94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mol. Neurosci., 10 May 2022

Sec. Brain Disease Mechanisms

Volume 15 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2022.896314

This article is part of the Research TopicNeuronopathic Lysosomal Storage Diseases - Specific Neuronal Characteristics and Therapeutic ApproachesView all 5 articles

Rima Rebiai1

Rima Rebiai1 Emily Rue2

Emily Rue2 Steve Zaldua1

Steve Zaldua1 Duc Nguyen1

Duc Nguyen1 Giuseppe Scesa1

Giuseppe Scesa1 Martin Jastrzebski1

Martin Jastrzebski1 Robert Foster1

Robert Foster1 Bin Wang1

Bin Wang1 Xuntian Jiang3

Xuntian Jiang3 Leon Tai1

Leon Tai1 Scott T. Brady1

Scott T. Brady1 Richard van Breemen2

Richard van Breemen2 Maria I. Givogri1

Maria I. Givogri1 Mark S. Sands3,4

Mark S. Sands3,4 Ernesto R. Bongarzone1*

Ernesto R. Bongarzone1*

Krabbe Disease (KD) is a lysosomal storage disorder characterized by the genetic deficiency of the lysosomal enzyme β-galactosyl-ceramidase (GALC). Deficit or a reduction in the activity of the GALC enzyme has been correlated with the progressive accumulation of the sphingolipid metabolite psychosine, which leads to local disruption in lipid raft architecture, diffuse demyelination, astrogliosis, and globoid cell formation. The twitcher mouse, the most used animal model, has a nonsense mutation, which limits the study of how different mutations impact the processing and activity of GALC enzyme. To partially address this, we generated two new transgenic mouse models carrying point mutations frequently found in infantile and adult forms of KD. Using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, point mutations T513M (infantile) and G41S (adult) were introduced in the murine GALC gene and stable founders were generated. We show that GALCT513M/T513M mice are short lived, have the greatest decrease in GALC activity, have sharp increases of psychosine, and rapidly progress into a severe and lethal neurological phenotype. In contrast, GALCG41S/G41S mice have normal lifespan, modest decreases of GALC, and minimal psychosine accumulation, but develop adult mild inflammatory demyelination and slight declines in coordination, motor skills, and memory. These two novel transgenic lines offer the possibility to study the mechanisms by which two distinct GALC mutations affect the trafficking of mutated GALC and modify phenotypic manifestations in early- vs adult-onset KD.

Krabbe disease (KD) is a neuropathic lysosomal storage disease caused by deficiency of the enzyme β-galactosyl-ceramidase (GALC) (Suzuki and Suzuki, 1970). Loss-of-function of GALC blocks the lysosomal hydrolysis of galactosylceramides (GalCer) and galactosylsphingosine (psychosine) (Suzuki and Suzuki, 1970; Igisu and Suzuki, 1984; Kobayashi et al., 1987; Greiner-Tollersrud and Berg, 2000/2013; Wenger, 2001). KD is primarily a childhood disease with most patients presenting neurological symptoms soon after birth. Krabbe infants can develop irritability, spasticity, seizures, muscle weakness, and a progressive loss of motor and cognitive functions (Escolar et al., 2016). Late-onset forms of the disease develop usually beyond 7–10 years of age, are less frequent, and characterized by vision problems, walking difficulties, and cognitive deterioration (Graziano and Cardile, 2015). The abnormal buildup of psychosine in the central and peripheral nervous systems is considered the main contributor to neuropathology in infantile severe forms of KD. Psychosine promotes demyelination (Taniike and Suzuki, 1994; Suzuki and Taniike, 1995; O’Sullivan and Dev, 2015), gliosis and inflammation (Giri et al., 2002), disruption of lipid rafts (White et al., 2009; Hawkins-Salsbury et al., 2013), neuropathy (Castelvetri et al., 2011, 2013; Smith et al., 2011; Cantuti-Castelvetri et al., 2012, 2015), and alterations in many signal transduction pathways (Giri et al., 2008; Castelvetri et al., 2013; Sural-Fehr et al., 2019). While the pathogenic role of psychosine in infantile KD is well documented, its contribution to neuropathology in adult forms of KD is poorly understood, primarily due to the lack of adult-onset KD animal models and mechanistic studies in patients with this form of the disease.

The most widely used KD animal model is the Twitcher (TWI) mouse, in which a naturally occurring mutation leads to degradation of GALC mRNA and absence of functional GALC protein (Duchen et al., 1980; Lee et al., 2006). The TWI mouse is a surrogate model of KD, with many hallmarks observed in human patients with infantile KD. These include toxic accumulation of psychosine, ataxic gait deficits, muscular weakness, hind limb paralysis, and are short life span. Other animal models, including the globoid cell leukodystrophy (GLD) dog, the non-human primate, and various murine lines (Bradbury et al., 2020), also largely model severe forms of KD. There are no described animal models of adult-onset KD.

To contribute to the study of neuropathic mechanisms of disease in KD, particularly those at play in adult-onset forms, we used CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing to introduce early infantile and adult-onset KD point mutations in the GALC gene. Over 140 mutations and polymorphisms in the GALC gene have been described (Wenger et al., 1997; Tappino et al., 2010; Graziano and Cardile, 2015) with the 30 kb deletion of exons 10–17 being frequently found in severe infantile forms. Previous in vitro studies showed how several point mutations in the GALC gene, found in homozygous as well as in compound heterozygous patients, can affect not only GALC activity but also its trafficking to the lysosomes (Lee et al., 2010; Shin et al., 2016; Irahara-Miyana et al., 2018). Based on this, we have selected point mutations T513M, present in many infantile patients (Wenger et al., 1997) and G41S, present in many adult patients (Lissens et al., 2007), to generate knock in mouse models. This report presents the characterization of GALCT513M/T513M and GALCG41S/G41S transgenic mice, which recapitulate early-onset (GALCT513M/T513M) and late-onset (GALCG41S/G41S) KD forms.

All procedures involving animals were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Illinois at Chicago (Protocol Number 15-101). CRISPR reagents were produced at the UIC Genome Engineering Core Facility. We use the legacy nomenclature for identifying mutations.

Two Cas9-sgRNA expression plasmids were constructed by ligating oligonucleotide duplex with the forward sequence 5′-GTCTAGCACGTAGGCGCCAC-3′ and 5′-GAACTTGGCGCAGCGTGAAG-3′ into BsaI cut addgene plasmid DR274, which was a gift from Keith Joung (Addgene plasmid #42250). The sgRNA target sequences were designed to target the GALC gene near codons G41 and T528, respectively using the MIT CRISPR design algorithm.

A single strand oligo consisting of 70 bp homology arms flanking the two desired mutations G41S and T528M was synthetized (IDT). The Sequences were as follows:

5′-TGACCGCCGCCGCGGGCTCGGCGAGCCGTGTTGCGG TGCCCTTATTGTTGTGTGCGCTGCTAGTGCCTGGTAGCG CCTACGTGCTAGACGACTCCGACGGGCTGGGCCGGGAG TTCGATGGCATCGGCGCAGTCAGCGGCGGCGGG-3′

5′-GCTCCGAATTTTGCTGATCAGACTGGCGTGTTTGAGT ACTACATGAATAATGAAGACCGTGAGCAACGCTTCATGC TGCGCCAAGTTCTCAACCAACGACCTATTACCTGGGCTG CAGACGCTTCCAGCACAATCAGTGTT-3′

In vitro transcription of RNA was performed using the MEGAshortscript™ T7 Transcription Kit. RNA function was validated with an in vitro cas9 Digestion assay in which the target region DNA was amplified from black 6 mouse genomic DNA and allowed to incubate with cas9 nuclease protein from NEB (M0386T) and the transcribed Guide RNA. Mutations were confirmed by next generation sequencing before zygote injections.

Injection of CRISPR reagents was performed at University of Chicago Transgenic Core following the protocol as described (Wang et al., 2013). Pups were genotyped at UIC using a next generation amplicon sequencing technique which is able to quantify the efficiency of the CRISPR edits in each individual mouse (Cong et al., 2013; Hsu et al., 2013).

Key: Gray is exon sequence. Bold is sequence where sgRNA binds. Double strand break occurs at ^^^^^^.

5′TAATTACACGCAGAGACCGGTCCCGCCTCTTTGACACA GAAGTGACAAGGCAAAGCTCGCTCAACCAGCCCCCCAC CCCGCCCCCCCAGCTCAACACAACAGCGGCTGCGCGGA CAGCCCGCAGCCCTCACTTAAGATGGCGAAAGCTTCCT CAGCCGCCCGCTCTTCTTCCTCAGGGAGGCGATCGGGC CCGCCTCCCCGGGCGCCACAGTCGCGTGACCCGCACAA TGGCTAACAGCCAACCTAAGGCTTCCCAGCAACGCCAA GCAAAAGTCATGACCGCCGCCGCGGGCTCGGCGAGCC GTGTTGCGGTGCCCTTATTGTTGTGTGCGCTGCTAGTG CCCGGTG^^^^^^GCGCCTACGTGCTAGACGACTCCGACG GGCTGGGCCGGGAGTTCGATGGCATCGGCGCAGTCAG CGGCGGCGGGGTGAGCGCGGGCTGGCGGGAGGCAGGA GTGCGGTGCGGCGCAGGGACCGCAGGGACCGCAGGGA CCGCCGGGGCCGCCCCCTCCCACAAGCCCCCGCGGCGT TGCCGGGCGAGCGCACGCCGCTTCCCCGCGCGCCGGG GTGAGATGAACCCGGGCTGGCGGTTAGATTGCAATGGG GAGCCAGGCGTCTCGAGGGGACAGGCGTCTGCTGCAG TCAAGTGGCCCGGGCTCGAGGGAGCCCTCGTTCTGGAT CGCCGGC-3′

5′-TGACCGCCGCCGCGGGCTCGGCGAGCCGTGTTGCGG TGCCCTTATTGTTGTGTGCGCTGCTAGTGCCtGGTaGCGC CTACGTGCTAGACGACTCCGACGGGCTGGGCCGGGAGTT CGATGGCATCGGCGCAGTCAGCGGCGGCGGG-3′

KasI site was destroyed when the mutation was made, which can be used to screen mice. PAM site was mutated to avoid cutting donor template by guide (Silent Mutation P = CCC -> P = CCt).

5′-TACAGGCATCTGGTCAATTATTTGGATATATTTCCAAA TACATCACACACACACACACACACACACCCTAAACTTTG TTTCTAAGTATTATGTTTTATAAATTAGTCAAGTATTTCA CAGTGTATCACCGATATCAGAAAGGAGAGATCTGGTAAG GGCTTGCTAATCAGCCGCTGAGATACTAAGTGGAGGACT TACTTTTTGTGTTCTGAACAGAGTACCCACTTTTTAGTG AAGCTCCGAATTTTGCTGATCAGACTGGCGTGTTTGAGT ACTACATGAATAATGAAGACCGTGAGCACCGCTT^^^^^^C ACGCTGCGCCAAGTTCTCAACCAACGACCTATTACCTG GGCTGCAGACGCTTCCAGCACAATCAGTGTTATAGGCGA TCACCACTGGTGTGTGAGAGATGCCCTCAGTGTATACGC TTGCGATTTGGGGTACATTCTGAGTGAAGGGATTCCAA TAGGCCGTCTCCTGTCAAGAACCTAATAGGTGGTGGGTC AGAATTATGTGACCTCAAGTGATCAAATTAGCTTCCATG TCCTCCCTTTAGATTATGCCAGTTTGAAGATAATTGCGG TCAGAGAAATCCAACTTTAATGGGAAAATTGAGG-3′

5′GCTCCGAATTTTGCTGATCAGACTGGCGTGTTTGAGT ACTACATGAATAATGAAGACCGTGAGCAaCGCTTCAtGCT GCGCCAAGTTCTCAACCAACGACCTATTACCTGGGCTGC AGACGCTTCCAGCACAATCAGTGTT-3′

SduI restriction enzyme site was created when the mutation was made, which can be used to screen mice. PAM site was mutated to avoid cutting donor template by guide (Silent mutation H = CAC –> H = CAa).

Total brain tissues were homogenized and prepared in RIPA buffer supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitors. Protein concentration analysis was determined with a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were prepared with 6x Laemmli buffer and lysis buffer. Twenty five micrograms of protein were loaded per lane and separated by 12% SDS-PAGE under denaturing conditions with a mini-Protean II gel electrophoresis apparatus and included a Precision Plus Standard Protein Dual color (Biorad) to enable identification of band size. Separated proteins were then transferred to a PVDF membrane. Non-specific binding sites on the membrane were blocked with 5% skim milk in TBS-Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies against GALC (in house produced monoclonal mouse IgG, 1:100 dilution), myelin proteolipids (PLP, a kind gift from Robert Skoff, Wayne University, rabbit IgG, 1:2,000 dilution), myelin basic proteins (MBP, a kind gift from Anthony Campagnoni, UCLA; rabbit IgG, 1:500 dilutiom), Actin (Sigma-Aldrich, rabbit, 1:2,000), LAMP1, LAMP2 (Iowa Hybridoma Cell Bank, mouse IgG, 1:500) and LC3 (Cell Signal, rabbit IgG, 1:500) were prepared in 5% milk in TBS/Tween 20 and incubated at 4°C overnight. Membranes were washed in TBST (0.05%) 3× for 5 mins and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with secondary antibody. Secondary antibodies were horseradish peroxidase-conjugated (HRP), diluted in 5% milk TBST, and then developed using the Odyssey CLx apparatus (Li-Cor). Protein band densities were quantified using ImageJ and normalized by the housekeeping protein GAPDH.

Mice were perfused with PBS under 5% isoflurane anesthesia followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) before tissue was removed and processed for cryosectioning. Cryosections of 30 μm thickness were cut for immunohistochemistry (IHC). The sections were blocked free-floating with blocking buffer (0.3 M glycine, 1% BSA, 5% normal donkey serum, 5% normal goat serum, 0.30% Triton X-100, TBS) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by 24–72 h incubation at 4°C with primary antibodies in blocking solution. After washing with TBS, tissue was incubated with secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h in blocking buffer and washed again in TBS. Tissue was mounted with Prolong Gold antifade reagent (cat# P36931 Life technologies, Eugene, OR, United States) and visualized using confocal microscopy (Leica TCS SPE, Wetzlar, Germany). Primary antibodies used included: GALC (in house produced mouse IgG monoclonal, 1:100 dilution), PLP (a kind gift from Robert Skoff, Wayne State Univ, rabbit IgG 1:2,000 dilution), GFAP (Millipore, Mouse, 1:1,000), IBA-1 (Millipore, rabbit IgG 1:300), LAMP1 and LAMP2 (Iowa Hybridoma Cell Bank, mouse IgG, 1:500). Secondary antibodies used included: AlexaFluor 488 anti-Mouse (cat#A-11029, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, 1:500 dilution) and Dylight 549 anti-rat (cat# 112-506-068 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 1:500 dilution). Counterstaining for cell nuclei was performed with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, cat#D1306, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, 1: 3,000 dilutions in TBS). Immunofluorescent complexes were visualized using a Leica TCS SPE confocal laser with an upright DM5500Q Microscope (Leica Biosystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL, United States). Counting of GALC/Lamp double positive puncta were done by confocal microscopy with an immersion oil 63x objective on four random fields (n = 3 mice/condition) and Image J-Graph Pad post hoc analyses.

Our methods have been described in detail in Marshall et al. (2018). To summarize, a Vibra-cell ultrasonic liquid processor model#VCX 130 (Sonics and Materials Inc., Newton, CT, United States) was used to homogenize fresh frozen tissue in water. Fluorescent GALC substrate (6HMU-beta-D-galactoside; Moscerdam Substrates) was incubated with tissue lysates (20 μg) for 17 h at 37°C before the reaction was stopped. Fluorescence was measured to assess enzyme activity using a Beckmann Coulter DTX 880 multimode detector (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, United States) through excitation/emission wavelengths of 385 and 450 nm, respectively. Methanol-acetic acid solution (0.5% Acetic Acid in methanol) was used to extract psychosine from tissue homogenates (brain and spinal cord lysates) (200 μg). Psychosine content was then determined by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). To differentiate glucosylsphingosine vs psychosine, the following protocol was used: mouse brains were homogenized in 2% CHAPS solution (4 mL/g brain). Protein precipitation was used to extract psychosine from 50 μL of homogenate in the presence of d5-psychosine and d5-glucosylsphingosine as internal standard for psychosine and glucosylsphingosine, respectively. Quality control (QC) samples were prepared by pooling 10% of extracts from study samples. The QC samples were used to monitor the instrument performance and injected every five study samples. Analysis of psychosine and glucosylsphingosine was performed with a Shimadzu 20AD HPLC system coupled to a 4000QTrap mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ion source and operated in positive multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode (Sidhu et al., 2018). Data processing was conducted with Analyst 1.6.3 (Applied Biosystems). The relative quantification of psychosine and the data were reported as the peak area ratios of the psychosine to its internal standard.

Monoclonal mouse anti-GALC antibodies were generated with the goal to recognize full-length human and mouse GALC proteins in tissues and protein extracts. Monoclonals were prepared following procedures described previously (Pfister et al., 1989). In short, mice were immunized subcutaneously two times with 25 μg of a keyhole limpet hemocyanin-conjugated synthetic peptide encompassing aminoacids 469–498 of human GALC (which shares >90% homology with the mouse protein sequence), mixed with Gerbu adjuvant. Before 3 days of fusion, the mice received an intravenous injection with 10 μg of antigen together with adjuvant. Spleen and lymph node cells were fused with SP2 myeloma cells to generate hybridomas. Positive clones were selected and cloned by repeated screening against the GALC protein using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The performance and specificity of several antibody clones were validated using western blot and immunofluorescence microscopy against transfected cells.

The clinical conditions of the mice were assessed and quantified using an expanded disease severity score (DSS) based on our previous DSS system (Marshall et al., 2018). The new scoring system takes into consideration the following general categories: physical characteristics (weight loss, tremor, and kyphosis), locomotion, wire hanging, and cerebellar function (hindlimb clasping, ledge balance). Each individual test is scored as follows: weight loss: compared to average of previous 2 weeks score of 0: 0.5 loss or less (including weight gain); score of 0.5: 0.5–1 g loss; score 1: 1–1.5 g loss; score 1.5: 1.5–2 g loss; score 2: >2 g loss. Tremor score 0: no tremor; score; score 1: mild tremor; score 2: severe tremor. Kyphosis score 0: no kyphosis in any condition; score 1: kyphosis when hunched over; score 2: kyphosis when lying flat. Locomotion score 0: normal; score 0.5: awkward gait; score 1: waddling; score 1.5: one leg paralyzed; score 2: both legs paralyzed. Wire hanging score 0: >45 s; score 0.5: 31–45 s; score 1: 16–30 s; score 1.5: 5–15 s; score 2: 0–5 s. Hindlimb clasping score 0: none; score 0.5: one limb partial (under 5 s out of 10); score 1: two limbs partial or 1 limb full (over 5 s out of 10); score 2: both limbs full. Ledge balance score 0: no problems; score 0.5: minor problem (mouse is reaching down and slips); score 1: minor fall (mouse is starting to move down and falls); score 2: fall from ledge with no attempt to get down.

Latencies to fall in the rotarod below normal values were considered pathognomonic and measured as described (Marshall et al., 2018). Motor activity in the open field test was evaluated as described (Kan et al., 2016; Nelvagal et al., 2021). Mice were tested for anxiety using the light/dark box (Malmberg-Aiello et al., 2002; Bourin and Hascoet, 2003). Spatial memory was evaluated using the Barnes and Morris water maze tests as described (Patil et al., 2009).

Neural precursors were isolated from the subventricular zone from P4 to 6 mice and stable self-proliferating cultures were established as described (Felling et al., 2006; Givogri et al., 2008). Cells were differentiated on poly-lysine coated coverslips in defined medium containing 1% FBS for 7 days. Half of the coverslips were replenished with complete medium containing FBS and the other half with FBS-depleted medium. Starvation (Mejlvang et al., 2018) was then maintained for 4 h before cells were washed and fixed in 1.5% PFA/PBS for 30 min. Cells were processed for double immunohistochemistry using anti-LAMP-2 (see above) and anti-LC3 (see above) antibodies. After mounting and nuclear staining using DAPI, confocal images were taken using a 63x oil objective. Double LAMP-2+/LC3+ (i.e., colocalization and yellow fluorescence) and single LAMP-2+ puncta were counted in 15–20 cells per condition.

Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, United States) was used to prepare graphs and statistics. One-way ANOVA with Gaussian distribution was performed to analyze data with more than two means, with two-sided p-values < 0.05 considered significant. T-tests were also performed for the comparisons between two means, with two-sided p < 0.05 considered significant. Graphs represent the mean of independent measurements (with sample sizes ranging n = 6–12) shown with errors bars representing standard error of the mean.

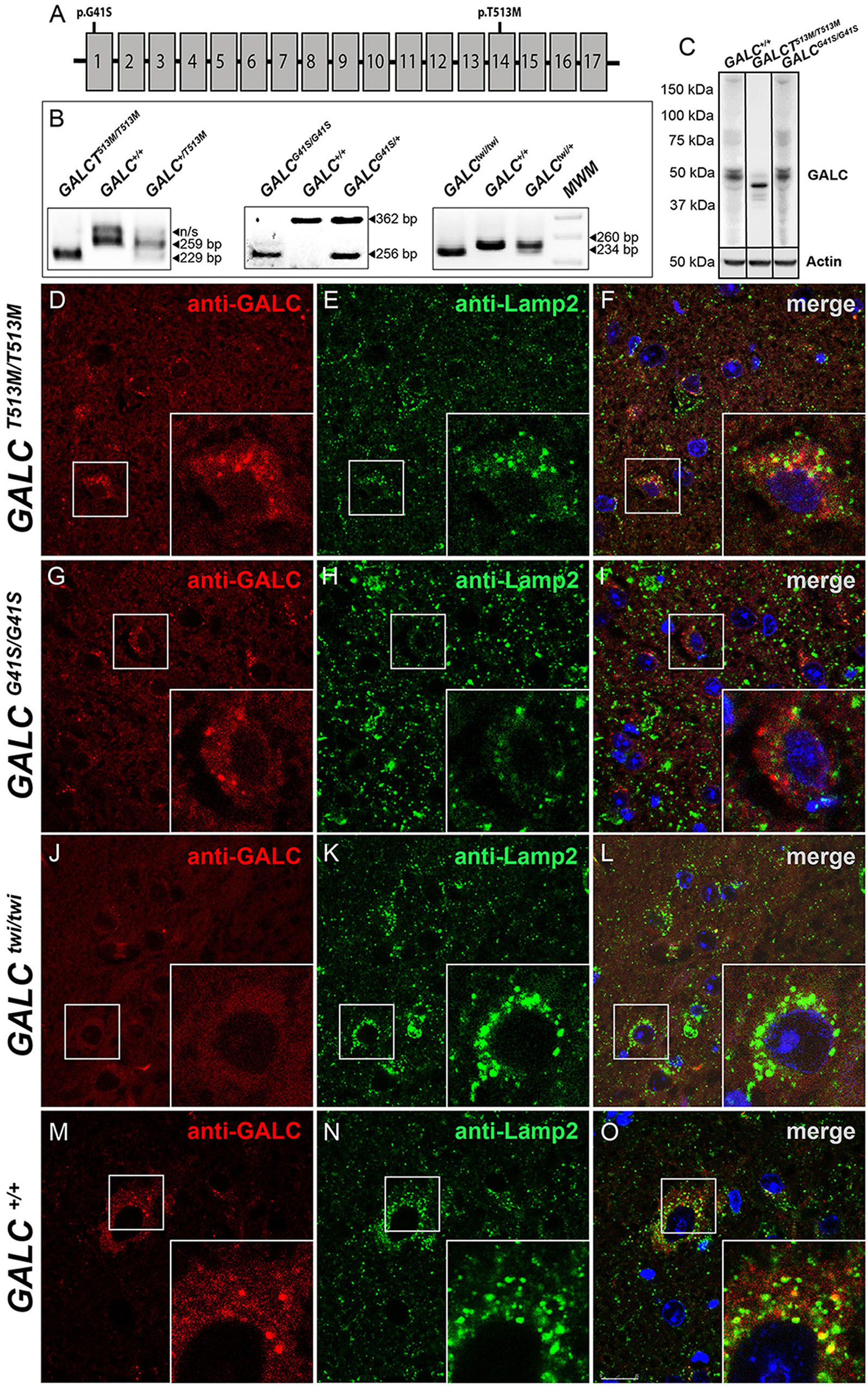

The presence of the GALCT513M/T513M and GALCG41S/G41S mutations (Figure 1A) was confirmed by PCR analysis from total genomic DNA (Figure 1B). Western blotting analysis of protein extracts prepared from P25 brains indicated that mutated GALC proteins are clearly expressed in both GALCT513M/T513 and GALCG41S/G41S mutants, although the GALCT513M protein appears to have a lower molecular weight (Figure 1C), which is likely indicating abnormal glycosylation of the mutated protein. Studies have previously reported that many point mutations in the GALC protein alter the transport to the lysosomes (Lee et al., 2010; Shin et al., 2016; Irahara-Miyana et al., 2018). To examine whether this occurs in GALCT513M/T513 and GALCG41S/G41S mutants, immunofluorescence confocal microscopy was used to determine if the mutated GALC protein colocalized with the lysosomal marker LAMP-2. Brain sections of both mutants were analyzed at postnatal day 25 (P25), using aged-matched Twi and WT as references of absence and normal presence of GALC protein, respectively (Figures 1D–O). Remarkably, the analysis showed reduced co-staining for GALCT513M and GALCG41S mutant proteins with Lamp2 (Figures 1F,I), suggesting partial mislocalization with lysosomes. As expected, TWI mutants had no immunodetectable GALC protein (Figure 1L) in comparison with wild-type controls (Figure 1O). Quantification of double positive GALC/LAMP-2 puncta showed ∼70% less GALCT513M/T513M protein located in lysosomes (Figure 2A). Interestingly, association of GALCG41S/G41S protein with LAMP-2+ puncta was reduced at early times points (P25) but not in older mice (P120, Figure 2A).

Figure 1. Lysosomal localization of mutated GALC protein is reduced in GALCT513M/T513M and GALCG41S/G41S mice. (A) Localization of the G41S and T513M mutations within the GALC gene. (B) PCR-based identification of mutations in GALCT513M/T513M and GALCG41S/G41S. Mutation in GALCtwi/twi and GALC+/+ were used as references. (C) Western blot analysis of GALC protein lysates prepared from P40 brains. Actin was used for loading control. (D–O) Immunohistochemistry on cryosections of P25 brain tissue showing colocalization of GALC protein (red) with LAMP-2 (green) in lysosomes of GALCT513M/T513M, GALCG41S/G41S, GALCtwi/twi, and GALC+/+ mice. DAPI, blue. Scale bar = 50 μm.

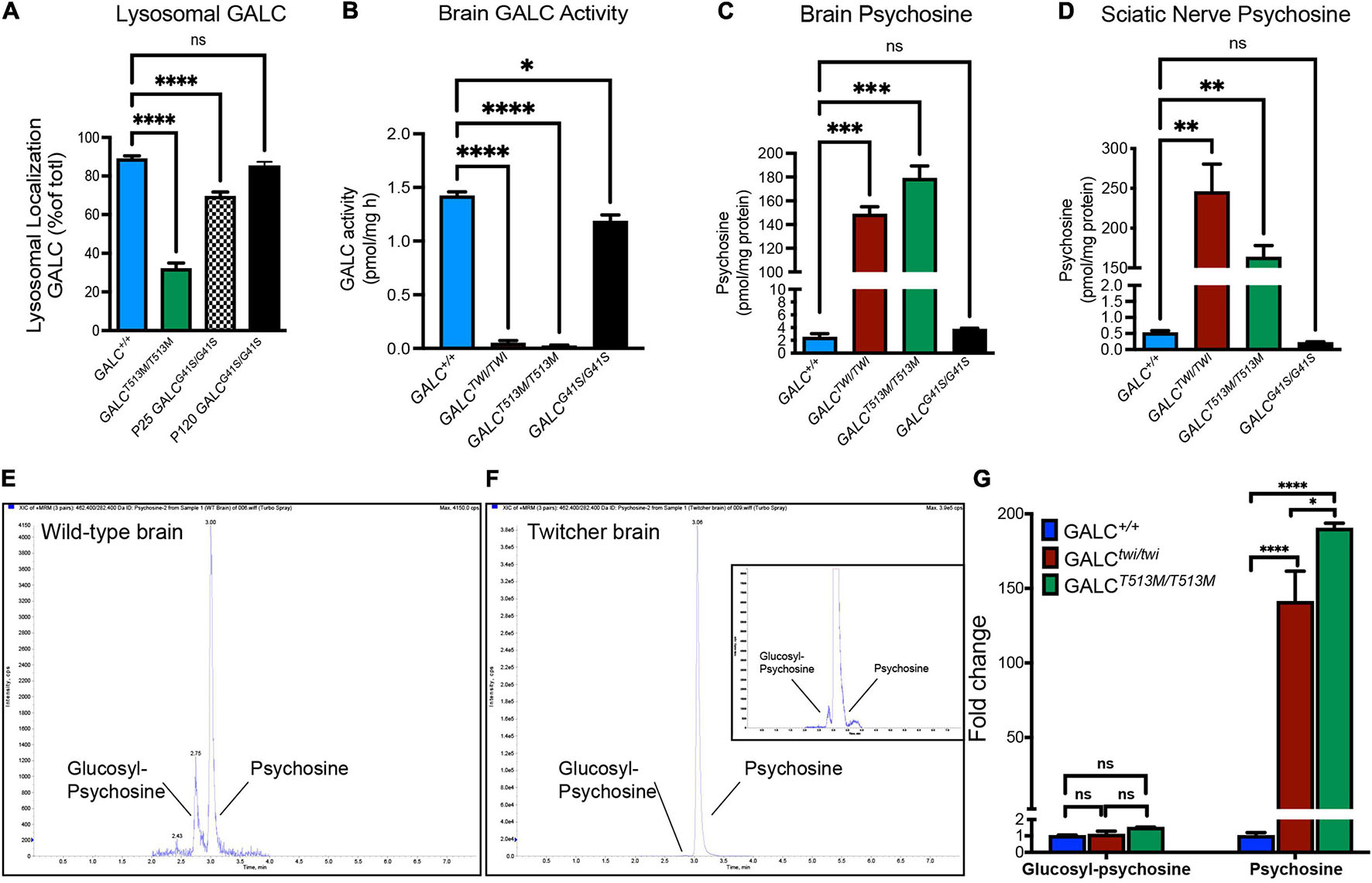

Figure 2. Analysis of mutated GALC activity and psychosine production in GALCT513M/T513M and GALCG41S/G41S mice. (A) Co-localization of GALC in lysosomes was measured by confocal analysis of brain cortices of each genotype. Data represent the fraction (as%) of total GALC+ puncta that was co-stained with Lamp2+. Counts were done on random areas of the brain cortex. (B) GALC activity was analyzed fluorometrically in protein extracts from P40 brains. (C,D) Psychosine levels in P40 brains (C) and sciatic nerve (D) were measured by LC-MS-MS. (E–G) Chromatograms of glucosylsphingosine and psychosine in WT (E) and twitcher mouse brains (F) were detected by mass spectrometry. The glucosylsphingosine and psychosine were measured as the fold changes in the brain of Twi and GALCT513M/T513M mutants versus WT (G). Data represent the mean ± SEM of 4–6 mice/genotype, analyzed by ANOVA/Tukey’s post hoc test *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.001.

Next, we assessed how GALCT513M/T513 and GALCG41S/G41S mutations impacted enzyme activity. As expected for an infantile mutation, mice with the GALCT513M/T513 mutation have undetectable enzyme activity in the brain, similar to levels in the TWI mouse (Figure 2B). In contrast, analysis of GALC activity in the brain of GALCG41S/G41S mice showed a small reduction in enzyme activity (Figure 2B).

The loss of function of GALC enzyme in KD results in the progressive accumulation of psychosine (Igisu and Suzuki, 1984; White et al., 2009; Spassieva and Bieberich, 2016). To examine how these mutations impacted the accumulation of psychosine, lipid extracts from P40 GALCT513M/T513, GALCG41S/G41S, and TWI brain (Figure 2C) and sciatic nerves (Figure 2D) were analyzed by LC-MS-MS. Consistent with the lack of GALC activity, both GALCT513M/T513M and TWI tissues have the highest levels of psychosine (Figures 2C,D). In contrast, GALCG41S/G41S mice showed psychosine levels similar to wild type in both central and peripheral nerve tissue. To confirm the accumulation of psychosine in GALCT513M/T513 mice, we measured the relative levels of glucosylsphingosine and psychosine, using a LC-MS/MS protocol to completely separate the isomeric glucosylsphingosine and psychosine (glucosylsphingosine and psychosine have the same m/z 462) (Figure 2E). As expected, both TWI and GALCT513M/T513 mutants accumulate high levels of psychosine, while glucosylsphingosine is only found at trace levels (Figures 2E,F). Figure 2G shows the relative abundance of psychosine and glucosylsphingosine in TWI and GALCT513M/T513 brains versus WT brains, confirming that only psychosine is accumulated in both mutants. Interestingly, psychosine in TWI is higher than in GALCT513M/T513 brains.

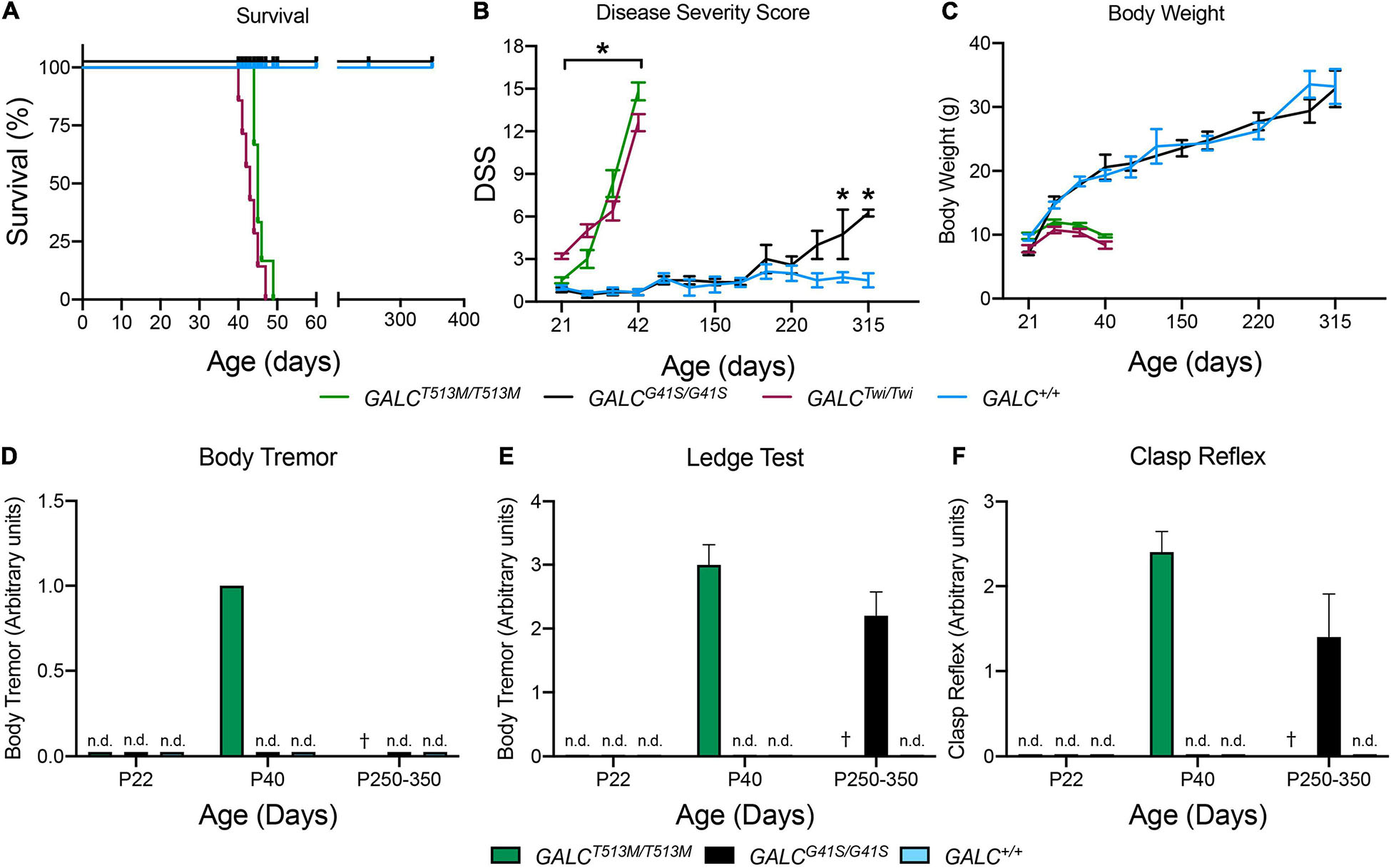

GALCT513M/T513 mice have a median survival of 46 vs 42 days in Twi mice (Figure 3A). The maximal survival of GALCT513M/T513 was 49 ± 3 days. In contrast, GALCG41S/G41S mice have no significant decrease in their survival, with all mutants reaching adult age similar to WT mice (Figure 3A). Expectedly, GALCT513M/T513 mice and GALCG41S/G41S mice show remarkably different clinical signs of neurological disease. Using our established DSS system (Marshall et al., 2018), GALCT513M/T513 mice have an onset with significant increases in DSS at postnatal day 24 (P24 ± 2 days). This is slightly delayed in comparison with Twi mice, which show clinical onset at P22 ± 2 days (Figure 3B). GALCT513M/T513 mice follow a typical rapid and progressive increase in DSS, similar to TWI mice (Figure 3B). In contrast, GALCG41S/G41S mice show DSS values comparable to WT for most of their life until approximately 250 days, when minor but significant motor deficits were measured (Figure 3B). In terms of body weight, GALCT513M/T513 mice and GALCG41S/G41S mice showed expected decreases and normal gains, respectively (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Clinical analysis of GALCT513M/T513M and GALCG41S/G41S mice. Survival (A), disease severity score (DSS) (B), body weight (C), onset of body tremor (D), onset of errors on the ledge test (E), and onset of affected clasp reflex (F) were measured for each genotype. n.d., non-detected; †, dead. n = 6–8 mice/genotype/time point. *p < 0.05.

As expected for a severe demyelinating phenotype, GALCT513M/T513 mice showed increased tremor by P40 (Figure 3D). GALCG41S/G41S mice did not have detectable tremor at any time point in our study (Figure 3D). Assessment in the ledge test showed an early deficit in GALCT513M/T513 mice at ∼P40 (Figure 3E). Interestingly, GALCG41S/G41S mice did not have measurable deficits in this test until they reached adulthood (P250–350) (Figure 3E). Similarly, a positive clasping test was detected in ∼P40 GALCT513M/T513 mice and only in aged (>P250) GALCG41S/G41S mice (Figure 3F).

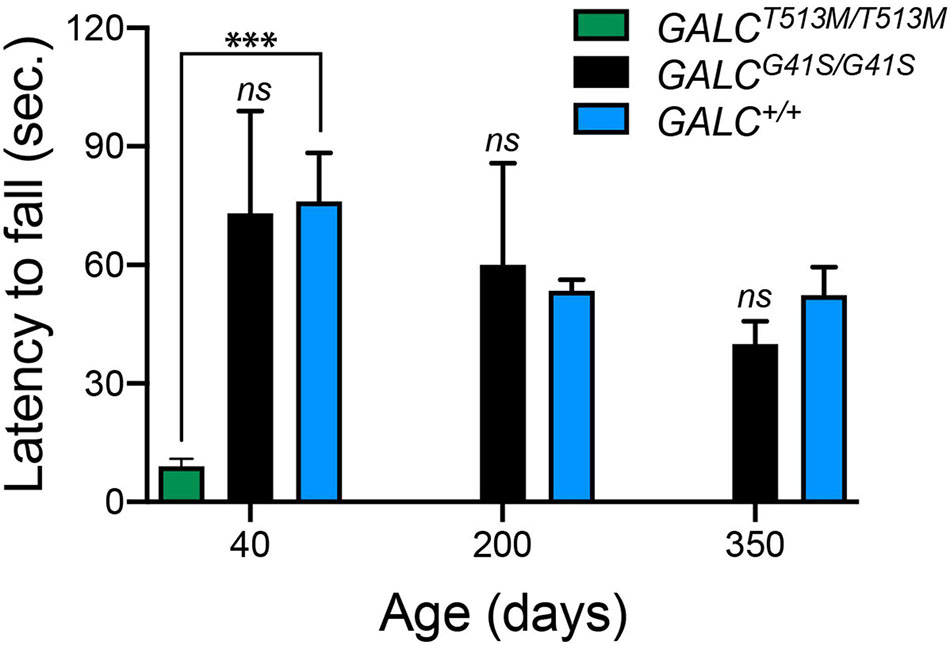

To further evaluate motor performance and balance, GALCT513M/T513 and GALCG41S/G41S mice were trained using an accelerating rotarod test. As expected for animals with a severe neurological phenotype, P40 GALCT513M/T513 mice showed a significantly impaired capacity to remain in the rotarod (Figure 4). In contrast, GALCG41S/G41S mice had no significant deficits in their latency to fall from the rod either when young (P40) or older (P200 and P350) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. GALCT513M/T513M but not GALCG41S/G41S mice exhibit rotarod deficits. Rotarod performance was significantly lower in GALCT513M/T513M mutants. Results are expressed as latency to fall in seconds (sec). Mice were tested at P40, P200, and P350. Data represent the mean + SEM of n = 6/group, analyzed by ANOVA/Tukey’s post hoc test ***p < 0.01.

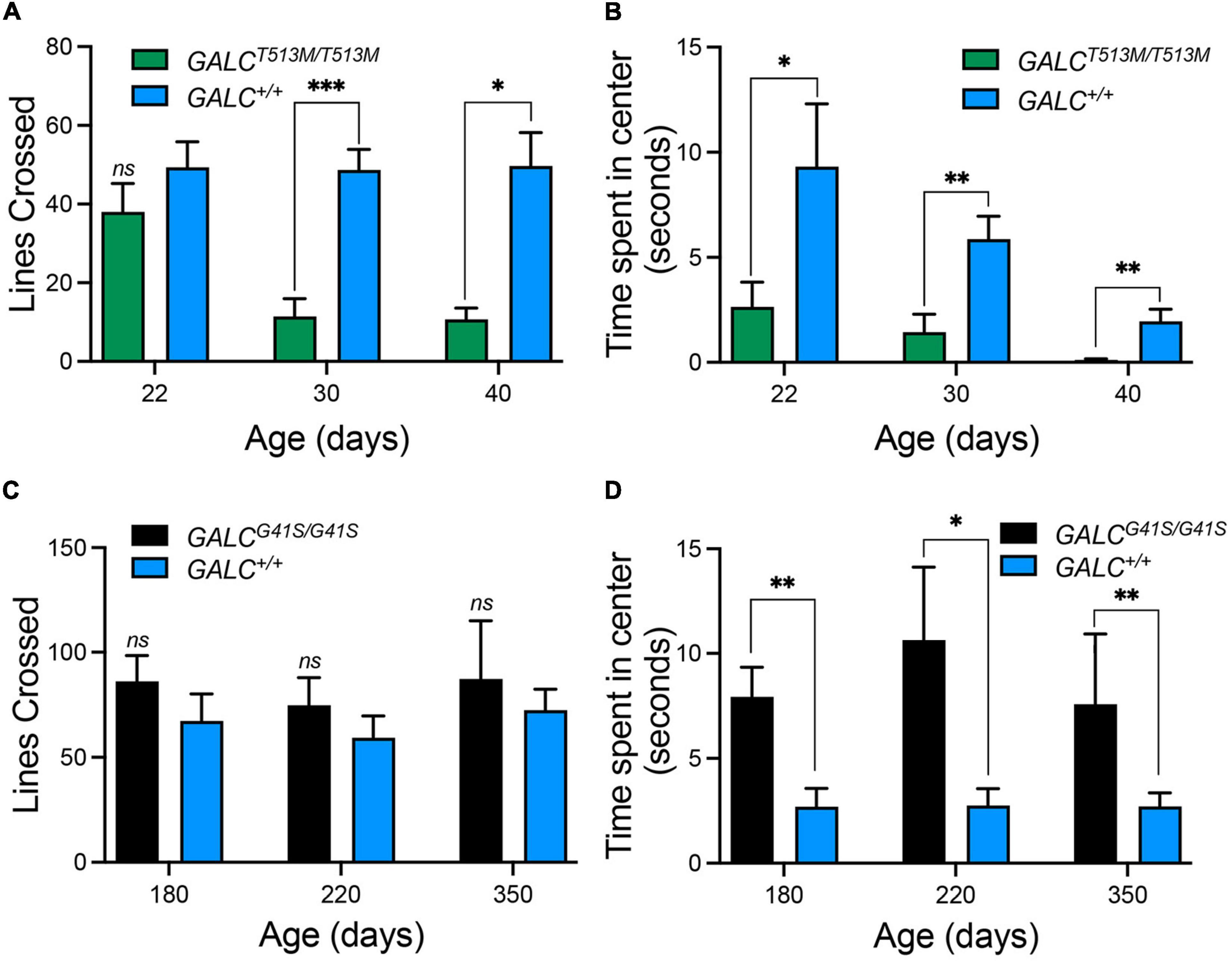

Next, we tested both mutants in the open field locomotor test. Line crosses and time spent in center were both calculated to examine motor behavior and anxiety. Figure 5A shows that GALCT513M/T513 mice display a progressive decline in mobility starting at P30. Exploratory and anxiety behaviors, measured as the time that the animal spent in the center quadrant of the open field, showed the expected reduced time when GALCT513M/T513 mice became less mobile at P30 and P40 (Figure 5B). However, younger P22 GALCT513M/T513 mice, which showed no obvious mobility limitations, also displayed a reduced time spent in the center quadrant. This suggests early signs of decreased exploratory behavior and likely, elevated anxiety in GALCT513M/T513 mice compared with wild type mice (Figure 5B). In contrast, GALCG41S/G41S mice showed similar motor activities as per line crossing to wild type mice (Figure 5C). Interestingly, GALCG41S/G41S mice showed higher time spent in the center quadrant at each time point of the study (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. Distinct exploratory behavior and anxiety-type responses exhibited by GALCT513M/T513M but not GALCG41S/G41S mice in the open field test. (A) Progressive loss of motor exploratory activity (measured as number of lines crossed) was observed in GALCT513M/T513M mice, starting at 30 days. (B) Signs of increased anxiety type responses (measured as time spent in the center quadrant) in GALCT513M/T513M mice were detected immediately after weaning. (C) GALCG41S/G41S mice exhibited normal motor activity at all time points. (D) GALCG41S/G41S mice showed signs of reduced anxiety-type behavior. Data represent the mean + SEM of n = 6–8/group, analyzed by ANOVA/Tukey’s post hoc test *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

The open field test showed increased exploratory behaviors of GALCG41S/G41S mice. We wanted to investigate this in more detail by testing their response to the dark-light box. GALCG41S/G41S mice were tested at 180, 220, and 350 days of age showing similar average time spent exploring the dark compartment, although younger P180 GALCG41S/G41S mice spent less time in the darkness (Figure 6A). Remarkably, when the latency to enter the dark box was measured, GALCG41S/G41S mice showed increased times spent in the lighted box at every time point (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Cognitive capacity and spatial learning performance are slightly impaired in GALCG41S/G41S mice. (A,B) Activity of GALCG41S/G41S mice in the dark-light box showed slightly less time spent exploring the dark compartment in younger (P180) vs aged older (P220, P350), with an increased latency to enter in the dark box at all time points. Data represent the mean + SEM of n = 4–6/group, analyzed by ANOVA/Tukey’s post hoc test *p < 0.05. (C–E) The Barnes maze test showed GALCG41S/G41S and GALCG41S/+ mice increased times to identify the target hole (C), with no significant differences in the percentage of pokes in target (D) vs opposite (E) holes. Data represent the mean + SEM of n = 6/group, analyzed by ANOVA/Tukey’s post hoc test *p < 0.05. (F–H) The Morris water maze test measured no significant differences in the escape latency (F) and annulus crossings (G) but significant decreases in the number of platform crossings in both GALCG41S/G41S and GALCG41S/+ mice. Data represent the mean + SEM of n = 6–8/group, analyzed by ANOVA/Tukey’s post hoc test **p < 0.01.

To assess whether spatial learning and memory functions are impacted in GALCG41S/G41S mice, mice were tested in the Barnes and Water Morris maze tests. Interestingly, both homozygous and heterozygous mice for the GALCG41S/G41S mutation showed higher latencies to find their target in the Barnes test, in contrast to wild type littermates which rapidly learned where the target was (Figure 6C). This might be supported by the lack of significant differences in poking the target (Figure 6D) or opposite (Figure 6E) holes. While there were no significant differences in the percentage of pokes in target and opposite holes, all genotypes spent more time exploring the target hole (∼20%) than the opposite hole (∼5%) (Figures 6D,E). When tested in the Morris water maze, all genotypes showed similar learning capacity to find the platform (Figure 6F). Likewise, no significant differences were observed in the number of annulus crossings between GALCG41S/G41S and wild-type mice (Figure 6G). However, both homozygous GALCG41S/G41S and heterozygous GALCG41S/+ mice showed a significant decrease in the number of crossings over the same exact location on the platform compared with wild-type controls (Figure 6H).

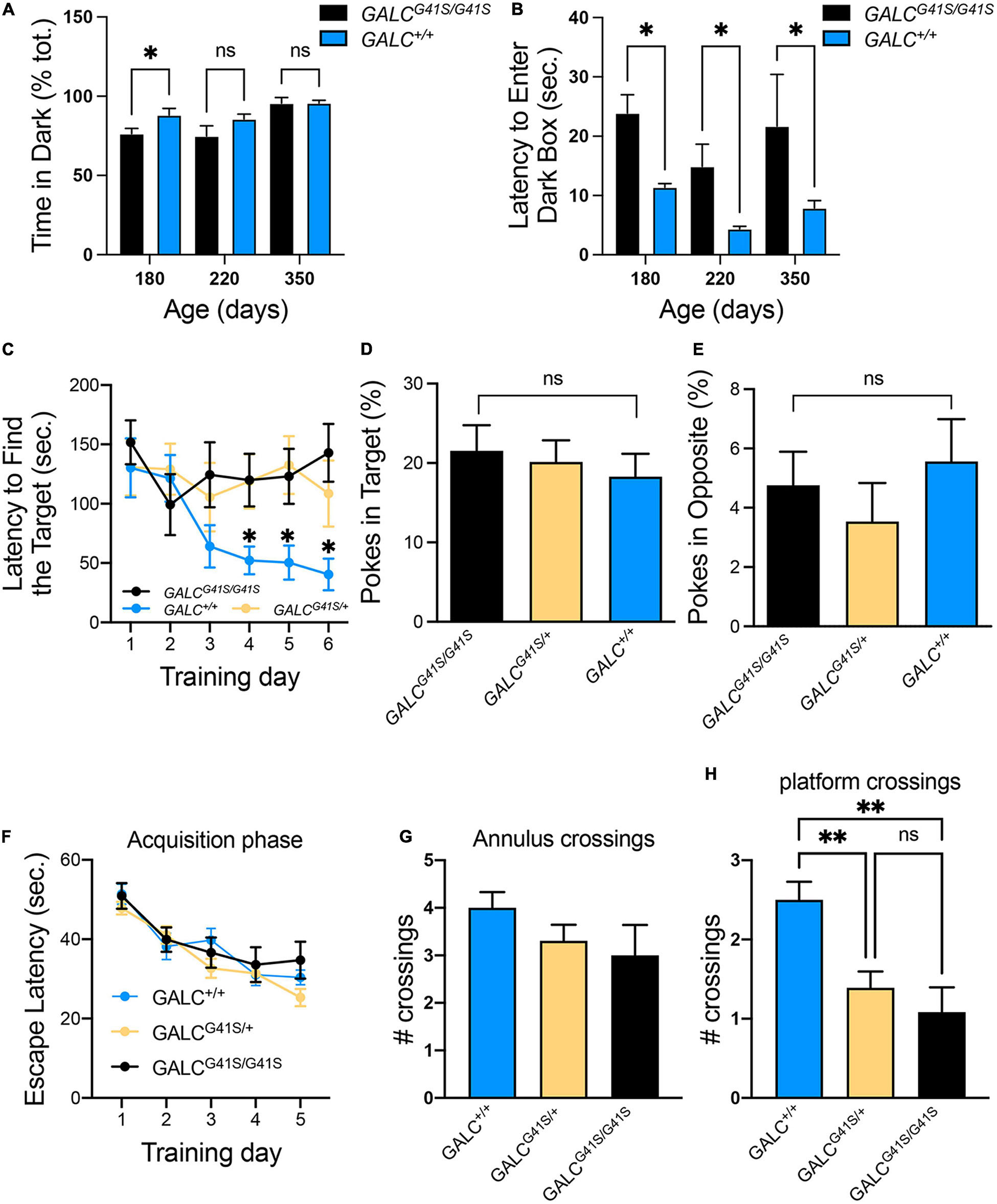

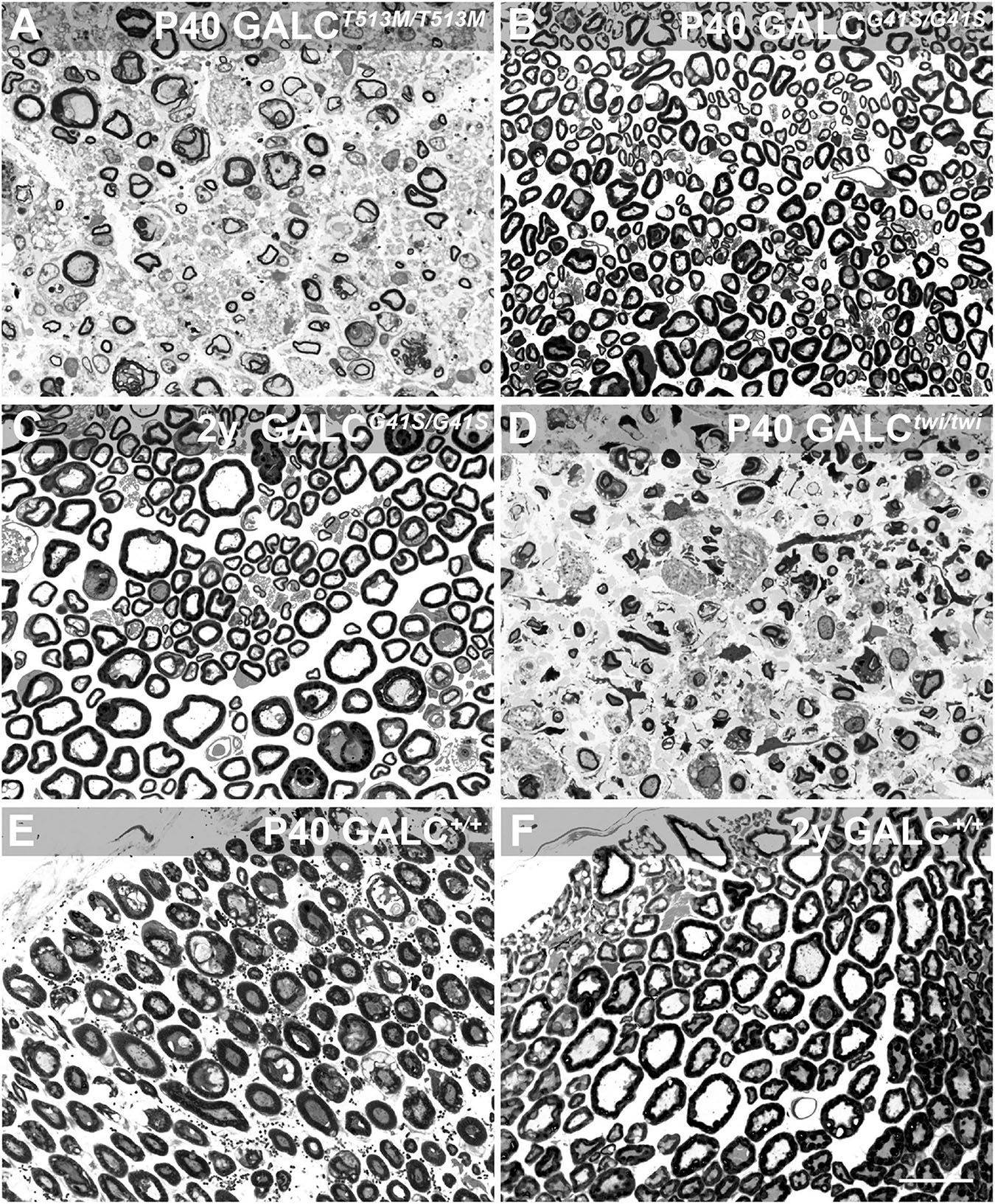

To examine central myelination, brain cryosections were stained for myelin proteolipids (PLP). We focused on the corpus callosum, a structure that is heavily demyelinated in the TWI brain at P40 (Figure 7E, compare with control levels in Figure 7F). GALCT513M/T513M and GALCG41S/G41S mice showed distinct patterns of central demyelination. GALCT513M/T513M mice displayed the expected rapid and severe demyelination for a short lived leukodystrophic condition at P20 (Figure 7A) and P40 (Figure 7B) brains. Interestingly, demyelination appeared patchy in contrast to more global and diffuse damage observed in TWI brains. In contrast, while the level of PLP staining seemed undisturbed in P40 GALCG41S/G41S mice (Figure 7C), it clearly showed signs of patchy demyelination by 2 years (Figure 7D). Examination at intermediate time points (P180 and P350) showed PLP staining comparable to WT (data not shown), suggesting that central demyelination is a late event in GALCG41S/G41S mice. Loss of myelin was confirmed by measuring PLP (Figures 7G,I) and MBP (Figures 7H,J) levels on semiquatitative western blotting from P40 GALCT513M/T513M and 2y GALCG41S/G41S total brain extracts.

Figure 7. GALCT513M/T513M and GALCG41S/G41S mice exhibit signs of early and late central demyelination. Confocal microscopy after immunohistochemistry using anti-PLP detected reductions of PLP (in green) expression in the corpus callosum of GALCT513M/T513M mice at P20 (A) and P40 (B), which are comparable to demyelination observed in P40 TWI (E). In contrast, demyelination (indicated as a reduction of PLP immunofluorescence) was less evident at P40 (C), and patchy in the 2 year old (D) GALCG41S/G41S corpus callosum. (F) shows PLP staining in P40 GALC+/+ corpus callosum. Blue: DAPI. Bar = 50 mm. (G–J) Semiquantitation of myelin PLP and MBP levels (by western blotting) in whole brain extracts. Data represent the mean + SEM of n = 4–6/group, analyzed by ANOVA/Tukey’s post hoc test *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

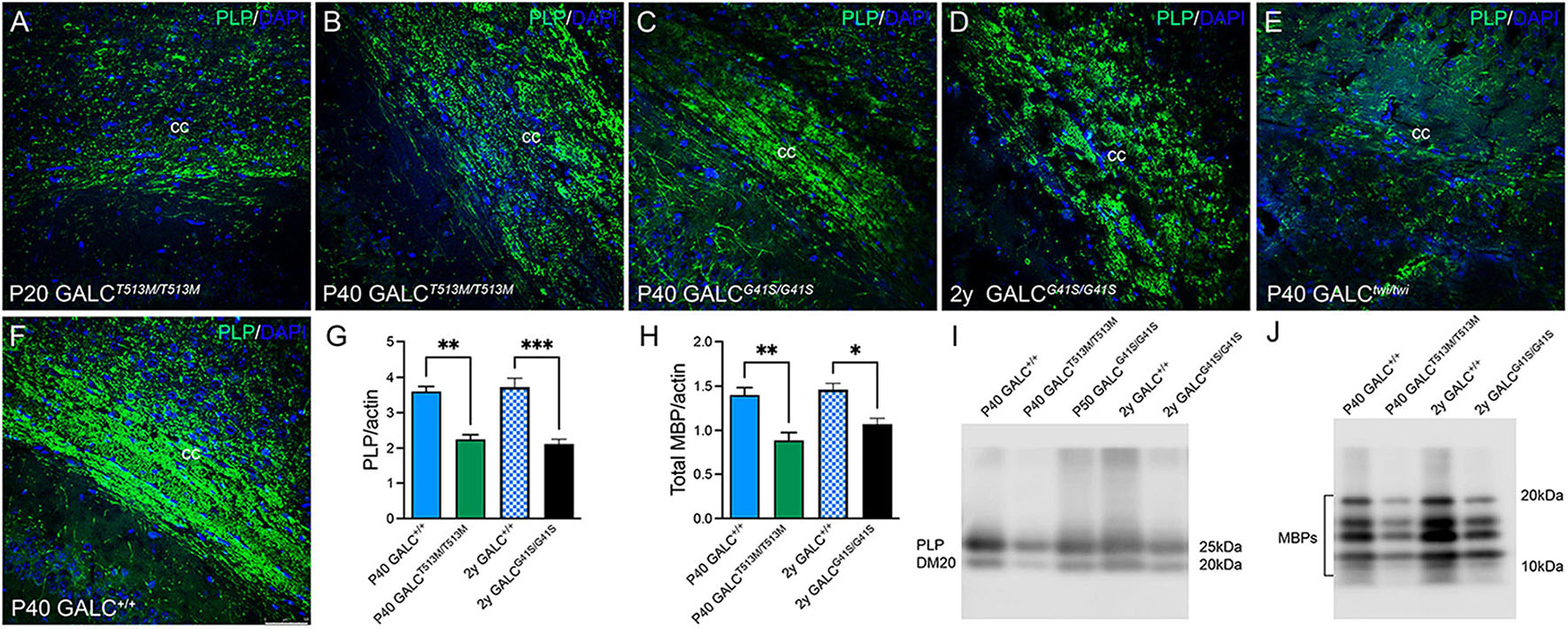

Peripheral myelination also showed contrasting patterns of damage in GALCT513M/T513M and GALCG41S/G41S mice. Toluidine blue staining of sciatic nerve cross sections indicated high levels of peripheral demyelination (i.e., reduced thickness or complete loss of myelin sheaths in axonal profiles), edema (i.e., loss of packed myelinated axons, with swelling of extracellular spaces), and inflammation (i.e., presence of macrophagic profiles within the nerve) in the nerves of P40 GALCT513M/T513M (Figure 8A) comparable to age-matched P40 TWI nerves (Figure 8D). In contrast, early (P40, Figure 8B) or aged (2y, Figure 8C) nerves from GALCG41S/G41S mice did not show significant signs of demyelination or damage. Figures 8E,F show P40 and 2y WT nerves. These results suggest that both new mutants undergo distinct patterns of demyelination: while GALCT513M/T513M mice suffer from rapid central and peripheral demyelination, GALCG41S/G41S mice undergo mostly, if not solely, a late-onset central demyelination, without major impact on peripheral nerves.

Figure 8. GALCT513M/T513M but not GALCG41S/G41S mice exhibit signs of peripheral demyelination. Toluidine blue staining on plastic cross sections of sciatic nerves showed pronounced demyelination and edema in nerves from P40 GALCT513M/T513M mice (A), comparable to damage observed in nerves from age matched TWI mice (D). In contrast, no significant damage to myelin was detected in nerves from either P40 (B) or 2 y-old (C) GALCG41S/G41S mice. (E,F) cross sections of P40 and 2y WT sciatic nerves. Bar = 20 μm.

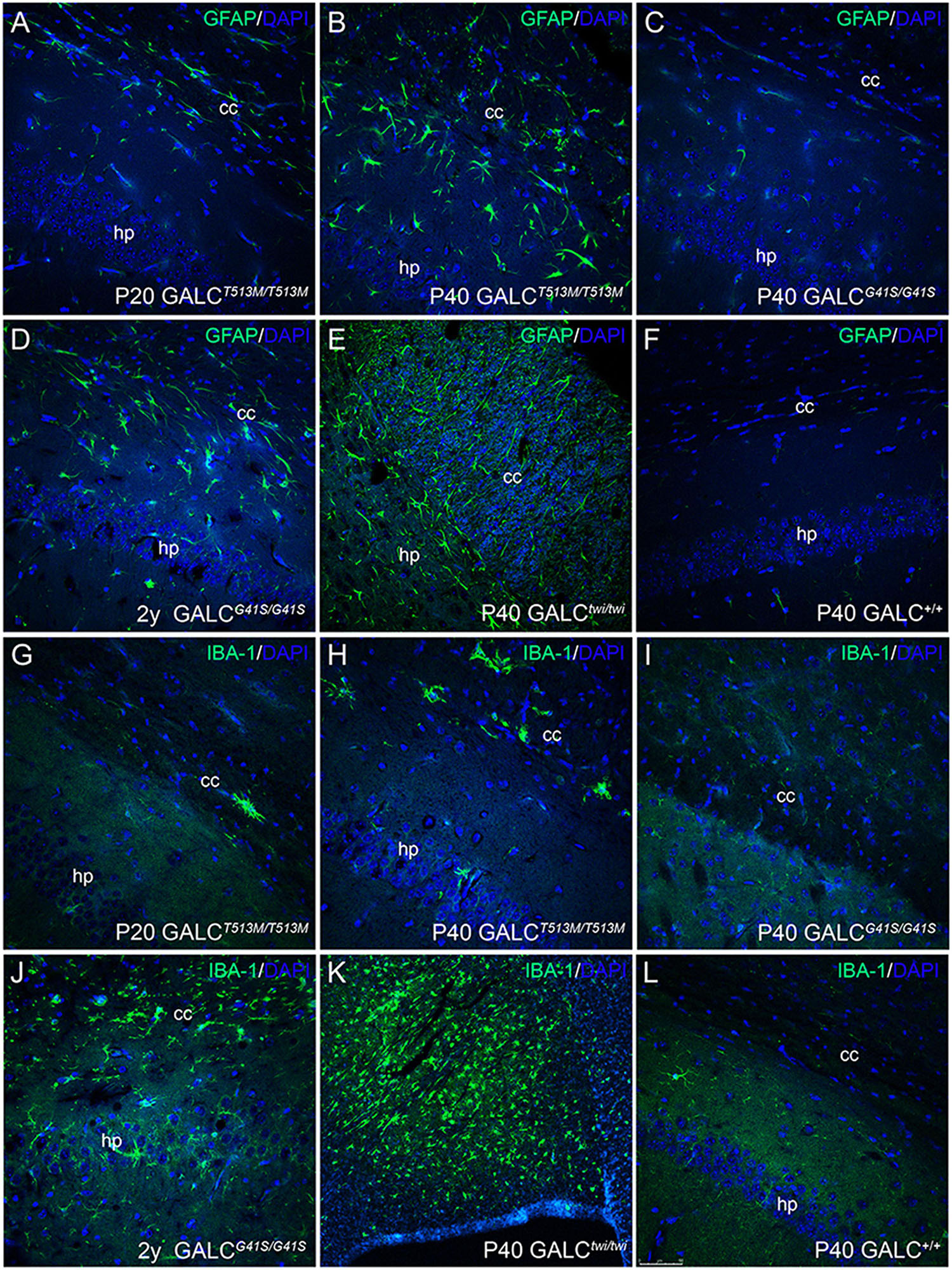

Inflammation was evaluated by immunostaining for GFAP and IBA-1, which identify activated astrocytes (Brenner, 2014) and microglia (Norden et al., 2016). As expected, GFAP+ astrogliosis was markedly increased in the brain of P40 GALCT513M/T513M mice (Figure 9B), to levels comparable to those observed in P40 TWI (Figure 9E). Astrogliosis was also detectable in younger P20 GALCT513M/T513M mice (Figure 9A), suggesting that inflammatory responses start early in the nervous system of GALCT513M/T513M mice. Astrocyte responses in GALCG41S mice were weaker than in GALCT513M/T513M mice, with detectable GFAP+ astroglia in 2y GALCG41S/G41S mice (Figure 9D). At earlier ages (P40), GFAP staining in GALCG41S/G41S and WT brains was indistinguishable (Figures 9C,F). Interestingly, IBA-1 immunostaining was less intense in both mutants (Figures 9G–J) compared with the high levels detected in the P40 TWI brain (Figure 9K). Figure 9L shows IBA-1 in WT.

Figure 9. Inflammatory responses in the brain of GALCT513M/T513M and GALCG41S/G41S mice. Immunohistochemistry using anti-GFAP (A–F) and anti-IBA-1 (G–L) antibodies detected gliotic responses (in green) in the corpus callosum and hippocampus of GALCT513M/T513M and GALCG41S/G41S mice. Confocal microscopy showed that GFAP+ astroglial cells were comparable to those observed in TWI mice (E). In contrast, IBA-1+ cells were less abundant in either mutant than in TWI mice (K). Bar = 50 μm, except in panel (K), where is 100 μm.

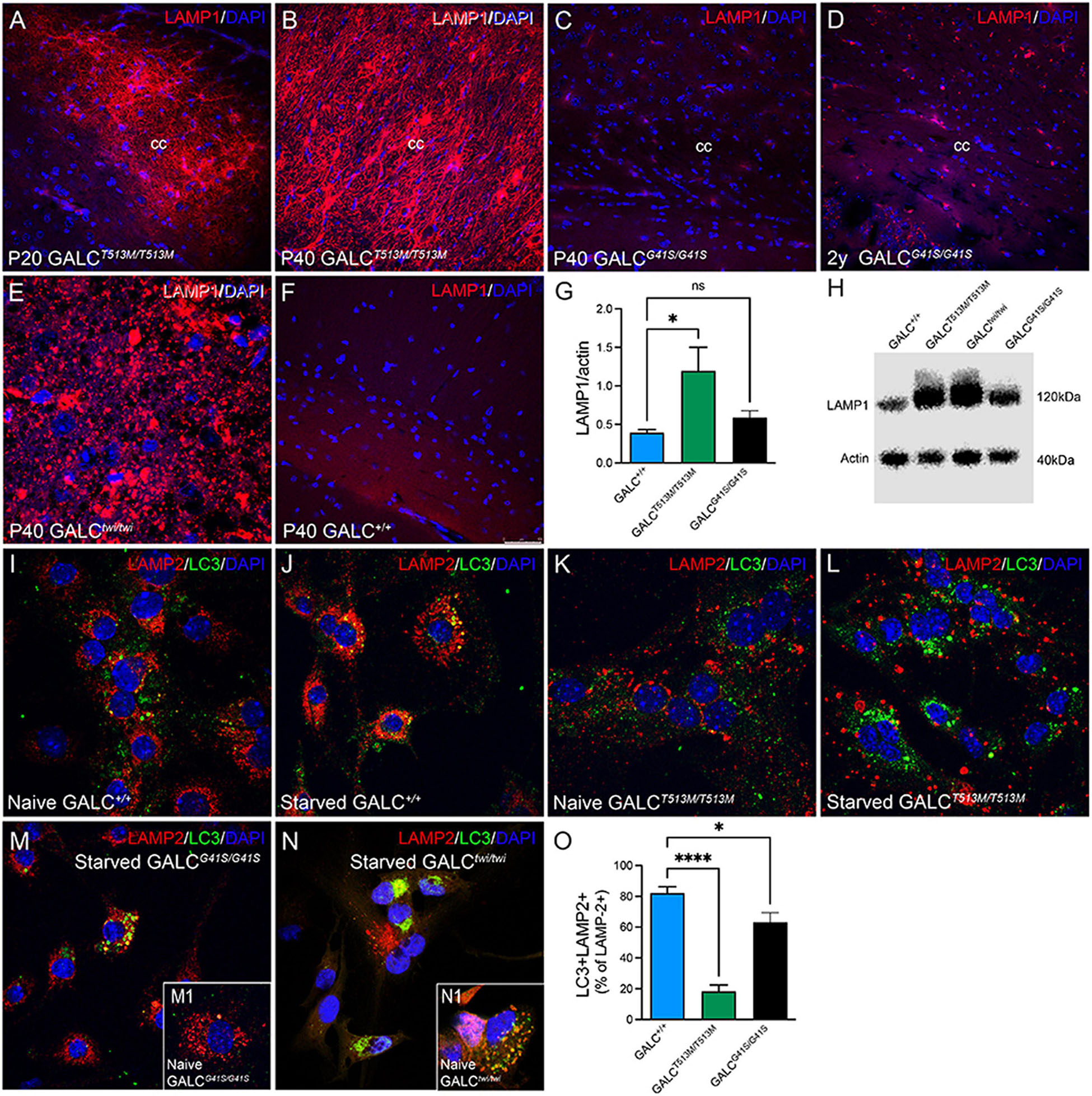

Alterations in lysosomal biogenesis are characteristic findings in KD (Marshall et al., 2018). This can be detected by increased expression of the lysosomal marker LAMP-1, as shown in the P40 TWI brain (Figure 10E). Immunostaining of LAMP-1 showed very intense signals in all white matter areas such as the corpus callosum in both P20 (Figure 10A) and P40 (Figure 10B) GALCT513M/T513M mice. In contrast, white matter areas in the brain of GALCG41S/G41S mice have weaker immunoreactions for LAMP-1, with levels (Figure 10C) comparable with WT (Figure 10F) at P40 and moderately increased in 2y GALCG41S/G41S mice (Figure 10D). Increase of LAMP-1 was confirmed on semiquatitative western blotting from P40 GALCT513M/T513M and 2y GALCG41S/G41S total brain extracts (Figures 10G,H).

Figure 10. Increased Expression of LAMP-1 in White Matter Areas of GALCT513M/T513M and GALCG41S/G41S Mice and Decreased Autophagolysosome Fusion in Cultured Neural Precursors Immunohistochemistry using anti-LAMP-1 antibodies (in red) was used to evaluated lysosomal responses in white matter areas. Confocal microscopy detected very robust increases of LAMP-1 expression in interfascicular oligodendrocytes in white matter areas like the corpus callosum in P20 (A) and P40 (B) GALCT513M/T513M mice, to levels observed in TWI mice (E). In contrast, LAMP-1 expression in GALCG41S/G41S oligodendrocytes was increased in aged mutants (D), but not in younger P40 (C) mice. (F) shows LAMP-1 staining in P40 GALC+/+ corpus callosum. Blue stain: DAPI. Bar = 50 μm. (G,H) Semiquantitation of LAMP-1 levels (by western blotting) in whole brain extracts. Data represent the mean + SEM of n = 4/group, analyzed by ANOVA/Tukey’s post hoc test *p < 0.01; ns, not significant. (I–L) WT (I,J) and GALCT513M/T513M (K,L) cells were fed with our without (starved) 1% FBS for 4 h before double staining for LAMP-2 (red) and LC3 (green). (M,N) GALCG41S/G41S (M) and TWI (N) cells were also starved for 4 h before immunocytochemistry. Insets show naïve cells, respectively. (O) Confocal images were used for counting the total number of LAMP-2+ puncta and the number of double labeled LC3+/LAMP-2+ puncta. Data represent the mean + SEM of 15–20 cells/group, analyzed by ANOVA/Tukey’s post hoc test *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.001.

We and others have indicated deficiencies in the autophagic function in TWI mice (Ribbens et al., 2014; Del Grosso et al., 2019, 2022; Lin et al., 2020). To evaluate whether autophagy is also defective in the new GALCT513M/T513M and GALCG41S/G41S mice, subventricular zone-derived neural progenitor cultures (Felling et al., 2006; Givogri et al., 2008) were starved for 4 h (Mejlvang et al., 2018) before double immunocytochemistry for LC3 and LAMP-2. In normal conditions, starvation promotes autophagy which can be detected by increased fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes as seen with WT cells (Figures 10I,J). As expected, TWI cells have increased production of lysosomes and autophagosomes, which remain largely segregated even when cells underwent starvation (compare Figure 10N with naïve cells in inset N1). Likewise, the basal level of LAMP-2+ lysosomes and LC3+ autophagosomes in naïve (non-starved) GALCT513M/T513M cells is clearly increased (Figure 10K). Starvation only worsens this situation without significant fusion of both organelles (Figure 10L). Instead, formation of autophagolysosomes after starvation seems less compromised in GALCG41S/G41S cells (Figure 10M, compare with naïve GALCG41S/G41S cells, inset M1). Quantification of double labeled LC3+/LAMP-2+ puncta (as a percentage from the total number of LAMP-2+ puncta) confirmed these observations in starved cell cultures (Figure 10O).

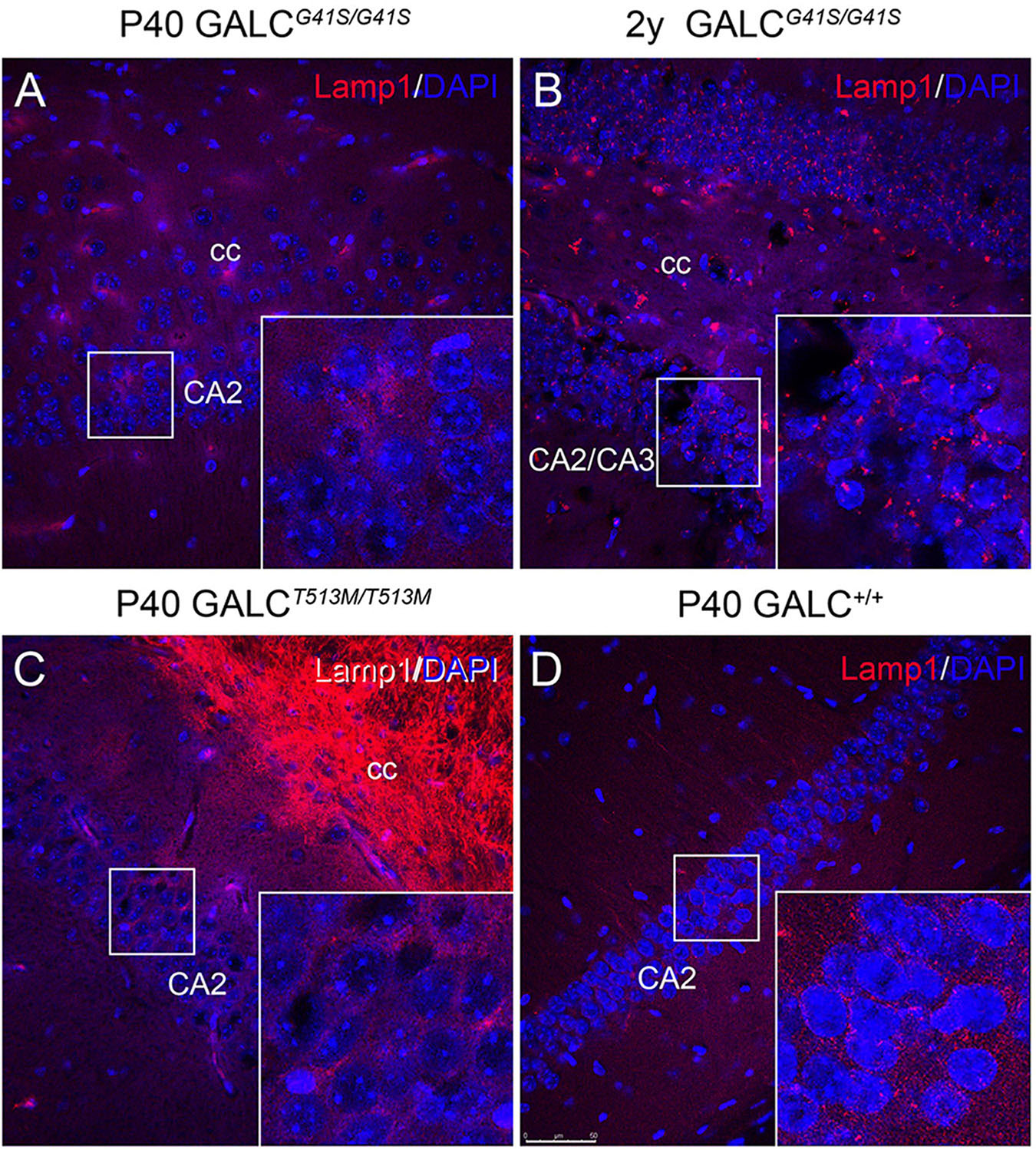

LAMP-1 immunostaining in neuronal rich areas such as the hippocampus was markedly low in the GALCT513M/T513M brain (Figure 11C), with patterns and levels comparable with WT (Figure 11D). In contrast, there was an apparent increase in LAMP-1+ puncta in aged GALCG41S/G41S neurons (Figure 11B box) compared to levels observed at younger ages (Figure 11A box).

Figure 11. Increased expression of LAMP-1 in aged GALCG41S/G41S neurons. Confocal microscopy after immunohistochemistry using anti-LAMP-1 antibodies (in red) was used to evaluated lysosomal responses in hippocampal neurons. Lamp1 expression was not significantly affected in either P40 GALCG41S/G41S (A) or P40 GALCT513M/T513M (C) neurons. However, larger Lamp1+ puncta were detected in 2 year-old GALCG41S/G41S neurons (B), in comparison to control levels (D). Blue: DAPI. Bar = 50 μm.

This study presents two new murine KD models carrying point mutations T513M, frequent in human patients with infantile forms of KD (Wenger et al., 1997), and G41S, found in many adult forms of KD (Lissens et al., 2007). The new mutants were generated using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing and show remarkably reproducible phenotypes, with viable carrier breeders.

GALCT513M/T513M mice show clinical signs of an early neurological condition, with onset of motor and behavioral declines at ∼P24. Mutant mice rapidly progress into stereotypic manifestations of a severe leukodystrophy, with body weight loss, twitching, tremor, and eventually death by the 7th week of life. This mutation is present in many infant patients of European ancestry, contributing to ∼10% of infant forms of KD (Kleijer et al., 1997). These patients show early-onset motor declines and premature death. Homozygous mice for GALCT513M/T513M displayed the expected progression, and thus, constitute a newly engineered but genuine model for infantile KD, matching a severe mutation found in human patients. While the TWI mouse has been historically used as a model for infantile KD, it is more of a surrogate model for the 30 kb deletion found in infantile patients (Kleijer et al., 1997), because the deficiency of GALC activity in TWI mice is due to the absence of detectable GALC protein. In contrast, the new GALCT513M/T513M mouse presents with a clinical disease that recapitulates that of the TWI but with detectable protein both by western blotting and immunohistochemistry.

Mice with the GALCG41S mutation showed normal postnatal development, with no apparent compromise in survival, minimal changes in motor skills, and some alterations in anxiety-type behaviors measurable in aged (>P250) mutants. Patients with this mutation usually present with adult onset manifestations, with less neurological compromise, at least during the first several years of life (Lissens et al., 2007). Thus, the GALCG41S/G41S mutant represents a genuine genetic model recapitulating many aspects of adult-onset KD.

The effects of each mutation on enzymatic activity and lysosomal translocation were remarkably different. In vitro studies have reported how different point mutations in the GALC gene can affect not only the activity, but also its trafficking to the lysosome (Shin et al., 2016; Irahara-Miyana et al., 2018). The GALCT513M mutation changes a polar side chain to a hydrophobic side chain with loss of stabilizing hydrogen bond and steric hindrance (Deane et al., 2011). In vitro studies have shown that this change not only effectively abolishes GALC activity but also largely blocks the mutated protein from reaching the lysosomal compartment (Shin et al., 2016). Aligned with this, enzyme activity and localization analyses in our study show that the GALCT513M/T513M mutated protein lacks detectable enzyme activity, and a large fraction of the protein remains outside of the lysosomal compartment.

The GALCG41S mutation introduces a polar side chain in the TIM barrel domain of the 50 kDa GALC subunit (Lissens et al., 2007; Deane et al., 2011; Spratley et al., 2016; Hill et al., 2018), and thus should have minimal effect on the catalytic site or to induce major protein misfolding impairing transport to lysosomes (Shin et al., 2016). In fact, our in vivo studies show that >80% of GALCG41S immunodetectable protein co-localized with Lamp2+ puncta, retaining significant residual enzyme activity. Likely, the translocation of GALCG41S enzyme residual activity to lysosomes explains the lower accumulation of psychosine in this mutant. In contrast, the GALCT513M/T513M mutants, which have poor lysosomal translocation of a mutated protein without residual enzyme activity, accumulated high levels of psychosine, comparable with levels measured in TWI mice.

The new KD mutants show interesting and chronologically different neuropathological changes. A direct correlation between toxic accumulations of psychosine and levels of demyelination, astrogliosis, and microglial dysfunction in the nervous system of the TWI mouse is well established (Ohno et al., 1993; Taniike and Suzuki, 1994; Giri et al., 2008; Kondo et al., 2011; Claycomb et al., 2014; O’Sullivan and Dev, 2015). As expected, these three neuropathological responses started at onset of clinical signs in GALCT513M/T513M mutants and worsened as disease progressed. Demyelination, while impacting all levels of white matter in the nervous system of GALCT513M/T513M mutants, appeared patchy and less diffuse than that observed in TWI mice, which may indicate undergoing segmental demyelination. Whether there is remyelination ongoing to repair demyelination is currently one area of study in our laboratory. In contrast, central demyelination and gliosis in GALCG41S/G41S mutants were evident only in older mutants, consistent with late-onset neuropathology of adult forms of KD. Peripherally, both mutants also show different patterns of demyelination, which was clearly detected in sciatic nerves from GALCT513M/T513M mutants but absent in GALCG41S/G41S nerves. The different involvement of central and peripheral nerve damage in these mutants clearly and quantifiably place the two models into the early-onset (GALCT513M/T513M) and late-onset (GALCG41S/G41S) categories.

Behavioral examination of both mutants showed clear indications of early (GALCT513M/T513M) vs late (GALCG41S/G41S) motor involvement. GALCT513M/T513M mutants showed stereotypic motor declines comparable to those measured in TWI mice (Olmstead, 1987). All motor readouts, including grip strength, ledge walking, rotarod, and open field tests indicated a progressive neurological involvement of motor pathways, leading to severe and rapid paralysis. On the other hand, GALCG41S/G41S mutants showed mild and late onset deficits in some of the motor tests measured in our study. Interestingly, GALCG41S/G41S mutants showed alterations in behavioral aspects involving exploratory activities and anxiety-related responses. Particularly, GALCG41S/G41S mutants showed increased times involving exploratory activities in the open field, light/dark box, and the Barnes maze tests. This may suggest that GALCG41S/G41S mutants are less anxious, and/or more curious. There are very few studies that have studied cognitive aspects on in KD, with most research focused on infantile cases and fewer on adult-onset cases (Patrick and Wilson, 1972; Crome et al., 1973; Loonen et al., 1985; Olmstead, 1987; Kolodny et al., 1991; Jardim et al., 1999; Debs et al., 2013; Xia et al., 2020; Yoon et al., 2021). In general, most neurodevelopmental deficits in KD have been associated with the loss of myelin and motor skills, which undoubtedly impacts on the capacity of the patient to reach neurodevelopmental milestones. The GALCG41S mutation, which appears to trigger mild and later onset demyelination (Saavedra-Matiz et al., 2016), with minimal involvement of motor and learning skills, shows unexpected anxiolytic effects, at least in some exploratory tasks. Interestingly, changes in social behavior have been described occasionally in KD carriers (Christomanou et al., 1981). Considering that KD is a recessive trait, manifested only in homozygosis, the presence of subtle behavior changes in carriers of the GALCG41S mutation may suggest some level of phenotypic variation in adult-onset KD, at least with some mutations. Defects in remyelination in heterozygous carriers of the twitcher mutation have been described (Scott-Hewitt et al., 2017, 2020), but nothing is known about the effects of GALC haploinsufficiency on cognition. Understanding the cause for these behavioral alterations is an exciting field of study which is under further examination in our laboratory, as it may be relevant to understand phenotypic manifestations reported in carriers for this and other rare conditions (Christomanou et al., 1980, 1981; Cheung and Ewens, 2006).

Impairment in lysosomal activity has been previously reported in several LSDs, with responses involving the proliferation of lysosomes (Napolitano et al., 2015; Sambri et al., 2017). Indeed, the TWI nervous system is characterized by an increased accumulation of lysosomes, detected by their high expression of LAMP-2 (Marshall et al., 2018) and by defective autophagy (Ribbens et al., 2014; Del Grosso et al., 2019, 2022). Both new mutants showed increased expression of lysosomal markers in the brain, although with marked differences. Expression of LAMP-1 is robustly upregulated in white matter in the brain of the GALCT513M/T513M mutant since the onset of disease. In contrast, lysosomal responses in the GALCG41S/G41S mutant in white matter areas are low and only detected in aged mutants. Aligned with results measured in TWI cells (Ribbens et al., 2014; Del Grosso et al., 2019, 2022), GALCT513M/T513M and GALCG41S/G41S cells also showed severe (GALCT513M/T513M) and mild (GALCG41S/G41S) defects in autophagic responses to starvation. Interestingly, aged GALCG41S/G41S mutant neurons showed larger LAMP-1+ puncta, indicative of a late-onset lysosomal dysfunction in this mutant. This late-onset lysosomal response may undermine cellular functions in GALCG41S/G41S mutant neurons and lead to -some- of the observed alterations in exploratory behavior in these mice. Clinical manifestations affecting behavior and cognition have been described in several inborn errors of the metabolism (Gutschalk et al., 2004; Cox, 2020). Whether the GALCG41S mutation, and perhaps others, affecting the GALC gene directly or indirectly impact the structure and/or activity of synapses of neural networks involved in higher cognitive functions remains an open question (Castelvetri et al., 2011; Cantuti Castelvetri et al., 2013; Cantuti-Castelvetri and Bongarzone, 2016; Marshall and Bongarzone, 2016; Gowrishankar et al., 2020; Rebiai et al., 2021) and is the subject of a follow up study in our laboratories. In addition to changes in the metabolism of psychosine, other factors such as accumulation of additional metabolites like lactosylceramide (Papini et al., 2022), alteration of other signaling pathways following lipid raft rearrangements in membranes (White et al., 2009; Sural-Fehr et al., 2019; Belleri and Presta, 2022), abnormal microglia-mediated synaptic pruning (Sellgren et al., 2019), could be also contributors to changes in behavioral responses.

The new GALCT513M/T513M and GALCG41S/G41S murine models described in this study offer contrasting yet unique opportunities to study pathogenic mechanisms affecting synaptic and myelin function and their contribution to the spectrum of phenotypes observed in KD. These new transgenic lines appear as bona fide models of infantile and adult-onset KD, with evident advantages for their use in pre-clinical therapeutic studies. Importantly, this study shows the potential of using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing to introduce and study functional effects of other pathogenic mutations in cis or trans with specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) described in the GALC gene (Saavedra-Matiz et al., 2016). For example some SNPs such as p.I546T, while not pathogenic per se, are known to modify the overall GALC activity when segregated with point mutations such as T513M. This gene editing approach will likely be crucial to help understand genotype-phenotype correlations and mechanisms defining an early vs a late manifestation of Krabbe disease.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

RR performed histology, immunocytochemistry, and wrote manuscript. ER and RB performed quantitative LC-MS-MS of psychosine. SZ and LT performed Morris water maze and wrote dedicated sections. DN established founders. GS and MJ performed cell culture experiments. RF performed motor behaviors. BW and SB performed monoclonal production and wrote dedicated sections. XJ and MS performed isobaric LC-MS-MS and wrote dedicated sections. MG performed histology and wrote dedicated sections. EB designed the study, performed confocal microscopy, and wrote, edited, and proofedited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was funded with a grant from the Legacy of Angels Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS065808) to EB, with additional funding from R01NS082730 to SB.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors thank Martha Santos for technical assistance.

Belleri, M., and Presta, M. (2022). beta-Galactosylceramidase in cancer: more than a psychosine scavenger. Oncoscience 9, 11–12. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.551

Bourin, M., and Hascoet, M. (2003). The mouse light/dark box test. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 463, 55–65. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01274-3

Bradbury, A. M., Bagel, J. H., Nguyen, D., Lykken, E. A., Salvador, J. P., Jiang, X., et al. (2020). Krabbe disease successfully treated via monotherapy of intrathecal gene therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 4906–4920. doi: 10.1172/JCI133953

Brenner, M. (2014). Role of GFAP in CNS injuries. Neurosci. Lett. 565, 7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.01.055

Cantuti Castelvetri, L., Givogri, M. I., Hebert, A., Smith, B., Song, Y., Kaminska, A., et al. (2013). The sphingolipid psychosine inhibits fast axonal transport in Krabbe disease by activation of GSK3β and deregulation of molecular motors. J. Neurosci. 33, 10048–10056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0217-13.2013

Cantuti-Castelvetri, L., and Bongarzone, E. R. (2016). Synaptic failure: the achilles tendon of sphingolipidoses. J. Neurosci. Res. 94, 1031–1036. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23753

Cantuti-Castelvetri, L., Maravilla, E., Marshall, M., Tamayo, T., D’Auria, L., Monge, J., et al. (2015). Mechanism of neuromuscular dysfunction in Krabbe disease. J. Neurosci. 35, 1606–1616. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2431-14.2015

Cantuti-Castelvetri, L., Zhu, H., Givogri, M. I., Chidavaenzi, R. L., Lopez-Rosas, A., and Bongarzone, E. R. (2012). Psychosine induces the dephosphorylation of neurofilaments by deregulation of PP1 and PP2A phosphatases. Neurobiol. Dis. 46, 325–335. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.01.013

Castelvetri, L. C., Givogri, M. I., Hebert, A., Smith, B., Song, Y., Kaminska, A., et al. (2013). The sphingolipid psychosine inhibits fast axonal transport in Krabbe disease by activation of GSK3β and deregulation of molecular motors. J. Neurosci. 33, 10048–10056.

Castelvetri, L. C., Givogri, M. I., Zhu, H., Smith, B., Lopez-Rosas, A., Qiu, X., et al. (2011). Axonopathy is a compounding factor in the pathogenesis of Krabbe disease. Acta Neuropathol. 122, 35–48. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0814-2

Cheung, V. G., and Ewens, W. J. (2006). Heterozygous carriers of Nijmegen breakage syndrome have a distinct gene expression phenotype. Genome Res. 16, 973–979. doi: 10.1101/gr.5320706

Christomanou, H., Jaffe, S., Martinius, J., Cap, C., and Betke, K. (1981). Biochemical, genetic, psychometric, and neuropsychological studies in heterozygotes of a family with globoid cell leucodystrophy (Krabbe’s disease). Hum. Genet. 58, 179–183. doi: 10.1007/BF00278707

Christomanou, H., Martinius, J., Jaffe, S., Betke, K., and Forster, C. (1980). Biochemical, psychometric, and neuropsychological studies in heterozygotes for various lipidoses. Preliminary results. Hum. Genet. 55, 103–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00329134

Claycomb, K. I., Winokur, P. N., Johnson, K. M., Nicaise, A. M., Giampetruzzi, A. W., Sacino, A. V., et al. (2014). Aberrant production of tenascin-C in globoid cell leukodystrophy alters psychosine-induced microglial functions. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 73, 964–974. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000117

Cong, L., Ran, F. A., Cox, D., Lin, S., Barretto, R., Habib, N., et al. (2013). Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas Systems. Science 339, 819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143

Cox, T. M. (2020). Lysosomal diseases and neuropsychiatry: opportunities to rebalance the mind. Front. Mol. Biosci. 7:177. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.00177

Crome, L., Hanefeld, F., Patrick, D., and Wilson, J. (1973). Late onset globoid cell leucodystrophy. Brain 96, 841–848. doi: 10.1093/brain/96.4.841

Deane, J. E., Graham, S. C., Kim, N. N., Stein, P. E., McNair, R., Cachon-Gonzalez, M. B., et al. (2011). Insights into Krabbe disease from structures of galactocerebrosidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 108, 15169–15173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105639108

Debs, R., Froissart, R., Aubourg, P., Papeix, C., Douillard, C., Degos, B., et al. (2013). Krabbe disease in adults: phenotypic and genotypic update from a series of 11 cases and a review. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 36, 859–868. doi: 10.1007/s10545-012-9560-4

Del Grosso, A., Angella, L., Tonazzini, I., Moscardini, A., Giordano, N., Caleo, M., et al. (2019). Dysregulated autophagy as a new aspect of the molecular pathogenesis of Krabbe disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 129, 195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.05.011

Del Grosso, A., Parlanti, G., Angella, L., Giordano, N., Tonazzini, I., Ottalagana, E., et al. (2022). Chronic lithium administration in a mouse model for Krabbe disease. JIMD Rep. 63, 50–65. doi: 10.1002/jmd2.12258

Duchen, L. W., Eicher, E. M., Jacobs, J. M., Scaravilli, F., and Teixeira, F. (1980). Hereditary leucodystrophy in the mouse: the new mutant twitcher. Brain 103, 695–710. doi: 10.1093/brain/103.3.695

Escolar, M. L., West, T., Dallavecchia, A., Poe, M. D., and LaPoint, K. (2016). Clinical management of Krabbe disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 94, 1118–1125. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23891

Felling, R. J., Snyder, M. J., Romanko, M. J., Rothstein, R. P., Ziegler, A. N., Yang, Z., et al. (2006). Neural stem/progenitor cells participate in the regenerative response to perinatal hypoxia/ischemia. J. Neurosci. 26, 4359–4369. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1898-05.2006

Giri, S., Jatana, M., Rattan, R., Won, J. S., Singh, I., and Singh, A. K. (2002). Galactosylsphingosine (psychosine)-induced expression of cytokine-mediated inducible nitric oxide synthases via AP-1 and C/EBP: implications for Krabbe disease. FASEB J. 16, 661–672. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0798com

Giri, S., Khan, M., Nath, N., Singh, I., and Singh, A. K. (2008). The role of AMPK in psychosine mediated effects on oligodendrocytes and astrocytes: implication for Krabbe disease. J. Neurochem. 105, 1820–1833. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05279.x

Givogri, M. I., Bottai, D., Zhu, H. L., Fasano, S., Lamorte, G., Brambilla, R., et al. (2008). Multipotential neural precursors transplanted into the metachromatic leukodystrophy brain fail to generate oligodendrocytes but contribute to limit brain dysfunction. Dev. Neurosci. 30, 340–357. doi: 10.1159/000150127

Gowrishankar, S., Cologna, S. M., Givogri, M. I., and Bongarzone, E. R. (2020). Deregulation of signalling in genetic conditions affecting the lysosomal metabolism of cholesterol and galactosyl-sphingolipids. Neurobiol. Dis. 146:105142. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.105142

Graziano, A. C. E., and Cardile, V. (2015). History, genetic, and recent advances on Krabbe disease. Gene 555, 2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.09.046

Greiner-Tollersrud, O., and Berg, T. (2000/2013). Lysosomal Storage Disorders. Madame Curie Bioscience Database [Internet]. Austin, TX: Landes Bioscience.

Gutschalk, A., Harting, I., Cantz, M., Springer, C., Rohrschneider, K., and Meinck, H. M. (2004). Adult alpha-mannosidosis: clinical progression in the absence of demyelination. Neurology 63, 1744–1746. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000143057.25471.4f

Hawkins-Salsbury, J. A., Parameswar, A. R., Jiang, X., Schlesinger, P. H., Bongarzone, E., Ory, D. S., et al. (2013). Psychosine, the cytotoxic sphingolipid that accumulates in globoid cell leukodystrophy, alters membrane architecture. J. Lipid Res. 54, 3303–3311. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M039610

Hill, C. H., Cook, G. M., Spratley, S. J., Fawke, S., Graham, S. C., and Deane, J. E. (2018). The mechanism of glycosphingolipid degradation revealed by a GALC-SapA complex structure. Nat. Commun. 9:151. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02361-y

Hsu, P. D., Scott, D. A., Weinstein, J. A., Ran, F. A., Konermann, S., Agarwala, V., et al. (2013). DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 827–832. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2647

Igisu, H., and Suzuki, K. (1984). Progressive accumulation of toxic metabolite in a genetic leukodystrophy. Science 224, 753–755. doi: 10.1126/science.6719111

Irahara-Miyana, K., Otomo, T., Kondo, H., Hossain, M. A., Ozono, K., and Sakai, N. (2018). Unfolded protein response is activated in Krabbe disease in a manner dependent on the mutation type. J. Hum. Genet. 63, 699–706. doi: 10.1038/s10038-018-0445-8

Jardim, L. B., Giugliani, R., Pires, R. F., Haussen, S., Burin, M. G., Rafi, M. A., et al. (1999). Protracted course of Krabbe disease in an adult patient bearing a novel mutation. Arch. Neurol. 56, 1014–1017. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.8.1014

Kan, S. H., Le, S. Q., Bui, Q. D., Benedict, B., Cushman, J., Sands, M. S., et al. (2016). Behavioral deficits and cholinergic pathway abnormalities in male Sanfilippo B mice. Behav. Brain Res. 312, 265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.06.023

Kleijer, W. J., Keulemans, J. L., van der Kraan, M., Geilen, G. G., van der Helm, R. M., Rafi, M. A., et al. (1997). Prevalent mutations in the GALC gene of patients with Krabbe disease of Dutch and other European origin. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 20, 587–594. doi: 10.1023/a:1005315311165

Kobayashi, T., Shinoda, H., Goto, I., Yamanaka, T., and Suzuki, Y. (1987). Globoid cell leukodystrophy is a generalized galactosylsphingosine (psychosine) storage disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 144, 41–46. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(87)80472-2

Kolodny, E. H., Raghavan, S., and Krivit, W. (1991). Late-onset Krabbe disease (globoid cell leukodystrophy): clinical and biochemical features of 15 cases. Dev. Neurosci. 13, 232–239. doi: 10.1159/000112166

Kondo, Y., Adams, J. M., Vanier, M. T., and Duncan, I. D. (2011). Macrophages counteract demyelination in a mouse model of globoid cell leukodystrophy. J. Neurosci. 31, 3610–3624. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6344-10.2011

Lee, W. C., Kang, D., Causevic, E., Herdt, A. R., Eckman, E. A., and Eckman, C. B. (2010). Molecular characterization of mutations that cause globoid cell leukodystrophy and pharmacological rescue using small molecule chemical chaperones. J. Neurosci. 30, 5489–5497. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6383-09.2010

Lee, W. C., Tsoi, Y. K., Dickey, C. A., Delucia, M. W., Dickson, D. W., and Eckman, C. B. (2006). Suppression of galactosylceramidase (GALC) expression in the twitcher mouse model of globoid cell leukodystrophy (GLD) is caused by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (n.d.). Neurobiol. Dis. 23, 273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.03.005

Lin, D. S., Ho, C. S., Huang, Y. W., Wu, T. Y., Lee, T. H., Huang, Z. D., et al. (2020). Impairment of Proteasome and Autophagy underlying the pathogenesis of Leukodystrophy. Cells 9:1124. doi: 10.3390/cells9051124

Lissens, W., Arena, A., Seneca, S., Rafi, M., Sorge, G., Liebaers, I., et al. (2007). A single mutation in the GALC gene is responsible for the majority of late onset Krabbe disease patients in the Catania (Sicily, Italy) region. Hum. Mutat. 28:742. doi: 10.1002/humu.9500

Loonen, M. C., Van Diggelen, O. P., Janse, H. C., Kleijer, W. J., and Arts, W. F. (1985). Late-onset globoid cell leucodystrophy (Krabbe’s disease). Clinical and genetic delineation of two forms and their relation to the early-infantile form. Neuropediatrics 16, 137–142. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1052558

Malmberg-Aiello, P., Ipponi, A., Bartolini, A., and Schunack, W. (2002). Mouse light/dark box test reveals anxiogenic-like effects by activation of histamine H1 receptors. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 71, 313–318. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00691-8

Marshall, M. S., and Bongarzone, E. R. (2016). Beyond Krabbe’s disease: The potential contribution of galactosylceramidase deficiency to neuronal vulnerability in late-onset synucleinopathies. J. Neurosci. Res. 94, 1328–1332. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23751

Marshall, M. S., Issa, Y., Jakubauskas, B., Stoskute, M., Elackattu, V., Marshall, J. N., et al. (2018). Long-Term improvement of neurological signs and metabolic dysfunction in a mouse model of Krabbe’s disease after global gene therapy. Mol. Ther. 26, 874–889. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.01.009

Mejlvang, J., Olsvik, H., Svenning, S., Bruun, J. A., Abudu, Y. P., Larsen, K. B., et al. (2018). Starvation induces rapid degradation of selective autophagy receptors by endosomal microautophagy. J. Cell Biol. 217, 3640–3655. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201711002

Napolitano, G., Johnson, J. L., He, J., Rocca, C. J., Monfregola, J., Pestonjamasp, K., et al. (2015). Impairment of chaperone-mediated autophagy leads to selective lysosomal degradation defects in the lysosomal storage disease cystinosis. EMBO Mol. Med. 7, 158–174. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404223

Nelvagal, H. R., Dearborn, J. T., Ostergaard, J. R., Sands, M. S., and Cooper, J. D. (2021). Spinal manifestations of CLN1 disease start during the early postnatal period. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 47, 251–267. doi: 10.1111/nan.12658

Norden, D. M., Trojanowski, P. J., Villanueva, E., Navarro, E., and Godbout, J. P. (2016). Sequential activation of microglia and astrocyte cytokine expression precedes increased Iba-1 or GFAP immunoreactivity following systemic immune challenge. Glia 64, 300–316. doi: 10.1002/glia.22930

Ohno, M., Komiyama, A., Martin, P. M., and Suzuki, K. (1993). Proliferation of microglia/macrophages in the demyelinating CNS and PNS of twitcher mouse. Brain Res. 602, 268–274. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90692-g

Olmstead, C. E. (1987). Neurological and neurobehavioral development of the mutant ‘twitcher’ mouse. Behav. Brain Res. 25, 143–153. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(87)90007-6

O’Sullivan, C., and Dev, K. K. (2015). Galactosylsphingosine (psychosine)-induced demyelination is attenuated by sphingosine 1-phosphate signalling. J. Cell Sci. 128, 3878–3887. doi: 10.1242/jcs.169342

Papini, N., Giallanza, C., Brioschi, L., Ranieri, F. R., Giussani, P., Mauri, L., et al. (2022). Galactocerebrosidase deficiency induces an increase in lactosylceramide content: a new hallmark of Krabbe disease? Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 145:106184. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2022.106184

Patil, S. S., Sunyer, B., Hoger, H., and Lubec, G. (2009). Evaluation of spatial memory of C57BL/6J and CD1 mice in the Barnes maze, the multiple T-maze and in the morris water maze. Behav. Brain Res. 198, 58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.10.029

Patrick, D., and Wilson, J. (1972). Late onset form of globoid cell leucodystrophy. Arch. Dis. Child 47:672. doi: 10.1136/adc.47.254.672

Pfister, K. K., Wagner, M. C., Stenoien, D. L., Brady, S. T., and Bloom, G. S. (1989). Monoclonal antibodies to kinesin heavy and light chains stain vesicle-like structures, but not microtubules, in cultured cells. J. Cell Biol. 108, 1453–1463. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.4.1453

Rebiai, R., Givogri, M. I., Gowrishankar, S., Cologna, S. M., Alford, S. T., and Bongarzone, E. R. (2021). Synaptic Function and Dysfunction in Lysosomal storage diseases. Front. Cell Neurosci. 15:619777. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2021.619777

Ribbens, J. J., Moser, A. B., Hubbard, W. C., Bongarzone, E. R., and Maegawa, G. H. (2014). Characterization and application of a disease-cell model for a neurodegenerative lysosomal disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 111, 172–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.09.011

Saavedra-Matiz, C. A., Luzi, P., Nichols, M., Orsini, J. J., Caggana, M., and Wenger, D. A. (2016). Expression of individual mutations and haplotypes in the galactocerebrosidase gene identified by the newborn screening program in New York State and in confirmed cases of Krabbe’s disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 94, 1076–1083. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23905

Sambri, I., D’Alessio, R., Ezhova, Y., Giuliano, T., Sorrentino, N. C., Cacace, V., et al. (2017). Lysosomal dysfunction disrupts presynaptic maintenance and restoration of presynaptic function prevents neurodegeneration in lysosomal storage diseases. EMBO Mol. Med. 9, 112–132. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606965

Scott-Hewitt, N., Perrucci, F., Morini, R., Erreni, M., Mahoney, M., Witkowska, A., et al. (2020). Local externalization of phosphatidylserine mediates developmental synaptic pruning by microglia. EMBO J. 39:e105380. doi: 10.15252/embj.2020105380

Scott-Hewitt, N. J., Folts, C. J., Hogestyn, J. M., Piester, G., Mayer-Proschel, M., and Noble, M. D. (2017). Heterozygote galactocerebrosidase (GALC) mutants have reduced remyelination and impaired myelin debris clearance following demyelinating injury. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26, 2825–2837. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx153

Sellgren, C. M., Gracias, J., Watmuff, B., Biag, J. D., Thanos, J. M., Whittredge, P. B., et al. (2019). Increased synapse elimination by microglia in schizophrenia patient-derived models of synaptic pruning. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 374–385. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0334-7

Shin, D., Feltri, M. L., and Wrabetz, L. (2016). Altered trafficking and processing of GALC mutants correlates with Globoid Cell Leukodystrophy Severity. J. Neurosci. 36, 1858–1870. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3095-15.2016

Sidhu, R., Mikulka, C. R., Fujiwara, H., Sands, M. S., Schaffer, J. E., Ory, D. S., et al. (2018). A HILIC-MS/MS method for simultaneous quantification of the lysosomal disease markers galactosylsphingosine and glucosylsphingosine in mouse serum. Biomed. Chromatogr. 32:e4235. doi: 10.1002/bmc.4235

Smith, B., Galbiati, F., Castelvetri, L. C., Givogri, M. I., Lopez-Rosas, A., and Bongarzone, E. R. (2011). Peripheral neuropathy in the Twitcher mouse involves the activation of axonal caspase 3. ASN Neuro 3:e00066. doi: 10.1042/AN20110019

Spassieva, S., and Bieberich, E. (2016). Lysosphingolipids and sphingolipidoses: psychosine in Krabbe’s disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 94, 974–981. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23888

Spratley, S. J., Hill, C. H., Viuff, A. H., Edgar, J. R., Skjodt, K., and Deane, J. E. (2016). Molecular mechanisms of disease pathogenesis differ in Krabbe disease variants. Traffic 17, 908–922. doi: 10.1111/tra.12404

Sural-Fehr, T., Singh, H., Cantuti-Catelvetri, L., Zhu, H., Marshall, M. S., Rebiai, R., et al. (2019). Inhibition of the IGF-1–PI3K–Akt–mTORC2 pathway in lipid rafts increases neuronal vulnerability in a genetic lysosomal glycosphingolipidosis. Dis. Models Mech. 12:dmm036590. doi: 10.1242/dmm.036590

Suzuki, K., and Suzuki, Y. (1970). Globoid cell leucodystrophy (Krabbe’s disease): deficiency of galactocerebroside beta-galactosidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 66, 302–309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.66.2.302

Suzuki, K., and Taniike, M. (1995). Murine model of genetic demyelinating disease: the twitcher mouse. Microsc. Res. Tech. 32, 204–214. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070320304

Taniike, M., and Suzuki, K. (1994). Spacio-temporal progression of demyelination in twitcher mouse: with clinico-pathological correlation. Acta Neuropathol. 88, 228–236. doi: 10.1007/BF00293398

Tappino, B., Biancheri, R., Mort, M., Regis, S., Corsolini, F., Rossi, A., et al. (2010). Identification and characterization of 15 novel GALC gene mutations causing Krabbe disease. Hum. Mutat. 31, E1894–E1914. doi: 10.1002/humu.21367

Wang, H., Yang, H., Shivalila, C. S., Dawlaty, M. M., Cheng, A. W., Zhang, F., et al. (2013). One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. cell 153, 910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.025

Wenger, D. (2001). Galactosyl-ceramide Lipidosis: Globoid Cell Leukodystrophy (Krabbe disease). The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease (New York: McGraw-Hill). *c/p.

Wenger, D. A., Rafi, M. A., and Luzi, P. (1997). Molecular genetics of Krabbe disease (globoid cell leukodystrophy): diagnostic and clinical implications. Hum. Mutat. 10, 268–279. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)10:4<268::AID-HUMU2>3.0.CO;2-D

White, A. B., Givogri, M. I., Lopez-Rosas, A., Cao, H., van Breemen, R., Thinakaran, G., et al. (2009). Psychosine accumulates in membrane microdomains in the brain of krabbe patients, disrupting the raft architecture. J. Neurosci. 29, 6068–6077. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5597-08.2009

Xia, Z., Wenwen, Y., Xianfeng, Y., Panpan, H., Xiaoqun, Z., and Zhongwu, S. (2020). Adult-onset Krabbe disease due to a homozygous GALC mutation without abnormal signals on an MRI in a consanguineous family: a case report. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 8:e1407. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1407

Keywords: galactosylceramidase, demyelination, synapses, lysosome, autophagy

Citation: Rebiai R, Rue E, Zaldua S, Nguyen D, Scesa G, Jastrzebski M, Foster R, Wang B, Jiang X, Tai L, Brady ST, van Breemen R, Givogri MI, Sands MS and Bongarzone ER (2022) CRISPR-Cas9 Knock-In of T513M and G41S Mutations in the Murine β–Galactosyl-Ceramidase Gene Re-capitulates Early-Onset and Adult-Onset Forms of Krabbe Disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 15:896314. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.896314

Received: 14 March 2022; Accepted: 19 April 2022;

Published: 10 May 2022.

Edited by:

Stefanie Flunkert, QPS Austria, AustriaReviewed by:

Ambra Del Grosso, Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, ItalyCopyright © 2022 Rebiai, Rue, Zaldua, Nguyen, Scesa, Jastrzebski, Foster, Wang, Jiang, Tai, Brady, van Breemen, Givogri, Sands and Bongarzone. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ernesto R. Bongarzone, ZWJvbmdhcnpAdWljLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.