- Department of Biology, Georgia Southern University-Armstrong Campus, Savannah, GA, United States

The sequencing of the zebrafish genome, the emergence of powerful gene-editing tools, and the development of in vivo imaging techniques have propelled the economical zebrafish into prominence as a biomedical research model. Neurodegenerative disorders with a cholinergic component, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, are currently modeled using zebrafish. Still, the utility of zebrafish as a research model will not be fully realized until their neurophysiological properties are thoroughly characterized. In mammals, the coupling of cholinergic receptors to the phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 β (GSK3β) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) is of critical importance to cognitive processes and imparts protection against neuropathogenic events. Similarly, it is known that cholinergic receptors are required for learning and memory in zebrafish and that in vivo activation of cholinergic receptors induces transient changes in evoked synaptic transmission in the telencephalon. However, the intracellular events mediating cholinergic processes in zebrafish have yet to be elucidated. In the current study, an ex vivo drug treatment assay was used to demonstrate that carbachol (CCh)-mediated cholinergic stimulation of the intact adult zebrafish brain induces phosphorylation of GSK3β and ERK1/2 in the zebrafish telencephalon. These findings suggest GSK3β and ERK1/2 may underly cognitive processes in zebrafish.

Introduction

The contributions of cholinergic neurons span widely across the mammalian brain, including critical roles in cortical and hippocampal processing, attention, decision-making, and the encoding and retrieval of memories (Muir et al., 1992; Bartus, 2000; Rogers and Kesner, 2004; Ferreira-Vieira et al., 2016). Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, Down syndrome, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and schizophrenia are all marked by cholinergic dysfunction (Yates et al., 1980; Dubois et al., 1983; Tagliavini et al., 1984; Barron et al., 1987; Kato, 1989; Terry, 2008; Ferreira-Vieira et al., 2016; Pepeu and Giovannini, 2017), which may manifest as a profound loss of cholinergic neurons—up to 75% of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain, septum and ventral striatum are lost in the AD brain (Davies and Maloney, 1976; Arendt et al., 1983; Nagai et al., 1983; Whitehouse et al., 1983), or as abnormalities in acetylcholine receptor (AChR) function—coupling of AChRs to their downstream signaling proteins is impaired in post-mortem brain tissue from AD patients (Salah-Uddin et al., 2008).

AChRs may be broadly categorized into the G-protein-coupled muscarinic AChRs (mAChRs), which comprise five heterogeneous subtypes (M1—M5; Caulfield and Birdsall, 1998), and the ionotropic nicotinic AChRs (nAChRs). Frequently, the non-specific cholinergic agonist carbachol (CCh), applied to brain slice preparations and neuronal cell culture has been used to examine the links between AChRs, intracellular protein kinases, synaptic plasticity, and disease pathogenesis. For example, Rosenblum et al. (2000) demonstrated that stimulation of AChRs in rat brain slices and neuronal cultures with CCh induces activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) I/II, which was also shown to be required for induction of long-term potentiation. Additionally, the pairing of AChR-subtype-specific inhibitors with CCh stimulation in vitro has been used to demonstrate that cholinergic stimulation induces an M1 AChR-dependent long-term synaptic depression in rat hippocampal slices in a mechanism dependent upon ERK I/II activation (Scheiderer et al., 2006, 2008). In the context of neurodegenerative disease, Forlenza et al. (2000) demonstrated that glycogen synthase kinase-3 β (GSK-3β)-mediated phosphorylation of tau is reduced in neurons treated with CCh, and Qiu et al. (2003) showed that CCh treatment is sufficient to reduce amyloidogenic processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP) in hippocampal slices. These and other studies now constitute a large body of evidence demonstrating the importance of the phosphorylated forms of ERK1/2 (Melancon et al., 2013; Giovannini et al., 2015) and GSK3β (Hooper et al., 2007; Serenó et al., 2009) in promoting synaptic plasticity and preventing neuropathology.

While cholinergic neurophysiological processes, and their coupling to intracellular protein kinases, have been extensively elucidated in the mammalian brain, much remains unknown about fundamental neurophysiology in zebrafish (Danio rerio), which is gaining in popularity as a model organism to study brain diseases and disorders (Paquet et al., 2010; Xi et al., 2011; Santana et al., 2012; Ng et al., 2013). Anatomically, it is known that functional equivalents of the mammalian amygdala, striatum and hippocampus are represented in the zebrafish brain by the medial zone of the dorsal telencephalon (Lau et al., 2011), dorsal nucleus of the ventral telencephalon (Lau et al., 2011), and lateral zone of the dorsal telencephalon (Rodríguez-Expósito et al., 2017), respectively. Some cellular neurophysiological processes have been shown to be conserved between mammals and zebrafish: as in rodent hippocampus, high-frequency stimulation-induced long-term potentiation of synaptic strength is N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-dependent in the zebrafish telencephalon (Nam et al., 2004; Ng et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2017). Consistent with these findings, treatment of adult zebrafish with an NMDA-receptor antagonist prevents acquisition of spatial (Cognato et al., 2012) and emotional (Ng et al., 2012) memories. Notably, fear memory impairment in zebrafish caused by treatment with the NMDA-receptor antagonist MK-801 is associated with inactivation of telencephalic ERK (Ng et al., 2012).

Evidence from histochemical (Clemente et al., 2004) and biochemical (Williams and Messer, 2004) experiments indicate widespread cholinergic innervation in the zebrafish brain. Similar to mammals, zebrafish AChRs modulate synaptic strength, as bath application of CCh induces transient synaptic depression in the telencephalon (Park et al., 2008), supporting a role for AChRs in synaptic plasticity in telencephalic circuits. Accordingly, blocking mAChRs using scopolamine prevents spatial and emotional memory function (Kim et al., 2010; Cognato et al., 2012). Additionally, nAChR agonists improve zebrafish spatial discrimination learning (Levin et al., 2006). However, the intracellular signaling events that underlie AChR-dependent cognitive processes in adult zebrafish remain undescribed, and, therefore, further characterization is needed to elucidate the degree of functional conservation between mammalian and zebrafish brains.

Given the importance of GSK3β and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in the neuroprotective and pro-cognitive effects of AChRs in mammals, and the relative paucity of information describing AChR interactions with protein kinases in the zebrafish brain, the current study investigated if CCh-mediated stimulation of the zebrafish brain is sufficient to induce phosphorylation of GSK3β and ERK1/2 in the zebrafish telencephalon.

Materials and Methods

Test Subjects

Male and female adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) were purchased from a local supplier (Savannah, GA, USA), and maintained as reported by Mans et al. (2018). All experimental procedures were approved by Georgia Southern University Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee (IACUC).

Brain Extraction

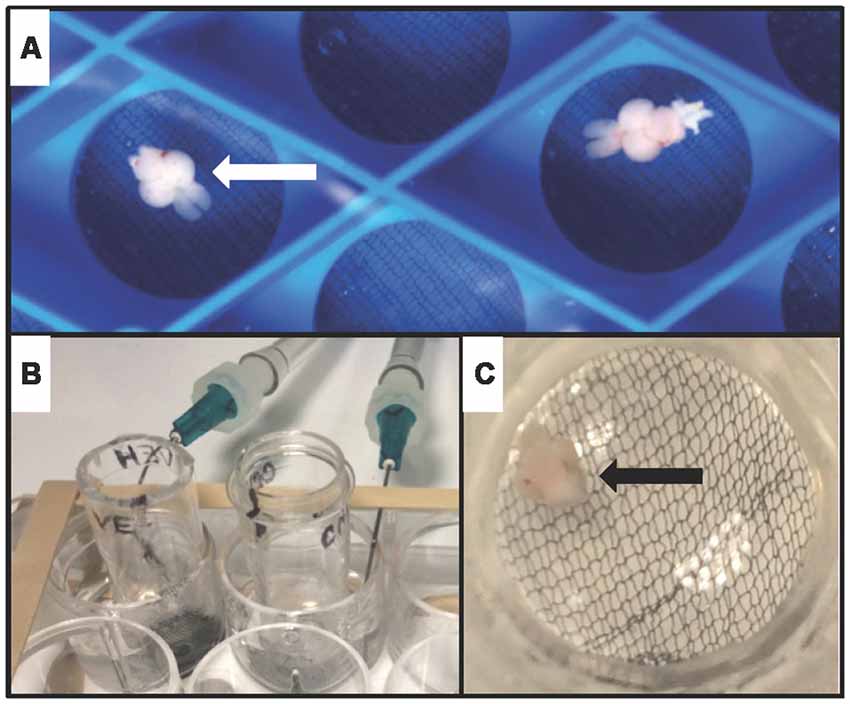

Fish were anesthetized by immersion in tricaine methanesulfonate (300 μg/mL) before decapitation, and the head was stabilized in a foam block submerged in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) infused with 95% oxygen/5% carbon dioxide. aCSF consisted of (in mM): 120 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 2.0 CaCl, 1.3 MgSO4, 1.3 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3 and 11 glucose (Nam et al., 2004). Extracted brains recovered in oxygenated aCSF at room temperature for at least 30 min prior to use (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Whole-brain ex vivo zebrafish treatment assay. (A) Whole brains from adult zebrafish (arrowhead) were removed, and allowed to recover in oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF)-filled chambers. (B) During treatment, brains were transferred to custom-made treatment chambers inserted into wells of a 12-well tissue culture plate containing vehicle (aCSF) or aCSF plus carbachol (CCh). 95% oxygen and 5% carbon dioxide were delivered to each well via a 14G needle. (C) View of a single brain (arrowhead) suspended on mesh at the base of a treatment chamber.

Drug Preparation

A 10 mM CCh stock solution was prepared in dH2O, aliquoted and stored at −20°C before use. On the day of use, 2 μL of CCh stock was diluted in 2 mL of aCSF.

Ex vivo Drug Treatment

Brains were treated in chambers inserted into wells of a 12-well tissue culture plate containing either 2 mL of vehicle (aCSF) or aCSF plus 10 μM CCh (Figures 1B,C) saturated with 95% oxygen/5% carbon dioxide.

Tissue Collection

After treatment, the telencephalon was removed and immediately placed into 50 μL of homogenization buffer in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. Homogenization buffer consisted of T-Per Tissue Protein Extraction Reagent (Fisher Scientific) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Pierce). For samples intended for synaptosomal isolation, homogenization buffer volume was increased to 300 μL, and T-Per was replaced with 0.32 M sucrose and 5 mM HEPES (Wirths, 2017). All samples were homogenized at 10,000 rpm for 60 s, then frozen at −20°C.

Sample Purification

Samples were centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 min at 4°C to remove unhomogenized fragments, and the supernatant was collected for Western blot analysis. To assess synaptic proteins, the crude synaptosomal isolation protocol by Wirths (2017) was adapted. Briefly, homogenate was subjected to 30 pulses with a sonicator and centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The resulting pellet, containing the synaptic fraction, was re-constituted in 50 μL of HEPES-based homogenization buffer.

Western Blot

Protein concentrations were determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific). Samples containing 20 μg of total protein were prepared in SDS sample buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) using standard methods. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE in 10% polyacrylamide gels and blotted to PVDF membranes by semi-dry transfer. Membranes were blocked in 3% milk/TBST for 1 h at room temperature prior to application of primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Chemiluminescent protein detection occurred by application of HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature followed by treatment with Clarity Western ECL (Bio-Rad) peroxidase substrate. Blot luminescence was digitally imaged using a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System with Image Lab Software Version 5.1 (Bio-Rad). Protein levels were quantified by densitometry using ImageJ software (NCBI). A mild or harsh stripping protocol (Abcam) was performed prior to blot re-probing.

Antibodies for Western Blotting

The primary antibodies were rabbit anti-phospho-GSK-3α/β (Ser21/9; Cell Signaling, #9331), rabbit anti-GSK-3β (Cell Signaling, #9315), rabbit anti-tubulin (Tuba1; GeneTex, GTX124965), rabbit anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2; Thr202/Tyr204; Cell Signaling, #4370), mouse anti-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2; Cell Signaling, #9107), rabbit anti-post-synaptic density-95 (PSD-95; GeneTex, GTX80682), and rabbit anti-beta-actin (Abcam, ab8227). The secondary antibodies were HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit (Cell Signaling, 7074S) or HRP-conjugated anti-mouse (Bio-Rad). All antibodies were diluted in 3% milk/TBST, except phospho-specific antibodies, which were diluted in 2.5% bovine serum albumin/TBST.

Data Analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Comparison of data from different treatment groups was performed by Students t-test and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are graphed with control values set at 1.0.

Results

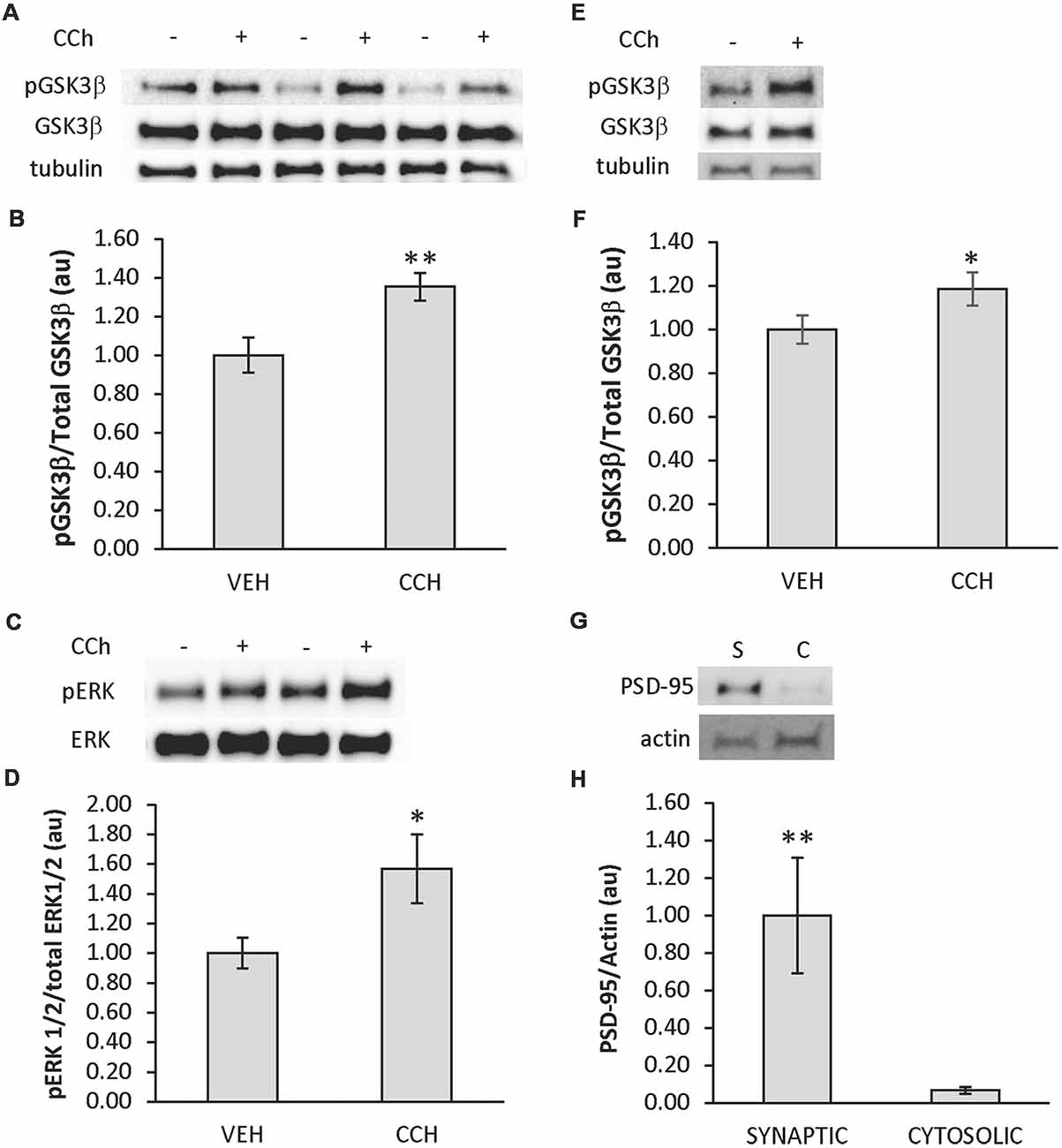

In order to test if cholinergic stimulation of the zebrafish brain induces phosphorylation of GSK3β and ERK1/2 in the telencephalon, an ex vivo drug incubation assay was developed. The assay consisted of intact adult zebrafish brains placed in custom-made submersion chambers inserted into wells of a 12-well tissue culture plate that were filled with oxygenated aCSF (Figure 1). Using this assay, whole brains isolated from adult zebrafish were treated with the cholinergic agonist CCh (50 μM) or vehicle (veh) ex vivo for 10 min followed by biochemical analysis using Western blot. Employing an anti-phospho S9 GSK3β antibody in combination with an anti-GSK3β antibody, we determined CCh treatment induced phosphorylation of GSK3β in the telencephalon (P = 0.002; Figures 2A,B), as the mean pGSK3β/GSK3β ratio was 35% higher in CCh-treated samples (n = 14) relative to veh-treated controls (n = 14). Levels of total GSK3β were also assessed after CCh treatment using the GSK3β/tubulin ratio. Mean total GSK3β was unchanged after CCh treatment (data not shown). To determine if CCh treatment also induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in CCh-treated samples, veh- and CCh-treated samples analyzed for GSK3β were analyzed using anti-phospho p44/p42 MAPK and anti-p44/p42MAPK antibodies. We determined that CCh treatment for 10 min caused a 57% increase in the mean ERK1/2 phosphorylation in the telencephalon (P = 0.017; Figures 2C,D).

Figure 2. CCh induces phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 β (GSK3β) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK 1/2) in the telencephalon of adult zebrafish. (A) Representative Western blot of telencephalic tissue from brains incubated in aCSF ± CCh that was probed with pGSK3, GSK3β and tubulin-specific antibodies. (B) Quantitative analysis of Western blots showing the ratio of pGSK3β/total GSK3β increased in the telencephalon when CCh was applied ex vivo (n = 14 veh; 14 CCh). (C) Representative Western blot of telencephalic tissue from brains incubated in aCSF ± CCh that was probed with pERK, and ERK-specific antibodies. (D) Quantitative analysis of Western blots showing the ratio of pERK/total ERK increased in the telencephalon when CCh was applied ex vivo (n = 14 veh; 14 CCh). (E) Representative Western blots of the synaptic fraction of telencephalic tissue from brains incubated in aCSF ± CCh that was probed with pGSK3, GSK3β, and tubulin-specific antibodies. (F) Quantitative analysis of Western blots showing the ratio of pGSK3β/total GSK3β increased in synaptic fractions from telencephalon when CCh was applied ex vivo (n = 11 veh; 11 CCh). (G) Representative Western blot probed with post-synaptic density-95 protein (PSD-95) and actin-specific antibodies confirming PSD-95 in synaptic (S) vs. cytosolic (C) fractions. (H) Quantitative analysis of Western blots showing the enrichment of PSD-95 in synaptic fractions (n = 7 synaptic; 7 cytosolic). In plots, values presented as mean ± SE, arbitrary units. Control set at 1.0. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (t-test).

Additionally, due to the importance of GSK3β in synaptic plasticity, CCh treatments were repeated, and the expression of pGSK3β in the synaptic pool of the telencephalon was evaluated in veh-treated (n = 11) and CCh-treated (n = 11) samples subjected to a crude synaptosomal isolation protocol adapted from Wirths (2017) followed by Western blot analysis. It was determined that CCh induced a 19% increase in the expression of synaptic pGSK3β (P = 0.04; Figures 2E,F). In control experiments using remaining samples, the synaptic marker PSD-95 was shown to be enriched in the synaptic samples (n = 7) compared to cytosolic samples (n = 7; P = 0.005; Figures 2G,H). Due to the depletion of samples, a similar analysis of synaptic pERK1/2 could not be performed.

Discussion

The current study was conducted to further elucidate the degree of functional conservation between mammalian and zebrafish brains. It was determined that widespread stimulation of the cholinergic system via bath-application of CCh ex vivo results in phosphorylation of GSK3β and ERK1/2 in the telencephalon, a brain area containing functional homologs to the mammalian amygdala, hippocampus and striatum. These results have implications for the study of learning and memory processes in zebrafish, and offer insights into how zebrafish might complement mammalian and tissue-culture model systems in the study of brain diseases with a cholinergic component.

To date, no studies have been published directly testing if zebrafish AChRs—which are required for normal learning and memory in zebrafish (Kim et al., 2010; Cognato et al., 2012)—require GSK3β or ERK1/2 to modulate plasticity. To begin investigating this question, our experiments employed bath application of CCh for 10 min, followed by Western blot analysis of the telencephalon. This treatment has been used previously in mammalian brain slices and neuronal cell culture to demonstrate the involvement of ERK1/2 in hippocampal synaptic plasticity (Rosenblum et al., 2000; Scheiderer et al., 2006). Additionally, an experimental design similar to that of the current study using isolated whole zebrafish telencephalon demonstrated that a 10-min CCh bath application induces synaptic plasticity in the dorsal telencephalic region of zebrafish (Park et al., 2008). Notably, the concentration of CCh used in the current study matches that used in the studies described above. Thus, the CCh-induced phosphorylation of GSK3β and ERK1/2 in the zebrafish telencephalon reported here suggests that zebrafish AChRs may similarly couple to GSK3β and ERK while modulating synapses. It is important to note that control experiments using AChR inhibitors and more isolated experimental systems, such as cell culture, will be required to fully demonstrate zebrafish AChR coupling to GSK3β and ERK1/2, and additional electrophysiology and behavior experiments are required to connect AChRs, intracellular kinases and learning and memory in zebrafish.

With the growth in utilization of zebrafish as a model organism (Paquet et al., 2010; Xi et al., 2011; Santana et al., 2012) has come an appreciation for their value in complementing more traditional mammalian models. For example, it was recently discovered that two parallel molecular signaling pathways may regulate anxiety in humans—one pathway initially characterized in mice and the other subsequently discovered in zebrafish (Xie et al., 2017). The ex vivo preparation in the current study offers several advantages. First, the method is highly cost-effective, as the incubation chambers may be constructed from readily-available laboratory supplies, and the volume of drug required for treatments is minimal. Second, the assay employs a brain with largely intact internal circuitry, which increases the likelihood of findings translating to the in vivo setting. Conversely, the use of a largely-intact brain presents challenges in predicting the mechanisms underlying the observations made using the ex vivo assay. Finally, the assay employs an adult, rather than a larval physiological system, which may be pertinent to studying processes in the aging brain. Therefore, discoveries made in larval systems employing in vivo imaging or high-throughput screens could be validated in a fully-developed system using the ex vivo assay described here. It will be of great value to continue exploring the potential coupling of zebrafish AChRs to GSK3β and ERK described in the current study, such that the limitations and opportunities implicit to zebrafish as a model organism for complex brain diseases are fully understood.

Ethics Statement

All experimental procedures were approved by the Georgia Southern University Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee (IACUC).

Author Contributions

RM conceived and designed the study, performed drug treatments, tissue collection, sample purification and Western blots, completed statistical analysis and interpretation of the data, and prepared the manuscript. KH, CP, GP, NS and MS-J participated in drug treatments, tissue collection, sample purification and Western blots. RM and CP constructed the resting and treatment chambers for extracted zebrafish brains.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Biology, Georgia Southern University and a Research Seed Funding Award from the Office of Faculty Development, Georgia Southern University.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Arendt, T., Bigl, V., Arendt, A., and Tennstedt, A. (1983). Loss of neurons in the nucleus basalis of meynert in Alzheimer’s disease, paralysis agitans and Korsakoff’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 61, 101–108. doi: 10.1007/bf00697388

Barron, S. A., Mazliah, J., and Bental, E. (1987). Sympathetic cholinergic dysfunction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neurol. Scand. 75, 62–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1987.tb07890.x

Bartus, R. T. (2000). On neurodegenerative diseases, models, and treatment strategies: lessons learned and lessons forgotten a generation following the cholinergic hypothesis. Exp. Neurol. 163, 495–529. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7397

Caulfield, M. P., and Birdsall, N. J. (1998). International union of pharmacology. XVII. classification of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 50, 279–290.

Clemente, D., Porteros, A., Weruaga, E., Alonso, J. R., Arenzana, F. J., Aijón, J., et al. (2004). Cholinergic elements in the zebrafish central nervous system: histochemical and immunohistochemical analysis. J. Comp. Neurol. 474, 75–107. doi: 10.1002/cne.20111

Cognato, G. P., Bortolotto, J. W., Blazina, A. R., Christoff, R. R., Lara, D. R., Vianna, M. R., et al. (2012). Y-Maze memory task in zebrafish (Danio rerio): the role of glutamatergic and cholinergic systems on the acquisition and consolidation periods. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 98, 321–328. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2012.09.008

Davies, P., and Maloney, A. J. (1976). Selective loss of central cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 2:1403. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)91936-x

Dubois, B., Ruberg, M., Javoy-Agid, F., Ploska, A., and Agid, Y. (1983). A subcortico-cortical cholinergic system is affected in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. 288, 213–218. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90096-3

Ferreira-Vieira, T. H., Guimaraes, I. M., Silva, F. R., and Ribeiro, F. M. (2016). Alzheimer’s disease: targeting the cholinergic system. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 14, 101–115. doi: 10.2174/1570159X13666150716165726

Forlenza, O. V., Spink, J. M., Dayanandan, R., Anderton, B. H., Olesen, O. F., and Lovestone, S. (2000). Muscarinic agonists reduce tau phosphorylation in non-neuronal cells via GSK-3β inhibition and in neurons. J. Neural Transm. 107, 1201–1212. doi: 10.1007/s007020070034

Giovannini, M. G., Lana, D., and Pepeu, G. (2015). The integrated role of Ach, ERK and mTOR in the mechanisms of hippocampal inhibitory avoidance memory. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 119, 18–33. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2014.12.014

Hooper, C., Markevich, V., Plattner, F., Killick, R., Schofield, E., Engel, T., et al. (2007). Glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibition is integral to long-term potentiation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 25, 81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05245.x

Kato, T. (1989). Choline acetyltransferase activities in single spinal motor neurons from patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurochem. 52, 636–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb09167.x

Kim, Y. H., Lee, Y., Kim, D., Jung, M. W., and Lee, C. J. (2010). Scopolamine-induced learning impairment reversed by physostigmine in zebrafish. Neurosci. Res. 67, 156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2010.03.003

Lau, B. Y., Mathur, P., Gould, G. G., and Guo, S. (2011). Identification of a brain center whose activity discriminates a choice behavior in zebrafish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 108, 2581–2586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018275108

Levin, E. D., Limpuangthip, J., Rachakonda, T., and Peterson, M. (2006). Timing of nicotine effects on learning in zebrafish. Psychopharmacology 184, 547–552. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0162-9

Mans, R. A., Hinton, K. D., Rumer, A. E., Zellner, K. A., Blankenship, E. A., Kerkes, L. M., et al. (2018). Expression of an arc-immunoreactive Protein in the adult zebrafish brain increases in response to a novel environment. Georgia J. Sci. 76:2. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.gaacademy.org/gjs/vol76/iss2/2 [Accessed May 15, 2018].

Melancon, B. J., Tarr, J. C., Panarese, J. D., Wood, M. R., and Lindsley, C. W. (2013). Allosteric modulation of the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor: improving cognition and a potential treatment for schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Discov. Today 18, 1185–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.09.005

Muir, J. L., Dunnett, S. B., Robbins, T. W., and Everitt, B. J. (1992). Attentional functions of the forebrain cholinergic systems: effects of intraventricular hemicholinium, physostigmine, basal forebrain lesions and intracortical grafts on a multiple-choice serial reaction time task. Exp. Brain Res. 89, 611–622. doi: 10.1007/bf00229886

Nagai, T., McGeer, P. L., Peng, J. H., McGeer, E. G., and Dolman, C. E. (1983). Choline acetyltransferase immunohistochemistry in brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients and controls. Neurosci. Lett. 36, 195–199. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(83)90264-1

Nam, R. H., Kim, W., and Lee, C. J. (2004). NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation in the telencephalon of the zebrafish. Neurosci. Lett. 370, 248–251. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.08.037

Ng, M., Tang, T., Ko, M., Wu, Y., Hsu, P., Yang, Y., et al. (2012). Stimulation of the lateral division of the dorsal telencephalon induces synaptic plasticity in the medial division of the adult zebrafish. Neurosci. Lett. 512, 109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.01.070

Ng, M., Yang, Y., and Lu, K. (2013). Behavioral and synaptic circuit features in a zebrafish model of fragile X syndrome. PLoS One 8:e51456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051456

Paquet, D., Schmid, B., and Haass, C. (2010). Transgenic zebrafish as a novel animal model to study tauopathies and other neurodegenerative disorders in vivo. Neurodegener. Dis. 7, 99–102. doi: 10.1159/000285515

Park, E., Lee, Y., Kim, Y., and Lee, C. J. (2008). Cholinergic modulation of neural activity in the telencephalon of the zebrafish. Neurosci. Lett. 439, 79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.04.064

Pepeu, G., and Giovannini, M. G. (2017). The fate of the brain cholinergic neurons in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res. 1670, 173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.06.023

Qiu, Y., Wu, X. J., and Chen, H. Z. (2003). Simultaneous changes in secretory amyloid precursor protein and β-amyloid peptide release from rat hippocampus by activation of muscarinic receptors. Neurosci. Lett. 27, 41–44. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)01007-3

Rodríguez-Expósito, B., Gómez, A., Martín-Monzón, I., Reiriz, M., Rodríguez, F., and Salas, C. (2017). Goldfish hippocampal pallim is essential to associate temporally discontiguous events. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 139, 128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2017.01.002

Rogers, J. L., and Kesner, R. P. (2004). Cholinergic modulation of the hippocampus during encoding and retrieval of tone/shock-induced fear conditioning. Learn. Mem. 11, 102–107. doi: 10.1101/lm.64604

Rosenblum, K., Futter, M., Jones, M., Hulme, E. C., and Bliss, T. V. P. (2000). ERKI/II regulation by the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in neurons. J. Neurosci. 20, 977–985. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.20-03-00977.2000

Salah-Uddin, H., Thomas, D. R., Davies, C. H., Hagan, J. J., Wood, M. D., Watson, J. M., et al. (2008). Pharmacological asessment of m1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-gq/11 protein coupling in membranes prepared from postmortem human brain tissue. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 325, 869–874. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.137968

Santana, S., Rico, E. P., and Burgos, J. S. (2012). Can zebrafish be used as an animal model to study Alzheimer’s disease? Am. J. Neurodegener. Dis. 1, 32–48.

Scheiderer, C. L., McCutchen, E., Thacker, E. E., Kolasa, K., Ward, M. K., Parsons, D., et al. (2006). Sympathetic sprouting drives hippocampal cholinergic reinnervation that prevents loss of a muscarinic receptor-dependent long-term depression at CA3-CA1 synapses. J. Neurosci. 26, 3745–3756. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.5507-05.2006

Scheiderer, C. L., Smith, C. C., McCutchen, E., McCoy, P. A., Thacker, E. E., Kolasa, K., et al. (2008). Coactivation of M(1) muscarinic and alpha1 adrenergic receptors stimulates extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase and induces long-term depression at CA3-CA1 synapses in rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 28, 5350–5358. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.5058-06.2008

Serenó, L., Coma, M., Rodríguez, M., Sánchez-Ferrer, P., Sánchez, M. B., Gich, I., et al. (2009). A novel GSK-3β inhibitor reduces Alzheimer’s pathology and rescues neuronal loss in vivo. Neurobiol. Dis. 35, 359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.05.025

Tagliavini, F., Pilleri, G., Bouras, C., and Constantinidis, J. (1984). The basal nucleus of Meynert in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurosci. Lett. 44, 37–42. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90217-9

Terry, A. V. Jr. (2008). Role of the central cholinergic system in the therapeutics of schizophrenia. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 6, 286–292. doi: 10.2174/157015908785777247

Whitehouse, P. J., Struble, R. G., Hedreen, J. C., Clark, A. W., White, C. L., Parhad, I. M., et al. (1983). Neuroanatomical evidence for a cholinergic deficit in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 19, 437–440.

Williams, F. E., and Messer, W. S. Jr. (2004). Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain of the zebrafish (Danio rerio) measured by radioligand binding techniques. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 137, 349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2004.03.002

Wirths, O. (2017). Preparation of crude synaptosomal fractions from mouse brains and spinal cords. Bio Protoc. 7:e2423. doi: 10.21769/bioprotoc.2423

Wu, Y., Chen, Y., Tang, T., Ng, M., Amstislavskaya, T. G., Tikhonova, M. A., et al. (2017). Unilateral stimulation of the lateral division of the dorsal telencephalon induces synaptic plasticity in the bilateral medial division of zebrafish. Sci. Rep. 7:9096. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08093-9

Yates, C. M., Simpson, J., Maloney, A. F., Gordon, A., and Reid, A. H. (1980). Alzheimer-like cholinergic deficiency in down syndrome. Lancet 2:979. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92137-6

Xi, Y., Noble, S., and Ekker, M. (2011). Modeling neurodegeneration in zebrafish. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 11, 274–282. doi: 10.1007/s11910-011-0182-2

Keywords: acetylcholine receptor (AChR), glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3β, extracellular signal-regulate kinase (ERK1/2), telencephalon, cholinergic, zebrafish

Citation: Mans RA, Hinton KD, Payne CH, Powers GE, Scheuermann NL and Saint-Jean M (2019) Cholinergic Stimulation of the Adult Zebrafish Brain Induces Phosphorylation of Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 β and Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase in the Telencephalon. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 12:91. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00091

Received: 31 December 2018; Accepted: 25 March 2019;

Published: 16 April 2019.

Edited by:

Hermona Soreq, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, IsraelReviewed by:

Sebastian Lobentanzer, Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main, GermanyDeborah Toiber, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel

Copyright © 2019 Mans, Hinton, Payne, Powers, Scheuermann and Saint-Jean. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Robert A. Mans, cm1hbnNAZ2VvcmdpYXNvdXRoZXJuLmVkdQ==

Robert A. Mans

Robert A. Mans Kyle D. Hinton

Kyle D. Hinton Cicely H. Payne

Cicely H. Payne