- 1Department of Neurology, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, Netherlands

- 2Department of Neurology, Canisius-Wilhelmina Hospital, Nijmegen, Netherlands

We present a case of a 79-year-old man with a non-symptomatic pulsatile proptosis of the left eye. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a meningocele into the left orbit due to an osseous defect in the orbital roof.

Introduction

Basal encephalo- or meningoceles are rare, approximately 1.5% of all cases, and intraorbital encephalo- or meningoceles are even more rare. The most common causes are trauma, congenital skull malformations, and tumors (1). We present a patient with pulsatile exophthalmos due to an intraorbital meningocele.

Case Report

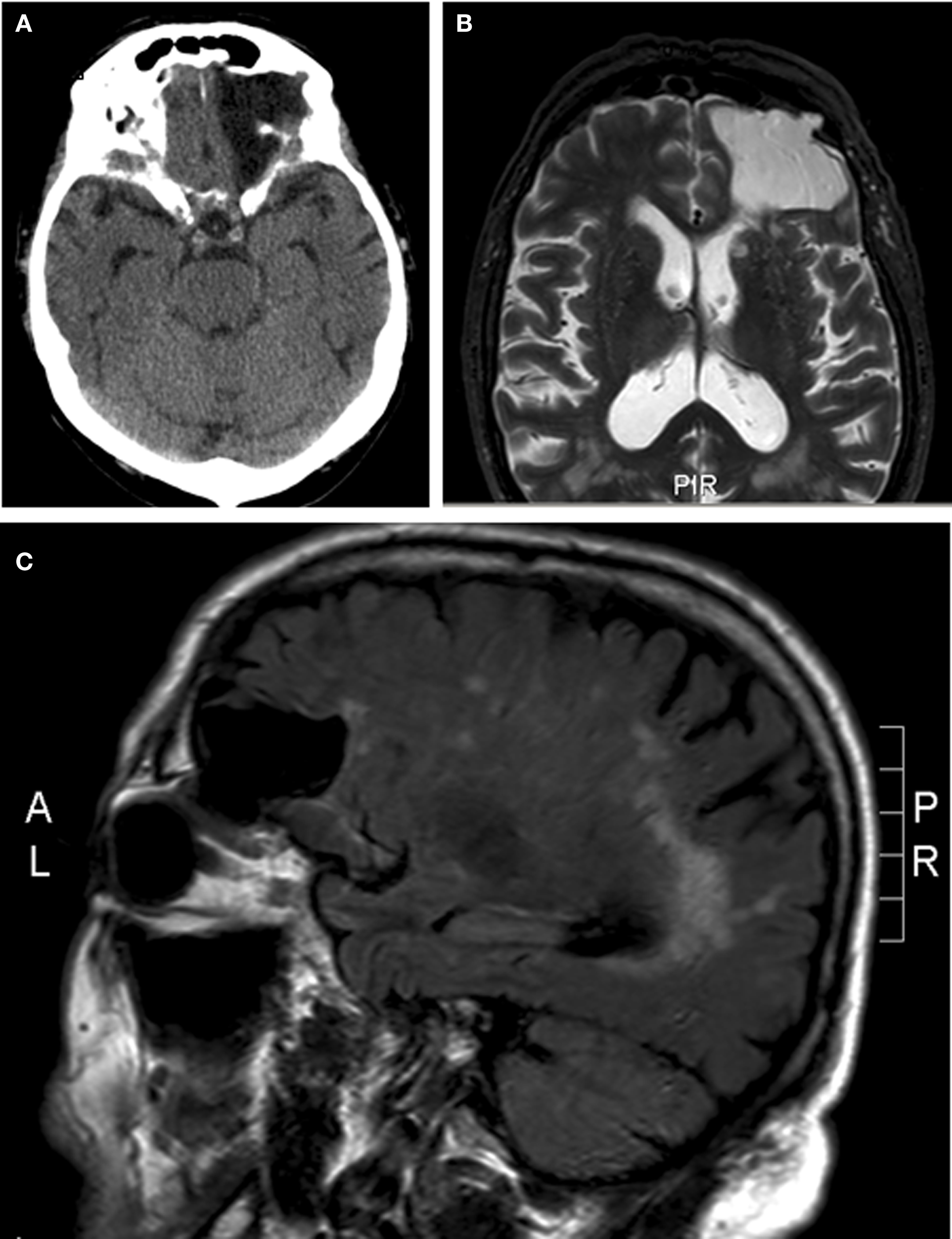

A 79-year-old man presented with a transient ischemic attack of the posterior circulation. He had no complaints at that time. On neurological examination, he had a non-symptomatic, pulse-synchronous pulsatile proptosis of the left eye (see Video S1 in Supplementary Material). According to the patient, this was present since childhood or even birth. There was no complaint of oscillopsia. He denied a history of birth trauma or head injury. He had no history of congenital anomalies, bone dysplasia, or neurofibromatosis. The neurological examination was otherwise normal and no bruit was heard. There was 4 mm proptosis of the left eye. Visual acuity without correction was for OD 1.0 and for OS 0.4. Intraocular pressure was 9 mmHg in OD and 10 mmHg in OS. Direct and indirect pupillary responses were normal. OD showed pseudophakia. OS had cataract. There was no conjunctival venous congestion nor venous congestion of the posterior poles of the eyes. Arterial abnormalities were absent in the posterior pole of the eye. He had full range eye movements without double vision. Examination of the eyes was further unremarkable. Computed tomography and MR imaging (see Figure 1) revealed a meningocele into the left orbit due to a bony defect in the orbital roof (42 mm × 37 mm). He was not bothered by the proptosis and declined surgical correction of the orbital roof.

Figure 1. Meningocele into the left orbit due to a bony defect in the orbital roof. (A) Axial computed tomography. (B) Axial magnetic resonance imaging short T1 inversion recovery sequence. (C) Sagittal magnetic resonance imaging, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis of pulsatile proptosis includes orbital roof fractures, encephalo- or meningoceles, neurosurgical procedures (1–3), neurofibromatosis type 1, and vascular malformations such as carotid-cavernous fistula and arteriovenous malformations (4, 5). Even in orbital roof fractures, pulsatile proptosis is rare (2, 3). Our patient had only a meningocele into the left orbital due to a bony defect of the orbital roof, but no history of any of the other options mentioned above. Pulsation of the brain blood vessels passed on to the CSF explains the synchrony of the eyeball pulsation to the arterial pulse. We hypothesize that he has had head injury in early childhood leading to an orbital roof fracture and posttraumatic meningocele or a congenital skull base defect. In the literature, surgery is recommended especially for late onset traumatic encephaloceles with improvement of the preoperative ocular symptoms in all patients (2, 3). However, our patient declined surgery due to the fact that he had no symptoms and only signs.

Ethics Statement

This is a case report. The patient approved publication.

Author Contributions

AR wrote the clinical information of the patient. All authors participated in the description of the images, the introduction, discussion, and abstract.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fneur.2017.00290/full#supplementary-material.

Video S1. Pulsatile proptosis of the left eye.

References

1. Morihara H, Zenke K. Intraorbital encephalocele in an adult patient presenting with pulsatile exophthalmos. Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) (2010) 50:1126–8. doi: 10.2176/nmc.50.1126

2. Antonelli V, Cremonini AM, Campobassi A, Pascarella R, Zofrea G, Servadei F. Traumatic encephalocele related to orbital roof fractures: report of six cases and literature review. Surg Neurol (2002) 57:117–25. doi:10.1016/S0090-3019(01)00667-X

3. Ha AY, Mangham W, Frommer SA, Choi D, Klinge P, Taylor HO, et al. Interdisciplinary management of minimally displaced orbital roof fractures: delayed pulsatile exophthalmos and orbital encephalocele. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr (2017) 10:11–5. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1584395

4. Papakostas TD, Lessell S. Teaching video neuroimages: pulsatile proptosis. Neurology (2013) 81(21):e160. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000436066.35760.24

Keywords: proptosis, orbital roof fracture, meningocele, pulsations, MRI imaging

Citation: van Rumund A, Verrips A and Verhagen WIM (2017) Pulsatile Proptosis due to Intraorbital Meningocele. Front. Neurol. 8:290. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00290

Received: 22 January 2017; Accepted: 06 June 2017;

Published: 19 June 2017

Edited by:

Janine Leah Johnston, University of Manitoba, CanadaReviewed by:

Shlomo Dotan, Hadassah Medical Center, IsraelJorge Kattah, University of Illinois College of Medicine Peoria, United States

Copyright: © 2017 van Rumund, Verrips and Verhagen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wim I. M. Verhagen, dy52ZXJoYWdlbkBjd3oubmw=

Anouke van Rumund1

Anouke van Rumund1 Wim I. M. Verhagen

Wim I. M. Verhagen