- 1School of Engineering, Lancaster University, Bailrigg, Lancaster, United Kingdom

- 2College of Engineering, Taibah University, Madina, Saudi Arabia

- 3Cavendish Laboratory, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

- 4Department of Engineering, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Active modification of the polarization state is a key feature for the next-generation of wireless communications, sensing, and imaging in the THz band. The polarization modulation performance of an integrated metamaterial/graphene device is investigated via a modified THz time domain spectroscopic system. Graphene’s Fermi level is modified through electrostatic gating, thus modifying the device’s overall optical response. Active tuning of ellipticity by

1 Introduction

Recent research on optoelectronic modulators working in the terahertz (THz) band, ranging between 0.1–10 THz, has experienced an exponential growth due to its massive potential for applications, especially in the fields of wireless communications, spectroscopy, image sensing (Peiponen et al., 2013; Xu W. et al., 2017b; Zhang et al., 2021), and quantum electronics (Xu L. et al., 2017a; Liang et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2018; Fang et al., 2019; Mezzapesa et al., 2019; Almond et al., 2020; Jeannin et al., 2020; Wen et al., 2021). Amongst many approaches, only a few selected ones seem to provide flexibility, efficiency, and reconfiguration speed required by the disruptive technologies driven by the next-generation wireless communication scenarios. All-electronic approaches have represented a benchmark in the sub-THz range with remarkable performance reached by CMOS technology at 300 GHz recently (Venkatesh et al., 2020; Fujishima, 2021). Optoelectronic techniques, however, offer a higher level of miniaturization and efficiency above 500 GHz. Wireless communications beyond 5G are being deployed for mid- and near-field applications for ground communications, due to atmospheric absorption, on the promise of wide unallocated bandwidth and ultrafast communication (100 Gb-1 TB/s). An ultrafast communication platform is also needed for high-resolution imaging and sensing for most of the applications which depict the future of digital society including the digital twin world, digital fabrications, augmented reality, or holograms. All of these hungry data-rate applications have motivated research into compact and integrated THz optoelectronic devices. We are here reporting an ultrafast versatile polarization modulator based on the interplay between graphene and metamaterials.

Metamaterials are artificial subwavelength resonant elements capable to provide an electromagnetic response beyond the material of composition. This approach has proved to be particularly efficient for achieving a continuous tuning of the polarization state of THz radiation, especially when combined with active materials such as phase change materials (Ma et al., 2020; Shabanpour, 2020; Ivanov et al., 2021), semiconductors (Pitchappa et al., 2019), graphene red (Kindness et al., 2019; 2020; Zheng et al., 2020; Masyukov et al., 2020; Zaman et al., 2022a; Zaman et al., 2022b), or in MEMS arrangement metasurfaces (Cong et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2021). Fermi-energy levels of a graphene monolayer can be altered either chemically or by electrostatic gating (Shafraniuk, 2015). MMs/graphese polarization modulator was extensively investigated using gated double layers of graphene sheet reporting up to 95% of polarization conversion efficiency (Zhang et al., 2020). Ion-gel gating technique was deployed to allow chemical doping of graphene Fermi-energy which is significantly larger than electrostatic doping (Li et al., 2022), but it is not compatible with high all-electronic reconfiguration speed (

2 Design and fabrication

This complex design which has been described in detail in (Zaman et al., 2022a) is reminiscent of the nested architecture proposed by (Zhang et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2019) using 2DEG as an active material. A double gate architecture has been used to ensure robust control of graphene’s Fermi energy as well as a low operating bias voltage. The polarization mechanism is more similar to a tuneable metallic grid polarizer where the E-field polarized along its wires is rejected, rather than based on an engineered chiral response (Kindness et al., 2020) or EIT analogy (Kindness et al., 2019). The conductivity of graphene is high during the “on” state, and therefore the component of the E-field perpendicular to the SR’s orientation (i.e. y axis) becomes stronger and is transmitted. During the “off” state, however, the E-field is enhanced at resonance exhibiting a transmission of the pronounced dip as the graphene conductivity reaches its Dirac point (minimum conductivity).

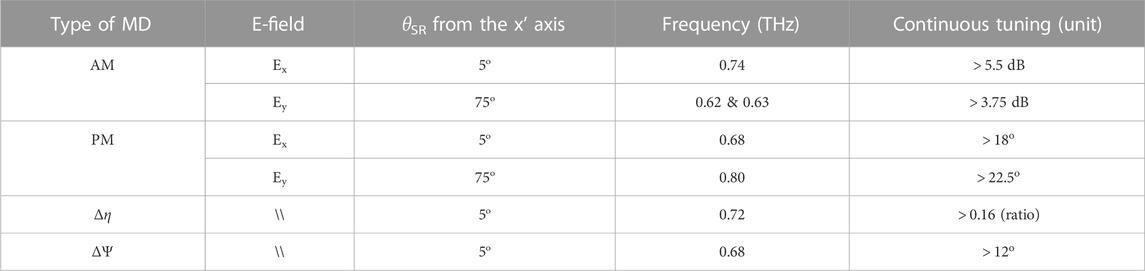

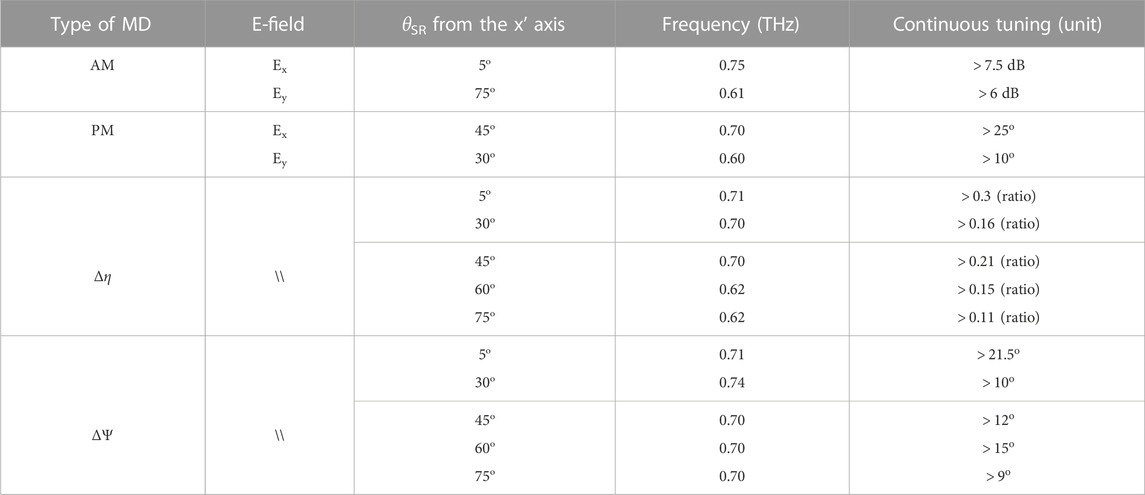

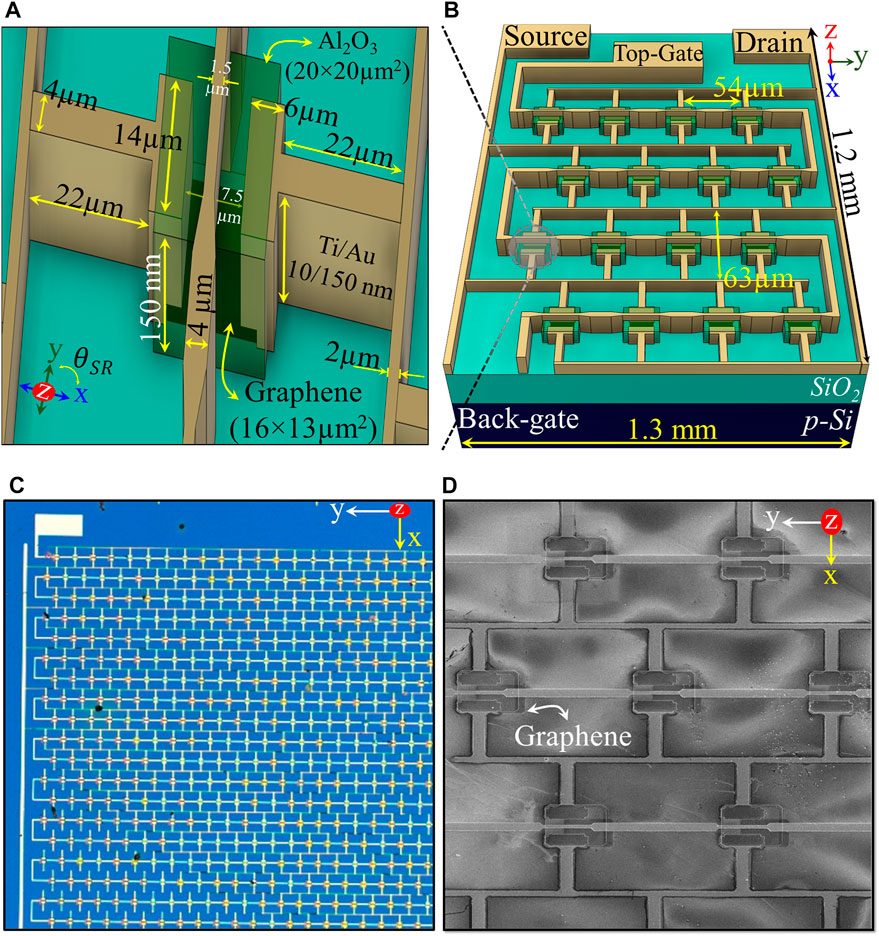

The gated split resonators (gated/SRs) are fabricated after chemical vapor deposition (CVD) grown graphene transfer on a SiO2/Si substrate (300 nm/500 μm) (Burton et al., 2019). The Si substrate is slightly p-doped to allow back-gating. Graphene is then patterned into arrays of rectangles with 16 × 14 μm2 area size via lithographic masking followed by oxygen plasma etching (RF power = 50 W, 5 s). The gated SRs are fabricated by optical lithography followed by Ti/Au thermal evaporation (10 nm/150 nm) and liftoff shunting the graphene areas as shown in Figure 1A. Both the SRs and graphene areas are then encapsulated by Al2O3 (150 nm) for protection and electrical isolation (Degl’Innocenti et al., 2017; Alexander-Webber et al., 2016). The top-gate is also formed by Ti/Au on top of the Al2O3 layer using electron beam lithography (E-beam) and positioned at the center of the SR’s capacitive gap spacing as plotted in Figure 1A. The top gate’s width shrinks to 1.5 μm when passing through the center of the SRs’ 7.5 μm gap distance. The final arrangement of the SRs is realized as a combination of 20 × 22 resonators arranged in series and parallel configurations as illustrated in Figure 1B forming a total array dimension of 1.2 × 1.3 mm2. An optical microscope and scanning electron microscope (SEM) pictures of the fabricated array are shown in Figures 1C, D, respectively.

FIGURE 1. (A) A unite-cell schematic picture showing its dimensions. (B) Top-view schematic picture of a complete gated SRs array. (C) Optical microscope and (D) SEM pictures of the fabricated SRs device.

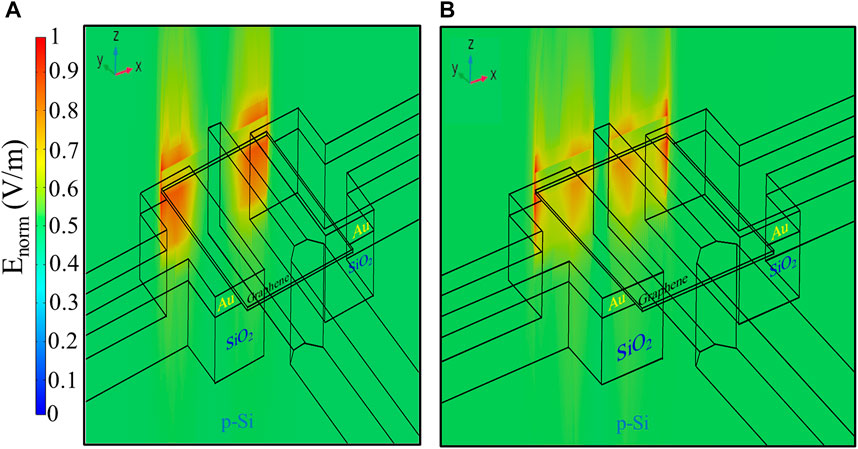

A single unite-cell’s working principles are simulated using the RF module of COMSOL Multiphysics® software. A Drude model was used to simulate graphene conductivity as well as the metallic elements. When exciting the unite-cell with an x-polarized E-field (along the SR’s axis), the E-field normalized is concentrated in the capacitive gap spacing during the “on” and “off” states at the 0.80 THz resonant frequency as plotted in Figures 2A, B, respectively. More details on simulation and fabrication are previously reported in (Zaman et al., 2022a).

FIGURE 2. Simulations of a single unit-cell with an excitation of x-polarized (along the SR’s axis) Enorm-fields at Y = +8 μm (from the center), 0.8 THz resonant frequency, and graphene conductivity of (A) 0.2 mS “off” state and (B) 1.6 mS “on” state.

3 Results and discussions

3.1 Preliminary measurements

To fully describe the polarization modulation, amplitudes and phases of the cross-polarization E-fields are separately acquired. Modulation depth (MD) of amplitudes or phases is a key factor to determine the quality performance of such a modulator. Generally, MD is defined as the normalized maximal excursion in amplitude (A) under an external stimulus as follows:

Where Amax and Amin represent the maximum and minimum values.

3.1.1 Experimental setup

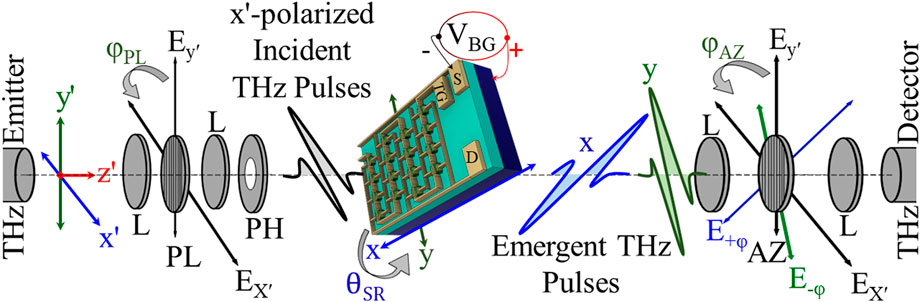

The device is inserted in a THz time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS) setup from Menlo Systems (model Tera K15) in transmission configuration with two grid polarizers, from Nearspec, positioned before and after the sample as illustrated in Figure 3. The THz emitter is always kept at the horizontal polarization state (i.e. along the x’ axis) throughout the entire measurements. The first polarizer (PL) is rotated by ΦPL = 0o with respect to the y’ axis, i.e. vertical grids and full transmission, to select only the linear horizontal incident light. After passing through a pinhole (1.1 mm diameter), the device is mounted on a rotational moving stage which can be rotated by θSR = 360o with respect to the horizontal (x’) axis allowing to excite both symmetry axes of the device (named x and y in Figure 3). A component of the incident E-field is parallel to the SR’s plane of incident (Ex), while the other is perpendicular to the SR’s plane of incident (Ey). The transmitted E-fields are then independently selected by rotating the analyzer’s (AZ’s) grids by an angle ΦAZ with respect to the vertical axis, i.e. the y’ axis. ΦAZ is rotated at different angles in accordance with the SRs’ orientations (θSR). Lastly, transmitted waves through the AZ are detected by a THz receiver that is always set to the horizontal polarization state along the x’ axis. During post-processing, the projection of E-fields on the receiver is taken into account by dividing the detected waves by sin/cos (ΦAZ) based on the AZ’s orientation.

FIGURE 3. Schematic view of the THz time domain setup (THz-TDS) where the THz emitter and detector are horizontally polarized along the x’ axis. θSR and ϕ are rotational angles with respect to x’ and y’ axes, respectively. L: lenses, PL: polarizer, PH: pinhole (Iris), VGND: ground connection that is always in contact with the graphene patches through the source and drain pads, VBG: top- or back-gates terminal, and AZ: analyzer.

3.1.2 Optoelectronic response

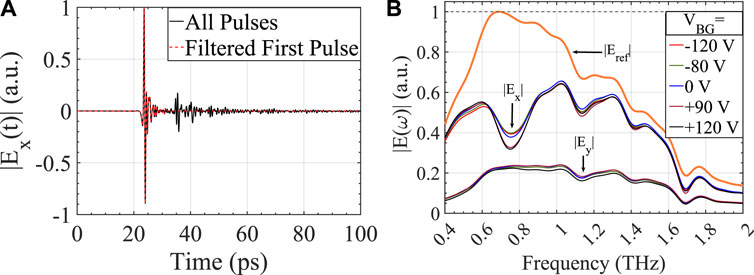

The device is electrically biased by connecting the graphene’s areas through the SRs’ elements (VGND), whereas the back-gate is connected to the positive terminal of a DC power supply from a Kethely model 2450 source meter unit (SMU). These sets of measurements are acquired by using the back-gate electrical configuration since it is more robust than the top-gate and allows a larger biasing range without risking to incur any shortages. Top-gating instead readily accessible and requires lower voltage range, but it is more susceptible to shortage mostly for wide biasing ranges. Therefore, it is faster and Compatible with fast data transmission applications. The device is driven with gate voltages (VBG) varying between −160 V and +160 V to alter the graphene conductivity around the Dirac point while measuring the gate leakage current (IBG). This range of driving voltages and Dirac point are comparable with other metamaterial devices previously reported in (Kindness et al., 2019; Kindness et al., 2020) where the 3 dB cut-off frequency reaches up to few MHz. Here, this device’s architecture was tested all-electronically demonstrating a reconfiguration speed of

FIGURE 4. (A) Temporal THz E-fields normalized to the maximum value of the filtered first pulse. (B) Spectral amplitudes of the first transmitted temporal pulse at various back-gate voltages normalized with respect to the Eref.‘s maximum value when rotating the device by θSR = 30o (from the x’ axis) and analyzer by ΦAZ = −30o and +60o (from the y’ axis). Eref. is the spectra of the first temporal pulse passing through a 1.2 × 1.2 μm2 uniform graphene patch fabricated on-chip without any SRs metal features and used for referencing.

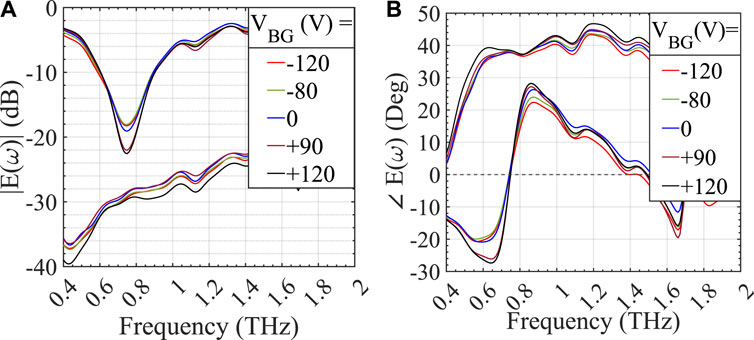

FIGURE 5. Normalized spectral amplitudes (A) and relative phases (B) considering only the first temporal pulse at different VBG voltages when θSR = 30o and ΦAZ = −30o and +60o.

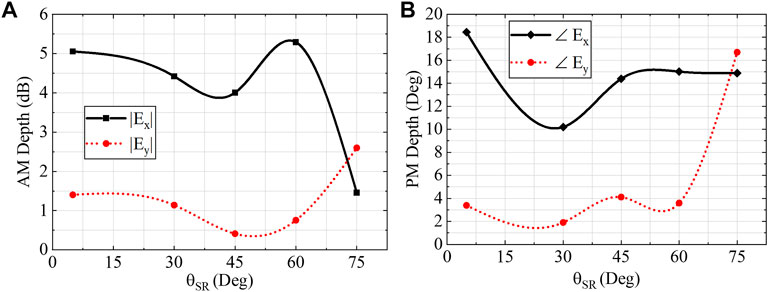

Graphene conductivity is dynamically modified by electrostatic gating, and therefore absorption of the incoming radiations at resonance is modified. Figure 6 reports the AM and PM modulation depths calculated for different device angles (θSR), from 5o to 75o. The MD was extracted for each θSR angels from the experimental data as shown in Figure 5 taking into consideration only the first temporal pulse. The MDs of Ey polarization gradually shift towards smaller frequencies in order to match a dipole resonance along the orthogonal direction (the y axis). When focusing on 0.74 THz, Ex polarized waves encounter a sharp decrease in their spectral amplitude MDs when rotating the SRs by 75o with an average of ∼5 dB as shown in Figure 6A. At the same frequency, orthogonal waves (Ey) encounter a sharp reduction in their MDs values as expected when exciting the SRs with orthogonal polarization. Although rotating the SRs’ by an angle introduces different interactions with incident THz radiations, other factors should be taken into account; e.g. principally power attenuation. It comes with the drawback of excessive power losses. A summary of several MDs achieved considering only the first temporal pulse is reported in Table 1. When taking into account the entire temporal waveform during post-processing, Ex polarized lights have an enhanced spectral amplitude MD of

FIGURE 6. Spectral AM depth for the 0.74 THz frequency (A) and PM depth for the 0.68 THz frequency (B) when processing only the first temporal pulse.

Active changing of graphene conductivity also changes the phase of the supported resonant mode. By selecting only the first temporal pulse, Ex polarization reports a continuous change of

3.2 Polarization modulation

These asymmetries in the Ex/y amplitude and phase, which vary with the device rotational angle and incident frequency, can be exploited into an active polarization device that highlights circular dichroism (CD) or optical activity (OA) depending on the user’s selected configuration. The physical principle resembles the standard electro-optic modulator arrangement with crossed polarizers in the visible light as in (Yariv, 1989) or ultraviolet (Degl’Innocenti et al., 2007) range, but without the need for long crystals which would be impractical at these wavelengths. Other active metamaterial architectures demonstrated a similar mechanism by combining phase change materials (VO2) with metamaterial arrays (Ivanov et al., 2021). Whilst this approach is effective in yielding large modulation of polarization states, it can not match the ultrafast speed demonstrated by graphene-based modulators.

3.2.1 Theoretical description

The theoretical frame from (Wang et al., 2018; Ji et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2021) was used to better investigate and describe the performance of this device when operated as a polarization modulator. Alternative more comprehensive theoretical frames can be used to model these results, e.g. using the Poincare’ sphere (Cai et al., 2021). However, for the case of flat metasurfaces with a well-defined polarization input state and wave-vector perpendicular direction as in this case, a commonly used modelling based on Jones matrices is commonly adopted. The incoming linearly polarized light is projected into two perpendicular components Ex and Ey along the two symmetry axes of the device by rotating the sample as shown in Figure 3. These two E-field components experience a different complex refractive index. Electrostatic gating the graphene conductivity is modifying the complex refractive indices, hence causing different interactions for the cross-polarized transmitted E-field waves. Changes in the real part of the refractive index is producing a continuous tuning in the rotation of polarization plane (OA), while changes in the imaginary part of the refractive index is causing dynamic manipulations in ellipticity ratio of the elliptically polarized transmitted radiations (CD). The transmitted linearly polarized coefficients selected by the analyzer are converted into circular ones by following Jones formalism as follows (Wang et al., 2018; Ji et al., 2019; 2021; Fan et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2021):

Where Ex and Ey complex components are the transmitted vectors projected either along or orthogonal to the SR’s axis (x or y), respectively. Both detected fields are normalized with respect to the Eref. pulses with the graphene sheet reference rotated by the same rotational angle as the SRs’ orientation. Both linear and circular components are used to describe either the OA (Ψ) or CD (η) as follows (Wang et al., 2018; Ji et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2021):

Where Ψ(ω) and η(ω) units are in degrees and dimensionless, respectively. ERCP and ELCP complex values, in Eq. 4, are calculated using Eq. 2. The linear scale of η indicates the ratio between the elliptical major and minor axes, hence complete linear or perfect circular polarization states correspond to 0 or ±1, respectively. Independent control of the OA and CD is a key element for achieving more degrees of freedom for polarization modulators, even though it is difficult to achieve the two effects independently. The detected linear transmission coefficients are also used to retrieve the state of polarization ellipses. The quadratic equation in Cartesian components of the ellipses is described as follows (Ji et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2021):

Where Ex and Ey are the major and minor axes of an elliptically polarized wave and represent the transmitted E-fields projected along the modulator’s axes. Eq. 5 is solved in bipolar coordinates with their major and minor vectors’ magnitudes normalized to the maximum value of the major vector prior plotting the polarization curves.

3.2.2 Single pulse processing

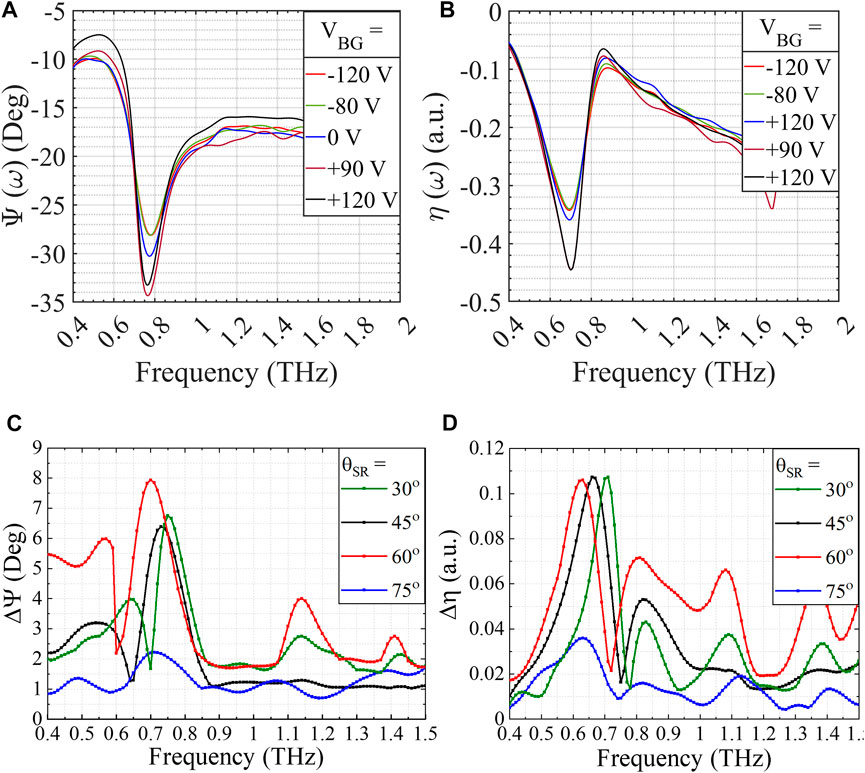

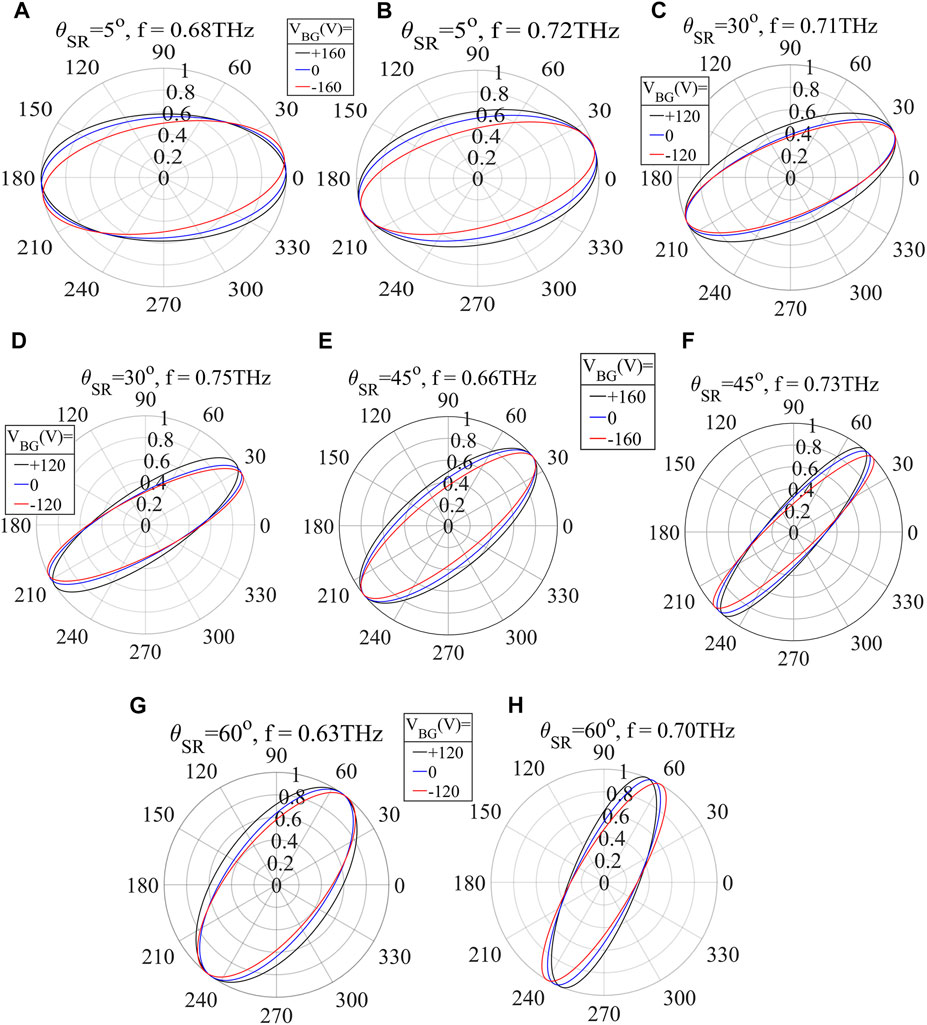

For each applied voltage, both cross-polarization waves transmitted from the device are consecutively acquired by rotating the analyzer with the correct ΦAZ angle based on the SR’s orientations. During post-processing, the first temporal pulse is considered throughout this section’s data analysis as plotted in Figure 4A. Continuous rotation of Ψ by

FIGURE 7. OA (A) and ellipticty ratio (B) at different biasing conditions when θSR = 30o and ΦAZ = −30o and +60o. Active modulation depths of OA (C) and CD (D) for various θSR angles. These values have been calculated by considering only the first temporal pulse.

FIGURE 8. (A–H) Polarization state ellipses for different SRs angles considering the first transmitted temporal pulse.

3.2.3 All pulses processing

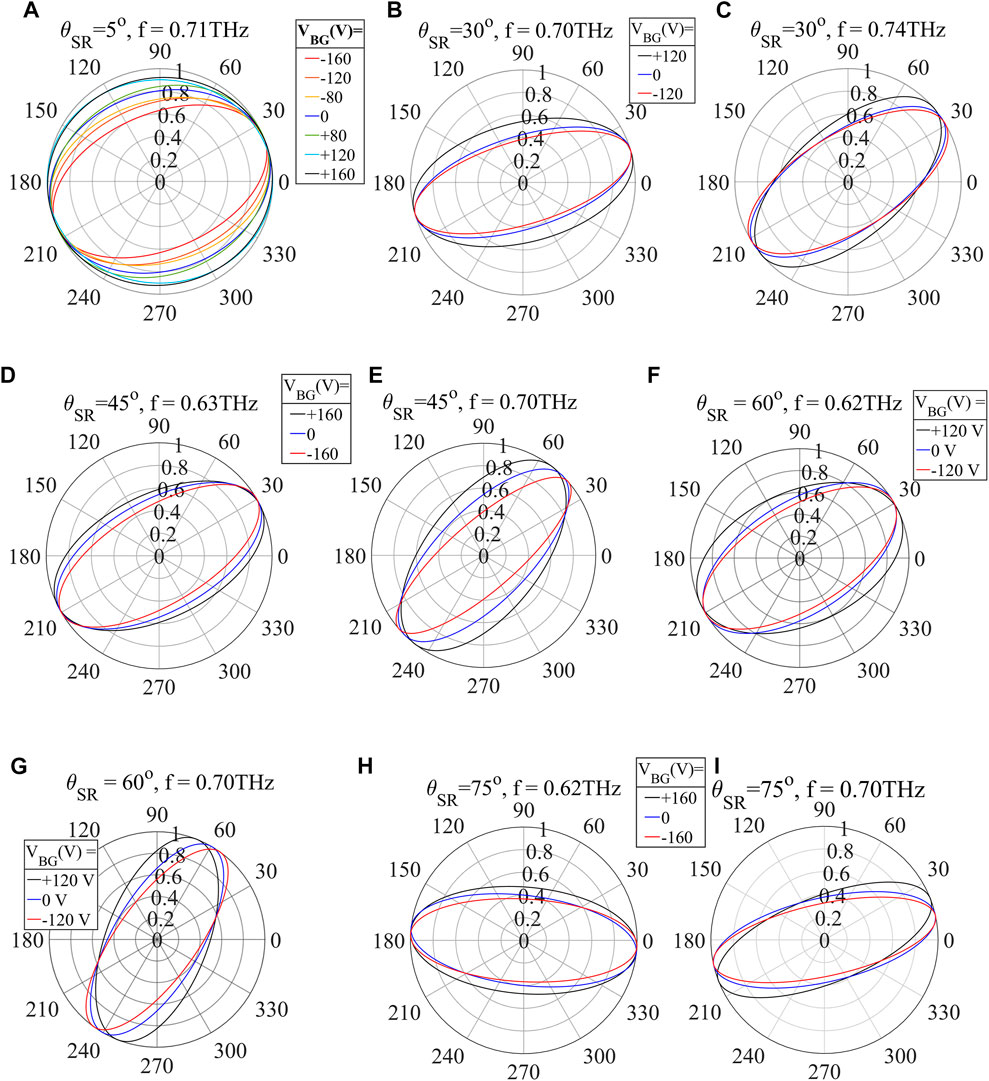

The inclusion of all temporal pulses during post-processing, however, offers a further opportunity to enhance the modulation of the polarization state at the same frequencies. Dynamic changes of Ψ and η exceed 21.5o and 0.3, respectively, at 0.71 THz and θSR = 5o as presented by the polarization ellipses in Figure 9A for various back-gate voltages. Moreover, decoupling of OA and CD is observed when rotating the SRs by any other angle besides θSR = 5o as shown in Figures 9B–K and reported in Table 2. When θSR = 45o, dynamics of Δη are also maximized to

FIGURE 9. (A–I) Polarization ellipses for different SRs angles considering all transmitted temporal pulses.

4 Conclusion

External integrated optoelectronic polarization modulators based on the interplay between graphene and metallic metamaterial arrays have been investigated by terahertz time-domain spectroscopy for applications such as GHz-speed communication, spectroscopy, and imaging. By electrostatic gating the graphene/metamaterials split resonators, polarization modulation was reported with dynamic conversions from linear to elliptical polarization states. When processing only the first temporal pulse, the amplitude extinction ratio was demonstrated achieving

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: Lancaster University’s repository, https://doi.org/10.17635/lancaster/researchdata/562.

Author contributions

AZ, NA, JG, HB, DR, OB, JA-W, SH, and TM did part of fabrication. AZ, YL, and RD’I did the measurements. AZ did post-processing and wrote the article together with contribution from all coauthors. RD’I and AZ conceived the idea.

Funding

AZ, YL, and RD’I acknowledge support from EPSRC, (Grant No. EP/S019383/1 and EP/P021859/1). JA-W acknowledges the support of his Royal Society Dorothy Hodgkin Research Fellowship.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alexander-Webber, J. A., Sagade, A. A., Aria, A. I., Veldhoven, Z. A. V., Braeuninger-Weimer, P., Wang, R., et al. (2016). Encapsulation of graphene transistors and vertical device integration by interface engineering with atomic layer deposited oxide. 2D Mater 4, 011008. doi:10.1088/2053-1583/4/1/011008

Almond, N. W., Qi, X., Degl’Innocenti, R., Kindness, S. J., Michailow, W., Wei, B., et al. (2020). External cavity terahertz quantum cascade laser with a metamaterial/graphene optoelectronic mirror. Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 041105. doi:10.1063/5.0014251

Bader, S., and Parkin, S. (2010). Spintronics. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 1, 71–88. doi:10.1146/annurev-conmatphys-070909-104123

Burton, O. J., Babenko, V., Veigang-Radulescu, V.-P., Brennan, B., Pollard, A. J., and Hofmann, S. (2019). The role and control of residual bulk oxygen in the catalytic growth of 2D materials. J. Phys. Chem. C 123, 16257–16267. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b03808

Cai, X., Tang, R., Zhou, H., Li, Q., Ma, S., Wang, D., et al. (2021). Dynamically controlling terahertz wavefronts with cascaded metasurfaces. Adv. Photonics 3, 036003. doi:10.1117/1.AP.3.3.036003

Choi, W. J., Cheng, G., Huang, Z., Zhang, S., Norris, T. B., and Kotov, N. A. (2019). Terahertz circular dichroism spectroscopy of biomaterials enabled by kirigami polarization modulators. Nat. Mat. 18, 820–826. doi:10.1038/s41563-019-0404-6

Cong, L., Pitchappa, P., Wang, N., and Singh, R. (2019). Electrically programmable terahertz diatomic metamolecules for chiral optical control. Research 2019, 7084251. doi:10.34133/2019/7084251

Degl’Innocenti, R., Majkic, A., Vorburger, P., Poberaj, G., Günter, P., and Döbeli, M. (2007). Ultraviolet electro-optic amplitude modulation in β-BaB2O4 waveguides. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 051105. doi:10.1063/1.2761484

Degl’Innocenti, R., Xiao, L., Kindness, S. J., Kamboj, V. S., Wei, B., Braeuninger-Weimer, P., et al. (2017). Bolometric detection of terahertz quantum cascade laser radiation with graphene-plasmonic antenna arrays. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 50, 174001. doi:10.1088/1361-6463/aa64bf

Fan, F., Zhao, D., Tan, Z., Ji, Y., Cheng, J., and Chang, S. (2021). Magnetically induced terahertz birefringence and chirality manipulation in transverse-magnetized metasurface. Adv. Opt. Mat. 9, 2101097. doi:10.1002/adom.202101097

Fang, M., Shen, N.-H., Sha, W. E. I., Huang, Z., Koschny, T., and Soukoulis, C. M. (2019). Nonlinearity in the dark: Broadband terahertz generation with extremely high efficiency. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 027401. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.027401

Fujishima, M. (2021). Future of 300 GHz band wireless communications and their enabler, CMOS transceiver technologies. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 60, SB0803. doi:10.35848/1347-4065/abdf24

Ivanov, A. V., Tatarenko, A. Y., Gorodetsky, A. A., Makarevich, O. N., Navarro-Cía, M., Makarevich, A. M., et al. (2021). Fabrication of epitaxial W-doped VO2 nanostructured films for terahertz modulation using the solvothermal process. ACS Appl. Nano Mat. 4, 10592–10600. doi:10.1021/acsanm.1c02081

Jeannin, M., Bonazzi, T., Gacemi, D., Vasanelli, A., Suffit, S., Li, L., et al. (2020). High temperature metamaterial terahertz quantum detector. Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 251102. doi:10.1063/5.0033367

Ji, Y., Fan, F., Xu, S., Yu, J., and Chang, S. (2019). Manipulation enhancement of terahertz liquid crystal phase shifter magnetically induced by ferromagnetic nanoparticles. Nanoscale 11, 4933–4941. doi:10.1039/C8NR09259A

Ji, Y., Fan, F., Zhang, Z., Tan, Z., Zhang, X., Yuan, Y., et al. (2021). Active terahertz spin state and optical chirality in liquid crystal chiral metasurface. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 085201. doi:10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.5.085201

Jnawali, G., Rao, Y., Yan, H., and Heinz, T. F. (2013). Observation of a transient decrease in terahertz conductivity of single-layer graphene induced by ultrafast optical excitation. Nano Lett. 13, 524–530. doi:10.1021/nl303988q

Kindness, S. J., Almond, N. W., Michailow, W., Wei, B., Delfanazari, K., Braeuninger-Weimer, P., et al. (2020). A terahertz chiral metamaterial modulator. Adv. Opt. Mat. 8, 2000581. doi:10.1002/adom.202000581

Kindness, S. J., Almond, N. W., Michailow, W., Wei, B., Jakob, L. A., Delfanazari, K., et al. (2019). Graphene-integrated metamaterial device for all-electrical polarization control of terahertz quantum cascade lasers. ACS Photonics 6, 1547–1555. doi:10.1021/acsphotonics.9b00411

Li, Q., Cai, X., Liu, T., Jia, M., Wu, Q., Zhou, H., et al. (2022). Gate-tuned graphene meta-devices for dynamically controlling terahertz wavefronts. Nanophotonics 11, 2085–2096. doi:10.1515/nanoph-2021-0801

Liang, G., Zeng, Y., Hu, X., Yu, H., Liang, H., Zhang, Y., et al. (2017). Monolithic semiconductor lasers with dynamically tunable linear-to-circular polarization. ACS Photonics 4, 517–524. doi:10.1021/acsphotonics.6b00703

Lin, R., Lu, F., He, X., Jiang, Z., Liu, C., Wang, S., et al. (2021). Multiple interference theoretical model for graphene metamaterial-based tunable broadband terahertz linear polarization converter design and optimization. Opt. Express 29, 30357–30370. doi:10.1364/OE.438256

Liu, C., Zhang, S., Wang, S., Cai, Q., Wang, P., Tian, C., et al. (2021). Active spintronic-metasurface terahertz emitters with tunable chirality. Adv. Photonics 3, 056002. doi:10.1117/1.AP.3.5.056002

Liu, Y., Bai, Z., Xu, Y., Wu, X., Sun, Y., Li, H., et al. (2020). Generation of tailored terahertz waves from monolithic integrated metamaterials onto spintronic terahertz emitters. Nanotechnology 32, 105201. doi:10.1088/1361-6528/abcc98

Ma, H., Wang, Y., Lu, R., Tan, F., Fu, Y., Wang, G., et al. (2020). A flexible, multifunctional, active terahertz modulator with an ultra-low triggering threshold. J. Mat. Chem. C 8, 10213–10220. doi:10.1039/D0TC02446E

Markl, D., Strobel, A., Schlossnikl, R., Bøtker, J., Bawuah, P., Ridgway, C., et al. (2018). Characterisation of pore structures of pharmaceutical tablets: A review. Int. J. Pharm. 538, 188–214. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.01.017

Masyukov, M., Vozianova, A., Grebenchukov, A., Gubaidullina, K., Zaitsev, A., and Khodzitsky, M. (2020). Optically tunable terahertz chiral metasurface based on multi-layered graphene. Sci. Rep. 10, 3157. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-60097-0

Mezzapesa, F. P., Pistore, V., Garrasi, K., Li, L., Davies, A. G., Linfield, E. H., et al. (2019). Tunable and compact dispersion compensation of broadband THz quantum cascade laser frequency combs. Opt. Express 27, 20231–20240. doi:10.1364/OE.27.020231

Papaioannou, E. T., and Beigang, R. (2021). THz spintronic emitters: A review on achievements and future challenges. Nanophotonics 10, 1243–1257. doi:10.1515/nanoph-2020-0563

Peiponen, K.-E., Zeitler, J. A., and Kuwata-Gonokami, M. (2013). Terahertz spectroscopy and imaging. Berlin: Springer.

Pitchappa, P., Kumar, A., Prakash, S., Jani, H., Venkatesan, T., and Singh, R. (2019). Chalcogenide phase change material for active terahertz photonics. Adv. Mat. 31, 1808157. doi:10.1002/adma.201808157

Plank, H., and Ganichev, S. D. (2018). A review on terahertz photogalvanic spectroscopy of Bi2Te3- and Sb2Te3-based three dimensional topological insulators. Solid-State Electron. 147, 44–50. doi:10.1016/j.sse.2018.06.002

Shabanpour, J. (2020). Programmable anisotropic digital metasurface for independent manipulation of dual-polarized thz waves based on a voltage-controlled phase transition of VO2 microwires. J. Mat. Chem. C 8, 7189–7199. doi:10.1039/D0TC00689K

Shafraniuk, S. (2015). Graphene: Fundamentals, devices, and applications. Singapore: Jenny Stanford Publishing. Available at: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/lancaster/detail.action?docID=1726100.

Shi, S.-F., Tang, T.-T., Zeng, B., Ju, L., Zhou, Q., Zettl, A., et al. (2014). Controlling graphene ultrafast hot carrier response from metal-like to semiconductor-like by electrostatic gating. Nano Lett. 14, 1578–1582. doi:10.1021/nl404826r

Son, J.-H. (2020). Terahertz biomedical science & technology. 1st edn. Boca Raton, Florida: London: CRC Press.

Venkatesh, S., Lu, X., Saeidi, H., and Sengupta, K. (2020). A high-speed programmable and scalable terahertz holographic metasurface based on tiled CMOS chips. Nat. Electron 3, 785–793. doi:10.1038/s41928-020-00497-2

Wang, S., Kang, L., and Werner, D. H. (2018). Active terahertz chiral metamaterials based on phase transition of vanadium dioxide (VO2). Sci. Rep. 8, 189. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-18472-x

Watanabe, S. (2018). Terahertz polarization imaging and its applications. Photonics 5, 58. doi:10.3390/photonics5040058

Wei, B., Kindness, S. J., Almond, N. W., Wallis, R., Wu, Y., Ren, Y., et al. (2018). Amplitude stabilization and active control of a terahertz quantum cascade laser with a graphene loaded split-ring-resonator array. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 201102. doi:10.1063/1.5027687

Wen, Y., Xu, T., and Lin, Y.-S. (2021). Design of electrostatically tunable terahertz metamaterial with polarization-dependent sensing characteristic. Results Phys. 29, 104798. doi:10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104798

Winnerl, S., Göttfert, F., Mittendorff, M., Schneider, H., Helm, M., Winzer, T., et al. (2013). Time-resolved spectroscopy on epitaxial graphene in the infrared spectral range: Relaxation dynamics and saturation behavior. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 25, 054202. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/25/5/054202

Xu, L., Chen, D., Curwen, C. A., Memarian, M., Reno, J. L., Itoh, T., et al. (2017a). Metasurface quantum-cascade laser with electrically switchable polarization. Optica 4, 468–475. doi:10.1364/OPTICA.4.000468

Xu, R., Xu, X., Yang, B.-R., Gui, X., Qin, Z., and Lin, Y.-S. (2021). Actively logical modulation of MEMS-based terahertz metamaterial. Phot. Res. 9, 1409–1415. doi:10.1364/PRJ.420876

Xu, W., Xie, L., and Ying, Y. (2017b). Mechanisms and applications of terahertz metamaterial sensing: A review. Nanoscale 9, 13864–13878. doi:10.1039/C7NR03824K

Zaman, A. M., Lu, Y., Romain, X., Almond, N. W., Burton, O. J., Alexander-Webber, J., et al. (2022a). Terahertz metamaterial optoelectronic modulators with GHz reconfiguration speed. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 12, 520–526. doi:10.1109/TTHZ.2022.3178875

Zaman, A. M., Saito, Y., Lu, Y., Kholid, F. N., Almond, N. W., Burton, O. J., et al. (2022b). Ultrafast modulation of a THz metamaterial/graphene array integrated device. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 091102. doi:10.1063/5.0104780

Zhang, Y., Feng, Y., and Zhao, J. (2020). Graphene-enabled tunable multifunctional metamaterial for dynamical polarization manipulation of broadband terahertz wave. Carbon 163, 244–252. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2020.03.001

Zhang, Y., Qiao, S., Liang, S., Wu, Z., Yang, Z., Feng, Z., et al. (2015). Gbps terahertz external modulator based on a composite metamaterial with a double-channel heterostructure. Nano Lett. 15, 3501–3506. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b00869

Zhang, Z., Zhong, C., Fan, F., Liu, G., and Chang, S. (2021). Terahertz polarization and chirality sensing for amino acid solution based on chiral metasurface sensor. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 330, 129315. doi:10.1016/j.snb.2020.129315

Zhao, Y., Wang, L., Zhang, Y., Qiao, S., Liang, S., Zhou, T., et al. (2019). High-speed efficient terahertz modulation based on tunable collective-individual state conversion within an active 3 nm two-dimensional electron gas metasurface. Nano Lett. 19, 7588–7597. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b01273

Keywords: terahertz, metamaterials, graphene, wireless communications, integrated modulators

Citation: Zaman AM, Lu Y, Almond NW, Burton OJ, Alexander-Webber J, Hofmann S, Mitchell T, Griffiths JDP, Beere HE, Ritchie DA and Degl’Innocenti R (2023) Versatile and active THz wave polarization modulators using metamaterial/graphene resonators. Front. Nanotechnol. 5:1057422. doi: 10.3389/fnano.2023.1057422

Received: 29 September 2022; Accepted: 06 January 2023;

Published: 31 January 2023.

Edited by:

Wenlong Gao, University of Paderborn, GermanyCopyright © 2023 Zaman, Lu, Almond, Burton, Alexander-Webber, Hofmann, Mitchell, Griffiths, Beere, Ritchie and Degl’Innocenti. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abdullah M. Zaman, YS56YW1hbjJAbGFuY2FzdGVyLmFjLnVr

Abdullah M. Zaman

Abdullah M. Zaman Yuezhen Lu

Yuezhen Lu Nikita W. Almond3

Nikita W. Almond3 Riccardo Degl’Innocenti

Riccardo Degl’Innocenti