94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Neurol. , 09 January 2019

Sec. Neurodegeneration

Volume 9 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.01169

Background: Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease with no effective treatment. Researchers have focused on exploring biomarkers for its early diagnosis, especially on finding a new gene target. Recent studies have shown that protein interacting with C-kinase-1(PICK1) is related to AD through regulating hippocampal synaptic plasticity. PICK1 gene polymorphisms have been identified in psychological and other related disorders.

Methods: This study included 133 sporadic AD patients and 173 healthy controls. All coding exons and intron-exon boundaries of the PICK1 gene were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which were subsequently sequenced and analyzed.

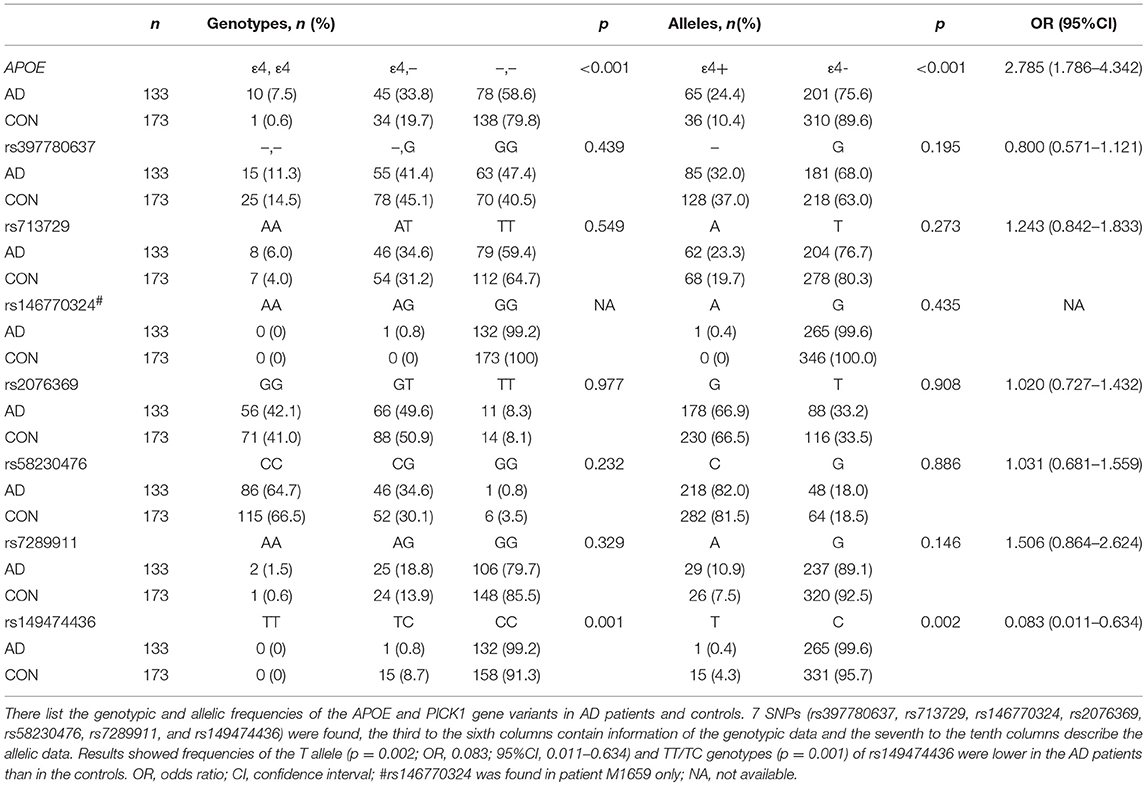

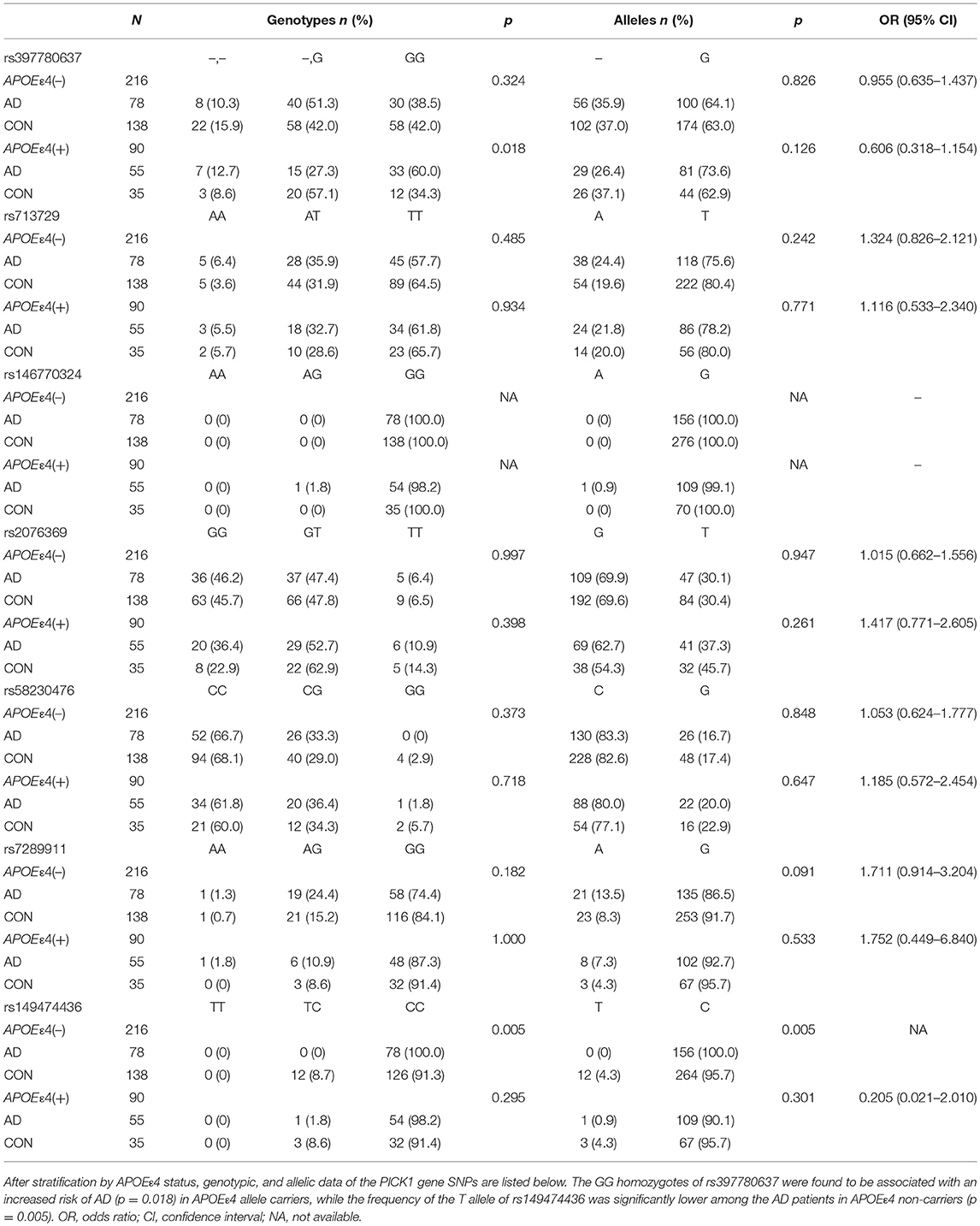

Results: This is the first genetic association study to investigate the association between PICK1 gene and AD risk in Chinese Han population. Seven single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were found in our research (rs397780637, rs713729, rs2076369, rs58230476, rs7289911, rs149474436; and rs146770324 for patient M1659 only). Frequencies of the T allele (p = 0.002; OR, 0.083; 95%CI, 0.011–0.634) and TT/TC genotypes (p = 0.001) of rs149474436 were lower in AD patients than in the controls. The GG homozygotes of rs397780637 were found to be associated with an increased risk of AD (p = 0.018) in APOEε4 allele carriers, while the frequency of the T allele of rs149474436 was significantly lower among AD patients in APOEε4 non-carriers (p = 0.005).

Conclusions: Our results suggest that PICK1 gene SNPs are associated with AD susceptibility in East Asian population, T allele of rs149474436 may play as a protective factor while the rs397780637 GG homozygotes may be associated with an increased risk of AD. Further studies should be considered in a larger cohort of patients with diverse demographics.

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder with irreversible memory decline and personality changes, which increases the burden of both the family and society. Pathogenic mechanisms of AD, especially its genetic susceptibilities are hot topics in this field. Recently, many rare variants have been identified as genetic markers of AD, such as APP (1), TREM2 (2), CD33, and MS4A (3, 4). However, the results from different clinical centers are controversial. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele is so far, the strongest genetic risk factor for AD.

Protein interacting with C-kinase-1 (PICK1) is a peripheral membrane protein containing PSD95/DIgA/ZO-1 (PDZ) domain and Bin/amphiphysin/Rvs (BAR) domain (5). It is expressed in various tissues, particularly abundant in the brain and testis (6). In the central nervous system (CNS), PICK1 interacts with numerous neurotransmitter receptors, transporters, and enzymes, regulating their trafficking (7). Based on the interaction of PICK1 with CNS dopamine transporter system, the gene of PICK1 has been implicated in schizophrenia and methamphetamine abusers, and positive results have been identified (8, 9). It has been shown that PICK1 also plays an important role in hippocampal synaptic plasticity, which makes it a potential target for the early diagnosis and treatment of AD. It regulates trafficking of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPAR) and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) plasticity during hippocampal long-term depression (LTD) and long-term potentiation (LTP) (10). Another important mechanism underlying the role of PICK1 in cognition is about D-serine, a co-agonist of NMDAR, playing an important role in regulating synaptic plasticity of neuronal cells (11). Following the interaction between PICK1 and serine racemase, an enzyme converting L-serine to D-serine, protein kinase C (PKC) can be directed to its targets in cells. PKC can also regulate the activity of serine racemase and the levels of D-serine in the brain, indicating the regulation of PICK1 in NMDAR mediates neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity (12, 13).

Senile plaques, consisting of amyloid beta (Aβ), and neurofibrillary tangles, consisting of hyperphosphorylated tau, are the two main pathological hallmarks of AD (14). In Alfonso's studies, they found that the PDZ domain of PICK1 was required for Aβ in weakening synapses. Mice lacking PICK1 failed to depress synaptic transmission or reduce surface AMPAR subunit2 (15). Glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), a well-known serine/threonine kinase, phosphorylates various substrates including tau. It can also phosphorylate PICK1 during LTD induction. Furthermore, in tau knock-out mice, there was a loss of LTD, which inferred that PICK1 might regulate tau hyper-phosphorylation through GSK-3β during LTD in AD (15, 16). Therefore, it is of particular interest to investigate the association between the PICK1 gene and the risk of AD.

The present study is a case-control study to investigate the association between PICK1 gene polymorphisms and the risk of developing AD. We found that SNPs at the PICK1 gene may modulate the risk of AD.

Subjects included in this case-control study were consisted of 133 sporadic AD patients (age 70.32 ± 9.63) and 173 controls (age 68.98 ± 9.42). The AD patients were enrolled from the Department of Neurology, Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, School of Medicine. A clinical diagnosis of AD was established according to the criteria of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (17, 18) by two experienced neurological physicians. Patients reported a family history and other neurological diseases were excluded. Healthy Individuals were recruited from the Health Examination Center in the same hospital and matched for gender, age, ethnicity, and area of residence. Informed consent was obtained from every participant. All work was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964). The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University. Their demographic information is listed in Table 1.

Genomic DNA was isolated from 5 ml peripheral blood sample by standard procedure. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of APOE gene was performed according to a previously described method (19). All coding exons and intron-exon boundaries of the PICK1 gene were amplified by PCR. The primers used are listed in Table 2 (designed based on information about the PICK1 gene obtained from a public database http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/; all primers were from Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.). The 25 μl reaction mixture included 1 μl forward primer, 1 μl reverse primer, 12.5 μl 2XHieff™ PCR Master Mix (10102ES03; YEASEN Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.), and 1 μl genomic DNA. The reaction conditions were as follows: (1) heated at 95°C for 5 min for denaturation; (2) subjected to 35 cycles of amplification by denaturation (95°C for 30 s); (3) primer annealing (annealing time for 30 s); (4) extension (72°C for 30–60 s); and (5) final extension (72°C for 10 min). Identification of the PCR-amplified products was followed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Each PCR-amplified product was directly sequenced on an ABI3730xlDNAAnalyzer automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). DNAStar was used for sequence alignment and analysis (DNAStar, Inc., Madison, WI) by two analysts independently. The consequences of variants at protein sequence were predicted according to the PICK1 cDNA sequences in GenBank (accession numbers NM_012407 and NP_036539.1, respectively).

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0. SNPStats (available online at http://bioinfo.iconcologia.net/SNPstats) was used to analyze the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) for each SNP in both AD patients and controls. Differences in allele and genotype frequencies between the AD patients and controls were assessed using chi-squared test and fisher's exact test. Linkage disequilibrium and haplotype analysis were analyzed by SHEsis (an online analysis tool: http://analysis.bio-x.cn/myAnalysis.php) (20, 21). In all tests, a p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The odds ratio (OR; 95% confidence interval) of AD cases to controls was calculated.

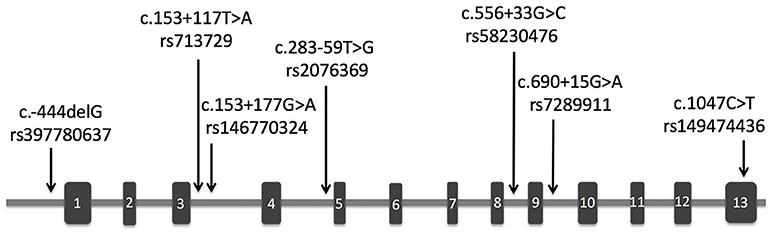

The demographic and clinical characteristics of AD cases and controls are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age and sex between the two groups. The distribution of the selected SNPs was in HWE in both groups (p > 0.05). Table 3 shows the genotypic and allelic associations of PICK1 with APOE gene in AD patients and controls. As anticipated, the frequency of the APOEε4 allele was significantly higher in AD patients than in controls. No pathogenic mutation in PICK1 gene but 7 SNPs were found in our research (rs397780637, rs713729, rs2076369, rs58230476, rs7289911, rs149474436; and rs146770324 for patient M1659 only), indicating that PICK1 gene mutation may be rare in AD patients (Figure 1). With regard to rs149474436, we observed a significantly lower frequency of the T allele (p = 0.002; OR, 0.083; 95%CI, 0.011–0.634) and TT/TC genotypes (p = 0.001) in AD patients than in the controls. When the data were stratified by APOEε4 status in Table 4, the GG homozygotes of rs397780637 were found to be associated with an increased risk of AD (p = 0.018) in APOEε4 allele carriers. The frequency of T allele of the SNP rs149474436 was significantly lower among the AD patients than the controls in APOEε4 non-carriers (p = 0.005). With regard to other SNPs, there were no significant differences in either allelic or genotypic frequency between the two groups.

Table 3. Genotypic and allelic frequencies of APOE and PICK1 gene variants in AD patients and controls.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of PICK1 gene with location of the SNPs found in our study. The rectangles and horizontal lines respectively represent exons and introns of PICK1 gene. Black arrows indicate the location of SNPs detected in this gene in our study.

Table 4. Distribution of the SNPs in AD patients and controls after stratification by APOEε4 status.

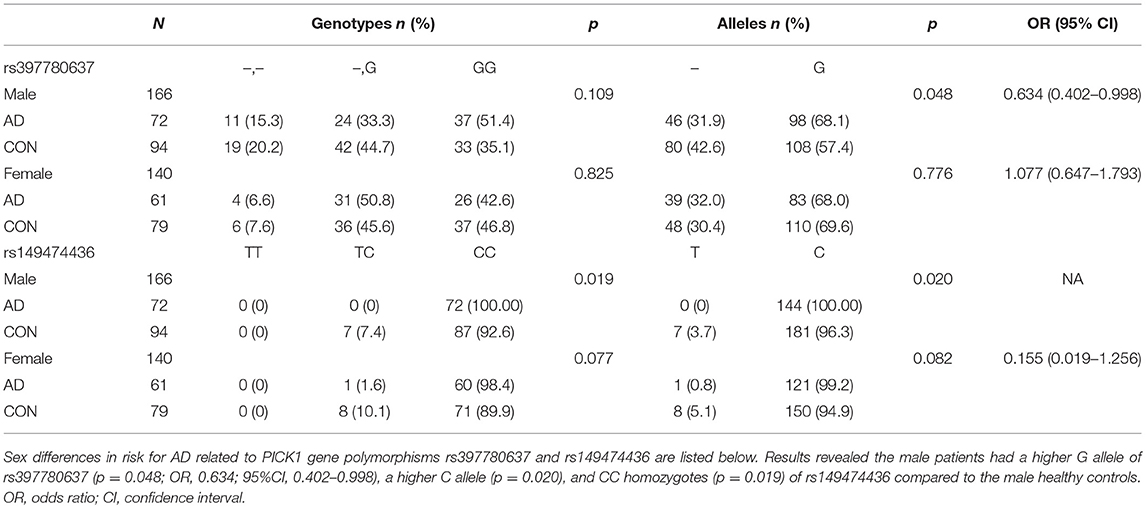

Sex differences in risk for AD related to PICK1 gene polymorphisms rs397780637 and rs149474436 are listed in Table 5. The male patients showed a higher G allele of rs397780637 (p = 0.048; OR, 0.634; 95%CI, 0.402–0.998), a higher C allele (p = 0.020) and CC homozygotes (p = 0.019) of rs149474436 compared to the male healthy controls. It is an interesting finding that the male with above SNPs seem to have a higher risk for AD.

Table 5. Frequencies of genotypes and alleles of SNP rs397780637 and rs149474436 after stratification of data by sex.

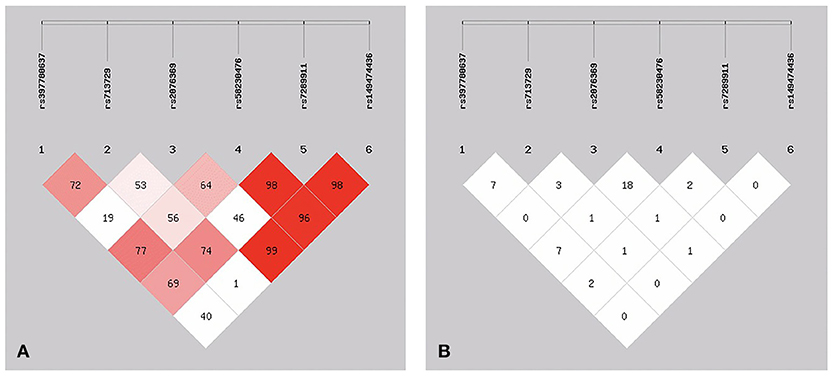

Of these SNPs, SNP146770324 was only found in patient M1659. The frequency was too low, so we chose the other six SNPs for better analysis of the linkage disequilibrium. As shown in Figure 2, three of these six SNPs showed low frequencies of recombination using parameters D′ (Figure 2A). However, r2 analysis revealed negative results (Figure 2B). These conflicting results might be related with the relatively small sample size and low frequencies of the SNPs. Further studies with larger sample size and various demographic groups are urgently needed to further validate the linkage disequilibrium.

Figure 2. The patterns of linkage disequilibrium of the six SNPs in the PICK1 gene, with their D′ (A) and r2 (B) values.

We found seven SNPs in the present study. T allele of rs149474436 may play as a protective factor while the rs397780637 GG homozygotes are found to be associated with an increased risk of AD. AD is a neurodegenerative disorder, the prevalence of which increases with aging. It has recently been shown that PICK1 plays an important role in AMPAR mediated synaptic plasticity during normal aging. The decrease in PICK1 level, which was accompanied by a reduction in GluR2, might lead to their altered subcellular distribution, and subsequently, deficits in synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus of aged rats (22). Research from Volk et al. showed that genetic deletion of PICK1 at hippocampal synapses in adult and juvenile mice might selectively influence their learning and memory through regulating AMPAR trafficking. Loss of PICK1 impaired some forms of LTP and LTD, and also the inhibitory avoidance learning only in adult mice (10). It is known that AMPAR dysfunction is related with many neurodegenerative diseases, including AD (23). PICK1 has been shown to interact with D-serine and serine racemase in the brain (12). A recent study showed that combined application of D-serine related drugs and classical antipsychotic drugs could improve the cognition of patients with schizophrenia (24), indicating the potential role of PICK1 in cognitive function. Brain insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance is now suggested to be one of the molecular pathogenesis of AD (25). Holst et al. found that PICK1 mRNA was up-regulated in type 2 diabetes and in high-fat-diet-induced obese mice, indicating the role of PICK1 in regulating insulin sensitivity (26). Besides, PICK1-GluR2 interaction has also been reported in the regulation of ischemia induced AMPAR trafficking, leading to delayed neuronal death following insults (27). AD is multi-factorial and is now accepted to be caused by multiple causes. Given the role of PICK1 in the regulation of the above-mentioned pathophysiologic processes, we assume PICK1 may also be dynamically involved in the AD pathogenesis. Further studies are needed to confirm this.

Therefore, it is possible that AD-associated symptoms can be partially associated with PICK1 dysfunction, caused by its genetic variations. The PICK1 gene has been mapped to chromosome 22q13.1 (10), and is identified to play a role in conferring susceptibility to schizophrenia (8, 28). In a recent study, Chen et al. (29) explored the role of polymorphisms of PICK1 gene (rs2076369, rs3952) in cognitive functions in schizophrenic patients. They enrolled 302 patients and analyzed the differences of cognitive functions and clinical symptoms among different genetic groups. They found that patients with rs2076369 GT heterozygotes showed better performance than TT homozygotes, suggesting the association between PICK1 gene SNPs and cognitive decline in schizophrenic patients. Therefore, we proposed that PICK1 genetic polymorphisms may be also associated with AD risk. In this study, we used direct sequencing which can provide stronger power to detect association than single-variant analyses, especially when these variants are rare or novel.

The present study shows the differences in genetic backgrounds between AD patients and healthy controls. However, the physiological and pathogenic roles of the PICK1 SNPs examined in this study (rs397780637: c.-444delG in intron variant, upstream variant 2KB, and rs149474436:c.1047C>T in the downstream variant defined as non-coding transcript variant, synonymous codon) are unknown. It is possible that it may affect the pre-mRNA splicing of the PICK1 intron, affecting its splicing or protein translation through regulating the secondary structure of mRNA. It may also influence AD risk via its linkage disequilibrium with other functional variants and nearby genes. The receptor and transporter interactions mainly occur at the PDZ and BAR domains of PICK1. Therefore, further studies aimed at identifying the mutation in these two domains seem highly warranted. However, this study has some limitations. Firstly, no association between the PICK1 polymorphisms and disease severity (such as MMSE score) is identified. Therefore, it seems less likely that the PICK1 gene is involved in the deterioration of the disease. But further studies are needed to confirm this finding. Secondly, in case-control association studies, risk of spurious associations that results from chance findings or stratification effects in the sample collection may also exist. In the present study, the sample size was relatively small and type I error cannot be ruled out, thus subgroup studies are hard to perform. Finally, participants included in this study were mainly from east China. Studies with larger sample size carried out in various demographic groups are needed to further validate the association between the variants evaluated in this study and AD risk.

In conclusion, the present case-control study suggests that PICK1 gene may be a new gene target for AD. This finding can provide a basis for future genetic studies on AD and other neurological disorders. Studies with larger sample size, various demographic groups, and whole gene sequencing technique are needed to confirm the association between PICK1 gene and AD risk. Mechanistic studies are also needed to elucidate its role in AD pathogenesis.

All data arising from this study is contained within the manuscript. The genotyping data generated during this study can be accessed through contacting the corresponding authors.

LX and YC designed this study. TS and CL gathered the demographic information. LX did the genotypic analysis and interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. YC and BZ approved the final version to be published.

This study was supported by the National 973 Project (2013CB530900, 2013CB530904), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81870826), and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LY18H090004).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We would like to thank the patients for their participation in this study. We also thank the staff of the Cancer Institute, the Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, for technical supports during the study.

AD, Alzheimer's disease; PICK1, protein interacting with C-kinase-1; AMPAR, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; APOE, apolipoprotein E; PDZ, PSD95/DIgA/ZO-1; BAR, Bin/amphiphysin/Rvs; CNS, central nervous system; NMDAR, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor; LTD, long-term depression; LTP, long-term potentiation; Aβ, Amyloid-beta protein; GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase-3β; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; HWE, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

1. Ridge PG, Hoyt KB, Boehme K, Mukherjee S, Crane PK, Haines JL, et al. Assessment of the genetic variance of late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging (2016) 41:200.e13– 20. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.02.024

2. Guerreiro R, Wojtas A, Bras J, Carrasquillo M, Rogaeva E, Majounie E, et al. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. (2013) 368:117–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211851

3. Naj AC, Jun G, Beecham GW, Wang LS, Vardarajan BN, Buros J, et al. Common variants at MS4A4/MS4A6E, CD2AP, CD33 and EPHA1 are associated with late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Nat Genet. (2011) 43:436–41. doi: 10.1038/ng.801

4. Mao YF, Guo ZY, Pu JL, Chen YX, Zhang BR. Association of CD33 and MS4A cluster variants with Alzheimer's disease in East Asian populations. Neurosci Lett. (2015) 609:235–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.10.007

5. Focant MC, Hermans E. Protein interacting with C kinase and neurological disorders. Synapse (2013) 67:532–40. doi: 10.1002/syn.21657

6. Li YH, Zhang N, Wang YN, Shen Y, Wang Y. Multiple faces of protein interacting with C kinase 1 (PICK1): structure, function, and diseases. Neurochem Int. (2016) 98:115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.03.001

7. Xu J, Xia J. Structure and function of PICK1. Neurosignals (2006) 15:190–201. doi: 10.1159/000098482

8. Hong CJ, Liao DL, Shih HL, Tsai SJ. Association study of PICK1 rs3952 polymorphism and schizophrenia. Neuroreport (2004) 15:1965–7. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200408260-00026

9. Matsuzawa D, Hashimoto K, Miyatake R, Shirayama Y, Shimizu E, Maeda K, et al. Identification of functional polymorphisms in the promoter region of the human PICK1 gene and their association with methamphetamine psychosis. Am J Psychiatry (2007) 164:1105–14. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1105

10. Volk L, Kim CH, Takamiya K, Yu Y, Huganir RL. Developmental regulation of protein interacting with C kinase 1 (PICK1) function in hippocampal synaptic plasticity and learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2010) 107:21784–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016103107

11. Hikida T, Mustafa AK, Maeda K, Fujii K, Barrow RK, Saleh M, et al. Modulation of D-serine levels in brains of mice lacking PICK1. Biol Psychiatry (2008) 63:997–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.09.025

12. Vargas-Lopes C, Madeira C, Kahn SA, Albino do Couto I, Bado P, Houzel JC, et al. Protein kinase C activity regulates D-serine availability in the brain. J Neurochem. (2011) 116:281–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07102.x

13. Nomura J, Jaaro-Peled H, Lewis E, Nunez-Abades P, Huppe-Gourgues F, Cash-Padgett T, et al. Role for neonatal D-serine signaling: prevention of physiological and behavioral deficits in adult Pick1 knockout mice. Mol Psychiatry (2016) 21:386–93. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.61

14. Alfonso S, Kessels HW, Banos CC, Chan TR, Lin ET, Kumaravel G, et al. Synapto-depressive effects of amyloid beta require PICK1. Eur J Neurosci. (2014) 39:1225–33. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12499

15. Kimura T, Whitcomb DJ, Jo J, Regan P, Piers T, Heo S, et al. Microtubule-associated protein tau is essential for long-term depression in the hippocampus. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. (2014) 369:20130144. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0144

16. Yagishita S, Murayama M, Ebihara T, Maruyama K, Takashima A. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta-mediated phosphorylation in the most C-terminal region of Protein Interacting with C Kinase 1 (PICK1) regulates the binding of PICK1 to glutamate receptor subunit GluA2. J Biol Chem. (2015) 290:29438–48. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.619668

17. McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of department of health and human services task force on Alzheimer's disease. Neurology (1984) 34:939–44.

18. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. (2011) 7:263–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005

19. Wang Z, Dai Z, Shu H, Liao X, Yue C, Liu D, et al. APOE genotype effects on intrinsic brain network connectivity in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:397. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00432-0

20. Shi YY, He L. SHEsis, a powerful software platform for analyses of linkage disequilibrium, haplotype construction, and genetic association at polymorphism loci. Cell Res. (2005) 15:97–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290272

21. Li Z, Zhang Z, He Z, Tang W, Li T, Zeng Z, et al. A partition-ligation-combination-subdivision EM algorithm for haplotype inference with multiallelic markers: update of the SHEsis (http://analysis.bio-x.cn). Cell Res. (2009) 19:519–23. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.33

22. Yu DF, Wu PF, Fu H, Cheng J, Yang YJ, Chen T, et al. Aging-related alterations in the expression and distribution of GluR2 and PICK1 in the rat hippocampus. Neurosci Lett. (2011) 497:42–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.04.023

23. Henley JM, Wilkinson KA. AMPA receptor trafficking and the mechanisms underlying synaptic plasticity and cognitive aging. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. (2013) 15:11–27.

24. Tsai G, Yang P, Chung LC, Lange N, Coyle JT. D-serine added to antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry (1998) 44:1081–9.

25. Ferreira ST, Clarke JR, Bomfim TR, De Felice FG. Inflammation, defective insulin signaling, and neuronal dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. (2014) 10(Suppl. 1):S76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.12.010

26. Holst B, Madsen KL, Jansen AM, Jin C, Rickhag M, Lund VK, et al. PICK1 deficiency impairs secretory vesicle biogenesis and leads to growth retardation and decreased glucose tolerance. PLoS Biol. (2013) 11:e1001542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001542

27. Dixon RM, Mellor JR, Hanley JG. PICK1-mediated glutamate receptor subunit 2 (GluR2) trafficking contributes to cell death in oxygen/glucose-deprived hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. (2009) 284:14230–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901203200

28. Dev KK, Henley JM. The schizophrenic faces of PICK1. Trends Pharmacol Sci. (2006) 27:574–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.09.007

Keywords: PICK1, Alzheimer's disease, single nucleotide polymorphism, gene target, genetic study

Citation: Xu L, Chen Y, Shen T, Lin C and Zhang B (2019) Genetic Analysis of PICK1 Gene in Alzheimer's Disease: A Study for Finding a New Gene Target. Front. Neurol. 9:1169. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.01169

Received: 07 August 2018; Accepted: 17 December 2018;

Published: 09 January 2019.

Edited by:

Elena Rybnikova, Pavlov Institute of Physiology (RAS), RussiaReviewed by:

Maria Shadrina, Institute of Molecular Genetics (RAS), RussiaCopyright © 2019 Xu, Chen, Shen, Lin and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yanxing Chen, Y2hlbnlhbnhpbmdAemp1LmVkdS5jbg==

Baorong Zhang, YnJ6aGFuZ0B6anUuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.