94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 13 March 2025

Sec. Antimicrobials, Resistance and Chemotherapy

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1537229

This article is part of the Research Topic Emerging Antimicrobials: Sources, Mechanisms of Action, Spectrum of Activity, Combination Antimicrobial Therapy, and Resistance Mechanisms View all 17 articles

Background: Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) constitute a significant health challenge, particularly among immunocompromised individuals, characterized by a high prevalence and associated mortality rates. The synergistic administration of Baicalein (BE) with azole antifungal agents could potentially herald a novel therapeutic paradigm.

Materials and methods: 54 Aspergillus strains and 23 strains of dematiaceous fungi were selected. The standard M38-A2 microbroth dilution method was used to test the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) of fungi when BE combined with itraconazole (ITC), voriconazole (VRC), posaconazole (POS) and Isavuconazole (ISV).

Results: BE shows synergistic effects with POS and ITC, with 89.61% and 25.97% of fungal strains. The BE/POS regimen exerted synergistic effects in 87.04% of Aspergillus and an impressive 95.65% of dematiaceous fungi. In comparison, the BE/ITC combination showed significantly lower synergy, affecting 33.33% of Aspergillus and a mere 8.70% of dematiaceous strains. Antagonistic interactions were sporadically observed with BE in combination with ITC, VRC, POS and ISV. Within the azole class, the BE/POS pairing stood out for its frequent synergistic activity, in contrast to the absence of such effects when BE was paired with VRC or ISV. Highlighting the potential of BE/POS as a notably effective antifungal strategy.

Conclusion: In vitro, BE/POS combination emerged as the most effective antifungal strategy, exhibiting synergistic effects in the majority of Aspergillus and dematiaceous fungi strains, whereas BE/ITC showed significantly less synergy, and BE with VRC or ISV displayed no synergistic activity.

Invasive fungal infections (IFIs) are a serious type of infectious disease, with higher incidence and mortality rates particularly among patients with immunosuppression or immunodeficiency (Fang et al., 2023). Aspergillus species are the main pathogens most frequently isolated from patients with compromised immune function (Badiee and Hashemizadeh, 2014; Pfaller et al., 2021). Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus flavus are known to be pathogenic, while Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus terreus are also capable of causing invasive infections (Balajee, 2009; Borni et al., 2024; Hedayati et al., 2007; Morelli et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2024). Dematiaceous fungi, including Exophiala dermatitidis and Exophiala alcalophila, can cause a variety of infections in immunocompromised individuals (Kirchhoff et al., 2019; Kondori et al., 2024; Revankar, 2007). Azoles have become the mainstay of treatment and prevention for many systemic mycoses, with common medications including ITC, VRC, POS and ISV (Kaushik and Kest, 2018; Peyton et al., 2015). Because of their high infection and mortality rates in immunocompromised patients, as well as the increasing resistance to azole antifungal agents, studying Aspergillus and dematiaceous fungi can help explore their resistance mechanisms and provide a theoretical basis for the development of new combination therapeutic strategies (Amona et al., 2022; Djenontin et al., 2023; Puerta-Alcalde and Garcia-Vidal, 2021). Previous research has demonstrated that synergistic combinations of natural products can augment antifungal potency, which may facilitate the discovery of innovative therapeutic approaches to combat fungal infections (Augostine and Avery, 2022; Yang et al., 2023). A wide range of natural flavonoids have been shown to possess antifungal properties (Jin, 2019). Baicalein (BE) is a flavonoid compound widely found in the Scutellaria genus of plants, featuring hydroxyl groups that contribute to its bioactivity (Zhao et al., 2022). Previous studies have confirmed its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant properties, as well as anti-cancer and tumor cell proliferation inhibition effects, while recent research has highlighted the potential antifungal activity of BE (Gupta et al., 2022; Lai et al., 2024; Li Y. Y. et al., 2022; Song et al., 2021; Tuli et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2018). BE exhibits potent antifungal activity against Candida species, with a MIC50 as low as 13 μg/mL, and has been proven to inhibit the growth of Candida through multiple mechanisms, such as targeting and inhibiting the function of enolase 1 (Eno1) in Candida albicans, upregulating the expression of CPD2, and inducing apoptosis by targeting ribosomes in Candida auris (Da et al., 2019; Li et al., 2024; Li L. et al., 2022; Lv et al., 2022; Serpa et al., 2012). In contrast, the effects of BE on Aspergillus and dark-coloured fungi have been less studied. Notably, BE at a concentration of 0.25 mM has been demonstrated to ameliorate Aspergillus fumigatus keratitis in mice (Zhu et al., 2021). BE has been shown to exhibit synergistic effects with other antifungal agents, such as fluconazole (FLU), against Candida parapsilosis and C. albicans (Janeczko et al., 2022; Li L. et al., 2022). In Candida species, the combined use of BE and FLU can reduce the MIC values of both antifungal agents, resulting in a better inhibitory effect against fungi (Serpa et al., 2012). Therefore, we hypothesize that combining BE with other antifungal agents could reduce the effective concentration of BE against these fungi, thereby achieving similarly robust antifungal effects as observed against Candida species. This investigation further examines the synergistic antifungal efficacy of BE in conjunction with other azole-class drugs, aiming to enhance azoles treatment efficacy and mitigate the development of resistance.

This study used 54 Aspergillus strains [31 strains of A. fumigatus including 1 strain of wild-type (WT), 1 strain of AF293, 27 strains of clinical A. fumigatus isolates (AF1 ~ AF27) and 2 strains of punctual mutation of the Cyp51A gene (TR34 and TR46), 13 strains of clinical A. flavus isolates (AFL1 ~ AFL13) and 1 strain of NRRL 3357, 4 strains of clinical A. niger isolates (AN1 ~ AN4), 5 strains of clinical A. terreus isolates (AT1 ~ AT5)] and 23 strains dematiaceous fungi [20 strains of E. dermatitidis (BMU00028-00041, 109140, 109145, 109149, D9g, D9h, D9i, D9j, D9k); 3 strains of E. alcalophila (CBS00017, CBS00038, CBSD0001)]. All strains were activated on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) (Haibo Bio) for 2 to 3 days (37°C). All fungal strains were characterized through both microscopic examination of their morphological features and molecular identification via sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) (Glass and Donaldson, 1995). For the precise identification of Aspergillus species, additional molecular analyses involving the sequencing of β-tubulin and calmodulin genes were performed (Hong et al., 2005; Samson and Varga, 2009). The A. flavus ATCC 204304 strain was used as a quality control strain in microdilution assays to ensure the accuracy of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determinations (Gao et al., 2024).

BE (Catalog No. H2308245, Purity 98%), ITC (Catalog No. J2227367, Purity ≥98%), VRC (Catalog No. H2307623, Purity ≥98%), POS (Catalog No. H2224157, Purity ≥99%) and ISV (Catalog No. I337027, Purity ≥98%) five drugs were purchased from Aladdin Reagent Company in Shanghai, dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Macklin) to prepare the stock solution, resulting in a concentration of 3,200 μg/mL for BE and 6,400 μg/mL for azoles.

The antifungal drug solution was prepared according to the M38-A2 method issued by the Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) and previously published protocols (Gao et al., 2024). First, the activated filamentous fungi spores were suspended in PBS (Yisheng Bio), and the concentration was adjusted to 2 ~ 5 × 106 spores/mL. The suspension was subsequently diluted to a concentration of approximately 1 ~ 3 × 104 spores/mL for the filamentous fungi in RPMI 1640 liquid medium. Then, BE and azoles were diluted in RPMI 1640 liquid medium, with the final working concentration range being 0.5 ~ 32.0 μg/mL (for BE), 0.0625 ~ 8 μg/mL (for ITC and VRC) and 0.03125 ~ 4 μg/mL (for POS and ISV). In each direction of the 96-well plate, 50 μL of the diluted drug was added to form different concentration combinations of drugs, followed by the inoculation of the adjusted spore suspension into the 96-well plate, with 100 μL per well. Interpretation of results was performed after incubation at 35°C for 48 h for Aspergillus, and for 72 h for dematiaceous fungi, in accordance with previously published relevant literature (Gao et al., 2024). The MIC was determined by observing the growth of colonies, with the MIC defined as the lowest concentration at which no fungal growth was observed by the naked eye. To assess the combined effect of BE and azoles, the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) was calculated. The formula for FICI is: FICI = (Ac/Aa) + (Bc/Bb), where Ac and Bc are the MICs when used in combination, and Aa and Bb are the MICs when used alone. Based on the FICI value, the type of drug interaction can be determined: FICI≤0.5 indicates a synergistic effect, 0.5 < FICI≤4 indicates no interaction, and FICI>4 indicates an antagonistic effect. All experiments were repeated three times.

The MIC for the individual agents tested were as follows: for BE, all values exceeded 32 μg/mL; for POS, the range was between 0.25 and 1 μg/mL; for ITC, the range spanned from 0.5 to 8 μg/mL; for VRC, the concentrations varied from 0.125 to 4 μg/mL; and for ISV, the MICs were between 0.25 and 4 μg/mL (Table 1). When BE was combined with azoles, the MIC ranges for the drug pairs with synergistic effects were reduced to: BE at 4 μg/mL, POS at 0.03125 μg/mL, and ITC at 0.125 μg/mL; no significant synergistic effects were observed for VRC and ISV. In a cohort of 54 Aspergillus strains, the synergistic effects of the combination of BE with azoles were observed in 47 strains (87.04%) for BE/POS and in 18 strains (33.33%) for BE/ITC, the FICI values were found to span the ranges of 0.25 to 0.5 and 0.3125 to 0.5, respectively. Conversely, no significant synergistic effects were noted for the combinations involving BE with VRC and BE with ISV.

In vitro, when tested against dematiaceous fungi, the MIC of BE was greater than 32 μg/mL. For POS, ITC, VRC and ISV, the MIC ranges were 0.125–1 μg/mL, 0.25–1 μg/mL, 0.0625–0.5 μg/mL, and 0.125–2 μg/mL, respectively (Table 2). When BE was combined with azoles, the MIC ranges for the drug pairs with synergistic effects were reduced to: BE at 4 μg/mL, POS at 0.03125 μg/mL, and ITC at 0.0625 μg/mL; no significant synergistic effects were observed for VRC and ISV. In a cohort of 23 dematiaceous fungi, synergistic effects of the combination of BE with azoles were observed in 22 strains (95.65%) for BE/POS and in 2 strains (8.70%) for BE/ITC, with FICI values ranging from 0.25 to 0.5 and 0.375, respectively. In contrast, antagonistic effects were noted in 6 strains (27.27%) for BE/ITC, 4 strains (18.18%) for BE/VRC, and 4 strains (18.18%) for BE/ISV, while the remainder exhibited no significant interaction.

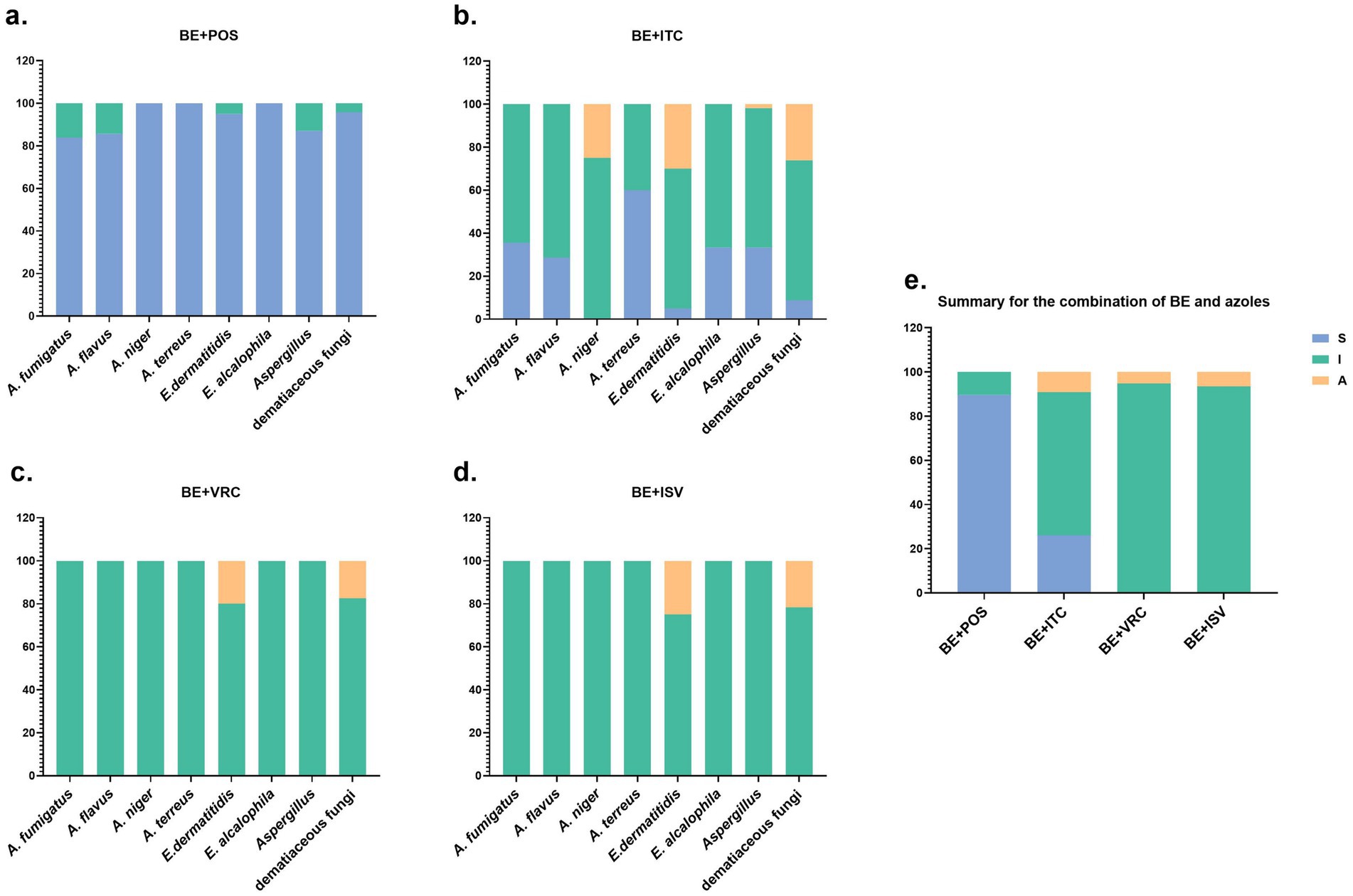

The in vitro interaction study of BE in combination with POS antifungal agents revealed synergistic effects against Aspergillus species, with 26 out of 31 A. fumigatus strains (83.87%), 12 out of 14 A. flavus strains (85.71%), all 4 A. niger strains, and 5 out of 5 A. terreus strains exhibiting such effects (Figure 1a). Among the dematiaceous fungi, 19 out of 20 E. dermatitidis strains (95%) and all 3 E. alcalophila strains demonstrated synergistic activity. 7 Aspergillus strains and one dematiaceous fungi strain exhibited no interaction.

Figure 1. Summary of drug interaction for the combination of BE and azoles. (a–d) The fraction of in vitro interaction results of BE combined with POS, ITC, VRC, and ISV antifungal agents, respectively. (e) Summary of interaction relationships for all drug combinations against all fungi. S, synergy (FICI of ≤ 0.5); I, no interaction (indifference)(0.5 < FICI ≤ 4); A, antagonism (FICI of > 4).

In the in vitro interaction study of BE combined with ITC antifungal agents, synergistic effects were observed in Aspergillus species, with 11 out of 31 A. fumigatus strains (35.48%), 4 out of 14 A. flavus strains (28.57%), and 3 out of 5 A. terreus strains (60%) exhibiting such effects (Figure 1b). Among the dematiaceous fungi, 1 out of 20 E. dermatitidis strains (5%) and 1 out of 3 E. alcalophila strains (33.33%) demonstrated synergistic activity. 35 Aspergillus strains and 15 dematiaceous fungi strains showed no interaction, 1 Aspergillus strain and 6 dematiaceous fungi strains displayed antagonistic effects.

In the combinations of BE with VRC and ISV, all 54 Aspergillus strains exhibited no interaction (Figures 1c,d). Among the dematiaceous fungi, there were 19 strains with no interaction with BE and VRC, and 18 strains with no interaction with BE and ISV. Additionally, 4 strains showed an antagonistic effect with the BE and VRC combination, and 5 strains with the BE and ISV combination.

In the panel of 77 tested fungal strains, 69 (89.61%) demonstrated synergistic interactions in response to the drug combination of BE and POS, while 20 (25.97%) showed synergistic effects with the BE and ITC combination (Figure 1e). No synergistic interactions were observed with BE in combination with VRC or ISV.

Results indicate that among the azoles, combinations of BE with POS and ITC demonstrated synergistic effects against the tested fungal strains. Notably, the BE/POS combination exhibited the most pronounced synergistic effect, observed in 89.61% of strains, with a more frequent observation of synergy in dematiaceous fungi compared to Aspergillus. In contrast, the BE/ITC combination showed significantly less synergy, affecting only 25.97% of strains. The disparity in synergistic effects between the BE/POS and BE/ITC combinations may be attributed to differences in the chemical structures and mechanisms of action of these azoles.

At a concentration of 0.25 mM, BE alleviates A. fumigatus keratitis in mice by inhibiting fungal growth, biofilm formation and adhesion, and by downregulating the expression of pro-inflammatory factors (Zhu et al., 2021). For C. albicans, BE inhibits fungal growth by targeting Eno1, inhibiting glycolysis, and preventing biofilm formation (Li L. et al., 2022). Treatment with BE also induces concentration-dependent accumulation of ROS in Trichophyton mentagrophytes and C. albicans. When BE is used in combination with FLU, it demonstrates robust antifungal activity against drug-resistant fungi. In this context, the biofilm formation of C. albicans is inhibited in a dose-dependent manner at concentrations ranging from 4 to 32 μg/mL (Huang et al., 2008). Baicalein-Core Derivatives can also enhance the antifungal efficacy of FLU by inhibiting hyphal formation in C. albicans (Zhou et al., 2023). The antifungal mechanisms of BE may involve inhibiting biofilm formation and inducing the accumulation of ROS. Further research is needed to elucidate the specific antifungal mechanisms at the molecular level. Azoles inhibit fungal growth by blocking ergosterol synthesis through the inhibition of 14α-sterol demethylase (CYP51) in the fungal cell membrane, leading to impaired cell membrane biogenesis and altered membrane permeability (Patterson et al., 2016). In this study, the combination of BE with POS and ITC exhibited synergistic effects against the tested fungi. In contrast, no synergy was observed when BE was combined with VRC and ISV. Previous studies using molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations to investigate the binding mechanisms and tunneling characteristics of CYP51 with inhibitors have shown that hydrophobic interactions are the primary driving force for binding to CYP51, and that long-chain inhibitors such as POS and ITC can access more CYP51 residues through hydrophobic interactions than short-chain inhibitors like VRC, thereby exhibiting stronger binding affinities (Shi et al., 2020). ISV is a novel azole drug that is structurally similar to VRC (Ghobadi et al., 2022). These differences in binding affinity may account for the lack of synergy observed with ISV and VRC.

Current research on the toxicity of BE is relatively limited. At doses cytotoxic to malignant cells, BE displays minimal or negligible toxicity to normal peripheral blood cells and normal myeloid cells, but it also exerts growth-inhibitory effects on human fetal lung diploid cell lines at the same concentrations that suppress tumor cell proliferation (Li-Weber, 2009). Preliminary animal studies have indicated that BE exhibits low acute toxicity at therapeutic doses, with no significant adverse reactions observed (Wang et al., 2022). In clinical studies involving healthy Chinese subjects, both single-dose and multiple-dose administrations of BE tablets have demonstrated good safety and tolerability, with no serious or severe adverse reactions reported (Li et al., 2021). Studies have shown that the combination of BE at a concentration of 32 μg/mL with ampicillin has negligible effects on hemolysis of red blood cells (RBCs) and cytotoxicity towards Vero cells. This concentration falls within the range tested in our MIC assays (Lu et al., 2021). However, a more comprehensive toxicological evaluation is warranted, especially in the context of the interactions between BE and azoles, to establish the safety profile of these drug combinations through in vitro cytotoxicity assays and in vivo animal models.

The study also noted antagonistic effects in certain cases, particularly with combinations of BE/ITC, BE/VRC, and BE/ISV. These antagonistic effects may arise from competitive inhibition or other unknown molecular interactions that negate the antifungal activity. Additional research is required to understand and potentially mitigate these antagonistic effects.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

ML: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. QH: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. JY: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft. SL: Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JH: Project administration, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Yangtze University Science and Technology Aid to Tibet Medical Talent Training Program Project [grant number 2023YZ06]; the Jingzhou Science and Technology Plan Project [grant number 2024HD34] and the Key Research and Development program of Hubei Province [grant number 2024BCB043].

The authors are grateful to all the participants for their support during the study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Amona, F. M., Oladele, R. O., Resendiz-Sharpe, A., Denning, D. W., Kosmidis, C., Lagrou, K., et al. (2022). Triazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates in Africa: a systematic review. Med. Mycol. 60:myac059. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myac059

Augostine, C. R., and Avery, S. V. (2022). Discovery of natural products with antifungal potential through combinatorial synergy. Front. Microbiol. 13:866840. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.866840

Badiee, P., and Hashemizadeh, Z. (2014). Opportunistic invasive fungal infections: diagnosis & clinical management. Indian J. Med. Res. 139, 195–204

Balajee, S. A. (2009). Aspergillus terreus complex. Med. Mycol. 47, S42–S46. doi: 10.1080/13693780802562092

Borni, M., Kammoun, B., Elleuch Kammoun, E., and Boudawara, M. Z. (2024). A case of invasive Aspergillus niger spondylodiscitis with epidural abscess following covid-19 infection in an immunocompromised host with literature review. Ann. Med. Surg. 86, 6846–6853. doi: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000002610

Da, X., Nishiyama, Y., Tie, D., Hein, K. Z., Yamamoto, O., and Morita, E. (2019). Antifungal activity and mechanism of action of ou-gon (scutellaria root extract) components against pathogenic fungi. Sci. Rep. 9:1683. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-38916-w

Djenontin, E., Costa, J., Mousavi, B., Nguyen, L. D. N., Guillot, J., Delhaes, L., et al. (2023). The molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility of clinical isolates of Aspergillus section Flavi from three French hospitals. Microorganisms. 11:2429. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11102429

Fang, W., Wu, J., Cheng, M., Zhu, X., Du, M., Chen, C., et al. (2023). Diagnosis of invasive fungal infections: challenges and recent developments. J. Biomed. Sci. 30:42. doi: 10.1186/s12929-023-00926-2

Gao, L., Xia, X., Gong, X., Zhang, H., and Sun, Y. (2024). In vitro interactions of proton pump inhibitors and azoles against pathogenic fungi. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 14:1296151. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1296151

Ghobadi, E., Saednia, S., and Emami, S. (2022). Synthetic approaches and structural diversity of triazolylbutanols derived from voriconazole in the antifungal drug development. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 231:114161. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114161

Glass, N. L., and Donaldson, G. C. (1995). Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 1323–1330. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1323-1330.1995

Gupta, S., Buttar, H. S., Kaur, G., and Tuli, H. S. (2022). Baicalein: promising therapeutic applications with special reference to published patents. Pharm. Pat. Anal. 11, 23–32. doi: 10.4155/ppa-2021-0027

Hedayati, M. T., Pasqualotto, A. C., Warn, P. A., Bowyer, P., and Denning, D. W. (2007). Aspergillus flavus: human pathogen, allergen and mycotoxin producer. Microbiology (Reading). 153, 1677–1692. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/007641-0

Hong, S. B., Go, S. J., Shin, H. D., Frisvad, J. C., and Samson, R. A. (2005). Polyphasic taxonomy of Aspergillus fumigatus and related species. Mycologia 97, 1316–1329. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832738

Huang, S., Cao, Y. Y., Dai, B. D., Sun, X. R., Zhu, Z. Y., Cao, Y. B., et al. (2008). In vitro synergism of fluconazole and baicalein against clinical isolates of Candida albicans resistant to fluconazole. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 31, 2234–2236. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.2234

Janeczko, M., Gmur, D., Kochanowicz, E., Gorka, K., and Skrzypek, T. (2022). Inhibitory effect of a combination of baicalein and quercetin flavonoids against Candida albicans strains isolated from the female reproductive system. Fungal Biol. 126, 407–420. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2022.05.002

Jin, Y. S. (2019). Recent advances in natural antifungal flavonoids and their derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 29:126589. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.07.048

Kaushik, A., and Kest, H. (2018). The role of antifungals in pediatric critical care invasive fungal infections. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2018:8469585. doi: 10.1155/2018/8469585

Kirchhoff, L., Olsowski, M., Rath, P., and Steinmann, J. (2019). Exophiala dermatitidis: key issues of an opportunistic fungal pathogen. Virulence 10, 984–998. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2019.1596504

Kondori, N., Jaen-Luchoro, D., Karlsson, R., Abedzaedeh, B., Hammarstrom, H., and Jonsson, B. (2024). Exophiala species in household environments and their antifungal resistance profile. Sci. Rep. 14:17622. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-68166-4

Lai, J., Zhao, L., Hong, C., Zou, Q., Su, J., Li, S., et al. (2024). Baicalein triggers ferroptosis in colorectal cancer cells via blocking the jak2/stat3/gpx4 axis. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 45, 1715–1726. doi: 10.1038/s41401-024-01258-z

Li, L., Gao, H., Lou, K., Luo, H., Hao, S., Yuan, J., et al. (2021). Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of oral baicalein tablets in healthy Chinese subjects: a single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multiple-ascending-dose study. Cts-Clin. Transl. Sci. 14, 2017–2024. doi: 10.1111/cts.13063

Li, L., Lu, H., Zhang, X., Whiteway, M., Wu, H., Tan, S., et al. (2022). Baicalein acts against Candida albicans by targeting eno1 and inhibiting glycolysis. Microbiol. Spectr. 10:e208522. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02085-22

Li, Y. Y., Wang, X. J., Su, Y. L., Wang, Q., Huang, S. W., Pan, Z. F., et al. (2022). Baicalein ameliorates ulcerative colitis by improving intestinal epithelial barrier via ahr/il-22 pathway in ilc3s. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 43, 1495–1507. doi: 10.1038/s41401-021-00781-7

Li, C., Wang, J., Wu, H., Zang, L., Qiu, W., Wei, W., et al. (2024). Baicalein induces apoptosis by targeting ribosomes in Candida auris. Arch. Microbiol. 206:404. doi: 10.1007/s00203-024-04136-8

Li-Weber, M. (2009). New therapeutic aspects of flavones: the anticancer properties of Scutellaria and its main active constituents wogonin, baicalein and baicalin. Cancer Treat. Rev. 35, 57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.09.005

Lu, H., Li, X., Wang, G., Wang, C., Feng, J., Lu, W., et al. (2021). Baicalein ameliorates Streptococcus suis-induced infection in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22:5829. doi: 10.3390/ijms22115829

Lv, Q. Z., Zhang, X. L., Gao, L., Yan, L., and Jiang, Y. Y. (2022). Itraq-based proteomics revealed baicalein enhanced oxidative stress of Candida albicans by upregulating cpd2 expression. Med. Mycol. 60:myac053. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myac053

Morelli, K. A., Kerkaert, J. D., and Cramer, R. A. (2021). Aspergillus fumigatus biofilms: toward understanding how growth as a multicellular network increases antifungal resistance and disease progression. PLoS Pathog. 17:e1009794. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009794

Patterson, T. F., Thompson, G. R., Denning, D. W., Fishman, J. A., Hadley, S., Herbrecht, R., et al. (2016). Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 63, e1–e60. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw326

Peyton, L. R., Gallagher, S., and Hashemzadeh, M. (2015). Triazole antifungals: a review. Drugs Today. 51, 705–718. doi: 10.1358/dot.2015.51.12.2421058

Pfaller, M. A., Carvalhaes, C. G., Rhomberg, P., Messer, S. A., and Castanheira, M. (2021). Antifungal susceptibilities of opportunistic filamentous fungal pathogens from the Asia and western pacific region: data from the sentry antifungal surveillance program (2011-2019). J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 74, 519–527. doi: 10.1038/s41429-021-00431-4

Puerta-Alcalde, P., and Garcia-Vidal, C. (2021). Changing epidemiology of invasive fungal disease in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J. Fungi. 7:848. doi: 10.3390/jof7100848

Revankar, S. G. (2007). Dematiaceous fungi. Mycoses 50, 91–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2006.01331.x

Samson, R. A., and Varga, J. (2009). What is a species in Aspergillus? Med. Mycol. 47, S13–S20. doi: 10.1080/13693780802354011

Serpa, R., Franca, E., Furlaneto-Maia, L., Andrade, C., Diniz, A., and Furlaneto, M. C. (2012). In vitro antifungal activity of the flavonoid baicalein against candida species. J. Med. Microbiol. 61, 1704–1708. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.047852-0

Shi, N., Zheng, Q., and Zhang, H. (2020). Molecular dynamics investigations of binding mechanism for triazoles inhibitors to cyp51. Front. Mol. Biosci. 7:586540. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.586540

Song, Q., Peng, S., and Zhu, X. (2021). Baicalein protects against mpp(+)/mptp-induced neurotoxicity by ameliorating oxidative stress in sh-sy5y cells and mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Neurotoxicology 87, 188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2021.10.003

Tuli, H. S., Aggarwal, V., Kaur, J., Aggarwal, D., Parashar, G., Parashar, N. C., et al. (2020). Baicalein: a metabolite with promising antineoplastic activity. Life Sci. 259:118183. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118183

Wang, Y., Cui, X., Tian, R., and Wang, P. (2024). The epidemiological characteristics of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and risk factors for treatment failure: a retrospective study. BMC Pulm. Med. 24:559. doi: 10.1186/s12890-024-03381-3

Wang, L., Feng, T., Su, Z., Pi, C., Wei, Y., and Zhao, L. (2022). Latest research progress on anticancer effect of baicalin and its aglycone baicalein. Arch. Pharm. Res. 45, 535–557. doi: 10.1007/s12272-022-01397-z

Yan, W., Ma, X., Zhao, X., and Zhang, S. (2018). Baicalein induces apoptosis and autophagy of breast cancer cells via inhibiting pi3k/akt pathway in vivo and vitro. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 12, 3961–3972. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S181939

Yang, H., Gu, Y., He, Z., Wu, J. N., Wu, C., Xie, Y., et al. (2023). In vitro and in vivo antimicrobial effects of domiphen combined with itraconazole against Aspergillus fumigatus. Front. Microbiol. 14:1264586. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1264586

Zhao, Z., Nian, M., Qiao, H., Yang, X., Wu, S., and Zheng, X. (2022). Review of bioactivity and structure-activity relationship on baicalein (5,6,7-trihydroxyflavone) and wogonin (5,7-dihydroxy-8-methoxyflavone) derivatives: structural modifications inspired from flavonoids in Scutellaria baicalensis. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 243:114733. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114733

Zhou, H., Yang, N., Li, W., Peng, X., Dong, J., Jiang, Y., et al. (2023). Exploration of baicalein-core derivatives as potent antifungal agents: Sar and mechanism insights. Molecules 28:6340. doi: 10.3390/molecules28176340

Keywords: baicalein, posaconazole, itraconazole, synergy, Aspergillus, dematiaceous fungi

Citation: Liang M, Hu Q, Yu J, Zhang H, Liu S, Huang J and Sun Y (2025) Baicalein combined with azoles against fungi in vitro. Front. Microbiol. 16:1537229. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1537229

Received: 30 November 2024; Accepted: 27 February 2025;

Published: 13 March 2025.

Edited by:

Amanda Claire Brown, Tarleton State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Mónika Homa, University of Szeged, HungaryCopyright © 2025 Liang, Hu, Yu, Zhang, Liu, Huang and Sun. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jiangrong Huang, aGppYW5ncm9uZ0AxMjYuY29t; Yi Sun, anp6eHl5c3lAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.