94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Neurol. , 21 March 2018

Sec. Neuro-Oncology and Neurosurgical Oncology

Volume 9 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.00127

Yu-Hang Zhao1†

Yu-Hang Zhao1† Ze-Fen Wang2†

Ze-Fen Wang2† Chang-Jun Cao1

Chang-Jun Cao1 Hong Weng3

Hong Weng3 Cheng-Shi Xu1

Cheng-Shi Xu1 Kai Li1

Kai Li1 Jie-Li Li1

Jie-Li Li1 Jing Lan1

Jing Lan1 Xian-Tao Zeng3

Xian-Tao Zeng3 Zhi-Qiang Li1*

Zhi-Qiang Li1*

Background and objective: Promoter status of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) has been widely established as a clinically relevant factor in glioblastoma (GBM) patients. However, in addition to varied therapy schedule, the prognosis of GBM patients is also affected by variations of age, race, primary or recurrent tumor. This study comprehensively investigated the association between MGMT promoter status and prognosis in overall GBM patients and in different GBM subtype including new diagnosed patients, recurrent patients and elderly patients.

Methods: A comprehensive search was performed using PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane databases to identify literatures (published from January 1, 2005 to April 1, 2017) that evaluated the associations between MGMT promoter methylation and prognosis of GBM patients.

Results: Totally, 66 studies including 7,886 patients met the inclusion criteria. Overall GBM patients with a methylated status of MGMT receiving temozolomide (TMZ)-containing treatment had better overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) [OS: hazard ratio (HR) = 0.46, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.41–0.52, p < 0.001, Bon = 0.017; PFS: HR = 0.48, 95% CI 0.40–0.57, p < 0.001, Bon = 0.014], but no significant advantage on OS or PFS in GBM patients with TMZ-free treatment was observed (OS: HR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.91–1.03, p = 0.08, Bon = 1; PFS: HR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.57–1.02, p = 0.068, Bon = 0.748). These different impacts of MGMT status on OS were similar in newly diagnosed GBM patients, elderly GBM patients and recurrent GBM. Among patients receiving TMZ-free treatment, survival benefit in Asian patients was not observed anymore after Bonferroni correction (Asian OS: HR = 0.78, 95% CI 0.64–0.95, p = 0.02, Bon = 0.24, I2 = 0%; PFS: HR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.50–0.94, p = 0.02, Bon = 0.24). No benefit was observed in Caucasian receiving TMZ-free therapy regardless of Bonferroni adjustment.

Conclusion: The meta-analysis highlights the universal predictive value of MGMT methylation in newly diagnosed GBM patients, elderly GBM patients and recurrent GBM patients. For elderly methylated GBM patients, TMZ alone therapy might be a more suitable option than radiotherapy alone therapy. Future clinical trials should be designed in order to optimize therapeutics in different GBM subpopulation.

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most frequent primary malignant brain tumor with poor prognosis. From 2005, radiotherapy combined with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide (TMZ) after surgical maximal safe resection, namely STUPP treatment, has been widely used for newly diagnosed GBM patients less than 65 years old (1, 2). A phase III trial showed that tumor treatment fields, a novel cancer treatment modality, had similar efficacy as chemotherapy regimens in recurrent GBM (3). However, limited improvement of the overall survival (OS) has been achieved in patients with GBM (4, 5). Therefore, identification of biomarkers determining tumor response to treatment may help in developing targeted therapy or optimize patients’ management.

O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) is a ubiquitously expressed DNA repair enzyme. MGMT protein removes alkyl adducts at the O6 position of guanine, thereby neutralizing the cytotoxic effects of alkylating agents such as TMZ (6, 7). High MGMT expression in glioma cells is the predominant mechanism underlying tumor resistance to alkylating agents (8–10). Meanwhile, status of MGMT promoter methylation is associated with tumor response to TMZ therapy (11, 12). MGMT promoter methylation, resulting in transcriptional silencing, correlates well with improved survival in GBM patients exposed to alkylating agents’ treatment (13–15). Results of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and National Cancer Institute of Canada trial indicated that MGMT promoter methylation was the strongest predictor for outcome and benefit from TMZ (2, 16). Accordingly, this biomarker is currently used for clinical decision-making and stratifying or selecting GBM patients for clinical trials (17).

Although MGMT promoter methylation has a strong influence on response to TMZ and clinical outcome in GBM patients, its prognostic value on GBM patients remains ambiguous. Some studies indicated that it was associated with better outcome in methylated patients receiving TMZ-containing therapy (18, 19). But some studies also showed that it conferred survival benefit in methylated patients receiving TMZ-free therapy (21, 22). So it is necessary to review whether the survival benefit from MGMT methylation is therapy dependent or independent, which will define MGMT promoter methylation as a predictive or prognostic biomarker. In addition to varied therapy schedules, the outcome and survival of GBM patients may be affected by other prognostic variables, including primary or recurrent tumor, age and race. Thus, we conducted a comprehensive and exact analysis on the association between MGMT promoter methylation and prognosis in overall GBM patients as well as in different GBM subpopulation, including newly diagnosed patients, recurrent patients, elderly patients and patients with different races. This meta-analysis will provide an updated and precise review on the clinical value of MGMT promoter methylation on progression-free survival (PFS) and OS in GBM patients.

We performed a systematic review to identify all related articles from PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library covering the association of MGMT methylation with prognosis and data of hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The articles enrolled in analysis were published between January 1, 2005 and April 1, 2017. The following subject terms were used: (1) “Glioblastoma,” “GBM,” “High-Grade Glioma,” “Astrocytoma, Grade IV,” “Astrocytomas, Grade IV,” “Glioblastoma Multiform,” or “Glioblastomas”; (2) “MGMT” or “O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase.” The eligible studies were restricted to human beings.

We evaluated the eligible studies only if all the following conditions were met: (1) studies investigated the relation between MGMT promoter methylation and survival in GBM patients; (2) treatment schedules and testing methods were all included; (3) HR and 95% CI for OS and PFS were available directly or calculated using the Kaplan–Meier survival curves; and (4) specific drugs for chemotherapy were introduced.

Study selection was independently performed by two authors and disagreements were resolved through discussion. The following data were extracted: the author’s name, country, publication year, number of patients, treatment detail, outcomes (including HRs and 95% CIs), the Cox regression model, and study design feature.

The bias risk in each study was independently assessed by two authors using a modified domain-based Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for non-randomized studies. The assessment included selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias and reporting bias. Important prognostic variables, including age, neurologic status, extent of resection, tumor location, primary or recurrent GBM and MGMT promoter status, were added into NOS according to the Reporting Recommendations for Tumor Marker Prognostic Studies (REMARK) checklist for a tumor prognostic study (23, 24). The judgment criteria for the modified evaluation were explicitly described in Table S1 in Supplementary Material.

The statistical analysis was performed by STATA 12.0 software. HR and 95% CI were directly extracted or calculated using the Kaplan–Meier survival curves or the methods reported by Tierney et al. (25). To evaluate the association of MGMT promoter methylation with OS and PFS, pooled HRs of methylated GBM patients were compared to those of unmethylated patients. Subgroup analysis was performed to evaluate whether methylated patients benefit from different therapies (TMZ-containing, TMZ-free alkylating agents, or radiotherapy alone). The statistical heterogeneity among studies was assessed by Q-test and I2 statistics (26). If there was no obvious heterogeneity, fixed-effect model was used to estimate the pooled HR (27); otherwise, random-effect model was used (28). Bonferroni method was used for multiple comparison adjustments. Publication bias was assessed by funnel plots and Egger’s test (29), and a trim and fill method was applied to estimate asymmetry in funnel plots (30). Sensitivity analysis by deleting each enrolled study in turn was conducted to assess overall robustness of the meta-analysis results.

The flow chart of literature selection was presented in Figure 1. Totally, 3,181 articles were screened. Finally, a total of 7,886 patients in 66 studies (four articles comprising two individual trials were extracted as eight individual studies) were identified, including 7 randomized trials, 59 non-randomized trials. Of these 66 studies, 54 studies were related to TMZ-containing chemotherapy and 12 studies were related to TMZ-free treatment (4 studies of radiotherapy alone and 12 studies of TMZ-free alkylating agents chemotherapy). The characteristics of all studies are summarized in Table 1. Quality assessment showed no apparent variations among the studies in most domains of bias except for selection bias (see Table S1 in Supplementary Material).

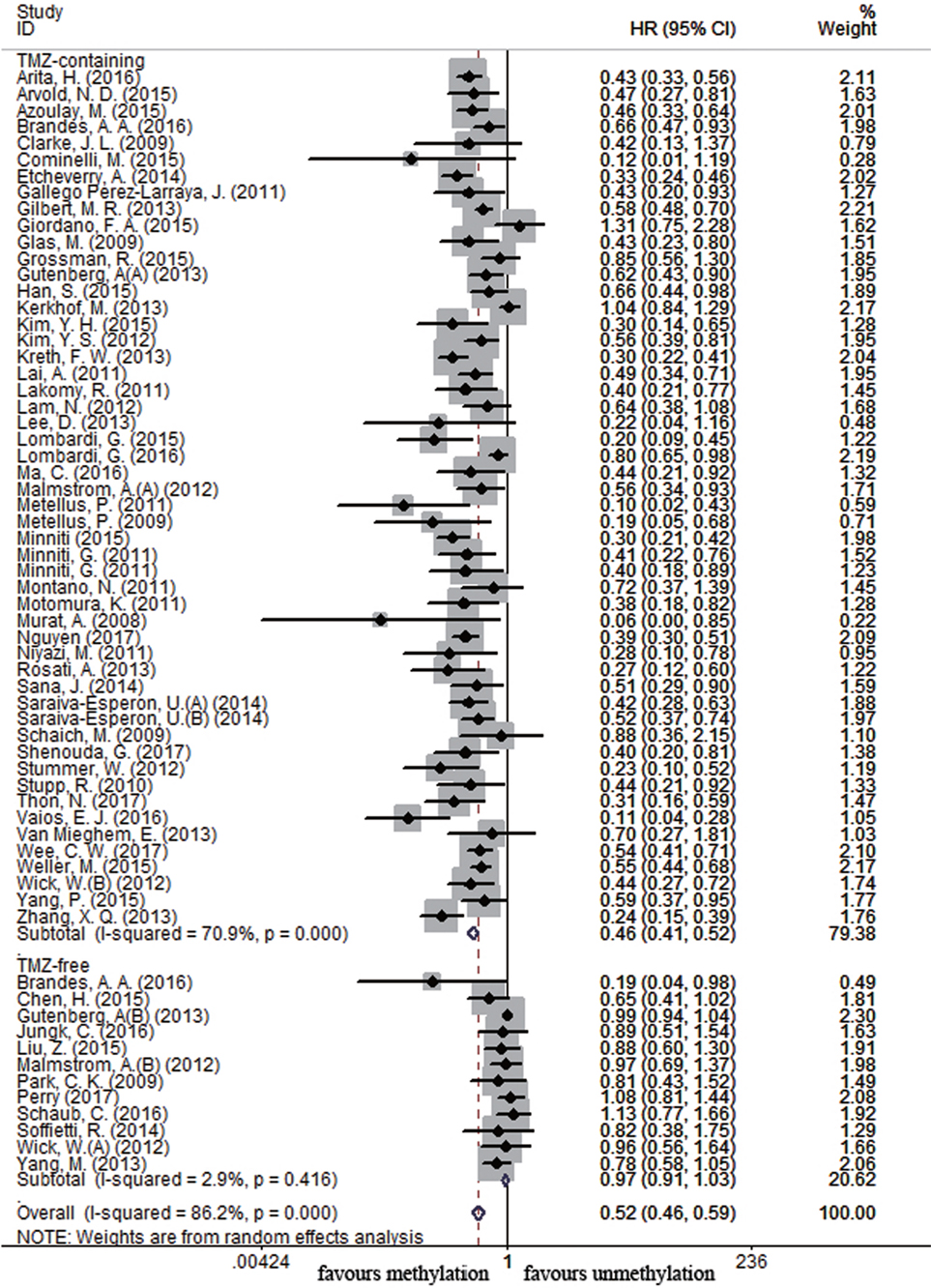

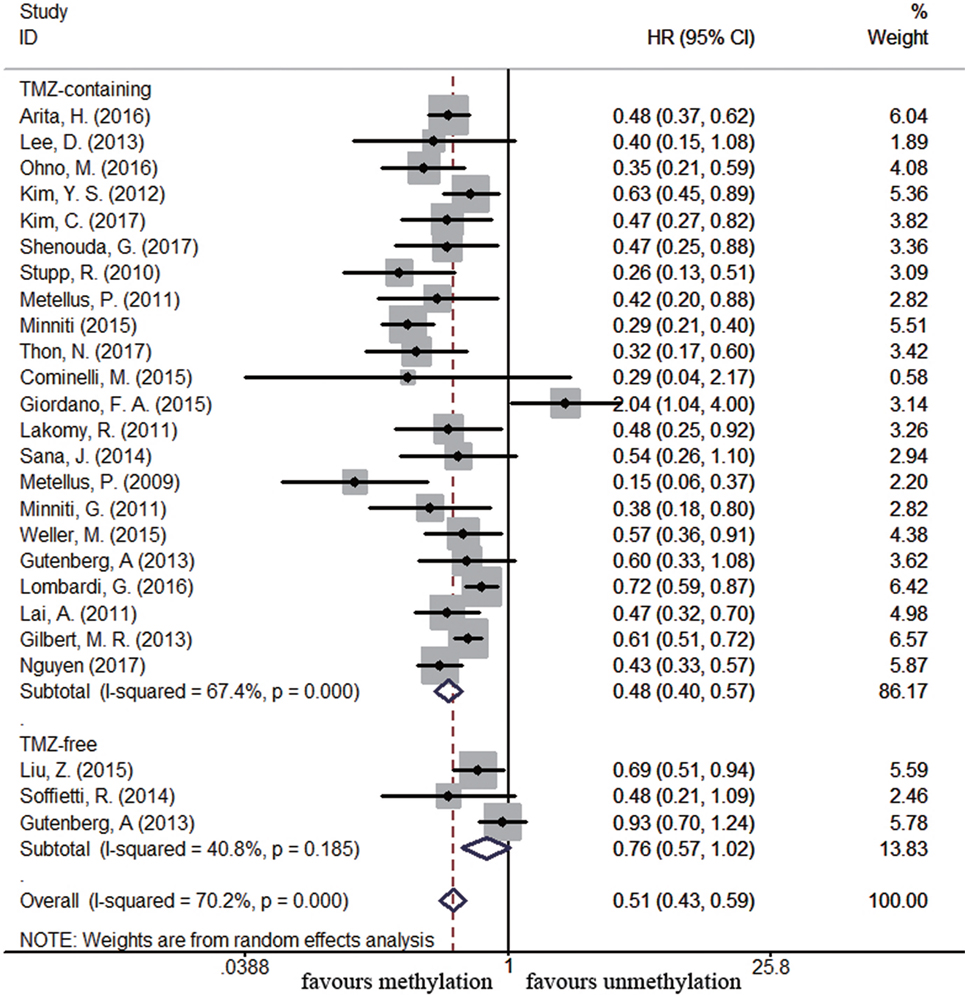

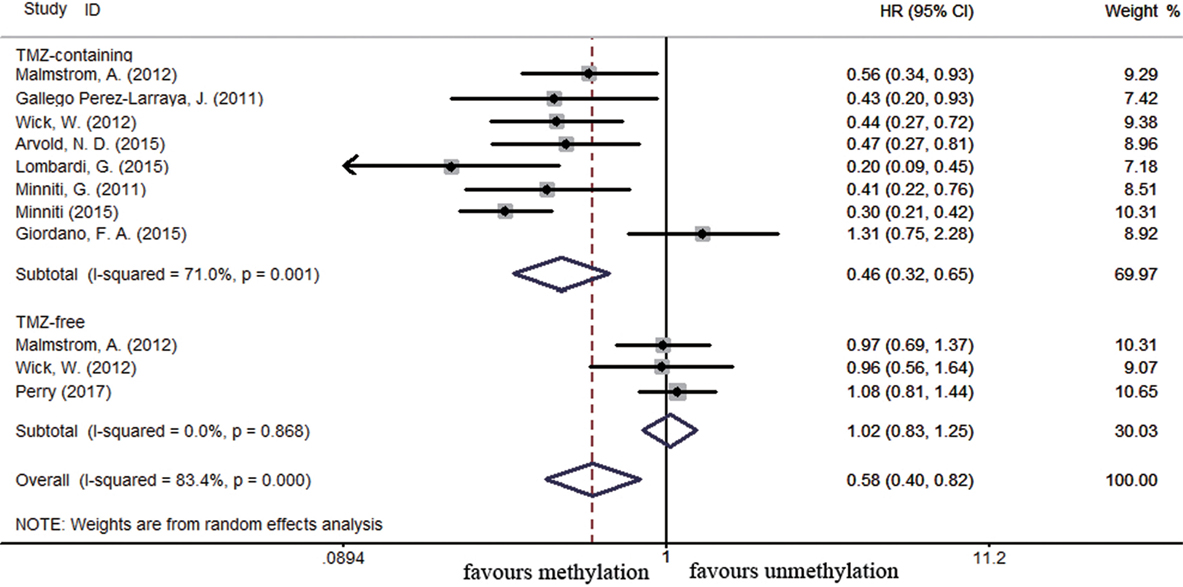

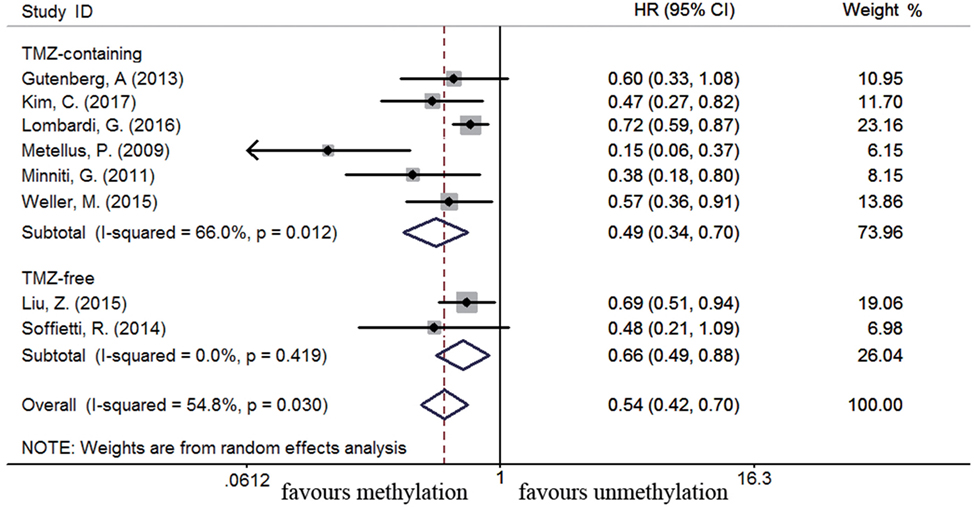

Sixty-four and 25 studies were included to describe the correlation of MGMT methylation status with OS and PFS in GBM patients, respectively. GBM patients with MGMT promoter methylation had significantly better OS and PFS than those with unmethylated status (OS: HR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.46–0.59, p < 0.001, I2 = 86.2%; PFS: HR = 0.51, 95% CI 0.43–0.59, p < 0.001, I2 = 70.2%; see Figure S1 in Supplementary Material), indicating the association between methylation and survival benefit in GBM patients. Next, subgroup analysis was conducted to evaluate whether methylated GBM patients could benefit from different therapies. The results of subgroup analysis were summarized in Table 2. Our analysis showed that, among patients exposed to TMZ-containing treatment, methylated patients had longer OS and PFS than unmethylated patients (OS: HR = 0.46, 95% CI 0.41–0.52, p < 0.001, Bon = 0.017, I2 = 70.9%, Figure 2; PFS: HR = 0.48, 95% CI 0.40–0.57, p < 0.001, Bon = 0.014, I2 = 67.4%, Figure 3). However, no significant OS benefit from TMZ-free treatment was observed in methylated patients by analysis of 12 studies (21, 35, 44, 58, 69, 70, 77, 84, 85) (HR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.91–1.03, p = 0.32, I2 = 2.9%, Figure 2). Further analysis showed that methylated patients derived no OS benefit from TMZ-free alkylating agents chemotherapy (HR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.93–1.03, p = 0.41, Bon = 1, I2 = 9.1%). Similarly, PFS was not significantly prolonged in methylated patients with TMZ-free alkylating agents chemotherapy (HR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.57–1.02, p = 0.40, Bon = 0.748, I2 = 40.8%, Figure 3). These results indicate that MGMT methylation is predictive for better response to TMZ therapy in GBM patients.

Figure 2. Calculated hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the relationship between methylation and overall survival benefit from temozolomide (TMZ)-containing or TMZ-free therapy in overall glioblastoma patients (methylated vs. unmethylated patients).

Figure 3. Calculated hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the relationship between methylation and progression-free survival benefit from temozolomide (TMZ)-containing or TMZ-free therapy in overall glioblastoma patients (methylated vs. unmethylated patients).

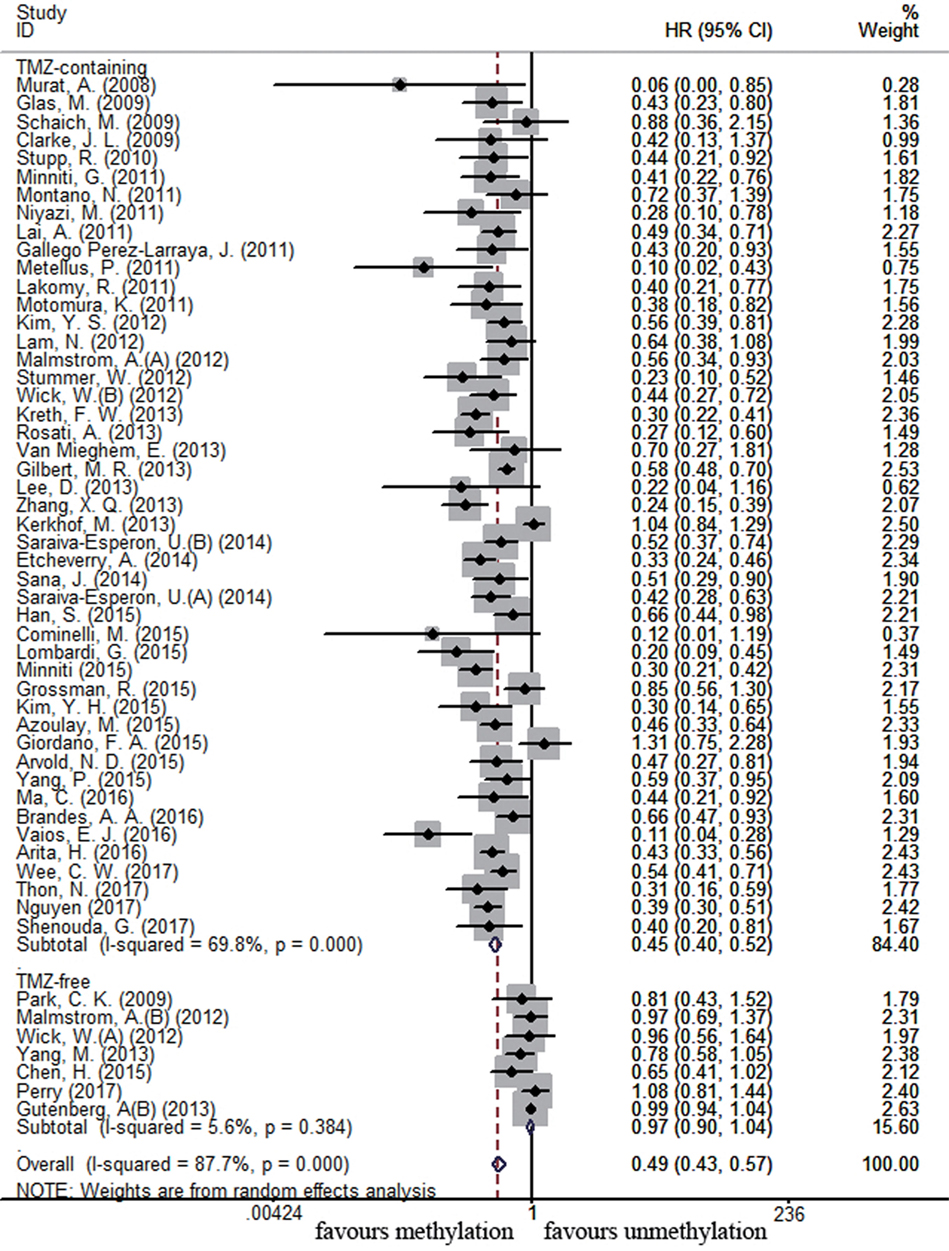

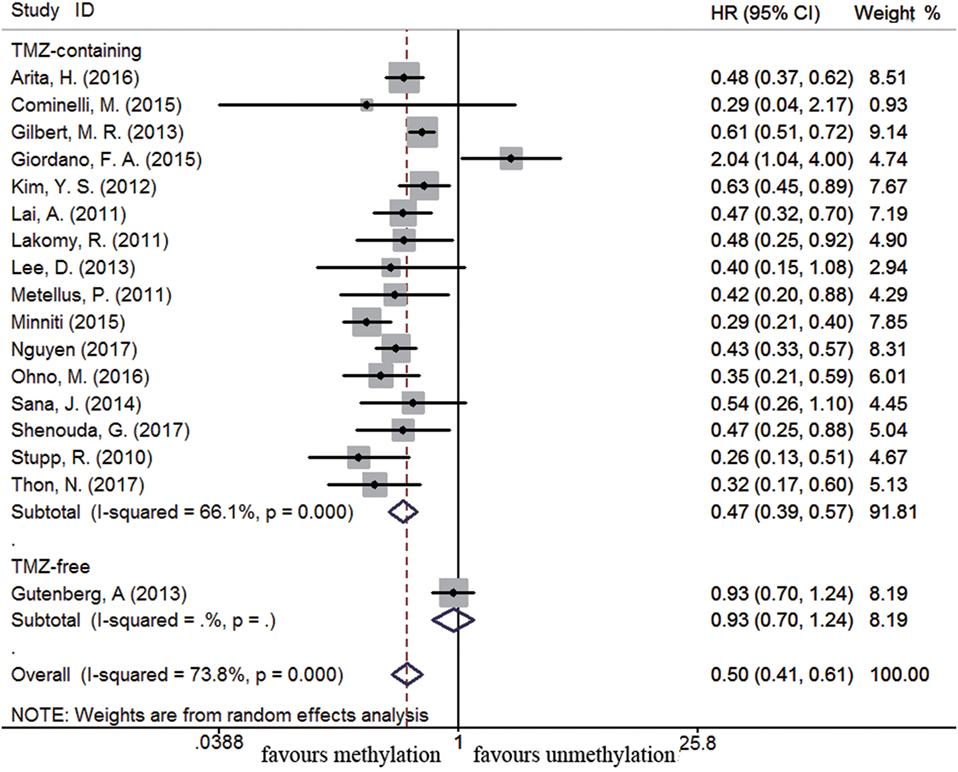

There were 54 and 17 studies recruited to assess the impact of MGMT promoter methylation on OS and PFS in newly diagnosed GBM patients, respectively. MGMT promoter methylation in newly diagnosed GBM patients was also associated with improved OS and PFS (OS: HR = 0.49, 95% CI 0.43–0.57, p < 0.001, I2 = 87.7%; PFS: HR = 0.50, 95% CI 0.41–0.61, p < 0.001, I2 = 73.8%, Figure S2 in Supplementary Material). Subgroup analysis showed that methylated patients receiving TMZ-containing treatment had better OS and PFS than unmethylated patients (OS: HR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.40–0.52, p < 0.001, Bon = 0.017, I2 = 69.8%, Figure 4; PFS: HR = 0.47, 95% CI 0.39–0.57, p < 0.001, Bon = 0.014, I2 = 66.1%, Figure 5). No significant advantage on OS and PFS was observed in methylated patients receiving TMZ-free treatment (OS: HR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.90–1.04, p = 0.37, Bon = 1, I2 = 5.6%, Figure 4; PFS: HR = 0.93, 95% CI 0.70–1.24, p = 0.62, Bon = 1, Figure 5). These observations were similar to those in overall GBM patients, indicating that the beneficial effect of methylation on OS in newly diagnosed patients was also TMZ therapy-dependent.

Figure 4. Calculated HRs and 95% CIs for the relationship between methylation and OS benefit from TMZ-containing or TMZ-free therapy in newly diagnosed GBM patients (methylated vs. unmethylated patients).

Figure 5. Calculated HRs and 95% CIs for the relationship between methylation and PFS benefit from TMZ-containing or TMZ-free therapy in newly diagnosed GBM patients (methylated vs. unmethylated patients).

Overall survival in elderly GBM patients was assessed on the basis of 11 studies comprising 1,321 patients. Among these studies, elderly was defined as 60 years or older (58), over 65 years old (32, 41, 55, 61, 70, 84), or 70 years or older (39, 62). A significant correlation between MGMT promoter methylation and better OS was observed in elderly GBM patients (HR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.40–0.82, p = 0.002, I2 = 83.4%, Figure S3 in Supplementary Material). A significant improvement on OS was also found in methylated elderly patients with TMZ-containing treatment compared to unmethylated patients with similar treatment (HR = 0.46, 95% CI 0.32–0.65, p < 0.001, Bon = 0.017, I2 = 71%, Figure 6). No significance benefit from TMZ-free treatment found in methylated elderly patients than unmethylated elderly patients (HR = 1.02, 95% CI 0.83–1.25, p = 0.83, Bon = 1, I2 = 0%, Figure 6).

Figure 6. Calculated HRs and 95% CIs for the relationship between methylation and OS benefit from TMZ-containing or TMZ-free therapy in elderly GBM patients (methylated vs. unmethylated patients).

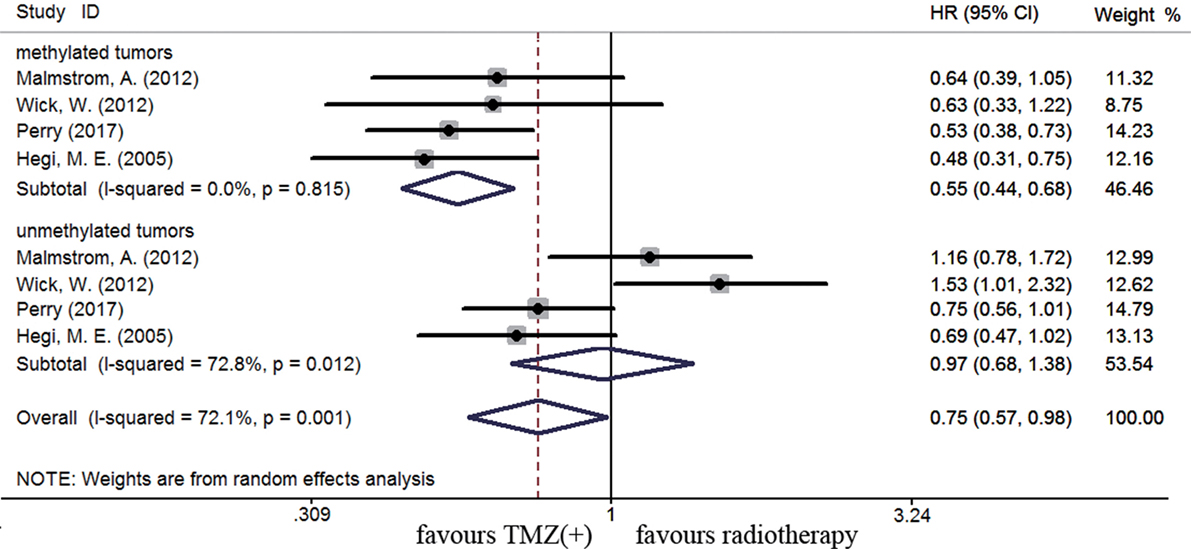

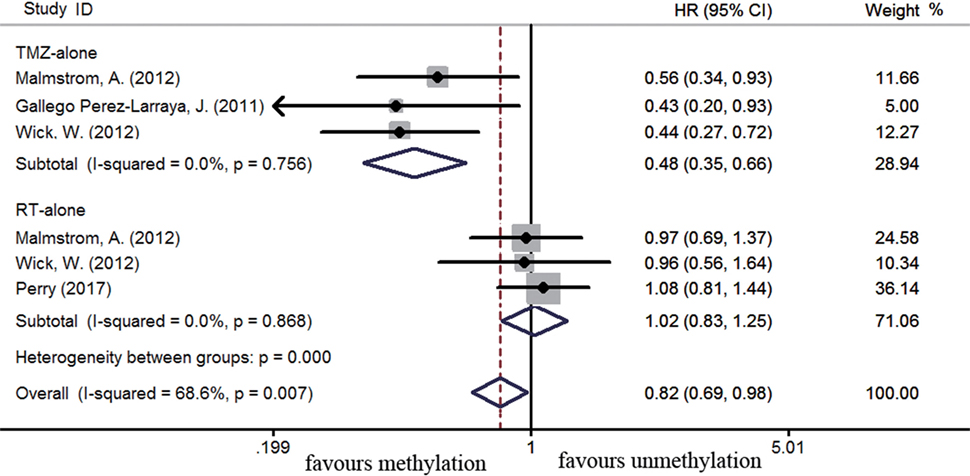

The efficacy of TMZ-containing therapy versus radiotherapy in elderly patients was assessed according to three randomized controlled trials (58, 70, 84). Methylated elderly patients with TMZ-containing treatment had better OS than those with radiotherapy alone (HR = 0.55, 95% CI 0.44–0.68, p < 0.001; I2 = 0%, Figure 7). However, the benefit of TMZ-containing therapy was not observed in elderly patients with unmethylated status (HR = 0.97, 95% CI 0.68–1.38, p < 0.001, I2 = 72.8%, Figure 7). Elderly patients were often unable to tolerate multimodality therapy, so we further assess whether elderly patients with MGMT methylation could benefit from TMZ alone or radiotherapy alone therapy. Compared to unmethylated elderly patients, prolonged OS was observed in methylated elderly patients receiving TMZ alone therapy but not in those receiving radiotherapy alone (TMZ alone: HR = 0.48, 95% CI 0.35–0.66, p < 0.001, I2 = 0%; Radiotherapy alone: HR = 1.02, 95% CI 0.83–1.25, p = 0.83, I2 = 0%, Figure 8). These results indicated the strong correlation between MGMT methylation and better response to TMZ therapy in elderly GBM patients.

Figure 7. Calculated HRs and 95% CIs for the relationship between methylation and OS benefit in elderly GBM patients (TMZ-containing therapy vs. radiotherapy alone).

Figure 8. Calculated HRs and 95% CIs for the relationship between methylation and OS benefit in elderly GBM patients exposed to TMZ alone or radiotherapy (RT) alone (methylated vs. unmethylated patients).

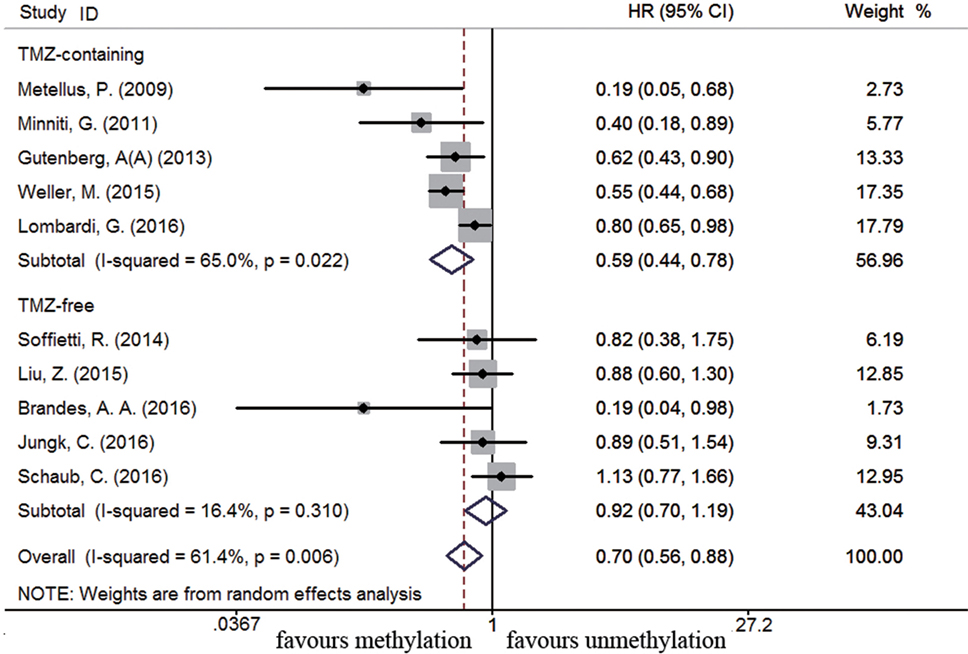

Eleven studies were included to analyze the association between MGMT promoter methylation and survival in recurrent GBM patients (19, 21, 22, 44, 46, 56, 60, 63, 75, 77, 89). A significant improvement on OS and PFS was observed in methylated recurrent patients (OS: HR = 0.70, 95% CI 0.56–0.88, p < 0.001, I2 = 61.4%; PFS: HR = 0.54, 95% CI 0.42–0.70, p < 0.001, I2 = 54.8%, Figure S4 in Supplementary Material). Subgroup analysis showed TMZ-containing therapy conferred a survival benefit in methylated recurrent patients (OS: HR = 0.59, 95% CI 0.44–0.78, p < 0.001, Bon = 0.017, I2 = 65%, Figure 9; PFS: HR = 0.49, 95% CI 0.34–0.70, p = 0.001, Bon = 0.014, I2 = 66%, Figure 10). In contrast, TMZ-free therapy did not improve OS (HR = 0.92, 95% CI 0.70–1.19, p = 0.52, Bon = 1, I2 = 16.4%, Figure 9) or PFS (HR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.49–0.88, p = 0.005, Bon = 0.065, I2 = 0%, Figure 10) in methylated recurrent patients.

Figure 9. Calculated HR and 95% CIs for the relationship between methylation and OS benefit from TMZ-containing or TMZ-free therapy in recurrent GBM patients (methylated vs. unmethylated patients).

Figure 10. Calculated HR and 95% CIs for the relationship between methylation and PFS benefit from TMZ-containing or TMZ-free therapy in recurrent GBM patients (methylated vs. unmethylated patients).

There were 42 studies for Caucasian (European, Canadian, Australian), 16 studies for Asian (Chinese, Japanese, Korean), and 8 studies for mixed race (American). Compared to unmethylated patients, both OS and PFS were improved in methylated patients (OS: Asian: HR = 0.54, 95% CI 0.44–0.65, p < 0.001, I2 = 61.1%; Caucasian: HR = 0.53, 95% CI 0.45–0.63, p < 0.001, I2 = 86.8%; Mixed race: HR = 0.48, 95% CI 0.38–0.62, p < 0.001, I2 = 67.7%; PFS: Asian: HR = 0.53, 95% CI 0.43–0.65, p < 0.001, I2 = 31.4%; Caucasian: HR = 0.49, 95% CI 0.37–0.65, p < 0.001, I2 = 77.8%; Mixed race: HR = 0.51, 95% CI 0.40–0.65, p < 0.001, I2 = 61%, Figure S5 in Supplementary Material). Among GBM patients with TMZ-containing treatment, MGMT methylation benefited to both Caucasian and Asian (Asian OS: HR = 0.48, 95% CI 0.42–0.54, p < 0.001, Bon = 0.017, I2 = 43.8%; PFS: HR = 0.49, 95% CI 0.41–0.59, p < 0.001, Bon = 0.014, I2 = 0%; Caucasian OS: HR = 0.46, 95% CI 0.39–0.55, p < 0.001, Bon = 0.017, I2 = 75.5%; PFS: HR = 0.46, 95% CI 0.34–0.63, p < 0.001, Bon = 0.014, I2 = 76.2%, Figure S6 in Supplementary Material). Among patients receiving TMZ-free treatment, survival benefit in Asian patients was not observed anymore after Bonferroni correction (Asian OS: HR = 0.78, 95% CI 0.64–0.95, p = 0.02, Bon = 0.24, I2 = 0%; PFS: HR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.50–0.94, p = 0.02, Bon = 0.24, Figure S6 in Supplementary Material). No benefit was observed in Caucasian receiving TMZ-free therapy regardless of Bonferroni adjustment. The impact of MGMT promoter methylation in mixed race was not evaluated since data in TMZ-free group was not available.

Publication bias was evaluated by Egger’s test. Publication bias was observed in OS and PFS analysis in overall GBM patients (OS: p < 0.001; PFS: p = 0.04). More results were presented in Table 2. Therefore, we performed the trim and fill analysis to estimate the publication bias. However, those results remain unchanged after introducing the trim and fill method to correct the publication bias.

Sensitivity analysis was conducted by sequentially omitting individual studies to assess whether a single study might significantly affect the overall results. Sensitivity analysis showed one study (41) predominantly contributed to heterogeneity in elderly GBM subpopulation, especially in TMZ-containing group (Figure S7 in Supplementary Material). Further sensitivity analysis revealed that other results did not show any apparent variations in pooled HRs for OS or PFS, supporting the robustness of the primary findings.

Although MGMT has been widely established as a clinically relevant biomarker in GBM patients, its clinical implication has not been definitely confirmed. A prognostic factor is a clinical or biologic characteristic that is objectively measured and provides information on likely outcome of the cancer disease independent of treatment, while a predictive factor is a clinical or biologic characteristic providing information on likely benefits from one specific treatment rather than another (90). Which one is more appropriate to describe the relationship between MGMT promoter methylation and GBM prognosis? Among overall GBM patients, MGMT methylation conferred a survival benefit to patients with TMZ-containing treatment, but not to those with TMZ-free treatment. It seems that MGMT methylation has a predictive value for GBM patients exposed to TMZ-containing treatment. However, considering the differentiation of prognostic variables among patients, including primary or recurrent GBM, age and race, the universality of predictive value of MGMT methylation in different GBM subgroups should be profoundly validated. Therefore, we further assess its clinical significance in newly diagnosed patients, recurrent patients, elderly patients, and Asian and Caucasian patients.

In newly diagnosed and recurrent GBM patients, MGMT methylation was associated with improved OS and PFS with TMZ-containing treatment, but not in those with TMZ-free treatment. Then MGMT methylation is predictive for a benefit from TMZ–containing chemotherapy in newly diagnosed and recurrent patients.

In elderly GBM patients, MGMT methylation also conferred an OS benefit in patients with TMZ-containing treatment, but not in those with TMZ-free treatment. Therefore, MGMT methylation in elderly patients is likely to have a similar predictive value as in newly diagnosed and recurrent GBM patients. Elderly GBM patients are often clinically unable to tolerate multimodality therapy, thus TMZ or radiotherapy alone is commonly used. This meta-analysis showed that elderly patients with methylated status exposed to TMZ alone had improved OS than those exposed to radiotherapy alone, while such difference was not observed in those with unmethylated status. Our results highlight that TMZ alone therapy might be a more effective option than radiotherapy alone therapy for elderly GBM patients with methylated MGMT status. But the optimal radiotherapy regimen for elderly and/or frail patients with newly diagnosed GBM remains to be defined (91). A recent study showed that short-course radiation (40 Gy in 15 fractions) plus TMZ conferred a survival advantage over radiotherapy alone in elderly patients (65 years of age or older) with newly diagnosed GBM, especially in those with methylated MGMT status (70). Due to the lack of a uniform definition for elderly, different cutoff age was employed in different studies. Patients aged more than 70 years were excluded from Stupp study (87). In this meta-analysis, patients aged 60 or more were enrolled for analysis. Our results showed that patients aged over 70 years with MGMT methylation also benefit from TMZ-containing therapy. The definition of cutoff age for the elderly are closely linked to prognosis, therapeutic goals, or patterns of care, so further research in this field should standardize the cutoff age for enrollment eligibility (92).

Another interesting issue is the clinical value of MGMT methylation in Asian and Caucasian patients. A previous study showed that MGMT methylation correlated with better OS and PFS in Caucasian patients and only better OS in Asian patients regardless of therapeutic intervention (93). But the benefit of different therapies in methylated patients was not investigated in the study. In our analysis, survival benefit in Asian patients with TMZ-free treatment was not observed anymore after Bonferroni adjustment. Bonferroni correction can avoid false positives, and then the risk of false negatives would be increased. So the finding in Asian patients should be cautiously interpreted. It must be noted that only four studies (519 patients) for OS and a single study (137 patients) for PFS were enrolled for this subgroup analysis. Therefore, our finding on patients with different races needs to be further verified by more clinical studies. Furthermore, recent studies also give a hint about the different regulation of MGMT methylation in different ethnic background. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs16906252) in MGMT promoter-enhancer is a key determinant in the acquisition of MGMT methylation (94). The genotype of rs16906252 varies among different ethnic groups (95), which may result in different MGMT methylation status. In addition to promoter methylation, other molecules are also involved in regulation of MGMT expression or function. For example, miR-181d can bind to the 3′untranslated region of MGMT transcripts, then decrease its mRNA stability and/or reduce protein translation (96). Further studies on ethnically genetic variations are necessary.

Due to the limited number of trials recruited for analysis, the presented information about PFS in patients with TMZ-free treatment, especially in newly diagnosed and recurrent subgroups, should be interpreted carefully. It should be acknowledged that we did not obtain any data of PFS in elderly patients exposed to TMZ-free treatment. Therefore, the predictive or prognostic value of this biomarker for PFS is far from identified in our analysis. In fact, clinical measurement of PFS may be a critical challenge in GBM trials. It is well known that GBM patients suffer inevitably recurrence despite integrated therapy (97). Pseudoprogression, also denoted as radiotherapy-introduced necrosis, exhibits contrast enhancement similar to early tumor progression on magnetic resonance imaging. Primary GBM patients receiving concurrent and adjuvant TMZ-based chemoradiotherapy have a high likelihood of developing pseudoprogression (98, 99), which occurs mainly within 3 months after completion of chemoradiotherapy. However, no technique has been proven to reliably differentiate between tumor recurrence and pseudoprogression. Additionally, both entities might coexist in the same patient at the same time in different areas of the tumor. The misdiagnosis of pseudoprogression as tumor recurrence may lead to a record of shorter PFS. Interestingly, MGMT promoter methylation was associated with a high incidence of pseudoprogression in newly diagnosed GBM patients undergoing TMZ-based chemoradiotherapy (100). In addition, GBM patients with the occurrence of pseudoprogression had a longer OS than those without pseudoprogression (98, 101), indicating that pseudoprogression may be a predictor for better response to therapy. Therefore, it is critically important to develop imaging techniques and biomarkers to discriminate pseudoprogression from early progression.

We also noticed the methodological diversity of measurement of MGMT promoter methylation. MGMT promoter methylation was detected by methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction (MSP), pyrosequencing, and methylation-sensitive high-resolution melting (MS-HRM) in 48, 6, and 2 studies, respectively. Additionally, various cutoff values for methylated positivity were used in these studies. However, there were few studies that have compared the merits and disadvantages of these MGMT testing methods (17). Further efforts should standardize the MGMT methylation testing methods and cutoff point.

Limitations of this study should be acknowledged. Firstly, heterogeneity existed in the pooled analysis for PFS and OS either in overall population or in subgroup analysis. Heterogeneity may result from different techniques of defining MGMT promoter status and varied therapy schedule. Different chemotherapy and radiotherapy schedules may influence the prognosis of GBM patients, thus analysis of the correlation between a single treatment schedule and MGMT promoter status was not conducted in this meta-analysis. Second, considering the scarce number of multivariate studies in some of subgroup analysis, univariate studies were also included in our analysis. We also performed analysis using only multivariate studies and similar findings were observed (Table S3 in Supplementary Material). Third, due to the limited number of original documents on PFS, there was not enough power to identify the impact of MGMT methylation on PFS, especially in patients receiving TMZ-free therapy. Fourth, quality assessment was performed by a modified domain-based NOS (102, 103), which was proposed as a potential helpful and practically method for assessment of tumor prognostic studies. However, this novel NOS has not been fully validated and results should be interpreted with caution. Fifth, Egger’s test showed that publication bias existed in pooled analysis for OS, but the trim and fill analysis upheld the reliability of our results.

In conclusion, our results highlight the universal predictive value of MGMT methylation in newly diagnosed GBM patients, elderly GBM patients and recurrent GBM patients. For elderly methylated GBM patients, TMZ alone therapy might be a more suitable option than radiotherapy alone therapy. This study may be helpful to optimize therapeutics in different GBM subpopulation.

Y-HZ and C-JC contributed to the conception of the experiments and manuscript preparation. Y-HZ, C-SX, X-TZ, J-LL, JL, and KL contributed to data research and review. Y-HZ and HW performed data analysis. Z-FW and Z-QL contributed to interpretation and discussion of the results.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewers CS, BW and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation.

This research was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81573459). We acknowledge Dr. Yi Guo from Wuhan University for reviewing the statistical analysis in this manuscript.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2018.00127/full#supplementary-material.

1. Trivedi RN, Almeida KH, Fornsaglio JL, Schamus S, Sobol RW. The role of base excision repair in the sensitivity and resistance to temozolomide-mediated cell death. Cancer Res (2005) 65(14):6394–400. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-05-0715

2. Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, et al. Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol (2009) 10(5):459–66. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70025-7

3. Stupp R, Wong ET, Kanner AA, Steinberg D, Engelhard H, Heidecke V, et al. NovoTTF-100A versus physician’s choice chemotherapy in recurrent glioblastoma: a randomised phase III trial of a novel treatment modality. Eur J Cancer (2012) 48(14):2192–202. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2012.04.011

4. Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med (2008) 359(5):492–507. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0708126

5. Laperriere N, Weller M, Stupp R, Perry JR, Brandes AA, Wick W, et al. Optimal management of elderly patients with glioblastoma. Cancer Treat Rev (2013) 39(4):350–7. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.05.008

6. Vlassenbroeck I, Califice S, Diserens AC, Migliavacca E, Straub J, Di Stefano I, et al. Validation of real-time methylation-specific PCR to determine O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase gene promoter methylation in glioma. J Mol Diagn (2008) 10(4):332–7. doi:10.2353/jmoldx.2008.070169

7. Vlachostergios PJ, Hatzidaki E, Befani CD, Liakos P, Papandreou CN. Bortezomib overcomes MGMT-related resistance of glioblastoma cell lines to temozolomide in a schedule-dependent manner. Invest New Drugs (2013) 31(5):1169–81. doi:10.1007/s10637-013-9968-1

8. Hotta T, Saito Y, Fujita H, Mikami T, Kurisu K, Kiya K, et al. O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase activity of human malignant glioma and its clinical implications. J Neurooncol (1994) 21(2):135–40. doi:10.1007/BF01052897

9. Belanich M, Pastor M, Randall T, Guerra D, Kibitel J, Alas L, et al. Retrospective study of the correlation between the DNA repair protein alkyltransferase and survival of brain tumor patients treated with carmustine. Cancer Res (1996) 56(4):783–8.

10. Jaeckle KA, Eyre HJ, Townsend JJ, Schulman S, Knudson HM, Belanich M, et al. Correlation of tumor O6 methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase levels with survival of malignant astrocytoma patients treated with bis-chloroethylnitrosourea: a Southwest Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol (1998) 16(10):3310–5. doi:10.1200/jco.1998.16.10.3310

11. Newlands ES, Stevens MF, Wedge SR, Wheelhouse RT, Brock C. Temozolomide: a review of its discovery, chemical properties, pre-clinical development and clinical trials. Cancer Treat Rev (1997) 23(1):35–61. doi:10.1016/S0305-7372(97)90019-0

12. Stupp R, Gander M, Leyvraz S, Newlands E. Current and future developments in the use of temozolomide for the treatment of brain tumours. Lancet Oncol (2001) 2(9):552–60. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(01)00489-2

13. Chinot OL, Barrie M, Fuentes S, Eudes N, Lancelot S, Metellus P, et al. Correlation between O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase and survival in inoperable newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients treated with neoadjuvant temozolomide. J Clin Oncol (2007) 25(12):1470–5. doi:10.1200/jco.2006.07.4807

14. Eoli M, Menghi F, Bruzzone MG, De Simone T, Valletta L, Pollo B, et al. Methylation of O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase and loss of heterozygosity on 19q and/or 17p are overlapping features of secondary glioblastomas with prolonged survival. Clin Cancer Res (2007) 13(9):2606–13. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-06-2184

15. Hegi ME, Liu L, Herman JG, Stupp R, Wick W, Weller M, et al. Correlation of O6-methylguanine methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation with clinical outcomes in glioblastoma and clinical strategies to modulate MGMT activity. J Clin Oncol (2008) 26(25):4189–99. doi:10.1200/jco.2007.11.5964

16. Gorlia T, van den Bent MJ, Hegi ME, Mirimanoff RO, Weller M, Cairncross JG, et al. Nomograms for predicting survival of patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: prognostic factor analysis of EORTC and NCIC trial 26981-22981/CE.3. Lancet Oncol (2008) 9(1):29–38. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(07)70384-4

17. Weller M, Stupp R, Reifenberger G, Brandes AA, van den Bent MJ, Wick W, et al. MGMT promoter methylation in malignant gliomas: ready for personalized medicine? Nat Rev Neurol (2010) 6(1):39–51. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2009.197

18. Lechapt-Zalcman E, Levallet G, Dugue AE, Vital A, Diebold MD, Menei P, et al. O(6)-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter methylation and low MGMT-encoded protein expression as prognostic markers in glioblastoma patients treated with biodegradable carmustine wafer implants after initial surgery followed by radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide. Cancer (2012) 118(18):4545–54. doi:10.1002/cncr.27441

19. Weller M, Tabatabai G, Kästner B, Felsberg J, Steinbach JP, Wick A, et al. MGMT promoter methylation is a strong prognostic biomarker for benefit from dose-intensified temozolomide rechallenge in progressive glioblastoma: the DIRECTOR trial. Clin Cancer Res (2015) 21(9):2057–64. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2737

20. Dahlrot RH, Dowsett J, Fosmark S, Malmstrom A, Henriksson R, Boldt H, et al. Prognostic value of O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) protein expression in glioblastoma excluding nontumour cells from the analysis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol (2018) 44(2):172–84. doi:10.1111/nan.12415

21. Liu Z, Zhang G, Zhu L, Wang J, Liu D, Lian L, et al. Retrospective analysis of bevacizumab in combination with fotemustine in Chinese patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Biomed Res Int (2015) 2015:723612. doi:10.1155/2015/723612

22. Brandes AA, Finocchiaro G, Zagonel V, Reni M, Caserta C, Fabi A, et al. AVAREG: a phase II, randomized, noncomparative study of fotemustine or bevacizumab for patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol (2016) 18(9):1304–12. doi:10.1093/neuonc/now035

23. Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons (2011).

24. Altman DG, McShane LM, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK): explanation and elaboration. BMC Med (2012) 10(1):51. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-10-51

25. Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. (2007) 8:16. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-8-16

26. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med (2002) 21(11):1539–58. doi:10.1002/sim.1186

27. Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst (1959) 22(4):719–48.

28. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials (1986) 7:177–88. doi:10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2

29. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics (1994) 50:1088–101. doi:10.2307/2533446

30. Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics (2000) 56(2):455–63. doi:10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x

31. Arita H, Yamasaki K, Matsushita Y, Nakamura T, Shimokawa A, Takami H, et al. A combination of TERT promoter mutation and MGMT methylation status predicts clinically relevant subgroups of newly diagnosed glioblastomas. Acta Neuropathol Commun (2016) 4(1):79. doi:10.1186/s40478-016-0351-2

32. Arvold ND, Tanguturi SK, Aizer AA, Wen PY, Reardon DA, Lee EQ, et al. Hypofractionated versus standard radiation therapy with or without temozolomide for older glioblastoma patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys (2015) 92(2):384–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.01.017

33. Azoulay M, Santos F, Souhami L, Panet-Raymond V, Petrecca K, Owen S, et al. Comparison of radiation regimens in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme: results from a single institution. Radiat Oncol (2015) 10(1):106. doi:10.1186/s13014-015-0396-6

34. Brandes AA, Bartolotti M, Tosoni A, Poggi R, Bartolini S, Paccapelo A, et al. Patient outcomes following second surgery for recurrent glioblastoma. Future Oncol (2016) 12(8):1039–44. doi:10.2217/fon.16.9

35. Chen H, Li X, Li W, Zheng H. miR-130a can predict response to temozolomide in patients with glioblastoma multiforme, independently of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase. J Transl Med (2015) 13(1):1. doi:10.1186/s12967-015-0435-y

36. Clarke JL, Iwamoto FM, Sul J, Panageas K, Lassman AB, DeAngelis LM, et al. Randomized phase II trial of chemoradiotherapy followed by either dose-dense or metronomic temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol (2009) 27(23):3861–7. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.20.7944

37. Cominelli M, Grisanti S, Mazzoleni S, Branca C, Buttolo L, Furlan D, et al. EGFR amplified and overexpressing glioblastomas and association with better response to adjuvant metronomic temozolomide. J Natl Cancer Inst (2015) 107(5):djv041. doi:10.1093/jnci/djv041

38. Etcheverry A, Aubry M, Idbaih A, Vauleon E, Marie Y, Menei P, et al. DGKI methylation status modulates the prognostic value of MGMT in glioblastoma patients treated with combined radio-chemotherapy with temozolomide. PLoS One (2014) 9(9):e104455. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104455

39. Gallego Perez-Larraya J, Ducray F, Chinot O, Catry-Thomas I, Taillandier L, Guillamo JS, et al. Temozolomide in elderly patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma and poor performance status: an ANOCEF phase II trial. J Clin Oncol (2011) 29(22):3050–5. doi:10.1200/jco.2011.34.8086

40. Gilbert MR, Wang M, Aldape KD, Stupp R, Hegi ME, Jaeckle KA, et al. Dose-dense temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma: a randomized phase III clinical trial. J Clin Oncol (2013) 31(32):4085–91. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6968

41. Welzel G, Gehweiler J, Brehmer S, Appelt JU, von Deimling A, Seiz-Rosenhagen M, et al. Metronomic chemotherapy with daily low-dose temozolomide and celecoxib in elderly patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme: a retrospective analysis. J Neurooncol (2015) 124(2):265–73. doi:10.1007/s11060-015-1834-x

42. Glas M, Happold C, Rieger J, Wiewrodt D, Bahr O, Steinbach JP, et al. Long-term survival of patients with glioblastoma treated with radiotherapy and lomustine plus temozolomide. J Clin Oncol (2009) 27(8):1257–61. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.19.2195

43. Grossman R, Burger P, Soudry E, Tyler B, Chaichana KL, Weingart J, et al. MGMT inactivation and clinical response in newly diagnosed GBM patients treated with Gliadel. J Clin Neurosci (2015) 22(12):1938–42. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2015.07.003

44. Gutenberg A, Bock H, Brück W, Doerner L, Mehdorn H, Roggendorf W, et al. MGMT promoter methylation status and prognosis of patients with primary or recurrent glioblastoma treated with carmustine wafers. Br J Neurosurg (2013) 27(6):772–8. doi:10.3109/02688697.2013.791664

45. Han S, Liu Y, Li Q, Li Z, Hou H, Wu A. Pre-treatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is associated with neutrophil and T-cell infiltration and predicts clinical outcome in patients with glioblastoma. BMC Cancer (2015) 15(1):617. doi:10.1186/s12885-015-1629-7

46. Jungk C, Chatziaslanidou D, Ahmadi R, Capper D, Bermejo JL, Exner J, et al. Chemotherapy with BCNU in recurrent glioma: analysis of clinical outcome and side effects in chemotherapy-naive patients. BMC Cancer (2016) 16:81. doi:10.1186/s12885-016-2131-6

47. Kerkhof M, Dielemans J, Van Breemen M, Zwinkels H, Walchenbach R, Taphoorn M, et al. Effect of valproic acid on seizure control and on survival in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro Oncol (2013) 80(7):961–7. doi:10.1093/neuonc/not057

48. Kim YH, Kim T, Joo JD, Han JH, Kim YJ, Kim IA, et al. Survival benefit of levetiracetam in patients treated with concomitant chemoradiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy with temozolomide for glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer (2015) 121(17):2926–32. doi:10.1002/cncr.29439

49. Kim YS, Kim SH, Cho J, Kim JW, Chang JH, Kim DS, et al. MGMT gene promoter methylation as a potent prognostic factor in glioblastoma treated with temozolomide-based chemoradiotherapy: a single-institution study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys (2012) 84(3):661–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.12.086

50. Kreth FW, Thon N, Simon M, Westphal M, Schackert G, Nikkhah G, et al. Gross total but not incomplete resection of glioblastoma prolongs survival in the era of radiochemotherapy. Ann Oncol (2013) 24(12):3117–23. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdt388

51. Lai A, Tran A, Nghiemphu PL, Pope WB, Solis OE, Selch M, et al. Phase II study of bevacizumab plus temozolomide during and after radiation therapy for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol (2011) 29(2):142–8. doi:10.1200/jco.2010.30.2729

52. Lakomy R, Sana J, Hankeova S, Fadrus P, Kren L, Lzicarova E, et al. MiR-195, miR-196b, miR-181c, miR-21 expression levels and O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase methylation status are associated with clinical outcome in glioblastoma patients. Cancer Sci (2011) 102(12):2186–90. doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02092.x

53. Lam N, Chambers CR. Temozolomide plus radiotherapy for glioblastoma in a Canadian province: efficacy versus effectiveness and the impact of O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase promoter methylation. J Oncol Pharm Pract (2012) 18(2):229–38. doi:10.1177/1078155211426198

54. Lee D, Suh YL, Park TI, Do IG, Seol HJ, Nam DH, et al. Prognostic significance of tetraspanin CD151 in newly diagnosed glioblastomas. J Surg Oncol (2013) 107(6):646–52. doi:10.1002/jso.23249

55. Lombardi G, Pace A, Pasqualetti F, Rizzato S, Faedi M, Anghileri E, et al. Predictors of survival and effect of short (40 Gy) or standard-course (60 Gy) irradiation plus concomitant temozolomide in elderly patients with glioblastoma: a multicenter retrospective study of AINO (Italian Association of Neuro-Oncology). J Neurooncol (2015) 125(2):359–67. doi:10.1007/s11060-015-1923-x

56. Lombardi G, Bellu L, Pambuku A, Della Puppa A, Fiduccia P, Farina M, et al. Clinical outcome of an alternative fotemustine schedule in elderly patients with recurrent glioblastoma: a mono-institutional retrospective study. J Neurooncol (2016) 128(3):481–6. doi:10.1007/s11060-016-2136-7

57. Ma C, Zhou W, Yan Z, Qu M, Bu X. β-elemene treatment of glioblastoma: a single-center retrospective study. Onco Targets Ther (2016) 9:7521–6. doi:10.2147/OTT.S120854

58. Malmström A, Grønberg BH, Marosi C, Stupp R, Frappaz D, Schultz H, et al. Temozolomide versus standard 6-week radiotherapy versus hypofractionated radiotherapy in patients older than 60 years with glioblastoma: the Nordic randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol (2012) 13(9):916–26. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70265-6

59. Metellus P, Nanni-Metellus I, Delfino C, Colin C, Tchogandjian A, Coulibaly B, et al. Prognostic impact of CD133 mRNA expression in 48 glioblastoma patients treated with concomitant radiochemotherapy: a prospective patient cohort at a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol (2011) 18(10):2937–45. doi:10.1245/s10434-011-1703-6

60. Metellus P, Coulibaly B, Nanni I, Fina F, Eudes N, Giorgi R, et al. Prognostic impact of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase silencing in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme who undergo surgery and carmustine wafer implantation: a prospective patient cohort. Cancer (2009) 115(20):4783–94. doi:10.1002/cncr.24546

61. Minniti G, Scaringi C, Lanzetta G, Terrenato I, Esposito V, Arcella A, et al. Standard (60 Gy) or short-course (40 Gy) irradiation plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for elderly patients with glioblastoma: a propensity-matched analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys (2015) 91(1):109–15. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.09.013

62. Minniti G, Salvati M, Arcella A, Buttarelli F, D’Elia A, Lanzetta G, et al. Correlation between O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase and survival in elderly patients with glioblastoma treated with radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide. J Neurooncol (2011) 102(2):311–6. doi:10.1007/s11060-010-0324-4

63. Minniti G, Armosini V, Salvati M, Lanzetta G, Caporello P, Mei M, et al. Fractionated stereotactic reirradiation and concurrent temozolomide in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. J Neurooncol (2011) 103(3):683–91. doi:10.1007/s11060-010-0446-8

64. Montano N, Cenci T, Martini M, D’Alessandris QG, Pelacchi F, Ricci-Vitiani L, et al. Expression of EGFRvIII in glioblastoma: prognostic significance revisited. Neoplasia (2011) 13(12):1113–21. doi:10.1593/neo.111338

65. Motomura K, Natsume A, Kishida Y, Higashi H, Kondo Y, Nakasu Y, et al. Benefits of interferon-beta and temozolomide combination therapy for newly diagnosed primary glioblastoma with the unmethylated MGMT promoter: a multicenter study. Cancer (2011) 117(8):1721–30. doi:10.1002/cncr.25637

66. Murat A, Migliavacca E, Gorlia T, Lambiv WL, Shay T, Hamou MF, et al. Stem cell-related “self-renewal” signature and high epidermal growth factor receptor expression associated with resistance to concomitant chemoradiotherapy in glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol (2008) 26(18):3015–24. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.15.7164

67. Nguyen HN, Lie A, Li T, Chowdhury R, Liu F, Ozer B, et al. Human TERT promoter mutation enables survival advantage from MGMT promoter methylation in IDH1 wild-type primary glioblastoma treated by standard chemoradiotherapy. Neuro Oncol (2017) 19(3):394–404. doi:10.1093/neuonc/now189

68. Niyazi M, Zehentmayr F, Niemöller OM, Eigenbrod S, Kretzschmar H, Osthoff KS, et al. MiRNA expression patterns predict survival in glioblastoma. Radiat Oncol (2011) 6(1):153. doi:10.1186/1748-717X-6-153

69. Park CK, Park SH, Lee SH, Kim CY, Kim DW, Paek SH, et al. Methylation status of the MGMT gene promoter fails to predict the clinical outcome of glioblastoma patients treated with ACNU plus cisplatin. Neuropathology (2009) 29(4):443–9. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1789.2008.00998.x

70. Perry JR, Laperriere N, O’Callaghan CJ, Brandes AA, Menten J, Phillips C, et al. Short-course radiation plus temozolomide in elderly patients with glioblastoma. N Engl J Med (2017) 376(11):1027–37. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1611977

71. Rosati A, Poliani PL, Todeschini A, Cominelli M, Medicina D, Cenzato M, et al. Glutamine synthetase expression as a valuable marker of epilepsy and longer survival in newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro Oncol (2013) 15(5):618–25. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nos338

72. Sana J, Radova L, Lakomy R, Kren L, Fadrus P, Smrcka M, et al. Risk score based on microRNA expression signature is independent prognostic classifier of glioblastoma patients. Carcinogenesis (2014) 35(12):2756–62. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgu212

73. Saraiva-Esperon U, Ruibal A, Herranz M. The contrasting epigenetic role of RUNX3 when compared with that of MGMT and TIMP3 in glioblastoma multiforme clinical outcomes. J Neurol Sci (2014) 347(1–2):325–31. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2014.10.043

74. Schaich M, Kestel L, Pfirrmann M, Robel K, Illmer T, Kramer M, et al. A MDR1 (ABCB1) gene single nucleotide polymorphism predicts outcome of temozolomide treatment in glioblastoma patients. Ann Oncol (2009) 20(1):175–81. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdn548

75. Schaub C, Tichy J, Schafer N, Franz K, Mack F, Mittelbronn M, et al. Prognostic factors in recurrent glioblastoma patients treated with bevacizumab. J Neurooncol (2016) 129(1):93–100. doi:10.1007/s11060-016-2144-7

76. Shenouda G, Souhami L, Petrecca K, Owen S, Panet-Raymond V, Guiot MC, et al. A phase 2 trial of neoadjuvant temozolomide followed by hypofractionated accelerated radiation therapy with concurrent and adjuvant temozolomide for patients with glioblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys (2017) 97(3):487–94. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.11.006

77. Soffietti R, Trevisan E, Bertero L, Cassoni P, Morra I, Fabrini MG, et al. Bevacizumab and fotemustine for recurrent glioblastoma: a phase II study of AINO (Italian Association of Neuro-Oncology). J Neurooncol (2014) 116(3):533–41. doi:10.1007/s11060-013-1317-x

78. Stummer W, Meinel T, Ewelt C, Martus P, Jakobs O, Felsberg J, et al. Prospective cohort study of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide chemotherapy for glioblastoma patients with no or minimal residual enhancing tumor load after surgery. J Neurooncol (2012) 108(1):89–97. doi:10.1007/s11060-012-0798-3

79. Stupp R, Hegi ME, Neyns B, Goldbrunner R, Schlegel U, Clement PM, et al. Phase I/IIa study of cilengitide and temozolomide with concomitant radiotherapy followed by cilengitide and temozolomide maintenance therapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol (2010) 28(16):2712–8. doi:10.1200/jco.2009.26.6650

80. Thon N, Thorsteinsdottir J, Eigenbrod S, Schüller U, Lutz J, Kreth S, et al. Outcome in unresectable glioblastoma: MGMT promoter methylation makes the difference. J Neurol (2017) 264(2):350–8. doi:10.1007/s00415-016-8355-1

81. Vaios EJ, Nahed BV, Muzikansky A, Fathi AT, Dietrich J. Bone marrow response as a potential biomarker of outcomes in glioblastoma patients. J Neurosurg (2016) 127(1):132–8. doi:10.3171/2016.7.jns16609

82. Van Mieghem E, Wozniak A, Geussens Y, Menten J, De Vleeschouwer S, Van Calenbergh F, et al. Defining pseudoprogression in glioblastoma multiforme. Eur J Neurol (2013) 20(10):1335–41. doi:10.1111/ene.12192

83. Wee CW, Kim E, Kim N, Kim IA, Kim TM, Kim YJ, et al. Novel recursive partitioning analysis classification for newly diagnosed glioblastoma: a multi-institutional study highlighting the MGMT promoter methylation and IDH1 gene mutation status. Radiother Oncol (2017) 123(1):106–11. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2017.02.014

84. Wick W, Platten M, Meisner C, Felsberg J, Tabatabai G, Simon M, et al. Temozolomide chemotherapy alone versus radiotherapy alone for malignant astrocytoma in the elderly: the NOA-08 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol (2012) 13(7):707–15. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(12)70164-x

85. Yang M, Yuan Y, Zhang H, Yan M, Wang S, Feng F, et al. Prognostic significance of CD147 in patients with glioblastoma. J Neurooncol (2013) 115(1):19–26. doi:10.1007/s11060-013-1207-2

86. Yang P, Zhang W, Wang Y, Peng X, Chen B, Qiu X, et al. IDH mutation and MGMT promoter methylation in glioblastoma: results of a prospective registry. Oncotarget (2015) 6(38):40896–906. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.5683

87. Zhang XQ, Sun S, Lam KF, Kiang MY, Pu KS, Ho SW, et al. A long non-coding RNA signature in glioblastoma multiforme predicts survival. Neurobiol Dis (2013) 58(10):123. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2013.05.011

88. Ohno M, Narita Y, Miyakita Y, Matsushita Y, Arita H, Yonezawa M, et al. Glioblastomas with IDH1/2 mutations have a short clinical history and have a favorable clinical outcome. Jpn J Clin Oncol (2016) 46(1):31–9. doi:10.1093/jjco/hyv170

89. Kim C, Kim HS, Shim WH, Choi CG, Kim SJ, Kim JH. Recurrent glioblastoma: combination of high cerebral blood flow with MGMT promoter methylation is associated with benefit from low-dose temozolomide rechallenge at first recurrence. Radiology (2017) 282(1):212–21. doi:10.1148/radiol.2016152152

90. Italiano A. Prognostic or predictive? It’s time to get back to definitions! J Clin Oncol (2011) 29(35):4718–4718. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.38.3729

91. Roa W, Kepka L, Kumar N, Sinaika V, Matiello J, Lomidze D, et al. International Atomic Energy Agency randomized phase III study of radiation therapy in elderly and/or frail patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol (2015) 33(35):4145–50. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.62.6606

92. Jordan JT, Gerstner ER, Batchelor TT, Cahill DP, Plotkin SR. Glioblastoma care in the elderly. Cancer (2016) 122(2):189–97. doi:10.1002/cncr.29742

93. Yang H, Wei D, Yang K, Tang W, Luo Y, Zhang J. The prognosis of MGMT promoter methylation in glioblastoma patients of different race: a meta-analysis. Neurochem Res (2014) 39(12):2277–87. doi:10.1007/s11064-014-1435-7

94. Rapkins RW, Wang F, Nguyen HN, Cloughesy TF, Lai A, Ha W, et al. The MGMT promoter SNP rs16906252 is a risk factor for MGMT methylation in glioblastoma and is predictive of response to temozolomide. Neuro Oncol (2015) 17(12):1589. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nov064

95. Consortium EA, Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature (2016) 536(7616):285. doi:10.1038/nature19057

96. Zhang W, Zhang J, Hoadley K, Kushwaha D, Ramakrishnan V, Li S, et al. miR-181d: a predictive glioblastoma biomarker that downregulates MGMT expression. Neuro Oncol (2012) 14(6):712. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nos089

97. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines: Central Nervous System Cancers (Version 1.2012). The Category of Central Nervous System Cancers (2016). Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp

98. Brandes AA, Franceschi E, Tosoni A, Blatt V, Pession A, Tallini G, et al. MGMT promoter methylation status can predict the incidence and outcome of pseudoprogression after concomitant radiochemotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients. J Clin Oncol (2008) 26(13):2192–7. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8163

99. Jansen M, Yip S, Louis DN. Molecular pathology in adult gliomas: diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive markers. Lancet Neurol (2010) 9(7):717–26. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70105-8

100. Li H, Li J, Cheng G, Zhang J, Li X. IDH mutation and MGMT promoter methylation are associated with the pseudoprogression and improved prognosis of glioblastoma multiforme patients who have undergone concurrent and adjuvant temozolomide-based chemoradiotherapy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg (2016) 151:31–6. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.10.004

101. Topkan E, Topuk S, Oymak E, Parlak C, Pehlivan B. Pseudoprogression in patients with glioblastoma multiforme after concurrent radiotherapy and temozolomide. Am J Clin Oncol (2012) 35(3):284–9. doi:10.1097/COC.0b013e318210f54a

102. Yin A-A, Zhang L-H, Cheng J-X, Dong Y, Liu B-L, Han N, et al. Radiotherapy plus concurrent or sequential temozolomide for glioblastoma in the elderly: a meta-analysis. PLoS One (2013) 8(9):e74242. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074242

Keywords: O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase, methylation, glioblastoma, prognosis, temozolomide

Citation: Zhao YH, Wang ZF, Cao CJ, Weng H, Xu CS, Li K, Li JL, Lan J, Zeng XT and Li ZQ (2018) The Clinical Significance of O6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase Promoter Methylation Status in Adult Patients With Glioblastoma: A Meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 9:127. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00127

Received: 03 January 2018; Accepted: 20 February 2018;

Published: 21 March 2018

Edited by:

Sandro M. Krieg, Technische Universität München, GermanyReviewed by:

Benedikt Wiestler, Technische Universität München, GermanyCopyright: © 2018 Zhao, Wang, Cao, Weng, Xu, Li, Li, Lan, Zeng and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhi-Qiang Li, bGl6aGlxaWFuZ0B3aHUuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.