- 1Department of Chemistry, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, United States

- 2Department of Environmental, Biological and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Technologies, Università Degli Studi Della Campania, Caserta, Italy

- 3Roy J. Carver Department of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Molecular Biology, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, United States

Enzyme I (EI) of the bacterial phosphotransferase system (PTS) is a master regulator of bacterial metabolism and a promising target for development of a new class of broad-spectrum antibiotics. The catalytic activity of EI is mediated by several intradomain, interdomain, and intersubunit conformational equilibria. Therefore, in addition to its relevance as a drug target, EI is also a good model for investigating the dynamics/function relationship in multidomain, oligomeric proteins. Here, we use solution NMR and protein design to investigate how the conformational dynamics occurring within the N-terminal domain (EIN) affect the activity of EI. We show that the rotameric g+-to-g− transition of the active site residue His189 χ2 angle is decoupled from the state A-to-state B transition that describes a ∼90° rigid-body rearrangement of the EIN subdomains upon transition of the full-length enzyme to its catalytically competent closed form. In addition, we engineered EIN constructs with modulated conformational dynamics by hybridizing EIN from mesophilic and thermophilic species, and used these chimeras to assess the effect of increased or decreased active site flexibility on the enzymatic activity of EI. Our results indicate that the rate of the autophosphorylation reaction catalyzed by EI is independent from the kinetics of the g+-to-g− rotameric transition that exposes the phosphorylation site on EIN to the incoming phosphoryl group. In addition, our work provides an example of how engineering of hybrid mesophilic/thermophilic chimeras can assist investigations of the dynamics/function relationship in proteins, therefore opening new possibilities in biophysics.

Introduction

Enzyme I (EI) is the first protein in the bacterial phosphotransferase system (PTS), a signal transduction pathway that controls multiple cellular functions including sugar uptake, catabolic gene expression, interactions between carbon and nitrogen metabolisms, chemotaxis, biofilm formation, and virulence, via phosphorylation-dependent protein-protein interactions (Postma et al., 1993; Clore and Venditti, 2013). The phosphorylation state of EI dictates the phosphorylation state of all other downstream components of the PTS (Deutscher et al., 2014) and malfunction of EI has been linked to reduced growth-rate and attenuated virulence in several bacterial species (Edelstein et al., 1999; Jones et al., 2000; Lau et al., 2001; Kok et al., 2003). Given its central role in controlling bacterial metabolism, EI has been proposed as a target for antimicrobial design (Kok et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2013; Nguyen and Venditti, 2020) or for metabolic engineering efforts aimed at developing more efficient systems for microbial production of chemicals from biomass feedstocks (Doucette et al., 2011; Venditti et al., 2013).

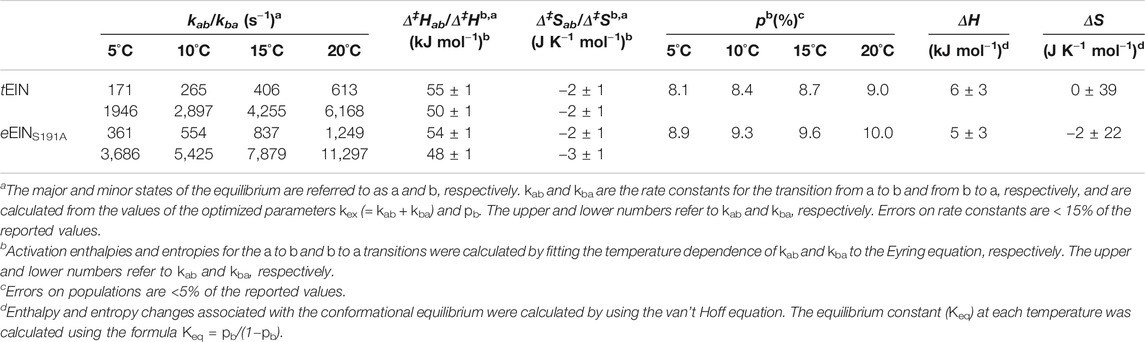

In addition to its relevance for pharmaceutical and biotech applications, EI is an ideal model system for investigating the interplay between ligand binding, post-translational modifications, and conformational dynamics that determine the activity of complex multidomain proteins. Indeed, EI is a 128 kDa dimeric enzyme (Chauvin and Brand, 1996) whose activity depends on the synergistic action of at least four conformational equilibria that results in a series of large intradomain, interdomain, and intersubunit structural rearrangements modulated by substrate binding and two subsequent protein phosphorylation steps (from the substrate to EI and from EI to HPr, the second protein of the PTS) (Figure 1A). The N-terminal phosphoryl-transfer domain (EIN, residues 1–249) contains the phosphorylation site (His189) and the binding site for the phosphocarrier protein, HPr. The C-terminal domain (EIC, residues 261–575) is responsible for dimerization and contains the binding site for the substrate phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and the small molecule regulator α-ketoglutarate (αKG) (Chauvin and Brand, 1996; Venditti et al., 2013). A long helical linker connects the EIN and EIC domains. In the absence of substrate, EI adopts an open conformation in which the EIN domains of the two monomeric subunits are more than 60 Å apart (Schwieters et al., 2010). Binding of PEP induces a transition to the catalytically competent closed form of EI (Venditti et al., 2015a; Venditti et al., 2015b). In the closed structure, the EIN domains of the two monomeric subunits are in direct contact and the active site residue, His189, is inserted in the catalytic pocket on EIC (Figure 1A) (Teplyakov et al., 2006).

FIGURE 1. Conformational equilibria of EI during catalysis. (A) Schematic summary of the EI conformational equilibria during catalysis. The EIN domain is colored blue, the EIC domain is colored red, the PEP molecule is colored green (B) The EIN domain adopts the state A and state B conformation in open (PDB code: 2KX9) and closed (PDB code: 2HWG) EI, respectively. The α and α/β subdomains of EIN are colored blue and light blue, respectively. The active site His189 is shown as pink sticks. The linkers connecting the EIN subdomains and the helical linker connecting EIN to EIC are colored white. (C) The active site His189 adopts the g+ and g− rotameric states in the structures of unphosphorylated and phosphorylated EI, respectively. The α and α/β subdomains of EIN are colored blue and light blue, respectively. The side chains of Thr168 and of unphosphorylated and phosphorylated His189 are shown as sticks (carbon is pink, nitrogen is blue, oxygen is red, and phosphorus is orange).

In recent years, we have published several studies revealing that progressive quenching of the intradomain EIC dynamics is an important source of functional regulation that can be exploited to design allosteric inhibitors of EI. In particular, by using high-pressure NMR we have shown that dimerization of EI promotes substrate binding by providing structural stabilization to the EIC catalytic pocket (Nguyen et al., 2021). Coupling NMR relaxation experiments with Small Angle X-ray Scattering, we showed that binding of PEP results in further quenching of μs-ms dynamics at the EIC catalytic loops that triggers the open-to-close interdomain rearrangement and activates EI for catalysis (Venditti et al., 2015b). Finally, by combining NMR with Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, we noticed that residual conformational heterogeneity at the EIC active site in the activated enzyme-substrate complex determines the enzymatic turnover (Dotas et al., 2020) and that perturbing conformational dynamics at the active site loops is an effective strategy to inhibit the phosphoryl-transfer reaction (Nguyen and Venditti 2020).

Despite the wealth of knowledge we possess about the coupling between EIC conformational flexibility and enzymatic activity, very little is known about if and how EIN conformational dynamics impact the function of the enzyme. Indeed, while a comparison of the experimental atomic-resolution structures of EI indicates that the open-to-close conformational change is coupled to a rigid body reorientation of the α subdomain relative to the α/β subdomain of EIN (commonly referred to as state A-to-state B equilibrium, Figure 1B) and that protein phosphorylation shifts the χ2 angle of His189 from the g+ to g− rotameric state (Figure 1C), it is not clear if these conformational equilibria are active in isolated EIN and if their external perturbation can impact turnover. Addressing these questions will advance our understanding of how synergistic couplings among intradomain, interdomain, and intersubunit conformational equilibria affect the function of a multidomain oligomeric protein such as EI, and will provide new perspectives toward the development of EI inhibitors that act on the EIN domain.

Here we investigate the structure and dynamics of isolated EIN in its native and phosphorylated forms by solution NMR spectroscopy. While we do not detect evidence of an active state A/state B equilibrium, relaxation dispersion experiments indicate that the conformational exchange between the g+ and g− rotameric states of His189 is active in the isolated EIN and modulated by protein phosphorylation. Furthermore, we engineered EIN constructs with modulated thermostability and conformational flexibility by hybridizing EIN from mesophilic and thermophilic organisms. Biophysical characterization of the wild-type and hybrid EIN constructs indicates that the rotameric equilibrium is slower in the thermophilic enzyme than in the mesophilic protein and that a single serine to alanine mutation is responsible for the increased activation energy in the thermophilic species. Finally, we performed functional characterization of the wild-type mesophilic and thermophilic EI, as well as of EI constructs that incorporate the hybridizing mutations. Our data show that, although the His189 rotameric equilibrium is required for the correct functioning of EI, the rate of the phosphoryl transfer reaction is independent on the kinetics of the conformational change, indicating that the g+-to-g− transition is not the rate limiting step for catalysis.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification

E. coli and T. tengcongensis EI, EIN, and HPr were expressed and purified as previously reported (Suh et al., 2008; Venditti and Clore, 2012; Dotas and Venditti, 2019). Single point mutations were introduced using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis.

Thermal Stability and Circular Dichroism

Thermal-induced unfolding of EIN was investigated in a 1 mm, 400 μl, quartz cuvette sample cell using a Jasco J-710 spectropolarimeter. Samples were prepared in H2O at a protein concentration of ∼0.5 mg/ml. Ellipticity (θ222nm) at the 222 nm wavelength was monitored over a 1°C/min temperature gradient ranging from 35 to 75°C and 65–95°C for mesophilic and thermophilic EIN, respectively. The melting temperature (Tm) was calculated as the maximum value of the derivative of θ222nm with respect to temperature.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

NMR samples were prepared in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 90% H2O/10% D2O (v/v). For protein phosphorylation, samples were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with <1 μM of mesophilic EI (eEI) or thermophilic EI (tEI), <1 μM of mesophilic HPr (eHPr) or thermophilic HPr (tHPr), and ∼30 mM of PEP prior to acquisition. Completion of phosphorylation reactions were confirmed by the disappearance of the NMR peaks of the unphosphorylated species from the 1H-15N TROSY spectrum of the proteins. The protein concentration, in subunits, was ∼1 mM for all NMR experiments, unless stated otherwise.

NMR spectra were acquired on Bruker 800, 700, and 600 MHz spectrometers equipped with z-shielded gradient triple resonance cryoprobes. Spectra were processed using NMRPipe (Delaglio et al., 1995) and analyzed using NMRFAM-SPARKY (Lee et al., 2015). 1H-15N TROSY (transverse relaxation-optimized spectroscopy) (Pervushin et al., 1998) and methyl-TROSY (Tugarinov et al., 2003) experiments were acquired using previously described pulse schemes. Resonance assignments of the 1H-15N TROSY spectra for eEIN and tEIN were transferred from previous reports (BMRB accession codes 4,106 and 27,833, respectively) (Garrett et al., 1999; Dotas and Venditti, 2019). Resonance assignments of the 1H-15N TROSY spectra for phosphorylated eEIN (eEIN-P) was kindly provided by Drs. Clore and Suh (Suh et al., 2008). Sequential 1H/15N/13C backbone assignments of phosphorylated tEIN (tEIN-P) were achieved using TROSY versions of conventional 3D triple resonance correlation experiments [HNCO, HNCA, HNCACB, HN(CO)CA, and HN(CO)CACB] (Clore and Gronenborn, 1998). Assignment of the 1H-13Cmethyl correlations of tEIN-P was performed using out and back experiments (Tugarinov et al., 2014). NMR resonance assignments for tEIN-P were deposited on the BioMagResBank (Ulrich et al., 2008) (accession code 50386).

The weighted combined 1H/15N chemical shift perturbations (∆H/N) resulting on the 1H-15N TROSY spectra of EIN from phosphorylation of His189 were calculated using the following equation (Mulder et al., 1999):

where WH (=1) and WN (=0.154) are the weighting factors for the 1H and 15N amide chemical shifts and ∆δH and ∆δN symbolize the 1H and 15N chemical shift differences in ppm between the unphosphorylated and phosphorylated states.

15N-R1 and R1ρ experiments were recorded at 40°C and a 1H frequency of 800 MHz, utilizing heat-compensating pulse schemes with a TROSY readout (Lakomek et al., 2012). A recycle delay of 1.5 s was used for both R1 and R1ρ experiments, with the spin-lock field (ω1) for the R1ρ experiments set to 1 kHz. Relaxation delay durations were 0, 120, 280, 440, 640, 800, 1,040, and 1,200 ms for R1 and 0.2, 4.2, 7.2, 15, 23.4, 32.4, 42, 52.2, and 60 ms for R1ρ, respectively. R1 and R1ρ values were determined by fitting time-dependent exponential restoration of peak intensities at increasing relaxation delays. R2 values were extracted from the measured R1 and R1ρ values. Global rotational correlation times (

where

15N and 13Cmethyl relaxation dispersion (RD) experiments were conducted at 5, 10, 15, and 20°C using a well-established protocol (Singh et al., 2021). In brief, a pulse sequence that measures the exchange contribution for the TROSY component of the 15N magnetization (Loria et al., 1999) and a pulse scheme for 13C single-quantum CPMG (Carr-Purcell-Meinboom-Gill) RD described by Kay and co-workers (Lundström et al., 2007) were employed. Off-resonance effects and pulse imperfections were minimized using a four-pulse phase scheme (Yip and Zuiderweg, 2004). CPMG RD experiments were performed at a 1H frequency of 800 and 600 MHz with fixed relaxation delays (Trelax) of 60 and 30 ms, for 15N and 13Cmethyl experiments, respectively. Different numbers of refocusing pulses were implemented to produce effective CPMG fields (νCPMG) varying from 50 to 1,000 Hz (Mulder et al., 2001). Experimental errors on the transverse relaxation rates (R2) were estimated from the noise level estimated with the NMRFAM-SPARKY software. The resulting RD curves acquired at multiple temperatures and magnetic fields were globally fit to a two-site exchange model using the Carver-Richard equation (Carver and Richards, 1972), as described by Dotas et al. (2020).

Backbone amide 1DNH residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) were measured at 40°C by taking the difference in 1JNH scalar couplings in isotropic and alignment media. Phage pf1 (16 mg/ml; ASLA Biotech) was the employed alignment media and the 1JNH couplings were measured using the RDCs by TROSY pulse scheme (Fitzkee and Bax, 2010). Xplor-NIH (Schwieters et al., 2003) was used to compute singular value decomposition (SVD) analysis of the RDC values.

Enzyme Kinetic Assays

eEI, eEIS191A, tEI, and tEIA191S were investigated for their ability to catalyze the transfer of the phosphoryl group from PEP to HPr. Assays were performed on a Bruker 700 MHz spectrometer at 25°C using 1H-15N Selective Optimized Flip Angle Short Transient (SOFAST) NMR experiments (Schanda et al., 2005), using a protocol previously described (Nguyen et al., 2018). The reaction buffer was 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4), 100 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 90% H2O/10% D2O (v/v). The reaction volume was 500 μl. All enzymatic assays were run at fixed concentrations of enzyme (∼0.005 μM), HPr (600 μM), and PEP (1 mM). The initial velocities (ν0) for the phosphoryl transfer reactions were determined by plotting the concentration of unphosphorylated HPr determined by the 1H-15N cross-peak intensities, as described by Nguyen et al. (2018) vs. time (Figure 5D). All assays were performed in triplicates to estimate the experimental error.

Mass Spectrometry

A binary ACQUITY UPLC H-Class system coupled with Synapt G2-Si HDMS system (Waters, Milford, MA) and electrospray ionization (ESI) source was used to determine the intact masses of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated tEIN. Starting samples were prepared by diluting 10 μl of the NMR samples of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated tEIN with HPLC grade H2O to final concentration of 2 µM. 1 µl of each sample was injected in the mass spectrometer.

UPLC separations were performed using a Restek Ultra C4 column (5 um 50 mm × 1 mm) with a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min. Solvents used were 0.1% formic acid in HPLC grade H2O (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (solvent B, mobile phase). The gradient used started with an initial condition of 5% B for 1 min, followed by a 7 min gradient of 5–100% solvent B. This was held for 4 min before dropping back to the initial 5% buffer B in 1 min and held for the remainder of the run (total 20 min).

The eluant from the UPLC was introduced to the Waters Synapt G2-Si HDMS with TOF mass analyzer using a Waters Lockspray Source (300–5,000 Da mass range). Finally, the intact mass was determined by deconvolution of mass spectra using the MassLynx 4.2 software.

Results

In this contribution, we investigate the structure and conformational dynamics of native and phosphorylated EIN from two organisms: a mesophilic bacterium (Escherichia coli) and a thermophilic organism (Thermoanaerobacter tengcongensis). The two proteins are referred to as eEIN and tEIN in the unphosphorylated state, and eEIN-P and tEIN-P in the phosphorylated state throughout the manuscript, respectively. Further, we examined the effect of two single-point mutations, Ser191→Ala191 within eEIN and Ala191→ Ser191 within tEIN, on protein structure and dynamics. These mutants are denoted eEINS191A and tEINA191S, respectively. Similar notations are used for HPr and the full-length EI (eHPr, tHPr, eEI, tEI, eEIS191A, and tEIA191S). The full-length eEI and tEI share similar sequence (overall identity = 54% and active site identity = 100%) (Supplementary Figure 1) and 3D structure (Oberholzer et al., 2005; Teplyakov et al., 2006; Navdaeva et al., 2011; Evangelidis et al., 2018), but have been shown to be optimally active at 37 and 65°C, respectively, (Navdaeva et al., 2011). The sequence identity of isolated eEIN and tEIN is 48% (Supplementary Figure 1).

Effect of Phosphorylation on the Structure of EIN

Previous structural investigations on eEIN have shown that phosphorylation does not affect the conformation of the eEIN backbone, but results in a transition of the χ2 angle of His189 from the g+ to the g− rotameric state. Such conformational change breaks the hydrogen bond between the Nε2 atom of His189 and the hydroxyl group of Thr168 and grants the inbound phosphoryl group access to the Nε2 atom (Figure 1C) (Garrett et al., 1999; Suh et al., 2008).

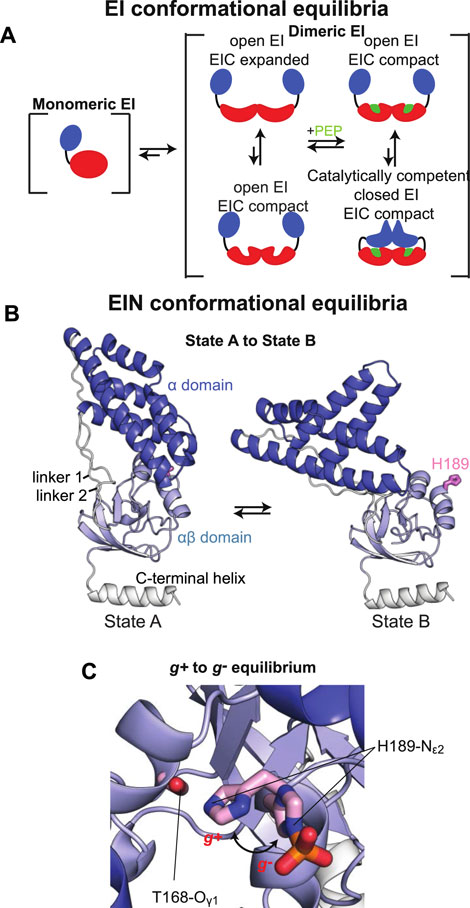

Here, the effect of phosphorylation at the His189 position on the structure of tEIN has been evaluated by NMR chemical shift perturbations and backbone amide residual dipolar coupling (1DNH RDC) data. tEIN-P samples were prepared by adding catalytic amounts (<1 µM) of tEI and tHPr, and a large excess (∼30 mM) of PEP directly to an NMR tube containing ∼1 mM of 15N-labeled tEIN. The phosphoryl transfer reaction is slow on the chemical shift time scale, and distinct NMR peaks are observed for tEIN and tEIN-P (Figure 2D). Therefore, completion of the phosphorylation reaction was determined by disappearance of the NMR peaks of the unphosphorylated species from the 1H-15N TROSY spectrum of the protein. In addition, small aliquots (∼10 µl) of the NMR sample were taken before and after addition of EI, and analyzed by Liquid Chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS-MS). The data indicate that the tEIN mass increases by 80 Da upon incubation with tEI, tHPr, and PEP (Figure 2A), which is consistent with the addition of a single phosphoryl group.

FIGURE 2. Phosphorylation induced structural perturbations in tEIN. (A) Deconvoluted masses of tEIN (black) and tEIN-P (red) from LC-MS. (B) Weighted combined chemical shift perturbations (ΔH/N) induced by phosphorylation of tEIN on the 1H-15N TROSY spectra of the protein are plotted against residue index. (C) The experimental ΔH/N values are plotted on the structure of tEIN (PDB code: 5WOY). Two different tEIN orientations are shown. The relationship between sphere size and color and the value of ΔH/N is depicted by the color bar. The His189 side chain is shown as pink sticks. (D) 800 MHz 1H-15N TROSY spectra of tEIN (black) and tEIN-P (red). (E) Correlation between the secondary Cα chemical shifts measured for tEIN (y-axis) and tEIN-P (x-axis). (F) SVD fitting of the 1DNH RDC data measured for tEIN (black) and tEIN-P (red) against the solution structure of tEIN (PDB code: 5WOY).

NMR resonance assignments for tEIN have been previously reported (BMRB code: 27833) (Dotas and Venditti, 2019). Assignments for tEIN-P were performed using conventional triple resonance correlation experiments (see “Materials and Methods”) and deposited in the BioMagResBank (BMRB code: 50386). 1H/15N chemical shift perturbations (ΔH/N) induced by phosphorylation in the 1H-15N TROSY spectrum of tEIN are plotted against residue index in Figure 2B and displayed as a gradient on the protein structure in Figure 2C. Significant (>0.3 ppm) ΔH/N values are observed exclusively in the vicinity of the phosphorylation site on the α/β subdomain and are presumably a result of electronic effects that arise from the presence of the phosphoryl group as well as ring current effects from the change in the χ2 angle of His189 to accommodate the phosphoryl group at the Nε2 position. Such hypothesis is supported by the excellent agreement between the secondary Cα chemical shifts measured for phosphorylated and unphosphorylated tEIN (Figure 2E), which demonstrates that no transition in backbone conformation occurs upon phosphorylation. Further insight into the effect of phosphorylation on the structure of EIN was obtained by the analysis of 1DNH RDC data measured for tEIN and tEIN-P aligned in a dilute liquid crystalline medium of phage pf1. RDCs of fixed bond vectors, such as the backbone N–H bond vector, are dependent on the orientation of the bond vectors relative to the alignment tensor and thus provide a very sensitive indicator of changes in relative domain orientations (Tjandra and Bax, 1997; Venditti et al., 2016). Singular value decomposition (SVD) fitting of the experimental RDCs measured for tEIN and tEIN-P to the coordinates of the solution structure of unphosphorylated tEIN (PDB code: 5WOY) (Evangelidis et al., 2018) yields R-factors (Clore and Garrett, 1999) of 27.5 and 28.0%, respectively, indicating good agreement between experimental and back-calculated data (Figure 2F). Consequently, one can conclude that the relative orientation of the α and α/β subdomains remains unperturbed by phosphorylation.

In summary, consistent with structural investigations performed previously on eEIN (Suh et al., 2008), the solution NMR data presented in this section indicate that phosphorylation of tEIN results in a localized transition of the rotameric state of the His189 side chain and does not propagate into larger conformational rearrangements that involve the backbone of the protein.

Effect of Phosphorylation on the ps-ns Dynamics

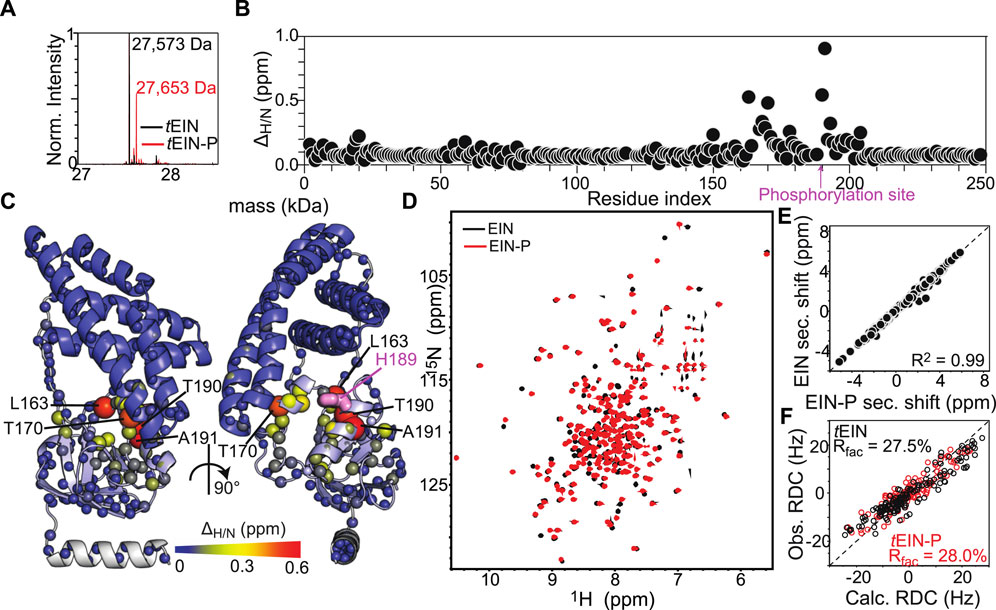

ps-ns timescale dynamics were investigated for eEIN, eEIN-P, tEIN, and tEIN-P using NMR relaxation experiments. NMR samples of eEIN-P were produced as described previously (Suh et al., 2008). Residue-specific 15N-R1 and 15N-R2 values were obtained at 800 MHz and 40°C by acquisition of TROSY-detected R1 and R1ρ experiments (Lakomek et al., 2012) on uniformly 15N-labeled protein. 15N-R2/R1 ratios are graphed as a function of residue index in Figure 3A and depicted as a gradient on the solution structure of tEIN in Figure 3B. For globular diamagnetic proteins, global tumbling is the only significant contribution to 15N relaxation and the R2/R1 values are expected to be constant throughout the amino acid sequence and proportional to the rotational correlation time (

FIGURE 3. Effect of phosphorylation on the ps-ns dynamics of EIN. (A)15N-R2/R1 data measured at 800 MHz and 40°C for tEIN (top), eEIN (second from top), tEINA191S (second from bottom), and eEINS191A (bottom) are plotted vs. the residue index. The unphosphorylated and phosphorylated states are colored black and red, respectively. The localization of linker 1, linker 2, and the C-terminal end are indicated by transparent gray boxes. (B) The 15N-R2/R1 data measured for tEIN are displayed as a gradient on the solution structure of the protein (PDB code: 5WOY) according to the color bar. The His189 side chain is shown as pink sticks.

Effect of Phosphorylation on the μs-ms Dynamics

μs-ms timescale dynamics in eEIN, eEIN-P, tEIN, and tEIN-P were investigated by 15N and 13Cmethyl Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) relaxation dispersion (RD) spectroscopy (Mittermaier and Kay 2006). Experiments were acquired on U-(2H,15N)/Ile (d1)-13CH3/Val, Leu-(13CH3/12C2H3)-labeled samples at two different static fields (600 and 800 MHz) and four different temperatures (5, 10, 15, and 20°C). Simultaneous investigation of RD profiles measured at multiple temperatures returns a comprehensive characterization of the kinetics and thermodynamics of conformational exchange processes between species with distinct chemical shifts occurring on a timescale ranging from ∼0.1 to ∼10 ms, by providing enthalpy (ΔH), entropy (ΔS), activation enthalpy (Δ‡H), and activation entropy (Δ‡S) for the conformational equilibrium (Purslow et al., 2018).

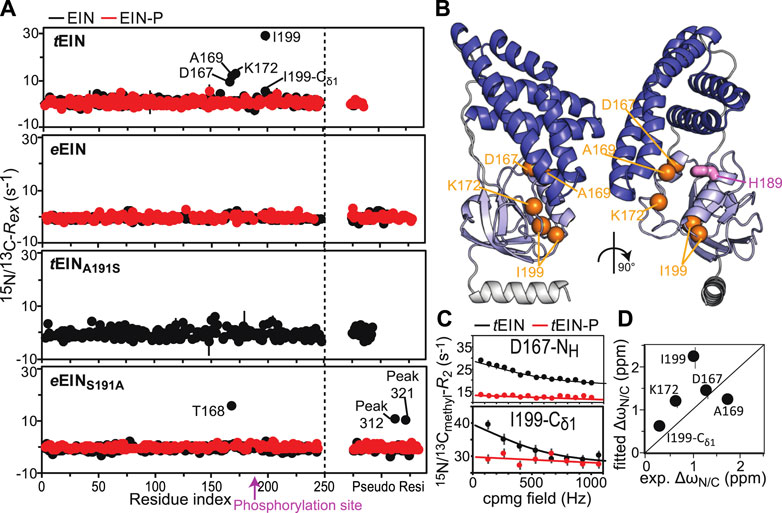

Exchange contributions toward the transverse relaxation rates (Rex) are plotted against residue index in Figure 4A. Large (>5 s−1) Rex values were detected for amino acids that cluster in the vicinity of the active site His189 on the α/β subdomain of tEIN (Figures 4A,B). In particular, Asp167, Ala169, Lys172 localize on the partially structured helix that is in direct contact with His189, while Ile199 is located at the C-terminal end of the short helix that comprises the phosphorylation site. Contrarily, eEIN revealed no significant Rex values (Figure 4A), suggesting the observed dynamics in tEIN may be too fast to be detected by CPMG within its mesophilic analogue. Interestingly, all the 15N and 13Cmethyl RD curves measured at multiple temperatures and static magnetic fields for Asp167, Ala169, Lys172, and Ile199 within tEIN could be fit simultaneously to a model describing the interconversion between two conformational states (Figure 4C; Supplementary Figure 2). In this global fitting procedure, the activation (Δ‡G) and standard (ΔG) free energy of the conformational equilibrium were optimized as global parameters, whereas the 15N and 13C chemical shift differences between the two conformational states (ΔωN and ΔωC, respectively) were treated as peak-specific and temperature independent parameters. The exchange rate (kex) and the fractional population of the minor conformational state (pb) were calculated at each temperature from the fitted values of Δ‡G and ΔG using the general form of the Eyring and reaction isotherm equations, respectively. This fitting procedure reduces the number of optimized parameters from 28 (kex, pb, and Δω for five NMR peaks at four experimental temperatures) to 7 (Δ‡G, ΔG, and Δω for five NMR peaks), and it is justified if the heat capacity of activation remains constant over the experimental temperature range (5–20°C) (Nguyen et al., 2017). For completeness, it should be noted that the intrinsic 15N and 13Cmethyl transverse relaxation rates were also optimized as peak-specific parameters, therefore increasing the overall number of fitted parameters. Also, in order to improve convergence of the fitting algorithm, the ΔωN parameters were restrained to be larger than 1 ppm. Recently we have used a similar fitting protocol to model the temperature dependence of the μs-ms dynamics in the EIC domain of the enzyme (Dotas et al., 2020).

FIGURE 4. Effect of phosphorylation on the μs-ms dynamics for EIN. (A)15N and 13Cmethyl exchange contributions to the transverse relaxation rate (Rex) measured at 10°C and 800 MHz are graphed vs. residue index for tEIN (top), eEIN (second from top), tEINA191S (second from bottom), and eEINS191A (bottom). The unphosphorylated and phosphorylated states are colored black and red, respectively. Unassigned cross-peaks were given arbitrary pseudo residue indexes larger than 300. (B) The NMR correlation showing Rex values larger than 5 s−1 at 10°C and 800 MHz for tEIN are displayed as orange spheres on the solution structure of tEIN (PDB code: 5WOY). The His189 side chain is shown as pink sticks. (C) Examples of typical RD profiles measured at 10°C and 800 MHz for unphosphorylated (black) and phosphorylated (red) tEIN. Data are shown for the Asp167 NH (top) and the Ile199 δ1-methyl (bottom) groups. The experimental data are shown as circles. The best fit curves are shown as lines. The complete set of analyzed data are shown in Supplementary Figure 2. (D) The peak specific ∆ωN and ∆ωC parameters obtained from fitting the RD profiles of tEIN are plotted vs. the change in 15N and 13Cmethyl chemical shift induced by protein phosphorylation. The poor agreement between experimental and fitted ∆ωN observed for Ile199 might be due to the fact that the phosphoryl group is oriented toward this amide group in the phosphorylated enzyme (Figure 1C). Because the RD experiments were acquired on unphosphorylated EIN, the effects on the 15N chemical shift of the electrostatic interactions between the phosphoryl group and the Ile199 backbone amide are not observable in the fitted ∆ωN.

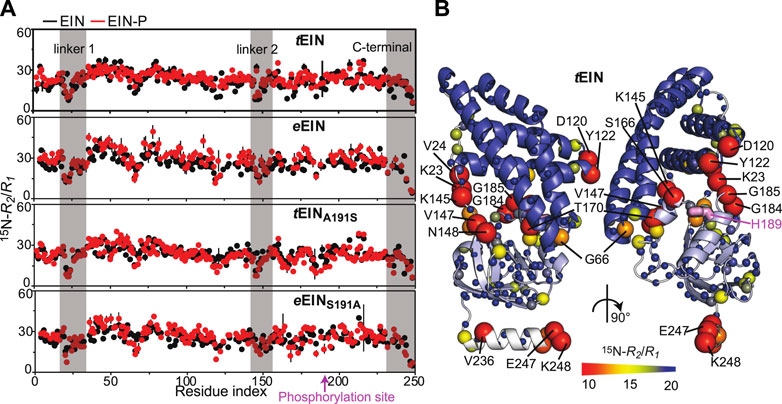

A summary of the optimized parameters is reported in Table 1. Examples of the global fit are provided in Figure 4C. Curves for all the analyzed RD profiles are provided in Supplementary Figure 2. The optimized Δ‡G is 50,228 ± 227J mol−1, which translates into exchange rate constants (sum of forward and backward rate constants, kab and kba, respectively) of 2,117 ± 236, 3,162 ± 347, 4,660 ± 503, and 6,780 ± 719 s−1 at 5, 10, 15, and 20°C, respectively. The optimized ΔG is 5,601 ± 330 J mol−1, resulting in pb values of 8.0 ± 0.4, 8.4 ± 0.4, 8.7 ± 0.4, and 9.0 ± 0.4% at 5, 10, 15, and 20°C, respectively (Table 1). kab and kba were calculated from the values of kex and pb, and their temperature dependence was modeled using the van’t Hoff and Eyring equations to obtain ΔH, ΔS, Δ‡H, and Δ‡S of the tEIN conformational equilibrium (Table 1).

From the analysis of the kinetic, thermodynamic, and NMR parameters obtained by the RD study at multiple temperatures it is apparent that 1) tEIN is in equilibrium between two conformational states, 2) the relative thermodynamic stability of the two states is dictated by enthalpic contributions to the free energy (Table 1), and 3) the 15N and 13C chemical shift differences between the two conformational states correlates with the change in 15N and 13C chemical shift (ΔN and ΔC, respectively) induced by phosphorylation of tEIN (Figure 4D). These findings suggest that the μs-ms dynamics detected in tEIN by RD experiments report on the equilibrium between the g+ and g− rotameric states of His189 that breaks the hydrogen bond between the Thr168 and His189 side-chains and makes the Nε2 atom accessible to the incoming phosphoryl group. Consistent with this hypothesis, the fitted value for ΔH (6 kJ mol−1) is comparable with the reported energies for the weak intramolecular hydrogen bonds involving the hydroxyl group on Ser or Thr side-chains (∼7 kJ mol−1) (Pace et al., 2014a; Pace et al., 2014b).

To further test this model, the effect of phosphorylation on the μs-ms dynamics of tEIN was investigated at 10°C by acquisition of RD experiments on tEIN-P. tEIN-P was prepared enzymatically as described above. However, in this case, tEI, tHPr, and excess PEP were purified out of the final NMR sample by anion exchange chromatography. This additional purification step is required to remove any possible complex between tEIN and other molecules in the sample that, even at very dilute concentrations (<1% of the total tEIN concentration), might cause artifacts in the observed RD profiles (Singh et al., 2021). Since phosphorylated histidine is a labile post-translational modification that decays over the time, the phosphorylation state of the purified tEIN-P sample was checked by 1H-15N TROSY before and after acquisition of the RD experiments at 10°C. Both NMR spectra show no sign of unphosphorylated tEIN cross-peaks, confirming that tEIN remained fully phosphorylated during NMR data acquisition.

As expected, the RD data measured for tEIN-P at 800 MHz shows that phosphorylation completely suppresses μs-ms dynamics within tEIN (Figures 4A,C). Indeed, addition of the bulky phosphoryl group at the Nε2 position hampers formation of the Thr168-His189 hydrogen bond and locks the side-chain of His189 in the g− rotameric state (Figure 1C). It is worth reinstating that no Rex value larger than 5 s−1 was measured for eEIN and, as expected, phosphorylation of eEIN resulted in no observable change in the Rex distribution (Figure 4A). Being that the experimental structures of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated eEIN indicate that the protein must undergo the His189 rotameric transition to accommodate the phosphoryl group (Figure 1C), our data suggests the g+/g− exchange in eEIN is faster than in tEIN and, therefore, not detected by RD experiments.

Engineering eEIN/tEIN Hybrids With Modulated Conformational Dynamics

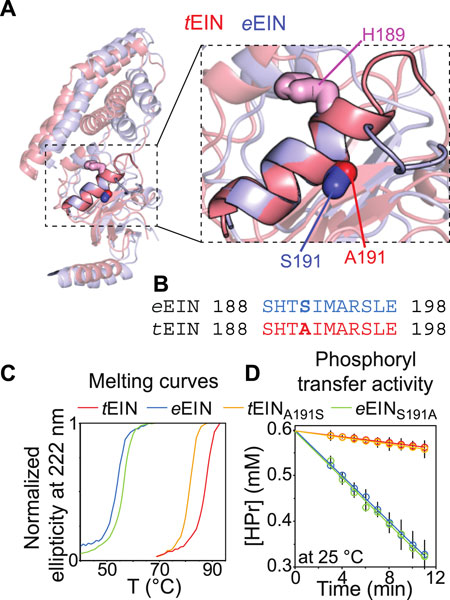

We have recently shown that hybridizing proteins from mesophilic and thermophilic bacteria is an effective strategy to produce active enzymes with modulated conformational dynamics and biological function (Dotas et al., 2020). Indeed, by merging the scaffold of EIC from T. tengcongensis with the active site loops of the E. coli enzyme we engineered a hybrid EIC variant that displays the thermal stability of the thermophilic protein and the high active site flexibility and low-temperature activity of the mesophilic enzyme. In contrast, implanting the active site loops from T. tengcongensis EIC onto the scaffold of E. coli EIC resulted in a construct that is more rigid and less active than the mesophilic enzyme (Dotas et al., 2020). Here, eEIN/tEIN hybrids are engineered to investigate the relationship between the kinetics of the His189 rotameric equilibrium and turnover number. Comparison of the experimental atomic-resolution structures shows that the N-terminal end of α-helix 6 (which comprises the His189) in tEIN is two residues longer than in eEIN (Figure 5A). Alignment of the amino acid sequences reveals a single Ser191Ala mutation within α-helix 6 moving from the mesophilic to the thermophilic construct (Figure 5B; Supplementary Figure 1). As alanine residues are known to promote helix formation in proteins (Panja et al., 2015), we hypothesize that the Ser191Ala mutation provides structural stabilization to α-helix six and is responsible for the slower rotameric equilibrium observed for His189 in tEIN. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the structure, dynamics, and thermal stability of eEINS191A and tEINA191S by solution NMR and circular dichroism (CD).

FIGURE 5. Design and characterization of eEIN/tEIN hybrids. (A) Structure alignment of α-helix 6 in the solution structure of eEIN (PDB code: 2EZA) (blue) and tEIN (PDB code: 5WOY) (red). The side chain of His189 is shown as pink sticks. The side chain of Ser191 in eEIN is shown as blue sticks. The side chain of Ala191 in tEIN is shown as red sticks. (B) Sequence alignment of α-helix 6 in eEIN (blue) and tEIN (red). Full sequence alignment of the mesophilic and thermophilic protein is provided in Supplementary Figure 1. (C) Temperature-induced unfolding of eEIN (blue), eEINS191A (green), tEINA191S (orange), and tEIN (red). (D) Rate of HPr phosphorylation catalyzed by 0.005 μM eEI (blue), eEIS191A (green), tEIA191S (orange), and tEI (red) in the presence of 1 mM PEP at 25°C. The phosphorylation rate (V0) was obtained by linear fitting (solid lines) of the decrease in concentration of unphosphorylated HPr (open circles) vs. time. A V0 of ∼25 μM/min was obtained for eEI and eEIS191A. A V0 of ∼3 μM/min was obtained for tEI and tEIA191S.

Although a comparison of the 1H-15N TROSY spectra measured for the wild type and mutant proteins shows that mutations at the 191 position provides minimal perturbations to the NMR spectra and, therefore, to the solution fold of EIN (Supplementary Figure 3), the temperature-induced unfolding data acquired by CD reveal that the introduced mutations result in sizable and opposing effects on the thermostability of eEIN and tEIN (Figure 5C). In particular, melting temperatures (Tm) of 54.0, 56.5, 82.0, and 88.0°C were determined for eEIN, eEINS191A, tEINA191S, and tEIN from the first derivative of the unfolding sigmoidal curves, respectively. This pattern of Tm values confirms that introducing an Ala residue at position 191 increases the thermal stability of eEIN, while the Ala191Ser mutation results in destabilization of tEIN.

Analysis of the 15N-R2/R1 vs. residue plots reveals a similar pattern for the wild type and mutant proteins, indicating that the introduced mutations do not affect the ps-ns dynamics in native and phosphorylated EIN (Figure 3A). On the other hand, mutations of residue 191 generate observable changes in the μs-ms timescale dynamics of the protein. Indeed, no NMR peak with Rex > 5 s−1 is detected in the NMR spectra of tEINA191S (Figure 4A), which is consistent with the hypothesis that Ala191Ser mutation in tEIN speeds up the rotameric equilibrium of His189. In contrast, the Ser191Ala mutation in eEIN introduces Rex > 5 s−1 at three 1H-15N TROSY correlations. Although we were able to confidently assign only one of these three NMR signals, we ascribe the appearance of exchange induced effects on the spectra of eEINS191A to the rotameric equilibrium of His189 for the following reasons: 1) The assigned NMR correlation with Rex > 5 s−1 (Thr168) localizes in the same region observed to experience exchange contributions to R2 in tEIN (Figure 4A), 2) Global fitting of the RD profiles acquired for the three NMR signals at multiple temperatures and static fields (Supplementary Figure 4) produces kinetic and thermodynamic parameters that are similar to the ones obtained for the His189 rotameric equilibrium in tEIN (Table 1), and 3) Phosphorylation of eEINS191A results in a complete quenching of μs-ms dynamics (Figure 4A).

Overall, the NMR and CD data reported above support the hypothesis that the identity of the residue at position 191 controls helix 6 stability and the dynamics of the g+/g− equilibrium of His189. To test the dependency of the EI biological function on the kinetics of the His189 rotameric transition, the Ser191Ala and Ala191Ser mutations were incorporated into the full-length eEI and tEI, respectively. Then, the ability of eEI, eEIS191A, tEI, and tEIA191S, to transfer the phosphoryl group from PEP to HPr was investigated at 25°C by 1H-15N SOFAST-TROSY spectra, as recently described (Nguyen et al., 2018). As expected, the data indicate that at room temperature eEI catalyzes the phosphoryl transfer reaction ∼10 times faster than tEI (Figure 5D). Interestingly, the Ser191Ala and Ala191Ser mutations produce no detectable changes in the activity of eEI and tEI, respectively (Figure 5D), indicating that the conformational transition from the g+ to g− rotameric state of His189 is not rate limiting for catalysis.

Discussion

Protein conformational transitions are fundamental to signaling, enzyme catalysis, and assembly of cellular structures. Yet, our understanding of how the interconversion among different folded structures affects function continues to lag. One technical challenge limiting our ability to interrogate the dynamics/function relationship is the lack of universal and straightforward strategies to selectively perturb conformational equilibria in complex biomolecular systems. Here, we have shown that it is possible to perturb protein conformational dynamics without dramatically affecting their thermal stability by hybridizing the amino acid sequence of a mesophilic and a thermophilic analogue. In particular, we have investigated the structure and dynamics of the N-terminal domain of EI from a mesophilic (eEIN) and a thermophilic (tEIN) bacterium. We found that the two proteins adopt the same fold and undergo a rotameric equilibrium at the His189 side chain that exposes the phosphorylation site to react with the EI substrate, PEP (Figure 1C). Interestingly, CPMG RD experiments revealed that the rotameric transition in tEIN occurs on a slower time scale than in eEIN (Figure 4A). By comparing the primary structures of the mesophilic and thermophilic proteins (Figures 5A,B) we identified a single point mutation in eEIN (Ser191Ala) and tEIN (Ala191Ser) that swaps the observed kinetics for this conformational change, with the eEINS191A mutant exchanging between the rotameric states of His189at a rate similar to the one measured for the wild type tEIC, and the tEINA191S mutant undergoing the same rotameric equilibrium on a faster time scale, comparable to wild type eEIN (Figure 4, Table 1). Intriguingly, we have recently used the same mesophilic/thermophilic hybridization strategy described here to engineer constructs of the C-terminal domain of EI (EIC) with modulated active site dynamics (Dotas et al., 2020). In contrast to the EIN case that allows for a single-point hybridizing mutation, design of the EIC hybrids required swapping of the entire active site (composed of three catalytic loops) between mesophilic and thermophilic species. Nonetheless, as for the EIN case presented here, the engineering effort resulted in production of two enzymatically active hybrids with mixed properties: One hybrid displayed the high thermal stability of the thermophilic enzyme and the increased active site flexibility and low-temperature activity of the mesophilic analogue; The second hybrid showed the low thermal stability of the mesophilic enzyme and the rigid active site and low activity at room temperature of the thermophilic protein (Dotas et al., 2020). Therefore, hybridizing homologue proteins from mesophilic and thermophilic bacteria is emerging as a powerful tool in biophysics by providing a straightforward approach to produce functional proteins with modulated internal flexibility.

In addition of serving as a demonstration of the mesophilic/thermophilic hybridization strategy for protein design, the EIN constructs engineered here allowed us to investigate the relationship between enzymatic turnover and the kinetics of the His189 rotameric equilibrium. Indeed, by introducing the hybridizing mutations at position 191 into the sequence of the full-length enzyme we have demonstrated that increasing the rate of the g+-to-g− transition of the His189 χ2 angle does not affect turnover for the phosphoryl transfer reaction catalyzed by tEI (Figure 4, Figure 5). Similarly, increasing the activation energy for the His189 rotameric transition in eEI by introducing an Ala residue at position 191 does not affect its enzymatic activity (Figure 4, Figure 5). These results indicate that the His189 conformational change is not rate limiting for catalysis and, therefore, regulation of the EI activity cannot be achieved by slight perturbations of the His189 conformational dynamics.

Finally, it is important to highlight that the data reported in this manuscript show no evidence for an active state A/state B equilibrium in the isolated EIN. This observation implies that the latter equilibrium is either on a timescale that is not compatible with RD experiments (i.e., outside the μs-ms regime) or completely inactive in the isolated EIN domain. Considering that in the full-length dimeric EI transition to state B is required to avoid steric overlap between the EIN and EIC domains, and that state B is structurally stabilized by intersubunit EIN-EIN interactions (Figure 1A), we deduce that state B is inaccessible by the isolated EIN domain investigated here. In any case, our data indicate that the His189g+-to-g− transition that exposes the EI phosphorylation site to PEP (Figure 1C) is decoupled from the EIN state A/state B equilibrium and is not triggered by transition of the full-length enzyme to the catalytically active closed conformation (Figure 1A).

Data Availability Statement

The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: BioMagResBank. Accession number: 50386

Author Contributions

JP, JT, and VV designed the research; JP, JT, VS, TN, RD, and BK, performed the experiments; JP, JT, VS, BK, and VV analyzed the data; JP and VV wrote the article.

Funding

This work was supported by funds from NIGMS R35GM133488 and from the Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust to VV

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marius Clore and Jeong-Yong Suh for providing the resonance assignments of phosphorylated eEIN.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmolb.2021.699203/full#supplementary-material

References

Carver, J. P., and Richards, R. E. (1972). A General Two-Site Solution for the Chemical Exchange Produced Dependence of T2 upon the Carr-Purcell Pulse Separation. J. Magn. Reson. (1969) 6, 89–105. doi:10.1016/0022-2364(72)90090-x

Chauvin, F., Brand, L., and Roseman, S. (1996). Enzyme I: the First Protein and Potential Regulator of the Bacterial Phosphoenolpyruvate: Glycose Phosphotransferase System. Res. Microbiol. 147 (6), 471–479. doi:10.1016/0923-2508(96)84001-0

Clore, G. M., and Garrett, D. S. (1999). R-factor, FreeR, and Complete Cross-Validation for Dipolar Coupling Refinement of NMR Structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 9008–9012. doi:10.1021/ja991789k

Clore, G. M., and Gronenborn, A. M. (1998). Determining the Structures of Large Proteins and Protein Complexes by NMR. Trends Biotechnol. 16 (1), 22–34. doi:10.1016/s0167-7799(97)01135-9

Clore, G. M., and Venditti, V. (2013). Structure, Dynamics and Biophysics of the Cytoplasmic Protein-Protein Complexes of the Bacterial Phosphoenolpyruvate: Sugar Phosphotransferase System. Trends Biochemical Sciences 38 (10), 515–530. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2013.08.003

Delaglio, F., Grzesiek, S., Vuister, G. W., Zhu, G., Pfeifer, J., and Bax, A. (1995). NMRPipe: A Multidimensional Spectral Processing System Based on UNIX Pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6 (3), 277–293. doi:10.1007/bf00197809

Deutscher, J., Aké, F. M. D., Derkaoui, M., Zébré, A. C., Cao, T. N., Bouraoui, H., et al. (2014). The Bacterial Phosphoenolpyruvate:Carbohydrate Phosphotransferase System: Regulation by Protein Phosphorylation and Phosphorylation-dependent Protein-Protein Interactions. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 78 (2), 231–256. doi:10.1128/mmbr.00001-14

Dotas, R. R., Nguyen, T. T., Stewart, C. E., Ghirlando, R., Potoyan, D. A., and Venditti, V. (2020). Hybrid Thermophilic/Mesophilic Enzymes Reveal a Role for Conformational Disorder in Regulation of Bacterial Enzyme I. J. Mol. Biol. 432 (16), 4481–4498. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2020.05.024

Dotas, R. R., and Venditti, V. (2019). Resonance Assignment of the 128 kDa Enzyme I Dimer from Thermoanaerobacter Tengcongensis. Biomol. NMR Assign 13 (2), 287–293. doi:10.1007/s12104-019-09893-y

Doucette, C. D., Schwab, D. J., Wingreen, N. S., and Rabinowitz, J. D. (2011). α-Ketoglutarate Coordinates Carbon and Nitrogen Utilization via Enzyme I Inhibition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7 (12), 894–901. doi:10.1038/nchembio.685

Edelstein, P. H., Edelstein, M. A. C., Higa, F., and Falkow, S. (1999). Discovery of Virulence Genes of Legionella pneumophila by Using Signature Tagged Mutagenesis in a guinea Pig Pneumonia Model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 96 (14), 8190–8195. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.14.8190

Evangelidis, T., Nerli, S., Nováček, J., Brereton, A. E., Karplus, P. A., Dotas, R. R., et al. (2018). Automated NMR Resonance Assignments and Structure Determination Using a Minimal Set of 4D Spectra. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 384. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02592-z

Fitzkee, N. C., and Bax, A. (2010). Facile Measurement of 1H-15N Residual Dipolar Couplings in Larger Perdeuterated Proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 48 (2), 65–70. doi:10.1007/s10858-010-9441-9

Garrett, D. S., Seok, Y. J., Peterkofsky, A., Gronenborn, A. M., and Clore, G. M. (1999). Solution Structure of the 40,000 Mr Phosphoryl Transfer Complex between the N-Terminal Domain of Enzyme I and HPr. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6 (2), 166–173. doi:10.1038/5854

Huang, K.-J., Lin, S.-H., Lin, M.-R., Ku, H., Szkaradek, N., Marona, H., et al. (2013). Xanthone Derivatives Could Be Potential Antibiotics: Virtual Screening for the Inhibitors of Enzyme I of Bacterial Phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent Phosphotransferase System. J. Antibiot. 66 (8), 453–458. doi:10.1038/ja.2013.30

Jones, A. L., Knoll, K. M., and Rubens, C. E. (2000). Identification of Streptococcus Agalactiae Virulence Genes in the Neonatal Rat Sepsis Model Using Signature-Tagged Mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 37 (6), 1444–1455. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02099.x

Kay, L. E., Torchia, D. A., and Bax, A. (1989). Backbone Dynamics of Proteins as Studied by Nitrogen-15 Inverse Detected Heteronuclear NMR Spectroscopy: Application to Staphylococcal Nuclease. Biochemistry 28 (23), 8972–8979. doi:10.1021/bi00449a003

Kok, M., Bron, G., Erni, B., and Mukhija, S. (2003). Effect of Enzyme I of the Bacterial Phosphoenolpyruvate : Sugar Phosphotransferase System (PTS) on Virulence in a Murine Model. Microbiology 149 (9), 2645–2652. doi:10.1099/mic.0.26406-0

Lakomek, N.-A., Ying, J., and Bax, A. (2012). Measurement of 15N Relaxation Rates in Perdeuterated Proteins by TROSY-Based Methods. J. Biomol. NMR 53 (3), 209–221. doi:10.1007/s10858-012-9626-5

Lau, G. W., Haataja, S., Lonetto, M., Kensit, S. E., Marra, A., Bryant, A. P., et al. (2001). A Functional Genomic Analysis of Type 3 Streptococcus Pneumoniae Virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 40 (3), 555–571. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02335.x

Lee, W., Tonelli, M., and Markley, J. L. (2015). NMRFAM-SPARKY: Enhanced Software for Biomolecular NMR Spectroscopy. Bioinformatics 31 (8), 1325–1327. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btu830

Loria, J. P., Rance, M., and Palmer, III, A. G. (1999). A TROSY CPMG Sequence for Characterizing Chemical Exchange in Large Proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 15 (2), 151–155. doi:10.1023/a:1008355631073

Lundström, P., Vallurupalli, P., Religa, T. L., Dahlquist, F. W., and Kay, L. E. (2007). A Single-Quantum Methyl 13C-Relaxation Dispersion experiment with Improved Sensitivity. J. Biomol. NMR 38 (1), 79–88. doi:10.1007/s10858-007-9149-7

Mittermaier, A., and Kay, L. E. (2006). New Tools Provide New Insights in NMR Studies of Protein Dynamics. Science 312 (5771), 224–228. doi:10.1126/science.1124964

Mulder, F. A. A., Schipper, D., Bott, R., and Boelens, R. (1999). Altered Flexibility in the Substrate-Binding Site of Related Native and Engineered High-Alkaline Bacillus Subtilisins 1 1Edited by P. E. Wright. J. Mol. Biol. 292 (1), 111–123. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1999.3034

Mulder, F. A. A., Skrynnikov, N. R., Hon, B., Dahlquist, F. W., and Kay, L. E. (2001). Measurement of Slow (μs−ms) Time Scale Dynamics in Protein Side Chains by15N Relaxation Dispersion NMR Spectroscopy: Application to Asn and Gln Residues in a Cavity Mutant of T4 Lysozyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123 (5), 967–975. doi:10.1021/ja003447g

Navdaeva, V., Zurbriggen, A., Waltersperger, S., Schneider, P., Oberholzer, A. E., Bähler, P., et al. (2011). Phosphoenolpyruvate: Sugar Phosphotransferase System from the HyperthermophilicThermoanaerobacter Tengcongensis. Biochemistry 50 (7), 1184–1193. doi:10.1021/bi101721f

Nguyen, T. T., Ghirlando, R., Roche, J., and Venditti, V. (2021). Structure Elucidation of the Elusive Enzyme I Monomer Reveals the Molecular Mechanisms Linking Oligomerization and Enzymatic Activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2100298118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2100298118

Nguyen, T. T., Ghirlando, R., and Venditti, V. (2018). The Oligomerization State of Bacterial Enzyme I (EI) Determines EI’s Allosteric Stimulation or Competitive Inhibition by α-ketoglutarate. J. Biol. Chem. 293 (7), 2631–2639. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA117.001466

Nguyen, T. T., and Venditti, V. (2020). An Allosteric Pocket for Inhibition of Bacterial Enzyme I Identified by NMR-Based Fragment Screening. J. Struct. Biol. X 4, 100034. doi:10.1016/j.yjsbx.2020.100034

Nguyen, V., Wilson, C., Hoemberger, M., Stiller, J. B., Agafonov, R. V., Kutter, S., et al. (2017). Evolutionary Drivers of Thermoadaptation in Enzyme Catalysis. Science 355 (6322), 289–294. doi:10.1126/science.aah3717

Oberholzer, A. E., Bumann, M., Schneider, P., Bächler, C., Siebold, C., Baumann, U., et al. (2005). Crystal Structure of the Phosphoenolpyruvate-Binding Enzyme I-Domain from the Thermoanaerobacter Tengcongensis PEP: Sugar Phosphotransferase System (PTS). J. Mol. Biol. 346 (2), 521–532. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.077

Pace, C. N., Scholtz, J. M., and Grimsley, G. R. (2014b). Forces Stabilizing Proteins. FEBS Lett. 588 (14), 2177–2184. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2014.05.006

Pace, C. N., Fu, H., Lee Fryar, K., Landua, J., Trevino, S. R., Schell, D., et al. (2014a). Contribution of Hydrogen Bonds to Protein Stability. Protein Sci. 23 (5), 652–661. doi:10.1002/pro.2449

Panja, A. S., Bandopadhyay, B., and Maiti, s. (2015). Protein Thermostability Is Owing to Their Preferences to Non-polar Smaller Volume Amino Acids, Variations in Residual Physico-Chemical Properties and More Salt-Bridges. PLoS One 10 (7), e0131495. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131495

Pervushin, K., Riek, R., Wider, G., and Wüthrich, K. (1998). Transverse Relaxation-Optimized Spectroscopy (TROSY) for NMR Studies of Aromatic Spin Systems in13C-Labeled Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 6394–6400. doi:10.1021/ja980742g

Postma, P. W., Lengeler, J. W., and Jacobson, G. R. (1993). Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate Phosphotransferase Systems of Bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 57 (3), 543–594. doi:10.1128/mmbr.57.3.543-594.1993

Purslow, J. A., Nguyen, T. T., Egner, T. K., Dotas, R. R., Khatiwada, B., and Venditti, V. (2018). Active Site Breathing of Human Alkbh5 Revealed by Solution NMR and Accelerated Molecular Dynamics. Biophysical J. 115 (10), 1895–1905. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2018.10.004

Schanda, P., Kupče, Ē., and Brutscher, B. (2005). SOFAST-HMQC Experiments for Recording Two-Dimensional Deteronuclear Correlation Spectra of Proteins within a Few Seconds. J. Biomol. NMR 33 (4), 199–211. doi:10.1007/s10858-005-4425-x

Schwieters, C. D., Kuszewski, J. J., Tjandra, N., and Marius Clore, G. (2003). The Xplor-NIH NMR Molecular Structure Determination Package. J. Magn. Reson. 160 (1), 65–73. doi:10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9

Schwieters, C. D., Suh, J.-Y., Grishaev, A., Ghirlando, R., Takayama, Y., and Clore, G. M. (2010). Solution Structure of the 128 kDa Enzyme I Dimer fromEscherichia Coliand its 146 kDa Complex with HPr Using Residual Dipolar Couplings and Small- and Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (37), 13026–13045. doi:10.1021/ja105485b

Singh, A., Purslow, J. A., and Venditti, v. (2021). 15N CPMG Relaxation Dispersion for the Investigation of Protein Conformational Dynamics on the μs-ms Timescale. J. Vis. Exp. 170, e62395. doi:10.3791/62395

Suh, J.-Y., Cai, M., and Clore, G. M. (2008). Impact of Phosphorylation on Structure and Thermodynamics of the Interaction between the N-Terminal Domain of Enzyme I and the Histidine Phosphocarrier Protein of the Bacterial Phosphotransferase System. J. Biol. Chem. 283 (27), 18980–18989. doi:10.1074/jbc.m802211200

Teplyakov, A., Lim, K., Zhu, P.-P., Kapadia, G., Chen, C. C. H., Schwartz, J., et al. (2006). Structure of Phosphorylated Enzyme I, the Phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar Phosphotransferase System Sugar Translocation Signal Protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103 (44), 16218–16223. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607587103

Tjandra, N., and Bax, A. (1997). Direct Measurement of Distances and Angles in Biomolecules by NMR in a Dilute Liquid Crystalline Medium. Science 278 (5340), 1111–1114. doi:10.1126/science.278.5340.1111

Tugarinov, V., Hwang, P. M., Ollerenshaw, J. E., and Kay, L. E. (2003). Cross-Correlated Relaxation Enhanced1H−13C NMR Spectroscopy of Methyl Groups in Very High Molecular Weight Proteins and Protein Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125 (34), 10420–10428. doi:10.1021/ja030153x

Tugarinov, V., Venditti, V., and Marius Clore, G. (2014). A NMR experiment for Simultaneous Correlations of Valine and Leucine/isoleucine Methyls with Carbonyl Chemical Shifts in Proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 58 (1), 1–8. doi:10.1007/s10858-013-9803-1

Ulrich, E. L., Akutsu, H., Doreleijers, J. F., Harano, Y., Ioannidis, Y. E., Lin, J., et al. (2008). BioMagResBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 36 (Database issue), D402–D408. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm957

Venditti, V., Tugarinov, V., Schwieters, C. D., Grishaev, A., and Clore, G. M. (2015b). Large Interdomain Rearrangement Triggered by Suppression of Micro- to Millisecond Dynamics in Bacterial Enzyme I. Nat. Commun. 6 (1), 5960. doi:10.1038/ncomms6960

Venditti, V., and Clore, G. M. (2012). Conformational Selection and Substrate Binding Regulate the Monomer/Dimer Equilibrium of the C-Terminal Domain of Escherichia coli Enzyme I. J. Biol. Chem. 287 (32), 26989–26998. doi:10.1074/jbc.m112.382291

Venditti, V., Egner, T. K., and Clore, G. M. (2016). Hybrid Approaches to Structural Characterization of Conformational Ensembles of Complex Macromolecular Systems Combining NMR Residual Dipolar Couplings and Solution X-ray Scattering. Chem. Rev. 116 (11), 6305–6322. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00592

Venditti, V., Ghirlando, R., and Clore, G. M. (2013). Structural Basis for Enzyme I Inhibition by α-Ketoglutarate. ACS Chem. Biol. 8 (6), 1232–1240. doi:10.1021/cb400027q

Venditti, V., Schwieters, C. D., Grishaev, A., and Clore, G. M. (2015a). Dynamic Equilibrium between Closed and Partially Closed States of the Bacterial Enzyme I Unveiled by Solution NMR and X-ray Scattering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112 (37), 11565–11570. doi:10.1073/pnas.1515366112

Keywords: NMR, conformational dynamics, thermophile, protein design, enzyme regulation

Citation: Purslow JA, Thimmesch JN, Sivo V, Nguyen TT, Khatiwada B, Dotas RR and Venditti V (2021) A Single Point Mutation Controls the Rate of Interconversion Between the g+ and g− Rotamers of the Histidine 189 χ2 Angle That Activates Bacterial Enzyme I for Catalysis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 8:699203. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2021.699203

Received: 23 April 2021; Accepted: 29 June 2021;

Published: 08 July 2021.

Edited by:

Silvina Ponce Dawson, University of Buenos Aires, ArgentinaReviewed by:

Felipe Trajtenberg, Institut Pasteur de Montevideo, UruguaySrabani Taraphder, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, India

Copyright © 2021 Purslow, Thimmesch, Sivo, Nguyen, Khatiwada, Dotas and Venditti. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vincenzo Venditti, dmVuZGl0dGlAaWFzdGF0ZS5lZHU=

Jeffrey A. Purslow

Jeffrey A. Purslow Jolene N. Thimmesch1

Jolene N. Thimmesch1 Balabhadra Khatiwada

Balabhadra Khatiwada Vincenzo Venditti

Vincenzo Venditti