- Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Department, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Porous media have wide application in renewable energy conversion processes, such as solar-thermal fuels production and decarbonization. Heat transport mechanisms within porous media can be highly complex, particularly under extreme conditions encountered in concentrated solar thermal reactors in which direct measurement of temperature is challenging. Here, we implement and report an inverse heat conduction model to estimate the temperature distribution throughout a porous substrate domain in a direct solar methane pyrolysis process. By solving a two-dimensional heat transfer problem and applying an inverse optimization algorithm, we estimate the quasi-steady state spatial temperature distribution in a fibrous porous carbon substrate. The results are validated indirectly by experimentally measured graphite deposition and a simplified reaction kinetic model.

1 Introduction

Sustainable energy processes are gaining increasing importance in climate risk mitigation (Chu and Majumdar, 2012), and solar energy is widely utilized in many different forms around the world (Kannan and Vakeesan, 2016). In addition to direct generation of electricity, solar energy can convert conventional fossil fuels into alternative low-carbon, carbon-neutral or even potentially carbon-negative fuels (Muradov and Veziroğlu, 2008). Methane comprises major proportions of biogas and natural gas supplies with broad applications, but it is also the second-largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions (Al-Ghussain, 2019). Additionally, location incongruity of methane generation and consumption makes methane storage and long-distance transportation necessary, typically requiring energy-intensive processes such as liquefaction (Song et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2020). As such, conversion of methane into higher-value chemicals enabled by renewable energy sources is regarded as a potential means of utilizing this abundant resource in a sustainable manner (Song et al., 2019).

Common methane conversion processes, however, burden the environment as they involve excessive carbon dioxide emission. Direct solar methane pyrolysis is an attractive approach to produce valuable chemicals in a carbon neutral or negative manner. A recent study reported a direct catalysis-free solar methane pyrolysis process that produces hydrogen while at the same time exhibiting exceptionally fast deposition of high-quality graphitic carbon on a porous substrate (Abuseada et al., 2022b; Abuseada et al., 2023). In this process, methane infiltrates a fibrous porous carbon substrate that is located near the focal plane of a solar concentrator. Detailed understanding of the thermochemical mechanisms involved is necessary to optimize field-scale utility, and accurate estimation of the temperature in the reaction zone of the fibrous porous substrate is therefore essential and the subject of the present work.

Fibrous porous media (FPM) are employed in a wide variety of applications, such as fuel cells (Farzaneh et al., 2021), thermal insulation (Lakatos, 2020), phase change heat transfer and energy storage (Ren et al., 2021; Li et al., 2013), fluid filtration and separation (Knapik and Stopa, 2018), sound absorption and reduction (Tang and Yan, 2017), bio-medicine (Chen et al., 2022), and high-temperature solar receivers with reticulated porous ceramics (Patil et al., 2021). Heat transfer analysis of such fibrous porous media is necessary to understand critical transport processes in many of these applications (Kaviany, 2012). Efforts have been made to model FPM transport properties including permeability (Xiao et al., 2019), tortuosity (Vallabh et al., 2010), and effective thermal conductivity

In the past several decades, the theory and application of inverse problems have been important in many branches of science and engineering. For example, the development of solution techniques for inverse heat transfer problems in space applications has been particularly useful due to the need to conduct complex experiments with complicated materials and limited direct experimental data (Alifanov, 2012). Typical solution logic, which is also implemented in this work, for such problems usually starts with constructing a verified numerical solution to a forward problem including unknown parameters and then estimating these unknown parameters by assimilating limited experimental data with numerical optimization techniques (Ozisik, 2018).

This paper reports the application of an inverse method in estimating the temperature distribution of a FPM in a direct solar methane pyrolysis process (Abuseada et al., 2022b; Abuseada et al., 2023). Finite-difference heat transfer methods are constructed to solve the heat diffusion equation with temperature-dependent

2 Methodology

2.1 Experimental setup

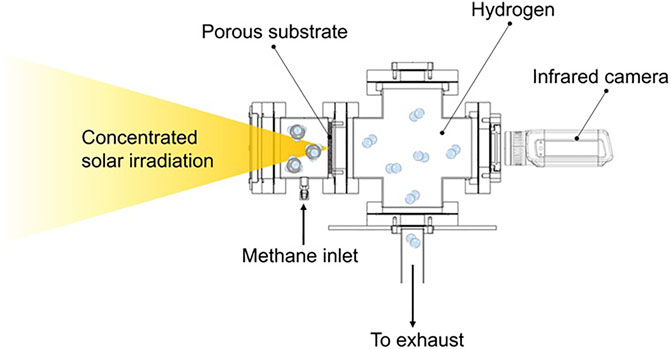

The solar-thermal experimental system is schematically illustrated in Figure 1. Concentrated solar irradiation is generated from a custom-made high flux solar simulator, which consists of a 10 kWe xenon short arc bulb (Superior Quartz, SQP-SX100003) and a silver coated aluminum ellipsoidal reflector (Optiforms, E1023F). The power output from the solar simulator is controllable by a power supply. The heat flux distribution at the focal plane inside the reactor is characterized to be Gaussian-Lorentzian (Abuseada et al., 2022a):

In the Equation 1,

The solar-thermal reactor is made of stainless steel and consists of three major sections. The reactant gas with controlled flow rate is supplied into the first section, a full nipple, which is 9.7 cm in inner diameter. Then the reactant flows through a fibrous porous carbon substrate (FuelCellEarth, C100) attached to the second major section, a reducing flange with an inner diameter of 6.86 cm. After passing through the porous reaction zone, the remaining reactant and product mixture flow into the third section, a 4-way cross. An infrared camera (FLIR, A655sc) is mounted on one of the ports of the cross, pointing toward the backside (the side without direct illumination) of the substrate, and the reactant and product gaseous mixture is passed into downstream in-situ laser diagnostics and mass spectrometry systems for species analysis and eventually into the exhaust through the bottom port.

2.2 Inverse heat transfer modeling

Inverse methods have been widely applied in solving heat transfer problem in various branches of engineering (Alifanov, 2012). We implement an inverse approach for FPM temperature estimation employing the Nelder-Mead method (Gao and Han, 2012). A schematic of the computational domain with thermal and geometric conditions is depicted in Figure 2. The back-side temperature of the substrate is measured using an infrared (IR) camera. The 2D temperature matrix is azimuthally averaged and used as an input to the inverse problem.

2.2.1 Computational approach

The steady-state heat diffusion equation in cylindrical coordinates is solved to estimate the unknown effective thermal conductivity (Faghri et al., 2010). Because of geometric symmetry, a 2D governing equation suffices to describe the problem:

where

The surrounding is treated as a blackbody with an estimated average temperature

where

The porous substrate’s emissivity in the mid-infrared band was measured to be

The governing equation and boundary conditions are discretized to numerically solve for the substrate temperature distribution via finite-differencing scheme. The elements in the substrate domain can be categorized into nine different types. Mesh independence analysis and detailed derivations of finite difference equations are provided in the supporting information (SI).

2.2.2 Effective thermal conductivity models

The effective thermal conductivity

Here,

Additionally, the porous medium substrate can possibly exhibit anisotropy in

The steady-state heat diffusion equation with anisotropic

where

2.2.3 Reaction-induced internal heat sink and temperature change

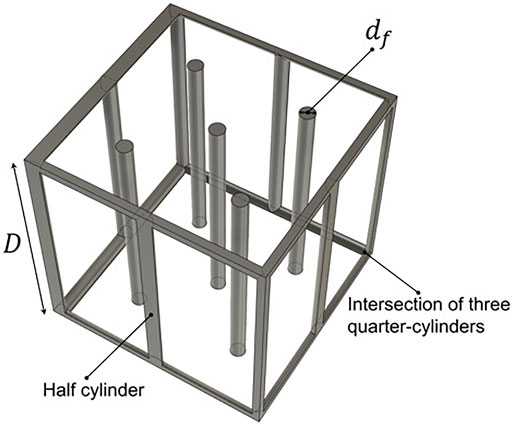

To assess the heat sink terms associated with the methane pyrolysis reaction, we construct a model to incorporate the chemical reaction. To facilitate the estimation of the magnitude of internal heat sink terms, we employ a highly simplified geometric model of the porous substrate using a periodic unit cell shown in Figure 3. The diameter of the fiber is

The porosity of the unit cell and therefore the porous substrate can be expressed as Zeng et al. (1995):

The time-averaged fiber diameter change rate is:

where the experiment duration

The reaction-induced internal heat sink is next calculated as:

Here,

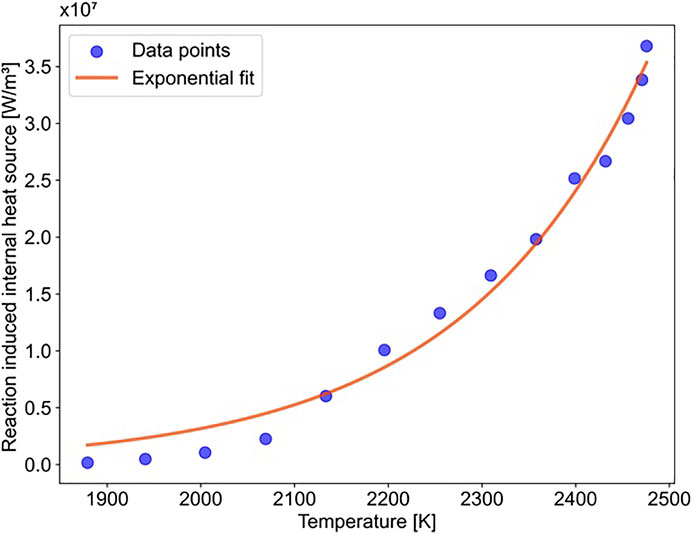

The calculated internal heat sink term is a function of the reaction temperature as shown in Figure 4. The symbols are calculated values from Equation 14; the red curve is an exponential fit as follows:

2.2.4 Penetration depth

Considering the intrinsic porosity of the substrate employed in this study, the actual solar irradiation into the substrate may not be well-described by a surface heat flux owing to the finite penetration depth into the porous substrate. To capture the influence of this consideration, the surface heat flux is converted into a shallow volumetric heat source. The actual penetration depth will depend on the incident wavelength as well as various fiber composite morphologies, and the radiative flow into the substrate follows an exponential-decay in the incident direction (Gusarov et al., 2019). In this work, the surface incident heat flux is treated as a simplified uniform heat source and calculated as:

where

2.2.5 Other assumptions

In addition to the assumptions discussed in the foregoing sections, other major assumptions include:

2.3 Fiber diameter measurements

A ZEISS Supra 40VP field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM) with a secondary electrons (SE) detector was used to obtain SEM images of graphitic carbon deposition followed by the local fiber diameter measurements. These values are applied for calculating the deposition rate and chemical reaction-induced internal heat sink.

2.4 Kinetic model for activation energy approximation

After the inverse problem is solved, we use the results to estimate reaction kinetics. The global methane decomposition reaction is usually considered to be a first order reaction (Abanades and Flamant, 2007; Holmen et al., 1995; Trommer et al., 2004), noting that such a treatment is simplified without considering the complex subreactions network and minor intermediate species. The net rate of the decomposition can thus be expressed as:

where

where

Incorporating all the information and equations above, the activation energy can be estimated from a linear-fit of the following Arrhenius expression:

3 Results and discussion

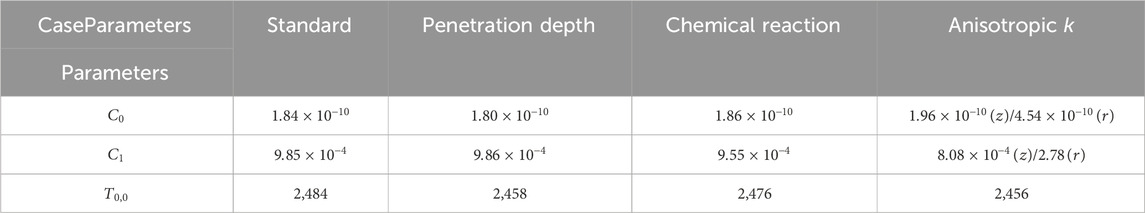

Knowledge of the reaction zone temperature is crucial for understanding and elucidating the chemical reaction kinetics, especially when the reaction is under direct light exposure. While the direct measurements and thermophysical mechanisms are extremely complex, the inverse heat transfer analysis plays an effective role in estimating the spatial temperature distribution and can provide helpful thermochemical information of the solar methane pyrolysis process under extreme conditions. In this work, we conduct inverse-estimation analyses on four cases of model differing assumptions:

1. A standard case based only on isotropic heat conduction (see section 2.2.2; Equation 6, and assumptions made in section 2.2.5 that treats the porous carbon substrate as isotropic, neglects heat absorbed by chemical reactions, and regards heat flux as a surface boundary condition).

2. An anisotropic

3. A chemical reaction case (see section 2.2.3; Equations 15, 17–19). This case, in comparison with the standard case, considers the heat absorbed by methane pyrolysis by incorporating reaction enthalpy.

4. A penetration depth case (see section 2.2.4; Equation 16). In contrast to the standard case, this case considers the finite penetration depth of the solar irradiation into the porous substrate.

3.1 Reaction zone temperature distribution and activation energy approximation

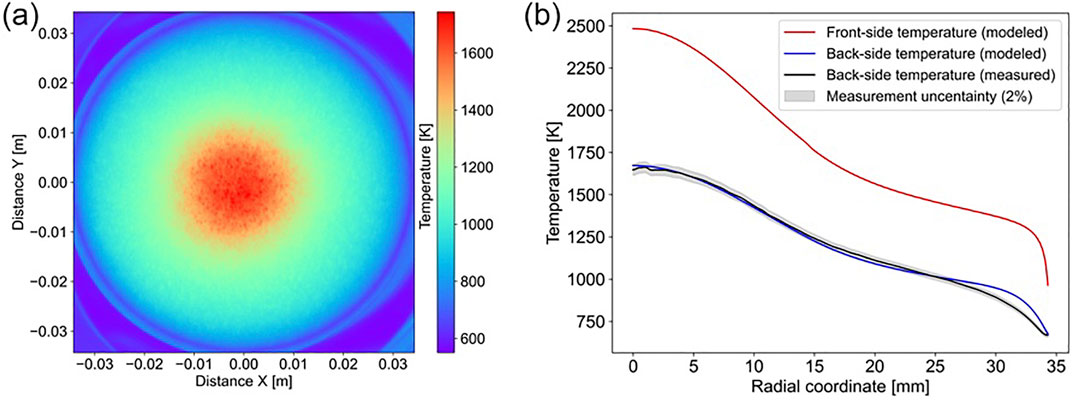

The solar methane pyrolysis experiment is conducted at a total solar power of 1.86 kW, system pressure of 3.33 kPa, methane flow of 100 sccm and experimental duration of 20 min. Substrate back-side temperature is measured using an IR camera as shown in Figure 5A. The temperature distribution is clearly symmetric about the substrate’s geometric center. As such, the two-dimensional temperature contour is azimuthally averaged without losing accuracy. The reaction-zone (front-side) temperature without considering chemical reaction, penetration depth, anisotropic effective thermal conductivity, is estimated inversely by matching the experimentally measured back-side and numerically-estimated back-side temperatures. These temperature profiles are summarized in Figure 5B. The backside temperature estimated from the inverse heat transfer model falls into the measurement uncertainty range, showing good agreement with the measured back-side temperature.

Figure 5. Temperature distributions (A) IR camera temperature contours of the back side of the porous substrate at solar power 1.86 kW, pressure 3.33 kPa, and methane flow rate 100 sccm. (B) Summary of standard case inverse-estimated front-side, back-side and experimentally measured back-side temperatures.

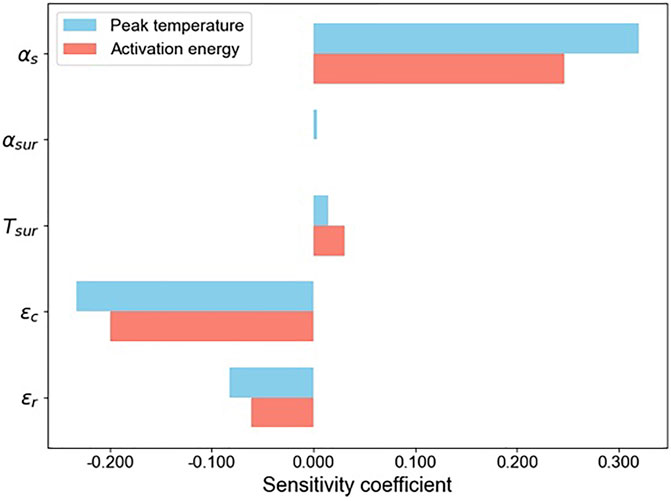

In the inverse heat transfer model, several thermal and optical parameters can influence the estimated temperature. A sensitivity analysis is conducted to quantify the effects of these parameters on the inversely-determined peak front-side temperature,

where

Based on the results summarized in Figure 6, the model is most sensitive to the absorptivity of solar irradiation

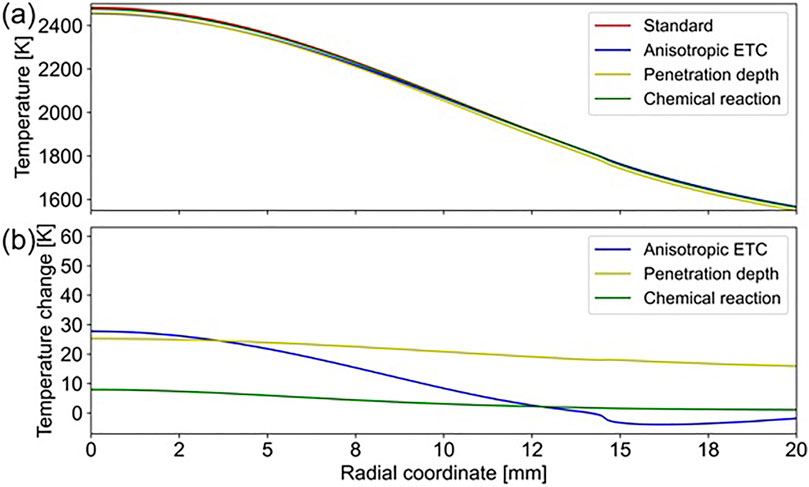

To evaluate the influence of finite penetration depth, anisotropic

Figure 7. Temperature profiles (A) and differences (B) considering penetration depth, anisotropic

These factors clearly have limited influence on predicted temperatures. The most influential consideration is the anisotropic

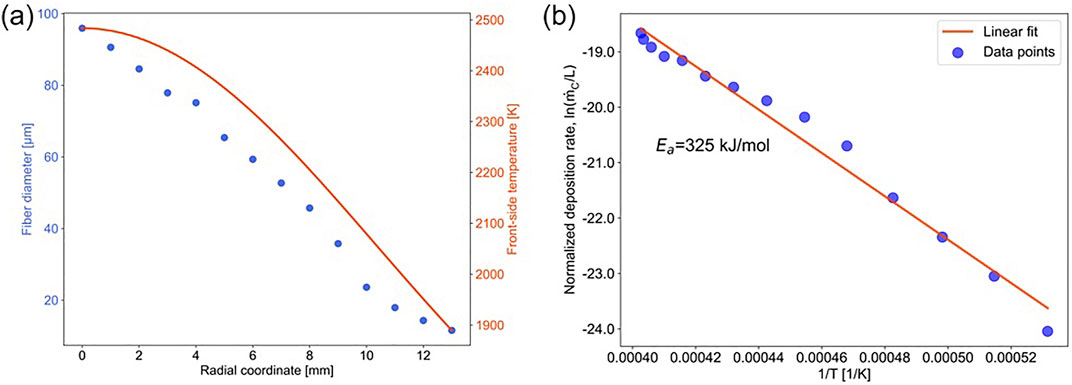

Spatial reaction-zone temperature of the standard case and fiber diameters measured using SEM at different substrate radii are shown in Figure 8A. The deposition rates derived from fiber diameters are further employed to approximate the activation energy of the global direct solar methane pyrolysis experiment through a linear fit (see Figure 8B) (Xu et al., 2024). The resulting activation energy of

Figure 8. Standard case data and analysis (A) Fiber diameter measurements and estimated spatial reaction-zone temperature. (B) Arrhenius plot and activation energy approximation.

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, we substantiate the application of the inverse method in a fibrous porous medium (FPM) temperature estimation and activation energy approximation of a direct solar-methane pyrolysis reaction. Finite-difference equations are built to solve the heat diffusion equation with assumed isotropic temperature-dependent

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

HX: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Software, Validation, Visualization. MA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft. YJ: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing–review and editing. RS: Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing–review and editing, Conceptualization, Resources. TF: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing–review and editing, Writing–original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work is supported by California Energy Commission (PIR-21-004), the US Department of Energy National Energy Technology Laboratory (DE-FE0032354) and Basic Energy Sciences division (DE-SC0023962). The authors thank the California NanoSystems Institute at UCLA and its Elman Family Foundation Innovation Fund for facilities and initial support.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jeff D. Eldredge, Abdalla Alghfeli, Yijun Ge, Indronil Ghosh and Barathan Jeevaretanam of UCLA for their helpful discussions in the process of finishing this work.

Conflict of interest

TF and RS are co-founders of SolGrapH Inc., a company specializing in solar-thermal material synthesis. This submitted work is an independent academic study and is not associated with commercial endeavors or intended as a promotion.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnano.2024.1502539/full#supplementary-material

References

Abanades, S., and Flamant, G. (2007). Experimental study and modeling of a high-temperature solar chemical reactor for hydrogen production from methane cracking. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 32, 1508–1515. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2006.10.038

Abuseada, M., Alghfeli, A., and Fisher, T. S. (2022a). Indirect inverse flux mapping of a concentrated solar source using infrared imaging. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 93, 073101. doi:10.1063/5.0090855

Abuseada, M., Spearrin, R. M., and Fisher, T. S. (2023). Influence of process parameters on direct solar-thermal hydrogen and graphite production via methane pyrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 48, 30323–30338. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.04.198

Abuseada, M., Wei, C., Spearrin, R. M., and Fisher, T. S. (2022b). Solar–thermal production of graphitic carbon and hydrogen via methane decomposition. Energy and Fuels 36, 3920–3928. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.1c04405

Abuseada, M. M. (2022). Solar-thermal production of hydrogen and graphitic carbon via methane decomposition. Ph.D. thesis. Los Angeles: University of California.

Al-Ghussain, L. (2019). Global warming: review on driving forces and mitigation. Environ. Prog. and Sustain. Energy 38, 13–21. doi:10.1002/ep.13041

Alifanov, O. M. (2012). Inverse heat transfer problems. Germany: Springer Science and Business Media.

Balat-Pichelin, M., Robert, J., and Sans, J. (2006). Emissivity measurements on carbon–carbon composites at high temperature under high vacuum. Appl. Surf. Sci. 253, 778–783. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2006.01.007

Bell, I. H., Wronski, J., Quoilin, S., and Lemort, V. (2014). Pure and pseudo-pure fluid thermophysical property evaluation and the open-source thermophysical property library coolprop. Industrial and Eng. Chem. Res. 53, 2498–2508. doi:10.1021/ie4033999

Chang, Y., and Tsou, R. (1977). Heat conduction in an anisotropic medium homogeneous in cylindrical regions—unsteady state. J. Heat Transf. 99, 41–46. doi:10.1115/1.3450652

Chen, Y., Hao, Y., Mensah, A., Lv, P., and Wei, Q. (2022). Bio-inspired hydrogels with fibrous structure: a review on design and biomedical applications. Biomater. Adv. 136, 212799. doi:10.1016/j.bioadv.2022.212799

Chu, S., and Majumdar, A. (2012). Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 488, 294–303. doi:10.1038/nature11475

Daryabeigi, K., Cunnington, G. R., and Knutson, J. R. (2011). Combined heat transfer in high-porosity high-temperature fibrous insulation: theory and experimental validation. J. Thermophys. Heat Transf. 25, 536–546. doi:10.2514/1.55989

Daryabeigi, K., Cunnington, G. R., and Knutson, J. R. (2013). Heat transfer modeling for rigid high-temperature fibrous insulation. J. Thermophys. Heat Transf. 27, 414–421. doi:10.2514/1.t3998

Faghri, A., Zhang, Y., and Howell, J. R. (2010). Advanced heat and mass transfer. Columbia, MO USA: Global Digital Press.

Farzaneh, M., Ström, H., Zanini, F., Carmignato, S., Sasic, S., and Maggiolo, D. (2021). Pore-scale transport and two-phase fluid structures in fibrous porous layers: application to fuel cells and beyond. Transp. Porous Media 136, 245–270. doi:10.1007/s11242-020-01509-7

Gao, F., and Han, L. (2012). Implementing the Nelder-Mead simplex algorithm with adaptive parameters. Comput. Optim. Appl. 51, 259–277. doi:10.1007/s10589-010-9329-3

Gusarov, A. V., Poloni, E., Shklover, V., Sologubenko, A., Leuthold, J., White, S., et al. (2019). Radiative transfer in porous carbon-fiber materials for thermal protection systems. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 144, 118582. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2019.118582

Hager, N. E., and Steere, R. C. (1967). Radiant heat transfer in fibrous thermal insulation. J. Appl. Phys. 38, 4663–4668. doi:10.1063/1.1709200

Holmen, A., Olsvik, O., and Rokstad, O. (1995). Pyrolysis of natural gas: chemistry and process concepts. Fuel Process. Technol. 42, 249–267. doi:10.1016/0378-3820(94)00109-7

Kannan, N., and Vakeesan, D. (2016). Solar energy for future world:-a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 62, 1092–1105. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.05.022

Kaviany, M. (2012). Principles of heat transfer in porous media. Germany: Springer Science and Business Media.

Knapik, E., and Stopa, J. (2018). Fibrous deep-bed filtration for oil/water separation using sunflower pith as filter media. Ecol. Eng. 121, 44–52. doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2017.07.021

Lakatos, Á. (2020). Investigation of the thermal insulation performance of fibrous aerogel samples under various hygrothermal environment: Laboratory tests completed with calculations and theory. Energy Build. 214, 109902. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2020.109902

Lee, S., and Cunnington, G. (1998). Heat transfer in fibrous insulations: comparison of theory and experiment. J. Thermophys. Heat Transf. 12, 297–303. doi:10.2514/2.6356

Lee, S.-C., and Cunnington, G. R. (2000). Conduction and radiation heat transfer in high-porosity fiber thermal insulation. J. Thermophys. Heat Transf. 14, 121–136. doi:10.2514/2.6508

Li, J.-Q., Xia, X.-L., Sun, C., Chen, X., and Wang, Q.-Y. (2024). A multispectral radiometry method for measuring the normal spectral emissivity and temperature. Infrared Phys. and Technol. 136, 105060. doi:10.1016/j.infrared.2023.105060

Li, W., Qu, Z., Zhang, B., Zhao, K., and Tao, W. (2013). Thermal behavior of porous stainless-steel fiber felt saturated with phase change material. Energy 55, 846–852. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2013.02.064

Lian, X., Tian, L., Li, Z., and Zhao, X. (2024). Thermal conductivity analysis of natural fiber-derived porous thermal insulation materials. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 220, 124941. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2023.124941

Muradov, N. Z., and Veziroğlu, T. N. (2008). “Green” path from fossil-based to hydrogen economy: an overview of carbon-neutral technologies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 33, 6804–6839. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2008.08.054

Neuer, G. (1992). Emissivity measurements on graphite and composite materials in the visible and infrared spectral range. Paris: QIRT, 92.

Patil, V. R., Kiener, F., Grylka, A., and Steinfeld, A. (2021). Experimental testing of a solar air cavity-receiver with reticulated porous ceramic absorbers for thermal processing at above 1000 °C. Sol. Energy 214, 72–85. doi:10.1016/J.SOLENER.2020.11.045

Ren, Q., Wang, Z., Lai, T., Zhang, J., and Qu, Z. (2021). Conjugate heat transfer in anisotropic woven metal fiber-phase change material composite. Appl. Therm. Eng. 189, 116618. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2021.116618

Song, H., Meng, X., Wang, Z.-j., Liu, H., and Ye, J. (2019). Solar-energy-mediated methane conversion. Joule 3, 1606–1636. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2019.06.023

Sun, L., Wang, Y., Guan, N., and Li, L. (2020). Methane activation and utilization: current status and future challenges. Energy Technol. 8, 1900826. doi:10.1002/ente.201900826

Tang, X., and Yan, X. (2017). Acoustic energy absorption properties of fibrous materials: a review. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 101, 360–380. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2017.07.002

Tong, T., and Tien, C. (1980). Analytical models for thermal radiation in fibrous insulations. J. Therm. Insulation 4, 27–44. doi:10.1177/109719638000400102

Trommer, D., Hirsch, D., and Steinfeld, A. (2004). Kinetic investigation of the thermal decomposition of CH4 by direct irradiation of a vortex-flow laden with carbon particles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 29, 627–633. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2003.07.001

Vallabh, R., Banks-Lee, P., and Seyam, A.-F. (2010). New approach for determining tortuosity in fibrous porous media. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 5, 155892501000500302. doi:10.1177/155892501000500302

Xiao, B., Wang, W., Zhang, X., Long, G., Fan, J., Chen, H., et al. (2019). A novel fractal solution for permeability and kozeny-carman constant of fibrous porous media made up of solid particles and porous fibers. Powder Technol. 349, 92–98. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2019.03.028

Xu, H., Abuseada, M., Ju, Y. S., Spearrin, R. M., and Fisher, T. S. (2024). Local thermochemical mechanisms in direct solar graphite synthesis from methane. Energy and Fuels 38, 18087–18089. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.4c03327

Keywords: solar methane pyrolysis, porous media, pyrolytic graphite, finite difference method, inverse problem

Citation: Xu H, Abuseada M, Ju YS, Spearrin RM and Fisher TS (2025) Estimation of extreme temperatures in direct solar methane pyrolysis within a porous medium. Front. Nanotechnol. 6:1502539. doi: 10.3389/fnano.2024.1502539

Received: 09 October 2024; Accepted: 27 December 2024;

Published: 30 January 2025.

Edited by:

Supriya Chakrabarti, Ulster University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Zi-Xiang Tong, Beihang University, ChinaCamilo A. Arancibia Bulnes, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico

Xinpeng Zhao, Michigan State University, United States

Copyright © 2025 Xu, Abuseada, Ju, Spearrin and Fisher. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Timothy S. Fisher, dHNmaXNoZXJAdWNsYS5lZHU=

Hengrui Xu

Hengrui Xu Mostafa Abuseada

Mostafa Abuseada Y. Sungtaek Ju

Y. Sungtaek Ju R. Mitchell Spearrin

R. Mitchell Spearrin Timothy S. Fisher

Timothy S. Fisher