- 1Department of Neurology, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

- 2China National Clinical Research Center for Neurological Diseases, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

Background and Purpose: Although elevated serum lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] is considered to be a risk factor of ischemic stroke, the relationship between Lp(a) and cognitive impairment after stroke remains unclear. This study investigated the association between serum Lp(a) and cognitive function after acute ischemic stroke (AIS) or transient ischemic attack (TIA).

Methods: The study included 1,017 patients diagnosed with AIS or TIA from the cognition subgroup of the Third China National Stroke Registry (CNSR3). Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) at 2 weeks or discharge, 3 months, and 1 year was evaluated. The primary outcome was cognitive impairment at 1 year, defined as MoCA ≤ 22. The secondary outcome was cognition improvement at 1 year compared with 2 weeks. The association between Lp(a) levels and cognitive function was analyzed.

Results: Among the 1,017 patients included, 326 (32.1%) had cognitive impairment at 1 year. Patients with MoCA ≤ 22 at 1 year were older, received less education, and had higher baseline NIHSS, higher proportion of ischemic stroke history, large artery atherosclerosis (LAA) subtype, and multiple infarctions (P < 0.05 for all). Patients with highest Lp(a) quartile had slightly higher percentage of cognitive impairment at 1 year but without statistical difference. In subgroup analysis of LAA subtype, the patients with highest Lp(a) quartile had higher percentage of cognitive impairment at 1 year (adjusted OR:2.63; 95% CI: 1.05–6.61, P < 0.05). What is more, the patients with highest Lp(a) quartile in LAA subtype had lower percentage of cognition improvement at 1 year. However, similar results were not found in small artery occlusion (SAO) subtype.

Conclusion: Higher Lp(a) level was associated with cognitive impairment and less improvement of cognition in patients after AIS or TIA with large-artery atherosclerosis subtype.

Introduction

Stroke and dementia are currently two main causes affecting brain function in older people (1). Stroke survivors have an increased risk of developing cognitive impairment or dementia (2–4). Studies reported that the incidence of dementia after stroke varied from 7.4% in a population-based study on first stroke to 41.3% in hospital-based cases of recurrent stroke (5). Lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] (6) is a low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-like particle with its apolipoprotein B100 (apoB-100) moiety linked to a large polymorphic glycoprotein named apo(a) via a single disulfide bond. Lp(a) is considered to be a risk factor of ischemic stroke because of its role in atherosclerosis and thrombosis (7). However, the relationship between serum Lp(a) and cognitive impairment or dementia is still controversial. Previous studies have shown that Lp(a) had an adverse effect (8, 9) or no effect (10–12) on cognition, whereas, in recent years some studies have found that it had a beneficial influence (13–15).

In this study, we aimed to investigate the association between serum Lp(a) levels and cognitive impairment after acute ischemic stroke (AIS) or transient ischemic attack (TIA) and analyzed it under different etiological classifications.

Methods

ICONS Group and Study Population

The Third China National Stroke Registry (CNSR-III) (16) is a nationwide clinical registry that includes patients who had AIS or TIA within 7 days after the onset of symptoms from 201 hospitals in China between August 2015 and January 2018. A total of 40 study sites with experience in cognition and sleep research participated in the (17) Impairment of CognitiON and Sleep quality for patients after AIS or TIA (ICON) subgroup. The inclusion criteria for ICONS were the same as those for the CNSR-III, but several exclusion criteria were added, such as prior diagnosis of cognitive impairment, schizophrenia or psychosis disease; illiteracy, and concomitant neurological disorders that interfere with cognitive or sleep evaluation, for example, severe aphasia defined as National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) item 9 >2, visual impairment, hearing loss, dyslexia, severe unilateral neglect, and consciousness disorders. Patients with cerebral infarction on MRI or CT and without symptoms or signs were excluded.

Basic Data Collection

The baseline information was collected prospectively using an electronic data capture system by face-to-face interviews, and included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), current smoking habit, medical history (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, ischemic stroke, TIA, coronary heart diseases, and atrial fibrillation/flutter), previous medication, Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) criteria, NIHSS score, and so on.

Measurement of Lp(a)

Fasting blood samples were collected in serum separation tubes and EDTA anticoagulation blood collection tubes within 24 h of admission from all the patients. All the blood samples were transported through cold chain to the center laboratory in Beijing Tiantan Hospital, where all serum specimens were stored at −80° refrigerator until testing was performed. Serum Lp(a) was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Mercodia AB, Sweden). Mercodia Lp(a) ELISA is based on the direct sandwich technique in which two monoclonal antibodies are directed against separate antigenic determinants in the Apo(a) molecule.

Assessment of Cognition

Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) was evaluated by trained examiners at 2 weeks or discharge, 3 months, and 1 year after AIS or TIA. Cognitive impairment was defined as MoCA ≤ 22 at 1 year. We subtracted the MoCA values at 2 weeks from MoCA values at 1 year to evaluate cognition improvement of the patients.

Statistical Analysis

The patients were divided into four groups by Lp(a) quartiles, and baseline characteristics were compared. Continuous variables were described by median with interquartile range (IQR) because of skewed distribution. Categorical variables were described by frequencies with percentages. Non-parametric Wilcoxon or Kruskal–Wallis test was performed to compare group differences for continuous variables, and chi-square test or Fisher exact test was performed for categorical variables. The association between Lp(a) and cognitive function was investigated with a logistic regression model. The variables were adjusted in multivariable analyses if established as a traditional predictor or with a P-value of ≤ 0.1 in univariate analysis. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. We also analyzed the association in different TOAST subtypes such as the large-artery atherosclerosis (LAA) and small-artery occlusion (SAO) subtypes.

Overall, a two-sided P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

Data Availability Policy

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author.

Results

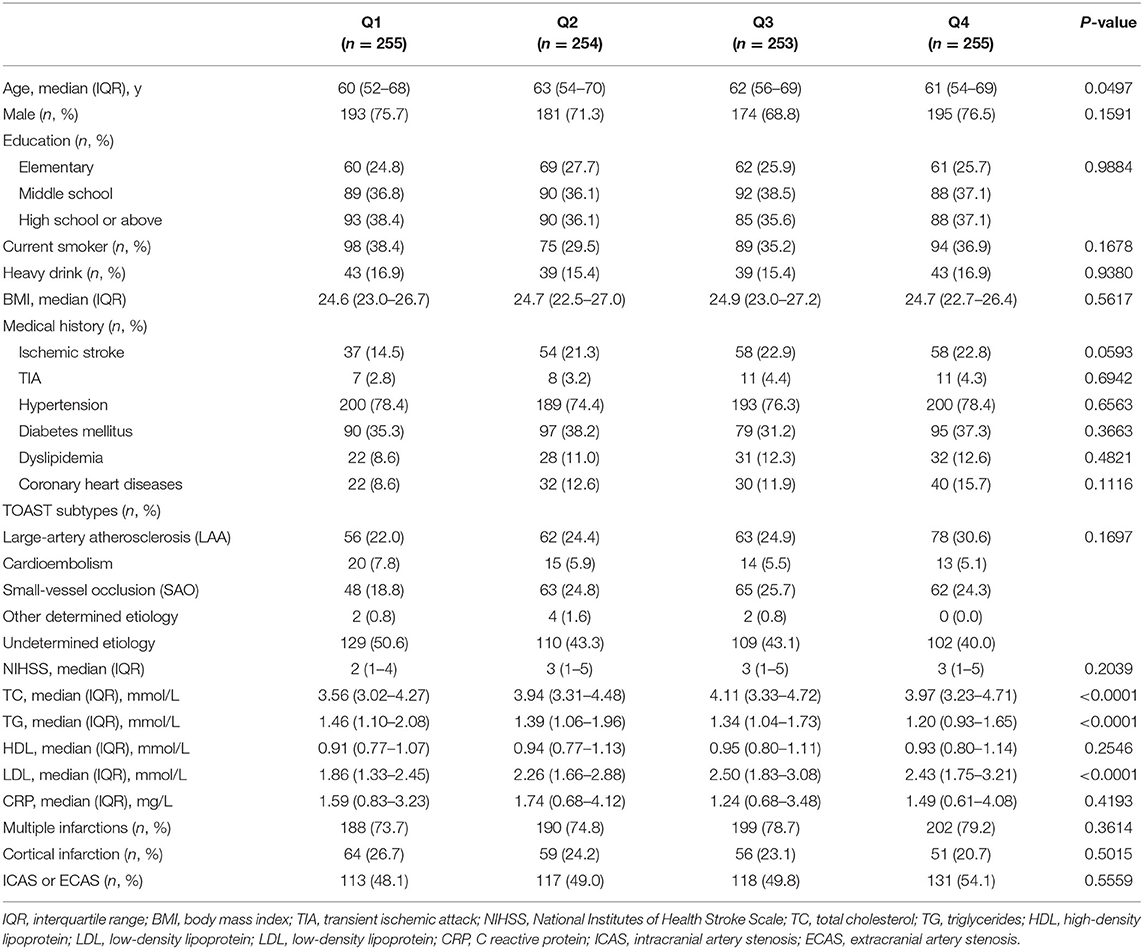

Among total 2625 patients in ICONS study, 797 patients without Lp(a) values and 550 patients without available MoCA at 1 year were excluded from this study. Thus, a total of 1,017 patients were analyzed in this study. Baseline characteristics of the excluded and included patients are presented in Supplementary Table 1. The patients were stratified into quartiles according to Lp(a) levels. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. For all included patients, the median (IQR) age was 62 (53–69) years, and 743 (73.1%) of the patients were male. The median (IQR) serum Lp(a) was 145.01 (70.23–292.47) mg/dl. Compared with the lowest quartile, patients with higher quartiles of Lp(a) were older, had slightly higher proportion of ischemic stroke history and higher TC, LDL-C, TG levels (Table 1).

Lp(a) and Cognitive Function

Three hundred twenty-six (32.1%) of the patients had MoCA ≤ 22 at 1 year after AIS or TIA. Compared with patients with MoCA >22, the patients with MoCA ≤ 22 were older, had lower level of education, higher proportions of previous ischemic stroke, large-artery atherosclerosis (LAA) subtype, and multiple infarctions, and higher NIHSS and CRP levels (Supplementary Table 2).

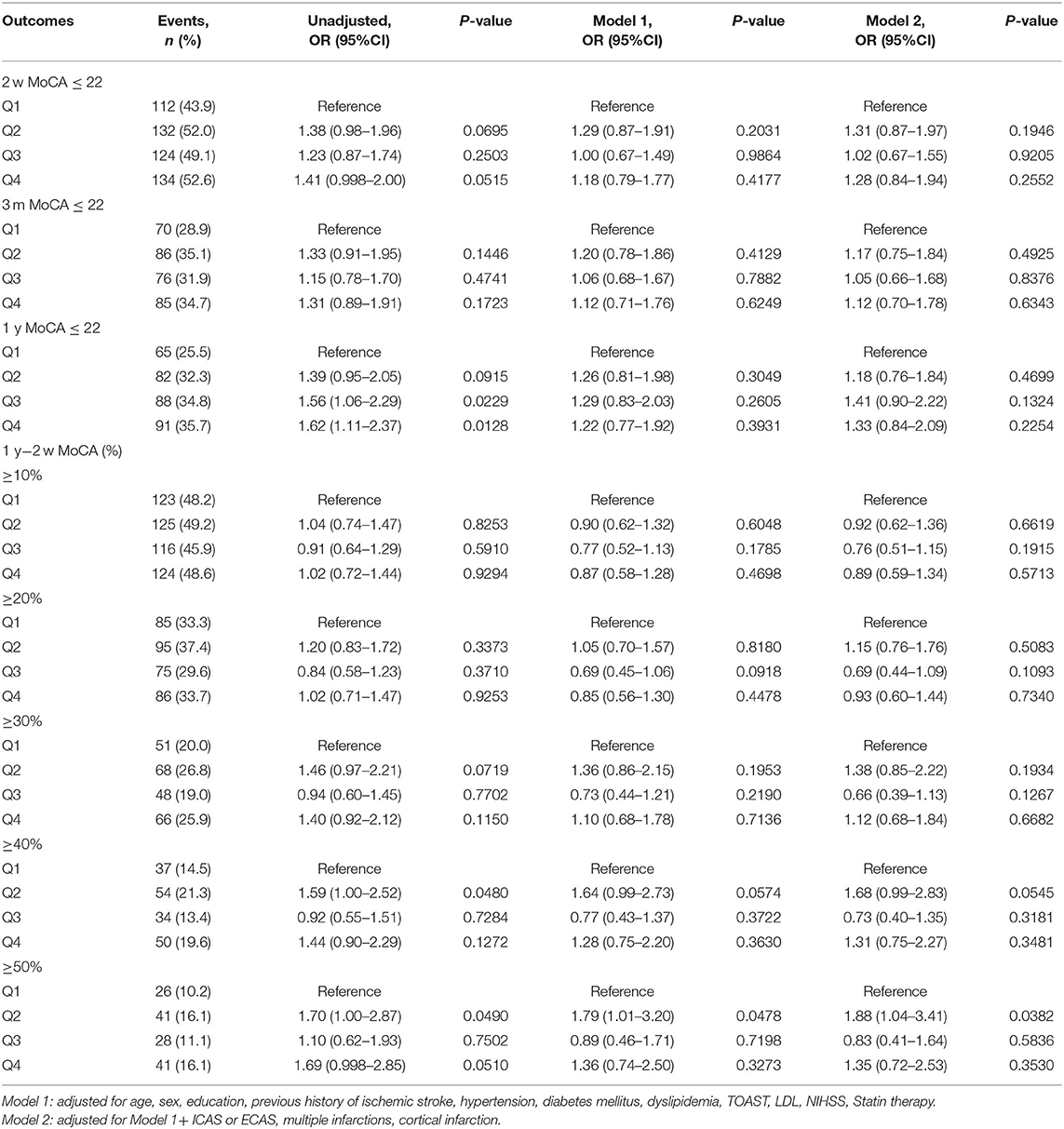

Patients in higher quartiles of Lp(a) levels had a higher proportion of cognitive impairment at 1 year, but no statistical difference was found (the highest vs. the lowest quartile: OR 1.33; 95% CI: 0.84–2.09, P > 0.05). No association was found between Lp(a) and cognition improvement at 1 year compared to baseline MOCA values after AIS or TIA (Table 2).

Subgroup Analysis in TOAST Subtypes

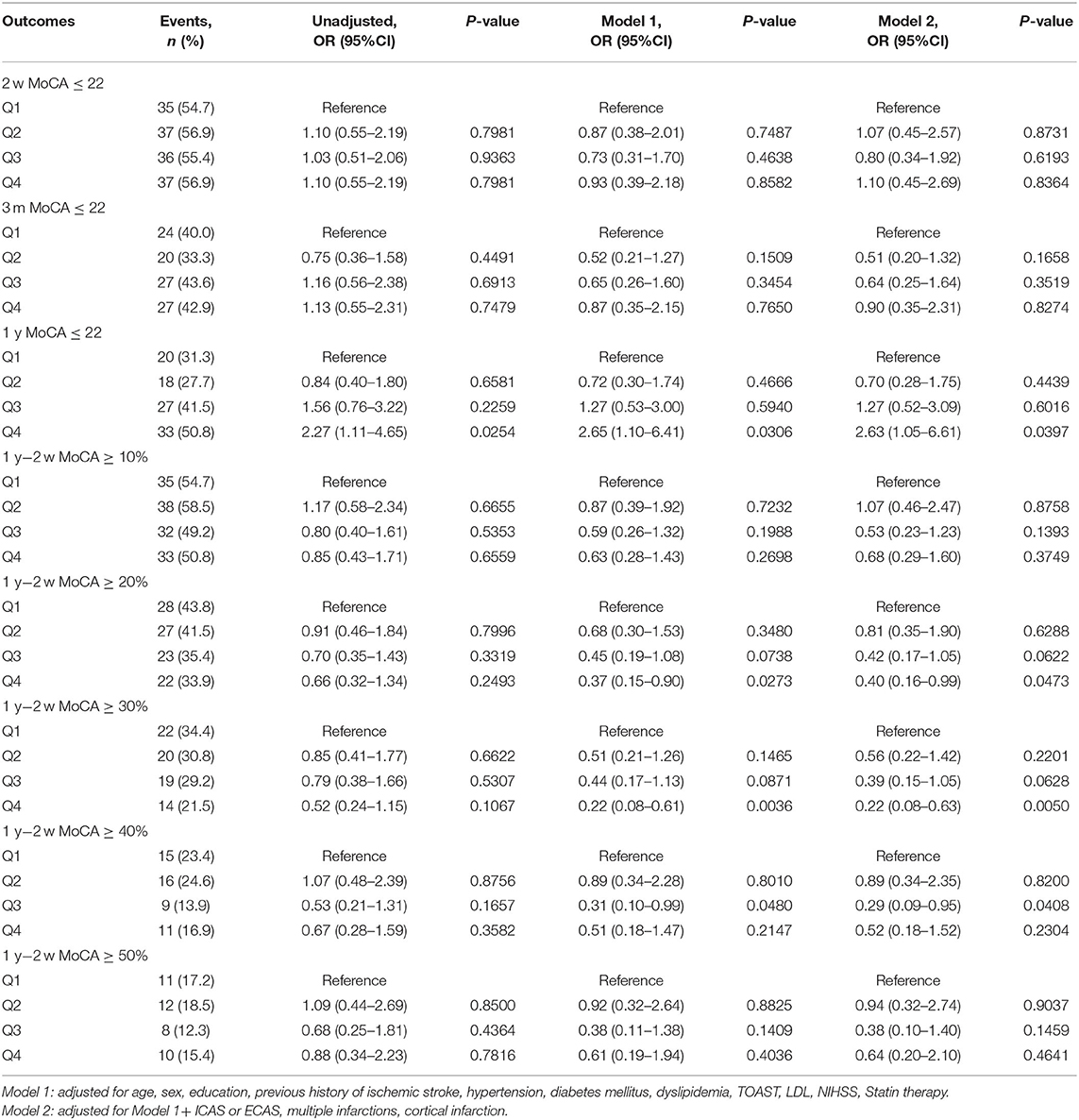

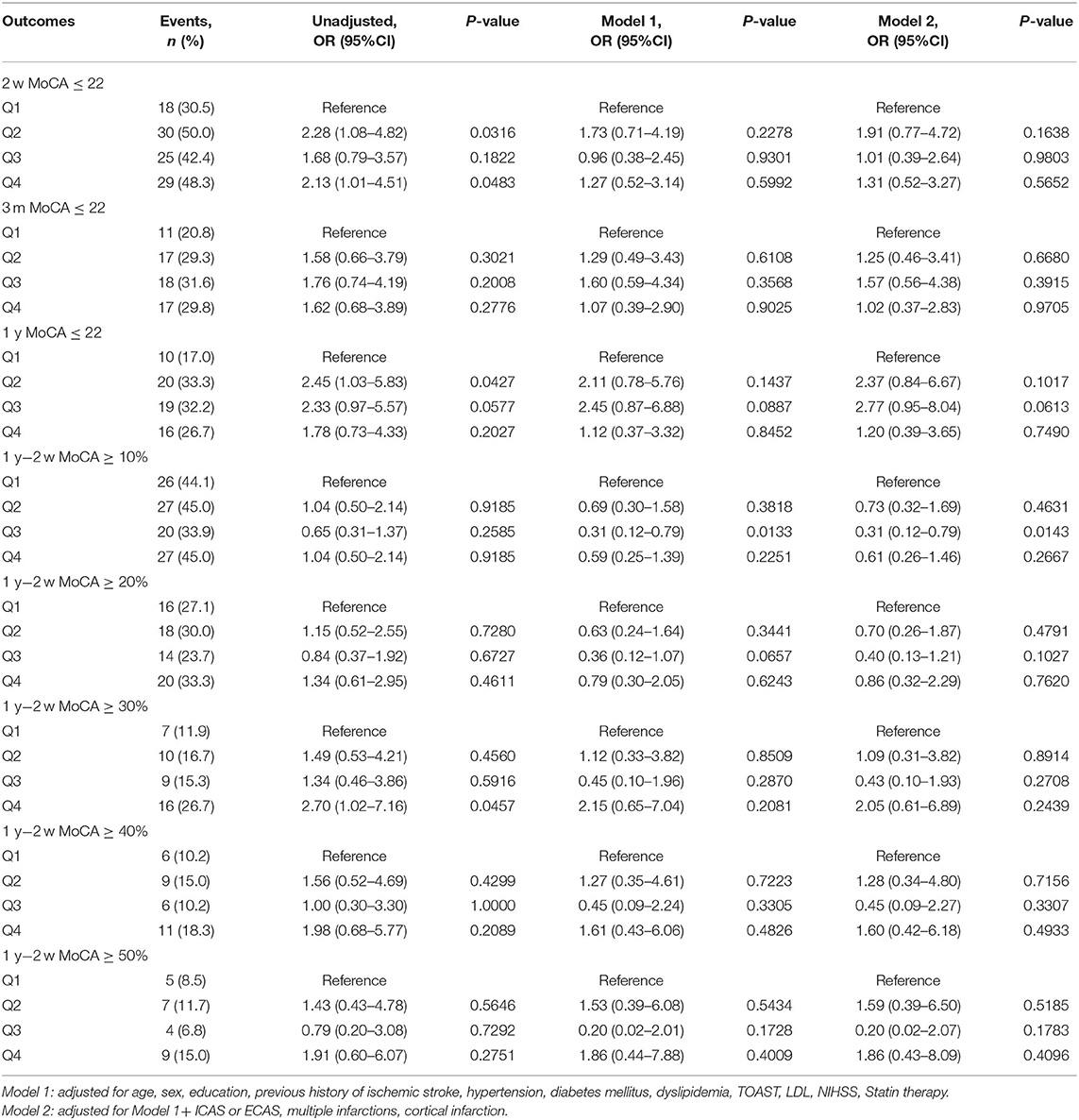

The median (IQR) serum Lp(a) levels in LAA and small-vessel occlusion (SAO) subtypes were 160.27(80.81–336.76) and 150.7 (79.67–303.78) mg/dl, respectively. In patients with LAA subtype, higher Lp(a) levels were associated with increased risk of cognitive impairment (MOCA ≤ 22) at 1 year. The adjusted OR for the highest vs. the lowest quartile of Lp(a) was 2.63 (95% CI 1.05–6.61, P < 0.05) after adjusting for potential confounding factors. What is more, higher Lp(a) quartiles were associated with lower percentage of cognition improvement at 1 year compared to cognition status at 2 weeks in LAA subtype. Adjusted ORs (95% CI) for the highest vs. lowest quartile of Lp(a) were 0.4 (0.16–0.99) and 0.22 (0.08–0.63) when cognition improvement was defined as ≥20 and 30%, respectively (Table 3). However, similar association was not found in patients with SAO subtype (Table 4).

Discussion

This study found that higher Lp(a) level was associated with cognitive impairment and less cognition improvement at 1 year after AIS or TIA in LAA subtype. Similar association was not found in SAO subtype.

Lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] was considered to be a risk factor of ischemic stroke, although the results were inconsistent. The meta-analysis indicated that elevated Lp(a) level was associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke (7). A Mendelian randomization study (18) showed that 1-SD genetically lowered Lp(a) level was associated with a 13% lower risk of stroke. Recent studies revealed that Lp(a) might play different roles in different stroke subtypes. A prospective stroke registry study in Korean (19) showed that Lp(a) levels in large artery atherosclerosis (LAA) stroke were significantly higher than other four subtypes, and that elevated Lp(a) levels were associated with extensive burden of intracranial and extracranial vascular steno-occlusive lesions. What is more, a Mendelian randomization analysis (14) based on data from a large-scale GWAS study demonstrated that higher Lp(a) levels may lead to an increased risk of large artery stroke but a decreased risk of small vessel stroke. Studies on the association between Lp(a) concentrations and cognitive impairment are limited and controversial. Many studies showed Lp(a) was higher in vascular dementia than healthy controls (20, 21). Cross-sectional data of 1,380 healthy Berlin Aging Study II (BASE-II) (8) participants suggested that men with lower Lp(a) concentrations had better cognitive performance. Conversely, a prospective cohort of 2,532 subjects of Finnish (15) male population in 24.9 years' follow-up, showed that Lp(a) was protective of future dementia risk. Another large prospective cohort study based on four United States communities (13) showed that higher Lp(a) levels were associated with slower cognitive decline in semantic fluency over 15 years. What is more, negative results were also obtained in several studies. A previous cross-sectional study (12) has found that no statistically significant difference in cognitive performances between subjects with elevated and normal Lp(a) levels and subjects who showed a similar decline rate during follow-up. A large prospective cohort study on pravastatin in the elderly at risk (PROSPER) (11) over an average 3.2 years of follow-up proved that Lp(a) was a predictor of combined cardiovascular events instead of cognitive function. However, most of these inconsistent results came from the follow-up of non-affected populations. This study focused on cognitive impairment and cognition changes after AIS or TIA events and found that higher Lp(a) levels were associated with cognitive impairment and less cognition improvement at 1 year in LAA subtype instead of SAO subtype. These results suggested that Lp(a) may play different roles in different stroke types.

Serum Lp(a) is genetically determined and relatively stable throughout the life of an individual. Lifestyle changes and conventional lipid-lowering therapies seem to be ineffective in reducing elevated Lp(a) levels. Oxidative stress and inflammation have been proved to play important roles in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and thrombosis (22, 23). Studies also suggested that Lp(a) was involved in atherosclerosis and thrombosis (6), although the pathophysiology remained unclear. The presence of oxidized phospholipids (OxPLs) on Lp(a) and apo(a) positive staining in human atherosclerotic plaques confers its proatherogenic property (24). Cerrato (25) found that Lp(a) was associated with large vessel disease independent of LDL level, suggesting its primary involvement in atherothrombotic stroke. The apo(a) in Lp(a) has structural similarities with plasminogen and inhibits fibrinolysis by interfering with the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, which is attributed to the thrombotic actions of Lp(a). Studies showed that age-related loss of cognitive function might be driven by atherosclerotic effects associated with altered lipid patterns, and that optimal control of cardiovascular risk factors may reduce the risk of cognitive decline (26). Given the established role of Lp(a) levels in atherosclerosis and thrombosis, elevated Lp(a) levels may aggravate cognitive impairment by promoting the occurrence of ischemic events, which is consistent with the results in LAA subtype in this study. Research studies on Lp(a) and SAO subtype were very limited. A previous study has shown that Lp(a) promoted atherothrombotic stroke instead of lacunar stroke (25). The aforementioned Mendelian randomization study (14) proved that genetically predicted higher Lp(a) concentrations may lead to a decreased risk of small vessel stroke. This study did not find similar adverse effects of Lp(a) on cognition in SAO subtype, which suggested that there might exist different mechanisms compared with LAA subtype. Further exploration is needed on the relationship between Lp(a) and different stroke subtypes, especially in SAO subtype.

This study has several strengths. First, we analyzed the relationship between Lp(a) and cognition after AIS or TIA in different stroke subtypes, which is very limited so far. Second, this study was based on a large stroke registration study, and patients were evaluated for cognitive function at baseline (after stroke events), 3 months, and 1 year after AIS or TIA, which allowed us to dynamically analyze the changes in cognition. However, this study also has limitations: First, the patients selected in this study had mainly mild ischemic stroke or patients with TIA, which might not represent all patients with AIS/TIA. Second, more than half of the patients were excluded because of missing Lp(a) or MoCA variables, although the baseline characteristics of the excluded and included patients were well-balanced. Third, MoCA required a relatively higher degree of cooperation, although the ICONS excluded prior diagnosis of cognitive impairment, psychosis disease, illiterate patients, severe aphasia, and so on.

Conclusion

Higher Lp(a) level was associated with cognitive impairment and less improvement of cognition in patients after AIS or TIA with large-artery atherosclerosis subtype.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by IRB approval number: KY2015-001-01. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

JL and SL conducted this study, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. YoW designed and supervised this study and interpreted the data. XZ, YiW, and XM supervised this study. MW and YP conducted the statistical analysis and interpreted the data. SL conducted this study and statistical analysis and interpreted the data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (Grant Nos: 2016YFC0901001, 2016YFC0901002, 2017YFC1310901, and 2017YFC1310902) and Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (Grant No: D151100002015003).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants in the study.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2021.736365/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Global, regional, and and national burden of neurological disorders 1990–2016: 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. (2019) 18:459–80. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30499-X

2. Lo J, Crawford J, Desmond D, Godefroy O, Jokinen H, Mahinrad S, et al. Profile of and risk factors for poststroke cognitive impairment in diverse ethnoregional groups. Neurology. (2019) 93:e2257–71. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008612

3. Hachinski V, Einhäupl K, Ganten D, Alladi S, Brayne C, Stephan BCM, et al. Preventing dementia by preventing stroke: the Berlin Manifesto. Alzheimers Dement. (2019) 15:961–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.06.001

4. Shen J, Tozer D, Markus H, Tay J. Network efficiency mediates the relationship between vascular burden and cognitive impairment: a diffusion tensor imaging study in UK biobank. Stroke. (2020) 51:1682–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.028587

5. Pendlebury S, Rothwell P. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with pre-stroke and post-stroke dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. (2009) 8:1006–18. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70236-4

6. Rawther T, Tabet F. Biology, pathophysiology and current therapies that affect lipoprotein (a) levels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. (2019) 131:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2019.04.005

7. Nave A, Lange K, Leonards C, Siegerink B, Doehner W, Landmesser U, et al. Lipoprotein (a) as a risk factor for ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. (2015) 242:496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.08.021

8. Röhr F, Bucholtz N, Toepfer S, Norman K, Spira D, Steinhagen-Theissen E, et al. Relationship between Lipoprotein (a) and cognitive function - results from the Berlin Aging Study II. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:10636. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66783-3

9. Ray L, Khemka V, Behera P, Bandyopadhyay K, Pal S, Pal K, et al. Serum homocysteine, dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate and lipoprotein (a) in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Aging Dis. (2013) 4:57–64.

10. Lippi G, Danese E, Favaloro EJ. Vascular disease and dementia: lipoprotein(a) as a neglected link. Semin Thromb Hemost. (2019) 45:544–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1687907

11. Gaw A, Murray HM, Brown EA. Plasma lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] concentrations and cardiovascular events in the elderly: evidence from the prospective study of pravastatin in the elderly at risk (PROSPER). Atherosclerosis. (2005) 180:381–8. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.12.015

12. Sarti C, Pantoni L, Pracucci G, Di Carlo A, Vanni P, Inzitari D. Lipoprotein(a) and cognitive performances in an elderly white population: cross-sectional and follow-up data. Stroke. (2001) 32:1678–83. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.32.7.1678

13. Pokharel Y, Mouhanna F, Nambi V, Virani SS, Hoogeveen R, Alonso A, et al. ApoB, small-dense LDL-C, Lp(a), LpPLA activity, and cognitive change. Neurology. (2019) 92:e2580–93. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007574

14. Pan Y, Li H, Wang Y, Meng X, Wang Y. Causal effect of Lp(a) [Lipoprotein(a)] level on ischemic stroke and Alzheimer disease: a mendelian randomization study. Stroke. (2019) 50:3532–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.026872

15. Kunutsor SK, Khan H, Nyyssönen K, Laukkanen JA. Is lipoprotein (a) protective of dementia? Eur J Epidemiol. (2016) 31:1149–52. doi: 10.1007/s10654-016-0184-0

16. Wang Y, Jing J, Meng X, Pan Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. The Third China National Stroke Registry (CNSR-III) for patients with acute ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack: design, rationale and baseline patient characteristics. Stroke Vasc Neurol. (2019) 4:158–64. doi: 10.1136/svn-2019-000242

17. Wang Y, Liao X, Wang C, Zhang N, Zuo L, Yang Y, et al. Impairment of cognition and sleep after acute ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in Chinese patients: design, rationale and baseline patient characteristics of a nationwide multicentre prospective registry. Stroke Vasc Neurol. (2020) 6:139–44. doi: 10.1136/svn-2020-000359

18. Emdin C, Khera A, Natarajan P, Klarin D, Won H-H, Peloso GM, et al. phenotypic characterization of genetically lowered human lipoprotein(a) levels. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2016) 68:2761–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.033

19. Kim B, Jung H, Bang O, Chung C, Lee K, Kim G. Elevated serum lipoprotein(a) as a potential predictor for combined intracranial and extracranial artery stenosis in patients with ischemic stroke. Atherosclerosis. (2010) 212:682–8. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.07.007

20. Urakami K, Wada-Isoe K, Wakutani Y, Ikeda K, Ji Y, Yamagata K, et al. Lipoprotein(a) phenotypes in patients with vascular dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. (2000) 11:135–8. doi: 10.1159/000017226

21. Emanuele E, Peros E, Tomaino C, Feudatari E, Bernardi L, Binetti G, et al. Relation of apolipoprotein(a) size to alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. (2004) 18:189–96. doi: 10.1159/000079200

22. Della Corte V, Tuttolomondo A, Pecoraro R, Di Raimondo D, Vassallo V, Pinto A. Inflammation, endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffness as therapeutic targets in cardiovascular medicine. Curr Pharm Design. (2016) 22:4658–68. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160510124801

23. Tuttolomondo A, Pedone C, Pinto A, Di Raimondo D, Fernandez P, Di Sciacca R, et al. Predictors of outcome in acute ischemic cerebrovascular syndromes: the GIFA study. Int J Cardiol. (2008) 125:391–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.03.109

24. van Dijk R, Kolodgie F, Ravandi A, Leibundgut G, Hu PP, Prasad A, et al. Differential expression of oxidation-specific epitopes and apolipoprotein(a) in progressing and ruptured human coronary and carotid atherosclerotic lesions. J Lipid Res. (2012) 53:2773–90. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P030890

25. Cerrato P, Imperiale D, Fornengo P, Bruno G, Cassader M, Maffeis P, et al. Higher lipoprotein (a) levels in atherothrombotic than lacunar ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Neurology. (2002) 58:653–5. doi: 10.1212/WNL.58.4.653

Keywords: lipoprotein(a), cognitive function, ischemic stroke, stroke subtypes, dementia

Citation: Li J, Li S, Pan Y, Wang M, Meng X, Wang Y, Zhao X and Wang Y (2021) Relationship Between Lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] and Cognition in Different Ischemic Stroke Subtypes. Front. Neurol. 12:736365. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.736365

Received: 05 July 2021; Accepted: 29 October 2021;

Published: 03 December 2021.

Edited by:

Swathi Kiran, Boston University, United StatesReviewed by:

Antonino Tuttolomondo, University of Palermo, ItalyTatjana Rundek, University of Miami, United States

Copyright © 2021 Li, Li, Pan, Wang, Meng, Wang, Zhao and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yongjun Wang, eW9uZ2p1bndhbmdAbmNyY25kLm9yZy5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Jingjing Li1,2†

Jingjing Li1,2† Shiyu Li

Shiyu Li Yuesong Pan

Yuesong Pan Xia Meng

Xia Meng Xingquan Zhao

Xingquan Zhao Yongjun Wang

Yongjun Wang