95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Neurosci. , 25 August 2022

Sec. Neurogenesis

Volume 16 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.904573

The m6A methylation is reported to function in multiple physiological and pathological processes. However, the functional relevance of m6A modification to post-spinal cord injured (SCI) damage is not yet clear. In the present study, methylated RNA immunoprecipitation combined with microarray analysis showed that the global RNA m6A levels were decreased following SCI. Then, gene ontology (GO) and kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) analyses were conducted to demonstrate the potential function of differential m6A-tagged transcripts and the altered transcripts with differential m6A levels. In addition, we found that the m6A “writer,” METTL3, significantly decreased after SCI in mice. The immunostaining validated that the expression of METTL3 mainly changed in GFAP or Iba-1+ cells. Together, this study shows the alteration of m6A modification following SCI in mice, which might contribute to the pathophysiology of the spinal cord after trauma.

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a devastating pathological status that results in persistent functional deficits and high mortality (Ahuja et al., 2017). The prevalent cases of SCI were approximately 27.04 million worldwide (GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators, 2019). Numerous significant advances in medical treatment have been achieved in experimental SCI models, but no definitive therapies exist for SCI in the clinic. The development of an effective treatment strategy is limited by an incomplete understanding of the pathological mechanisms that occur at different stages after SCI. The intricate biological processes and molecular events, namely, excitotoxicity, ionic imbalance, oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum stress, apoptosis, and inflammation, govern the neuronal fate and affect neurological functional recovery after SCI (Mehta et al., 2007; Fan et al., 2018). In recent years, RNA modification has been reported to function in these biological processes and molecular events (Wen et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021b; Yang and Chen, 2021; Yu et al., 2021; He et al., 2022).

In the process of epigenetic regulation, RNAs, which are similar to DNA or histone, could undergo over 100 kinds of posttranscriptional modifications in mammals (Cantara et al., 2011; Niu et al., 2013). The internal epi-transcriptomic changes include N1-methyladenosine (m1A), N5-methylcytosine (m5C), N6-methyladenosine (m5A), and pseudouridine (ψ; Wei et al., 2018; Weng et al., 2018). Among them, m6A, which can regulate RNA structure, stability, and expression, is regarded as the most universal and reversible modification of all messenger RNA (mRNA) and non-coding RNA base methylations in eukaryotic cells (Roundtree et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2017; Frye et al., 2018). The latest research shows that m6A modification is mediated mainly by various “writer,” “reader,” and “eraser” proteins (Meyer and Jaffrey, 2017), such as methyltransferase-like (METTL) 3 and 14, Wilms tumor 1-associating protein (WTAP), YTH domain-containing family protein 2 (YTHDF2), fat mass and obesity-associated protein FTO), and AlkB homology 5 (ALKBH5; Yang et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2021). METTL-3 and -14, and WTAP primarily mediate the conversion of adenosine to m6A, while demethylases FTO and ALKBH5 can reverse this modification (Widagdo and Anggono, 2018).

Emerging evidence has reported that m6A modification is strongly associated with multiple physiological and pathological processes, such as ischemic stroke, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and peripheral nerve injury (Weng et al., 2018; Chokkalla et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Si et al., 2020). As of late, Wang et al. have reported that m6A modification was significantly changed in the early period of TBI in mice by m6A modified RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (m6A-RIP-seq) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq; Wang et al., 2019). In the sciatic nerve lesion model, the m6A-tagged transcripts encode many regeneration-associated genes and protein translation machinery components in the adult mouse dorsal root ganglion (DRG; Weng et al., 2018). However, the role of m6A in SCI remains to be characterized.

This study systematically profiled RNA m6A modification landscape by m6A-mRNA and lncRNA Epi-transcriptomic microarray in the mouse SCI model. We found altered m6A methylation levels following SCI, leading to the change of m6A-tagged transcripts. Furthermore, we screened and found that the decreased METTL3-mediated m6A modification may be responsible for the hypo-methylation following SCI. Together, this study suggests that m6A modifications are involved in the process of SCI, which may be a promising therapeutic target.

To investigate the role of m6A modification in SCI, we established the mouse model with SCI and extracted spinal cord tissues 3 days after surgery. The levels of m6A modifications were evaluated by methylated RNA immunoprecipitation and transcriptional microarray analysis. The global m6A levels in the SCI group were significantly decreased compared with the sham group, as revealed by the immunofluorescent intensity of cy5-labeled immunoprecipitation in the microarray images (Figures 1A,B). Consistent with the global m6A analysis, the levels of transcript-specific m6A modification in mRNAs and lncRNAs were also significantly lower in the SCI group than in the sham group (Figures 1B–D). The microarray profiling showed that the m6A levels were significantly decreased in 98% mRNAs (194 hyper- and 11,059 hypo-methylation; Figure 1E and Supplementary Table 1) and 97% lncRNAs (46 hyper- and 1,556 hypo-methylation) in the SCI group compared with the sham group (Figures 1D–F and Supplementary Table 2). Together, these data indicated that the global m6A methylation levels decreased in the SCI group compared with the sham group, especially the m6A enrichment of mRNAs and LncRNAs.

Figure 1. Decrease of the global m6A level post-SCI in mice. (A) The representative array of images of the SCI group and sham group. Cy3 for Sup and Cy5 for IP. (B) Fold change of the immunofluorescent intensity of cy5-labeled immunoprecipitation in the microarray images from SCI group over sham group. (C) The heatmap of mRNA m6Amethylation level in SCI group and sham group. (D) The heatmap of LncRNA m6A methylation level in SCI group and sham group. (E,F) The volcano plot of mRNA methylation level (194 hyper- and 11,059 hypo-methylation) (E) and LncRNA methylation level (46 hyper- and 1,556 hypo-methylation) (F) in the SCI group over the sham group. The threshold lines are set at |fold change| ≥ 1.5 and p < 0.05 between SCI and sham. n = 4/group.

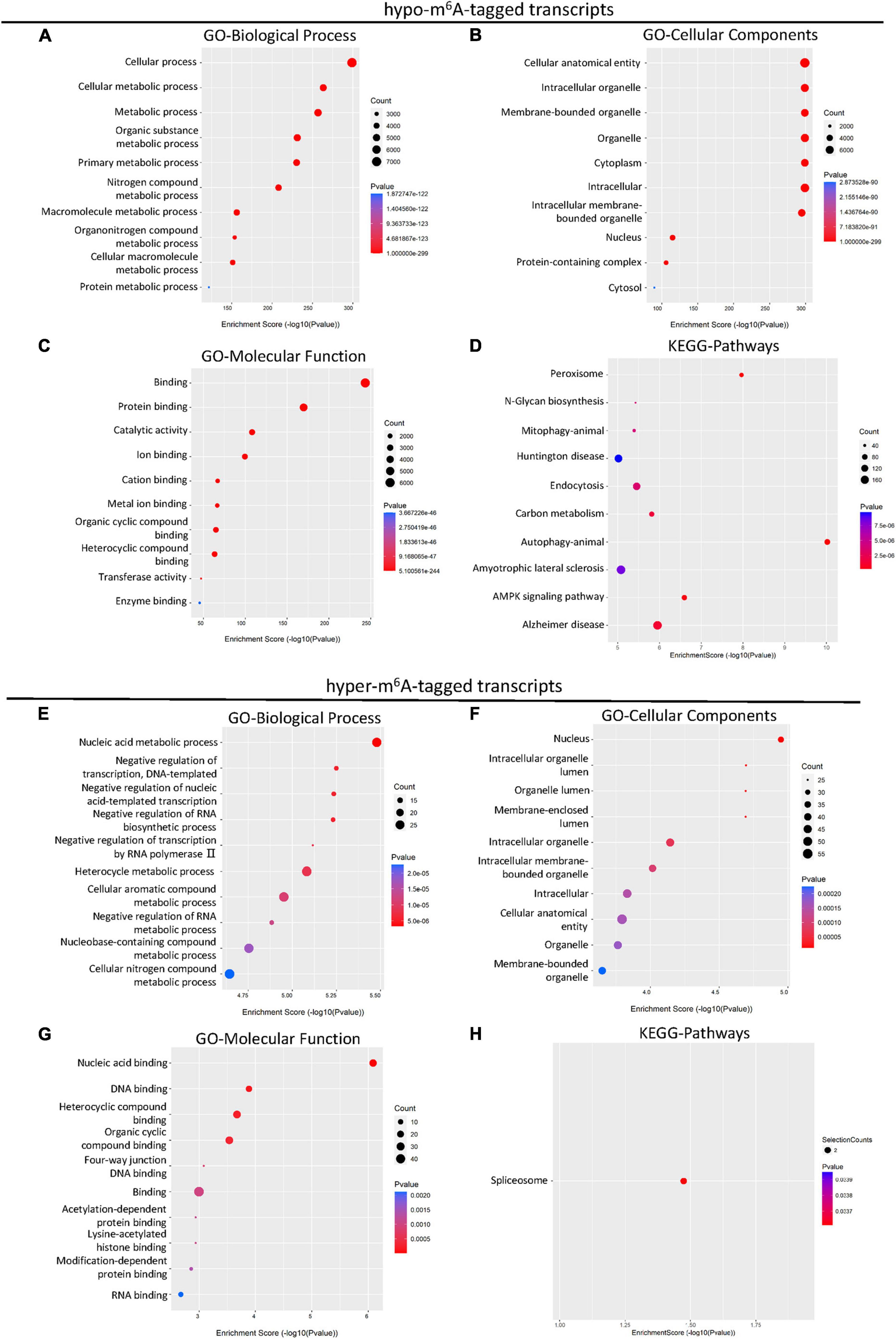

It has been reported that m6A methylation played an essential role in the regulation of mRNA translation in the CNS system (Merkurjev et al., 2018). To further demonstrate the potential function of differential m6A-tagged transcripts (mRNAs) after SCI, gene ontology (GO) analysis, and kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) analysis were conducted. The results of GO analysis indicated that the hypo-m6A-tagged transcripts after the SCI were mainly enriched in the biological process (BP) of the cellular and metabolic processes (Figure 2A). These hypo-m6A-tagged transcripts were enriched in the cellular anatomical entity, organelle, and cytoplasm revealed by cellular components (CCs) analysis (Figure 2B). In addition, the molecular functions (MF) of the hypo-m6A-tagged transcripts were highly enriched in binding, catalytic activity, and transferase activity (Figure 2C). Moreover, KEGG enrichment was analyzed. The mRNAs with hypo-m6A modification after SCI were primarily involved in several pathways namely peroxisome, N-Glycan biosynthesis, mitophagy, endocytosis, carbon metabolism, autophagy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and AMPK signaling (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. KEGG and GO enrichment analysis of differential m6A-tagged transcripts after SCI. (A–C) Gene ontology (GO) analysis of hypo-m6A-tagged transcripts for biological process (BP), cellular components (CC), molecular function (MF) in the SCI group over the sham group. (D) KEGG pathway analysis of hypo-m6A-tagged transcripts in SCI group over sham group. (E–G) Gene ontology (GO) analysis of hyper-m6A-tagged transcripts for biological process (BP), cellular components (CC), molecular function (MF) in SCI group over sham group. (H) KEGG pathway analysis of hyper-m6A-tagged transcripts in SCI group over sham group.

Different from hypo-m6A-tagged mRNA, hyper-m6A-tagged mRNAs were predominantly enriched in BP of nucleic acid metabolism, negative regulation of transcription, and negative regulation of biosynthetic process after the SCI in the GO analysis (Figure 2E). Cellular components analysis demonstrated that hyper-m6A-tagged transcripts were mainly enriched in the nucleus, organelle, and its lumens (Figure 2F). The MF enrichments were primarily found in binding terms (Figure 2G). In addition, the KEGG analysis demonstrated that only the spliceosome-related pathway was significantly associated with the hyper-m6A-tagged mRNAs (Figure 2H).

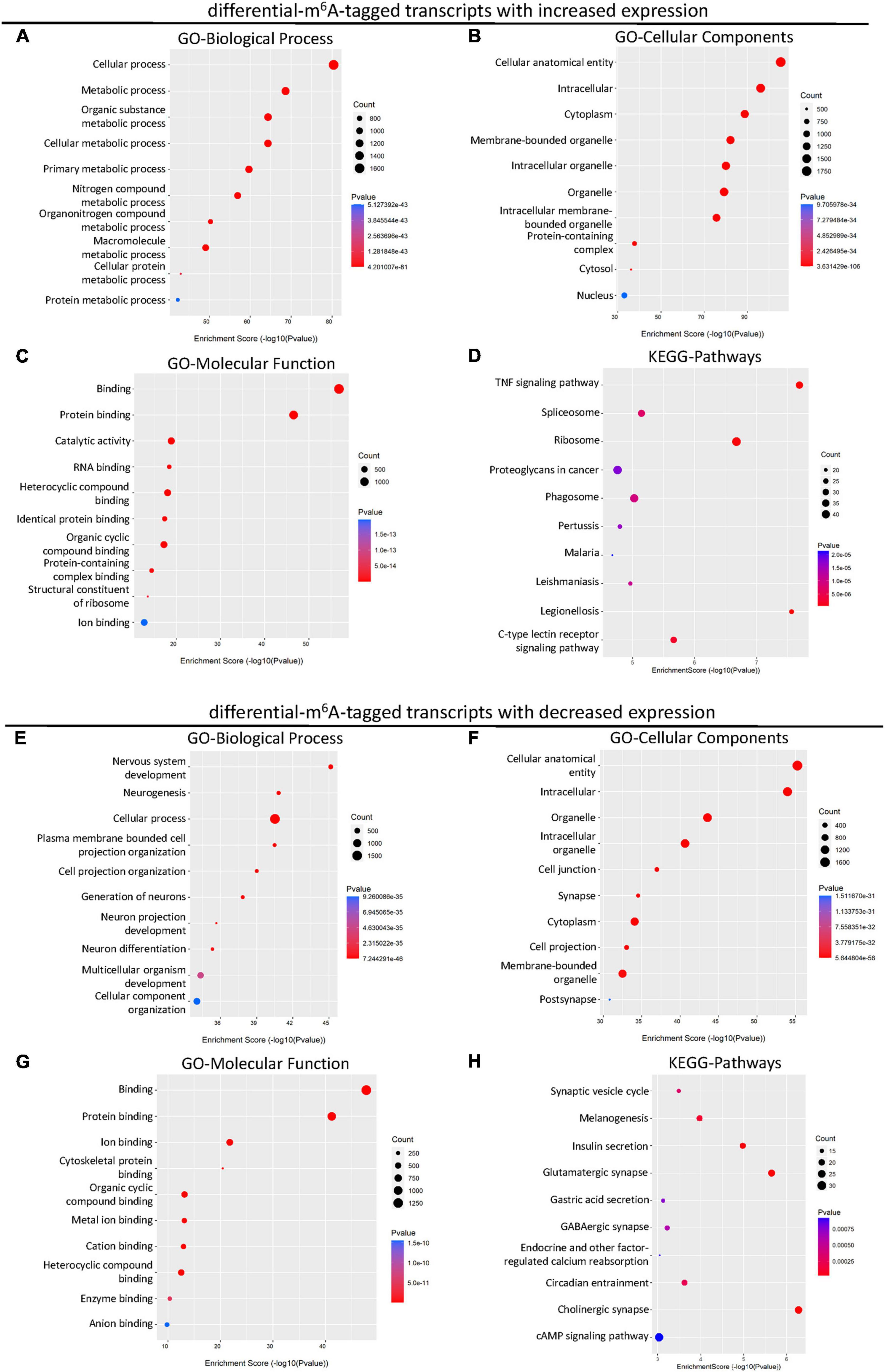

Considering the changed m6A level of transcripts may not lead to the differences in gene expression, we next explored the differentially expressed genes with altered m6A modification after SCI. A total of 2,895 up-regulated and 697 down-regulated mRNA with m6A methylation were identified after the SCI (Figure 4A). Then, to reveal the potential role of differentially expressed mRNA, GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were conducted. The GO analysis showed that the up-regulated genes were primarily involved in the cellular and metabolic processes (Figure 3A) and enriched in the cellular anatomical entity, intracellular, cytoplasm, and organelle (Figure 3B). The enrichment of MF was found in binding, catalytic activity, and structural constituent of ribosome (Figure 3C). In addition, the KEGG analysis indicated that the up-regulated mRNAs were significantly related to TNF signaling, spliceosome, ribosome, proteoglycans in cancer, phagosome, and C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. KEGG and GO enrichment analysis of the altered transcripts modified by differential m6A after SCI. (A–C) Gene ontology (GO) analysis of differential m6A-tagged transcripts with increased transcription levels for biological process (BP), cellular components (CC), molecular function (MF) in SCI group over sham group. (D) KEGG pathway analysis of differential m6A-tagged transcripts with increased transcription levels in SCI group over sham group. (E–G) Gene ontology (GO) analysis of differential m6A-tagged transcripts with decreased transcription levels for biological process (BP), cellular components (CC), molecular function (MF) in SCI group over sham group. (H) KEGG pathway analysis of differential m6A-tagged transcripts with decreased transcription levels in SCI group over sham group.

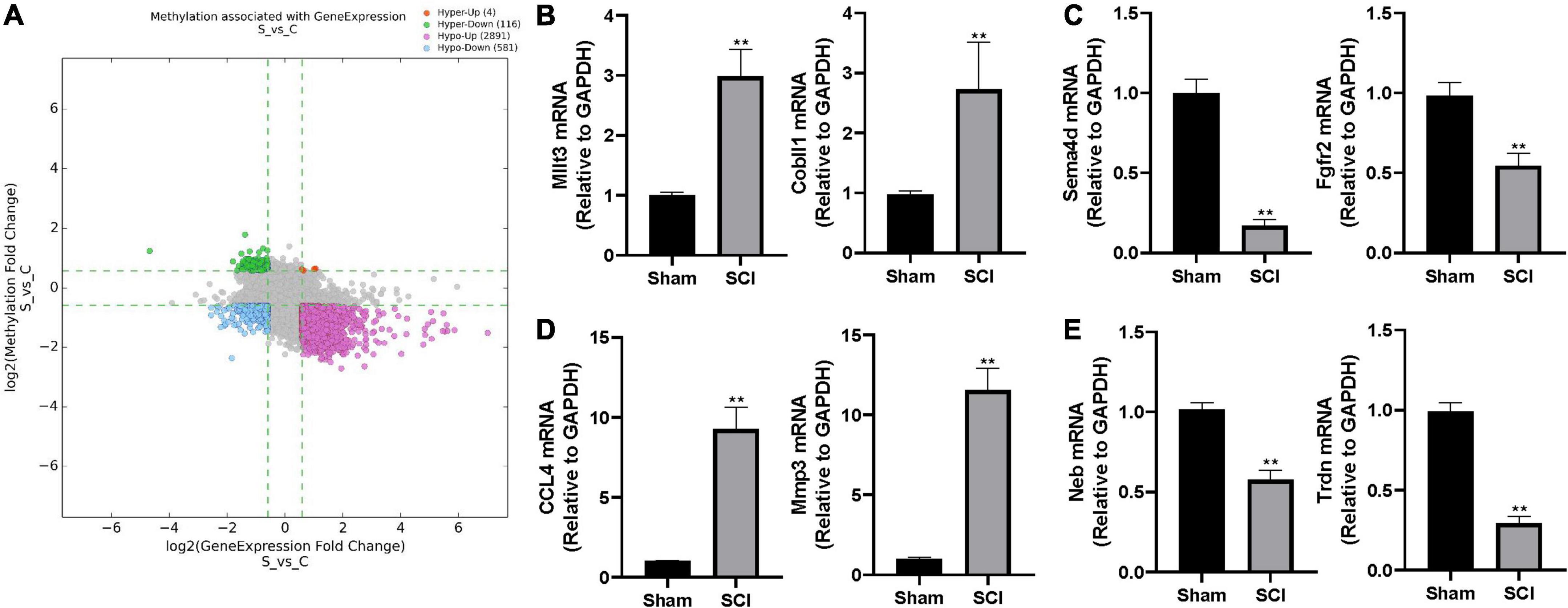

Figure 4. The altered m6A level associated with changed gene expression. (A) The scatter plot of altered m6A level associated with changed gene expression. The threshold lines are set at |fold change| ≥ 1.5 between SCI and sham. Hyper: hypermethylation, Hypo: hypomethylation, up: increased gene expression, down: decreased gene expression. (B–E) Validation of randomly selected two genes in different groups by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) after SCI. (B) hyper-up group, (C) hyper-down group, (D) hypo-up group, (E) hypo-down group. Bars indicate mean ± SD; n = 5 per group. **p < 0.01 compared with sham group.

In addition, we analyzed down-regulated genes with altered m6A modification. The GO analysis showed that these down-regulated mRNAs were primarily enriched in the BP of cellular process, nervous system development, multicellular organism development, and cellular component organization (Figure 3E). They were mainly located in the cellular anatomical entity, intracellular components, organelle, cell junction, synapse, cytoplasm, cell projection, and post synapse (Figure 3F). The enrichment of MF was primarily found in the binding (Figure 3G). The down-regulated mRNAs were significantly involved in pathways namely, synaptic vesicle cycle, melanogenesis, insulin secretion, glutamatergic synapse, gastric acid secretion, GABAergic synapse, endocrine, and other factor-regulated calcium reabsorption, circadian entrainment, cholinergic synapse, and cAMP signaling (Figure 3H).

To further characterize the differentially expressed genes with altered m6A level, we categorized the up-/down-regulated transcripts into four groups: m6A hypermethylation with up-regulated transcription levels (hyper-up, 4 genes), m6A hypermethylation with down-regulated transcription levels (hyper-down, 116 genes), m6A hypomethylation with up-regulated transcription levels (hypo-up, 2891 genes), m6A hypomethylation with down-regulated transcription levels (hypo-down, 581 genes; Figure 4A and Supplementary Table 3). We randomly selected two genes from each group and performed real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) to validate the above observations in the epitranscriptomic microarray analysis. Consistent with our findings, mRNA expressions of Mllt3 and Cobll1 in the hyper-up group were significantly increased after the SCI; whereas the mRNA expression levels of Sema4d and Fgfr2 in the hyper-down group were remarkably decreased after the SCI (Figures 4B,C). The qRT-PCR showed that the expression of CCL4 and Mmp3 increased significantly after the SCI in the hypo-up group (Figure 4D), while, the mRNA levels of Neb and Trdn in hypo-down group were notably lower in the Tran SCI group compared with the sham group (Figure 4E).

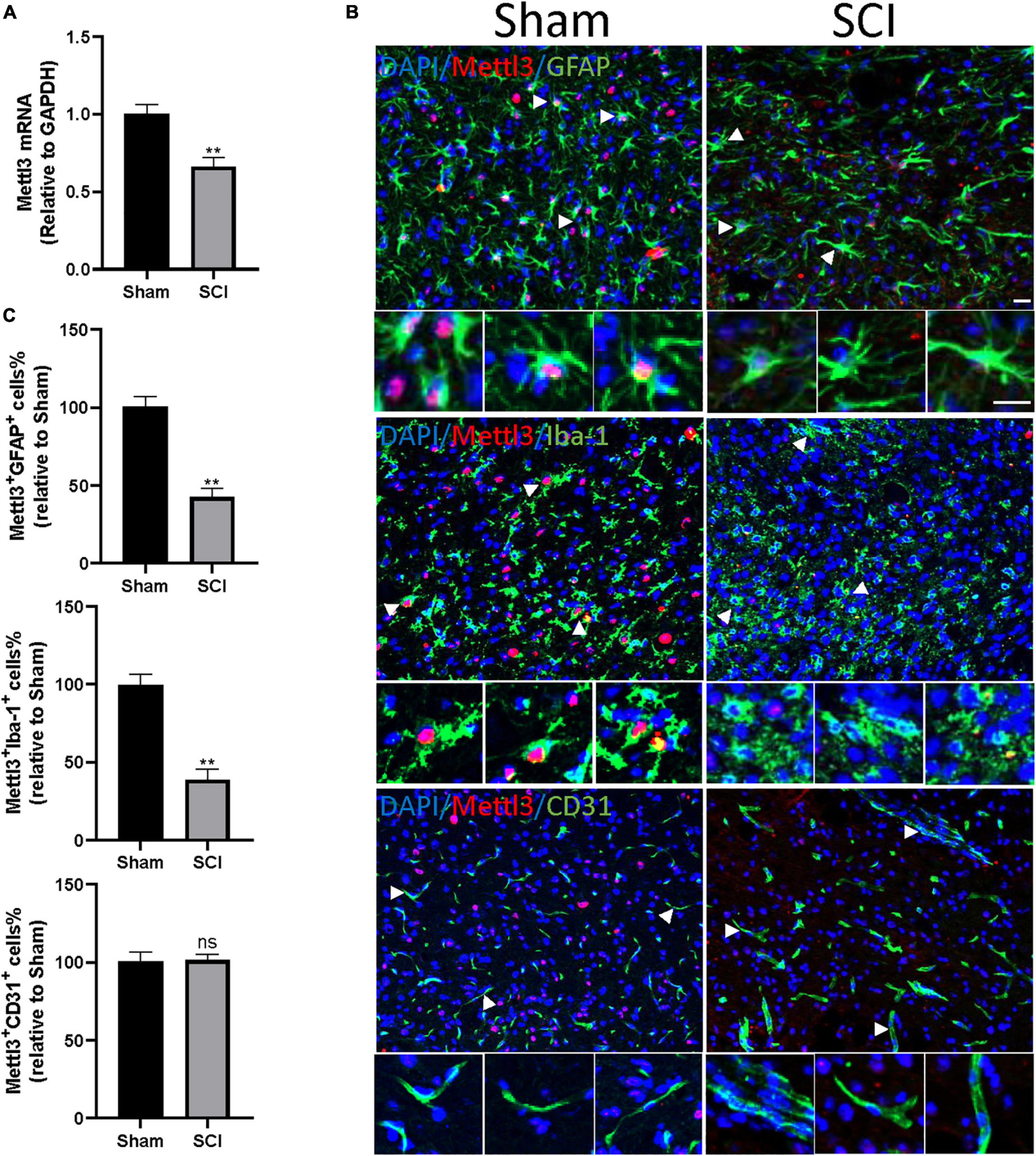

S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) is a common substrate that functions as a methyl donor for most methyltransferases in important biochemical reactions. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) showed that the concentration of SAM did not change significantly after the SCI compared to the sham group (Supplementary Figure 1). To further explore the key regulator in the m6Amodification after SCI, the expression of m6A methylase complex subunits (METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP) and m6A demethylase (FTO and YTHDF2) were screened based on the m6A-mRNA and lncRNA Epitranscriptomic Microarraythe RNA-sequence database. A significant decrease in the mRNA expression of METTL3 was observed 3 days after the SCI, consistent with the above observation of the global m6A level (Supplementary Table 1). METTL3 is essential to catalyze m6A-dependent methylation (Liu et al., 2014). To validate the change of METTL3 in the mouse SCI model, qRT-PCR analysis was conducted. The SCI surgery significantly diminished the expression of METTL3 compared with the sham group (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. METTL3 is decreased in GFAP+ or Iba-1+ cells following SCI. (A) The decrease of METTL3 mRNA level by qRT-PCR at 3 days after SCI. (B) Representative images of spinal cord sections stained for METTL3 (red) with GFAP (green) or Iba-1 (green) or CD31 (green) at 3 days after the SCI and sham group. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Percentage of number of METTL3+GFAP+, METTL3+Iba-1+, and METTL3+CD31+ in SCI group relative to the sham group. Bars indicate mean ± SD; n = 5/group. **p < 0.01 compared with the sham group. ns, no significance.

We then sought to demonstrate the distribution of METTL3 in different cell types of the spinal cord after trauma. The immunofluorescent staining of METTL3 revealed that the METTL3+ cells were positive for astrocyte marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and macrophage/microglia marker allograft inflammatory factor 1 (Iba1), but rarely expressed endothelial marker CD31 (Figure 5B). Interestingly, the numbers of METTL3+GFAP+ and METTL3+Iba-1+ cells were significantly lower in the SCI group than in the sham group; while, no significant change in METTL3+CD31+ cells was observed after the SCI surgery (Figure 5C). In conclusion, these results demonstrate that the change of METTL3 expression after SCI mainly occurred in GFAP+ astrocytes, and Iba-1+ macrophage/microglia cells.

The SCI is catastrophic trauma of the central nervous system (CNS) that can initiate multiple biological processes and molecule events (Ahuja et al., 2017). As a key mechanism to mediate gene transcription, epigenetics plays a critical role in the response to trauma in the mammalian nervous system (Meng et al., 2017). However, far too few studies have focused on epigenetic changes in SCI (Finelli et al., 2013; Crunkhorn, 2019). Our previous study demonstrated that the epigenetic network is essential for vascular regeneration and functional recovery post-SCI (Ni et al., 2019). The m6A methylation plays a significant role in the pathological process of corneal injury, brain injury, and peripheral nerve injury (Weng et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019; Dai et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). In contrast, various types of cancers and diabetes are associated with lowered m6A abundance (Chen et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2021; Lei et al., 2021; Ruan et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021a; Ye et al., 2021). Therefore, m6A homeostasis might be essential for normal physiology, and its disorder leads to pathologies. Nevertheless, the functional relevance of m6A modification to post-SCI damage is not yet clear. In the present study, we first demonstrate the m6A landscape in the SCI model of mice. The methylated RNA immunoprecipitation combined with microarray analysis showed that the global RNA m6A levels were decreased following the SCI. These results indicate that the changed m6A modification may involve the pathologies of tissue damage in SCI.

Then, we performed profiling of m6A-tagged mRNA and LncRNA after the SCI in mice. Consistent with the decreased global m6Amethylation level, 11253 m6A peaks were differentially expressed in mRNA transcriptomes after SCI, namely 194 up-regulated and 11,059 down-regulated. In a similar manner, 46 m6A peaks were elevated and 1,556 m6A peaks were decreased in LncRNA transcriptomes after the SCI. Interestingly, most differential m6A-tagged mRNA transcriptomes were hypomethylated, but their transcriptional levels were up-regulated after SCI. This indicates that the level of m6A methylation negatively correlated with the transcriptional levels after SCI. Consistently, several previous studies reported that m6A mainly functioned in mRNA degradation (Dominissini et al., 2012; Meyer et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014).

We found that the BP of differential m6A-tagged transcripts post SCI were enriched in the cellular and metabolic processes, implying that m6A modification may contribute to metabolic alteration after SCI. In general, SCI results in transient or persistent spinal cord metabolic disorder because of post-traumatic ischemia, inflammation, and other mechanisms (Fan et al., 2018), representing m6A modification as a potential therapeutic target in the metabolic process after SCI for further study. Cellular Components (CC) of GO analysis suggested that these transcripts were enriched in the cellular anatomical entity, cytoplasm, nucleus, and intracellular organelle, indicating genes modified by m6A were widespread in cells following the SCI. In addition, the MF of these hypo- and hyper-methylated genes are enriched in binding, protein binding, and nucleic acid binding, consistent with the broad and critical roles of RNA methylation in gene expression regulation. The KEGG analysis showed that the m6A-tagged transcripts were enriched in several pathways, namely spliceosome, peroxisome, autophagy, mitophagy, endocytosis, carbon metabolism, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and AMPK signaling, indicating the m6A modification may participate in the processes of oxidative stress, autophagy, metabolism, and nervous systems diseases.

Considering the changed m6A level of transcripts may not lead to the differences in gene expression, we next conducted the GO and KEGG analyses of the differentially expressed genes with altered m6A modification after SCI. Similar to the BP of differential m6A-tagged transcripts, the up-regulated transcripts were enriched in the cellular process, cellular metabolic process, and metabolic process. However, noticeably, the down-regulated transcripts were enriched in nervous system development, neurogenesis, and cellular process, indicating the decay of tagged neurodevelopment-and neurogenesis-related transcripts after the SCI. The KEGG analysis showed that the up-regulated transcripts were enriched in the TNF signaling pathway, ribosome, legionellosis, C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway, phagosome, and spliceosome, suggesting m6A modification promotes inflammation-related transcripts following the SCI. However, the down-regulated transcripts were enriched in the cholinergic synapse, glutamatergic synapse, insulin secretion, melanogenesis, synaptic vesicle cycle, and circadian entrainment. This indicates that m6A-tagged transcripts are involved in synaptic growth, synaptic assembly, and metabolism, thus influencing the communication between axons post-SCI.

The METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP mainly regulate the methylation process of m6A, while the FTO and ALKBH5 can reverse this modification (Widagdo and Anggono, 2018; Yang et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2021). Our results showed that only one transcript’s mRNA level of METTL3 significantly decreased post-SCI among these key enzymes in regulating m6A modification (Supplementary Table 4). The subsequent qRT-PCR and immunofluorescence data verified the change of METTL3 in mRNA expression and protein expression post-SCI. The mRNA level of another three transcripts of METTL3 did not change significantly, which means that they might not be involved in the change of METTL3 post-SCI. Recent increasing evidence suggests that METTL3, a key RNA N6-adenosine methyltransferase, is involved in the regulation of the nervous system (Hess et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). The METTL3 is abundantly enriched neurogenesis during the early stage (Yoon et al., 2017). Furthermore, conditional METTL3 knockout (cKO) in mice impairs the differentiation of embryonic neural progenitor cells, prolongs cell cycle progression of radial glia, and extends cortical neurogenesis into postnatal stages (Yoon et al., 2017). In addition, silencing METTL3 could significantly promote cell proliferation and migration and induce G0/G1 arrest in some cancers (Li et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018; Visvanathan et al., 2018). The present study revealed that METTL3 was decreased in the early stage after SCI and predominantly localized and down-regulated explicitly in the GFAP+ or Iba-1+ cells. Function tests are required to elucidate the effects of the decreased METTL3 on astrocytes or macrophage/microglia after SCI.

Noticeably, the expression of FTO also decreased after the SCI. However, as the RNA demethylase, the change of FTO was inversely correlated with the altered m6A level (Weng et al., 2018; Mathiyalagan et al., 2019). Hence, the change of METTL3 was consistent with the decreased trend of global m6A after the SCI.

In conclusion, we find that both the level of global m6A and the expression of METTL3 are significantly decreased in the mouse SCI model. Profiling of m6A-tagged transcripts and subsequent bioinformatics analysis reveal the potential functions of altered m6A modified transcripts. Our study suggests that m6A modifications could be a potential therapeutic target for SCI.

All the experimental animal protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University for Scientific Research. The animals were kept in specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions in the Department of Laboratory Animals. The animals were housed in identical environments (temperature 22–24°C; humidity 60–80%) on a 12-h light–dark cycle and fed standard rodent chow ad libitum with free unlimited food and water. The 2-month-old mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. After laminectomy at T10, moderate contusion injury of the spinal cord was instigated by a modified Allen’s weight drop mechanical assembly (10 g weight at a vertical height of 20 mm, 10 g x 20 mm). Mice in the sham group were only subjected to laminectomy without contusion. Bladders were physically kneaded twice daily until full voluntary or autonomic voiding. Antibiotic (penicillin sodium; North China Pharmaceutical, Shijiazhuang, China) was administered once daily for 3 days post-surgery.

The 3 μg total RNA and m6A spike-in control mixture was added to 300 μl 1 × IP buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP40, 40U/μl RNase Inhibitor) containing 2 μg anti-m6A rabbit polyclonal antibody (Synaptic Systems). The reaction was incubated with head-over-tail rotation at 4°C for 2 h. Dynabeads™ M-280 Sheep Anti-Rabbit IgG (Invitrogen) suspension was blocked with freshly prepared 0.5% BSA at 4°C for 2 h and resuspended in the total RNA-antibody mixture prepared earlier. Then beads were then washed three times with 1 × IP buffer and twice with wash buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP40, 40 U/μl RNase Inhibitor). The enriched RNA was eluted with Elution buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% SDS, 40U Proteinase K) at 50°C for 1 h. The RNA was extracted by acid phenol–chloroform and ethanol precipitated. The immunoprecipitated “IP” fraction contained enriched m6A methylated RNAs, and the supernatant “Sup” fraction contained unmodified RNAs.

The “IP” RNAs and “Sup” RNAs were added with equal amounts of calibration spike-in control RNA, amplified as cRNAs, and labeled with Cy3 (green for “Sup”) and Cy5 (red for “IP”) separately using Arraystar Super RNA Labeling Kit (Arraystar). The synthesized cRNAs were further purified by RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Then Cy3 and Cy5 labeled cRNAs were combined together and were fragmented. Then, 50 μl hybridization solution was dispensed into the gasket slide and assembled to the mouse m6A-mRNA and lncRNA Epitranscriptomic Microarray Arrays (8 × 60 K, Arraystar, Rockville, MD, United States at 65°C for 17 h in an Agilent Hybridization Oven. The hybridized arrays were washed, fixed, and scanned in two-color channels using an Agilent Scanner G2505C. Agilent Feature Extraction software (version 11.0.1.1) was used to analyze acquired array images. Raw intensities of “IP” and “Sup” were normalized with an average of log2-scaled spike-in RNA intensities. The “m6A methylation level” was calculated for the percentage of modification based on the “IP” and “Sup” normalized intensities.

The hierarchical clustering heatmap analysis was performed using the heatmap.2 function in the gplots R package. The heatmaps of differentially m6A-methylated lncRNAs and mRNAs were generated and clustered based on the Euclidean distance matric. The present clustergrams represent each transcripts’ row of data across each of the columns of variables as a color block, using stronger intensities of blue color to represent lower levels of the m6A methylation, and increasing intensities of red color to represent higher levels. The volcano plot analysis was performed using the ggplot2. function in the gplots R package. The GO analysis was performed using the topGO package in the R environment for statistical computing and graphics, and Pathway analysis was calculated by Fisher’s exact test.

The spinal cord sections were washed in PBS for 15 min, then with 1% PBST (1% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 30 min two times. The slices were incubated with a blocking solution (5% BSA in 1% PBST) at room temperature for 1 h. Primary antibodies, namely, anti-METTL3 (Abcam, ab195352, and 1:500), anti-CD31 (R&D Systems, Inc., FAB3628G-100, and 1:200), anti-GFAP (Abcam, ab53554, and 1:500), anti-Iba-1 (Wako, 01127991, and 1:800) were incubated at 4°C overnight. The corresponding secondary antibodies (Abcam and 1:500) were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. There were five samples in the Sham and SCI group, respectively. For each sample, we selected five slices, and five fields of view for each slice under 200⋅magnification. The range of each field of view is 600 × 500 μm, and there are 915 ± 85.5 cells on an average in each field of view. In total, 2.5⋅104 cells were used for each sample for cell count.

The spinal cord tissue for RNA isolation is 1 cm in length, around the injury site. According to the manufacturer’s protocol, total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen). The qRT-PCR was performed using the PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (Takara) and SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara) following the specifications. For the quantification of mRNA expression, primers were provided by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). The expression of GAPDH was used as an internal control. The analysis of gene expression was performed using the 2 –ΔΔCt method.

The spinal cord tissues were collected from the SCI group and the Sham group. The tissue supernatant was prepared and the concentration of SAM was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Cloud-Clone Corp., Wuhan, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (n = 4 per group), respectively.

All the data were presented in the form of means ± SD. The t-test was used to compare the differences between the groups. All the statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 19.0 software. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

This animal study was reviewed and approved by Ethics Review Committee in Life Science of Zhengzhou University.

SN: data curation, formal analysis, and writing – original draft. ZL: writing – original draft, methodology, and data curation. YF: project administration and methodology. WZ: validation and investigation. WP: writing – review and editing and supervision. HZ: funding acquisition and writing – review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82072431, 81902215, U2004113, and 82002353), Key Specialized Research and Development breakthrough Program in Henan province (202102310125), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Central South University (2020zzts265).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2022.904573/full#supplementary-material

Ahuja, C. S., Wilson, J. R., Nori, S., Kotter, M. R. N., Druschel, C., Curt, A., et al. (2017). Traumatic spinal cord injury, nature reviews. Dis. Primers 3:17018. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.18

Cantara, W. A., Crain, P. F., Rozenski, J., McCloskey, J. A., Harris, K. A., Zhang, X., et al. (2011). The RNA Modification Database, RNAMDB: 2011 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D195–D201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1028

Chen, M., Wei, L., Law, C. T., Tsang, F. H., Shen, J., Cheng, C. L., et al. (2018). RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase-like 3 promotes liver cancer progression through YTHDF2-dependent posttranscriptional silencing of SOCS2. Hepatology 67, 2254–2270. doi: 10.1002/hep.29683

Chen, Y., Zhou, C., Sun, Y., He, X., and Xue, D. (2020). m(6)A RNA modification modulates gene expression and cancer-related pathways in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Epigenomics 12, 87–99. doi: 10.2217/epi-2019-0182

Chokkalla, A. K., Mehta, S. L., Kim, T., Chelluboina, B., Kim, J., and Vemuganti, R. (2019). Transient focal ischemia significantly alters the m(6)a epitranscriptomic tagging of RNAs in the brain. Stroke 50, 2912–2921. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.026433

Crunkhorn, S. (2019). Epigenetic route to recovery for spinal cord injury. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18:420. doi: 10.1038/d41573-019-00073-0

Dai, Y., Cheng, M., Zhang, S., Ling, R., Wen, J., Cheng, Y., et al. (2021). METTL3-mediated m(6)A RNA modification regulates corneal injury repair. Stem Cells Int. 2021:5512153. doi: 10.1155/2021/5512153

Dominissini, D., Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S., Schwartz, S., Salmon-Divon, M., Ungar, L., Osenberg, S., et al. (2012). Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 485, 201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature11112

Fan, B., Wei, Z., Yao, X., Shi, G., Cheng, X., Zhou, X., et al. (2018). Microenvironment imbalance of spinal cord injury. Cell Transplant. 27, 853–866. doi: 10.1177/0963689718755778

Finelli, M. J., Wong, J. K., and Zou, H. (2013). Epigenetic regulation of sensory axon regeneration after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 33, 19664–19676. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0589-13.2013

Frye, M., Harada, B. T., Behm, M., and He, C. (2018). RNA modifications modulate gene expression during development. Science 361, 1346–1349. doi: 10.1126/science.aau1646

GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators (2019). Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 18, 459–480.

He, Y., Wang, W., Xu, X., Yang, B., Yu, X., Wu, Y., et al. (2022). Mettl3 inhibits the apoptosis and autophagy of chondrocytes in inflammation through mediating Bcl2 stability via Ythdf1-mediated m(6)A modification. Bone 154:116182. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2021.116182

Hess, M. E., Hess, S., Meyer, K. D., Verhagen, L. A., Koch, L., Bronneke, H. S., et al. (2013). The fat mass and obesity associated gene (Fto) regulates activity of the dopaminergic midbrain circuitry. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 1042–1048. doi: 10.1038/nn.3449

Huang, L., Zhu, J., Kong, W., Li, P., and Zhu, S. (2021). Expression and prognostic characteristics of m6A RNA methylation regulators in colon cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22:2134. doi: 10.3390/ijms22042134

Lei, L., Bai, Y. H., Jiang, H. Y., He, T., Li, M., and Wang, J. P. (2021). A bioinformatics analysis of the contribution of m6A methylation to the occurrence of diabetes mellitus. Endocr. Connect. 10, 1253–1265. doi: 10.1530/EC-21-0328

Li, X., Tang, J., Huang, W., Wang, F., Li, P., Qin, C., et al. (2017). The M6A methyltransferase METTL3: acting as a tumor suppressor in renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 8, 96103–96116. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21726

Liu, J., Gao, M., He, J., Wu, K., Lin, S., Jin, L., et al. (2021). The RNA m(6)A reader YTHDC1 silences retrotransposons and guards ES cell identity. Nature 591, 322–326. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03313-9

Liu, J., Yue, Y., Han, D., Wang, X., Fu, Y., Zhang, L., et al. (2014). A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 93–95. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1432

Mathiyalagan, P., Adamiak, M., Mayourian, J., Sassi, Y., Liang, Y., Agarwal, N., et al. (2019). FTO-dependent N(6)-methyladenosine regulates cardiac function during remodeling and repair. Circulation 139, 518–532. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.033794

Mehta, S. L., Manhas, N., and Raghubir, R. (2007). Molecular targets in cerebral ischemia for developing novel therapeutics. Brain Res. Rev. 54, 34–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.11.003

Meng, Q., Zhuang, Y., Ying, Z., Agrawal, R., Yang, X., and Gomez-Pinilla, F. (2017). Traumatic brain injury induces genome-wide transcriptomic, methylomic, and network perturbations in brain and blood predicting neurological disorders. EBioMedicine 16, 184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.01.046

Merkurjev, D., Hong, W. T., Iida, K., Oomoto, I., Goldie, B. J., Yamaguti, H., et al. (2018). Synaptic N(6)-methyladenosine (m(6)A) epitranscriptome reveals functional partitioning of localized transcripts. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 1004–1014. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0173-6

Meyer, K. D., and Jaffrey, S. R. (2017). Rethinking m(6)A readers, writers, and erasers. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 33, 319–342. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060758

Meyer, K. D., Saletore, Y., Zumbo, P., Elemento, O., Mason, C. E., and Jaffrey, S. R. (2012). Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3’ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell 149, 1635–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003

Ni, S., Luo, Z., Jiang, L., Guo, Z., Li, P., Xu, X., et al. (2019). UTX/KDM6A deletion promotes recovery of spinal cord injury by epigenetically regulating vascular regeneration. Mol. Ther. 27, 2134–2146. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.08.009

Niu, Y., Zhao, X., Wu, Y. S., Li, M. M., Wang, X. J., and Yang, Y. G. (2013). N6-methyl-adenosine (m6A) in RNA: an old modification with a novel epigenetic function. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 11, 8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2012.12.002

Roundtree, I. A., Evans, M. E., Pan, T., and He, C. (2017). Dynamic RNA modifications in gene expression regulation. Cell 169, 1187–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.045

Ruan, X., Tian, M., Kang, N., Ma, W., Zeng, Y., Zhuang, G., et al. (2021). Genome-wide identification of m6A-associated functional SNPs as potential functional variants for thyroid cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 11, 5402–5414.

Shi, H., Zhang, X., Weng, Y. L., Lu, Z., Liu, Y., Lu, Z., et al. (2018). m(6)A facilitates hippocampus-dependent learning and memory through YTHDF1. Nature 563, 249–253. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0666-1

Si, W., Li, Y., Ye, S., Li, Z., Liu, Y., Kuang, W., et al. (2020). Methyltransferase 3 mediated miRNA m6A methylation promotes stress granule formation in the early stage of acute ischemic stroke. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 13:103. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2020.00103

Visvanathan, A., Patil, V., Arora, A., Hegde, A. S., Arivazhagan, A., Santosh, V., et al. (2018). Essential role of METTL3-mediated m(6)A modification in glioma stem-like cells maintenance and radioresistance. Oncogene 37, 522–533. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.351

Wang, C. X., Cui, G. S., Liu, X., Xu, K., Wang, M., Zhang, X. X., et al. (2018). METTL3-mediated m6A modification is required for cerebellar development. PLoS Biol. 16:e2004880. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2004880

Wang, J., Wang, K., Liu, W., Cai, Y., and Jin, H. (2021a). m6A mRNA methylation regulates the development of gestational diabetes mellitus in Han Chinese women. Genomics 113, 1048–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2021.02.016

Wang, J., Zhang, J., Ma, Y., Zeng, Y., Lu, C., Yang, F., et al. (2021b). WTAP promotes myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by increasing endoplasmic reticulum stress via regulating m(6)A modification of ATF4 mRNA. Aging 13, 11135–11149. doi: 10.18632/aging.202770

Wang, X., Lu, Z., Gomez, A., Hon, G. C., Yue, Y., Han, D., et al. (2014). N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 505, 117–120. doi: 10.1038/nature12730

Wang, Y., Mao, J., Wang, X., Lin, Y., Hou, G., Zhu, J., et al. (2019). Genome-wide screening of altered m6A-tagged transcript profiles in the hippocampus after traumatic brain injury in mice. Epigenomics 11, 805–819. doi: 10.2217/epi-2019-0002

Wei, J., Liu, F., Lu, Z., Fei, Q., Ai, Y., He, P. C., et al. (2018). Differential m(6)A, m(6)Am, and m(1)A demethylation mediated by FTO in the cell nucleus and cytoplasm. Mol. Cell 71, 973.e5–985.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.011

Wen, L., Sun, W., Xia, D., Wang, Y., Li, J., and Yang, S. (2020). The m6A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes LPS-induced microglia inflammation through TRAF6/NF-kappaB pathway. Neuroreport 33, 243–251. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000001550

Weng, Y. L., Wang, X., An, R., Cassin, J., Vissers, C., Liu, Y., et al. (2018). Epitranscriptomic m(6)A regulation of axon regeneration in the adult mammalian nervous system. Neuron 97, 313.e6–325.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.12.036

Widagdo, J., and Anggono, V. (2018). The m6A-epitranscriptomic signature in neurobiology: from neurodevelopment to brain plasticity. J. Neurochem. 147, 137–152. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14481

Yang, B., and Chen, Q. (2021). Cross-talk between oxidative stress and m(6)A RNA methylation in cancer. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2021:6545728. doi: 10.1155/2021/6545728

Yang, Y., Hsu, P. J., Chen, Y. S., and Yang, Y. G. (2018). Dynamic transcriptomic m(6)A decoration: writers, erasers, readers and functions in RNA metabolism. Cell Res. 28, 616–624.

Ye, Y., Feng, W., Zhang, J., Zhu, K., Huang, X., Pan, L., et al. (2021). Genome-wide identification and characterization of circular RNA m(6)A modification in pancreatic cancer. Genome Med. 13:183. doi: 10.1186/s13073-021-01002-w

Yoon, K. J., Ringeling, F. R., Vissers, C., Jacob, F., Pokrass, M., Jimenez-Cyrus, D., et al. (2017). Temporal control of mammalian cortical neurogenesis by m(6)A methylation. Cell 171, 877.e17–889.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.003

Yu, S., Wu, K., Liang, Y., Zhang, H., Guo, C., and Yang, B. (2021). Therapeutic targets and molecular mechanism of calycosin for the treatment of cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. Aging 13, 16804–16815.

Zhang, C., Wang, Y., Peng, Y., Xu, H., and Zhou, X. (2020). METTL3 regulates inflammatory pain by modulating m(6)A-dependent pri-miR-365-3p processing. FASEB J. 34, 122–132. doi: 10.1096/fj.201901555R

Zhang, L., Hao, D., Ma, P., Ma, B., Qin, J., Tian, G., et al. (2021). Epitranscriptomic analysis of m6A methylome after peripheral nerve injury. Front. Genet. 12:686000. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.686000

Keywords: spinal cord injured (SCI), m6A (N6-methyladenosine), METTL3 (methyltransferase like 3), RNA, microarray

Citation: Ni S, Luo Z, Fan Y, Zhang W, Peng W and Zhang H (2022) Alteration of m6A epitranscriptomic tagging of ribonucleic acids after spinal cord injury in mice. Front. Neurosci. 16:904573. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.904573

Received: 25 March 2022; Accepted: 25 July 2022;

Published: 25 August 2022.

Edited by:

Paola Tognini, University of Pisa, ItalyReviewed by:

John W. Cave, InVitro Cell Research, LLC, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Ni, Luo, Fan, Zhang, Peng and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Huafeng Zhang, ZmNjemhhbmdoZkB6enUuZWR1LmNu; Wei Peng, cGVuZ3dlaWtldmluQGhvdG1haWwuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.