95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Mol. Neurosci. , 21 November 2019

Sec. Molecular Signalling and Pathways

Volume 12 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2019.00288

This article is part of the Research Topic Neuroscience of Serotonin – New Vistas View all 8 articles

Michael Bader1,2,3,4*

Michael Bader1,2,3,4*Serotonylation, the covalent linkage of serotonin to proteins has been discovered more than 60 years ago but only recently the mechanisms and first functions have been elucidated. It has been found that transglutaminases (TG) such as TG2 and the blood coagulation factor XIIIa are the enzymes which catalyze the linkage of serotonin and other monoamines to distinct glutamine (Gln) residues of target proteins. The first target proteins, small G-proteins and extracellular matrix constituents, were found in platelets and are pivotally involved in platelet aggregation and the formation of thrombi. The serotonylation of the same proteins is also involved in insulin secretion and in the proliferation of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells and thereby in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Recently histones have been described as targets of serotonylation opening the area of transcriptional control to this posttranslational protein modification. Future studies will certainly reveal further target proteins, signaling pathways, cellular processes, and diseases, in which serotonylation or, more general, monoaminylation is important.

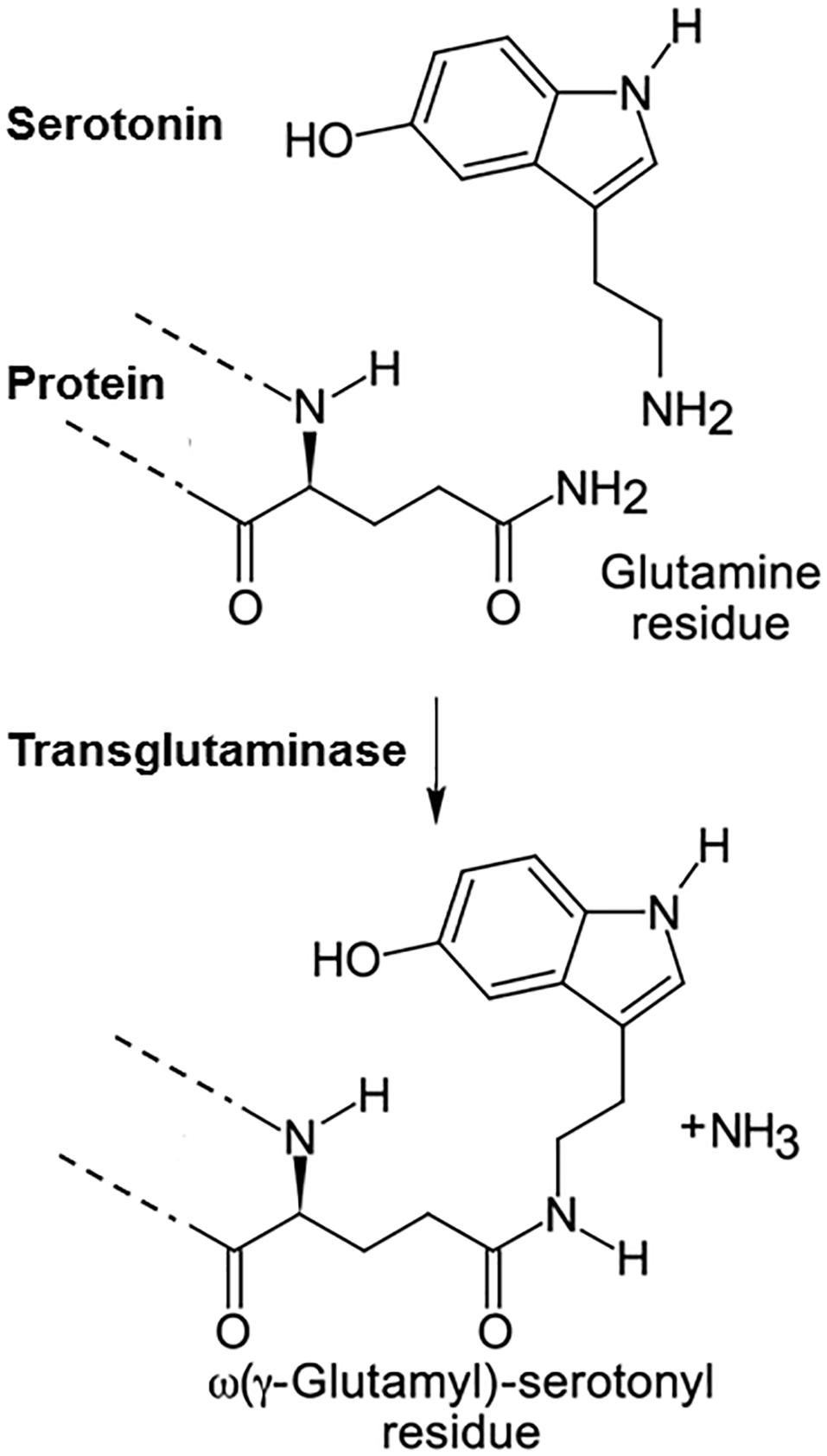

In the late 1950s the group of Waelsch et al. discovered that primary amines can be incorporated into proteins by being covalently linked to glutamine (Gln) residues (Sarkar et al., 1957). These included besides polyamines also monoamines such as serotonin, histamine and norepinephrine (Clarke et al., 1959). This group also discovered the enzyme catalyzing this reaction and coined the term transglutaminase for it (Mycek et al., 1959). However, the function of this posttranslational modification of proteins remained unclear for more than 30 years. In the meantime at least 8 different transglutaminases (TG) were described, TG1-7 and blood coagulation factor XIII, and it was shown that these enzymes also crosslink proteins by linking lysine residues of one protein to glutamines of another (Lorand and Graham, 2003; Eckert et al., 2014; Lai et al., 2017). In contrast to TGs, which are mainly intracellular, factor XIII is extracellular and needs to be activated to factor XIIIa by thrombin during coagulation. TG can stiffen extracellular matrix by “gluing” proteins together and therefore such enzymes are used in the food industry to process meat. The first hint on the function of poly- or monoaminylation of proteins came from studies on bacterial toxins, such as Bordetella toxin, which are also transglutaminases. Intracellularly, they transamidate polyamines to small G-proteins and thereby modulate the immune response of the host (Aktories, 2011). In most cases infectious agents hijack cellular processes and redirect them for their purpose. Thus when we looked for the mechanism by which serotonin regulates platelet aggregation we considered that it could do this via the mechanism the bacterial toxins exploited. Indeed, we discovered that serotonin is covalently bound to small G-proteins in the cytoplasm by the endogenous transglutaminase TG2 (Walther et al., 2003). For this process we coined the term serotonylation (Figure 1). Already one year earlier Dale et al. had discovered that serotonin can be covalently linked to fibronectin and other extracellular proteins of platelets by factor XIIIa, which generates a particularly active form of thrombocytes, called coated platelets (Dale et al., 2002; Dale, 2005).

Figure 1. Serotonylation. Serotonin is covalently linked to glutamine residues in proteins by transglutaminases.

TG2 is the most likely candidate for serotonylation in most organs, since it is widely expressed in contrast to most other members of the TG family (Lorand and Graham, 2003; Eckert et al., 2014; Muma and Mi, 2015) and its reduction using siRNA nearly completely inibited Rac1 serotonylation in neuronal cells (Dai et al., 2008). Moreover TG1 and TG3 could not transamidate small G-proteins (Vowinckel et al., 2012). However, other TGs may anyhow contribute at least in some tissues since for example in aortic smooth muscle cells the specific inhibitor for TG2, Z-DON, reduced transamidation less efficiently than the general TG inhibitor, cystamine (Johnson et al., 2012).

TG2 exhibits a very peculiar way of activation (Katt et al., 2018). It has binding sites for the guanine nucleotides, GTP or GDP, and for calcium which are mutually exclusive. At normal intracellular concentrations of GTP or GDP TG2 remains in a very compact and inactive configuration and only when intracellular calcium concentrations rise e.g., elicited by the activation of cell surface receptors the enzyme adopts the open state and can transamidate substrates. It is not well understood how substrate specificity and the selection of the modified Gln residues is achieved. Accessibility of the Gln residue for the enzyme active site seems to be a major determinant but a specific serotonylation motif has not yet been defined (Lorand and Graham, 2003; Lai et al., 2017).

Dale et al. (2002) purified the serotonylated protein, in their case fibrinogen, hydrolyzed the bond with serotonin using mercaptoethane sulfonic acid and detected serotonin by HPLC. This method however, only works when the protein is present in high amounts and can be easily purified.

The most obvious method to detect the covalent modification of proteins by serotonin is the use of 3H- or 14C-labeled serotonin (Walther et al., 2003; Paulmann et al., 2009; Hummerich et al., 2012; Al-Zoairy et al., 2017; Farrelly et al., 2019). Measuring radioactivity in protein precipitates or autoradiography of protein gels reveals the incorporation of the monoamine in certain proteins. However, this method is not very sensitive due to the weak radioactivity of 3H and 14C.

Other studies used biotinylated serotonin for transglutaminase reactions (Watts et al., 2009). However, when biotin is linked to the amino group of serotonin, TG can not anymore use the adduct as substrate. Moreover the molecule gets very large and can not enter cells anymore. Therefore biorthogonal labeling was developed which used a small alkyne-functionalized serotonin, which can be taken up in cells for the transglutaminase reaction (Lin et al., 2013, 2014). Afterwards a biotin-residue is specifically linked by click-chemistry to this incorporated propargylated serotonin. The biotin-label then allows purification and detection of the serotonylated protein on Western blots and by mass spectrometry (Lin et al., 2013, 2014; Farrelly et al., 2019).

Antibodies against serotonin are produced by injection of animals with conjugates of bovine serum albumin or other proteins with serotonin. Therefore they are well-suited to detect serotonin when it is bound to proteins and can be used in Western blots and for immunoprecipitation (Guilluy et al., 2007, 2009; Dai et al., 2008; Paulmann et al., 2009; Watts et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2011; Abdala-Valencia et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012, 2016; Penumatsa K. et al., 2014; Penumatsa K. C. et al., 2014; Penumatsa et al., 2017; Cui and Kaartinen, 2015; Ivashkin et al., 2015, 2019; Al-Zoairy et al., 2017; Mi et al., 2017). The problem in this case is cross reactivity with other non-serotonylated proteins which can rarely be excluded with any antibody.

Guilluy et al. (2007) have used two-dimensional gel electrophoresis to show that fibronectin changes its isoelectric point when serotonylated. They proved the identity of the spot by Western blot with an anti-serotonin antibody.

Since it was technically difficult to detect protein-bound serotonin some groups used mono-dansylcadaverine (MDC) or 5-(biotinamido) pentylamine as transglutaminase substrates, which can be easily detected in protein gels by fluorescence or by anti-biotin antibodies, respectively (Hummerich and Schloss, 2010; Cui and Kaartinen, 2015; Hummerich et al., 2015; Farrelly et al., 2019). When the binding of these substrates to proteins was inhibited by serotonin, they concluded that serotonin can also be bound to the same proteins. However, this method provides only indirect evidence and needs independent verification. Furthermore, MDC is also often used as inhibitor of transglutaminases.

The most reliable evidence for the existence of serotonylation comes from mass spectrometry of proteins. By this method peptide fragments of proteins were discovered which had exactly the increase in molecular mass as predicted when serotonin was attached to a Gln residue (Farrelly et al., 2019). In most cases also the Gln residue could be distinguished. For this method serotonylated peptides are enriched by immunoprecipitation with serotonin-antibodies and therefore quantitative measurements of serotonylation are hardly possible.

The first described function of protein serotonylation concerned extracellular proteins on hyper-stimulated platelets, in particular fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor, and fibronectin (Dale et al., 2002; Table 1). The covalently bound serotonin residues on these proteins serves as glue to retain the proteins on the surface of these so-called coated platelets (Dale, 2005). The authors provided evidence that factor XIIIa is the main transglutaminase involved, but also TG2 could not be excluded. Serotonylation of fibronectin was later confirmed in a glial cell line by binding of MDC which could be competed by serotonin (Hummerich and Schloss, 2010) and by radioactive serotonin incorporation (Hummerich et al., 2012). Serotonylation of fibronectin led to an increased protein accumulation in the extracellular matrix of these cells (Hummerich et al., 2012). Incorporation of propargyl serotonin followed by mass spectrometry confirmed that Gln34, Gln38 and Gln40 are serotonylated in fibronectin (Lin et al., 2013) as had been shown when fibronectin was labeled with MDC (Hoffmann et al., 2011). Interestingly already in 1976 fibronectin had been discovered as factor XIIIa substrate using MDC (Mosher, 1976; Mosher et al., 1980).

In contrast, the serotonylation of fibronectin in osteoblasts by factor XIIIa inhibits its crosslinking with other proteins and thereby destabilizes the matrix and reduces mineralization (Cui and Kaartinen, 2015).

The group of Fanburg has shown in several publications that upregulated TG2 in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) serotonylates fibronectin in pulmonary arteries and thereby contributes to the disease pathogenesis (Liu et al., 2011; Penumatsa K. C. et al., 2014; Penumatsa and Fanburg, 2014; Liu et al., 2011).

When a certain Gln residue in small G-proteins [e.g., Gln61 in human Ras (Lin et al., 2013)] is serotonylated by TG2 the protein gets constitutively active (Walther et al., 2003; Aktories, 2011). Since there is yet no reverse reaction known inactivation can probably only be achieved by proteasomal degradation, however, there are hints that this degradation gets accelerated by serotonylation (Guilluy et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2013). We first discovered the serotonylation of small G-proteins in platelets where rab4 and rhoA serotonylation contributes to the effect of serotonin on platelet aggregation (Walther et al., 2003; Table 1). Serotonin has a dual role in platelets: it binds to 5-HT2A receptors on the plasma membrane and increases intracellular Ca2+ which activates TG2 and is taken up in the cytoplasm by the serotonin transporter (SERT) serving as substrate for TG2-mediated serotonylation. Serotonylation of small G-proteins probably by TG2 is also involved in insulin secretion by pancreatic beta cells. In these cells, serotonin promotes insulin secretion by covalently modifying rab3a and rab27a, which are essential small G-proteins in the secretory pathway of beta cells (Paulmann et al., 2009). Accordingly, TG2 deficient mice are glucose intolerant and show impaired insulin release (Bernassola et al., 2002). Also insulin sensitivity in muscle seems to be regulated by serotonin via serotonylation of small G-proteins. When L6 skeletal muscle cells are treated with serotonin, rab4 is serotonylated which leads to its activation and thereby to an increased glucose uptake (Al-Zoairy et al., 2017). This effect can be blocked by the TG2 inhibitor MDC.

The serotonin induced proliferative response of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells, which is involved in the pathogenesis of PAH is also mediated by the serotonylation of the small G-protein, rhoA (Guilluy et al., 2007, 2009; Wang et al., 2012). RhoA had already earlier been shown to be a substrate of TG2 at Gln63 using MDC for transamidation (Schmidt et al., 1998). Inhibition of serotonin uptake or of TG2 inhibits rhoA serotonylation, and cellular proliferation and contraction. Accordingly, blockers of TG2, SERT, and rhoA ameliorate PAH development (Guilluy et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2012, 2018).

In primary cortical neurons serotonin via 5-HT2A receptors stimulates TG2 which serotonylates Rac1 and thereby regulates spine density (Dai et al., 2008; Mi et al., 2017). Using propargylated serotonin, Lin et al. (2013) showed that also Ras gets serotonylated and thereby activated in different cell types.

Already in 1996 it had been described that histone 3 can be modified with MDC at Gln5 by TG2 in vitro (Ballestar et al., 1996). However, only recently it was shown that in vivo serotonin is the amine covalently linked by TG2 to this residue of histone H3, using propargylated and radioactive serotonin as well as competition of MDC labeling by serotonin and mass spectrometry (Farrelly et al., 2019; Table 1). While Ballestar et al. (1996) had found also other histones in chicken nucleosomes to be transamidated in vitro, Farrelly et al. (2019) could not confirm these findings in human cells. Future studies need to clarify whether other histones than H3 can be serotonylated in certain species, cell types, or conditions. The serotonylation of Gln5 in histone H3 does not interfere with trimethylation on the neighboring Lys4 (H3K4me3) but exerts a permissive transcriptional activity in neuronal cells in culture and in the developing mouse brain. The reader for this novel histone modification is still unknown but it could be shown that the binding of the transcription factor TFIID to H3K4me3 bearing promoters and consequently transcription initiation gets facilitated by it (Farrelly et al., 2019). Based on these findings histone serotonylation became a novel epigenetic regulatory mechanism (Anastas and Shi, 2019; Fu and Zhang, 2019; Zhao et al., 2019; Zlotorynski, 2019). It remains to be established whether some of the phenotypes observed in mice lacking tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (TPH2) are depending on altered epigenetic control of gene expression due to the lack of brain serotonin (Alenina et al., 2009).

The signaling protein Akt has been revealed as TG2 substrate for serotonylation again in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (Penumatsa K. et al., 2014; Table 1). Since TG2 is upregulated in these cells in PAH, Akt serotonylation may contribute to pulmonary artery remodeling in this disease.

In isolated cardiomyocytes high concentrations of serotonin induces the serotonylation of SERCA2a (Wang et al., 2016; Table 1). The physiological consequences of this modification are however, not clarified.

In cultured aortic smooth muscle cells contractile proteins such as actins and myosins can get serotonylated and the inhibition of TG2 by cystamine reduces serotonin induced contraction of these cells (Watts et al., 2009; Table 1). However, despite that mass spectrometry was performed the serotonylated Gln residues in these proteins were not reported which would have supported the specificity of the labeling method using biotinylated serotonin. Notwithstandingly, at least some of the discovered proteins, such as actin, were confirmed in other studies using propargylated serotonin or MDC and mass spectrometry in different cell types (Lin et al., 2014; Hummerich et al., 2015).

In allergic lung inflammation, the serotonin precursor, 5-hydroxytryptophan ameliorates the symptoms in mice and reduces the amount of serotonylated proteins in lung endothelium, as well as in cultured pulmonary endothelial cells (Abdala-Valencia et al., 2012). However, since anti-serotonin antibodies were used in immunohistochemistry, the serotonylated proteins were not identified.

Ivashkin et al. (2015, 2019) have published two studies in which they used anti-serotonin antibodies to detect serotonylated proteins in embryos of snails, sea urchins, mollusks, and zebrafish. TG2 inhibition by cystamine diminished the signals. In each case they found enrichment of these proteins in nuclei and several bands on Western blots but they did not identify the target proteins.

Compared to other covalent protein modifications, such as phosphorylation, serotonylation has only quite recently been discovered and not many functional consequences of it have been described. Serotonin in the cytoplasm is only available in a limited amount of cell types, which either generate their own serotonin by expressing one of the two tryptophan hydroxylases, TPH1 and TPH2, or import it employing SERT or other less specific transporter such as the Plasma Membrane Monoamine Transporter (PMAT, SLC29A4), and the Organic Cation Transporters OCT1 (SLC22A1), 2 (SLC22A2), or 3 (SLC22A3) (Walther and Bader, 2003; Jonker and Schinkel, 2004; Daws, 2009). Therefore serotonylation is expected not to occur in every cell type. However, other monoamines such as histamine, norepinephrine and dopamine are also substrates of TGs and may replace serotonin in certain cell types by also being used for “monoaminylation” (McConoughey et al., 2010; Walther et al., 2011; Muma and Mi, 2015). This kind of protein modification seem to be evolutionarily old, since it can be found from snails to vertebrates (Ivashkin et al., 2015, 2019) and uses a molecule, serotonin, which is present in nearly all organisms on earth (Turlejski, 1996; Walther et al., 2011; Csaba, 2015).

Still a lot of mechanistic questions remain open. Are all TGs involved in monoaminylation or mainly TG2 and, for extracellular targets, factor XIIIa? How specific are TGs for distinct Gln residues on selected target proteins and how is the specificity brought about? Are there any cofactors involved which confer specificity? Can TGs distinguish between monoamines or is just the concentration in the cell decisive about which monoamine is taken? In this respect, there are first data that TG2 has different affinities for histamine, norepinephrine and serotonin, serotonin being surprisingly the worst substrate (Clarke et al., 1959; Lai and Greenberg, 2013). And finally is there any enzymatic de-monoaminylation?

Despite the few examples of serotonylation which have been discovered so far, it has already been implicated in important physiological and pathophysiological processes. Probably it plays a major role in transcriptional regulation during development in several organisms by modulating histone-dependent epigenetic effects (Ivashkin et al., 2015, 2019; Farrelly et al., 2019). Moreover it contributes to the pathogenesis of PAH (Penumatsa and Fanburg, 2014; Wang et al., 2018) and therefore serotonin may be a valid therapeutic target for this disease (Matthes and Bader, 2018). Extracellular and intracellular serotonylation has been found to be involved in platelet aggregation and insulin secretion again offering therapeutic options (Walther et al., 2003; Dale, 2005; Paulmann et al., 2009). Since TG and serotonin have numerous additional pathophysiologically relevant functions (Berger et al., 2009; Daubert and Condron, 2010; McConoughey et al., 2010; Eckert et al., 2014; Lai et al., 2017; Matthes and Bader, 2018), some of them may be dependent on each other and based on serotonylation of yet unknown target proteins. Accordingly in drosophila and mouse neurons an induced increase of serotonin particularly in the cytoplasm leads to abnormalities reminiscent of neurodegenerative disorders (Daubert and Condron, 2010). In these models as well as in other comparable situations in which cytoplasmatic or nuclear serotonin is increased the signaling via serotonylation should be considered and may offer novel mechanistic insights and therapeutic options for a multitude of diseases.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

MB was supported by grants of the German Ministry for Education and Research [16V0276 and 01EW1602A (ERA-NET NEURON RESPOND)] and DZHK (German Centre for Cardiovascular Research).

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abdala-Valencia, H., Berdnikovs, S., McCary, C. A., Urick, D., Mahadevia, R., Marchese, M. E., et al. (2012). Inhibition of allergic inflammation by supplementation with 5-hydroxytryptophan. Am. J. Physiol. Lung. Cell Mol. Physiol. 303, L642–L660. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00406.2011

Aktories, K. (2011). Bacterial protein toxins that modify host regulatory GTPases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 487–498. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2592

Alenina, N., Kikic, D., Todiras, M., Mosienko, V., Qadri, F., and Plehm, R. (2009). Growth retardation and altered autonomic control in mice lacking brain serotonin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 10332–10337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810793106

Al-Zoairy, R., Pedrini, M. T., Khan, M. I., Engl, J., Tschoner, A., Ebenbichler, C., et al. (2017). Serotonin improves glucose metabolism by Serotonylation of the small GTPase Rab4 in L6 skeletal muscle cells. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 9:1. doi: 10.1186/s13098-016-0201-1

Anastas, J. N., and Shi, Y. (2019). Histone Serotonylation: can the brain have “Happy”. Chromatin. Mol. Cell 74, 418–420. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.04.017

Ballestar, E., Abad, C., and Franco, L. (1996). Core histones are glutaminyl substrates for tissue transglutaminase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 18817–18824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18817

Berger, M., Gray, J. A., and Roth, B. L. (2009). The expanded biology of serotonin. Annu. Rev. Med. 60, 355–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.042307.110802

Bernassola, F., Federici, M., Corazzari, M., Terrinoni, A., Hribal, M. L., and De, L. (2002). Role of transglutaminase 2 in glucose tolerance: knockout mice studies and a putative mutation in a MODY patient. FASEB J. 16, 1371–1378. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0689com

Clarke, D. D., Mycek, M. J., Neidle, A., and Waelsch, H. (1959). The incorporation of amines into protein. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 79, 338–354. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90413-8

Csaba, G. (2015). Biogenic amines at a low level of evolution: production, functions and regulation in the unicellular Tetrahymena. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 62, 93–108. doi: 10.1556/030.62.2015.2.1

Cui, C., and Kaartinen, M. T. (2015). Serotonin (5-HT) inhibits Factor XIII-A-mediated plasma fibronectin matrix assembly and crosslinking in osteoblast cultures via direct competition with transamidation. Bone 72, 43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.11.008

Dai, Y., Dudek, N. L., Patel, T. B., and Muma, N. A. (2008). Transglutaminase-catalyzed transamidation: a novel mechanism for Rac1 activation by 5-hydroxytryptamine2A receptor stimulation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 326, 153–162. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.135046

Dale, G. L. (2005). Coated-platelets: an emerging component of the procoagulant response. J. Thromb. Haemost. 3, 2185–2192. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01274.x

Dale, G. L., Friese, P., Batar, P., Hamilton, S. F., Reed, G. L., Jackson, K. W., et al. (2002). Stimulated platelets use serotonin to enhance their retention of procoagulant proteins on the cell surface. Nature 415, 175–179. doi: 10.1038/415175a

Daubert, E. A., and Condron, B. G. (2010). Serotonin: a regulator of neuronal morphology and circuitry. Trends Neurosci. 33, 424–434. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.05.005

Daws, L. C. (2009). Unfaithful neurotransmitter transporters: focus on serotonin uptake and implications for antidepressant efficacy. Pharmacol. Ther. 121, 89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.10.004

Eckert, R. L., Kaartinen, M. T., Nurminskaya, M., Belkin, A. M., Colak, G., Johnson, G. V., et al. (2014). Transglutaminase regulation of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 94, 383–417. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2013

Farrelly, L. A., Thompson, R. E., Zhao, S., Lepack, A. E., Lyu, Y., Bhanu, N. V., et al. (2019). Histone serotonylation is a permissive modification that enhances TFIID binding to H3K4me3. Nature 567, 535–539. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1024-7

Fu, L., and Zhang, L. (2019). Serotonylation: a novel histone H3 marker. Signal Trans. Target Ther. 4:15.

Guilluy, C., Eddahibi, S., Agard, C., Guignabert, C., Izikki, M., and Tu, L. (2009). RhoA and Rho kinase activation in human pulmonary hypertension: role of 5-HT signaling. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 179, 1151–1158. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-691OC

Guilluy, C., Rolli-Derkinderen, M., Tharaux, P. L., Melino, G., Pacaud, P., and Loirand, G. (2007). Transglutaminase-dependent RhoA activation and depletion by serotonin in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 2918–2928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m604195200

Hoffmann, B. R., Annis, D. S., and Mosher, D. F. (2011). Reactivity of the N-terminal region of fibronectin protein to transglutaminase 2 and factor XIIIA. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 32220–32230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.255562

Hummerich, R., Costina, V., Findeisen, P., and Schloss, P. (2015). Monoaminylation of fibrinogen and glia-derived proteins: indication for similar mechanisms in posttranslational protein modification in blood and brain. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 6, 1130–1136. doi: 10.1021/cn5003286

Hummerich, R., and Schloss, P. (2010). Serotonin–more than a neurotransmitter: transglutaminase-mediated serotonylation of C6 glioma cells and fibronectin. Neurochem. Int. 57, 67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.04.020

Hummerich, R., Thumfart, J. O., Findeisen, P., Bartsch, D., and Schloss, P. (2012). Transglutaminase-mediated transamidation of serotonin, dopamine and noradrenaline to fibronectin: evidence for a general mechanism of monoaminylation. FEBS Lett. 586, 3421–3428. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.07.062

Ivashkin, E., Khabarova, M. Y., Melnikova, V., Nezlin, L. P., Kharchenko, O., Voronezhskaya, E. E., et al. (2015). Serotonin mediates maternal effects and directs developmental and behavioral changes in the progeny of snails. Cell Rep. 12, 1144–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.022

Ivashkin, E., Melnikova, V., Kurtova, A., Brun, N. R., Obukhova, A., and Khabarova, M. Y. (2019). Transglutaminase activity determines nuclear localization of serotonin immunoreactivity in the early embryos of invertebrates and vertebrates. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 10, 3888–3899. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00346

Johnson, K. B., Petersen-Jones, H., Thompson, J. M., Hitomi, K., Itoh, M., and Bakker, E. N. (2012). Vena cava and aortic smooth muscle cells express transglutaminases 1 and 4 in addition to transglutaminase 2. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 302, H1355–H1366. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00918.2011

Jonker, J. W., and Schinkel, A. H. (2004). Pharmacological and physiological functions of the polyspecific organic cation transporters: OCT1, 2, and 3 (SLC22A1-3). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 308, 2–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053298

Katt, W. P., Antonyak, M. A., and Cerione, R. A. (2018). Opening up about tissue transglutaminase: when conformation matters more than enzymatic activity. Med. One 3:e180011. doi: 10.20900/mo.20180011

Lai, T. S., and Greenberg, C. S. (2013). Histaminylation of fibrinogen by tissue transglutaminase-2 (TGM-2): potential role in modulating inflammation. Amino Acids 45, 857–864. doi: 10.1007/s00726-013-1532-y

Lai, T. S., Lin, C. J., and Greenberg, C. S. (2017). Role of tissue transglutaminase-2 (TG2)-mediated aminylation in biological processes. Amino Acids 49, 501–515. doi: 10.1007/s00726-016-2270-8

Lin, J. C., Chou, C. C., Gao, S., Wu, S. C., Khoo, K. H., and Lin, C. H. (2013). An in vivo tagging method reveals that Ras undergoes sustained activation upon transglutaminase-mediated protein serotonylation. Chembiochem 14, 813–817. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300050

Lin, J. C., Chou, C. C., Tu, Z., Yeh, L. F., Wu, S. C., Khoo, K. H., et al. (2014). Characterization of protein serotonylation via bioorthogonal labeling and enrichment. J. Proteome Res. 13, 3523–3529. doi: 10.1021/pr5003438

Liu, Y., Wei, L., Laskin, D. L., and Fanburg, B. L. (2011). Role of protein transamidation in serotonin-induced proliferation and migration of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 44, 548–555. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0078OC

Lorand, L., and Graham, R. M. (2003). Transglutaminases: crosslinking enzymes with pleiotropic functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 140–156. doi: 10.1038/nrm1014

Matthes, S., and Bader, M. (2018). Peripheral serotonin synthesis as a new drug target. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 39, 560–572. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2018.03.004

McConoughey, S. J., Basso, M., Niatsetskaya, Z. V., Sleiman, S. F., Smirnova, N. A., and Langley, B. C. (2010). Inhibition of transglutaminase 2 mitigates transcriptional dysregulation in models of Huntington disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 2, 349–370. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000084

Mi, Z., Si, T., Kapadia, K., Li, Q., and Muma, N. A. (2017). Receptor-stimulated transamidation induces activation of Rac1 and Cdc42 and the regulation of dendritic spines. Neuropharmacology 117, 93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.01.034

Mosher, D. F. (1976). Action of fibrin-stabilizing factor on cold-insoluble globulin and alpha2-macroglobulin in clotting plasma. J. Biol. Chem. 251, 1639–1645.

Mosher, D. F., Schad, P. E., and Vann, J. M. (1980). Cross-linking of collagen and fibronectin by factor XIIIa. Localization of participating glutaminyl residues to a tryptic fragment of fibronectin. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 1181–1188.

Muma, N. A., and Mi, Z. (2015). Serotonylation and transamidation of other monoamines. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 6, 961–969. doi: 10.1021/cn500329r

Mycek, M. J., Clarke, D. D., Neidle, A., and Waelsch, H. (1959). Amine incorporation into insulin as catalyzed by transglutaminase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 84, 528–540. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90613-7

Paulmann, N., Grohmann, M., Voigt, J. P., Bert, B., Vowinckel, J., Bader, M., et al. (2009). Intracellular serotonin modulates insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells by protein serotonylation. PLoS Biol. 7:e1000229. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000229

Penumatsa, K., Abualkhair, S., Wei, L., Warburton, R., Preston, I., Hill, N. S., et al. (2014). Tissue transglutaminase promotes serotonin-induced AKT signaling and mitogenesis in pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells. Cell. Signal. 26, 2818–2825. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.09.002

Penumatsa, K. C., Toksoz, D., Warburton, R. R., Hilmer, A. J., Liu, T., Khosla, C., et al. (2014). Role of hypoxia-induced transglutaminase 2 in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung. Cell Mol. Physiol. 307, L576–L585. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00162.2014

Penumatsa, K. C., and Fanburg, B. L. (2014). Transglutaminase 2-mediated serotonylation in pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Lung. Cell Mol. Physiol. 306, L309–L315. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00321.2013

Penumatsa, K. C., Toksoz, D., Warburton, R. R., Kharnaf, M., Preston, I. R., Kapur, N. K., et al. (2017). Transglutaminase 2 in pulmonary and cardiac tissue remodeling in experimental pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Lung. Cell Mol. Physiol. 313, L752–L762. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00170.2017

Sarkar, N. K., Clarke, D. D., and Waelsch, H. (1957). An enzymically catalyzed incorporation of amines into proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 25, 451–452. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(57)90512-7

Schmidt, G., Selzer, J., Lerm, M., and Aktories, K. (1998). The Rho-deamidating cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 from Escherichia coli possesses transglutaminase activity. Cysteine 866 and histidine 881 are essential for enzyme activity. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 13669–13674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13669

Turlejski, K. (1996). Evolutionary ancient roles of serotonin: long-lasting regulation of activity and development. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 56, 619–636.

Vowinckel, J., Stahlberg, S., Paulmann, N., Bluemlein, K., Grohmann, M., Ralser, M., et al. (2012). Histaminylation of glutamine residues is a novel posttranslational modification implicated in G-protein signaling. FEBS Lett. 586, 3819–3824. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.09.027

Walther, D. J., and Bader, M. (2003). A unique central tryptophan hydroxylase isoform. Biochem. Pharmacol. 66, 1673–1680. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00556-2

Walther, D. J., Peter, J. U., Winter, S., Höltje, M., Paulmann, N., Grohmann, M., et al. (2003). Serotonylation of small GTPases is a signal transduction pathway that triggers platelet α-granule release. Cell 115, 851–862. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01014-6

Walther, D. J., Stahlberg, S., and Vowinckel, J. (2011). Novel roles for biogenic monoamines: from monoamines in transglutaminase-mediated post-translational protein modification to monoaminylation deregulation diseases. FEBS J. 278, 4740–4755. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08347.x

Wang, H. M., Liu, W. Z., Tang, F. T., Sui, H. J., Zhan, X. J., and Wang, H. X. (2018). Cystamine slows but not inverses the progression of monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension in rats. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 96, 783–789. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2017-0720

Wang, H. M., Wang, Y., Liu, M., Bai, Y., Zhang, X. H., Sun, Y. X., et al. (2012). Fluoxetine inhibits monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial remodeling involved in inhibition of RhoA-Rho kinase and Akt signalling pathways in rats. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 90, 1506–1515. doi: 10.1139/y2012-108

Wang, Q., Wang, D., Yan, G., Qiao, Y., Sun, L., Zhu, B., et al. (2016). SERCA2a was serotonylated and may regulate sino-atrial node pacemaker activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 480, 492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.10.082

Watts, S. W., Priestley, J. R., and Thompson, J. M. (2009). Serotonylation of vascular proteins important to contraction. PLoS One 4:e5682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005682

Zhao, S., Yue, Y., Li, Y., and Li, H. (2019). Identification and characterization of ‘readers’ for novel histone modifications. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 51, 57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2019.04.001

Keywords: serotonin, histone, G-protein, protein modification, pulmonary hypertension, epigenetics, monoaminylation, transglutaminase

Citation: Bader M (2019) Serotonylation: Serotonin Signaling and Epigenetics. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 12:288. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00288

Received: 19 September 2019; Accepted: 12 November 2019;

Published: 21 November 2019.

Edited by:

Alexander Kulikov, Russian Academy of Sciences, RussiaReviewed by:

Heinrich J. G. Matthies, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, United StatesCopyright © 2019 Bader. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michael Bader, bWJhZGVyQG1kYy1iZXJsaW4uZGU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.