- 1Laboratory of Molecular Immunopharmacology and Drug Discovery, Department of Integrative Physiology and Pathobiology, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA

- 2Departments of Internal Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine and Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA

- 3Psychiatry, Tufts University School of Medicine and Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA

- 4Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA

- 5Second Department of Internal Medicine, Attikon General Hospital, Athens Medical School, Athens, Greece

- 6Department of Child Psychiatry, University of Athens Medical School, Aghia Sophia Children's Hospital, Athens, Greece

Brain “fog” is a constellation of symptoms that include reduced cognition, inability to concentrate and multitask, as well as loss of short and long term memory. Brain “fog” characterizes patients with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs), celiac disease, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, mastocytosis, and postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS), as well as “minimal cognitive impairment,” an early clinical presentation of Alzheimer's disease (AD), and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Brain “fog” may be due to inflammatory molecules, including adipocytokines and histamine released from mast cells (MCs) further stimulating microglia activation, and causing focal brain inflammation. Recent reviews have described the potential use of natural flavonoids for the treatment of neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases. The flavone luteolin has numerous useful actions that include: anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, microglia inhibition, neuroprotection, and memory increase. A liposomal luteolin formulation in olive fruit extract improved attention in children with ASDs and brain “fog” in mastocytosis patients. Methylated luteolin analogs with increased activity and better bioavailability could be developed into effective treatments for neuropsychiatric disorders and brain “fog.”

Introduction

Brain “fog” is a constellation of symptoms that include reduced mental acuity and cognition, inability to concentrate and multitask, as well as loss of short and long-term memory. Brain “fog” characterizes patients with many neuroimmune diseases (Theoharides, 2013a) with celiac disease (Lebwohl and Ludvigsson, 2014; Lichtwark et al., 2014) chronic fatigue syndrome (Ocon, 2013), fibromyalgia and tachycardia postural syndrome (POTS) (Ross et al., 2013), as well as those with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) and “minimal cognitive impairment,” which is now considered the early clinical presentation of Alzheimer's disease (AD) (Drzezga et al., 2011). Moreover, patients on chemotherapy often experience brain “fog” (Raffa, 2011).

Brain “fog” is particularly common in patients with systemic mastocytosis (SM) (Theoharides et al., 2015c) or disorders of mast cell (MC) activation (Valent et al., 2012; Petra et al., 2014). A recent survey of the symptoms experienced by patients with MC disorders reported that >90% of them experienced moderate to severe brain “fog” almost daily (Moura et al., 2012) and cognitive impairment was confirmed using a validated instrument (Moura et al., 2012). Patients with MC disorders also experience other related neurologic (Smith et al., 2011) and psychiatric (Moura et al., 2014) symptoms. It is interesting that children with mastocytosis were reported to have increased risk of developing ASDs compared to the general population (Theoharides, 2009). Children with ASDs are also characterized by brain “fog” (Rossignol and Frye, 2012) and focal brain inflammation (Theoharides et al., 2013) with MC activation being implicated in their pathogenesis (Theoharides et al., 2012a; Theoharides, 2013b).

Even though AD has typically been associated with brain senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles that involve amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau proteins (Heneka et al., 2015), recent evidence indicates that oxidative stress/mitochondrial dysfunction (Zhu et al., 2012) and inflammation (Tan and Seshadri, 2010; Pizza et al., 2011; Heneka et al., 2015), are possibly involved in AD. In fact the immune system and inflammation are increasingly implicated in neuropsychiatric diseases (Kerr et al., 2005; Schmidt et al., 2007; Hamdani et al., 2013; Jones and Thomsen, 2013; Munkholm et al., 2013).

Pathogenesis/Focal Inflammation

Inflammatory molecules, secreted in the brain could contribute to the pathogenesis of such diseases (Theoharides et al., 2004b) possibly including brain “fog.” Brain expression of pro-inflammatory genes was increased in the brains of deceased patients with neuropsychiatric diseases (Theoharides et al., 2011b).

It is still not clear what triggers brain inflammation. Mounting evidence suggests that stress (Theoharides et al., 2011b) and exposure to mold (Crago et al., 2003; Shoemaker and House, 2006; Reinhard et al., 2007; Shenassa et al., 2007; Empting, 2009), especially airborne mycotoxins (Rea et al., 2003; Gordon et al., 2004; Kilburn, 2009; Brewer et al., 2013), may be involved. It is interesting that mold can potentiate histamine release from MCs (Larsen et al., 1996).

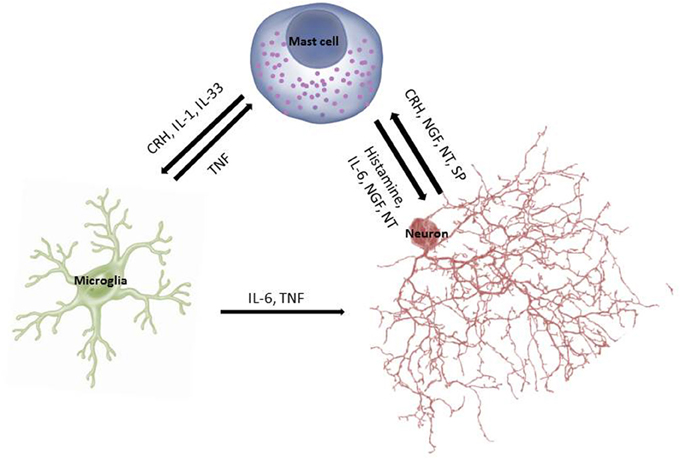

In fact, cross-talk between MCs and microglia is being considered critical in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases (Skaper et al., 2012, 2013) (Figure 1). Microglia activation is a common finding in brains of children with ASDs (Pardo et al., 2005; Sandoval-Cruz et al., 2011; Gupta et al., 2014), as well as in other psychiatric diseases (Beumer et al., 2012). Activation of microglia directly or indirectly by corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) could contribute to the pathogenesis of mental disorders (Kritas et al., 2014b).

Obesity

Obesity has been associated with neuropsychiatric disorders (Severance et al., 2012; Byrne et al., 2015). Adipocytokines are involved in neuroinflammation (Aguilar-Valles et al., 2015) and possibly in dementia (Arnoldussen et al., 2014; Kiliaan et al., 2014) including AD (Mathew et al., 2011; Khemka et al., 2014).

MCs have been implicated in obesity (Theoharides et al., 2011a), obesity-related asthma (Sismanopoulos et al., 2013) and in cardiovascular disease (CAD) (Alevizos et al., 2013; Chrostowska et al., 2013), which involves local inflammation (Libby et al., 2002; Matusik et al., 2012; Spinas et al., 2014). Both MCs (Kovanen et al., 1995; Laine et al., 1999) and histamine (Sakata et al., 1996) have been reported to be increased in atherosclerotic coronary plaques (Theoharides et al., 2011a). MC-derived histamine is a coronary constrictor. MC-derived IL-6 and TNF are independent risk factors for CAD (Libby et al., 2002) and can be released from MCs under stress (Huang et al., 2003), which can precipitate myocardial infarction (Alevizos et al., 2013). Obesity leads to endothelial dysfunction and chronic inflammation (Iantorno et al., 2014), also associated with the metabolic syndrome (Sun et al., 2015).

Role of Mast Cells

MCs derive from bone marrow progenitors, mature in tissues depending on microenvironmental conditions and are critical for the development of allergic reactions, but also immunity (Galli et al., 2008b; Theoharides et al., 2010a; Sismanopoulos et al., 2012), neuroinflammation (Theoharides and Cochrane, 2004; Theoharides et al., 2010a; Skaper et al., 2012), and mitochondrial health (Theoharides et al., 2011b; Zhang et al., 2011). MCs can produce both pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators rendering capable to exert immuno-modulatory functions (Galli et al., 2008a; Kalesnikoff and Galli, 2008).

MCs are present in the brain where they regulate blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability (Theoharides, 1990) and brain function (Nautiyal et al., 2008). MCs are located adjacent to CRH-positive neurons in the rat median eminence (Theoharides et al., 1995) and regulate the HPA axis (Theoharides et al., 2004a; Theoharides and Konstantinidou, 2007).

In addition to IgE and antigen (Blank and Rivera, 2004), MCs are activated by substance P (SP) (Zhang et al., 2011), neurotensin (NT) (Donelan et al., 2006), and nerve growth factor (NGF) (Kritas et al., 2014a). In fact, allergic MC stimulation leads to secretion of Hemokin 1, which acts in an autocrine manner through MC NK1 receptors to augment IgE-mediated allergic responses (Sumpter et al., 2015). MC stimulation by SP is augmented by IL-33 (Theoharides et al., 2010b), which has been considered an “alarmin” acting through MCs to alert the innate immune system (Moussion et al., 2008; Enoksson et al., 2011). IL-33 has been linked to autoimmune and inflammatory diseases (Theoharides et al., 2015c), especially brain inflammation (Chakraborty et al., 2010) and recently AD pathogenesis (Xiong et al., 2014). Antigen can also act synergistically with toll-like receptors (TLR-2 and TLR-4) to produce MC cytokines (Qiao et al., 2006) and regulate responses to pathogens (Abraham and St John, 2010; Theoharides, 2015).

Once activated, MCs secrete numerous vasoactive, neurosensitizing and pro-inflammatory mediators (Theoharides et al., 2015a). These include preformed histamine, serotonin, kinins, proteases and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), as well as newly synthesized, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, chemokines (CCXL8, CCL2), cytokines (IL-4, IL-6, IL-1, TNF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which increase BBB permeability (Theoharides et al., 2008). MCs store pre-formed TNF in secretory granules from which it is released rapidly (Zhang et al., 2012b) and stimulates activated T cells (Nakae et al., 2006; Kempuraj et al., 2008).

MCs can release some mediators, such as IL-6, selectively without degranulation (Theoharides et al., 2007). In addition, CRH can stimulate selective release of VEGF (Cao et al., 2005) and IL-1 can stimulate selective release of IL-6 (Kandere-Grzybowska et al., 2003), which could affect brain function (Theoharides et al., 2004a) and activate the HPA axis (Kalogeromitros et al., 2007). MC-derived IL-6 along with TGFβ stimulate development of Th-17 cells (Nakae et al., 2007) and MCs, themselves secrete IL-17 (Nakae et al., 2007), which is involved in autoimmunity. Levels of IL-6 were increased in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Li et al., 2009b) and plasma (Yang et al., 2015) of patients with ASDs. MCs can therefore participate in neuroinflammation (Theoharides and Cochrane, 2004; Zhang et al., 2012a; Dong et al., 2014), especially autism (Theoharides et al., 2012a, 2015b; Theoharides, 2013b).

Maternal administration of the viral substitute poly (I:C) produced autism-like behavior in mice that was dependent on IL-6 (Hsiao et al., 2012) and was absent in IL-6 knock-out mice (Smith et al., 2007). We had shown that acute immobilization stress significantly increased serum IL-6 and this was absent in MC deficient mice (Huang et al., 2003). It was recently reported that plasma IL-6 was significantly increased after social stress, especially in mice that developed a phenotype susceptible to stress, while IL-6−∕− mice were resilient to social stress (Hodes et al., 2014).

MCs can secrete the content of individual granules (Theoharides and Douglas, 1978), and biogenic amines such as serotonin selectively without degranulation (Theoharides et al., 1982). MCs can communicate with neurons by transgranulation (Wilhelm et al., 2005). It was recently shown that MCs can undergo “polarized” exocytosis of proteolytic enzymes is what has been termed “antibody-dependent degranulation synapse” (Joulia et al., 2015). MCs can also secrete phospholipid nanovesicles (exosomes) (Skokos et al., 2002) that could cary a number of biologically active molecules (Shefler et al., 2011), in a manner guided by surface antigens (Bryniarski et al., 2013). Such exosomes could participate in neuropsychiatric diseases (Tsilioni et al., 2014; Kawikova and Askenase, 2015). In fact, individual MCs have been shown to exhibit “circadian clock” reactivity (Molyva et al., 2014; Nakao et al., 2015).

Histamine

MCs are located perivascularly in close proximity to brain neurons especially in the leptomeninges (Rozniecki et al., 1999a) and hypothalamus (Pang et al., 1996) where they contain most of the brain histamine (Alstadhaug, 2014). Increasing evidence indicates that brain histamine is involved in the pathogenesis of neuropsychiatric diseases (Haas et al., 2008; Shan et al., 2015) and the disruption of the BBB (Banuelos-Cabrera et al., 2014), through MC activation (Esposito et al., 2001, 2002; McKittrick et al., 2015). Histamine may be important for alertness and motivation (Zlomuzica et al., 2008; Torrealba et al., 2012), as well as cognition, learning and memory (Kamei and Tasaka, 1993; Alvarez et al., 2001; Rizk et al., 2004; da Silveira et al., 2013). For instancee, there was enhanced spatial learning and memory in histamine 3 (H3) receptor mice−∕− (Rizk et al., 2004). Moreover, antagonism of the autoinhibitory H3 receptor improved memory retention (Orsetti et al., 2001). In fact, H3 antagonists are being considered for the treatment of cognitive disorders and AD (Brioni et al., 2011).

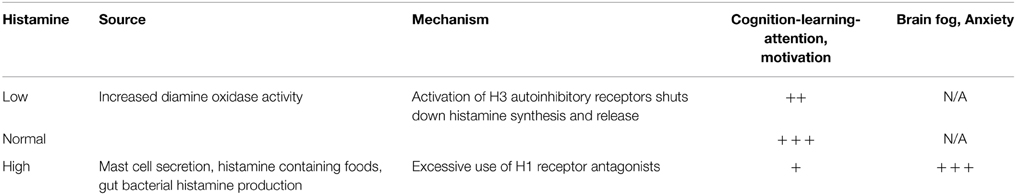

It appears that some histamine is necessary for alertness, learning and motivation, but too much histamine shuts the system down, in MCs and histaminergic neurons, by activating H3 autoinhibitory receptors leading to brain “fog” (Table 1).

Brain histamine can be increased by triggers of brain MCs, by histamine-containing foods (Bodmer et al., 1999; Maintz and Novak, 2007; Schwelberger, 2010; Prester, 2011), histamine produced by bacteria (Landete et al., 2008), or overuse of H1 receptor antagonists that would shift histamine binding from H1 to H3 receptors leading to autoinhibition of histamine synthesis and release (Table 1). In fact, we had shown that in rats at least only brain MCs express functional H3 receptors (Rozniecki et al., 1999b), as evidenced by the fact that an H3 receptor agonist inhibited while at H3 receptor antagonist augmented histamine and serotonin release only from brain, but not peritoneal MCs.

Beneficial Effect of Luteolin

Recent reviews have discussed the potential use of flavonoids for the treatment of neuropsychiatric (Jager and Saaby, 2011; Grosso et al., 2013) and neurodegenerative (Jones et al., 2012; Solanki et al., 2015) diseases including AD (Sheikh et al., 2012; Baptista et al., 2014; Mecocci et al., 2014; Vauzour, 2014).

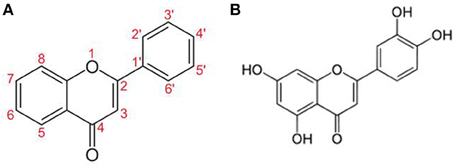

Flavonoids (Figure 2) are naturally occurring compounds mostly found in green plants and seeds (Middleton et al., 2000). Unfortunately, our modern life diet contains progressively fewer flavonoids and under these conditions, the average person cannot consume enough to make a positive impact on health. Moreover, less than 10% of orally ingested flavonoids are absorbed (Passamonti et al., 2009; Thilakarathna and Rupasinghe, 2013) and are extensively metabolized to inactive ingredients in the liver (Chen et al., 2014).

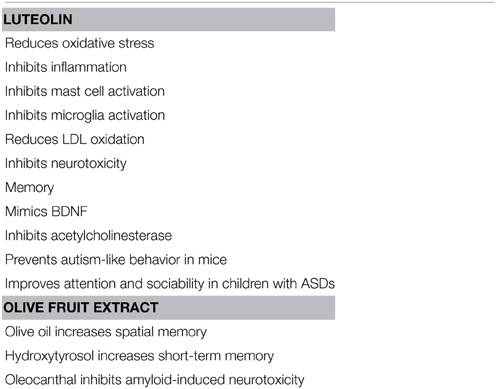

Luteolin (5,7-3′5′-tetrahydroxyflavone) has potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory (Middleton et al., 2000) and MC inhibitory activities (Kimata et al., 2000; Kempuraj et al., 2005; Asadi et al., 2010) and also inhibits auto-immune T cell activation (Verbeek et al., 2004; Kempuraj et al., 2008) (Table 2). Luteolin also inhibits microglial IL-6 release (Jang et al., 2008), microglial activation and proliferation (Chen et al., 2008; Dirscherl et al., 2010; Kao et al., 2011), as well as microglia-induced neuron apoptosis (Zhu et al., 2011).

A methylated luteolin analog (6-Methoxyluteolin) was shown to inhibit IgE-stimulated histamine release from human basophilic KU812F (Shim et al., 2012). Moreover, we recently showed that tetramethoxyluteolin is more potent inhibitor of human cultured MCs than luteolin (Weng et al., 2014).

Luteolin is protective against methylmercury-induced mitochondrial damage (Franco et al., 2010), as well as mercury and mitochondrial DNA-triggering of MCs (Asadi et al., 2010).

Luteolin improved spatial memory in a scopolamine-induced model (Yoo et al., 2013) and in amyloid β-peptide-induced toxicity (Liu et al., 2009) in rats. Luteolin was also shown to induce the synthesis and secretion of neurotrophic factors in cultured rat astrocytes (Xu et al., 2013). The related flavonoid 7,8-dihydroxyflavone mimicked the activity of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Jang et al., 2010b). Moreover, the related flavonoids 4′-methoxyflavone and 3′,4′-dimethoxyflavone were shown to be neuroprotective (Fatokun et al., 2013). Luteolin also protected again cognitive dysfunction induced by chronic cerebral hypoperfusion is rats (Hagedorn et al., 2010; Fu et al., 2014) and high fat-diet-induced cognitive dysfunction in mice (Liu et al., 2014). Furthermore, luteolin (Liu et al., 2009; Jang et al., 2010a; Yoo et al., 2013) increased memory and inhibited autism-like behavior in a mouse model of autism (Parker-Athill et al., 2009). The luteolin structurally related flavonol quercetin protected against amyloid β-induced neurotoxicity (Liu et al., 2013; Regitz et al., 2014) and improved cognition in a mouse model of AD (Wang et al., 2014). In fact, quercetin-o-glucuronide reduced the generation of β-amyloid in primary cultured neurons (Ho et al., 2013).

A luteolin containing formulation significantly improved attention and behavior in children with autism (Theoharides et al., 2012b; Taliou et al., 2013). This dietary supplement contains luteolin (100 mg per softgel capsule, >98% pure) formulated in olive fruit extract (<0.001 oleic acid acidity and water content), which increases oral absorption.

Olive fruit extract contains hydroxytyrosol, which has been reported to protect against brain hypoxia (Gonzalez-Correa et al., 2008) and oleocanthal, which inhibits fibrilization of tau proteins (Li et al., 2009a) and reduces aggregation of Aβ oligomers (Pitt et al., 2009) implicated in AD. Moreover, olive oil (Mohagheghi et al., 2010) and olive leaf extract (Mohagheghi et al., 2011) reduced BBB permeability. Data from animal studies indicate that use of olive oil (Tsai et al., 2007; Farr et al., 2012; Martinez-Lapiscina et al., 2013) increased memory.

Flavonoids have been proposed as possible therapeutic agents for CAD (Kempuraj et al., 2005; Perez-Vizcaino and Duarte, 2010; Yap et al., 2010). A meta analysis of epidemiological studies showed an inverse relationship between flavonol/flavone intake and CAD (Perez-Vizcaino and Duarte, 2010). A review of publications from European and US population cohorts reported that consumption of flavonoids was strongly associated with lower CAD mortality (Peterson et al., 2012). A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical study using the polyhenolic compound Pycnogenol showed improved endothelial function in patients with CAD (Enseleit et al., 2012) and a study of 2-week consumption of a polyphenolic drink lowered urinary biomarkers of CAD (Mullen et al., 2011).

Luteolin suppressed adipocyte activation of macrophages, inhibited endothelial inflammation (Ando et al., 2009; Deqiu et al., 2011), increased insulin sensitivity of the endothelium (Deqiu et al., 2011), and prevented niacin-induced flush (Kalogeromitros et al., 2008; Papaliodis et al., 2008). Luteolin also protected low density lipoprotein from oxidation (Brown and Rice-Evans, 1998) and improved experimentally diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance (Xu et al., 2014), as well as protected against high fat-diet induced cognitive deficits (Liu et al., 2014) in mice.

Mechanism of Flavonoid Action

Luteolin inhibits multiple signaling steps including PI3K, NFκB, PKCθ, STAT3, and intracellular calcium ions (Kempuraj et al., 2005; Lopez-Lazaro, 2009). Flavonoids also inhibit MC degranulation by interacting with distinct vesicle-dependent SNARE complexes (Yang et al., 2013). It was recently reported that certain flavonoids inhibited cytokine expression in mouse bone marrow-derived mast cell by interfering with IL-33 signaling (Funakoshi-Tago et al., 2015).

Flavonoids can also inhibit acetylcholinesterase (Tsai et al., 2007; Boudouda et al., 2015), which will increase acetylcholine and improve memory (Table 1). It is of interest that luteolin further inhibits release of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate (Lin et al., 2011), while it activates receptors for the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-amino butyric acid (GABA) independent of GABA, suggesting it may also have a calming effect (Hanrahan et al., 2011). In fact, benzodiazepines that act by activating GABA receptors were shown to bind to MCs (Miller et al., 1988).

Conclusion

Presently, 1 in 20 individuals over the age of 65 has dementia, while just the European population over 65 will rise from 17.4% in 2010 to 24% in 2030 or about 200 million people (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division, 2015). The cost of caring for AD patients in the US is estimated to be $220 billion per year (Alzheimers Association, 2015). These numbers do not include brain “fog” present in the others disorders discussed. For instance, the cost of ASDs to the US economy is estimated at $ 180 billion per year. It is therefore obvious that any effective treatment will make a significant difference both to the health of the patients and to the economy. However, in spite of intensive research, clinical trials targeting Aβ have failed (Corbett et al., 2012) necessitating new therapeutic targets and there are no effective treatments for the other neuropsychiatric disorders discussed.

Flavonoids are generally considered safe (Kawanishi et al., 2005; Harwood et al., 2007; Seelinger et al., 2008; Corcoran et al., 2012; Theoharides et al., 2014). Unfortunately, some of the cheaper sources of flavonoids found in dietary supplements are from peanut shells and fava beans and may lead to anaphylactic reactions or hemolytic anemia to allergic and G6PD-deficient individuals, respectively. Flavonoids are extensively metabolized (Chen et al., 2014) primarily through glucoronidation, methylation, and sulphation (Hollman et al., 1995; Hollman and Katan, 1997). Therefore, flavonoids must be used with caution when administered with other natural polyphenolic molecules (e.g., curcumin, resveratrol) or drugs metabolized by the liver as they may affect the blood levels of themselves or of other drugs (Theoharides and Asadi, 2012). Tetramethoxyluteolin is already methylated and less likely to affect liver metabolism, is more stable (Walle, 2007), and has better bioavailability (Wei et al., 2014). Intranasal tetramethoxyluteolin preparations would offer the additional advantage of delivering the flavonoid directly to the brain through the cribriform plexus as was shown for some other compounds (Zhuang et al., 2011).

Disclosures

TT is on the Scientific Advisory Board of the Mastocytosis Society (http://www.tmsforacure.org/) and on the Board of Directors of two nonprofit foundations (http://www.braingate.org; www.autismfreebrain.org). JS is the TMS regional patient support leader for Michigan. TT is the recipient of US Patent No. 8,268,365 for the treatment of brain inflammation, US Patent No. 7,906,153 for the treatment of multiple sclerosis, and US Patent No. 13/009.282 for the diagnosis and treatment of ASDs.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Miss Smaro Panagiotidou for her word processing and drawing skills. This work was supported in part by grants from the US NIH (NS71361), as well as the Autism Research Institute, Mastocytosis Society, the Johnson Botsford Johnson Fnd, the BHARE Fnd, the Michael and Katherine Johnson Family Fnd, the National Autism Association and Safe Minds.

References

Abraham, S. N., and St John, A. L. (2010). Mast cell-orchestrated immunity to pathogens. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 440–452. doi: 10.1038/nri2782

Aguilar-Valles, A., Inoue, W., Rummel, C., and Luheshi, G. N. (2015). Obesity, adipokines and neuroinflammation. Neuropharmacology 96(Pt. A), 124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.12.023

Alevizos, M., Karagkouni, A., Panagiotidou, S., Vasiadi, M., and Theoharides, T. C. (2013). Stress triggers coronary mast cells leading to cardiac events. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 112, 309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2013.09.017

Alstadhaug, K. B. (2014). Histamine in migraine and brain. Headache 54, 246–259. doi: 10.1111/head.12293

Alvarez, E. O., Ruarte, M. B., and Banzan, A. M. (2001). Histaminergic systems of the limbic complex on learning and motivation. Behav. Brain Res. 124, 195–202. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(01)00213-3

Alzheimers Association. (2015). 2015 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 11, 332–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003

Ando, C., Takahashi, N., Hirai, S., Nishimura, K., Lin, S., Uemura, T., et al. (2009). Luteolin, a food-derived flavonoid, suppresses adipocyte-dependent activation of macrophages by inhibiting JNK activation. FEBS Lett. 583, 3649–3654. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.045

Arnoldussen, I. A., Kiliaan, A. J., and Gustafson, D. R. (2014). Obesity and dementia: adipokines interact with the brain. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 24, 1982–999. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.03.002

Asadi, S., Zhang, B., Weng, Z., Angelidou, A., Kempuraj, D., Alysandratos, K. D., et al. (2010). Luteolin and thiosalicylate inhibit HgCl(2) and thimerosal-induced VEGF release from human mast cells. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 23, 1015–1020.

Banuelos-Cabrera, I., Valle-Dorado, M. G., Aldana, B. I., Orozco-Suarez, S. A., and Rocha, L. (2014). Role of histaminergic system in blood-brain barrier dysfunction associated with neurological disorders. Arch. Med Res. 45, 677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2014.11.010

Baptista, F. I., Henriques, A. G., Silva, A. M., Wiltfang, J., and da Cruz e Silva, O. A. (2014). Flavonoids as therapeutic compounds targeting key proteins involved in Alzheimer's disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 5, 83–92. doi: 10.1021/cn400213r

Beumer, W., Gibney, S. M., Drexhage, R. C., Pont-Lezica, L., Doorduin, J., Klein, H. C., et al. (2012). The immune theory of psychiatric diseases: a key role for activated microglia and circulating monocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 92, 959–975. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0212100

Blank, U., and Rivera, J. (2004). The ins and outs of IgE-dependent mast-cell exocytosis. Trends Immunol. 25, 266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.005

Bodmer, S., Imark, C., and Kneubuhl, M. (1999). Biogenic amines in foods: histamine and food processing. Inflamm. Res. 48, 296–300. doi: 10.1007/s000110050463

Boudouda, H. B., Zeghib, A., Karioti, A., Bilia, A. R., Ozturk, M., Aouni, M., et al. (2015). Antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-cholinesterase potential and flavonol glycosides of Biscutella raphanifolia (Brassicaceae). Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 28, 153–158.

Brewer, J. H., Thrasher, J. D., Straus, D. C., Madison, R. A., and Hooper, D. (2013). Detection of mycotoxins in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Toxins 5, 605–617. doi: 10.3390/toxins5040605

Brioni, J. D., Esbenshade, T. A., Garrison, T. R., Bitner, S. R., and Cowart, M. D. (2011). Discovery of histamine H3 antagonists for the treatment of cognitive disorders and Alzheimer's disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 336, 38–46. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.166876

Brown, J. E., and Rice-Evans, C. A. (1998). Luteolin-rich artichoke extract protects low density lipoprotein from oxidation in vitro. Free Radic. Res. 29, 247–255. doi: 10.1080/10715769800300281

Bryniarski, K., Ptak, W., Jayakumar, A., Pullmann, K., Caplan, M. J., Chairoungdua, A., et al. (2013). Antigen-specific, antibody-coated, exosome-like nanovesicles deliver suppressor T-cell microRNA-150 to effector T cells to inhibit contact sensitivity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 132, 170–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.048

Byrne, M. L., O'Brien-Simpson, N. M., Mitchell, S. A., and Allen, N. B. (2015). Adolescent-onset depression: are obesity and inflammation developmental mechanisms or outcomes? Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. doi: 10.1007/s10578-014-0524-9. [Epub ahead of print].

Cao, J., Papadopoulou, N., Kempuraj, D., Boucher, W. S., Sugimoto, K., Cetrulo, C. L., et al. (2005). Human mast cells express corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptors and CRH leads to selective secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor. J. Immunol. 174, 7665–7675. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7665

Chakraborty, S., Kaushik, D. K., Gupta, M., and Basu, A. (2010). Inflammasome signaling at the heart of central nervous system pathology. J. Neurosci. Res. 88, 1615–1631. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22343

Chen, H. Q., Jin, Z. Y., Wang, X. J., Xu, X. M., Deng, L., and Zhao, J. W. (2008). Luteolin protects dopaminergic neurons from inflammation-induced injury through inhibition of microglial activation. Neurosci. Lett. 448, 175–179. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.10.046

Chen, Z., Zheng, S., Li, L., and Jiang, H. (2014). Metabolism of flavonoids in human: a comprehensive review. Curr. Drug Metab. 15, 48–61. doi: 10.2174/138920021501140218125020

Chrostowska, M., Szyndler, A., Hoffmann, M., and Narkiewicz, K. (2013). Impact of obesity on cardiovascular health. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 27, 147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2013.01.004

Corbett, A., Smith, J., and Ballard, C. (2012). New and emerging treatments for Alzheimer's disease. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 12, 535–543. doi: 10.1586/ern.12.43

Corcoran, M. P., McKay, D. L., and Blumberg, J. B. (2012). Flavonoid basics: chemistry, sources, mechanisms of action, and safety. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 31, 176–189. doi: 10.1080/21551197.2012.698219

Crago, B. R., Gray, M. R., Nelson, L. A., Davis, M., Arnold, L., and Thrasher, J. D. (2003). Psychological, neuropsychological, and electrocortical effects of mixed mold exposure. Arch. Environ. Health 58, 452–463. doi: 10.3200/AEOH.58.8.452-463

da Silveira, C. K., Furini, C. R., Benetti, F., Monteiro, S. C., and Izquierdo, I. (2013). The role of histamine receptors in the consolidation of object recognition memory. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 103, 64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.04.001

Deqiu, Z., Kang, L., Jiali, Y., Baolin, L., and Gaolin, L. (2011). Luteolin inhibits inflammatory response and improves insulin sensitivity in the endothelium. Biochimie 93, 506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.11.002

Dirscherl, K., Karlstetter, M., Ebert, S., Kraus, D., Hlawatsch, J., Walczak, Y., et al. (2010). Luteolin triggers global changes in the microglial transcriptome leading to a unique anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective phenotype. J. Neuroinflammation 7:3. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-3

Donelan, J., Boucher, W., Papadopoulou, N., Lytinas, M., Papaliodis, D., and Theoharides, T. C. (2006). Corticotropin-releasing hormone induces skin vascular permeability through a neurotensin-dependent process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 7759–7764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602210103

Dong, H., Zhang, X., and Qian, Y. (2014). Mast cells and neuroinflammation. Med. Sci. Monit. Basic Res. 20, 200–206. doi: 10.12659/MSMBR.893093

Drzezga, A., Becker, J. A., Van Dijk, K. R., Sreenivasan, A., Talukdar, T., Sullivan, C., et al. (2011). Neuronal dysfunction and disconnection of cortical hubs in non-demented subjects with elevated amyloid burden. Brain 134, 1635–1646. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr066

Empting, L. D. (2009). Neurologic and neuropsychiatric syndrome features of mold and mycotoxin exposure. Toxicol. Ind. Health 25, 577–581. doi: 10.1177/0748233709348393

Enoksson, M., Lyberg, K., Moller-Westerberg, C., Fallon, P. G., Nilsson, G., and Lunderius-Andersson, C. (2011). Mast cells as sensors of cell injury through IL-33 recognition. J. Immunol. 186, 2523–2528. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003383

Enseleit, F., Sudano, I., Periat, D., Winnik, S., Wolfrum, M., Flammer, A. J., et al. (2012). Effects of Pycnogenol on endothelial function in patients with stable coronary artery disease: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Eur. Heart J. 33, 1589–1597. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr482

Esposito, P., Chandler, N., Kandere-Grzybowska, K., Basu, S., Jacobson, S., Connolly, R., et al. (2002). Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and brain mast cells regulate blood-brain-barrier permeability induced by acute stress. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 303, 1061–1066. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.038497

Esposito, P., Gheorghe, D., Kandere, K., Pang, X., Conally, R., Jacobson, S., et al. (2001). Acute stress increases permeability of the blood-brain-barrier through activation of brain mast cells. Brain Res. 888, 117–127. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)03026-2

Farr, S. A., Price, T. O., Dominguez, L. J., Motisi, A., Saiano, F., Niehoff, M. L., et al. (2012). Extra virgin olive oil improves learning and memory in SAMP8 mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 28, 81–92. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110662

Fatokun, A. A., Liu, J. O., Dawson, V. L., and Dawson, T. M. (2013). Identification through high-throughput screening of 4′-methoxyflavone and 3′,4′-dimethoxyflavone as novel neuroprotective inhibitors of parthanatos. Br. J. Pharmacol. 169, 1263–1278. doi: 10.1111/bph.12201

Franco, J. L., Posser, T., Missau, F., Pizzolatti, M. G., Dos Santos, A. R., Souza, D. O., et al. (2010). Structure-activity relationship of flavonoids derived from medicinal plants in preventing methylmercury-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 30, 272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2010.07.003

Fu, X., Zhang, J., Guo, L., Xu, Y., Sun, L., Wang, S., et al. (2014). Protective role of luteolin against cognitive dysfunction induced by chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 126, 122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2014.09.005

Funakoshi-Tago, M., Okamoto, K., Izumi, R., Tago, K., Yanagisawa, K., Narukawa, Y., et al. (2015). Anti-inflammatory activity of flavonoids in Nepalese propolis is attributed to inhibition of the IL-33 signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 25, 189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.01.012

Galli, S. J., Grimbaldeston, M., and Tsai, M. (2008a). Immunomodulatory mast cells: negative, as well as positive, regulators of immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 478–486. doi: 10.1038/nri2327

Galli, S. J., Tsai, M., and Piliponsky, A. M. (2008b). The development of allergic inflammation. Nature 454, 445–454. doi: 10.1038/nature07204

Gonzalez-Correa, J. A., Navas, M. D., Lopez-Villodres, J. A., Trujillo, M., Espartero, J. L., and De La Cruz, J. P. (2008). Neuroprotective effect of hydroxytyrosol and hydroxytyrosol acetate in rat brain slices subjected to hypoxia-reoxygenation. Neurosci. Lett. 446, 143–146. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.09.022

Gordon, W. A., Cantor, J. B., Johanning, E., Charatz, H. J., Ashman, T. A., Breeze, J. L., et al. (2004). Cognitive impairment associated with toxigenic fungal exposure: a replication and extension of previous findings. Appl. Neuropsychol. 11, 65–74. doi: 10.1207/s15324826an1102_1

Grosso, C., Valentao, P., Ferreres, F., and Andrade, P. B. (2013). The use of flavonoids in central nervous system disorders. Curr. Med. Chem. 20, 4697–4719. doi: 10.2174/09298673113209990155

Gupta, S., Ellis, S. E., Ashar, F. N., Moes, A., Bader, J. S., Zhan, J., et al. (2014). Transcriptome analysis reveals dysregulation of innate immune response genes and neuronal activity-dependent genes in autism. Nat. Commun. 5:5748. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6748

Haas, H. L., Sergeeva, O. A., and Selbach, O. (2008). Histamine in the nervous system. Physiol. Rev. 88, 1183–1241. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2007

Hagedorn, M., Carter, V. L., Leong, J. C., and Kleinhans, F. W. (2010). Physiology and cryosensitivity of coral endosymbiotic algae (Symbiodinium). Cryobiology 60, 147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2009.10.005

Hamdani, N., Doukhan, R., Kurtlucan, O., Tamouza, R., and Leboyer, M. (2013). Immunity, inflammation, and bipolar disorder: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 15:387. doi: 10.1007/s11920-013-0387-y

Hanrahan, J. R., Chebib, M., and Johnston, G. A. (2011). Flavonoid modulation of GABA(A) receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 163, 234–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01228.x

Harwood, M., Nielewska-Nikiel, B., Borzelleca, J. F., Flamm, G. W., Williams, G. M., and Lines, T. C. (2007). A critical review of the data related to the safety of quercetin and lack of evidence of in vivo toxicity, including lack of genotoxic/carcinogenic properties. Food Chem. Toxicol. 45, 2179–2205. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.05.015

Heneka, M. T., Carson, M. J., Khoury, J. E., Landreth, G. E., Brosseron, F., Feinstein, D. L., et al. (2015). Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 14, 388–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5

Ho, L., Ferruzzi, M. G., Janle, E. M., Wang, J., Gong, B., Chen, T. Y., et al. (2013). Identification of brain-targeted bioactive dietary quercetin-3-O-glucuronide as a novel intervention for Alzheimer's disease. FASEB J. 27, 769–781. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-212118

Hodes, G. E., Pfau, M. L., Leboeuf, M., Golden, S. A., Christoffel, D. J., Bregman, D., et al. (2014). Individual differences in the peripheral immune system promote resilience versus susceptibility to social stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 16136–16141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415191111

Hollman, P. C., de Vries, J. H., van Leeuwen, S. D., Mengelers, M. J., and Katan, M. B. (1995). Absorption of dietary quercetin glycosides and quercetin in healthy ileostomy volunteers. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 62, 1276–1282.

Hollman, P. C., and Katan, M. B. (1997). Absorption, metabolism and health effects of dietary flavonoids in man. Biomed. Pharmacother. 51, 305–310. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(97)88045-6

Hsiao, E. Y., McBride, S. W., Chow, J., Mazmanian, S. K., and Patterson, P. H. (2012). Modeling an autism risk factor in mice leads to permanent immune dysregulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 12776–12781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202556109

Huang, M., Pang, X., Karalis, K., and Theoharides, T. C. (2003). Stress-induced interleukin-6 release in mice is mast cell-dependent and more pronounced in Apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Cardiovasc. Res. 59, 241–249. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(03)00340-7

Iantorno, M., Campia, U., Di, D. N., Nistico, S., Forleo, G. B., Cardillo, C., et al. (2014). Obesity, inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 28, 169–176.

Jager, A. K., and Saaby, L. (2011). Flavonoids and the CNS. Molecules 16, 1471–1485. doi: 10.3390/molecules16021471

Jang, S., Dilger, R. N., and Johnson, R. W. (2010a). Luteolin inhibits microglia and alters hippocampal-dependent spatial working memory in aged mice. J. Nutr. 140, 1892–1898. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.123273

Jang, S., Kelley, K. W., and Johnson, R. W. (2008). Luteolin reduces IL-6 production in microglia by inhibiting JNK phosphorylation and activation of AP-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 7534–7539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802865105

Jang, S. W., Liu, X., Yepes, M., Shepherd, K. R., Miller, G. W., Liu, Y., et al. (2010b). A selective TrkB agonist with potent neurotrophic activities by 7,8-dihydroxyflavone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 2687–2692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913572107

Jones, K. A., and Thomsen, C. (2013). The role of the innate immune system in psychiatric disorders. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 53, 52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.10.002

Jones, Q. R., Warford, J., Rupasinghe, H. P., and Robertson, G. S. (2012). Target-based selection of flavonoids for neurodegenerative disorders. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 33, 602–610. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.08.002

Joulia, R., Gaudenzio, N., Rodrigues, M., Lopez, J., Blanchard, N., Valitutti, S., et al. (2015). Mast cells form antibody-dependent degranulatory synapse for dedicated secretion and defence. Nat. Commun. 6:6174. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7174

Kalesnikoff, J., and Galli, S. J. (2008). New developments in mast cell biology. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1215–1223. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.216

Kalogeromitros, D., Makris, M., Chliva, C., Aggelides, X., Kempuraj, D., and Theoharides, T. C. (2008). A quercetin containing supplement reduces niacin-induced flush in humans. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 21, 509–514. doi: 10.1177/039463200802100304

Kalogeromitros, D., Syrigou, E. I., Makris, M., Kempuraj, D., Stavrianeas, N. G., Vasiadi, M., et al. (2007). Nasal provocation of patients with allergic rhinitis and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 98, 269–273. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60717-X

Kamei, C., and Tasaka, K. (1993). Effect of histamine on memory retrieval in old rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 16, 128–132. doi: 10.1248/bpb.16.128

Kandere-Grzybowska, K., Letourneau, R., Kempuraj, D., Donelan, J., Poplawski, S., Boucher, W., et al. (2003). IL-1 induces vesicular secretion of IL-6 without degranulation from human mast cells. J. Immunol. 171, 4830–4836. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4830

Kao, T. K., Ou, Y. C., Lin, S. Y., Pan, H. C., Song, P. J., Raung, S. L., et al. (2011). Luteolin inhibits cytokine expression in endotoxin/cytokine-stimulated microglia. J. Nutr. Biochem. 22, 612–624. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.01.011

Kawanishi, S., Oikawa, S., and Murata, M. (2005). Evaluation for safety of antioxidant chemopreventive agents. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 7, 1728–1739. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1728

Kawikova, I., and Askenase, P. W. (2015). Diagnostic and therapeutic potentials of exosomes in CNS diseases. Brain Res. 1617, 63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.09.070

Kempuraj, D., Madhappan, B., Christodoulou, S., Boucher, W., Cao, J., Papadopoulou, N., et al. (2005). Flavonols inhibit proinflammatory mediator release, intracellular calcium ion levels and protein kinase C theta phosphorylation in human mast cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 145, 934–944. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706246

Kempuraj, D., Tagen, M., Iliopoulou, B. P., Clemons, A., Vasiadi, M., Boucher, W., et al. (2008). Luteolin inhibits myelin basic protein-induced human mast cell activation and mast cell dependent stimulation of Jurkat T cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 155, 1076–1084. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.356

Kerr, D., Krishnan, C., Pucak, M. L., and Carmen, J. (2005). The immune system and neuropsychiatric diseases. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 17, 443–449. doi: 10.1080/0264830500381435

Khemka, V. K., Bagchi, D., Bandyopadhyay, K., Bir, A., Chattopadhyay, M., Biswas, A., et al. (2014). Altered serum levels of adipokines and insulin in probable Alzheimer's disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 41, 525–533. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140006

Kilburn, K. H. (2009). Neurobehavioral and pulmonary impairment in 105 adults with indoor exposure to molds compared to 100 exposed to chemicals. Toxicol. Ind. Health 25, 681–692. doi: 10.1177/0748233709348390

Kiliaan, A. J., Arnoldussen, I. A., and Gustafson, D. R. (2014). Adipokines: a link between obesity and dementia? Lancet Neurol. 13, 913–923. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70085-7

Kimata, M., Shichijo, M., Miura, T., Serizawa, I., Inagaki, N., and Nagai, H. (2000). Effects of luteolin, quercetin and baicalein on immunoglobulin E-mediated mediator release from human cultured mast cells. Clin. Exp. Allergy 30, 501–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00768.x

Kovanen, P. T., Kaartinen, M., and Paavonen, T. (1995). Infiltrates of activated mast cells at the site of coronary atheromatous erosion or rupture in myocardial infarction. Circulation 92, 1084–1088. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.92.5.1084

Kritas, S. K., Caraffa, A., Antinolfi, P., Saggini, A., Pantalone, A., Rosati, M., et al. (2014a). Nerve growth factor interactions with mast cells. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 27, 15–19.

Kritas, S. K., Saggini, A., Cerulli, G., Caraffa, A., Antinolfi, P., Pantalone, A., et al. (2014b). Corticotropin-releasing hormone, microglia and mental disorders. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 27, 163–167.

Laine, P., Kaartinen, M., Penttilä, A., Panula, P., Paavonen, T., and Kovanen, P. T. (1999). Association between myocardial infarction and the mast cells in the adventitia of the infarct-related coronary artery. Circulation 99, 361–369. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.99.3.361

Landete, J. M., De las, R. B., Marcobal, A., and Munoz, R. (2008). Updated molecular knowledge about histamine biosynthesis by bacteria. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 48, 697–714. doi: 10.1080/10408390701639041

Larsen, F. O., Clementsen, P., Hansen, M., Maltbaek, N., Gravesen, S., Skov, P. S., et al. (1996). The indoor microfungus Trichoderma viride potentiates histamine release from human bronchoalveolar cells. APMIS 104, 673–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1996.tb04928.x

Lebwohl, B., and Ludvigsson, J. F. (2014). Editorial: brain ‘fog’ and coeliac disease - evidence for its existence. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 40, 565. doi: 10.1111/apt.12852

Li, W., Sperry, J. B., Crowe, A., Trojanowski, J. Q., Smith, A. B. III., and Lee, V. M. (2009a). Inhibition of tau fibrillization by oleocanthal via reaction with the amino groups of tau. J. Neurochem. 110, 1339–1351. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06224.x

Li, X., Chauhan, A., Sheikh, A. M., Patil, S., Chauhan, V., Li, X. M., et al. (2009b). Elevated immune response in the brain of autistic patients. J. Neuroimmunol. 207, 111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.12.002

Libby, P., Ridker, P. M., and Maseri, A. (2002). Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation 105, 1135–1143. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104353

Lichtwark, I. T., Newnham, E. D., Robinson, S. R., Shepherd, S. J., Hosking, P., Gibson, P. R., et al. (2014). Cognitive impairment in coeliac disease improves on a gluten-free diet and correlates with histological and serological indices of disease severity. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 40, 160–170. doi: 10.1111/apt.12809

Lin, T. Y., Lu, C. W., Chang, C. C., Huang, S. K., and Wang, S. J. (2011). Luteolin inhibits the release of glutamate in rat cerebrocortical nerve terminals. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 8458–8466. doi: 10.1021/jf201637u

Liu, R., Gao, M., Qiang, G. F., Zhang, T. T., Lan, X., Ying, J., et al. (2009). The anti-amnesic effects of luteolin against amyloid beta(25-35) peptide-induced toxicity in mice involve the protection of neurovascular unit. Neuroscience 162, 1232–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.05.009

Liu, R., Zhang, T. T., Zhou, D., Bai, X. Y., Zhou, W. L., Huang, C., et al. (2013). Quercetin protects against the Abeta(25-35)-induced amnesic injury: involvement of inactivation of rage-mediated pathway and conservation of the NVU. Neuropharmacology 67, 419–431. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.11.018

Liu, Y., Fu, X., Lan, N., Li, S., Zhang, J., Wang, S., et al. (2014). Luteolin protects against high fat diet-induced cognitive deficits in obesity mice. Behav. Brain Res. 267, 178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.02.040

Lopez-Lazaro, M. (2009). Distribution and biological activities of the flavonoid luteolin. Mini. Rev. Med. Chem. 9, 31–59. doi: 10.2174/138955709787001712

Maintz, L., and Novak, N. (2007). Histamine and histamine intolerance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 85, 1185–1196.

Martinez-Lapiscina, E. H., Clavero, P., Toledo, E., San, J. B., Sanchez-Tainta, A., Corella, D., et al. (2013). Virgin olive oil supplementation and long-term cognition: the PREDIMED-NAVARRA randomized, trial. J. Nutr. Health Aging 17, 544–552. doi: 10.1007/s12603-013-0027-6

Mathew, A., Yoshida, Y., Maekawa, T., and Kumar, D. S. (2011). Alzheimer's disease: cholesterol a menace? Brain Res. Bull. 86, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.06.006

Matusik, P., Guzik, B., Weber, C., and Guzik, T. J. (2012). Do we know enough about the immune pathogenesis of acute coronary syndromes to improve clinical practice? Thromb. Haemost. 108, 443–456. doi: 10.1160/TH12-05-0341

McKittrick, C. M., Lawrence, C. E., and Carswell, H. V. (2015). Mast cells promote blood brain barrier breakdown and neutrophil infiltration in a mouse model of focal cerebral ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 35, 638–647. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.239

Mecocci, P., Tinarelli, C., Schulz, R. J., and Polidori, M. C. (2014). Nutraceuticals in cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Front. Pharmacol. 5:147. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00147

Middleton, E. J., Kandaswami, C., and Theoharides, T. C. (2000). The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: implications for inflammation, heart disease and cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 52, 673–751.

Miller, L. G., Lee-Parritz, A., Greenblatt, D. J., and Theoharides, T. C. (1988). High affinity benzodiazepine receptors on rat peritoneal mast cells and RBL-1 cells: binding characteristics and effects on granule secretion. Pharmacology 36, 52–60. doi: 10.1159/000138346

Mohagheghi, F., Bigdeli, M. R., Rasoulian, B., Hashemi, P., and Pour, M. R. (2011). The neuroprotective effect of olive leaf extract is related to improved blood-brain barrier permeability and brain edema in rat with experimental focal cerebral ischemia. Phytomedicine 18, 170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.06.007

Mohagheghi, F., Bigdeli, M. R., Rasoulian, B., Zeinanloo, A. A., and Khoshbaten, A. (2010). Dietary virgin olive oil reduces blood brain barrier permeability, brain edema, and brain injury in rats subjected to ischemia-reperfusion. Sci. World J. 10, 1180–1191. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.128

Molyva, D., Kalokasidis, K., Poulios, C., Dedi, H., Karkavelas, G., Mirtsou, V., et al. (2014). Rupatadine effectively prevents the histamine-induced up regulation of histamine H1R and bradykinin B2R receptor gene expression in the rat paw. Pharmacol. Rep. 66, 952–955. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2014.06.008

Moura, D. S., Georgin-Lavialle, S., Gaillard, R., and Hermine, O. (2014). Neuropsychological features of adult mastocytosis. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am. 34, 407–422. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2014.02.001

Moura, D. S., Sultan, S., Georgin-Lavialle, S., Barete, S., Lortholary, O., Gaillard, R., et al. (2012). Evidence for cognitive impairment in mastocytosis: prevalence, features and correlations to depression. PLoS ONE 7:e39468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039468

Moussion, C., Ortega, N., and Girard, J. P. (2008). The IL-1-like cytokine IL-33 is constitutively expressed in the nucleus of endothelial cells and epithelial cells in vivo: a novel ‘alarmin’? PLoS ONE 3:e3331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003331

Mullen, W., Gonzalez, J., Siwy, J., Franke, J., Sattar, N., Mullan, A., et al. (2011). A pilot study on the effect of short-term consumption of a polyphenol rich drink on biomarkers of coronary artery disease defined by urinary proteomics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 12850–12857. doi: 10.1021/jf203369r

Munkholm, K., Vinberg, M., and Vedel, K. L. (2013). Cytokines in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 144, 16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.010

Nakae, S., Suto, H., Berry, G. J., and Galli, S. J. (2007). Mast cell-derived TNF can promote Th17 cell-dependent neutrophil recruitment in ovalbumin-challenged OTII mice. Blood 109, 3640–3648. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-046128

Nakae, S., Suto, H., Iikura, M., Kakurai, M., Sedgwick, J. D., Tsai, M., et al. (2006). Mast cells enhance T cell activation: importance of mast cell costimulatory molecules and secreted TNF. J. Immunol. 176, 2238–2248. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2238

Nakao, A., Nakamura, Y., and Shibata, S. (2015). The circadian clock functions as a potent regulator of allergic reaction. Allergy 70, 467–473. doi: 10.1111/all.12596

Nautiyal, K. M., Ribeiro, A. C., Pfaff, D. W., and Silver, R. (2008). Brain mast cells link the immune system to anxiety-like behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 18053–18057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809479105

Ocon, A. J. (2013). Caught in the thickness of brain fog: exploring the cognitive symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome. Front. Physiol. 4:63. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00063

Orsetti, M., Ghi, P., and Di, C. G. (2001). Histamine H(3)-receptor antagonism improves memory retention and reverses the cognitive deficit induced by scopolamine in a two-trial place recognition task. Behav. Brain Res. 124, 235–242. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(01)00216-9

Pang, X., Letourneau, R., Rozniecki, J. J., Wang, L., and Theoharides, T. C. (1996). Definitive characterization of rat hypothalamic mast cells. Neuroscience 73, 889–902. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00606-0

Papaliodis, D., Boucher, W., Kempuraj, D., and Theroharides, T. C. (2008). The flavonoid luteolin inhibits niacin-induced flush. Br. J. Pharmacol. 153, 1382–1387. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707668

Pardo, C. A., Vargas, D. L., and Zimmerman, A. W. (2005). Immunity, neuroglia and neuroinflammation in autism. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 17, 485–495. doi: 10.1080/02646830500381930

Parker-Athill, E., Luo, D., Bailey, A., Giunta, B., Tian, J., Shytle, R. D., et al. (2009). Flavonoids, a prenatal prophylaxis via targeting JAK2/STAT3 signaling to oppose IL-6/MIA associated autism. J. Neuroimmunol. 217, 20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.08.012

Passamonti, S., Terdoslavich, M., Franca, R., Vanzo, A., Tramer, F., Braidot, E., et al. (2009). Bioavailability of flavonoids: a review of their membrane transport and the function of bilitranslocase in animal and plant organisms. Curr. Drug Metab. 10, 369–394. doi: 10.2174/138920009788498950

Perez-Vizcaino, F., and Duarte, J. (2010). Flavonols and cardiovascular disease. Mol. Aspects Med. 31, 478–494. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2010.09.002

Peterson, J. J., Dwyer, J. T., Jacques, P. F., and McCullough, M. L. (2012). Associations between flavonoids and cardiovascular disease incidence or mortality in European and US populations. Nutr. Rev. 70, 491–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00508.x

Petra, A. I., Panagiotidou, S., Stewart, J. M., and Theoharides, T. C. (2014). Spectrum of mast cell activation disorders. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 10, 729–739. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2014.906302

Pitt, J., Roth, W., Lacor, P., Smith, A. B. III. Blankenship, M., Velasco, P., et al. (2009). Alzheimer's-associated Abeta oligomers show altered structure, immunoreactivity and synaptotoxicity with low doses of oleocanthal. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 240, 189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.07.018

Pizza, V., Agresta, A., D'Acunto, C. W., Festa, M., and Capasso, A. (2011). Neuroinflamm-aging and neurodegenerative diseases: an overview. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 10, 621–634. doi: 10.2174/187152711796235014

Prester, L. (2011). Biogenic amines in fish, fish products and shellfish: a review. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 28, 1547–1560. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2011.600728

Qiao, H., Andrade, M. V., Lisboa, F. A., Morgan, K., and Beaven, M. A. (2006). FcepsilonR1 and toll-like receptors mediate synergistic signals to markedly augment production of inflammatory cytokines in murine mast cells. Blood 107, 610–618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2271

Raffa, R. B. (2011). A proposed mechanism for chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment (‘chemo-fog’). J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 36, 257–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2010.01188.x

Rea, W. J., Didriksen, N., Simon, T. R., Pan, Y., Fenyves, E. J., and Griffiths, B. (2003). Effects of toxic exposure to molds and mycotoxins in building-related illnesses. Arch. Environ. Health 58, 399–405.

Regitz, C., Dussling, L. M., and Wenzel, U. (2014). Amyloid-beta (Abeta(1-42))-induced paralysis in Caenorhabditis elegans is inhibited by the polyphenol quercetin through activation of protein degradation pathways. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 58, 1931–1940. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201400014

Reinhard, M. J., Satz, P., Scaglione, C. A., D'Elia, L. F., Rassovsky, Y., Arita, A. A., et al. (2007). Neuropsychological exploration of alleged mold neurotoxicity. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 22, 533–543. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.03.006

Rizk, A., Curley, J., Robertson, J., and Raber, J. (2004). Anxiety and cognition in histamine H3 receptor-/- mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 19, 1992–1996. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03251.x

Ross, A. J., Medow, M. S., Rowe, P. C., and Stewart, J. M. (2013). What is brain fog? An evaluation of the symptom in postural tachycardia syndrome. Clin. Auton. Res. 23, 305–311. doi: 10.1007/s10286-013-0212-z

Rossignol, D. A., and Frye, R. E. (2012). A review of research trends in physiological abnormalities in autism spectrum disorders: immune dysregulation, inflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and environmental toxicant exposures. Mol. Psychiatry 17, 389–401. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.165

Rozniecki, J. J., Dimitriadou, V., Lambracht-Hall, M., Pang, X., and Theoharides, T. C. (1999a). Morphological and functional demonstration of rat dura mast cell-neuron interactions in vitro and in vivo. Brain Res 849, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01855-7

Rozniecki, J. J., Letourneau, R., Sugiultzoglu, M., Spanos, C., Gorbach, J., and Theoharides, T. C. (1999b). Differential effect of histamine-3 receptor active agents on brain, but not peritoneal, mast cell activation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 290, 1427–1435.

Sakata, Y., Komamura, K., Hirayama, A., Nanto, S., Kitakaze, M., Hori, M., et al. (1996). Elevation of the plasma histamine concentration in the coronary circulation in patients with variant angina. Am. J. Cardiol. 77, 1121–1126. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(96)00147-6

Sandoval-Cruz, M., Garcia-Carrasco, M., Sanchez-Porras, R., Mendoza-Pinto, C., Jimenez-Hernandez, M., Munguia-Realpozo, P., et al. (2011). Immunopathogenesis of vitiligo. Autoimmun. Rev. 10, 762–765. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.02.004

Schmidt, B. M., Ribnicky, D. M., Lipsky, P. E., and Raskin, I. (2007). Revisiting the ancient concept of botanical therapeutics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 360–366. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0707-360

Schwelberger, H. G. (2010). Histamine intolerance: a metabolic disease? Inflamm. Res. 59(Suppl. 2), S219–S221. doi: 10.1007/s00011-009-0134-3

Seelinger, G., Merfort, I., and Schempp, C. M. (2008). Anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic activities of luteolin. Planta Med. 74, 1667–1677. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1088314

Severance, E. G., Alaedini, A., Yang, S., Halling, M., Gressitt, K. L., Stallings, C. R., et al. (2012). Gastrointestinal inflammation and associated immune activation in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 138, 48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.02.025

Shan, L., Bao, A. M., and Swaab, D. F. (2015). The human histaminergic system in neuropsychiatric disorders. Trends Neurosci. 38, 167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.12.008

Shefler, I., Salamon, P., Hershko, A. Y., and Mekori, Y. A. (2011). Mast cells as sources and targets of membrane vesicles. Curr. Pharm. Des. 17, 3797–3804. doi: 10.2174/138161211798357836

Sheikh, I. A., Ali, R., Dar, T. A., and Kamal, M. A. (2012). An overview on potential neuroprotective compounds for management of Alzheimer's disease. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 11, 1006–1011. doi: 10.2174/1871527311211080010

Shenassa, E. D., Daskalakis, C., Liebhaber, A., Braubach, M., and Brown, M. (2007). Dampness and mold in the home and depression: an examination of mold-related illness and perceived control of one's home as possible depression pathways. Am. J. Public Health 97, 1893–1899. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.093773

Shim, S. Y., Park, J. R., and Byun, D. S. (2012). 6-Methoxyluteolin from Chrysanthemum zawadskii var. latilobum suppresses histamine release and calcium influx via down-regulation of FcepsilonRI alpha chain expression. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 22, 622–627. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1111.11060

Shoemaker, R. C., and House, D. E. (2006). Sick building syndrome (SBS) and exposure to water-damaged buildings: time series study, clinical trial and mechanisms. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 28, 573–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.07.003

Sismanopoulos, N., Delivanis, D. A., Alysandratos, K. D., Angelidou, A., Therianou, A., Kalogeromitros, D., et al. (2012). Mast cells in allergic and inflammatory diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 18, 2261–2277. doi: 10.2174/138161212800165997

Sismanopoulos, N., Delivanis, D. A., Mavrommati, D., Hatziagelaki, E., Conti, P., and Theoharides, T. C. (2013). Do mast cells link obesity and asthma? Allergy 68, 8–15. doi: 10.1111/all.12043

Skaper, S. D., Facci, L., and Giusti, P. (2013). Mast cells, glia and neuroinflammation: partners in crime? Immunology 141, 314–327. doi: 10.1111/imm.12170

Skaper, S. D., Giusti, P., and Facci, L. (2012). Microglia and mast cells: two tracks on the road to neuroinflammation. FASEB J. 26, 3103–3117. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-197194

Skokos, D., Goubran-Botros, H., Roa, M., and Mecheri, S. (2002). Immunoregulatory properties of mast cell-derived exosomes. Mol. Immunol. 38, 1359–1362. doi: 10.1016/S0161-5890(02)00088-3

Smith, J. H., Butterfield, J. H., Pardanani, A., DeLuca, G. C., and Cutrer, F. M. (2011). Neurologic symptoms and diagnosis in adults with mast cell disease. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 113, 570–574. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.05.002

Smith, S. E., Li, J., Garbett, K., Mirnics, K., and Patterson, P. H. (2007). Maternal immune activation alters fetal brain development through interleukin-6. J. Neurosci. 27, 10695–10702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2178-07.2007

Solanki, I., Parihar, P., Mansuri, M. L., and Parihar, M. S. (2015). Flavonoid-based therapies in the early management of neurodegenerative diseases. Adv. Nutr. 6, 64–72. doi: 10.3945/an.114.007500

Spinas, E., Kritas, S. K., Saggini, A., Mobili, A., Caraffa, A., Antinolfi, P., et al. (2014). Role of mast cells in atherosclerosis: a classical inflammatory disease. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 27, 517–521.

Sumpter, T. L., Ho, C. H., Pleet, A. R., Tkacheva, O. A., Shufesky, W. J., Rojas-Canales, D. M., et al. (2015). Autocrine hemokinin-1 functions as an endogenous adjuvant for IgE-mediated mast cell inflammatory responses. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 135, 1019–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.036

Sun, Y., Li, D. G., Li, Q., Huang, L., He, Z., Zhang, F., et al. (2015). Relationship between adipoq gene polymorphism and lipid levels and diabetes. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 29, 221–227.

Taliou, A., Zintzaras, E., Lykouras, L., and Francis, K. (2013). An open-label pilot study of a formulation containing the anti-inflammatory flavonoid luteolin and its effects on behavior in children with autism spectrum disorders. Clin. Ther. 35, 592–602. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.04.006

Tan, Z. S., and Seshadri, S. (2010). Inflammation in the Alzheimer's disease cascade: culprit or innocent bystander? Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2, 6. doi: 10.1186/alzrt29

Theoharides, T. C. (1990). Mast cells: the immune gate to the brain. Life Sci. 46, 607–617. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90129-F

Theoharides, T. C. (2009). Autism spectrum disorders and mastocytosis. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 22, 859–865.

Theoharides, T. C. (2013a). Atopic conditions in search of pathogenesis and therapy. Clin. Ther. 35, 544–547. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.04.002

Theoharides, T. C. (2013b). Is a subtype of autism “allergy of the brain”? Clin. Ther. 35, 584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.04.009

Theoharides, T. C. (2015). Mast cells promote malaria infection? Clin. Ther. 37, 1374–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.03.014

Theoharides, T. C., Alysandratos, K. D., Angelidou, A., Delivanis, D. A., Sismanopoulos, N., Zhang, B., et al. (2010a). Mast cells and inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1822, 21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.12.014

Theoharides, T. C., Angelidou, A., Alysandratos, K. D., Zhang, B., Asadi, S., Francis, K., et al. (2012a). Mast cell activation and autism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1822, 34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.12.017

Theoharides, T. C., and Asadi, S. (2012). Unwanted interactions among psychotropic drugs and other treatments for Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 32, 437–440. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31825e00e4

Theoharides, T. C., Asadi, S., and Panagiotidou, S. (2012b). A case series of a luteolin formulation (NeuroProtek(R)) in children with autism spectrum disorders. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 25, 317–323.

Theoharides, T. C., Asadi, S., and Patel, A. (2013). Focal brain inflammation and autism. J. Neuroinflammation 10:46. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-46

Theoharides, T. C., Bondy, P. K., Tsakalos, N. D., and Askenase, P. W. (1982). Differential release of serotonin and histamine from mast cells. Nature 297, 229–231. doi: 10.1038/297229a0

Theoharides, T. C., and Cochrane, D. E. (2004). Critical role of mast cells in inflammatory diseases and the effect of acute stress. J. Neuroimmunol. 146, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2003.10.041

Theoharides, T. C., Conti, P., and Economu, M. (2014). Brain inflammation, neuropsychiatric disorders, and immunoendocrine effects of luteolin. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 34, 187–189. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000084

Theoharides, T. C., Donelan, J. M., Papadopoulou, N., Cao, J., Kempuraj, D., and Conti, P. (2004a). Mast cells as targets of corticotropin-releasing factor and related peptides. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 25, 563–568. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.09.007

Theoharides, T. C., and Douglas, W. W. (1978). Secretion in mast cells induced by calcium entrapped within phospholipid vesicles. Science 201, 1143–1145. doi: 10.1126/science.684435

Theoharides, T. C., Doyle, R., Francis, K., Conti, P., and Kalogeromitros, D. (2008). Novel therapeutic targets for autism. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 29, 375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.06.002

Theoharides, T. C., Kempuraj, D., Tagen, M., Conti, P., and Kalogeromitros, D. (2007). Differential release of mast cell mediators and the pathogenesis of inflammation. Immunol. Rev. 217, 65–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00519.x

Theoharides, T. C., and Konstantinidou, A. (2007). Corticotropin-releasing hormone and the blood-brain-barrier. Front. Biosci. 12, 1615–1628. doi: 10.2741/2174

Theoharides, T. C., Petra, A. I., Taracanova, A., Panagiotidou, S., and Conti, P. (2015c). Targeting IL-33 in autoimmunity and inflammation. JPET 354, 24–31. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.222505

Theoharides, T. C., Sismanopoulos, N., Delivanis, D. A., Zhang, B., Hatziagelaki, E. E., and Kalogeromitros, D. (2011a). Mast cells squeeze the heart and stretch the gird: their role in atherosclerosis and obesity. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 32, 534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.05.005

Theoharides, T. C., Spanos, C. P., Pang, X., Alferes, L., Ligris, K., Letourneau, R., et al. (1995). Stress-induced intracranial mast cell degranulation. A corticotropin releasing hormone-mediated effect. Endocrinology 136, 5745–5750.

Theoharides, T. C., Stewart, J. M., Panagiotidou, S., and Melamed, I. (2015b). Mast cells, brain inflammation and autism. Eur. J. Pharmacol. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.03.086. [Epub ahead of print].

Theoharides, T. C., Valent, P., and Akin, C. (2015a). Mast cells, mastocytosis and related disorders. New Engl. J. Med. (in press).

Theoharides, T. C., Weinkauf, C., and Conti, P. (2004b). Brain cytokines and neuropsychiatric disorders. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 24, 577–581. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000148026.86483.4f

Theoharides, T. C., Zhang, B., and Conti, P. (2011b). Decreased mitochondrial function and increased brain inflammation in bipolar disorder and other neuropsychiatric diseases. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 31, 685–687. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318239c190

Theoharides, T. C., Zhang, B., Kempuraj, D., Tagen, M., Vasiadi, M., Angelidou, A., et al. (2010b). IL-33 augments substance P-induced VEGF secretion from human mast cells and is increased in psoriatic skin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 4448–4453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000803107

Thilakarathna, S. H., and Rupasinghe, H. P. (2013). Flavonoid bioavailability and attempts for bioavailability enhancement. Nutrients 5, 3367–3387. doi: 10.3390/nu5093367

Torrealba, F., Riveros, M. E., Contreras, M., and Valdes, J. L. (2012). Histamine and motivation. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 6:51. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2012.00051

Tsai, F. S., Peng, W. H., Wang, W. H., Wu, C. R., Hsieh, C. C., Lin, Y. T., et al. (2007). Effects of luteolin on learning acquisition in rats: involvement of the central cholinergic system. Life Sci. 80, 1692–1698. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.01.055

Tsilioni, I., Panagiotidou, S., and Theoharides, T. C. (2014). Exosomes in neurologic and psychiatric disorders. Clin. Ther. 36, 882–888. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.05.005

United Nations Department of Economic Social Affairs Population Division. (2015). World Population Prospects:The 2010 Revision. Available online at: http://esa.un.org/wpp/documentation/WPP%202010%20publications.htm

Valent, P., Akin, C., Arock, M., Brockow, K., Butterfield, J. H., Carter, M. C., et al. (2012). Definitions, criteria and global classification of mast cell disorders with special reference to mast cell activation syndromes: a consensus proposal. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 157, 215–225. doi: 10.1159/000328760

Vauzour, D. (2014). Effect of flavonoids on learning, memory and neurocognitive performance: relevance and potential implications for Alzheimer's disease pathophysiology. J. Sci. Food Agric. 94, 1042–1056. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6473

Verbeek, R., Plomp, A. C., van Tol, E. A., and van Noort, J. M. (2004). The flavones luteolin and apigenin inhibit in vitro antigen-specific proliferation and interferon-gamma production by murine and human autoimmune T cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 68, 621–629. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.012

Walle, T. (2007). Methylation of dietary flavones greatly improves their hepatic metabolic stability and intestinal absorption. Mol. Pharmcol. 4, 826–832. doi: 10.1021/mp700071d

Wang, D. M., Li, S. Q., Wu, W. L., Zhu, X. Y., Wang, Y., and Yuan, H. Y. (2014). Effects of long-term treatment with quercetin on cognition and mitochondrial function in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurochem. Res. 39, 1533–1543. doi: 10.1007/s11064-014-1343-x

Wei, G., Hwang, L., and Tsai, C. (2014). Absolute bioavailability, pharmacokinetics and excretion of 5,7,30,40-tetramethoxyflavone in rats. J. Funct. Foods 7, 136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2013.10.006

Weng, Z., Patel, A. B., Panagiotidou, S., and Theoharides, T. C. (2014). The novel flavone tetramethoxyluteolin is a potent inhibitor of human mast cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 14, 01574–01577. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.10.032

Wilhelm, M., Silver, R., and Silverman, A. J. (2005). Central nervous system neurons acquire mast cell products via transgranulation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 22, 2238–2248. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04429.x

Xiong, Z., Thangavel, R., Kempuraj, D., Yang, E., Zaheer, S., and Zaheer, A. (2014). Alzheimer's disease: evidence for the expression of interleukin-33 and its receptor ST2 in the brain. J. Alzheimers Dis. 40, 297–308. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132081

Xu, N., Zhang, L., Dong, J., Zhang, X., Chen, Y. G., Bao, B., et al. (2014). Low-dose diet supplement of a natural flavonoid, luteolin, ameliorates diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 58, 1258–1268. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300830

Xu, S. L., Bi, C. W., Choi, R. C., Zhu, K. Y., Miernisha, A., Dong, T. T., et al. (2013). Flavonoids induce the synthesis and secretion of neurotrophic factors in cultured rat astrocytes: a signaling response mediated by estrogen receptor. Evid. Based Complement Alternat. Med. 2013:127075. doi: 10.1155/2013/127075

Yang, C. J., Liu, C. L., Sang, B., Zhu, X. M., and Du, Y. J. (2015). The combined role of serotonin and interleukin-6 as biomarker for autism. Neuroscience 284, 290–296. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.10.011

Yang, Y., Oh, J. M., Heo, P., Shin, J. Y., Kong, B., Shin, J., et al. (2013). Polyphenols differentially inhibit degranulation of distinct subsets of vesicles in mast cells by specific interaction with granule-type-dependent SNARE complexes. Biochem. J. 450, 537–546. doi: 10.1042/BJ20121256

Yap, S., Qin, C., and Woodman, O. L. (2010). Effects of resveratrol and flavonols on cardiovascular function: physiological mechanisms. Biofactors 36, 350–359. doi: 10.1002/biof.111

Yoo, D. Y., Choi, J. H., Kim, W., Nam, S. M., Jung, H. Y., Kim, J. H., et al. (2013). Effects of luteolin on spatial memory, cell proliferation, and neuroblast differentiation in the hippocampal dentate gyrus in a scopolamine-induced amnesia model. Neurol. Res. 35, 813–820. doi: 10.1179/1743132813Y.0000000217

Zhang, B., Alysandratos, K. D., Angelidou, A., Asadi, S., Sismanopoulos, N., Delivanis, D. A., et al. (2011). Human mast cell degranulation and preformed TNF secretion require mitochondrial translocation to exocytosis sites: relevance to atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 127, 1522–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.005

Zhang, B., Asadi, S., Weng, Z., Sismanopoulos, N., and Theoharides, T. C. (2012a). Stimulated human mast cells secrete mitochondrial components that have autocrine and paracrine inflammatory actions. PLoS ONE 7:e49767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049767

Zhang, B., Weng, Z., Sismanopoulos, N., Asadi, S., Therianou, A., Alysandratos, K. D., et al. (2012b). Mitochondria distinguish granule-stored from de novo synthesized tumor necrosis factor secretion in human mast cells. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 159, 23–32. doi: 10.1159/000335178

Zhu, L. H., Bi, W., Qi, R. B., Wang, H. D., and Lu, D. X. (2011). Luteolin inhibits microglial inflammation and improves neuron survival against inflammation. Int. J. Neurosci. 121, 329–336. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2011.569040

Zhu, X., Perry, G., Smith, M. A., and Wang, X. (2012). Abnormal mitochondrial dynamics in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 33, S253–S262. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-129005

Zhuang, X., Xiang, X., Grizzle, W., Sun, D., Zhang, S., Axtell, R. C., et al. (2011). Treatment of brain inflammatory diseases by delivering exosome encapsulated anti-inflammatory drugs from the nasal region to the brain. Mol. Ther. 19, 1769–1779. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.164

Keywords: brain, cognition, cytokines, fog, histamine, inflammation, luteolin, mast cells

Citation: Theoharides TC, Stewart JM, Hatziagelaki E and Kolaitis G (2015) Brain “fog,” inflammation and obesity: key aspects of neuropsychiatric disorders improved by luteolin. Front. Neurosci. 9:225. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00225

Received: 13 April 2015; Accepted: 10 June 2015;

Published: 03 July 2015.

Edited by:

Tommaso Cassano, University of Foggia, ItalyLuca Steardo, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Copyright © 2015 Theoharides, Stewart, Hatziagelaki and Kolaitis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Theoharis C. Theoharides, Department of Integrative Physiology and Pathobiology, Tufts University School of Medicine, 136 Harrison Avenue, Suite J304, Boston, MA 02111, USA,dGhlb2hhcmlzLnRoZW9oYXJpZGVzQHR1ZnRzLmVkdQ==

Theoharis C. Theoharides

Theoharis C. Theoharides Julia M. Stewart1

Julia M. Stewart1