94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Neurol., 21 July 2023

Sec. Neurotrauma

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1214814

Grant L. Iverson1,2,3,4,5*

Grant L. Iverson1,2,3,4,5* Alicia Kissinger-Knox1,2,5

Alicia Kissinger-Knox1,2,5 Nathan A. Huebschmann6

Nathan A. Huebschmann6 Rudolph J. Castellani7

Rudolph J. Castellani7 Andrew J. Gardner8

Andrew J. Gardner8Introduction: Some ultra-high exposure boxers from the 20th century suffered from neurological problems characterized by slurred speech, personality changes (e.g., childishness or aggressiveness), and frank gait and coordination problems, with some noted to have progressive Parkinsonian-like signs. Varying degrees of cognitive impairment were also described, with some experiencing moderate to severe dementia. The onset of the neurological problems often began while they were young men and still actively fighting. More recently, traumatic encephalopathy syndrome (TES) has been proposed to be present in athletes who have a history of contact (e.g., soccer) and collision sport participation (e.g., American-style football). The characterization of TES has incorporated a much broader description than the neurological problems described in boxers from the 20th century. Some have considered TES to include depression, suicidality, anxiety, and substance abuse.

Purpose: We carefully re-examined the published clinical literature of boxing cases from the 20th century to determine whether there is evidence to support conceptualizing psychiatric problems as being diagnostic clinical features of TES.

Methods: We reviewed clinical descriptions from 155 current and former boxers described in 21 articles published between 1928 and 1999.

Results: More than one third of cases (34.8%) had a psychiatric, neuropsychiatric, or neurobehavioral problem described in their case histories. However, only 6.5% of the cases were described as primarily psychiatric or neuropsychiatric in nature. The percentages documented as having specific psychiatric problems were as follows: depression = 11.0%, suicidality = 0.6%, anxiety = 3.9%, anger control problems = 20.0%, paranoia/suspiciousness = 11.6%, and personality change = 25.2%.

Discussion: We conclude that depression, suicidality (i.e., suicidal ideation, intent, or planning), and anxiety were not considered to be clinical features of TES during the 20th century. The present review supports the decision of the consensus group to remove mood and anxiety disorders, and suicidality, from the new 2021 consensus core diagnostic criteria for TES. More research is needed to determine if anger dyscontrol is a core feature of TES with a clear clinicopathological association. The present findings, combined with a recently published large clinicopathological association study, suggest that mood and anxiety disorders are not characteristic of TES and they are not associated with chronic traumatic encephalopathy neuropathologic change.

The purpose of this review is to carefully re-examine the published clinical literature on chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) from the 20th century to determine whether there is evidence to support conceptualizing psychiatric problems as being diagnostic clinical features. We identified 155 case descriptions of boxers and former boxers from 21 published studies (1–21). Those articles are presented in Table 1. These articles were identified exclusively from three previously published narrative and systematic reviews (27–29). The clinical descriptions contained in these published articles are summarized in the Supplementary material. Our primary focus for this review was on whether depression, suicidality, and problems with anxiety were described as features of the clinical condition during the 20th century. These mental health problems have been assumed to be characteristic of CTE over the past 10–15 years.

There have been fundamental and persistent misunderstandings regarding CTE over the past decade. Contributing to this misunderstanding has been the terminology. The same term ‘CTE’ has been used to describe both postmortem microscopic neuropathology and broad range of antemortem psychiatric, neuropsychiatric, and neurological clinical symptoms, signs, and conditions (27, 30, 31). Some researchers have emphasized the importance of separating, not conflating, the neuropathology from the putative clinical disorder (32, 33), and as such, the terms ‘CTE neuropathologic change’ (CTE-NC) (34) or ‘CTE neuropathology’ (32, 33) have been recommended for use as opposed to referring to both the neuropathology and purported clinical features with the same term—CTE. In this paper, we will clearly differentiate the postmortem pathology using terms like CTE-NC or CTE neuropathology.

This paper is divided into six sections. First, the introduction (above). Second, we provide some historical background on the clinical condition based on articles published in the 20th century. Third, we contrast that literature with studies published this century, between 2005 and the present. We also compare and contrast the 2014 preliminary research criteria for traumatic encephalopathy syndrome (TES) (35) with the new 2021 consensus criteria for TES (36). The 2014 criteria (35) had a strong emphasis on mental health problems and specific psychiatric disorders—and this emphasis fundamentally changed in the 2021 consensus criteria for TES (36). Fourth, we review the psychiatric features of the 155 cases of boxers described in the published literature during the 20th century. Fifth, implications for drawing conclusions about associations between postmortem neuropathology and psychiatric symptoms and problems are discussed. The final section provides conclusions.

In the 20th century, CTE was conceptualized as a neurological condition experienced by some ultra-high exposure boxers—and in a severe form it was referred to as dementia pugilistica (37, 38). Some of these boxers had slurred speech, personality changes (e.g., childishness or aggressiveness), and frank gait and coordination problems (2, 5, 9, 11–14, 39, 40). Some were noted to have progressive Parkinsonian-like signs (2, 5, 9, 11–14, 17, 19). Damage to the brain was obvious enough that it was illustrated through clinical neurological examination, including pyramidal signs such as abnormal reflexes (e.g., hyperreflexia or occasionally depressed ‘sluggish’ reflexes) (2–6, 8, 9, 11, 13, 14, 16, 19, 21, 26, 41), including asymmetric hyperreflexia favoring the left side (2, 4, 8, 9, 11). Neuro-ophthalmological problems, including nystagmus, sluggish pupillary reflexes, optic atrophy, and restriction of upward gaze, were described (2, 8–11, 13, 16, 26). The neurological problems experienced by these men were sometimes documented in their 20s and early 30s while they were still actively fighting (2, 4–6, 9, 11–14). These men did not invariably have progressive neurological signs according to the published literature. Some authors (1–3, 7, 11, 12, 29, 38, 42, 43) described progressive motor signs as well as progressive dementia in some cases and others describing a more static or stationary neurological condition. Still others described progression to a point, followed by stationary disease [e.g., Critchley in 1957 (case 8) (5) and Johnson in 1969 (case 6) (12)].

In the late 1960s, Roberts (11) published a book entitled Brain Damage in Boxers: A Study of the Prevalence of Traumatic Encephalopathy Among Ex-Professional Boxers. He provided a clinical description of a random sample of 224 retired professional boxers, who competed between 1929 and 1955, and had extensive exposure to boxing over many years. He described the syndrome as predominately cerebellar or extrapyramidal, typically characterized by dysarthria and motor problems, with some cases having dementia. He reported that 11% of his random sample were deemed to have a mild form of the syndrome and 6% were considered to have a moderate-to-severe form of the syndrome. He did not consider the large majority of boxers to have the syndrome. Those who participated in a large number of professional fights, and those who fought prior to World War II, were considerably more likely to have the condition.

One article, by Johnson in 1969, was entitled ‘Organic Psychosyndromes Due to Boxing’ (12). Johnson noted that not much had been written about the psychiatric problems experienced by boxers. His article was based on clinical examinations of 17 boxers who presented to the hospital with neuropsychiatric symptoms thought to be connected to their boxing career, with 10 of those cases previously described by Mawdsley and Ferguson in 1963 (9). Sixteen of the 17 cases were former professional boxers, with 200–300 professional fights, and many had permanent facial disfigurement. He described one case as an amateur who ‘developed anxiety symptoms following a domestic crisis and falsely attributed these to insidious “punch drunkenness.” All investigations were normal and at follow-up he was symptom free’ (page 45). Johnson noted that the neurological condition was progressive in eight cases and not progressive in the other eight cases. He wrote that ‘the accepted title given to this condition by Critchley (1957) implies that progression is inevitable. Certainly this is not so in all cases. Cases 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 13, 14 had not deteriorated over the years of the follow-up of this study, and indeed according to relatives’ accounts they had deteriorated little since the end of their fighting careers’ (page 52). He considered the main psychiatric clinical syndromes to be (i) ‘chronic amnestic state’ (i.e., memory impairment, usually not progressive), (ii) ‘dementia’ (with mental torpor and flat affective responses), (iii) ‘morbid jealousy syndrome’ (in relation to their wives), (iv) ‘rage reactions in personality disorder’ (with impulsive acts of violence, often while intoxicated), and (v) psychosis. Two of his cases experienced chronic psychosis (and both had a history of mental illness in a first-degree relative). He concluded by stating that an ‘organic psychosyndrome was manifest in a chronic amnesic state, morbid jealousy reactions, psychosis and “explosive” personality disorder in varying combination in 14 cases’ (page 52) (12).

At the beginning of this century, Jordan published a review of the 20th century literature relating to what he termed ‘chronic traumatic brain injury’ [CTBI (44);]. He included a broader description of chronic brain damage in boxers, with CTE and dementia being the most severe. He described CTBI in a relatively mild form as involving mild dysarthria and difficulty with balance, while those with more extensive neurological problems experience ataxia, spasticity, and Parkinsonism. He reported that cognitive impairment could range from mild to dementia, and diverse behavioral changes might include irritability, euphoria or hypomania, disinhibition, impaired insight, paranoia, and violent outbursts. Jordan noted that it was unclear whether CTBI in boxers reflected a progressive neurodegenerative disease, whether it reflected the aging process superimposed on more static TBI-related neurological injury, or both.

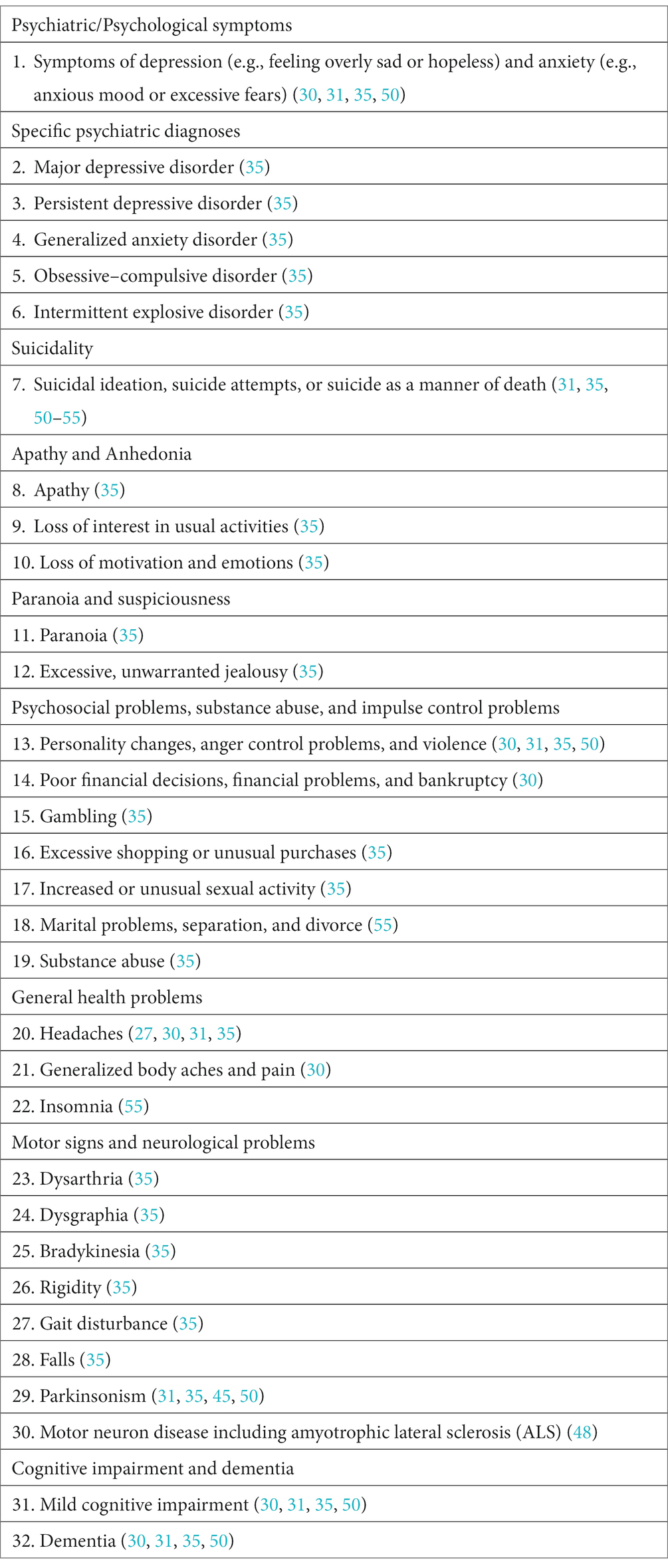

There has been a large amount of research on CTE-NC in the past 17 years. Postmortem case studies of this neuropathology (30, 45–49) and a comprehensive review of the literature (27) were published between 2005 and 2012. A larger postmortem case series was published in 2013 (31). In 2014, a new and comprehensive set of preliminary clinical diagnostic criteria were published, designed to identify traumatic encephalopathy syndrome (TES) in living research subjects (35). It is during this time, from 2005–2015, when CTE (including CTE-NC), and TES, were conceptualized very differently than they were in the 20th century. Virtually any psychosocial, psychiatric, or neurological symptom or problem that a person experienced during life was attributed, directly or indirectly, to ‘CTE’ (30, 31, 35, 45, 48, 50–55), and thus by inference, to specific neuropathology identified after death (i.e., CTE-NC). This is illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2. Psychiatric, psychological, psychosocial, and neurological signs, symptoms, and disorders that have been described as part of the clinical features of traumatic encephalopathy syndrome and CTE between 2009 and 2014.

In 2016, a consensus group published preliminary criteria for defining the microscopic neuropathology of CTE-NC and establishing the research methodology for case identification (56). The consensus group defined a descriptive pathognomonic lesion based on microscopic assessment of p-tau immunohistochemical stains as follows: ‘p-tau aggregates in neurons, astrocytes, and cell processes around small vessels in an irregular pattern at the depths of the cortical sulci’ (page 81). The authors described these preliminary criteria as a first step toward the development of validated criteria for CTE-NC and they reported that future researchers could address the potential contribution of p-tau and other pathologies to clinical signs or symptoms. In 2021, the consensus group published updated and revised consensus criteria for CTE-NC (57). The revised pathognomonic lesion was described as ‘p-tau aggregates in neurons, with or without thorn-shaped astrocytes, at the depth of a sulcus around a small blood vessel, deep in the parenchyma, and not restricted to the subpial or superficial region of the sulcus’ (page 217). The consensus group who published the preliminary criteria for CTE-NC in 2016 (56) and the revised criteria in 2021 (57) did not attempt to define clinical signs, symptoms, or a clinical syndrome. They encouraged future researchers to determine if there is an association between the postmortem neuropathology and specific neurological problems during a person’s lifetime.

During 2021, two major efforts were published: revised consensus criteria for CTE-NC (57) and the first consensus criteria for TES (36). Prior to 2021, there were large gaps in knowledge that were described in critical reviews (32, 33, 58)—and many major knowledge gaps persist to the present day. The prevalence rates of the neuropathology, interobserver variability in CTE-NC interpretation, and the putative clinical features were unknown. It was not known whether, or the extent to which, either the presumed neuropathology or the presumed clinical features are inexorably progressive. It was not known whether, or the extent to which, the emergence, course, or severity of clinical signs and symptoms are caused directly or indirectly by CTE neuropathology. Moreover, prior to 2021, there were no agreed upon, or validated, criteria for diagnosing CTE or TES in a living person. There were several attempts to create clinical diagnostic criteria for CTE and TES, published between 2013 and 2018 (29, 35, 59–61), but none of these criteria were rigorously researched or validated. All of the aforementioned knowledge gaps remain in 2023.

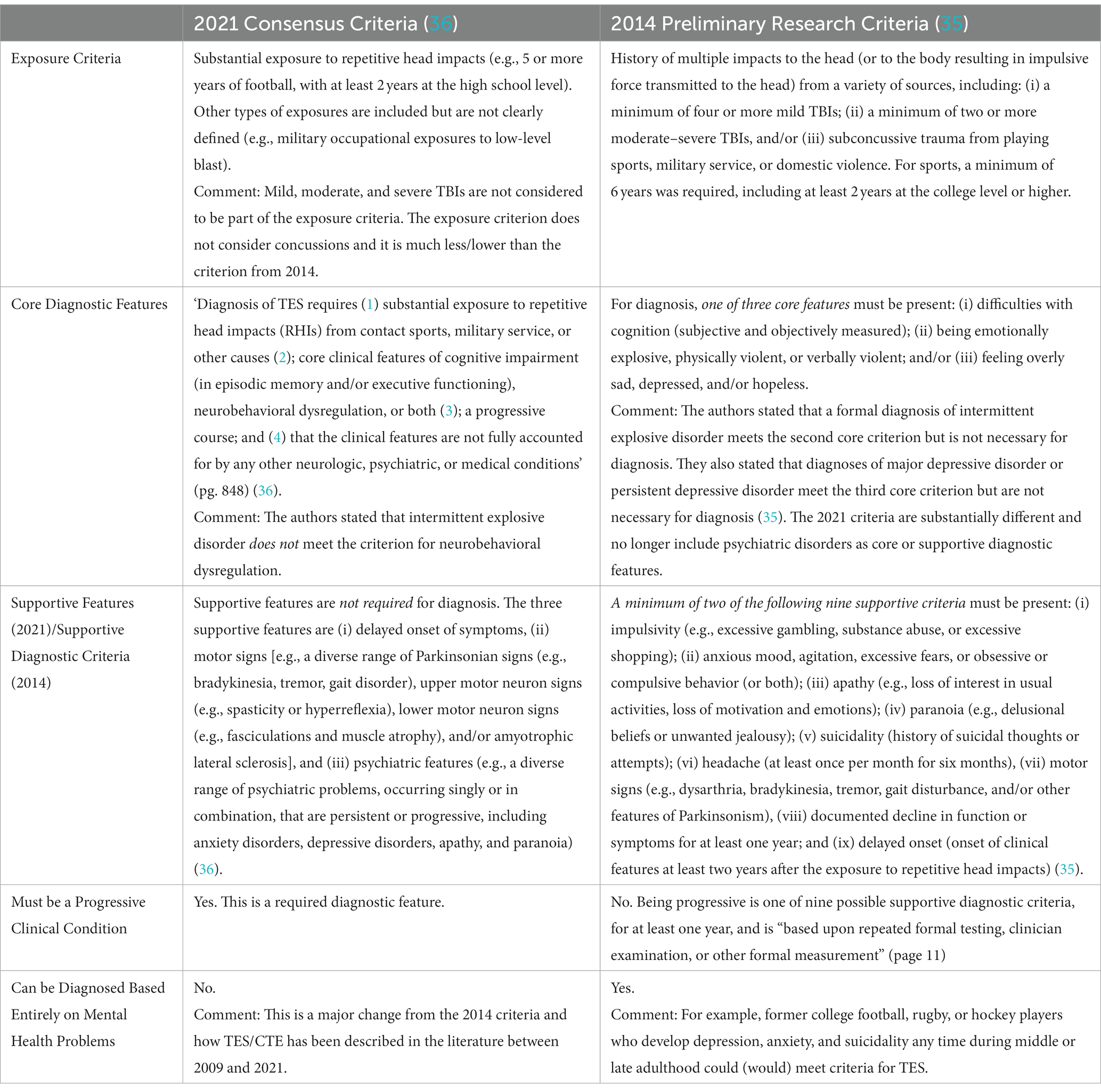

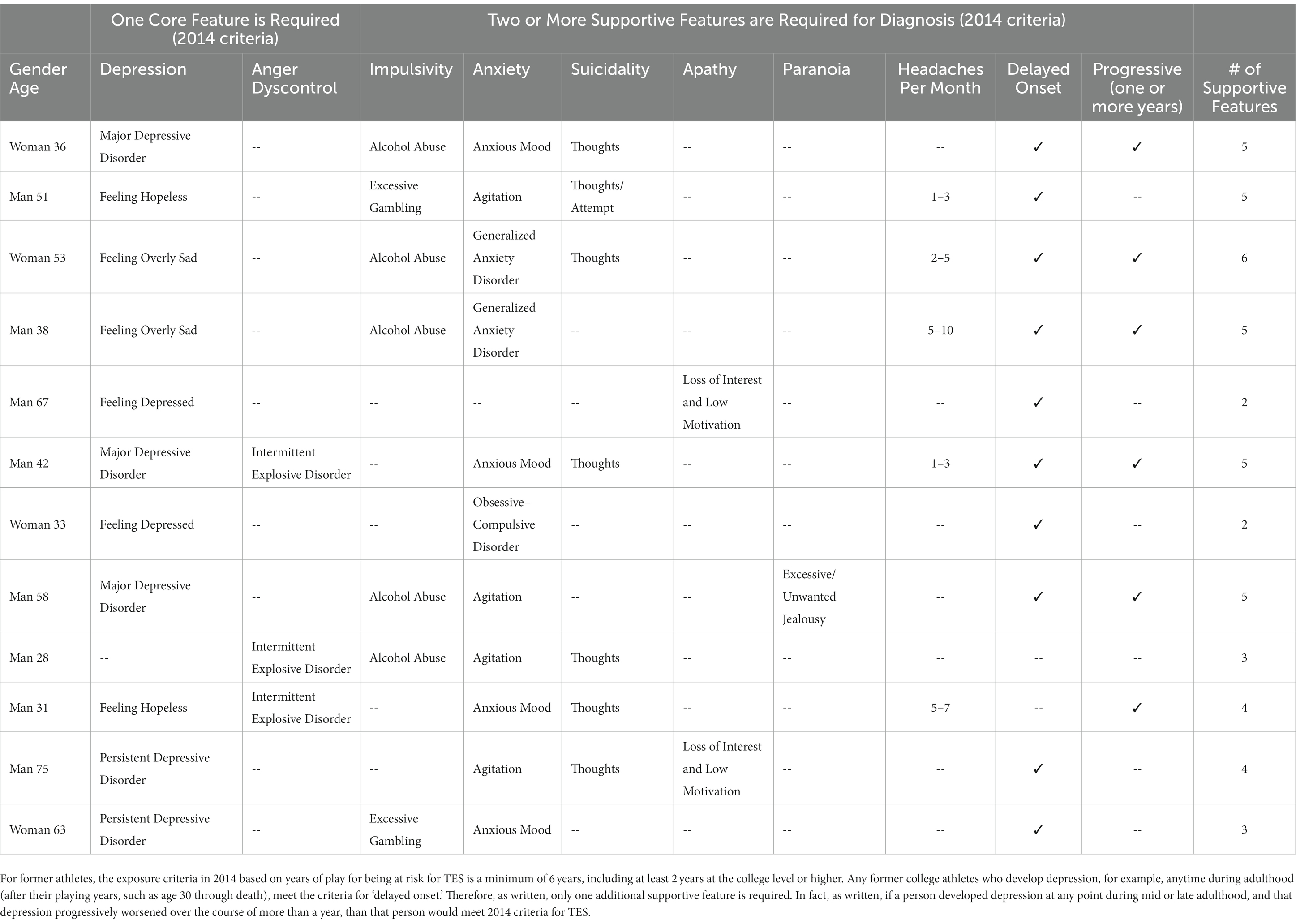

New consensus criteria for TES were published in 2021 (36). They were developed through a Delphi process by a multidisciplinary group of clinicians and scientists, led by researchers from Boston University. They used the preliminary 2014 research criteria (35) as the foundation for their work. Those 2014 criteria were broad, heavily focused on psychiatric problems, and several studies illustrated problems with applying the diagnostic criteria and their associated risk for misdiagnosis (62–65). The core features of the 2014 criteria included depression (e.g., major depressive disorder), anger dyscontrol (e.g., intermittent explosive disorder), and cognitive impairment (e.g., mild cognitive impairment or dementia). For the 2021 consensus criteria for TES (36), no parts of the 2014 criteria (35) were retained in their original form. Importantly, having major depressive disorder or intermittent explosive disorder is no longer allowed to meet core criteria for TES, and anxiety disorders and suicidality are no longer considered to be supportive diagnostic features. The two sets of criteria for TES are compared in Table 3. Twelve hypothetical cases of former contact and collision sport athletes, who developed psychiatric problems after their sporting careers, are presented in Table 4. These cases illustrate how people presenting with a diverse range of psychiatric and psychosocial difficulties could have been diagnosed with TES using the preliminary 2014 criteria but none of these cases would be considered to have TES based on the 2021 consensus criteria.

Table 3. Comparing the 2014 preliminary research diagnostic criteria to the 2021 consensus criteria for traumatic encephalopathy syndrome.

Table 4. Twelve hypothetical examples of psychiatric presentations in former college football, soccer, ice hockey, or rugby athletes that would meet 2014 (35) criteria for traumatic encephalopathy syndrome (TES) but not the 2021 consensus criteria (36) for TES.

We initially identified 26 published articles from the 20th century (1–26) that included 163 cases, 158 of whom were men and current or former boxers—although three were duplicates leaving a sample size of 155 from 21 published articles (see Table 1; Supplementary material). Two authors (NAH and AKK) reviewed each article, extracted quotes relating to the clinical features, and coded the cases based on clinical features (see Supplementary material). The psychiatric and neuropsychiatric clinical features from those cases are summarized in Table 5.

More than one third of cases (34.8%) had a psychiatric, neuropsychiatric, or neurobehavioral problem described in their case histories. However, only 6.5% of the cases were described as primarily psychiatric/neuropsychiatric in nature. We did not find evidence that the authors of these articles conceptualized these cases as having predominantly a psychiatric condition such as depression or an anxiety disorder. There were only 14.8% of the cases who had depression, suicidality, or anxiety documented. Quotes from articles describing cases as having major psychiatric problems are reprinted in Table 6.

Depression was reported in some cases from the 20th century (11.0%, see Table 5) (3, 8–12, 14, 19). In general, depression was not reported to be the primary problem, or the only problem, but rather it was reported in the context of a broader clinical history and there was an emphasis on the neurological condition and not mental health (see Supplementary material). We did not find evidence to suggest that authors in the 20th century conceptualized CTE, TES, or dementia pugilistica as a primary depressive disorder or involving a neurologically-mediated secondary depressive disorder.

It is important to keep in mind that former contact, collision, or contact sport athletes, or high exposure military veterans, might develop depression for reasons that are similar to those experienced by people in the general population. Depression in the general population is associated with genetics (66), adverse events in childhood (67, 68), and current life stressors (69). It is also associated with chronic pain (70), headaches and migraines (71, 72), chronic insomnia (73), and sleep apnea (74). A systematic review concluded that there might be a bidirectional relationship between symptoms of depression and cardiovascular health (75). It is also well established that there is an association between diabetes and depression (76), and although the mechanisms underlying that association are not well understood, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that there might be a bidirectional longitudinal association (77). It is also essential to appreciate that neurological problems and diseases in older adults are associated with depression, such as Parkinson’s disease (78), mild cognitive impairment (79), and Alzheimer’s disease (80). Therefore, it is apparent that possible associations between repetitive mild neurotrauma, later in life depression, and the presence of CTE-NC might be influenced by many other factors.

We did not find evidence in our review that anxiety, or anxiety disorders—such as generalized anxiety disorder or obsessive–compulsive disorder—were conceptualized as being a core or supportive clinical feature of TES during the 20th century. Some form of anxiety was described in only 3.9% of cases (2–4, 6, 8). When it was described, it was usually included in the case histories of former boxers who clearly had neurological problems (see Supplementary material). For example: “At times he is anxious or depressed….The positive neurological signs consisted of slow slurred speech, unsteady gait, moderate right-sided hemiparesis, and partial right optic atrophy. There was no dysphasia, he dragged his right foot when walking, and all movements were performed slowly and carefully. There was moderate ataxia on formal testing in all limbs, more marked on the right. There was no diplopia, ocular movements were normal…” (8) (page 1,206). Another example was as follows: “…of late he had been getting nervous. The main feature in his case was a spastic, stammering type of dysarthria and a habit of talking without opening his mouth sufficiently” (page 136) (5).

We found no evidence in our review that suicidality (i.e., suicidal ideation, intent, or planning), or suicide as a manner of death, were conceptualized as being core or supportive clinical features of TES during the 20th century. Similarly, in their review of the world literature on CTE, McKee and colleagues, in 2009, did not consider suicidality or suicide to be a clinical feature (27). We identified only one case (0.6%) in the literature described as experiencing suicidality—and that person was part of the case series described by Corsellis and colleagues in 1973 (13). Notably, when the postmortem brain tissue from that case series was reexamined using the modern definition of CTE-NC (56), by Goldfinger and colleagues (81), the man who had suicidality documented did not have CTE-NC. He had Lewy body dementia, accompanied by aging-related tau astrogliopathy. Many studies in recent years have examined suicidality or suicide as a manner of death (82–90), some with former amateur athletes (82–85) and some with former professional athletes (86–90), and none of these studies found an association between playing contact or collision sports during youth or adulthood and future risk for suicidality or suicide.

In studies published last century, some current and former boxers had documented anger control problems and violent behavior during their lifetime (5, 9, 10, 12–14). Some authors speculated that anger dyscontrol and aggressiveness might have represented longstanding personality or behavioral characteristics in some boxers (6, 11, 13). In the present review, anger dyscontrol was identified in 19.0% of the cases (see Table 5). The anger dyscontrol documented in their case histories co-occurred with obvious neurological signs of damage to their brains, such as dysarthric speech, gait problems, and Parkinsonism, and virtually all had cognitive impairment or dementia (9–13) (see Supplementary material).

The preliminary 2014 criteria indicated that a diagnosis of intermittent explosive disorder would fulfill the core ‘behavioral’ clinical criterion for TES. This was problematic because intermittent explosive disorder is a psychiatric disorder that tends to emerge in adolescence and early adulthood, and people with intermittent explosive disorder often experience co-occurring mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders (91). Therefore, a person with primary neurodevelopmental intermittent explosive disorder could be misdiagnosed as having TES based on the 2014 criteria, as illustrated in one study (63). In the 2014 criteria, both depression and any form of anger control problems were considered to be core diagnostic features. This was also problematic because depression and anger attacks tend to co-occur in men in the general population (92, 93), reducing the specificity of these criteria and increasing the risk for misdiagnosis.

The 2021 consensus group disagreed with including intermittent explosive disorder as part of the criteria for TES, and the new consensus criteria explicitly state that it should not be considered part of the diagnostic criteria for TES (36). In contrast, they describe ‘neurobehavioral dysregulation’ as one of the core diagnostic features for TES. Neurobehavioral dysregulation is described as having: ‘symptoms and/or observed behaviors representing poor regulation or control of emotions and/or behavior, including (but not limited to) explosiveness, impulsivity, rage, violent outbursts, having a short fuse (exceeding what might be described as periodic episodes of minor irritability), or emotional lability (often reported as mood swings)’ (page 852) (36).

There are several reasons why neurobehavioral dysregulation might prove to be difficult to conceptualize in future studies of former contact and collision sport athletes or military veterans. It is possible that some people might have these characteristics as a longstanding part of their personality and behavior (94–101). Moreover, if so, these characteristics could be exacerbated by life stressors (102), including financial problems (103) or marital problems (103), depression (92, 93), substance abuse (104, 105), and a variety of neurological conditions and diseases such as severe TBI (106, 107), stroke (108–110), and Alzheimer’s disease (111, 112).

In recent years, since prior to the publication of the preliminary criteria for TES in 2014, there has been an assumption that the postmortem neuropathological entity identified via immunohistochemistry, CTE-NC, has an associated clinical syndrome (or syndromes)—and efforts to validate diagnostic criteria for TES with CTE-NC have been underway for many years. Many articles have asserted that psychiatric problems, such as depression, suicidality, anxiety, and substance abuse, are a fundamental part of the clinical condition of ‘CTE,’ for which CTE-NC is the presumed neuropathological substrate e.g., (see Table 2).

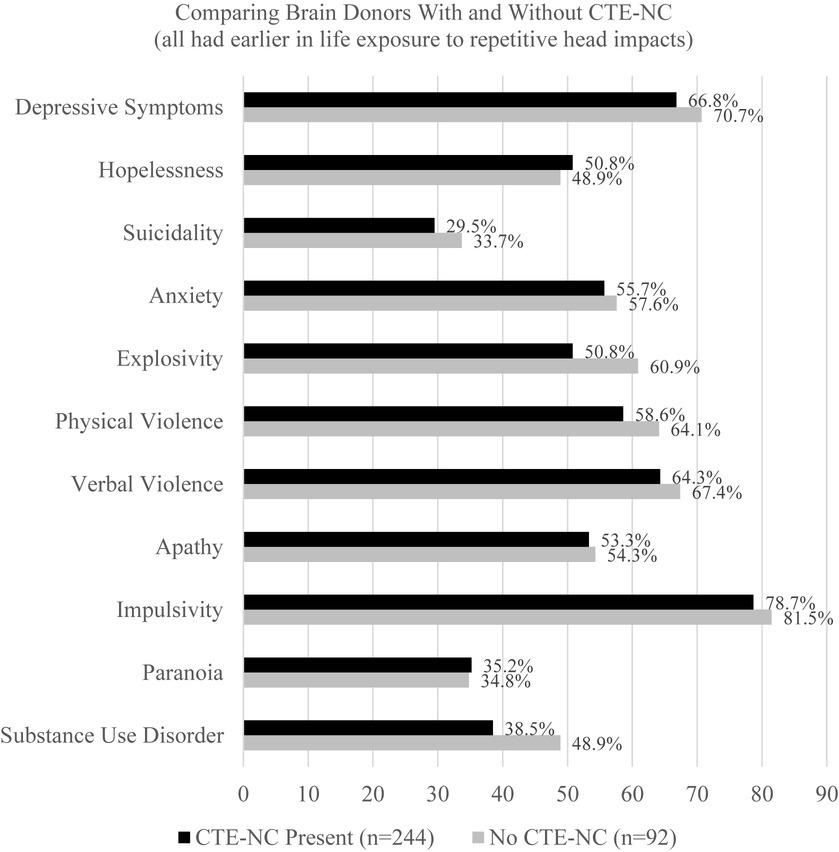

In 2021, a large-scale clinicopathological study designed to validate the 2014 criteria for TES was published, and the authors concluded that the TES criteria had high sensitivity for CTE-NC, but low specificity, and the mood (i.e., depression) and behavior (i.e., anger dyscontrol) symptoms of TES were not associated with CTE-NC (113). That study was extraordinarily important because (i) it was large, involving 336 brain donors who were exposed to repetitive head impacts from sports, military service, and/or physical violence, (ii) the neuropathology was rated without knowledge of the clinical information, and (iii) the clinical diagnostic criteria for TES were rated without knowledge of the neuropathology. Of the 336 brain donors, 244 (72.6%) were identified as having CTE-NC and 92 (27.4%) did not have CTE-NC. The individual psychiatric features that we rated in the present article, from the 155 boxers included in published articles from the 20th century, were also included in this clinicopathological correlation and validation study with brain donors from the past few years (113). There was no difference between those with CTE-NC and those who did not have the neuropathology in depressive symptoms, hopelessness, suicidality, anxiety, explosivity, physical violence, verbal violence, apathy, impulsivity, paranoia, or substance abuse (see supplementary Table S5, included in the online supplement from the article by Mez et al.) (113). This is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. No association between having chronic traumatic encephalopathy neuropathologic change and psychiatric features in former athletes and military veterans (N = 336) (113). CTE-NC, chronic traumatic encephalopathy neuropathologic change. These data were derived from 336 consecutive brain donors exposed to repetitive head impacts from sports, military service, and/or physical violence, 244 (72.6%) of whom were identified as having CTE-NC and 92 did not have CTE-NC (27.4%) (113). To create this figure, data were extracted from a table on pages 9 and 10 of the online supplement for the article by Mez et al. (113). There are no statistically significant differences in the proportions of the groups that have any of these psychiatric characteristics or features based on chi square tests.

The findings from the present study, and from the clinicopathological validation and association study summarized in Figure 1 (113), have implications for the new consensus criteria for TES. The authors of the consensus criteria wrote that psychiatric features “were not included as core features but reserved as supportive features that are used in determining levels of certainty for CTE pathology” (page 856) (36). These psychiatric features include anxiety, apathy, depression (e.g., “feeling overly sad, dysphoric, or hopeless, with or without a history of suicidal thoughts or attempts” page 856), and paranoia. In other words, if a research subject or clinical patient has one of those four psychiatric features, this is supposed to “increase levels of certainty” that the person harbors CTE-NC (that ultimately will be identifiable after death). However, according to the large-scale clinicopathological validation study there is no association between any of those psychiatric features and having CTE-NC after death (113) (see Figure 1). Therefore, there is a major problem with the new TES consensus criteria when used to try to draw an inference about the likelihood of having CTE-NC based on the presence (or absence) of these psychiatric features. Given that there is no association between the psychiatric features included in the 2021 TES consensus criteria (36) and the postmortem presence of CTE-NC (113), a future revision of the TES consensus criteria should consider dropping psychiatric features as factors that are assumed to increase the level of certainty that a person has CTE-NC.

During the 20th century, TES was described as a neurological condition, and in a severe form it was referred to as dementia pugilistica. Many articles discussed the onset of neurological problems reflecting chronic brain damage while the boxers were still actively fighting (1–5, 11, 12, 14, 18, 21). Many authors described the neurological condition as having a progressive course (3–6, 8, 9, 13–15, 18, 21, 22), but it was also discussed throughout the literature that the course does not appear to be progressive in some cases (11, 12). It was recognized last century that some current and former boxers had psychiatric and neuropsychiatric problems such as personality changes, impulsive aggressiveness and violence, paranoia, and psychosis.

In recent years, TES was reconceptualized to include a very broad range of psychosocial and mental health problems (31, 35, 50–55) (see Table 2). The reconceptualization of depression as being a diagnostic feature of TES was new to this century (35) (see Table 2), and did not appear in the literature we reviewed from the 20th century. Importantly, the 2021 TES consensus group (36) disagreed that psychiatric disorders should be conceptualized as diagnostic clinical features of TES, as defined in the 2014 preliminary diagnostic criteria (35), and removed them from the status of core or supportive diagnostic features. Instead, the new consensus criteria indicate that psychiatric problems often can be associated with TES but are not diagnostic of it.

The present review of cases from the 20th century supports the decision of the TES consensus group (36) to remove mood and anxiety disorders, and suicidality, from the diagnostic criteria for TES. That said, the consensus group designed the TES criteria so that having a psychiatric problem is assumed to increase the level of certainty that the person harbors CTE-NC. However, the best available evidence suggests that there is no association between the TES psychiatric features and having CTE-NC, as illustrated in Figure 1 (113). Therefore, the present review of cases from the 20th century, combined with a recently published large clinicopathological association study (113), suggests that depression, suicidality, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders are not characteristic features of TES and they are not associated with having the underlying neuropathology conceptualized as CTE-NC.

GI conceptualized and designed the review, assisted with the literature review, wrote sections of the manuscript and secured funding for the work. AK-K was the second author to review all articles and extract additional quotes for the Supplementary material, she entered data into the database and edited drafts of the manuscript. NH was the first author to review all articles and extract quotes for the Supplementary material, he designed the database and entered data and edited drafts of the manuscript. RC assisted with the literature review and edited drafts of the manuscript. AG assisted with conceptualizing the review, assisted with the literature review and extract additional quotes for the Supplementary material and edited drafts of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article, approved the submitted version and agree to be accountable for the content of the work.

The study was funded, as part of a program of research entitled improving the methodology for diagnosing traumatic encephalopathy syndrome (PI GI), by the Wounded Warrior Project™. This work was also funded, in part, by unrestricted philanthropic research support from the National Rugby League (AG and GI). GI acknowledges unrestricted philanthropic support from the Mooney-Reed Charitable Foundation, ImPACT Applications, Inc., the Heinz Family Foundation, Boston Bolts, and the Schoen Adams Research Institute at Spaulding Rehabilitation. None of the above entities were involved in the study design, analysis, interpretation, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

GI serves as a scientific advisor for NanoDX®, Sway Operations, LLC, and Highmark, Inc. He has a clinical and consulting practice in forensic neuropsychology, including expert testimony, involving individuals who have sustained mild TBIs (including former athletes), and on the topic of suicide. He has received past research support or funding from several test publishing companies, including ImPACT Applications, Inc., CNS Vital Signs, and Psychological Assessment Resources (PAR, Inc.). He receives royalties from the sales of one neuropsychological test (WCST-64). He has received travel support and honorariums for presentations at conferences and meetings. He has received research funding as a principal investigator from the National Football League, and subcontract grant funding as a collaborator from the Harvard Integrated Program to Protect and Improve the Health of National Football League Players Association Members. RC is a collaborator on a grant funded by the National Football League to study the spectrum of concussion, including possible long-term effects. He has a consulting practice in forensic neuropathology, including expert testimony, which has involved former athletes at amateur and professional levels, and sport organizations. AG serves as a scientific advisor for hitIQ, Ltd. He has a clinical practice in neuropsychology involving individuals who have sustained sport-related concussion (including current and former athletes). He has been a contracted concussion consultant to Rugby Australia since July 2016. He has received travel funding or been reimbursed by professional sporting bodies, and commercial organizations for discussing or presenting sport-related concussion research at meetings, scientific conferences, workshops, and symposiums. Previous grant funding includes the NSW Sporting Injuries Committee, the Brain Foundation (Australia), an Australian-American Fulbright Commission Postdoctoral Award, a Hunter New England Local Health District, Research, Innovation and Partnerships Health Research & Translation Centre and Clinical Research Fellowship Scheme, and the Hunter Medical Research Institute (HMRI), supported by Jennie Thomas, and the HMRI, supported by Anne Greaves. AG is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Investigator Grant. He acknowledges unrestricted philanthropic support from the National Rugby League for research in former professional rugby league players.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2023.1214814/full#supplementary-material

1. Martland, HS. Punch drunk. J Am Med Assoc. (1928) 91:1103–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.1928.02700150029009

2. Parker, HL. Traumatic encephalopathy (‘punch Drunk') of professional pugilists. J Neurol Psychopathol. (1934) s1-15:20–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.s1-15.57.20

3. Critchley, M. Punch-drunk syndromes: the chronic traumatic encephalopathy of boxers In: Maloine, editor. Hommage a Clovis Vincent. Strasbourg: Imprimerie Alascienne (1949). 131–45.

5. Critchley, M. Medical aspects of boxing, particularly from a neurological standpoint. Br Med J. (1957) 1:357–62. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5015.357

6. Neubuerger, KT, Sinton, DW, and Denst, J. Cerebral atrophy associated with boxing. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. (1959) 81:403–8. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1959.02340160001001

7. Courville, CB. Punch drunk. Its pathogenesis and pathology on the basis of a verified case. Bull Los Angel Neurol Soc. (1962) 27:160–8.

9. Mawdsley, C, and Ferguson, FR. Neurological disease in boxers. Lancet. (1963) 2:795–801. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(63)90498-7

11. Roberts, A. Brain damage in boxers: A study of prevalence of traumatic encephalopathy among ex-professional boxers. London: Pitman Medical Scientific Publishing Co. (1969).

12. Johnson, J. Organic psychosyndromes due to boxing. Br J Psychiatry. (1969) 115:45–53. doi: 10.1192/bjp.115.518.45

13. Corsellis, JA, Bruton, CJ, and Freeman-Browne, D. The aftermath of boxing. Psychol Med. (1973) 3:270–303. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700049588

15. Kaste, M, Kuurne, T, Vilkki, J, Katevuo, K, Sainio, K, and Meurala, H. Is chronic brain damage in boxing a hazard of the past? Lancet. (1982) 2:1186–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(82)91203-X

16. Casson, IR, Siegel, O, Sham, R, Campbell, EA, Tarlau, M, and DiDomenico, A. Brain damage in modern boxers. J Am Med Assoc. (1984) 251:2663–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.1984.03340440021020

17. Hof, PR, Bouras, C, Buee, L, Delacourte, A, Perl, DP, and Morrison, JH. Differential distribution of neurofibrillary tangles in the cerebral cortex of dementia pugilistica and Alzheimer's disease cases. Acta Neuropathol. (1992) 85:23–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00304630

18. Jordan, BD, Kanik, AB, Horwich, MS, Sweeney, D, Relkin, NR, Petito, CK, et al. Apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 and fatal cerebral amyloid angiopathy associated with dementia pugilistica. Ann Neurol. (1995) 38:698–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380429

19. Jordan, BD, Relkin, NR, Ravdin, LD, Jacobs, AR, Bennett, A, and Gandy, S. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 associated with chronic traumatic brain injury in boxing. J Am Med Assoc. (1997) 278:136–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550020068040

20. Geddes, JF, Vowles, GH, Nicoll, JA, and Revesz, T. Neuronal cytoskeletal changes are an early consequence of repetitive head injury. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). (1999) 98:171–8. doi: 10.1007/s004010051066

21. Drachman, DA, and Newell, KL. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 12-1999. A 67-year-old man with three years of dementia. N Engl J Med. (1999) 340:1269–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904223401609

22. Corsellis, JA, and Brierley, JB. Observations on the pathology of insidious dementia following head injury. J Ment Sci. (1959) 105:714–20. doi: 10.1192/bjp.105.440.714

23. Geddes, JF, Vowles, GH, Robinson, SF, and Sutcliffe, JC. Neurofibrillary tangles, but not Alzheimer-type pathology, in a young boxer. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. (1996) 22:12–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1996.tb00840.x

24. Hof, PR, Knabe, R, Bovier, P, and Bouras, C. Neuropathological observations in a case of autism presenting with self-injury behavior. Acta Neuropathol. (1991) 82:321–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00308819

25. Roberts, GW, Whitwell, HL, Acland, PR, and Bruton, CJ. Dementia in a punch-drunk wife. Lancet. (1990) 335:918–9. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90520-F

26. Williams, DJ, and Tannenberg, AE. Dementia pugilistica in an alcoholic achondroplastic dwarf. Pathology. (1996) 28:102–4. doi: 10.1080/00313029600169653

27. McKee, AC, Cantu, RC, Nowinski, CJ, Hedley-Whyte, ET, Gavett, BE, Budson, AE, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. (2009) 68:709–35. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a9d503

28. Gardner, A, Iverson, GL, and McCrory, P. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in sport: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. (2014) 48:84–90. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092646

29. Victoroff, J. Traumatic encephalopathy: review and provisional research diagnostic criteria. NeuroRehabilitation. (2013) 32:211–24. doi: 10.3233/NRE-130839

30. Omalu, B, Bailes, J, Hamilton, RL, Kamboh, MI, Hammers, J, Case, M, et al. Emerging histomorphologic phenotypes of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in American athletes. Neurosurgery. (2011) 69:173–83; discussion 83. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318212bc7b

31. McKee, AC, Stein, TD, Nowinski, CJ, Stern, RA, Daneshvar, DH, Alvarez, VE, et al. The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain. (2013) 136:43–64. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws307

32. Iverson, GL, Gardner, AJ, Shultz, SR, Solomon, GS, McCrory, P, Zafonte, R, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy neuropathology might not be inexorably progressive or unique to repetitive neurotrauma. Brain. (2019) 142:3672–93. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz286

33. Iverson, GL, Keene, CD, Perry, G, and Castellani, RJ. The need to separate chronic traumatic encephalopathy neuropathology from clinical features. J Alzheimers Dis. (2018) 61:17–28. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170654

34. Lee, EB, Kinch, K, Johnson, VE, Trojanowski, JQ, Smith, DH, and Stewart, W. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy is a common co-morbidity, but less frequent primary dementia in former soccer and rugby players. Acta Neuropathol. (2019) 138:389–99. doi: 10.1007/s00401-019-02030-y

35. Montenigro, PH, Baugh, CM, Daneshvar, DH, Mez, J, Budson, AE, Au, R, et al. Clinical subtypes of chronic traumatic encephalopathy: literature review and proposed research diagnostic criteria for traumatic encephalopathy syndrome. Alzheimers Res Ther. (2014) 6:68. doi: 10.1186/s13195-014-0068-z

36. Katz, DI, Bernick, C, Dodick, DW, Mez, J, Mariani, ML, Adler, CH, et al. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke consensus diagnostic criteria for traumatic encephalopathy syndrome. Neurology. (2021) 96:848–63. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011850

38. Grahmann, H, and Ule, G. Diagnosis of chronic cerebral symptoms in boxers (dementia pugilistica & traumatic encephalopathy of boxers). Psychiatr Neurol (Basel). (1957) 134:261–83. doi: 10.1159/000138743

39. Jedlinski, J, Gatarski, J, and Szymusik, A. Chronic posttraumatic changes in the central nervous system in pugilists. Pol Med J. (1970) 9:743–52.

40. Sercl, M, and Jaros, O. The mechanisms of cerebral concussion in boxing and their consequences. World Neurol. (1962) 3:351–8.

41. Ross, RJ, Cole, M, Thompson, JS, and Kim, KH. Boxers--computed tomography, EEG, and neurological evaluation. J Am Med Assoc. (1983) 249:211–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.1983.03330260029026

43. Mendez, MF. The neuropsychiatric aspects of boxing. Int J Psychiatry Med. (1995) 25:249–62. doi: 10.2190/CUMK-THT1-X98M-WB4C

44. Jordan, B. Chronic traumatic brain injury associated with boxing. Semin Neurol. (2000) 20:179–86. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9826

45. Omalu, BI, DeKosky, ST, Minster, RL, Kamboh, MI, Hamilton, RL, and Wecht, CH. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in a National Football League player. Neurosurgery. (2005) 57:128–34; discussion -34–34. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000163407.92769.ED

46. Omalu, BI, DeKosky, ST, Hamilton, RL, Minster, RL, Kamboh, MI, Shakir, AM, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in a national football league player: part II. Neurosurgery. (2006) 59:1086–93. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000245601.69451.27

47. Omalu, BI, Hamilton, RL, Kamboh, MI, DeKosky, ST, and Bailes, J. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in a National Football League Player: Case report and emerging medicolegal practice questions. J Forensic Nurs. (2010) 6:40–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-3938.2009.01064.x

48. McKee, AC, Gavett, BE, Stern, RA, Nowinski, CJ, Cantu, RC, Kowall, NW, et al. TDP-43 proteinopathy and motor neuron disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. (2010) 69:918–29. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181ee7d85

49. Goldstein, LE, Fisher, AM, Tagge, CA, Zhang, XL, Velisek, L, Sullivan, JA, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in blast-exposed military veterans and a blast neurotrauma mouse model. Sci Transl Med. (2012) 4:4862. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004862

50. Baugh, CM, Stamm, JM, Riley, DO, Gavett, BE, Shenton, ME, Lin, A, et al. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: neurodegeneration following repetitive concussive and subconcussive brain trauma. Brain Imaging Behav. (2012) 6:244–54. doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9164-5

51. Stern, RA, Daneshvar, DH, Baugh, CM, Seichepine, DR, Montenigro, PH, Riley, DO, et al. Clinical presentation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Neurology. (2013) 81:1122–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a55f7f

52. Gavett, BE, Stern, RA, and McKee, AC. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: a potential late effect of sport-related concussive and subconcussive head trauma. Clin Sports Med. (2011) 30:179–88, xi. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2010.09.007

53. Stern, RA, Riley, DO, Daneshvar, DH, Nowinski, CJ, Cantu, RC, and McKee, AC. Long-term consequences of repetitive brain trauma: chronic traumatic encephalopathy. PM R. (2011) 3:S460–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.08.008

54. Omalu, BI, Bailes, J, Hammers, JL, and Fitzsimmons, RP. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy, suicides and parasuicides in professional American athletes: the role of the forensic pathologist. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. (2010) 31:130–2. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0b013e3181ca7f35

55. Omalu, B. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Prog Neurol Surg. (2014) 28:38–49. doi: 10.1159/000358761

56. McKee, AC, Cairns, NJ, Dickson, DW, Folkerth, RD, Keene, CD, Litvan, I, et al. The first NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol. (2016) 131:75–86. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1515-z

57. Bieniek, KF, Cairns, NJ, Crary, JF, Dickson, DW, Folkerth, RD, Keene, CD, et al. The second NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. (2021) 80:210–9. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlab001

58. Iverson, GL, Gardner, AJ, McCrory, P, Zafonte, R, and Castellani, RJ. A critical review of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2015) 56:276–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.05.008

59. Jordan, BD. The clinical spectrum of sport-related traumatic brain injury. Nat Rev Neurol. (2013) 9:222–30. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.33

60. Reams, N, Eckner, JT, Almeida, AA, Aagesen, AL, Giordani, B, Paulson, H, et al. A clinical approach to the diagnosis of traumatic encephalopathy syndrome: a review. JAMA Neurol. (2016) 73:743–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.5015

61. Laffey, M, Darby, AJ, Cline, MG, Teng, E, and Mendez, MF. The utility of clinical criteria in patients with chronic traumatic encephalopathy. NeuroRehabilitation. (2018) 43:431–41. doi: 10.3233/NRE-182452

62. Iverson, GL, and Gardner, AJ. Symptoms of traumatic encephalopathy syndrome are common in the US general population. Brain Commun. (2021) 3:fcab001. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcab001

63. Iverson, GL, and Gardner, AJ. Risk for misdiagnosing chronic traumatic encephalopathy in men with anger control problems. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:739. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00739

64. Iverson, GL, and Gardner, AJ. Risk of misdiagnosing chronic traumatic encephalopathy in men with depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2020) 32:139–46. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.19010021

65. Iverson, GL, Merz, ZC, and Terry, DP. Examining the research criteria for traumatic encephalopathy syndrome in middle-aged men from the general population who played contact sports in high school. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:632618. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.632618

66. Sullivan, PF, Neale, MC, and Kendler, KS. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. (2000) 157:1552–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552

67. Bradley, RG, Binder, EB, Epstein, MP, Tang, Y, Nair, HP, Liu, W, et al. Influence of child abuse on adult depression: moderation by the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2008) 65:190–200. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.26

68. Heim, C, Newport, DJ, Mletzko, T, Miller, AH, and Nemeroff, CB. The link between childhood trauma and depression: insights from HPA axis studies in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2008) 33:693–710. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.008

69. Kendler, KS, Karkowski, LM, and Prescott, CA. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. (1999) 156:837–41. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837

70. Fishbain, DA, Cutler, R, Rosomoff, HL, and Rosomoff, RS. Chronic pain-associated depression: antecedent or consequence of chronic pain? A review. Clin J Pain. (1997) 13:116–37. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199706000-00006

71. Breslau, N, Schultz, LR, Stewart, WF, Lipton, RB, Lucia, VC, and Welch, KM. Headache and major depression: is the association specific to migraine? Neurology. (2000) 54:308–13. doi: 10.1212/WNL.54.2.308

72. Breslau, N, Lipton, RB, Stewart, WF, Schultz, LR, and Welch, KM. Comorbidity of migraine and depression: investigating potential etiology and prognosis. Neurology. (2003) 60:1308–12. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000058907.41080.54

73. Ohayon, MM, and Lemoine, P. Daytime consequences of insomnia complaints in the French general population. Encéphale. (2004) 30:222–7. doi: 10.1016/S0013-7006(04)95433-4

74. Garbarino, S, Bardwell, WA, Guglielmi, O, Chiorri, C, Bonanni, E, and Magnavita, N. Association of Anxiety and Depression in obstructive sleep apnea patients: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Behav Sleep Med. (2018) 18:35–57. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2018.1545649

75. Ogunmoroti, O, Osibogun, O, Spatz, ES, Okunrintemi, V, Mathews, L, Ndumele, CE, et al. A systematic review of the bidirectional relationship between depressive symptoms and cardiovascular health. Prev Med. (2022) 154:106891. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106891

76. Yu, M, Zhang, X, Lu, F, and Fang, L. Depression and risk for diabetes: a Meta-analysis. Can J Diabetes. (2015) 39:266–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2014.11.006

77. Beran, M, Muzambi, R, Geraets, A, Albertorio-Diaz, JR, Adriaanse, MC, Iversen, MM, et al. The bidirectional longitudinal association between depressive symptoms and HbA1c: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med. (2022) 39:e14671. doi: 10.1111/dme.14671

78. Djamshidian, A, and Friedman, JH. Anxiety and depression in Parkinson's disease. Curr Treat Options Neurol. (2014) 16:285. doi: 10.1007/s11940-014-0285-6

79. Barnes, DE, Alexopoulos, GS, Lopez, OL, Williamson, JD, and Yaffe, K. Depressive symptoms, vascular disease, and mild cognitive impairment: findings from the cardiovascular health study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2006) 63:273–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.273

80. Raskind, MA. Diagnosis and treatment of depression comorbid with neurologic disorders. Am J Med. (2008) 121:S28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.011

81. Goldfinger, MH, Ling, H, Tilley, BS, Liu, AKL, Davey, K, Holton, JL, et al. The aftermath of boxing revisited: identifying chronic traumatic encephalopathy pathology in the original Corsellis boxer series. Acta Neuropathol. (2018) 136:973–4. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1926-8

82. Iverson, GL, and Terry, DP. High school football and risk for depression and suicidality in adulthood: findings from a National Longitudinal Study. Front Neurol. (2022) 12:812604. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.812604

83. Iverson, GL, Merz, ZC, and Terry, DP. Playing high school football is not associated with an increased risk for suicidality in early adulthood. Clin J Sport Med. (2021) 31:469–74. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000890

84. Deshpande, SK, Hasegawa, RB, Weiss, J, and Small, DS. The association between adolescent football participation and early adulthood depression. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0229978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229978

85. Bohr, AD, Boardman, JD, and McQueen, MB. Association of Adolescent Sport Participation with Cognition and Depressive Symptoms in early adulthood. Orthop J Sports Med. (2019) 7:2325967119868658. doi: 10.1177/2325967119868658

86. Lincoln, AE, Vogel, RA, Allen, TW, Dunn, RE, Alexander, K, Kaufman, ND, et al. Risk and causes of death among former National Football League Players (1986-2012). Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2018) 50:486–93. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001466

87. Baron, SL, Hein, MJ, Lehman, E, and Gersic, CM. Body mass index, playing position, race, and the cardiovascular mortality of retired professional football players. Am J Cardiol. (2012) 109:889–96. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.10.050

88. Lehman, EJ, Hein, MJ, and Gersic, CM. Suicide mortality among retired National Football League Players who Played 5 or more seasons. Am J Sports Med. (2016) 44:2486–91. doi: 10.1177/0363546516645093

89. Russell, ER, McCabe, T, Mackay, DF, Stewart, K, MacLean, JA, Pell, JP, et al. Mental health and suicide in former professional soccer players. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2020) 91:1256–60. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323315

90. Taioli, E. All causes of mortality in male professional soccer players. Eur J Pub Health. (2007) 17:600–4. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm035

91. Scott, KM, Lim, CC, Hwang, I, Adamowski, T, Al-Hamzawi, A, Bromet, E, et al. The cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV intermittent explosive disorder. Psychol Med. (2016) 46:3161–72. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716001859

92. Painuly, N, Sharan, P, and Mattoo, SK. Relationship of anger and anger attacks with depression: a brief review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2005) 255:215–22. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0539-5

93. Painuly, NP, Grover, S, Gupta, N, and Mattoo, SK. Prevalence of anger attacks in depressive and anxiety disorders: implications for their construct? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2011) 65:165–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02177.x

94. Vitaro, F, Barker, ED, Boivin, M, Brendgen, M, and Tremblay, RE. Do early difficult temperament and harsh parenting differentially predict reactive and proactive aggression? J Abnorm Child Psychol. (2006) 34:685–95. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9055-6

95. Li, DP, Zhang, W, Li, DL, Wang, YH, and Zhen, SJ. The effects of parenting styles and temperament on adolescent aggression: examining unique, differential, and mediation effects. Acta Psychol Sin. (2012) 44:211–25. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2012.00211

96. Fox, NA, and Calkins, SD. Pathways to aggression and social withdrawal: interactions among temperament, attachments, and regulation In: KH Rubin and JB Asendorph, editors. Social withdrawal, inhibition, and shyness in childhood. New York: Psychology Press (2014). 81–100.

97. Gardner, BO, Boccaccini, MT, Bitting, BS, and Edens, JF. Personality assessment inventory scores as predictors of misconduct, recidivism, and violence: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Assess. (2015) 27:534–44. doi: 10.1037/pas0000065

98. Collins, K, and Bell, R. Personality and aggression: the dissipation-rumination scale. Pers Individ Dif. (1997) 22:751–5. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00248-6

99. Capaldi, DM, and Clark, S. Prospective family predictors of aggression toward female partners for at-risk young men. Dev Psychol. (1998) 34:1175–88. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.6.1175

100. Widom, CS, Czaja, S, and Dutton, MA. Child abuse and neglect and intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration: a prospective investigation. Child Abuse Negl. (2014) 38:650–63. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.11.004

101. Nicholas, KB, and Bieber, SL. Parental abusive versus supportive behaviors and their relation to hostility and aggression in young adults. Child Abuse Negl. (1996) 20:1195–211. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(96)00115-9

102. Aseltine, RH Jr, Gore, S, and Gordon, J. Life stress, anger and anxiety, and delinquency: an empirical test of general strain theory. J Health Soc Behav. (2000) 41:256–75. doi: 10.2307/2676320

103. Davis, GD, and Mantler, J. The consequences of financial stress for individuals, families and society. Centre for Research on stress, coping and well-being. Ottawa: Carlton University, Department of Psychology (2004).

104. Zarshenas, L, Baneshi, M, Sharif, F, and Moghimi, SE. Anger management in substance abuse based on cognitive behavioral therapy: an interventional study. BMC Psychiatry. (2017) 17:375. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1511-z

105. Reilly, PM, and Shopshire, MS. Anger management for substance abuse and mental health clients: cognitive behavioral therapy manual. J Drug Addict Educ Erad. (2002) 10:198–238.

106. Rao, V, Rosenberg, P, Bertrand, M, Salehinia, S, Spiro, J, Vaishnavi, S, et al. Aggression after traumatic brain injury: prevalence and correlates. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2009) 21:420–9. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2009.21.4.420

107. Cole, WR, Gerring, JP, Gray, RM, Vasa, RA, Salorio, CF, Grados, M, et al. Prevalence of aggressive behaviour after severe paediatric traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. (2008) 22:932–9. doi: 10.1080/02699050802454808

108. Kim, JS, Choi, S, Kwon, SU, and Seo, YS. Inability to control anger or aggression after stroke. Neurology. (2002) 58:1106–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.58.7.1106

109. Santos, CO, Caeiro, L, Ferro, JM, Albuquerque, R, and Luisa, FM. Anger, hostility and aggression in the first days of acute stroke. Eur J Neurol. (2006) 13:351–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01242.x

110. Paradiso, S, Robinson, RG, and Arndt, S. Self-reported aggressive behavior in patients with stroke. J Nerv Ment Dis. (1996) 184:746–53. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199612000-00005

111. Zahodne, LB, Ornstein, K, Cosentino, S, Devanand, DP, and Stern, Y. Longitudinal relationships between Alzheimer disease progression and psychosis, depressed mood, and agitation/aggression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2015) 23:130–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.03.014

112. Ballard, C, and Corbett, A. Agitation and aggression in people with Alzheimer's disease. Curr Opin Psychiatry. (2013) 26:252–9. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835f414b

Keywords: concussion, traumatic brain injury, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, boxing, athletes, depression

Citation: Iverson GL, Kissinger-Knox A, Huebschmann NA, Castellani RJ and Gardner AJ (2023) A narrative review of psychiatric features of traumatic encephalopathy syndrome as conceptualized in the 20th century. Front. Neurol. 14:1214814. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1214814

Received: 30 April 2023; Accepted: 26 June 2023;

Published: 21 July 2023.

Edited by:

Patricio F. Reyes, Barrow Neurological Institute (BNI), United StatesReviewed by:

Sara M. Lippa, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Iverson, Kissinger-Knox, Huebschmann, Castellani and Gardner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Grant L. Iverson, Z2l2ZXJzb25AbWdoLmhhcnZhcmQuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.