- 1Department of International Medicine, Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao, China

- 2Department of Neurology, Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao, China

- 3Department of Physiology and Pathophysiology, School of Basic Medicine, Qingdao University, Qingdao, China

The glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) plays important roles in the regulation of food intake and energy metabolism. Peripheral or central GLP-1 suppresses food intake and reduces body weight. The electrophysiological properties of neurons in the mammalian central nervous system reflect the neuronal excitability and the functional organization of the brain. Recent studies focus on elucidating GLP-1-induced suppression of feeding behaviors and modulation of neuronal electrophysiological properties in several brain regions. Here, we summarize that activation of GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) suppresses food intake and induces postsynaptic depolarization of membrane potential and/or presynaptic modulation of glutamatergic or GABAergic neurotransmission in brain nuclei located within the medulla oblongata, pons, mesencephalon, diencephalon, and telencephalon. This review may provide a background to guide future research about the cellular mechanisms of GLP-1-induced feeding inhibition.

Introduction

The pre-proglucagon (Gcg) gene product peptides include glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), GLP-2, oxyntomodulin (OXM), intervening peptide 1 (IP1), and glicentin. The GLP-1-producing preproglucagon (PPG) neurons located in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) and the intermediate reticular nucleus of the medulla oblongata are the major source of endogenous GLP-1 in the central nervous system, which project widely throughout the central nervous system especially the autonomic control areas (Merchenthaler et al., 1999; Barrera et al., 2011; Llewellyn-Smith et al., 2011; Holt et al., 2019; Muller et al., 2019). Ablation of the PPG neurons in the NTS largely reduces the level of GLP-1 in the hypothalamus, brainstem, and spinal cord (Holt et al., 2019). In addition to the central source, peripheral GLP-1 is released from enteroendocrine L-cells in intestinal mucosa (Eissele et al., 1992) which plays an important role in regulating glucose homeostasis (Edwards et al., 1999; Williams, 2009). Furthermore, a small population of PPG neurons has been identified within the olfactory bulb with only local projection (Thiebaud et al., 2016). Central GLP-1 binds to GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) to exert many important effects including modulation of energy balance, cardiovascular system, learning and memory, rewarding effect of food, and thermogenesis (Trapp and Cork, 2015). GLP-1R belongs to G protein-coupled receptors with predominate Gαs coupling, leading to activation of adenylate cyclase and in turn increased levels of cAMP (Mayo et al., 2003). GLP-1R expressing cells are widely expressed in mouse and non-human primate brain (Cork et al., 2015; Heppner et al., 2015). Recent immunocytochemistry revealed the distribution and subcellular localization of GLP-1R in rat brain (Farkas et al., 2021).

GLP-1 is involved in the regulation of food intake and energy metabolism. Both human clinical trials and animal experiments demonstrated that peripheral or central GLP-1 and GLP-1 analogs suppress food intake and reduce body weight (Turton et al., 1996; Hayes et al., 2008, 2011; Dossat et al., 2011; Heppner and Perez-Tilve, 2015). A recent study revealed that central and peripheral GLP-1 inhibits feeding behaviors through independent gut-brain circuits (Brierley et al., 2021). Activation of GLP-1R in a variety of brain regions, including the hypothalamus (Schick et al., 2003), mesolimbic system (Dossat et al., 2011; Alhadeff et al., 2012; Dickson et al., 2012), and hindbrain (Hayes et al., 2011; Alhadeff et al., 2014), reduces food intake. Drugs targeting GLP-1R have been used as weight loss and anti-diabetic glucose-lowering therapies (Heppner and Perez-Tilve, 2015).

The brain is the most intricate network structure which facilitates a concerted communication between single neurons, different neuronal populations, and remote brain (Gupta et al., 2020). Neurons are the basic structural and functional units in the central nervous system. The electrophysiological properties of neurons such as the spontaneous firing activities and the synaptic neurotransmission in the mammalian central nervous system reflect the neuronal excitability and the functional organization of the brain (Llinás, 1989, 2014). To date, measuring the electrophysiological features of neurons remains one of the most valuable methods to study the functional phenomena of the nervous system. The specific deficits of the electrophysiological properties contribute to some brain diseases (Bernard and Shevell, 2008; Klassen et al., 2011; Tai et al., 2014). Therefore, manipulation of the electrophysiological properties including the spontaneous firing activity of central neurons may play roles in the manifestation of some neurological disorders. For example, the electrophysiological characteristics of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta change before the appearance of motor symptoms in parkinsonian mice (Qi et al., 2017), while excitatory stimulation of dopaminergic neurons may improve the survival of the neurons (Michel et al., 2013). Many studies have demonstrated that GLP-1 suppresses feeding behaviors and modulates the spontaneous firing activities and/or glutamatergic or GABAergic neurotransmission in multiple brain regions. This review highlights the activation of GLP-1R-induced suppression of feeding as well as the modulation of neuronal electrophysiological properties of several brain regions in medulla oblongata, pons, mesencephalon, diencephalon, and telencephalon.

Medulla Oblongata and Pons

The medullar oblongata in rodents and monkeys expresses a high level of GLP-1R (Merchenthaler et al., 1999; Cork et al., 2015; Heppner et al., 2015; Farkas et al., 2021). In human brain tissue of autopsies, GLP-1R is also expressed in the medullar oblongata including the area postrema, the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, and the NTS (Farr et al., 2016). GLP-1 modulates feeding behaviors in the medullar oblongata. Recently, Gaykema et al. (2017) reported that selectively chemogenetic stimulation of caudal medulla pre-proglucagon-producing neurons reduces food intake in both fed and fasted states and suppresses glucose production. Patch-clamp electrophysiological recordings in brain slices further demonstrated that chemogenetic activation selectively depolarizes neuronal membrane potential and increases the firing frequency of labeled medulla pre-proglucagon-producing neurons without affecting unlabeled neurons.

The NTS is the main source of endogenous GLP-1 within the brain (Barrera et al., 2011; Holt et al., 2019). Application of the stable GLP-1R analog exendin-4 into the medial subnucleus of the NTS (mNTS) reduces high-fat diet intake (Alhadeff and Grill, 2014; Table 1). However, electrophysiological studies revealed that GLP-1 or exendin-4 does not change the spontaneous firing activity as well as the synaptic transmission suggesting lack of functional GLP-1R in PPG neurons (Hisadome et al., 2010). Consistent with the electrophysiological results, the morphological study showed a weak/faint expression of GLP-1R in the NTS. It is reported that astrocytes in NTS are components of the GLP-1 signaling system which is involved in food intake control (Reiner et al., 2016). Intracerebroventricular application of GLP-1R agonist binds to GLP-1R on both neurons and astrocytes in the NTS. Activation of GLP-1R induces an increase in intracellular Ca2+ in 40% of NTS astrocytes, while selective inhibition of astrocyte function in NTS abolishes exendin-4-induced inhibition of food intake (Reiner et al., 2016). Therefore, complex mechanisms in both neurons and astrocytes may be involved in GLP-1-induced modulation of food intake in the NTS.

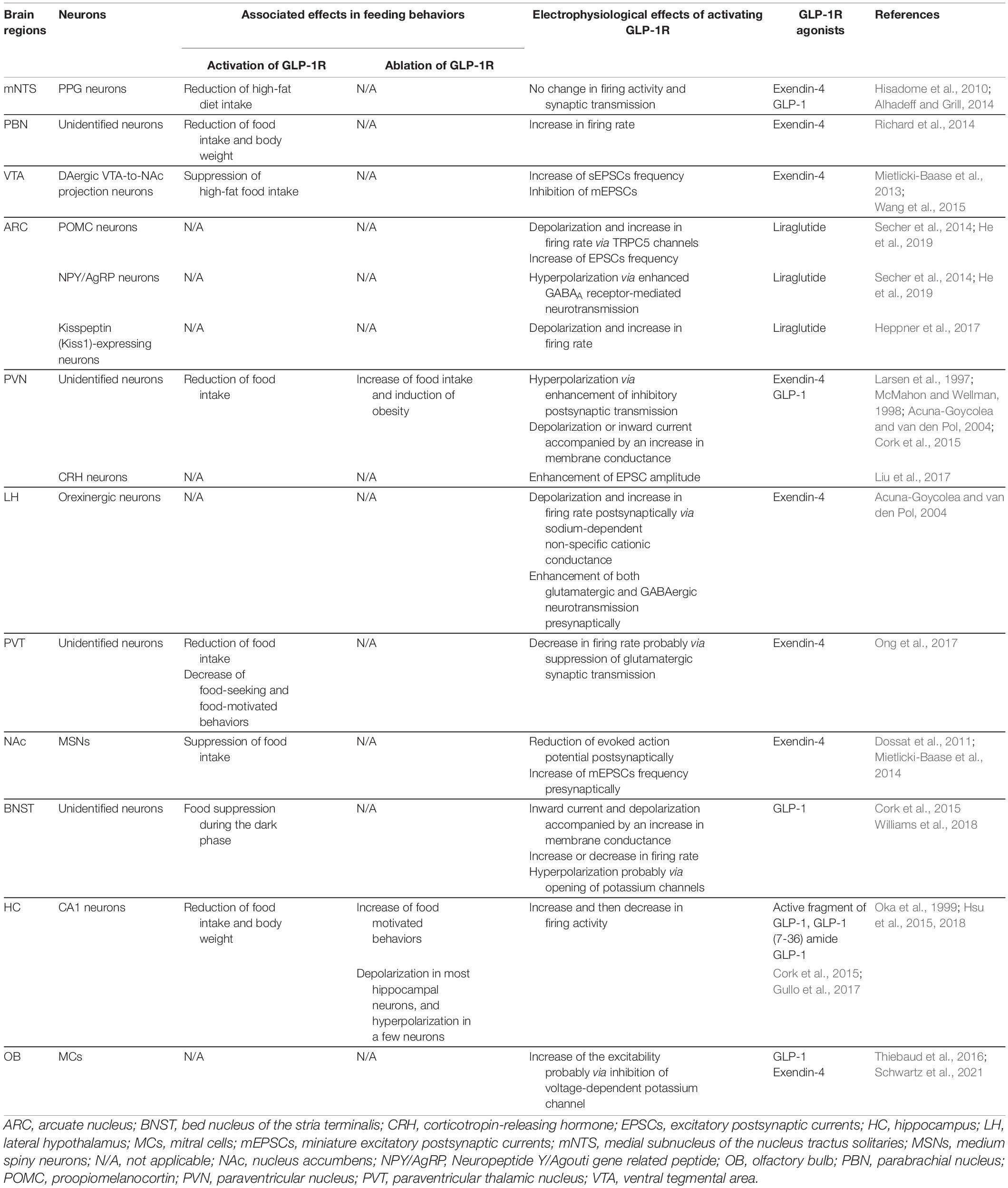

Table 1. Activation of GLP-1R suppresses feeding behaviors and modulates neuronal electrophysiological properties in several brain nuclei.

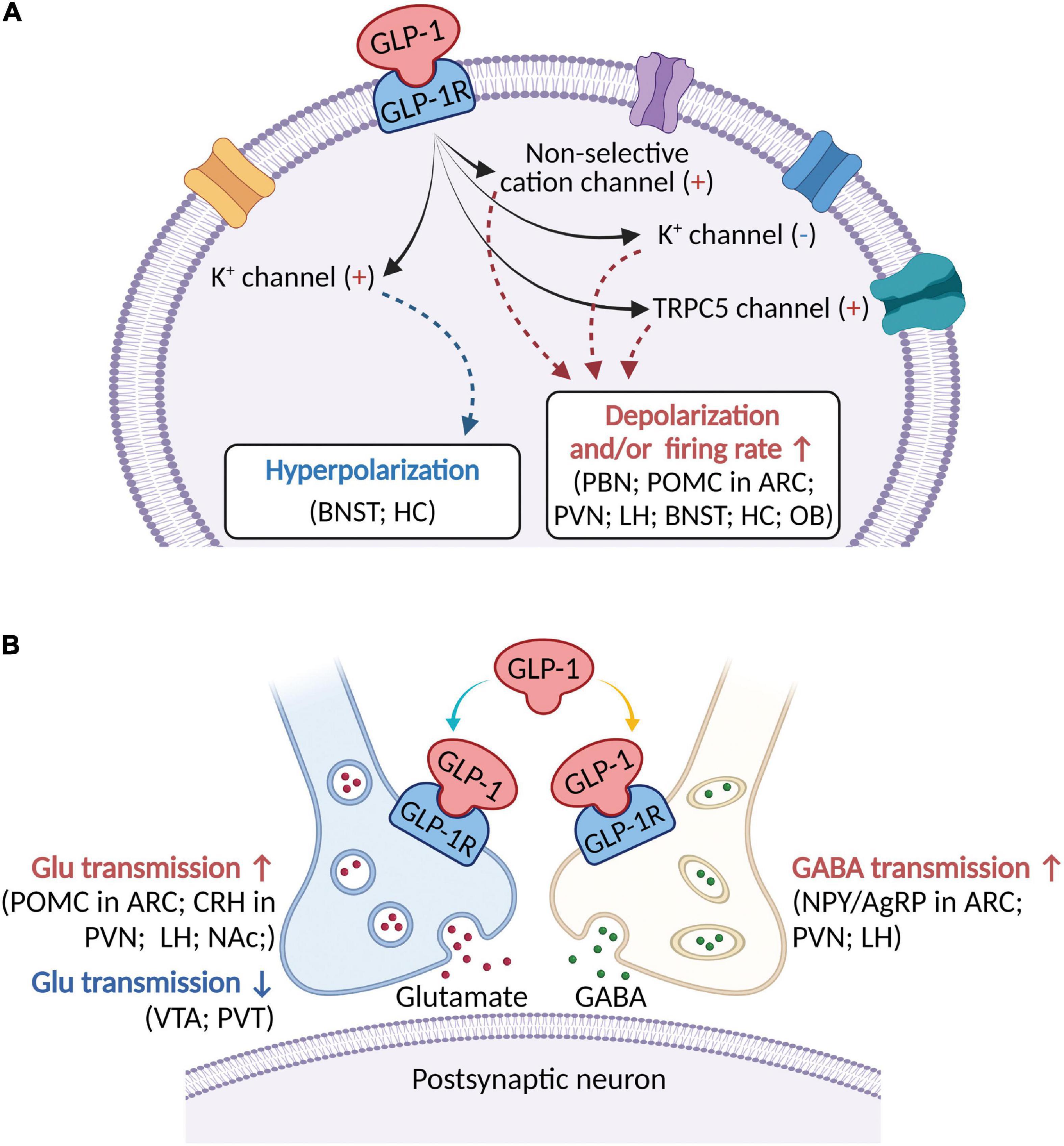

The parabrachial nucleus (PBN) in the pons is associated with the regulation of feeding behaviors. The PBN receives direct GLP-1 projections from NTS neurons (Richard et al., 2014). Stimulation of GLP-1R with exendin-4 in the PBN reduces food intake and therefore decreases body weight in rats. Electrophysiological evidence further revealed that application of exendin-4 results in a remarkable increase in the spontaneous firing rate of the PBN neurons (Richard et al., 2014; Figure 1A). Using the methods of immuno-electron microscopy, Farkas et al. (2021) recently revealed a very widespread distribution of GLP-1R fibers in rat brain suggesting the possible presynaptic effects of GLP-1R in the central nervous system. As the external part of the lateral parabrachial nucleus (LPBN) expresses the highest density of GLP-1R immunoreactive fibers (Farkas et al., 2021), further electrophysiological studies are needed to study the possible presynaptic modulation of the electrophysiological activities of the PBN neurons.

Figure 1. A schematic diagram describing the major electrophysiological effects of activating GLP-1R in brain areas involved in modulation of feeding behaviors. (A) GLP-1 (including its agonists) binds to postsynaptic GLP-1R to depolarize membrane potential and/or increase firing rate in most brain regions, but hyperpolarize membrane potential in a few brain areas. Several ionic mechanisms, including non-selective cation channel, K+ channel, and TRPC5 channel, may be involved in activation of GLP-1R-induced depolarization or hyperpolarization. (B) In addition to postsynaptic receptors, GLP-1 acts on presynaptic GLP-1R to modulate both glutamatergic and GABAergic neurotransmission. ARC, arcuate nucleus; BNST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; Glu, glutamate; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; HC, hippocampus; LH, lateral hypothalamus; NAc, nucleus accumbens; NPY/AgRP, Neuropeptide Y/Agouti gene-related peptide; OB, olfactory bulb; PBN, parabrachial nucleus; POMC, proopiomelanocortin; PVN, paraventricular nucleus; PVT, paraventricular thalamic nucleus; VTA, ventral tegmental area.

Mesencephalon

The ventral tegmental area (VTA) is a possible brain region for GLP-1-induced suppression of food intake. Functional study revealed that application of GLP-1R antagonist into the VTA attenuates peripheral application of exendin-4-induced anorectic effects (Mietlicki-Baase et al., 2013). Electrophysiological recordings revealed that exendin-4 increases the frequency of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) of VTA dopaminergic neurons suggesting the possible presynaptic modulation of GLP-1R on glutamatergic terminals. Behavioral study also demonstrated that modulating AMPA/kainite, but not NMDA, receptor-mediated glutamatergic neurotransmission within VTA is involved in GLP-1-induced intake-suppressive effects (Mietlicki-Baase et al., 2013). In addition, intra-VTA application of exendin-4 suppresses high-fat food intake, which is consistent with the results of chemogenetic activation of endogenously released GLP-1 nerve terminals in the VTA (Wang et al., 2015). In contrast to the enhancement of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic transmission (Mietlicki-Baase et al., 2013), using retrograde labeling of VTA to nucleus accumbens (NAc) medial shell projecting neurons, in vitro patch-clamp recordings showed that exendin-4 selectively inhibits the miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) within the dopaminergic VTA-to-NAc projection neurons (Wang et al., 2015; Figure 1B) suggesting the presynaptic inhibition of glutamatergic neurotransmission. As NAc is also an important brain region associated with GLP-1-induced feeding suppression, further electrophysiological studies are necessary to explore the contribution of glutamatergic neurotransmission to endogenously released GLP-1-induced suppression of high-fat food intake in the VTA.

Diencephalon

The arcuate nucleus (ARC) of the hypothalamus plays a particularly important role in the central regulation of food intake (Bouret et al., 2004). Two distinct types of neurons within the ARC, proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and Neuropeptide Y (NPY)/Agouti gene-related peptide (AgRP) neurons, play important roles in energy balance and glucose homeostasis (Gautron et al., 2015; Caron et al., 2018). Activation of both the NPY/AgRP neurons and POMC neurons coordinates the activity of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), promoting stimulation or inhibition of feeding, respectively. It is well known that the anti-diabetic drug, long-acting GLP-1R agonist, liraglutide reduces body weight. The highest level of GLP-1R expressing cells, detected by transgene expression (Cork et al., 2015), in situ hybridization (Merchenthaler et al., 1999; Heppner et al., 2015), and immunocytochemistry (Farkas et al., 2021), is present in the ARC. In vitro patch-clamp electrophysiological recordings revealed that modulating the electrophysiological properties of both POMC and cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) neurons (POMC/CART neurons) and NPY/AgRP neurons are the possible mechanism of liraglutide-induced weight loss (Secher et al., 2014). Peripheral application of fluorescently labeled liraglutide binds GLP-1R within the ARC (Secher et al., 2014). Liraglutide depolarizes membrane potential and increases the spontaneous action potentials directly through postsynaptic GLP-1R in the ARC neurons expressing POMC (Secher et al., 2014; He et al., 2019). In peripheral pancreatic β cells, GLP-1 depolarizes membrane potential through activation of Na+-permeable TRPM4 and TRPM5 channels (Shigeto et al., 2015). Similarly, TRPC5 channels are involved in liraglutide-induced postsynaptic excitation of arcuate neurons (He et al., 2019). In addition to perikarya and dendrites expression, high level of GLP-1R was also observed in axons of ARC neurons (Farkas et al., 2021). Consistently, electrophysiological recordings showed that liraglutide increases the EPSCs frequency of POMC neurons suggesting the modulation of presynaptic excitatory synaptic transmission (He et al., 2019).

GABA released by the NPY/AgRP neurons is very important to the control of food intake probably via inhibiting the anorectic effects of the POMC neurons. Further electrophysiological study showed that, opposite to the effects on arcuate POMC neurons, GLP-1 hyperpolarizes arcuate NPY neurons indirectly via increased GABAA receptor-mediated neurotransmission of local GABAergic interneurons (Secher et al., 2014; He et al., 2019). The Kisspeptin (Kiss1)-expressing neurons located in the ARC are responsible for gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)/luteinizing hormone (LH) release (Li et al., 2009; Han et al., 2015). The Kiss1 neurons may be a key integrator of metabolic status with GnRH/LH release. Liraglutide increases the action potential firing and causes a direct membrane depolarization of ARC Kiss1 cells in brain slices (Heppner et al., 2017).

Morphological studies demonstrated a particularly high density of GLP-1R expression in the PVN of mice (Cork et al., 2015), rats (Merchenthaler et al., 1999; Farkas et al., 2021), and primates (Heppner et al., 2015). Early study showed that exendin-4 induces diverse responses including depolarization, hyperpolarization, and no response in paraventricular hypothalamic neurons. The GLP-1-induced hyperpolarization of PVN neurons may be induced by an enhancement of inhibitory postsynaptic transmission (Acuna-Goycolea and van den Pol, 2004). Consistent with exendin-4-induced depolarization, Cork et al. (2015) also revealed that bath application of GLP-1 induces an inward current which is accompanied by an increase in membrane conductance. Activation of GLP-1R with exendin-4 enhances the amplitude but not the frequency of AMPA receptor-mediated EPSCs in PVN corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) neurons and thus promotes the excitability of CRH neurons postsynaptically (Liu et al., 2017). Functional studies revealed that activation of GLP-1R in the PVN reduces food intake (Larsen et al., 1997; McMahon and Wellman, 1998). Consistently, postnatal depletion of GLP-1R in the PVN increases food intake and induces obesity (Liu et al., 2017).

Different neural circuits have been proposed to maintain energy homeostasis. Both central GLP-1 and orexin pathways play an important role in neural integration of satiation and food reward. GLP-1 projections from NTS to NAc and VTA promote satiation and reduce food reward, while orexinergic projection from lateral hypothalamus to NTS suppresses satiation and increases food reward (Dossat et al., 2011). Early study revealed a direct modulation of GLP-1R on the electrophysiological activities of orexinergic neurons in the lateral hypothalamus. Application of exendin-4 depolarizes the membrane potential and increases the spontaneous discharge rate of orexinergic neurons in the lateral hypothalamus (Acuna-Goycolea and van den Pol, 2004). The GLP-1-induced excitation of orexinergic neurons is a directly postsynaptic effect that may be mediated by sodium-dependent non-specific cationic conductances. In addition, activation of GLP-1R enhances both glutamatergic and GABAergic neurotransmission presynaptically in orexinergic neurons. However, exendin-4 does not change the membrane potential as well as the firing rate of melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH) neurons in the lateral hypothalamus (Acuna-Goycolea and van den Pol, 2004). The GLP-1R activation-induced both postsynaptic and presynaptic modulation of orexinergic neurons may suggest some complex integration of satiation and food reward.

The paraventricular thalamic nucleus (PVT) neurons receive GLP-1 innervation from NTS and express GLP-1R (Cork et al., 2015; Farkas et al., 2021). PVT is involved in energy balance and reward control. Behavioral tests showed that intra-PVT application of exendin-4 reduces food intake and decreases food-seeking and food-motivated behaviors (Ong et al., 2017). Further electrophysiological recordings revealed that exendin-4 inhibits the spontaneous action potential firing in PVN neurons projecting to NAc core. Suppression of glutamatergic synaptic transmission may be associated with the reduced excitability of GLP-1R activation (Ong et al., 2017).

Telencephalon

Moderate density of GLP-1R is expressed in both the cell bodies and fibers of the NAc shell and core (Cork et al., 2015; Heppner et al., 2015; Farkas et al., 2021). Activation of GLP-1R in NAc core induces suppression of food intake (Dossat et al., 2011; Mietlicki-Baase et al., 2014). Current-clamp recordings illustrated that exendin-4 induces a small reduction in evoked action potential from medium spiny neurons (MSNs) suggesting slightly postsynaptic effects. In addition to perikarya expression, GLP-1R is also expressed on the processes of NAc (Farkas et al., 2021) suggesting some possibly presynaptic modulation of the NAc activity. Indeed, further electrophysiological studies demonstrated that exendin-4 predominantly activates presynaptic GLP-1R in NAc to increase the frequency of AMPA/kainate receptor-mediated mEPSCs. Therefore, the enhancement of glutamatergic AMPA/Kainate signaling is probably involved in GLP-1-induced inhibition of food intake (Mietlicki-Baase et al., 2014). In addition to modulating food intake, recent publication revealed that NAc is also a possible molecular target for GLP-1-induced addiction behaviors (Hernandez and Schmidt, 2019; Hernandez et al., 2019). Intra-NAc application of exendin-4 increases the spontaneous firing rate of MSNs in cocaine-experienced rats and reduces cocaine-seeking behavior in rats (Hernandez et al., 2019).

Morphological studies revealed that the neurons in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) express a high level of GLP-1R (Cork et al., 2015; Heppner et al., 2015; Farkas et al., 2021). Application of GLP-1 elicits an inward current and depolarization accompanied by an increase in membrane conductance (Cork et al., 2015). Recently, under the model of cell-attached patch-clamp recordings, Williams et al. (2018) reported that GLP-1 induces either an increase or a decrease of spontaneous firing rate in GLP-1R expressing BNST neurons. Further whole-cell patch-clamp recordings revealed that GLP-1 induces either a depolarizing or hyperpolarizing response, while dopamine evokes response in a reciprocal fashion to that of GLP-1. The GLP-1-induced hyperpolarization is accompanied by an increase in membrane conductance suggesting the opening of potassium channels (Williams et al., 2018). In addition, functional study demonstrated that local injection of GLP-1 into the BNST induces food suppression during the dark phase (Williams et al., 2018).

Inconsistent distribution patterns of GLP-1R in the hippocampus have been reported by different morphological studies (Cork et al., 2015; Jensen et al., 2018; Farkas et al., 2021). For example, a relatively high level of GLP-1R-immunoreactivity was observed in mouse hippocampus (Jensen et al., 2018) while a low level of GLP-1R-immunoreactivity was revealed in rat hippocampus (Farkas et al., 2021), which may suggest some species difference of the GLP-1R expression in the hippocampus. However, functional studies did detect the effects of GLP-1R in the hippocampus. Early in vivo electrophysiological recordings showed that juxtacellular application of the active fragment of GLP-1, GLP-1 (7–36) amide induces an increase and then a decrease of firing activity in the hippocampal CA1 neurons. Modulation of non-NMDA glutamate receptor-mediated synaptic transmission is involved in GLP-1-induced effects (Oka et al., 1999). Bath application of GLP-1 induces a depolarization in most hippocampal neurons and a hyperpolarization in a few neurons (Cork et al., 2015). In addition, in vitro electrophysiological recordings further demonstrated that exendin-4 elicits an early fast excitatory response dose-dependently (Gullo et al., 2017). Consistent with the electrophysiological recordings, behavioral studies showed that activation of GLP-1R in the ventral hippocampal CA1 regions reduces food intake and body weight, while targeted ventral CA1 GLP-1R knockdown increases food-motivated behaviors (Hsu et al., 2015, 2018). In addition to modulating feeding behaviors, GLP-1 promotes the proliferation of progenitor cells and increases immature neurons in the hippocampus and in turn reverses memory impairment (Lennox et al., 2014). Activation of GLP-1R with liraglutide improves cognition decline of db/db mice via increasing neuronal survival in the CA1, CA3, and DG regions of hippocampus (Zhang et al., 2021).

The olfactory bulb is the basic brain region responsible for olfactory information. The deep short axon cells (dSACs) in the granule cell layer (GCL) of olfactory bulb, named PPG neurons, could synthesize and release GLP-1 and in turn modulate the activity of the first-order neurons, mitral cells (MCs) which are the primary projection neurons of the olfactory bulb (Thiebaud et al., 2016). Positive expression of GLP-1R is detected in the GCL of olfactory bulb (Cork et al., 2015). Patch-clamp recordings revealed that bath application of GLP-1 or exendin-4 increases the spontaneous firing frequency and decreases the excitation threshold for MC firing in olfactory bulb. Decreasing the conductance of voltage-dependent potassium channels, Kv1.3, is the possible ionic mechanism of GLP-1-induced enhancement of MC excitability (Thiebaud et al., 2016). Recently, further studies revealed that optogenetic activation of PPG neurons in the GCL generates biphasic inhibition-excitation response in MCs. However, a single pulse light stimulation of PPG neurons produces only glutamatergic EPSCs, but not IPSCs, in granule cells. The stimulation of PPG neurons-induced glutamatergic EPSCs is much faster than that of GABAergic IPSCs in MCs. Under the condition of blocking GABAergic neurotransmission, light stimulation of PPG neurons results in an increase in the excitation of MCs suggesting the involvement of PPG neurons in shaping the MC firing patterns (Thiebaud et al., 2019). It is known that, in addition to olfactory physiology, MC activity is also associated with feeding and nutritional status (Fadool et al., 2011; Aimé et al., 2014; Thiebaud et al., 2014; Riera et al., 2017). The olfactory acuity is regulated by the metabolic state and therefore the olfactory system is a driver of feeding behavior. Enhancement of neuronal excitability of the major output neurons of the olfactory bulb via blocking voltage-dependent potassium channel reduces body weight in obese mice (Schwartz et al., 2021). Previous study suggested that chronic administration of fat in the diet impairs the spontaneous firing rate of MCs (Fadool et al., 2011), and reduces the amplitude of electro-olfactogram (EOG). Furthermore, the volume of olfactory bulb is significantly smaller in individuals with obesity and negatively correlated with body mass index (BMI) (Poessel et al., 2020). Therefore, the GLP-1-induced excitation of MCs, probably via inhibition of voltage-dependent potassium channel conductance and enhancement of glutamatergic neurotransmission, could lead to changed excitability of higher olfactory cortical as well as hypothalamic regions to change metabolic states.

Conclusion

Being a peptide involved in the regulation of food intake and energy metabolism, GLP-1 has been demonstrated to suppress food intake and reduce body weight. In this review, we provide a description of recent advances of GLP-1-induced inhibition of feeding behaviors and modulation of neuronal electrophysiological activities in multiple brain nuclei located within the medulla oblongata, pons, mesencephalon, diencephalon, and telencephalon (Table 1). Activation of GLP-1R suppresses food intake and induces postsynaptic depolarization of membrane potential (Figure 1A) and/or presynaptic modulation of glutamatergic or GABAergic neurotransmission (Figure 1B). Several ionic mechanisms such as non-selective cation channel, voltage-dependent potassium channel, and TRPC5 channel may be associated with activation of GLP-1R-induced electrophysiological effects (Figure 1A). This review may provide a rationale about the cellular mechanisms of GLP-1-induced suppression of feeding behaviors.

Author Contributions

X-YC wrote the original draft. LC revised the manuscript. WY and A-MX contributed to the conception, design, and revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81971192, 81571225, and 31671076).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acuna-Goycolea, C., and van den Pol, A. (2004). Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Excites Hypocretin/Orexin Neurons by Direct and Indirect Mechanisms: Implications for Viscera-Mediated Arousal. J. Neurosci. 24, 8141–8152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1607-04.2004

Aimé, P., Palouzier-Paulignan, B., Salem, R., Koborssy, D. A., Garcia, S., Duchamp, C., et al. (2014). Romestaing C, Julliard AK. Modulation of olfactory sensitivity and glucose-sensing by the feeding state in obese Zucker rats. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 8:326. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00326

Alhadeff, A. L., Baird, J. P., Swick, J. C., Hayes, M. R., and Grill, H. J. (2014). Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor signaling in the lateral parabrachial nucleus contributes to the control of food intake and motivation to feed. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 2233–2243. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.74

Alhadeff, A. L., and Grill, H. J. (2014). Hindbrain nucleus tractus solitarius glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor signaling reduces appetitive and motivational aspects of feeding. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 307, R465–R470. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00179.2014

Alhadeff, A. L., Rupprecht, L. E., and Hayes, M. R. (2012). GLP-1 neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract project directly to the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens to control for food intake. Endocrinology 153, 647–658. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1443

Barrera, J. G., Jones, K. R., Herman, J. P., D’Alessio, D. A., Woods, S. C., and Seeley, R. J. (2011). Hyperphagia and increased fat accumulation in two models of chronic CNS glucagon-like peptide-1 loss of function. J. Neurosci. 31, 3904–3913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2212-10.2011

Bernard, G., and Shevell, M. I (2008). Channelopathies: A Review. Pediatr. Neurol. 38, 73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.09.007

Bouret, S. G., Draper, S. J., and Simerly, R. B. (2004). Formation of Projection Pathways from the Arcuate Nucleus of the Hypothalamus to Hypothalamic Regions Implicated in the Neural Control of Feeding Behavior in Mice. J. Neurosci. 24, 2797–2805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5369-03.2004

Brierley, D. I., Holt, M. K., Singh, A., de Araujo, A., McDougle, M., Vergara, M., et al. (2021). Central and peripheral GLP-1 systems independently suppress eating. Nat. Metab. 3, 258–273. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00344-4

Caron, A., Dungan, L. H. M., Castorena, C. M., Fujikawa, T., Lee, S., Lord, C. C., et al. (2018). POMC neurons expressing leptin receptors coordinate metabolic responses to fasting via suppression of leptin levels. eLife 7:e33710. doi: 10.7554/eLife.33710

Cork, S. C., Richards, J. E., Holt, M. K., Gribble, F. M., Reimann, F., and Trapp, S. (2015). Distribution and characterisation of Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor expressing cells in the mouse brain. Mol. Metab. 4, 718–731. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.07.008

Dickson, S. L., Shirazi, R. H., Hansson, C., Bergquist, F., Nissbrandt, H., and Skibicka, K. P. (2012). The glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) analogue, exendin-4, decreases the rewarding value of food: a new role for mesolimbic GLP-1 receptors. J. Neurosci. 32, 4812–4820. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6326-11.2012

Dossat, A. M., Lilly, N., Kay, K., and Williams, D. L. (2011). Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptors in Nucleus Accumbens Affect Food Intake. J. Neurosci. 31, 14453–14457. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3262-11.2011

Edwards, C. M., Todd, J. F., Mahmoudi, M., Wang, Z., Wang, R. M., Ghatei, M. A., et al. (1999). Glucagon-like peptide 1 has a physiological role in the control of postprandial glucose in humans: studies with the antagonist exendin 9-39. Diabetes 48, 86–93. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.1.86

Eissele, R., Göke, R., Willemer, S., Harthus, H. P., Vermeer, H., Arnold, R., et al. (1992). Glucagon-like peptide-1 cells in the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas of rat, pig and man. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 22, 283–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1992.tb01464.x

Fadool, D. A., Tucker, K., and Pedarzani, P. (2011). Mitral Cells of the Olfactory Bulb Perform Metabolic Sensing and Are Disrupted by Obesity at the Level of the Kv1.3 Ion Channel. PLoS One 6:e24921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024921

Farkas, E., Szilvásy-Szabó, A., Ruska, Y., Sinkó, R., Rasch, M. G., Egebjerg, T., et al. (2021). Distribution and ultrastructural localization of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) in the rat brain. Brain Struct. Funct. 226, 225–245. doi: 10.1007/s00429-020-02189-1

Farr, O. M., Sofopoulos, M., Tsoukas, M. A., Dincer, F., Thakkar, B., Sahin-Efe, A., et al. (2016). GLP-1 receptors exist in the parietal cortex, hypothalamus and medulla of human brains and the GLP-1 analogue liraglutide alters brain activity related to highly desirable food cues in individuals with diabetes: a crossover, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetologia 59, 954–965. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-3874-y

Gautron, L., Elmquist, J. K., and Williams, K. W. (2015). Neural control of energy balance: translating circuits to therapies. Cell 161, 133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.023

Gaykema, R. P., Newmyer, B. A., Ottolini, M., Raje, V., Warthen, D. M., Lambeth, P. S., et al. (2017). Activation of murine pre-proglucagon–producing neurons reduces food intake and body weight. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 1031–1045. doi: 10.1172/JCI8133

Gullo, F., Ceriani, M., D’Aloia, A., Wanke, E., Constanti, A., Costa, B., et al. (2017). Plant Polyphenols and Exendin-4 Prevent Hyperactivity and TNF-α Release in LPS-Treated In vitro Neuron/Astrocyte/Microglial Networks. Front. Neurosci. 11:500. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00500

Gupta, P., Balasubramaniam, N., Chang, H. Y., Tseng, F. G., and Santra, T. S. (2020). A Single-Neuron: Current Trends and Future Prospects. Cells 9:1528. doi: 10.3390/cells9061528

Han, S. Y., McLennan, T., Czieselsky, K., and Herbison, A. E. (2015). Selective optogenetic activation of arcuate kisspeptin neurons generates pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 112, 13109–13114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512243112

Hayes, M. R., Leichner, T. M., Zhao, S., Lee, G. S., Chowansky, A., Zimmer, D., et al. (2011). Intracellular signals mediating the food intake-suppressive effects of hindbrain glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor activation. Cell Metab. 13, 320–330. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.02.010

Hayes, M. R., Skibicka, K. P., and Grill, H. J. (2008). Caudal brainstem processing is sufficient for behavioral, sympathetic, and parasympathetic responses driven by peripheral and hindbrain glucagon-like-peptide-1 receptor stimulation. Endocrinology 149, 4059–4068. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1743

He, Z., Gao, Y., Lieu, L., Afrin, S., Cao, J., Michael, N. J., et al. (2019). Direct and indirect effects of liraglutide on hypothalamic POMC and NPY/AgRP neurons – Implications for energy balance and glucose control. Mol. Metab. 28, 120–134. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2019.07.008

Heppner, K. M., Baquero, A. F., Bennett, C. M., Lindsley, S. R., Kirigiti, M. A., Bennett, B., et al. (2017). GLP-1R Signaling Directly Activates Arcuate Nucleus Kisspeptin Action in Brain Slices but Does not Rescue Luteinizing Hormone Inhibition in Ovariectomized Mice During Negative Energy Balance. eNeuro 4, e198–e116. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0198-16.2016

Heppner, K. M., Kirigiti, M., Secher, A., Paulsen, S. J., Buckingham, R., Pyke, C., et al. (2015). Expression and distribution of glucagon-like peptide1 receptor mRNA, protein and binding in the male nonhuman primate (Macaca mulatta) brain. Endocrinology 156, 255–267. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1675

Heppner, K. M., and Perez-Tilve, D. (2015). GLP-1 based therapeutics: simultaneously combating T2DM and obesity. Front. Neurosci. 9:92. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00092

Hernandez, N. S., O’Donovan, B., Ortinski, P. I., and Schmidt, H. D. (2019). Activation of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors in the nucleus accumbens attenuates cocaine seeking in rats. Addict. Biol. 24, 170–181. doi: 10.1111/adb.12583

Hernandez, N. S., and Schmidt, H. D. (2019). Central GLP-1 Receptors: Novel Molecular Targets for Cocaine Use Disorder. Physiol. Behav. 206, 93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.03.026

Hisadome, K., Reimann, F., Gribble, F. M., and Trapp, S. (2010). Leptin Directly Depolarizes Preproglucagon Neurons in the Nucleus Tractus Solitarius: Electrical Properties of Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Neurons. Diabetes 59, 1890–1898. doi: 10.2337/db10-0128

Holt, M. K., Richards, J. E., Cook, D. R., Brierley, D. I., Williams, D. L., Reimann, F., et al. (2019). Preproglucagon Neurons in the Nucleus of the Solitary Tract Are the Main Source of Brain GLP-1, Mediate Stress-Induced Hypophagia, and Limit Unusually Large Intakes of Food. Diabetes 68, 21–33. doi: 10.2337/db18-0729

Hsu, T. M., Hahn, J. D., Konanur, V. R., Lam, A., and Kanoski, S. E. (2015). Hippocampal GLP-1 receptors influence food intake, meal size, and effort-based responding for food through volume transmission. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 327–337. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.175

Hsu, T. M., Noble, E. E., Liu, C. M., Cortella, A. M., Konanur, V. R., Suarez, A. N., et al. (2018). A hippocampus to prefrontal cortex neural pathway inhibits food motivation through glucagon-like peptide-1 signaling. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 1555–1565. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.91

Jensen, C. B., Pyke, C., Rasch, M. G., Dahl, A. B., Knudsen, L. B., and Secher, A. (2018). Characterization of the glucagonlike peptide-1 receptor in male mouse brain using a novel antibody and in situ hybridization. Endocrinology 159, 665–675. doi: 10.1210/en.2017-00812

Klassen, T., Davis, C., Goldman, A., Burgess, D., Chen, T., Wheeler, D., et al. (2011). Exome sequencing of ion channel genes reveals complex profiles confounding personal risk assessment in epilepsy. Cell 145, 1036–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.025

Larsen, P. J., Tang-Christensen, M., and Jessop, D. S. (1997). Central administration of glucagon-like peptide-1 activates hypothalamic neuroendocrine neurons in the rat. Endocrinology 138, 4445–4455. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5270

Lennox, R., Flatt, P. R., and Gault, V. A. (2014). Lixisenatide improves recognition memory and exerts neuroprotective actions in high-fat fed mice. Peptides 61, 38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.08.014

Li, X. F., Kinsey-Jones, J. S., Cheng, Y., Knox, A. M., Lin, Y., Petrou, N. A., et al. (2009). Kisspeptin signalling in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus regulates GnRH pulse generator frequency in the rat. PLoS One 4:e8334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008334

Liu, J., Conde, K., Zhang, P., Lilascharoen, V., Xu, Z., Lim, B. K., et al. (2017). Enhanced AMPA receptor trafficking mediates the anorexigenic effect of endogenous glucagon like peptide-1 in the paraventricular hypothalamus. Neuron 96, 897–909. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.09.042

Llewellyn-Smith, I. J., Reimann, F., Gribble, F. M., and Trapp, S. (2011). Preproglucagon neurons project widely to autonomic control areas in the mouse brain. Neuroscience 180, 111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.02.023

Llinás, R. R. (1989). The intrinsic electrophysiological properties of mammalian neurons: insights into central nervous system function. Science 242, 1654–1664. doi: 10.1126/science.3059497

Llinás, R. R. (2014). Intrinsic electrical properties of mammalian neurons and CNS function: a historical perspective. Front. Cell Neurosci. 8:320. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00320

Mayo, K. E., Miller, L. J., Bataille, D., Dalle, S., Goke, B., Thorens, B., et al. (2003). International Union of Pharmacology. XXXV. The glucagon receptor family. Pharm. Rev. 55, 167–194. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.1.6

McMahon, L. R., and Wellman, P. J. (1998). PVN infusion of GLP-1-(7-36) amide suppresses feeding but does not induce aversion or alter locomotion in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 274, R23–R29. gu.1998.274.1.r23 doi: 10.1152/ajpre

Merchenthaler, I., Lane, M., and Shughrue, P. (1999). Distribution of pre-pro-glucagon and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor messenger RNAs in the rat central nervous system. J. Comp. Neurol. 403, 261–280. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19990111)403:23.0.CO

Michel, P. P., Toulorge, D., Guerreiro, S., and Hirsch, E. C. (2013). Specific needs of dopamine neurons for stimulation in order to survive: implication for Parkinson disease. FASEB. J. 27, 3414–3423. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-220418

Mietlicki-Baase, E. G., Ortinski, P. I., Reiner, D. J., Sinon, C. G., McCutcheon, J. E., Pierce, R. C., et al. (2014). Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor activation in the nucleus accumbens core suppresses feeding by increasing glutamatergic AMPA/kainate signaling. J. Neurosci. 34, 6985–6992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0115-14.2014

Mietlicki-Baase, E. G., Ortinski, P. I., Rupprecht, L. E., Olivos, D. R., Alhadeff, A. L., Pierce, R. C., et al. (2013). The food intake-suppressive effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor signaling in the ventral tegmental area are mediated by AMPA/kainate receptors. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 305, E1367–E1374. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00413.2013

Muller, T. D., Finan, B., Bloom, S. R., D’Alessio, D., Drucker, D. J., Flatt, P. R., et al. (2019). Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Mol. Metab. 30, 72–130. t.2019.09.010 doi: 10.1016/j.molme

Oka, J. I., Goto, N., and Kameyama, T. (1999). Glucagon-like peptide-1 modulates neuronal activity in the rat’s hippocampus. Neuroreport 10, 1643–1646. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199906030-00004

Ong, Z. Y., Liu, J. J., Pang, Z. P., and Grill, H. J. (2017). Paraventricular Thalamic Control of Food Intake and Reward: Role of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Signaling. Neuropsychopharmacology 42, 2387–2397. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.150

Poessel, M., Breuer, N., Joshi, A., Pampel, A., Villringer, A., Hummel, T., et al. (2020). Reduced Olfactory Bulb Volume in Obesity and Its Relation to Metabolic Health Status. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 14:586998. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2020.586998

Qi, C., Varga, S., Oh, S. J., Lee, C. J., and Lee, D. (2017). Optogenetic rescue of locomotor dysfunction and dopaminergic degeneration caused by alpha-synuclein and EKO genes. Exp. Neurobiol. 26, 97–103. doi: 10.5607/en.2017.26.2.97

Reiner, D. J., Mietlicki-Baase, E. G., McGrath, L. E., Zimmer, D. J., Bence, K. K., Sousa, G. L., et al. (2016). Astrocytes regulate GLP-1 receptor-mediated effects on energy balance. J. Neurosci. 36, 3531–3540. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3579-15.2016

Richard, J. E., Farkas, I., Anesten, F., Anderberg, R. H., Dickson, S. L., Gribble, F. M., et al. (2014). GLP-1 Receptor Stimulation of the Lateral Parabrachial Nucleus Reduces Food Intake: Neuroanatomical, Electrophysiological, and Behavioral Evidence. Endocrinology 155, 4356–4367. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1248

Riera, C. E., Tsaousidou, E., Halloran, J., Follett, P., Hahn, O., Pereira, M. M. A., et al. (2017). The sense of smell impacts metabolic health and obesity. Cell Metab. 26, 198–211. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.06.015

Schick, R. R., Zimmermann, J. P., vorm Walde, T., and Schusdziarra, V. (2003). Peptides that regulate food intake: glucagon-like peptide 1-(7-36) amide acts at lateral and medial hypothalamic sites to suppress feeding in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 284, R1427–R1435. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00479.2002

Schwartz, A. B., Kapur, A., Huang, Z., Anangi, R., Spear, J. M., Stagg, S., et al. (2021). Olfactory bulb targeted QD bioconjugate and Kv1.3 blocking peptide improve metabolic health in obese male mice. J. Neurochem. 157, 1876–1896. doi: 10.1111/jnc.15200

Secher, A., Jelsing, J., Baquero, A. F., Hecksher-Sørensen, J., Cowley, M. A., Dalbøge, L. S., et al. (2014). The arcuate nucleus mediates GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide-dependent weight loss. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 4473–4488. doi: 10.1172/JCI75276

Shigeto, M., Ramracheya, R., Tarasov, A. I., Cha, C. Y., Chibalina, M. V., Hastoy, B., et al. (2015). GLP-1 stimulates insulin secretion by PKC-dependent TRPM4 and TRPM5 activation. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 4714–4728. doi: 10.1172/JCI81975

Tai, C., Abe, Y., Westenbroek, R. E., Scheuer, T., and Catterall, W. A. (2014). Impaired excitability of somatostatin- and parvalbumin-expressing cortical interneurons in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 111, E3139–E3148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411131111

Thiebaud, N., Gribble, F., Reimann, F., Trapp, S., and Fadool, D. A. (2019). A unique olfactory bulb microcircuit driven by neurons expressing the precursor to glucagon-like peptide 1. Sci. Rep. 9:15542. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51880-9

Thiebaud, N., Johnson, M. C., Butler, J. L., Bell, G. A., Ferguson, K. L., Fadool, A. R., et al. (2014). Hyperlipidemic diet causes loss of olfactory sensory neurons, reduces olfactory discrimination, and disrupts odor-reversal learning. J. Neurosci. 34, 6970–6984. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3366-13.2014

Thiebaud, N., Llewellyn-Smith, I. J., Gribble, F., Reimann, F., Trapp, S., and Fadool, D. A. (2016). The incretin hormone glucagon−like peptide 1 increases mitral cell excitability by decreasing conductance of a voltage−dependent potassium channel. J. Physiol. 594, 2607–2628. doi: 10.1113/JP272322

Trapp, S., and Cork, S. C. (2015). PPG neurons of the lower brain stem and their role in brain GLP-1 receptor activation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 309, R795–R804. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00333.2015

Turton, M. D., O’Shea, D., Gunn, I., Beak, S. A., Edwards, C. M., Meeran, K., et al. (1996). A role for glucagon-like peptide-1 in the central regulation of feeding. Nature 379, 69–72. doi: 10.1038/379069a0

Wang, X. F., Liu, J. J., Xia, J., Liu, J., Mirabella, V., and Pang, Z. P. (2015). Endogenous Glucagon-like peptide-1 suppresses high-fat food intake by reducing synaptic drive onto mesolimbic dopamine neurons. Cell Rep. 12, 726–733. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.062

Williams, D. L. (2009). Minireview: finding the sweet spot: peripheral versus central glucagon-like peptide 1 action in feeding and glucose homeostasis. Endocrinology 150, 2997–3001. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0220

Williams, D. L., Lilly, N. A., Edwards, I. J., Yao, P., Richards, J. E., and Trapp, S. (2018). GLP-1 action in the mouse bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Neuropharmacology 131, 83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.12.007

Keywords: GLP-1, electrophysiological property, feeding behavior, spontaneous firing activity, synaptic transmission

Citation: Chen X-Y, Chen L, Yang W and Xie A-M (2021) GLP-1 Suppresses Feeding Behaviors and Modulates Neuronal Electrophysiological Properties in Multiple Brain Regions. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 14:793004. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2021.793004

Received: 11 October 2021; Accepted: 29 November 2021;

Published: 17 December 2021.

Edited by:

Inmaculada Segura, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, GermanyReviewed by:

Jong-Woo Sohn, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, South KoreaStefan Trapp, University College London, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Chen, Chen, Yang and Xie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wu Yang, eWFuZ3d1Nzg4QDE2My5jb20=; An-Mu Xie, eGllYW5tdUAxNjMuY29t

Xin-Yi Chen

Xin-Yi Chen Lei Chen

Lei Chen Wu Yang1*

Wu Yang1* An-Mu Xie

An-Mu Xie