- Department of Neurology and Stroke Center, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi’an, Shaanxi, China

Objectives: We explored the relationship between blood pressure variability (BPV) during craniotomy aneurysm clipping and short-term prognosis in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage to provide a new method to improve prognosis of these patients.

Methods: We retrospectively analyzed the differences between patient groups with favorable modified Rankin Scale (mRS ≤ 2) and unfavorable (mRS > 2) prognosis, and examined the association between intraoperative BPV and short-term prognosis.

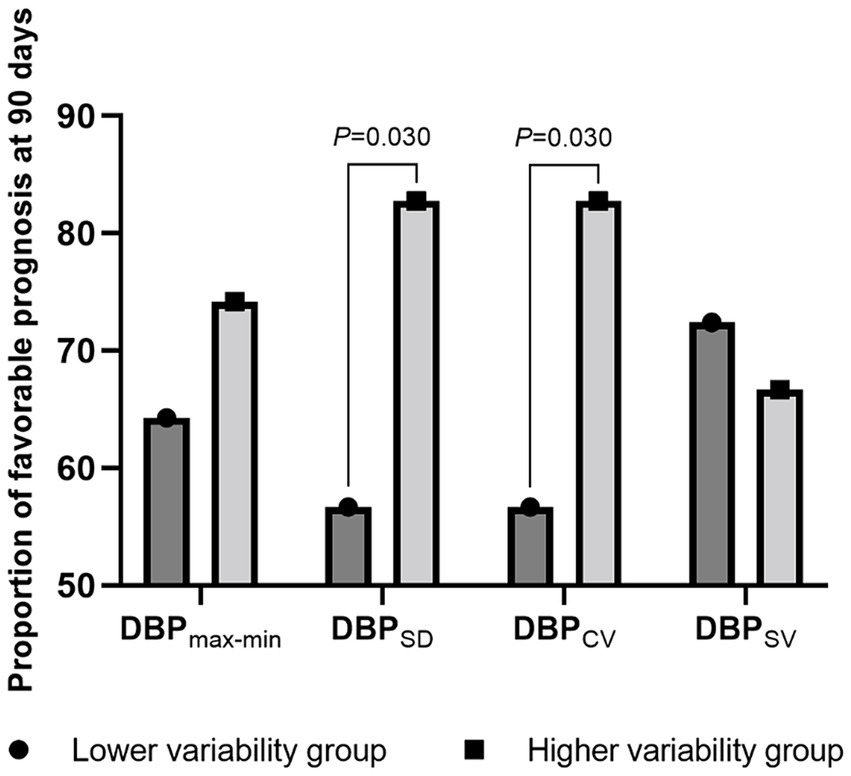

Results: The intraoperative maximum systolic blood pressure (SBPmax, p = 0.005) and the coefficient of variation of diastolic blood pressure (DBPCV, p = 0.029) were significantly higher in the favorable prognosis group. SBPmax (OR 0.88, 95%CI 0.80–0.98) and Neu% (OR 1.22, 95%CI 1.03–1.46) were independent influence factors on prognosis. Patients with higher standard deviations of SBP (82.7% vs. 56.7%; p = 0.030), DBP (82.7% vs. 56.7%; p = 0.030), and DBPCV (82.7% vs. 56.7%; p = 0.030) had more favorable prognosis.

Conclusion: Higher SBPmax (≤180 mmHg) during the clipping is an independent protective factor for a 90-day prognosis. These results highlight the importance of blood pressure (BP) control for improved prognosis; higher short-term BPV during clipping may be a precondition for a favorable prognosis.

Introduction

Spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is the third most common type of stroke and is commonly associated with aneurysmal rupture (1). Globally, approximately 500,000 patients develop aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH) annually (2). Approximately a quarter of patients with SAH die before hospital admission; overall outcomes are improved in those admitted to hospitals; however, these survivors face years with a diminished quality of life (3). Age, hypertension, intraoperative and postoperative complications, surgical timing, and surgical methods are significant factors affecting the prognosis of aSAH (4). Conversely, the effect of blood pressure fluctuations on the prognosis of aSAH remains uncertain (5–7). Previous studies on blood pressure variability (BPV) have ignored the impact of surgical approaches and intraoperative blood pressure fluctuations on the prognosis of patients with aSAH. Consequently, the present study sought to examine the association between intraoperative BPV and 90-day prognosis in patients with aSAH who underwent craniotomy aneurysm clipping.

Methods

Study population

A total of 59 patients with aSAH were included in this retrospective study. All the patients underwent craniotomy aneurysm clipping at the Department of Neurosurgery of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University between January 2019 and December 2022. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age 18–80 years; (2) spontaneous primary aSAH confirmed by CT scan and digital subtraction angiography (DSA); (3) admission within 72 h after symptom onset and aneurysm clipping within 36 h after admission; and (5) complete medical records. Patients with severe craniocerebral trauma, modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores before onset exceeding 2, or hemodynamic instability were excluded. This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University (No. XJTU1AF2023LSK-265). Written informed consent from the legal guardians of the participants was not required for this retrospective study in accordance with national and local guidelines.

Clinical management

All patients underwent emergency clipping of ruptured intracranial aneurysms under general anesthesia with tracheal intubation. Blood pressure (BP) of patients obtained by invasive arterial pressure monitoring (patient monitor model: BeneView T8) through radial artery catheterization was recorded every 15 min from entering to leaving the operating room. Patients were transferred to the intensive care unit, and nimodipine was routinely administered to prevent cerebral vasospasm after surgery. Treatment was administered in strict accordance with the relevant clinical management guidelines.

Data collection

The general data of patients were recorded as follows: (1) demographic characteristics (age and sex); (2) medical comorbidities (hypertension and diabetes); (3) personal history (smoking and drinking); (4) characteristics of the aneurysm (location, size, and number); (5) assessment of severity at admission [Glasgow Coma Scale, Hunt-Hess Scale, modified Fisher grade (m-Fisher), and World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (WFNS) score]; and (6) laboratory results at admission [hemoglobin, white blood cell, platelet, neutrophil percentage (Neu%), aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, cholesterol, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, and random blood glucose].

We calculated the following indexes of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (8, 9): The mean, maximum (max), minimum (min), difference of maximum minus minimum (max–min), standard deviation (SD, SD= ), coefficient of variation (CV, CV = (XSD/Xmean) *100%) and successive variation (SV, SV= ).

Evaluation of prognosis

The prognosis was evaluated using the mRS at 90 days after onset. All patients were followed up by the same neurologist through telephone interviews. The mRS is a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (death). The mRS was dichotomized, as previously published, into favorable (mRS ≤ 2) and unfavorable (mRS > 2) prognoses for the outcome analyses (10).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS25.0 statistical package. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation ( ± s) for continuous symmetric distribution variables, median (M) and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous skewed distribution variables, and percentages for categorical variables. Differences between the two groups were assessed using univariate analysis with independent Student’s t-tests for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables. For non-parametric variables, we used the Mann–Whitney U-test. The significant parameters in the univariate analysis were used as inputs in the multivariate binary logistic regression model for regression analysis. Spearman’s rank correlation was used for correlation analysis. In all the tests, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

Data were recorded and stored in both paper and electronic databases. The supporting data for this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Results

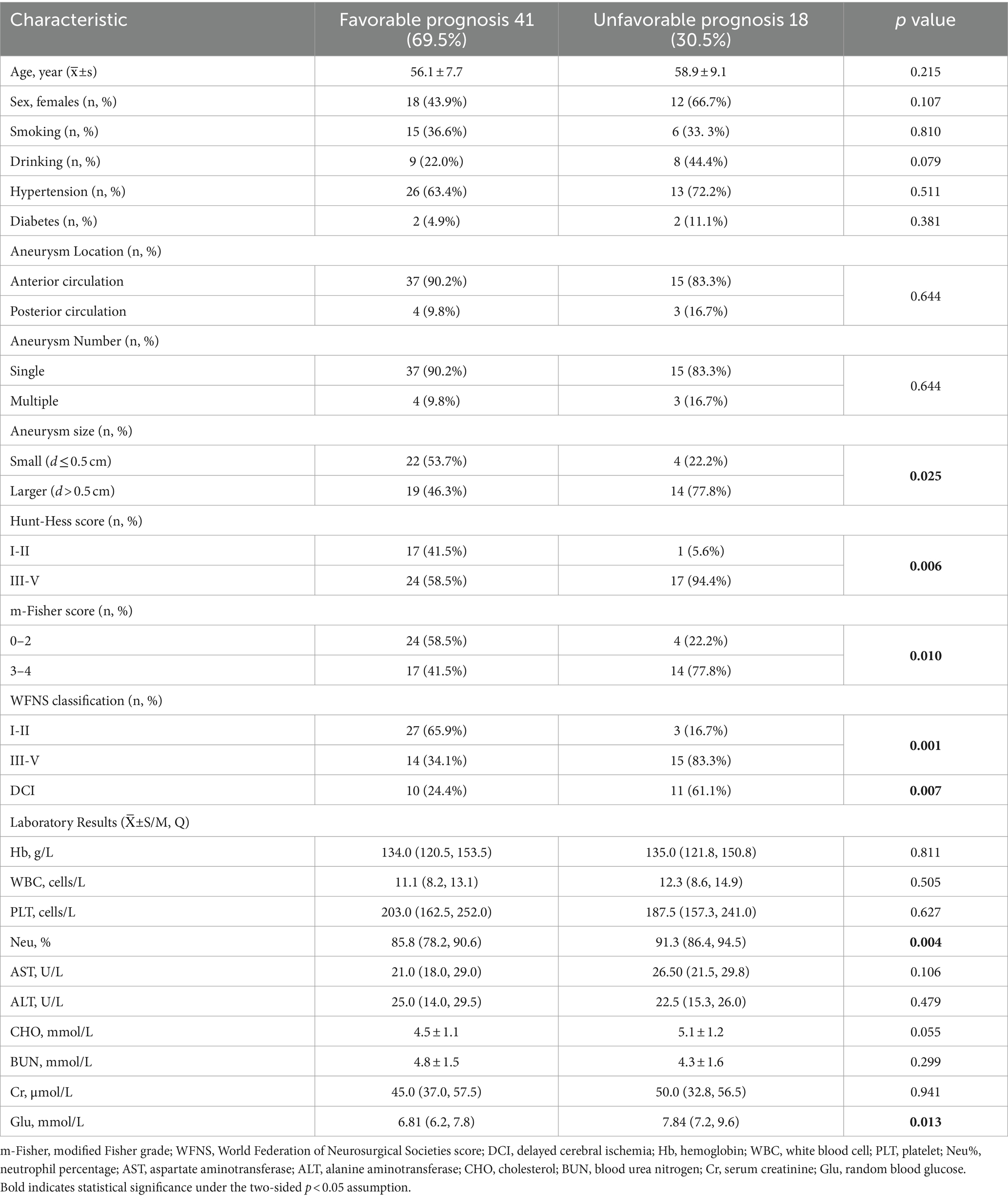

Fifty-nine eligible patients were enrolled over the four-year interval, of whom 29 (49%) were male, and 30 (51%) were female. The average age was 57.0 ± 8.2 years. The clinical data of the 59 patients (41 in the favorable group and 18 in the unfavorable group) are summarized in Table 1. The aneurysm size (p = 0.025), Hunt–Hess grade (p = 0.006), m-Fisher grade (p = 0.010), WFNS grade (p = 0.001), Neu% (p = 0.004), and blood Glu (p = 0.013) at admission and the incidence of delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI, p = 0.007) were significantly higher in the unfavorable group (mRS > 2) than in the favorable group (mRS ≤ 2). The two groups showed no significant differences in the remaining clinical data.

Table 1. Comparison of clinical characteristics between patient groups with favorable and unfavorable prognosis.

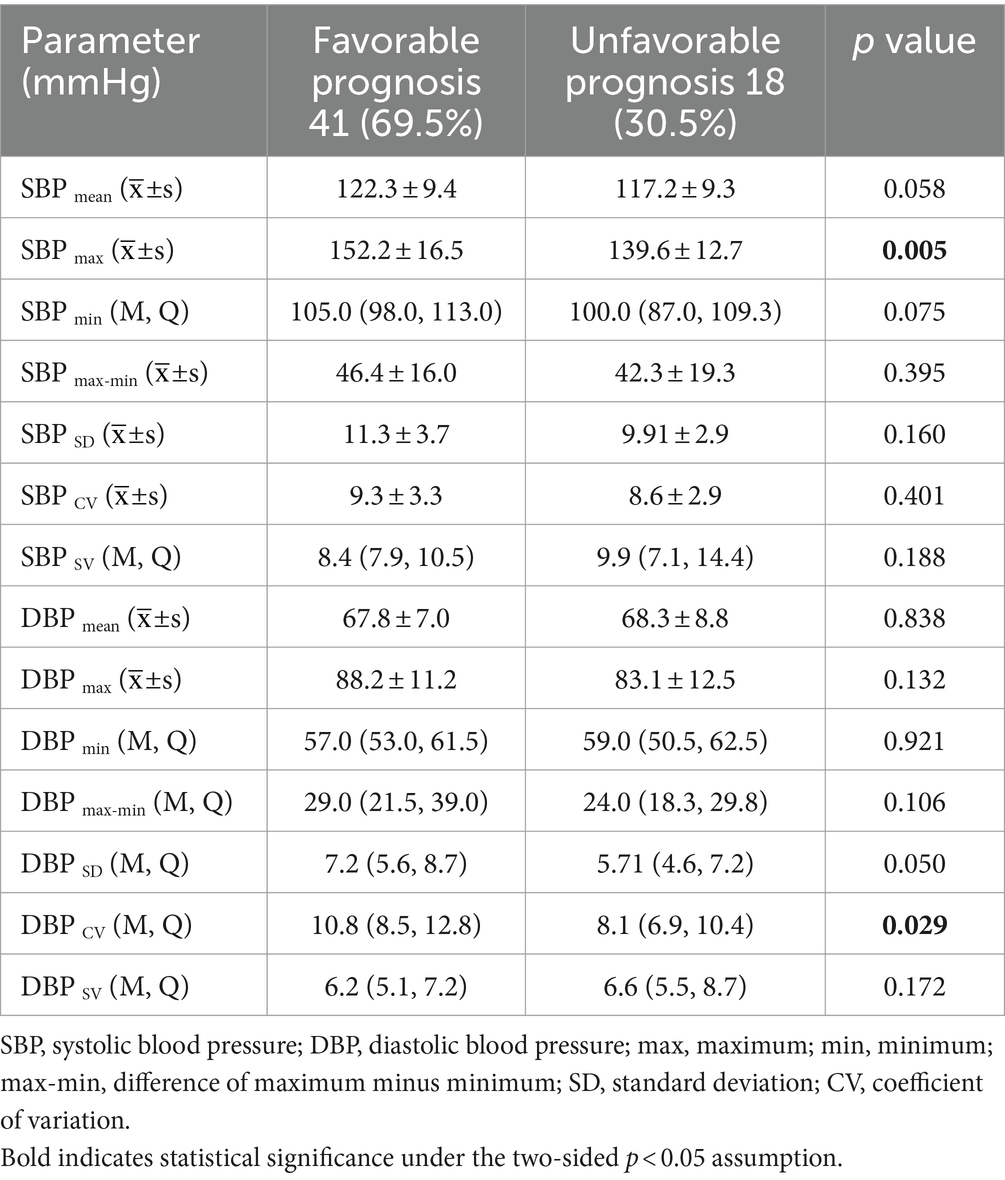

A comparison of the intraoperative SBP and DBP indices between the two groups is shown in Table 2. The SBPmax (152.2 ± 16.5 vs. 139.6 ± 12.7; p = 0.005) and DBPcv (10.8, IQR 8.5–12.8; 8.1, IQR 6.9–10.4; p = 0.029) were significantly higher in the favorable group than in the unfavorable group. Spearman’s correlation tests showed that intraoperative SBPmax (r = 0.34, p = 0.015) and DBPcv (r = 0.29, p = 0.027) were positively associated with a 90-day favorable prognosis.

Table 2. Comparison of intraoperative blood pressure parameters between patient groups with favorable and unfavorable prognosis.

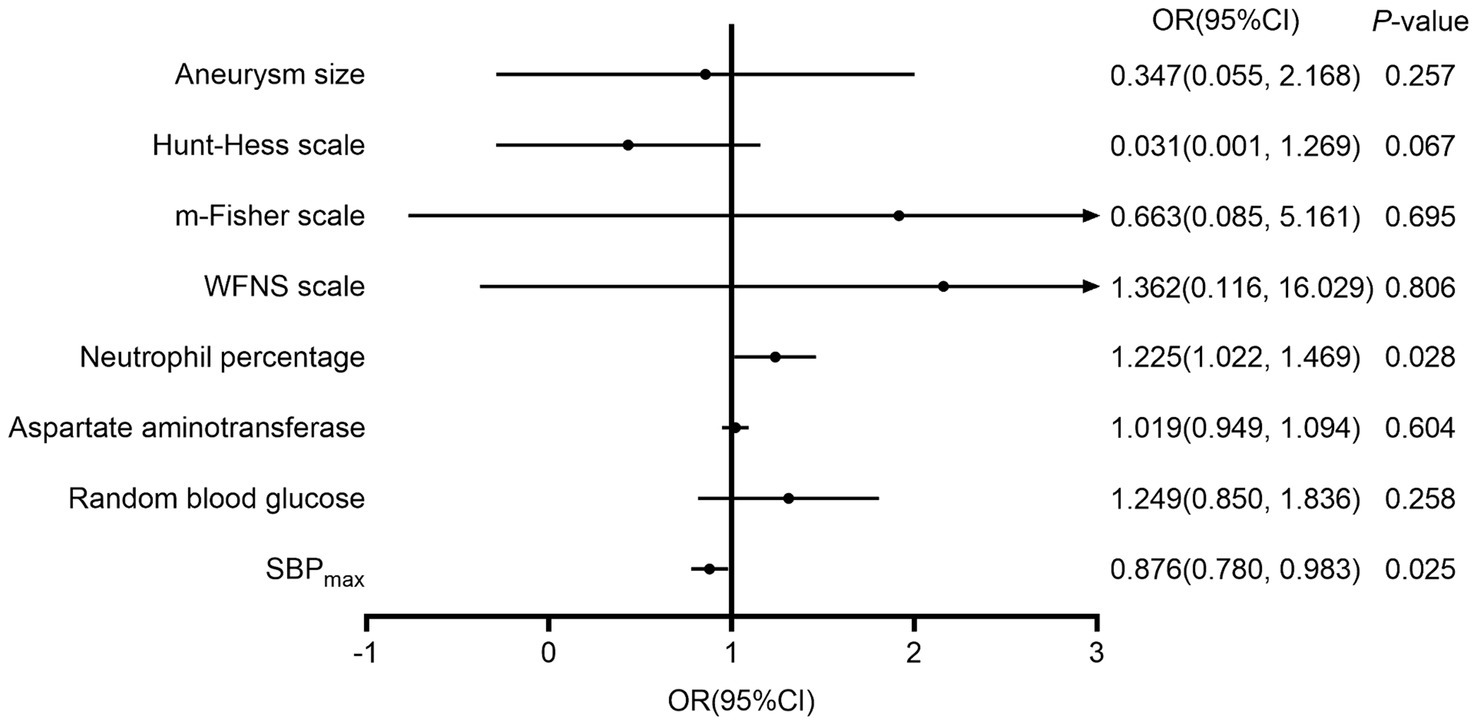

Indices with statistical differences in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate binary logistic regression analysis. This analysis showed that Neu% (OR 1.22, 95%CI 1.03–1.46) is an independent risk factor for unfavorable prognosis, while SBPmax (OR 0.88, 95%CI 0.80–0.98) is an independent protective factor for prognosis. Figure 1 shows the factors that significantly influenced the 90-day prognosis of patients with aSAH. In addition, we stratified the 47 patients with systolic BP ≤180 mmHg and the 56 patients with ≤160 mmHg, according to the 95th and 90th percentiles, respectively. The results showed that when the SBPmax was ≤180 mmHg, the probability of developing a favorable prognosis at 90 days increased with increasing SBPmax (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.01–1.11; p = 0.018). However, the trend was not statistically significant when the cutoff value was 160 mmHg (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.98–1.10; p = 0.212).

Figure 1. The influencing factors on the 90-day prognosis of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. m-Fisher, modified Fisher grade; WFNS, World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies score; SBPmax, maximum systolic blood pressure; DBPCV, coefficient of variation of the diastolic blood pressure.

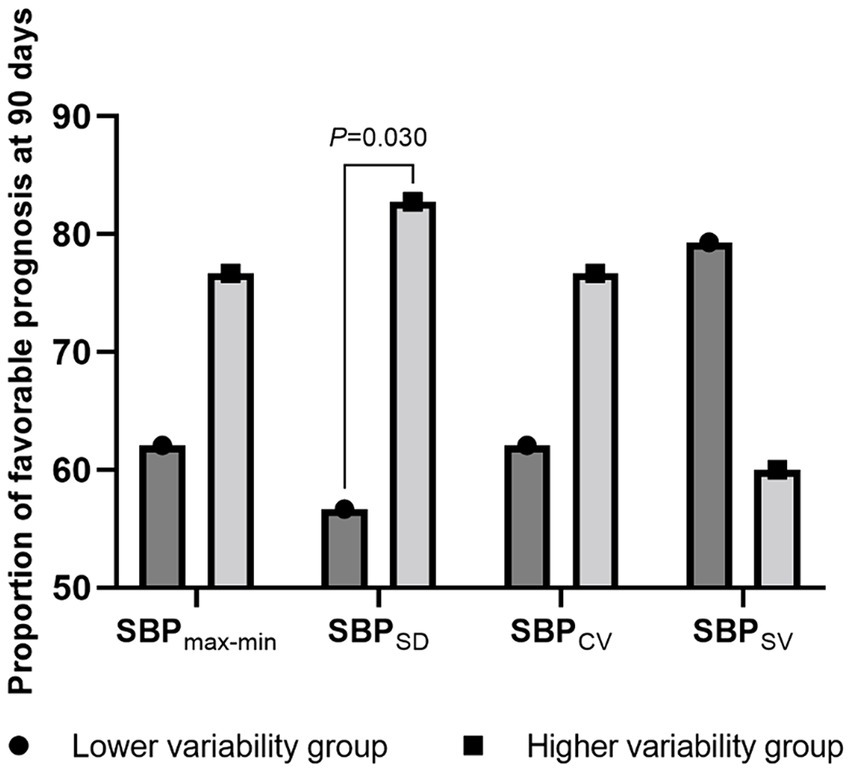

Next, we stratified the patients into two groups based on the median BP variability parameters and compared their proportions of favorable prognoses. Patients with a higher SBPSD (56.7% vs. 82.7%; p = 0.030), DBPSD (56.7% vs. 82.7%; p = 0.030), and DBPCV (56.7% vs. 82.7%; p = 0.030) had a more favorable prognosis. Detailed data are presented in Figures 2, 3.

Figure 2. The proportion of favorable prognosis at 90 days for patient groups with lower and higher systolic blood pressure variability. SBP, systolic blood pressure; max-min, difference of maximum minus minimum; SD, standard deviation; CV, coefficient of variation; SV, successive variation.

Figure 3. The proportion of favorable prognosis at 90 days for patient groups with lower and higher diastolic blood pressure variability during surgery. DBP, diastolic blood pressure; max-min, difference of maximum minus minimum; SD, standard deviation; CV, coefficient of variation; SV, successive variation.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that intraoperative SBPmax is an independent predictor of favorable outcomes in patients with aSAH. Acute hypertension should be managed after developing aSAH; however, the parameters for appropriate BP control have not yet been defined. Insufficient management of BP may increase the risk of rebleeding, whereas aggressive treatment of hypertension increases the risk of ischemic stroke (11). It has been confirmed that induced hypertension can reduce the occurrence of DCI; however, unsurprisingly, having an SBPmax > 180 mmHg increases the risk of rebleeding (12, 13). In 2012, the AHA/ASA issued guidelines for SAH treatments, pointing out that maintaining euvolemia and inducing hypertension are effective measures to prevent DCI and recommended that SBP should be brought below 160 mmHg before clipping the aneurysm to reduce the risk of rebleeding (14). In 2013, the European Stroke Organization suggested that SBP should be maintained below 180 mmHg before surgery (13). In a previous study, Ascanio et al. reported that hypotension was independently associated with poor outcomes in patients with aSAH (15). Similarly, the present study showed that intraoperative SBPmax was an independent protective factor for patients with aSAH when it was below 180 mmHg. However, no protective effect was observed when SBPmax was <160 mmHg. These results led us to propose that the intraoperative SBPmax should be elevated but not exceed 180 mmHg, which is consistent with the management of preoperative hypertension proposed by the European Stroke Organization in 2013 (13). In addition, intraoperative hypotension appears to promote DCI and poor prognosis in patients with aSAH; however, the downline of intraoperative blood pressure control is inconsistent (16–19).

The unfavorable prognosis of patients with aSAH is often related to DCI, which is generally attributed to abnormal constriction of the cerebral arteries, namely, cerebral vasospasm (CVS) (20). DCI is associated with the autoregulatory failure of the nervous system (21). Furthermore, intracranial pressure variability (ICPV) is mainly affected by fluctuations in cerebral blood flow, which indirectly reflects cerebral autoregulation (22). Previous studies have shown that low BPV and ICPV are associated with unfavorable outcomes in patients with aSAH (7). The present results show that patients with higher BP variability have a higher incidence of favorable prognoses. In 1929, Walter B. Cannon first proposed the concept of “homeostasis.” According to self-regulation mechanisms, physiological homeostasis is not static but maintains a dynamic equilibrium within a tolerable range. Physiological variability reflects the ability of an organism to autoregulate. Abnormal variability, reflecting impaired physiological responsiveness, can increase the risk of further physiological derangement (23). DBP is mainly affected by the heart rate and peripheral resistance. After SAH, the concentration of calcium ions in the cerebrospinal fluid increases, and the flow of calcium ions into the cells accelerates, resulting in vasoconstriction and increased vascular resistance. A lower DBPCV in patients with aSAH implies distal microvascular spasms, indicating an increased risk of CVS or even DCI, which is closely related to unfavorable prognoses. However, other studies have shown that variability in SBP within 24 h of admission is an independent risk factor for poor prognosis in patients with SAH (6). These propositions were not entirely consistent, possibly owing to inconsistencies arising from the different timeframes considered in the variability assessment. Higher short-term variability may reflect faster and more effective functioning of adaptive mechanisms, and higher long-term variability (time spans exceeding 1 h) may reflect a decreased integrated ability of adaptive mechanisms to respond to challenges (7). Therefore, the timescale of BP variability determines its effect on clinical outcomes.

Previous studies have shown that BP variability is related to the vegetative nervous system function, such that decreased variability implies autonomic nerve dysfunction (24, 25). If the sympathetic nervous system is overactivated, feedback regulation of the neuroendocrine system may fail, leading to decreased short-term variability and an increased risk of unfavorable prognoses (26). Supporting this model, pharmacological blocking of the cervical sympathetic ganglion can effectively relieve DCI after SAH (27), which has also been confirmed in animal experiments (28). As mentioned above, timely and effective inhibition of sympathetic hyperactivity may benefit patients with aSAH, offering a new therapeutic target to reduce the incidence of CVS and improve prognosis.

The small sample size used during this study may have reduced the generalizability of the results; however, the overall trend was compelling. The mean duration of intracranial aneurysm clipping among the enrolled patients was only 5.4 h, so we could not analyze longer-term BPV. Furthermore, not all BP values were available during the entire hospital stay. Therefore, we cannot discuss the prognostic effects of BPV during hospitalization. We did not fully consider the influence of intraoperative drugs on BPV, which may have affected the accuracy of the research findings and should, therefore, be considered in future-related studies. We intend to conduct further clinical studies to evaluate whether patients benefit from intraoperative interventions for arterial pressure reduction.

In conclusion, SBPmax during craniotomy aneurysm clipping was an independent protective factor for a favorable prognosis at 90 days. Appropriately high BP is beneficial for improving prognosis. However, the risk of adverse effects such as rebleeding should be considered. A higher short-term BPV during surgery implies higher cerebral autoregulatory function, potentially leading to a more favorable prognosis.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Author contributions

XH: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. GL: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration. JL: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Investigation. RL: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. NZ: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. SJ: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. WM: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. YC: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. FL: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by grants from the Clinical Research Center of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University (No. 2021ZYTS-03), the Key Research and Development Plan of Shaanxi Province (No. 2021SF-059), and the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi Province (No. 2023-JC-QN-0893).

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the participants and collaborators of the study team for their tremendous support throughout the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Feigin, VL, Lawes, CM, Bennett, DA, Barker-Collo, SL, and Parag, V. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. (2009) 8:355–69. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70025-0

2. Hughes, JD, Bond, KM, Mekary, RA, Dewan, MC, Rattani, A, Baticulon, R, et al. Estimating the global incidence of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review for central nervous system vascular lesions and meta-analysis of ruptured aneurysms. World Neurosurg. (2018) 115:430–447.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.03.220

3. Claassen, J, and Park, S. Spontaneous subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet. (2022) 400:846–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00938-2

4. Ge, XB, Yang, QF, Liu, ZB, Zhang, T, and Liang, C. Increased blood pressure variability predicts poor outcomes from endovascular treatment for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. (2021) 79:759–65. doi: 10.1590/0004-282x-anp-2020-0167

5. Chung, P-W, Kim, J-T, Sanossian, N, Starkmann, S, Hamilton, S, Gornbein, J, et al. Association between hyperacute stage blood pressure variability and outcome in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. (2018) 49:348–54. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017701

6. Yang, M, Pan, X, Liang, Z, Huang, X, Duan, M, Cai, H, et al. Association between blood pressure variability and the short-term outcome in patients with acute spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. Hypertens Res. (2019) 42:1701–7. doi: 10.1038/s41440-019-0274-y

7. Kirkness, CJ, Burr, RL, and Mitchell, PH. Intracranial and blood pressure variability and long-term outcome after aneurysmal sub-arachnoid hemorrhage. Am J Crit Care. (2009) 18:241–51. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009743

8. Rothwell, PM, Howard, SC, Dolan, E, O'Brien, E, Dobson, JE, Dahlöf, B, et al. Prognostic significance of visit-to-visit variability, maximum systolic blood pressure, and episodic hypertension. Lancet. (2010) 375:895–905. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60308-X

9. Schachinger, H, Langewitz, W, Schmieder, RE, and Ruddel, H. Comparison of paramaters for assessing blood-pressure and heart-rate variability from non-invasive 24-hour blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. (1989) 7:S81–4.

10. Berkhemer, OA, Fransen, PSS, Beumer, D, Van Den Berg, LA, Lingsma, HF, Yoo, AJ, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. (2015) 372:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411587

11. Wijdicks, EFM, Vermeulen, M, Murray, GD, Hijdra, A, and Vangijn, J. The effects of treating hypertension following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. (1990) 92:111–7. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(90)90085-J

12. Haegens, NM, Gathier, CS, Horn, J, Coert, BA, Verbaan, D, and Van Den Bergh, WM. Induced hypertension in preventing cerebral infarction in delayed cerebral ischemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. (2018) 49:2630–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.022310

13. Steiner, T, Juvela, S, Unterberg, A, Jung, C, Forsting, M, and Rinkel, G. European stroke organization guidelines for the management of intracranial aneurysms and subarachnoid haemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis. (2013) 35:93–112. doi: 10.1159/000346087

14. Connolly, ES Jr, Rabinstein, AA, Carhuapoma, JR, Derdeyn, CP, Dion, J, Higashida, RT, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. (2012) 43:1711–37. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182587839

15. Ascanio, LC, Enriquez-Marulanda, A, Maragkos, GA, Salem, MM, Alturki, AY, Ravindran, K, et al. Effect of blood pressure variability during the acute period of subarachnoid hemorrhage on functional outcomes. Neurosurgery. (2020) 87:779–87. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyaa019

16. Wang, J, Li, R, Li, S, Ma, T, Zhang, X, Ren, Y, et al. Intraoperative arterial pressure and delayed cerebral ischemia in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage after surgical clipping: a retrospective cohort study. Front Neurosci. (2023) 17:1064987. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2023.1064987

17. Hoff, RG, VaND, G, Mettes, S, Verweij, BH, Algra, A, Rinkel, GJ, et al. Hypotension in anaesthetized patients during aneurysm clipping: not as bad as expected? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. (2008) 52:1006–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01682.x

18. Chang, HS, Hongo, K, and Nakagawa, H. Adverse effects of limited hypotensive anesthesia on the outcome of patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. (2000) 92:971–5. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.92.6.0971

19. Chong, JY, Kim, DW, Jwa, CS, Yi, HJ, Ko, Y, and Kim, KM. Impact of cardio-pulmonary and intraoperative factors on occurrence of cerebral infarction after early surgical repair of the ruptured cerebral aneurysms. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. (2008) 43:90–6. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2008.43.2.90

20. Rowland, MJ, Hadjipavlou, G, Kelly, M, Westbrook, J, and Pattinson, KTS. Delayed cerebral ischaemia after subarachnoid haemorrhage: looking beyond vasospasm. Br J Anaesth. (2012) 109:315–29. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes264

21. Budohoski, KP, Czosnyka, M, Kirkpatrick, PJ, Smielewski, P, Steiner, LA, and Pickard, JD. Clinical relevance of cerebral autoregulation following subarachnoid haemorrhage. Nat Rev Neurol. (2013) 9:152–63. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.11

22. Svedung Wettervik, T, Howells, T, Hanell, A, Ronne-Engstrom, E, Lewen, A, and Enblad, P. Low intracranial pressure variability is associated with delayed cerebral ischemia and unfavorable outcome in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Clin Monit Comput. (2021) 36:569–78. doi: 10.1007/s10877-021-00688-y

23. Goldstein, B, Fiser, DH, Kelly, MM, Mickelsen, D, Ruttimann, U, and Pollack, MM. Decomplexification in critical illness and injury: relationship between heart rate variability, severity of illness, and outcome. Crit Care Med. (1998) 26:352–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199802000-00040

24. Soehle, M, Czosnyka, M, Chatfield, DA, Hoeft, A, and Pena, A. Variability and fractal analysis of middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity and arterial blood pressure in subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. (2008) 28:64–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600506

25. Schmidt, JM. Heart rate variability for the early detection of delayed cerebral ischemia. J Clin Neurophysiol. (2016) 33:268–74. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0000000000000286

26. Constantinescu, V, Matei, D, Ignat, B, Hodorog, D, and Cuciureanu, DI. Heart rate variability analysis a useful tool to assess poststroke cardiac dysautonomia. Neurologist. (2020) 25:49–54. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0000000000000270

27. Treggiari, MM, Romand, JA, Martin, JB, Reverdin, A, Rufenacht, DA, and De Tribolet, N. Cervical sympathetic block to reverse delayed ischemic neurological deficits after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. (2003) 34:961–7. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000060893.72098.80

Keywords: subarachnoid hemorrhage, aneurysm, aortic blood pressure, variability, prognostic factors

Citation: Han X, Luo G, Li J, Liu R, Zhu N, Jiang S, Ma W, Cheng Y and Liu F (2024) Association between blood pressure control during aneurysm clipping and functional outcomes in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Front. Neurol. 15:1415840. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1415840

Edited by:

Bipin Chaurasia, Neurosurgery Clinic, NepalReviewed by:

Fulvio Tartara, University Hospital of Parma, ItalyYu Deok Won, Hanyang University Guri Hospital, Republic of Korea

Copyright © 2024 Han, Luo, Li, Liu, Zhu, Jiang, Ma, Cheng and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fude Liu, bGl1ZnVkZTEwMUAxNjMuY29t; Yawen Cheng, YWxpY2lhX2NoZW5nQDEyNi5jb20=

Xiangning Han

Xiangning Han Guogang Luo

Guogang Luo Jiahao Li

Jiahao Li Rui Liu

Rui Liu Fude Liu

Fude Liu