94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Neurol., 21 February 2022

Sec. Neurological Biomarkers

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.823919

This article is part of the Research TopicPotential Biomarkers in Neurovascular DisordersView all 50 articles

Kai Yan1

Kai Yan1 Wen-Qing Shi2

Wen-Qing Shi2 Ting Su3

Ting Su3 Xu-Lin Liao4

Xu-Lin Liao4 Shi-Nan Wu2

Shi-Nan Wu2 Qiu-Yu Li2

Qiu-Yu Li2 Jing Yu5

Jing Yu5 Hui-Ye Shu2

Hui-Ye Shu2 Li-Juan Zhang2

Li-Juan Zhang2 Yi-Cong Pan2

Yi-Cong Pan2 Yi Shao2*

Yi Shao2*Objective: We used the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) method to investigate spontaneous brain activity in patients with optic neuritis (ON) in specific frequency bands.

Data and Methods: A sample of 21 patients with ON (13 female and eight male) and 21 healthy controls (HCs) underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans in the resting state. We analyzed the ALFF values at different frequencies (slow-4 band: 0.027–0.073 Hz; slow-5 band: 0.01–0.027 Hz) in ON patients and HCs.

Results: In the slow-4 frequency range, compared with HCs, ON patients had apparently lower ALFF in the insula and the whack precuneus. In the slow-5 frequency range, ON patients showed significantly increased ALFF in the left parietal inferior and the left postcentral.

Conclusion: Our results suggest that ON may be involved in abnormal brain function and can provide a basis for clinical research.

Optic neuritis (ON) refers to all inflammatory lesions of the optic nerve, usually manifesting as acute or subacute vision loss with or without orbital pain, eye rotation pain, visual field defects or other clinical symptoms, and is the most common neurological disease leading to visual loss in young and middle-aged adults (1). The causes of optic neuritis are thought to include demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system, infectious diseases and immune diseases. A survey found that ON was the second most damaging disease among patients under 50 years of age after glaucomatous optic neuropathy (2). Worldwide, the annual incidence of unilateral optic neuritis is (0.94–2.18)/100,000, of which the annual incidence in the United Kingdom is 1/100,000 and that in Japan is 1.6/100,000 (3, 4). ON occurs predominantly in people aged 20–50, with an average age of onset of 36 years, and more than 70% of patients are female (5). Evidence suggests that there are racial and population differences in ON, which is more common among young, middle-aged, white females (6). Studies have shown that 80% of patients may have severe vision loss, and more than 60% of patients have monocular or binocular vision loss within 7.7 days after the first episode (7). The high incidence, young age of onset, high risk of blindness, and poor visual prognosis of ON have brought great physical and psychological burdens to patients and families, seriously affecting patients' quality of life. Its early diagnosis and treatment has become the focus of current research and the development of neuroimaging has provided a new method for the diagnosis of ON.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques have evolved rapidly to provide a non-invasive neuroimaging method that can assess functional and structural changes in the brain (8). Previous studies have demonstrated that synchronous brain activity is closely related to visual experience (9, 10). Resting state functional MRI (rsfMRI) was first proposed by Biswal (11) to assess consistent patterns of spontaneous fluctuation of blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signals during rest. These signals can be used to measure interhemispheric coordination (12).

The amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation is a widely used re-fMRI study method, which reflects the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal of spontaneous neural activity in the low-frequency band (0.01–0.08 Hz) and can detect the intrinsic local activity of the brain. In recent years, domestic and international researchers have started to use sub-band ALFF analysis to study the correlation between neural activity and cognitive function in different neurological diseases by subdividing the frequency range of spontaneous brain activity, including slow-6 (0–0.01Hz), slow-5 (0.01–0.027Hz), slow-4 (0.027–0.073Hz), slow-3 (0.073–0.198Hz), slow-6 (0–0.01Hz), and slow-2 (0.198–0.250Hz). Among them, slow-2, 3 and 6 frequencies correspond to high frequency physiological noise interference, white matter signal and low frequency drift signal, respectively. And the study of slow-4 and slow-5 specific frequency bands can study the spatial distribution characteristics of brain regions with abnormal spontaneous functional activity in the brain in more depth, which in turn reduces the interference of noise in other frequency bands and increases the sensitivity of detecting abnormal activity in brain regions. RsfMRI and both functional and anatomic imaging have been applied to various ocular diseases (13–19).

The present study aims to determine whether spontaneous brain activity is related to the clinical characteristics of patients with ON. To detect the spontaneous brain activity of ON patients and healthy controls (HCs), we used the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) technique to measure activity in different low frequency bands (slow 4 band: 0.027–0.073 Hz and slow 5 band: 0.01–0.027 Hz) and compared these between groups.

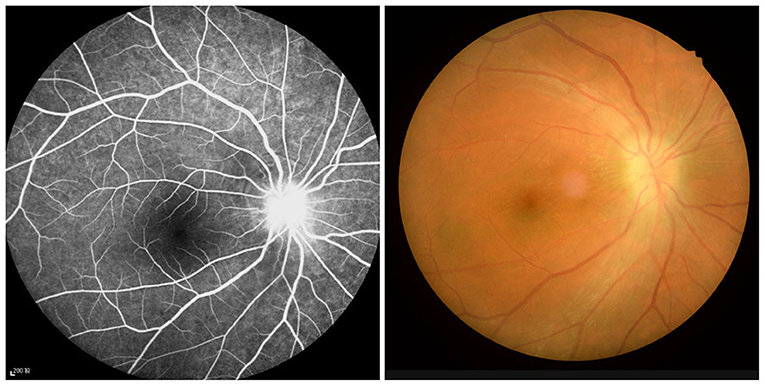

This study included 21 ON patients (13 females and eight males) admitted to the Ophthalmology Department of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (Nanchang, China). The selection criteria for all ON patients were: (1) the presence of eye pain related to acute vision loss; (2) nerve fiber damage and abnormal vision (Figure 1); (3) pupil block or abnormal visual evoked potential; (4) no other apparent cause of acute vision loss; (5) no medication taken before the examination; (6) no drug, alcohol, or tobacco addictions; and (7) no history of organ transplantation.

Figure 1. Example of optic neuritis observed using a FC and FFA. FC, fundus camera; FFA, fluorescence fundus angiography.

In addition, 21 age-matched HCs (13 females and eight males) were recruited. The inclusion criteria for HCs were as follows: (1) no abnormalities in brain parenchyma; (2) unilateral bare eye vision≥1.0 (3) normal nervous system.

All participants are able to go through an MRI scan. We used logMAR (Logarithm of Mininal Angle Resolution) method to obtain the best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of both groups and mean hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) to get the association with ALFF values.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, and all methods were applied in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. The study design description was provided to the participants before they signed informed consent forms.

All subjects underwent MRI scans in a 3-Tesla scanner (Trio, Siemens, Munich, Germany). They are constrained to the inspection area of the instrument and their heads are secured to prevent movement during the scanning process. During examination, the subjects remained awake, closed their eyes, and relaxed while avoiding focused thought. All scans were conducted by the same imaging physician, who observed the subjects until the process was completed successfully. Routine brain localization and T1 and T2 sequences were performed first. The specific parameters were: repeat time (TR) = 1,900 ms; echo time (TE) = 2.26 ms, thickness =1.0 mm, gap = 0.5 mm, acquisition matrix = 256 × 256, field of view (FOV) = 250 mm × 250 mm, and reversal angle = 90°. No substantial brain lesions were identified in the scanning process. RsfMRI data were acquired using a gradient-recalled echo sequence. The specific parameters were: TR = 2,000 ms, TE = 30 ms, thickness = 4.0 mm, gap = 1.2 mm, acquisition matrix = 64 × 64, flip angle = 90°, FOV = 220 mm × 220 mm. Data were collected continuously at 240 time points, and the scanning range included the whole brain.

Data were obtained from functional images using the MRIcro software package (www.MRIcro.com) after prefiltering. SPM8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) and DPARSFA (http://rfmri.org/ DPARSF) software were used to preliminarily analyze data before conversion to the NIFTI format. During magnetization equilibration the first 10 time points were discarded. Subjects were excluded if they had 1.5 angular motion or more than 1.5 mm maximum shift in the x, y, or z direction during the fMRI examination. After the head motion correction, the fMRI images were spatially normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute space criteria using the standard echo-planar imaging template and resampling the images at a resolution of 3 mm × 3 mm × 3 mm. On the basis of the above, the signals of slow-4 and slow-5 were extracted separately using band-pass filtering oscilloscope, and the ALFF values were calculated and analyzed by REST software (http://sourceforge.net/projects/testing-fmri).

Student's t-test was used to compare ALFF data between groups (20). A two-way analysis of variance and post-hoc tests were used to compare interaction s between groups and frequency bands. Based on Gaussian random field theory [z > 2.3, crowd >40 voxels, P < 0.01, false detection rate (FDR) corrected], we regulate the voxel offset (P < 0.05) as the statistical premise for comparisons.

Pearson correlation analysis was used to look for associations between ALFF and clinical level using a threshold of P < 0.05 for statistical significance.

No significant differences were found in age (P = 0.821), weight (P = 0.652), height (P = 0.634), or BMI (P = 0.963) between the two groups. Significant differences in best-corrected VA-right (P < 0.001) and best-corrected VA-left (P < 0.001) between the ON and HC groups. Details are shown in Table 1.

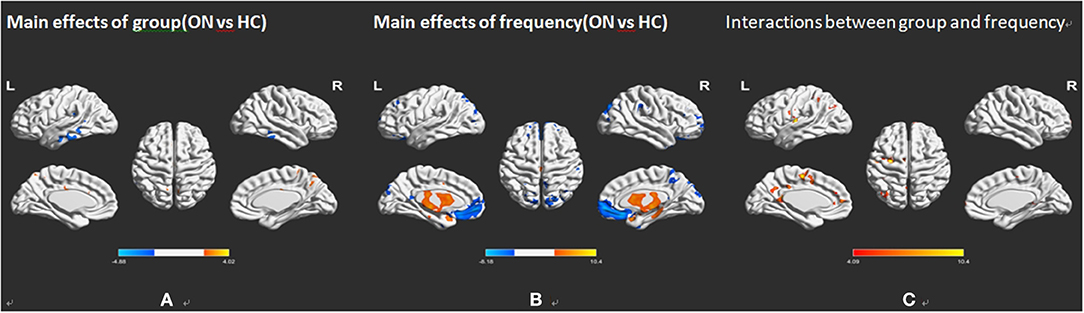

As shown in Figure 2A and Table 2, he two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was applied to explore main effects between groups. There were apparently increased ALFF (ON > HCs) in the right cerebellum, the right temporal inferior (temporal inf), the left temporal inf, and the left parietal inferior (parietal inf) and remarkably decreased ALFF (ON < HCs) in the left cingulum anterior (cingulum ant) and the right cingulum ant in brain regions with a main effect of group.

Figure 2. Frequency-associated ALFF analyses between the ON and HC groups. (A) Main effects of group, (B) main effects of frequency band, and (C) their interactions, with Gaussian random field theory correction, voxel-level P < 0.01 and cluster-level P < 0.05. Compared with HC, red represents the brain areas with increased AlFF, and blue represents the brain areas with decreased AlFF in patients with ON. ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation; ON, optic neuritis; L, left; HC, healthy control; R, right.

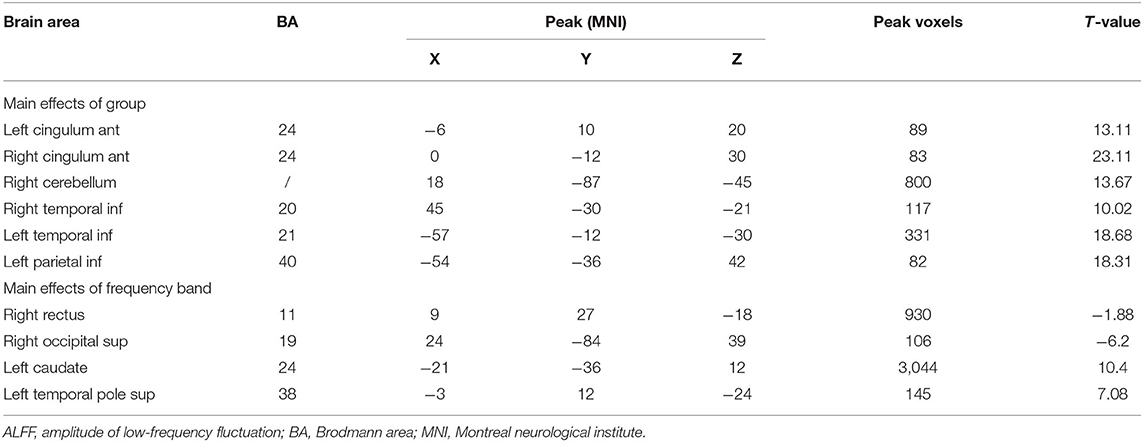

Table 2. Frequency-associated ALFF differences, with Gaussian random field theory correction, voxel-level P < 0.01 and cluster-level P < 0.05.

In several brain regions (Figure 2B; Table 2), the ALFF differed significantly between frequency bands, including increased ALFF of the right rectus gyri (slow-5 > slow-4), right supraoccipital segment (right supraoccipital) and decreased ALFF (Figure 2B; Table 2). Slow-5 < slow-4 in left caudate and left temporal pole sup. No obvious interaction was found between groups and frequency bands (Figure 2C).

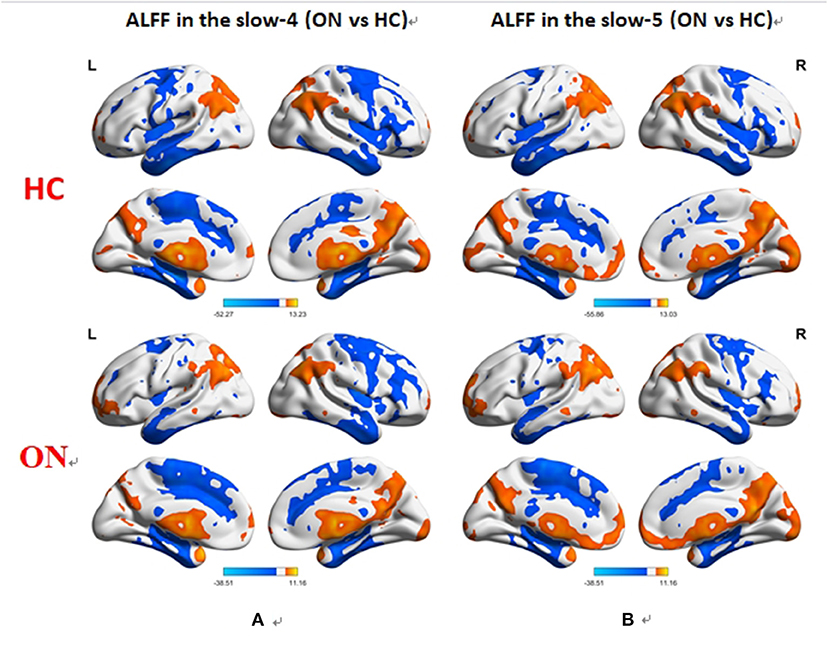

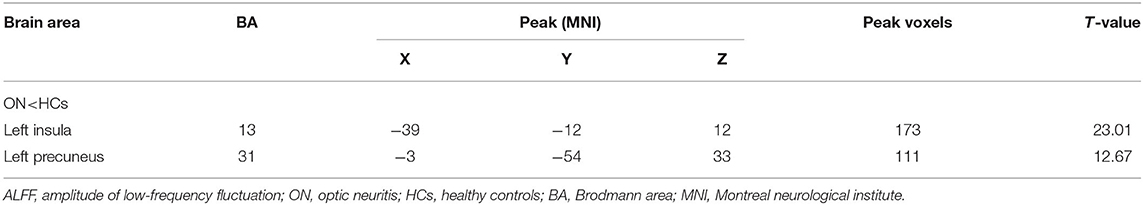

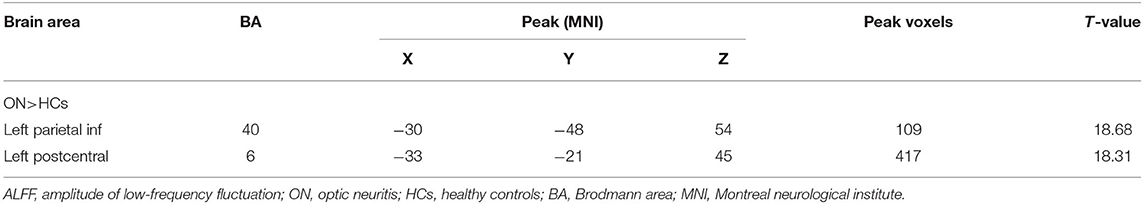

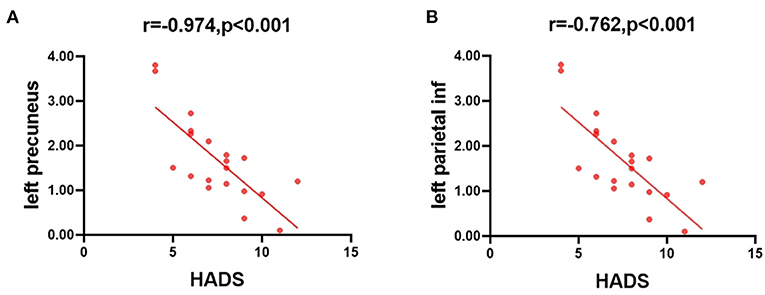

No bidirectional changes were detected by post hoc t-tests in ALFF across slow-4 and slow-5 frequencies. Significantly lower ALFF values were found in the left insula and the left precuneus in the slow-4 band, but significantly higher ALFF values in the left parietal inf and the left postcentral in the slow-5 band (Figure 3; Tables 3, 4). The mean ALFF values between the ON patients and HCs are represented in Figure 4.

Figure 3. Difference in the ALFF values in the brain between the ON and HC groups across slow-4 (A) and slow-5 (B) frequencies, with Gaussian random field theory correction, voxel-level P < 0.01 and cluster-level P < 0.05. Compared with HC, red represents the brain areas with increased AlFF, and blue represents the brain areas with decreased AlFF in patients with ON. ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation; ON, optic neuritis; L, left; HC, healthy control; R, right.

Table 3. In the slow-4 band (0.027–0.073 Hz), ALFF differences between the PHN and HC groups with Gaussian random field theory correction, voxel-level P < 0.01 and cluster-level P < 0.05.

Table 4. In the slow-5 band (0.001–0.027 Hz), ALFF differences between the PHN and HC groups with Gaussian random field theory correction, voxel-level P < 0.01 and cluster-level P < 0.05.

Figure 4. The mean ALFF values of altered brain regions between the ON and HCs. ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation; ON, optic neuritis; HCs, healthy controls.

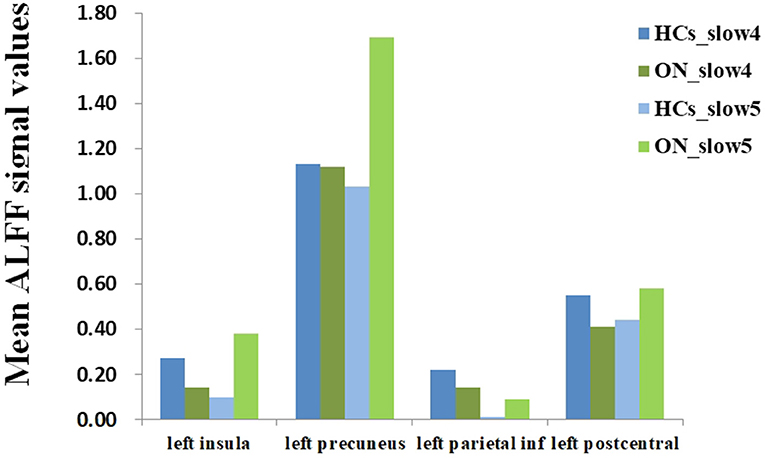

In the patients with ON, the mean HADS scores negatively correlated with the ALFF values of the slow-4 band in the left precuneus (r = −0.974, P < 0.001), and in the left parietal inf (r = −0.762, P < 0.001) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Correlations between the mean ALFF values and the clinical behaviors. (A) The HADS scores showed a negative correlation with the ALFF value of the slow-4 band in the left precuneus (r = −0.974, P < 0.001), and (B) the HADS scores showed a negative correlation with the ALFF value of the slow-4 band in the left parietal inf (r = −0.762, P < 0.001). ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation; HADS, hospital anxiety and depression scale.

ALFF is a common clinical method reflecting the relationship between various clinical diseases and corresponding brain regions, as shown by many previous studies (Table 5).

ALFF values were significantly higher in ON patients than HCs in the right cerebellum, the right temporal inf, the left temporal inf, and the left parietal inf, and lower than HCs in the left cingulum ant and the right cingulum ant.

The cerebellum is responsible for balance, cognitive tasks and motor control. We have shown using fMRI that the cerebellum is involved in cognition and memory (21). Previous studies have linked cerebellar dysfunction to schizophrenia (22), bipolar disorder (23), and depression (24) and demonstrated higher cerebellar activation in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (MS) than in healthy controls (25–27). Similarly, we found that the ALFF value of the right cerebellum is higher in ON patients than in controls, which may reflect functional compensation for neural damage. In the resting state, the default model network (DMN) is continuously activated in the brain and is associated with many conscious activities (28–32). In about 20% of MS patients, ON is the most important clinical feature (33). Previous research has shown (34) that DMN connectivity of the anterior cingulate cortex of MS is weaker than in controls and that the converse is true in the posterior cingulate cortex, with relatively strong connectivity in MS. In line with these findings, the present study found decreased ALFF in patients with ON in the bilateral cingulum ant and left precuneus, and increased ALFF in the bilateral temporal inf and left parietal inf. ALFF may play vital roles in understanding functional reorganization in ON patients. Therefore, changes in the ALFF values of the bilateral cingulate gyrus and the left anterior gyrus may be explained by the DMN damage caused by ON, and the abnormalities of the bilateral temporal lobe and left parietal lobe inf may be related to the stability of the network.

Higher ALFF was found at slow-5 than at slow-4 frequency range in the right rectus, and right occipital sup and the converse, with lower ALFF at slow-5 than at slow-4, in the left caudate and left temporal pole sup. Various neurophysiological mechanisms give rise to a range of oscillatory bands with a correspondingly wide range of physiological functions (35). Consistent with previous studies, we found abnormal amplitudes in the frontal, occipital and parietal cortex in ON (35), with the slow 4 range dominating the ventral prefrontal cortex (36).

We found bidirectional changes of ALFF both in the ON and HC groups across slow-4 and slow-5 frequency bands, providing new insight into frequency-dependent alterations of ON patients. Excessively secondary to ALFF decreased in insula and the punch precuneus gyrus in the slow-4 band, but ALFF values were seriously upper in the awaken parietal inf and the talk area over postcentral gyrus in the slow-5 band.

The insula is located in the depths of the lateral sulcus, (37) is anatomically related to the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes (38) and plays vital roles in consciousness, bodily impulses, and in controlling and suppressing natural impulses (39, 40). Insular dysfunction has also been linked to diseases including Alzheimer's disease (41) and epilepsy (42). Previous studies have demonstrated abnormal activation of the insula in ON patients (43, 44). Based on these findings, we infer that ON may be involved in insula dysfunction.

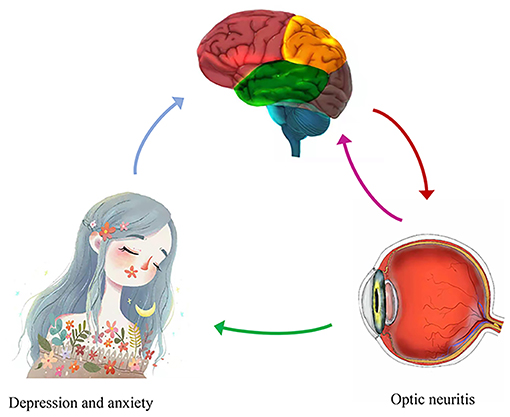

Brain regions are associated with the DMN (45). It is increasingly evident that DMN vulnerability plays an important part in depression and anxiety (46). The present study found lower ALFF in the left precuneus in patients with ON which indicates that ON might lead to DMN damage (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Correlations between mean ALFF values and behavioral performance. Compared with the HCs, the ALFF value of the left precuneus was decreased in ON. And the patients with ON exhibited with more depression and anxiety. ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation; HCs, healthy controls; ON, optic neuritis.

The subparietal lobule participates in visual recognition (47). It is also related to diseases such as schizophrenia (48) and Alzheimer's disease (49). In our study, abnormality of left parietal atrial fibrillation in patients with ON may reflect compensation for abnormal visual function.

Located in the primary somatosensory cortex, the postcentral gyrus is associated with information processing triggered by tactile stimulation (50). The primary somatosensory cortex is involved in the perception of pain (51). Previous research has demonstrated reduced white matter in the postcentral gyrus in patients with neuromyelitis optical (52). In addition, the sensorimotor system of patients with optic neuromyelitis is impaired (53). In the present study, we demonstrated increased ALFF values in the left postcentral gyrus in patients with ON, which may reflect compensation for sensorimotor dysfunction (Table 6).

Our research has limitations. First, the sample size is relatively small. In addition, the correlation between clinical characteristics of ON and ALFF values require further investigation. Thus, we are looking forward to designing more experiments to further elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms.

In summary, our study reveals abnormal spontaneous activities in regional brain areas in ON, and may provide insight into the underlying pathogenetic mechanism.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, and all methods were applied in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

KY, Y-CP, and W-QS performed the experiments and collected the data. TS, X-LL, and L-JZ designed the current study. S-NW, Q-YL, H-YS, JY, and YS given final approval of the version to be published. KY wrote the manuscript. All authors made substantial contributions to this research, read, and approved the final manuscript.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81660158, 81160118, 81400372, 81460092, and 81500742), Natural Science research Foundation of Guangdong Province (Nos. 2017A030313614, 2017A020215187, and 2018A030313117), and Medical Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. A2016184).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer HL declared a shared parent affiliation with several of the authors, W-QS, S-NW, Q-YL, H-YS, L-JZ, Y-CP and YS at the time of review.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Beck RW, Gal RL. Treatment of acute optic neuritis: a summary of findings from the optic neuritis treatment trial. Arch Ophthalmol. (2008) 126:994–5. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.7.994

2. Vedula SS, Brodney-Folse S, Gal RL, Beck R. Corticosteroids for treating optic neuritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2007) 24:CD001430. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001430.pub2

3. Wakakura M, Ishikawa S, Oono S, Tabuchi A, Kani K, Tazawa Y, et al. [Incidence of acute idiopathic optic neuritis and its therapy in Japan. Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial Multicenter Cooperative Research Group (ONMRG)]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. (1995) 99:93–7.

4. MacDonald BK, Cockerell OC, Sander JW, Shorvon SD. The incidence and lifetime prevalence of neurological disorders in a prospective community-based study in the UK. Brain. (2000) 123:665–76. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.4.665

5. Wilhelm H, Schabet M. The diagnosis and treatment of optic neuritis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. (2015) 112:616–25. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0616

6. Keltner JL, Johnson CA, Cello KE, Dontchev M, Gal RL, Beck RW, et al. Optic Neuritis Study, Visual field profile of optic neuritis: a final follow-up report from the optic neuritis treatment trial from baseline through 15 years. Arch Ophthalmol. (2010) 128:330–7. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.16

7. Morrow MJ, Wingerchuk D. Neuromyelitis optica. J Neuroophthalmol. (2012) 32:154–66. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e31825662f1

8. Brown HD, Woodall RL, Kitching RE, Baseler HA, Morland AB. Using magnetic resonance imaging to assess visual deficits: a review. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. (2016) 36:240–65. doi: 10.1111/opo.12293

9. Foubert L, Bennequin D, Thomas MA, Droulez J, Milleret C. Interhemispheric synchrony in visual cortex and abnormal postnatal visual experience. Front Biosci. (2010) 15:681–707. doi: 10.2741/3640

10. Mima T, Oluwatimilehin T, Hiraoka T, Hallett M. Transient interhemispheric neuronal synchrony correlates with object recognition. J Neurosci. (2001) 21:3942–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-11-03942.2001

11. Biswal BB, Resting state fMRI: a personal history. Neuroimage. (2012) 62:938–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.090

12. Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2007) 8:700–11. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201

13. Huang X, Zhong YL, Zeng XJ, Zhou F, Liu XH, Hu PH, et al. Disturbed spontaneous brain activity pattern in patients with primary angle-closure glaucoma using amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation: a fMRI study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2015) 11:1877–83. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S87596

14. Tan G, Huang X, Zhang Y, Wu AH, Zhong YL, Wu K, et al. A functional MRI study of altered spontaneous brain activity pattern in patients with congenital comitant strabismus using amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2016) 12:1243–50. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S104756

15. Li Q, Huang X, Ye L, Wei R, Zhang Y, Zhong YL, et al. Altered spontaneous brain activity pattern in patients with late monocular blindness in middle-age using amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation: a resting-state functional MRI study. Clin Interv Aging. (2016) 11:1773–80. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S117292

16. Shi WQ, Wu W, Ye L, Jiang N, Liu WF, Shu YQ, et al. Altered spontaneous brain activity patterns in patients with corneal ulcer using amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation: an fMRI study. Exp Ther Med. (2019) 18:125–32. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7550

17. Kang HH, Shu YQ, Yang L, Zhu PW, Li D, Li QH, et al. Measuring abnormal intrinsic brain activities in patients with retinal detachment using amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation: a resting-state fMRI study. Int J Neurosci. (2019) 129:681–6. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2018.1554657

18. Pan ZM, Li HJ, Bao J, Jiang N, Yuan Q, Freeberg S, et al. Altered intrinsic brain activities in patients with acute eye pain using amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation: a resting-state fMRI study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2018) 14:251–7. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S150051

19. Wu YY, Yuan Q, Li B, Lin Q, Zhu PW, Min YL, et al. Altered spontaneous brain activity patterns in patients with retinal vein occlusion indicated by the amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Exp Ther Med. (2019) 18:2063–71. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7770

20. Gao L, Bai L, Zhang Y, Dai XJ, Netra R, Min Y, et al. Frequency-dependent changes of local resting oscillations in sleep-deprived brain. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0120323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120323

21. Desmond JE, Fiez JA. Neuroimaging studies of the cerebellum: language, learning and memory. Trends Cogn Sci. (1998) 2:355–62. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(98)01211-X

22. Andreasen NC, Paradiso S, O'Leary DS. “Cognitive dysmetria” as an integrative theory of schizophrenia: a dysfunction in cortical-subcortical-cerebellar circuitry? Schizophr Bull. (1998) 24:203–18. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033321

23. Baldacara L, Nery-Fernandes F, Rocha M, Quarantini LC, Rocha GG, Guimaraes JL, et al. Is cerebellar volume related to bipolar disorder? J Affect Disord. (2011) 135:305–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.059

24. Bledsoe JC, Semrud-Clikeman M, Pliszka SR. Neuroanatomical and neuropsychological correlates of the cerebellum in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder–combined type. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2011) 50:593–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.02.014

25. Saini S, DeStefano N, Smith S, Guidi L, Amato MP, Federico A, et al. Altered cerebellar functional connectivity mediates potential adaptive plasticity in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2004) 75:840–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.016782

26. Ceccarelli, Rocca MA, Valsasina P, Rodegher M, Falini A, Comi G, et al. Structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging correlates of motor network dysfunction in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurosci. (2010) 31:1273–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07147.x

27. Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2005) 102:9673–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102

28. Spreng RN, DuPre E, Selarka D, Garcia J, Gojkovic S, Mildner J, et al. Goal-congruent default network activity facilitates cognitive control. J Neurosci. (2014) 34:14108–14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2815-14.2014

29. Andreescu C, Wu M, Butters MA, Figurski J, Reynolds CF 3rd, Aizenstein HJ. The default mode network in late-life anxious depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2011) 19:980–3. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318227f4f9

30. Yao N, Shek-Kwan Chang R, Cheung C, Pang S, Lau KK, Suckling J, et al. The default mode network is disrupted in Parkinson's disease with visual hallucinations. Hum Brain Mapp. (2014) 35:5658–66. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22577

31. Vergara EF, Behrens MI. [Default mode network and Alzheimer's disease]. Rev Med Chil. (2013) 141:375–80. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872013000300014

32. Meda SA, Ruano G, Windemuth A, O'Neil K, Berwise C, Dunn SM, et al. Multivariate analysis reveals genetic associations of the resting default mode network in psychotic bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2014) 111:E2066–75. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313093111

33. Lee JY, Han J, Yang M, Oh SY. Population-based Incidence of Pediatric and Adult Optic Neuritis and the Risk of Multiple Sclerosis. Ophthalmology. (2020) 127:417–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.09.032

34. Bonavita S, Gallo A, Sacco R, Corte MD, Bisecco A, Docimo R, et al. Distributed changes in default-mode resting-state connectivity in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. (2011) 17:411–22. doi: 10.1177/1352458510394609

35. Buzsaki G, Draguhn A. Neuronal oscillations in cortical networks. Science. (2004) 304:1926–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1099745

36. Zuo XN, Di Martino A, Kelly C, Shehzad ZE, Gee DG, Klein DF, et al. The oscillating brain: complex and reliable. Neuroimage. (2010) 49:1432–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.037

37. Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ. Insula of the old world monkey. III: Efferent cortical output and comments on function. J Comp Neurol. (1982) 212:38–52. doi: 10.1002/cne.902120104

38. Ebisch SJ, Bello A, Spitoni GF, Perrucci MG, Gallese V, Committeri G, et al. Emotional susceptibility trait modulates insula responses and functional connectivity in flavor processing. Front Behav Neurosci. (2015) 9:297. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00297

39. Naqvi NH, Rudrauf D, Damasio H, Bechara A. Damage to the insula disrupts addiction to cigarette smoking. Science. (2007) 315:531–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1135926

40. Lerner, Bagic A, Hanakawa T, Boudreau EA, Pagan F, Mari Z, et al. Involvement of insula and cingulate cortices in control and suppression of natural urges. Cereb Cortex. (2009) 19:218–23. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn074

41. Hayata TT, Bergo FP, Rezende TJ, Damasceno A, Damasceno BP, Cendes F, et al. Cortical correlates of affective syndrome in dementia due to Alzheimer's disease. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. (2015) 73:553–60. doi: 10.1590/0004-282X20150068

42. Dylgjeri S, Taussig D, Chipaux M, Lebas A, Fohlen M, Bulteau C, et al. Insular and insulo-opercular epilepsy in childhood: an SEEG study. Seizure. (2014) 23:300–8. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2014.01.008

43. Toosy AT, Werring DJ, Bullmore ET, Plant GT, Barker GJ, Miller DH, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of the cortical response to photic stimulation in humans following optic neuritis recovery. Neurosci Lett. (2002) 330:255–9. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00700-0

44. Werring DJ, Bullmore ET, Toosy AT, Miller DH, Barker GJ, MacManus DG, et al. Recovery from optic neuritis is associated with a change in the distribution of cerebral response to visual stimulation: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2000) 68:441–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.4.441

45. Liu Y, Li L, Li B, Feng N, Li L, Zhang X, et al. Decreased triple network connectivity in patients with recent onset post-traumatic stress disorder after a single prolonged trauma exposure. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:12625. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12964-6

46. Vicentini JE, Weiler M, Almeida SRM, de Campos BM, Valler L, Li LM. Depression and anxiety symptoms are associated to disruption of default mode network in subacute ischemic stroke. Brain Imaging Behav. (2017) 11:1571–80. doi: 10.1007/s11682-016-9605-7

47. Sliwinska MW, James A, Devlin JT. Inferior parietal lobule contributions to visual word recognition. J Cogn Neurosci. (2015) 27:593–604. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00721

48. Danivas V, Kalmady S, Arasappa R, Behere RV, Rao NP, Venkatasubramanian G, et al. Inferior parietal lobule volume and schneiderian first-rank symptoms in antipsychotic-naive schizophrenia: a 3-tesla MRI study. Indian J Psychol Med. (2009) 31:82–7. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.63578

49. Reed TT, Pierce WM Jr, Turner DM, Markesbery WR D, Allan butterfield. proteomic identification of nitrated brain proteins in early Alzheimer's disease inferior parietal lobule. J Cell Mol Med. (2009) 13:2019–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00478.x

50. Guic E, Carrasco X, Rodriguez E, Robles I, Merzenich MM. Plasticity in primary somatosensory cortex resulting from environmentally enriched stimulation and sensory discrimination training. Biol Res. (2008) 41:425–37. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602008000400008

51. Kim W, Kim SK, Nabekura J. Functional and structural plasticity in the primary somatosensory cortex associated with chronic pain. J Neurochem. (2017) 141:499–506. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14012

52. Duan Y, Liu Y, Liang P, Jia X, Ye J, Dong H, et al. White matter atrophy in brain of neuromyelitis optica: a voxel-based morphometry study. Acta Radiol. (2014) 55:589–93. doi: 10.1177/0284185113501815

Keywords: amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation, optic neuritis, resting state, functional magnetic resonance imaging, slow 5 and slow 4 frequencies

Citation: Yan K, Shi W-Q, Su T, Liao X-L, Wu S-N, Li Q-Y, Yu J, Shu H-Y, Zhang L-J, Pan Y-C and Shao Y (2022) Brain Activity Changes in Slow 5 and Slow 4 Frequencies in Patients With Optic Neuritis: A Resting State Functional MRI Study. Front. Neurol. 13:823919. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.823919

Received: 28 November 2021; Accepted: 13 January 2022;

Published: 21 February 2022.

Edited by:

Yuzhen Xu, Tongji University, ChinaReviewed by:

Haijun Li, Nanchang University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Yan, Shi, Su, Liao, Wu, Li, Yu, Shu, Zhang, Pan and Shao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yi Shao, ZnJlZWJlZTk5QDE2My5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.