94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Netw. Physiol., 14 February 2025

Sec. Networks in the Cardiovascular System

Volume 5 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnetp.2025.1488349

This article is part of the Research TopicArtificial Intelligence in Cardiovascular ResearchView all 4 articles

Arterial spin labelling (ASL) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) enables cerebral perfusion measurement, which is crucial in detecting and managing neurological issues in infants born prematurely or after perinatal complications. However, cerebral blood flow (CBF) estimation in infants using ASL remains challenging due to the complex interplay of network physiology, involving dynamic interactions between cardiac output and cerebral perfusion, as well as issues with parameter uncertainty and data noise. We propose a new spatial uncertainty-based physics-informed neural network (PINN), SUPINN, to estimate CBF and other parameters from infant ASL data. SUPINN employs a multi-branch architecture to concurrently estimate regional and global model parameters across multiple voxels. It computes regional spatial uncertainties to weigh the signal. SUPINN can reliably estimate CBF (relative error

Arterial spin labelling (ASL) is a non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technique that measures cerebral blood flow (CBF) without exogenous contrast agents (Lindner et al., 2023). CBF maps can be computed on a voxel-by-voxel basis by fitting mathematical models of haemodynamics based on ordinary differential equations (ODEs) (Alsop et al., 2015). These models help capture the complex temporal dynamics of blood flow, which are essential for understanding the intricate cardiac-brain network physiology. This understanding may aid in diagnosing and managing various conditions, such as some forms of dementia and stroke (Rossi et al., 2022; Tahsili-Fahadan and Geocadin, 2017).

The bidirectional cardiac-brain network physiology operates as an intricate system where the heart and brain continuously influence each other (Candia-Rivera et al., 2024), a topic that has garnered research interest for some time (Bashan et al., 2012). The heart supplies oxygenated blood to the brain, affecting cerebral perfusion and pulsatile flow (Silverman and Petersen, 2020; Jammal Salameh et al., 2024), while the brain regulates cardiac function through the two autonomic nervous systems, the sympathetic and parasympathetic (Gordan et al., 2015). This network incorporates feedback loops such as cerebral autoregulation and neurovascular coupling to maintain optimal function (Claassen et al., 2021).

In infants, particularly those with conditions like congenital heart disease (CHD) or preterm birth, this network is especially vulnerable due to immature autoregulation and developmental sensitivity (De Silvestro et al., 2024; Claassen et al., 2021). These factors can result in altered cerebral haemodynamics, leading to issues such as delayed brain maturation, an increased risk of cerebral white matter injury, and potentially adverse long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes (McQuillen et al., 2010). Preterm neonates are often admitted to hospital to receive external physiological support whilst their bodies mature, of which brain perfusion must be sufficient during this period.

The infant demographic thus benefits from non-invasive CBF monitoring techniques like ASL (Counsell et al., 2019). ASL can provide insights into the complex physiological interplay between the heart and brain, guiding interventions to support optimal brain development and overall cardiovascular health (McQuillen et al., 2010; Castle-Kirszbaum et al., 2022).

A thorough understanding of this cardiac-brain network is crucial for managing infant health. Specifically, it is essential for optimising neuroprotection strategies, improving surgical and medical management, and enhancing the long-term neurodevelopmental prospects of these infants (De Silvestro et al., 2023). However, further research is needed to fully understand the independent effects and mechanisms of cardio-cerebral coupling (Castle-Kirszbaum et al., 2022; Meng et al., 2015), particularly in the developing infant brain (Baik-Schneditz et al., 2021). Achieving this understanding in infants will require the development of even more accurate CBF monitoring techniques than those currently available.

Computing voxel-by-voxel CBF maps is achieved by fitting mathematical models of haemodynamics based on ODEs (Alsop et al., 2015). Many of these perfusion model ODEs assume very simplified physiology (e.g., plug blood flow to the brain, single magnetisation compartments in the brain) and can therefore be solved analytically (Buxton et al., 1998; Alsop et al., 2015). It is often further assumed that the perfusion model parameters are perfectly known. In these conditions, CBF is estimated from a single perfusion-weighted image (PWI). These assumptions do not apply to CBF estimates in pathological conditions or groups with heterogeneous physiological properties, such as infants.

Imaging infants, particularly those born preterm, presents further challenges due to lower signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). This is attributed to lower baseline CBF and longer arrival times (AT) of the magnetically labelled bolus (Dubois et al., 2021; Varela et al., 2015). Additionally, the need for higher spatial resolution in smaller infant brains further reduces SNR (Dubois et al., 2021). Motion during scanning is also common in infants, further degrading image quality and leading to artifacts (Dubois et al., 2021; Varela et al., 2015).

Unfortunately, voxel-by-voxel ASL analysis is susceptible to spatial inconsistencies, amplified by the lower SNR noise in infant perfusion weighted image (PWI) signals (Krishnapriyan et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). Haemodynamic models are challenging to parameterise in the infant population due to dramatic physiological changes in the first weeks of life, during which most physiological parameters differ substantially from adult values. This is true of haemodynamic variables such as CBF, and also tissue composition, reflected in MR relaxation time constants such as

In adult ASL, CBF estimation is commonly performed at a single time point following labelling (Detre et al., 2012). This relies on several assumptions about haemodynamics and MR parameters that do not usually hold for infants. Given the complexity of the cerebral blood flow network in infants, past ASL studies in infants have therefore acquired PWIs at multiple time points following labelling to enable the simultaneous estimation of haemodynamic parameters beyond CBF, such as AT (Varela et al., 2015). Past studies estimated CBF and other parameters using methods such as least squares fitting (LSF) using the analytical solution to the perfusion ODE (Varela et al., 2015). However, due to the complexity of haemodynamic models, most model parameters need to be estimated separately. The lack of methods capable of simultaneously estimating both local and global parameters presents a significant challenge.

CBF has been estimated from infant ASL data using optimisers like LSF (Varela et al., 2015) and Bayesian estimation (Pinto et al., 2023), where adult models are fitted to the PWI signal. These voxel-by-voxel approaches often struggle with the very noisy PWIs typical of infant data, especially when estimating several parameters at once. Recently, neural network (NN)-based techniques for parameter estimation have become increasingly popular. NNs have demonstrated a remarkable ability to make accurate predictions even from noisy and corrupt data (Tian et al., 2020; Hernandez-Garcia et al., 2022). However, such performance typically requires vast amounts of training data (Tian et al., 2020), which are currently not available for infants (Korom et al., 2022; Hernandez-Garcia et al., 2022; De Silvestro et al., 2023).

Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) (Karniadakis et al., 2021), an emerging branch of machine learning, integrate physical laws (expressed as differential equations, DEs) into machine learning models. This approach improves a network’s predictive capabilities even with limited and noisy data, as the DE agreement terms effectively act as a strong regulariser (Karniadakis et al., 2021). PINNs can simultaneously solve DEs (forward problem) and estimate system parameters (inverse problem) from sparse experimental data. This makes them well-suited for biomedical applications (Ghalambaz et al., 2024), evident by their increased usage in fields such as cardiovascular (Moradi et al., 2023; Herrero Martin et al., 2022; Sahli Costabal et al., 2020; van Herten et al., 2022; Kissas et al., 2020) and brain (Sarabian et al., 2022; Kamali et al., 2023; de Vries et al., 2023; Min et al., 2023) research.

In cardiovascular studies, PINNs have been successfully applied to predict electrophysiological tissue properties from action potential recordings (Herrero Martin et al., 2022) and to diagnose atrial fibrillation by estimating electrical activation maps (Sahli Costabal et al., 2020). Additionally, PINNs have been used to quantify myocardial perfusion using MR imaging (van Herten et al., 2022) and to predict arterial pressure by analysing MRI data of blood velocity and wall displacement (Kissas et al., 2020). However, while PINNs are typically robust to noise, they suffer from the spatial inconsistencies associated with voxel-by-voxel fitting. PINNs’ performance is notoriously variable, especially in inverse mode (Bajaj et al., 2023).

A significant challenge in PINN development is that they are often tested using synthetic data, which may not be a robust benchmark for performance on experimentally-acquired data. This is because few biomedical problems described by differential equations have known analytical solutions. Consequently, applications like CBF estimation using ASL data present rare opportunities to test PINNs’ performance directly on experimental data and compare it to established parameter estimation methods such as LSF. Such real-world applications are crucial for validating and improving PINN methodologies in biomedical research.

This study introduces and evaluates PINNs as a tool for reliably estimating haemodynamic parameters from noisy infant ASL images. We propose a novel PINN framework, named Spatial Uncertainty PINN (SUPINN), which incorporates two key noise-mitigating improvements: 1) Regional: We assume neighbouring voxels share similar local parameters (e.g., CBF and AT) and therefore similar time courses. We thus propose weighting the confidence in each measurement by its spatial variability. 2) Global: For global parameters (e.g.,

Our source code is publicly available at: https://github.com/cgalaz01/supinn.

ASL brain MRI studies were conducted on seven infants aged 32–78 weeks postmenstrual age. An additional five infants were scanned but excluded due to significant motion artifacts or because they awoke during the scan, rendering the data unusable. The final cohort included three infants with no pathology, one with periventricular leukomalacia, one with basal ganglia and white matter atrophy along with mild ventriculomegaly, one with agenesis of the corpus callosum, brain atrophy, and mild ventriculomegaly, and one with mild ventriculomegaly. Although this study does not include infants with known cardiac impairment, it is sufficient as our focus at this stage is on evaluating PINNs within the available diverse cohort.

All images were acquired in a Philips 3T Achieva scanner using an 8-element head coil under ethical approval following informed parental consent (REC: 09/H0707/83). PWIs were acquired on a single mid-brain transverse plane at 12 time points (every 300 ms) following a single pulsed labelling event (Petersen et al., 2006), at a spatial resolution of

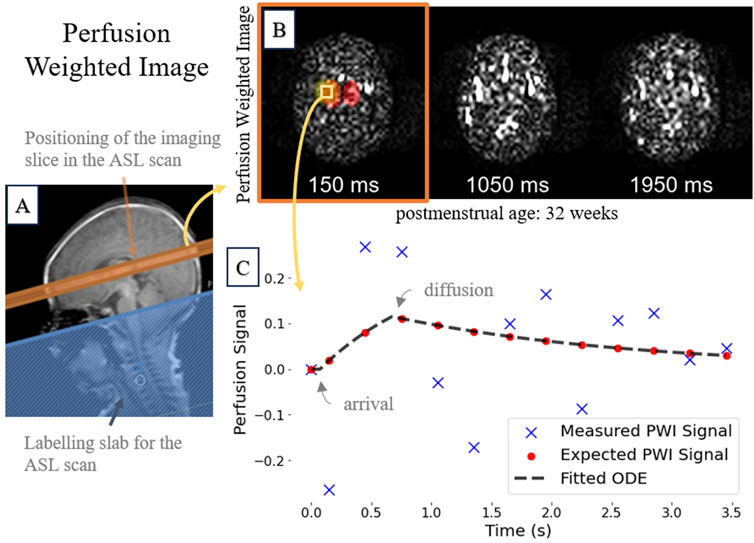

Figure 1. A representative 32-week postmenstrual case showing: (A)

To improve the SNR, the acquisition was repeated multiple times, with the number of repeats ranging from 30 to 90 depending on the remaining scanning session duration and the subject’s ability to remain still. Images identified as having motion artefacts were excluded from the averaging process based on manual inspection. Notably, no signal filtering was applied in this study to further reduce noise.

In all subjects, our analysis focused on a manually segmented region of interest that includes the thalami and basal ganglia (Figure 2). This deep grey matter region shows better SNR and fewer partial volume effects than cortical grey matter.

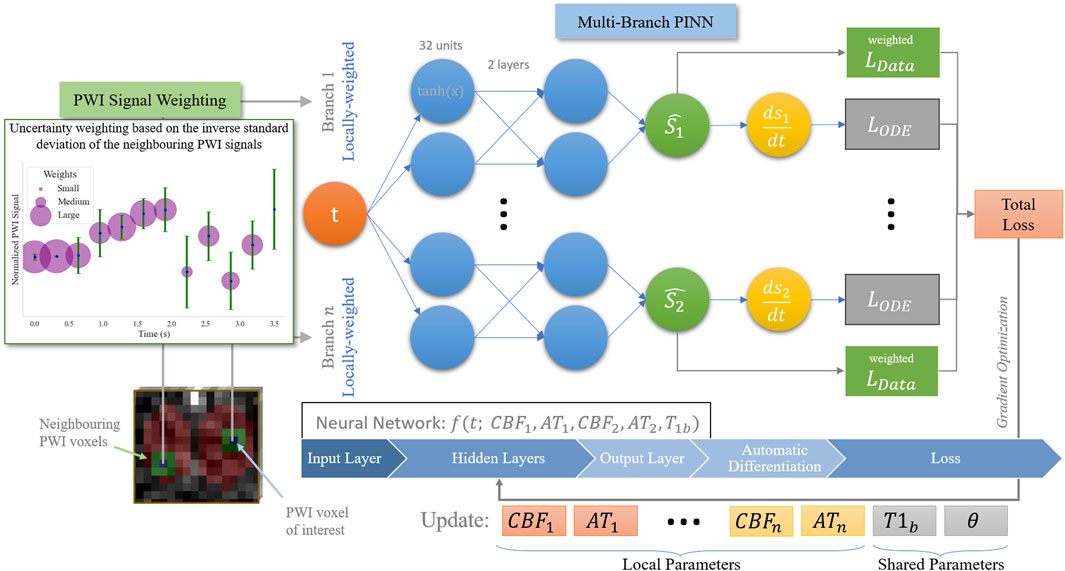

Figure 2. Overview of our proposed SUPINN model, depicted here in a two-branch variant for illustration purposes, but adaptable to larger configurations. This study employs a three-branch model based on empirical findings.

The relationship between the PWI signal,

We neglect the effect of the repeated excitation pulses on apparent

This model can be differentiated to yield an ODE defined in 3 branches:

The three branches in Equations 1, 2 depict three distinct signal evolution phases: the periods before, during, and after the arrival of labelled blood at each voxel. We found that approximating the discontinuous three-branched ODE in Equation 2 using a NN leads to poor convergence properties. To circumvent this issue, we combine the three phases using smoothing hyperbolic tangent functions (see Supplementary Table S1).

An auxiliary MRI scan was used to estimate ground-truth

Most biomedical problems described by DEs do not have an analytical solution and can only be solved numerically. For these, the accuracy of parameter identification methods is typically estimated using in silico data, which do not capture the complexities of experimental measurements. The existence of an analytical ASL haemodynamic model (Equation 2) presents a unique opportunity to test on experimental data the accuracy of model parameter estimation methods such as PINNs.

PINNs are optimised to learn a solution that both matches the data and satisfies known cardiac-brain network physiology principles. They minimise the combined loss function defined as:

where

When optimising the PINNs’ weights, we propose a three-tier hierarchical optimisation scheme (see Supplementary Table S2). We initially optimise the PINNs in forward mode, focusing on aligning the network approximately with the underlying ODE without estimating specific parameters. We then solve the ODE in inverse mode to estimate the local parameters CBF and AT, and the global parameter

PINNs are implemented using DeepXDE v1.11 (Lu et al., 2021) and TensorFlow v2.15 (Abadi et al., 2016). As a baseline PINN architecture (Raissi et al., 2019; Karniadakis et al., 2021), we use a fully connected neural network with hyperbolic tangent activation functions and two hidden layers, each consisting of 32 units. It includes one input unit for time

The baseline PINN models the signal from each voxel separately, ignoring the spatial relationships between the different sets of measurements. We expect, however, that neighbouring voxels have similar CBF and AT values, with deviations primarily due to noise. To incorporate this information in the model, we propose a spatial uncertainty PINN, SUPINN (Figure 2). SUPINN inversely weighs the contribution of each PWI time point,

SUPINN uses a multi-branch architecture to reliably estimate global (subject-specific) parameters, such as

Each SUPINN branch employs the baseline PINN architecture described in Section 2.5. We have experimentally found that using a three-branch SUPINN for this task results in an optimal balance between estimation accuracy and computational efficiency. Increasing the number of branches leads to minimal decreases in estimation error with exponentially larger computation times (see Supplementary Figure S1). In addition to the voxel of interest, two additional voxels are randomly selected within the whole region of interest that was manually delineated for the remaining branches. This delineated sampling region has an average width of

We compared SUPINN against several benchmarks: a standard PINN (Section 2.5), a robust LSF method (Varela et al., 2015), and a modified LSF (LSF-multi) that averages parameter estimations from three selected voxels. As we have limited data, evaluation against deep NN is not currently possible. All computations were performed on a 3XS Intel Core i7 CPU. The average execution times per voxel were approximately 0.05 s for LSF/LSF-multi, 31 s for PINN, and 40 s for SUPINN. Given an average voxel size in the region of interest of

Evaluation metrics include the mean and standard deviation of the relative error (RE), computed as

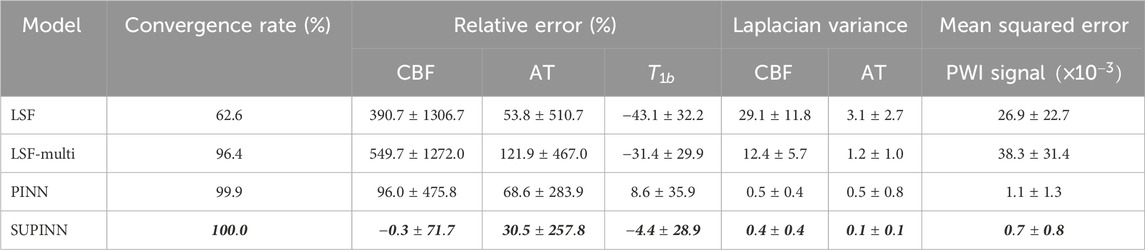

Our proposed SUPINN architecture, designed to address variable data noise levels and simultaneously estimate local and global parameters, showed excellent performance on infant ASL data (see Table 1). SUPINN showed improvements in both PWI signal (forward) and parameter (inverse) estimations compared to the standard PINN and LSF/LSF-multi methods at the cost of increased computational time.

Table 1. Summary of the convergence rate, relative error and Laplacian variance for CBF, AT and

SUPINN led to more accurate parameter estimates, especially for CBF. Specifically, SUPINN achieved a RE of

We typically observe higher noise levels in the PWI signal of younger infants. Despite this challenge, Supplementary Figure S2 shows that SUPINN consistently achieved lower RE in CBF across all subjects compared to other methods despite low SNR. Additionally, SUPINN achieved the most accurate estimates of AT and

The robustness of our model is further demonstrated in Supplementary Figure S3, where we evaluated its performance on synthetic signals. White Gaussian noise was added to each synthetically generated PWI signal to simulate stationary noise, as motion artefacts are expected to be manually removed during the averaging process. The standard deviation progressively increased in increments of 0.1, up to a maximum of 0.5. Despite increasing the standard deviation of the noise, SUPINN maintained stable parameter estimations, especially for CBF and AT. This highlights the model’s ability to handle noisy data effectively. In comparison, the baseline PINN also exhibited resilience in estimating AT and

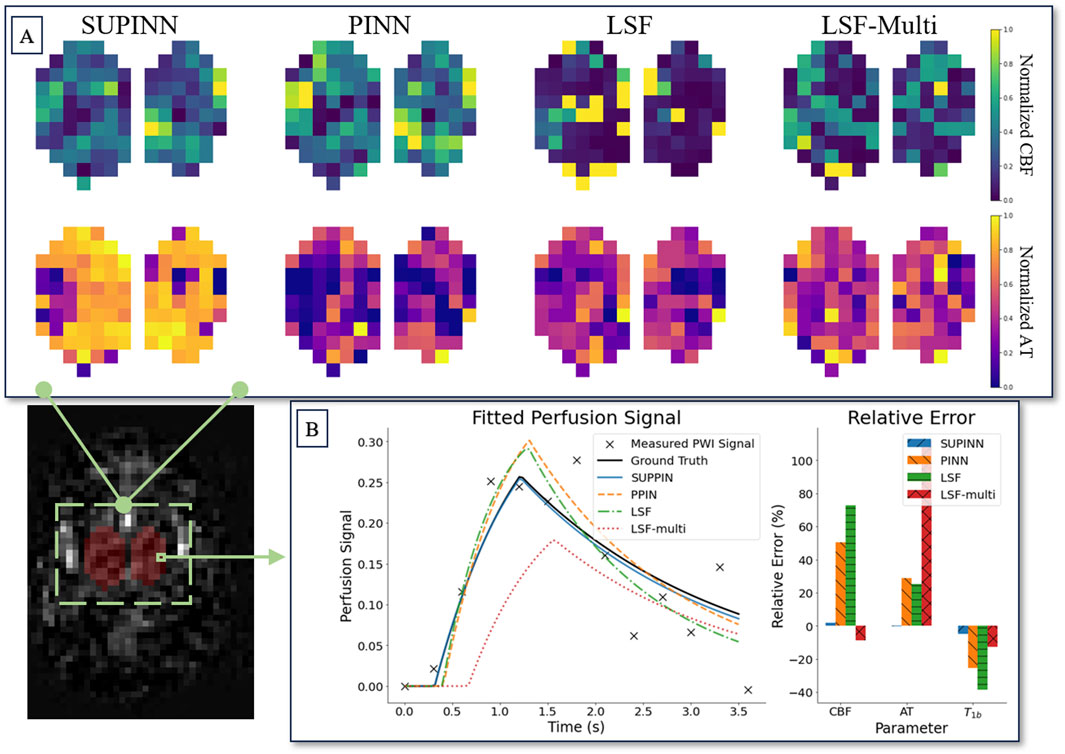

Figure 3 illustrates the spatial maps of the CBF and AT predictions for a representative infant. The SUPINN estimates, shown in the first column, exhibit higher spatial consistency for both CBF and AT compared to other methods. This consistency is quantified by the lowest Laplacian variance achieved, as detailed in Table 1. Specifically, SUPINN attained a Laplacian variance of

Figure 3. (A) Shows spatial maps of parameter estimation in deep grey matter for a subject aged 32 weeks. Each row corresponds to the normalised CBF (top) and AT (bottom) parameters. The columns display the estimation results from four methods (left to right): SUPINN, PINN, LSF, and LSF-multi. (B) Depicts the parameter relative error of the models for a single voxel.

The average normalised CBF in the region of interest, as estimated by SUPINN, showed a general increase with age, which aligns with expectations. The youngest infant, with a postmenstrual age of 38 weeks, had a CBF of

We introduce SUPINN, a novel multi-branch PINN technique for estimating parameters from noisy data. By solving ODEs over neighbouring regions with similar properties and estimating uncertainty through voxel comparisons, SUPINN simultaneously estimates local and global parameters with high accuracy. We test it on the challenging task of estimating haemodynamic parameters from extremely noisy infant multi-delay ASL data, where it outperforms both standard PINNs and LSF.

SUPINN’s strong performance is also underpinned by our three-tier optimisation regime, use of hard initial conditions and the replacement of non-differentiable transitions in the baseline model (Equation 2) by a smoothly interpolated version. These enhancements are crucial for accurately capturing the complex cerebral haemodynamics in infants, in whom subtle alterations in perfusion can have implications for brain development.

LSF is widely used for parameter identification from various medical images, including ASL. It performs reliably when estimating a small number of parameters, particularly multiplicative factors or temporal intervals (such as CBF or AT in Equation 2). Following the literature (Varela et al., 2015; Hernandez-Garcia et al., 2022), we used robust LSF to estimate ground-truth CBF and AT when separate ground-truth measurements of

PINNs have several advantages over LSF other than improved overall performance. Evidently from SUPINN, they offer a framework for more flexibly combining data from different brain and, in the future, cardiac regions. Contrary to standard PINNs, SUPINN is able to handle data with high noise to further improve performance. SUPINN leads to spatially smoother CBF and AT maps within the same brain region, aligning more closely with physiological expectations. Moreover, PINNs can be applied to ODEs with no known analytical solutions, opening up the possibility of using more sophisticated and personalised perfusion ODEs.

Recent advancements in PINN architectures, such as those described by Zou et al. (2025), Pilar and Wahlström (2024), Zou et al. (2024), further improve their utility by facilitating uncertainty quantification, particularly under conditions of heavy noise. Additionally, efforts are made towards adapting PINNs for model personalisation (Chen et al., 2021), which is useful especially when there could also be uncertainty in the assumptions used to derive the model itself. These capabilities are especially valuable when modelling the infant demographic, where data can be highly variable and noisy. Changes affecting the perfusion signal curve must be incorporated into the ODE parameters, and we expect these operator-controlled changes to result in less uncertainty than physiological unknowns. However, motion artefacts remain a challenge, requiring manual inspection and removal before averaging the PWI signal. Recent efforts have used deep learning techniques to reduce artefacts and improve overall SNR (Hales et al., 2020; Hernandez-Garcia et al., 2022).

Although SUPINN achieves spatially smoother CBF and AT maps, we employed a relatively simple sampling strategy - random sampling. This was due to the use of a single PWI plane and its lower resolution, which limited the practicality of alternative sampling approaches. In the future, we plan to acquire multiple PWI planes across the infant brain, enabling the implementation of spatially dependent sampling methods.

Since SUPINN, and to an extent LSF-multi, relies on sampling within the designated grey matter region, segmentation inaccuracies are expected to degrade overall performance due to the inclusion of lower SNR points in the branches. Such degradation for PINNs and LSF will only be observed for points outside the true region, while the true points remain unchanged. This issue could be mitigated for SUPINN by increasing the number of branches, under the assumption that the proportion of mislabelled voxels would be small, at the cost of computational time.

The multi-delay ASL data are well-suited for testing parameter identification methods, as the existence of an analytical solution allows for easy application of LSF. SUPINN’s performance can therefore be directly evaluated on real, noisy clinical data. This is in contrast to most PINN studies, which are typically evaluated on synthetic data with known noise distributions. Although our current dataset does not include cases of CHD in infants, the techniques developed here are likely to be applicable to such cases, given the similar challenges in analysing cerebral haemodynamics. Furthermore, it is encouraging to see that other research efforts have successfully utilised PINNs to estimate CBF (Ishida et al., 2024; Rotkopf et al., 2024; de Vries et al., 2023), reinforcing the potential of these methods in addressing similar challenges.

Future work will expand the evaluation to include a larger infant cohort of both healthy and CHD cases to validate the robustness and generalizability of SUPINN. This will enable us to assess the efficacy of the improved CBF estimation specifically in the context of CHD and explore its relation to the disease. Optimising voxel selection strategies and exploring alternative PINN architectures, such as graph-based approaches, can further improve performance by better representing spatial relationships critical in various clinical scenarios, including CHD.

SUPINN’s applicability extends to other problems where ODEs are solved over neighbouring regions with similar parameters. SUPINN can, for example, contribute to estimating quantitative MRI properties (such as

This paper proposes SUPINN, a PINN method able to handle noisy data by leveraging spatial information. We demonstrate its potential to improve the characterisation of haemodynamics using infant ASL. With further refinement and validation, SUPINN can become a valuable clinical tool, providing precise and accurate physiological data for diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment planning in various clinical contexts, including potential applications in infants with CHD.

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: Restricted access. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to Christoforos Galazis, Yy5nYWxhemlzMjBAaW1wZXJpYWwuYWMudWs=.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Hammersmith and Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

CG: Methodology, Software, Writing–original draft. C-EC: Software, Writing–review and editing. TA: Data curation, Writing–review and editing. AB: Supervision, Writing–review and editing. MV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing–review and editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) Centres of Doctoral Training (CDT) in Artificial Intelligence for Healthcare (AI4H http://ai4health.io) (Grant No. EP/S023283/1), St George’s Hospital Charity, the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Imperial Biomedical Research Centre (BRC), and the British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence at Imperial College London (RE/18/4/34215).

We acknowledge computational resources and support provided by the Imperial College Research Computing Service (http://doi.org/10.14469/hpc/2232).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnetp.2025.1488349/full#supplementary-material

Abadi, M., Agarwal, A., Barham, P., Brevdo, E., Chen, Z., Citro, C., et al. (2016). Tensorflow: large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous distributed systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:1603.04467

Alsop, D. C., Detre, J. A., Golay, X., Günther, M., Hendrikse, J., Hernandez-Garcia, L., et al. (2015). Recommended implementation of arterial spin-labeled perfusion mri for clinical applications: a consensus of the ismrm perfusion study group and the european consortium for asl in dementia. Magnetic Reson. Med. 73, 102–116. doi:10.1002/mrm.25197

Baik-Schneditz, N., Schwaberger, B., Mileder, L., Höller, N., Avian, A., Urlesberger, B., et al. (2021). Cardiac output and cerebral oxygenation in term neonates during neonatal transition. Children 8, 439. doi:10.3390/children8060439

Bajaj, C., McLennan, L., Andeen, T., and Roy, A. (2023). Recipes for when physics fails: recovering robust learning of physics informed neural networks. Mach. Learn. Sci. Technol. 4, 015013. doi:10.1088/2632-2153/acb416

Bashan, A., Bartsch, R. P., Kantelhardt, J. W., Havlin, S., and Ivanov, P. C. (2012). Network physiology reveals relations between network topology and physiological function. Nat. Commun. 3, 702. doi:10.1038/ncomms1705

Buxton, R. B., Frank, L. R., Wong, E. C., Siewert, B., Warach, S., and Edelman, R. R. (1998). A general kinetic model for quantitative perfusion imaging with arterial spin labeling. Magnetic Reson. Med. 40, 383–396. doi:10.1002/mrm.1910400308

Candia-Rivera, D., Chavez, M., and de Vico Fallani, F. (2024). Measures of the coupling between fluctuating brain network organization and heartbeat dynamics. Netw. Neurosci. 8, 557–575. doi:10.1162/netn_a_00369

Castle-Kirszbaum, M., Parkin, W. G., Goldschlager, T., and Lewis, P. M. (2022). Cardiac output and cerebral blood flow: a systematic review of cardio-cerebral coupling. J. Neurosurg. Anesthesiol. 34, 352–363. doi:10.1097/ANA.0000000000000768

Chen, Z., Liu, Y., and Sun, H. (2021). Physics-informed learning of governing equations from scarce data. Nat. Commun. 12, 6136. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26434-1

Claassen, J. A., Thijssen, D. H., Panerai, R. B., and Faraci, F. M. (2021). Regulation of cerebral blood flow in humans: physiology and clinical implications of autoregulation. Physiol. Rev. 101, 1487–1559. doi:10.1152/physrev.00022.2020

Counsell, S. J., Arichi, T., Arulkumaran, S., and Rutherford, M. A. (2019). Fetal and neonatal neuroimaging. Handb. Clin. neurology 162, 67–103. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-64029-1.00004-7

De Silvestro, A., Natalucci, G., Feldmann, M., Hagmann, C., Nguyen, T. D., Coraj, S., et al. (2024). Effects of hemodynamic alterations and oxygen saturation on cerebral perfusion in congenital heart disease. Pediatr. Res. 96, 990–998. doi:10.1038/s41390-024-03106-6

De Silvestro, A. A., Kellenberger, C. J., Gosteli, M., O’Gorman, R., and Knirsch, W. (2023). Postnatal cerebral hemodynamics in infants with severe congenital heart disease: a scoping review. Pediatr. Res. 94, 931–943. doi:10.1038/s41390-023-02543-z

Detre, J. A., Rao, H., Wang, D. J., Chen, Y. F., and Wang, Z. (2012). Applications of arterial spin labeled mri in the brain. J. Magnetic Reson. Imaging 35, 1026–1037. doi:10.1002/jmri.23581

de Vries, L., van Herten, R. L., Hoving, J. W., Išgum, I., Emmer, B. J., Majoie, C. B., et al. (2023). Spatio-temporal physics-informed learning: a novel approach to ct perfusion analysis in acute ischemic stroke. Med. image Anal. 90, 102971. doi:10.1016/j.media.2023.102971

Dubois, J., Alison, M., Counsell, S. J., Hertz-Pannier, L., Hüppi, P. S., and Benders, M. J. (2021). Mri of the neonatal brain: a review of methodological challenges and neuroscientific advances. J. Magnetic Reson. Imaging 53, 1318–1343. doi:10.1002/jmri.27192

Ghalambaz, M., Sheremet, M. A., Khan, M. A., Raizah, Z., and Shafi, J. (2024). Physics-informed neural networks (pinns): application categories, trends and impact. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat and Fluid Flow 34, 3131–3165. doi:10.1108/hff-09-2023-0568

Gordan, R., Gwathmey, J. K., and Xie, L.-H. (2015). Autonomic and endocrine control of cardiovascular function. World J. Cardiol. 7, 204–214. doi:10.4330/wjc.v7.i4.204

Hales, P. W., Pfeuffer, J., and A Clark, C. (2020). Combined denoising and suppression of transient artifacts in arterial spin labeling mri using deep learning. J. Magnetic Reson. Imaging 52, 1413–1426. doi:10.1002/jmri.27255

Hernandez-Garcia, L., Aramendía-Vidaurreta, V., Bolar, D. S., Dai, W., Fernández-Seara, M. A., Guo, J., et al. (2022). Recent technical developments in asl: a review of the state of the art. Magnetic Reson. Med. 88, 2021–2042. doi:10.1002/mrm.29381

Herrero Martin, C., Oved, A., Chowdhury, R. A., Ullmann, E., Peters, N. S., Bharath, A. A., et al. (2022). Ep-pinns: cardiac electrophysiology characterisation using physics-informed neural networks. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 768419. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.768419

Ishida, S., Fujiwara, Y., Takei, N., Kimura, H., and Tsujikawa, T. (2024). Comparison between supervised and physics-informed unsupervised deep neural networks for estimating cerebral perfusion using multi-delay arterial spin labeling mri. NMR Biomed. 37, e5177. doi:10.1002/nbm.5177

Jammal Salameh, L., Bitzenhofer, S. H., Hanganu-Opatz, I. L., Dutschmann, M., and Egger, V. (2024). Blood pressure pulsations modulate central neuronal activity via mechanosensitive ion channels. Science 383, eadk8511. doi:10.1126/science.adk8511

Kamali, A., Sarabian, M., and Laksari, K. (2023). Elasticity imaging using physics-informed neural networks: spatial discovery of elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio. Acta Biomater. 155, 400–409. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2022.11.024

Karniadakis, G. E., Kevrekidis, I. G., Lu, L., Perdikaris, P., Wang, S., and Yang, L. (2021). Physics-informed machine learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 422–440. doi:10.1038/s42254-021-00314-5

Kissas, G., Yang, Y., Hwuang, E., Witschey, W. R., Detre, J. A., and Perdikaris, P. (2020). Machine learning in cardiovascular flows modeling: predicting arterial blood pressure from non-invasive 4d flow mri data using physics-informed neural networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 358, 112623. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2019.112623

Korom, M., Camacho, M. C., Filippi, C. A., Licandro, R., Moore, L. A., Dufford, A., et al. (2022). Dear reviewers: responses to common reviewer critiques about infant neuroimaging studies. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 53, 101055. doi:10.1016/j.dcn.2021.101055

Krishnapriyan, A., Gholami, A., Zhe, S., Kirby, R., and Mahoney, M. W. (2021). Characterizing possible failure modes in physics-informed neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 26548–26560. doi:10.5555/3540261.3542294

Lindner, T., Bolar, D. S., Achten, E., Barkhof, F., Bastos-Leite, A. J., Detre, J. A., et al. (2023). Current state and guidance on arterial spin labeling perfusion mri in clinical neuroimaging. Magnetic Reson. Med. 89, 2024–2047. doi:10.1002/mrm.29572

Lu, L., Meng, X., Mao, Z., and Karniadakis, G. E. (2021). DeepXDE: a deep learning library for solving differential equations. SIAM Rev. 63, 208–228. doi:10.1137/19M1274067

McQuillen, P. S., Goff, D. A., and Licht, D. J. (2010). Effects of congenital heart disease on brain development. Prog. Pediatr. Cardiol. 29, 79–85. doi:10.1016/j.ppedcard.2010.06.011

Meng, L., Hou, W., Chui, J., Han, R., and Gelb, A. W. (2015). Cardiac output and cerebral blood flow: the integrated regulation of brain perfusion in adult humans. Anesthesiology 123, 1198–1208. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000872

Min, Z., Baum, Z. M., Saeed, S. U., Emberton, M., Barratt, D. C., Taylor, Z. A., et al. (2023). “Non-rigid medical image registration using physics-informed neural networks,” in International conference on information processing in medical imaging (Springer), 601–613.

Moradi, H., Al-Hourani, A., Concilia, G., Khoshmanesh, F., Nezami, F. R., Needham, S., et al. (2023). Recent developments in modeling, imaging, and monitoring of cardiovascular diseases using machine learning. Biophys. Rev. 15, 19–33. doi:10.1007/s12551-022-01040-7

Pertuz, S., Puig, D., and Garcia, M. A. (2013). Analysis of focus measure operators for shape-from-focus. Pattern Recognit. 46, 1415–1432. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2012.11.011

Petersen, E., Zimine, I., Ho, Y. L., and Golay, X. (2006). Non-invasive measurement of perfusion: a critical review of arterial spin labelling techniques. Br. J. radiology 79, 688–701. doi:10.1259/bjr/67705974

Pilar, P., and Wahlström, N. (2024). “Physics-informed neural networks with unknown measurement noise,” in 6th annual learning for dynamics and control conference (New York, United States: PMLR), 235–247.

Pinto, J., Blockley, N. P., Harkin, J. W., and Bulte, D. P. (2023). Modelling spatiotemporal dynamics of cerebral blood flow using multiple-timepoint arterial spin labelling mri. Front. Physiology 14, 1142359. doi:10.3389/fphys.2023.1142359

Raissi, M., Perdikaris, P., and Karniadakis, G. E. (2019). Physics-informed neural networks: a deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 378, 686–707. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2018.10.045

Rossi, A., Mikail, N., Bengs, S., Haider, A., Treyer, V., Buechel, R. R., et al. (2022). Heart–brain interactions in cardiac and brain diseases: why sex matters. Eur. heart J. 43, 3971–3980. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehac061

Rotkopf, L. T., Ziener, C. H., von Knebel-Doeberitz, N., Wolf, S. D., Hohmann, A., Wick, W., et al. (2024). A physics-informed deep learning framework for dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion mri. Med. Phys. 51, 9031–9040. doi:10.1002/mp.17415

Sahli Costabal, F., Yang, Y., Perdikaris, P., Hurtado, D. E., and Kuhl, E. (2020). Physics-informed neural networks for cardiac activation mapping. Front. Phys. 8, 42. doi:10.3389/fphy.2020.00042

Sarabian, M., Babaee, H., and Laksari, K. (2022). Physics-informed neural networks for brain hemodynamic predictions using medical imaging. IEEE Trans. Med. imaging 41, 2285–2303. doi:10.1109/TMI.2022.3161653

Silverman, A., and Petersen, N. H. (2020). Physiology, cerebral autoregulation. StatPearls Publishing

Tahsili-Fahadan, P., and Geocadin, R. G. (2017). Heart–brain axis: effects of neurologic injury on cardiovascular function. Circulation Res. 120, 559–572. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308446

Tian, C., Fei, L., Zheng, W., Xu, Y., Zuo, W., and Lin, C.-W. (2020). Deep learning on image denoising: an overview. Neural Netw. 131, 251–275. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2020.07.025

van Herten, R. L., Chiribiri, A., Breeuwer, M., Veta, M., and Scannell, C. M. (2022). Physics-informed neural networks for myocardial perfusion mri quantification. Med. Image Anal. 78, 102399. doi:10.1016/j.media.2022.102399

Varela, M., Hajnal, J. V., Petersen, E. T., Golay, X., Merchant, N., and Larkman, D. J. (2011). A method for rapid in vivo measurement of blood t1. NMR Biomed. 24, 80–88. doi:10.1002/nbm.1559

Varela, M., Petersen, E. T., Golay, X., and Hajnal, J. V. (2015). Cerebral blood flow measurements in infants using look–locker arterial spin labeling. J. Magnetic Reson. Imaging 41, 1591–1600. doi:10.1002/jmri.24716

Wang, S., Yu, X., and Perdikaris, P. (2022). When and why pinns fail to train: a neural tangent kernel perspective. J. Comput. Phys. 449, 110768. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2021.110768

Zimmermann, F. F., Kolbitsch, C., Schuenke, P., and Kofler, A. (2024). Pinqi: an end-to-end physics-informed approach to learned quantitative mri reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging 10, 628–639. doi:10.1109/tci.2024.3388869

Zou, Z., Meng, X., and Karniadakis, G. E. (2024). Correcting model misspecification in physics-informed neural networks (pinns). J. Comput. Phys. 505, 112918. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2024.112918

Keywords: physics-informed neural networks, cardiac-brain network physiology, neuroimaging, arterial spin labelling, cerebral blood perfusion

Citation: Galazis C, Chiu C-E, Arichi T, Bharath AA and Varela M (2025) PINNing cerebral blood flow: analysis of perfusion MRI in infants using physics-informed neural networks. Front. Netw. Physiol. 5:1488349. doi: 10.3389/fnetp.2025.1488349

Received: 29 August 2024; Accepted: 20 January 2025;

Published: 14 February 2025.

Edited by:

Alessio Gizzi, Campus Bio-Medico University, ItalyCopyright © 2025 Galazis, Chiu, Arichi, Bharath and Varela. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christoforos Galazis, Yy5nYWxhemlzMjBAaW1wZXJpYWwuYWMudWs=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.