94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Neurol. , 10 August 2021

Sec. Dementia and Neurodegenerative Diseases

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.702770

This article is part of the Research Topic Frontotemporal Dementia and its Spectrum in Latin America and the Caribbean: a Multidisciplinary Perspective View all 21 articles

Beyond canonical deficits in social cognition and interpersonal conduct, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) involves language difficulties in a substantial proportion of cases. However, since most evidence comes from high-income countries, the scope and relevance of language deficits in Latin American bvFTD samples remain poorly understood. As a first step toward reversing this scenario, we review studies reporting language measures in Latin American bvFTD cohorts relative to other groups. We identified 24 papers meeting systematic criteria, mainly targeting phonemic and semantic fluency, naming, semantic processing, and comprehension skills. The evidence shows widespread impairments in these domains, often related to overall cognitive disturbances. Some of these deficits may be as severe as in other diseases where they are more widely acknowledged, such as Alzheimer's disease. Considering the prevalence and informativeness of language deficits in bvFTD patients from other world regions, the need arises for more systematic research in Latin America, ideally spanning multiple domains, in diverse languages and dialects, with validated batteries. We outline key challenges and pathways of progress in this direction, laying the ground for a new regional research agenda on the disorder.

Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) is the most frequent form of frontotemporal dementia, a disease that affects between 1.2 and 1.8% of Latin American residents above age 55 (1). Patients exhibit insidious changes in personality and behavior, typically manifested as disinhibition, compulsion, apathy, hyperorality, and loss of empathy, alongside executive deficits and spared memory and visuospatial skills (2, 3). These domains have been the focus of neurocognitive studies on the disease, producing rich theoretical and clinical insights (4, 5). However, research on these predominant alterations has progressed to the detriment of less salient but still pervasive and debilitating impairments. Such is the case of language deficits.

Except for stereotypy of speech, difficulties with language production and comprehension are unmentioned in current international consensus criteria for bvFTD (3). These are also downplayed in overviews of the disease, which briefly present language as a widely preserved domain (6–8). Yet, several linguistic skills may be disrupted in bvFTD (9). For example, in a large group (10), naming deficits are as frequent as hyperorality (a core diagnostic feature) in the sample informing Rascovsky et al.'s criteria (55%). Moreover, specific language deficits often co-occur with typical bvFTD symptoms (11) and they can be observed even in pre-clinical stages (12). Also, despite lower severity, they may also resemble linguistic deficits in primary progressive aphasia (PPA) in their manifestation (13, 14) and progression rate (15). In addition, canonical atrophy patterns in bvFTD (2, 16) overlap with language-preferential regions, including the frontal, insular, cingulate, and temporal cortices (17–20). Thus, the neglect of language characterization in bvFTD research seems unwarranted.

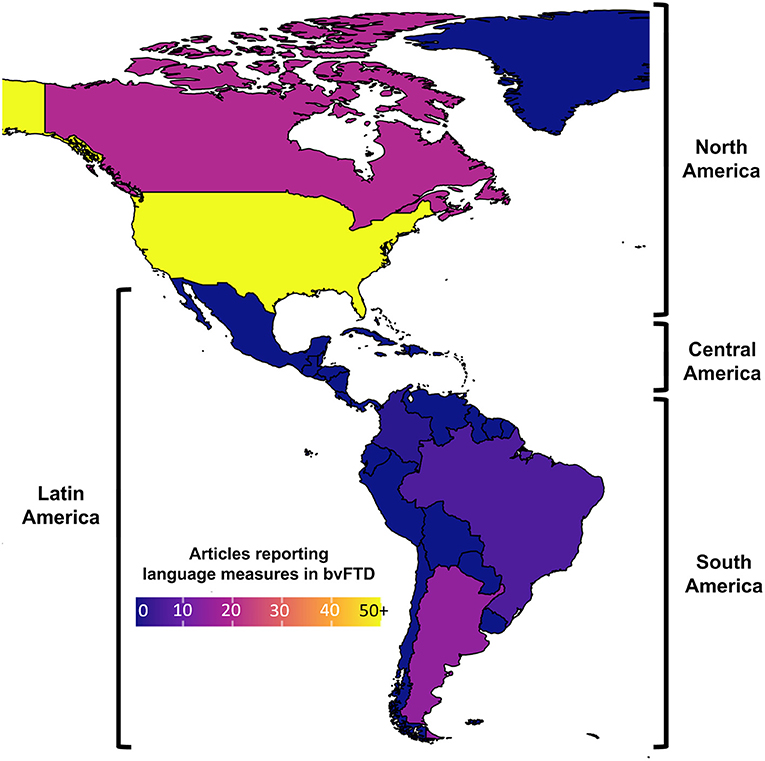

The latter point may be particularly true in Latin America, where a major increase in the prevalence of bvFTD and other dementias (1, 21, 22) calls for precise clinical phenotyping beyond classical symptoms. Language testing is notoriously scant in regional bvFTD studies. Out of 320 reports that meet inclusion criteria in a systematic review of the topic (23), only 7.5% involve Latin American samples (Figure 1). This hinders valuable opportunities to face mounting regional challenges in the fight against dementia. Indeed, while some gold-standard diagnostic and monitoring methods (e.g., biomarkers) are either limited or broadly unavailable in most local centers (22), linguistic assessments are widely accessible and capture early deficits in bvFTD cohorts across the globe (9) as well as in Latin American individuals with other non-language-dominant disorders, such as Parkinson's and Huntington's disease (24–29).

Figure 1. Articles reporting language measures in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) cohorts. A systematic review (see Supplementary Material) reveals that, unlike North America (where numerous bvFTD studies have reported language measures), Latin America has produced little evidence on the topic (ranging from low to null, depending on the country).

Moreover, findings from other languages may not generalize to those spoken in Latin America. English, for example, is typified by abundant consonant clusters, genderless nouns, few verb forms, and greater reliance on syntax than prosody for sentential distinctions (30). Conversely, Spanish and Portuguese, the two dominant languages in the region (31), present less frequent consonant clusters, gendered nominal systems, dozens of verb forms, and greater reliance on prosody than syntax to distinguish among sentence types (32). Given that different languages may recruit distinct neural mechanisms (33) and become differently affected by similar brain disruptions (34, 35), novel, language-specific efforts are needed to understand the linguistic profile of Latin American bvFTD (LA bvFTD) patients.

As an initial step, here we contextualize and review language assessments in LA bvFTD cohorts. First, we describe general linguistic features of bvFTD as revealed in research from other world regions. Second, we summarize research conducted in Latin America. Available findings came from fluency, naming, semantic processing, and comprehension tasks. Third, we provide a critical discussion of the evidence and distill its emerging empirical patterns. Finally, we outline key challenges and future directions for the field. This way, we aim to lay the groundwork for a linguistic agenda in LA bvFTD research.

Evidence from other world regions reveals general patterns of affected and spared linguistic functions across bvFTD cohorts, with marked variability for some domains (23). Available results come mainly from studies from North America, Western Europe and Australia, with a marked predominance of English over other languages.

Motor speech is mostly spared (36). Even when they present a strangled-strained voice and articulation difficulties, patients do not exhibit more distortions, false starts, or irregular articulation breakdowns than healthy controls (37). In (semi-) spontaneous tasks, patients may produce shorter segments and abnormal pauses than controls (37). Similar patterns have been documented during text reading (37). However, their production rate is typically normal (38), and so is their rate of phonetic, phonemic, and global speech errors (39).

Performance is also mostly spared in tasks that may be performed through sub-lexical mechanisms. Patients seem unimpaired in phonological manipulation as well as word and sentence repetition (13). Repetition deficits have been observed in only 5% of cases within a large bvFTD cohort (10). On the whole, segmental phonology is widely unaffected in most patients (10, 37). However, patients often exhibit single-word reading (40) and writing (13) deficits.

Conversely, lexical and semantic functions are more systematically impaired in bvFTD. Verbal fluency, across phonemic and semantic conditions, is typically compromised (41, 42). These alterations have been linked to executive deficits (42). As for word retrieval, most studies show picture naming difficulties (43), which may prove more marked for (action) verbs than (object) nouns (13). However, patients seem only sporadically affected when naming faces (44) and smells (45), and they seem unimpaired in sound naming (46). Still, the compromise of semantic abilities appears to be widespread in bvFTD, as deficits have been reported in studies tapping conceptual knowledge (47), word comprehension and definition (48), concept association (38), semantic categorization (49), analogy processing (50), and idiom comprehension (51). Semantic disruptions are also ubiquitous in connected speech. Even though diverse lexical categories are produced with normal frequency (13), patients exhibit more word-finding problems and semantic paraphasias (52). More globally, they have difficulties in accurately reporting events, guiding communication, maintaining global coherence, and organizing discourse (53).

Syntactic processing appears to be preserved in receptive tasks using simple sentences (13). However, impairments are typically observed when using more complex stimuli, such as ambiguous sentences, constructions with synthetic or thematic violations, or discourse-level tasks (51). These difficulties may be secondary to executive deficits (54). Conversely, patients exhibit correct grammar and syntax in (semi)spontaneous production tasks (39).

Briefly, evidence from regions other than Latin American reveals general linguistic patterns in bvFTD patients. Some language domains, such as motor speech and phonology, are partly preserved. Results are more mixed for syntactic skills, with difficulties appearing only during complex tasks. Finally, lexico-semantic abilities, including verbal fluency, appear to be widely impaired. These patterns represent a benchmark for interpreting results from Latin American cohorts, as reviewed next.

Following systematic criteria (see Supplementary Materials 1, 2) used in a larger systematic review of language impairments in bvFTD patients (23), we identified 24 papers reporting language assessments in LA bvFTD patients. Beyond one study assessing global language abilities, findings pertain to four main domains: phonemic fluency, semantic fluency, picture naming, and semantic processing (including comprehension). Key findings are described below and detailed in the Table 1. Also, see Supplementary Material 3 for a risk of bias assessment, revealing that only four out of the 24 papers presented high risk of bias.

One study (55) assessed global language abilities in LA bvFTD patients via the ACE-R language subscale, which includes measures of naming, comprehension, repetition, reading, and writing. Results revealed a significant impairment for patients relative to controls. Of note, deficits in the bvFTD cohorts were not milder than those observed in Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients.

LA bvFTD patients have impaired phonemic fluency relative to healthy controls (56–58, 60, 68–70, 72, 74, 75). This has been observed for both Spanish-speaking (57, 60, 74, 75) and Portuguese-speaking (68, 72) cohorts, across different age groups (mean age varying from 64.4 to 70.2 years old) and education levels (years of education ranging from 10.8 to 16.0 years). Non-significant differences were reported by Torralva et al. (62), although these results came from a smaller sample with higher MMSE scores than those reported in other studies. Also, phonemic fluency outcomes do not differ significantly between bvFTD and AD [(58, 68, 72, 73), but see (60)]. Comparisons with PPA have yielded mixed results: while some studies report better performance for bvFTD than non-fluent variant PPA and semantic variant PPA patients (74, 75), other found no significant difference between groups (60, 69, 70).1 Phonemic fluency performance in LA bvFTD patients has been shown to correlate with the volume of core affected regions –e.g., the bilateral insula and putamen, the right amygdala, fusiform and inferior frontal gyri, and the left superior temporal and orbitofrontal cortices (57).

These impairments may be linked to overall cognitive functioning. LA bvFTD patients with global cognitive difficulties are outperformed by both healthy controls and cognitively preserved LA bvFTD patients (59, 63, 71, 76), there being no difference between the latter two groups [(59, 71, 76), but see (63)]. Phonemic fluency may also be associated with executive (59, 80) and mnesic (59) skills.

The links between this domain and social cognitive functioning are less clear. Phonemic fluency does not seem to be associated with measures of theory of mind (73, 76), empathy (56), or global socio-cognitive skills (76). Also, no difference has been reported in phonemic fluency scores between patients with utilitarian and non-utilitarian moral profiles (80). Note that, beyond social cognition domains, similar phonemic fluency outcomes have been reported between apathetic and disinhibited patients (61). However, positive correlations have been reported between phonemic fluency scores and the Reading-the-Mind-in-the-Eyes test, a Faux-Pas task (63), and a decision-making task (71).

In short, phonemic fluency appears to be compromised in LA bvFTD patients. The severity of this impairment resembles that observed in AD and may even reach the degree of impairment seen in non-fluent and semantic PPA. Reported deficits seem driven by wider executive impairment, whereas their relationship to social cognitive functioning remains poorly understood.

Semantic fluency assessments also reveal systematic deficits in LA bvFTD samples (58, 67–70, 72, 74, 75). As is the case with phonemic fluency, this impairment is consistent for both Spanish (74, 75) and Portuguese (67, 68, 72), in cohorts with different mean ages (varying from 61.9 to 70.2 years old) and education levels (year of education ranging from 8.7 to 16.0 years). In particular, emerging evidence (67) suggests that, compared with healthy controls, LA bvFTD patients produce fewer and smaller semantic clusters (words retrieved according to semantic subcategories such as pets, birds, or felines, for animals) as well as fewer switches (shifts from one semantic subcategory to another). Semantic fluency deficits in LA bvFTD patients seem less strong than those observed in non-fluent and semantic variant PPA [(70, 74, 75), but see (69)] but as severe as those of patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment (67) and AD (64, 67, 68, 72, 73).

Such difficulties may be related to global cognitive alterations. Indeed, sub-group analyses reveal that deficits are present in cognitively compromised, but not in cognitive spared, LA bvFTD patients (71, 76). In a similar vein, Wajman et al. (67) found significant positive correlations between semantic fluency measures and MMSE scores.

Additional evidence suggests a link with social cognition skills. Although semantic fluency scores may not differ between patients with utilitarian and non-utilitarian moral profiles (80), they are correlated with decision-making scores (71). Semantic fluency in LA bvFTD cohorts may also be influenced by cerebrovascular disease, as patients without such comorbidity had lower scores on specific categories (animals) (66). Finally, there seems to be no difference in semantic fluency between bvFTD patients with and without psychiatric history (65).

In sum, semantic fluency is systematically impaired in LA bvFTD patients. Deficits are less marked than in PPA variants, but they prove comparable to those of persons with mild cognitive impairment or AD. Such difficulties seem related to more global cognitive and socio-cognitive deficits.

Picture naming appears to be mostly impaired in LA bvFTD samples. Available evidence comes from Spanish speakers aged between 65 and 70, with a range of roughly 12–15 years of education. Most studies employed the Boston Naming Test, revealing significant differences between patients and controls (60, 70, 71, 74–76); but see (70). Interestingly, no significant deficits were revealed via an experimental naming test designed for AD (75). Moreover, separate studies reported that naming performance in LA bvFTD patients was better than in non-fluent variant and semantic variant PPA (75) and heterogeneous PPA cohorts (70).

Naming deficits might be related to the patients' global cognitive impairment levels, as they prove significantly greater in low- vs. high-functioning LA bvFTD cohorts (59, 71, 76). Indeed, normal naming performance has been reported in the latter subgroup (59). Conversely, picture naming did not differ between patients with utilitarian and non-utilitarian moral profiles (80) or prior history of stroke or silent brain infarcts (66).

Briefly, picture naming seems compromised in LA bvFTD patients, though not as markedly as in PPA variants. These deficits might be driven by the patients' cognitive status, but they seem uninfluenced by socio-cognitive abilities or neurovascular events.

Concept association, as tapped with the Pyramids and Palm Trees test, seems to be impaired in LA bvFTD cohorts (59, 62, 70). However, this pattern seems driven by cognitively impaired patients. In fact, these are outperformed by high-functioning ones, who actually reach normal scores (62). Patients also exhibit deficits in proverb comprehension (74, 75), suggesting impaired figurative language skills. Still, these difficulties are significantly less marked than those of semantic variant PPA and non-fluent variant PPA patients (75).

Conversely, comprehension of increasingly complex commands, as captured by the Token Test, seems globally preserved in LA bvFTD individuals (62, 70). However, this domain also seems sensitive to cognitive decline, as poorer performance has been observed in low- relative to high-functioning patients (76). Furthermore, this domain does not seem to differ between patients with utilitarian and non-utilitarian moral profiles (80).

In sum, LA bvFTD patients seem to exhibit concept association and figurative language comprehension deficits, with preserved abilities to grasp verbal commands. At least some of these patterns might be driven by overall cognitive skills.

Though moderate in quantity and scope, existing findings allow the identification of potential empirical patterns. First, LA bvFTD cohorts exhibit systematic deficits in phonemic and semantic fluency. This impairment is consistent across education levels, age ranges, and in the two languages most widely spoken by Latin Americans: Spanish and Portuguese (31). Interestingly, fluency is also the most consistently disrupted domain across bvFTD patients from other regions, yielding deficits in 76% of cases (10). The detection of naming deficits also aligns with reports showing their presence in more than half of patients (10), matching the incidence of hyperorality, a core diagnostic symptom (3). Difficulties have also been observed in tasks requiring semantic processing and comprehension of complex commands, probably driven by global cognitive deficits.

Despite the widespread dismissal of language deficits in bvFTD, such patterns are not fully surprising. Indeed, the above domains have all been linked to brain regions canonically disrupted in bvFTD. This is true of phonemic fluency, subserved by inferior frontal, insular, and medial temporal regions (81); semantic fluency, linked to frontal, posterior temporal, and inferior parietal regions (81); naming, associated with middle temporal, angular, dorsolateral prefrontal, and inferior frontal regions (82, 83); and semantic processing, underpinned by temporal, inferior/medial prefrontal, occipital, and subcortical regions (84). Compatibly, limited evidence in our review shows that phonemic fluency deficits in Spanish-speaking bvFTD patients are associated with atrophy in inferior frontal, orbitofrontal, and anterior, superior and mesial temporal regions (57). Such links reinforce the relevance of language deficits in the disease.

Comparisons with other diseases illuminate the severity of these impairments in LA bvFTD patients. Deficits in semantic fluency (60, 69, 70), naming (70, 75), semantic association, and comprehension (75) are milder than in PPA variants, which are mainly typified by language impairments (85). One study reported comparable semantic fluency difficulties in LA bvFTD and non-fluent PPA patients (69), potentially driven by partly similar atrophy patterns along frontal regions. Phonemic fluency, which hinges on both linguistic and executive control mechanisms, more consistently yielded similar deficits in LA bvFTD and non-fluent PPA (60, 69, 70), which is mainly distinguished by disruption of language-sensitive fronto-insular networks (85). The latter point could suggest that impaired performance in each syndrome might be driven by different factors, such as executive dysfunction in LA bvFTD and linguistic impairment in PPA (39).

More interestingly, several domains seem as markedly impaired in bvFTD as in AD, a disease in which specific verbal dysfunctions range from frequent (in amnestic presentations) to systematic (in linguistic presentations) (86). In our review, comparable outcomes between these diseases have been reported for global language skills, as evaluated with the ACE-R language scale (55), as well as phonemic (58, 68, 72, 73) and semantic (64, 67, 68, 72, 73) fluency tasks. The same pattern has been reported among speakers of English (87) and Italian (88). However, other domains recruiting both linguistic and executive mechanisms, such as picture naming and syntax, may be differentially affected in LA bvFTD and AD (13, 89), calling for further research on cross-nosological and disease-specific markers.

More generally, evidence from Latin America aligns with global findings supporting the relevance of linguistic assessments in bvFTD, even if these are not primarily affected in the disease (9). In the same vein, previous research has emphasized the usefulness of social cognition assessments in PPA variants, although these syndromes are characterized primarily by language deficits (90). Such approaches underscore the clinical value of assessments that go beyond core symptoms, leading to more exhaustive characterizations to establish individual profiles and personalized plans to treat each patient's more salient disruptions. At the same time, they align with transnosological and dimensional perspectives that frame cognitive outcomes in a continuum between normal and pathological extremes cutting across diseases with different core symptomatology (4). Even deficits that escape core diagnostic criteria may be informative for clinical purposes.

The study of language impairments in bvFTD across Latin America is already informative and promising. However, it is marked by important gaps, especially when compared to work conducted elsewhere. First, the evidence is scant and it secondarily covers only a few, coarse-grained domains, whereas research in other world regions proves more abundant, varied, and granular. In addition, few studies have examined associations between linguistic outcomes, non-verbal cognitive skills, and neural correlates, while none has employed longitudinal designs to evaluate language impairment progression. This hinders the detection of robust and clinically useful patterns, as well as the integration of local results with global findings. The scenario is further complicated by the overlap of patients across reports from the same groups, a problem that also challenges interpretability of findings in other parts of the world.

Second, despite the vast extension of the territory, available results come from only a few centers distributed in three countries (Argentina, Brazil, and Colombia). Accordingly, existing findings may fail to represent the diversity of Latin Americans across regional subgroups–a factor known to affect other aspects of dementia presentation (91). More extensive recruitment across regional clinics and hospitals would be critical to extend the cross-national scope of the evidence. Finally, available data comes only from Portuguese- and Spanish-speaking cohorts, which falls short of capturing the region's linguistic diversity, with over 450 languages (31) and an even larger number of dialects (92). Note that different languages (34), and even different dialects of the same language (93, 94), may become differentially affected by brain disease, so that existing results may not be readily extrapolated across the territory.

Future work should strongly aim to cover these gaps, mainly by acknowledging diversity as a pressing matter and encouraging the exploration of culture-specific variables in a cross-regional agenda. This could be achieved through multicentric efforts, such as those spearheaded by the Consortium to Expand Dementia Research in Latin America–ReDLat (95), offering adequate sample sizes, socio-cultural and dialectal diversity, and ecologically valid measures. In fact, ReDLat is already poised to implement classical (e.g., picture naming) and cutting-edge (e.g., automated speech analyses) tools capturing linguistic features in over 1,000 LA bvFTD patients spanning six countries, two languages (Spanish and Portuguese), and numerous dialects. Moreover, the consortium's multicentric structure is already being leveraged to launch language-focused projects, including novel assessments in bvFTD and AD samples through a combination of automated (acoustic and textual) measures, gold-standard multi-level tests, and validated language profile questionnaires. In the near future, the cross-dialectal scope of these efforts could be fruitfully extended beyond the region through direct contrasts between bvFTD cohorts from Latin America, Spain, and Portugal. This would also cater for a more balanced representation of sites from different countries, as language measures, so far, have been reported in only three bvFTD studies from Spain (96–98) and one from Portugal (99).

Furthermore, these limitations also apply to several other world regions where language studies in bvFTD range from incipient to fully absent. This is the case, for instance, with African countries, most Asian countries, and Russia. Therefore, from a more global perspective, our present call for further Latin American research on the topic should be seen as an instantiation of a broader, cross-national need to be met by the field.

This review also highlights the need for Latin American researchers and clinicians to use more sensitive and specific language measures. One of the most systematically assessed domains in LA bvFTD patients is verbal fluency. Although highly useful to detect cognitive impairment in this population, fluency tests are not sufficient to investigate language functioning in bvFTD, calling for more specific tasks.

The Boston Naming Test was the most frequently used naming task in the reviewed studies. However, this test can underestimate Spanish proficiency (100). In this sense, the Multilingual Naming Test might be more culturally and linguistically appropriate to investigate naming abilities in monolingual and multilingual Spanish speakers, and it has been shown to be useful clinically in neurodegenerative populations (101).

The Pyramids and Palm Trees Test was the most frequently used semantic task in our review. As semantic memory is one of the most culturally specific cognitive domains, researchers have developed and validated a culturally and linguistically appropriate version for Spanish speakers, the Pyramids and Pharaohs Test (102). In addition to being shorter (20 vs. 52 trials), this new version also shows a higher sensitivity and specificity to semantic impairments in a Spanish-speaking population.

Finally, the Token Test, which was used frequently in primary studies in the present review, appears appropriate for Latin American patients and it has Spanish and Portuguese norms (103, 104). Nonetheless, no study has investigated motor speech, phonology or syntax in LA bvFTD patients. Prosodic and discourse-based measures, which have also shown to be extremely useful to characterize language impairments in bvFTD patients, have not been used either. Besides a few general language instruments, such as the Bilingual Aphasia Test (105), the Communicative Abilities in Daily Living battery (106), and the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (107), there is a dearth of fine-grained tools for assessing language in Latin American individuals. The development of such instruments could stimulate regional research on bvFTD and other neurodegenerative conditions.

Moreover, major strides could be made by incorporating automated speech analysis tools (108, 109), which allow capturing multiple acoustic (e.g., prosodic, articulatory) and linguistic (e.g., lexico-semantic, morphosyntactic) features from brief excerpts of natural speech. Relative to standard assessments, this approach presents numerous advantages (e.g., low cost, objective results, ecological validity, scalability), and it has already proven sensitive to bvFTD patients from other world regions (110). In line with recent works on Latin American patients with other neurodegenerative disorders (25, 26), automated speech assessments could open new vistas for translational research on regional bvFTD cohorts.

The prominence of behavioral and personality changes in bvFTD may have led to a partial dismissal of other cognitive deficits, including linguistic ones. This is unfortunate for underserved regions, such as Latin America, given that language assessments in bvFTD may be sensitive, discriminative, less costly, and more scalable than other diagnostic and monitoring methods. Our review indicates that deficits in verbal fluency, naming, and semantic domains are common and informative across LA bvFTD cohorts, but it also highlights the paucity of evidence, the lack of studies employing fine-grained and cutting-edge tools, and the poor coverage of languages and dialects across the region. Looking forward, multicentric approaches to language in LA bvFTD samples could be of great clinical value, paving the way for more thorough characterizations of patient profiles and novel avenues to support mainstream diagnostic tests.

AMG developed the study concept and the study design. AG and MM performed the literature review. AG, MD, MM, and AMG interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was partially supported by CONICET; ANID/FONDECYT Regular (1210176 and 1210195); Programa Interdisciplinario de Investigación Experimental en Comunicación y Cognición (PIIECC), Facultad de Humanidades, USACH; and the Multi-Partner Consortium to Expand Dementia Research in Latin America (ReDLat), funded by the National Institutes of Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AG057234, an Alzheimer's Association grant SG-20-725707, the Rainwater Foundation; and the Global Brain Health Institute). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of these organizations. MM was supported by post-doctoral fellowships from Canadian Health Institutes of Research and Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2021.702770/full#supplementary-material

1. Custodio N, Wheelock A, Thumala D, Slachevsky A. Dementia in Latin America: epidemiological evidence and implications for public policy. Front Aging Neurosci. (2017) 9:221. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00221

2. Piguet O, Hornberger M, Mioshi E, Hodges JR. Behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia: diagnosis, clinical staging, and management. Lancet Neurol. (2011) 10:162-72. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70299-4

3. Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, Mendez MF, Kramer JH, Neuhaus J, et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain J Neurol. (2011) 134:2456-77. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr179

4. Ibáñez A, García AM, Esteves S, Yoris A, Muñoz E, Reynaldo L, et al. Social neuroscience: undoing the schism between neurology and psychiatry. Soc Neurosci. (2018) 13:1–39. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2016.1245214

5. Lanata SC, Miller BL. The behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) syndrome in psychiatry. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2016) 87:501-11. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-310697

6. Bott NT, Radke A, Stephens ML, Kramer JH. Frontotemporal dementia: Diagnosis, deficits and management. Neurodegen Dis Manag. (2014) 4:439-54. doi: 10.2217/nmt.14.34

7. Harciarek M, Cosentino S. Language, executive function and social cognition in the diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia syndromes. Int Rev Psychiatry (Abingdon, England). (2013) 25:178-96. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2013.763340

8. Piguet O, Hodges JR. Behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia: an update. Dementia Neuropsychol. (2013) 7:10-8. doi: 10.1590/S1980-57642013DN70100003

9. Garcia AM, DeLeon J, Tee BL. Neurodegenerative disorders of speech and language: non-language-dominant disease. In: Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology. Amsterdam: Elsevier (2020).

10. Saxon JA, Thompson JC, Jones M, Harris JM, Richardson AM, Langheinrich T, et al. Examining the language and behavioural profile in FTD and ALS-FTD. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2017) 88:675-80. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-315667

11. Harris JM, Jones M, Gall C, Richardson AMT, Neary D, du Plessis D, et al. Co-occurrence of language and behavioural change in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Dementia Geriatr Cogn Disord Extra. (2016) 6:205-13. doi: 10.1159/000444848

12. Cheran G, Wu L, Lee S, Manoochehri M, Cines S, Fallon E, et al. Cognitive indicators of preclinical behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia in MAPT carriers. J Int Neuropsychol Soc JINS. (2019) 25:184-94. doi: 10.1017/S1355617718001005

13. Hardy CJD, Buckley AH, Downey LE, Lehmann M, Zimmerer VC, Varley RA, et al. The language profile of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. (2016) 50:359-71. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150806

14. Warren JD, Rohrer JD, Rossor MN. Clinical review. Frontotemporal dementia. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). (2013) 347:f4827. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4827

15. Blair M, Marczinski CA, Davis-Faroque N, Kertesz A. A longitudinal study of language decline in Alzheimer's disease frontotemporal dementia. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. (2007) 13:237-45. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070269

16. Seeley WW. Frontotemporal dementia neuroimaging: a guide for clinicians. Front Neurol Neurosci. (2009) 24:160-7. doi: 10.1159/000197895

17. Ardila A, Bernal B, Rosselli M. How localized are language brain areas? A review of brodmann areas involvement in oral language. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. (2016) 31:112-22. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acv081

18. Hagoort P. The neurobiology of language beyond single-word processing. Science (New York, N.Y.). (2019) 366:55-8. doi: 10.1126/science.aax0289

19. Hickok G. The functional neuroanatomy of language. Phys Life Rev. (2009) 6:121-43. doi: 10.1016/j.plrev.2009.06.001

20. Oh A, Duerden EG, Pang EW. The role of the insula in speech and language processing. Brain Lang. (2014) 135:96-103. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2014.06.003

21. GBD 2016 Dementia Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. (2019) 18:88-106. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30403-4

22. Parra MA, Baez S, Sedeño L, Gonzalez Campo C, Santamaría-García H, Aprahamian I, et al. Dementia in Latin America: paving the way toward a regional action plan. Alzheimers Dementia J Alzheimers Assoc. (2021) 17:295-313. doi: 10.1002/alz.12202

23. Geraudie A, Battista P, García AM, Allen IE, Miller ZA, Gorno-Tempini ML, et al. Speech and language impairments in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. MedRxiv. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2021.07.10.21260313

24. Birba A, García-Cordero I, Kozono G, Legaz A, Ibáñez A, Sedeño L, et al. Losing ground: Frontostriatal atrophy disrupts language embodiment in Parkinson's and Huntington's disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2017) 80:673-87. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.07.011

25. Eyigoz E, Courson M, Sedeño L, Rogg K, Orozco-Arroyave JR, Nöth E, et al. From discourse to pathology: automatic identification of Parkinson's disease patients via morphological measures across three languages. Cortex J Devoted Study Nervous Syst Behav. (2020) 132:191-205. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2020.08.020

26. García AM, Carrillo F, Orozco-Arroyave JR, Trujillo N, Vargas Bonilla JF, Fittipaldi S, et al. How language flows when movements don't: an automated analysis of spontaneous discourse in Parkinson's disease. Brain Lang. (2016) 162:19-28. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2016.07.008

27. García AM, Sedeño L, Trujillo N, Bocanegra Y, Gomez D, Pineda D, et al. Language deficits as a preclinical window into parkinson's disease: evidence from asymptomatic parkin dardarin mutation carriers. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. (2017) 23:150-8. doi: 10.1017/S1355617716000710

28. García AM, Bocanegra Y, Herrera E, Moreno L, Carmona J, Baena A, et al. Parkinson's disease compromises the appraisal of action meanings evoked by naturalistic texts. Cortex J Devoted Study Nerv Syst Behav. (2018) 100:111-26. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2017.07.003

29. Salmazo-Silva H, Parente MA, de MP, Rocha MS, Baradel RR, Cravo AM, et al. Lexical-retrieval and semantic memory in Parkinson's disease: The question of noun and verb dissociation. Brain Lang. (2017) 165:10-20. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2016.10.006

30. Halliday MAK, Matthiessen C, Halliday M. An Introduction to Functional Grammar. Birmingham: Routledge (2014). doi: 10.4324/9780203783771

31. Eberhard D, Simons GF. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. 23rd ed. Dallas: Sil International, Global Publishing (2020).

32. Wetzels WL, Menuzzi S, Costa J. The Handbook of Portuguese Linguistics Hoboken, NJ: Wiley (2020).

33. Evans N, Levinson SC. The myth of language universals: language diversity and its importance for cognitive science. Behav Brain Sci. (2009) 32:429-48; discussion 448–494. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0999094X

34. Canu E, Agosta F, Battistella G, Spinelli EG, DeLeon J, Welch AE, et al. Speech production differences in English and Italian speakers with nonfluent variant PPA. Neurology. (2020) 94:e1062-72. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008879

35. Paradis M. The need for awareness of aphasia symptoms in different languages. J Neurolinguist. (2001) 14:85-91. doi: 10.1016/S0911-6044(01)00009-4

36. Deleon J, Gesierich B, Besbris M, Ogar J, Henry ML, Miller BL, et al. Elicitation of specific syntactic structures in primary progressive aphasia. Brain Lang. (2012) 123:183-90. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2012.09.004

37. Vogel AP, Poole ML, Pemberton H, Caverlé MWJ, Boonstra FMC, Low E, et al. Motor speech signature of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: refining the phenotype. Neurology. (2017) 89:837-44. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004248

38. Ash S, Evans E, O'Shea J, Powers J, Boller A, Weinberg D, et al. Differentiating primary progressive aphasias in a brief sample of connected speech. Neurology. (2013) 81:329-36. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829c5d0e

39. Ash S, Nevler N, Phillips J, Irwin DJ, McMillan CT, Rascovsky K, et al. A longitudinal study of speech production in primary progressive aphasia and behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain Lang. (2019) 194:46-57. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2019.04.006

40. Downey LE, Mahoney CJ, Buckley AH, Golden HL, Henley SM, Schmitz N, et al. White matter tract signatures of impaired social cognition in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. NeuroImage Clin. (2015) 8:640-51. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.06.005

41. Irwin DJ, McMillan CT, Xie SX, Rascovsky K, Van Deerlin VM, Coslett HB, et al. Asymmetry of post-mortem neuropathology in behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia. Brain J Neurol. (2018) 141:288-301. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx319

42. Libon DJ, McMillan C, Gunawardena D, Powers C, Massimo L, Khan A, et al. Neurocognitive contributions to verbal fluency deficits in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. (2009) 73:535-42. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b2a4f5

43. Whitwell JL, Przybelski SA, Weigand SD, Ivnik RJ, Vemuri P, Gunter JL, et al. Distinct anatomical subtypes of the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia: a cluster analysis study. Brain J Neurol. (2009) 132:2932-46. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp232

44. Kamminga J, Kumfor F, Burrell JR, Piguet O, Hodges JR, Irish M. Differentiating between right-lateralised semantic dementia and behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia: an examination of clinical characteristics and emotion processing. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2015) 86:1082-8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-309120

45. Luzzi S, Snowden JS, Neary D, Coccia M, Provinciali L, Lambon Ralph MA. Distinct patterns of olfactory impairment in Alzheimer's disease, semantic dementia, frontotemporal dementia, corticobasal degeneration. Neuropsychologia. (2007) 45:1823-31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.12.008

46. Lin P-H, Chen H-H, Chen N-C, Chang W-N, Huang C-W, Chang Y-T, et al. Anatomical correlates of non-verbal perception in dementia patients. Front Aging Neurosci. (2016) 8:207. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00207

47. Irish M, Eyre N, Dermody N, O'Callaghan C, Hodges JR, Hornberger M, et al. Neural substrates of semantic prospection-evidence from the dementias. Front Behav Neurosci. (2016) 10:96. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00096

48. Chen Y, Kumfor F, Landin-Romero R, Irish M, Hodges JR, Piguet O. Cerebellar atrophy and its contribution to cognition in frontotemporal dementias. Ann Neurol. (2018) 84:98-109. doi: 10.1002/ana.25271

49. Hughes LE, Nestor PJ, Hodges JR, Rowe JB. Magnetoencephalography of frontotemporal dementia: spatiotemporally localized changes during semantic decisions. Brain A J Neurol. (2011) 134:2513-22. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr196

50. Krawczyk DC, Morrison RG, Viskontas I, Holyoak KJ, Chow TW, Mendez MF, et al. Distraction during relational reasoning: the role of prefrontal cortex in interference control. Neuropsychologia. (2008) 46:2020-32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.02.001

51. Luzzi S, Baldinelli S, Ranaldi V, Fiori C, Plutino A, Fringuelli FM, et al. The neural bases of discourse semantic and pragmatic deficits in patients with frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Cortex J Devoted Study Nervous Syst Behav. (2020) 128:174-91. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2020.03.012

52. Wilson SM, Henry ML, Besbris M, Ogar JM, Dronkers NF, Jarrold W, et al. Connected speech production in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Brain J Neurol. (2010) 133:2069-88. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq129

53. Healey M, Spotorno N, Olm C, Irwin DJ, Grossman M. Cognitive neuroanatomic accounts of referential communication in focal dementia. ENeuro. (2019) 6:1–35. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0488-18.2019

54. Peelle JE, Cooke A, Moore P, Vesely L, Grossman M. Syntactic and thematic components of sentence processing in progressive nonfluent aphasia and nonaphasic frontotemporal dementia. J Neurolinguist. (2007) 20:482-94. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2007.04.002

55. Lima-Silva TB, Bahia VS, Carvalho VA, Guimarães HC, Caramelli P, Balthazar MLF, et al. Direct and indirect assessments of activities of daily living in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. (2015) 28:19-26. doi: 10.1177/0891988714541874

56. Baez S, Manes F, Huepe D, Torralva T, Fiorentino N, Richter F, et al. Primary empathy deficits in frontotemporal dementia. Front Aging Neurosci. (2014) 6:262. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00262

57. Baez S, Pinasco C, Roca M, Ferrari J, Couto B, García-Cordero I, et al. Brain structural correlates of executive and social cognition profiles in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and elderly bipolar disorder. Neuropsychologia. (2019) 126:159-69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.02.012

58. Gleichgerrcht E, Roca M, Manes F, Torralva T. Comparing the clinical usefulness of the Institute of Cognitive Neurology (INECO) frontal screening (IFS) and the frontal assessment battery (FAB) in frontotemporal dementia. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. (2011) 33:997-1004. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2011.589375

59. Roca M, Manes F, Gleichgerrcht E, Watson P, Ibáñez A, Thompson R, et al. Intelligence and executive functions in frontotemporal dementia. Neuropsychologia. (2013) 51:725-30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.01.008

60. Russo G, Russo MJ, Buyatti D, Chrem P, Bagnati P, Fernández Suarez M, et al. Utility of the Spanish version of the FTLD-modified CDR in the diagnosis and staging in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J Neurol Sci. (2014) 344:63-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.06.024

61. Santamaría-García H, Reyes P, García A, Baéz S, Martinez A, Santacruz JM, et al. First symptoms neurocognitive correlates of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. (2016) 54:957-70. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160501

62. Torralva T, Kipps CM, Hodges JR, Clark L, Bekinschtein T, Roca M, et al. The relationship between affective decision-making and theory of mind in the frontal variant of fronto-temporal dementia. Neuropsychologia. (2007) 45:342-9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.05.031

63. Torralva T, Gleichgerrcht E, Torres Ardila MJ, Roca M, Manes FF. Differential cognitive and affective theory of mind abilities at mild and moderate stages of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Cogn Behav Neurol. (2015) 28:63-70. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0000000000000053

64. Bahia VS, Viana R. Accuracy of neuropsychological tests and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory in differential diagnosis between Frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Dementia Neuropsychol. (2009) 3:332–36. doi: 10.1590/S1980-57642009DN30400012

65. Gambogi LB, Guimarães HC, de Souza LC, Caramelli P. Long-term severe mental disorders preceding behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: frequency clinical correlates in an outpatient sample. J Alzheimers Dis. (2018) 66:1577-85. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180528

66. Torralva T, Sposato LA, Riccio PM, Gleichgerrcht E, Roca M, Toledo JB, et al. Role of brain infarcts in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: Clinicopathological characterization in the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center database. Neurobiol Aging. (2015) 36:2861-8. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.06.026

67. Wajman JR, Cecchini MA, Bertolucci PHF, Mansur LL. Quanti-qualitative components of the semantic verbal fluency test in cognitively healthy controls, mild cognitive impairment, dementia subtypes. Appl Neuropsychol Adult. (2019) 26:533-42. doi: 10.1080/23279095.2018.1465426

68. Bahia VS, Cecchini MA, Cassimiro L, Viana R, Lima-Silva TB, de Souza LC, et al. The accuracy of INECO frontal screening in the diagnosis of executive dysfunction in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. (2018) 32:314-9. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000255

69. Couto B, Manes F, Montañés P, Matallana D, Reyes P, Velasquez M, et al. Structural neuroimaging of social cognition in progressive non-fluent aphasia and behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia. Front Hum Neurosci. (2013) 7:467. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00467

70. Gleichgerrcht E, Torralva T, Roca M, Szenkman D, Ibanez A, Richly P, et al. Decision making cognition in primary progressive aphasia. Behav Neurol. (2012) 25:45-52. doi: 10.1155/2012/606285

71. Manes F, Torralva T, Ibáñez A, Roca M, Bekinschtein T, Gleichgerrcht E. Decision-making in frontotemporal dementia: clinical, theoretical and legal implications. Dementia Geriatr Cogn Disord. (2011) 32:11-7. doi: 10.1159/000329912

72. Mariano LI, O'Callaghan C, Guimarães HC, Gambogi LB, da Silva TBL, Yassuda MS, et al. Disinhibition in frontotemporal dementia Alzheimer's disease: a neuropsychological behavioural investigation. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. (2020) 26:163-71. doi: 10.1017/S1355617719000973

73. Ramanan S, de Souza LC, Moreau N, Sarazin M, Teixeira AL, Allen Z, et al. Determinants of theory of mind performance in Alzheimer's disease: a data-mining study. Cortex J Devoted Study Nerv Syst Behav. (2017) 88:8-18. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2016.11.014

74. Reyes P, Ortega-Merchan MP, Rueda A, Uriza F, Santamaria-García H, Rojas-Serrano N, et al. Functional connectivity changes in behavioral, semantic, and nonfluent variants of frontotemporal dementia. Behav Neurol. (2018) 2018:9684129. doi: 10.1155/2018/9684129

75. Reyes PA, Rueda ADP, Uriza F, Matallana DL. Networks disrupted in linguistic variants of frontotemporal dementia. Front Neurol. (2019) 10:903. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00903

76. Torralva T, Roca M, Gleichgerrcht E, Bekinschtein T, Manes F. A neuropsychological battery to detect specific executive and social cognitive impairments in early frontotemporal dementia. Brain J Neurol. (2009) 132:1299-309. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp041

77. Montanes P, Goldblum MC, Boller F. The naming impairment of living and nonliving items in Alzheimer's disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. (1995) 1:39–48. doi: 10.1017/S1355617700000084

78. Santamaría-García H, Baez S, Reyes P, Santamaría-García JA, Santacruz-Escudero JM, Matallana D, et al. (2017). A lesion model of envy and Schadenfreude?: Legal, deservingness and moral dimensions as revealed by neurodegeneration. Brain: A J Neurol., 140, 3357–3377. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx269

79. Snodgrass JG, Feenan K. Priming effects in picture fragment completion: support for the perceptual closure hypothesis. J Exp Psychol Gen. (1990) 119:276.

80. Gleichgerrcht E, Torralva T, Roca M, Pose M, Manes F. The role of social cognition in moral judgment in frontotemporal dementia. Soc Neurosci. (2011) 6:113-22. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2010.506751

81. Vonk JMJ, Rizvi B, Lao PJ, Budge M, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, et al. Letter and category fluency performance correlates with distinct patterns of cortical thickness in older adults. Cerebral Cortex (New York, N.Y.: 1991). (2019) 29:2694-700. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhy138

82. Garn CL, Allen MD, Larsen JD. An fMRI study of sex differences in brain activation during object naming. Cortex J Devoted Study Nerv Syst Behav. (2009) 45:610-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2008.02.004

83. Price CJ, Moore CJ, Humphreys GW, Frackowiak RS, Friston KJ. The neural regions sustaining object recognition and naming. Proc Biol Sci. (1996) 263:1501-7. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0219

84. Fang Y, Han Z, Zhong S, Gong G, Song L, Liu F, et al. The semantic anatomical network: evidence from healthy and brain-damaged patient populations. Hum Brain Map. (2015) 36:3499-515. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22858

85. Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, Kertesz A, Mendez M, Cappa SF, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. (2011) 76:1006-14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6

86. Verma M, Howard RJ. Semantic memory and language dysfunction in early Alzheimer's disease: a review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2012) 27:1209-17. doi: 10.1002/gps.3766

87. Hodges JR, Patterson K, Ward R, Garrard P, Bak T, Perry R, et al. The differentiation of semantic dementia and frontal lobe dementia (temporal and frontal variants of frontotemporal dementia) from early Alzheimer's disease: a comparative neuropsychological study. Neuropsychology. (1999) 13:31-40. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.13.1.31

88. Filippi M, Basaia S, Canu E, Imperiale F, Meani A, Caso F, et al. Brain network connectivity differs in early-onset neurodegenerative dementia. Neurology. (2017) 89:1764-72. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004577

89. Hutchinson AD, Mathias JL. Neuropsychological deficits in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analytic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2007) 78:917-28. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.100669

90. Fittipaldi S, Ibanez A, Baez S, Manes F, Sedeno L, Garcia AM. More than words: social cognition across variants of primary progressive aphasia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2019) 100:263-84. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.02.020

91. Parra MA, Baez S, Allegri R, Nitrini R, Lopera F, Slachevsky A, et al. Dementia in Latin America: assessing the present and envisioning the future. Neurology. (2018) 90:222-31. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004897

92. Lipski JM. Dialects of Spanish and Portuguese. In: Boberg C, Nerbonne J, Watt D, editors. The Handbook of Dialectology. 1st ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc (2018).

93. Fabbro F, Paradis M. Differential impairments in four multilingual patients with subcortical lesions. In: Paradis M, editor. Aspects of Bilingual Aphasia. 1st Edn. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Pub Ltd (1995). p. 139-76.

94. García AR. Translating with an Injured Brain: Neurolinguistic Aspects of Translation as Revealed by Bilinguals with Cerebral Lesions. Meta: Translators' J. (2015) 60:112–34.

95. Ibanez A, Yokoyama JS, Possin KL, Matallana D, Lopera F, Nitrini R, et al. The multi-partner consortium to expand dementia research in Latin America (ReDLat): driving multicentric research and implementation science. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:631722. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.631722

96. Fernández-Matarrubia M, Matías-Guiu JA, Cabrera-Martín MN, Moreno-Ramos T, Valles-Salgado M, Carreras JL, et al. Episodic memory dysfunction in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: a clinical and FDG-PET study. J Alzheimers Dis. (2017) 57:1251-64. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160874

97. Pozueta A, Lage C, García-Martínez M, Kazimierczak M, Bravo M, López-García S, et al. Cognitive behavioral profiles of left right semantic dementia: differential diagnosis with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. (2019) 72:1129-44. doi: 10.3233/JAD-190877

98. Pozueta A, Lage C, Martínez MG, Kazimierczak M, Bravo M, López-García S, et al. A brief drawing task for the differential diagnosis of semantic dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. (2019) 72:151-60. doi: 10.3233/JAD-190660

99. Lemos R, Duro D, Simões MR, Santana I. The free and cued selective reminding test distinguishes frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer's disease. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. (2014) 29:670-9. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acu031

100. Gollan TH, Weissberger GH, Runnqvist E, Montoya RI, Cera CM. Self-ratings of spoken language dominance: a multi-lingual naming test (MINT) and preliminary norms for young and aging Spanish-english Bilinguals. Bilingualism (Cambridge, England). (2012) 15:594-615. doi: 10.1017/S1366728911000332

101. Ivanova I, Salmon DP, Gollan TH. The multilingual naming test in Alzheimer's disease: clues to the origin of naming impairments. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. (2013) 19:272-83. doi: 10.1017/S1355617712001282

102. Martinez Cuitiño M, Barreyro JP. Pyramids and palm trees or pyramids and pharaohs?: adaptation and validation of semantic association test to the spanish. Interdisciplinaria. (2010) 27:247–60.

103. Fontanari JL. O ≪ token test ≫: Elegância e concisäo na avaliaçäo da compreensäo do afásico. Validaçäo da versäo reduzida de Renzi para o português. Neurobiologia. (1989) 52:177-218.

104. Peña-Casanova J, Quiñones-Úbeda S, Gramunt-Fombuena N, Aguilar M, Casas L, Molinuevo JL, et al. Spanish Multicenter Normative Studies (NEURONORMA Project): norms for Boston naming test and token test. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. (2009) 24:343-54. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acp039

105. Paradis M, Ardila A. Prueba de afasia para bilingües (American Spanish version. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum (1989).

106. Martín P, Manning L, Muñoz P, Montero I. Communicative abilities in daily living: Spanish standardization. Eval Psicol. (1990) 6:369-84.

107. Pineda DA, Rosselli M, Ardila A, Mejia SE, Romero MG, Perez C. The boston diagnostic aphasia examination-Spanish version: the influence of demographic variables. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. (2000) 6:802-14. doi: 10.1017/S135561770067707X

108. Boschi V, Catricalà E, Consonni M, Chesi C, Moro A, Cappa SF. Connected speech in neurodegenerative language disorders: a review. Front Psychol. (2017) 8:269. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00269

109. de la Fuente Garcia S, Ritchie CW, Luz S. Artificial intelligence, speech, language processing approaches to monitoring Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. (2020) 78:1547-74. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200888

110. Zimmerer VC, Hardy CJD, Eastman J, Dutta S, Varnet L, Bond RL, et al. Automated profiling of spontaneous speech in primary progressive aphasia and behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia: an approach based on usage-frequency. Cortex J Devoted Study Nerv Syst Behav. (2020) 133:103-19. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2020.08.027

Keywords: behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, language, Latin America, cognitive markers, dimensional approach

Citation: Geraudie A, Díaz Rivera M, Montembeault M and García AM (2021) Language in Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia: Another Stone to Be Turned in Latin America. Front. Neurol. 12:702770. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.702770

Received: 29 April 2021; Accepted: 12 July 2021;

Published: 10 August 2021.

Edited by:

Hernando Santamaría-García, Pontifical Javeriana University, ColombiaReviewed by:

Mattia Siciliano, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, ItalyCopyright © 2021 Geraudie, Díaz Rivera, Montembeault and García. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adolfo M. García, YWRvbGZvbWFydGluZ2FyY2lhQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.