- 1Department of Neurology, Epilepsy Center, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China

- 2Nursing Department, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China

- 3Department of General Practice and International Medicine, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China

- 4Key Laboratory of Medical Molecular Imaging of Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou, China

Objective: We aimed to evaluate the knowledge of the board members of the Zhejiang Association Against Epilepsy (ZAAE) regarding pregnancy of women with epilepsy (WWE), as well as their clinical practice and obstacles in the management of WWE.

Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted among the board members of the ZAAE using a questionnaire based on the management guidelines for WWE during pregnancy in China. We recorded the demographic characteristics of the surveyed practitioners, the coincidence rate of each question, clinical practice, and the barriers encountered in managing WWE.

Results: This survey showed that the average knowledge score of the surveyed practitioners was 71.02%, and the knowledge score of neurologists was higher than that of neurosurgeons. Knowledge regarding the following three aspects was relatively poor: whether WWE is associated with an increased risk of cesarean section and preterm delivery, the preferred analgesic drugs for WWE during delivery, and the time of postpartum blood concentration monitoring. After multiple linear regression analysis, the score of neurologists was correlated to the number of pregnant WWE treated each year. In addition, the biggest difficulty in the management of WWE during pregnancy is the lack of patient education and doctors training on pregnant epilepsy management.

Conclusion: Our study revealed the ZAAE board members' knowledge and management status of pregnant WWE. In addition, our study identified the biggest obstacle to the management of WWE during pregnancy, and emphasized the importance of training and practice of epilepsy knowledge during pregnancy for practitioners and the significance of interdisciplinary communication.

Introduction

Epilepsy is one of the most common chronic diseases affecting women of childbearing age (1), with ~0.2 to 0.5% of all pregnant women having a history of epilepsy (2). Most pregnant women with epilepsy (WWE) could have healthy offspring, however, complications that impact maternal and fetal health can occur (3). For example, the risk of teratogenesis caused by anti-seizure medications (ASMs), exacerbation of seizures during pregnancy, and pregnancy related depression (4–6). Although WWE are at risk during pregnancy, previous studies have shown that WWE have unsatisfactory understanding of pregnancy-related epilepsy problems, and health care providers lack comprehensive knowledge of the management of WWE during pregnancy (7–9).

Awareness and adequate counseling of management issues in WWE are key components of patient care. After the release of the UK guidelines for the management of WWE (10), a study suggested that pre-pregnancy counseling might reduce the frequency of adverse outcomes, such as major congenital malformations (10–14). Metcalfe et al. (15) found that patients did not know enough about the new guidelines for pregnancy of WWE established by the American Academy of Neurology. Currently, guidelines for the management of pregnant WWE have been published in China (16); however, the situation regarding practitioners' management of WWE during pregnancy is not clear. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to evaluate practitioners' management of WWE during pregnancy. This information is essential to ensure the highest quality of care for WWE, because it identifies deficiencies in practitioner knowledge that must be addressed.

Methods

Survey

This is a cross-sectional study of the board members of the Zhejiang Association Against Epilepsy (ZAAE), a branch of the China Association Against Epilepsy (CAAE). These board members represent the doctors who mainly treat epilepsy in the whole Zhejiang Province. The ZAAE has 76 board members, including a retired consultant, a neuroscientist, and three electroencephalogram (EEG) technicians, all five of whom who were not included in the survey. Seventy-one board members were recruited in the study. Board members were emailed with an invitation and link to the electronic questionnaire. From April 1 to April 7, 2022, we alerted the participants via WeChat or telephone.

Participants were eligible if they were: a professional who were currently engaged in clinical work related to epilepsy; and provided informed consent. The study was approved by the Second Affiliated hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine Ethics Committee.

Questionnaire

A questionnaire comprising 41 items was constructed by two epileptologists (Mei-Ping Ding and Yi Guo), based on the management guidelines for WWE during pregnancy in China (16), modified on the basis of Nathalie Jetté's and Makiko Egawa's questionnaires (7, 17). This questionnaire emphasized knowledge of pregnancy-related risks associated with the use of specific ASMs. Two types of questions were used: single-choice and multiple-choice questions. The questionnaire included 20 questions about practitioners' understanding of the guidelines, and 21 questions related to the demographic characteristics of the practitioners and the practice and barriers in the clinical management of WWE. The questionnaire was designed to take no more than 10–15 min to complete.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze all variables. The knowledge score was expressed as the percentage of answers that met guidelines' recommendations among the 20 questions in Table 2, thus excluding demographic issues as well as practices and barriers in the clinical management of WWE during pregnancy. The calculation method was to set a weight of 1 to each answer that met guideline's recommendations in single-choice questions and multiple-choice questions respectively, and divided the number of answers that met guideline's recommendations given by the practitioners by the total number of answers that met guideline's recommendations in the questionnaire.

We used the knowledge score as a continuous variable to analyze the linear relationship between demographic characteristics and knowledge score. After the multiple sample Shapiro-Wilk test, the scores were normally distributed, so the parametric test was used. Firstly, we analyzed the variables one-by-one using an independent sample T-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Then, we entered all variables that were significantly associated with the outcome (P < 0.05) into a multiple linear regression analysis; a Chi-squared test was used to analyze the significant differences in demographic characteristics between neurologists and neurosurgeons, as well as each question whose cumulative coincidence rate was <70%. The Supplementary Table 7 containing information on how variables are coded and the presentation of sociodemographic variables are provided as Supplementary material. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. IBM SPSS Statistics program version 25 was used for the analyses (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

A total of 62 out of 71 practitioners finally completed the survey, with a response rate of 87.32%.

Practitioners' demographics

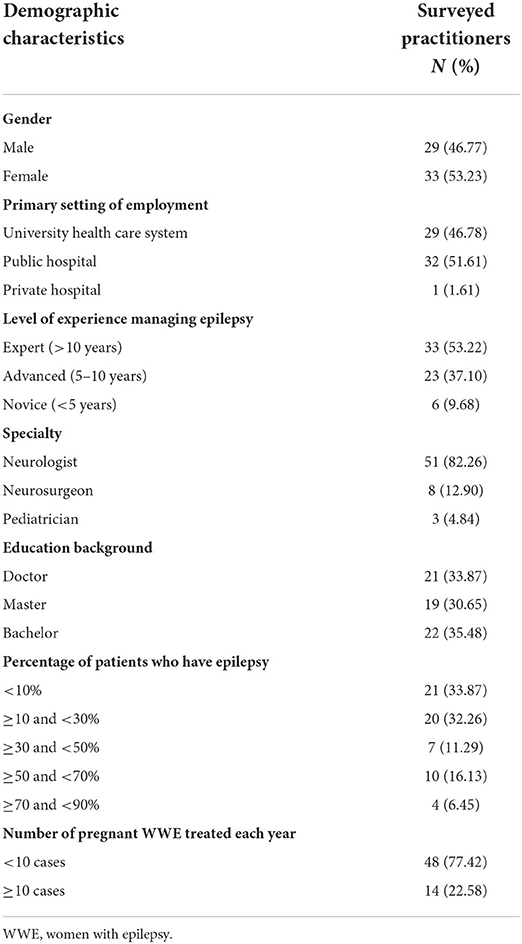

As shown in Table 1, 53.23% (n = 33) of the surveyed practitioners were female, and most of the surveyed practitioners worked in the university health care system (n = 29; 46.78%) and public hospitals (n = 32; 51.61%). Among the practitioners, 33.87% (n = 21) had a doctorate and 30.65% (n = 19) had a master's degree. Neurologists accounted for 82.26% (n = 51) of the practitioners. More than half of the practitioners (n = 33; 53.22%) had more than 10 years of experience in treating epilepsy. Most practitioners (n = 41; 66.13%) treated <30% of patients with epilepsy. Moreover, the majority of the practitioners (n = 48; 77.42%) treated fewer than ten cases of pregnant WWE every year.

Practitioners' knowledge of pregnancy management of WWE

Management during pre-pregnancy and pregnancy

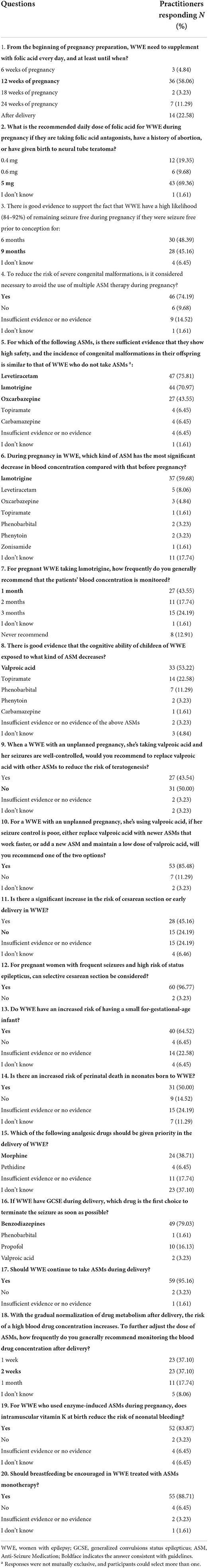

The average knowledge score of the surveyed practitioners was 71.02%. As displayed in Table 2, over half of the practitioners knew the duration of folic acid supplementation in WWE (n = 36; 58.06%) and the dose of folic acid supplementation (n = 43; 69.35%). Compared with the 48.39% (n = 30) of the practitioners who believed that there was a high likelihood of maintaining seizure free status during pregnancy if WWE were seizure free prior to conception for 6 months, only 45.16% (n = 28) of the practitioners realized that was 9 months. The majority of the practitioners (n = 46; 74.19%) answered that it was necessary to avoid the use of multiple ASMs during pregnancy. Most practitioners knew that levetiracetam (n = 47; 75.81%) and lamotrigine (n = 44; 70.97%) had sufficient evidence of high safety, whereas only 43.55% (n = 27) knew that oxcarbazepine also showed high safety. Among the practitioners, 59.68% (n = 37) knew that the blood concentration of lamotrigine decreased most significantly during pregnancy compared with that before pregnancy. For pregnant WWE taking lamotrigine, only 43.55% (n = 27) of the practitioners suggested blood concentration monitoring within 1 month. About half of the practitioners (n = 33; 53.22%) knew that there was good evidence that valproate (VPA) could cause cognitive decline in the offspring. Nearly half of the practitioners (n = 27; 43.54%) believed that women who were using VPA and had an unplanned pregnancy needed to replace valproic acid with other ASMs to reduce the risk of teratogenesis, even if their seizures were well-controlled. Most (n = 53; 85.48%) practitioners chose that if the seizure was poorly controlled, they needed to replace VPA with newer ASMs that work faster, or add new ASMs and maintain a relatively low dose VPA.

Management during childbirth

As shown in Table 2, only a few practitioners (n = 15; 24.19%) understood that WWE did not have a significantly increased risk of cesarean section or early delivery. Almost all practitioners (n = 60; 96.77%) comprehended that selective cesarean section could be considered for WWE with frequent seizures and high risk of epileptic status, and 64.52% (n = 40) knew that WWE had an increased risk of having a small for-gestational-age infant. Only 50% (n = 31) believed that there was an increased risk of perinatal death in neonates born to WWE. Less than half of the practitioners (n = 24; 38.71%) knew that morphine was the preferred analgesic drug during childbirth of WWE. Among the practitioners, 79.03% (n = 49) knew that benzodiazepines were the first choice to terminate the seizure as soon as possible when WWE had generalized convulsions status epilepticus (GCSE) during delivery, and 95.16% (n = 59) knew that they should continue to take ASMs during delivery.

Management after childbirth

As described in Table 2, only 37.10% (n = 23) of the practitioners knew that it was recommended to monitor the blood drug concentration for 2 weeks after delivery. Most practitioners (n = 52; 83.87%) knew that for WWE who used enzyme-induced ASMs during pregnancy, intramuscular vitamin K at birth would reduce the risk of neonatal bleeding, and 88.71% (n = 55) practitioners recommended that breastfeeding should be encouraged for WWE treated with ASM monotherapy.

Management practices and barriers in epilepsy during pregnancy

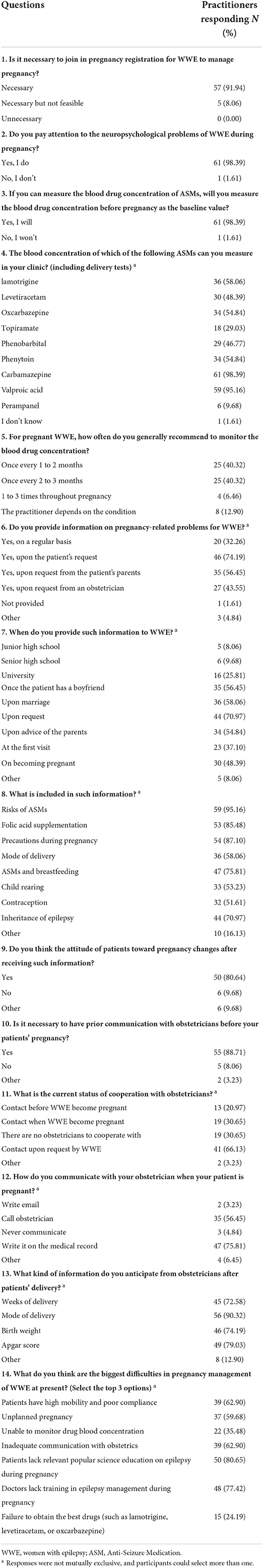

As shown in Table 3, most practitioners (n = 57; 91.94%) believed that it was necessary to join pregnancy registration for WWE to manage their pregnancy. Among the practitioners, 98.39% (n = 61) would pay attention to the neuropsychological problems of WWE during pregnancy and measure the blood drug concentration before pregnancy. The most commonly measured blood drug concentrations of ASMs were carbamazepine (n = 61; 98.39%) and VPA (n = 59; 95.16%). Among the practitioners, the same percentage, 40.32% (n = 25), suggested monitoring the blood drug concentration once every 1 to 2 months and once every 2 to 3 months, respectively. The majority of practitioners (n = 46; 74.19%) would provide information on pregnancy-related problems when requested by patients. The most information provided was related to the risk of ASMs (n = 59; 95.16%), followed by precautions during pregnancy (n = 54; 87.1%) and folic acid supplementation (n = 53; 85.48%). When WWE received information about pregnancy-related problems, 80.64% (n = 50) of practitioners thought that their attitude toward pregnancy had changed. Although 88.71% (n = 55) of practitioners considered it necessary to communicate with an obstetrician before WWE became pregnant, only 20.97% (n = 13) currently cooperated with obstetricians before conception. Communicating with obstetricians through medical records was the choice of 75.81% (n = 47) of the practitioners, and most of them wanted to receive information about the mode of delivery from the obstetricians. At present, practitioners believe that the biggest difficulty in the management of WWE during pregnancy is the lack of patient education related to epilepsy during pregnancy (n = 50; 80.65%), followed by the lack of training for the management of epilepsy during pregnancy (n = 48; 77.42%).

Variables related to practitioners' knowledge

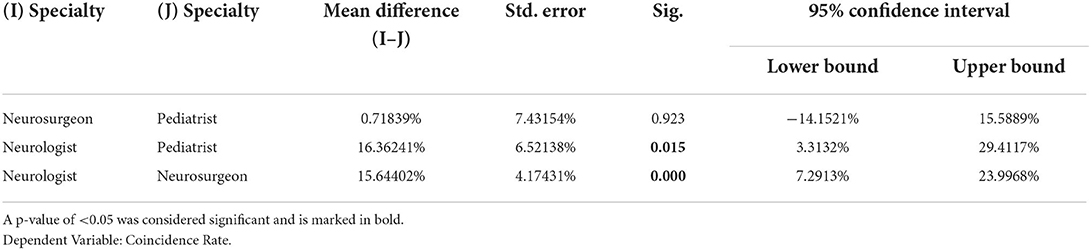

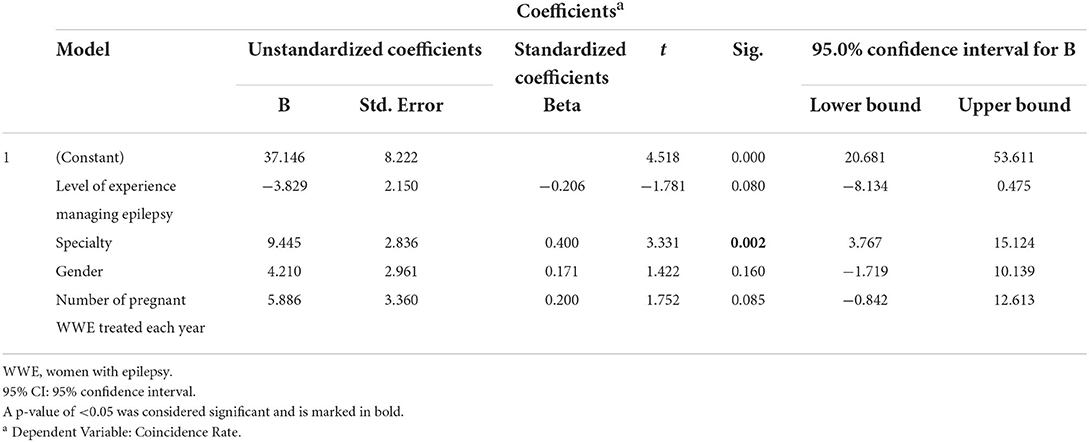

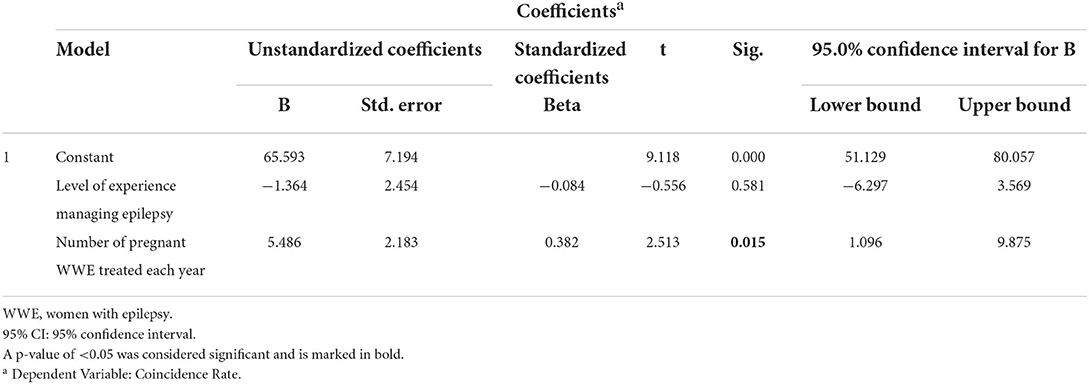

To determine whether the demographic characteristics of the practitioners affected the knowledge score, we further conducted difference analysis and regression analysis. The knowledge scores were statistically significant among four aspects: Gender (P = 0.014), levels of experience in treating epilepsy (P = 0.045), the number of P pregnant WWE treated each year (P = 0.008), and specialty (P < 0.001) (data were shown in Supplementary material). After incorporating the above four variables into the multiple linear regression model, we found that specialty (p = 0.002; 9.45, 95% CI 3.77 to 15.12) (Table 4) was a relevant factor of practitioners' knowledge, with statistical significance between neurologists and neurosurgeons (P < 0.001; 73.83 ± 11.23% vs. 58.19 ± 10.33%; 15.64%, 95% CI 7.29 to 24.00%) and between neurologists and pediatricians (P = 0.015, 73.83 ± 11.23% vs. 57.47 ± 5.27%; 16.36%, 95% CI 3.31 to 29.41%) (Table 5). In addition, we also conducted difference analysis and regression analysis on neurologists alone. We added the level of treatment experience (P = 0.002) and the number of pregnant WWE treated annually (P = 0.013) to the multiple linear regression. As displayed in Table 6, we found that the number of pregnant WWE treated annually was a relevant factor of neurologists ' knowledge (P = 0.015; 5.49, 95% CI 1.10 to 9.88).

Table 4. Independent correlates of practitioners' knowledge after multivariate linear regression analysis.

Table 6. Independent correlates of neurologists ' knowledge after multivariate linear regression analysis.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this was the first survey to evaluate the pregnancy management of WWE among practitioners in China. We found that the average knowledge score of the board members of ZAAE was only 71.02%, and the issue with the lowest coincidence rate was whether the risk of cesarean section or early delivery is increased in WWE. The biggest obstacle to the management of WWE during pregnancy was that patients lack relevant education on epilepsy during pregnancy and doctors lack training in epilepsy management during pregnancy. Multiple linear regression analysis showed the knowledge score of neurologists was statistically higher than that of neurosurgeons and pediatricians, respectively. Furthermore, the neurologist's knowledge score correlated significantly with the number of pregnant WWE treated each year.

The average knowledge score of the board members of ZAAE was 71.02% in our study, which was higher than the survey of from Jetté's group (49.3%) (7). This discrepancy might be partly caused by the type of respondents included in each study, the study by Jetté's group included neurologists and neurology residents, whereas most of the respondents in our study are professionals with clinical experience of epilepsy (90.32%). Another reason may be differences in the content of the questionnaires. Less than 70% of practitioners knew the duration and the dosage of folic acid supplementation in WWE, indicating a lack of knowledge on the rational use of folic acid in WWE. Actually, there is no real current evidence on the best dose of folic acid in case of previous abortions or folic acid antagonists in women with epilepsy. In the Chinese guidelines (16), a daily dose of 5 mg of folic acid is recommended as grade D based on experts opinions. Only 45.16% of practitioners knew that there was a high likelihood to remain seizure free during pregnancy if WWE were 9 months seizure-free before pregnancy, which was consistent with the survey by Jetté's group (20%) (7). On the contrary, 48.39% of practitioners chose 6 months without seizure before pregnancy, which was recommended by the consensus of Chinese experts in 2015 (18), this indicated that practitioners need to learn the new guidelines. In addition, practitioners had a relatively poor understanding of the issues related to childbirth in WWE. For example, less than half (38.71%) of the practitioners pointed out that morphine was preferred for analgesia during childbirth of WWE. Moreover, only a few practitioners (24.19%) knew that WWE did not have a significantly increased risk of cesarean section or early delivery, which was similar to the survey by Jetté's group (28.9%) (7). The above two conditions might be related to poor communication between epilepsy practitioners and obstetricians.

For medication-related issues, most practitioners pointed out that lamotrigine was considered a safer option and were aware of the change in plasma drug concentration during pregnancy. Nevertheless, less than half of the practitioners understood that oxcarbazepine also shows high safety, which might reflect the lower amount of evidence for oxcarbazepine compared with lamotrigine and levetiracetam. Most (83.87%) practitioners suggested that for WWE who used enzyme-induced ASM during pregnancy, intramuscular vitamin K at birth would reduce the risk of neonatal bleeding, which was similar to results described by Babiker et al. (74%) (19). About half (53.23%) of the practitioners knew that there was good evidence that VPA would reduce the offspring's cognitive ability, which was inconsistent with the study by Jetté's group (33.3%) (7). The discrepancy with our results could be related to different respondents, that more epilepsy professionals were enrolled in our study. Nearly half (43.55%) of practitioners believed that VPA needed to be replaced during pregnancy if their seizures were well-controlled, which was inconsistent with guideline's recommendation. Actually, it is not recommended to replace VPA temporarily during pregnancy in Chinese guidelines (a grade D recommendation). These findings suggested that practitioners did not accurately understand the risks of VPA to the offspring and did not balance the effects of VPA adjustment on seizures. Only 43.55% of practitioners knew that the recommended interval for blood concentration monitoring of lamotrigine after pregnancy was every month. 1 month was recommended in the latest Chinese guidelines (16), therefore, it is necessary for practitioners to update the knowledges. In addition, the frequency of monitoring blood concentrations is also associated with a lack of medical conditions, which may reflect difficulties in the implement.

In terms of management practice of pregnant WWE, we found that only a small number of respondents (32.26%) would regularly provide information on pregnancy for WWE, compared with most respondents (74.19%) who provided information at the request of patients. This might reflect inadequate doctor-patient communication in the clinic in China. Zelano's group designed an online tool for information to WWE, which enhanced patient education and improved communication during pregnancy for WWE (20). Our study also found that most WWE changed their attitude toward pregnancy after receiving pregnancy-related information. Therefore, we recommend that doctors regularly provide pregnancy-related information to WWE in clinic or online. Besides, although most doctors (88.71%) believed that it was necessary to communicate with obstetricians before pregnancy, only 20.97% currently cooperated with them, which might be explained by the lack of referrals in China's medical system. Almost all respondents wanted to know about the delivery mode of WWE from obstetricians, which further illustrated the necessity for communication (21).

The lack of patient education on epilepsy during pregnancy and the lack of training on pregnant epilepsy management by doctors were the biggest difficulties in pregnancy management of WWE. Borgelt et al. (22) found that a specialty pharmacist in the ambulatory care neurology team may enhance patient education efficacy, which emphasized the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration. An online course on epilepsy for primary care physicians in Latin America was shown to be a cost-effective course, with good retention and excellent approval rates (23). This suggests that we can develop an online course for Chinese practitioners to manage pregnant WWE.

After multiple linear regression analysis, it was found that neurologists' knowledge of WWE during pregnancy was better than that of neurosurgeons. These findings suggested that neurologists might pay more attention to the management of pregnant WWE, particularly the teratogenic effects of ASMs on offspring, which might be related to the fact that neurologists pay more attentions to pregnant WWE annually than neurosurgeons. Five out eight neurosurgeons (more than 63%) still treated WWE during pregnancy. Therefore, it is important to train neurosurgeons in the knowledge of epilepsy during pregnancy. There were differences between the neurologist's final score and the number of pregnant WWE treated each year, suggesting the importance of training and practice of epilepsy during pregnancy.

Limitations of this study were as follows: First, the respondents of this study were the members of the board of the ZAAE, representing Zhejiang Province, East of China, which cannot represent the other areas of China. Second, obstetricians, psychiatrists, and geneticists were not enrolled in our study. In fact, the management of pregnant WWE requires multidisciplinary participation (21, 24). Third, psychological counseling for pregnancy was not included in this study. As a matter of fact, peripartum depression and anxiety are the most common complications of pregnancy, which have a significant adverse impact on pregnancy outcome and child development (4). In the future, it is necessary to conduct a multi-regional and multi-disciplinary survey of WWE management in pregnancy, including pregnancy psychological issues.

Conclusion

Our study revealed the ZAAE board members' knowledge and management status of pregnant WWE. The knowledge in the following three aspects was relatively poor: whether the risk of cesarean section and preterm delivery in WWE was increased, the preferred analgesic drugs for WWE during delivery, and the time of postpartum blood concentration monitoring. In addition, our study also identified the biggest obstacle to the management of WWE during pregnancy. The results emphasized the importance of training and practice of epilepsy knowledge during pregnancy for practitioners and the significance of interdisciplinary communication.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

YG designed and analyzed the data. YG and Z-Y-RX drafted and edited the manuscript. YG, M-TC, PQ, and M-pD contributed to revising the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant number 81871010].

Conflict of interest

Author YG was the board member of ZAAE. M-pD was the president of ZAAE. This survey was supported by ZAAE.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2022.1001918/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Viale L, Allotey J, Cheong-See F, Arroyo-Manzano D, McCorry D, Bagary M, et al. Epilepsy in pregnancy and reproductive outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. (2015) 386:1845–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00045-8

2. Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, Craig J, Lindhout D, Sabers A, et al. Dose-dependent risk of malformations with antiepileptic drugs: an analysis of data from the EURAP epilepsy and pregnancy registry. Lancet Neurol. (2011) 10:609–17. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70107-7

3. McPherson JA, Harper LM, Odibo AO, Roehl KA, Cahill AG. Maternal seizure disorder and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2013) 208:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.01.048

4. Bjørk MH, Veiby G, Engelsen BA, Gilhus NE. Depression and anxiety during pregnancy and the postpartum period in women with epilepsy: a review of frequency, risks, and recommendations for treatment. Seizure. (2015) 28:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2015.02.016

5. Arfman IJ, Heijden EAW, Horst PGJ, Lambrechts DA, Wegner I, Touw DJ. Therapeutic drug monitoring of antiepileptic drugs in women with epilepsy before, during, and after pregnancy. Clin Pharmacokinet. (2020) 59:427–45. doi: 10.1007/s40262-019-00845-2

6. Tomson T, Battino D, Bromley R, Kochen S, Meador K, Pennell P, et al. Management of epilepsy in pregnancy: a report from the international league against epilepsy task force on women and pregnancy. Epileptic Disord. (2019) 21:497–517. doi: 10.1111/epi.16395

7. Roberts JI, Metcalfe A, Abdulla F, Wiebe S, Hanson A, Federico P, et al. Neurologists' and neurology residents' knowledge of issues related to pregnancy for women with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. (2011) 22:358–63. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.07.009

8. Bhat M, Ramesha KN, Nirmala C, Sarma PS, Thomas SV. Knowledge and practice profile of obstetricians regarding epilepsy in women in Kerala state. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. (2011) 14:169–71. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.85877

9. Lee SM, Nam HW, Kim EN, Shin DW, Moon HJ, Jeong JY, et al. Pregnancy-related knowledge, risk perception, and reproductive decision making of women with epilepsy in Korea. Seizure. (2013) 22:834–9. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2013.07.002

10. Crawford P. Best practice guidelines for the management of women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. (2005) 46:117–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00323.x

11. Rakitin A, Kurvits K, Laius O, Uuskula M, Haldre S. Pre-pregnancy counseling for women with epilepsy: can we do better? Epilepsy Behav. (2021) 125:108404. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.108404

12. Zhang YY, Song CG, Wang X, Jiang YL, Zhao JJ, Yuan F, et al. Clinical characteristics and fetal outcomes in women with epilepsy with planned and unplanned pregnancy: a retrospective study. Seizure. (2020) 79:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2020.05.011

13. Abe K, Hamada H, Yamada T, Obata-Yasuoka M, Minakami H, Yoshikawa H. Impact of planning of pregnancy in women with epilepsy on seizure control during pregnancy and on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Seizure. (2014) 23:112–6. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2013.10.003

14. Espinera AR, Gavvala J, Bellinski I, Kennedy J, Macken MP, Narechania A, et al. Counseling by epileptologists affects contraceptive choices of women with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. (2016) 65:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.08.021

15. Metcalfe A, Roberts JI, Abdulla F, Wiebe S, Hanson A, Federico P, et al. Patient knowledge about issues related to pregnancy in epilepsy: a cross-sectional study. Epilepsy Behav. (2012) 24:65–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.03.001

16. Xiao B, Zhou D. Guidelines for the management of women with epilepsy during pregnancy in China. Chin J Neurol. (2021) 54:539–44. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn113694-20201116-00879

17. Egawa M, Hara K, Ikeda M, Yoshida M. Questionnaire dataset: attitude of epileptologists and obstetricians to pregnancy among women with epilepsy. Data Brief. (2020) 31:105948. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.105948

18. Liao W, Wang X. Chinese expert consensus on the use of antiepileptic drugs in pregnant women. J Chin Physician. (2015) 17:969–71.

19. Elnaeim AK, Elnaeim MK, Babiker IB. Knowledge of women issues and epilepsy among doctors in Sudan. Epilepsy Behav. (2018) 84:79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.04.013

20. Lisovska K, Gustafsson E, Klecki J, Tranberg AE, Zelano J. An online tool for information to women with epilepsy and therapeutic drug monitoring in pregnancy: design and pilot study. Epilepsia Open. (2021) 6:339–44. doi: 10.1002/epi4.12473

21. Leach JP, Smith PE, Craig J, Cavanagh D, Duncan S, Kelso AR, et al. Epilepsy and pregnancy: for healthy pregnancies and happy outcomes. Suggestions for service improvements from the multispecialty UK epilepsy mortality group. Seizure. (2017) 50:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2017.05.004

22. Borgelt LM, Hart FM, Bainbridge JL. Epilepsy during pregnancy: focus on management strategies. Int J Womens Health. (2016) 8:505–17. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S98973

23. Carrizosa J, Braga P, Albuquerque M, Bogacz A, Burneo J, Coan AC, et al. Epilepsy for primary health care: a cost-effective Latin American e-learning initiative. Epileptic Disord. (2018) 20:386–95. doi: 10.1684/epd.2018.0997

Keywords: epilepsy, pregnancy, management, questionnaire, survey

Citation: Xu Z-Y-R, Qian P, Cai M-T, Ding M-p and Guo Y (2022) Management of epilepsy in pregnancy in eastern China: A survey from the Zhejiang association against epilepsy. Front. Neurol. 13:1001918. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1001918

Received: 24 July 2022; Accepted: 01 November 2022;

Published: 17 November 2022.

Edited by:

Carlo Di Bonaventura, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyReviewed by:

Tayseer Afifi, Islamic University of Gaza, PalestinePrashant Dongre, UCB Pharma, United States

Barbara Mostacci, IRCCS Institute of Neurological Sciences of Bologna (ISNB), Italy

Copyright © 2022 Xu, Qian, Cai, Ding and Guo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yi Guo, eWlndW9Aemp1LmVkdS5jbg==

Zheng-Yan-Ran Xu

Zheng-Yan-Ran Xu Ping Qian

Ping Qian Meng-Ting Cai

Meng-Ting Cai Mei-ping Ding1

Mei-ping Ding1 Yi Guo

Yi Guo