- 1Graduate Institute of Integrated Medicine, College of Chinese Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

- 2Department of Medical Research, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

- 3School of Chinese Medicine, College of Chinese Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

- 4Graduate Institute of Acupuncture Science, College of Chinese Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

The found in neurons (fne), a paralog of the RNA-binding protein ELAV gene family in Drosophila, is required for post-transcriptional regulation of neuronal development and differentiation. Previous explorations into the functions of the FNE protein have been limited to neurons. The function of fne in Drosophila glia remains unclear. We induced the knockdown or overexpression of fne in Drosophila neurons and glia to determine how fne affects different types of behaviors, neuronal transmission and the lifespan. Our data indicate that changes in fne expression impair associative learning, thermal nociception, and phototransduction. Examination of synaptic transmission at presynaptic and postsynaptic terminals of the larval neuromuscular junction (NMJ) revealed that loss of fne in motor neurons and glia significantly decreased excitatory junction currents (EJCs) and quantal content, while flies with glial fne knockdown facilitated short-term synaptic plasticity. In muscle cells, overexpression of fne reduced both EJC and quantal content and increased short-term synaptic facilitation. In both genders, the lifespan could be extended by the knockdown of fne in neurons and glia; the overexpression of fne shortened the lifespan. Our results demonstrate that disturbances of fne in neurons and glia influence the function of the Drosophila nervous system. Further explorations into the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying neuronal and glial fne and elucidation of how fne affects neuronal activity may clarify certain brain functions.

Introduction

The embryonic lethal abnormal visual system-like (ELAVL/Hu) proteins are a family of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) with three highly conserved RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) that mediate the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression through alternative RNA splicing, localization, stability, translation, and metabolism (Colombrita et al., 2013). Humans possess four ELAVL/Hu protein-encoding genes; specifically, a ubiquitous member (ELAVL1/HuR) and three predominantly neuronal members (ELAVL2/HuB, ELAVL3/HuC, and ELAVL4/HuD), which are often used as reliable biomarkers for neurons. The Drosophila ELAV family comprises three members: elav, RNA-binding protein 9 (Rbp9), and found in neurons (fne). These proteins are highly enriched in neurons, and RBP9 is also found in gonads (Colombrita et al., 2013). The ELAV protein is encoded by elav, and deletion of elav leads to defects in the visual system and to embryonic lethality (Jimenez and Campos-Ortega, 1987). ELAV is mostly found in the neuronal nucleus and is involved in the stability of mRNA, alternative splicing, and in the cleavage of the polyadenylation site of the 3’ untranslated region (3’-UTR) (Koushika et al., 1996; Carrasco et al., 2020). The RBP9 protein encoded by Rbp9 is present not only in neuronal nuclei but also in the cytoplasm of cystocytes during oogenesis for the necessity of germ cell differentiation (Kim-Ha et al., 1999). No gross neural developmental defects have been observed in Rbp9 null mutation, but reduced locomotor activity, shorter lifespan, and defects in the blood-brain barrier and female sterility have been observed (Kim-Ha et al., 1999; Kim et al., 2010).

The third elav-related gene in Drosophila, fne, is present throughout development but after elav expression. The FNE protein is cytoplasmic and is restricted to neurons of the central and peripheral nervous systems (PNS) (Samson and Chalvet, 2003). The functional necessity of ELAV and FNE proteins to performing neural 3’-UTR alternative polyadenylation (APA) has been demonstrated, and in the absence of elav, FNE can rescue ELAV-mediated APA (Carrasco et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2020). Null mutants of fne were viable in adults: morphological defects were not apparent, but overexpression of fne in neurons resulted in an extreme decrease in the viability and phenotypic defects in the wings and legs (Samson, 2008). fne is also involved in the male courtship performance and the development of sex-specific nervous systems, and is required to restrict axonal extension of the beta lobes in adult mushroom body, a brain structure essential for the learning and memory (Zanini et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2015).

The physiological function of glia in Drosophila has been documented (Yildirim et al., 2019). In the central nervous system (CNS), similar with mammalian glia interacting with neurons, Drosophila glia are required for the regulation of neuronal development and differentiation in the brain and in the visual system (Edwards and Meinertzhagen, 2010). Glial cells also provide various supportive functions to neurons, including the modulation of electrical transmission or ion homeostasis, metabolic support of neurons, BBB formation, and responses to neuronal injury or infection (Logan, 2017; Nagai et al., 2021). In the PNS, the peripheral glia play an important role in coordinating synaptogenesis and shaping the synaptic connection in the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) by releasing glia-derived factors (Ou et al., 2014).

Studies on fne have mainly focused on neurons. However, the function of fne in glia has not yet been identified. In the present study, we investigated the physiological and molecular effects of fne in both neurons and glia, and our results revealed that changes in fne expression impaired phototransduction, learning performance, and thermal nociception. Changes in fne expression also affected the synaptic transmission and plasticity of the larval NMJ and preferentially acted at the presynaptic terminal, while knockdown of fne in the glia was highly influential. Our results suggest that expression of fne in the glia is essential for neurotransmission and elucidate the mechanism of fne in flies, possibly by extension, in mammals.

Materials and methods

Fly culture and strains

Drosophila strains were raised on regular cornmeal food under a 12-hr light/dark cycle with consistent 50–60% humidity at 25°C unless otherwise noted. The wild-type strain was w1118. The fly strains used in this study, including GMR-GAL4 (photoreceptor-specific, stock #1104), tub-Gal80ts (stock #7018 and 7019), TrpA11 (stock #26504), and UAS-fne (stock #6897) (Chalvet and Samson, 2002) were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC), and fne-knockdown strain (UAS-fne-IR, stock #101508) (Alizzi et al., 2020) was obtained from the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center (VDRC). The strains, elavC155-GAL4 (neuron-specific), C57-GAL4 (muscle cell-specific), and repo7415-GAL4 (glia-specific), which were outcrossed with w1118 (isoCJ1) for at least five generations, were provided by Dr. Hui-Fu Guo. Functioning of UAS-fne and UAS-fne-IR lines was verified in Supplementary Figure 1.

Because overexpressing fne under repo-GAL4 and C57-GAL4 drivers results in larval/pupal lethality, we used the TARGET expression system to temporally control fne expression under the specific GAL4 drivers combined with temperature-sensitive GAL80ts (tub-GAL80ts) (McGuire et al., 2004). The flies were reared at the permissive temperature (18°C) during the developmental stages and shifted to the non-permissive temperature (25 or 29°C) after eclosion to initiate GAL4 transcription of UAS transgenes.

Electroretinogram analysis

The Electroretinogram (ERG) test was performed as previously described (Cosens and Manning, 1969). Briefly, each fly was captured in a pipette tip. A reference electrode was contacted with the head and a recording electrode was attached to the fly’s compound eye. The fly eye was exposed to a 1.5 W white-light LED which is programmed to a repetitive on-off cycle of 2–6 s. Signals were recorded by Axon Instruments GeneClamp 500 Voltage Patch Clamp Amplifier (Molecular Devices, USA) and analyzed by Axon Instruments pCLAMP software (Molecular Devices, USA). The ERG was recorded from males which were reared at 18°C and shifted to 29°C after eclosion for 5 days to induce fne and fne-IR expression in photoreceptors and glia under GMR-GAL4 and repo-GAL4 combined with tub-GAL80ts (referred as GMRts and repots), respectively. Data were collected and analyzed at least 6 on-off cycles per fly.

Olfactory associative learning assay

The flies with fne and fne-IR were reared at 18°C and after eclosion, shifted to 25 or 29°C to induce transgenes expression in neurons and glia under elavts and repots, respectively. A single training trial was performed according to previous studies (Dubnau et al., 2001). Briefly, approximately 100 flies were exposed sequentially to two odors, either 3-octanol (OCT, Sigma-Aldrich) or 4-methylcyclohexanol (MCH, Sigma-Aldrich). Flies exposed to the first odor (conditioned stimulus, CS +) were paired with 80 V electric shocks and then received a second odor (CS-) without shocks. Learning ability was determined immediately after training. To perform the test, the trained flies were trapped into the choice point of a T-maze in which they were exposed simultaneously to OCT and MCH. A performance index (PI) was calculated to represent the conditioned odor avoidance. The PI = (# of CS- – # of CS +)/(# of total flies), and the final PI was calculated by averaging the PI in which OCT was the shock-paired odor and one in which MCH was the shock-paired odor. A PI of zero (no learning) indicated a 50:50 distribution, and a PI of 100 showed a 0:100 distribution away from the CS + odor.

Nociceptive test

For the avoidance of noxious heat, we used the behavior paradigm as previously described (Neely et al., 2011). Briefly, approximately 20 male flies were placed in a sealed peri dish chamber. The chamber was then floated on a 46°C water bath for 1 min 30 s. The bottom of the chamber was heated to 46°C, whereas the top of chamber was measured to be 31°C. All tests were performed under red light. Flies that move away from the 46°C bottom surface were considered to be capable of avoidance of heat challenge. The percentage of avoidance in response to noxious temperature was calculated by counting the number of flies that avoid the noxious temperature compared to the total number of flies in the chamber. The flies with fne and fne-IR were maintained at 18°C and the newly eclosed adult males were shifted to 29°C for 5 days and 25°C for 10 days to induce transgene expression in neurons and glia under elavts and repots control, respectively.

Electrophysiology of the larval neuromuscular junction

Electrophysiological recordings of two-electrode voltage clamp were performed as previously described (Guo and Zhong, 2006). Wall climbing third-instar larvae were chosen for dissection at 25°C in Ca2+-free hemolymph-like (HL-3) solution containing the following (in mM): 70 NaCl, 5 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 10 NaHCO3, 5 trehalose, 5 HEPES, and 115 sucrose. For recordings, HL-3 solution was supplemented with 0.2 mM CaCl2. All recordings were made at the longitudinal muscle fiber 12 (M12) of segments A3-A5. To elicit evoked excitatory junction currents (EJCs), the segmental nerve was stimulated with a suction electrode at 1.5 times of the stimulus voltage required for a threshold response. Continuous recordings were made to measure the EJCs and miniature EJCs (mEJCs) while the nerve was stimulated at the baseline frequency of 0.05 Hz. For induction of short-term facilitation (STF), short trains of 20 repetitive stimulation were delivered at the frequency of 0.5–25 Hz. Current signals were amplified with an Axoclamp 2A amplifier (Molecular Devices, USA), filtered at 0.1 kHz on-line, and converted to a digital signal using a Digidata 1320A interface (Molecular Devices, USA) and pCLAMP software (Molecular Devices, USA). Stimulation of nerves was achieved by a Grass Instruments S88 Stimulator (Grass Instruments, USA). EJCs were determined by averaging consecutive EJCs in 0.05 Hz during the 5 min recording period, while mEJCs were analyzed from continuous recordings of 1 min. Values of average mEJC amplitudes were determined and quantal content is calculated as dividing average EJC amplitude by average mEJC amplitude. For STF, the EJC amplitudes of the last 10 responses in each train were averaged and normalized to the average EJC amplitudes at 0.5 Hz. The experiments were performed at 25°C. For overexpressing fne under C57ts and repots, the flies were reared at 18°C started from embryonic stages, shifted to 29°C for 1 day, and performed electrophysiology.

Longevity assay

The flies were expressed fne and fne-IR under elavts and repots drivers. All flies were maintained at 18°C and shifted to 25°C after eclosion. Emerging adult flies were collected and separated by sex. Around thirty to thirty-five flies were kept in a vial. Four repeat vials, comprising at least 120 flies in total were conducted for each genotype. Food vials were replaced every 3–4 days, and dead flies were counted at that time.

Data analyses and statistics

Statistical analysis of associate learning and longevity assay were performed by a Student’s t-test and Log-rank test, respectively. For multiple comparisons of ERG, nociceptive test, and electrophysiology, data were performed using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Turkey post-hoc test. The results represent as mean ± standard error mean (SEM) from at least three biological replicates. p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistical significance.

Results

Electroretinogram amplitudes are influenced by fne

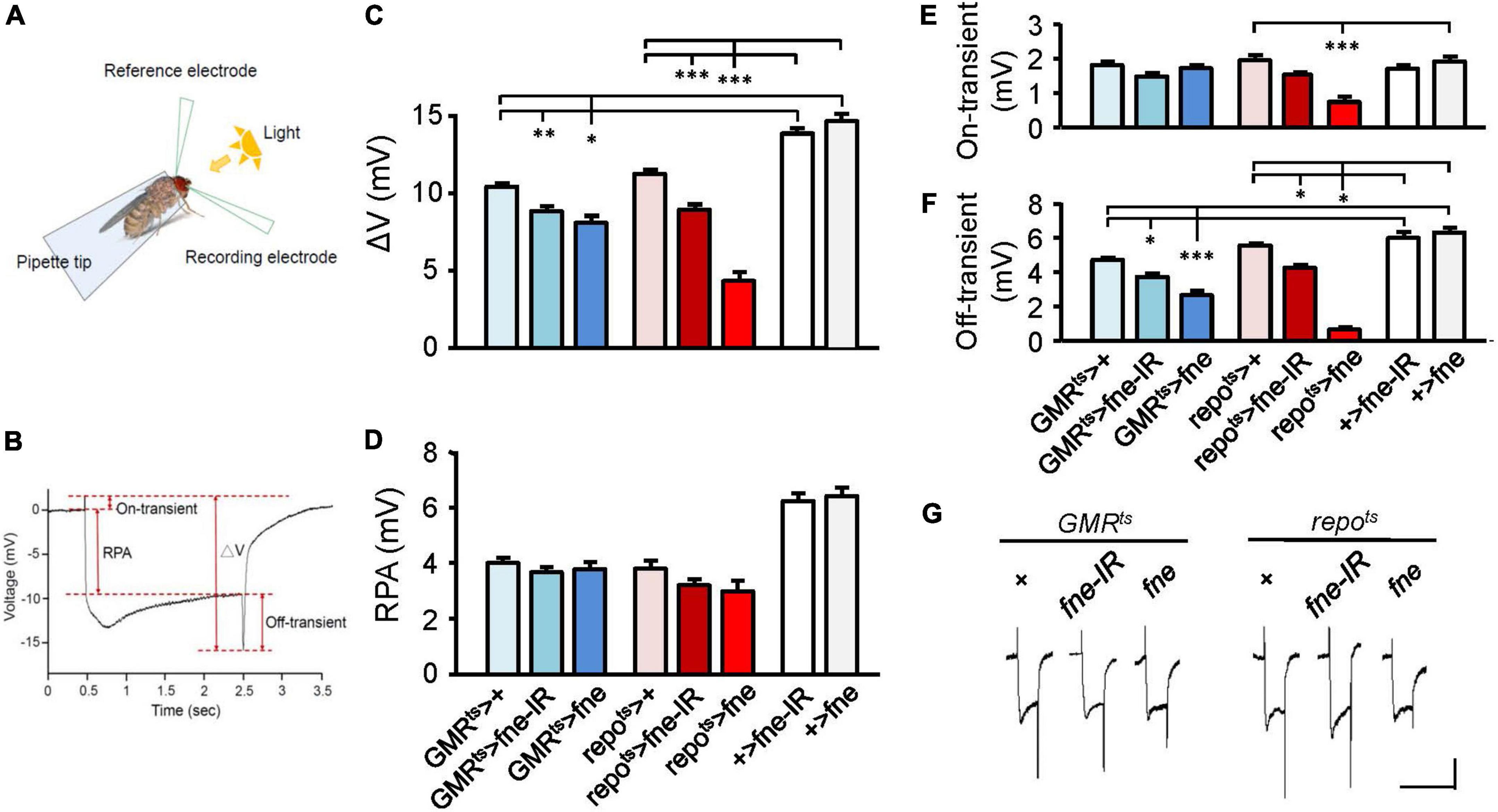

Photoreceptors respond to periodic light exposure by converting light signals into electric currents. A periodic electric signal can thus be recorded by an extracellular ERG (Figure 1A). The typical ERG waveform of a wild-type fly can be divided into four components (Figure 1B). The receptor potential amplitude (RPA) reflects the depolarization of the photoreceptors during stimulation with light. The on- and off-transient spikes, which occur at the beginning and end of a flash of light, respectively, indicate the successful transmission of a signal from photoreceptors to their postsynaptic partners in the lamina (Montell, 1999). The quantity ΔV represents the amplitude between on- and off-transient spikes.

Figure 1. fne is involved in the light-induced synaptic transmission in neurons and glia. (A) A schematic diagram of ERG recording. (B) The components of a representative ERG signal contain the ΔV (the difference between on- and off-transient spikes), receptor potential amplitude (RPA), and on-transient (highest peak from baseline) and off-transient (lowest peak from baseline) spikes. Quantification of (C) ΔV, (D) RPA, (E) on-transient, and (F) off-transient spikes. (G) The ERG trace of each genotype. Calibration: 2 mV, 5 s. Error bars represent SEM. n = 10 for each group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

To test whether fne affected light-evoked responses in the retina, we used GMRts and repots to temporally control fne and fne-IR expression in the photoreceptors and glia, respectively (Figures 1C–G). The photoreceptors expressing fne and fne-IR (GMRts > fne and GMRts > fne-IR) revealed slightly affected electric potential, as indicated by the smaller ΔV and off-transient amplitudes. The flies with fne and fne-IR expression in glia (repots > fne and repots > fne-IR) exhibited decreased ΔV, on- and off-transient amplitudes. These results indicate that fne affects neurotransmission in both photoreceptors and glia and that changes in fne expression in glia cause more severe ERG defect than in neurons.

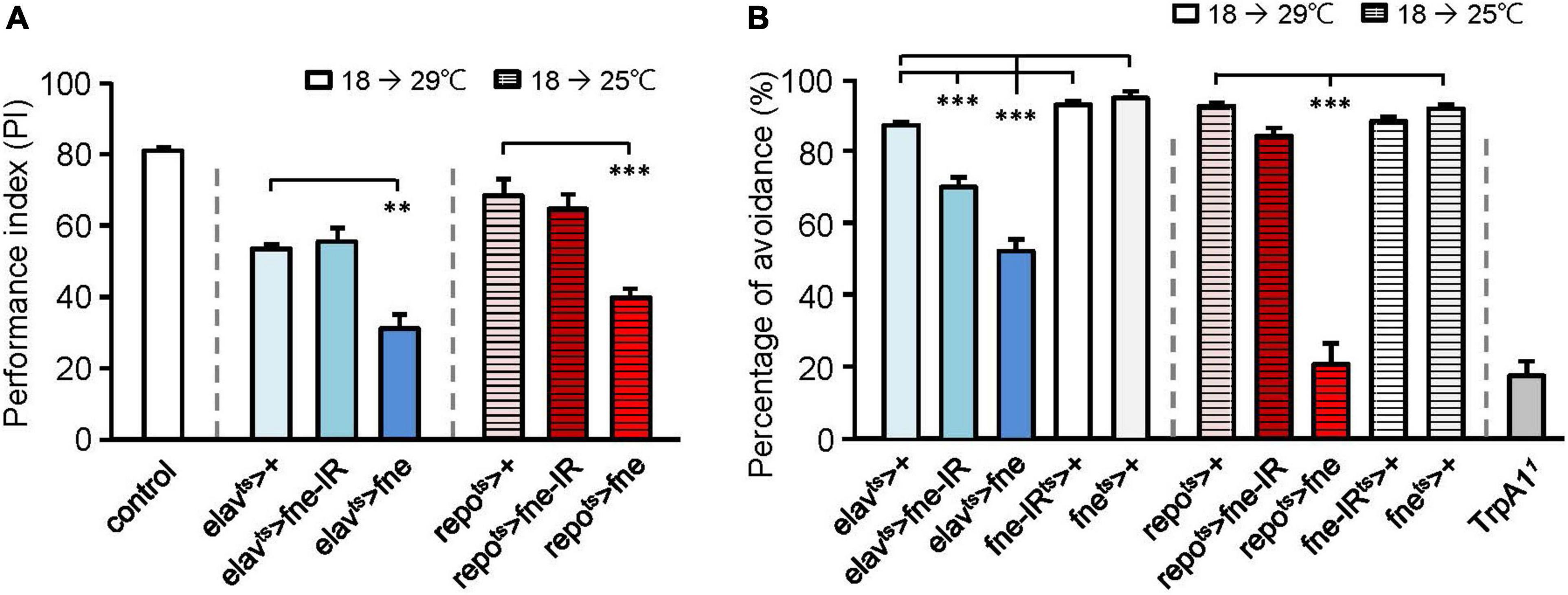

Overexpression of fne in neurons and glia impairs cognitive ability

Because changes in fne expression affect photoreceptor transmission, we attempted to determine the effects of fne on behavior. A single cycle of olfactory associative training was conducted to evaluate the learning performance index (PI; Figure 2A). After eclosion, the temperature was raised from 18 to 29°C for 10 days, and the flies started to overexpress (elavts > fne) or knockdown (elavts > fne-IR) fne in neurons. The PI of the elavts > fne-IR flies was similar to that of the control group (elavts > +, 55.5 ± 3.8 vs. 53.5 ± 1.1), but the elavts > fne flies exhibited a lower PI than did the control (31.1 ± 4.0, p < 0.01). We also evaluated learning ability when fne expression in glia began to change during the adult stage. Because the overexpression of fne in glia at 29°C caused extremely low viability, we kept the flies at a lower non-permissive temperature of 25°C for 14 days. Our data revealed that the repots > fne flies had significantly lower PIs than did the control flies (39.8 ± 2.5 vs. 68.4 ± 4.6, p < 0.001), but repots > fne-IR flies showed non-significant difference. These results indicate that the overexpression but not knockdown of fne both in neurons and glia impairs learning behavior.

Figure 2. Effects of fne on cognitive behavior and thermal nociception. (A) The learning PI of fne and fne-IR expressing in neurons and glia. The control fly is 25°C 5-day-old Canton-S strain for experimental calibration. n = 5–6 for each group. (B) The percentages of avoidance in response to noxious temperature of fne and fne-IR expressing in neurons and glia. The TrpA1 mutant (TrpA11) fly is a positive control (25°C, 5-day-old). n = 10 for each group. Error bars represent SEM. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Changes in fne expression reduce thermal sensation

Having determined that changing fne expression impairs cognitive ability, we tested another behavior, thermal nociception. When the flies were exposed to a noxious temperature (46°C) at the bottom surface of a peri dish chamber, they rapidly moved to the top, which had a subnoxious temperature, to avoid being harmed by the heat. A low percentage of avoidance indicated that the flies were less sensitive to the noxious heat (Neely et al., 2011). When fne and fne-IR were expressed in neurons at 29°C for 5 days, the percentages of avoidance appeared lower in the elavts > fne-IR and elavts > fne groups (69.4 ± 2.7% and 51.7 ± 3.3%, respectively) than in the control groups (elavts > +, 86.5 ± 1.0%; fne-IRts > +, 92.1 ± 1.0%; fnets > +, 94.1 ± 1.6%; Figure 2B). After eclosion, the flies were kept at 25°C for 10 days to express fne in the glia, and the percentage of avoidance for the repots > fne flies was 20.5 ± 5.8%, which were lower than the controls (repots > +, 91.8 ± 0.8%; fnets > +, 91.1 ± 1.0%; Figure 2B). In addition, knockdown of fne (repots > fne-IR) did not affect thermal sensation. Transient receptor potential cation channel A1 (TrpA1) is a nociceptor-related gene (Neely et al., 2011), and we used a TrpA1 mutant (TrpA11) as a positive control (avoidance rate was 17.3 ± 4.0%). Our data indicated that changes in fne expression in neurons and glia caused defects in thermal nociception, particularly in the flies with fne overexpression in glia.

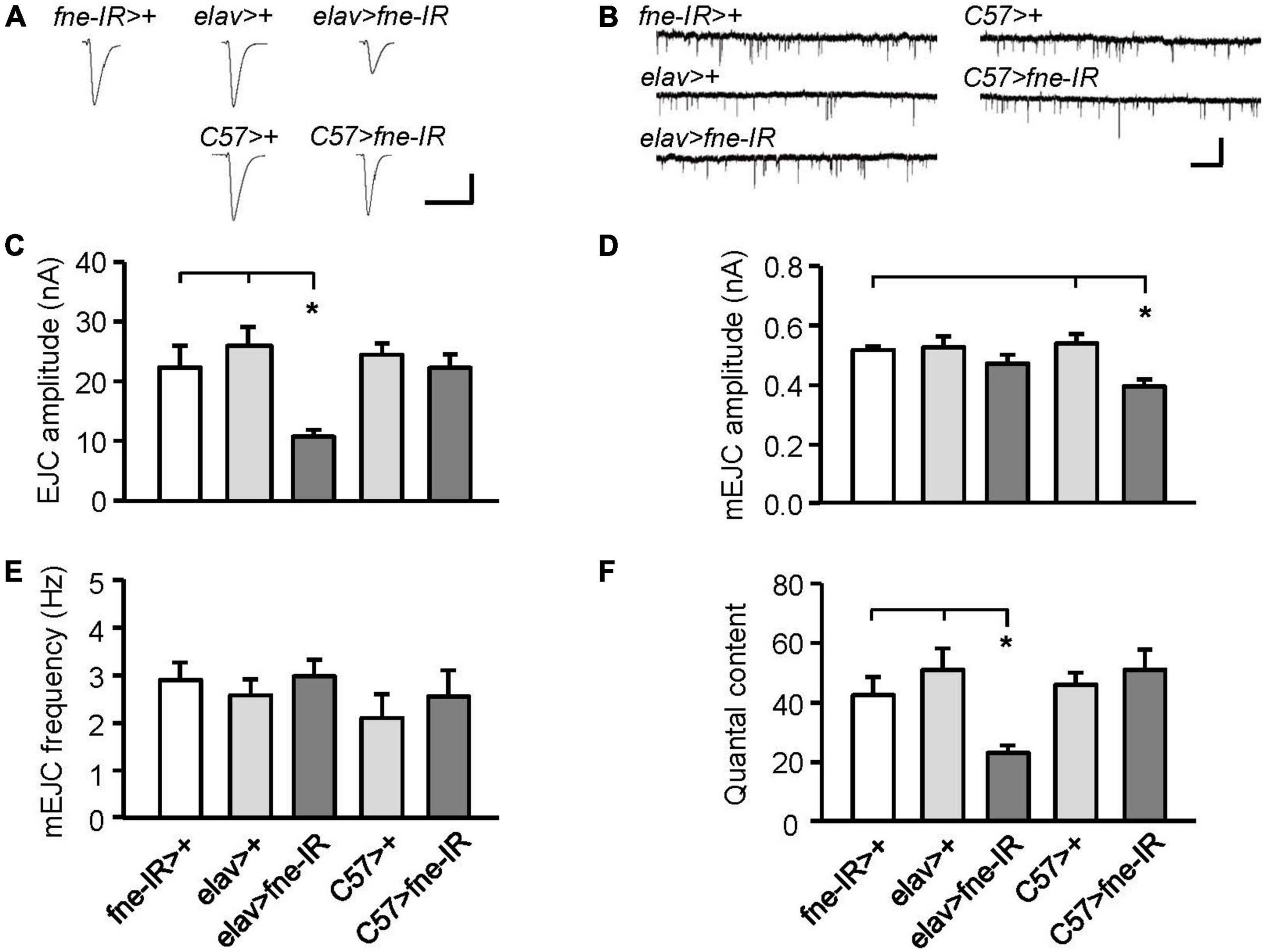

Impaired synaptic transmission of the larval neuromuscular junction in fne-knockdown flies

Changes in fne expression impaired phototransduction and adult behaviors, which might result from defective synaptic transmission. Thus, we performed an electrophysiological study of the third-instar larval NMJ for the effects of fne on synaptic transmission. Continuous recordings were made while the muscle fiber M12 was voltage clamped at –80 mV and segmental nerves innervating the muscle cell were stimulated by 0.05 Hz in a HL-3 solution containing 0.2 mM Ca2+ (Guo and Zhong, 2006). We examined an evoked EJC in the fne-knockdown flies (Figures 3A,C). The knockdown of fne in neurons (elav > fne-IR), which represents a presynaptic site of synaptic transmission, caused significantly smaller EJC amplitude (10.70 ± 1.16 nA) than the control flies (elav > + and fne-IR > +, 25.96 ± 3.13, and 22.31 ± 3.66 nA, respectively, p < 0.05). The knockdown of fne in muscle cells (C57 > fne-IR), which represents a postsynaptic site of synaptic transmission, caused no difference in the EJC amplitudes among the control flies (C57 > + and fne-IR > +). Because EJC amplitudes decreased only in the elav > fne-IR flies, it implies that their presynaptic function was affected.

Figure 3. Knockdown of fne in neurons and muscle cells altered synaptic transmission in the larval NMJ. (A) Representative traces of EJC in the indicated genotypes. Calibration: 10 nA, 50 ms. (B) Representative traces of mEJC in the indicated genotypes. Calibration: 1 nA, 1 s. Quantification of (C) EJC amplitude, (D) mEJC amplitude, (E) mEJC frequency, and (F) quantal content. Error bars represent SEM. *p < 0.05, n = 8 for each group.

Subsequently, we examined the amplitude and frequency of mEJCs to determine whether the spontaneous release of synaptic vesicles had changed (Figures 3B,D,E). The knockdown of fne in neurons did not alter the amplitude or frequency of the mEJCs. Only the mEJC amplitudes in the muscle cells expressing fne-IR (C57 > fne-IR) significantly decreased compared to the control flies (C57 > + and fne-IR > +, 0.40 ± 0.02 vs. 0.54 ± 0.03, and 0.52 ± 0.01 nA, respectively, p < 0.05). We also determined the quantal content, which reflects the number of vesicles released in response to a nerve impulse. A significant reduction in quantal content was observed in the elav > fne-IR flies (elav > fne-IR, 23.13 ± 2.50; elav > +, 50.99 ± 7.23; fne-IR > +, 42.53 ± 6.07, p < 0.05; Figure 3F).

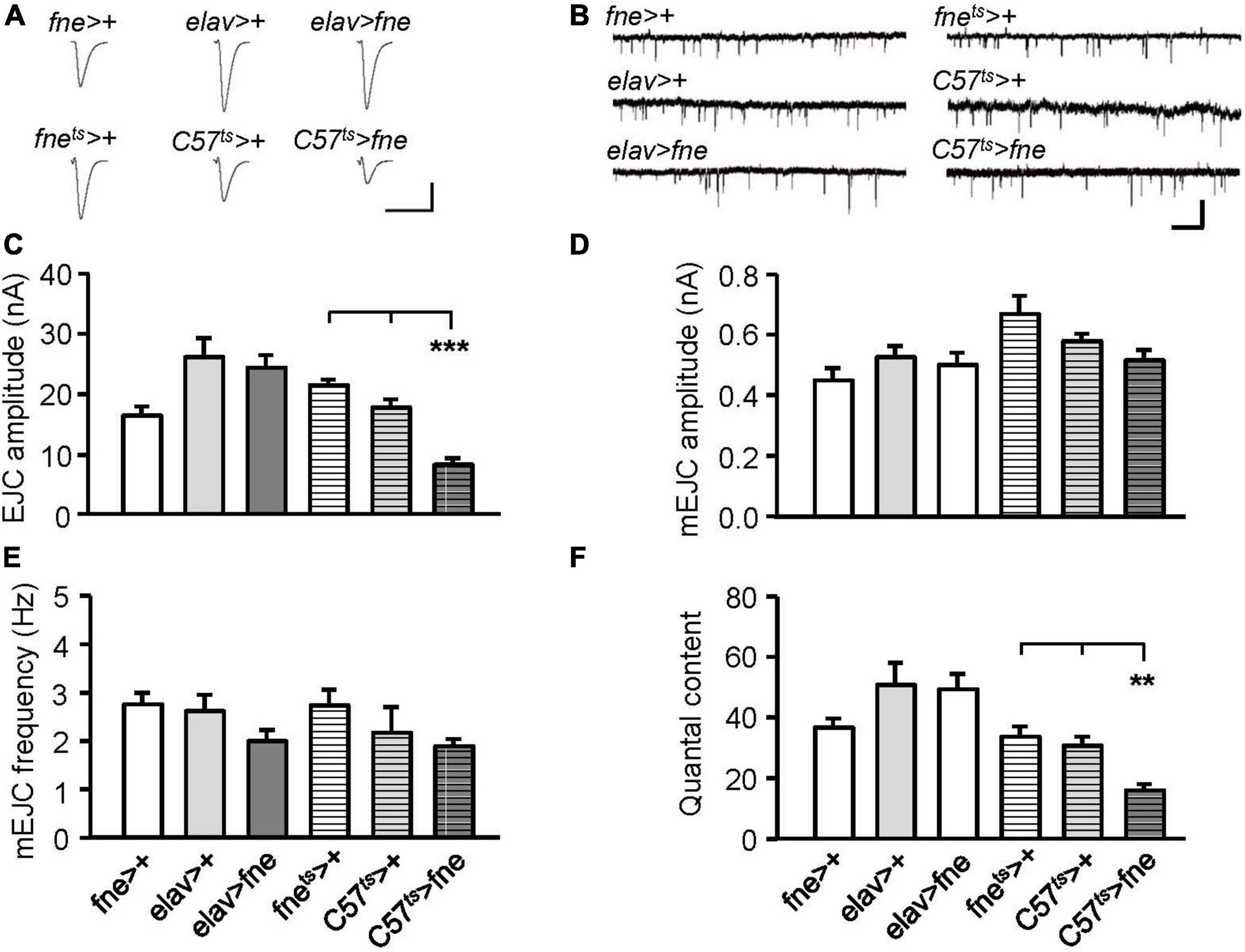

Impaired synaptic function of the larval neuromuscular junction in fne-overexpressed flies

We attempted to determine whether the overexpression of fne also affected synaptic transmission (Figures 4A,C). The overexpression of fne in muscle cells (C57ts > fne) caused significantly smaller EJCs (8.20 ± 1.02 nA) than the control flies (C57ts > + and fnets > +, 17.60 ± 1.39, and 21.36 ± 0.86 nA, respectively, p < 0.001). A significant reduction in quantal content was also observed in the C57ts > fne flies (C57ts > fne, 16.11 ± 1.99; C57ts > +, 30.90 ± 2.91; fnets > +, 33.95 ± 3.30, p < 0.01; Figure 4F). The overexpression of fne in neurons (elav > fne) resulted in the EJC amplitudes and quantal content being similar with those of the control flies (elav > + and fne > +). In addition, the amplitude and frequency of mEJCs in the flies overexpressing fne in neurons and muscle cells did not differ from those of the controls (Figures 4B,D,E), suggesting that spontaneous synaptic transmission and constitutive synaptic vesicle fusion was not affected by fne overexpression.

Figure 4. Overexpression of fne in muscle cells altered synaptic transmission in the larval NMJ. (A) Representative traces of EJC in the indicated genotypes. Calibration: 10 nA, 50 ms. (B) Representative traces of mEJC in the indicated genotypes. Calibration: 1 nA, 1 s. Quantification of (C) EJC amplitude, (D) mEJC amplitude, (E) mEJC frequency, and (F) quantal content. Bars with horizontal lines represented the flies that were reared at 18°C and shifted to 29°C for 1 day to induce fne expression. Error bars represent SEM. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, n = 8 for each group.

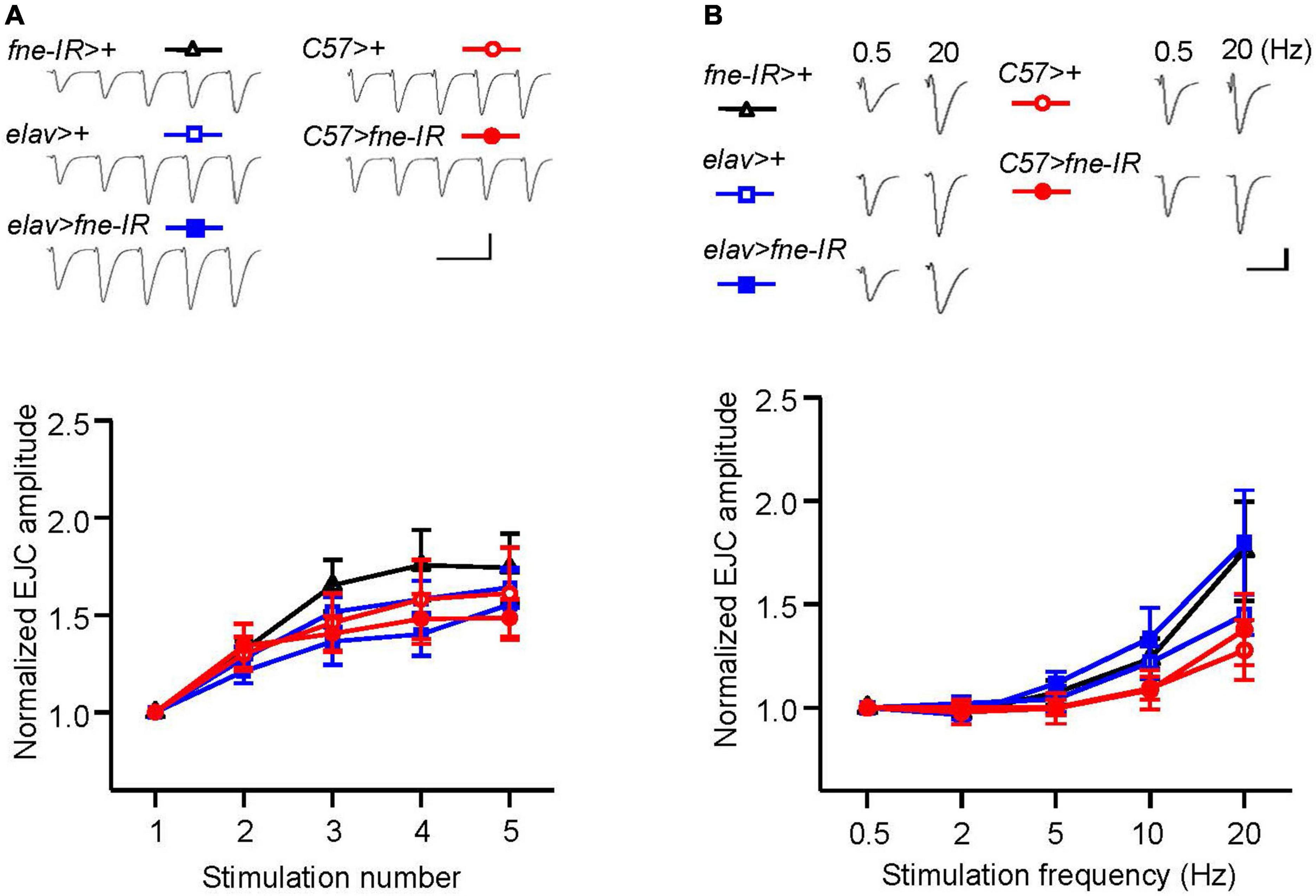

Knockdown of fne in the larval neuromuscular junction did not affect short-term synaptic plasticity

To determine whether fne is involved in short-term synaptic plasticity, we induced a short train of repetitive stimulation at 25 Hz after 5 min of baseline stimulation. The repetitive impulses affected the probability of neurotransmitter release and resulted in changes to synaptic efficacy over time, which reflected the electrical activity of the presynaptic terminals. Normal STF was observed in neurons and muscle cells expressing fne-IR (elav > fne-IR and C57 > fne-IR; control groups: elav > fne-IR vs. elav > + and fne-IR > +; C57 > fne-IR vs. C57 > +, and fne-IR > +, respectively; Figure 5A). We also induced the frequency dependence of STF by delivering various frequencies (0.5–20 Hz). The synaptic transmission properties were normal with increasing stimulation frequency in the knockdown of fne in neurons and muscle cells (elav > fne-IR and C57 > fne-IR; Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Knockdown of fne in neurons and muscle cells did not affect short-term synaptic facilitation in the larval NMJ. (A) STF during a short train of repetitive stimulation at 25 Hz in the wild type and in the knockdown of fne strains. Top, representative traces in the indicated genotypes. Bottom, summary of normalized EJC amplitude. (B) STF were determined at the various stimulation frequency of 0.5–20 Hz in the control and in the knockdown of fne strains. Top, representative traces of the EJCs for 0.5 and 20 Hz in the indicated genotypes. Bottom, summary of normalized EJC amplitude. Calibration: 10 nA, 50 ms. N = 8 for each group. Error bars represent SEM.

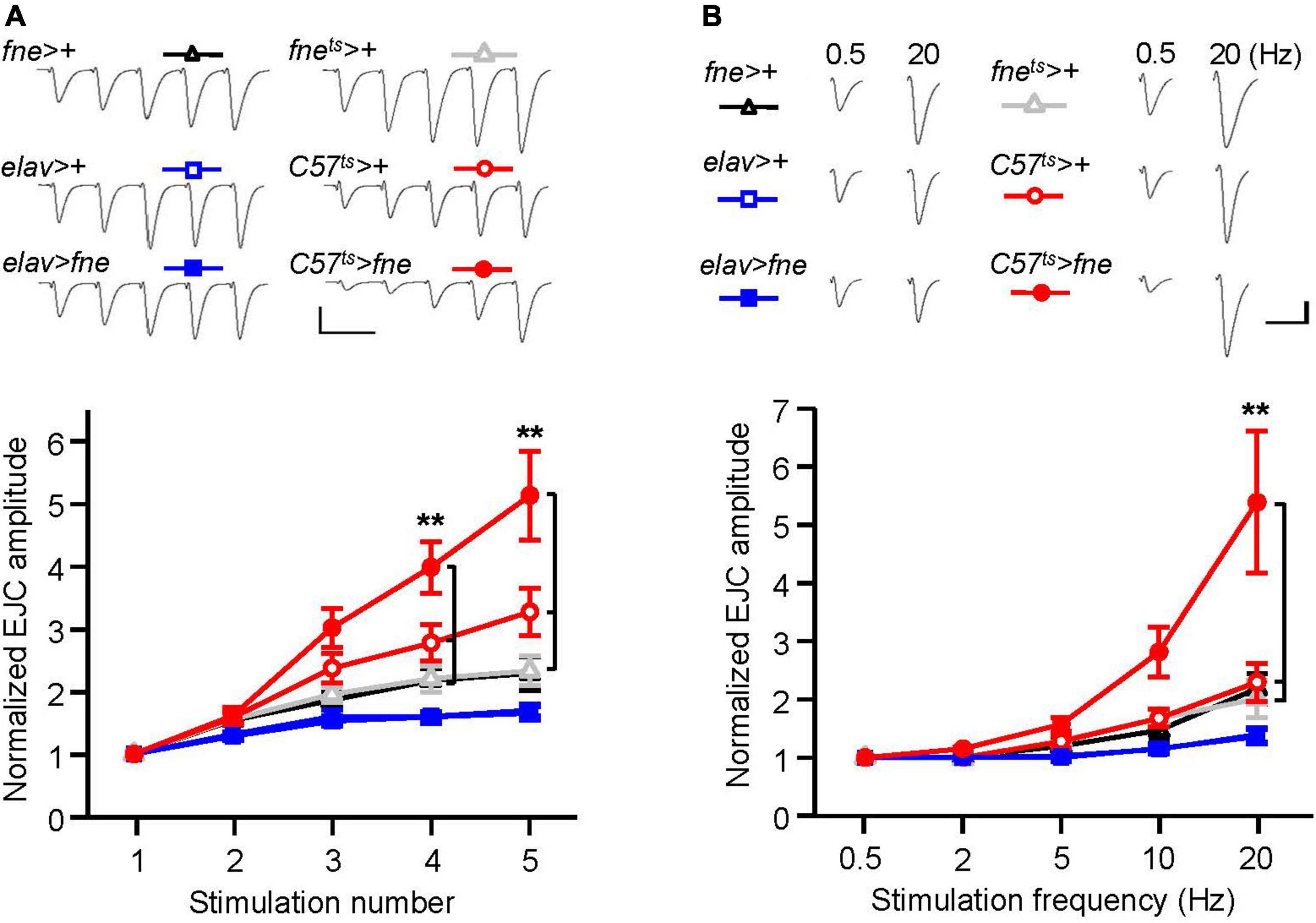

Overexpression of fne in muscle cells affected short-term synaptic plasticity

To determine whether the overexpression of fne was involved in short-term synaptic plasticity, we induced a short train of repetitive stimulation at 25 Hz in the fne- overexpressing flies. Normal STF was observed in the neurons expressing fne (elav > fne), but facilitation increased significantly for fne-expressing muscle cells, by approximately 5.1-fold after repetitive stimulation, relative to the controls (C57ts > fne vs. C57ts > + and fnets > +; Figure 6A). A frequency-dependent facilitation was also obtained by stimulating muscle cells (C57ts > fne), where the stimulation gradually increased in frequency from 0.5 to 20 Hz; however, no difference was observed in the neuronal fne-expressing flies (elav > fne; Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Overexpression of fne in muscle cells altered short-term synaptic facilitation in the larval NMJ. (A) STF during a short train of repetitive stimulation (25 Hz) in the wild type and in the overexpression of fne strains. Top, representative traces. Bottom, summary of normalized EJC amplitude. (B) STF were determined at the various stimulation frequency (0.5–20 Hz) in the control and in the overexpression of fne strains. Top, representative traces of the EJCs for 0.5 and 20 Hz in the indicated genotypes. Bottom, summary of normalized EJC amplitude. The C57ts > fne, C57ts > +, and fnets > + flies were reared at 18°C and shifted to 29°C for 1 day to induce fne expression. Calibration: 10 nA, 50 ms. n = 8 for each group. Error bars represent SEM. **p < 0.01.

These results indicated that the knockdown of fne in neurons reduced the amplitude of EJCs and quantal content, whereas the overexpression of fne in muscle cells reduced the amplitude of EJCs and quantal content and increased STF, suggesting that fne plays an important role in synaptic transmission and plasticity.

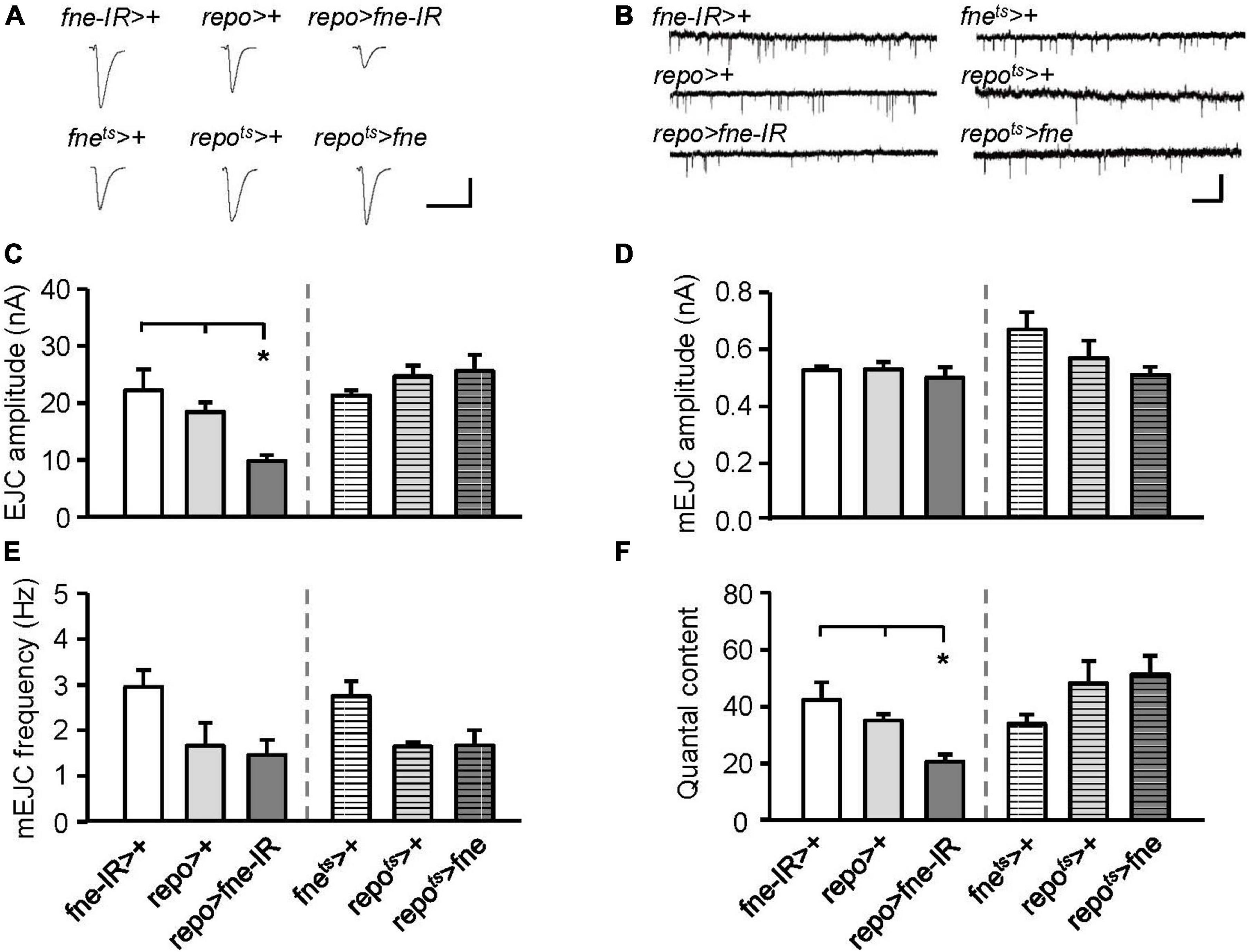

Knockdown of fne in glia affected synaptic transmission and short-term synaptic plasticity in the larval neuromuscular junction

Subsequently, we attempted to determine whether changes in fne expression in glia regulate synaptic transmission. The knockdown of fne in glia, rather than the overexpression of fne (repo > fne-IR), significantly reduced the amplitude of the EJCs in comparison with those of the EJCs of the controls (repo > + and fne-IR > +, 9.89 ± 1.03 vs. 18.53 ± 1.67 and 22.31 ± 3.66 nA, respectively, p < 0.05; Figures 7A,C). A significant reduction in quantal content was observed in the repo > fne-IR flies (repo > fne-IR, 20.83 ± 2.54 vs. repo > +, 35.35 ± 2.30; fne-IR > +, 42.53 ± 6.07, p < 0.05; Figure 7F). Changes in fne expression (repo > fne-IR and repots > fne) in glia did not cause the amplitude or frequency of the mEJCs to differ from those of the controls (Figures 7B,D,E).

Figure 7. Change of fne expression in glia altered the synaptic transmission in the larval NMJ. (A) Representative traces of EJC while the glia expressing fne and fne-IR. Calibration: 10 nA, 50 ms. (B) Representative traces of mEJC in the indicated genotypes. Calibration: 1 nA, 1 s. Quantification of (C) EJC amplitude, (D) mEJC amplitude, (E) mEJC frequency, and (F) quantal content. Bars with horizontal lines represented the flies that were reared at 18°C and shifted to 29°C for 1 day to induce fne expression. Error bars represent SEM. *p < 0.05, n = 8 for each group.

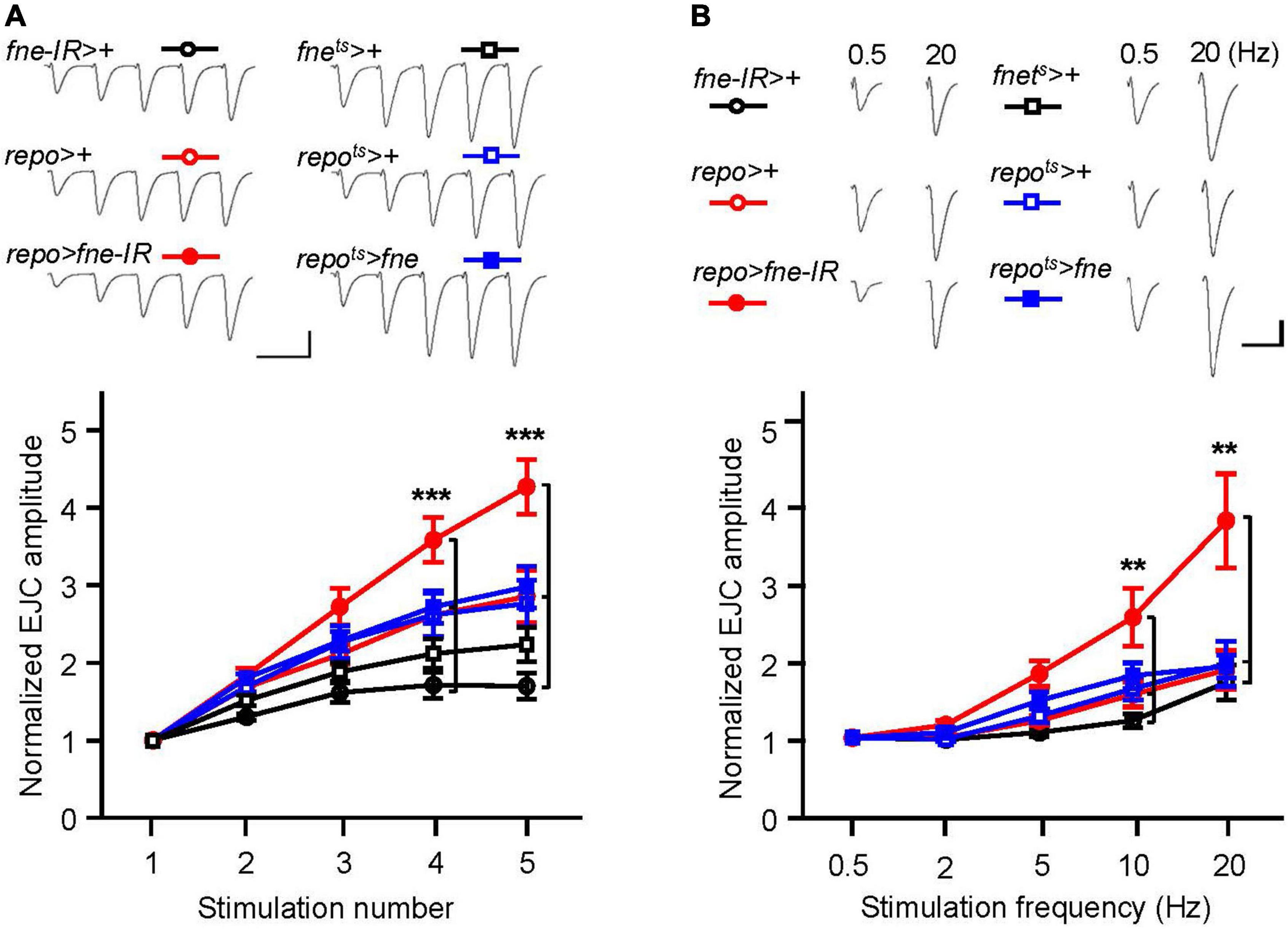

To determine whether changes in fne in glia are involved in short-term synaptic plasticity, we induced a short train of repetitive stimulation at 25 Hz. A significant increase in STF, approximately 4.5-fold, occurred after repetitive stimulation for fne-IR expression in glia (repo > fne-IR). However, a normal STF was observed in the fne-overexpressing flies (repots > fne; Figure 8A). In addition, when STF was induced at 0.5–20 Hz, synaptic transmission revealed a frequency-dependent facilitation in the glial fne-knockdown flies (repo > fne-IR). This phenomenon was not observed in flies with fne overexpression in glia (repots > fne; Figure 8B). The results indicated that the knockdown rather than overexpression of fne in glia reduced the amplitudes of EJCs and quantal content and increased STF, suggesting that fne in glia has an important role in synaptic transmission and plasticity.

Figure 8. Change of fne expression in glia altered short-term synaptic facilitation in the larval NMJ. (A) STF during a short train of repetitive stimulation (25 Hz) in the control and in the glia expressing fne and fne-IR. Top, representative traces. Bottom, summary of normalized EJC amplitude. (B) STF were determined at the various stimulation frequency (0.5–20 Hz) in the control and in the glia expressing fne and fne-IR. Top, representative traces of the EJCs for 0.5 and 20 Hz in the indicated genotypes. Bottom, summary of normalized EJC amplitude. The repots > fne, repots > +, and fnets > + flies were reared at 18°C and shifted to 29°C for 1 day to induce fne expression. Calibration: 10 nA, 50 ms. n = 8 for each group. Error bars represent SEM. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

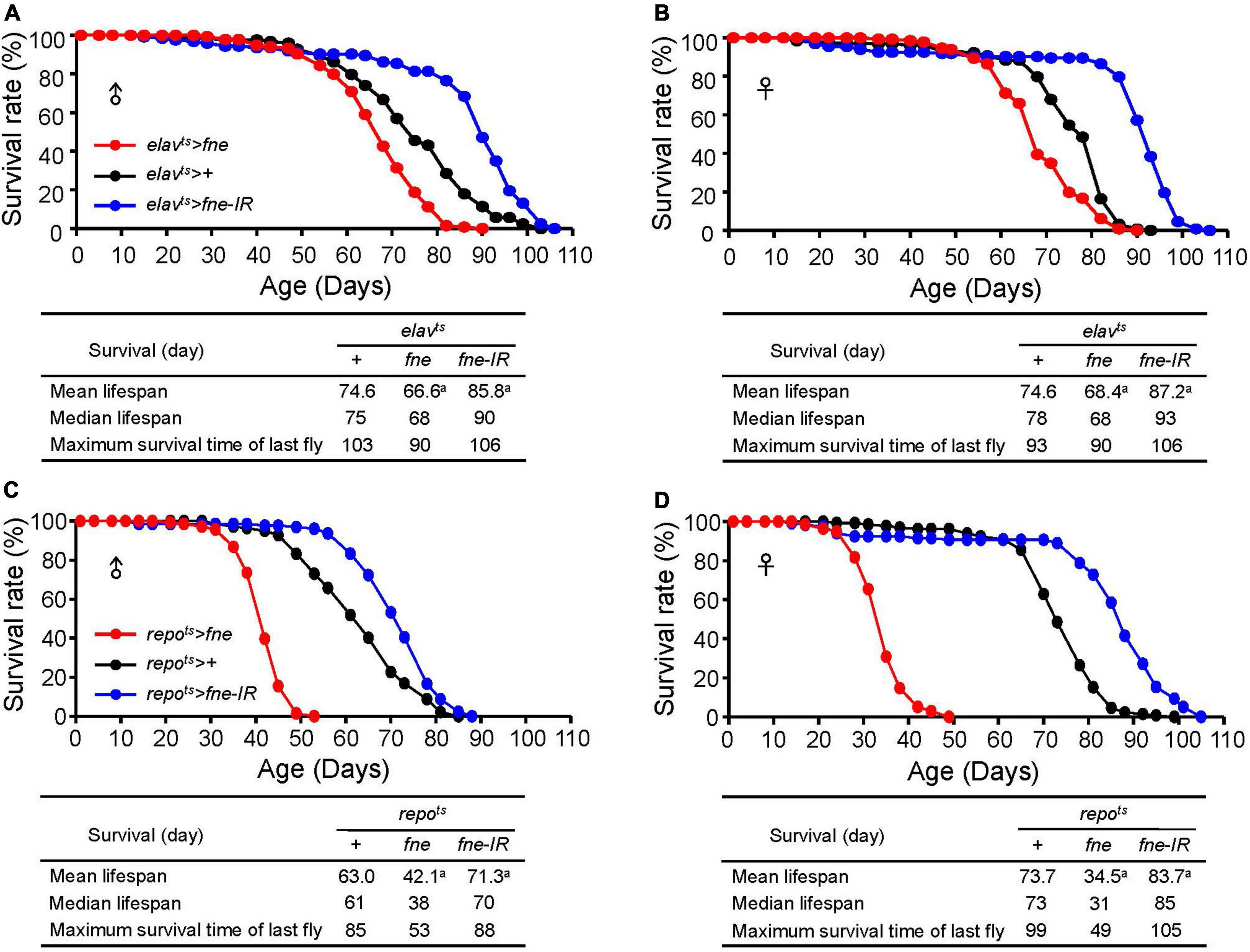

Changes of fne expression altered fly lifespan

To examine whether changes of fne expression can alter fly lifespan, we expressed fne and fne-IR in neurons and glia started at adult stage under elavts and repots drivers, respectively, and measured their lifespan. Expression pattern of elav-GAL4 and repo-GAL4 lines was verified by crossing to a UAS-GFP (Supplementary Figure 2). As shown in Figures 9A,B, the mean lifespan decreased by 10.7 and 8.3% when overexpressing fne in neurons of male and female flies, respectively. Conversely, knockdown of fne expression in neurons increased up to 15.0 and 16.9% lifespan in both males and females, respectively. Similar results also observed when changing fne expression in glia (Figures 9C,D). The mean lifespan of repots > fne flies significantly decreased by 33.2 and 53.2% in males and females, respectively, and in repots > fne-IR flies, the mean lifespan was extended in both gender by 13.2% (males) and 13.6% (females). Our results suggest that changes of fne expression could alter fly lifespan. In particular, knockdown of fne expression in both neurons and glia started from the adult stage seems to appear a beneficial effect on longevity in both male and female flies.

Figure 9. Effects of fne expression on the lifespan in neurons and glia. The survival curve of overexpression and knockdown of fne in neurons. Data represent the total lifespan of examined (A) male and (B) female flies. The genotypes of each group are elavts > fne (red circle), elavts > + (black circle), and elavts > fne-IR (blue circle). The total lifespan of overexpression and knockdown of fne in glia represents in (C) male and (D) female flies. The genotypes of each group are repots > fne (red circle), repots > + (black circle), and repots > fne-IR (blue circle). Flies were reared at 18°C and transferred to 25°C after eclosion to induce fne and fne-IR expression. Total n = 120–130 for each group. Data are significantly different from the control at ap < 0.001.

Discussion

The ELAV family of proteins have been determined to perform post-transcriptional processes and mediate important roles in the Drosophila nervous system. For example, neural-specific target transcripts, erect wing, neuroglian, and armadillo, which can interact with ELAV’s RRMs, are essential for the development and maintenance of neuronal function (Koushika et al., 2000). At least two target transcripts, extramacrochaetae and bag-of-marbles, are regulated by the RBP9 protein and regulate neuron and germ cell differentiation, respectively (Park et al., 1998; Kim-Ha et al., 1999). Few reports have identified the target transcripts of the FNE protein, and one target, Basigin, which encodes a cell adhesion molecule, accounts for the dendritic growth, and arborization in class IV da neurons during larval development (Alizzi et al., 2020). Little is known about the function of fne in neuronal plasticity. Recently, the knockdown of fne in muscle cells decreased the mEJC amplitudes. Changes in mEJCs can occur presynaptically (e.g., change in the number of neurotransmitters packed into a vesicle) or postsynaptically (e.g., change in the sensitivity of postsynaptic receptors). The overexpression of fne in muscle cells decreased the EJC amplitudes and quantal content and increased STF (all occurred presynaptically). Muscle-specific changes in fne expression affected neurotransmission, majorly on the presynaptic side. One possible mechanism is that FNE regulates the postsynaptic activity of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) through 3’UTR APA (Tiruchinapalli et al., 2008; Kuklin et al., 2017; Wei and Lai, 2022) and indirect alteration of CaMKII activity affects retrograde control of homeostasis of neurotransmitter release (Haghighi et al., 2003).

In addition, the loss of neuronal and glial fne resulted in presynaptic defects in neurotransmission, including smaller EJC amplitudes and quantal content, whereas normal transmission was observed in the overexpression of neuronal and glial fne. The loss of glial fne also increased STF (a presynaptic property), suggesting that fne is a critical regulator of neuronal transmission and synaptic plasticity. Several reports have characterized the role of glia in the PNS of Drosophila. The perineurial glial cells clear presynaptic debris through phagocytosis to modulate neuronal branching and shape synaptic connections during development or to do so in an activity-dependent manner (Fuentes-Medel et al., 2009). One purposed mechanism of glial fne in the regulation of synaptic transmission is through genderblind (gb). fne mutant affects 3’UTR APA of gb (Wei et al., 2020). Disruption of perineurial glial gb causes a reduction in extracellular free glutamate and results in increased postsynaptic glutamate receptor clustering and long-term strengthening of glutamatergic synapses at the NMJ (Sigrist et al., 2002; Augustin et al., 2007). Thus, glial cells also contribute to homeostatic plasticity, a process that modulates the presynaptic release of neurotransmitters, which is considered a compensatory response to the loss or inhibition of postsynaptic receptors (Wang et al., 2020). By converging the modulation of synaptic transmission with neurons, glial fne expression can influence neurotransmission between presynaptic and postsynaptic cells.

Although the ELAVL/Hu protein family has been determined to regulate neuronal development and differentiation, few reports have described their function in the retina. Amato et al. (2005) demonstrated the distribution of three members of the ELAVL/Hu family in Xenopus retinogenesis during retinal development, and Pacal and Bremner (2012) identified the expression patterns of Elavl2/3/4 in a developing murine retina. Elavl2 was also identified to express in retinal cells during retinogenesis and ablation of Elavl2 leads to deficit in ERG responses and visual acuity (Wu et al., 2021). The elav of Drosophila expresses in the imaginal disc of the larval eye and the adult optic lobe (Robinow and White, 1988). We found changes in the level of fne expression in both photoreceptors and glia beginning at the adult stage altered light-evoked synaptic potential. In the visual system of adult Drosophila, light stimuli depolarize photoreceptors to induce the release of histamines and activate postsynaptic receptors, histamine-gated Cl– channels, on the lamina neurons (Chaturvedi et al., 2014). The ERG response can be modulated by the surrounding epithelial glia through the removal of histamines from the synaptic cleft (Stuart et al., 2007; Chaturvedi et al., 2014). Thus, for the retina, changes in fne expression in glia cause more severe defects than in neurons, particularly for the on- and off-transient amplitudes, suggesting a significant role of glial fne in phototransduction.

A study from Ustaoglu et al. (2021) found that elavl2 is required for learning and memory consolidation in honey bees. Another study showed that ELAVL2-regulated transcriptional and splicing networks in human neurons including RBFOX1 and FMRP-related pathway are involved in synaptic function and neural development (Berto et al., 2016). These results highlight ELAVL/Hu’s regulator of important neuronal pathways. For the lifespan experiment, our data showed that knockdown of fne in neurons and glia could cause the lifespan extension in both genders. However, genetic background effects might produce variable lifespan results, since we did not backcross at least 6 generations to produce the isogenic UAS strains (Piper and Partridge, 2016). Thus, we provided the tentative conclusion and further exploration need to be done for lifespan.

For the orthologs of fne in humans, FNE strongly shares its amino acid identity with ELAVL2/HuB and ELAVL4/HuD (Samson and Chalvet, 2003). Studies have indicated that ELAVL2/HuB and ELAVL4/HuD are highly enriched in the neuronal lineage but absent in glial cells (King et al., 1994; Mirisis and Carew, 2019; Hilgers, 2022). Defects in ELAVL2/HuB, ELAVL4/HuD, and their target transcripts can lead to abnormal neuronal proliferation and development and result in the pathogenesis of numerous CNS disorders, including seizures, autism, and schizophrenia (Yamada et al., 2011; Bronicki and Jasmin, 2013; Berto et al., 2016; Zybura-Broda et al., 2018). Silencing ELAVL1/HuR, which also shares high amino acid identity with FNE (Samson and Chalvet, 2003) in the activated microglia and astrocytes attenuate neuroinflammation and the occurrence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Borgonetti et al., 2021). Thus, we conducted a bioinformatic analysis of ELAVL2/HuB and ELAVL4/HuD in neurons and glia from published gene expression datasets of human, mice, and rat samples. Two genes are expressed in all types of glia and neurons at similar levels (Supplementary Table 1). Similar human’s results also observed in the database of The Human Protein Atlas (Digre and Lindskog, 2021).

In the present, we found changes in the level of fne expression in neurons and glia affected phototransduction, adult behaviors, synaptic transmission of larval NMJ, and could influence the lifespan. Although the Drosophila ELAV protein can be detected in the majority of neurons, Berger et al. (2007) demonstrated that ELAV can transiently express in early embryonic glial cells but not in adults. The expression of fne in glia has never been reported. Our findings highlighted the important fne’s function not only in neurons but also in glia. As FNE is an RNA-binding protein, homeostatic maintenance of FNE stability and its downstream multiple pathways through target transcripts is crucial for brain activities. Further explorations into the physiological and molecular functions of glial fne are expected to clarify certain Drosophila behaviors, which may also be a feature of mammal brains.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

W-YL and H-PL wrote the manuscript. C-HL, W-YL, and H-PL performed the experiments. JC carried out the bioinformatic analysis. H-PL supervised the research and funding acquisition. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the China Medical University (CMU108-MF-61, CMU109-MF-110, and CMU110-MF-92) and the National Science and Technology Council in Taiwan (MOST 108-2320-B-039-031-MY3, MOST 109-2314-B-039-030, and MOST 111-2314-B-039-017-MY3).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnmol.2022.1006455/full#supplementary-material

References

Alizzi, R. A., Xu, D., Tenenbaum, C. M., Wang, W., and Gavis, E. R. (2020). The ELAV/Hu protein Found in neurons regulates cytoskeletal and ECM adhesion inputs for space-filling dendrite growth. PLoS Genet. 16:e1009235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009235

Amato, M. A., Boy, S., Arnault, E., Girard, M., Della Puppa, A., Sharif, A., et al. (2005). Comparison of the expression patterns of five neural RNA binding proteins in the Xenopus retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 481, 331–339. doi: 10.1002/cne.20387

Augustin, H., Grosjean, Y., Chen, K., Sheng, Q., and Featherstone, D. E. (2007). Nonvesicular release of glutamate by glial xCT transporters suppresses glutamate receptor clustering in vivo. J. Neurosci. 27, 111–123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4770-06.2007

Berger, C., Renner, S., Luer, K., and Technau, G. M. (2007). The commonly used marker ELAV is transiently expressed in neuroblasts and glial cells in the Drosophila embryonic CNS. Dev. Dyn. 236, 3562–3568. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21372

Berto, S., Usui, N., Konopka, G., and Fogel, B. L. (2016). ELAVL2-regulated transcriptional and splicing networks in human neurons link neurodevelopment and autism. Hum. Mol. Genet. 25, 2451–2464. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw110

Borgonetti, V., Coppi, E., and Galeotti, N. (2021). Targeting the RNA-binding protein HuR as potential thera-peutic approach for neurological disorders: Focus on amyo-trophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), spinal muscle atrophy (SMA) and multiple sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22:10394. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910394

Bronicki, L. M., and Jasmin, B. J. (2013). Emerging complexity of the HuD/ELAVl4 gene; implications for neuronal development, function, and dysfunction. RNA 19, 1019–1037. doi: 10.1261/rna.039164.113

Carrasco, J., Rauer, M., Hummel, B., Grzejda, D., Alfonso-Gonzalez, C., Lee, Y., et al. (2020). ELAV and FNE determine neuronal transcript signatures through EXon-activated rescue. Mol. Cell 15:e156. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.09.011

Chalvet, F., and Samson, M. L. (2002). Characterization of fly strains permitting GAL4-directed expression of found in neurons. Genesis 34, 71–73. doi: 10.1002/gene.10108

Chaturvedi, R., Reddig, K., and Li, H. S. (2014). Long-distance mechanism of neurotransmitter recycling mediated by glial network facilitates visual function in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 2812–2817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323714111

Colombrita, C., Silani, V., and Ratti, A. (2013). ELAV proteins along evolution: Back to the nucleus? Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 56, 447–455. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2013.02.003

Cosens, D. J., and Manning, A. (1969). Abnormal electroretinogram from a Drosophila mutant. Nature 224, 285–287. doi: 10.1038/224285a0

Digre, A., and Lindskog, C. (2021). The human protein atlas-spatial localization of the human proteome in health and disease. Protein Sci. 30, 218–233. doi: 10.1002/pro.3987

Dubnau, J., Grady, L., Kitamoto, T., and Tully, T. (2001). Disruption of neurotransmission in Drosophila mushroom body blocks retrieval but not acquisition of memory. Nature 411, 476–480. doi: 10.1038/35078077

Edwards, T. N., and Meinertzhagen, I. A. (2010). The functional organisation of glia in the adult brain of Drosophila and other insects. Prog. Neurobiol. 90, 471–497. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.01.001

Fuentes-Medel, Y., Logan, M. A., Ashley, J., Ataman, B., Budnik, V., and Freeman, M. R. (2009). Glia and muscle sculpt neuromuscular arbors by engulfing destabilized synaptic boutons and shed presynaptic debris. PLoS Biol. 7:e1000184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000184

Guo, H. F., and Zhong, Y. (2006). Requirement of Akt to mediate long-term synaptic depression in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 26, 4004–4014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3616-05.2006

Haghighi, A. P., McCabe, B. D., Fetter, R. D., Palmer, J. E., Hom, S., and Goodman, C. S. (2003). Retrograde control of synaptic transmission by postsynaptic CaMKII at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Neuron 39, 255–267. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00427-6

Hilgers, V. (2022). Regulation of neuronal RNA signatures by ELAV/Hu proteins. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA e1733. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1733 [Epub ahead of print].

Jimenez, F., and Campos-Ortega, J. A. (1987). Genes in subdivision 1B of the Drosophila melanogaster X-chromosome and their influence on neural development. J. Neurogenet. 4, 179–200.

Kim, J., Kim, Y. J., and Kim-Ha, J. (2010). Blood-brain barrier defects associated with Rbp9 mutation. Mol. Cells 29, 93–98. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0040-0

Kim-Ha, J., Kim, J., and Kim, Y. J. (1999). Requirement of RBP9, a Drosophila Hu homolog, for regulation of cystocyte differentiation and oocyte determination during oogenesis. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 2505–2514. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2505

King, P. H., Levine, T. D., Fremeau, R. T. Jr., and Keene, J. D. (1994). Mammalian homologs of Drosophila ELAV localized to a neuronal subset can bind in vitro to the 3’ UTR of mRNA encoding the Id transcriptional repressor. J. Neurosci. 14, 1943–1952. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-01943.1994

Koushika, S. P., Lisbin, M. J., and White, K. (1996). ELAV, a Drosophila neuron-specific protein, mediates the generation of an alternatively spliced neural protein isoform. Curr. Biol. 6, 1634–1641. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70787-2

Koushika, S. P., Soller, M., and White, K. (2000). The neuron-enriched splicing pattern of Drosophila erect wing is dependent on the presence of ELAV protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 1836–1845. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1836-1845.2000

Kuklin, E. A., Alkins, S., Bakthavachalu, B., Genco, M. C., Sudhakaran, I., Raghavan, K. V., et al. (2017). The long 3’UTR mRNA of CaMKII is essential for translation-dependent plasticity of spontaneous release in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Neurosci. 37, 10554–10566. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1313-17.2017

Logan, M. A. (2017). Glial contributions to neuronal health and disease: New insights from Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 47, 162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.10.008

McGuire, S. E., Mao, Z., and Davis, R. L. (2004). Spatiotemporal gene expression targeting with the TARGET and gene-switch systems in Drosophila. Sci. STKE 2004:l6. doi: 10.1126/stke.2202004pl6

Mirisis, A. A., and Carew, T. J. (2019). The ELAV family of RNA-binding proteins in synaptic plasticity and long-term memory. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 161, 143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2019.04.007

Montell, C. (1999). Visual transduction in Drosophila. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 15, 231–268. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.231

Nagai, J., Yu, X., Papouin, T., Cheong, E., Freeman, M. R., Monk, K. R., et al. (2021). Behaviorally consequential astrocytic regulation of neural circuits. Neuron 109, 576–596. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.12.008

Neely, G. G., Keene, A. C., Duchek, P., Chang, E. C., Wang, Q. P., Aksoy, Y. A., et al. (2011). TrpA1 regulates thermal nociception in Drosophila. PLoS One 6:e24343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024343

Ou, J., He, Y., Xiao, X., Yu, T. M., Chen, C., Gao, Z., et al. (2014). Glial cells in neuronal development: Recent advances and insights from Drosophila melanogaster. Neurosci. Bull. 30, 584–594. doi: 10.1007/s12264-014-1448-2

Pacal, M., and Bremner, R. (2012). Mapping differentiation kinetics in the mouse retina reveals an extensive period of cell cycle protein expression in post-mitotic newborn neurons. Dev. Dyn. 241, 1525–1544. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23840

Park, S. J., Yang, E. S., Kim-Ha, J., and Kim, Y. J. (1998). Down regulation of extramacrochaetae mRNA by a Drosophila neural RNA binding protein Rbp9 which is homologous to human Hu proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 2989–2994. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.12.2989

Piper, M. D., and Partridge, L. (2016). Protocols to study aging in Drosophila. Methods Mol. Biol. 1478, 291–302. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6371-3_18

Robinow, S., and White, K. (1988). The locus elav of Drosophila melanogaster is expressed in neurons at all developmental stages. Dev. Biol. 126, 294–303. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90139-x

Samson, M. L. (2008). Rapid functional diversification in the structurally conserved ELAV family of neuronal RNA binding proteins. BMC Genomics 9:392. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-392

Samson, M. L., and Chalvet, F. (2003). found in neurons, a third member of the Drosophila elav gene family, encodes a neuronal protein and interacts with elav. Mech. Dev. 120, 373–383. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00444-6

Sigrist, S. J., Thiel, P. R., Reiff, D. F., and Schuster, C. M. (2002). The postsynaptic glutamate receptor subunit DGluR-IIA mediates long-term plasticity in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 22, 7362–7372. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07362.2002

Stuart, A. E., Borycz, J., and Meinertzhagen, I. A. (2007). The dynamics of signaling at the histaminergic photoreceptor synapse of arthropods. Prog. Neurobiol. 82, 202–227. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.03.006

Sun, X., Yang, H., Sturgill, D., Oliver, B., Rabinow, L., and Samson, M. L. (2015). Sxl-Dependent, tra/tra2-independent alternative splicing of the Drosophila melanogaster X-linked gene found in neurons. G3 (Bethesda) 5, 2865–2874. doi: 10.1534/g3.115.023721

Tiruchinapalli, D. M., Ehlers, M. D., and Keene, J. D. (2008). Activity-dependent expression of RNA binding protein HuD and its association with mRNAs in neurons. RNA Biol. 5, 157–168. doi: 10.4161/rna.5.3.6782

Ustaoglu, P., Gill, J. K., Doubovetzky, N., Haussmann, I. U., Dix, T. C., Arnold, R., et al. (2021). Dynamically expressed single ELAV/Hu orthologue elavl2 of bees is required for learning and memory. Commun. Biol. 4:1234. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02763-1

Wang, T., Morency, D. T., Harris, N., and Davis, G. W. (2020). Epigenetic signaling in glia controls presynaptic homeostatic plasticity. Neuron 105, 491–505.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.10.041

Wei, L., and Lai, E. C. (2022). Regulation of the alternative neural transcriptome by ELAV/Hu RNA binding proteins. Front. Genet. 13:848626. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.848626

Wei, L., Lee, S., Majumdar, S., Zhang, B., Sanfilippo, P., Joseph, B., et al. (2020). Overlapping activities of ELAV/Hu Family RNA binding proteins specify the extended neuronal 3’ UTR landscape in Drosophila. Mol. Cell 14:e146. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.09.007

Wu, M., Deng, Q., Lei, X., Du, Y., and Shen, Y. (2021). Elavl2 regulates retinal function via modulating the differentiation of amacrine cells subtype. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 62:1. doi: 10.1167/iovs.62.7.1

Yamada, K., Iwayama, Y., Hattori, E., Iwamoto, K., Toyota, T., Ohnishi, T., et al. (2011). Genome-wide association study of schizophrenia in Japanese population. PLoS One 6:e20468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020468

Yildirim, K., Petri, J., Kottmeier, R., and Klambt, C. (2019). Drosophila glia: Few cell types and many conserved functions. Glia 67, 5–26. doi: 10.1002/glia.23459

Zanini, D., Jallon, J. M., Rabinow, L., and Samson, M. L. (2012). Deletion of the Drosophila neuronal gene found in neurons disrupts brain anatomy and male courtship. Genes Brain Behav. 11, 819–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2012.00817.x

Zybura-Broda, K., Wolder-Gontarek, M., Ambrozek-Latecka, M., Choros, A., Bogusz, A., Wilemska-Dziaduszycka, J., et al. (2018). HuR (Elavl1) and HuB (Elavl2) stabilize matrix metalloproteinase-9 mRNA during seizure-induced Mmp-9 expression in neurons. Front. Neurosci. 12:224. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00224

Keywords: fne, RNA-binding protein, neuron, glia, synaptic plasticity

Citation: Lin W-Y, Liu C-H, Cheng J and Liu H-P (2022) Alterations of RNA-binding protein found in neurons in Drosophila neurons and glia influence synaptic transmission and lifespan. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 15:1006455. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2022.1006455

Received: 29 July 2022; Accepted: 24 October 2022;

Published: 11 November 2022.

Edited by:

Haiyun Xu, Wenzhou Medical University, ChinaReviewed by:

Francois Rouyer, UMR 9197 Institut des Neurosciences Paris Saclay (Neuro-PSI), FranceHrvoje Augustin, Royal Holloway University of London, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Lin, Liu, Cheng and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hsin-Ping Liu, aHBsaXVAbWFpbC5jbXUuZWR1LnR3

Wei-Yong Lin

Wei-Yong Lin Chuan-Hsiu Liu3

Chuan-Hsiu Liu3 Hsin-Ping Liu

Hsin-Ping Liu