94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol., 12 March 2025

Sec. Microorganisms in Vertebrate Digestive Systems

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1562482

This article is part of the Research TopicUnravelling the Wildlife Gut Microbiome: The Crucial Role of Gut Microbiomes in Wildlife Conservation StrategiesView all 4 articles

In recent years, the importance of gut microbiota in digestive absorption, metabolism, and immunity has garnered increasing attention. China possess abundant horse breed resources, particularly Guizhou horses, which play vital roles in local agriculture, tourism, and transportation. Despite this, there is a lack of comparative studies on the gut microbiota of native Guizhou horses (GZH) and imported Dutch Warmblood horses (WH). To address this gap, fecal samples were collected from both GZH and WH, and 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing was utilized to analyze the differences in their gut microbiota. The results indicated that compared with GZH, the abundance of the gut bacterial community in WH was significantly higher, whereas the abundance of the gut fungal community was lower. Furthermore, PCoA-based scatter plot analysis demonstrated distinct differences in the structure of gut bacteria and fungi between the two breeds. While both types of horses share similar major bacterial and fungal phyla, significant differences were observed in numerous bacterial and fungal genera. Moreover, functional predictions of gut bacterial communities suggested that WH exhibit a more robust digestive system and enhanced glycan biosynthesis and metabolism capabilities. This is the first report on the comparative analysis of the gut microbiota in GZH and WH. The results emphasize the significant differences in gut microbiota among various horse breeds and offer valuable insights into the composition and structure of gut microbiota in different horse breeds.

Gut microbiota has gained significant attention in recent years due to its vital roles in host health and physiological functions (Guo et al., 2021; Li S. et al., 2023). Research has shown that gut microbiota is closely associated with nutrient absorption, immune system development, metabolism, and the maintenance of the intestinal mucosal barrier (Bao et al., 2022; Cheng et al., 2019). Moreover, recent studies involving gut microbiota have also revealed its key roles in intestinal epithelial differentiation, skeletal development, and colonization resistance (Beaumont et al., 2022; Zhang Y. et al., 2022). However, the composition and diversity of gut microbiota are influenced by intrinsic characteristics and external factors. Intrinsic characteristics such as gender, age, and species are considered to be the main factors affecting the gut microbial composition and structure (Santos-Marcos et al., 2018). Additionally, external factors, including diet, environmental factors (heavy metals, microplastics, and pesticides), and geographical environment, are the primary driving forces cause gut microbial dysbiosis (Cheng et al., 2021; Meng et al., 2020). Gut microbial dysbiosis is mainly characterized by significant changes in the microbial composition and structure, and it has been demonstrated to be a core or driving factor in various diseases (Du et al., 2023; Jiang et al., 2019). For instance, gastrointestinal-related diseases such as diarrhea, intestinal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, and constipation are often accompanied by gut microbial dysbiosis (Du et al., 2023; Zhuang et al., 2021). Additionally, gut microbial dysbiosis is also considered to be one of the key factors in the occurrence and progression of obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, possibly through pro-inflammatory responses and disruption of intestinal metabolism (de Clercq et al., 2016; Hasain et al., 2020). Gut microbial dysbiosis not only affects intestinal function but can also have systemic negative effects. Therefore, it is crucial to maintain the gut microbial balance to ensure host health and proper intestinal function.

Horses are non-ruminant, odd-toed ungulates, and monogastric herbivorous mammals that have played a significant role in human civilization and social development (Jin et al., 2023). Early investigations have indicated that horses are the oldest domesticated animals, dating back to about 5,500 B.C. Throughout history, humans have selectively bred horses based on social needs, such as appearance, strength, speed, and tolerance, resulting in variations in traits among different horse breeds (Mach et al., 2017). Currently, there are approximately 59 million horses worldwide, encompassing 300 different breeds, with an estimated annual economic impact of around US$300 billion. As a domesticated species vital to humans, horses are bred and utilized globally for purposes such as racing, entertainment, transportation, agricultural production, as well as being important sources of meat and milk in developing countries (Stanislawczyk et al., 2021). In recent years, there has been an increasing demand to selectively breed horses with desirable phenotypic, morphological, and functional characteristics for success in equestrian competition. However, the process of domestication and modern breeding practices have led to a significant reduction in genetic diversity and the accumulation of harmful genetic variations within the equine genome. For instance, domesticated horses exhibit reduced microbial diversity in their gut microbiota compared to wild horses. Therefore, it is crucial to comprehend the biology of horses in order to ensure their well-being and enhance their utilization in human activities.

Presently, high-throughput sequencing technology has been widely used to explore the differences in gut microbiota among different species (Wei et al., 2021). For instance, Massacci et al. (2020) found that the gut microbial diversity and abundance of Hanoverian horses were significantly higher than those of Lusitano horses. Similarly, Park et al. (2021) observed that the gut microbial diversity and the beneficial bacteria producing short-chain fatty acids are significantly higher in Thoroughbred horses compared to Jeju horses. The GZH, a local breed found in southwest China, is known for its short body, delicate appearance, agile movement, and docility. Meanwhile, WH are specifically bred for equestrian competition and possess a range of exceptional characteristics (Wijnberg et al., 2003). Previous research has indicated that the traits of different horse breeds are closely related to gut microbiota in addition to genes. However, there are currently no studies available that explore the gut microbiota of WH and GZH. In this study, we conducted a comparative analysis to examine the differences in the gut bacterial and fungal communities between these two horse breeds.

A total of 8 GZH (about 5 years old) and 8 WH (about 5 years old) were chosen as subjects for this study. Horses within the same group share identical diet and housing environments. Each group consisted of four male horses and four female horses. Health evaluations were performed prior to sampling to minimize the influence of other variables on the gut microbiota. Furthermore, none of the sampled horses had received prior antibiotic injections. Fresh fecal samples were obtained from each horse’s rectum using a fecal sampler and stored at −80°C for further analysis.

For each selected sample from different treatment groups, DNA extraction was performed using commercial kits following the manufacturer’s instructions. The integrity, concentration, and purity of the extracted DNA were tested based on previous studies to ensure that its quality met the requirements for subsequent analysis (Hubert et al., 2019; Park et al., 2021). Additionally, universal primers (338F: ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA and 806R: GGACTACHVGG GTWTCTAAT; ITS5F: GGAAG TAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG and ITS2R: GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGA TGC) were synthesized to amplify the V3/V4 and ITS2 regions. PCR amplification was carried out in triplicate with 20 μL volumes, following the amplification conditions described in previous studies (Guan et al., 2023). The quality of the PCR amplification products was assessed, and the target fragments were then recovered. To prepare sequencing libraries, the recovered products underwent further purification and quantification. The prepared library underwent a series of evaluations, including quality inspection and quantification, to determine its eligibility. Libraries with concentrations greater than 2 nM, no adapters, and only a single peak were considered qualified. The final qualified library was subjected to 2 × 300 bp paired-end sequencing on the MiSeq sequencer.

Some problematic sequences contained in the original sequence include chimeras, low-quality, and short sequences that need to be eliminated to obtain qualified sequences. Specifically, the initial reads produced by amplicon sequencing were first filtered using Trimmomatic v0.33 software. Subsequently, the cutadapt 1.9.1 software was used for identifying and removing the primer sequences to obtain clean reads. Moreover, rarefaction curves and rank abundance curves were generated for each sample in different treatment groups to assess sequencing depth and evenness. High-quality sequences in each sample were clustered into OTUs at 97% similarity. The number of OTUs in different groups or samples was displayed using a Venn diagram. Additionally, we plotted the composition and abundance map of the gut microbial community at different taxonomic levels based on the OTUs analysis results. Microbial alpha diversity indices, such as Chao1, ACE, Shannon, and Simpson, were computed using the number of OTUs in each sample to assess the diversity and abundance of gut microbiota. Beta diversity analysis was also performed to assess changes in the gut microbial structure, and the results were visualized using PCoA scatterplots. Taxa with statistical differences between different treatment groups were identified using Metastats analysis and Lefse analysis. Statistical analysis of data was performed using R (v3.0.3) and GraphPad Prism (version 9.0c). The data were expressed as mean ± SEM, and statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

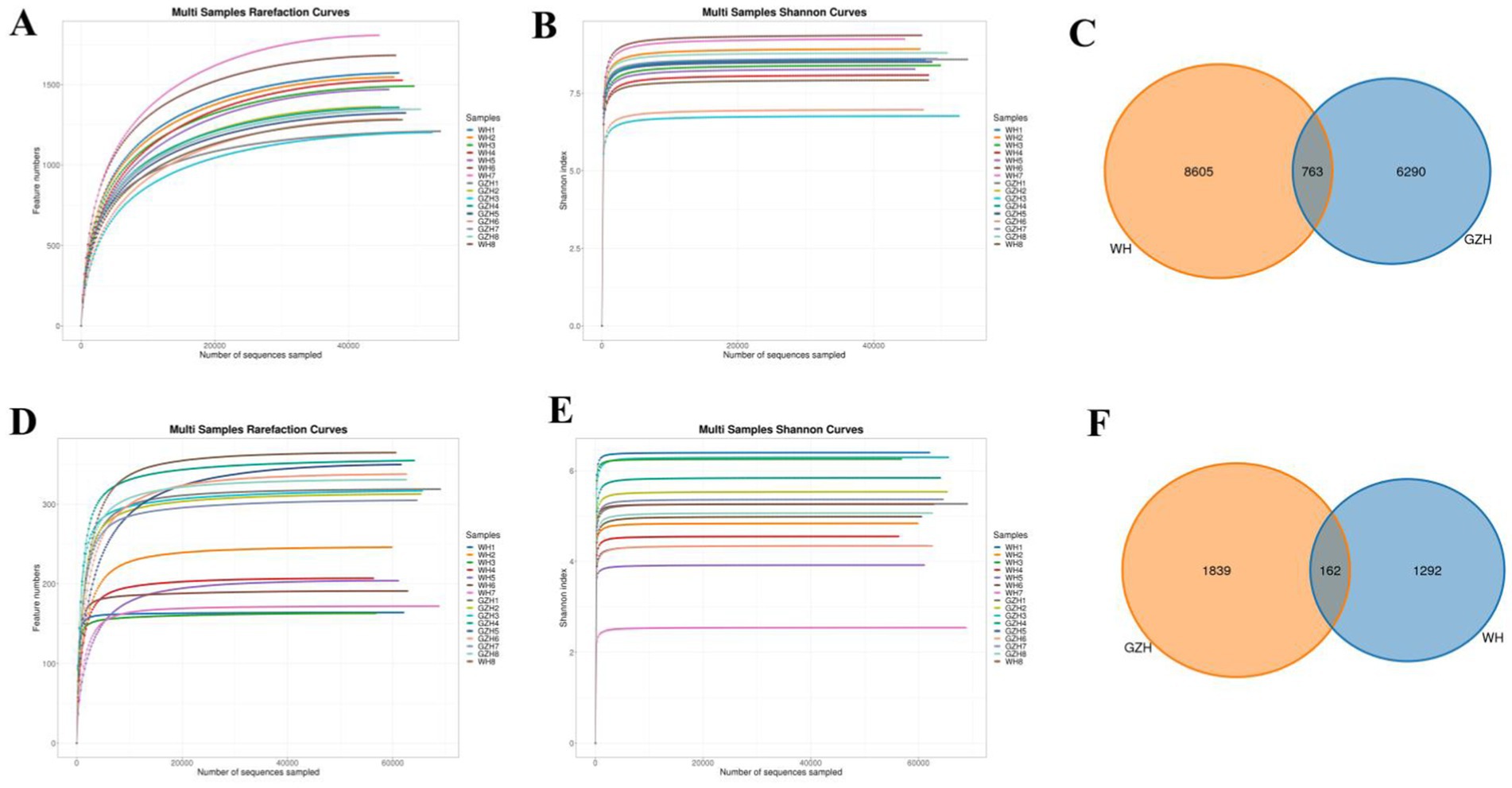

To compare the gut bacterial and fungal communities between GZH and WH, amplicon sequencing was conducted on fecal samples. A total of 1,279,446 original bacterial sequences (Table 1) and 1,279,352 fungal sequences (Table 2) were initially obtained. We also further screened and filtered these raw sequences to obtain valid sequences. Results indicated that 781,011 effective bacterial sequences and 1,004,642 effective fungal sequences were identified, with both exceeding 61 and 78% effectiveness, respectively. Rarefaction curves were utilized to evaluate sequencing depth and uniformity. The findings indicated that further increasing sequencing depth does not lead to the discovery of additional bacterial (Figures 1A,B) and fungal taxa (Figures 1D,E), suggesting that the current sequencing depth and uniformity are adequate. Subsequent clustering of valid sequences resulted in 15,658 bacterial OTUs (Figure 1C) and 3,293 fungal OTUs (Figure 1F). Notably, 763 bacterial OTUs and 162 fungal OTUs were shared between GZH and WH. Moreover, GZH exhibited 6,290 individual bacterial OTUs and 1,839 individual fungal OTUs. In contrast, WH displayed 8,605 individual bacterial OTUs and 1,292 individual fungal OTUs.

Figure 1. OTUs distribution and sequencing data analysis. Gut bacterial (A,B) and fungal (D,E) rarefaction curves evaluate sequencing depth and uniformity. Venn diagram showing the number of shared or individual OTUs of gut gut bacterial (C) and fungal (F) communities in GZH and WH.

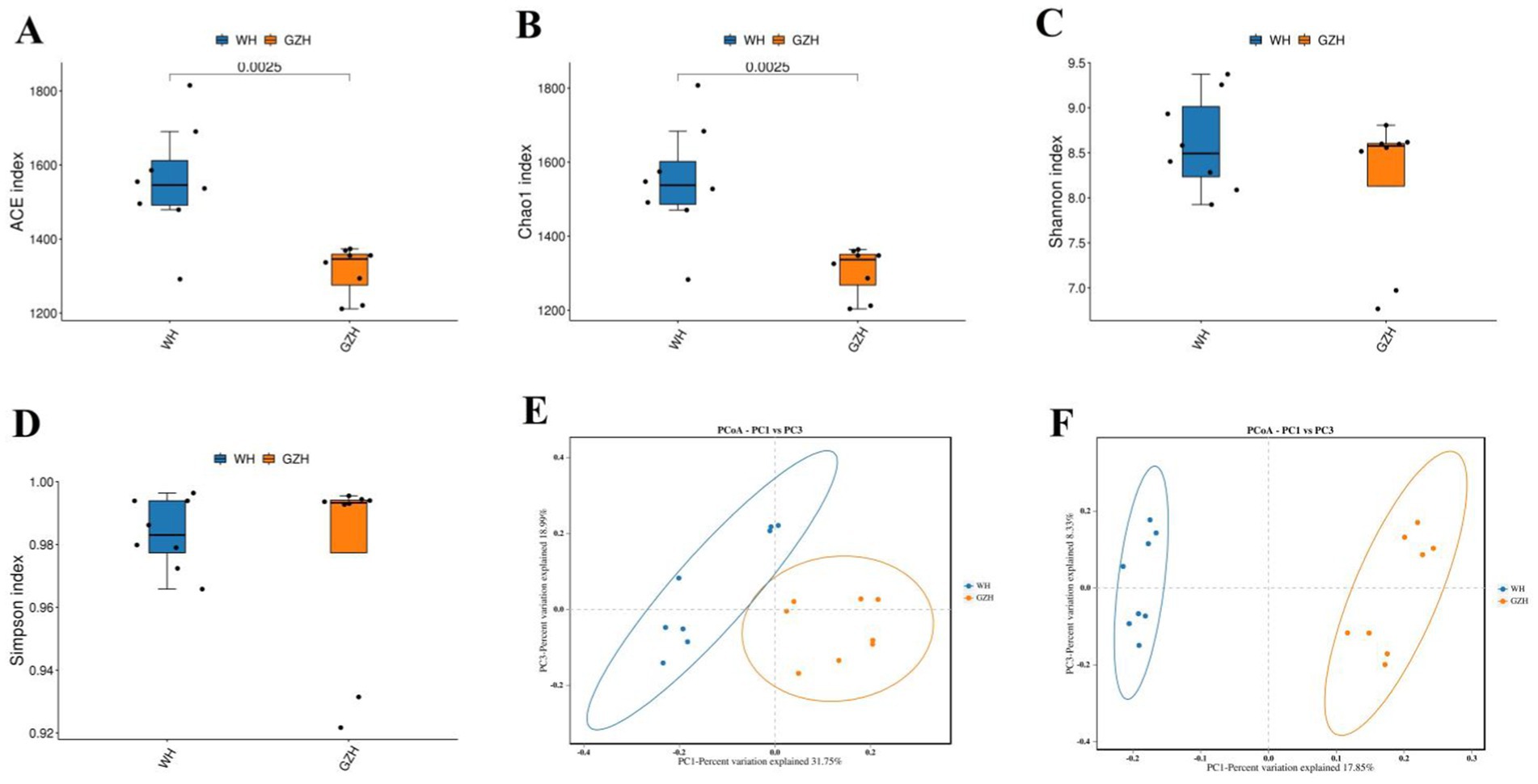

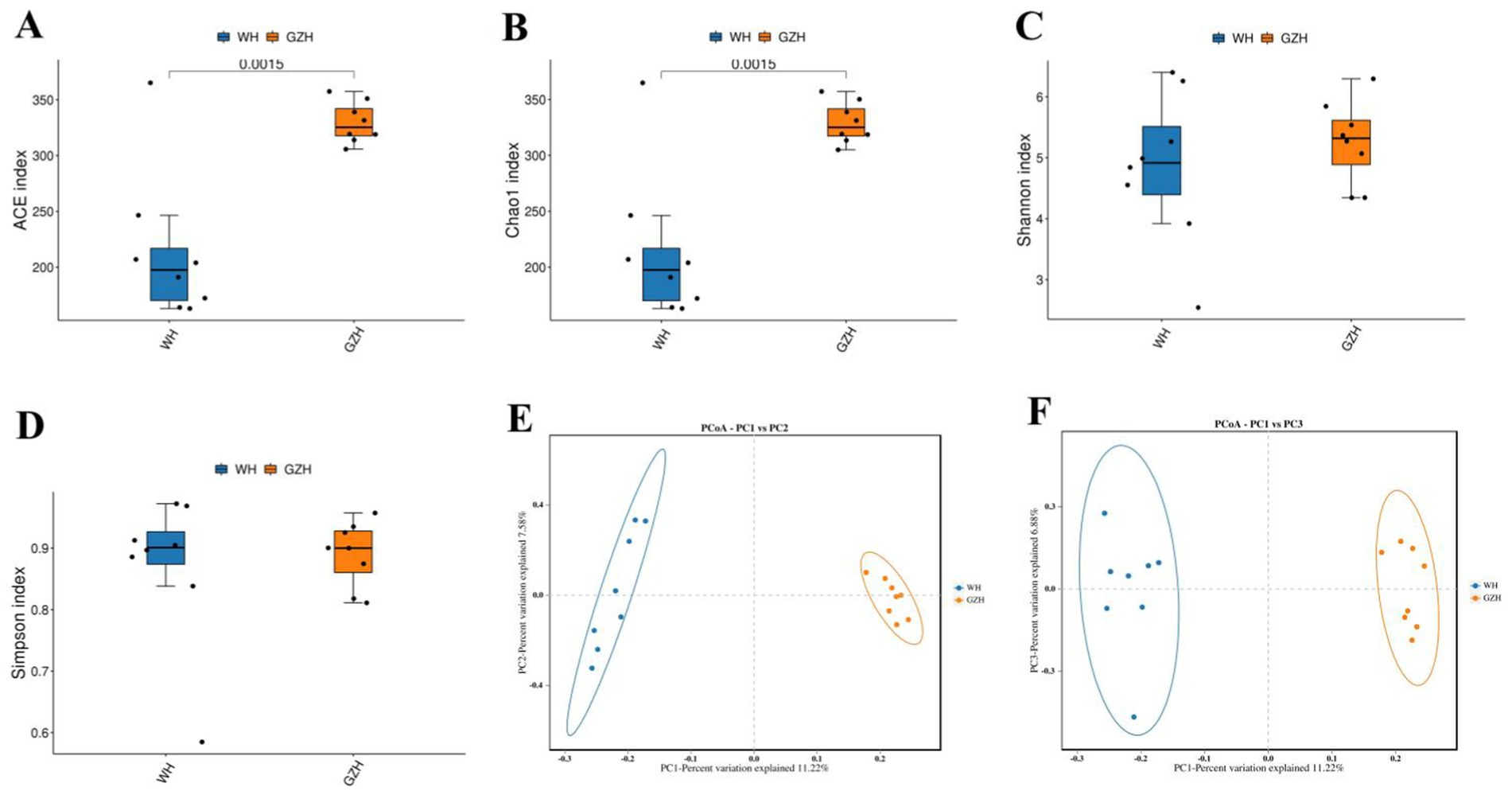

The Chao1, ACE, Simpson, and Shannon indices of the gut bacterial community were determined for GZH and WH. For GZH, the indices were 1305.97, 1314.47, 0.97, and 8.17 (Figures 2A–D), while for WH, the corresponding values were 1548.18, 1556.15, 0.98 and 8.60 (Figures 3A–D). Comparative analysis revealed that the Chao1 and ACE indices of WH were significantly greater than those of GZH, indicating a higher abundance of gut bacterial community in WH. In contrast, the Simpson and Shannon indices did not show significant differences between the two groups, suggesting similar levels of bacterial diversity in both WH and GZH. The Chao1, ACE, Simpson, and Shannon indices of the gut fungal community in GZH were 329.18, 329.63, 0.89, and 5.25, respectively. Conversely, the four diversity indices of the gut fungal community in WH were 214.02, 214.12, 0.87, and 4.84, respectively. Analysis of the gut fungal community revealed that the Chao1 and ACE indices in GZH were significantly higher than those in WH, while the Simpson and Shannon indices did not show a significant difference. This suggests that the abundance of the gut fungal community in GZH was notably higher than in WH, but there was no disparity in fungal diversity between the two groups. To further investigate the changes in gut bacterial and fungal communities between GZH and WH, we conducted a comparative analysis of their structures using PCoA. The PCoA analysis revealed distinct separation between the data points representing GZH and WH, suggesting significant differences in the composition of gut bacterial community (Figures 2E,F). Similarly, the analysis of gut fungal community also demonstrated notable divergence between the two groups (Figures 3E,F).

Figure 2. Boxplots showing the gut bacterial diversity measured as the ACE (A), Chao1 (B), Shannon (C), and Simpson (D) in the GZH and WH. Differences in gut bacterial structure between the GZH and WH were evaluated by PCoA scatter plots (E,F). All the data represent means ± SD. p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Figure 3. Boxplots showing the gut fungal diversity measured as the ACE (A), Chao1 (B), Shannon (C) and Simpson (D) in the GZH and WH. Differences in gut fungal structure between the GZH and WH were evaluated by PCoA scatter plots (E,F). All the data represent means ± SD. p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

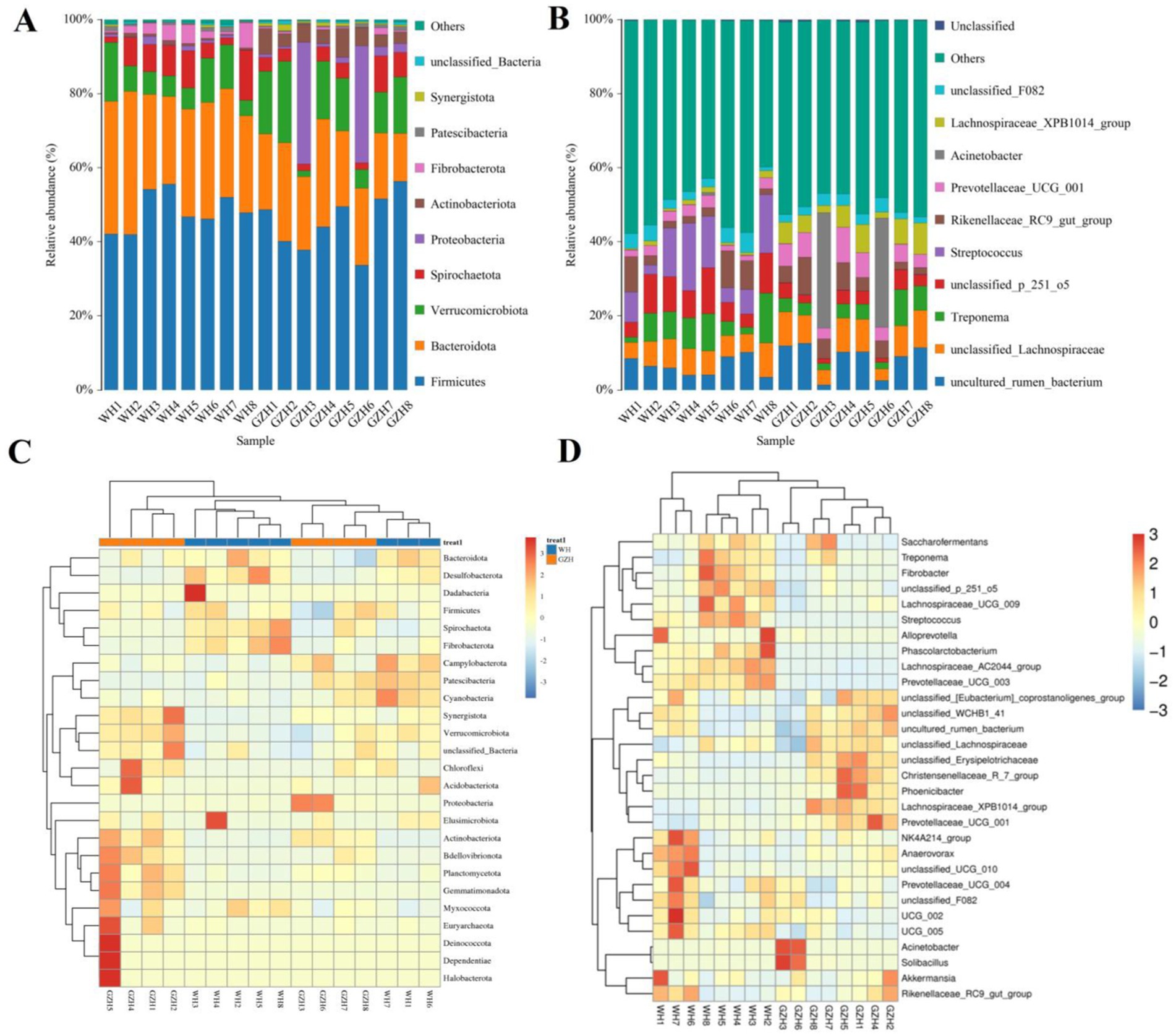

In this study, a total of 25 bacterial phyla and 464 bacterial genera were identified from GZH and WH. At the phylum level, the Firmicutes (45.35, 48.33%), Bacteroidota (20.82, 29.93%), and Verrucomicrobiota (12.60, 8.47%) were the predominant phyla in the GZH and WH (Figure 4A). At the genus level, the Streptococcus (10.34%) was the most predominant bacterial genus in the WH, followed by unclassified_p_251_o5 (7.95%), Treponema (6.77%), and unclassified_Lachnospiraceae (6.50%). Moreover, uncultured_rumen_bacterium (8.61%), Acinetobacter (7.71%), unclassified_Lachnospiraceae (7.52%) and Lachnospiraceae_XPB1014_group (5.35%) were abundantly present in the GZH (Figure 4B). Besides the above dominant bacterial phyla and genera, other bacterial abundance was also analyzed and visualized by clustering heatmaps (Figures 4C,D).

Figure 4. Changes in the relative abundances of bacteria at phylum (A) and genus (B) levels in GZH and WH. The clustering heatmap show the relative proportion and distribution of more bacterial phylum (C) and genus (D).

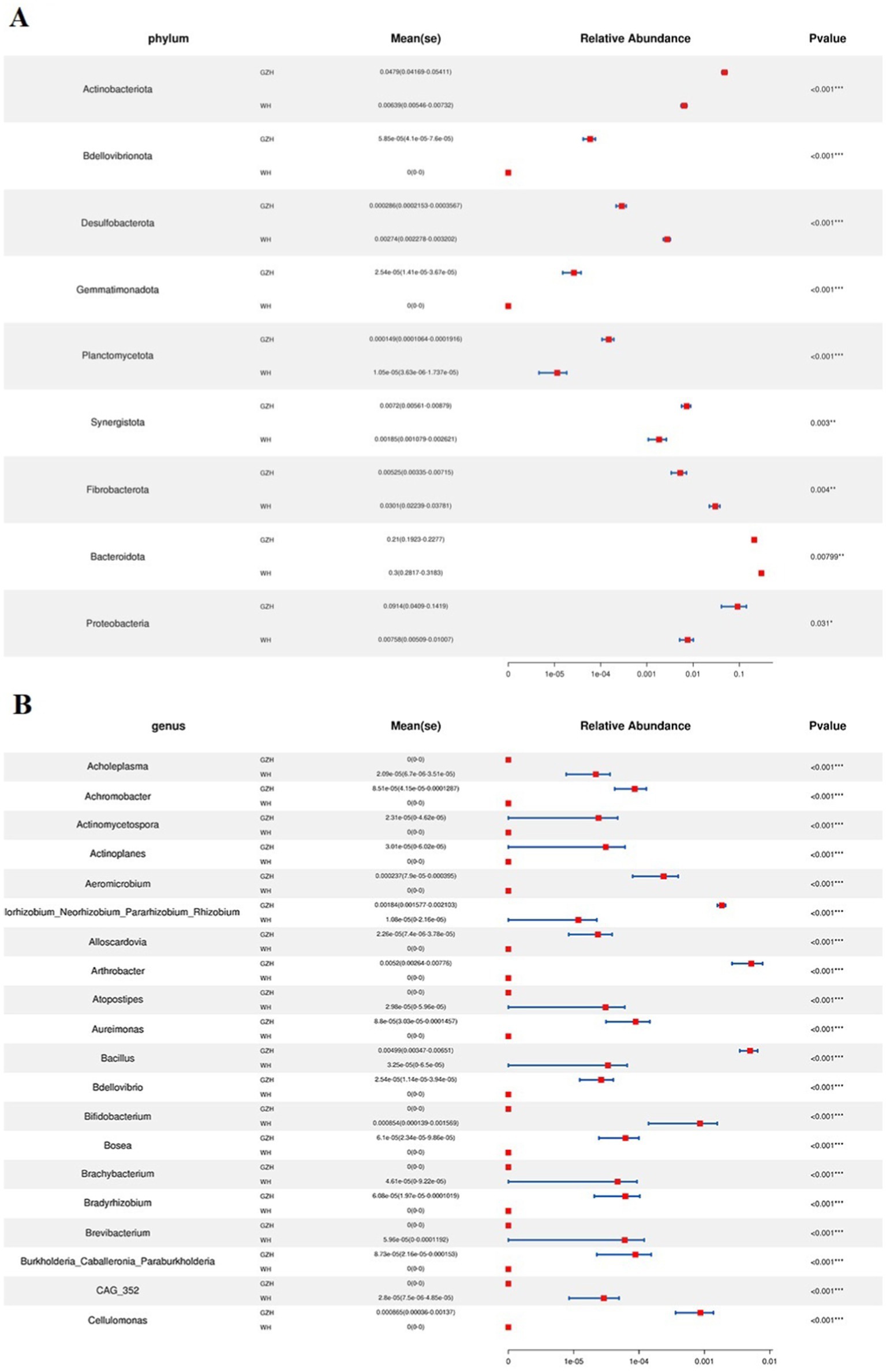

To investigate the difference in gut bacterial community between GZH and WH, we conducted Metastats analysis and LEfSe analysis to identify differential taxa at the phylum and genus levels. At the phylum level, the abundances of Actinobacteriota, Bdellovibrionota, Gemmatimonadota, Planctomycetota, Synergistota and Proteobacteria in the GZH were significantly dominant than WH, while the Desulfobacterota, Fibrobacterota and Bacteroidota were lower (Figure 5A). Furthermore, 217 bacterial genera were significantly different between GZH and WH. Specifically, the abundances of 123 bacterial genera (Achromobacter, Actinomycetospora, Actinoplanes, Aeromicrobium, Bacillus, Bdellovibrio, Bifidobacterium, Christensenellaceae_R_7_group, Lachnospiraceae_XPB1014_group, Lactococcus, Limosilactobacillus, Prevotella_7, Prevotellaceae_UCG_001, Ruminiclostridium, etc.) in GZH was significantly higher than that in WH, while the abundances of 94 bacterial genera (Lachnospiraceae_AC2044_group, Oscillospira, Phascolarctobacterium, Prevotellaceae_UCG_003, Pygmaiobacter, Ruminococcus, Weissella, Anaeroplasma, Papillibacter, Lachnospiraceae_UCG_009, Pseudobutyrivibrio, etc.) was significantly lower than that in WH (Figure 5B). Interestingly, we observed that 92 bacterial genera (Achromobacter, Actinomycetospora, Actinoplanes, Aeromicrobium, Alloscardovia, Bdellovibrio, Chryseobacterium, Curtobacterium, Diplorickettsia, Prevotella_7, Lactococcus, etc.) were only present in GZH, while 46 bacterial genera (Acholeplasma, Atopostipes, Bifidobacterium, Brachybacterium, Brevibacterium, Corynebacterium, Dubosiella, Kurthia, Lachnoclostridium, Lachnospiraceae_NK4B4_group, Lachnospiraceae_UCG_007, etc.) were only present in WH. Moreover, LEfSe analysis results showed that the unclassified_Erysipelotrichaceae and Solibacillus in the gut bacterial community of GZH were significantly higher than those of WH, while the abundances of Streptococcus, unclassified_p_251_o5, and Alloprevotella was lower (Figures 6A,B).

Figure 5. Comparison of gut bacterial community at the phylum (A) and genus (B) level between GZH and WH. Data were not fully shown. All the data represent means ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 6. Differential bacteria at different taxonomic levels related to GZH or WH. (A) Cladogram. (B) LDA scores. Only LDA values >4 can be displayed.

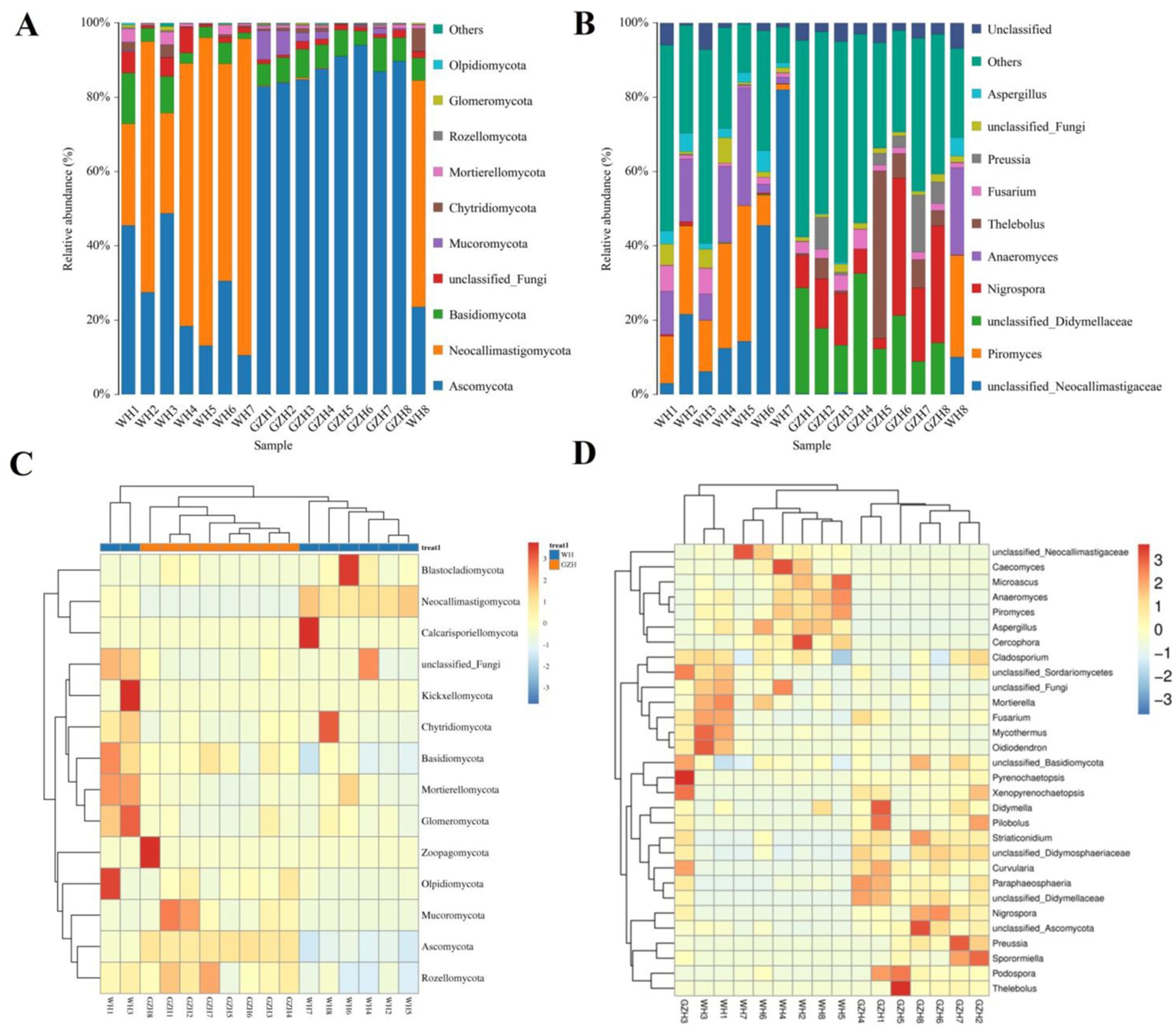

There were 14 fungal phyla and 563 fungal genera found in the gut fungal community of GZH and WH. At the phylum level, the average abundances of 6 fungal phyla including Ascomycota (26.92%), Neocallimastigomycota (60.50%), Basidiomycota (5.74%), unclassified_Fungi (2.84%), Chytridiomycota (1.68%), and Mortierellomycota (1.50%) in the gut fungal community of WH exceeded 1% (Figure 7A). Moreover, the Ascomycota (87.52), Basidiomycota (6.59%), unclassified_Fungi (1.38%) and Mucoromycota (2.68%) were the most dominant phyla, with an average abundance exceeding 1%. At the genus level, the dominant fungi found in WH were unclassified_Neocallimastigaceae (25.60%), Piromyces (18.58%), Anaeromyces (14.18%), unclassified_Fungi (2.84%) and Aspergillus (3.41%) (Figure 7B). Moreover, 6 abundant fungi such as unclassified_Didymellaceae (18.55%), Nigrospora (16.57%), Thelebolus (8.52), Fusarium (2.77%), Preussia (4.60%), and unclassified_Fungi (1.38%) which were defined as containing over 1% in the gut fungal community of GZH. Heatmaps are useful tools for visualizing the abundance and diversity of fungal phyla and genera, enabling researchers to observe changes in these taxonomic groups (Figures 7C,D).

Figure 7. Changes in the relative abundances of fungi at phylum (A) and genus (B) levels in GZH and WH. The clustering heatmap show the relative proportion and distribution of more fungal phylum (C) and genus (D).

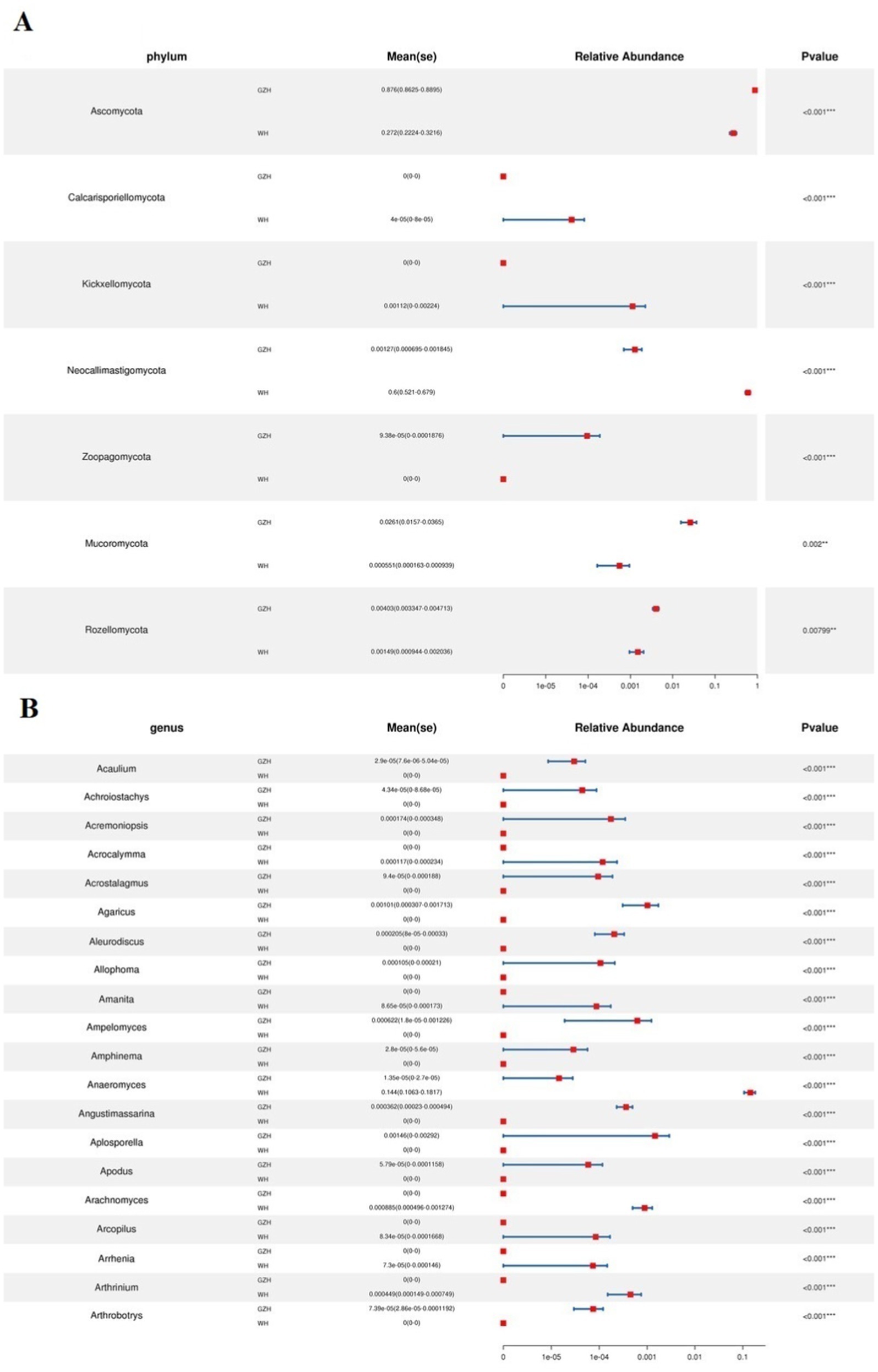

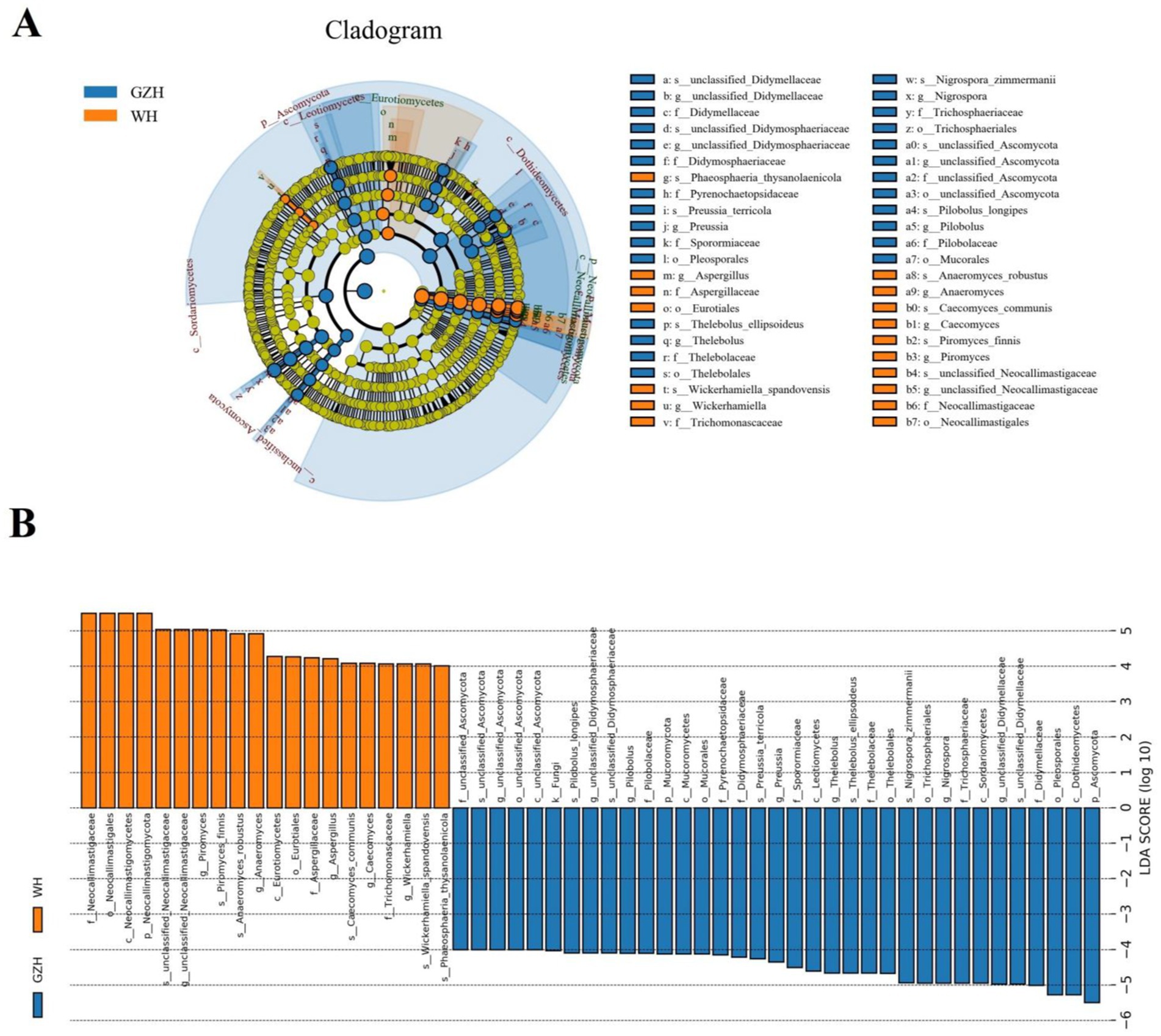

At the phylum level, the abundances of Zoopagomycota, Mucoromycota, Rozellomycota, and Ascomycota in GZH was significantly higher than in WH, whereas the abundances of Calcarisporiellomycota, Kickxellomycota, and Neocallimastigomycota was lower (Figure 8A). Moreover, a total of 365 fungal genera exhibited significant differences between GZH and WH. Specifically, the abundances of 229 fungal genera (Cystobasidium, Nigrospora, Striaticonidium, Ustilago, Xenopyrenochaetopsis, Myxospora, Nemania, Neoascochyta, etc.) in GZH was significantly higher than in WH, while 136 fungal genera (Anaeromyces, Aspergillus, Hohenbuehelia, Hortaea, Hymenula, Lecanicillium, Leucoagaricus, Leucocoprinus, Lophiotrema, etc.) had significantly lower abundance in GZH compared to WH (Figure 8B). Additionally, 127 fungal genera (Acrocalymma, Amanita, Arachnomyces, Arcopilus, Arrhenia, Arthrinium, Arthrocatena, Arxiella, Ascochyta, Ascotricha, Beauveria, Botryosphaeria, Caecomyces, Calcarisporiella, Calycina, ect.) were completely absent in the gut fungal community of GZH. Similarly, 201 fungal genera (Acaulium, Achroiostachys, Acremoniopsis, Acrostalagmus, Agaricus, Aleurodiscus, Allophoma, Ampelomyces, Angustimassarina, Aplosporella, Apodus, Arxotrichum, Ascobolus, etc.) were undetectable in the gut fungal community of WH. The LEfSe analysis and LDA scores were utilized to further elucidate the differences between GZH and WH (Figures 9A,B).

Figure 8. Comparison of gut fungal community at the phylum (A) and genus (B) level between GZH and WH. Data were not fully shown. Data were not fully shown. All the data represent means ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 9. Differential fungi at different taxonomic levels related to GZH or Dutch WH. (A) Cladogram. (B) LDA scores. Only LDA values >4 can be displayed.

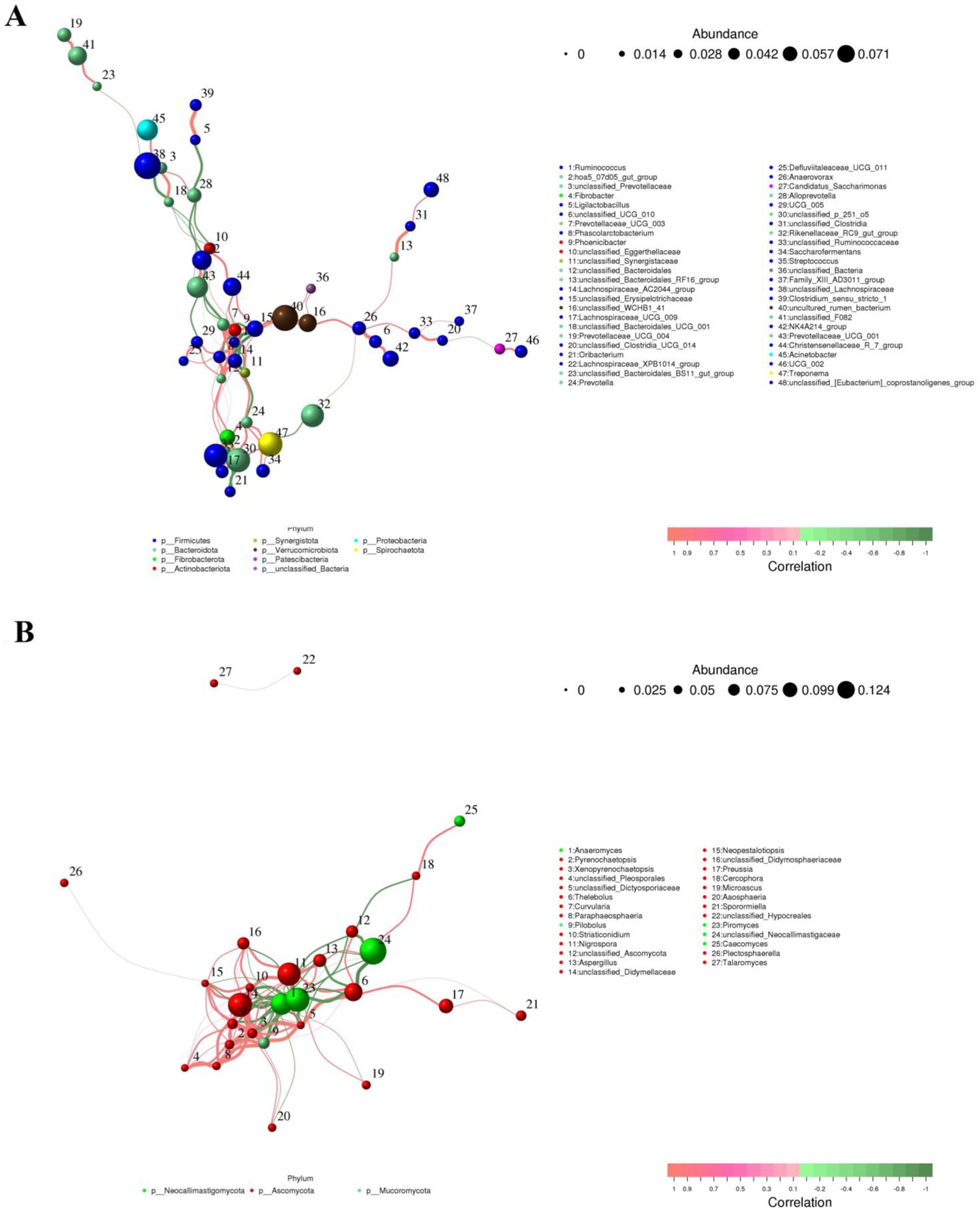

Representative gut bacterial and fungal communities were analyzed using Python to investigate correlations between them. Figure 10 illustrates the direct relationship between select bacteria and fungi. In the gut bacterial community, Ruminococcus showed a positive association with Lachnospiraceae_AC2044_group, Prevotellaceae_UCG_003 (0.87) and Phascolarctobacterium (0.86). However, it was inversely related to Christensenellaceae_R_7_group (−0.75), Phoenicibacter (−0.89), and unclassified_Erysipelotrichaceae (−0.88). Lachnospiraceae_UCG_009 was negatively correlated with Fibrobacter (0.85), Streptococcus (0.80) and unclassified_p_251_o5 (0.80). Prevotella was positively associated with unclassified_p_251_o5 (0.81), Fibrobacter (0.81), Treponema (0.79), Lachnospiraceae_AC2044_group (0.79), Saccharofermentans (0.78) and Saccharofermentans (0.78). Phascolarctobacterium exhibited positive associations with Lachnospiraceae_AC2044_group (0.89), Prevotellaceae_UCG_003 (0.79), Fibrobacter (0.76), and Streptococcus (0.75), while showing an inverse relationship with Phoenicibacter (−0.84).

Figure 10. Co-occurrence networks of bacterial (A) or fungal (B) genera constructed on the WH and GZH. The red line between the both genera represents a positive correlation, whereas the green line indicates a negative correlation.

In the gut fungal community, Xenopyrenochaetopsis showed a positive correlation with Pilobolus (0.95), Curvularia (0.86), unclassified_Didymellaceae (0.83), and Didymella (0.79), but had an inverse relationship with Anaeromyces (−0.85) and Piromyces (−0.83). Neopestalotiopsis exhibited a positive correlation with Xenopyrenochaetopsis (0.92), Aaosphaeria (0.91), Pilobolus (0.87), Striaticonidium (0.86), Curvularia (0.84), unclassified_Didymellaceae (0.83), unclassified_Dictyosporiaceae (0.84), Nigrospora (0.82), Preussia (0.78), Paraphaeosphaeria (0.78), and Thelebolus (0.77), while being inversely related to Anaeromyces (−0.85) and Piromyces (−0.85). Aaosphaeria was positively correlated with Xenopyrenochaetopsis (0.90), Pilobolus (0.90), unclassified_Didymellaceae (0.83), Paraphaeosphaeria (0.79), Thelebolus (0.79), and Striaticonidium (0.78), but had inverse relationships with Anaeromyces (−0.85), Piromyces (−0.85), and Aspergillus (−0.80).

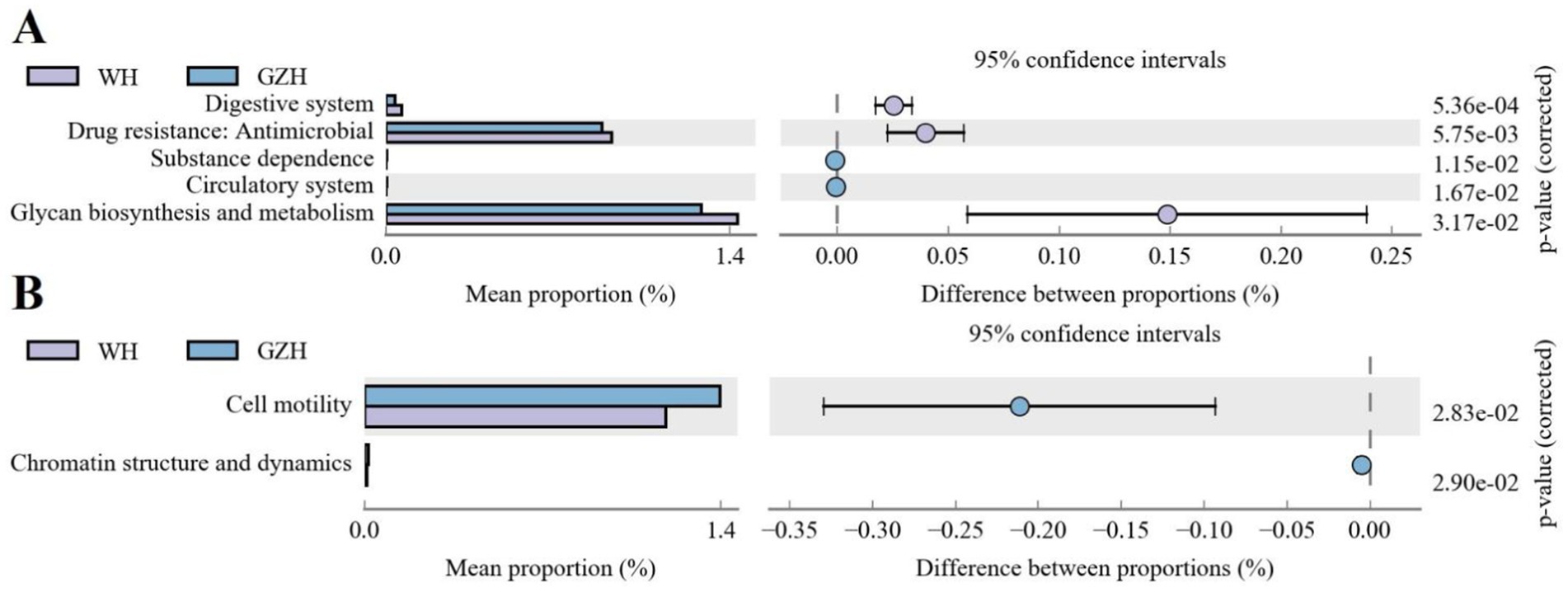

PICRUSt software was utilized to compare the composition of gut microbiota and analyze the functional gene composition and differences between GZH and WH. Gut bacterial KEGG functional prediction analysis showed that the relative abundances of glycan biosynthesis and metabolism, drug resistance: antimicrobial and digestive system were significantly increased in WH, while the substance dependence and circulatory system were decreased as compared to GZH (Figure 11A). In the COG functional prediction analysis, the abundance of cell motility and chromatin structure and dynamics in the GZH was significantly higher than that in WH (Figure 11B).

Figure 11. Functional predictive analysis of gut bacterial community. (A) KEGG metabolic pathway histogram. (B) COG metabolic pathway histogram. All the data represent means ± SD. p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The composition and diversity of gut microbiota are crucial for maintaining intestinal homeostasis and host health (Zhang Z. et al., 2022). Horses, like many other species, harbor a complex gut microbiota that significantly impacts their growth, metabolism, immunity, and digestion (Li et al., 2022; Mach et al., 2020). The gut microbiota of horses has evolved into a delicate balance with the host and the environment as the host has evolved (Di Pietro et al., 2021). However, this balance can be easily influenced by external factors such as dietary structure, environmental conditions, and age (Tizabi et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). Recent studies on various varieties of the same species have also shown significant effects of variety on gut microbiota. For example, Ma et al. (2022) demonstrated significant changes in the gut microbiota of Duroc, Landrace and Yorkshire pigs. Moreover, significant differences in the composition and structure of gut microbiota have also been observed between Kasaragod Dwarf and Holstein crossbred cattle (Deepthi et al., 2023). China possesses a large population of horses and abundant horse breed resources (Yang et al., 2017). GZH are significant horse breeds in China that play a crucial role in local economic development and the livelihoods of residents. Despite this, there has been limited analysis conducted on the comparative study of the gut microbiota of WH and GZH. To address this gap, we collected fecal samples from WH and GZH and conducted 16S rDNA sequencing to investigate the composition and discrepancies in gut microbiota between these two breeds.

Studies have demonstrated significant differences in the composition and structure of gut microbiota among various varieties of the same species (Sun et al., 2021). Different animal species may have developed distinct gut microbiota in response to their specific environments and dietary habits. For instance, wild yaks exhibit a more intricate gut microbiota structure and higher species diversity compared to domestic yaks, reflecting their adaptation to the complex outdoor diet and habitat (Zhu et al., 2023). Similarly, Diqing Tibetan pigs display greater diversity and abundance of gut microbiota than Diannan small ear pigs (Guan et al., 2023). The challenging environment and nutrient scarcity in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau necessitate a diverse gut microbiota in Diqing Tibetan pigs to fulfill their nutritional and energy requirements during growth. These findings indicated the significant influence of species type on gut microbiota. Shannon and Simpson indices are commonly used to evaluate microbial diversity, while Chao1 and ACE indices represent microbial species abundance (Dong et al., 2021). In this study, we found that the Chao1 and ACE indices of gut bacterial community in WH were significantly higher than those in GZH, indicating a higher bacterial abundance in WH. However, the Chao1 and ACE indices of the gut fungal community in GZH was significantly higher than that of WH. Previous research suggests that a higher diversity and abundance of gut microbiota can support more complex intestinal functions like digestion, absorption, metabolism, and immunity (Sun et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2020). GZH and WH may have evolved their own unique gut microbiota to adapt to their surroundings and diet. Moreover, we further explored the differences in intestinal structure between GZH and WH using PCoA analysis. The results showed that the structure of both gut bacterial and fungal communities was significantly different between the two breeds. These results fully demonstrate the differences in gut microbiota between the two types of horses.

Previous studies have demonstrated that Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Ascomycota, and Neocallimastigomycota are the predominant bacterial and fungal components of the gut microbiota, and their members all play crucial roles in intestinal homeostasis and function (Huang et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2022; Zuo and Ng, 2018). It has been reported that the core bacterial and fungal species in mammals are generally stable, with changes primarily occurring in their abundance (Hubert et al., 2019; Li D. et al., 2023). The major bacterial and fungal phyla observed in WH and GZH were consistent, suggesting stability in the composition of these phyla. Furthermore, these phyla are commonly abundant in other mammals like pigs, cattle, and sheep (Kim et al., 2021). Studies have indicated that the members of Firmicutes possesses genes associated with biosynthesis and membrane transport (Singh and Rao, 2021). Furthermore, these members are capable of synthesizing various B vitamins, which are essential for anti-inflammatory properties and enhancing intestinal barrier function (Bellerba et al., 2021). Moreover, the Bacteroidetes has been found to utilize diverse dietary soluble polysaccharides and contains genes responsible for secreting vitamins and coenzymes (Hao et al., 2021). Both Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes are integral in mammalian digestion and nutrient absorption. Studies have shown that the abundance of Firmicutes increases in areas with harsher environments, accompanied by an increase in the proportions of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. In this study, GZH exhibited a higher abundance of Firmicutes compared to WH, while showing lower abundance of Bacteroidetes. This indicates that GZH have higher proportions of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes than WH. These microbial compositions may play a role in aiding GZH in adapting to their intricate local environment and meeting their nutritional requirements.

To further investigate the changes in gut microbiota between GZH and WH, we utilized Metastats and LEfSe analyses to identify distinct bacteria and fungi. We observed that the GZH exhibited richness in Bacillus, Bifidobacterium, Christensenellaceae_R_7_group, Lachnospiraceae_XPB1014_group, Lactococcus, Limosilactobacillus, Prevotella_7, Prevotellaceae_UCG_001, Ruminiclostridium, while the Lachnospiraceae_AC2044_group, Prevotellaceae_UCG_003, Ruminococcus, Weissella, Lachnospiraceae_UCG_009, Lachnospiraceae_UCG_007, and Oscillospira were enriched in the WH. Studies have indicated that Bacillus and Lactococcus can synthesize broad-spectrum antibacterial compounds effective against various pathogenic bacteria (Chu et al., 2019; Horng et al., 2019). Moreover, they are also commonly used as feed additives to help maintain intestinal homeostasis, enhance function, and improve production efficiency (Mazanko et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2021). Christensenellaceae have been found to produce several digestive enzymes associated with feed digestibility, underscoring their significance in growth and development (Tavella et al., 2021). Prevotella and Prevotellaceae are crucial for intestinal digestion and absorption, particularly in breaking down hemicellulose, pectin, and complex carbohydrates (Liu et al., 2018). Bifidobacterium, a prevalent beneficial gut bacterium, offers multiple advantages such as balancing gut microbiota, boosting immunity, and preventing diarrhea (Bo et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2024). Moreover, it produces short-chain fatty acids and antimicrobial peptides that inhibit harmful bacteria and enhance the gut environment (Lim and Shin, 2020). Ruminococcus demonstrates the capacity to generate organic acids, degrade cellulose, and starch (Hong et al., 2022). Research has demonstrated that Ruminiclostridium lowers the occurrence of gastrointestinal issues and is linked to improved growth performance (Ravachol et al., 2015). Lachnospiraceae, recognized as beneficial gut bacteria, have shown an inverse relationship with intestinal inflammation (Huang et al., 2023). Oscillospira can metabolize host glycans to produce butyrate and short-chain fatty acids, suggesting its potential in treating inflammatory bowel disease (Gophna et al., 2017). Weissella has been associated with various health benefits for the host, including enhanced antioxidant capacity, disease resistance, and growth performance, as well as maintaining liver health and reducing fat accumulation (Quintanilla-Pineda et al., 2024). Both GZH and WH harbor different beneficial bacteria, which may may help them achieve their respective complex intestinal functions.

Gut microbiota play a crucial role in substance metabolism, digestion, absorption, mucosal immunity, disease prevention and control, and maintaining the intestinal barrie (Cheng et al., 2018; Li et al., 2024). Bacteria and fungi in the intestine work together to create a complex microbial system through various interactions, ultimately contributing to a range of intestinal functions and maintaining intestinal homeostasis. Thus, we further analyzed the network interactions between different bacteria or fungi and perform functional predictions for the differential bacteria. The results of network interaction analysis of gut microbiota indicate that various bacteria or fungi influence the functions of one another through complex interactions, thus amplifying the effects of different microorganisms on intestinal homeostasis and host health. The functional prediction results of gut microbiota revealed a significantly higher abundance of the digestive system in WH compared to GZH. Increased digestive system abundance may contribute to WH having a more stronger digestive system to achieve complex material digestion and energy needs. Glycans are intricate polymers composed of multiple monosaccharide molecules linked by covalent bonds. They play a crucial role in various biological processes such as development, aging, immune recognition, and cancer (Jian et al., 2020; Purushothaman et al., 2023). Taking glucan as an example, it plays a crucial role in replenishing energy, regulating gut microbiota, enhancing immunity, improving liver function, and aiding in lowering blood sugar levels (Velikonja et al., 2019). The robust glycan biosynthesis and metabolism abilities observed in WH could potentially help in storing energy and maintaining overall host health.

In conclusion, this study delves into the variations in gut bacterial and fungal communities among different horse breeds. The findings reveal notable distinctions in the composition and structure of intestinal microbiota between GZH and WH. Moreover, GZH display higher abundance of gut fungal community, whereas WH showcase stronger digestive systems and glycan biosynthesis and metabolism. This research identifies distinct gut bacterial and fungal communities in both GZH and WH, potentially aiding in their adaptation to specific diets and environments.

The original sequence data was submitted to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) (NCBI, USA) with the accession no. PRJNA1116585.

The animal study was approved by the instructions and approval of Ethics Committee of the Wuhan Business University. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

YLa: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YLi: Writing – review & editing. YW: Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The study was supported by Research project of Wuhan Business College (2024KY020).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Bao, P., Zhang, Z., Liang, Y., Yu, Z., Xiao, Z., Wang, Y., et al. (2022). Role of the gut microbiota in glucose metabolism during heart failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9:903316. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.903316

Beaumont, M., Mussard, E., Barilly, C., Lencina, C., Gress, L., Painteaux, L., et al. (2022). Developmental stage, solid food introduction, and suckling cessation differentially influence the comaturation of the gut microbiota and intestinal epithelium in rabbits. J. Nutr. 152, 723–736. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxab411

Bellerba, F., Muzio, V., Gnagnarella, P., Facciotti, F., Chiocca, S., Bossi, P., et al. (2021). The association between vitamin d and gut microbiota: a systematic review of human studies. Nutrients 13:3378. doi: 10.3390/nu13103378

Bo, T. B., Wen, J., Zhao, Y. C., Tian, S. J., Zhang, X. Y., and Wang, D. H. (2020). Bifidobacterium pseudolongum reduces triglycerides by modulating gut microbiota in mice fed high-fat food. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 198:105602. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105602

Cheng, H. Y., Ning, M. X., Chen, D. K., and Ma, W. T. (2019). Interactions between the gut microbiota and the host innate immune response against pathogens. Front. Immunol. 10:607. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00607

Cheng, Y., Song, W., Tian, H., Zhang, K., Li, B., Du, Z., et al. (2021). The effects of high-density polyethylene and polypropylene microplastics on the soil and earthworm metaphire guillelmi gut microbiota. Chemosphere 267:129219. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.129219

Cheng, J., Xue, F., Zhang, M., Cheng, C., Qiao, L., Ma, J., et al. (2018). Trim 31 deficiency is associated with impaired glucose metabolism and disrupted gut microbiota in mice. Front. Physiol. 9:24. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00024

Chu, J., Wang, Y., Zhao, B., Zhang, X. M., Liu, K., Mao, L., et al. (2019). Isolation and identification of new antibacterial compounds from bacillus pumilus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103, 8375–8381. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-10083-y

de Clercq, N. C., Groen, A. K., Romijn, J. A., and Nieuwdorp, M. (2016). Gut microbiota in obesity and undernutrition. Adv. Nutr. 7, 1080–1089. doi: 10.3945/an.116.012914

Deepthi, M., Arvind, K., Saxena, R., Pulikkan, J., Sharma, V. K., and Grace, T. (2023). Exploring variation in the fecal microbial communities of Kasaragod dwarf and Holstein crossbred cattle. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 116, 53–65. doi: 10.1007/s10482-022-01791-z

Di Pietro, R., Arroyo, L. G., Leclere, M., and Costa, M. C. (2021). Species-level gut microbiota analysis after antibiotic-induced dysbiosis in horses. Animals 11:2859. doi: 10.3390/ani11102859

Dong, Z. X., Chen, Y. F., Li, H. Y., Tang, Q. H., and Guo, J. (2021). The succession of the gut microbiota in insects: a dynamic alteration of the gut microbiota during the whole life cycle of honey bees (apis cerana). Front. Microbiol. 12:513962. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.513962

Du, Z., Li, J., Li, W., Fu, H., Ding, J., Ren, G., et al. (2023). Effects of prebiotics on the gut microbiota in vitro associated with functional diarrhea in children. Front. Microbiol. 14:1233840. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1233840

Gophna, U., Konikoff, T., and Nielsen, H. B. (2017). Oscillospira and related bacteria – from metagenomic species to metabolic features. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 835–841. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13658

Guan, X., Zhu, J., Yi, L., Sun, H., Yang, M., Huang, Y., et al. (2023). Comparison of the gut microbiota and metabolites between diannan small ear pigs and diqing tibetan pigs. Front. Microbiol. 14:1197981. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1197981

Guo, W., Zhou, X., Li, X., Zhu, Q., Peng, J., Zhu, B., et al. (2021). Depletion of gut microbiota impairs gut barrier function and antiviral immune defense in the liver. Front. Immunol. 12:636803. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.636803

Hao, Z., Wang, X., Yang, H., Tu, T., Zhang, J., Luo, H., et al. (2021). Pul-mediated plant cell wall polysaccharide utilization in the gut bacteroidetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22:3077. doi: 10.3390/ijms22063077

Hasain, Z., Mokhtar, N. M., Kamaruddin, N. A., Mohamed, I. N., Razalli, N. H., Gnanou, J. V., et al. (2020). Gut microbiota and gestational diabetes mellitus: a review of host-gut microbiota interactions and their therapeutic potential. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10:188. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00188

Hong, Y. S., Jung, D. H., Chung, W. H., Nam, Y. D., Kim, Y. J., Seo, D. H., et al. (2022). Human gut commensal bacterium ruminococcus species fmb-cy1 completely degrades the granules of resistant starch. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 31, 231–241. doi: 10.1007/s10068-021-01027-2

Horng, Y. B., Yu, Y. H., Dybus, A., Hsiao, F. S., and Cheng, Y. H. (2019). Antibacterial activity of bacillus species-derived surfactin on brachyspira hyodysenteriae and clostridium perfringens. AMB Express 9:188. doi: 10.1186/s13568-019-0914-2

Huang, S., Chen, J., Cui, Z., Ma, K., Wu, D., Luo, J., et al. (2023). Lachnospiraceae-derived butyrate mediates protection of high fermentable fiber against placental inflammation in gestational diabetes mellitus. Sci. Adv. 9:i7337:eadi7337. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adi7337

Huang, Y., Shi, X., Li, Z., Shen, Y., Shi, X., Wang, L., et al. (2018). Possible association of firmicutes in the gut microbiota of patients with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 14, 3329–3337. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S188340

Hubert, S. M., Al-Ajeeli, M., Bailey, C. A., and Athrey, G. (2019). The role of housing environment and dietary protein source on the gut microbiota of chicken. Animals 9:1085. doi: 10.3390/ani9121085

Jian, Y., Xu, Z., Xu, C., Zhang, L., Sun, X., Yang, D., et al. (2020). The roles of glycans in bladder cancer. Front. Oncol. 10:957. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00957

Jiang, J. W., Chen, X. H., Ren, Z., and Zheng, S. S. (2019). Gut microbial dysbiosis associates hepatocellular carcinoma via the gut-liver axis. Hepatob. Pancreatic. Dis. Int. 18, 19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.hbpd.2018.11.002

Jin, Y., Li, W., Ba, X., Li, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, H., et al. (2023). Gut microbiota changes in horses with chlamydia. BMC Microbiol. 23:246. doi: 10.1186/s12866-023-02986-8

Kim, H. S., Whon, T. W., Sung, H., Jeong, Y. S., Jung, E. S., Shin, N. R., et al. (2021). Longitudinal evaluation of fecal microbiota transplantation for ameliorating calf diarrhea and improving growth performance. Nat. Commun. 12:161. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20389-5

Li, Y., Lan, Y., Zhang, S., and Wang, X. (2022). Comparative analysis of gut microbiota between healthy and diarrheic horses. Front. Vet. Sci. 9:882423. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.882423

Li, Z., Xiong, W., Liang, Z., Wang, J., Zeng, Z., Kolat, D., et al. (2024). Critical role of the gut microbiota in immune responses and cancer immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 17:33. doi: 10.1186/s13045-024-01541-w

Li, D., Yang, H., Li, Q., Ma, K., Wang, H., Wang, C., et al. (2023). Prickly ash seeds improve immunity of hu sheep by changing the diversity and structure of gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 14:1273714. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1273714

Li, S., Zhu, S., and Yu, J. (2023). The role of gut microbiota and metabolites in cancer chemotherapy. J. Adv. Res. 64, 223–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2023.11.027

Lim, H. J., and Shin, H. S. (2020). Antimicrobial and immunomodulatory effects of bifidobacterium strains: a review. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 30, 1793–1800. doi: 10.4014/jmb.2007.07046

Liu, X., Fan, P., Che, R., Li, H., Yi, L., Zhao, N., et al. (2018). Fecal bacterial diversity of wild Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys (rhinopithecus roxellana). Am. J. Primatol. 80:e22753. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22753

Ma, J., Chen, J., Gan, M., Chen, L., Zhao, Y., Zhu, Y., et al. (2022). Gut microbiota composition and diversity in different commercial swine breeds in early and finishing growth stages. Animals 12:1607. doi: 10.3390/ani12131607

Mach, N., Foury, A., Kittelmann, S., Reigner, F., Moroldo, M., Ballester, M., et al. (2017). The effects of weaning methods on gut microbiota composition and horse physiology. Front. Physiol. 8:535. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00535

Mach, N., Ruet, A., Clark, A., Bars-Cortina, D., Ramayo-Caldas, Y., Crisci, E., et al. (2020). Priming for welfare: gut microbiota is associated with equitation conditions and behavior in horse athletes. Sci. Rep. 10:8311. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-65444-9

Massacci, F. R., Clark, A., Ruet, A., Lansade, L., Costa, M., and Mach, N. (2020). Inter-breed diversity and temporal dynamics of the faecal microbiota in healthy horses. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 137, 103–120. doi: 10.1111/jbg.12441

Mazanko, M. S., Popov, I. V., Prazdnova, E. V., Refeld, A. G., Bren, A. B., Zelenkova, G. A., et al. (2022). Beneficial effects of spore-forming bacillus probiotic bacteria isolated from poultry microbiota on broilers' health, growth performance, and immune system. Front. Vet. Sci. 9:877360. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.877360

Meng, Z., Liu, L., Yan, S., Sun, W., Jia, M., Tian, S., et al. (2020). Gut microbiota: a key factor in the host health effects induced by pesticide exposure? J. Agric. Food Chem. 68, 10517–10531. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c04678

Park, T., Yoon, J., Kim, A., Unno, T., and Yun, Y. (2021). Comparison of the gut microbiota of jeju and thoroughbred horses in Korea. Vet. Sci. 8:81. doi: 10.3390/vetsci8050081

Purushothaman, A., Mohajeri, M., and Lele, T. P. (2023). The role of glycans in the mechanobiology of cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 299:102935. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.102935

Quintanilla-Pineda, M., Ibanez, F. C., Garrote-Achou, C., and Marzo, F. (2024). A novel postbiotic product based on Weissella cibaria for enhancing disease resistance in rainbow trout: aquaculture application. Animals 14:744. doi: 10.3390/ani14050744

Ravachol, J., Borne, R., Meynial-Salles, I., Soucaille, P., Pages, S., Tardif, C., et al. (2015). Combining free and aggregated cellulolytic systems in the cellulosome-producing bacterium ruminiclostridium cellulolyticum. Biotechnol. Biofuels 8:114. doi: 10.1186/s13068-015-0301-4

Santos-Marcos, J. A., Rangel-Zuniga, O. A., Jimenez-Lucena, R., Quintana-Navarro, G. M., Garcia-Carpintero, S., Malagon, M. M., et al. (2018). Influence of gender and menopausal status on gut microbiota. Maturitas 116, 43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.07.008

Singh, V., and Rao, A. (2021). Distribution and diversity of glycocin biosynthesis gene clusters beyond firmicutes. Glycobiology 31, 89–102. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwaa061

Stanislawczyk, R., Rudy, M., Gil, M., Duma-Kocan, P., and Zurek, J. (2021). Influence of horse age, marinating substances, and frozen storage on horse meat quality. Animals 11:2666. doi: 10.3390/ani11092666

Sun, F., Chen, J., Liu, K., Tang, M., and Yang, Y. (2022). The avian gut microbiota: diversity, influencing factors, and future directions. Front. Microbiol. 13:934272. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.934272

Sun, B., Hou, L., and Yang, Y. (2021). Effects of adding eubiotic lignocellulose on the growth performance, laying performance, gut microbiota, and short-chain fatty acids of two breeds of hens. Front. Vet. Sci. 8:668003. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.668003

Tavella, T., Rampelli, S., Guidarelli, G., Bazzocchi, A., Gasperini, C., Pujos-Guillot, E., et al. (2021). Elevated gut microbiome abundance of christensenellaceae, porphyromonadaceae and rikenellaceae is associated with reduced visceral adipose tissue and healthier metabolic profile in Italian elderly. Gut Microbes 13, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1880221

Tizabi, Y., Bennani, S., El, K. N., Getachew, B., and Aschner, M. (2023). Interaction of heavy metal lead with gut microbiota: implications for autism spectrum disorder. Biomol. Ther. 13:1549. doi: 10.3390/biom13101549

Velikonja, A., Lipoglavsek, L., Zorec, M., Orel, R., and Avgustin, G. (2019). Alterations in gut microbiota composition and metabolic parameters after dietary intervention with barley beta glucans in patients with high risk for metabolic syndrome development. Anaerobe 55, 67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2018.11.002

Wang, S., Wang, L., Fan, X., Yu, C., Feng, L., and Yi, L. (2020). An insight into diversity and functionalities of gut microbiota in insects. Curr. Microbiol. 77, 1976–1986. doi: 10.1007/s00284-020-02084-2

Wang, Z., Zeng, X., Zhang, C., Wang, Q., Zhang, W., Xie, J., et al. (2022). Higher niacin intakes improve the lean meat rate of ningxiang pigs by regulating lipid metabolism and gut microbiota. Front. Nutr. 9:959039. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.959039

Wei, X., Bottoms, K. A., Stein, H. H., Blavi, L., Bradley, C. L., Bergstrom, J., et al. (2021). Dietary organic acids modulate gut microbiota and improve growth performance of nursery pigs. Microorganisms 9:110. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9010110

Wijnberg, I. D., Franssen, H., and van der Kolk, J. H. (2003). Influence of age of horse on results of quantitative electromyographic needle examination of skeletal muscles in Dutch warmblood horses. Am. J. Vet. Res. 64, 70–75. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2003.64.70

Yang, Y., Zhu, Q., Liu, S., Zhao, C., and Wu, C. (2017). The origin of Chinese domestic horses revealed with novel mtdna variants. Anim. Sci. J. 88, 19–26. doi: 10.1111/asj.12583

Zhang, J., Liang, X., Tian, X., Zhao, M., Mu, Y., Yi, H., et al. (2024). Bifidobacterium improves oestrogen-deficiency-induced osteoporosis in mice by modulating intestinal immunity. Food Funct. 15, 1840–1851. doi: 10.1039/d3fo05212e

Zhang, S., Shen, Y., Wang, S., Lin, Z., Su, R., Jin, F., et al. (2023). Responses of the gut microbiota to environmental heavy metal pollution in tree sparrow (passer montanus) nestlings. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 264:115480. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.115480

Zhang, Y., Tan, P., Zhao, Y., and Ma, X. (2022). Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli: intestinal pathogenesis mechanisms and colonization resistance by gut microbiota. Gut Microbes 14:2055943. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2022.2055943

Zhang, Z., Tanaka, I., Pan, Z., Ernst, P. B., Kiyono, H., and Kurashima, Y. (2022). Intestinal homeostasis and inflammation: gut microbiota at the crossroads of pancreas-intestinal barrier axis. Eur. J. Immunol. 52, 1035–1046. doi: 10.1002/eji.202149532

Zhang, N., Wang, L., and Wei, Y. (2021). Effects of Bacillus pumilus on growth performance, immunological indicators and gut microbiota of mice. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 105, 797–805. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13505

Zhu, Y., Cidan, Y., Sun, G., Li, X., Shahid, M. A., Luosang, Z., et al. (2023). Comparative analysis of gut fungal composition and structure of the yaks under different feeding models. Front. Vet. Sci. 10:1193558. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2023.1193558

Zhuang, X., Liu, C., Zhan, S., Tian, Z., Li, N., Mao, R., et al. (2021). Gut microbiota profile in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Front. Pediatr. 9:626232. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.626232

Keywords: gut microbiota, horse, bacteria, fungi, PCoA, abundance

Citation: Lan Y, Li Y and Wang Y (2025) Microbiome analysis reveals dynamic changes of gut microbiota in Guizhou horse and Dutch Warmblood horses. Front. Microbiol. 16:1562482. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1562482

Received: 17 January 2025; Accepted: 19 February 2025;

Published: 12 March 2025.

Edited by:

Li Tang, Sichuan Agricultural University, ChinaReviewed by:

Tariq Jamil, Friedrich Loeffler Institut, GermanyCopyright © 2025 Lan, Li and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yaonan Li, NTY5NzgwOTU3QHFxLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.