- 1Department of Medical, Surgical, Neurological, Metabolic and Aging Sciences, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli, ” Naples, Italy

- 2MRI Research Center SUN-FISM, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli, ” Naples, Italy

Impulse control behaviors (ICB) are recognized as non-motor complications of dopaminergic medications in patients with Parkinson's disease (PD). Compelling evidence suggests that ICB are not merely due to the PD-related pathology itself. Several risk factors have been identified, either demographic, clinical, genetic or neuropsychological. Neuroimaging studies have yielded controversial results regarding ICB correlates in PD and still it is not clear whether they can be triggered by the PD biology or the dopaminergic treatment stimulation. We provided an overview of the imaging studies that offered the most relevant insights into the debate about the role of drugs and disease in ICB pathophysiology. Understanding neural correlates and potential predisposing factors of these severe neuropsychiatric symptoms will be crucial to guide clinical practice and to foster preventive strategies.

Introduction

Impulse control behaviors (ICB) are neuropsychiatric symptoms characterized by impulsive acts, which are performed compulsively and are potentially detrimental to the person itself or others, severely affecting subjects' quality of life (1). ICB are mainly recognized as side-effects of treatment with dopaminergic medications in patients with Parkinson's disease (PD) (2). Compelling evidence suggests that ICB are not merely due to the disease-related pathology itself (3). The lifetime prevalence of ICB in PD patients ranges between 6–9% and increases to 14% in patients taking dopamine-replacement therapy such as dopamine agonists (DAA) or levodopa (2, 3). The risk to develop ICB increases of 2- to 3.5-fold when patients are exposed DAA (2). The prevalence did not differ between the two commonly prescribed oral short-acting DAA, pramipexole and ropinirole (17.7 vs. 15.5%) with a relatively low rate of ICB with long-acting and transdermal DAA (6.6% pramipexole prolonged release and 4.9% for rotigotine) (2, 4). However, not all PD patients develop ICB under dopaminergic treatment. Several risk factors have been proposed, either clinical (i.e., younger age at PD onset, male sex, depression) (3) or genetic (i.e., polymorphisms in dopaminergic, glutamatergic and serotoninergic and opioid receptors) (5, 6).

Interestingly, ICB also occur in patients with restless legs syndrome (7, 8) or prolactinoma (9) under DAA, and this may support the role of the drugs in triggering these neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Modern neuroimaging techniques have been widely tested to support PD diagnosis (i.e., positron emission tomography, PET and single-photon emission computed tomography, SPECT) as well as to provide further insights into motor and non-motor symptoms pathophysiology, complications and treatment-related effects (i.e., PET and magnetic resonance imaging, MRI) (10).

PET and SPECT studies have been extensively applied to analyze neural correlates underpinning ICB in PD (11–14). By means of pre- and post-synaptic tracers, these studies provided crucial insights about the nigrostriatal functioning characterizing ICB patients. Recently, highly selective D2/D3 tracers have been also implemented, allowing to detect the presence of widespread extra-striatal changes related to ICB.

Structural MRI changes have been also observed in PD patients with ICB. Gray matter atrophy as well as corticometric changes across several brain areas involved in behavioral modulation (i.e., orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortices) are the most frequent findings related to the ICB presence and severity in PD (15, 16). However, there is also evidence of no morphometric changes (17).

Functional MRI studies (18–21) were performed in resting condition as well as during reward tasks in ICB patients, and were used to shed light on specific reward processing abnormalities. Overall, these studies have consistently demonstrated a dysfunction within and between dopaminergic neural circuitries involving crucial subcortical hubs (i.e., ventral striatum, VS, amygdala) and limbic-cognitive cortical areas (i.e., anterior cingulate and frontal cortices). Interestingly, the most relevant brain areas in the pathogenesis of ICB are involved in the so-called neurocognitive networks, namely the default-mode (DMN), the salience (SN) and the central-executive (CEN) networks.

The DMN encompasses mainly precuneus and posterior cingulate, bilateral inferior-lateral-parietal and ventromedial frontal cortices. It is involved in cognitive processing and mind-wandering and becomes deactivated during specific goal-directed behaviors. The CEN is involved in executive control and decision-making and operates through medio-frontal areas, including anterior cingulate and para-cingulate cortices. The SN is a limbic-paralimbic network that plays an important role in orienting attention toward salient stimuli and facilitating goal-directed behaviors, reward processing and interoceptive awareness (22). It encompasses manly the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the bilateral VS. The dynamic interplay between these networks is critical to allow an individual to be behaviorally and cognitively efficient (23), and this highlights their potential relevance in ICB pathophysiology.

Overall, most imaging studies applied cross-sectional designs, yielding controversial results. Thus, it is not possible to rule out whether these findings reflect the effect of chronic dopaminergic treatment or represent a neural pattern predisposing to ICB (24).

Here, we aim to review the most relevant imaging studies that provide a contribution to the debate about the role of drugs and disease in the pathogenesis of ICB in PD.

Search Strategy

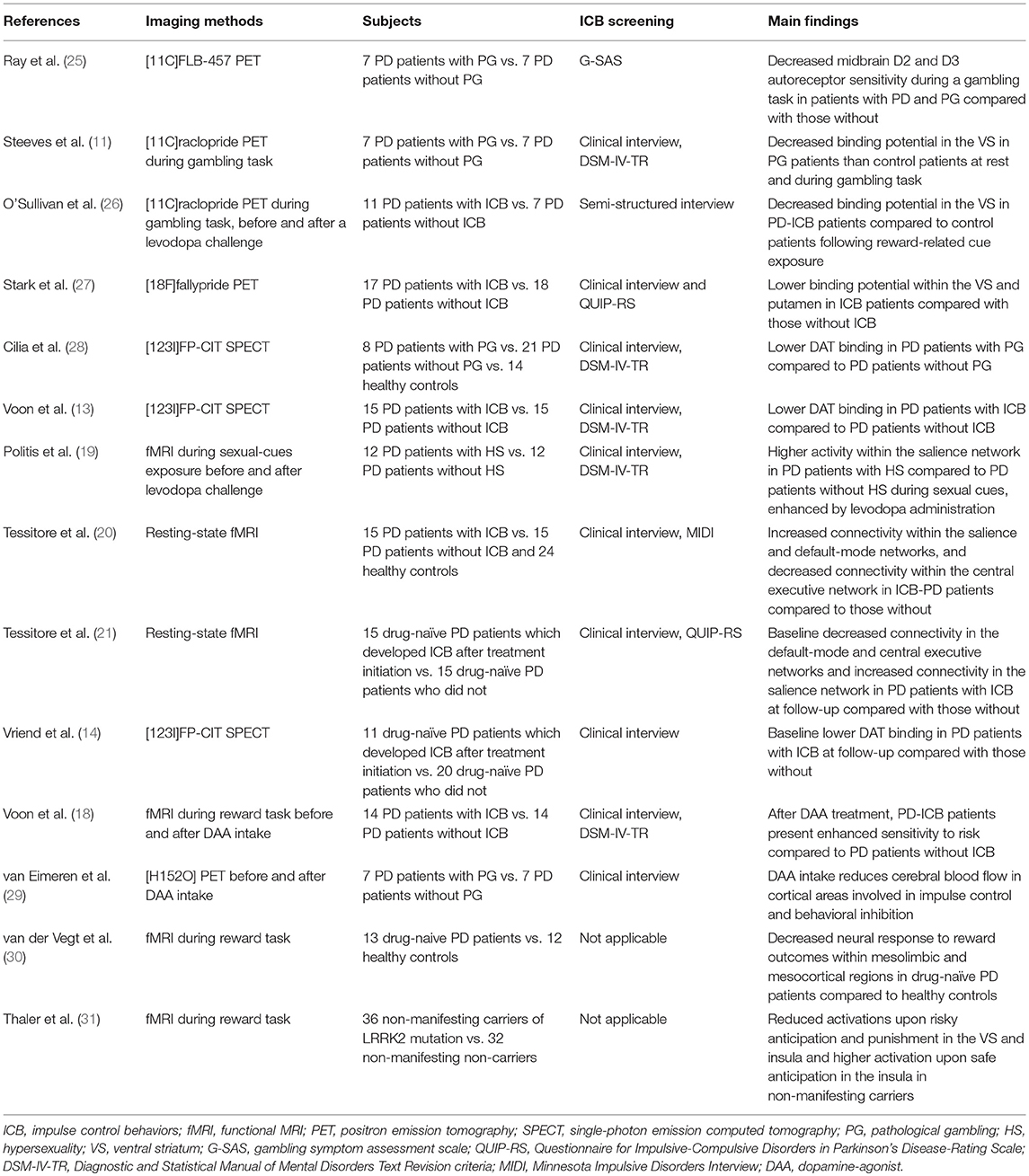

Articles published on PubMed until June 2018 were checked for the purpose of this review. “Parkinson's disease” were cross-referenced with “impulse control disorders” and synonymies and “magnetic resonance imaging,” “positron emission tomography,” “impulsive compulsive disorders,” “reward system,” “dopamine agonists,” “levodopa.” Two independent observers (RDM and AR) evaluated the results (n = 984), excluding duplicates and articles judged irrelevant by title and abstract screening. The same raters performed the quality check of selected studies and the most relevant ones for the topic were finally included in the review (Table 1).

Neuroimaging Studies to Analyze Dopaminergic Signaling in PD Patients With ICB

The role of dopaminergic signaling in ICB development is suggested by both PD pathophysiology and DAA targeting. The most prescribed DAA are highly selective on D3 receptors, which are mainly located in the mesolimbic circuit and are thought to be involved in the reward processing (32). Interestingly, animal studies showed that nigrostriatal degeneration itself may result in increasing rewarding properties of D2 and D3 agonists in the mesolimbic pathway (33). Polymorphisms in D2 as well as D1-like receptors genes, potentially leading to abnormal neurotransmitters functioning, have been linked to increased ICB susceptibility in PD (6). On the other hand, chronic dopaminergic treatment may induce long-term abnormalities in the phasic and tonic activity of dopaminergic neurons, potentially leading to changes in post and pre-synaptic receptors density and properties (34, 35). In preclinical studies, these changes have been linked to reward anticipation and risk-taking behaviors [see for a review (24)]. Taken together these findings suggest that both disease and drugs seem to be synergistically involved in triggering ICB symptoms.

Neuroimaging studies are in line with this evidence. Indeed, in a small PET study using [11C]FLB-457, a radiotracer with high affinity for extra-striatal receptors, decreased midbrain D2 and D3 autoreceptor sensitivity have been shown during a gambling task in patients with PD and gambling compared with those without (25). This may reflect enhanced striatal dopamine release in PD patients with ICB when exposed to reward stimuli. Two PET studies (11, 26) found that PD-ICB patients present decreased [11C]raclopride binding potential in the VS during reward cues exposure compared to PD patients without ICB. As [11C]raclopride is highly selective for post-synaptic D2 receptors, a reduced binding may suggest again the presence of a “hyperdopaminergic state” in the VS of patients with PD-ICB. This effect was observed in “off” condition, as well as after a levodopa challenge (26). Interestingly, no binding change was determined by levodopa intake upon neutral cues (26). Recently, more selective tracers have been implemented, such as [18F]fallypride, which is a high affinity D2-like receptors ligand that can measure D2/D3 binding potential throughout the meso-cortico-limbic network. This tracer was used in a cohort of PD patients with ICB compared with those without, confirming that the presence of a reduced binding potential within the VS and putamen may be a marker of increased dopaminergic levels (27). Moreover, this study showed that the integrity of the dopaminergic projections emerging from the midbrain differentiates PD patients with ICB from those without, and increases along with severity of symptoms (27). This finding is in line with the hypothesis that ICB may result from the imbalanced involvement of the more affected dorsal and the less affected VS in the early stages of PD. Thus, while dopaminergic treatment partially restores the normal functioning within the dorsal striatum (improving motor symptoms), the dopaminergic treatment may “overdose” the VS, potentially triggering affective disturbances and ICB (36, 37).

Other neuroimaging approaches have confirmed the presence of dopaminergic signaling abnormalities in patients with PD and ICB. Indeed, reduced striatal dopamine transporter (DAT) density has been reliably reported in PD-ICB patients compared to PD patients without ICB (13, 28). This is of interest, as the DAT binding may decrease following either mesolimbic projections neurodegeneration or increased dopaminergic synaptic firing.

In a functional MRI (fMRI) study, patients with PD and hypersexuality exposed to sexual cues had higher activity within the SN compared to patients with PD without ICB (19). Moreover, this study showed that subjective sexual desire was enhanced by levodopa administration (19). A similar pattern of increased SN connectivity has been also shown at rest in PD patients with ICB compared to those without (20). Functional connectivity abnormalities were also found to be correlated to ICB severity (20).

In summary, different neuroimaging techniques have been used to analyze the integrity of striatal and extra-striatal dopaminergic pathways in PD patients with and without ICB. The presence of a specific “hyperdopaminergic” state in the brain of patients experiencing ICB have been consistently highlighted. An important limitation is that these studies have mainly enrolled PD patients with a long history of PD as well as ICB, which may both influence the reward and impulse-control pathways themselves. Indeed, after ICB emergence, progressive neuroplasticity processes involving mainly dopaminergic circuitries may occur, eventually leading to consolidation of pathological habits (38). Thus, even though with caution, these studies corroborate the idea that PD-related pathology and dopaminergic treatment may synergistically act on the risk to develop ICB in PD patients.

Neuroimaging Studies to Analyze Reward Processing in PD Patients With ICB

Dopaminergic medications can influence rewarding processing, by enhancing learning from positive feedback and impairing learning from negative feedback (39, 40). Moreover, these drugs has been link to increased impulsivity (24).

Reward processing changes after dopaminergic drugs administration has been studied in healthy subjects as well as in patients with restless legs syndrome in order to describe pharmacological effects not biased from neurodegenerative pathology. Pessiglione et al. (41) performed a fMRI study to assess the effects of either levodopa (100 mg) or an antagonist of dopamine receptors (1 mg of haloperidol) on both brain activity and behavioral choice in healthy subjects. They found that during instrumental learning, levodopa increases while haloperidol reduces dopaminergic functioning in the VS along with the magnitude of reward prediction error. Accordingly, compared to subjects treated with haloperidol, subjects treated with levodopa showed greater propensity to choose the most rewarding action, supporting the hypothesis that dopamine-dependent modulation of striatal activity can account for how the healthy brain uses prediction errors to modulate future decisions (41). Another crucial component of the reward processing is the temporal impulsivity, which is the preference for smaller but sooner over larger but later rewards (42). This phenomenon is related to an excessive discounting of future rewards and has been observed in patients with drugs addiction (43). This function was tested in a cohort of young healthy subjects by means of a task-related and pharmacological fMRI paradigm (44). The study revealed that levodopa increases preference for more immediate rewards, likely increasing impulsivity in healthy brains. This result parallels with a corresponding increased neural representation in the striatum, further supporting the idea that a hyperfunctioning in the dopamine system is related to abnormal decision-making.

Along with levodopa, the effect of DAA treatment on the reward processing was tested in both healthy and non-healthy subjects as well. A double-blind study compared results from a probabilistic reward task performed after either a single low dose of pramipexole (0.5 mg) or placebo (45), revealing that DAA may affect the acquisition of reward-related behaviors (45). A similar effect was found also in a cohort of subjects with restless legs syndrome without any history of pathological gambling (46). In this study, fMRI scans were obtained during a gambling game task, once whilst subjects were taking their regular medication (i.e., low dose DAA) and after a washout period. Upon expectation of rewards, significant VS activation was detected only when subjects were taking DAA, but not when they were in the washout period. Contrariwise, upon omission of rewards, the observed VS signal under DAA were significantly different from what revealed during the washout (46).

These results parallel with several evidence coming from PD patients with ICB. A task-related and pharmacological fMRI study performed before and after DAA treatment, showed that PD-ICB patients under DAA present enhanced sensitivity to risk compared to PD patients without ICB in the same experimental condition (18). DAA intake has been also shown to reduce cerebral blood flow in cortical areas involved in impulse control and behavioral inhibition (29).

However, it should be noted that PD results from the degeneration of dopaminergic projections involved in the reward processing itself. By contrast, dysfunctions within the reward system are difficult to study in PD as most patients are treated with dopaminergic drugs. In this context, a fMRI task-related paradigm was used in a small group of drug-naïve PD patients performing a simple two-choice gambling task (30). In this study, PD patients compared to healthy controls showed decreased neural response to reward outcomes within several mesolimbic and mesocortical nodes, such as the ventral putamen, ventral tegmental area, thalamus and hippocampus. In this framework, reward processing abnormalities were also found in subjects at high risk for future development of PD, such as a cohort of non-manifesting carriers of the G2019S mutation in the LRRK2 gene (31). Indeed, this event-related fMRI study showed differences between non-manifesting carriers and non-carriers when comparing activations in key reward brain areas upon safe and risky anticipation and punishing outcomes. Thus, several nodes of the meso-cortico-limbic reward system are already compromised in the early (and also preclinical) stages of the disease as they are also direct targets of PD-related neurodegeneration.

In summary, even in the absence of manifest ICB symptoms as well as PD pathology, chronic dopaminergic medication was shown to severely impair the reward processing. Although limited, neuroimaging evidence of altered reward-processing in PD patients even in the absence of DAA treatment have been provided.

Neuroimaging Studies to Predate ICB Development in PD Patients

To date, only a few studies have been designed to find potential neuroimaging biomarkers able to predict future development of ICB in PD. This is crucial, as previous studies did not allow to disentangle the complex interplay between drugs and disease in ICB pathophysiology. Vriend et al. (14) performed a retrospective analysis of DAT imaging data acquired in a cohort of drug-naïve PD patients that developed ICB symptoms after dopaminergic treatment initiation. They found that the presence of reduced DAT availability in the VS at baseline is able to predate ICB development after treatment initiation. Dopamine reuptake via striatal DAT is the most important mechanism acting to remove dopamine from the synapse. Thus, PD patients with lower DAT availability could have increased striatal dopamine levels (14, 28) even at the time of the diagnosis. This important finding corroborates the hypothesis that PD patients with higher risk to develop ICB may present at baseline a relatively preserved striato-cortical functioning. As we mentioned above, increased dopaminergic signaling in the VS can interfere with the processing of negative feedback during reward-based learning. Neurobehavioral studies (47, 48) have shown that the high dopaminergic firing occurring upon reward cues is able to reinforce hippocampal inputs and inhibits prefrontal connections on the VS. In the absence of feedback top-down processes, this divergent effect may impair the ability to shift behavioral focus when cues salience change, potentially looping the reward system. A similar condition may occur in PD patients with a “hyperdopaminergic” state in the VS (i.e., patients at higher risk to develop ICB) and then exposed to the dopamine-mimetic treatment (49), leading to impulsive-compulsive behaviors. However, further investigations are warranted to clarify which predisposing factors, potentially genetic (5, 6), may determine this trend toward increased dopaminergic response. In this framework, different polymorphisms in several neurotransmitters receptors genes, potentially leading to high dopaminergic striatal levels, have been linked to increased ICB susceptibility in PD (6).

More recently, resting-state fMRI was used to analyze the intrinsic functional connectivity within and between the major neurocognitive networks in a cohort of drug-naïve PD patients that developed ICB (ICB+) after treatment initiation compared with PD patients who did not (ICB–) (21). In physiological condition, the SN modulates the inter-network connectivity between the CEN and the DMN, resulting in a functional anti-correlation between these two networks (23, 50). This dynamic balance is crucial, as it is thought to drive an efficient behavioral and cognitive outcome (23). When comparing ICB+ and ICB- patients before treatment initiation, an increased resting-state connectivity within the SN was found in ICB+ patients (21). This is of interest, as the SN encompasses cortical and subcortical nodes that are affected by PD-related pathology itself, such as the VS (51, 52). The presence of an increased connectivity within this network may again rely on pre-existing abnormal dopaminergic signaling even at the disease onset, and may also explain the development of such behavioral complications when patients are exposed to dopaminergic medication. Interestingly, the study also revealed that the anti-correlation between DMN and CEN is lost at the time of diagnosis in ICB+ patients and this inverse pattern showed a positive correlation with the time to ICB onset (i.e., the less the anti-correlation between DMN and CEN the earlier is the emergence of ICB). Notably, no differences have been shown between ICB+ and ICB- patients in terms of total levodopa equivalent daily dose (including DAA) at the time of ICB development (21). Thus, these connectivity changes may represent a potential biomarker to predict emergence of ICB symptoms before starting any dopaminergic drugs.

In summary, longitudinal neuroimaging studies on premorbid ICB population are limited. However, they support the hypothesis that a pre-existing vulnerability to ICB development may be present in a specific subset of PD patients, likely related to PD-pathology, involving both dopaminergic signaling and reward processing, which are in turn affected by dopaminergic medications.

Conclusions

The relationship between PD pathology, DAA treatment and ICB development is complex. Neuroimaging studies have provided crucial insights to support the presence of increased dopaminergic firing in response to reward stimuli in the cortico-striato-cortical pathway in PD patients more prone to develop ICB. Dopaminergic treatment exposure may overdrive this pathway and also induce further dopamine receptors changes, leading to the development of such behavioral disturbances. Future multimodal imaging studies able to look at several aspects of the dopaminergic cortical and subcortical signaling, as well as prospective longitudinal designs, will allow to disentangle how drugs and disease may interplay to trigger these relevant neuropsychiatric symptoms. Understanding neural correlates and potential predisposing factors of these severe behavioral symptoms will be crucial to guide clinical practice and to foster preventive strategies.

Author Contributions

RD study concept and design, acquisition of data, drafting the article. AT drafting the article and revising it critically for intellectual content. AR critically revision of manuscript for intellectual content. GT critically revision of manuscript for intellectual content.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Atmaca M. Drug-induced impulse control disorders: a review. Curr Clin Pharmacol. (2014) 9:70–4. doi: 10.2174/1574884708666131111202954

2. Weintraub D, Koester J, Potenza MN, Siderowf AD, Stacy M, Voon V, et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: a cross-sectional study of 3090 patients. Arch Neurol. (2010) 67:589–95. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.65

3. Weintraub D, David AS, Evans AH, Grant JE, Stacy M. Clinical spectrum of impulse control disorders in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. (2015) 30:121–7. doi: 10.1002/mds.26016

4. Rizos A, Sauerbier A, Antonini A, Weintraub D, Martinez-Martin P, Kessel B, et al. A European multicentre survey of impulse control behaviours in Parkinson's disease patients treated with short- and long-acting dopamine agonists. Eur J Neurol. (2016) 23:1255–61 doi: 10.1111/ene.13034

5. Vallelunga A, Flaibani R, Formento-Dojot P, Biundo R, Facchini S, Antonini A. Role of genetic polymorphisms of the dopaminergic system in Parkinson's disease patients with impulse control disorders. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. (2012) 18:397–9. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.10.019

6. Erga AH, Dalen I, Ushakova A, Chung J, Tzoulis C, Tysnes OB et al. Dopaminergic and opioid pathways associated with impulse control disorders in parkinson's disease. Front Neurol. (2018) 9:109. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00109

7. Tippmann-Peikert M, Park JG, Boeve BF, Shepard JW, Silber MH. Pathologic gambling in patients with restless legs syndrome treated with dopaminergic agonists. Neurology (2007) 68:301–3. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252368.25106.b6

8. Dang D, Cunnington D, Swieca J. The emergence of devastating impulse control disorders during dopamine agonist therapy of the restless legs syndrome. Clin Neuropharmacol. (2011) 34:66–70. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e31820d6699

9. Thondam SK, Alusi S, O'Driscoll K, Gilkes CE, Cuthbertson DJ, Daousi C. Impulse control disorder in a patient on long-term treatment with bromocriptine for a macroprolactinoma. Clin Neuropharmacol. (2013) 36:170–2. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e31829fc165

10. Lehericy S, Vaillancourt DE, Seppi K, Monchi O, Rektorova I, Antonini A, et al. The role of high-field magnetic resonance imaging in parkinsonian disorders: pushing the boundaries forward. Mov Disord. (2017) 32:510–25. doi: 10.1002/mds.26968

11. Steeves TDL, Miyasaki J, Zurowski M, Lang AE, Pellecchia G, Van Eimeren T, Ballanger B, Steeves TD, Houle S, et al. Increased striatal dopamine release in Parkinsonian patients with pathological gambling: a [11C]raclopride PET study. Brain (2009) 132:1376–85. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp054

12. Cilia R, Cho SS, Van Eimeren T, Marotta G, Siri C, Ko JH, et al. Pathological gambling in patients with Parkinson's disease is associated with fronto-striatal disconnection: a path modeling analysis. Mov Disord. (2011). 26:225–33. doi: 10.1002/mds.23480

13. Voon V, Rizos A, Chakravartty R, Mulholland N, Robinson S, Howell NA, et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson's disease: decreased striatal dopamine transporter levels. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2014) 85:148–52. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-305395

14. Vriend C, Nordbeck AH, Booij J, van der Werf YD, Pattij T, Voorn P, et al. Reduced dopamine transporter binding predates impulse control disorders in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. (2014) 29:904–11. doi: 10.1002/mds.25886

15. Biundo R, Weis L, Facchini S, Formento-Dojot P, Vallelunga A, Pilleri M, et al. Patterns of cortical thickness associated with impulse control disorders in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. (2015) 30:688–95. doi: 10.1002/mds.26154

16. Tessitore A, Santangelo G, De Micco R, Vitale C, Giordano A, Raimo S, et al. Cortical thickness changes in patients with Parkinson's disease and impulse control disorders. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. (2016) 24:119–25. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.10.013

17. Carriere N, Lopes R, Defebvre L, Delmaire C, Dujardin K. Impaired corticostriatal connectivity in impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease. Neurology (2015) 84:2116–23. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001619

18. Voon V, Gao J, Brezing C, Symmonds M, Ekanayake V, Fernandez H, et al. Dopamine agonists and risk: impulse control disorders in Parkinson's; disease. Brain (2010) 134:1438–46. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr080

19. Politis M, Loane C, Wu K, O'Sullivan SS, Woodhead Z, Kiferle L, et al. Neural response to visual sexual cues in dopamine treatment-linked hypersexuality in Parkinson's disease. Brain (2013) 136:400–11. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws326

20. Tessitore A, Santangelo G, De Micco R, Giordano A, Raimo S, Amboni M, et al. Resting-state brain networks in patients with Parkinson's disease and impulse control disorders. Cortex (2017) 94:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2017.06.008

21. Tessitore A, De Micco R, Giordano A, di Nardo F, Caiazzo G, Siciliano M, et al. Intrinsic brain connectivity predicts impulse control disorders in patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. (2017) 32:1710–9. doi: 10.1002/mds.27139

22. Menon V, Uddin LQ. Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Struct Funct. (2010) 214:655–67. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0262-0

23. Menon V. Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn Sci. (2011) 15:483–506. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.08.003

24. Voon V, Napier TC, Frank MJ, Sgambato-Faure V, Grace AA, Rodriguez-Oroz M, et al. Impulse control disorders and levodopa-induced dyskinesias in Parkinson's disease: an update. Lancet Neurol. (2017) 16:238–50. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30004-2

25. Ray NJ, Miyasaki JM, Zurowski M, Ko JH, Cho SS, Pellecchia G, et al. Extrastriatal dopaminergic abnormalities of DA homeostasis in Parkinson's patients with medication-induced pathological gambling: a [11C] FLB-457 and PET study. Neurobiol Dis (2012) 48:519–25. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.06.021

26. O'Sullivan SS, Wu K, Politis M, Lawrence AD, Evans AH, Bose SK, et al. Cue-induced striatal dopamine release in Parkinson's disease-associated impulsive-compulsive behaviours. Brain (2011) 134:969–78. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr003

27. Stark AJ, Smith CT, Lin YC, Petersen KJ, Trujillo P, van Wouwe NC, et al. Nigrostriatal and mesolimbic D(2/3) receptor expression in parkinson's disease patients with compulsive reward-driven behaviors. J Neurosci. (2018) 38:3230–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3082-17.2018

28. Cilia R, Ko JH, Cho SS, van Eimeren T, Marotta G, Pellecchia G, et al. Reduced dopamine transporter density in the ventral striatum of patients with Parkinson's disease and pathological gambling. Neurobiol Dis. (2010) 39:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.03.013

29. Van Eimeren T, Pellecchia G, Cilia R, Ballanger B, Steeves TD, Houle S, et al. Drug-induced deactivation of inhibitory networks predicts pathological gambling in PD. Neurology (2010) 75:1711–6. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fc27fa

30. van der Vegt JP, Hulme OJ, Zittel S, Madsen KH, Weiss MM, Buhmann C, et al. Attenuated neural response to gamble outcomes in drug-naive patients with Parkinson's disease. Brain (2013) 136:1192–203. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt027

31. Thaler A, Gonen T, Mirelman A, Helmich RC, Gurevich T, Orr-Urtreger A, et al. Altered reward-related neural responses in non-manifesting carriers of the Parkinson disease related LRRK2 mutation. Brain Imaging Behav. doi: 10.1007/s11682-018-9920-2. [Epub ahead of print].

32. Ahlskog JE. Pathological behaviors provoked by dopamine agonist therapy of Parkinson's disease. Physiol Behav. (2011) 104:168–72. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.04.055

33. Engeln M, Ansquer S, Dugast E, Bezard E, Belin D, Fernagut PO. Multi-facetted impulsivity following nigral degeneration and dopamine replacement therapy. Neuropharmacology (2016) 109:60–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.05.013

34. Engeln M, Fasano S, Ahmed SH, Cador M, Baekelandt V, Bezard E, et al. Levodopa gains psychostimulant-like properties after nigral dopaminergic loss. Ann Neurol. (2013) 74:140–4. doi: 10.1002/ana.23881

35. Engeln M, Ahmed SH, Vouillac C, Tison F, Bezard E, Fernagut PO. Reinforcing properties of pramipexole in normal and parkinsonian rats. Neurobiol Dis. (2013) 49:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.08.005

36. Cools R, Barker RA, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW. Enhanced or impaired cognitive function in Parkinson's disease as a function of dopaminergic medication and task demands. Cereb Cortex (2001) 11:1136–43.

37. Wise RA. Roles for nigrostriatal—not just mesocorticolimbic—dopamine in reward and addiction. Trends Neurosci. (2009) 32:517–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.06.004

38. Belin D, Everitt BJ. Neuroplasticity in addiction: cellular and transcriptional perspectives Cocaine seeking habits depend upon dopamine-dependent serial connectivity linking the ventral with the dorsal striatum. Neuron (2008) 57:432–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.019

39. Tremblay L, Hollerman JR, Schultz W. Modifications of reward expectation-related neuronal activity during learning in primate striatum. J Neurophysiol. (1998) 80:964–77. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.2.964

40. Frank MJ, Seeberger LC, O'Reilly RC. By carrot or by stick: cognitive reinforcement learning in parkinsonism. Science (2004) 306:1940–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1102941

41. Pessiglione M, Seymour B, Flandin G, Dolan R, Frith CD. Dopamine-dependent prediction errors underpin reward-seeking behaviour in humans. Nature (2006) 442:1042–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05051

42. Cardinal RN, Winstanley CA, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Limbic corticostriatal systems and delayed reinforcement. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2004) 1021:33–50. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.004

43. Bickel WK, Miller ML, Yi R, Kowal BP, Lindquist DM, Pitcock JA. Behavioral and neuroeconomics of drug addiction: competing neural systems and temporal discounting processes. Drug Alcohol Depend (2007) 90:S85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.016

44. Pine A, Shiner T, Seymour B, Dolan RJ. Dopamine, Time, and Impulsivity in Humans. J Neurosci. (2010) 30:8888–96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6028-09.2010

45. Pizzagalli DA, Evins AE, Schetter EC, Frank MJ, Pajtas PE, Santesso DL, et al. Single dose of a dopamine agonist impairs reinforcement learning in humans: behavioural evidence from a laboratory-based measure of reward responsiveness. Psychopharmacol. (2008) 196:221–32. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0957-y

46. Abler B, Hahlbrock R, Unrath A, Gron G, Kassubek J. At-risk for pathological gambling: imaging neural reward processing under chronic dopamine agonists. Brain (2009) 132:2396–402. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp170

47. Goto Y, Grace AA. Dopaminergic modulation of limbic and cortical drive of nucleus accumbens in goal-directed behavior. Nat Neurosci. (2005) 8:805–12. doi: 10.1038/nn1471

48. Sesack SR, Grace AA. Cortico-basal ganglia reward network: microcircuitry. Neuropsychopharmacology (2010) 35:27–47. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.93

49. Napier TC, Corvol JC, Grace AA, Roitman JD, Rowe J, Voon V, et al. Linking neuroscience with modern concepts of impulse control disorders in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. (2015) 30:141–9. doi: 10.1002/mds.26068

50. Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2005) 102:9673–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102

51. Christopher L, Koshimori Y, Lang AE, Criaud M, Strafella AP. Uncovering the role of the insula in non-motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease. Brain (2014) 137:2143–54. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu084

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, impulse control behaviors, MRI, PET, reward system

Citation: De Micco R, Russo A, Tedeschi G and Tessitore A (2018) Impulse Control Behaviors in Parkinson's Disease: Drugs or Disease? Contribution From Imaging Studies. Front. Neurol. 9:893. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00893

Received: 07 August 2018; Accepted: 01 October 2018;

Published: 25 October 2018.

Edited by:

Mayela Rodríguez-Violante, Instituto Nacional de Neurología y Neurocirugía (INNN), MexicoReviewed by:

Paolo Calabresi, University of Perugia, ItalyAvner Thaler, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Israel

Copyright © 2018 De Micco, Russo, Tedeschi and Tessitore. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alessandro Tessitore, YWxlc3NhbmRyby50ZXNzaXRvcmVAdW5pY2FtcGFuaWEuaXQ=

Rosa De Micco

Rosa De Micco Antonio Russo

Antonio Russo Gioacchino Tedeschi

Gioacchino Tedeschi Alessandro Tessitore

Alessandro Tessitore