- 1Department of Neurology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Madison, WI, USA

- 2Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, State University of New York Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA

- 3Department of Neuroscience, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA

- 4Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Madison, WI, USA

Amyloid-beta protein precursor (APP) and metabolite levels are altered in fragile X syndrome (FXS) patients and in the mouse model of the disorder, Fmr1KO mice. Normalization of APP levels in Fmr1KO mice (Fmr1KO/APPHET mice) rescues many disease phenotypes. Thus, APP is a potential biomarker as well as therapeutic target for FXS. Hyperexcitability is a key phenotype of FXS. Herein, we determine the effects of APP levels on hyperexcitability in Fmr1KO brain slices. Fmr1KO/APPHET slices exhibit complete rescue of UP states in a neocortical hyperexcitability model and reduced duration of ictal discharges in a CA3 hippocampal model. These data demonstrate that APP plays a pivotal role in maintaining an appropriate balance of excitation and inhibition (E/I) in neural circuits. A model is proposed whereby APP acts as a rheostat in a molecular circuit that modulates hyperexcitability through mGluR5 and FMRP. Both over- and under-expression of APP in the context of the Fmr1KO increases seizure propensity suggesting that an APP rheostat maintains appropriate E/I levels but is overloaded by mGluR5-mediated excitation in the absence of FMRP. These findings are discussed in relation to novel treatment approaches to restore APP homeostasis in FXS.

Introduction

Amyloid-beta protein precursor (APP) levels are dysregulated in numerous neurological disorders that are comorbid with a seizure phenotype including fragile X syndrome (FXS) (Westmark, 2013). FXS is a trinucleotide repeat disorder caused by a CGG repeat expansion at the 5′-end of the FMR1 gene. Hypermethylation of the repeat expansion results in transcriptional silencing of the FMR1 gene and loss of expression of fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) (Jin and Warren, 2000). FMRP is an RNA binding protein (RBP) that plays a pivotal role in synaptic function. It is one of numerous RBP that interact with amyloid precursor protein (App) mRNA to regulate post-transcriptional and/or translational events involved in the synthesis of APP (Westmark and Malter, 2012). Specifically, FMRP binds to a guanine-rich region in the coding region of App mRNA and regulates APP translation through a metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5)-dependent pathway (Westmark and Malter, 2007). We hypothesize that altered expression of APP in FXS contributes to disease severity. In support of this hypothesis, genetic knockout of one App allele in Fmr1KO mice (Fmr1KO/APPHET mice) reduces APP expression in the Fmr1KO to wild type (WT) levels and rescues audiogenic-induced seizures (AGS), the percentage of mature spines, open field and marble burying behavioral phenotypes, and mGluR-LTD (Westmark et al., 2011). APP and metabolite levels are altered in Fmr1KO mice and FXS patients (Sokol et al., 2006; Westmark et al., 2011; Erickson et al., 2014; Pasciuto et al., 2015; Ray et al., 2016). Thus, APP is a potential therapeutic target as well as blood-based biomarker for FXS (Berry-Kravis et al., 2013; Westmark et al., 2016), and it is of interest to determine the effect(s) of APP levels on additional disease phenotypes. Herein, we ascertain the effects of App knockdown on hyperexcitability in the Fmr1KO mouse.

Genetic Reduction of App Rescues Hyperexcitability in Fmr1KO Mice

The psychiatric phenotype of FXS includes hyperexcitability traits such as tactile defensiveness, attention deficits, hyperactivity, and hyperarousal to sensory stimulation (Tranfaglia, 2011). There is high comorbidity of epilepsy in FXS with electroencephalogram (EEG) patterns most often consisting of a centrotemporal spike pattern resembling Benign Focal Epilepsy of Childhood (BFEC) (Berry-Kravis, 2002). Hyperexcitability can be modeled in the Fmr1KO mice both in vivo and in vitro (brain slices). In vivo, the Fmr1KO mice are susceptible to AGS (Chen and Toth, 2001). In the AGS model, mice are exposed to 110 dB siren, which elicits out-of-control (wild) running and jumping followed by convulsive seizures and often death. There is substantial evidence that dysregulated APP expression alters seizure propensity. AGS are exacerbated by overexpression of APP in the Fmr1KO mouse (FRAXAD mice) and partially rescued by reduced expression of APP in Fmr1KO/APPHET mice (Westmark et al., 2010, 2011). Alzheimer's disease (Tg2576) and Down syndrome (Ts65Dn) mice, which overexpress human and mouse APP respectively, are highly susceptible to AGS (Westmark et al., 2010). Numerous mouse models that express altered APP or metabolite levels exhibit elevated rates of spontaneous or provoked seizures (Moechars et al., 1996; Steinbach et al., 1998; Del Vecchio et al., 2004; Lalonde et al., 2005; Palop et al., 2007; Kobayashi et al., 2008; Westmark et al., 2008; Minkeviciene et al., 2009; Ziyatdinova et al., 2011; Sanchez et al., 2012) while suppression of transgenic APP in Alzheimer's disease mice during postnatal development delays the onset of EEG abnormalities (Born et al., 2014).

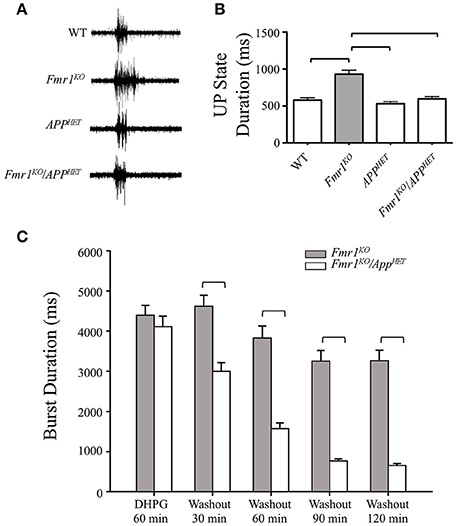

In brain slices, hyperexcitability can be measured by recording UP states and epileptiform discharges. UP states are short periods of local network activity that generate a steady-state level of depolarization and synchronous firing among groups of neighboring neurons (Gibson et al., 2008). Fmr1KO mice exhibit an increased duration of the UP state, consistent with network hyperexcitability (Gibson et al., 2008; Goncalves et al., 2013). Specifically, spontaneously occurring UP states are 38-67% longer in Fmr1KO than in WT slices (Hays et al., 2011). Deletion of Fmr1 selectively in excitatory neurons mimics the prolonged UP states whereas knockdown of mGluR5 rescues the hyperexcitability in the Fmr1KO with no effect in WT (Hays et al., 2011). To determine if hyperexcitability was rescued in Fmr1KO mice by knockdown of App, we recorded UP states in Fmr1KO/AppHET mice and littermate controls per previously described methods (Gibson et al., 2008). Briefly, Fmr1HET/AppHET females were bred with AppHET males to generate WT, Fmr1KO, AppHET and Fmr1KO/AppHET male littermates. Thalamocortical slices (400 μm) from postnatal day 24–28 (P24-P28) males were transected parallel to the pia mater to remove the thalamus and midbrain, and spontaneously generated UP states were recorded in layer 4 of the somatosensory cortex. The increased duration of the UP states observed in the Fmr1KO was completely rescued in Fmr1KO/APPHET mice (Figures 1A,B) where UP state duration decreased from 931 ± 55 milliseconds (ms) in Fmr1KO to 597 ± 30 ms in Fmr1KO/APPHET, (p < 0.001). UP state duration was not significantly different between APPHET and WT slices suggesting that rescue was not a consequence of a general reduction in excitability due to lower APP levels.

Figure 1. Rescue of hyperexcitability in Fmr1KO mice by genetic manipulation of APP. Thalamocortical slices from WT (n = 17), Fmr1KO (n = 22), AppHET (n = 13), and Fmr1KO/AppHET (n = 13) male mice were assessed for neocortical hyperexcitability. (A) Trace recordings and (B) histogram depicting a significant increase in UP state activity in Fmr1KO slices compared to WT, which was completely rescued in the Fmr1KO/AppHET. Error bars represent SEM. Horizontal bars denote statistically different levels by one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni's multiple comparison test (P < 0.0001). DHPG-induced prolonged epileptiform discharges were assessed in hippocampal slices from Fmr1KO and Fmr1KO/AppHET male mice (n = 6 mice per cohort). The recordings were continuous for 3 or more hours in a single slice per animal. (C) Summary frequency histogram of synchronized epileptiform discharges from Fmr1KO and Fmr1KO/AppHET slices in the presence of DHPG (60 min) and after DHPG washout at the indicated times up to 2 h. The mean durations of epileptiform discharges in Fmr1KO/AppHET slices at 30, 60, 90, and 120 min after DHPG washout are significantly shorter than those in Fmr1KO for all times tested (P < 0.001).

Hyperexcitability can also be evaluated in slices of the CA3 region of the hippocampus in Fmr1KO mice. Prolonged epileptic bursts can be induced by group 1 mGluR agonists in both WT and Fmr1KO mice and with a GABAergic antagonist only in Fmr1KO (Chuang et al., 2005; Zhong et al., 2009). In WT slices, DHPG elicits short (~500 ms) synchronized discharges that gradually extend to reach an average duration of 4.4 ± 0.14 s at 60 min; and in untreated Fmr1KO slices, bicuculline elicits short <1 ms synchronized discharges that progressively increase in duration over 60 min (average duration 2.3 ïĆś 0.13 s) (Osterweil et al., 2013). These prolonged epileptiform discharges resemble the ictal discharges observed in the CA3 region in epilepsy (Merlin and Wong, 1997; Wong et al., 2004). The number and duration of ictal-like discharges were assessed by intracellular CA3 recordings in juvenile Fmr1KO and Fmr1KO/AppHET slices in the presence of DHPG (60 min) and after DHPG washout for up to 2 h as previously described (Chuang et al., 2005) (Figure 1C, Supplementary Figure 1). In the presence of DHPG, a distinct population of ictal-like discharges (burst duration > 1500 ms) occurred in both Fmr1KO and Fmr1KO/AppHET slices. After DHPG washout, the ictal-like discharges remained distinct for the duration of the recording (up to 2 h post-DHPG washout) in the Fmr1KO, but not in the Fmr1KO/AppHET slices. Thus, a major difference between Fmr1KO and Fmr1KO/AppHET slices is that while ictal-like discharges were transiently expressed in both genotypes, they were not maintained in the Fmr1KO/AppHET upon termination of receptor stimulation. The seizure activity modeled in the hippocampal slice paradigm is congruent with the AGS phenotype observed in Fmr1KO/AppHET mice where wild running and seizures are attenuated but not completely rescued to WT levels (Westmark et al., 2011). The two critical components of plasticity include the initiating factors required for induction of the modification and the downstream effectors that maintain expression of the enhanced response (Bianchi et al., 2012). Our data suggest that genetic reduction of App in the Fmr1KO background does not prevent the induction of seizure activity, but can attenuate progression; thus, APP appears to be a downstream effector that maintains hyperexcitability in the context of the Fmr1KO.

The complete rescue of hyperexcitability in the neocortex compared to the partial rescue in the hippocampus in the Fmr1KO/AppHET mice is in accord with studies in immature mice demonstrating that the hippocampus has a lower seizure threshold compared to neocortex (Abdelmalik et al., 2005). This could be due differential expression and/or activity of group 1 mGluRs (mGluR1 and mGluR5) in the respective neurons under study. In fast spiking inhibitory neurons (neocortical slice model), mGluR1 is more highly expressed than mGluR5 (Sun et al., 2009); however reduced expression of mGluR5 or APP in the Fmr1KO completely rescues neocortical hyperexcitability whereas UP states are still longer in the Fmr1KO after treatment with the mGluR1 inhibitor LY367385 (Hays et al., 2011). These data suggest that mGluR5 is the critical group 1 mGluR that modulates Fmr1-dependent hyperexcitability in the neocortex. Alternatively, in CA3 hippocampal neurons, both group 1 mGluR subtypes are involved in the induction and maintenance of mGluR-mediated bursts, but mGluR5 plays a greater role in the induction and mGluR1 in the maintenance of the prolonged epileptic bursts (Merlin, 2002). As burst duration but not induction are rescued in the Fmr1KO/APPHET, these data suggest that the hyperexcitability elicited by elevated APP expression in the Fmr1KO CA3 region is dependent on mGluR1.

Synaptic dysfunction occurs when the appropriate balance of excitation and inhibition (E/I) in neural circuits is not maintained (Gatto and Broadie, 2010). The absence of FMRP during postnatal development results in an E/I imbalance dominated by excitation. Our results demonstrate that E/I balance is predominantly restored when APP expression is reduced to WT levels in the Fmr1KO. Thus, APP plays a critical role in modulating excitability. The other half of E/I balance is the inhibitory feedback on circuits. FMRP normally binds to multiple GABAAR mRNAs, and their expression is decreased in juvenile Fmr1KO (Braat et al., 2015) resulting in delay of the developmental GABA switch in Fmr1KO (He et al., 2014). Selective deletion of Fmr1 in inhibitory neurons has no effect on prolonged UP states suggesting that impaired GABAAR signaling in FXS does not account for increased hyperexcitability in the neocortex (Hays et al., 2011). Conversely, a competitive antagonist of GABAAR, bicuculline, elicits epileptiform discharges in the CA3 region of the hippocampus (Osterweil et al., 2013). These findings suggest that inhibitory feedback is differentially regulated in the neocortex and hippocampus in Fmr1KO. Overall, the neocortical hyperexcitability and hippocampal epileptiform discharge slice models share the features of prolonged activity states and dependence on mGluR5, FMRP, and APP, but differ in induction mode (neocortical slices exhibit baseline excitation vs. hippocampal slices require pharmacological stimulation), inhibitory feedback (hippocampal slices are dependent of GABAAR), and protein synthesis requirements (CA3 bursts require extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 activation and new protein synthesis) (Zhao et al., 2004; Chuang et al., 2005; Hays et al., 2011).

A Model for an APP-Induced Short Circuit in Fragile X

Regarding possible mechanisms for APP-mediated hyperexcitability, (Westmark, 2013) APP or a metabolite could interfere with cell surface receptor activation. For example, Aβ oligomers cause redistribution of mGluR5to synapses (Renner et al., 2010) and trigger multiple distinct signaling events through mGluR5/prion protein complexes (Um et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2014; Haas and Strittmatter, 2016). In neurons that overexpress APP, Aβ depresses excitatory synaptic transmission (Kamenetz et al., 2003). In Fmr1KO mice, Aβ levels are elevated in older mice but reduced in juvenile mice compared to WT controls (Westmark et al., 2011; Pasciuto et al., 2015). Thus, increased α-secretase and/or decreased BACE1 processing during postnatal development could result in decreased Aβ levels and increased synaptic transmission (Jin and Warren, 2000) Altered APP expression could affect scaffolding protein interactions at the postsynaptic density. For example, APP co-immunoprecipitates with Homer2 and Homer3 (Parisiadou et al., 2008). These scaffolding proteins inhibit APP processing, reduce cell surface APP expression, and prevent maturation of BACE1 (Parisiadou et al., 2008). Uncoupled Homer1-mGluR5 interactions underlie Fmr1KO phenotypes, and genetic deletion of Homer1a rescues prolonged UP states in Fmr1KO mice similar to the complete rescue observed herein in the Fmr1KO/APPHET mice (Ronesi et al., 2012). APP does not co-immunoprecipitate with Homer1 (Parisiadou et al., 2008); however, Aβ induces disassembly of Homer1b and Shank1 clusters (Roselli et al., 2009). (Westmark and Malter, 2012) APP or metabolites could alter the activity of intracellular signaling pathways such as ERK and mTOR (Young et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2010; Caccamo et al., 2011; Chasseigneaux et al., 2011; Pasciuto et al., 2015). Both of these pathways play pivotal roles in FXS pathology (Osterweil et al., 2010; Hoeffer et al., 2012). And Westmark and Malter (2007) APP metabolites could function in feedback loops to regulate the aforementioned pathways or even the transcription of the APP and APP processing enzymes. Aβ binds to the promoter regions of the APP and BACE1 genes and may function as a transcription factor to regulate its own production and/or processing (Bailey et al., 2011). Thus, there are numerous molecular junctures where altered expression of APP or metabolites could interfere with synaptic function and lead to a hyperexcitable circuit.

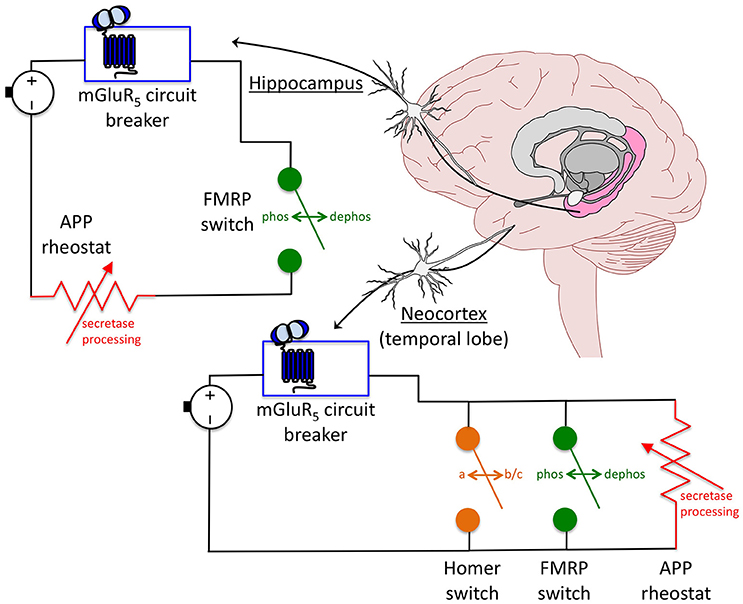

Overall, these data suggest a model whereby mGluR5 inhibitors act as a circuit breaker, FMRP as an automatic transfer switch and APP as a rheostat in a circuit that controls hyperexcitability (Figure 2). The mGluR5 circuit breaker: Genetic reduction of mGluR5 in the Fmr1KO mouse rescues plasticity (ocular dominance plasticity, neocortical hyperexcitability), dendritic spines (density on cortical pyramidal neurons), protein synthesis, behavior (inhibitory avoidance extinction), and AGS (Dolen et al., 2007; Hays et al., 2011). Pharmaceutical inhibition of mGluR5 likewise rescues numerous Fmr1KO phenotypes (Michalon et al., 2012, 2014). Thus, inhibiting mGluR5 appears to break a circuit that mediates hyperexcitability in the Fmr1KO mouse. The FMRP automatic transfer switch: mGluR5 activation causes a rapid dephosphorylation of FMRP, which permits protein synthesis (Ceman et al., 2003; Narayanan et al., 2007), as well as a biphasic change in FMRP levels (initial decrease followed by increase) (Zhao et al., 2011). Thus, FMRP appears to function as an automatic transfer switch downstream of mGluR5 to control protein synthesis in response to receptor activation. In FXS models, loss of the FMRP switch that modulates mGluR5 signaling permits a constitutively-on circuit. The APP rheostat: Born and colleagues demonstrated that juvenile overexpression of APP contributes to sharp wave EEG discharges in APP transgenic mice, and proposed that APP expression functions as a rheostat that regulates synaptic balance in the brain (Born et al., 2014). We have observed that both over- and under-expression of APP increases seizure propensity in juvenile Fmr1KO mice suggesting that tight regulation of this protein may be necessary to mitigate hyperexcitability in FXS (Westmark et al., 2010, 2011). Genetic reduction of APP in Fmr1KO mice rescues plasticity (mGluR-LTD, neocortical hyperexcitability, epileptiform discharge duration but not induction), dendritic spines (percent mature spines but not dendritic spine length), protein synthesis, behavior (open field, marble burying), and AGS (Westmark et al., 2011; Pasciuto et al., 2015). The partial rescue of dendritic spines and epileptiform discharges in the Fmr1KO/APPHET suggests that APP is necessary but not sufficient to maintain synaptic homeostasis. Thus, in the context of WT mice, an APP variable resistor is capable of maintaining an appropriate E/I balance, but in Fmr1KO and some APP transgenic mice, excess APP appears to cause a short circuit through overload of the APP rheostat resulting in hyperexcitability. Likewise, complete loss of APP would bypass the APP rheostat. Fmr1KO/AppKO mice exhibit an extremely strong AGS phenotype (97%, n = 36 mice) (Westmark et al., 2013a), which is not observed in AppKO mice (11%, n = 36 mice). These data suggest that exacerbated hyperexcitability is a result of the combined loss of both FMRP and APP.

Figure 2. Model for an APP-induced short circuit in FXS. APP acts as a rheostat (i.e., variable resistor, dimmer switch) in a circuit where mGluR5 inhibitors are a circuit breaker and FMRP is an automatic transfer switch that regulate neuronal excitability. The FMRP switch is dependent on a rapid dephosphorylation reaction in response to mGluR5 activation. In the absence of FMRP, the circuit is constitutively on. In the presence of mGluR5 inhibitors, the circuit is shut down. The downstream APP circuitry appears to be wired differently dependent on brain region. In the neocortex, knockdown of individual proteins including mGluR5, Homer and APP completely rescues excitability levels suggesting that these components are arranged in a parallel circuit whereby there is more than one continuous signaling pathway between mGluR5 activation and excitability output. Rescue of any one of the parallel components is sufficient to restore synaptic homeostasis. In the hippocampus, ictal burst duration, but not induction, is rescued in Fmr1KO/AppHET slices in response to DHPG treatment. This incomplete rescue suggests that APP and FMRP are wired in series downstream of mGluR5, and that the APP rheostat is overloaded in the absence of FMRP resulting in a short circuit. This model has important implications for therapeutic development and suggests that APP should be considered as a drug target for FXS as part of a multi-drug therapeutic strategy.

APP and metabolites play key roles in regulating synaptic activity with both Aβ and sAPPα implicated in positive feedback loops that facilitate mGluR5 signaling (Casley et al., 2009; Renner et al., 2010; Ferreira and Klein, 2011; Westmark et al., 2011, 2013b; Pasciuto et al., 2015). Thus, the APP rheostat may provide a graded response to mGluR5 activation through feedback loops involving amyloidogenic and non-amyloidogenic secretase processing. We found that AGS are attenuated in Fmr1KO mice with BACE1 inhibitor treatment (Supplementary Figure 2). Prox and colleagues found that seizures are increased in the ADAM10 conditional knockout mouse (loss of α-secretase processing) (Prox et al., 2013). The effect of sAPPα overexpression on hyperexcitability, which could be studied in TgAPPα (Bailey et al., 2013) and TgAPPα/Fmr1KO mice, remains to be determined. Thus, multiple APP fragments may play roles in hyperexcitability and seizure susceptibility. A caveat to this model is that over-expression of APP alone is not sufficient to increase seizure propensity in either WT or Fmr1KO mice. We tested seizures in two alternative Alzheimer's disease mouse models, R1.40 and J20, which exhibit elevated APP expression (Lamb et al., 1997; Mucke et al., 2000). Neither strain exhibited a strong AGS phenotype (Supplementary Figures 3, 4) in contrast to Tg2576 and Ts65Dn (Westmark et al., 2010). A genetic cross of J20 with Fmr1KO mice that produced mice over-expressing human APP in the context of the Fmr1KO background did not result in exacerbated AGS rates in comparison to Fmr1KO unlike the FRAXAD mice (cross of Tg2576 with Fmr1KO) (Westmark et al., 2010). The inclusion of flanking sequences in the transgenic constructs used for the R1.40 and J20 mice are expected to affect posttranscriptional regulation of the APP gene, which could alter the temporal and spatial expression of APP and metabolites and thus their contribution to seizure threshold. Of note, Fmr1HET/J20 female mice exhibited a 50% wild running rate, which was significantly higher than WT, Fmr1HET and J20 controls, supporting the assertion that APP works in synergy with FMRP to regulate hyperexcitability (Supplementary Figure 4). This synergistic effect is also observed in mGluR-LTD studies where loss of FMRP and APP modulate synaptic transmission in opposite directions (Westmark et al., 2011). The Fmr1KO/APPHET mice used herein were a constitutive App knockdown. It remains to be determined how conditional knockdown of App during development affects Fmr1 phenotypes.

Relevance to Therapeutic Development

All major Fmr1KO phenotypes can be corrected by inhibition or knockdown of mGluR5 in mice; however, neural circuitry is likely more complicated in humans and it may be necessary to employ pharmaceutical cocktails for disease treatment. Drugs under study for FXS such as acamprosate, AFQ056, donepezil, ganaxolone, lithium, lovastatin, memantine, minocycline and sertraline exhibit on- and/or off-site effects that are expected to modulate APP, Aβ, BACE1, and/or ADAM10 (Westmark et al., 2013b). Targeting APP and metabolites in FXS may allow fine tuning of excitability levels as part of a multi-drug therapeutic approach. Both amyloidogenic and non-amyloidogenic therapies have been proposed to treat FXS (Westmark et al., 2013b; Pasciuto et al., 2015). Both amyloidogenic (Aβ1−42) and non-amyloidogenic (sAPPα) metabolites of APP stimulate phosphorylation of ERK and modulate synthesis of multiple synaptic proteins predicted to be regulated through mGluR5/FMRP and to contribute to altered synaptic plasticity (Westmark et al., 2011; Pasciuto et al., 2015). Thus, it may be necessary to simultaneously modulate both α- and β-secretase processing to attain homeostatic levels of APP metabolites and rescue hyperexcitability in FXS.

Author Contributions

CW, JG, KH, RW conceived and designed the experiments. CW, SC, SH, MF, BR, PW acquired data. CW, SC, SH, JG, KH, RW interpreted data. CW drafted the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by FRAXA Research Foundation and NIH R21AG044714 (CW), and NIH 1R01HD056370 (JG).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Research Animal Resources Centers (RARC) staffs at the University of Wisconsin, the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center and the University of Texas Southwestern for expert animal care and assistance with transport between facilities. All mouse procedures were performed in accordance with NIH guidelines and approved University of Wisconsin-Madison, State University of New York Downstate Medical Center and University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center animal care protocols administered through their RARC.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnmol.2016.00147/full#supplementary-material

References

Abdelmalik, P. A., Burnham, W. M., and Carlen, P. L. (2005). Increased seizure susceptibility of the hippocampus compared with the neocortex of the immature mouse brain in vitro. Epilepsia 46, 356–366. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.34204.x

Bailey, A. R., Hou, H., Song, M., Obregon, D. F., Portis, S., Barger, S., et al. (2013). GFAP expression and social deficits in transgenic mice overexpressing human sAPPalpha. Glia 61, 1556–1569. doi: 10.1002/glia.22544

Bailey, J. A., Maloney, B., Ge, Y. W., and Lahiri, D. K. (2011). Functional activity of the novel Alzheimer's amyloid beta-peptide interacting domain (AbetaID) in the APP and BACE1 promoter sequences and implications in activating apoptotic genes and in amyloidogenesis. Gene 488, 13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.06.017

Berry-Kravis, E. (2002). Epilepsy in fragile X syndrome. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 44, 724–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2002.tb00277.x

Berry-Kravis, E., Hessl, D., Abbeduto, L., Reiss, A. L., Beckel-Mitchener, A., Urv, T. K., et al. (2013). Outcome measures for clinical trials in fragile x syndrome. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 34, 508–522. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31829d1f20

Bianchi, R., Wong, R. K. S., and Merlin, L. R. (2012). “Glutamate receptors in epilepsy: group I mGluR-mediated epileptogenesis,” in Jasper's Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies, 4th Edn., eds J. L. Noebels, M. Avoli, M. A. Rogawski, R. W. Olsen, and A. V. Delgado-Escueta (Bethesda, MD: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/med/9780199746545.003.0011

Born, H. A., Kim, J. Y., Savjani, R. R., Das, P., Dabaghian, Y. A., Guo, Q., et al. (2014). Genetic suppression of transgenic APP rescues Hypersynchronous network activity in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 34, 3826–3840. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5171-13.2014

Braat, S., D'Hulst, C., Heulens, I., De Rubeis, S., Mientjes, E., Nelson, D. L., et al. (2015). The GABAA receptor is an FMRP target with therapeutic potential in fragile X syndrome. Cell Cycle 14, 2985–2995. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.989114

Caccamo, A., Maldonado, M. A., Majumder, S., Medina, D. X., Holbein, W., Magri, A., et al. (2011). Naturally secreted amyloid-beta increases mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activity via a PRAS40-mediated mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 8924–8932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.180638

Casley, C. S., Lakics, V., Lee, H. G., Broad, L. M., Day, T. A., Cluett, T., et al. (2009). Up-regulation of astrocyte metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 by amyloid-β peptide. Brain Res. 1260, 65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.12.082

Ceman, S., O'Donnell, W. T., Reed, M., Patton, S., Pohl, J., and Warren, S. T. (2003). Phosphorylation influences the translation state of FMRP-associated polyribosomes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 3295–3305. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg350

Chasseigneaux, S., Dinc, L., Rose, C., Chabret, C., Coulpier, F., Topilko, P., et al. (2011). Secreted amyloid precursor protein beta and secreted amyloid precursor protein alpha induce axon outgrowth in vitro through Egr1 signaling pathway. PLoS ONE 6:e16301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016301

Chen, L., and Toth, M. (2001). Fragile X mice develop sensory hyperreactivity to auditory stimuli. Neuroscience 103, 1043–1050. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00036-7

Chuang, S. C., Zhao, W., Bauchwitz, R., Yan, Q., Bianchi, R., and Wong, R. K. (2005). Prolonged epileptiform discharges induced by altered group I metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated synaptic responses in hippocampal slices of a fragile X mouse model. J. Neurosci. 25, 8048–8055. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1777-05.2005

Del Vecchio, R. A., Gold, L. H., Novick, S. J., Wong, G., and Hyde, L. A. (2004). Increased seizure threshold and severity in young transgenic CRND8 mice. Neurosci. Lett. 367, 164–167. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.05.107

Dolen, G., Osterweil, E., Rao, B. S., Smith, G. B., Auerbach, B. D., Chattarji, S., et al. (2007). Correction of Fragile X Syndrome in Mice. Neuron 56, 955–962. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.001

Erickson, C. A., Ray, B., Maloney, B., Wink, L. K., Bowers, K., Schaefer, T. L., et al. (2014). Impact of acamprosate on plasma amyloid-beta precursor protein in youth: a pilot analysis in fragile X syndrome-associated and idiopathic autism spectrum disorder suggests a pharmacodynamic protein marker. J. Psychiatr. Res. 59, 220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.07.011

Ferreira, S. T., and Klein, W. L. (2011). The Abeta oligomer hypothesis for synapse failure and memory loss in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 96, 529–543. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.08.003

Gatto, C. L., and Broadie, K. (2010). Genetic controls balancing excitatory and inhibitory synaptogenesis in neurodevelopmental disorder models. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2:4. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2010.00004

Gibson, J. R., Bartley, A. F., Hays, S. A., and Huber, K. M. (2008). Imbalance of neocortical excitation and inhibition and altered UP states reflect network hyperexcitability in the mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J. Neurophysiol. 100, 2615–2626. doi: 10.1152/jn.90752.2008

Goncalves, J. T., Anstey, J. E., Golshani, P., and Portera-Cailliau, C. (2013). Circuit level defects in the developing neocortex of Fragile X mice. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 903–909. doi: 10.1038/nn.3415

Haas, L. T., and Strittmatter, S. M. (2016). Oligomers of amyloid beta prevent physiological activation of the cellular prion protein-metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 complex by glutamate in Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 17112–17121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.720664

Hays, S. A., Huber, K. M., and Gibson, J. R. (2011). Altered neocortical rhythmic activity states in Fmr1 KO mice are due to enhanced mGluR5 signaling and involve changes in excitatory circuitry. J. Neurosci. 31, 14223–14234. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3157-11.2011

He, Q., Nomura, T., Xu, J., and Contractor, A. (2014). The developmental switch in GABA polarity is delayed in fragile X mice. J. Neurosci. 34, 446–450. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4447-13.2014

Hoeffer, C. A., Sanchez, E., Hagerman, R. J., Mu, Y., Nguyen, D. V., Wong, H., et al. (2012). Altered mTOR signaling and enhanced CYFIP2 expression levels in subjects with fragile X syndrome. Genes Brain Behav. 11, 332–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2012.00768.x

Hu, N. W., Nicoll, A. J., Zhang, D., Mably, A. J., O'Malley, T., Purro, S. A., et al. (2014). mGlu5 receptors and cellular prion protein mediate amyloid-beta-facilitated synaptic long-term depression in vivo. Nat. Commun. 5:3374. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4374

Jin, P., and Warren, S. T. (2000). Understanding the molecular basis of fragile X syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 901–908. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.6.901

Kamenetz, F., Tomita, T., Hsieh, H., Seabrook, G., Borchelt, D., Iwatsubo, T., et al. (2003). APP processing and synaptic function. Neuron 37, 925–937. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00124-7

Kobayashi, D., Zeller, M., Cole, T., Buttini, M., McConlogue, L., Sinha, S., et al. (2008). BACE1 gene deletion: impact on behavioral function in a model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 29, 861–873. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.01.002

Lalonde, R., Dumont, M., Staufenbiel, M., and Strazielle, C. (2005). Neurobehavioral characterization of APP23 transgenic mice with the SHIRPA primary screen. Behav. Brain Res. 157, 91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.06.020

Lamb, B. T., Call, L. M., Slunt, H. H., Bardel, K. A., Lawler, A. M., Eckman, C. B., et al. (1997). Altered metabolism of familial Alzheimer's disease-linked amyloid precursor protein variants in yeast artificial chromosome transgenic mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6, 1535–1541. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.9.1535

Ma, T., Hoeffer, C. A., Capetillo-Zarate, E., Yu, F., Wong, H., Lin, M. T., et al. (2010). Dysregulation of the mTOR pathway mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. PLoS ONE 5:e12845. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012845

Merlin, L. R. (2002). Differential roles for mGluR1 and mGluR5 in the persistent prolongation of epileptiform bursts. J. Neurophysiol. 87, 621–625.

Merlin, L. R., and Wong, R. K. (1997). Role of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors in the patterning of epileptiform activities in vitro. J. Neurophysiol. 78, 539–544.

Michalon, A., Bruns, A., Risterucci, C., Honer, M., Ballard, T. M., Ozmen, L., et al. (2014). Chronic metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 inhibition corrects local alterations of brain activity and improves cognitive performance in fragile X mice. Biol. Psychiatry 75, 189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.038

Michalon, A., Sidorov, M., Ballard, T. M., Ozmen, L., Spooren, W., Wettstein, J. G., et al. (2012). Chronic pharmacological mGlu5 inhibition corrects fragile X in adult mice. Neuron 74, 49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.009

Minkeviciene, R., Rheims, S., Dobszay, M. B., Zilberter, M., Hartikainen, J., Fülöp, L., et al. (2009). Amyloid beta-induced neuronal hyperexcitability triggers progressive epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 29, 3453–3462. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5215-08.2009

Moechars, D., Lorent, K., De Strooper, B., Dewachter, I., and Van Leuven, F. (1996). Expression in brain of amyloid precursor protein mutated in the alpha-secretase site causes disturbed behavior, neuronal degeneration and premature death in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 15, 1265–1274.

Mucke, L., Masliah, E., Yu, G. Q., Mallory, M., Rockenstein, E. M., Tatsuno, G., et al. (2000). High-level neuronal expression of Abeta 1-42 in wild-type human amyloid protein precursor transgenic mice: synaptotoxicity without plaque formation. J. Neurosci. 20, 4050–4058.

Narayanan, U., Nalavadi, V., Nakamoto, M., Pallas, D. C., Ceman, S., Bassell, G. J., et al. (2007). FMRP phosphorylation reveals an immediate-early signaling pathway triggered by group I mGluR and mediated by PP2A. J. Neurosci. 27, 14349–14357. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2969-07.2007

Osterweil, E. K., Chuang, S. C., Chubykin, A. A., Sidorov, M., Bianchi, R., Wong, R. K., et al. (2013). Lovastatin corrects excess protein synthesis and prevents epileptogenesis in a mouse model of fragile x syndrome. Neuron 77, 243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.01.034

Osterweil, E. K., Krueger, D. D., Reinhold, K., and Bear, M. F. (2010). Hypersensitivity to mGluR5 and ERK1/2 leads to excessive protein synthesis in the hippocampus of a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J. Neurosci. 30, 15616–15627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3888-10.2010

Palop, J. J., Chin, J., Roberson, E. D., Wang, J., Thwin, M. T., Bien-Ly, N., et al. (2007). Aberrant excitatory neuronal activity and compensatory remodeling of inhibitory hippocampal circuits in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 55, 697–711. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.025

Parisiadou, L., Bethani, I., Michaki, V., Krousti, K., Rapti, G., and Efthimiopoulos, S. (2008). Homer2 and Homer3 interact with amyloid precursor protein and inhibit Abeta production. Neurobiol. Dis. 30, 353–364. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.02.004

Pasciuto, E., Ahmed, T., Wahle, T., Gardoni, F., D'Andrea, L., Pacini, L., et al. (2015). Dysregulated ADAM10-mediated processing of APP during a critical time window leads to synaptic deficits in fragile X syndrome. Neuron 87, 382–398. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.032

Prox, J., Bernreuther, C., Altmeppen, H., Grendel, J., Glatzel, M., D'Hooge, R., et al. (2013). Postnatal disruption of the disintegrin/metalloproteinase ADAM10 in brain causes epileptic seizures, learning deficits, altered spine morphology, and defective synaptic functions. J. Neurosci. 33, 12915–12928. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.5910-12.2013

Ray, B., Sokol, D. K., Maloney, B., and Lahiri, D. K. (2016). Finding novel distinctions between the sAPPalpha-mediated anabolic biochemical pathways in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Fragile X Syndrome plasma and brain tissue. Sci. Rep. 6:26052. doi: 10.1038/srep26052

Renner, M., Lacor, P. N., Velasco, P. T., Xu, J., Contractor, A., Klein, W. L., et al. (2010). Deleterious effects of amyloid beta oligomers acting as an extracellular scaffold for mGluR5. Neuron 66, 739–754. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.029

Ronesi, J. A., Collins, K. A., Hays, S. A., Tsai, N.-P., Guo, W., Birnbaum, S. G., et al. (2012). Disrupted Homer scaffolds mediate abnormal mGluR5 function in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 431–440. doi: 10.1038/nn.3033

Roselli, F., Hutzler, P., Wegerich, Y., Livrea, P., and Almeida, O. F. (2009). Disassembly of shank and homer synaptic clusters is driven by soluble beta-amyloid(1-40) through divergent NMDAR-dependent signalling pathways. PLoS ONE 4:e6011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006011

Sanchez, P. E., Zhu, L., Verret, L., Vossel, K. A., Orr, A. G., Cirrito, J. R., et al. (2012). Levetiracetam suppresses neuronal network dysfunction and reverses synaptic and cognitive deficits in an Alzheimer's disease model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E2895–E2903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121081109

Sokol, D. K., Chen, D., Farlow, M. R., Dunn, D. W., Maloney, B., Zimmer, J. A., et al. (2006). High levels of Alzheimer beta-amyloid precursor protein (APP) in children with severely autistic behavior and aggression. J. Child Neurol. 21, 444–449.

Steinbach, J. P., Müller, U., Leist, M., Li, Z. W., Nicotera, P., and Aguzzi, A. (1998). Hypersensitivity to seizures in beta-amyloid precursor protein deficient mice. Cell Death Differ. 5, 858–866. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400391

Sun, Q. Q., Zhang, Z., Jiao, Y., Zhang, C., Szabo, G., and Erdelyi, F. (2009). Differential metabotropic glutamate receptor expression and modulation in two neocortical inhibitory networks. J. Neurophysiol. 101, 2679–2692. doi: 10.1152/jn.90566.2008

Tranfaglia, M. R. (2011). The psychiatric presentation of fragile x: evolution of the diagnosis and treatment of the psychiatric comorbidities of fragile X syndrome. Dev. Neurosci. 33, 337–348. doi: 10.1159/000329421

Um, J. W., Kaufman, A. C., Kostylev, M., Heiss, J. K., Stagi, M., Takahashi, H., et al. (2013). Metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 is a coreceptor for Alzheimer Abeta oligomer bound to cellular prion protein. Neuron 79, 887–902. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.036

Westmark, C. J. (2013). What's hAPPening at synapses? The role of amyloid β-protein precursor and beta-amyloid in neurological disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 18, 425–434. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.122

Westmark, C. J., Berry-Kravis, E. M., Ikonomidou, C., Yin, J. C., and Puglielli, L. (2013b). Developing BACE-1 inhibitors for FXS. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 7:77. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00077

Westmark, C. J., and Malter, J. S. (2007). FMRP mediates mGluR5-dependent translation of amyloid precursor protein. PLoS Biol. 5:e52. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050052

Westmark, C. J., and Malter, J. S. (2012). The regulation of AβPP expression by RNA-binding proteins. Ageing Res. Rev. 11, 450–459. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.03.005

Westmark, C. J., Sokol, D. K., Maloney, B., and Lahiri, D. K. (2016). Novel roles of amyloid-beta precursor protein metabolites in fragile X syndrome an autism. Mol. Psychiatry 21, 1333–1341. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.134

Westmark, C. J., Westmark, P. R., Beard, A. M., Hildebrandt, S. M., and Malter, J. S. (2008). Seizure susceptibility and mortality in mice that over-express amyloid precursor protein. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 1, 157–168.

Westmark, C. J., Westmark, P. R., and Malter, J. S. (2010). Alzheimer's disease and Down syndrome rodent models exhibit audiogenic seizures. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 20, 1009–1013. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100087

Westmark, C. J., Westmark, P. R., and Malter, J. S. (2013a). Soy-based diet exacerbates seizures in mouse models of neurological disease. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 33, 797–805. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121426

Westmark, C. J., Westmark, P. R., O'Riordan, K. J., Ray, B. C., Hervey, C. M., Salamat, M. S., et al. (2011). Reversal of Fragile X Phenotypes by Manipulation of AbetaPP/Abeta Levels in Fmr1 Mice. PLoS ONE 6:e26549. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026549

Wong, R. K., Chuang, S. C., and Bianchi, R. (2004). Plasticity mechanisms underlying mGluR-induced epileptogenesis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 548, 69–75. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-6376-8_5

Young, K. F., Pasternak, S. H., and Rylett, R. J. (2009). Oligomeric aggregates of amyloid beta peptide 1-42 activate ERK/MAPK in SH-SY5Y cells via the alpha7 nicotinic receptor. Neurochem. Int. 55, 796–801. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.08.002

Zhao, W., Bianchi, R., Wang, M., and Wong, R. K. (2004). Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 is required for the induction of group I metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated epileptiform discharges. J. Neurosci. 24, 76–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4515-03.2004

Zhao, W., Chuang, S. C., Bianchi, R., and Wong, R. K. (2011). Dual regulation of fragile X mental retardation protein by group I metabotropic glutamate receptors controls translation-dependent epileptogenesis in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 31, 725–734. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2915-10.2011

Zhong, J., Chuang, S. C., Bianchi, R., Zhao, W., Lee, H., Fenton, A. A., et al. (2009). BC1 regulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated neuronal excitability. J. Neurosci. 29, 9977–9986. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3893-08.2009

Ziyatdinova, S., Gurevicius, K., Kutchiashvili, N., Bolkvadze, T., Nissinen, J., Tanila, H., et al. (2011). Spontaneous epileptiform discharges in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease are suppressed by antiepileptic drugs that block sodium channels. Epilepsy Res. 94, 75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.01.003

Keywords: amyloid-beta, amyloid-beta precursor protein, fragile X mental retardation protein, fragile X syndrome, hyperexcitability

Citation: Westmark CJ, Chuang S-C, Hays SA, Filon MJ, Ray BC, Westmark PR, Gibson JR, Huber KM and Wong RKS (2016) APP Causes Hyperexcitability in Fragile X Mice. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 9:147. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00147

Received: 26 September 2016; Accepted: 01 December 2016;

Published: 15 December 2016.

Edited by:

Susan A. Masino, Trinity College, USAReviewed by:

Barbara Bardoni, CNRS UMR7275 Institut de Pharmacologie Moléculaire et Cellulaire, FranceNiraj S. Desai, University of Texas at Austin, USA

Copyright © 2016 Westmark, Chuang, Hays, Filon, Ray, Westmark, Gibson, Huber and Wong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cara J. Westmark, d2VzdG1hcmtAZmFjc3RhZmYud2lzYy5lZHU=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Cara J. Westmark

Cara J. Westmark Shih-Chieh Chuang2†

Shih-Chieh Chuang2† Seth A. Hays

Seth A. Hays Jay R. Gibson

Jay R. Gibson Kimberly M. Huber

Kimberly M. Huber