95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Neurol. , 24 June 2021

Sec. Neurogenetics

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.694764

This article is part of the Research Topic Genotype-Phenotype Correlation in Parkinsonian Conditions View all 15 articles

Elisa Menozzi

Elisa Menozzi Anthony H. V. Schapira*

Anthony H. V. Schapira*Variants in the glucocerebrosidase (GBA) gene are the most common genetic risk factor for Parkinson disease (PD). These include pathogenic variants causing Gaucher disease (GD) (divided into “severe,” “mild,” or “complex”—resulting from recombinant alleles—based on the phenotypic effects in GD) and “risk” variants, which are not associated with GD but nevertheless confer increased risk of PD. As a group, GBA-PD patients have more severe motor and nonmotor symptoms, faster disease progression, and reduced survival compared with noncarriers. However, different GBA variants impact variably on clinical phenotype. In the heterozygous state, “complex” and “severe” variants are associated with a more aggressive and rapidly progressive disease. Conversely, “mild” and “risk” variants portend a more benign course. Homozygous or compound heterozygous carriers usually display severe phenotypes, akin to heterozygous “complex” or “severe” variants carriers. This article reviews genotype–phenotype correlations in GBA-PD, focusing on clinical and nonclinical aspects (neuroimaging and biochemical markers), and explores other disease modifiers that deserve consideration in the characterization of these patients.

Biallelic pathogenic variants in the glucocerebrosidase (GBA) gene (OMIM 606463) leading to deficient activity of the lysosomal enzyme gene product GCase (EC 3.2.1.45) cause the recessively inherited multisystem disorder Gaucher disease (GD) (1). The standard classification of GBA variants is based on their phenotypic effect in GD, with “complex” rearrangements and “severe” variants causing neuronopathic GD, and “mild” variants causing non-neuronopathic GD (2). Patients with non-neuronopathic GD but especially heterozygous carriers of pathogenic GBA variants have an increased risk of developing Parkinson disease (PD) (3). Increased risk for PD has also been associated with a number of variants (p.E326K, p.T369M) not clearly pathogenic for GD (4, 5). In parallel with this increasing genotypic heterogeneity, detailed assessments of several cohorts of GBA-PD have suggested phenotypic differences associated with distinct genotypes.

Herein, we examine the clinical syndrome of GBA-PD compared to GBA-negative (noncarriers) PD and critically discuss genotype–phenotype correlation within the GBA-PD population from both clinical and biomarker perspectives. Finally, we present other potential disease modifiers that may impact on clinical phenotypes of GBA-PD.

We performed a literature search for English-written publications on PD patients with GBA mutations using the National Center for Biotechnology Information's PubMed database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) using the following search terms: “parkinson” AND “GBA OR 1q22” in the title and “gene OR genetic OR mutation OR mutated.” We selected the articles relevant to our review and included additional articles from their reference lists. GBA variants were defined as follows:

- “mild” and “severe” variants are determined as per the GD classification of variant severity

- “risk variants” are those that increase PD risk but are not pathogenic for GD

- “complex” variants result from conversions, fusions, and insertions of parts of the pseudogene GBAP1 into GBA.

The frequency of GBA carriers is population-specific and ranges from 10% to 31% in Ashkenazi Jewish (AJ) to 3% to 12% in non-AJ North American (with European background) populations (6). As an example of ethnic heterogeneity of GBA variants, the p.N370S variant is very common in AJ populations with European origin and non-AJ European/West Asian populations, whereas it is not generally detected in East Asian populations (7–9). The penetrance of GBA variants in PD is low, age-specific, and controversial across studies, with an estimated 9.1% of carriers developing PD over their lifetime (10). At age 60 and 80 years, PD risks of ~5 and 9%−12% respectively are reported among GD patients, which is significantly greater than those of noncarriers (0.7 and 2.1%, respectively) but similar to the 1.5–14% and 8–19% respective prevalence among GBA heterozygote carriers (11–15), suggesting that PD risk is not further increased by carrying a second GBA mutant allele (11). Among familial PD cohorts, much higher penetrance is reported (13.7% at 60 years and 29.7% at 80 years) (16), though this is likely a contribution from other genetic factors in these cohorts. When considering the impact of different variants on penetrance, the odds ratio (OR) of developing PD was found to be much higher in people carrying severe rather than mild variants (10.3–13.6 vs. 2.2) (17, 18). However, no such differences in penetrance were reported between mild and severe variants in familial PD cases (16), again suggesting the influence of additional genetic factors in such cohorts. The most frequent risk variant associated with GBA-PD, p.E326K, has been associated with a PD OR of 1.60–2 in European PD populations and up to 5.5 in AJ patients (19–21), suggesting a similar if not higher risk compared with mild variants.

Compared with noncarriers, GBA-PD patients usually present symptoms earlier on (6, 22–26). PD patients with biallelic GBA variants (either homozygous or compound heterozygous), hereafter referred to as GD-PD, also have an earlier age at onset compared with heterozygous carriers (11, 27), indicating a possible “dose” effect of GBA influencing age at onset. When GBA variants were stratified, the majority of studies consistently reported earlier age at onset in severe variant carriers compared with mild or risk (17, 22, 28) and in patients with null or complex alleles relative to those with missense mutations (29). Rarely, no differences in age at onset were found (30, 31).

In terms of disease progression, carriers of any GBA variant reach progression milestones earlier compared with noncarriers (23, 32). In one study evaluating the impact of different variants on survival, severe and mild variants (considered together) were associated with a 2-fold greater risk of death with mean time to mortality approximately 1 year earlier compared with noncarriers, whereas risk variants showed similar mortality rates and time to mortality compared with noncarriers (32). In another longitudinal study conducted on PD patients of AJ ancestry, though, no significant effect of either mild or severe variants on survival was found (33). When survival of patients with mild and severe variants was directly compared, no differences were reported; nevertheless, only severe variants were associated with a greater risk of death relative to noncarriers (34). Overall, these results could suggest that only severe mutations might confer poor survival rates.

Compared with noncarriers, the usual presentation of GBA-PD is that of an akinetic-rigid syndrome, with early development of motor fluctuations and dyskinesia (22, 29, 35). Stratifying by GBA variants, severe variants have been associated with more severe and rapidly progressive motor phenotype, and shorter time to development of axial symptoms such as postural instability, as opposed to mild or risk variants (22, 32). At the other end of the spectrum, risk variants are more likely to associate with benign phenotypes and occurrence of motor fluctuations later in the disease course (22).

People with GBA-PD suffer from a higher burden of nonmotor symptoms both in the prodromal phase and during manifest disease. One study reported higher scores of the nonmotor symptoms scale in GBA-PD patients compared with noncarrier PD patients (12). Similar results were confirmed by another study showing that PD patients with severe variants or GD-PD patients had higher nonmotor symptoms questionnaire scores compared with PD patients carrying mild variants or noncarriers (31).

Among the nonmotor features associated with PD, hyposmia, constipation, and REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) are the most important prodromal risk factors for PD, and hereafter, we will discuss them individually. Olfactory function has been consistently shown to be worse and deteriorate over time in asymptomatic GBA carriers and GD patients compared with noncarriers (36–38). Interestingly, one study reported that more severe hyposmia at baseline could predict the development of parkinsonism in these individuals (39). Poorer hyposmia has also been reported in PD patients carrying pathogenic (severe/mild) variants vs. noncarriers (40), as well as in asymptomatic carriers of severe vs. mild variants (31). Moreover, GD-PD patients showed more severe loss of olfaction compared with GBA heterozygous and noncarrier PD patients (27), suggesting that possibly not only type but also “dose” of GBA variants may affect olfactory function. Regarding constipation, only few reports have investigated its occurrence separately from other autonomic features in GBA-PD, finding that constipation may present more frequently relative to noncarriers (41, 42). Data regarding RBD are controversial. On the one hand, RBD has been reported to occur more frequently in GBA-PD and GD-PD compared with noncarrier PD patients (28, 42) and in PD patients carrying severe variants compared with patients carrying mild variants (31). On the other hand, no differences were reported in cohorts of GBA carriers or GD patients in comparison to noncarrier healthy controls (36). In a longitudinal evaluation study, GBA carriers and GD patients showed a worsening of RBD symptoms over time (39); however, whether a deterioration of RBD symptoms in these subjects leads to the development of PD is not known.

After the diagnosis of PD, GBA-PD patients show an increased risk of cognitive decline (22, 23, 25, 26, 41, 43, 44), including those receiving deep brain stimulation surgery (45, 46). Specific cognitive domains seem to be more affected, particularly in visual short-term memory (47). When stratified by variant, in one study, PD carriers of severe or biallelic variants showed worse cognitive function compared with noncarriers, whereas mild or risk variants did not (30). However, other studies found that risk variants (p.E326K) were associated with similar cognitive deterioration (26, 48), or faster progression to dementia compared with pathogenic GBA variants (49, 50), as opposed to what is expected on the basis of the impact on GCase activity.

Increased frequency of psychiatric symptoms, such as hallucinations, delusions, and impulsive–compulsive behavior (ICB), has also been reported in GBA-PD patients vs. noncarriers (22, 41, 44, 51). The risk of psychiatric disturbances seems to be genotype specific. Severe or complex variant carriers were more affected than mild variant carriers (22, 31), and risk variant carriers showed the mildest phenotype (22).

Regarding autonomic function, this has been reported to be more affected in GBA-PD (22, 41, 42, 44), but no association of type or “dose” of GBA variants with autonomic phenotypes has been reported to date (22, 27).

In summary, within GBA-PD patients, motor symptoms, psychiatric disturbances, and possibly hyposmia are more severe and might show genotype–phenotype correlations. The genotype–phenotype association for cognitive and autonomic function is less clear, although these features are clearly more severely affected. Whether constipation and RBD are overrepresented features in GBA-PD or asymptomatic GBA carriers, and a genotype–phenotype correlation exists for these symptoms, has not yet been elucidated. The more rapid decline in motor and nonmotor features in GBA-PD and the influence of specific GBA variants in these patients should be considered in the context of personalized treatment strategies. For instance, clinicians should be particularly cautious in the use of medications increasing the risk of falls, or worsening autonomic function in GBA-PD patients, and should recommend to these patients to start physiotherapy and cognitive engagement strategies early in the disease course (52).

The degree of dopaminergic dysfunction in GBA-PD has been evaluated in few studies. Cilia et al. (34) showed that compared with noncarriers, PD patients carrying a severe (but not mild) variant had a significant dopamine transporter (DAT) deficit. When mild and severe variant carriers were directly compared, individuals with severe variants showed more pronounced deficit, mainly in the striatum contralateral to the most affected side (34). One study evaluating a small cohort of PD patients carrying risk variants (p.E326K and p.T369M) vs. noncarriers reported a reduced [18F]FDopa uptake in the bilateral caudate nuclei, anteromedial putamen ipsilateral, and nucleus accumbens contralateral to the most affected site in carriers (53), but no comparison was made with patients carrying other variants. Surprisingly, in a cohort of early PD patients mostly carrying mild GBA variants (89% p.N370S), patients showed higher specific binding ratio (SBR) in the contralateral caudate and putamen when compared with noncarriers (54), and higher SBR values in caudate, putamen, and striatum were also reported in non-manifesting p.N370S carriers relative to healthy controls (55). The proposed mechanisms underlying this observation might be either of a compensatory upregulation of tracer uptake in the early stage of the disease (associated with slower decline rate in DAT signal) or the result of disruption of dopamine release prior to dopaminergic terminal loss (54, 55). Longitudinal assessments evaluating DAT deficit progression in GBA carriers bearing different variants will elucidate the implicated mechanisms.

Metabolic networks have been investigated in GBA-PD patients using [18F]-FDG PET, suggesting greater disease activity compared with noncarriers, as shown by increased PD-related pattern (PDRP) and a trend toward increased PD-related cognitive pattern (PDCP) levels (56). Recently, Greuel et al. (53) reported a similar pattern in a small cohort of PD patients carrying risk variants (p.E326K and p.T369M), with both higher PDRP and PDCP levels and significant [18F]-FDG PET hypoactivity in the parietal lobe. These findings reflect the higher cognitive burden seen in GBA-PD and suggest that even risk variants such as p.E326K and p.T369M might be associated with a severe cognitive decline.

In a cross-sectional study using transcranial sonography, both asymptomatic GBA heterozygous carriers and GD patients showed an enlarged hyperechogenic area of the substantia nigra compared with healthy controls, but longitudinal studies are needed to determine the predictive value of these findings (57). In manifest PD, transcranial sonography could not discriminate between GBA-PD and noncarriers, although a higher percentage of GBA-PD patients showed interrupted brain stem raphe, a marker of serotonergic system impairment (41).

Segmentation of cortical and subcortical structures can provide information about regional atrophy. By comparing GBA-PD and GBA asymptomatic carriers vs. noncarrier PD and healthy controls, lower structural volumes and widespread cortical thinning were found among patients with PD compared with asymptomatic participants, but none of these differences were related to the genetic status (58). Given the more severe clinical profile associated with GBA-PD, one would have expected a more diffuse impairment in these individuals and possibly even in the asymptomatic carriers. Therefore, the applicability of this tool remains uncertain.

Total α-synuclein has been evaluated in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of GBA-PD patients, showing lower levels compared with noncarriers (59). After genotypic stratification, severe variants displayed the lowest levels, and mild variants had lower levels compared with risk variants, suggesting a genotype–phenotype association (28). Interestingly, a similar correlation between genotype and CSF α-synuclein has been found in cohorts of patients with Lewy body dementia carrying GBA variants (60).

Plasma oligomeric α-synuclein levels are considered one of the major factors in neurodegeneration in PD (61). GBA-PD patients showed increased levels compared with noncarriers, with a trend toward higher levels in those carrying severe/mild variants followed by risk variants (62). The possible association of plasma oligomeric α-synuclein and severity of GBA variants reinforces the hypothesis that decreased GCase enzymatic activity plays a central role in PD pathogenesis.

The presence of phospho-α-synuclein pathology in skin biopsies has been evaluated in one study of 10 GBA-PD patients (six p.N370S, three p.E326K, one p.L444P). Six out of 10 demonstrated phospho-α-synuclein deposition, mainly in autonomic but also somatosensory fibers (63). These findings resemble what is seen in PD noncarriers, suggesting that skin biopsies might be used to investigate α-synuclein pathology in vivo, but they might not be useful to discriminate among different GBA genotypes.

Enzymatic activity of GCase seems to be a promising biomarker in GBA-PD, showing a genotype–phenotype association. Lower GCase enzymatic activity measured in dried blood spots has been reported in GBA-PD patients compared with noncarriers (64), and after genotypic stratification for GBA variants, increasing severity was associated with decreasing residual GCase activity (22, 62, 65) and longitudinally with a steeper decline of enzymatic activity (65). When measured in CSF, GCase activity was again significantly reduced in GBA-PD (66). Investigating how single GBA variants affect CSF GCase levels and whether they correlate with levels measured in dried blood spots might be of particular interest.

Lipid dysregulation has been proposed as one of the pathogenic mechanisms underlying GBA-PD (67). Elevation of different lipids, such as ceramide, total monohexosylceramide (glucosylceramide + galactosylceramide), sphingomyelin, and sphingosine (glucosylsphingosine + galactosylsphingosine), has been reported in GBA-PD vs. noncarriers (68). Galactosylsphingosine and glucosylsphingosine tended to be higher in patients carrying severe/mild variants compared with risk variants (69); however, their elevation was not correlated with either GCase activity measured in dried blood spots or plasma α-synuclein levels (69), arguing against a causal relationship between GCase deficiency and substrate accumulation.

To date, one study has evaluated the metabolomic profile of GBA-PD patients using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Using untargeted approach, elevated levels of several amino acids including asparagine, ornithine, glutamine, glycine, and polyol pathway metabolites were found in plasma of GBA-PD patients carrying risk variants compared with noncarriers (53). Interestingly, the two groups were substantially identical in terms of clinical features, suggesting that assessing the metabolomic profile might be a good biomarker to differentiate patients in early stages.

Biomarkers of systemic inflammation have been investigated in few studies in GBA-PD, with contrasting results. In one study, higher levels of interleukin-8 differentiated GBA-PD from noncarriers and were associated with poorer cognitive function (43). The same study also reported elevation of other cytokines, such as monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and macrophage inflammatory protein-1α in GBA-PD, whereas another study reported reduced levels of MCP-1 (70). The discrepancy between these results might be due to small sample sizes, different methodologies, and perhaps lack of stratification by variant type.

Overall, multiple biomarkers have been proposed so far in GBA-PD. Dopaminergic imaging and metabolic imaging seem promising candidates to elucidate possible genotype–phenotype correlations. Reduced total CSF α-synuclein, increased plasma oligomeric α-synuclein, and reduced GCase activity have shown genotype–phenotype associations that would require further confirmation in future studies. Whether lipidic and metabolic profiles are influenced by genotype remains elusive. Furthermore, the application of validated biomarkers to the prodrome and progression of PD in general remains a controversial area (71).

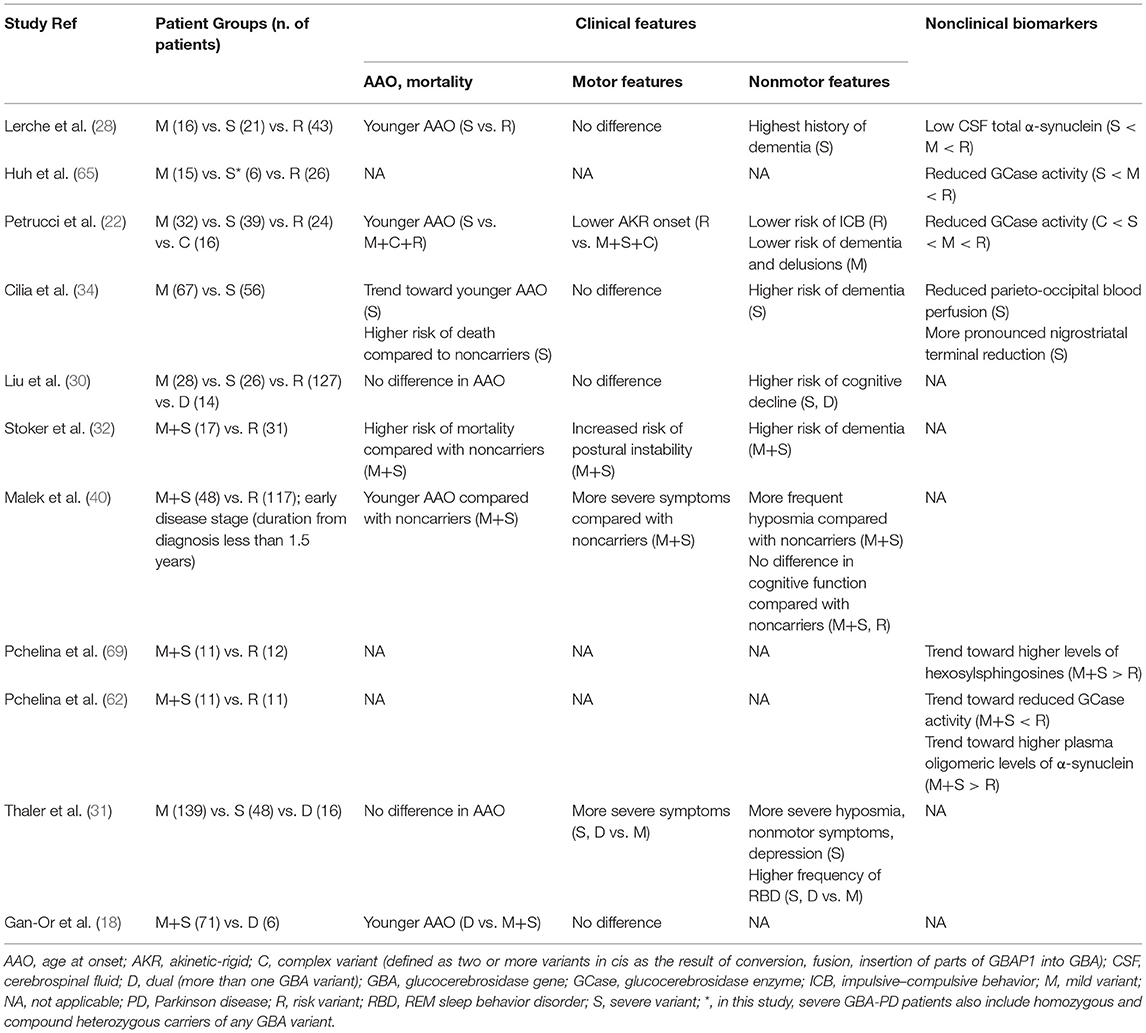

The most important clinical and nonclinical data about genotype–phenotype correlations in GBA-PD are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of main studies reporting genotype–phenotype correlations in GBA-Parkinson Disease.

Aside from direct genotype–phenotype correlations within GBA-PD, several other genetic and environmental factors may influence both disease penetrance and clinical features. These are important to consider and control for when evaluating GBA-PD cohorts to avoid erroneous causal attribution of observed symptoms to GBA genotype alone.

Among genetic factors, common single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the GBA locus have been proposed as potential modifiers of GBA-PD age at onset and motor progression (72, 73). Beyond GBA, the Alzheimer disease Bridging Integrator 1 (BIN1) locus (OMIM 601248), which is involved in synaptic vesicle endocytosis in the central nervous system, has also been proposed as a modifier of age at onset in GBA-PD, with the rs13403026 SNP being associated with older age at onset in both mild and severe GBA carriers (74). Another candidate is the Metaxin 1 (MTX1) gene (OMIM 600605), which is located close to GBA and encodes a mitochondrial protein. Homozygous c.184A/A genotype in the MTX1 gene is associated with earlier age at onset in GBA-PD (75). Using a genome-wide association study, specific variants in close proximity to α-synuclein (SNCA; OMIM 163890) and cathepsin B (CTSB; OMIM 116810) genes (rs356219 and rs1293298) were found to associate with earlier age at onset in GBA carriers (76). Interestingly, the G/G SNCA rs356219 genotype was also associated with a more aggressive phenotype in a small cohort of GBA-PD patients (77). These findings suggest a possible synergistic effect of GBA and SNCA variants and deserve further evaluation in stratified groups of GBA carriers.

Although the mechanisms by which GCase influences PD pathogenesis are still debated (78), any factor influencing lysosomal GCase activity might potentially be disease modifying. For instance, it has been demonstrated that α-synuclein itself can induce aberrant maturation and endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi apparatus trafficking of GCase and therefore reduce the mature form of GCase and its lysosomal activity (79). More recently, it has been suggested that mutant leucine-rich repeat kinase (LRRK2; OMIM 609007) products may act as a negative regulator of GCase activity. GCase activity was shown to be reduced in human dopaminergic neurons carrying different LRRK2 mutations, and the treatment of dopaminergic neurons from patients with either LRRK2 or GBA variants with LRRK2 kinase inhibitor could increase GCase activity and rescue neurons from PD-related damage (80).

Among non-genetic risk factors, a recent study conducted on a large cohort of asymptomatic GBA carriers has evaluated the role of metabolic syndrome, a well-known risk factor for PD (81), as a possible disease determinant. The authors did not find any association between metabolic syndrome and risk of PD; however, hypertriglyceridemia and prediabetes were possibly overrepresented in those destined to later develop PD, regardless of GBA genotypes (82). In one study evaluating multiple environmental factors linked to PD, a more frequent exposure to pesticides was reported in GBA-PD patients vs. noncarriers, whereas no difference in smoking or coffee drinking was found (83). These preliminary data need further validation but may suggest that certain components of metabolic syndrome such as insulin resistance, or previous exposure to pesticides, should be carefully considered as potential disease determinants in GBA carriers.

Increasing numbers of GBA variants have been associated with an elevated risk of PD, but the standard classification of GBA variants incompletely reflects the complex and rapidly evolving genetic landscape of GBA-PD. Moreover, data from cohorts of GBA-PD patients suggest that carriers of different variants display specific clinical profiles, with complex or severe variants associated with a more aggressive and rapidly progressive PD phenotype and mild or risk variants with a more benign phenotype.

Stratifying GBA carriers in both the prodromal and manifest phase of PD is of paramount importance, first, to address questions about prognosis, advanced treatment response, and counseling and, second, to recognize early the presence of subclinical/clinical symptoms that might help more precise selection of individuals for clinical trials. Multimodal evaluations including metabolic imaging and assessment of GCase activity, α-synuclein levels, and lipid and metabolic profile may shed light on inter-genotype differences, discover new biomarkers for clinical and research setting, and unveil novel mechanisms underlying GBA-PD pathogenesis.

EM conceived the manuscript and wrote the first draft. AS conceived and reviewed the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

AS has received funding from the MRC (UK), Parkinson UK, the Cure Parkinson Trust, and the Royal Free London Hospital Charity. He is an employee of UCL. He has served as a consultant for Prevail Therapeutics, Sanofi, and Kyowa. He is supported by the NIHR UCLH BRC.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Stirnemann JN, Belmatoug F, Camou C, Serratrice R, Froissart C„ Caillaud T, et al. A Review of gaucher disease pathophysiology, clinical presentation and treatments. Int J Mol Sci. (2017) 18:441. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020441

2. Beutler E, Gelbart T, Scott CR. Hematologically important mutations: Gaucher disease. Blood Cells Mol Dis. (2005) 35:355–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2005.07.005

3. Sidransky E, Nalls MA, Aasly JO, Aharon-Peretz J, Annesi G, Barbosa ER, et al. Multicenter analysis of glucocerebrosidase mutations in Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. (2009) 361:1651–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901281

4. Duran R, Mencacci NE, Angeli AV, Shoai M, Deas E, Houlden H, et al. The glucocerobrosidase E326K variant predisposes to Parkinson's disease, but does not cause Gaucher's disease. Mov Disord. (2013) 28:232–6. doi: 10.1002/mds.25248

5. Mallett V, Ross JP, Alcalay RN, Ambalavanan A, Sidransky E, Dion PA, et al. GBA p.T369M substitution in Parkinson disease: POLYMORPHISM or association? A meta-analysis. Neurol Genet. (2016) 2:e104. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000104

6. Neumann J, Bras J, Deas E, O'Sullivan SS, Parkkinen L, Lachmann RH, et al. Glucocerebrosidase mutations in clinical and pathologically proven Parkinson's disease. Brain. (2009) 132(Pt 7):1783–94. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp044

7. Hruska KS, LaMarca ME, Scott CR, Sidransky E. Gaucher disease: mutation and polymorphism spectrum in the glucocerebrosidase gene (GBA). Hum Mutat. (2008) 29:567–83. doi: 10.1002/humu.20676

8. Pulkes T, Choubtum L, Chitphuk S, Thakkinstian A, Pongpakdee S, Kulkantrakorn K, et al. Glucocerebrosidase mutations in Thai patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. (2014) 20:986–91. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.06.007

9. Zhang Y, Shu L, Sun Q, Zhou X, Pan H, Guo J, et al. Integrated genetic analysis of racial differences of common GBA variants in Parkinson's disease: a meta-analysis. Front Mol Neurosci. (2018) 11:43. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00043

10. Riboldi GM, Di Fonzo AB. GBA, Gaucher Disease, and Parkinson's Disease: from genetic to clinic to new therapeutic approaches. Cells. (2019) 8:364. doi: 10.3390/cells8040364

11. Alcalay RN, Dinur T, Quinn T, Sakanaka K, Levy O, Waters C, et al. Comparison of Parkinson risk in Ashkenazi Jewish patients with Gaucher disease and GBA heterozygotes. JAMA Neurol. (2014) 71:752–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.313

12. McNeill A, Duran R, Hughes DA, Mehta A, Schapira AH. A clinical and family history study of Parkinson's disease in heterozygous glucocerebrosidase mutation carriers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2012) 83:853–4. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-302402

13. Rana HQ, Balwani M, Bier L, Alcalay RN. Age-specific Parkinson disease risk in GBA mutation carriers: information for genetic counseling. Genet Med. (2013) 15:146–9. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.107

14. Rosenbloom B, Balwani M, Bronstein JM, Kolodny E, Sathe S, Gwosdow AR, et al. The incidence of Parkinsonism in patients with type 1 Gaucher disease: data from the ICGG Gaucher Registry. Blood Cells Mol Dis. (2011) 46:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2010.10.006

15. Balestrino R, Tunesi S, Tesei S, Lopiano L, Zecchinelli AL, Goldwurm S. Penetrance of glucocerebrosidase (GBA) mutations in Parkinson's disease: a kin cohort study. Mov Disord. (2020) 35: 2111–4. doi: 10.1002/mds.28200

16. Anheim M, Elbaz A, Lesage S, Durr A, Condroyer C, Viallet F, et al. Penetrance of Parkinson disease in glucocerebrosidase gene mutation carriers. Neurology. (2012) 78:417–20. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318245f476

17. Gan-Or Z, Amshalom I, Kilarski LL, Bar-Shira A, Gana-Weisz M, Mirelman A. Differential effects of severe vs mild GBA mutations on Parkinson disease. Neurology. (2015) 84:880–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001315

18. Gan-Or Z, Giladi N, Rozovski U, Shifrin C, Rosner S, Gurevich T. Genotype-phenotype correlations between GBA mutations and Parkinson disease risk and onset. Neurology. (2008) 70:2277–83. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304039.11891.29

19. Ran C, Brodin L, Forsgren L, Westerlund M, Ramezani M, Gellhaar S, et al. Strong association between glucocerebrosidase mutations and Parkinson's disease in Sweden. Neurobiol Aging. (2016) 45:212 e5–212 e11. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.04.022

20. Ruskey JA, Greenbaum L, Ronciere L, Alam A, Spiegelman D, Liong C, et al. Increased yield of full GBA sequencing in Ashkenazi Jews with Parkinson's disease. Eur J Med Genet. (2019) 62:65–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.05.005

21. Blauwendraat C, Bras JM, Nalls MA, Lewis PA, Hernandez DG, Singleton AB, et al. International Parkinson's disease genomics. Coding variation in GBA explains the majority of the SYT11-GBA Parkinson's disease GWAS locus. Mov Disord. (2018) 33:1821–1823. doi: 10.1002/mds.103

22. Petrucci S, Ginevrino M, Trezzi I, Monfrini E, Ricciardi L, Albanese A, et al. GBA-related Parkinson's disease: dissection of genotype-phenotype correlates in a large italian cohort. Mov Disord. (2020). 35:2106–11. doi: 10.1002/mds.28195

23. Brockmann K, Srulijes K, Pflederer S, Hauser AK, Schulte C, Maetzler W, et al. GBA-associated Parkinson's disease: reduced survival and more rapid progression in a prospective longitudinal study. Mov Disord. (2015) 30:407–11. doi: 10.1002/mds.26071

24. Nichols WC, Pankratz N, Marek DK, Pauciulo MW, Elsaesser VE, Halter CA, et al. Parkinson study group. mutations in GBA are associated with familial Parkinson disease susceptibility and age at onset. Neurology. (2009) 72:310–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327823.81237.d1

25. Zhang Y, Shu L, Zhou X, Pan H, Xu Q, Guo J, et al. A meta-analysis of GBA-related clinical symptoms in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsons Dis. (2018) 2018:3136415. doi: 10.1155/2018/3136415

26. Lunde KA, Chung J, Dalen I, Pedersen KF, Linder J, Domellof ME, et al. Maple-Grodem J. Association of glucocerebrosidase polymorphisms and mutations with dementia in incident Parkinson's disease. Alzheimers Dement. (2018) 14:1293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.04.006

27. Thaler A, Gurevich T, Bar Shira A, Gana Weisz M, Ash E, Shiner T, et al. A “dose” effect of mutations in the GBA gene on Parkinson's disease phenotype. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. (2017) 36:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.12.014

28. Lerche S, Wurster I, Roeben B, Zimmermann M, Riebenbauer B, Deuschle C, et al. Parkinson's disease: glucocerebrosidase 1 mutation severity is associated with CSF Alpha-synuclein profiles. Mov Disord. (2020) 35:495–499. doi: 10.1002/mds.27884

29. Lesage S, Anheim M, Condroyer C, Pollak P, Durif F, Dupuits C, et al. French Parkinson's disease genetics study, large-scale screening of the Gaucher's disease-related glucocerebrosidase gene in Europeans with Parkinson's disease. Hum Mol Genet. (2011) 20:202–10. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq454

30. Liu G, Boot B, Locascio JJ, Jansen IE, Winder-Rhodes S, Eberly S, et al. International genetics of Parkinson disease progression. specifically neuropathic Gaucher's mutations accelerate cognitive decline in Parkinson's. Ann Neurol. (2016) 80:674–85. doi: 10.1002/ana.24781

31. Thaler A, Bregman N, Gurevich T, Shiner T, Dror Y, Zmira O, et al. Parkinson's disease phenotype is influenced by the severity of the mutations in the GBA gene. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. (2018) 55:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.05.009

32. Stoker TB, Camacho M, Winder-Rhodes S, Liu G, Scherzer CR, Foltynie T, et al. Impact of GBA1 variants on long-term clinical progression and mortality in incident Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2020) 91:695–702. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-322857

33. Thaler A, Kozlovski T, Gurevich T, Bar-Shira A, Gana-Weisz M, Orr-Urtreger A, et al. Survival rates among Parkinson's disease patients who carry mutations in the LRRK2 and GBA genes. Mov Disord. (2018) 33:1656–60. doi: 10.1002/mds.27490

34. Cilia R, Tunesi S, Marotta G, Cereda E, Siri C, Tesei S, et al. Survival and dementia in GBA-associated Parkinson's disease: the mutation matters. Ann Neurol. (2016) 80:662–73. doi: 10.1002/ana.24777

35. Olszewska DA, McCarthy A, Soto-Beasley AI, Walton RL, Magennis B, McLaughlin RL, et al. Association between glucocerebrosidase mutations and Parkinson's disease in Ireland. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:527. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00527

36. McNeill A, Duran R, Proukakis C, Bras J, Hughes D, Mehta A, et al. Hyposmia and cognitive impairment in Gaucher disease patients and carriers. Mov Disord. (2012) 27:526–32. doi: 10.1002/mds.24945

37. Mullin S, Beavan M, Bestwick J, McNeill A, Proukakis C, Cox T, et al. Evolution and clustering of prodromal parkinsonian features in GBA1 carriers. Mov Disord. (2019) 34:1365–1373. doi: 10.1002/mds.27775

38. Beavan M, McNeill A, Proukakis C, Hughes DA, Mehta A, Schapira AH. Evolution of prodromal clinical markers of Parkinson disease in a GBA mutation-positive cohort. JAMA Neurol. (2015) 72:201–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.2950

39. Avenali M, Toffoli M, Mullin S, McNeil A, Hughes DA, Mehta A, et al. Evolution of prodromal parkinsonian features in a cohort of GBA mutation-positive individuals: a 6-year longitudinal study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2019) 90:1091–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2019-320394

40. Malek N, Weil RS, Bresner C, Lawton MA, Grosset KA, Tan M, et al. Features of GBA-associated Parkinson's disease at presentation in the UK Tracking Parkinson's study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2018) 89:702–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317348

41. Brockmann K, Srulijes K, Hauser AK, Schulte C, Csoti I, Gasser T, et al. GBA-associated PD presents with nonmotor characteristics. Neurology. (2011) 77:276–80. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318225ab77

42. Jesus S, Huertas I, Bernal-Bernal I, Bonilla-Toribio M, Caceres-Redondo MT, et al. GBA Variants Influence Motor and Non-Motor Features of Parkinson's Disease. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0167749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167749

43. Chahine LM, Qiang J, Ashbridge E, Minger J, Yearout D, Horn S, et al. Chen-Plotkin Clinical A, and biochemical differences in patients having Parkinson disease with vs without GBA mutations. JAMA Neurol. (2013) 70:852–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.1274

44. Wang C, Cai Y, Gu Z, Ma J, Zheng Z, Tang BS, et al. Chinese Parkinson Study. Clinical profiles of Parkinson's disease associated with common leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 and glucocerebrosidase genetic variants in Chinese individuals. Neurobiol Aging. (2014) 35:725 e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.08.012

45. Lythe V, Athauda D, Foley J, Mencacci NE, Jahanshahi M, Cipolotti L, et al. GBA-Associated Parkinson's Disease: Progression in a Deep Brain Stimulation Cohort. J Parkinsons Dis. (2017) 7:635–44. doi: 10.3233/JPD-171172

46. Mangone G, Bekadar S, Cormier-Dequaire F, Tahiri K, Welaratne A, Czernecki V, et al. Early cognitive decline after bilateral subthalamic deep brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease patients with GBA mutations. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. (2020) 76:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.04.002

47. Zokaei N, McNeill A, Proukakis C, Beavan M, Jarman P, Korlipara P, et al. Visual short-term memory deficits associated with GBA mutation and Parkinson's disease. Brain. (2014) 137(Pt 8):2303–11. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu143

48. Mata IF, Leverenz JB, Weintraub D, Trojanowski JQ, Chen-Plotkin A, Van Deerlin VM, et al. GBA Variants are associated with a distinct pattern of cognitive deficits in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. (2016) 31:95–102. doi: 10.1002/mds.26359

49. Davis MY, Johnson CO, Leverenz JB, Weintraub D, Trojanowski JQ, Chen-Plotkin A, et al. Association of GBA mutations and the E326K polymorphism with motor and cognitive progression in Parkinson Disease. JAMA Neurol. (2016) 73:1217–1224. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.2245

50. Straniero L, Asselta R, Bonvegna S, Rimoldi V, Melistaccio G, Solda G, et al. The SPID-GBA study: sex distribution. penetrance, incidence, and dementia in GBA-PD. Neurol Genet. (2020). 6:e523. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000523

51. Barrett MJ, Shanker VL, Severt WL, Raymond D, Gross SJ, Schreiber-Agus N, et al. Cognitive and Antipsychotic Medication Use in Monoallelic GBA-Related Parkinson Disease. JIMD Rep. (2014) 16:31–8. doi: 10.1007/8904_2014_315

52. Giladi N, Mirelman A, Thaler A, Orr-Urtreger A. A personalized approach to Parkinson's disease patients based on founder mutation analysis. Front Neurol. (2016) 7:71. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00071

53. Greuel A, Trezzi JP, Glaab E, Ruppert MC, Maier F, Jager C, et al. GBA variants in Parkinson's disease: clinical, metabolomic, and multimodal neuroimaging phenotypes. Mov Disord. (2020). 35:2201–10. doi: 10.1002/mds.28225

54. Simuni T, Brumm MC, Uribe L, Caspell-Garcia C, Coffey CS, Siderowf A, et al. Clinical and dopamine transporter imaging characteristics of leucine rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) and glucosylceramidase beta (GBA) Parkinson's disease participants in the Parkinson's progression markers initiative: a cross-sectional study. Mov Disord. (2020) 35:833–844. doi: 10.1002/mds.27989

55. Simuni T, Uribe L, Cho HR, Caspell-Garcia C, Coffey CS, Siderowf A, et al. Clinical and dopamine transporter imaging characteristics of non-manifest LRRK2 and GBA mutation carriers in the Parkinson's Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI): a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. (2020) 19:71–80. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30319-9

56. Schindlbeck KA, Vo A, Nguyen N, Tang CC, Niethammer M, Dhawan V, et al. LRRK2 and GBA Variants Exert Distinct Influences on Parkinson's Disease-Specific Metabolic Networks. Cereb Cortex. (2020) 30:2867–78. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhz280

57. Arkadir D, Dinur T, Becker Cohen M, Revel-Vilk S, Tiomkin M, et al. Prodromal substantia nigra sonography undermines suggested association between substrate accumulation and the risk for GBA-related Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol. (2019) 26:1013–1018. doi: 10.1111/ene.13927

58. Thaler A, Kliper E, Maidan I, Herman T, Rosenberg-Katz K, Bregman N, et al. Cerebral imaging markers of GBA and LRRK2 related Parkinson's disease and their first-degree unaffected relatives. Brain Topogr. (2018) 31:1029–36. doi: 10.1007/s10548-018-0653-8

59. Lerche S, Schulte C, Srulijes K, Pilotto A, Rattay TW, Hauser AK, et al. Cognitive impairment in Glucocerebrosidase (GBA)-associated PD: not primarily associated with cerebrospinal fluid Abeta and Tau profiles. Mov Disord. (2017) 32:1780–1783. doi: 10.1002/mds.27199

60. Lerche S, Machetanz G, Wurster I, Roeben B, Zimmermann M, Pilotto A, et al. Dementia with lewy bodies: GBA1 mutations are associated with cerebrospinal fluid alpha-synuclein profile. Mov Disord. (2019) 34:1069–1073. doi: 10.1002/mds.27731

61. Kalia LV, Kalia SK, McLean PJ, Lozano AM, Lang AE. alpha-Synuclein oligomers and clinical implications for Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. (2013) 73:155–69. doi: 10.1002/ana.23746

62. Pchelina S, Emelyanov A, Baydakova G, Andoskin P, Senkevich K, Nikolaev M, et al. Oligomeric alpha-synuclein and glucocerebrosidase activity levels in GBA-associated Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett. (2017) 636:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.10.039

63. Doppler K, Brockmann K, Sedghi A, Wurster I, Volkmann J, Oertel WH, et al. Dermal phospho-alpha-synuclein deposition in patients with Parkinson's disease and mutation of the glucocerebrosidase gene. Front Neurol. (2018) 9:1094. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.01094

64. Alcalay RN, Levy OA, Waters CC, Fahn S, Ford B, Kuo SH, et al. Glucocerebrosidase activity in Parkinson's disease with and without GBA mutations. Brain. (2015) 138(Pt 9):2648–58. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv179

65. Huh YE, Chiang MSR, Locascio JJ, Liao Z, Liu G, Choudhury K, et al. beta-Glucocerebrosidase activity in GBA-linked Parkinson disease: The type of mutation matters. Neurology. (2020) 95:e685–e696. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009989

66. Parnetti L, Paciotti S, Eusebi P, Dardis A, Zampieri S, Chiasserini D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid beta-glucocerebrosidase activity is reduced in parkinson's disease patients. Mov Disord. (2017) 32:1423–31. doi: 10.1002/mds.27136

67. Alecu I, Bennett SAL. Dysregulated lipid metabolism and its role in alpha-synucleinopathy in Parkinson's disease. Front Neurosci. (2019) 13:328. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00328

68. Guedes LC, Chan RB, Gomes MA, Conceicao VA, Machado RB, Soares T, et al. Miltenberger-Miltenyi G. Serum lipid alterations in GBA-associated Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. (2017) 44:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.08.026

69. Pchelina S, Baydakova G, Nikolaev M, Senkevich K, Emelyanov A, Kopytova A, et al. Blood lysosphingolipids accumulation in patients with Parkinson's disease with glucocerebrosidase 1 mutations. Mov Disord. (2018) 33:1325–30. doi: 10.1002/mds.27393

70. Miliukhina IV, Usenko TS, Senkevich KA, Nikolaev MA, Timofeeva AA, Agapova EA, et al. Plasma cytokines profile in patients with Parkinson's disease associated with mutations in GBA gene. Bull Exp Biol Med. (2020) 168:423–26. doi: 10.1007/s10517-020-04723-x

71. Vieira SRL, Toffoli M, Campbell P, Schapira AHV. Biofluid biomarkers in Parkinson's disease: clarity amid controversy. Mov Disord. (2020) 35:1128–33. doi: 10.1002/mds.28030

72. Schierding W, Farrow S, Fadason T, Graham OEE, Pitcher TL, Qubisi S, et al. Common variants coregulate expression of GBA and modifier genes to delay Parkinson's disease onset. Mov Disord. (2020) 35:1346–1356. doi: 10.1002/mds.28144

73. Davis AA, Andruska KM, Benitez BA, Racette BA, Perlmutter JS, Cruchaga C. Variants in GBA, SNCA, and MAPT influence Parkinson disease risk, age at onset, and progression. Neurobiol Aging. (2016) 37:209 e1–209 e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.09.014

74. Gan-Or Z, Amshalom I, Bar-Shira A, Gana-Weisz M, Mirelman A, Marder K, et al. The Alzheimer disease BIN1 locus as a modifier of GBA-associated Parkinson disease. J Neurol. (2015) 262:2443–7. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7868-3

75. Gan-Or Z, Bar-Shira A, Gurevich T, Giladi N, Orr-Urtreger A. Homozygosity for the MTX1 c.184T>A (p.S63T) alteration modifies the age of onset in GBA-associated Parkinson's disease. Neurogenetics. (2011) 12:325–32. doi: 10.1007/s10048-011-0293-6

76. Blauwendraat C, Reed X, Krohn L, Heilbron K, Bandres-Ciga S, Tan M, et al. Genetic modifiers of risk and age at onset in GBA associated Parkinson's disease and Lewy body dementia. Brain. (2020) 143:234–48. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz350

77. Stoker TB, Camacho M, Winder-Rhodes S, Liu G, Scherzer CR, Foltynie T, et al. A common polymorphism in SNCA is associated with accelerated motor decline in GBA-Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2020) 91:673–4. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2019-322210

78. Blandini F, Cilia R, Cerri S, Pezzoli G, Schapira AHV, Mullin S, et al. Glucocerebrosidase mutations and synucleinopathies: toward a model of precision medicine. Mov Disord. (2019) 34:9–21. doi: 10.1002/mds.27583

79. Mazzulli JR, Xu YH, Sun Y, Knight AL, McLean PJ, Caldwell GA, et al. Gaucher disease glucocerebrosidase and alpha-synuclein form a bidirectional pathogenic loop in synucleinopathies. Cell. (2011) 146:37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.001

80. Ysselstein D, Nguyen M, Young TJ, Severino A, Schwake M, Merchant K, et al. LRRK2 kinase activity regulates lysosomal glucocerebrosidase in neurons derived from Parkinson's disease patients. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:5570. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13413-w

81. Nam GE, Kim SM, Han K, Kim NH, Chung HS, Kim JW, et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of Parkinson disease: A nationwide cohort study. PLoS Med. (2018) 15:e1002640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002640

82. Thaler A, Shenhar-Tsarfaty S, Shaked Y, Gurevich T, Omer N, Bar-Shira A, et al. Metabolic syndrome does not influence the phenotype of LRRK2 and GBA related Parkinson's disease. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:9329. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66319-9

Keywords: Parkinson's, GBA, glucocerebrosidase, genotype-phenotype, biomarker

Citation: Menozzi E and Schapira AHV (2021) Exploring the Genotype–Phenotype Correlation in GBA-Parkinson Disease: Clinical Aspects, Biomarkers, and Potential Modifiers. Front. Neurol. 12:694764. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.694764

Received: 13 April 2021; Accepted: 18 May 2021;

Published: 24 June 2021.

Edited by:

Luca Marsili, University of Cincinnati, United StatesReviewed by:

Suzanne Lesage, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM), FranceCopyright © 2021 Menozzi and Schapira. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anthony H. V. Schapira, YS5zY2hhcGlyYUB1Y2wuYWMudWs=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.