- 1Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine, Harbin, China

- 2The Second Affiliated Hospital of Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine, Harbin, China

Objective: This study focused on the relationship between heart rate and the likelihood of death within 28 days in patients with cerebral infarction without the comorbidity of atrial fibrillation, using patient data extracted from the MIMIC-IV database.

Method: This study involved a retrospective analysis of clinical data from 1,643 individuals with cerebral infarction who were admitted to the ICU. To investigate the role of heart rate in determining patient survival, we applied a variety of statistical techniques such as Cox regression models, survival analysis using Kaplan–Meier plots, and spline-based models. In addition, we performed analyses by patient subgroups to identify any potential variables that could influence the association between HR and 28-day mortality.

Result: In univariate and multivariate analyses, elevated heart rate was strongly associated with higher 28-day mortality, even after adjusting for confounders such as age, sex, comorbidities, and clinical scores.(HR:1.01, 95%,CI:1.01 ~ 1.02, p = 0.019) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis showed that patients with heart rate > 90 beats/min had a significantly lower probability of survival. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis confirmed a nonlinear relationship between heart rate and mortality. Subgroup analyses demonstrated an interaction between heart rate and factors such as hypertension and mechanical ventilation status.

Conclusion: This study highlights the prognostic significance of heart rate as an independent predictor of 28-day mortality in patients with cerebral infarction who do not have atrial fibrillation.

1 Introduction

Cerebral infarction continues to be a major contributor to global death rates and prolonged disability, imposing considerable strain on healthcare systems and society as a whole. As the population ages and the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors like hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia increases, its incidence is anticipated to grow worldwide (1). Despite advances in acute-phase management and secondary prevention strategies, the prognosis for many patients with cerebral infarction remains poor, is often comorbid with cardiovascular disease, and is highly variable depending on individual clinical and physiologic factors (2, 36). For instance, studies focusing on young and middle-aged cerebral infarction patients have identified several independent risk factors for poor prognosis. Among the variables being examined are the severity of neurological impairment assessed through stroke scales, variations in the MTHFR gene, and the condition of elevated blood pressure (3). A one-year follow-up study of 323 patients with acute cerebral infarction revealed that age, NIHSS score at admission, diabetes, and hypertension are key determinants of poor prognosis (4).

Heart rate is a fundamental physiological parameter that reflects the rhythmic contractions of the heart per minute. It is regulated by the autonomic nervous system through the interaction of sympathetic and parasympathetic inputs, maintaining cardiovascular balance (5). In addition to being a marker of cardiovascular function, heart rate is also an important indicator of systemic pressure, metabolic demand, and overall autonomic nervous system balance. Changes in heart rate can provide valuable information about an individual’s hemodynamic and neurological status, especially during acute illness (6). Heart rate variability is significantly reduced in patients with acute cerebral infarction, indicating impaired autonomic nervous system regulation (7). Reduced heart rate variability is linked to an increased risk of mortality and poorer outcomes in individuals experiencing myocardial infarction (8). These findings underscore the potential value of heart rate as an indicator of disease severity and recovery progression across different conditions. Nonetheless, the connection between heart rate and prognosis in patients with cerebral infarction is still not well defined. Some physiological mechanisms, such as systemic inflammation (9) and autonomic dysfunction (10), may link heart rate to the prognosis of cerebral infarction. Although some studies suggest that both tachycardia and bradycardia may influence mortality and neurological recovery (11–13). A retrospective cohort study explored the association between mean heart rate and 30-day mortality in ischemic stroke patients with atrial fibrillation, who were admitted to the intensive care unit within 24 h of hospital arrival. The findings revealed a J-shaped correlation between mean heart rate and 30-day mortality (14). However, there is a lack of strong evidence regarding the connection between heart rate and prognosis in patients with cerebral infarction who do not have atrial fibrillation, leaving the prognostic value of heart rate in this group unclear.

The purpose of this investigation was to assess the potential impact of heart rate on short-term survival outcomes (particularly 28-day mortality) in patients with cerebral infarction who do not have atrial fibrillation. To perform this study, we rely on data extracted from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV (the MIMIC-IV) database, which compiles a wide range of clinical information from ICU patients, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of this relationship. By elucidating the prognostic value of heart rate in cerebral infarction patients, our findings will provide valuable insights for risk stratification and management strategies in clinical practice.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Data source

The MIMIC-IV database is a publicly available, large-scale intensive care unit (ICU) database maintained by the MIT Lab for Computational Physiology (15). This collection features anonymized health records for individuals who received treatment in the ICU at a major medical facility in Boston, Massachusetts, spanning from 2008 through 2019. The dataset includes detailed information on demographics, vital signs, laboratory tests, medications, surgeries, and clinical outcomes, enabling strong epidemiological and clinical investigations. Author Xinrou Song has successfully completed the required training and certification for accessing the MIMIC-IV database (Certificate No. 66625234) and was responsible for extracting the data used in this study.

2.2 Data extraction, patient grouping, and outcome measures

The data for this study were extracted from the MIMIC-IV database, which contains de-identified ICU patient information. Data extraction was performed using PostgreSQL software, and to ensure data consistency and relevance to the acute phase, only data from the first 24 h after patient admission were included.

These data points encompassed: biological sex, age group, racial background, blood parameters such as hematocrit, hemoglobin, platelet count, red cell distribution width (RDW), electrolyte balance (e.g., calcium, chloride, sodium), metabolic markers like blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, international normalized ratio (INR), prothrombin time (PT), and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) and glucose, as well as acid–base balance indicators (anion gap and bicarbonate). Furthermore, clinical factors covered heart rate, blood pressure (systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial), temperature, and specific medical conditions including heart failure, coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, neurological conditions like dementia and paraplegia, pulmonary disorders, liver dysfunction, renal impairment, metabolic diseases such as diabetes and hyperlipidemia. The study also incorporated clinical assessment tools, including SOFA, GCS, which helped in evaluating the severity of patient conditions. Laboratory values were recorded as minimum values, while vital signs (e.g., heart rate) were recorded as averages. The outcome was defined as whether the patient survived or died within 28 days of admission. Patients were divided into two groups: the 28-day survival group and the 28-day mortality group.

2.3 Exclusion criteria

This study investigated the impact of heart rate on the prognosis of stroke patients, using the MIMIC-IV database. Eligibility criteria required patients to have been admitted to the ICU for the first time and diagnosed with cerebral infarction, based on the ICD-9 and ICD-10 criteria.

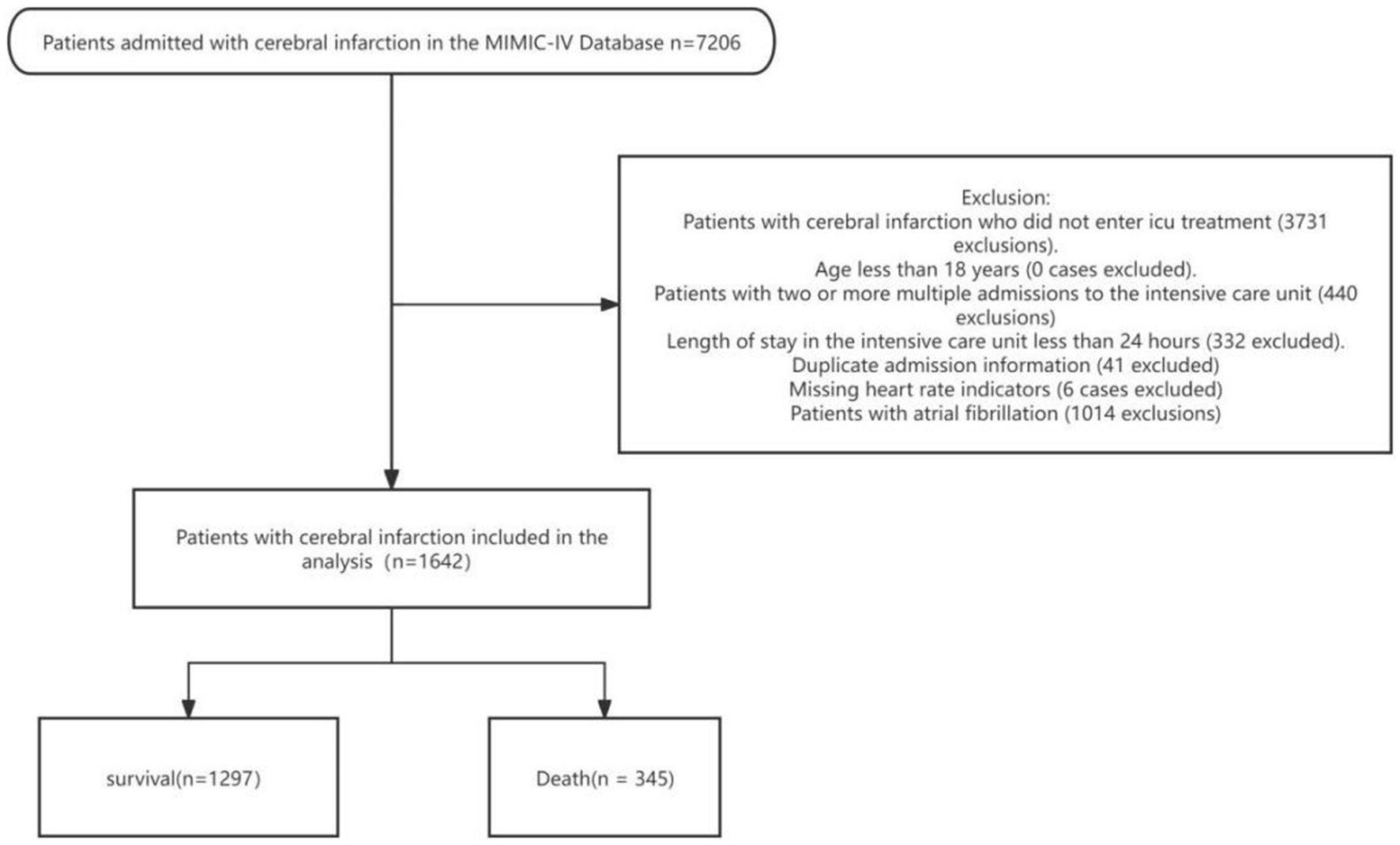

The following exclusion criteria were applied: The inclusion criteria for this study were patients diagnosed with cerebral infarction who received ICU treatment in the MIMIC-IV database. Exclusion criteria included patients who did not undergo ICU treatment, those with multiple ICU admissions, an ICU stay of less than 24 h, duplicate admission records, missing heart rate data, and a history of atrial fibrillation. Additionally, patients under the age of 18 were excluded from the analysis (Figure 1). To reduce potential bias, variables with missing data exceeding 15% were excluded from the analysis. For variables with less than 15% missing data, missing values were imputed using the random forest method from the missForest R package. This approach helped maintain group homogeneity and enhanced the reliability of the subsequent analysis.

2.4 Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2), along with appropriate data handling and modeling tools. The normality of continuous variables was initially assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Variables that followed a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and group differences were assessed using the independent t-test. For non-normally distributed data, results were presented as the median with interquartile range (P25, P75). Categorical data were presented as frequencies and percentages. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare continuous variables across groups, while categorical variables were analyzed using the Pearson chi-square test.

To explore the relationship between heart rate and risk of death, we used a Cox proportional hazards regression model to calculate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). A multivariate model was then constructed to account for potential confounders. Variables with p-values less than 0.05 on univariate analysis were included in the final multivariate model. To assess the relationship between heart rate and in-hospital mortality, four separate models were constructed.

To identify the most relevant heart rate threshold associated with in-hospital mortality, ROC curve analysis was performed, with the Youden index used to determine the optimal cutoff value. This threshold was then applied to divide patients into two groups: one with a low heart rate and the other with a high heart rate. The difference in 28-day survival probabilities between the two groups was assessed using Kaplan–Meier survival curves, followed by a log-rank test. Additionally, non-linear relationships between heart rate and mortality risk were explored using restrictive cubic spline (RCS) analysis. Subgroup analyses were carried out to evaluate the potential moderating effects of gender, age, and comorbidities on the association between heart rate and mortality risk. Interaction terms were incorporated into the models to assess statistical significance, with interaction p-values reported. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Effect sizes and confidence intervals were provided to emphasize the clinical relevance of the findings.

3 Results

3.1 Baseline characteristics of two groups of stroke patients

All participants were categorized into survival and death groups. Their baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The non-survivor group was older (p < 0.001) and had a higher proportion of “other” in the racial distribution (p < 0.001). Their white WBC, anion gap, BUN, creatinine, glucose, RDW, INR, and PT were elevated (p < 0.05) in the mortality group, whereas hematocrit, hemoglobin, platelets, and bicarbonate were elevated (p < 0.05) in the surviving cohort. Vital signs showed higher heart rate and respiratory rate, lower DBP, MBP, and temperature (p < 0.05), higher SOFA score, and lower GCS score (p < 0.05) in the deceased cohort. SBP was higher in the survivor group (p = 0.023) Comorbidities such as myocardial infarction, heart failure, dementia, lung disease, liver disease, renal disease and hypertension were more common in the mortality group (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

3.2 Univariate cox regression analysis of risk factors for mortality in stroke patients

Table 2 summarizes factors significantly associated with mortality (p < 0.05). Higher mortality risk was linked to older age, ‘Others’ race, and comorbidities such as myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, liver disease, and hypertension. Laboratory abnormalities included elevated WBC, anion gap, BUN, glucose, RDW, INR, and PT, while lower hematocrit, hemoglobin, bicarbonate, platelets, and calcium were associated with increased risk. Vital sign differences included higher heart and resp. rate, SpO2, and lower SBP, DBP, and MBP. Additionally, higher SOFA scores and lower GCS scores were significantly related to mortality.

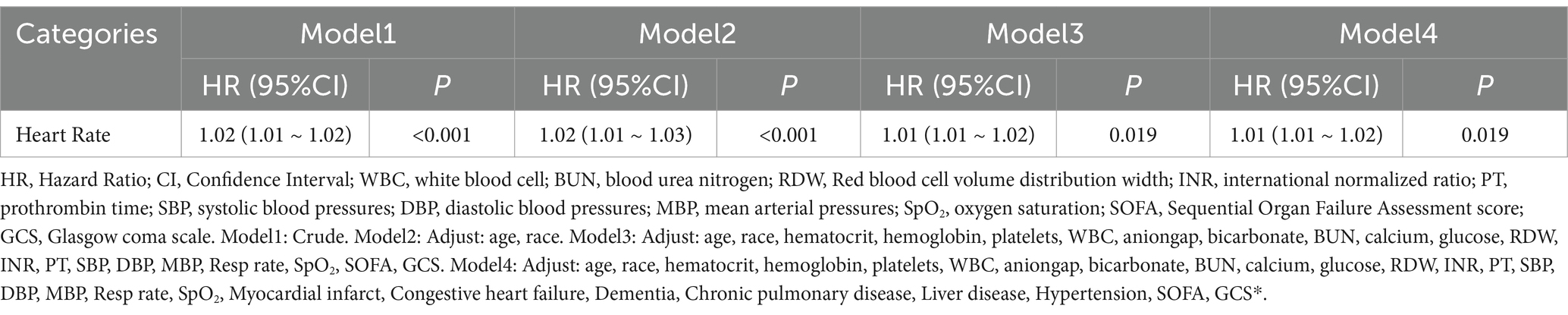

3.3 Multivariable cox regression analysis of heart rate and mortality in stroke patients

Table 3 presents the Cox regression analysis of the relationship between heart rate variability and in-hospital mortality across four models. In all models, heart rate was significantly associated with in-hospital mortality. In the crude model (Model 1), heart rate showed a significant association (p < 0.001), which remained significant after adjusting for age and race in Model 2 (p < 0.001). Further adjustments for laboratory parameters, vital signs, SOFA, and GCS in Model 3 still demonstrated a significant association (p = 0.019). This association persisted in Model 4 after additional adjustments for comorbidities, including myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, liver disease, and hypertension (p = 0.019).

3.4 The relationship between heart rate stratification and 28-day survival rate based on Kaplan–Meier survival curves and ROC analysis

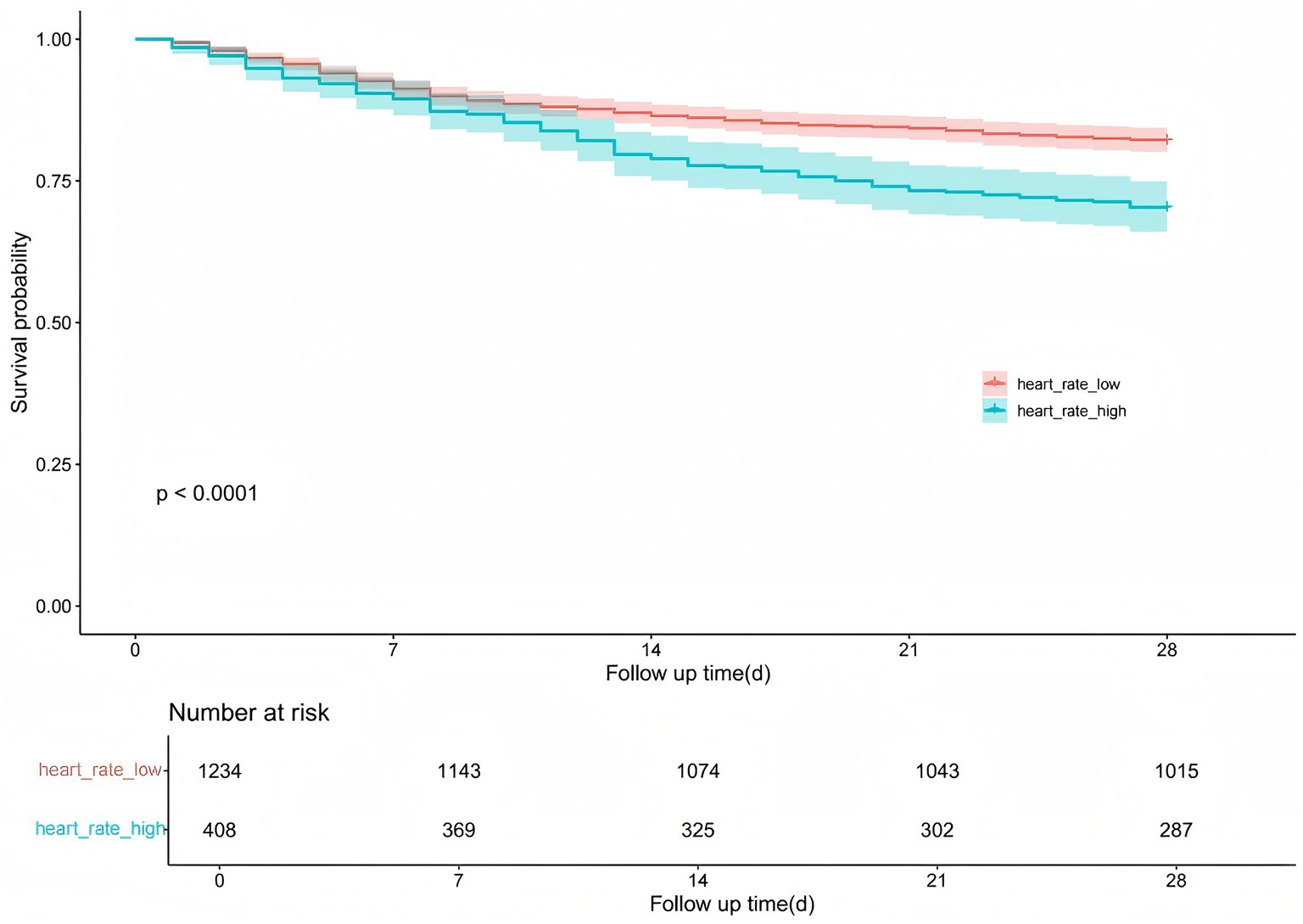

In the Kaplan–Meier survival curve analysis, heart rate stratification (high heart rate vs. low heart rate) was used to assess the 28-day survival probability. To evaluate the predictive value of heart rate for in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients with acute cerebral infarction, we plotted the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. A heart rate threshold of 89.72 beats per minute (sensitivity = 35.36%, specificity = 77.95%) was used to divide patients into two groups: low heart rate (≤89.72 bpm, n = 1,234) and high heart rate (>89.72 bpm, n = 408).

The Kaplan–Meier survival curve illustrates the association between heart rate levels and in-hospital mortality over a 28-day follow-up period. Patients were divided into two groups: high heart rate and low heart rate. The survival probability was significantly lower in the high heart rate group compared to the low heart rate group (p < 0.0001). The number at risk decreased consistently over time in both groups, with 1,234 and 408 patients at baseline in the low and high heart rate groups, respectively. This survival difference remained evident throughout the follow-up period, with the high heart rate group exhibiting a steeper decline in survival probability (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier survival curves: effect of heart rate grouping on the probability of 28-day survival in patients with cerebral infarction.

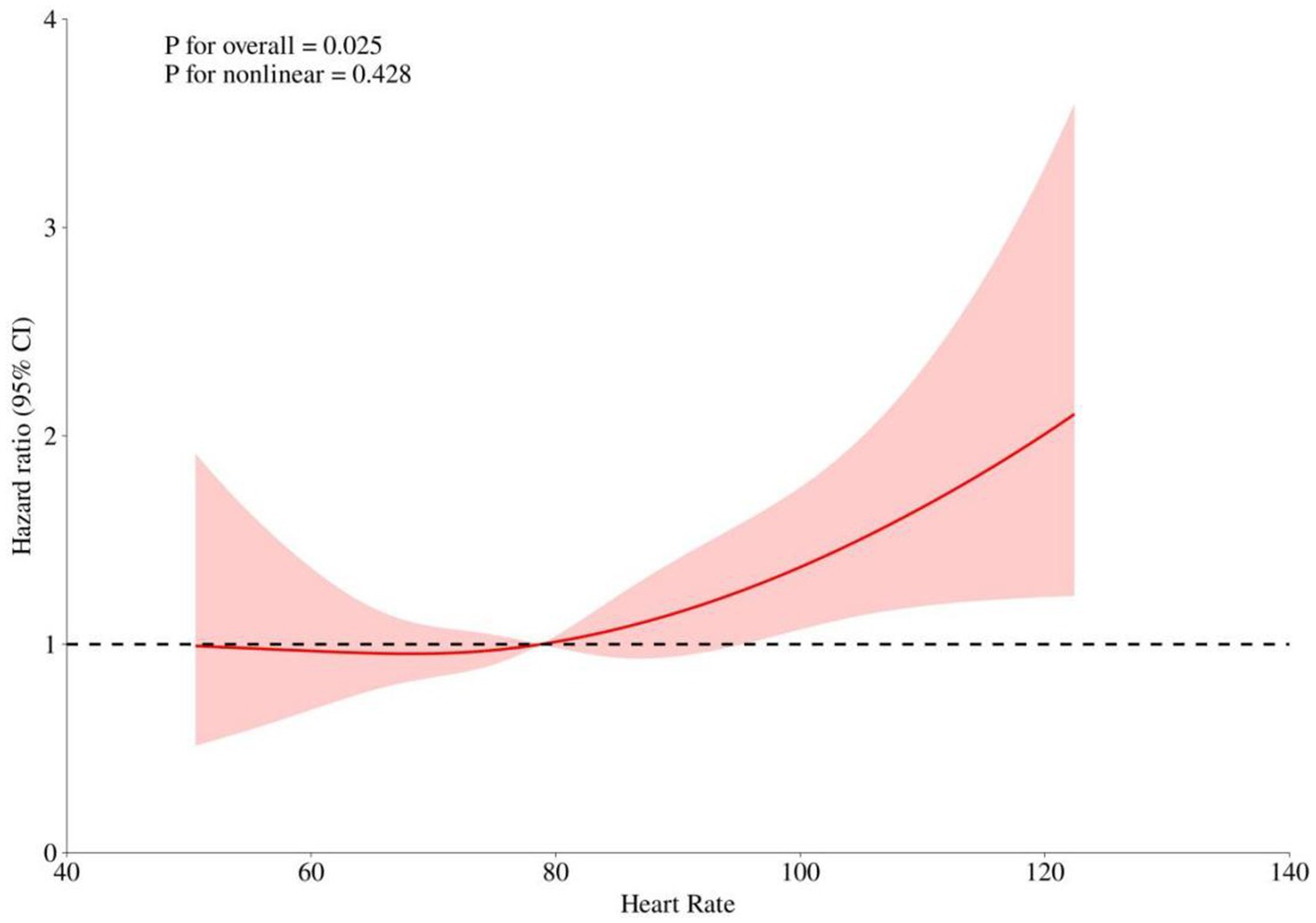

3.5 Non-linear relationship between heart rate and mortality risk based on RCS curve analysis

After adjusting for key covariates including age, race, hematocrit, hemoglobin, platelets, WBC, BUN, glucose, SOFA score, and GCS, RCS models were used to explore the linear relationship between heart rate and 30-day mortality risk. The analysis showed no significant non-linear association (p for non-linearity = 0.428). A positive correlation with increased mortality risk was observed when the heart rate exceeded 78.78 bpm, with the hazard ratio approaching 1 around this threshold (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Restricted Cubic Spline (RCS) Curves Analyzing the Relationship Between Heart Rate and Risk of Death. This figure shows the overall and nonlinear relationship between heart rate and the risk ratio (HR) of death. The solid red line indicates the risk ratio fitted to the RCS model, and the shaded area indicates the 95% confidence interval. The dashed line indicates the reference line for HR = 1.

3.6 Subgroup analysis of the interaction between heart rate and risk of death from cerebral infarction

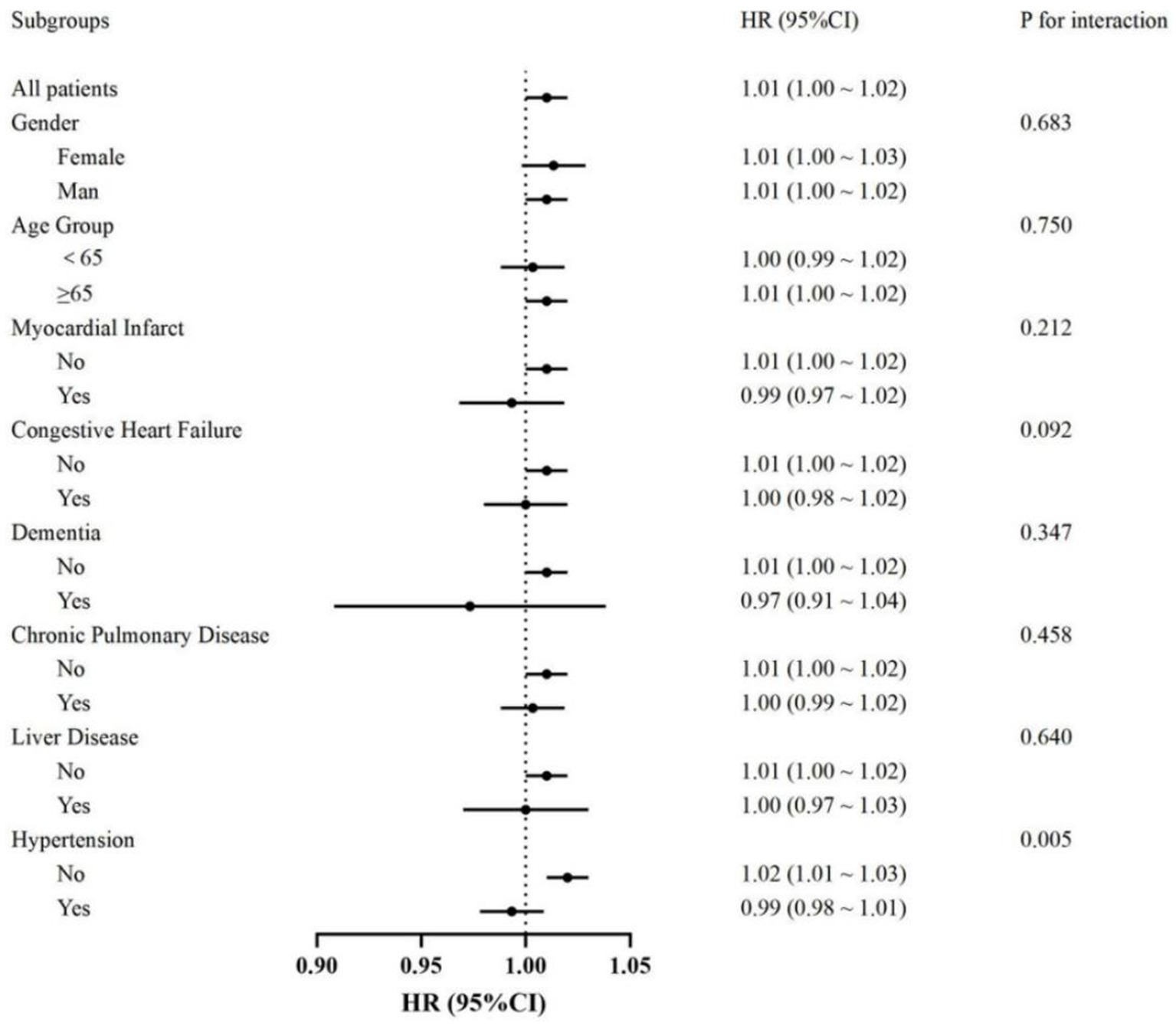

The association between heart rate and in-hospital mortality was evaluated across various subgroups, including gender, age, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, liver disease, and hypertension. Subgroup analyses demonstrated consistent associations between heart rate and mortality, with no significant interactions observed in most subgroups (all p for interaction >0.05). However, a significant interaction was identified in the hypertension subgroup (p for interaction = 0.005). Specifically, a significant association between heart rate and mortality was observed in patients without hypertension (HR: 1.02, 95% CI: 1.01–1.03), while no significant association was found in those with hypertension (HR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.98–1.01) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Forest plot showing hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between heart rate on the probability of 28-day survival in patients with cerebral infarction, with the dotted line indicating the null (HR = 1).

4 Discussion

Cerebral infarction is the most common type of stroke, characterized by a sudden interruption of blood flow to brain tissue, leading to neuronal damage. Clinical features include sudden weakness or numbness, typically on one side of the body, difficulty speaking or understanding speech, loss of vision in one or both eyes, dizziness, loss of balance, and unexplained severe headaches (16). Patients with large vessel occlusion tend to exhibit more pronounced infarct expansion during delayed treatment. Factors such as higher low perfusion intensity ratios and poorer collateral circulation are important predictors of this progression (17). Future efforts should focus on raising awareness, screening, and timely intervention to mitigate the impact of this debilitating disease.

When a cerebral infarction occurs, the blood supply to certain areas of the brain is interrupted, leading to hypoxia and neuronal death. The primary causes include embolic sources (such as atrial fibrillation), large artery atherosclerosis, and small vessel occlusion commonly associated with hypertension and diabetes (18, 19). From a pathophysiological perspective, cerebral infarction triggers a series of cascading events, including excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, inflammation, and blood–brain barrier disruption (20–22). Recent studies highlight the importance of biomarker identification to enhance early diagnosis and prognosis, with the aim of reducing the high mortality and disability rates associated with cerebral infarction (23).

This study found that higher heart rate was significantly associated with increased in-hospital mortality, with patients having heart rates >89.72 bpm showing significantly lower 28-day survival rates. Mortality risk increased when heart rate exceeded 78.78 bpm. Subgroup analysis indicated that heart rate was consistently associated with mortality in most subgroups, except for patients with hypertension, where no significant association was observed. Previous research has shown that patients with acute cerebral infarction who present with a higher initial heart rate at the time of hospitalization face a significantly greater risk of both all-cause mortality and cardiovascular death. This finding aligns with the results of our study, which highlights a strong association between heart rate indices and the prognosis of cerebral infarction patients. Therefore, monitoring and managing heart rate could play a crucial role in assessing prognosis and informing clinical decision-making (24, 25).

Heart rate plays a crucial role in predicting the prognosis of various diseases, particularly cardiovascular diseases and critical illnesses. An elevated resting heart rate is often associated with increased mortality and poor prognosis, especially in conditions such as heart failure and ischemic diseases (26). Advanced technologies, including interpretable machine learning models, have been developed to predict the prognosis of critically ill ICU patients by integrating heart rate with other physiological variables. For example, in ICU mortality prediction models, average heart rate, along with factors such as urine output and oxygen saturation, has been identified as a key predictive variable (27). In heart failure patients, improved heart rate control is associated with better recovery of ejection fraction and prognosis, highlighting its predictive significance in treatment outcomes (28) In addition, heart rate monitoring is being integrated into artificial intelligence and Internet of Things (IoT) platforms for continuous tracking, enabling real-time prognostic prediction and improving clinical decision-making in intensive care settings (26).

Heart rate significantly influences the prognosis of patients with cerebral infarction through various mechanisms. These abnormalities can exacerbate stroke-related complications. Autonomic dysregulation, characterized by excessive sympathetic nervous system activation and weakened parasympathetic modulation, is a key mediator in promoting pro-inflammatory states, endothelial dysfunction, and coagulopathy. For example, mechanisms that affect fibrosis and vascular remodeling, such as those involving SHARPIN protein, have been shown to impact stroke and cardiovascular outcomes. Reducing the expression of fibrosis-related proteins in cardiac tissue can alleviate stroke-related complications, highlighting the interplay between brain and heart health (29).

An elevated heart rate can impair the brain’s autoregulatory function by disrupting the balance between oxygen delivery and metabolic demand, thereby exacerbating ischemic damage in vulnerable brain areas. The mechanisms behind this phenomenon include increased oxidative stress, inflammation, and vascular dysfunction, which collectively lead to intensified neuronal injury. Research highlights that oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage are typically triggered by ischemia–reperfusion, playing a crucial role in disrupting autoregulatory mechanisms. For instance, inhibiting pathways such as JAK2/STAT3 and TLR9 can alleviate oxidative stress and improve prognosis by maintaining vascular stability (30). In addition, increased sympathetic nervous activity (often reflected in higher heart rates) may exacerbate ischemic damage by enhancing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and altering cerebral blood flow regulation. Therapies targeting inflammation and mitochondrial pathways, such as nicotinamide and ischemic preconditioning, have shown promise in restoring autonomic regulation and reducing ischemic injury (31). Monitoring and managing heart rate dynamics, including through pharmacological or non-invasive interventions such as heart rate variability biofeedback, can provide therapeutic benefits in stroke care, improving overall survival and functional recover. One study investigated the relationship between heart rate variability (HRV), neurological function, and clinical factors with mortality and behavioral functional outcomes in patients with ischemic stroke. The results suggest that HRV may be associated with 3-month behavioral functional outcomes (32).

Non-cardioembolic ischemic stroke is primarily caused by large artery atherosclerosis and small vessel occlusion, accounting for 70 to 85% of all ischemic strokes. We excluded patients with atrial fibrillation to specifically study the non-cardioembolic ischemic stroke population. Atrial fibrillation is a major cause of cardioembolic stroke and follows a distinct pathophysiological mechanism. The treatment strategies for cardioembolic and non-cardioembolic strokes differ significantly. Including atrial fibrillation patients in a study on ischemic stroke prognosis could introduce confounding bias due to differences in treatment approaches, thereby compromising the reliability of the study’s conclusions. Moreover, the relationship between heart rate and stroke prognosis differs in patients with atrial fibrillation. Atrial fibrillation patients exhibit greater heart rate variability, and the condition itself can lead to hemodynamic instability (33). Excluding patients with atrial fibrillation ensures greater homogeneity in the study population, making the research conclusions more specific and clinically relevant.

Studies have found that hypertension is one of the most significant risk factors for ischemic stroke (34). Hypertension significantly affects cerebral blood flow autoregulation and can lead to post-stroke hypoperfusion, inflammation, and cognitive impairment through mechanisms such as vascular smooth muscle dysfunction, blood–brain barrier disruption, and capillary rarefaction (35). Our study demonstrates that blood pressure significantly influences the relationship between heart rate and prognosis. In patients without hypertension, an elevated heart rate is significantly associated with worse outcomes in non-cardioembolic ischemic stroke. Based on clinical observations and previous research, we hypothesize that β-blockers or calcium channel blockers, which are frequently used by hypertensive patients, may reduce heart rate, thereby mitigating the adverse effects of heart rate elevation. Additionally, hypertension may lead to arterial stiffness and decreased vascular compliance, reducing the impact of heart rate on cerebral blood flow regulation. In contrast, non-hypertensive individuals may rely more on heart rate to maintain hemodynamic stability, making them more vulnerable to the detrimental effects of an elevated heart rate. Therefore, in ischemic stroke patients without hypertension, closer heart rate monitoring and potential heart rate control interventions should be considered to improve stroke prognosis.

This study used the MIMIC-IV database, which provides a large and diverse dataset that enables reliable analysis of clinical factors and prognosis in patients with cerebral infarction. However, it is important to recognize that the database has some inherent limitations. First, as a retrospective cohort study, the results are subject to inherent biases such as selection bias and unmeasured confounders. Although statistical adjustments have been made to minimize these biases, residual confounders cannot be completely excluded. Second, the MIMIC-IV database represents data from a single healthcare system, which may limit the generalizability of study results to other populations or healthcare settings. Differences in clinical practice, resource availability, and patient demographics may affect the external validity of study results. Third, the database lacks detailed neuroimaging data, such as CT or MRI findings, which are critical to accurately assess stroke severity, infarct size, and lesion location. The lack of these imaging parameters limits the ability to comprehensively assess the relationship between clinical variables and stroke prognosis. Finally, despite our efforts to address the problem of missing data through multiple interpolation methods, the presence of incomplete records and the potential bias introduced by estimation techniques remains a concern.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study reveals a positive association between elevated heart rate and in-hospital mortality in patients with cerebral infarction without atrial fibrillation. Patients with heart rates greater than 90 bpm had significantly reduced 28-day survival, and this association remained consistent across most subgroups except for hypertensive patients. These findings suggest that heart rate may serve as an independent prognostic indicator of mortality in cerebral infarction patients. If further validated, this association could provide a rationale for developing therapeutic strategies targeting heart rate to improve clinical prognosis in this population.

Data availability statement

This study analyzed publicly available datasets, accessible at: https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/2.0/.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Centre under approval number 2001P-001699/14. Written informed consent from the patients or patients legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

XS: Data curation, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft. LZ: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China funded projects (82174477).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Feigin, VL, Stark, BA, Johnson, CO, Roth, GA, Bisignano, C, Abady, GG, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Neurol. (2021) 20:795–820. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00252-0

2. Sposato, LA, Hilz, MJ, Aspberg, S, Murthy, SB, Bahit, MC, Hsieh, C-Y, et al. Post-stroke cardiovascular complications and neurogenic cardiac injury: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 76:2768–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.10.009

3. Bo, W, Li, X, Tao, S, Lei, M, Peng-Fei, Y, and Tuan-Jie, L. Prognostic factor analysis and prognostic model establishment for young and middle-aged patients with cerebral infarction. Acad J Second Mil Univ. (2021) 42:1132–9. doi: 10.16781/j.0258-879x.2021.10.1132

4. Lili, HE, Pengzhen, MA, Yingzhen, XIE, Wenying, S, Jinxiao, GU, Qiuyue, W, et al. Influencing factors and survival analysis of poor prognosis in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Modern J Integrated Tradit Chinese Western Med. (2023) 32:2221–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-8849.2023.16.006

5. Enciu, E, Stanciu, S, Matei, D, and Roul, G. Autonomic nervous system dysfunction and abnormal heart rate recovery. Arch Cardiovasc Dis Suppl. (2018) 10:116. doi: 10.1016/j.acvdsp.2017.11.198

6. Hadad, R, Haugaard, SB, Christensen, PB, Sarac, A, Dominguez, MH, and Sajadieh, A. Autonomic nerve function predicts risk of early death after discharge in acute medical disease. Am J Med. (2024) 137:649–657.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.02.033

7. Candemir, M, and Onder, H. Assessing autonomic nervous function by heart rate variability and heart rate turbulence in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Ann Indian Acad Neur. (2020) 23:608–15. doi: 10.4103/aian.AIAN_647_19

8. Buchman, TG, Stein, PK, and Goldstein, B. Heart rate variability in critical illness and critical care. Curr Opin Crit Care. (2002) 8:311–5. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200208000-00007

9. Wang, L, Ma, L, Ren, C, Zhao, W, Ji, X, Liu, Z, et al. Stroke–heart syndrome: current progress and future outlook. J Neurol. (2024) 271:4813–25. doi: 10.1007/s00415-024-12480-4

10. Orgianelis, I, Merkouris, E, Kitmeridou, S, Tsiptsios, D, Karatzetzou, S, Sousanidou, A, et al. Exploring the utility of autonomic nervous system evaluation for stroke prognosis. Neurol Int. (2023) 15:661–96. doi: 10.3390/neurolint15020042

11. Jeong, H-G, Ko, S-B, Kim, CK, Kim, Y, Jung, S, Kim, TJ, et al. Tachycardia burden in stroke unit is associated with functional outcome after ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke. (2016) 11:313–20. doi: 10.1177/1747493016631357

12. Nakicevic, A, Alajbegovic, S, and Alajbegovic, L. Tachycardia as a negative prognostic factor for stroke outcome. Mater Socio Med. (2017) 29:40–4. doi: 10.5455/msm.2017.29.40-44

13. Ritter, MA, Rohde, A, Heuschmann, PU, Dziewas, R, Stypmann, J, Nabavi, DG, et al. Heart rate monitoring on the stroke unit. What does heart beat tell about prognosis? An observational study. BMC Neurol. (2011) 11:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-47

14. Yao, S, Chen, X, Liu, J, Chen, X, and Zhou, Y. Effect of mean heart rate on 30-day mortality in ischemic stroke with atrial fibrillation: data from the MIMIC-IV database. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:1017849. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1017849

15. Johnson, AEW, Bulgarelli, L, Shen, L, Gayles, A, Shammout, A, Horng, S, et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci Data. (2023) 10:1. doi: 10.1038/s41597-022-01899-x

16. Zhao, Y, Zhang, X, Chen, X, and Wei, Y. Neuronal injuries in cerebral infarction and ischemic stroke: from mechanisms to treatment (review). Int J Mol Med. (2021) 49:15. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2021.5070

17. Wouters, A, Seners, P, Yuen, N, Mlynash, M, Heit, JJ, Kemp, S, et al. Clinical and imaging features associated with fast infarct growth during Interhospital transfers of patients with large vessel occlusions. Neurology. (2024) 103:e209814. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000209814

18. Hainsworth, AH, Markus, HS, and Schneider, JA. Cerebral small vessel disease, hypertension, and vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia. Hypertension. (2024) 81:75–86. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.123.19943

19. Ntaios, G, Milionis, H, Vemmos, K, Makaritsis, K, Ferrari, J, Strbian, D, et al. Small-vessel occlusion versus large-artery atherosclerotic strokes in diabetics: patient characteristics, outcomes, and predictors of stroke mechanism. Eur Stroke J. (2016) 1:108–13. doi: 10.1177/2396987316647856

20. Yang, C, Hawkins, KE, Doré, S, and Candelario-Jalil, E. Neuroinflammatory mechanisms of blood-brain barrier damage in ischemic stroke. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. (2019) 316:C135–53. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00136.2018

21. Song, K, Li, Y, Zhang, H, An, N, Wei, Y, Wang, L, et al. Oxidative stress-mediated blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption in neurological diseases. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. (2020) 2020:1–27. doi: 10.1155/2020/4356386

22. Yang, Q, Huang, Q, Hu, Z, and Tang, X. Potential neuroprotective treatment of stroke: targeting excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Front Neurosci. (2019) 13:1036. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01036

23. Guo, Y, Li, P, Guo, Q, Shang, K, Yan, D, Du, S, et al. Pathophysiology and biomarkers in acute ischemic stroke – a review. Trop J Pharm Res. (2014) 12:1097. doi: 10.4314/tjpr.v12i6.35

24. Lee, J-D, Kuo, Y-W, Lee, C-P, Huang, Y-C, Lee, M, and Lee, T-H. Initial in-hospital heart rate is associated with long-term survival in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Clin Res Cardiol. (2022) 111:651–62. doi: 10.1007/s00392-021-01953-5

25. Erdur, H, Scheitz, JF, Grittner, U, Laufs, U, Endres, M, and Nolte, CH. Heart rate on admission independently predicts in-hospital mortality in acute ischemic stroke patients. Int J Cardiol. (2014) 176:206–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.07.001

26. Talaat, FM, Elnaggar, AR, Shaban, WM, Shehata, M, and Elhosseini, M. Cardio risk net: a hybrid AI-based model for explainable risk prediction and prognosis in cardiovascular disease. Bioengineering. (2024) 11:822. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering11080822

27. Bu, Z-J, Jiang, N, Li, K-C, Lu, Z-L, Zhang, N, Yan, S-S, et al. Development and validation of an interpretable machine learning model for early prognosis prediction in ICU patients with malignant tumors and hyperkalemia. Medicine. (2024) 103:e38747. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000038747

28. Gotsman, I, Zwas, DR, Keren, A, Amir, O, and Leibowitz, D. Beyond the initial insult: clinical characteristics and prognosis of heart failure with improved ejection fraction. Cardiology. (2024) 26:1–8. doi: 10.1159/000540597

29. Zhai, C, Zhao, Y, Zhang, Z, Wang, X, Li, L, and Li, J. Mechanism of multifunctional adaptor protein SHARPIN regulating myocardial fibrosis and how SNP mutation affect the prognosis of myocardial infarction. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Mol Basis Dis. (2024) 1870:167467. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2024.167467

30. Zhang, M, Zhang, Y, Peng, J, Huang, Y, Gong, Z, Lu, H, et al. Gastrodin against oxidative stress-inflammation crosstalk via inhibiting mt DNA/TLR9 and JAK2/STAT3 signaling to ameliorate ischemic stroke injury. Int Immunopharmacol. (2024) 141:113012. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2024.113012

31. Arslan, R, Doganay, S, Budak, O, and Bahtiyar, N. Investigation of preconditioning and the protective effects of nicotinamide against cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Neurosci Lett. (2024) 840:137949. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2024.137949

32. Wu, M-J, Dewi, SRK, Hsu, W-T, Hsu, T-Y, Liao, S-F, Chan, L, et al. Exploring relationships of heart rate variability, neurological function, and clinical factors with mortality and behavioral functional outcome in patients with ischemic stroke. Diagnostics. (2024) 14:1304. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics14121304

33. Khan, AA, Junejo, RT, Thomas, GN, Fisher, JP, and Lip, GYH. Heart rate variability in patients with atrial fibrillation and hypertension. Eur J Clin Investig. (2021) 51:e13361. doi: 10.1111/eci.13361

34. O’Donnell, MJ, Xavier, D, Liu, L, Zhang, H, Chin, SL, Rao-Melacini, P, et al. Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): a case-control study. Lancet. (2010) 376:112–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60834-3

35. Shekhar, S, Liu, R, Travis, OK, Roman, RJ, and Fan, F. Cerebral autoregulation in hypertension and ischemic stroke: A mini review. J Pharm Sci Exp Pharmacol. (2017) 2017:21–7.

Keywords: MIMIC-IV database, cerebral infarction, heart rate, prognosis, predictive modeling

Citation: Song X and Zhu L (2025) Predictive value of heart rate for prognosis in patients with cerebral infarction without atrial fibrillation comorbidity analyzed according to the MIMIC-IV database. Front. Neurol. 16:1551427. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2025.1551427

Edited by:

Michael L. James, Duke University, United StatesReviewed by:

Tijana Nastasovic, University of Belgrade, SerbiaOladi Bentho, University of Minnesota Medical Center, United States

Copyright © 2025 Song and Zhu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Luwen Zhu, zhuluwen1983@126.com

Xinrou Song

Xinrou Song