- 1Department of Psychosomatic Medicine, People’s Hospital of Deyang, Deyang, China

- 2Department of Neurology, Shanghai Tongren Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

- 3Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Fujian Provincial Hospital, Fuzhou, China

- 4Qingpu Branch, Department of Vascular Surgery, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China

- 5Tianjin Mental Health Center, Tianjin, China

- 6Laboratory of Radiation Oncology and Radiobiology, Fujian Provincial Cancer Hospital, Teaching Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China

- 7Department of Psychiatry, Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China

- 8Department of Neurology, Shanghai General Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 9Department of Psychiatry, Fuzhou Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China

- 10Zhuhai Municipal Maternal and Children’s Health Hospital, Zhuhai, China

- 11Huashan Hospital, Fudan University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 12The First Affiliated Hospital, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China

- 13Minqing Psychiatric Hospital, Minqing, China

- 14Department of Psychiatry, Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai, China

- 15Department of Clinical Medicine, College of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Fuzhou, China

- 16Department of Family and Community Health, School of Nursing, Health Sciences Center, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, United States

- 17Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States

- 18Key Laboratory for Molecular Genetic Mechanisms and Intervention Research on High Altitude Diseases of Tibet Autonomous Region, Xizang Minzu University School of Medicine, Xiangyang, China

- 19Biological Psychiatry Research Center, Beijing Huilongguan Hospital, Beijing, China

Background: Selective loss of dopaminergic neurons and diminished putamen gray matter volume (GMV) represents a central feature of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Recent studies have reported specific effects of kinectin 1 gene (KTN1) variants on the putamen GMV.

Objective: To examine the relationship of KTN1 variants, KTN1 mRNA expression in the putamen and substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), putamen GMV, and PD.

Methods: We examined the associations between PD and a total of 1847 imputed KTN1 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in one discovery sample [2,000 subjects with PD vs. 1,986 healthy controls (HC)], and confirmed the nominally significant associations (p < 0.05) in two replication samples (900 PD vs. 867 HC, and 940 PD vs. 801 HC, respectively). The regulatory effects of risk variants on the KTN1 mRNA expression in putamen and SNc and the putamen GMV were tested. We also quantified the expression levels of KTN1 mRNA in the putamen and/or SNc for comparison between PD and HC in five independent cohorts.

Results: Six replicable and two non-replicable KTN1-PD associations were identified (0.009 ≤ p ≤ 0.049). The major alleles of five SNPs, including rs12880292, rs8017172, rs17253792, rs945270, and rs4144657, significantly increased risk for PD (0.020 ≤ p ≤ 0.049) and putamen GMVs (19.08 ≤ β ≤ 60.38; 2.82 ≤ Z ≤ 15.03; 5.0 × 10–51 ≤ p ≤ 0.018). The risk alleles of five SNPs, including rs8017172, rs17253792, rs945270, rs4144657, and rs1188184 also significantly increased the KTN1 mRNA expression in the putamen or SNc (0.021 ≤ p ≤ 0.046). The KTN1 mRNA was abundant in the putamen and/or SNc across five independent cohorts and differentially expressed in the SNc between PD and HC in one cohort (p = 0.047).

Conclusion: There was a consistent, significant, replicable, and robust positive relationship among the KTN1 variants, PD risk, KTN1 mRNA expression in putamen, and putamen volumes, and a modest relation between PD risk and KTN1 mRNA expression in SNc, suggesting that KTN1 may play a functional role in the development of PD.

Introduction

The nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathway connects the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) with the dorsal striatum, forms part of the extrapyramidal system, and plays a central role in motor control (Tepper and Lee, 2007; Tritsch et al., 2012). Selective loss of dopaminergic neurons in the SNc represents a cardinal pathological feature of Parkinson’s disease (PD), and consequent dopamine depletion in the striatum results in marked motor deficits, including tremors, rigidity, hypokinesia and postural imbalance (Salkov and Khudoerkov, 2018).

Consistent with the loss of dopaminergic neurons, imaging studies have demonstrated altered nigrostriatal functions in PD (Deumens et al., 2002). For example, individuals with PD, as compared to healthy controls, showed decreases in the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation of blood oxygenation-level dependent signals in the putamen (Wang et al., 2018). Many studies described altered functional connectivity of the putamen in PD (Wang et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2018; Manes et al., 2018), including decreases in connectivity with orbitofrontal gyrus and cerebellum (Wang et al., 2017), and increases in connectivity with the supplementary motor area (Yu et al., 2013) and caudate (Wang et al., 2017). In positron emission tomography imaging, expression of the serotonin transporter (Kish et al., 2008) appeared to decrease, and the size of dopamine transporter/α-synuclein complexes (components of the Lewy bodies) increased in the putamen in PD (Longhena et al., 2018).

Furthermore, in the SNc, the expression levels of calbindin (Blesa and Vila, 2019), gangliosides GM1, GD1a, GD1b, and GT1b, ganglioside biosynthetic genes B3GALT4 and ST3GAL2 (Schneider, 2018), and ghrelin receptors (Suda et al., 2018) were absent or significantly decreased in PD. The expression levels of glycoprotein GPNMB (Moloney et al., 2018), SNc free water (Guttuso et al., 2018), and iron accumulation (Barbosa et al., 2015; An et al., 2018) were significantly elevated; and mitochondrial function was altered (Reeve et al., 2018) in PD. These findings support altered molecular cascades and physiological processes in the nigrostriatal pathways in PD. Finally, many treatments of PD target the putamen and/or SNc, including L-DOPA as the first-line medication. L-DOPA restores dopaminergic signaling and improves motor control including response inhibition by enhancing striatal activation in early-stage Parkinson’s disease (Manza et al., 2018). High-frequency deep brain stimulation of the putamen (Montgomery et al., 2011), low-frequency deep brain stimulation of the SN pars reticulata (Valldeoriola, 2019; Weiss et al., 2019), and crocin (Haeri et al., 2019) for treatment-refractory patients have also demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of PD. On the basis of these findings, we focused on the putamen and SNc in the current study.

The nigrostriatal pathway may be genetically controlled. A genetic marker at 3′-UTR of kinectin 1 gene (KTN1), i.e., rs945270, demonstrated the genome-wide strongest (p = 1.1 × 10–33), replicable, and specific effects on the putamen gray matter volume (GMV) in subjects without neurodegenerative or neuropsychiatric disorders (Hibar et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2017). The other three markers at KTN1, i.e., rs2181743 (5′-UTR), rs8017172 (3′-UTR), and rs17253792 (3′-UTR), significantly increased the putamen GMVs too [p = 4.0 × 10–8 (6.7 × 10–34 to 3.0 × 10–14) and 3.2 × 10–7, respectively] (Chen et al., 2017; Satizabal et al., 2019). Among them, rs8017172 has been reported to significantly cis-regulate the methylation of CpG islands in the putamen (p = 4.4 × 10–6) (Satizabal et al., 2019). Except for these four variants reported to regulate the putamen GMVs, no other KTN1 variants have been reported to influence the putamen and SNc GMVs. Importantly, these four variants are located in the same haplotype block. These findings together suggest a relationship among KTN1 variants, KTN1 expression in putamen, and putamen GMV.

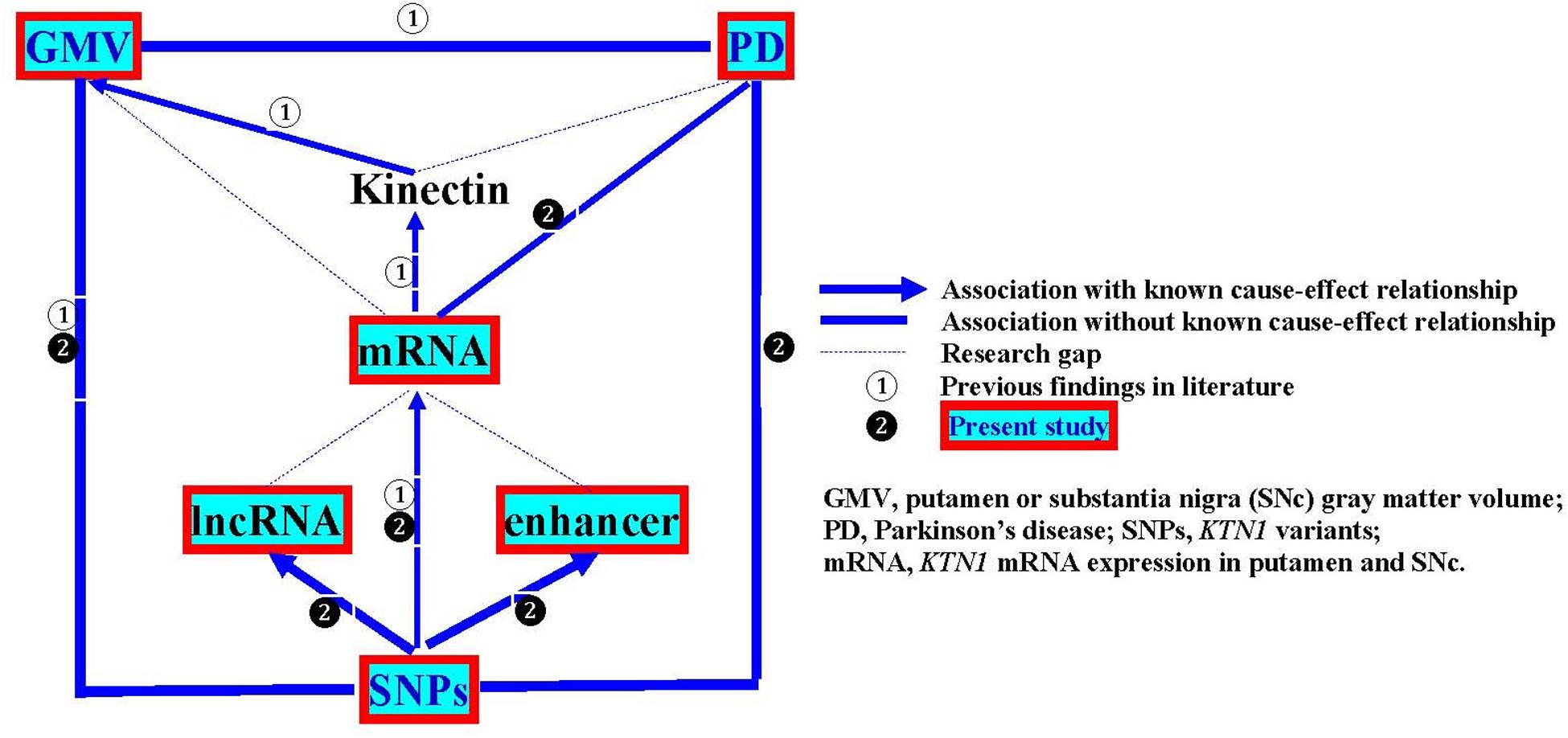

In the present study, we aimed to examine the KTN1 variants as a genetic risk factor for PD, the roles of the KTN1 variants in regulating mRNA expression in the putamen and SNc and putamen GMV, and whether KTN1 mRNA may be differentially expressed in the putamen and SNc between PD and controls. The overall design of this study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

We examined three independent population-based Caucasian samples: “PD_ENV” (dbGaP access number: phs000196.v3.p1), “phg000022” (phs000126.v2.p1), and “lng_coriell_pd” (phs001172.v1.p2). The first sample served as the discovery sample and the other two served as the replication samples. The discovery sample included 2,000 subjects with PD (1,346 males and 654 females) and 1,986 healthy subjects (769 males and 1,217 females). The first replication sample, i.e., “phg000022,” included 900 subjects with PD (537 males and 363 females) and 867 healthy subjects (363 males and 521 females). The second replication sample, i.e., “lng_coriell_pd,” included 940 subjects with PD (560 males and 380 females) and 801 healthy subjects (336 males and 465 females).

All cases met the UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank clinical diagnostic criteria for PD (Gibb and Lees, 1988), and were excluded if their initial PD diagnosis changed during the ∼12 years of follow-up, or they had other neurologic or neurodegenerative conditions, or psychotic, mood and substance use disorders. All controls were free from PD and other neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases. Diagnoses of these subjects have been confirmed by physician interviews, questionnaires, hospital medical records, as well as pathology, radiology and neuropsychology reports. All subjects are Caucasians. The demographic data of these three samples have been described in detail before (Nichols et al., 2007; Simon-Sanchez et al., 2009; Hamza et al., 2010). All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Human Investigation Committee of all institutions.

Imputation

The discovery sample was genotyped on Illumina HumanOmni1_Quad_v1-0_B microarray platform. The first replication sample “phg000022” was genotyped on Illumina HumanCNV370v1 microarray platform, and the second replication sample “lng_coriell_pd” was genotyped by Whole Exome Sequencing using Illumina TruSeq system. To make the genetic marker sets consistent across different samples, we imputed the entire KTN1 region (Chr14:54995382-55550419) by the program IMPUTE2 (Howie et al., 2009). The imputed data were stringently “cleaned up” prior to association analysis (Zuo et al., 2012; Luo et al., 2020a).

Gene-Disease Association Analysis

SNP-PD associations were analyzed using logistic regression models as implemented in the program PLINK (Purcell et al., 2007), in which the diagnosis served as dependent variable, alleles as independent variables, and sex and age as covariates. The associations in the discovery sample were analyzed first. A p < 0.05 indicates a nominally significant association. These nominal associations were further explored in the two replication samples. A SNP-PD association with p < 0.05 in both discovery and replication samples was taken as a replicable association.

Bioinformatic Analyses

A series of bioinformatic analyses, including FuncPred (Xu and Taylor, 2009) and VE!P (McLaren et al., 2010) and the UCSC Genome Browser, were conducted to predict the potential biological functions of the risk SNPs, to explore the relationship of the risk SNPs with DNA or RNA transposons, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), transcription factor binding sites (TFBS), and enhancers. Finally, we reviewed the literature for the regulatory effects of these risk SNPs on the GMVs of putamen and SNc.

Associations of PD-Risk Alleles With KTN1 mRNA Expression in Putamen and SNc, and With Putamen GMV

After the risk KTN1 alleles for PD were identified from the afore-described gene-disease association analyses, the potential regulatory effects of the risk alleles on the KTN1 mRNA expression in human postmortem putamen and SNc in a UK European cohort (n = 129) (BRAINEAC dataset) (Ramasamy et al., 2014) and a European-American cohort (n = 170) (GTEx dataset) (Gtex Consortium, 2013) were analyzed using cis-acting expression quantitative trait locus (cis-eQTL) analysis.

The potential regulatory effects of these risk alleles on the putamen GMV were analyzed in two European postmortem putamen samples (n = 13,145 and 37,571, respectively) [Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics through Meta-Analysis (ENIGMA2) consortium – GWAS Meta-Analysis of Subcortical Volumes]1 (Hibar et al., 2015; Satizabal et al., 2019) using multiple linear regression analysis. These subjects were free of neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders. The β- and Z-values, measures of effect sizes, and the p values, a measure of statistical significance, from the regression models were calculated.

KTN1 mRNA Expression in Putamen and SNc

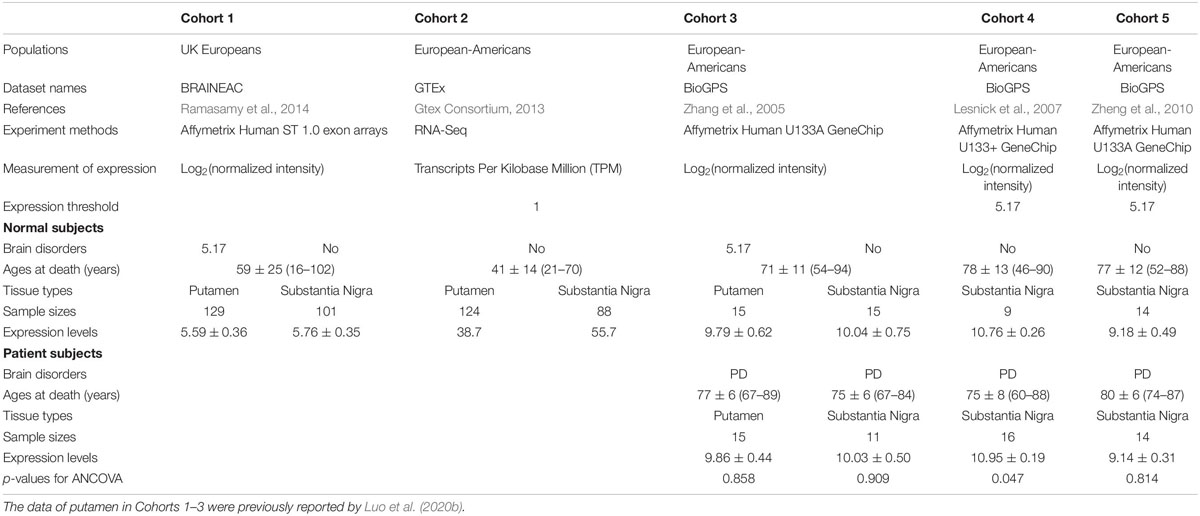

The KTN1 mRNA expression in the putamen and SNc was examined in the postmortem brains of five independent cohorts. Cohorts 1–5 comprised 129 putamen and 101 SNc tissues [UK Brain Expression Consortium (UKBEC)] (Ramasamy et al., 2014), 124 putamen and 88 SNc tissues [The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project (Gtex Consortium, 2013)], 15 putamen and 15 SNc tissues (BioGPS) (Zhang et al., 2005), 9 SNc tissues (BioGPS) (Papapetropoulos et al., 2006; Lesnick et al., 2007), and 14 SNc tissues (BioGPS) (Zheng et al., 2010) extracted from the subjects without neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders, respectively. Cohorts 3–5 also comprised 15 putamen and 11 SNc tissues (BioGPS) (Zhang et al., 2005), 16 SNc tissues (BioGPS) (Papapetropoulos et al., 2006; Lesnick et al., 2007), and 14 SNc tissues (BioGPS) (Zheng et al., 2010) extracted from the subjects with PD, respectively. The subjects were either UK Europeans (Cohort 1) or European-Americans (Cohorts 2–5). mRNA expression in Cohorts 1, 3, 4, and 5 was examined using Affymetrix Human ST 1.0 exon arrays or Affymetrix Human U133A GeneChips (validated by qPCR). The expression levels with normalized intensity >36, i.e., log2(normalized intensity) >5.17, were taken as “expressed.” mRNA expression in Cohort 2 was examined using RNA-Seq (validated by qPCR). The expression levels with RPKM values >1 were taken as “expressed” (Luo et al., 2020b).

As the putamen volume decreases with age (McDonald et al., 1991; Greven et al., 2015; Halkur Shankar et al., 2017), the expression levels of KTN1 mRNA in the putamen and/or SNc in Cohorts 3, 4, and 5 were compared between PD and healthy subjects using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with age as a covariate. A p < 0.05 indicates significantly different expressions.

Results

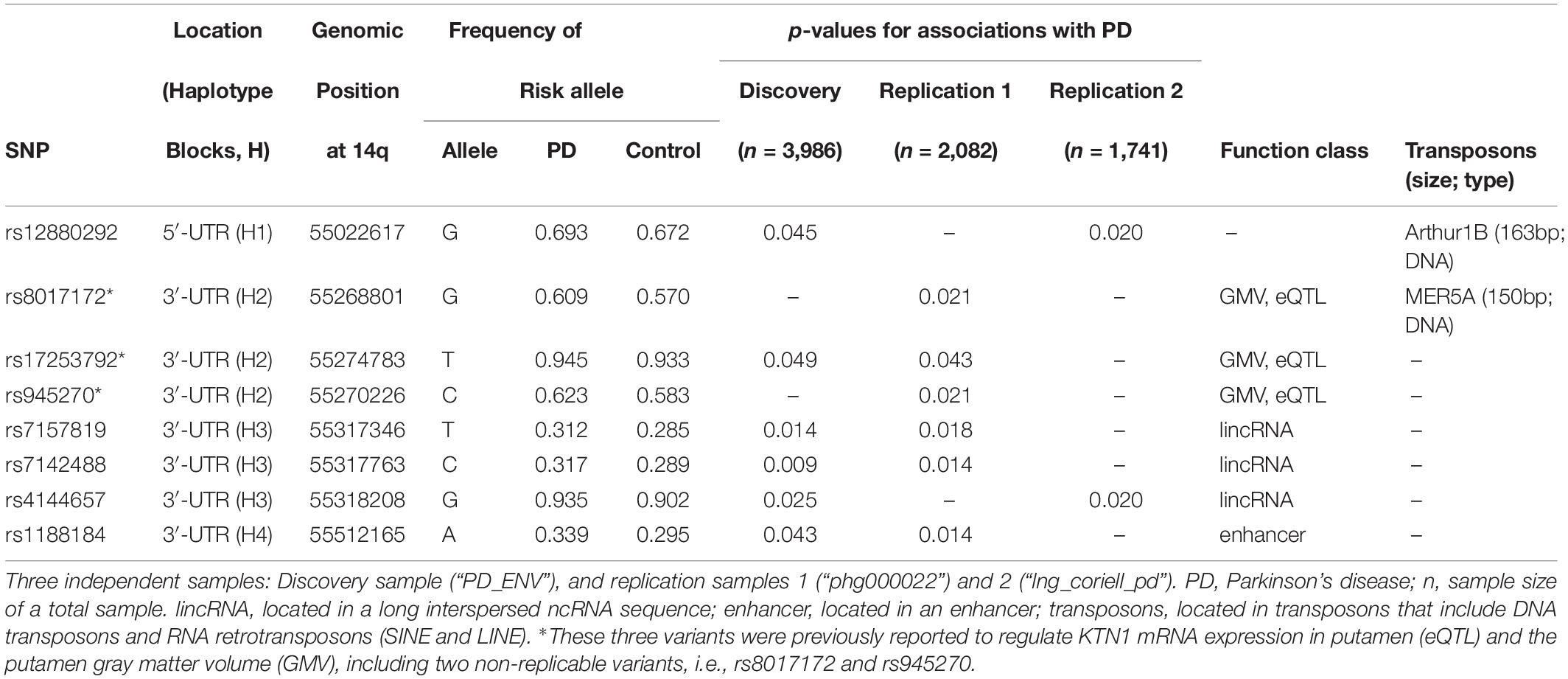

Replicable Associations Between KTN1 SNPs and PD Across Discovery and Replication Samples (Table 1)

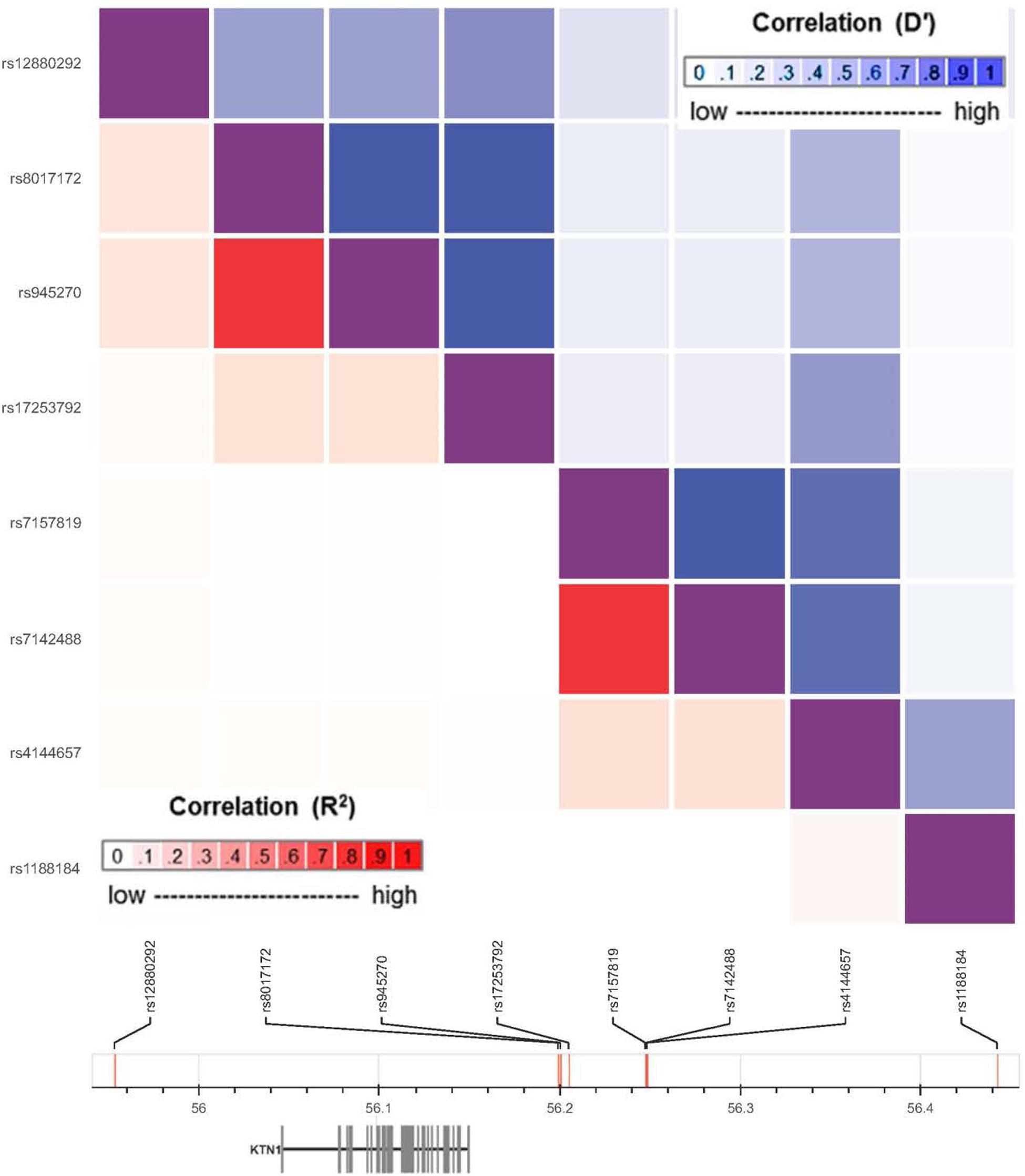

A total of 1847 imputed KTN1 SNPs were analyzed in the discovery sample (“PD_ENV”), including 142 SNPs nominally associated with PD (p < 0.05). Among them, six SNPs significantly associated with PD in the discovery sample were also associated with PD in at least one replication sample (“phg000022” or “lng_coriell_pd”), including four replicable associations between “PD_ENV” and “phg000022” samples (0.009 ≤ p ≤ 0.049) and two replicable associations between “PD_ENV” and “lng_coriell_pd” samples (0.020 ≤ p ≤ 0.045). These six replicable risk SNPs, together with the other two non-replicable GMV-associated variants (i.e., rs8017172 and rs945270) (Hibar et al., 2015; Satizabal et al., 2019), were located in four haplotype blocks (D’ > 0.8; Figure 2), including one in 5′-UTR and the others in 3′-UTR. The major alleles G of rs8017172, T of rs17253792, and C of rs945270 in the H2 block, the three that have been significantly associated with increases in putamen GMVs (p = 2.5 × 10–24, 3.2 × 10–7, and 1.1 × 10–33, respectively) (Hibar et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2017), were positively associated with PD in the discovery sample (p = 0.049 for rs17253792) and/or the replication sample “phg000022” (p = 0.021 for rs8017172, p = 0.043 for rs17253792, and p = 0.021 for rs945270, respectively).

Table 1. Bioinformatics of KTN1 SNPs significantly associated with Parkinson’s disease in three independent European-American samples.

The Risk KTN1 SNPs May Be Biologically Functional (Table 1)

The eight risk variants were located in four haplotype blocks. Bioinformatic analysis showed that the variants within the same haplotype blocks were not only highly linked but also shared similar biological functions. All of the three variants in H3 were located in long intergenic non-coding RNAs (lincRNAs). The variant in H4, i.e., rs1188184, was located in an enhancer. Furthermore, two risk variants were, respectively, located on two transposons, including rs12880292 on the DNA transposon Arthur1B (163 bp), and rs8017172 on the DNA transposon MER5A (150 bp).

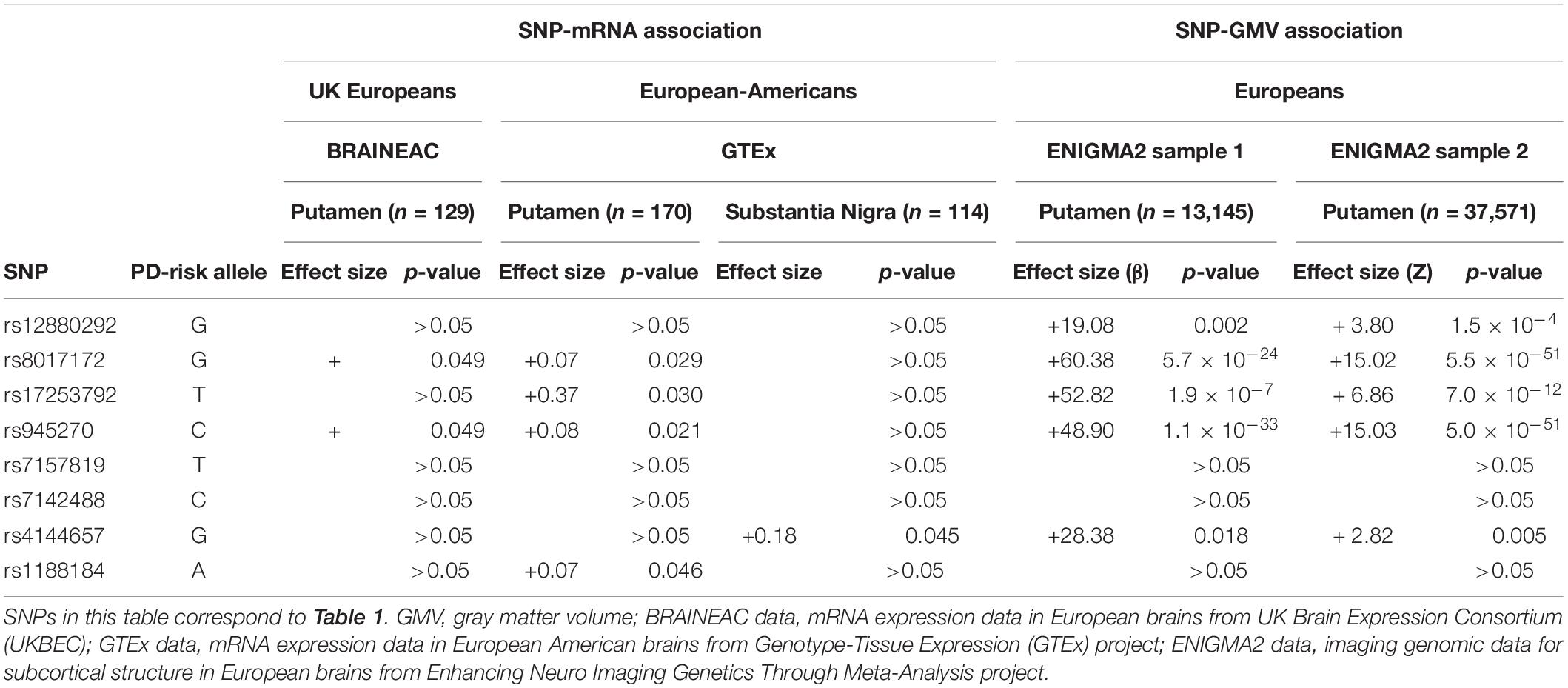

The PD-Risk Alleles Potentially Increased the KTN1 mRNA Expression in Putamen and SNc, and the Putamen GMV (Table 2)

The alleles with significantly higher frequencies in the PD groups than the controls were identified as the risk alleles for PD by the afore-mentioned association analyses. The risk alleles of rs8017172 and rs945270 increased the KTN1 mRNA expression in putamen both in UK Europeans (p = 0.049 for both; BRAINEAC dataset) and European-Americans (p = 0.029 and 0.021, respectively, GTEx dataset). Two risk alleles of rs17253792 and rs1188184 increased mRNA expression in putamen in European-Americans too (p = 0.030 and 0.046, respectively). Additionally, the risk allele of rs4144657 increased mRNA expression in SNc in European-Americans (p = 0.045). Four risk alleles of rs8017172, rs17253792, rs945270 and rs4144657 were all major alleles (f > 0.5), consistent with previous reports (Gtex Consortium, 2013; Ramasamy et al., 2014).

Table 2. Associations between the PD-risk SNPs and both KTN1 mRNA expression in putamen or substantia nigra and GMVs of putamen.

The risk alleles of five SNPs increased the GMVs of putamen in both ENIGMA2 European samples, which included rs12880292 in H1 block (β = 19.08, p = 0.002 in Sample 1; Z = 3.80, p = 1.5 × 10–4 in Sample 2) and rs4144657 in H3 block (β = 28.38, p = 0.018; Z = 2.82, p = 0.005) that modestly increased the putamen GMVs, and rs8017172 (β = 60.38, p = 5.7 × 10–24; Z = 15.02, p = 5.5 × 10–51), rs17253792 (β = 52.82, p = 1.9 × 10–7; Z = 6.86, p = 7.0 × 10–12) and rs945270 (β = 48.90, p = 1.1 × 10–33; Z = 15.03, p = 5.0 × 10–51) in H2 block that highly significantly increased the putamen GMVs. All of these five risk alleles were major alleles (f > 0.5). These SNP-GMV associations were consistent with previous reports (Hibar et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2017; Satizabal et al., 2019).

The KTN1 mRNA Was Significantly Expressed in the Putamen and/or SNc Across Five Independent Cohorts and Differentially Expressed in the SNc Between PD and Healthy Controls in One Cohort (Table 3)

In three independent cohorts, Cohorts 1, 2, and 3, the KTN1 mRNA was abundantly expressed in the putamen. The expression levels in control subjects were 5.59 ± 0.36 [log2(normalized intensity)], 38.70 [Transcripts Per Kilobase Million (TPM)] and 9.79 ± 0.62 [log2(normalized intensity)], respectively. KTN1 mRNA was also abundantly expressed in PD subjects in Cohort 3 (expression level = 9.86 ± 0.44), at a level higher than control subjects, although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.858).

Table 3. The KTN1 mRNA expression in putamen or substantia nigra with/without Parkinson’s disease (PD) in five independent cohorts.

Across the five independent cohorts, the KTN1 mRNA was abundantly expressed in the SNc too. The expression levels in control subjects were 5.76 ± 0.35 [log2(normalized intensity)], 55.70 [TPM], 10.04 ± 0.75 [log2(normalized intensity)], 10.76 ± 0.26 [log2(normalized intensity)], and 9.18 ± 0.49 [log2(normalized intensity)], for Cohorts 1–5, respectively. Furthermore, the expression levels in PD subjects in Cohorts 3, 4, and 5 were 10.03 ± 0.50, 10.95 ± 0.19, and 9.14 ± 0.31 [log2(normalized intensity)], respectively. The expression levels were significantly higher in PD than in control subjects in Cohort 4 (p = 0.047) but were not different for Cohorts 3 and 5 (p’s > 0.05).

Discussion

We found six KTN1 variants that were associated with PD across at least two independent samples, and two other GMV-associated variants that were associated with PD in one sample. Six of these risk variants may be biologically functional, regulating either the mRNA expression in putamen or SNc or the GMVs of putamen. KTN1 mRNAs were expressed in the putamen and/or SNc across five independent cohorts, and were differentially expressed in the SNc between PD and controls in one cohort. Together, these results suggest that KTN1 plays a functional role in the development of PD, supporting previous findings of associations between KTN1 variants and PD (van Dijk et al., 2012; Nalls et al., 2014; Chang et al., 2017).

Two risk variants located in DNA transposons may control the transcription of KTN1, playing a decisive mutagenic role in degenerative pathologies (O’Donnell and Burns, 2010; Li et al., 2013; Sturm et al., 2017), most obviously in the brain (De Cecco et al., 2013; Van Meter et al., 2014). Three risk variants in H3 located in a lincRNA may regulate KTN1 mRNA expression. One variant located in an enhancer may affect the transcription too. The potential biological functions of PD-risk SNPs, along with the abundant KTN1 mRNA expression in the putamen and SNc, and the differential KTN1 mRNA expression in the SNc between PD and controls, again suggest a functional role of KTN1 in the development of PD.

PD is a complex disease that is affected by both genetic and environmental factors. For such a disease, both minor and major alleles of associated gene variants may represent the risk alleles (Kido et al., 2018). This may be explained by genetic drift, through which a slightly deleterious allele may have expanded in frequency and become a major allele (Ohta, 1987). Alternatively, a neutral or advantageous allele that was previously common may become a risk allele for PD owing to changes in the environment (Kido et al., 2018). In addition, overdominance, frequency-dependent selection, and gene–gene or gene–environment interactions may drive a major allele to become a risk allele for PD (Klitz et al., 1986). As observed in the current study, the major alleles G of rs8017172, T of rs17253792, and C of rs945270 in the H2 block, the three among the only four known GMV-associated alleles at KTN1 (Hibar et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2017), significantly increased risk for PD, KTN1 mRNA expression levels in the putamen, and the putamen GMVs. Further, we found increases, albeit not significant, in KTN1 mRNA expression levels in the putamen in PD as compared to controls in one cohort. Together with the literature, these findings overall suggest a consistent, replicable, robust and positive relationship among the KTN1 variants, KTN1 expression in the putamen, putamen GMVs, and PD risk. The findings support the hypothesis that some risk KTN1 alleles may increase kinectin 1 expression in the putamen, altering putamen GMVs and cognitive motor functions supported by the putamen, and lead to the clinical manifestations of PD.

It is well recognized that the dopaminergic neurons in the SNc are lost and the dopamine in the putamen is depleted in PD patients, which leads to a significant decrease in putamen (Schulz et al., 1999; Ghaemi et al., 2002; Krabbe et al., 2005; Pitcher et al., 2012; Sako et al., 2014) and SNc (Krabbe et al., 2005; Ogisu et al., 2013; Hikishima et al., 2015) volumes. As a compensatory response to loss of dopaminergic neurons and dopamine depletion (Hulshoff Pol et al., 2000; Krabbe et al., 2005), the remaining gray matter in the nigrostriatal pathway may compensate to maintain neural transmission by driving the expression of GMV-controlling proteins. One potential molecular mechanism involves the kinectin 1, as would be evidenced by higher levels of KTN1 mRNA expression in the putamen and SNc in PD patients. KTN1 has been reported to play a critical regulatory role in determining putamen GMV (Hibar et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2020b) (but not in SNc GMV yet). Kinectin 1 facilitates vesicle binding to kinesin, regulating crucial developmental processes including axonal guidance, vesicular transport of molecules, and apoptosis (Kumar et al., 1995; Hibar et al., 2015; Luo et al., 2020b), as well as neuronal cell shape and neuronal migration through kinectin–kinesin interactions (Zhang et al., 2010). Neurons with more kinectin 1 have larger cell bodies (Toyoshima and Sheetz, 1996; Zhang et al., 2010; Luo et al., 2020b), and thus may increase the putamen and SNc GMVs in subjects without brain disorders. Notably, the compensatory mechanism did not appear to restore the GMVs in subjects with PD, who have suffered loss of dopaminergic neurons in the SNc and dopamine depletion in the putamen. Alternatively, the increase of KTN1 mRNA expression in the putamen and SNc in PD patients may reflect the consequences of long-term treatments with L-DOPA, or processes in relation to elevated α-synuclein, glycoprotein GPNMB, SN free water, iron accumulation, as has been observed in PD (Barbosa et al., 2015; An et al., 2018; Guttuso et al., 2018; Longhena et al., 2018; Moloney et al., 2018). This important issue warrants further investigation.

KTN1 variants have also been associated with several other neuropsychiatric or neurodegenerative diseases/phenotypes before, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Xu et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2020b), substance use disorder (SUD) (Li et al., 2016; Stringer et al., 2016; Luo et al., 2020a), and cognitive dysfunction in the elderly (Han et al., 2017). We noticed that slightly different sets of SNPs were associated with different disorders/phenotypes, which reflected the difference among them in genetic basis. However, we also noticed that some risk SNPs were shared between them, which reflected the commonness among them in some underlying mechanisms. In particular, the three functional SNPs (rs8017172, rs17253792, and rs945270) that most significantly regulated the putamen GMVs and KTN1 mRNA expression in putamen were shared by PD and SUD, which were associated with reduced and enlarged putamen GMV, respectively. Substance may stimulate the dopamine release from enlarged putamen supported by elevated kinectin expression; however, in PD patients, reduced dopaminergic neurotransmission in the shrunk putamen may also drive kinectin expression via a compensatory mechanism, as discussed above and for ADHD (Luo et al., 2020b). This was why both PD and SUD were associated with GMV-associated alleles and elevated KTN1 mRNA expression.

A major limitation of the present study is that the primary analyses focused on the cross-sectional or retrospective associations among KTN1 SNPs, KTN1 mRNA expression in the putamen and SNc, GMVs of putamen and PD. The findings revealed a statistical but not causal relationship. Future research to reveal the cause-effect relationships would require a prospective, functional study with an appropriate intervention, to answer whether KTN1 variants regulate the development of putamen GMVs and PD, and whether the putamen GMV alteration results in or from the development of PD. The second limitation is that these associations were not analyzed in the same samples. For example, the SNP-mRNA and SNP-GMV associations were separately analyzed only in the samples without PD; and the SNP-PD association was analyzed only in the samples without GMV data; and therefore, we were unable to know the interactive impacts of SNPs, mRNA expression, putamen GMV and PD on one another from these separate samples. Future research to know their interactive impacts would require studying them in the same sample. Finally, some associations among lncRNAs, enhancers, KTN1 mRNA, kinectin, and PD have never been studied, forming the research gaps as shown in Figure 1. Filling these gaps would be one of the future research directions.

In summary, the robust associations between KTN1 variants and PD, the replicable associations between KTN1 variants and putamen GMVs, the potential regulatory effects of KTN1 variants on the mRNA expression in putamen and SNc and the activities of lncRNA and enhancer, the abundant KTN1 mRNA expression in putamen and SNc, the differential mRNA expression in SNc between PD patients and controls, and the reported associations between putamen GMVs and PD, suggested that KTN1 variants may underlie the putamen GMV and risk for PD.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the dbGaP: Accession phs000196.v3.p1, phs000126.v2.p1, and phs001172.v1.p2.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Human Investigation Committee of Yale University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

XGL provided the resources (patients and data). QM, LF, XW, YZ, Y-CW, JJ, JX, HZ, CZ, KW, C-SL, and XGL conducted the study and performed the analysis. C-SL and XGL were responsible for the overall content as guarantors. All authors contributed to the formulation of overarching research goals and aims and the writing, reviewing, and editing of the article.

Funding

This work was supported in part by NIH grants R21AA021380, R21AA020319, and R21AA023237 to XGL, and R01DA023248 to C-SL. We thank NIH GWAS Data Repository, the Contributing Investigator(s) who contributed the phenotype and genotype data from his/her original study (e.g., Drs. Payami, Foroud, Singleton, Hardy, Gasser, Hamza, Factor, Nutt, Zabetian, Molho, Higgins, and Nichols, etc.), and the primary funding organization that supported the contributing study. Funding and other supports for phenotype and genotype data were provided through the NIH Grants R01NS36960 to Haydeh Payami, R01NS037167 to Tatiana Foroud, and R01NS036711 to Myers. The dbGaP datasets used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=gap. dbGaP Study Accession phs000196.v3.p1, phs000126.v2.p1, and phs001172.v1.p2. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project was supported by the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health, and by NCI, NHGRI, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, and NINDS. The GTEx data used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained from the GTEx Portal and dbGaP accession number phs000424.v2.p1.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

References

An, H., Zeng, X., Niu, T., Li, G., Yang, J., Zheng, L., et al. (2018). Quantifying iron deposition within the substantia nigra of Parkinson’s disease by quantitative susceptibility mapping. J. Neurol. Sci. 386, 46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2018.01.008

Barbosa, J. H., Santos, A. C., Tumas, V., Liu, M., Zheng, W., Haacke, E. M., et al. (2015). Quantifying brain iron deposition in patients with Parkinson’s disease using quantitative susceptibility mapping, R2 and R2. Magn. Reson. Imaging 33, 559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2015.02.021

Blesa, J., and Vila, M. (2019). Parkinson disease, substantia nigra vulnerability, and calbindin expression: enlightening the darkness? Mov. Disord. 34, 161–163. doi: 10.1002/mds.27618

Chang, D., Nalls, M. A., Hallgrimsdottir, I. B., Hunkapiller, J., Van Der Brug, M., Cai, F., et al. (2017). A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies 17 new Parkinson’s disease risk loci. Nat. Genet. 49, 1511–1516.

Chen, C. H., Wang, Y., Lo, M. T., Schork, A., Fan, C. C., Holland, D., et al. (2017). Leveraging genome characteristics to improve gene discovery for putamen subcortical brain structure. Sci. Rep. 7:15736.

De Cecco, M., Criscione, S. W., Peckham, E. J., Hillenmeyer, S., Hamm, E. A., Manivannan, J., et al. (2013). Genomes of replicatively senescent cells undergo global epigenetic changes leading to gene silencing and activation of transposable elements. Aging Cell 12, 247–256. doi: 10.1111/acel.12047

Deumens, R., Blokland, A., and Prickaerts, J. (2002). Modeling Parkinson’s disease in rats: an evaluation of 6-OHDA lesions of the nigrostriatal pathway. Exp. Neurol. 175, 303–317. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7891

Ghaemi, M., Hilker, R., Rudolf, J., Sobesky, J., and Heiss, W. D. (2002). Differentiating multiple system atrophy from Parkinson’s disease: contribution of striatal and midbrain MRI volumetry and multi-tracer PET imaging. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 73, 517–523. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.5.517

Gibb, W. R., and Lees, A. J. (1988). The relevance of the Lewy body to the pathogenesis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 51, 745–752. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.6.745

Greven, C. U., Bralten, J., Mennes, M., O’dwyer, L., Van Hulzen, K. J., Rommelse, N., et al. (2015). Developmentally stable whole-brain volume reductions and developmentally sensitive caudate and putamen volume alterations in those with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and their unaffected siblings. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 490–499.

Guttuso, T. Jr., Bergsland, N., Hagemeier, J., Lichter, D. G., Pasternak, O., and Zivadinov, R. (2018). Substantia nigra free water increases longitudinally in Parkinson disease. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 39, 479–484. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.a5545

Haeri, P., Mohammadipour, A., Heidari, Z., and Ebrahimzadeh-Bideskan, A. (2019). Neuroprotective effect of crocin on substantia nigra in MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease model of mice. Anat. Sci. Int. 94, 119–127. doi: 10.1007/s12565-018-0457-7

Halkur Shankar, S., Ballal, S., and Shubha, R. (2017). Study of normal volumetric variation in the putamen with age and sex using magnetic resonance imaging. Clin. Anat. 30, 461–466. doi: 10.1002/ca.22869

Hamza, T. H., Zabetian, C. P., Tenesa, A., Laederach, A., Montimurro, J., Yearout, D., et al. (2010). Common genetic variation in the HLA region is associated with late-onset sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Genet. 42, 781–785. doi: 10.1038/ng.642

Han, L., Jia, Z., Cao, C., Liu, Z., Liu, F., Wang, L., et al. (2017). Potential contribution of the neurodegenerative disorders risk loci to cognitive performance in an elderly male gout population. Medicine 96:e8195. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000008195

Hibar, D. P., Stein, J. L., Renteria, M. E., Arias-Vasquez, A., Desrivieres, S., Jahanshad, N., et al. (2015). Common genetic variants influence human subcortical brain structures. Nature 520, 224–229.

Hikishima, K., Ando, K., Komaki, Y., Kawai, K., Yano, R., Inoue, T., et al. (2015). Voxel-based morphometry of the marmoset brain: in vivo detection of volume loss in the substantia nigra of the MPTP-treated Parkinson’s disease model. Neuroscience 300, 585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.041

Howie, B. N., Donnelly, P., and Marchini, J. (2009). A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529

Hulshoff Pol, H. E., Van Der Flier, W. M., Schnack, H. G., Tulleken, C. A., Ramos, L. M., Van Ree, J. M., et al. (2000). Frontal lobe damage and thalamic volume changes. Neuroreport 11, 3039–3041. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200009110-00042

Kido, T., Sikora-Wohlfeld, W., Kawashima, M., Kikuchi, S., Kamatani, N., Patwardhan, A., et al. (2018). Are minor alleles more likely to be risk alleles? BMC Med. Genomics 11:3. doi: 10.1186/s12920-018-0322-5

Kish, S. J., Tong, J., Hornykiewicz, O., Rajput, A., Chang, L. J., Guttman, M., et al. (2008). Preferential loss of serotonin markers in caudate versus putamen in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 131, 120–131.

Klitz, W., Thomson, G., and Baur, M. P. (1986). Contrasting evolutionary histories among tightly linked HLA loci. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 39, 340–349.

Krabbe, K., Karlsborg, M., Hansen, A., Werdelin, L., Mehlsen, J., Larsson, H. B., et al. (2005). Increased intracranial volume in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 239, 45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.07.013

Kumar, J., Yu, H., and Sheetz, M. P. (1995). Kinectin, an essential anchor for kinesin-driven vesicle motility. Science 267, 1834–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.7892610

Lesnick, T. G., Papapetropoulos, S., Mash, D. C., Ffrench-Mullen, J., Shehadeh, L., De Andrade, M., et al. (2007). A genomic pathway approach to a complex disease: axon guidance and Parkinson disease. PLoS Genet 3:e98. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030098

Li, W., Prazak, L., Chatterjee, N., Gruninger, S., Krug, L., Theodorou, D., et al. (2013). Activation of transposable elements during aging and neuronal decline in Drosophila. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 529–531. doi: 10.1038/nn.3368

Li, Y., Qiao, X., Yin, F., Guo, H., Huang, X., Lai, J., et al. (2016). A population-based study of four genes associated with heroin addiction in han chinese. PLoS One 11:e0163668. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163668

Liu, A., Lin, S. J., Mi, T., Chen, X., Chan, P., Wang, Z. J., et al. (2018). Decreased subregional specificity of the putamen in Parkinson’s Disease revealed by dynamic connectivity-derived parcellation. Neuroimage Clin. 20, 1163–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.10.022

Longhena, F., Faustini, G., Missale, C., Pizzi, M., and Bellucci, A. (2018). Dopamine transporter/alpha-synuclein complexes are altered in the post mortem caudate putamen of Parkinson’s disease: an in situ proximity ligation assay study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:E1611.

Luo, X., Guo, X., Luo, X., Tan, Y., Zhang, P., Yang, K., et al. (2020a). Significant, replicable, and functional associations between KTN1 variants and alcohol and drug codependence. Addict. Biol. e12888. doi: 10.1111/adb.12888

Luo, X., Guo, X., Tan, Y., Zhang, Y., Garcia-Milian, R., Wang, Z., et al. (2020b). KTN1 variants and risk for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 183, 234–244.

Manes, J. L., Tjaden, K., Parrish, T., Simuni, T., Roberts, A., Greenlee, J. D., et al. (2018). Altered resting-state functional connectivity of the putamen and internal globus pallidus is related to speech impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav. 8:e01073. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1073

Manza, P., Schwartz, G., Masson, M., Kann, S., Volkow, N. D., Li, C. R., et al. (2018). Levodopa improves response inhibition and enhances striatal activation in early-stage Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 66, 12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.02.003

McDonald, W. M., Husain, M., Doraiswamy, P. M., Figiel, G., Boyko, O., and Krishnan, K. R. (1991). A magnetic resonance image study of age-related changes in human putamen nuclei. Neuroreport 2, 57–60. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199101000-00014

McLaren, W., Pritchard, B., Rios, D., Chen, Y., Flicek, P., and Cunningham, F. (2010). Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP effect predictor. Bioinformatics 26, 2069–2070. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq330

Moloney, E. B., Moskites, A., Ferrari, E. J., Isacson, O., and Hallett, P. J. (2018). The glycoprotein GPNMB is selectively elevated in the substantia nigra of Parkinson’s disease patients and increases after lysosomal stress. Neurobiol. Dis. 120, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.08.013

Montgomery, E. B. Jr., Huang, H., Walker, H. C., Guthrie, B. L., and Watts, R. L. (2011). High-frequency deep brain stimulation of the putamen improves bradykinesia in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 26, 2232–2238. doi: 10.1002/mds.23842

Nalls, M. A., Pankratz, N., Lill, C. M., Do, C. B., Hernandez, D. G., Saad, M., et al. (2014). Large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies six new risk loci for Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Genet. 46, 989–993.

Nichols, W. C., Elsaesser, V. E., Pankratz, N., Pauciulo, M. W., Marek, D. K., Halter, C. A., et al. (2007). LRRK2 mutation analysis in Parkinson disease families with evidence of linkage to PARK8. Neurology 69, 1737–1744. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000278115.50741.4e

O’Donnell, K. A., and Burns, K. H. (2010). Mobilizing diversity: transposable element insertions in genetic variation and disease. Mob. DNA 1:21. doi: 10.1186/1759-8753-1-21

Ogisu, K., Kudo, K., Sasaki, M., Sakushima, K., Yabe, I., Sasaki, H., et al. (2013). 3D neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging with semi-automated volume measurement of the substantia nigra pars compacta for diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Neuroradiology 55, 719–724. doi: 10.1007/s00234-013-1171-8

Ohta, T. (1987). Very slightly deleterious mutations and the molecular clock. J. Mol. Evol. 26, 1–6. doi: 10.1007/bf02111276

Papapetropoulos, S., Ffrench-Mullen, J., Mccorquodale, D., Qin, Y., Pablo, J., and Mash, D. C. (2006). Multiregional gene expression profiling identifies MRPS6 as a possible candidate gene for Parkinson’s disease. Gene Expr. 13, 205–215. doi: 10.3727/000000006783991827

Pitcher, T. L., Melzer, T. R., Macaskill, M. R., Graham, C. F., Livingston, L., Keenan, R. J., et al. (2012). Reduced striatal volumes in Parkinson’s disease: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Transl. Neurodegener. 1:17.

Purcell, S., Neale, B., Todd-Brown, K., Thomas, L., Ferreira, M. A., Bender, D., et al. (2007). PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795

Ramasamy, A., Trabzuni, D., Guelfi, S., Varghese, V., Smith, C., Walker, R., et al. (2014). Genetic variability in the regulation of gene expression in ten regions of the human brain. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 1418–1428. doi: 10.1038/nn.3801

Reeve, A. K., Grady, J. P., Cosgrave, E. M., Bennison, E., Chen, C., Hepplewhite, P. D., et al. (2018). Mitochondrial dysfunction within the synapses of substantia nigra neurons in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 4:9.

Sako, W., Murakami, N., Izumi, Y., and Kaji, R. (2014). The difference in putamen volume between MSA and PD: evidence from a meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 20, 873–877. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.04.028

Salkov, V. N., and Khudoerkov, R. M. (2018). Neurochemical and morphological changes of microstructures of the compact part of the substantia nigra of human brain in aging and Parkinson’s disease (literature review). Adv. Gerontol. 31, 662–667.

Satizabal, C. L., Adams, H. H. H., Hibar, D. P., White, C. C., Knol, M. J., Stein, J. L., et al. (2019). Genetic architecture of subcortical brain structures in 38,851 individuals. Nat. Genet. 51, 1624–1636.

Schneider, J. S. (2018). Altered expression of genes involved in ganglioside biosynthesis in substantia nigra neurons in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One 13:e0199189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199189

Schulz, J. B., Skalej, M., Wedekind, D., Luft, A. R., Abele, M., Voigt, K., et al. (1999). Magnetic resonance imaging-based volumetry differentiates idiopathic Parkinson’s syndrome from multiple system atrophy and progressive supranuclear palsy. Ann. Neurol. 45, 65–74. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199901)45:1<65::aid-art12>3.0.co;2-1

Simon-Sanchez, J., Schulte, C., Bras, J. M., Sharma, M., Gibbs, J. R., Berg, D., et al. (2009). Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Genet. 41, 1308–1312.

Stringer, S., Minica, C. C., Verweij, K. J., Mbarek, H., Bernard, M., Derringer, J., et al. (2016). Genome-wide association study of lifetime cannabis use based on a large meta-analytic sample of 32 330 subjects from the international cannabis consortium. Transl. Psychiatry 6:e769.

Sturm, A., Perczel, A., Ivics, Z., and Vellai, T. (2017). The Piwi-piRNA pathway: road to immortality. Aging Cell 16, 906–911. doi: 10.1111/acel.12630

Suda, Y., Kuzumaki, N., Sone, T., Narita, M., Tanaka, K., Hamada, Y., et al. (2018). Down-regulation of ghrelin receptors on dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra contributes to Parkinson’s disease-like motor dysfunction. Mol. Brain 11:6.

Tepper, J. M., and Lee, C. R. (2007). GABAergic control of substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons. Prog. Brain Res. 160, 189–208. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(06)60011-3

Toyoshima, I., and Sheetz, M. P. (1996). Kinectin distribution in chicken nervous system. Neurosci. Lett. 211, 171–174. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12752-x

Tritsch, N. X., Ding, J. B., and Sabatini, B. L. (2012). Dopaminergic neurons inhibit striatal output through non-canonical release of GABA. Nature 490, 262–266. doi: 10.1038/nature11466

Valldeoriola, F. (2019). Simultaneous low-frequency deep brain stimulation of the substantia nigra pars reticulata and high-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus to treat levodopa unresponsive freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease: a pilot study. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 63:231. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.12.009

van Dijk, K. D., Berendse, H. W., Drukarch, B., Fratantoni, S. A., Pham, T. V., Piersma, S. R., et al. (2012). The proteome of the locus ceruleus in Parkinson’s disease: relevance to pathogenesis. Brain Pathol. 22, 485–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2011.00540.x

Van Meter, M., Kashyap, M., Rezazadeh, S., Geneva, A. J., Morello, T. D., Seluanov, A., et al. (2014). SIRT6 represses LINE1 retrotransposons by ribosylating KAP1 but this repression fails with stress and age. Nat. Commun. 5:5011.

Wang, J., Zhang, J. R., Zang, Y. F., and Wu, T. (2018). Consistent decreased activity in the putamen in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis and an independent validation of resting-state fMRI. Gigascience 7, giy071. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giy1071

Wang, X., Li, J., Yuan, Y., Wang, M., Ding, J., Zhang, J., et al. (2017). Altered putamen functional connectivity is associated with anxiety disorder in Parkinson’s disease. Oncotarget 8, 81377–81386. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18996

Weiss, D., Milosevic, L., and Gharabaghi, A. (2019). Deep brain stimulation of the substantia nigra for freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease: is it about stimulation frequency? Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 63, 229–230. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.12.010

Xu, B., Jia, T., Macare, C., Banaschewski, T., Bokde, A. L. W., Bromberg, U., et al. (2017). Impact of a common genetic variation associated with putamen volume on neural mechanisms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 56:e434.

Xu, Z., and Taylor, J. A. (2009). SNPinfo: integrating GWAS and candidate gene information into functional SNP selection for genetic association studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W600–W605.

Yu, R., Liu, B., Wang, L., Chen, J., and Liu, X. (2013). Enhanced functional connectivity between putamen and supplementary motor area in Parkinson’s disease patients. PLoS One 8:e59717. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059717

Zhang, X., Tee, Y. H., Heng, J. K., Zhu, Y., Hu, X., Margadant, F., et al. (2010). Kinectin-mediated endoplasmic reticulum dynamics supports focal adhesion growth in the cellular lamella. J. Cell Sci. 123, 3901–3912. doi: 10.1242/jcs.069153

Zhang, Y., James, M., Middleton, F. A., and Davis, R. L. (2005). Transcriptional analysis of multiple brain regions in Parkinson’s disease supports the involvement of specific protein processing, energy metabolism, and signaling pathways, and suggests novel disease mechanisms. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 137B, 5–16. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30195

Zheng, B., Liao, Z., Locascio, J. J., Lesniak, K. A., Roderick, S. S., Watt, M. L., et al. (2010). PGC-1alpha, a potential therapeutic target for early intervention in Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2:52ra73.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, KTN1, putamen, substantia nigra, gray matter volume, mRNA expression

Citation: Mao Q, Wang X, Chen B, Fan L, Wang S, Zhang Y, Lin X, Cao Y, Wu Y-C, Ji J, Xu J, Zheng J, Zhang H, Zheng C, Chen W, Cheng W, Luo X, Wang K, Zuo L, Kang L, Li C-SR and Luo X (2020) KTN1 Variants Underlying Putamen Gray Matter Volumes and Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 14:651. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00651

Received: 03 March 2020; Accepted: 26 May 2020;

Published: 23 June 2020.

Edited by:

Patrizia Longone, Santa Lucia Foundation (IRCCS), ItalyReviewed by:

Omar El Hiba, Université Chouaib Doukkali, MoroccoMarcela M. Morales-Mulia, National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente Muñiz (INPRFM), Mexico

Copyright © 2020 Mao, Wang, Chen, Fan, Wang, Zhang, Lin, Cao, Wu, Ji, Xu, Zheng, Zhang, Zheng, Chen, Cheng, Luo, Wang, Zuo, Kang, Li and Luo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaoping Wang, eF9wX3dhbmdAc2p0dS5lZHUuY24=; Chiang-Shan R. Li, Q2hpYW5nLVNoYW4uTGlAeWFsZS5lZHU=; Xingguang Luo, WGluZ2d1YW5nLkx1b0B5YWxlLmVkdQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Qiao Mao1†

Qiao Mao1† Xiaoping Wang

Xiaoping Wang Yun-Cheng Wu

Yun-Cheng Wu Jiawu Ji

Jiawu Ji Chiang-Shan R. Li

Chiang-Shan R. Li Xingguang Luo

Xingguang Luo