- 1Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan, China

- 2Department of Urology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, China

- 3Department of Urology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University, Jinan, China

- 4Department of Urology, Weihai Municipal Hospital, Weihai, China

- 5Department of Nephrology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University, Jinan, China

- 6Department of Nephrology, Shandong Provincial Hospital, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan, China

- 7Department of Urology, Shandong Provincial ENT Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University, Jinan, China

Kidney cancer encompasses a range of primary cancers, such as clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) and papillary renal cell carcinoma (pRCC). Our knowledge about the tumor microenvironment (TME) of kidney cancer is still limited. Therefore, we comprehensively assessed the TME of kidney cancers (including ccRCC and pRCC) using the ESTIAMTE, and CIBERSORT algorithms, and conducted distinct functional and correlation analyses with data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC), Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), Connectivity map and CellMiner database. Next, we identified two immune-related hub genes, IGLL5 and IL2RA, which play essential roles in the TME as well as on survival in ccRCC and pRCC. Furthermore, ccRCC and pRCC samples from our medical center were collected to verify the clinical application value of these two immune-related genes. A specific enrichment analysis of immune cells related to IGLL5 and IL2RA was also conducted in two types of renal cell cancer. Based on selected genes, we predicted the drug response and uncovered novel drug candidate for RCC treatment. Considering the unfavorable outcomes of kidney cancer and emerging interest in TME-targeted treatments, our results may offer insights into immune-related molecular mechanisms and possible targets to control the kidney cancer.

Introduction

Kidney or renal cancer is the sixth most common malignant cancer in men and the ninth most common in women. In 2020, it was estimated that 76,080 patients would be diagnosed with kidney cancer and 13,780 patients would die from the disease in the United States (Siegel et al., 2021). Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common form and accounts for 85% of all histological types, with ccRCC comprising 70–80% and pRCC 15–20% of all RCC (Linehan et al., 2016; Barata and Rini, 2017; Vuong et al., 2019). Although pRCC has a better prognosis than ccRCC, the overall prognosis for ccRCC and pRCC remains limited (Steffens et al., 2012). Therefore, effective therapy and accurate biomarkers need to be determined.

TME, as an integral part of tumors, is a cellular environment consisting of tumor cells and other non-malignant cells, including surrounding immune cells, lymphocytes, fibroblasts, stromal cells, and blood vessels (Wu and Dai, 2017). TME acts as a complex ecosystem, which could support tumor growth as well as metastasis while attenuating immunosurveillance. A wealth of new information has emerged which reveals how the functionality of TME determines its integral and indispensable role in various cancers (Hanahan and Coussens, 2012; Pitt et al., 2016). Within the TME, various types of immune and non-immune cell are found. Some nontumor cells, such as stromal cells, fibroblasts, may accelerate cancer cell proliferation and stimulate cancer progression (Hanahan and Coussens, 2012). However, although several immune cells, such as T cells as well as B cells also exist in TME, the exact contribution of these immune cells to the prognosis of patients is not clear (Grivennikov et al., 2010). With a variety of factors that diverse cells secrete, these lead to a chronic inflammatory, immunosuppressive environment (Osipov et al., 2019). Within that environment, cancer cells are able to adapt and grow with less possibility of detection and eradication by immunosurveillance.

Currently, RCC is considered an immunogenic and vascularized tumor. Several studies have found that immune cells could infiltrate into the TME of RCC, but these immune cells block the effective anti-tumor responses (Díaz-Montero et al., 2020). Due to the immunosuppressed state of RCC, attention has focused on immune checkpoint inhibitors. However, a large number of patients with RCC do not benefit from these immune-based treatments, and therapies are related with drug resistance because of heterogeneous and adaptive TME (Ravaud et al., 2016). In order to eradicate tumor cells, effector immune cells must be relieved from the immunosuppressive networks that constitute the TME. Moreover, with the improved understanding of interactions between immune cells, and between cancer cells and immune cells, the optimizing of our approach to treating cancers will significantly progress (Joyce and Pollard, 2009). Therefore, it is indispensable to elucidate the cross-talk process between various immune cells and the TME.

In this study, we identified the immune-related genes in the TME of ccRCC as well as pRCC, and explored their potential mechanisms, biological functions, and predict drug response as well as potential drugs for ccRCC and pRCC. These immune-genes could serve as reliable prognostic biomarkers as well as therapeutic targets.

Materials and Methods

Data Collection

The gene expression data and clinical information of ccRCC (539 ccRCC and 72 normal samples) and pRCC (289 pRCC and 32 normal samples) were downloaded directly from TCGA (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). The gene expression data and clinical information of 91 and 61 RCC samples were obtained from ICGC (https://dcc.icgc.org/) and GEO (including GSE40912 and GSE2748) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), separately. We eliminated samples in which clinical information was lost or unknown.

Identification and Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using the “limma” package and visualized using the “pheatmap” package. The |logFC| > 1, p-value < 0.05, and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 were used to screen for DEGs. The correlation between immune-related genes and clinical factors was performed using the “ggplot2” and “corrplot” package.

Functional Analysis

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network construction was performed using the STRING online database (http://string-db.org/), and the network was visualized using Cytoscape (Szklarczyk et al., 2019). Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses was conducted by “clusterProfiler” package. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed by the “gsva” R package. The Connectivity Map (Cmap) and CellMiner database were uesd to predict small molecular compounds and individual response to drugs.

Tumor Microenvironment Analysis

We used ESTIMATE algorithm (Estimation of Stromal and Immune cells in Malignant Tumor tissues using Expression data) algorithm to measure stromal and immune scores in ccRCC and pRCC with data from TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) (Yoshihara et al., 2013). The prognostic-related genes were selected after performing the Univariate Cox analysis with p < 0.1. Tumor-infiltrating immune cells were calculated by the CIBERSORT algorithm. Venn diagrams as well as violin plots were visualized with the ‘VennDiagram’ and ‘vioplot’ packages.

Immunohistochemistry

Ten pairs of ccRCC, pRCC and adjacent normal tissues were collected from Shandong provincial Hospital affiliated to Shandong First University from April 2021 to June 2021. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital (Approval no. SWYX: NO. 2021-118). IHC was performed according to previously published method (Wang et al., 2020). All samples were incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-IL2RA (ab245687) and anti-IGLL5 (NBP2-14574) antibodies overnight at 4°C and then washed. Two pathologists independently assessed the IHC slides.

Statistical Analysis

Mann-Whitney test was utilized to measure gene expression between tumor and non-tumor tissues. The Kaplan-Meier curves with a log-rank test were adopted in the survival analysis. Statistical analysis in this study was performed with the R statistical package (R version 4.0.1).

Results

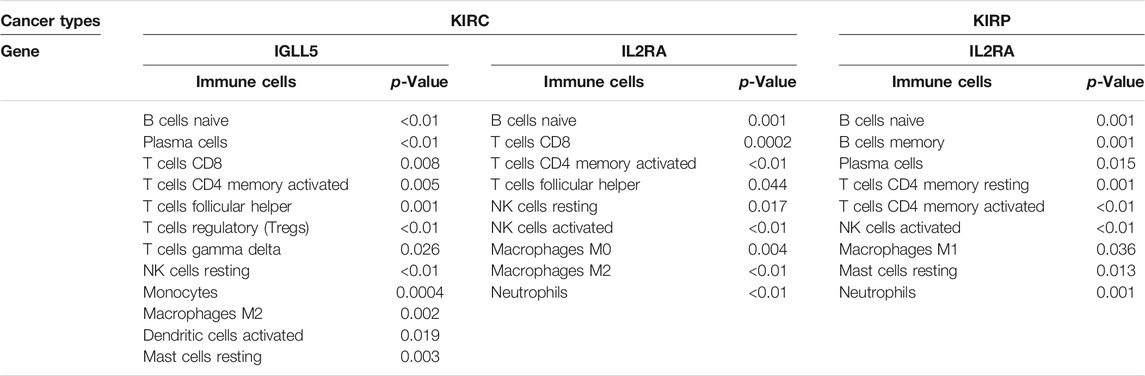

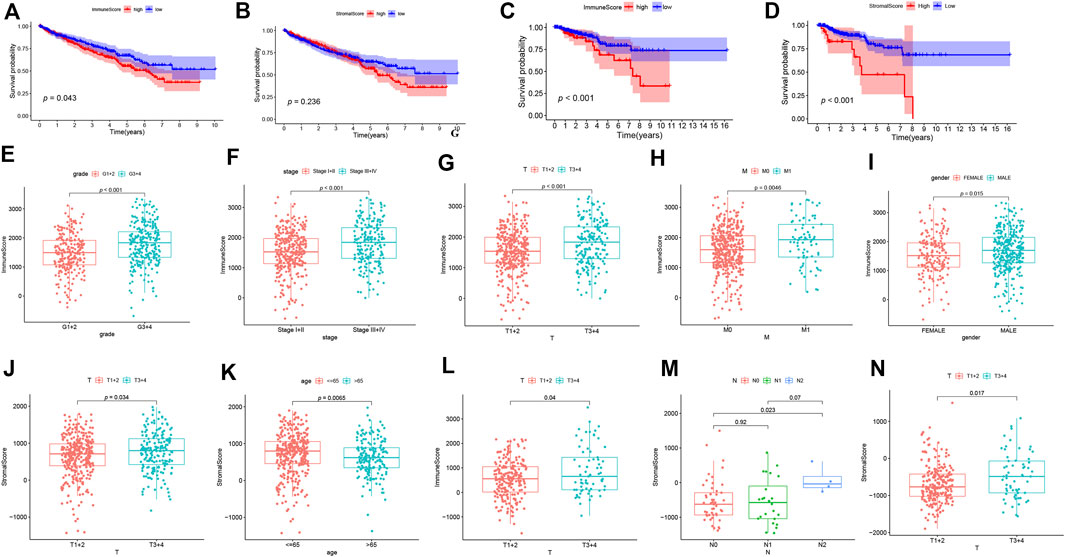

Correlation of ESTIMATE Scores in ccRCC and pRCC

We first determined the association between ESTIMATE scores (including immune scores and stromal scores), prognosis as well as clinical characteristics in ccRCC and pRCC. As shown in Figures 1A,B, ccRCC patients with high immune scores had poor prognosis, but stromal scores did not have apparently association with survival. However, in pRCC patients, a decrease in overall survival was correlated with high immune scores and stromal scores (Figures 1C,D). In addition, for ccRCC, immune scores were positively associated with tumor grade, tumor stage, T stage, and M stage. Patients with advanced T stage had relatively higher stromal scores (Figures 1E–K). For pRCC, higher immune scores were associated with T stage, while patients with advanced T stage and N stage have high stromal scores (Figures 1L–N).

FIGURE 1. The correlation analysis between ESTIMATE scores and prognosis of patients. (A-D) The K-M curves for ESTIMATE scores in ccRCC (A-B) and pRCC (C-D). (E-N) The correlation analysis between ESTIMATE scores and clinicopathological features in ccRCC (E-K) and pRCC (L-N).

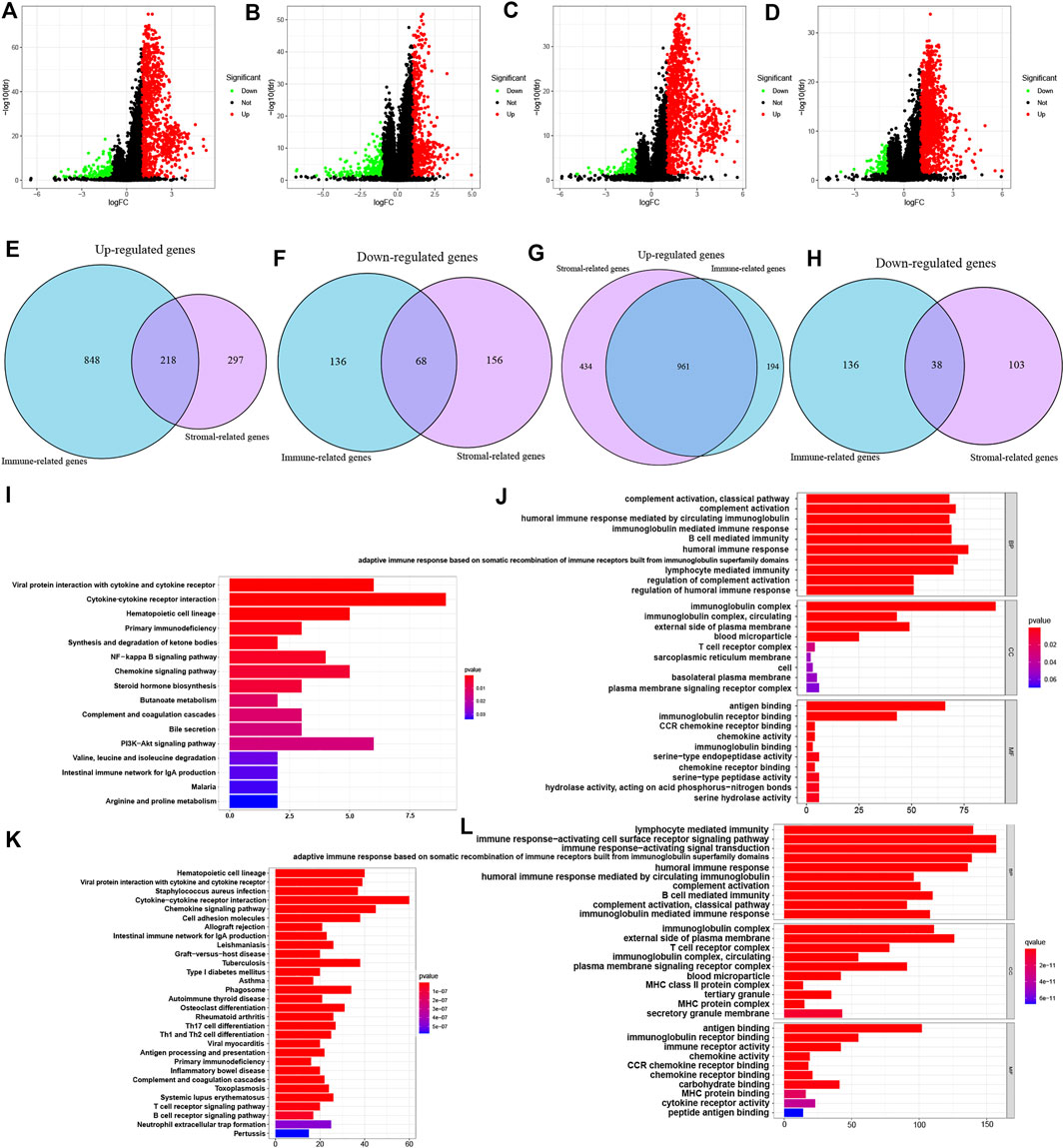

Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes

Based on immune scores and stromal scores, we determined the DEGs by analyzing the expression data of all ccRCC and pRCC samples. In ccRCC, 1066 genes were upregulated and 204 genes were downregulated in samples with high immune score. Similarly, we also identified 515 genes that were highly expressed and 221 genes with low expression in ccRCC samples with high stromal score (logFC >1; p < 0.05; Figures 2A,B). In pRCC, 1155 genes had high expression levels and 174 genes had low expression in patients with high immune scores, and 1395 genes were upregulated as well as 141 downregulated in patients with high stromal scores (Figures 2C,D). Using Venn plot, we determined 218 genes with high expression and 68 genes with low expression in ccRCC patients with high scores (Figures 2E,F). pRCC patients with high scores presented 961 genes that were upregulated and 38 genes that were downregulated, respectively (Figures 2G,H).

FIGURE 2. Identification of DEGs based on ESTIMATE scores and functional analysis of common DEGs. (A-D) Volcano plot of DEGs from the immune scores and stromal score groups in ccRCC (A-B) and pRCC (C-D). (E-H) Commonly changed genes in immune scores and stromal scores groups in ccRCC (E-F) and pRCC (G-H). (I-L) KEGG and GO enrichment analysis in ccRCC (I-J) and pRCC (K-L).

On the basis of these selected DEGs, we performed GO and KEGG enrichment analyze in two types of kidney cancers. The GO analysis showed that DEGs identified in ccRCC and pRCC cases were primarily enriched in immune-related functions, such as B cell-mediated immunity and lymphocyte-mediated immunity (Figures 2J–L). We also listed the top 10 KEGG pathways for both ccRCC and pRCC. As shown in Figures 2I–K, various common immune-related signaling pathways were enriched. Furthermore, DEGs from pRCC samples were also enriched in several pathways related to T-cell receptor and B-cell receptor signaling pathways (Figure 2K).

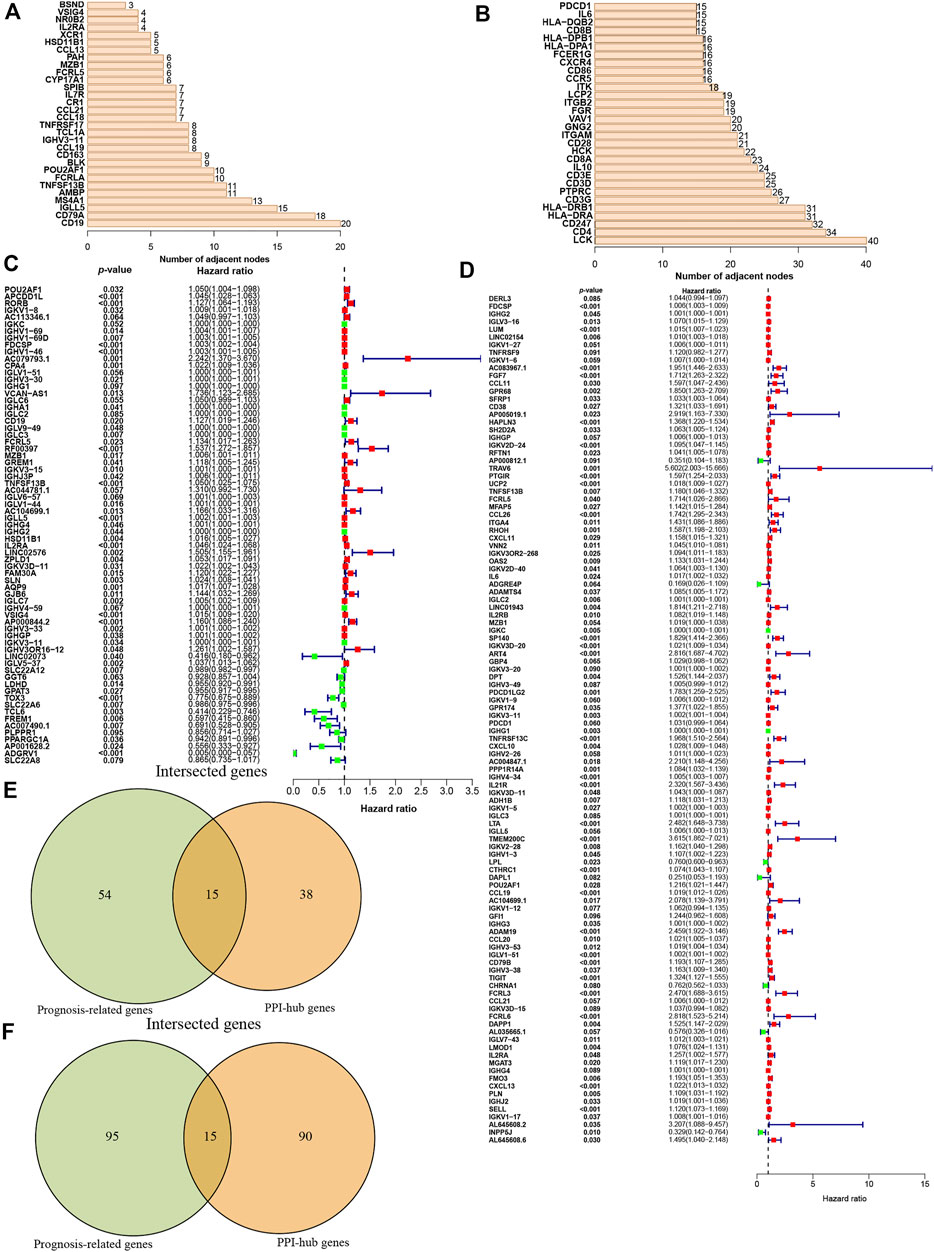

PPI Network and Prognostic Analysis of DEGs

Then these identified DEGs were used to construct the PPI networks. We ranked the DEGs genes by their nodes (Figures 3A,B) and identified hub genes via “Cytoscape” (Supplementary Figures S1A–D). Moreover, we further investigated prognostic genes by performing the univariate Cox analysis among all DEGs in ccRCC and pRCC, respectively. This revealed that 69 genes were related to ccRCC prognosis, and 110 genes were associated with the prognosis of pRCC patients (p < 0.1, Figures 3C,D). Then, we interrogated the top 15 prognosis-related hub genes in ccRCC and pRCC utilizing Venn algorithm (Figures 3E,F). Among 30 selected prognosis-related hub genes in ccRCC and pRCC, two common genes, IGLL5 and IL2RA, were identified, which could potentially play essential role in TME as well as survival in ccRCC and pRCC.

FIGURE 3. Identification of the prognostic hub DEGs. (A-B) Hub DEGs ranked by the number of nodes in ccRCC (A) and Prcc (B). (C-D) Construction of univariate Cox analysis in ccRCC (C) and pRCC (D). (E-F) Identification of prognostic hub DEGs via Venn diagram in ccRCC (E) and pRCC (F).

Correlation and GSEA Enrichment Analyses of IGLL5 and IL2RA

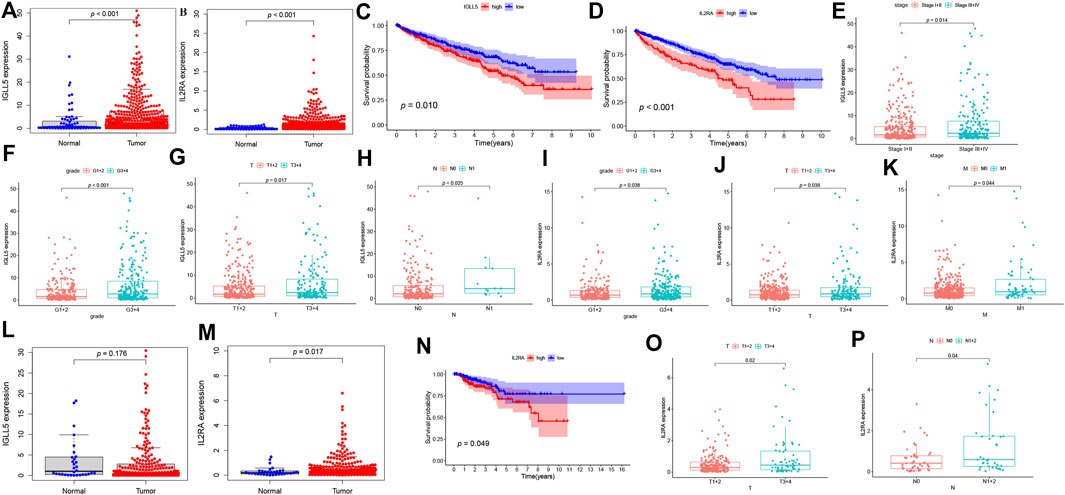

To further assess the expression profile and clinical values of IGLL5 and IL2RA, we extracted the corresponding expression data, as well as clinical information. Both IGLL5 and IL2RA showed high expression in ccRCC samples (p < 0.05, Figures 4A,B). Furthermore, a decrease in overall survival was associated with high expression of IGLL5 and IL2RA (p < 0.05, Figures 4C,D). IGLL5 and IL2RA expression were also positively associated with the stage of ccRCC patients, including high tumor stage, tumor grade, T stage, and more lymph node metastases (p < 0.05, Figures 4E–K).

FIGURE 4. Survival analysis and the clinic correlation analysis in ccRCC and pRCC. (A-B, L-M) Differential expression analysis of IGLL5 and IL2RA in ccRCC (A-B) and pRCC samples (L-M). (C-D) Survival analysis of IGLL5 and IL2RA groups in ccRCC and pRCC samples (N). (E-K) The correlation analyses of IGLL5 (E-H) and IL2RA (I-K, O-P) expression with clinicopathological parameters in ccRCC and pRCC samples.

The same approach was used to analyze two genes in pRCC patients. The differential expression analysis confirmed that IL2RA expressed highly in tumor as well (p < 0.05, Figure 4M), but significant differences in expression of IGLL5 between normal and tumor patients was not observed (p > 0.05, Figure 4M). Based on these results, we chose IL2RA for further analysis. In pRCC patients, poor survival was associated with high expression of IL2RA (p < 0.05, Figure 4N). Moreover, high IL2RA expression was associated with various clinical characteristics, including T and N stage indicative of disease progression. (p < 0.05, Figures 4O,P).

Next, we explored the potential regulation pathways through GSEA enrichment analysis in ccRCC and pRCC samples. Several immune-related pathways, including B cell and T cell receptor signaling pathways, chemokine signaling, and natural killer cell mediated cytotoxicity, which were closely correlated with IGLL5 and IL2RA expression (NES >1, p < 0.05, FRD <0.25, Supplementary Figures S2A–C).

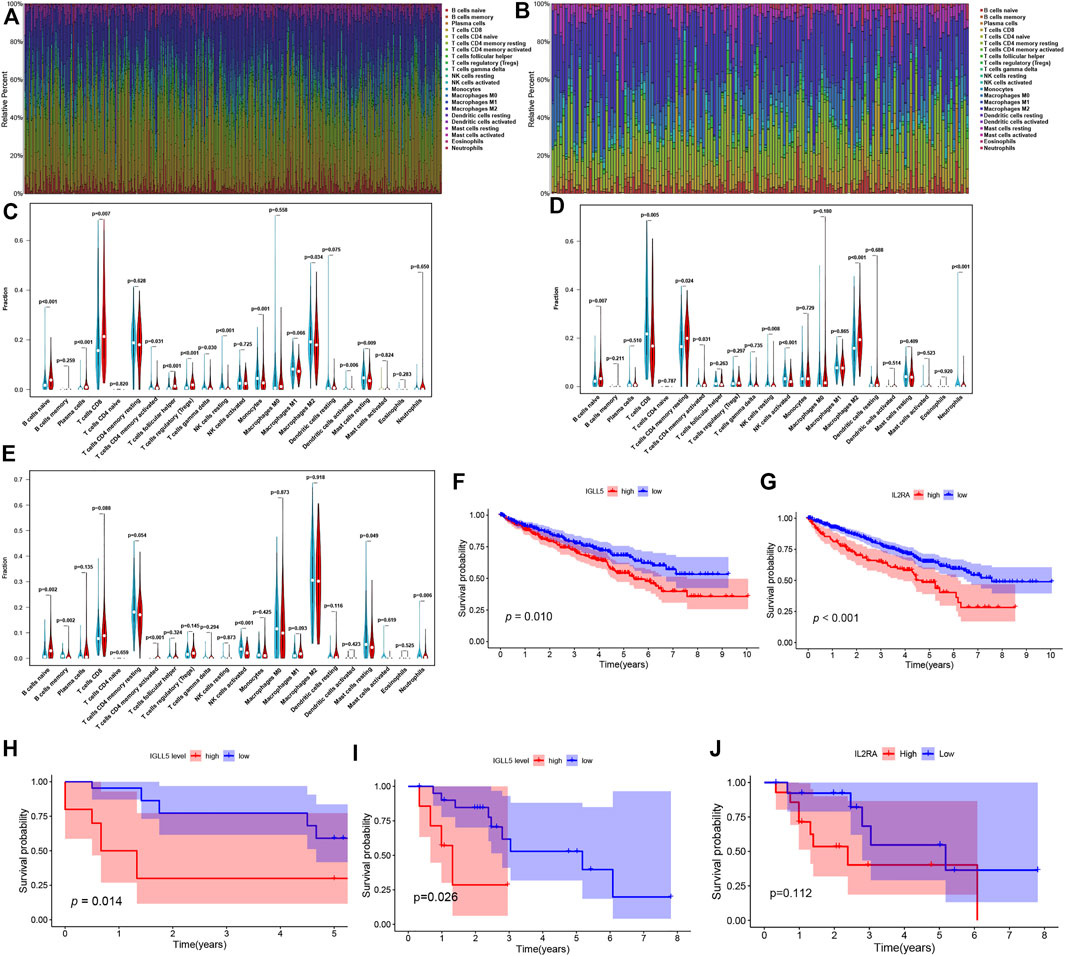

Composition of Immune Cells and Correlation Analysis

To further verify the essential role of major immune cells in ccRCC and pRCC, we explored immune cell infiltration and correlation between two genes and major immune cells. The profile of the principle immune cells showed that adaptive immune cells (such as native B cells, memory B cells, native and memory CD4+ cell, CD8+ T cells) accounted for a substantial part of the immune cells in ccRCC as well as pRCC (Figures 5A,B). Next, we investigated differences in the fraction of major types of immune cells according to expression levels of IGLL5 and IL2RA. For ccRCC, high IGLL5 expression was directly proportional to most adaptive immune cells (including native B cell, CD4+ memory T cells, CD8+ T cells, T follicular helper cells, and regulatory T cells) and was inversely proportion to several innate immune cells (such as NK cell, monocytes, M2 macrophages, activated dendritic cells, and mast cells) (p < 0.05, Figure 5C). Moreover, the difference analysis between high and low expression level of IL2RA in ccRCC illustrated that the high IL2RA expression set presented a significantly larger fraction of native B cells, CD4+ memory T cells, and M2 macrophages, than CD8+ T cells, NK cells, and neutrophils (p < 0.05, Figure 5D). The same approach was used to assess IL2RA in pRCC, which revealed that high IL2RA expression set had higher fraction of native B cells, neutrophils, and a lower proportion of memory B cells, activated CD4+ T memory cells, activated NK cells and resting mast cells (p < 0.05, Figure 5E).

FIGURE 5. Composition of immune cells and correlation analysis. (A,B) landscape of the 22 Immune cell in ccRCC (A) and pRCC (B). (C-E) Differences of immune cells infiltration in ccRCC (C,D) and pRCC (E). (F-I) Validation of IGLL5 and IL2RA in ICGC cohort (F-G), GSE40912 (H) and GSE2748 (I-J).

We also detected the correlation of IGLL5 and IL2RA with immune cell abundance. In ccRCC, the correlation analyses showed that IGLL5 and most adaptive immune cells had a clear linear positive correlation and had a negative correlation with the infiltration of native immune cells (p < 0.05, Supplementary Figure S3). For IL2RA, there was a positive relationship with native B cells, activated CD4+ memory T cells, and M0 and M2 macrophages. However, an inverse correlation was observed between IL2RA and CD8+ T cells, T follicular helper cells, and NK cells (p < 0.05, Supplementary Figure S4). In pRCC, IL2RA showed a positive correlativity with activated CD4+ T memory cells, native B cells, M1 macrophages and neutrophils but had negative relationship with resting CD4+ T memory cells, memory B cells, and mast cells (p < 0.05, Supplementary Figure S5). Finally, on the basis of above analyses, we further investigated the intersected immune cells associated with both IGLL5 and IL2RA in ccRCC and pRCC (Table. 1).

Prognostic Value of IGLL5 and IL2RA in Validation Cohort

We utilized RCC data from the ICGC and GEO database to validate the prognostic value as well. In RCC patients from the ICGC database, a decrease in overall survival was significantly related to the high expression of IGLL5 and IL2RA (p < 0.05, Figures 5F,G). We then explored the prognostic value of IGLL5 and IL2RA using data from GSE40912 (n = 32 samples) and GSE2748 (n = 28 samples) datasets. The results indicated that high expression of IGLL5 was significantly associated with poor prognosis (p < 0.05, Figures 5H,I). Patients with high expression of IL2RA had poor survival, but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.112, Figure 5J)

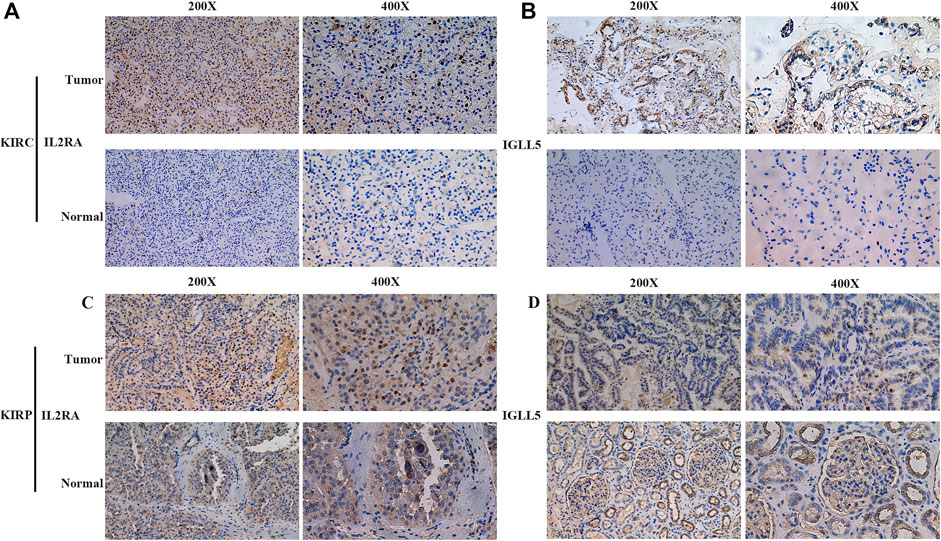

Furthermore, the robustness of IGLL5 as well as IL2RA as biomarkers was verified using primary ccRCC and pRCC samples from Shandong provincial Hospital affiliated to Shandong First University. For ccRCC, IHC images indicated that normal renal tissue had weak staining for IGLL5 and IL2RA, but relatively strong staining patterns for IGLL5 and IL2RA were observed in the cytoplasm of tumor tissues (Figures 6A,B). Moreover, similar staining patterns for IL2RA were observed in pRCC tissues and adjacent normal tissues (Figure 6C). However, IGLL5 staining was weakly positive by IHC, and no significant differences was detected between pRCC tissues and adjacent normal tissues (Figure 6D). These unique IHC staining patterns further confirmed the above results and illustrate that the two genes could be used to predict clinical outcome and distinguish cancerous tissue from normal tissue.

FIGURE 6. Representative IHC images of IGLL5 and IL2RA in ccRCC and pRCC samples. (A,B) IHC patterns for IL2RA (A) and IGLL5 (B) in normal and KIRC samples. (C,D) IHC patterns for IL2RA (C) and IGLL5 (D) in normal and KIRP samples.

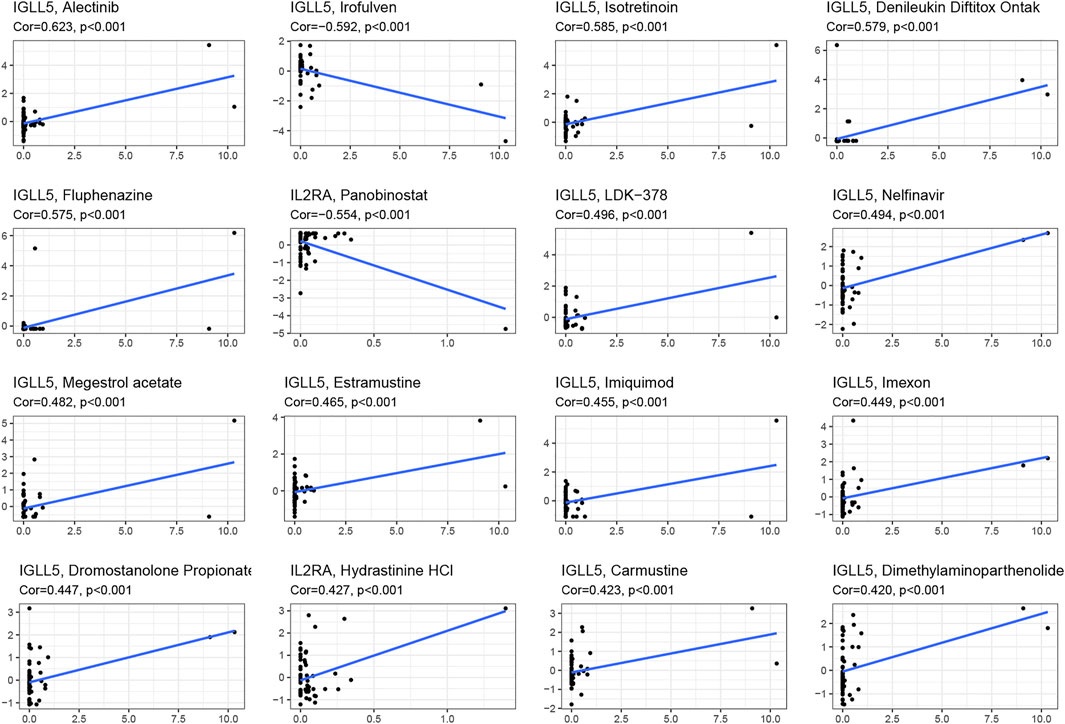

Pharmacological Analysis

We asked whether selected regulators have ability to predict drug response and potential treatment options for ccRCC and pRCC. Through CellMiner database and Connectivity Map (Cmap), the top 16 relevant correlations between IGLL5 and IL2RA and drug activity were shown in Figure 7. The response to all anticancer drugs was negatively correlated to the expression level of IL2RA, including panobinostat, pralatrexate, AT-13387, belinostat, and ponatinib. However, except for irofulven, other anticancer drugs were positively associated with the expression of IGLL5 (p < 0.05, Supplementary Table S1). Moreover, potential drugs for ccRCC and pRCC were predicted based on the top 15 prognosis-related hub genes (Figures 3E,F). The prediction results revealed that 325 and 47 candidate drugs exhibited promising clinical applications for ccRCC and pRCC, respectively (Score ≤ −0.75, Supplementary Table S2, S3). The molecular structure of top 10 potentially active drugs for the treatment of two types of RCC was shown in Supplementary Figure S6.

Discussion

RCC accounts for more than 90% of kidney cancers, which consists of over 10 histological subtypes. Among these, ccRCC and pRCC are the main subtypes with high incidence and high mortality (Comprehensive molecular c, 2013; Chen et al., 2016; Linehan et al., 2016; Hsieh et al., 2017). Given limited options of effective therapy and modest effects of immunotherapy, there is an urgent need for novel biomarkers for future clinical application and evaluation (Barata and Rini, 2017).

Several studies have established that TME is a potential regulator of cancer progression and a source of therapeutic targets (Quail and Joyce, 2013; Vitale et al., 2019; Ho et al., 2020). In complex TME, immune cells and stromal cells play a significant role in cancer development. Stromal cells are genetically stable, and are considered as promising therapeutic targets for reducing tumor recurrence and drug resistance (Quail and Joyce, 2013). In TME, immune cells are divided into tumor antagonizing and promoting-immune cells. With the ability to regulate tumor progression in various stages (Lei et al., 2020). For example, inflammation could lead to CD8+ T cell dysfunction and consequently promote cancer progression (Wherry, 2011). Furthermore, in breast TME, NK cells are immature and dysfunctional NK in hepatocellular TME is related with cancer development (Krneta et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017). Garaud et al. found that infiltration of B cells in breast TME was correlated with a favorable prognosis (Garaud et al., 2019). However, several investigations have revealed that B cells may facilitate tumorigenesis by suppressing CD8+ T cells and producing cytokines, which contribute to angiogenesis (de Visser et al., 2005; Inoue et al., 2006; Tsou et al., 2016). Currently, the understanding of knowledge of TME of kidney cancers is restricted to specific tumor types and there is a lack of comprehensive analysis.

Here, we used several analyses to explore the TME landscape of ccRCC and pRCC. Firstly, we calculated the immune scores as well as stromal scores and assessed the clinical relevance by integrating of clinical information, which revealed that the survival of ccRCC and pRCC patients was significantly correlated with high immune scores and/or stromal scores. Moreover, various clinical characteristics, such as tumor grade, tumor stage, T stage, M stage were associated with immune scores and stromal scores. Then, by investigating the associated biological functions and pathways via GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses, we uncovered diverse immune-related functions and pathways, such as B cell mediated immunity, lymphocyte mediated immunity; cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, chemokine signaling pathways, T cell receptor and B cell receptor signaling pathways. These results are consistent with previous studies and confirmed the essential role of immune cells in ccRCC and pRCC (Xu et al., 2019; Díaz-Montero et al., 2020; Lei et al., 2020; Wan et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2020). Subsequently, according to STRING database, univariate Cox analysis, and Venn algorithm, we identified the two prognostic hub genes, IL2RA and IGLL5 in ccRCC and pRCC. To further exploit the potential role of these genes, we validated each individual gene in TCGA ccRCC and pRCC cohorts. The results revealed that IL2RA is a DEG and is correlated with prognosis of ccRCC and pRCC. However, IGLL5 was significantly expressed in ccRCC, but not in pRCC. In the ICGC, GEO40912, and GSE2748 validation cohort, we also observed a significantly differential survival trend. However, K-M analysis of OS indicated that high expression of IL2RA had a negative impact in GSE2748 dataset, but the difference was not significant. Moreover, the clinical application of the two genes was also validated using primary KIRC and KIRP samples from our hospital, and the results further confirmed the prognostic value of the two genes in clinical application. Previous research on IGLL5 and IL2RA focused predominantly on hematological malignancies. Fusion or mutation of IGLL5 was identified in Burkitt lymphoma, multiple lymphadenopathy, diffuse large B cell lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (Kasar et al., 2015; White et al., 2018; Panea et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; Mosquera Orgueira et al., 2021). It has been reported that IGLL5 may act as a risk factor and was related with metastasis and poor prognosis of multiple myeloma (White et al., 2018; Barwick et al., 2019; D'Agostino et al., 2020). IGLL5 is also correlated with glioblastoma survival and breast cancer, which could serve as a biomarker for relapse-free survival in breast cancer with more than 85% accuracy (Ascierto et al., 2012; Qin et al., 2020). IL2RA also exhibits prognostic and diagnostic value in hematopoietic cancers and solid cancers. Elevated expression of IL2RA is associated with poor prognosis and may act as a biomarker in acute myeloid leukemia (Du et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2019). Up-regulated IL2RA was also found in tumor of lung, prostate, breast and melanoma, and thus, could serve as a marker of prognosis and immunoreaction (Kuhn and Dou, 2005).

Based on these results, we explored underlying mechanisms by GSEA analysis and also uncovered various immune-related pathways, further confirming the role of IGLL5 and IL2RA in immune regulation. Afterwards, CIBERSORT indicated that adaptive immune cells account for most of the immune cell infiltrations in ccRCC as well as pRCC. According to difference analysis and correlation analysis, we finally identified the immune cells commonly associated with IGLL5 and IL2RA in ccRCC and pRCC, such as CD8+ T cells, Tregs cells and T follicular helper cells, which was consistent with prior studies (Roth et al., 2018; Cañete et al., 2019; Ohue et al., 2019). Considering the unsatisfactory outcomes of therapy, we predicted small molecular compounds and individual response to drugs. Some commonly used drugs (such as oxaliplatin, ponatinib) have been shown to be influenced by IGLL5 and IL2RA, and numerous small molecular compounds have promising potential in future treatments. Currently, drugs targeting IL2RA consist of recombinant IL2, anti-IL2RA antibodies (such as basiliximab, daclizumab), anti-IL2RA radioimmunoconjuates (such as CHT-25, 90Y-daclizumab), anti-IL2RA immunotoxins (such as LMB-2, RFT5-SMPT-dgA) and anti-IL2RA antibody drug conjugates (Flynn and Hartley, 2017). However, the efficacy and safety of some drugs is still unclear. Furthermore, IGLL5-targeted drugs have not been developed. Thus, further investigation of drugs targeting IGLL5 and IL2RA is of the essence.

In addition, there are other potential factors which also affect clinical outcomes in kidney cancers. Firstly, the spatial distribution of TME-regulated T cells may physically exclude these immune cells from the vicinity of cancer cells. Other essential considerations are that the stages of primary tumor and potentially different constitution of TME at metastatic sites (Fridman et al., 2012). To improve the outcome of ccRCC and pRCC, accurate and efficient biomarkers are indispensable. We investigated the TME and immune-related genes to identify associated immune cells and molecular mechanism as well as clinical value. Our findings suggested that IGLL5 and IL2RA could be used to estimate prognosis and may serve as potential therapeutic targets. The limited number of patients in GEO validation cohort may partially lead to bias. Therefore, in future investigations, expression data and clinical information from our medical center will be collected and further experiments using in vivo and in vitro models will be implemented to confirm the significant role of the two genes in the TME of kidney cancer.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Shandong Provincial Hospital Ethics Committee. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: BZ, WH; Methodology: BZ, ZN, JW, ZY; Writing—original draft preparation: BZ, FX, WH, and FC; Writing—review and editing: ZN, WH; Supervision: ZN, WH.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmolb.2021.760031/full#supplementary-material

References

Ascierto, M. L., Kmieciak, M., Idowu, M. O., Manjili, R., Zhao, Y., Grimes, M., et al. (2012). A Signature of Immune Function Genes Associated with Recurrence-free Survival in Breast Cancer Patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 131 (3), 871–880. doi:10.1007/s10549-011-1470-x

Barata, P. C., and Rini, B. I. (2017). Treatment of Renal Cell Carcinoma: Current Status and Future Directions. CA: a Cancer J. clinicians 67 (6), 507–524. doi:10.3322/caac.21411

Barwick, B. G., Neri, P., Bahlis, N. J., Nooka, A. K., Dhodapkar, M. V., Jaye, D. L., et al. (2019). Multiple Myeloma Immunoglobulin Lambda Translocations Portend Poor Prognosis. Nat. Commun. 10 (1), 1911. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09555-6

Cañete, P. F., Sweet, R. A., Gonzalez-Figueroa, P., Papa, I., Ohkura, N., Bolton, H., et al. (2019). Regulatory Roles of IL-10-producing Human Follicular T Cells. J. Exp. Med. 216 (8), 1843–1856. doi:10.1084/jem.20190493

Chen, F., Zhang, Y., Şenbabaoğlu, Y., Ciriello, G., Yang, L., Reznik, E., et al. (2016). Multilevel Genomics-Based Taxonomy of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cel Rep. 14 (10), 2476–2489. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.024

Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Nature. 2013; 499 (7456): 43–49. doi:10.1038/nature12222

D'Agostino, M., Zaccaria, G. M., Ziccheddu, B., Rustad, E. H., Genuardi, E., Capra, A., et al. (2020). Early Relapse Risk in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma Characterized by Next-Generation Sequencing. Clin. Cancer Res. 26 (18), 4832–4841. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-20-0951

de Visser, K. E., Korets, L. V., and Coussens, L. M. (2005). De Novo carcinogenesis Promoted by Chronic Inflammation Is B Lymphocyte Dependent. Cancer cell 7 (5), 411–423. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.014

Díaz-Montero, C. M., Rini, B. I., and Finke, J. H. (2020). The Immunology of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 16 (12), 721–735. doi:10.1038/s41581-020-0316-3

Du, W., He, J., Zhou, W., Shu, S., Li, J., Liu, W., et al. (2019). High IL2RA mRNA Expression Is an Independent Adverse Prognostic Biomarker in Core Binding Factor and Intermediate-Risk Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J. Transl Med. 17 (1), 191. doi:10.1186/s12967-019-1926-z

Flynn, M. J., and Hartley, J. A. (2017). The Emerging Role of Anti-CD25 Directed Therapies as Both Immune Modulators and Targeted Agents in Cancer. Br. J. Haematol. 179 (1), 20–35. doi:10.1111/bjh.14770

Fridman, W. H., Pagès, F., Sautès-Fridman, C., and Galon, J. (2012). The Immune Contexture in Human Tumours: Impact on Clinical Outcome. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12 (4), 298–306. doi:10.1038/nrc3245

Garaud, S., Buisseret, L., Solinas, C., Gu-Trantien, C., de Wind, A., Van den Eynden, G., et al. (2019). Tumor Infiltrating B-Cells Signal Functional Humoral Immune Responses in Breast Cancer. JCI insight 5 (18), e129641. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.129641

Grivennikov, S. I., Greten, F. R., and Karin, M. (2010). Immunity, Inflammation, and Cancer. Cell. 140 (6), 883–899. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025

Hanahan, D., and Coussens, L. M. (2012). Accessories to the Crime: Functions of Cells Recruited to the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer cell 21 (3), 309–322. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.022

Ho, W. J., Jaffee, E. M., and Zheng, L. (2020). The Tumour Microenvironment in Pancreatic Cancer - Clinical Challenges and Opportunities. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17 (9), 527–540. doi:10.1038/s41571-020-0363-5

Hsieh, J. J., Purdue, M. P., Signoretti, S., Swanton, C., Albiges, L., Schmidinger, M., et al. (2017). Renal Cell Carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 3, 17009. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.9

Inoue, S., Leitner, W. W., Golding, B., and Scott, D. (2006). Inhibitory Effects of B Cells on Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Res. 66 (15), 7741–7747. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-05-3766

Joyce, J. A., and Pollard, J. W. (2009). Microenvironmental Regulation of Metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9 (4), 239–252. doi:10.1038/nrc2618

Kasar, S., Kim, J., Improgo, R., Tiao, G., Polak, P., Haradhvala, N., et al. (2015). Whole-genome Sequencing Reveals Activation-Induced Cytidine Deaminase Signatures during Indolent Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Evolution. Nat. Commun. 6, 8866. doi:10.1038/ncomms9866

Krneta, T., Gillgrass, A., Chew, M., and Ashkar, A. A. (2016). The Breast Tumor Microenvironment Alters the Phenotype and Function of Natural Killer Cells. Cell Mol Immunol 13 (5), 628–639. doi:10.1038/cmi.2015.42

Kuhn, D. J., and Dou, Q. P. (2005). The Role of Interleukin-2 Receptor Alpha in Cancer. Front. Biosci. 10, 1462–1474. doi:10.2741/1631

Lei, X., Lei, Y., Li, J.-K., Du, W.-X., Li, R.-G., Yang, J., et al. (2020). Immune Cells within the Tumor Microenvironment: Biological Functions and Roles in Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 470, 126–133. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2019.11.009

Li, M., Su, X., Wang, Y., Fan, L., Chai, J., Li, P., et al. (2020). Lineage-negative Lymphoma with a Helper Innate Lymphoid Cell Phenotype. Virchows Arch. 476 (2), 285–293. doi:10.1007/s00428-019-02658-x

Linehan, W. M., Linehan, W. M., Spellman, P. T., Ricketts, C. J., Creighton, C. J., Fei, S. S., et al. (2016). Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Papillary Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 374 (2), 135–145. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1505917

Mosquera Orgueira, A., Ferreiro Ferro, R., Díaz Arias, J. Á., Aliste Santos, C., Antelo Rodríguez, B., Bao Pérez, L., et al. (2021). Detection of New Drivers of Frequent B-Cell Lymphoid Neoplasms Using an Integrated Analysis of Whole Genomes. PloS one 16 (5), e0248886. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248886

Nguyen, C. H., Glüxam, T., Schlerka, A., Bauer, K., Grandits, A. M., Hackl, H., et al. (2019). SOCS2 Is Part of a Highly Prognostic 4-gene Signature in AML and Promotes Disease Aggressiveness. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 9139. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-45579-0

Ohue, Y., Nishikawa, H., and Regulatory, T. (2019). Regulatory T (Treg) Cells in Cancer: Can Treg Cells Be a New Therapeutic Target? Cancer Sci. 110 (7), 2080–2089. doi:10.1111/cas.14069

Osipov, A., Saung, M. T., Zheng, L., and Murphy, A. G. (2019). Small Molecule Immunomodulation: the Tumor Microenvironment and Overcoming Immune Escape. J. Immunotherapy Cancer 7 (1), 224. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0667-0

Panea, R. I., Love, C. L., Shingleton, J. R., Reddy, A., Bailey, J. A., Moormann, A. M., et al. (2019). The Whole-Genome Landscape of Burkitt Lymphoma Subtypes. Blood 134 (19), 1598–1607. doi:10.1182/blood.2019001880

Pitt, J. M., Marabelle, A., Eggermont, A., Soria, J.-C., Kroemer, G., and Zitvogel, L. (2016). Targeting the Tumor Microenvironment: Removing Obstruction to Anticancer Immune Responses and Immunotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 27 (8), 1482–1492. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdw168

Qin, Z., Zhang, X., Chen, Z., and Liu, N. (2020). Establishment and Validation of an Immune-Based Prognostic Score Model in Glioblastoma. Int. immunopharmacology 85, 106636. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106636

Quail, D. F., and Joyce, J. A. (2013). Microenvironmental Regulation of Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Nat. Med. 19 (11), 1423–1437. doi:10.1038/nm.3394

Ravaud, A., Motzer, R. J., Pandha, H. S., George, D. J., Pantuck, A. J., Patel, A., et al. (2016). Adjuvant Sunitinib in High-Risk Renal-Cell Carcinoma after Nephrectomy. N. Engl. J. Med. 375 (23), 2246–2254. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1611406

Roth, T. L., Puig-Saus, C., Yu, R., Shifrut, E., Carnevale, J., Li, P. J., et al. (2018). Reprogramming Human T Cell Function and Specificity with Non-viral Genome Targeting. Nature 559 (7714), 405–409. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0326-5

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E., and JemalCancer Statistics, A. (2021). Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA A. Cancer J. Clin. 71 (1), 7–33. doi:10.3322/caac.21654

Steffens, S., Janssen, M., Roos, F. C., Becker, F., Schumacher, S., Seidel, C., et al. (2012). Incidence and Long-Term Prognosis of Papillary Compared to clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma - A Multicentre Study. Eur. J. Cancer 48 (15), 2347–2352. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2012.05.002

Szklarczyk, D., Gable, A. L., Lyon, D., Junge, A., Wyder, S., Huerta-Cepas, J., et al. (2019). STRING V11: Protein-Protein Association Networks with Increased Coverage, Supporting Functional Discovery in Genome-wide Experimental Datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 (D1), D607–D613. doi:10.1093/nar/gky1131

Tsou, P., Katayama, H., Ostrin, E. J., and Hanash, S. M. (2016). The Emerging Role of B Cells in Tumor Immunity. Cancer Res. 76 (19), 5597–5601. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-16-0431

Vitale, I., Manic, G., Coussens, L. M., Kroemer, G., and Galluzzi, L. (2019). Macrophages and Metabolism in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cel Metab. 30 (1), 36–50. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2019.06.001

Vuong, L., Kotecha, R. R., Voss, M. H., and Hakimi, A. A. (2019). Tumor Microenvironment Dynamics in Clear-Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 9 (10), 1349–1357. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.cd-19-0499

Wan, B., Liu, B., Huang, Y., and Lv, C. (2020). Identification of Genes of Prognostic Value in the ccRCC Microenvironment from TCGA Database. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 8 (4), e1159. doi:10.1002/mgg3.1159

Wang, Q., Chen, C., Ding, Q., Zhao, Y., Wang, Z., Chen, J., et al. (2020). METTL3-mediated m6A Modification of HDGF mRNA Promotes Gastric Cancer Progression and Has Prognostic Significance. Gut 69 (7), 1193–1205. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319639

White, B. S., Lanc, I., O’Neal, J., Gupta, H., Fulton, R. S., Schmidt, H., et al. (2018). A Multiple Myeloma-specific Capture Sequencing Platform Discovers Novel Translocations and Frequent, Risk-Associated point Mutations in IGLL5. Blood Cancer J. 8 (3), 35. doi:10.1038/s41408-018-0062-y

Wu, T., and Dai, Y. (2017). Tumor Microenvironment and Therapeutic Response. Cancer Lett. 387, 61–68. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2016.01.043

Xu, W.-H., Xu, Y., Wang, J., Wan, F.-N., Wang, H.-K., Cao, D.-L., et al. (2019). Prognostic Value and Immune Infiltration of Novel Signatures in clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Microenvironment. Aging 11 (17), 6999–7020. doi:10.18632/aging.102233

Yoshihara, K., Shahmoradgoli, M., Martínez, E., Vegesna, R., Kim, H., Torres-Garcia, W., et al. (2013). Inferring Tumour Purity and Stromal and Immune Cell Admixture from Expression Data. Nat. Commun. 4, 2612. doi:10.1038/ncomms3612

Zeng, Q., Zhang, W., Li, X., Lai, J., and Li, Z. (2020). Bioinformatic Identification of Renal Cell Carcinoma Microenvironment-Associated Biomarkers with Therapeutic and Prognostic Value. Life Sci. 243, 117273. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117273

Zhang, Q.-F., Yin, W.-W., Xia, Y., Yi, Y.-Y., He, Q.-F., Wang, X., et al. (2017). Liver-infiltrating CD11b−CD27− NK Subsets Account for NK-Cell Dysfunction in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Are Associated with Tumor Progression. Cel Mol Immunol 14 (10), 819–829. doi:10.1038/cmi.2016.28

Nomenclature

Cmap Connectivity map

ccRCC Clear cell renal clear cell carcinoma,

DEGs Differentially expressed genes

ESTIMATE Estimation of STromal and Immune cells in Malignant Tumours using Expression data

GEO Gene Expression Omnibus

GO Gene Ontology

GSEA Gene set enrichment analysis

ICGC International Cancer Genome Consortium

KEGG Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

pRCC Papillary renal cell carcinoma

PPI Protein–protein interaction

RCC Renal clear cell carcinoma

TCGA The Cancer Genome Atlas

TME Tumor microenvironment

IHC Immunohistochemistry.

Keywords: clear cell renal carcinoma, papillary renal cell carcinoma, prognosis, tumor microenvironment, immunotherapy

Citation: Zheng B, Xie F, Cheng F, Wang J, Yao Z, He W and Niu Z (2021) Integrative Analysis of Immune-Related Genes in the Tumor Microenvironment of Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma and Renal Papillary Cell Carcinoma. Front. Mol. Biosci. 8:760031. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2021.760031

Received: 17 August 2021; Accepted: 15 October 2021;

Published: 23 November 2021.

Edited by:

Florence Le Calvez-Kelm, International Agency For Research On Cancer (IARC), FranceReviewed by:

Imtaiyaz Hassan, Jamia Millia Islamia, IndiaSiddharth Shukla, Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), United States

Copyright © 2021 Zheng, Xie, Cheng, Wang, Yao, He and Niu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei He, SGV3ZWlAYmptdS5lZHUuY24=; Zhihong Niu, bnpoMTc4OUAxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Bin Zheng

Bin Zheng Fang Xie1,4†

Fang Xie1,4† Fajuan Cheng

Fajuan Cheng Jianwei Wang

Jianwei Wang Zhongshun Yao

Zhongshun Yao Wei He

Wei He Zhihong Niu

Zhihong Niu