94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Neurol. , 11 January 2022

Sec. Epilepsy

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.813698

Objective: We aimed to determine the prevalence of social isolation and associated factors among adults with epilepsy in northeast China.

Methods: A cohort of consecutive patients with epilepsy (PWE) from the First Hospital of Jilin University (Changchun, China) was recruited. Demographic and clinical data for each patient were collected during a face-to-face interview. Social isolation was measured using the Berkman-Syme Social Network Index (SNI), and the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E) and Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory (QOLIE-31) were also administered. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to determine the factors associated with social isolation in PWE.

Results: A total of 165 patients were included in the final analysis. The mean SNI score was 2.56 (SD: 1.19), and 35 patients (21.2%) were socially isolated. In multivariate logistic regression analysis, higher depressive symptom levels (OR = 1.15, 95% CI: 1.003–1.318, P = 0.045) and poorer quality of life (OR = 0.967, 95% CI: 0.935–0.999, P = 0.047) emerged as independent factors associated with social isolation in PWE.

Conclusion: Social isolation is common and occurs in approximately one-fifth of PWE. Social isolation is significantly associated with depressive symptoms and poor quality of life in PWE. Patients need to be encouraged to actively integrate with others and reduce social isolation, which may help improve their quality of life.

Epilepsy is one of the most common serious brain diseases and affects more than 70 million individuals worldwide (1). Epilepsy has a profound long-term impact on various aspects of social life for patients, such as social anxiety (2), poor social support (3), perceived stigma (4), psychosocial burden (5), poor social adjustment (6), impaired social cognition (7), and lack of social skills and competence (8). These negative social aspects may lead to social isolation, which has yet to be fully investigated in adults with epilepsy.

Social isolation was defined as an objective lack or limitation of close personal ties to friends and family and social ties to the community (9, 10). Social isolation has been reported to be related to poor physical health and psychiatric conditions such as depressive symptoms (11–13). Psychiatric disorders have been identified as the most common comorbidities and one of the most important determinants of poor quality of life in patients with epilepsy (PWE) (14). Thus, social isolation may be associated with poor quality of life in PWE. Social isolation has also been reported as a significant risk factor for reduced well-being, cognitive decline, and mortality in the general population (15, 16). A previous cross-sectional study from India showed that children with epilepsy had significant social deficits and that boys with epilepsy had limited social integration (17). These results may be due to perceptions of being overprotected by their parents (18).

Studies on the topic of social isolation in adults with epilepsy are limited (19). Thus, the current study aimed to investigate the prevalence of social isolation and to identify associated factors in adults with epilepsy in northeast China. It was expected that social isolation would be associated with depressive symptoms and low quality of life in patients.

This research involved a cross-sectional study performed at The First Hospital of Jilin University, a large tertiary care hospital in Northeast China. Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of epilepsy (20) aged 18 years or older were invited to participate in the present study from May to July 2021. Participants were required to take a stable dose of antiseizure medications (ASMs) for at least 4 weeks. Participants were also required to have the physical, mental, and linguistic ability to complete self-report questionnaires and interviews adequately. We excluded individuals who had a severe brain disease other than epilepsy (e.g., dementia and Parkinson's disease), a serious physical disease (e.g., cancer, significant hepatic, or renal conditions), or psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia). Patients were also excluded if they were not willing to participate or did not provide written informed consent. The protocols of this study were approved by the ethics committee of our hospital, and each participant provided written informed consent stating his or her willingness to participate.

Each participant had a face-to-face interview with one trained clinician (HZ) who collected the data uniformly. A structured questionnaire was employed to collect demographic, socioeconomic, and epilepsy-related data during the interview. The demographic and socioeconomic information included age, gender, marital status, employment status, and education level. The epilepsy-related variables consisted of age at onset, epilepsy duration, epilepsy type, seizure frequency during the last 6 months, and ASM therapy regimen. Patients with a high education level were those who had a university education or above. Additionally, patients were requested to complete a series of questionnaires during the interview at our hospital. The Berkman-Syme Social Network Index (SNI), Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E), and Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory (QOLIE-31) were employed to assess social isolation, depression, and quality of life in patients, respectively.

The Berkman-Syme SNI was used to measure social isolation in PWE (21). This measure assessed social networks and had four self-reported subcomponents: married (no = 0; yes = 1); close friends and relatives (0–2 friends and 0–2 relatives = 0; all other scores = 1); group participation (no = 0; yes = 1); and participation in religious meetings or services ( ≤ every few months = 0; >once or twice a month = 1). Social Network Index scores ranged from 0 to 4, and a lower SNI score represented a higher level of social isolation. Scores of 0 and 1 represented the socially isolated category.

The NDDI-E is a rapid and user-friendly questionnaire used to assess depressive symptoms in PWE during the past 2 weeks (22). Patients were requested to respond to six self-rated questions, and each item was rated on a four-point scale (1–4). The sum of the scores ranged from 6 to 24, and higher scores represented higher levels of depressive symptoms.

We measured quality of life using the QOLIE-31 inventory. The test consisted of 31 questions and seven subscales: (1) seizure worry, (2) overall quality of life, (3) emotional well-being, (4) energy/fatigue, (5) cognitive functioning, (6) antiepileptic medication effects, and (7) social functioning. The total score ranged from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating a more favorable quality of life (23).

Categorical variables were described as numbers (percentages) and compared by chi-square tests or Fisher's exact tests. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± SD and analyzed by Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U-tests depending on the normal or non-normal distribution of the data assessed via the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Additionally, Spearman correlation analyses were used to examine the relationships between SNI scores and continuous variables. Using multivariate logistic regression analyses, the independent variables associated with socially isolated categories were investigated. Variables with p < 0.05 in the univariate analyses were included in the multivariate stepwise logistic regression model. All data were analyzed using SPSS 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All statistical tests were two-tailed, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 196 patients were invited to participate in the current study. Of that group, 31 patients were excluded for the following reasons: refusal to participate (11), inability to complete the questionnaires (n = 8), severe brain disease or other disorder (7), and <18 years old (n = 5). Thus, a total of 165 PWE were included in the study, with a median age of 33.88 years and a female percentage of 50.9%. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the total participants are shown in Table 1. Approximately half of the patients (48.5%) were married, and one-third of the patients (33.3%) were unemployed. The mean age at onset was 25.38 years (SD: 14.72), and the mean duration of epilepsy was 8.53 years (SD: 8.87). Focal epilepsy was the most common epilepsy type reported by 137 patients (83%). The mean SNI score was 2.56 (SD: 1.19), and 35 patients (21.2%) were socially isolated.

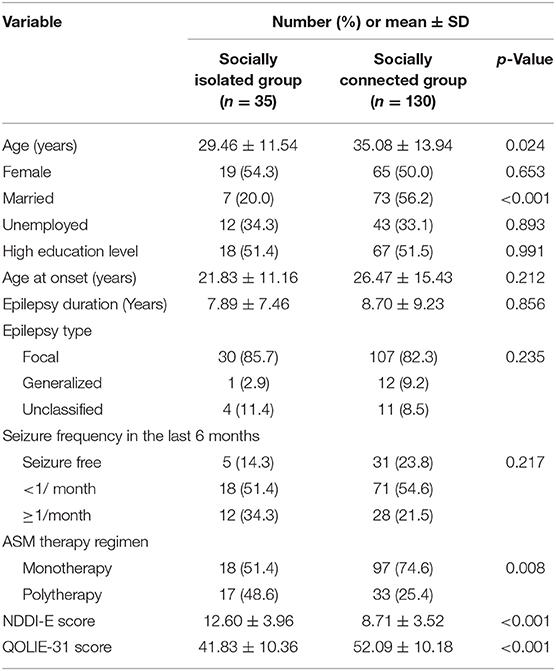

Patients in the socially isolated group were more likely to be younger (p = 0.024) and less likely to be married (p < 0.001) than those in the socially connected group. Polytherapy was more common in patients with social isolation (p = 0.008). Additionally, the NDDI-E score (p < 0.001) and QOLIE-31 score (p < 0.001) showed significant differences between patients in the socially isolated group and the socially connected group. There was no significant difference in gender, unemployment, high education level, age at onset, epilepsy duration, epilepsy type, or seizure frequency between the groups with, and without social isolation. For details, see Table 2.

Table 2. Comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics in socially isolated group and socially connected group.

The continuous variables that were significantly correlated with the SNI score are presented in Table 3. Age, age at onset, and QOLIE-31 score were positively correlated with SNI scores (p < 0.001, p = 0.001, and p < 0.001, respectively). Additionally, the NDDI-E score was negatively correlated with the SNI score (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, and p < 0.001, respectively). No correlation was found between epilepsy duration and SNI score.

Table 4 shows the independent factors associated with social isolation among PWE. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis, social isolation (present/absent) was the dependent variable, while age, age at onset, ASM therapy regimen, NDDI-E score, and QOLIE-31 score were included as covariates in the model. Higher depressive symptom levels (OR = 1.15, 95% CI: 1.003–1.318, P = 0.045) and poorer quality of life (OR = 0.967, 95% CI: 0.935–0.999, P = 0.047) emerged as independent factors associated with social isolation in PWE. The adjusted odds for social isolation in PWE increased by a factor of 1.15 with each point of increase in NDDI-E depressive scores. The adjusted odds for social isolation in PWE was 0.967 times smaller with each point of increase in QOLIE-31 scores. For details, see Table 4.

To our knowledge, this is the first study aimed at investigating the prevalence of social isolation and associated factors in adults with epilepsy. Findings from this study suggested that approximately one-fifth of patients are socially isolated, and that depressive symptoms and poor quality of life are independent factors associated with social isolation in PWE.

The prevalence of social isolation has been previously reported to range from 20 to 67.5% in PWE (19, 24). The 68% of PWE with social isolation reported by a recent cross-sectional study from USE was higher than the 21.2% of PWE reported in the current study (19). A prospective observational study reported that the prevalence of social isolation was 20% in children with symptomatic generalized epilepsy (24). One possible explanation for these results could be the differences in the basic characteristics of patients across studies. Another explanation for the different prevalence of social isolation might be cross-cultural differences.

This study found that marital status was associated with social isolation in PWE, and married patients were less likely to be socially isolated. Marital relationships are an important component of family support. Married adults reported more family support and fewer depressive symptoms (25). Patients with epilepsy without family support had poorer seizure control and a higher lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders than those who had family support (26). However, it remains uncertain whether PWE who lived with other people in the same household experienced less social isolation. A recent study from Japan also showed that during the nationwide COVID-19 pandemic, PWE who lived alone were more likely to experience increased seizure frequency, indicating the relationship between seizure control and social connection in patients (27). However, adults with epilepsy were more likely to be unmarried throughout their lives due to social discrimination and stigma (28, 29). Families continue to object to their children marrying PWE. Undesirable marital status may lead to a lack of family support and social isolation in patients.

We found that age and age at onset were also associated with social isolation in PWE. However, this significant association disappeared in multivariate analysis. Patients with social isolation were more likely to be younger and to have had an earlier age at first seizure onset. This finding was in agreement with prior investigations (17, 30). The parents of children with epilepsy said that friends and relatives who knew that the child had epilepsy always treated the child differently and did not like to be left alone with the child (30). Pal et al. similarly reported that children with epilepsy tended to have limited social interaction compared with their peers but that they spent more time interacting with peer groups as they grew older (17).

In the current study, we found that the adjusted odds for social isolation in PWE increased by a factor of 1.15 with each point of increase in NDDI-E depressive scores. Socially isolated young adults were more likely to have depression, showing the beneficial role of social relationships in mental health (31). However, our finding was not supported by a recent study (19). Stauder and his colleague reported that social integration was not associated with depressive burden in PWE (19). One possible explanation for these controversial findings is the relatively small sample size in their cohort. Another explanation for the results may be that the instrument employed to assess depressive symptoms differed between the studies. It is well-known that the PHQ-9 instrument has a broader range of scores than the NDDI-E (0–27) (4). The NDDI-E is specific to the population with epilepsy. Patients with epilepsy feel stigmatized and subject to discrimination if they have a seizure in front of others, which leads to limited social interaction and further exacerbates depression (32, 33). Social isolation acts as a stressor that leads to alterations in reactivity to stress and social behavior in people (34). It has been reported that stressful life events (e.g., divorce of parents or loss of a child) were a significant predictor of anxiety and depression in the general population (35). Additionally, the adjusted odds for social isolation in PWE decreased by a factor of 0.967 with each point of increase in QOLIE-31 scores, indicating the relationship between social isolation and poor quality of life in PWE. A prospective observational study similarly reported that social isolation has detrimental effects on the quality of life in older adults (36). Adolescents with epilepsy feel that their greatest interpersonal challenge is forming relationships with others, which may have a negative effect on their quality of life (37). It is well-known that social isolation is the lower end of a distribution of social support. Adults with epilepsy who lacked affectionate support were significantly more likely to report poor quality of life (38). Thus, PWE needs to be encouraged to actively integrate with others and reduce social isolation, which may help improve their quality of life.

This study faces several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design greatly limits the ability to draw any inferences regarding the causal relationship between these variables and social isolation, and regression analyses in a cross-sectional design study also have limited results. Second, the sample size in the socially isolated subgroup was relatively small, and all participants were adults with epilepsy enrolled from a large tertiary care hospital in northeast China. Thus, it cannot be claimed that this sample is representative of Chinese PWE. Third, the use of self-report for all measures in the present study may allow for response bias. Additionally, some variables that may be associated with social isolation in epilepsy (e.g., AED type) were not available and were not analyzed for our cohort. Finally, this study was performed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Social isolation and psychiatric symptoms may have been more frequent in PWE during this period.

The findings suggest that social isolation is common in adults with epilepsy. Social isolation is associated with depressive symptoms and poor quality of life. Further studies should examine whether improvements in social connection can improve depressive symptoms and quality of life in these patients.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of First Hospital, Jilin University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

RZ and WL conceived of and designed the study. RZ, HZ, XG, and YH were involved in data acquisition. RZ and QC analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by a grant from the Programme of Jilin University First Hospital Clinical Cultivation Fund (LCPYJJ2017006).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors would like to thank all of the participants for their valuable information, cooperation, and participation.

1. Thijs RD, Surges R, O'Brien TJ, Sander JW. Epilepsy in adults. Lancet. (2019) 393:689–701. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32596-0

2. Lu Y, Zhong R, Li M, Zhao Q, Zhang X, Hu B, et al. Social anxiety is associated with poor quality of life in adults with epilepsy in Northeast China: a cross-sectional study. Epilepsy Behav. (2021) 117:107866. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.107866

3. Elliott JO, Charyton C, Sprangers P, Lu B, Moore JL. The impact of marriage and social support on persons with active epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. (2011) 20:533–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.01.013

4. Zhang H, Zhong R, Chen Q, Guo X, Han Y, Zhang X, et al. Depression severity mediates the impact of perceived stigma on quality of life in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. (2021) 125:108448. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.108448

5. Dalky HF, Gharaibeh H, Faleh R. Psychosocial burden and stigma perception of Jordanian patients with epilepsy. Clin Nurs Res. (2019) 28:422–35. doi: 10.1177/1054773817747172

6. Paiva ML, Lima EM, Siqueira IB, Rzezak P, Koike C, Moschetta SP, et al. Seizure control and anxiety: which factor plays a major role in social adjustment in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy? Seizure. (2020) 80:234–9. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2020.06.033

7. Yogarajah M, Mula M. Social cognition, psychiatric comorbidities, and quality of life in adults with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. (2019) 100:106321. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.05.017

8. Raud T, Kaldoja ML, Kolk A. Relationship between social competence and neurocognitive performance in children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. (2015) 52:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.08.028

9. Morgan C, Burns T, Fitzpatrick R, Pinfold V, Priebe S. Social exclusion and mental health: conceptual and methodological review. Br J Psychiatry. (2007) 191:477–83. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.034942

10. Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Capitanio JP, Cole SW. The neuroendocrinology of social isolation. Annu Rev Psychol. (2015) 66:733–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015240

11. Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, Reynolds S, Shafran R, Brigden A, et al. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2020) 59:1218.e3–39.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

12. Wang J, Lloyd-Evans B, Giacco D, Forsyth R, Nebo C, Mann F, et al. Social isolation in mental health: a conceptual and methodological review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2017) 52:1451–61. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1446-1

13. Blaszczyk B, Czuczwar SJ. Epilepsy coexisting with depression. Pharmacol Rep. (2016) 68:1084–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2016.06.011

14. Zhong R, Lu Y, Chen Q, Li M, Zhao Q, Zhang X, et al. Sex differences in factors associated with quality of life in patients with epilepsy in Northeast China. Epilepsy Behav. (2021) 121:108076. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.108076

15. Patterson AC, Veenstra G. Loneliness and risk of mortality: a longitudinal investigation in Alameda County, California. Soc Sci Med. (2010) 71:181–6. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.024

16. Akhter-Khan SC, Tao Q, Ang T, Itchapurapu IS, Alosco ML, Mez J, et al. Associations of loneliness with risk of Alzheimer's disease dementia in the Framingham Heart Study. Alzheimers Dement. (2021) 17:1619–27. doi: 10.1002/alz.12327

17. Pal DK, Chaudhury G, Sengupta S, Das T. Social integration of children with epilepsy in rural India. Soc Sci Med. (2002) 54:1867–74. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00154-X

18. O'Toole S, Benson A, Lambert V, Gallagher P, Shahwan A, Austin JK. Family communication in the context of pediatric epilepsy: a systematic review. Epilepsy Behav. (2015) 51:225–39. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.06.043

19. Stauder M, Vogel AC, Nirola DK, Tshering L, Dema U, Dorji C, et al. Depression, sleep quality, and social isolation among people with epilepsy in Bhutan: a cross-sectional study. Epilepsy Behav. (2020) 112:107450. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107450

20. Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, Bogacz A, Cross JH, Elger CE, et al. ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia. (2014) 55:475–82. doi: 10.1111/epi.12550

21. Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol. (1979) 109:186–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674

22. Gilliam FG, Barry JJ, Hermann BP, Meador KJ, Vahle V, Kanner AM. Rapid detection of major depression in epilepsy: a multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. (2006) 5:399–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70415-X

23. Cramer JA, Perrine K, Devinsky O, Bryant-Comstock L, Meador K, Hermann B. Development and cross-cultural translations of a 31-item quality of life in epilepsy inventory. Epilepsia. (1998) 39:81–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01278.x

24. Camfield C, Camfield P. Twenty years after childhood-onset symptomatic generalized epilepsy the social outcome is usually dependency or death: a population-based study. Dev Med Child Neurol. (2008) 50:859–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03165.x

25. Zhang B, Li J. Gender and marital status differences in depressive symptoms among elderly adults: the roles of family support and friend support. Aging Ment Health. (2011) 15:844–54. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.569481

26. Jayalakshmi S, Padmaja G, Vooturi S, Bogaraju A, Surath M. Impact of family support on psychiatric disorders and seizure control in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. (2014) 37:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.05.020

27. Neshige S, Aoki S, Shishido T, Morino H, Iida K, Maruyama H. Socio-economic impact on epilepsy outside of the nation-wide COVID-19 pandemic area. Epilepsy Behav. (2021) 117:107886. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.107886

28. Li S, Chen J, Abdulaziz A, Liu Y, Wang X, Lin M, et al. Epilepsy in China: factors influencing marriage status and fertility. Seizure. (2019) 71:179–84. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2019.07.020

29. Zhao T, Zhong R, Chen Q, Li M, Zhao Q, Lu Y, et al. Sex differences in marital status of people with epilepsy in Northeast China: an observational study. Epilepsy Behav. (2020) 113:107571. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107571

30. Rani A, Thomas PT. Stress and perceived stigma among parents of children with epilepsy. Neurol Sci. (2019) 40:1363–70. doi: 10.1007/s10072-019-03822-6

31. Matthews T, Danese A, Wertz J, Odgers CL, Ambler A, Moffitt TE, et al. Social isolation, loneliness and depression in young adulthood: a behavioural genetic analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. (2016) 51:339–48. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1178-7

32. Fazekas B, Megaw B, Eade D, Kronfeld N. Insights into the real-life experiences of people living with epilepsy: a qualitative netnographic study. Epilepsy Behav. (2021) 116:107729. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107729

33. Henning O, Buer C, Nakken KO, Lossius MI. People with epilepsy still feel stigmatized. Acta Neurol Scand. (2021) 144:312–6. doi: 10.1111/ane.13449

34. Mumtaz F, Khan MI, Zubair M, Dehpour AR. Neurobiology and consequences of social isolation stress in animal model - a comprehensive review. Biomed Pharmacother. (2018) 105:1205–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.05.086

35. Faravelli C, Catena M, Scarpato A, Ricca V. Epidemiology of life events: life events and psychiatric disorders in the Sesto Fiorentino study. Psychother Psychosom. (2007) 76:361–8. doi: 10.1159/000107564

36. Beridze G, Ayala A, Ribeiro O, Fernandez-Mayoralas G, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Rodriguez-Rodriguez V, et al. Are loneliness and social isolation associated with quality of life in older adults? Insights from Northern and Southern Europe. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:8637. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228637

37. Thomson L, Fayed N, Sedarous F, Ronen GM. Life quality and health in adolescents and emerging adults with epilepsy during the years of transition: a scoping review. Dev Med Child Neurol. (2014) 56:421–33. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12335

Keywords: social isolation, Berkman-Syme Social Network Index, epilepsy, depressive symptoms, quality of life

Citation: Zhong R, Zhang H, Chen Q, Guo X, Han Y and Lin W (2022) Social Isolation and Associated Factors in Chinese Adults With Epilepsy: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Neurol. 12:813698. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.813698

Received: 12 November 2021; Accepted: 13 December 2021;

Published: 11 January 2022.

Edited by:

Kette D. Valente, Universidade de São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Silvia Vincentiis, Universidade de São Paulo, BrazilCopyright © 2022 Zhong, Zhang, Chen, Guo, Han and Lin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Weihong Lin, bGlud2hAamx1LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.