows the pipeline for developing the machine learning-based models (B). MNI, Montreal Neurologic Institute; PD-MCI, Parkinson’s disease with mild cognitive impairment; PD-CN, Parkinson’s disease with normal cognition; QSM, quantitative susceptibility mapping; T1WI, T1-weighted image (adapted with permission from Shibata et al., 2022).

More advanced QSM techniques should be highlighted: R2* relaxometry analysis combined with QSM can distinguish microstructural changes of white matter demyelination from iron deposition, thereby providing a sensitive and biologically specific measure for white matter lesions (Kan et al., 2022). Recent breakthroughs in small vessel imaging within the central nervous system, such as venous oxygen saturation and blood–brain barrier function using QSM techniques, are promising biomarkers in research and clinical settings for AD (Uchida et al., 2020a,b).

Limitations

One of the major limitations of the magnetic susceptibility measured by QSM is its non-specific nature. In AD brain research, the contrast to the surrounding brain tissues is considered to be caused mainly by iron deposition; however, it can be caused by other substances, such as calcium, lipids, and myelin (Li et al., 2011; Deistung et al., 2013). Current QSM approaches are unable to identify the chemical configurations underlying abnormal magnetostatic behaviors. Another is that multiple iron containing species may interact differently with Aβ and tau proteins (Sayre et al., 2000; Everett et al., 2014). It remains unclear whether QSM is equally sensitive to iron in different states, as each species of iron may have a different intrinsic magnetic susceptibility. These complexities of the QSM technique could result in experimental variability in the associations of magnetic susceptibilities with PET signals and explain some of the seemingly contradictory findings in different populations. Precise relationships between QSM and established AD biomarkers should be elucidated in the near future by applying ultra-high field acquisition protocols (Alkemade et al., 2020; Tuzzi et al., 2020) and machine learning algorithms (Kim et al., 2020).

Conclusion

The QSM technique provides a sensitive and biologically specific contrast of magnetic susceptibilities. Hence, it can be used for in vivo characterization in accordance with tissue magnetic susceptibilities, ranging from common applications, such as cerebral iron deposition, to more recent applications, such as assessment of impaired myelination, quantification of venous oxygen saturation, and measurement of blood–brain barrier function. Therefore, the acquisition sequence for post-processing susceptibility maps should be included in routine applications due to its high-throughput computing nature with important implications. We conclude that QSM has the ability to provide pathophysiological information on brain tissue properties and the potential to measure the efficacy of novel therapeutics in clinical settings for AD.

Author contributions

YU: conceptualization, investigation, data curation, writing – original draft, and funding acquisition. HK: conceptualization, data curation, and writing – review and editing. KS: data curation and writing – review and editing. KO: supervision and writing – review and editing. NM: conceptualization, supervision, and writing – review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Reiwa 3 Grants-in-aid for Young Scientists of the Kowa Life Science Foundation, Grants-in-aid of 2021th Japan Brain Foundation, and KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research C (22K07520).

Conflict of interest

KO was a consultant for “AnatomyWorks” and “Corporate-M.” This arrangement was being managed by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer CB declared a past co-authorship with the authors, YU and NM to the handling editor.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acosta-Cabronero, J., Cardenas-Blanco, A., Betts, M. J., Butryn, M., Valdes-Herrera, J. P., Galazky, I., et al. (2017). The whole-brain pattern of magnetic susceptibility perturbations in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 140, 118–131. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww278

Acosta-Cabronero, J., Machts, J., Schreiber, S., Abdulla, S., Kollewe, K., Petri, S., et al. (2018a). Quantitative susceptibility MRI to detect brain iron in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Radiology 289, 195–203. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018180112

Acosta-Cabronero, J., Milovic, C., Mattern, H., Tejos, C., Speck, O., and Callaghan, M. F. (2018b). A robust multi-scale approach to quantitative susceptibility mapping. Neuroimage 183, 7–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.07.065

Acosta-Cabronero, J., Williams, G. B., Cardenas-Blanco, A., Arnold, R. J., Lupson, V., and Nestor, P. J. (2013). In vivo quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 8:e81093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081093

Aillaud, I., and Funke, S. A. (2022). Tau aggregation inhibiting peptides as potential therapeutics for Alzheimer disease. Cell Mol Neurobiol. doi: 10.1007/s10571-022-01230-7 [Epub ahead of print].

Akter, M., Hirai, T., Hiai, Y., Kitajima, M., Komi, M., Murakami, R., et al. (2007). Detection of hemorrhagic hypointense foci in the brain on susceptibility-weighted imaging clinical and phantom studies. Acad. Radiol. 14, 1011–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2007.05.013

Alkemade, A., Mulder, M. J., Groot, J. M., Isaacs, B. R., van Berendonk, N., Lute, N., et al. (2020). The Amsterdam ultra-high field adult lifespan database (AHEAD): a freely available multimodal 7 Tesla submillimeter magnetic resonance imaging database. Neuroimage 221:117200. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117200

Argyridis, I., Li, W., Johnson, G. A., and Liu, C. (2014). Quantitative magnetic susceptibility of the developing mouse brain reveals microstructural changes in the white matter. Neuroimage 88, 134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.11.026

Ashburner, J., and Friston, K. J. (2000). Voxel-based morphometry–the methods. Neuroimage 11(6 Pt 1) 805–821. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0582

Ayton, S., Fazlollahi, A., Bourgeat, P., Raniga, P., Ng, A., Lim, Y. Y., et al. (2017). Cerebral quantitative susceptibility mapping predicts amyloid-beta-related cognitive decline. Brain 140, 2112–2119. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx137

Ayton, S., Lei, P., and Bush, A. I. (2015). Biometals and their therapeutic implications in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics 12, 109–120. doi: 10.1007/s13311-014-0312-z

Bagher-Ebadian, H., Jiang, Q., and Ewing, J. R. (2008). A modified Fourier-based phase unwrapping algorithm with an application to MRI venography. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 27, 649–652. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21230

Baik, S. K., Choi, W., Oh, S. J., Park, K. P., Park, M. G., Yang, T. I., et al. (2012). Change in cortical vessel signs on susceptibility-weighted images after full recanalization in hyperacute ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 34, 206–212. doi: 10.1159/000342148

Baker, S. L., Harrison, T. M., Maass, A., La Joie, R., and Jagust, W. J. (2019). Effect of off-target binding on (18)F-flortaucipir variability in healthy controls across the life span. J. Nucl. Med. 60, 1444–1451. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.224113

Barnes, S. R., Haacke, E. M., Ayaz, M., Boikov, A. S., Kirsch, W., and Kido, D. (2011). Semiautomated detection of cerebral microbleeds in magnetic resonance images. Magn. Reson. Imaging 29, 844–852. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2011.02.028

Bilgic, B., Pfefferbaum, A., Rohlfing, T., Sullivan, E. V., and Adalsteinsson, E. (2012). MRI estimates of brain iron concentration in normal aging using quantitative susceptibility mapping. Neuroimage 59, 2625–2635. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.077

Borlongan, C. V. (2012). Recent preclinical evidence advancing cell therapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 237, 142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.06.024

Brier, M. R., Gordon, B., Friedrichsen, K., McCarthy, J., Stern, A., Christensen, J., et al. (2016). Tau and Aβ imaging, CSF measures, and cognition in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 8:338ra66. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf2362

Cao, W., Li, W., Han, H., O’Leary-Moore, S. K., Sulik, K. K., Allan Johnson, G., et al. (2014). Prenatal alcohol exposure reduces magnetic susceptibility contrast and anisotropy in the white matter of mouse brains. NeuroImage 102, 748–755. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.08.035

Chalian, M., Tekes, A., Meoded, A., Poretti, A., and Huisman, T. A. (2011). Susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI): a potential non-invasive imaging tool for characterizing ischemic brain injury? J. Neuroradiol. 38, 187–190. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2010.12.006

Chen, L., Soldan, A., Oishi, K., Faria, A., Zhu, Y., Albert, M., et al. (2020). Quantitative susceptibility mapping of brain iron and beta-amyloid in MRI and PET relating to cognitive performance in cognitively normal older adults. Radiology 298, 353–362. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201603

Cheng, A. L., Batool, S., McCreary, C. R., Lauzon, M. L., Frayne, R., Goyal, M., et al. (2013). Susceptibility-weighted imaging is more reliable than T2*-weighted gradient-recalled echo MRI for detecting microbleeds. Stroke 44, 2782–2786. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.113.002267

Choi, J. H., and Mohr, J. P. (2005). Brain arteriovenous malformations in adults. Lancet Neurol. 4, 299–308. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(05)70073-9

Choi, J. Y., Cho, H., Ahn, S. J., Lee, J. H., Ryu, Y. H., Lee, M. S., et al. (2018). Off-Target (18)F-AV-1451 binding in the basal ganglia correlates with age-related iron accumulation. J Nucl Med 59, 117–120. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.195248

Cogswell, P. M., Wiste, H. J., Senjem, M. L., Gunter, J. L., Weigand, S. D., Schwarz, C. G., et al. (2021). Associations of quantitative susceptibility mapping with Alzheimer’s disease clinical and imaging markers. Neuroimage 224:117433. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117433

Conrad, M., Angeli, J. P., Vandenabeele, P., and Stockwell, B. R. (2016). Regulated necrosis: disease relevance and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15, 348–366. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2015.6

Crapper McLachlan, D. R., Dalton, A. J., Kruck, T. P., Bell, M. Y., Smith, W. L., Kalow, W., et al. (1991). Intramuscular desferrioxamine in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 337, 1304–1308. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92978-b

Cummings, J. L., Tong, G., and Ballard, C. (2019). Treatment combinations for Alzheimer’s disease: current and future pharmacotherapy options. J. Alzheimers Dis. 67, 779–794. doi: 10.3233/jad-180766

Daugherty, A. M., and Raz, N. (2016). Accumulation of iron in the putamen predicts its shrinkage in healthy older adults: a multi-occasion longitudinal study. Neuroimage 128, 11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.12.045

de Rochefort, L., Liu, T., Kressler, B., Liu, J., Spincemaille, P., Lebon, V., et al. (2010). Quantitative susceptibility map reconstruction from MR phase data using bayesian regularization: validation and application to brain imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 63, 194–206. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22187

Deistung, A., Schäfer, A., Schweser, F., Biedermann, U., Turner, R., and Reichenbach, J. R. (2013). Toward in vivo histology: a comparison of quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) with magnitude-, phase-, and R2*-imaging at ultra-high magnetic field strength. Neuroimage 65, 299–314. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.09.055

Deoni, S. C., Dean, D. C. III, O’Muircheartaigh, J., Dirks, H., and Jerskey, B. A. (2012). Investigating white matter development in infancy and early childhood using myelin water faction and relaxation time mapping. Neuroimage 63, 1038–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.037

Dixon, S. J., Lemberg, K. M., Lamprecht, M. R., Skouta, R., Zaitsev, E. M., Gleason, C. E., et al. (2012). Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149, 1060–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042

Domínguez, J. F., Ng, A. C., Poudel, G., Stout, J. C., Churchyard, A., Chua, P., et al. (2016). Iron accumulation in the basal ganglia in Huntington’s disease: cross-sectional data from the IMAGE-HD study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 87, 545–549. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-310183

Eskreis-Winkler, S., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J., Liu, Z., Dimov, A., Gupta, A., et al. (2017). The clinical utility of QSM: disease diagnosis, medical management, and surgical planning. NMR Biomed. 30. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3668

Essig, M., Reichenbach, J. R., Schad, L. R., Schoenberg, S. O., Debus, J., and Kaiser, W. A. (1999). High-resolution MR venography of cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Magn. Reson. Imaging 17, 1417–1425. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(99)00084-3

Everett, J., Céspedes, E., Shelford, L. R., Exley, C., Collingwood, J. F., Dobson, J., et al. (2014). Evidence of redox-active iron formation following aggregation of ferrihydrite and the Alzheimer’s disease peptide β-amyloid. Inorg. Chem. 53, 2803–2809. doi: 10.1021/ic402406g

Fan, A. P., Evans, K. C., Stout, J. N., Rosen, B. R., and Adalsteinsson, E. (2015). Regional quantification of cerebral venous oxygenation from MRI susceptibility during hypercapnia. Neuroimage 104, 146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.09.068

Fujioka, M., Okuchi, K., Iwamura, A., Taoka, T., and Siesjö, B. K. (2013). A mismatch between the abnormalities in diffusion- and susceptibility-weighted magnetic resonance imaging may represent an acute ischemic penumbra with misery perfusion. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 22, 1428–1431. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.12.009

Gauthier, C. J., and Hoge, R. D. (2012). Magnetic resonance imaging of resting OEF and CMRO2 using a generalized calibration model for hypercapnia and hyperoxia. Neuroimage 60, 1212–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.056

Gong, N. J., Dibb, R., Bulk, M., van der Weerd, L., and Liu, C. (2019). Imaging beta amyloid aggregation and iron accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease using quantitative susceptibility mapping MRI. Neuroimage 191, 176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.02.019

Good, P. F., Perl, D. P., Bierer, L. M., and Schmeidler, J. (1992). Selective accumulation of aluminum and iron in the neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease: a laser microprobe (LAMMA) study. Ann. Neurol. 31, 286–292. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310310

Goos, J. D., van der Flier, W. M., Knol, D. L., Pouwels, P. J., Scheltens, P., Barkhof, F., et al. (2011). Clinical relevance of improved microbleed detection by susceptibility-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Stroke 42, 1894–1900. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.110.599837

Greenberg, S. M., Vernooij, M. W., Cordonnier, C., Viswanathan, A., Al-Shahi Salman, R., Warach, S., et al. (2009). Cerebral microbleeds: a guide to detection and interpretation. Lancet Neurol. 8, 165–174. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(09)70013-4

Guo, C., Wang, P., Zhong, M. L., Wang, T., Huang, X. S., Li, J. Y., et al. (2013). Deferoxamine inhibits iron induced hippocampal tau phosphorylation in the Alzheimer transgenic mouse brain. Neurochem. Int. 62, 165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.12.005

Guo, L. F., Wang, G., Zhu, X. Y., Liu, C., and Cui, L. (2013). Comparison of ESWAN. SWI-SPGR, and 2D T2*-weighted GRE sequence for depicting cerebral microbleeds. Clin. Neuroradiol. 23, 121–127. doi: 10.1007/s00062-012-0185-7

Haacke, E. M., Lai, S., Yablonskiy, D. A., and Lin, W. (1995). In vivo validation of the bold mechanism: a review of signal changes in gradient echo functional MRI in the presence of flow. Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 6, 153–163. doi: 10.1002/ima.1850060204

Haacke, E. M., Liu, S., Buch, S., Zheng, W., Wu, D., and Ye, Y. (2015). Quantitative susceptibility mapping: current status and future directions. Magn. Reson. Imaging 33, 1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2014.09.004

Haacke, E. M., Miao, Y., Liu, M., Habib, C. A., Katkuri, Y., Liu, T., et al. (2010). Correlation of putative iron content as represented by changes in R2* and phase with age in deep gray matter of healthy adults. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 32, 561–576. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22293

Haacke, E. M., Xu, Y., Cheng, Y. C., and Reichenbach, J. R. (2004). Susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI). Magn. Reson. Med. 52, 612–618. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20198

Harada, R., Ishiki, A., Kai, H., Sato, N., Furukawa, K., Furumoto, S., et al. (2018). Correlations of (18)F-stocktickerTHK5351 PET with postmortem burden of tau and astrogliosis in Alzheimer disease. J. Nucl. Med. 59, 671–674. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.197426

Hermier, M., and Nighoghossian, N. (2004). Contribution of susceptibility-weighted imaging to acute stroke assessment. Stroke 35, 1989–1994. doi: 10.1161/01.Str.0000133341.74387.96

House, M. J., St Pierre, T. G., Kowdley, K. V., Montine, T., Connor, J., Beard, J., et al. (2007). Correlation of proton transverse relaxation rates (R2) with iron concentrations in postmortem brain tissue from alzheimer’s disease patients. Magn. Reson. Med. 57, 172–180. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21118

Hwang, E. J., Kim, H. G., Kim, D., Rhee, H. Y., Ryu, C. W., Liu, T., et al. (2016). Texture analyses of quantitative susceptibility maps to differentiate Alzheimer’s disease from cognitive normal and mild cognitive impairment. Med. Phys. 43:4718. doi: 10.1118/1.4958959

Jack, C. R. Jr., Bennett, D. A., Blennow, K., Carrillo, M. C., Dunn, B., Haeberlein, S. B., et al. (2018). NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 535–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018

Jack, C. R. Jr., Garwood, M., Wengenack, T. M., Borowski, B., Curran, G. L., Lin, J., et al. (2004). In vivo visualization of Alzheimer’s amyloid plaques by magnetic resonance imaging in transgenic mice without a contrast agent. Magn. Reson. Med. 52, 1263–1271. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20266

Jagadeesan, B. D., Delgado Almandoz, J. E., Moran, C. J., and Benzinger, T. L. (2011). Accuracy of susceptibility-weighted imaging for the detection of arteriovenous shunting in vascular malformations of the brain. Stroke 42, 87–92. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.110.5848621

Jansen, W. J., Ossenkoppele, R., Knol, D. L., Tijms, B. M., Scheltens, P., Verhey, F. R., et al. (2015). Prevalence of cerebral amyloid pathology in persons without dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA 313, 1924–1938. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4668

Jiang, D., Lin, Z., Liu, P., Sur, S., Xu, C., Hazel, K., et al. (2020). Brain oxygen extraction is differentially altered by Alzheimer’s and vascular diseases. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 52, 1829–1837. doi: 10.1002/jmri.27264

Kagerer, S. M., van Bergen, J. M. G., Li, X., Quevenco, F. C., Gietl, A. F., Studer, S., et al. (2020). APOE4 moderates effects of cortical iron on synchronized default mode network activity in cognitively healthy old-aged adults. Alzheimers Dement. 12:e12002. doi: 10.1002/dad2.12002

Kan, H., Arai, N., Kasai, H., Kunitomo, H., Hirose, Y., and Shibamoto, Y. (2017). Quantitative susceptibility mapping using principles of echo shifting with a train of observations sequence on 1.5T MRI. Magn. Reson. Imaging 42, 37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2017.05.002

Kan, H., Arai, N., Takizawa, M., Kasai, H., Kunitomo, H., Hirose, Y., et al. (2019). Improvement of signal inhomogeneity induced by radio-frequency transmit-related phase error for single-step quantitative susceptibility mapping reconstruction. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 18, 276–285. doi: 10.2463/mrms.tn.2018-0066

Kan, H., Arai, N., Takizawa, M., Omori, K., Kasai, H., Kunitomo, H., et al. (2018). Background field removal technique based on non-regularized variable kernels sophisticated harmonic artifact reduction for phase data for quantitative susceptibility mapping. Magn. Reson. Imaging 52, 94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2018.06.006

Kan, H., Kasai, H., Arai, N., Kunitomo, H., Hirose, Y., and Shibamoto, Y. (2016). Background field removal technique using regularization enabled sophisticated harmonic artifact reduction for phase data with varying kernel sizes. Magn. Reson. Imaging 34, 1026–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2016.04.019

Kan, H., Uchida, Y., Arai, N., Ueki, Y., Aoki, T., Kasai, H., et al. (2020). Simultaneous voxel-based magnetic susceptibility and morphometry analysis using magnetization-prepared spoiled turbo multiple gradient echo. NMR Biomed. 33:e4272. doi: 10.1002/nbm.4272

Kan, H., Uchida, Y., Ueki, Y., Arai, N., Tsubokura, S., Kunitomo, H., et al. (2022). R2* relaxometry analysis for mapping of white matter alteration in parkinson’s disease with mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage Clin. 33:102938. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2022.102938

Kao, H. W., Tsai, F. Y., and Hasso, A. N. (2012). Predicting stroke evolution: comparison of susceptibility-weighted MR imaging with MR perfusion. Eur. Radiol. 22, 1397–1403. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2387-4

Karsa, A., and Shmueli, K. S. E. G. U. E. (2019). A speedy region-growing algorithm for unwrapping estimated phase. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 38, 1347–1357. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2018.2884093

Karsa, A., Punwani, S., and Shmueli, K. (2019). The effect of low resolution and coverage on the accuracy of susceptibility mapping. Magn. Reson. Med. 81, 1833–1848. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27542

Kesavadas, C., Thomas, B., Pendharakar, H., and Sylaja, P. N. (2011). Susceptibility weighted imaging: does it give information similar to perfusion weighted imaging in acute stroke? J. Neurol. 258, 932–934. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5843-6

Keuken, M. C., Bazin, P. L., Backhouse, K., Beekhuizen, S., Himmer, L., Kandola, A., et al. (2017). Effects of aging on T1. T2*, and QSM MRI values in the subcortex. Brain Struct. Funct. 222, 2487–2505. doi: 10.1007/s00429-016-1352-4

Kim, H. G., Park, S., Rhee, H. Y., Lee, K. M., Ryu, C. W., Lee, S. Y., et al. (2020). Evaluation and prediction of early Alzheimer’s disease using a machine learning-based optimized combination-feature set on gray matter volume and quantitative susceptibility mapping. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 17, 428–437. doi: 10.2174/1567205017666200624204427

Kim, H. G., Park, S., Rhee, H. Y., Lee, K. M., Ryu, C. W., Rhee, S. J., et al. (2017). Quantitative susceptibility mapping to evaluate the early stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage Clin. 16, 429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.08.019

Klohs, J., Politano, I. W., Deistung, A., Grandjean, J., Drewek, A., Dominietto, M., et al. (2013). Longitudinal assessment of amyloid pathology in transgenic ArcAβ mice using multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging. PLoS One 8:e66097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066097

Kudo, K., Liu, T., Murakami, T., Goodwin, J., Uwano, I., Yamashita, F., et al. (2016). Oxygen extraction fraction measurement using quantitative susceptibility mapping: comparison with positron emission tomography. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 36, 1424–1433. doi: 10.1177/0271678x15606713

Kwan, J. Y., Jeong, S. Y., Van Gelderen, P., Deng, H. X., Quezado, M. M., Danielian, L. E., et al. (2012). Iron accumulation in deep cortical layers accounts for MRI signal abnormalities in ALS: correlating 7 tesla MRI and pathology. PLoS One 7:e35241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035241

Langkammer, C., Krebs, N., Goessler, W., Scheurer, E., Ebner, F., Yen, K., et al. (2010). Quantitative MR imaging of brain iron: a postmortem validation study. Radiology 257, 455–462. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100495

Langkammer, C., Schweser, F., Krebs, N., Deistung, A., Goessler, W., Scheurer, E., et al. (2012b). Quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) as a means to measure brain iron? A post mortem validation study. Neuroimage 62, 1593–1599. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.05.049

Langkammer, C., Krebs, N., Goessler, W., Scheurer, E., Yen, K., Fazekas, F., et al. (2012a). Susceptibility induced gray-white matter MRI contrast in the human brain. Neuroimage 59, 1413–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.045

Langkammer, C., Liu, T., Khalil, M., Enzinger, C., Jehna, M., Fuchs, S., et al. (2013). Quantitative susceptibility mapping in multiple sclerosis. Radiology 267, 551–559. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120707

Langkammer, C., Pirpamer, L., Seiler, S., Deistung, A., Schweser, F., Franthal, S., et al. (2016). Quantitative susceptibility mapping in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One 11:e0162460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162460

Lebel, C., Gee, M., Camicioli, R., Wieler, M., Martin, W., and Beaulieu, C. (2012). Diffusion tensor imaging of white matter tract evolution over the lifespan. Neuroimage 60, 340–352. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.094

Lee, J., Shmueli, K., Kang, B. T., Yao, B., Fukunaga, M., van Gelderen, P., et al. (2012). The contribution of myelin to magnetic susceptibility-weighted contrasts in high-field MRI of the brain. Neuroimage 59, 3967–3975. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.076

Lee, S. M., Choi, Y. H., You, S. K., Lee, W. K., Kim, W. H., Kim, H. J., et al. (2018). Age-related changes in tissue value properties in children: simultaneous quantification of relaxation times and proton density using synthetic magnetic resonance imaging. Invest. Radiol. 53, 236–245. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000435

Lemoine, L., Leuzy, A., Chiotis, K., Rodriguez-Vieitez, E., and Nordberg, A. (2018). Tau positron emission tomography imaging in tauopathies: the added hurdle of off-target binding. Alzheimers Dement. 10, 232–236. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2018.01.007

LeVine, S. M., Wulser, M. J., and Lynch, S. G. (1998). Iron quantification in cerebrospinal fluid. Anal. Biochem. 265, 74–78. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2903

Li, W., Wang, N., Yu, F., Han, H., Cao, W., Romero, R., et al. (2015). A method for estimating and removing streaking artifacts in quantitative susceptibility mapping. Neuroimage 108, 111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.12.043

Li, W., Wu, B., and Liu, C. (2011). Quantitative susceptibility mapping of human brain reflects spatial variation in tissue composition. Neuroimage 55, 1645–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.088

Li, W., Wu, B., Batrachenko, A., Bancroft-Wu, V., Morey, R. A., Shashi, V., et al. (2014). Differential developmental trajectories of magnetic susceptibility in human brain gray and white matter over the lifespan. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35, 2698–2713. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22360

Li, X., Chen, L., Kutten, K., Ceritoglu, C., Li, Y., Kang, N., et al. (2019). Multi-atlas tool for automated segmentation of brain gray matter nuclei and quantification of their magnetic susceptibility. Neuroimage 191, 337–349. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.02.016

Lim, I. A., Faria, A. V., Li, X., Hsu, J. T., Airan, R. D., Mori, S., et al. (2013). Human brain atlas for automated region of interest selection in quantitative susceptibility mapping: application to determine iron content in deep gray matter structures. Neuroimage 82, 449–469. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.127

Linn, J. (2015). Imaging of cerebral microbleeds. Clin. Neuroradiol. 25(Suppl. 2) 167–175. doi: 10.1007/s00062-015-0458-z

Liu, C., Li, W., Johnson, G. A., and Wu, B. (2011). High-field (9.4 T) MRI of brain dysmyelination by quantitative mapping of magnetic susceptibility. Neuroimage 56, 930–938. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.024

Liu, C., Li, W., Tong, K. A., Yeom, K. W., and Kuzminski, S. (2015). Susceptibility-weighted imaging and quantitative susceptibility mapping in the brain. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 42, 23–41. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24768

Liu, J. L., Fan, Y. G., Yang, Z. S., Wang, Z. Y., and Guo, C. (2018). Iron and Alzheimer’s disease: from pathogenesis to therapeutic implications. Front. Neurosci. 12:632. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00632

Liu, S., Buch, S., Chen, Y., Choi, H. S., Dai, Y., Habib, C., et al. (2017). Susceptibility-weighted imaging: current status and future directions. NMR Biomed. 30. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3552

Liu, T., Khalidov, I., de Rochefort, L., Spincemaille, P., Liu, J., Tsiouris, A. J., et al. (2011). A novel background field removal method for MRI using projection onto dipole fields (PDF). NMR Biomed. 24, 1129–1136. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1670

Liu, T., Spincemaille, P., de Rochefort, L., Kressler, B., and Wang, Y. (2009). Calculation of susceptibility through multiple orientation sampling (COSMOS): a method for conditioning the inverse problem from measured magnetic field map to susceptibility source image in MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 61, 196–204. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21828

Liu, Z., Spincemaille, P., Yao, Y., Zhang, Y., and Wang, Y. (2018). MEDI+0: morphology enabled dipole inversion with automatic uniform cerebrospinal fluid zero reference for quantitative susceptibility mapping. Magn. Reson. Med. 79, 2795–2803. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26946

Lou, M., Chen, Z., Wan, J., Hu, H., Cai, X., Shi, Z., et al. (2014). Susceptibility-diffusion mismatch predicts thrombolytic outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 35, 2061–2067. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4017

Lovell, M. A., Robertson, J. D., Teesdale, W. J., Campbell, J. L., and Markesbery, W. R. (1998). Copper, iron and zinc in Alzheimer’s disease senile plaques. J. Neurol. Sci. 158, 47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00092-6

Luo, S., Yang, L., and Wang, L. (2015). Comparison of susceptibility-weighted and perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in the detection of penumbra in acute ischemic stroke. J. Neuroradiol. 42, 255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2014.07.002

Maphis, N., Xu, G., Kokiko-Cochran, O. N., Jiang, S., Cardona, A., Ransohoff, R. M., et al. (2015). Reactive microglia drive tau pathology and contribute to the spreading of pathological tau in the brain. Brain 138(Pt 6) 1738–1755. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv081

Masaldan, S., Bush, A. I., Devos, D., Rolland, A. S., and Moreau, C. (2019). Striking while the iron is hot: iron metabolism and ferroptosis in neurodegeneration. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 133, 221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.09.033

Matsuda, H. (2016). MRI morphometry in Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 30, 17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.01.003

Meineke, J., Wenzel, F., De Marco, M., Venneri, A., Blackburn, D. J., Teh, K., et al. (2018). Motion artifacts in standard clinical setting obscure disease-specific differences in quantitative susceptibility mapping. Phys. Med. Biol. 63:14NT01. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aacc52

Meoded, A., Poretti, A., Benson, J. E., Tekes, A., and Huisman, T. A. (2014). Evaluation of the ischemic penumbra focusing on the venous drainage: the role of susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) in pediatric ischemic cerebral stroke. J. Neuroradiol. 41, 108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2013.04.002

Mikati, A. G., Tan, H., Shenkar, R., Li, L., Zhang, L., Guo, X., et al. (2014). Dynamic permeability and quantitative susceptibility: related imaging biomarkers in cerebral cavernous malformations. Stroke 45, 598–601. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.113.003548

Moon, Y., Han, S. H., and Moon, W. J. (2016). Patterns of brain iron accumulation in vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s dementia using quantitative susceptibility mapping imaging. J. Alzheimers Dis. 51, 737–745. doi: 10.3233/JAD-151037

Neelavalli, J., Mody, S., Yeo, L., Jella, P. K., Korzeniewski, S. J., Saleem, S., et al. (2014). MR venography of the fetal brain using susceptibility weighted imaging. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 40, 949–957. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24476

Ning, N., Liu, C., Wu, P., Hu, Y., Zhang, W., Zhang, L., et al. (2019). Spatiotemporal variations of magnetic susceptibility in the deep gray matter nuclei from 1 month to 6 years: a quantitative susceptibility mapping study. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 49, 1600–1609. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26579

O’Callaghan, J., Holmes, H., Powell, N., Wells, J. A., Ismail, O., Harrison, I. F., et al. (2017). Tissue magnetic susceptibility mapping as a marker of tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage 159, 334–345. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.08.003

Özbay, P. S., Deistung, A., Feng, X., Nanz, D., Reichenbach, J. R., and Schweser, F. (2017). A comprehensive numerical analysis of background phase correction with V-SHARP. NMR Biomed. 30. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3550

Polak, D., Chatnuntawech, I., Yoon, J., Iyer, S. S., Milovic, C., Lee, J., et al. (2020). Nonlinear dipole inversion (NDI) enables robust quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM). NMR Biomed. 33:e4271. doi: 10.1002/nbm.4271

Pourhamzeh, M., Joghataei, M. T., Mehrabi, S., Ahadi, R., Hojjati, S. M. M., Fazli, N., et al. (2021). The interplay of tau protein and β-amyloid: while tauopathy spreads more profoundly than amyloidopathy, both processes are almost equally pathogenic. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 41, 1339–1354. doi: 10.1007/s10571-020-00906-2

Praticò, D., and Sung, S. (2004). Lipid peroxidation and oxidative imbalance: early functional events in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 6, 171–175. doi: 10.3233/jad-2004-6209

Rao, I. Y., Hanson, L. R., Johnson, J. C., Rosenbloom, M. H., and Frey, W. H. II (2022). Brain glucose hypometabolism and iron accumulation in different brain regions in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Pharmaceuticals 15:551. doi: 10.3390/ph15050551

Ravanfar, P., Loi, S. M., Syeda, W. T., Van Rheenen, T. E., Bush, A. I., Desmond, P., et al. (2021). Systematic review: quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) of brain iron profile in neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Neurosci. 15:618435. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.618435

Reed, T. T., Pierce, W. M., Markesbery, W. R., and Butterfield, D. A. (2009). Proteomic identification of HNE-bound proteins in early Alzheimer disease: insights into the role of lipid peroxidation in the progression of AD. Brain Res. 1274, 66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.04.009

Reichenbach, J. R., and Haacke, E. M. (2001). High-resolution BOLD venographic imaging: a window into brain function. NMR Biomed. 14, 453–467. doi: 10.1002/nbm.722

Reichenbach, J. R., Essig, M., Haacke, E. M., Lee, B. C., Przetak, C., Kaiser, W. A., et al. (1998). High-resolution venography of the brain using magnetic resonance imaging. Magma 6, 62–69. doi: 10.1007/bf02662513

Reichenbach, J. R., Jonetz-Mentzel, L., Fitzek, C., Haacke, E. M., Kido, D. K., Lee, B. C., et al. (2001). High-resolution blood oxygen-level dependent MR venography (HRBV): a new technique. Neuroradiology 43, 364–369. doi: 10.1007/s002340000503

Reichenbach, J. R., Venkatesan, R., Schillinger, D. J., Kido, D. K., and Haacke, E. M. (1997). Small vessels in the human brain: MR venography with deoxyhemoglobin as an intrinsic contrast agent. Radiology 204, 272–277. doi: 10.1148/radiology.204.1.9205259

Robinson, S. D., Bredies, K., Khabipova, D., Dymerska, B., Marques, J. P., and Schweser, F. (2017). An illustrated comparison of processing methods for MR phase imaging and QSM: combining array coil signals and phase unwrapping. NMR Biomed. 30:e3601. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3601

Santhosh, K., Kesavadas, C., Thomas, B., Gupta, A. K., Thamburaj, K., and Kapilamoorthy, T. R. (2009). Susceptibility weighted imaging: a new tool in magnetic resonance imaging of stroke. Clin. Radiol. 64, 74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2008.04.022

Sayre, L. M., Perry, G., Harris, P. L., Liu, Y., Schubert, K. A., and Smith, M. A. (2000). In situ oxidative catalysis by neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques in Alzheimer’s disease: a central role for bound transition metals. J. Neurochem. 74, 270–279. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740270.x

Scheltens, P., Blennow, K., Breteler, M. M. B., de Strooper, B., Frisoni, G. B., Salloway, S., et al. (2016). Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 388, 505–517. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01124-1

Schenck, J. F. (1996). The role of magnetic susceptibility in magnetic resonance imaging: MRI magnetic compatibility of the first and second kinds. Med. Phys. 23, 815–850. doi: 10.1118/1.597854

Serrano-Pozo, A., Frosch, M. P., Masliah, E., and Hyman, B. T. (2011). Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 1:a006189. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006189

Shams, S., Martola, J., Cavallin, L., Granberg, T., Shams, M., Aspelin, P., et al. (2015). SWI or T2*: which MRI sequence to use in the detection of cerebral microbleeds? The karolinska imaging dementia study. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 36, 1089–1095. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4248

Shibata, H., Uchida, Y., Inui, S., Kan, H., Sakurai, K., Oishi, N., et al. (2022). Machine learning trained with quantitative susceptibility mapping to detect mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 94, 104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2021.12.004

Shmueli, K., de Zwart, J. A., van Gelderen, P., Li, T. Q., Dodd, S. J., and Duyn, J. H. (2009). Magnetic susceptibility mapping of brain tissue in vivo using MRI phase data. Magn. Reson. Med. 62, 1510–1522. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22135

Sjöbeck, M., Haglund, M., and Englund, E. (2005). Decreasing myelin density reflected increasing white matter pathology in Alzheimer’s disease–a neuropathological study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 20, 919–926. doi: 10.1002/gps.1384

Smith, M. A., Harris, P. L., Sayre, L. M., and Perry, G. (1997). Iron accumulation in Alzheimer disease is a source of redox-generated free radicals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 9866–9868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9866

Spotorno, N., Acosta-Cabronero, J., Stomrud, E., Lampinen, B., Strandberg, O. T., van Westen, D., et al. (2020). Relationship between cortical iron and tau aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 143, 1341–1349. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa089

Sun, H., and Wilman, A. H. (2014). Background field removal using spherical mean value filtering and Tikhonov regularization. Magn. Reson. Med. 71, 1151–1157. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24765

Tao, Y., Wang, Y., Rogers, J. T., and Wang, F. (2014). Perturbed iron distribution in Alzheimer’s disease serum, cerebrospinal fluid, and selected brain regions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 42, 679–690. doi: 10.3233/jad-140396

Tariq, S., d’Esterre, C. D., Sajobi, T. T., Smith, E. E., Longman, R. S., Frayne, R., et al. (2018). A longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study of neurodegenerative and small vessel disease, and clinical cognitive trajectories in non demented patients with transient ischemic attack: the PREVENT study. BMC Geriatr. 18:163. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0858-4

Tiepolt, S., Schafer, A., Rullmann, M., Roggenhofer, E., Netherlands Brain, B., Gertz, H. J., et al. (2018). Quantitative susceptibility mapping of amyloid-beta aggregates in Alzheimer’s disease with 7T MR. J. Alzheimers Dis. 64, 393–404. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180118

Tong, K. A., Ashwal, S., Obenaus, A., Nickerson, J. P., Kido, D., and Haacke, E. M. (2008). Susceptibility-weighted MR imaging: a review of clinical applications in children. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 29, 9–17. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0786

Tsui, Y. K., Tsai, F. Y., Hasso, A. N., Greensite, F., and Nguyen, B. V. (2009). Susceptibility-weighted imaging for differential diagnosis of cerebral vascular pathology: a pictorial review. J. Neurol. Sci. 287, 7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.08.064

Tuzzi, E., Balla, D. Z., Loureiro, J. R. A., Neumann, M., Laske, C., Pohmann, R., et al. (2020). Ultra-high field MRI in Alzheimer’s disease: effective transverse relaxation rate and quantitative susceptibility mapping of human brain in vivo and ex vivo compared to histology. J. Alzheimers Dis. 73, 1481–1499. doi: 10.3233/jad-190424

Uchida, Y., Kan, H., Inoue, H., Oomura, M., Shibata, H., Kano, Y., et al. (2022a). Penumbra detection with oxygen extraction fraction using magnetic susceptibility in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Front. Neurol. 13:752450. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.752450

Uchida, Y., Kan, H., Sakurai, K., Horimoto, Y., Hayashi, E., Iida, A., et al. (2022b). APOE ε4 dose associates with increased brain iron and β-amyloid via blood-brain barrier dysfunction. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2021-328519 [Epub ahead of print].

Uchida, Y., Kan, H., Sakurai, K., Arai, N., Inui, S., Kobayashi, S., et al. (2020a). Iron leakage owing to blood-brain barrier disruption in small vessel disease CADASIL. Neurology 95, e1188–e1198. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010148

Uchida, Y., Kan, H., Sakurai, K., Inui, S., Kobayashi, S., Akagawa, Y., et al. (2020b). Magnetic susceptibility associates with dopaminergic deficits and cognition in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 35, 1396–1405. doi: 10.1002/mds.28077

Uchida, Y., Kan, H., Sakurai, K., Arai, N., Kato, D., Kawashima, S., et al. (2019). Voxel-based quantitative susceptibility mapping in Parkinson’s disease with mild cognitive impairment. Mov. Disord. 34, 1164–1173. doi: 10.1002/mds.27717

van Bergen, J. M. G., Li, X., Quevenco, F. C., Gietl, A. F., Treyer, V., Meyer, R., et al. (2018). Simultaneous quantitative susceptibility mapping and Flutemetamol-PET suggests local correlation of iron and beta-amyloid as an indicator of cognitive performance at high age. Neuroimage 174, 308–316. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.03.021

van Bergen, J. M., Li, X., Hua, J., Schreiner, S. J., Steininger, S. C., Quevenco, F. C., et al. (2016b). Colocalization of cerebral iron with amyloid beta in mild cognitive impairment. Sci. Rep. 6:35514. doi: 10.1038/srep35514

van Bergen, J. M., Hua, J., Unschuld, P. G., Lim, I. A., Jones, C. K., Margolis, R. L., et al. (2016a). Quantitative susceptibility mapping suggests altered brain iron in premanifest huntington disease. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 37, 789–796. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4617

Verma, R. K., Hsieh, K., Gratz, P. P., Schankath, A. C., Mordasini, P., Zubler, C., et al. (2014). Leptomeningeal collateralization in acute ischemic stroke: impact on prominent cortical veins in susceptibility-weighted imaging. Eur. J. Radiol. 83, 1448–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.05.001

Vinayagamani, S., Sheelakumari, R., Sabarish, S., Senthilvelan, S., Ros, R., Thomas, B., et al. (2021). Quantitative susceptibility mapping: technical considerations and clinical applications in neuroimaging. J Magn. Reson. Imaging 53, 23–37. doi: 10.1002/jmri.27058

Wei, H., Dibb, R., Zhou, Y., Sun, Y., Xu, J., Wang, N., et al. (2015). Streaking artifact reduction for quantitative susceptibility mapping of sources with large dynamic range. NMR Biomed. 28, 1294–1303. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3383

Wharton, S., Schäfer, A., and Bowtell, R. (2010). Susceptibility mapping in the human brain using threshold-based k-space division. Magn. Reson. Med. 63, 1292–1304. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22334

Wisnieff, C., Ramanan, S., Olesik, J., Gauthier, S., Wang, Y., and Pitt, D. (2015). Quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) of white matter multiple sclerosis lesions: interpreting positive susceptibility and the presence of iron. Magn. Reson. Med. 74, 564–570. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25420

Wu, B., Li, W., Avram, A. V., Gho, S. M., and Liu, C. (2012). Fast and tissue-optimized mapping of magnetic susceptibility and T2* with multi-echo and multi-shot spirals. Neuroimage 59, 297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.019

Xu, B., Liu, T., Spincemaille, P., Prince, M., and Wang, Y. (2014). Flow compensated quantitative susceptibility mapping for venous oxygenation imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 72, 438–445. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24937

Yamanaka, T., Uchida, Y., Sakurai, K., Kato, D., Mizuno, M., Sato, T., et al. (2019). Anatomical links between white matter hyperintensity and medial temporal atrophy reveal impairment of executive functions. Aging Dis. 10, 711–718. doi: 10.14336/ad.2018.0929

Yoshiyama, Y., Higuchi, M., Zhang, B., Huang, S. M., Iwata, N., Saido, T. C., et al. (2007). Synapse loss and microglial activation precede tangles in a P301S tauopathy mouse model. Neuron 53, 337–351. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.010

Zhang, J., Liu, T., Gupta, A., Spincemaille, P., Nguyen, T. D., and Wang, Y. (2015). Quantitative mapping of cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) using quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM). Magn. Reson. Med. 74, 945–952. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25463

Zhang, Y., Wei, H., Cronin, M. J., He, N., Yan, F., and Liu, C. (2018). Longitudinal atlas for normative human brain development and aging over the lifespan using quantitative susceptibility mapping. Neuroimage 171, 176–189. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.01.008

Zhao, Z., Zhang, L., Wen, Q., Luo, W., Zheng, W., Liu, T., et al. (2021). The effect of beta-amyloid and tau protein aggregations on magnetic susceptibility of anterior hippocampal laminae in Alzheimer’s diseases. Neuroimage 244:118584. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118584

Zheng, W., Haacke, E. M., Webb, S. M., and Nichol, H. (2012). Imaging of stroke: a comparison between X-ray fluorescence and magnetic resonance imaging methods. Magn. Reson. Imaging 30, 1416–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.04.011

Zheng, W., Nichol, H., Liu, S., Cheng, Y. C., and Haacke, E. M. (2013). Measuring iron in the brain using quantitative susceptibility mapping and X-ray fluorescence imaging. Neuroimage 78, 68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.022

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, biomarker, imaging, MRI, quantitative susceptibility mapping

Citation: Uchida Y, Kan H, Sakurai K, Oishi K and Matsukawa N (2022) Quantitative susceptibility mapping as an imaging biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease: The expectations and limitations. Front. Neurosci. 16:938092. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.938092

Received: 06 May 2022; Accepted: 14 July 2022;

Published: 05 August 2022.

Edited by:

Yuyao Zhang, ShanghaiTech University, ChinaReviewed by:

Cesar V. Borlongan, University of South Florida, United StatesTakao Yasuhara, Okayama University, Japan

Yuki Kanazawa, Tokushima University, Japan

Hidenao Fukuyama, Kyoto University, Japan

Lihui Wang, Guizhou University, China

Copyright © 2022 Uchida, Kan, Sakurai, Oishi and Matsukawa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuto Uchida, dWNoaWRheXV0bzA3MjBAeWFob28uY28uanA=; Noriyuki Matsukawa, bm9yaW1AbWVkLm5hZ295YS1jdS5hYy5qcA==

Yuto Uchida

Yuto Uchida Hirohito Kan

Hirohito Kan Keita Sakurai

Keita Sakurai Kenichi Oishi

Kenichi Oishi Noriyuki Matsukawa

Noriyuki Matsukawa