- College of Animal Science and Technology, Hebei Agricultural University, Baoding, China

Introduction: This study aimed to investigate the digestive function, urea utilization ability, and bacterial composition changes in rumen microbiota under high urea (5% urea in diet) over 23 days of continuous batch culture in vitro.

Methods: The gas production, dry matter digestibility, and bacterial counts were determined for the continuously batch-cultured rumen fluid (CRF). The changes in fermentation parameters, NH3-N utilization efficiency, and microbial taxa were analyzed in CRF and were compared with that of fresh rumen fluid (RF), frozen rumen fluid (FRF, frozen rumen fluid at −80°C for 1 month), and the mixed rumen fluid (MRF, 3/4 RF mixed with 1/4 CRF) with in vitro rumen fermentation.

Results: The results showed that the dry matter digestibility remained stable while both the microbial counts and diversity significantly decreased over the 23 days of continuous batch culture. However, the NH3-N utilization efficiency of the CRF group was significantly higher than that of RF, FRF, and MRF groups (p < 0.05), while five core genera including Succinivibrio, Prevotella, Streptococcus, F082, and Megasphaera were retained after 23 days of continuous batch culture. The NH3-N utilization efficiency was effectively improved after continuous batch culture in vitro, and Streptococcus, Succinivibrio, Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1, p.251.o5, Oxalobacter, Bacteroidales_UCG.001, and p.1088.a5_gut_group were identified to explain 75.72% of the variation in NH3-N utilization efficiency with the RandomForest model.

Conclusion: Thus, core bacterial composition and function retained under high urea (5% urea in diet) over 23 days of continuous batch culture in vitro, and bacterial biomarkers for ammonia utilization were illustrated in this study. These findings might provide potential applications in improving the efficiency and safety of non-protein nitrogen utilization in ruminants.

1 Introduction

Livestock husbandry plays a pivotal role in human food supply and continues to grow in the population. However, the protein feed shortage brings a heavy burden to livestock raising worldwide (Kim et al., 2019). Developing new protein feedstuffs might be one of the important measures to solve this issue. Non-protein nitrogen could be used by ruminants via rumen microbes, and urea is a kind of widely available and cost-effective protein feed component for ruminants. Upon entering the rumen, with the urease secreted by ureolytic bacteria, urea is rapidly hydrolyzed to ammonia, and the ammonia is further utilized by ammonia-utilizing bacteria and converted to microbial crude protein (MCP), which is a kind of high-quality protein (Fuller and Reeds, 1998; Jin et al., 2018; Patra and Aschenbach, 2018). Previous studies demonstrated that the MCP could provide approximately 80% of the protein requirements for ruminant animals, especially when ruminants were fed with a low-protein diet (Abdoun et al., 2006), and increasing the urea supplementation level from 0 to 2% in the diet also could increase MCP content by 64% in the rumen (Zhang et al., 2016).

However, the feeding level of urea was limited because the hydrolysis of urea was always higher than the microbial utilization of ammonia and thus caused ammonia toxicity, a decrease in dry matter intake (Wang et al., 2016), and digestibility (Kertz, 2010). In ruminants raising, a general adaptation period of 14 to 21 days is required when using the urea in diet because ruminants showed a gradual adaptation to the non-protein nitrogen (Adejoro et al., 2020), and the mechanism was inferred as enhancing the ammonia utilization capacity of ammoniacal nitrogen-utilizing bacteria (Patra and Aschenbach, 2018). Improving the adaptation of rumen microbiota to urea-containing feed might be an efficient strategy to enhance the feeding level of urea.

Rumen microbiota transplantation could change the composition and function of rumen microbiota rapidly (Liu et al., 2019), which might have promising applications in improving the urea adaptation and utilization efficiency, but how to obtain rumen microbiota with efficient urea utilization was the major challenge. Previous studies have shown that rumen simulation systems in vitro can maintain rumen microbiota composition and function by continuously adding rumen buffer and fermentation substrates (Muetzel et al., 2009), thus producing rumen microbiota by propagation. However, there is still a lack of information about the composition and function changes during the urea adaptation period in a rumen simulation system in vitro. Therefore, we wondered how the core bacterial composition and function, as well as the urea-utilizing efficiency, changed in rumen simulation systems in vitro after a long period of urea adaptation higher than 21 days.

Herein, in this study, the rumen microbiota was batch-cultured continuously for 23 days in vitro, and we compared the fermentation parameters, urea-utilizing efficiency, and bacterial composition of the continuously batch-cultured rumen fluid with the fresh rumen fluid. As frozen microbiota was usually used in microbiota transplantation (Lee et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2021), and only a portion of rumen fluid was replaced in rumen microbiota transplantation (DePeters and George, 2014; Yin et al., 2021), the bacterial composition and function of frozen rumen fluid (stored at −80°C for 1 month) and mixed rumen fluid (1 of 4 continuously batch-cultured rumen fluid and 3 of 4 fresh rumen fluid) were also assessed. This finding might help improve the security and efficiency of using urea in the diet of ruminants.

2 Materials and methods

This research was carried out at the Animal Experimental Center of Hebei Agriculture University from January 2022 to June 2023. The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Hebei Agricultural University (ID: 2021091).

2.1 Animals and feed management

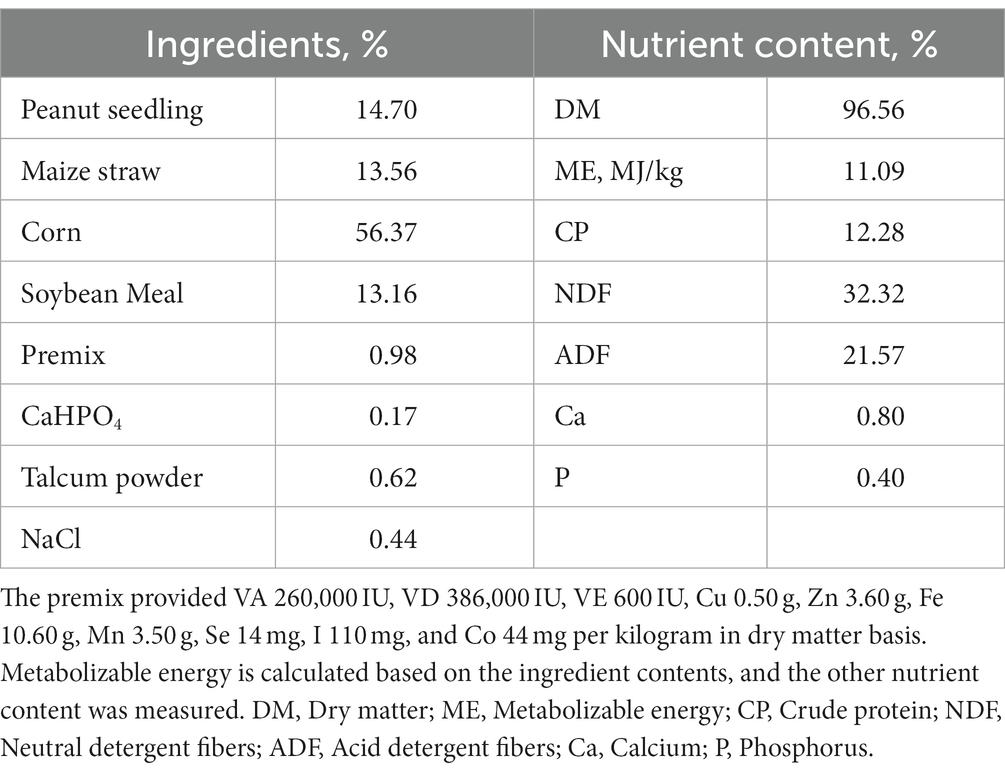

The rumen fluid used in this experiment was collected from 6 Hu sheep of approximately 2 years old with permanent rumen fistulas, and the sheep were housed at the Animal Experimental Center of Hebei Agricultural University. The diet was formulated according to NRC2007 (50 kg body weight, 200 g daily gain, the metabolizable energy, and crude protein content in the diet was 11.09 MJ/kg and 12.28% as dry matter basis, respectively). The feed was collected and dried at 65°C for 48 h to achieve air-dried samples, sieved through a 10-mesh sieve, and stored in a dry and sealed environment for nutrient analysis (Table 1).

2.2 Rumen fluid preparation

2.2.1 Fresh rumen fluid

Fresh rumen digesta was collected through the rumen fistula before morning feeding and was filtered through four layers of sterile gauze. Then, the rumen fluid was collected and put into a thermos flask filled with CO2, and it was brought back to the laboratory within 15 min for subsequent experiments.

2.2.2 Frozen rumen fluid

The fresh rumen fluid was collected following the previous statement and stored at −80°C for 1 month before the subsequent experiment.

2.2.3 Continuously batch-cultured rumen fluid

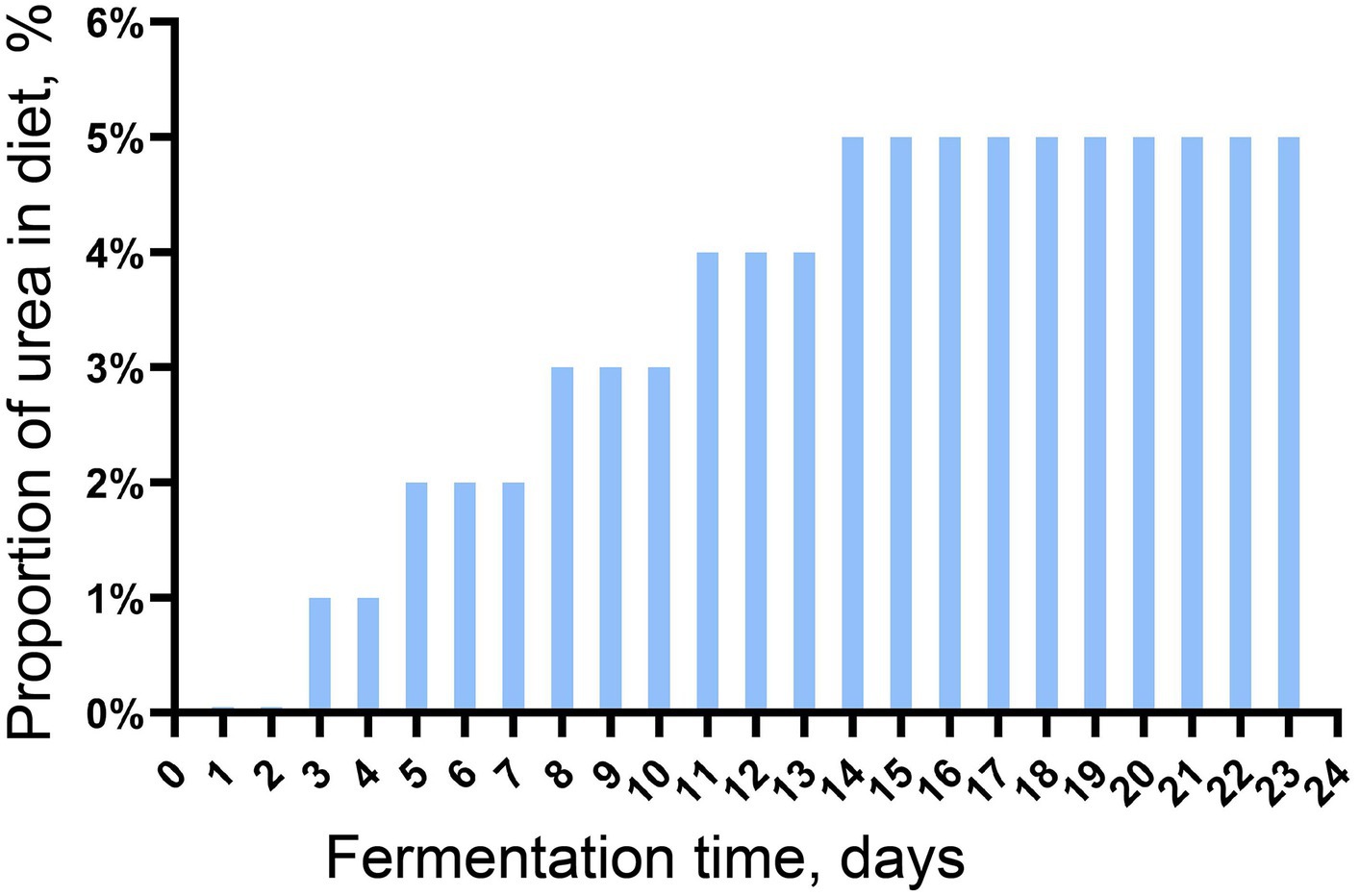

The microbiota in the fresh rumen fluid was continuously batch-cultured in an in vitro batch culture system for 23 days before the subsequent experiment. The rumen buffer (pH = 6.86) was prepared following the method by Menke et al. (1979), and the batch culture was conducted and modified from our previous study (Li et al., 2022). In brief, the rumen buffer was preheated in the water bath at 39°C for 30 min with CO2 to remove oxygen. In total, 30 g of feed containing urea (increased amount gradually, Figure 1) was put into a 5.5 × 4.5 cm nylon bag (300 mesh), and the nylon bag was placed into a 2 L fermentation bag. Then, 200 mL of the preheated rumen buffer and 100 mL of fresh rumen fluid (also preheated at 39°C for 30 min) were mixed and added to the fermentation bag. Four replicates were set up in this trial, and the urea used in this experiment was with purity higher than 99.0%. One round of batch culture lasted for 24 h, and gas production was measured using a graduated syringe. At the end of each round of batch culture, solid and fluid fractions were separated by filtering the digesta through four layers of sterile gauze, and the solid fraction was collected for dry matter digestibility determination; the fluid fraction was collected and mixed with the preheated rumen buffer at the ratio of 1:2 for another round of batch culture. The continuous batch culture in vitro was carried out in 23 rounds.

2.2.4 Mixed rumen fluid

Overall, 3 of 4 fresh rumen fluid was mixed with 1 of 4 continuously batch-cultured rumen fluid before the subsequent experiment.

2.3 Rumen fermentation with different types of rumen fluid in vitro

Four treatment groups were set up, namely, RF group (fresh rumen fluid), FRF group (frozen rumen fluid at −80°C for 1 month, ice water bath for 8 h, and preheated at 39°C for 30 min before used), CRF group (continuously batch-cultured rumen fluid for 23 days), and MRF group (3 of 4 fresh rumen fluid mixed with 1 of 4 continuously batch-cultured rumen fluid).

Before rumen fermentation in vitro, the bacterial content in each group was counted. In brief, after being stained with ammonium oxalate-crystal violet and saline multiplicity dilution, the bacteria were counted using a hemocytometer under 1,000x magnification. The bacterial content was calculated as follows: Bacterial Count/ml = N/S*D*16*10*100, where N was the number of counting grid squares, S was the total number of squares counted, and D was the dilution factor. As the bacteria content in different groups was also different, the bacterial content in each group was regulated to 7.45 × 109/ml, with rumen buffer solution for rumen fermentation in vitro.

Six replicates were set up for each group, and the rumen fermentation with anaerobic condition was performed following the previous protocol (Li et al., 2022) with some modifications: 3 g of diet containing 5% urea (dry matter basis) was used as fermentation substrate, and the fermentation lasted for 48 h. Gas production was measured using a graduated syringe; 2 mL of fluid was collected at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24, and 48 h, respectively. At the end of the fermentation, the bags were placed in an ice water bath immediately to terminate fermentation; The nylon bag containing feed residues was rinsed three times with distilled water and then dried at 65°C for 48 h; the liquid fraction was also collected and stored at −80°C for determination of pH, MCP, and bacterial composition.

2.4 Chemical analysis

The pH of the fluid fraction was determined using an EL20-type acidimeter. The MCP protein was determined following the method described by Makkar et al. (1982), and the concentration of NH3-N was measured with the phenol-hypochlorite colorimetric method (Lv et al., 2019). Gas production parameters were calculated using the LELAG mathematical model: GP = b(1–2.718(−c(t-LAG))), where b represented theoretical gas production (ml), c represented gas production rate, and t represented time point (Wang et al., 2011). The diet substrate and undegraded residuals were dried at 65°C for 48 h, and the dry matter (DM) was determined following the AOAC method (AOAC, 2016). The digestibility of dry matter was calculated according to the formula as follows: [(Initial Dry Matter Content–Final Dry Matter Content)/Initial Dry Matter Content] × 100%.

2.5 High-throughput sequencing

Total microbial DNA was extracted from the rumen fluid samples after 48 h of rumen fermentation in vitro using the E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Inc., United States), and the quality and concentration of the DNA were assessed using the Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., United States). The V3-V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified with the primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) using an ABI 9700 PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems, Inc., USA). The PCR amplification system consisted of 1 μL of forward primer (5 μM) and reverse primer (5 μM), 3 μL of DNA template (30 mg total template), 3 μL of BSA (2 ng/μl) and ddH2O, and 12.52 μL of Taq Plus Master Mix. The PCR amplification program was as follows: pre-denaturation for 5 min (95°C), denaturation for 45 s (95°C), annealing for 50 s (55°C), extension for 45 s (72°C) for 28 cycles, and extension for 10 min (72°C). The PCR products were purified using the Nucleic Acid Purification Kit (Agencourt AMPure XP, Beckman Coulter, Inc., United States), and finally, high-throughput sequencing was performed on the Illumina Miseq platform (Illumina, Inc., United States), following our previous study (Li et al., 2022).

2.6 Bioinformatic analysis

After filtering out the low-quality reads with a quality score lower than 20 over a 50 bp sliding window and sequences with reads shorter than 50 bp with Trimmomatic (v0.36; Gong et al., 2019), the sequencing raw data were assembled using Pear (v0.9.6) software. Vsearch (version 2.0.3) was then used to remove short sequences and chimeras in assembled sequences. Representative sequences were aligned at the Silva138 database with a 97% sequence similarity threshold, to generate operational taxonomic units (OTUs). The α-diversity and β-diversity indexes were analyzed using QIIME (v1.8.0) software.

2.7 Statistical analysis

The rumen fermentation parameters after 48 h of rumen fermentation in vitro, including DM digestibility, 48 h cumulative GP, theoretical GP, pH, and MCP, were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, and comparison was performed with Duncan’s method using SPSS 26.0 software; the area under the curve (AUC) of dynamic changes in NH3-N content in rumen fluid was calculated, changes in rumen microbial community structure were analyzed based on principal component analysis and ANOSIM statistics, and RandomForest analysis was performed with the RandomForest package using R software (v4.1.2) with ntree = 10,000, mtry = p/3, where p is the number of bacterial taxa, and signature bacteria were screened by increasing mean squared error (%IncMSE) and cross-validation. Data were expressed as means and standard error of means (SEM), and p < 0.05 was considered significantly different.

3 Results

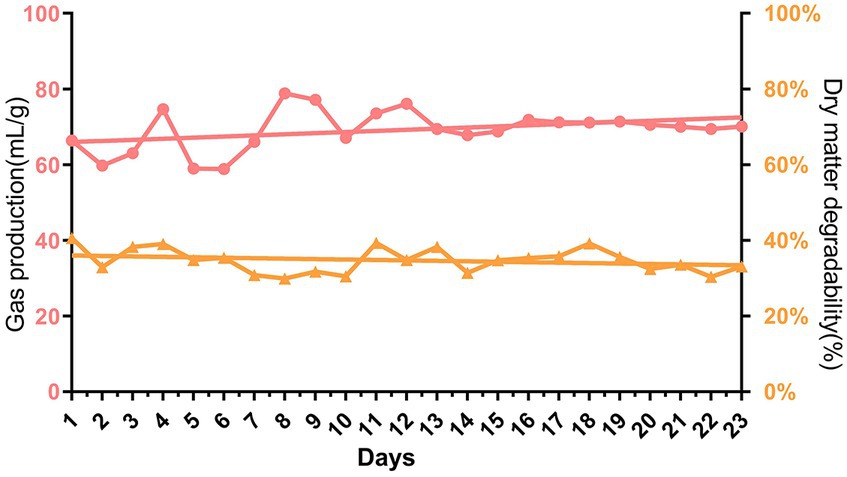

3.1 Dynamic changes in gas production and dry matter digestibility during continuous batch culture in vitro

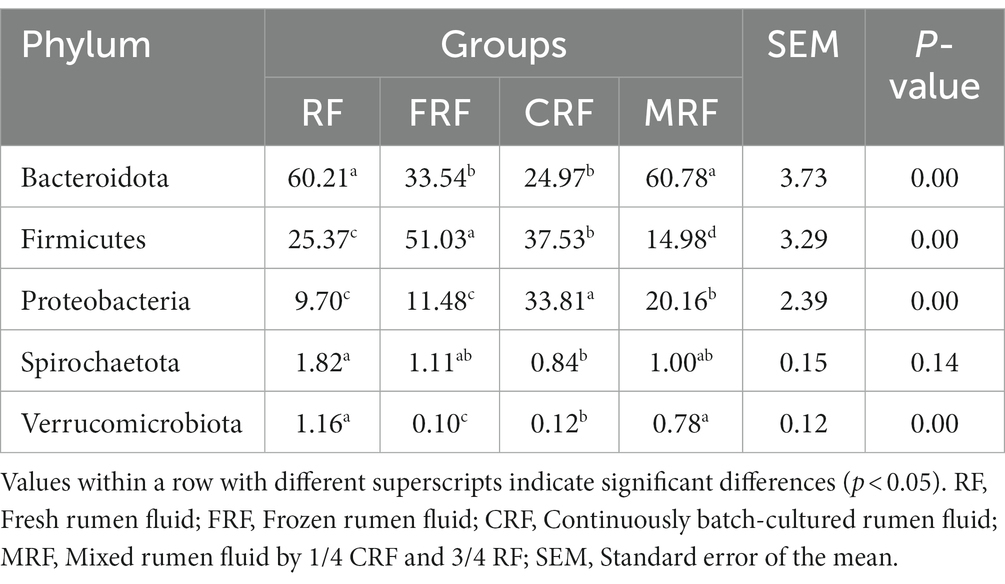

During the first 13 days of gradually increasing urea addition from 0 to 5%, the gas production showed obvious fluctuations from 58.87 mL/g to 77.18 mL/g. While the urea addition was stabilized at 5% after 13 days of fermentation, the gas production became relatively stable at approximately 70.26 mL/g. The dry matter digestibility remained stable with an average of approximately 34.74% over 23 days of continuous rumen batch culture in vitro (p > 0.05, Figure 2).

Figure 2. Dynamic changes of gas production and dry matter digestibility during continuous batch culture in vitro.

3.2 Bacterial count of continuous fermentation fluid

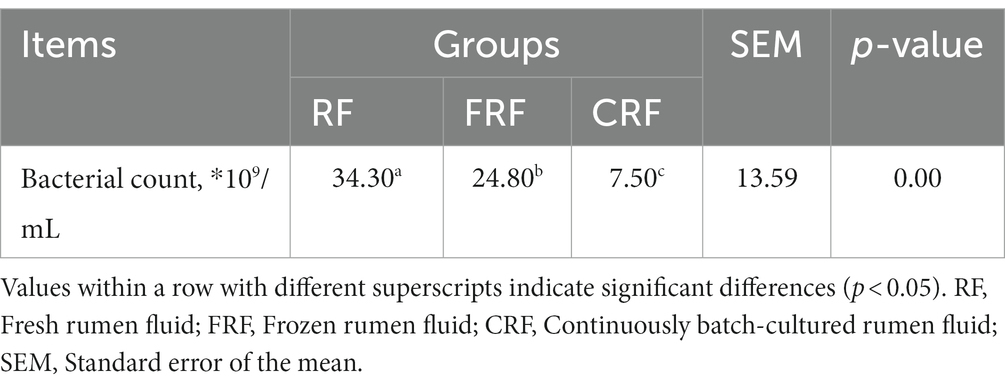

After 23 days of continuous batch culture, the bacterial counts in the CRF group were approximately 3.4 × 1010, significantly lower than that in fresh rumen fluid (7.54 × 109) but still higher than that in frozen rumen fluid (2.48 × 1010; p < 0.05; Table 2).

3.3 The effects of continuously batch-cultured rumen fluid on fermentation parameters in vitro

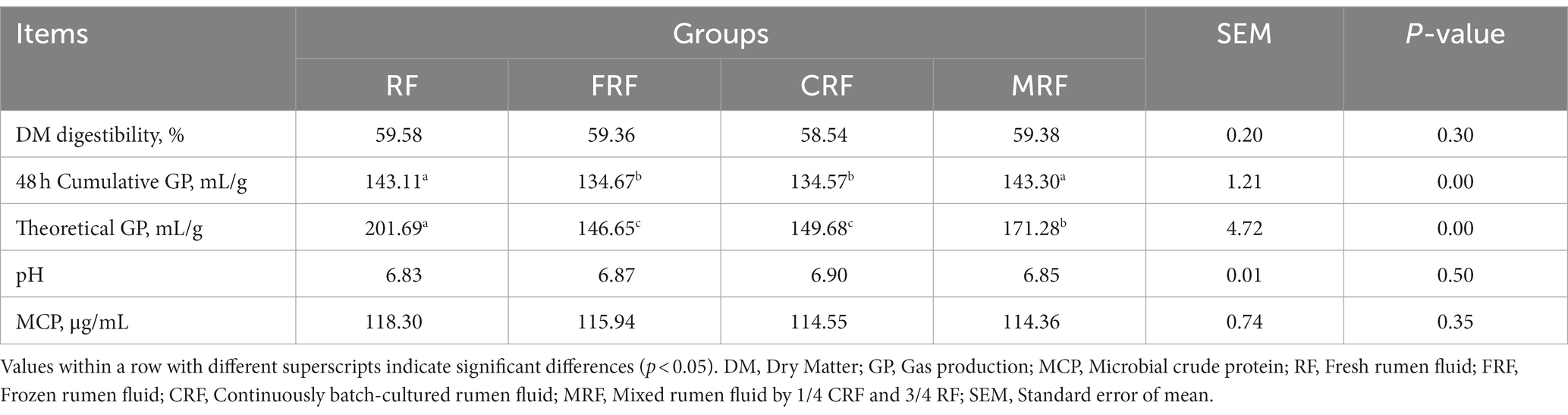

To confirm the function of the microbial community after continuous rumen batch culture in vitro, the fermentation parameters of four groups were compared. The results showed that both the 48 h cumulative and theoretical gas production of the CFR group were significantly lower than those of the RF and MRF groups (p < 0.05), but no significant difference was detected in the DM digestibility, pH, and MCP concentration between the groups (p > 0.05; Table 3).

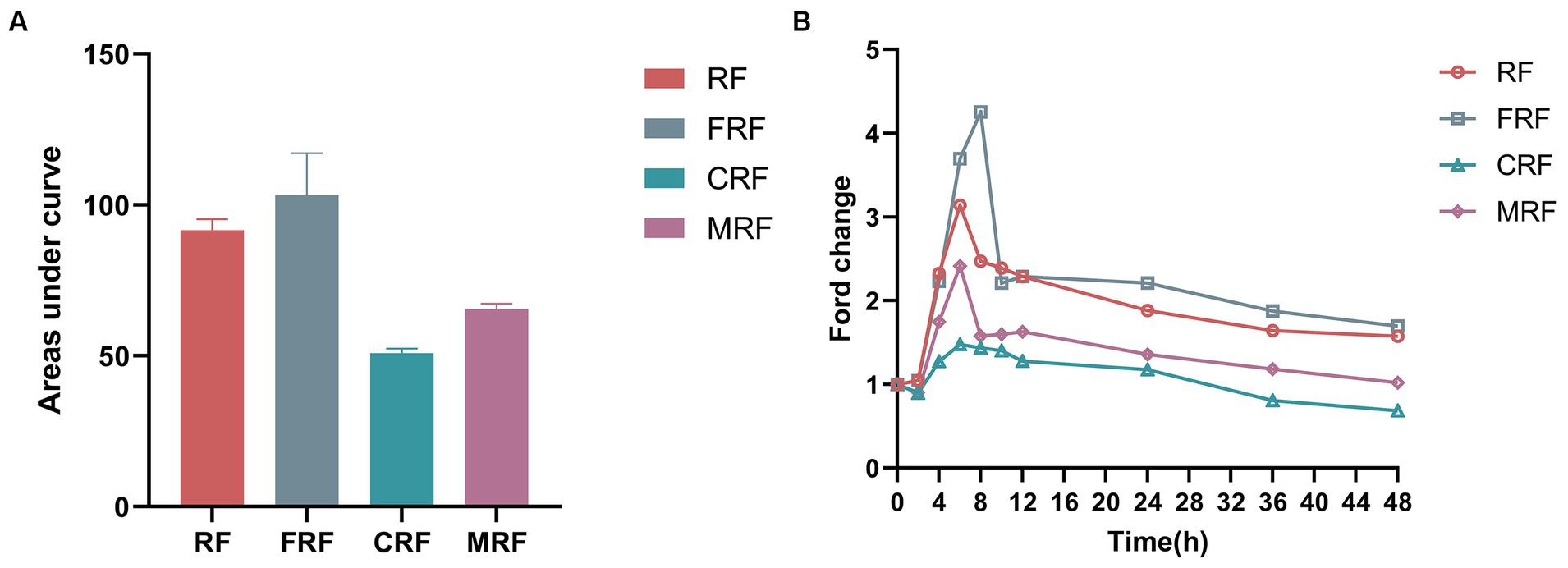

3.4 The NH3-N utilization efficiency of rumen microbiota after continuous rumen batch culture in vitro

As the microbiota of rumen fluid was domesticated after continuous batch culture in vitro, we wondered whether the NH3-N utilization efficiency would increase. Here, we observed the fold change in NH3-N concentrations against its initial concentration at 0 h of fermentation, which significantly differed between the groups after 48 h of in vitro fermentation. The highest NH3-N concentration in the FRF, RF, and MRF groups was after 6–8 h of batch culture, with NH3-N concentrations rising 4.2, 3.1, and 2.4 times, respectively, while that in the CRF group was at 4 h, with NH3-N rising approximately 1.5 times (Figure 3A). The area under the curves of dynamic NH3-N content in the CRF group was also significantly lower than that in the RF, FRF, and MRF groups (Figure 3B; p < 0.05).

Figure 3. The NH3-N utilization efficiency of microbiota after continuous rumen batch culture in vitro. (A) dynamic change of NH3-N content with rumen batch culture in vitro; (B) the area under the curve of the dynamic change of NH3-N content with rumen batch culture in vitro. RF, Fresh rumen fluid; FRF, Frozen rumen fluid; CRF, Continuously batch-cultured rumen fluid; MRF, Mixed rumen fluid by 1/4 CRF and 3/4 RF.

3.5 Bacterial composition in rumen fluid after batch culture in vitro

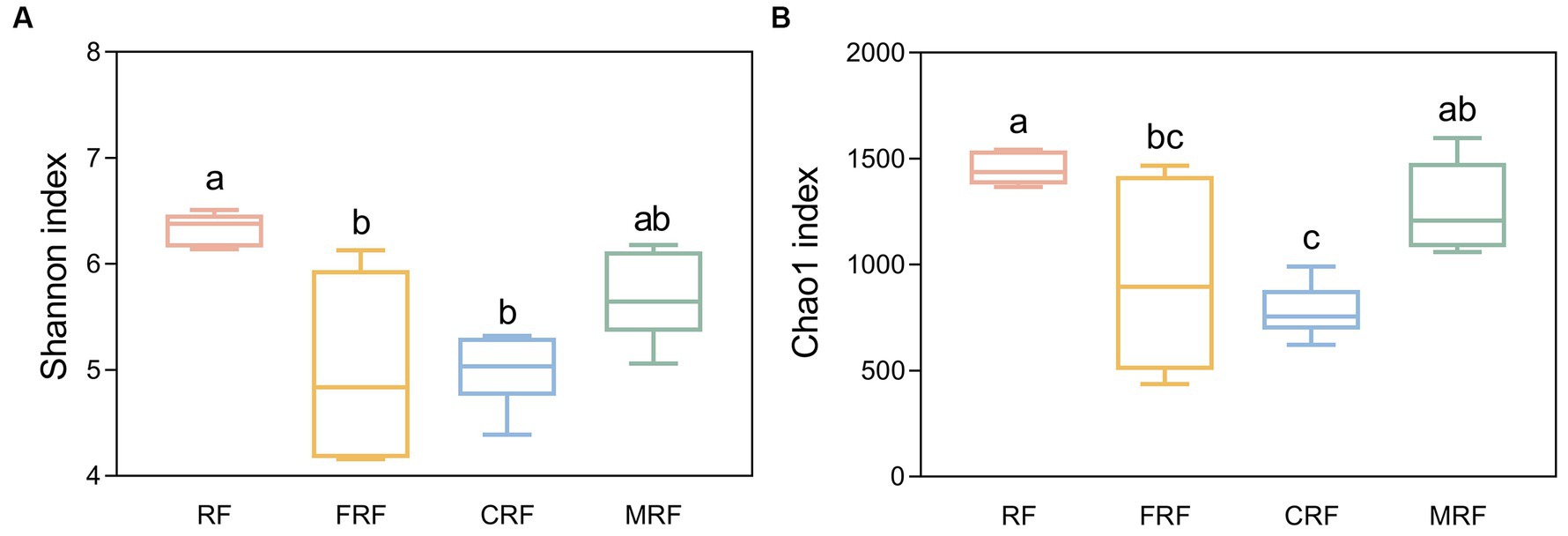

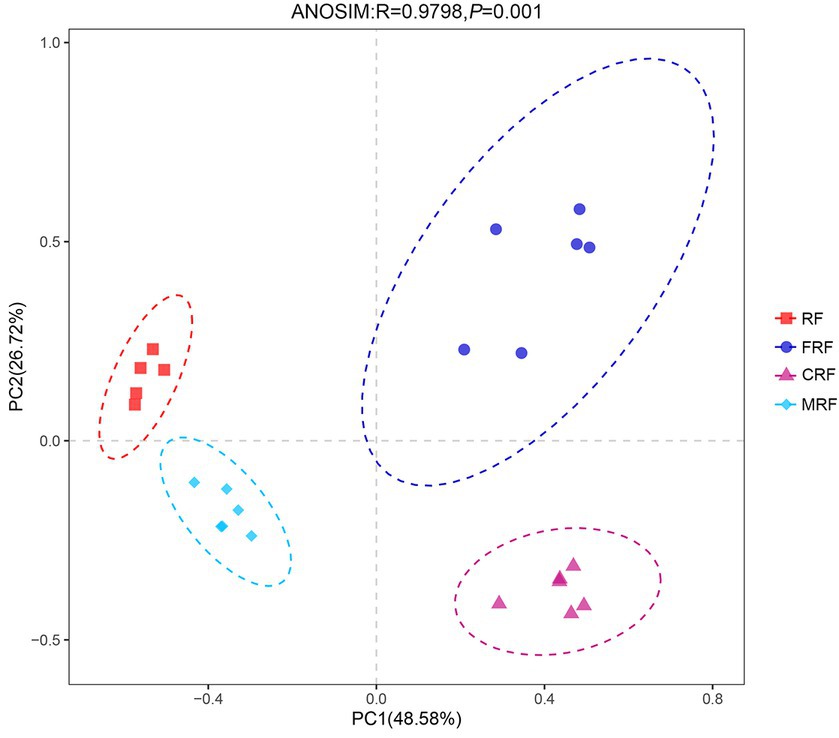

With high-throughput sequencing of 16S rRNA genes, 29 phyla, 62 classes, 130 orders, 205 families, and 337 genera were identified. Both Chao1 and Shannon indexes of the CRF group and FRF group showed significantly lower compared with that of the RF group (p < 0.05; Figure 4). A significant difference in the microbial community structure among the RF, FRF, CRF, and MRF groups with PCoA analysis was also observed (R = 0.9798; ANOSIM, p = 0.001; Figure 5). The PC1 axis explained 48.48% of the variance, while the PC2 axis explained 26.72% of the variance of microbial community structure (Figure 5). This finding suggested that continuous batch culture or frozen treatment could lead to a reduction in microbial diversity.

Figure 4. Comparing the alpha diversity index between groups. (A) shannon index between groups; (B) Chao1 index between groups. RF, Fresh rumen fluid; FRF, Frozen rumen fluid; CRF, Continuously batch-cultured rumen fluid; MRF, Mixed rumen fluid by 1/4 CRF and 3/4 RF.

Figure 5. PCoA analysis based on Bray–Curtis distance at OTU level. RF, Fresh rumen fluid; FRF, Frozen rumen fluid; CRF, Continuously batch-cultured rumen fluid; MRF: Mixed rumen fluid by 1/4 CRF and 3/4 RF.

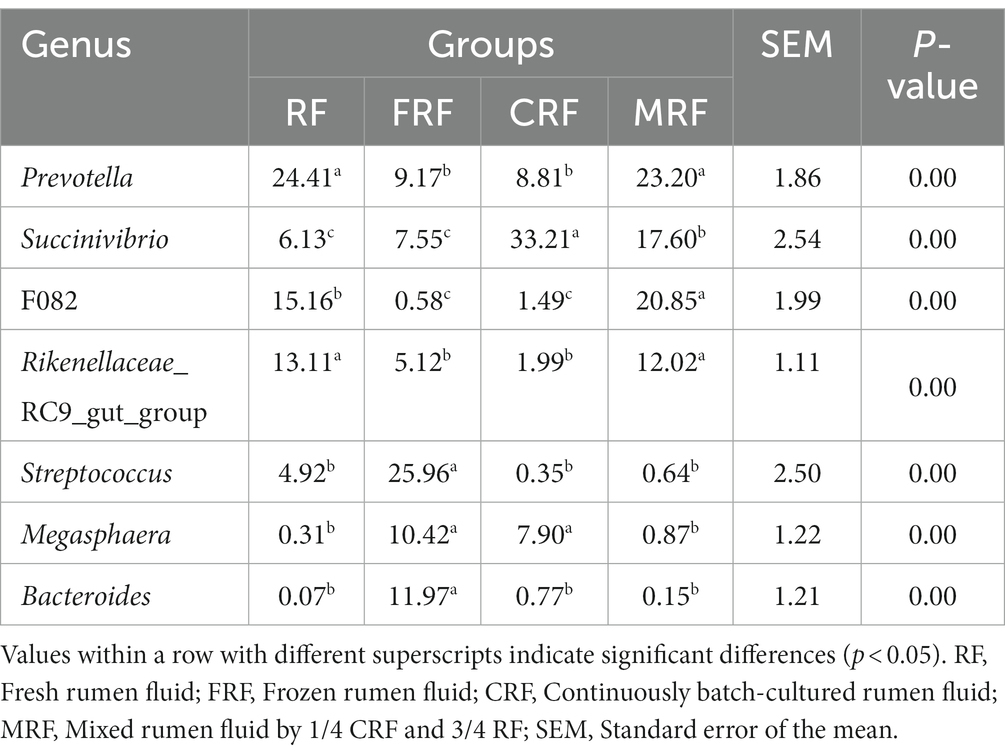

At the phylum level, Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria were the top three dominant phyla (relative abundances higher than 5%); however, the relative abundances of the dominant phyla differed between groups (p < 0.05). Bacteroidota were the most dominant phylum in the RF group and MRF group, accounting for 60.21 and 60.78%, respectively, which were significantly higher than that of the FRF and CRF groups (33.54 and 24.97%, P<0.05). Firmicutes were the second most abundant phylum, on average, and it was the most dominant phylum in the FRF group and CRF group, accounting for 51.03 and 37.53%, respectively, which were significantly higher than that in the RF group and MRF group (25.37 and 14.98%, P<0.05). Proteobacteria had the highest abundance in the CRF group, accounting for 33.81%, which was significantly higher than that in the other three groups (p < 0.05), with 9.7, 11.48, and 20.6%, respectively. In addition, compared with the RF group, Spirochaetota and Verrucomicrobiota showed a significant decrease in the abundance in the CRF group (P<0.05; Table 4).

At the genus level, Prevotella, Succinivibrio, F082, and Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group were the dominant genera with relative abundances higher than 5% in both of the RF and MRF groups; For the FRF group, Streptococcus, Bacteroides, Megasphaera, Prevotella, Succinivibrio, and Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group were the dominant genera. For the CRF group, Succinivibrio, Prevotella, and Megasphaera were the dominant genera. The relative abundances of Prevotella, F082, and Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group in the CRF group were significantly lower than that in the RF and MRF groups (p < 0.05). In addition, the abundance of Succinivibrio in the CRF group was significantly higher than that in the RF and MRF groups by 5.4 and 1.9 times, respectively (p < 0.05); the relative abundance of Megasphaera in the CRF group was significantly higher than that in the RF and MFR groups by 25.5 and 9.1 times, respectively (p < 0.05; Table 5).

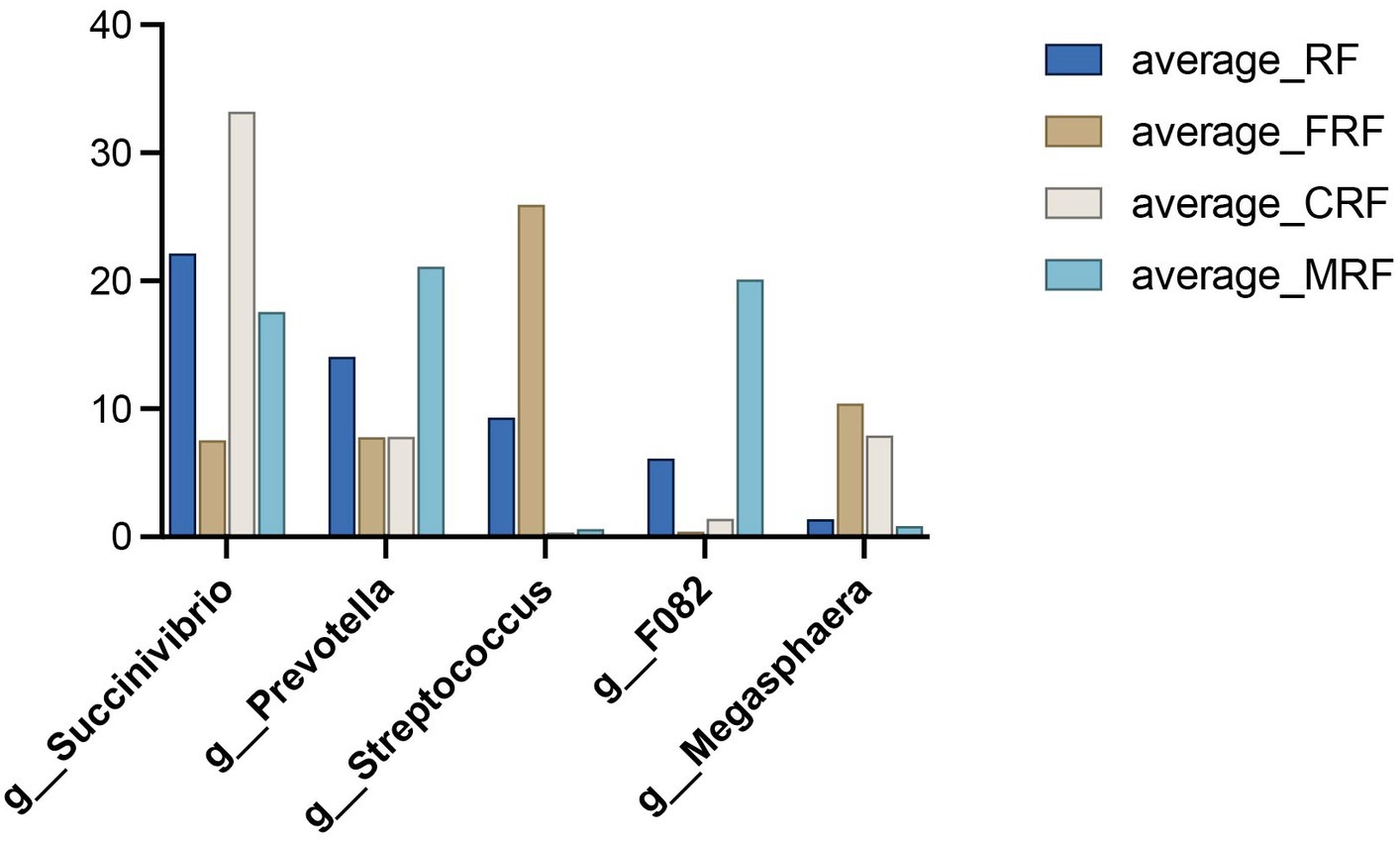

3.6 Core bacteria in rumen fluid after batch culture in vitro

The core bacteria refer to the bacteria that exist in over 80% of all the samples. We observed that 155 OTUs out of the total 2,261 OTUs were core bacteria in all samples, and these core OTUs accounted for 77.5, 86.9, 90.1, and 85.0% in the abundance in the RF, FRF, CRF, and MRF groups, respectively. Moreover, the core bacteria that were identified mainly belonged to the five dominant genera, namely, Succinivibrio, Prevotella, Streptococcus, F082, and Megasphaera, whose average abundances among all samples were 20.1, 12.7, 9.1, 7.0, and 5.1%, respectively. In the CRF group, the core bacteria of Succinivibrio, Prevotella, and Megasphaera were effectively retained after 23 days of continuous batch culture, and the abundance of Succinivibrio was significantly higher than that in the other three groups (p < 0.05; Figure 6).

Figure 6. Relative abundance of core bacteria between groups. RF, Fresh rumen fluid; FRF, Frozen rumen fluid; CRF: Continuously batch-cultured rumen fluid; MRF, Mixed rumen fluid by 1/4 CRF and 3/4 RF.

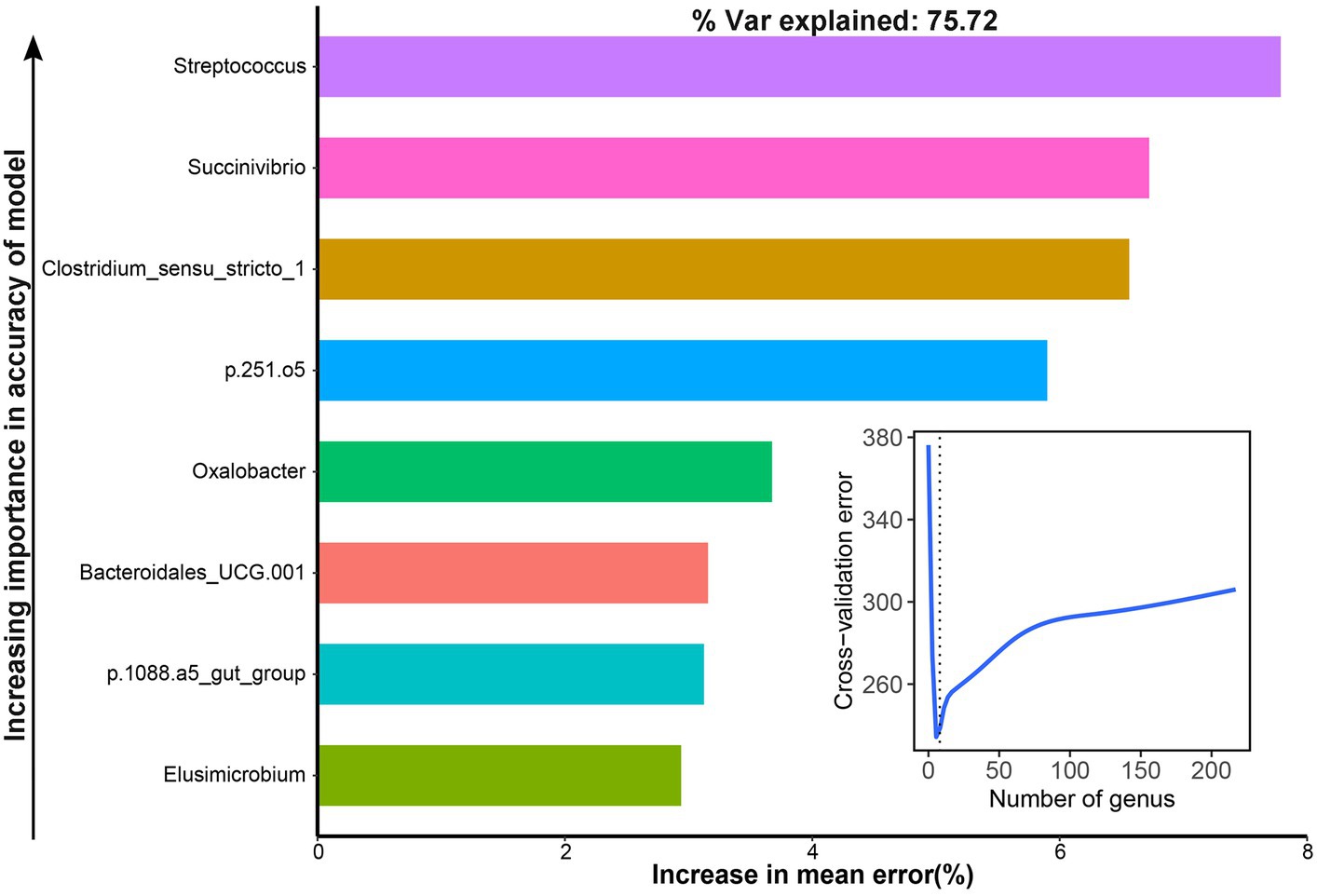

3.7 Prediction of bacterial taxa associated with the NH3-N utilization efficiency

The area under the curve (AUC) was used to identify bacterial taxa that were associated with the NH3-N utilization efficiency. We observed that eight genera were highly associated with the AUC of dynamic changes in NH3-N content by cross-validating the error curves, including Streptococcus, Succinivibrio, Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1, p.251.o5, Oxalobacter, Bacteroidales_UCG.001, p.1088.a5_gut_group, and Elusimicrobium, which could explain 75.72% of the variation of the AUC of dynamic change in NH3-N content in different groups (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Bacteria associated with the area under the curve (AUC) of dynamic changes of the NH3-N content with the RandomForest model.

4 Discussion

Gas production and dry matter digestibility are important indicators, reflecting the function of rumen (Pashaei et al., 2010; Zhang M. et al., 2022). Previous studies reported controversial effects of urea supplementation on gas production and dry matter digestibility (Salem et al., 2013; Spanghero et al., 2018; Muthia et al., 2021; Kour et al., 2023), and we detected that bacterial counts decreased but gas production and dry matter digestibility were stable over a 23-day continuous batch culture of rumen microbiota under high urea condition. The theory of functional redundancy in rumen microbiota might support these observations (Wemheuer et al., 2020; Sasson et al., 2022), and we inferred that functional redundant microbes might be partially removed, while core bacteria associated with dry matter digestion might be preserved after 23 days of continuous batch culture.

We then looked into the changes in rumen microbiota after 23 days of continuous batch culture. We observed that microbial diversity significantly changed, but the majority of the removed microbes were non-core members, increasing the proportion of core bacteria. At the phylum level, Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria were the dominant phyla in all groups, which was consistent in previous studies (Li et al., 2020). At the genus level, the core bacteria were found mainly in five genera, namely, Succinivibrio, Prevotella, Streptococcus, F082, and Megasphaera. Among them, Succinivibrio was related to the utilization of soluble sugars to produce lactate, acetate, formate, and propionate (Li et al., 2020; Wang Y. et al., 2021; Wang Z. et al., 2021); Prevotella is a dominant rumen genus that plays important roles in nitrogen metabolism (Henderson et al., 2015) and hemicellulose degradation(Mizrahi et al., 2021); Streptococcus, as one of the dominant genera, belongs to acid-tolerant bacteria (Khafipour et al., 2009) and is negatively correlated with cellulose degradation (Chuang et al., 2020); F082 was found to be a core genus in rumen fluid and was sensitive to feed components (Hinsu et al., 2021; Choi et al., 2022), it has been reported that F082 is positively correlated with the propionate production (Ma et al., 2020); Megasphaera was often accompanied with Sharpea spp., which can increase butyrate production (Kamke et al., 2016). These findings indicated that bacterial composition might be significantly affected after continuous batch culture of rumen microbiota, and the core bacteria retained.

The nitrogen utilization efficiency of rumen microbiota can be directly reflected by the concentration of NH3-N in rumen fluid (Patra and Aschenbach, 2018; Guo et al., 2022), and it has been shown that the addition of non-protein nitrogen to the diet significantly increased the NH3-N concentration in the rumen (Xu et al., 2019). Microbiota in the rumen was able to fully utilize NH3-N to synthesize MCP when NH3-N concentrations ranged from 6.3 to 27.5 mg/dL (Satter and Slyter, 1974; Murphy and Kennelly, 1987). In the current study, when 5% urea was added to the diet, the NH3-N concentrations of all groups were higher than the maximum suitable concentration (27.5 mg/dL), but a significant reduction in ammoniacal nitrogen was found after continuous batch culture of rumen microbiota, which might be caused by the adaptive evolution of microbial communities in the rumen after continuous batch culture of rumen microbiota under high urea condition. Additionally, we also observed that the nitrogen utilization efficiency of the mixture of fresh rumen fluid and continuously batch-cultured rumen fluid (3 of 4 fresh rumen fluid mixed with 1 of 4 continuously batch-cultured rumen fluid) was also enhanced, which indicated that the nitrogen utilization efficiency might also be enhanced by rumen microbiota transplantation with only a portion of rumen fluid was replaced in the rumen (DePeters and George, 2014; Yin et al., 2021).

We then looked into the core bacteria potentially associated with the NH3-N utilization efficiency. After 23 days of continuous batch culture, the urea treatment led to an increase in the abundance of Proteobacteria and a decrease in the abundance of Bacteroidota, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies by adding 0.5% urea (Jin et al., 2016). Proteobacteria exhibited the highest abundance after continuous batch culture under high urea concentration, which is always found in a disrupted rumen microbial ecology or an unstable gut microbial community structure (Shin et al., 2015), and this might be a limitation of the current in vitro continuous fermentation system; further research is still needed on the safety of applying artificially domesticated microbial populations. With the RandomForest model, we observed that Streptococcus, Succinivibrio, Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1, p.251.o5, Oxalobacter, Bacteroidales_UCG.001, and p.1088.a5_gut_group explained 75.72% of the variation in NH3-N utilization efficiency. Strains from Succinivibrio and Streptococcus could produce urease that catabolizes metabolized urea (Sissons and Hancock, 1993; Zotta et al., 2008; Pope et al., 2011), and Succinivibrio exhibited higher abundance in urea-added fermenters (Jin et al., 2016) and positively correlated with ammonia levels in the rumen (Zhang Y. et al., 2022). Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1 was also related to nitrogen utilization (Zhou et al., 2021) and positively correlated with ammonia concentration in the rumen (Chen et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023), which could convert nitrate into ammonia (Chen et al., 2023). There is also evidence that Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1 is positively correlated with a high-protein diet (Fan et al., 2017), indicating its possible involvement in protein degradation. The strains from p.251.o5 and Bacteroidales_UCG.001 had not been successfully cultured (Mu et al., 2022), and their functions were still unclear. Oxalobacter was found to be associated with oxalate metabolism (Stewart et al., 2004). The p.1088.a5_gut_group shows higher abundance in the rumen of goats with high ammonia nitrogen utilization efficiency (Li et al., 2019), indicating its potential role in ammonia utilization. Elusimicrobium is a type of ultramicrobacteria that can use nitrogen with group IV nitrogenase (Zheng et al., 2016; Shelomi et al., 2019). Thus, specific taxa have been found to contribute to the enhancement of NH3-N utilization efficiency in the rumen.

5 Conclusion

After continuous batch culture of rumen microbiota under high urea conditions, the core functions and bacterial taxa were retained, and the NH3-N utilization efficiency increased. Streptococcus, Succinivibrio, Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1, p.251.o5, Oxalobacter, Bacteroidales_UCG.001, and p.1088.a5_gut_group had been identified to contribute to the enhancement of NH3-N utilization efficiency. These findings indicated that we could achieve rumen microbiota with remaining core bacteria and function and increase NH3-N utilization efficiency by continuous batch culture of rumen microbiota in vitro, which would provide potential applications in improving the efficiency and safety of non-protein nitrogen utilization in ruminants by rumen microbiota transplantation or manipulating the bacterial composition.

Data availability statement

The 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing datasets for this study can be found in the China National Center for Bioinformation, accession number CRA013223.

Author contributions

ML: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. TW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. LW: Writing – review & editing. HX: Formal analysis, Software, Writing – review & editing. JL: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. CD: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. LG: Resources, Writing – review & editing. YL: Resources, Writing – review & editing. HY: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Resources, Writing – review & editing. SJ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the earmarked fund for CARS-38, Hebei Natural Science Foundation (C2022204232 and C2021204147), Hebei Grass Industry Technology System (HBCT2023160202).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdoun, K., Stumpff, F., and Martens, H. (2006). Ammonia and urea transport across the rumen epithelium: a review. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 7, 43–59. doi: 10.1017/S1466252307001156

Adejoro, F. A., Hassen, A., Akanmu, A. M., and Morgavi, D. P. (2020). Replacing urea with nitrate as a non-protein nitrogen source increases lambs' growth and reduces methane production, whereas acacia tannin has no effect. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 259:114360. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2019.114360

AOAC . (2016). Official methods of analysis of AOAC international. Rockville, MD: AOAC International.

Chen, Z., Zhang, C., Liu, Z., Song, C., and Xin, S. (2023). Effects of long-term (17 years) nitrogen input on soil bacterial Community in Sanjiang Plain: the largest marsh wetland in China. Microorganisms 11:1552. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11061552

Choi, Y., Lee, S. J., Kim, H. S., Eom, J. S., Jo, S. U., Guan, L. L., et al. (2022). Red seaweed extracts reduce methane production by altering rumen fermentation and microbial composition in vitro. Front. Vet. Sci. 9:985824. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.985824

Chuang, S.-T., Ho, S.-T., Tu, P.-W., Li, K.-Y., Kuo, Y.-L., Shiu, J.-S., et al. (2020). The rumen specific bacteriome in dry dairy cows and its possible relationship with phenotypes. Animals 10:1791. doi: 10.3390/ani10101791

DePeters, E., and George, L. (2014). Rumen transfaunation. Immunol. Lett. 162, 69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.05.009

Fan, P., Liu, P., Song, P., Chen, X., and Ma, X. (2017). Moderate dietary protein restriction alters the composition of gut microbiota and improves ileal barrier function in adult pig model. Sci. Rep. 7:43412. doi: 10.1038/srep43412

Fuller, M. F., and Reeds, P. J. (1998). Nitrogen cycling in the gut. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 18, 385–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.18.1.385

Gong, J., Li, L., Zuo, X., and Li, Y. (2019). Change of the duodenal mucosa-associated microbiota is related to intestinal metaplasia. BMC Microbiol. 19, 275–277. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1666-5

Guo, Y., Xiao, L., Jin, L., Yan, S., Niu, D., and Yang, W. (2022). Effect of commercial slow-release urea product on in vitro rumen fermentation and ruminal microbial community using RUSITEC technique. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 13:56. doi: 10.1186/s40104-022-00700-8

Henderson, G., Cox, F., Ganesh, S., Jonker, A., Young, W., and Janssen, P. H. (2015). Rumen microbial community composition varies with diet and host, but a core microbiome is found across a wide geographical range. Sci. Rep. 5:14567. doi: 10.1038/srep14567

Hinsu, A. T., Tulsani, N. J., Panchal, K. J., Pandit, R. J., Jyotsana, B., Dafale, N. A., et al. (2021). Characterizing rumen microbiota and CAZyme profile of Indian dromedary camel (Camelus dromedarius) in response to different roughages. Sci. Rep. 11:9400. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88943-9

Jin, D., Zhao, S., Wang, P., Zheng, N., Bu, D., Beckers, Y., et al. (2016). Insights into abundant rumen ureolytic bacterial community using rumen simulation system. Front. Microbiol. 7:1006. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01006

Jin, D., Zhao, S., Zheng, N., Beckers, Y., and Wang, J. (2018). Urea metabolism and regulation by rumen bacterial urease in ruminants–a review. Ann. Anim. Sci. 18, 303–318. doi: 10.1515/aoas-2017-0028

Kamke, J., Kittelmann, S., Soni, P., Li, Y., Tavendale, M., Ganesh, S., et al. (2016). Rumen metagenome and metatranscriptome analyses of low methane yield sheep reveals a Sharpea-enriched microbiome characterised by lactic acid formation and utilisation. Microbiome 4, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0201-2

Kertz, A. (2010). Urea feeding to dairy cattle: a historical perspective and review. Prof. Anim. Sci. 26, 257–272. doi: 10.15232/S1080-7446(15)30593-3

Khafipour, E., Li, S., Plaizier, J. C., and Krause, D. O. (2009). Rumen microbiome composition determined using two nutritional models of subacute ruminal acidosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 7115–7124. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00739-09

Kim, S. W., Less, J. F., Wang, L., Yan, T., Kiron, V., Kaushik, S. J., et al. (2019). Meeting global feed protein demand: challenge, opportunity, and strategy. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 7, 221–243. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-030117-014838

Kim, H. S., Whon, T. W., Sung, H., Jeong, Y.-S., Jung, E. S., Shin, N.-R., et al. (2021). Longitudinal evaluation of fecal microbiota transplantation for ameliorating calf diarrhea and improving growth performance. Nat. Commun. 12:161. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20389-5

Kour, M., Lamba, J. S., Grewal, R. S., Chahal, U. S., Malhotra, P., and Nayyar, S. (2023). Effect of urea, biological inoculant, molasses and Fiber degrading enzymes on in vitro ruminal fermentation of Paddy straw silage. J. Anim. Res. 13, 63–70. doi: 10.30954/2277-940X.01.2023.8

Lee, C. H., Steiner, T., Petrof, E. O., Smieja, M., Roscoe, D., Nematallah, A., et al. (2016). Frozen vs fresh fecal microbiota transplantation and clinical resolution of diarrhea in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 315, 142–149. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18098

Li, J., Yan, H., Chen, J., Duan, C., Guo, Y., Liu, Y., et al. (2022). Correlation of Ruminal Fermentation Parameters and Rumen Bacterial Community by Comparing Those of the Goat, Sheep, and Cow In Vitro. Fermentation 8:427.

Li, Y., Lv, M., Wang, J., Tian, Z., Yu, B., Wang, B., et al. (2020). Dandelion (Taraxacum mongolicum hand.-Mazz.) supplementation-enhanced rumen fermentation through the interaction between ruminal microbiome and metabolome. Microorganisms 9:83. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9010083

Li, Q., Wang, L., Wang, Z., Xue, B., and Peng, Q. (2019). Differences of bacterial structure and composition in rumen of goats with different nitrogen utilization. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 31, 3651–3663. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-267x.2019.08.026

Liu, J., Li, H., Zhu, W., and Mao, S. (2019). Dynamic changes in rumen fermentation and bacterial community following rumen fluid transplantation in a sheep model of rumen acidosis: implications for rumen health in ruminants. FASEB J. 33, 8453–8467. doi: 10.1096/fj.201802456R

Lv, X., Chai, J., Diao, Q., Huang, W., Zhuang, Y., and Zhang, N. (2019). The signature microbiota drive rumen function shifts in goat kids introduced to solid diet regimes. Microorganisms 7:516. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms7110516

Ma, T., Wu, W., Tu, Y., Zhang, N., and Diao, Q. (2020). Resveratrol affects in vitro rumen fermentation, methane production and prokaryotic community composition in a time-and diet-specific manner. Microb. Biotechnol. 13, 1118–1131. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13566

Makkar, H., Sharma, O., Dawra, R., and Negi, S. (1982). Simple determination of microbial protein in rumen liquor. J. Dairy Sci. 65, 2170–2173. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(82)82477-6

Menke, K., Raab, L., and Salewski, A. (1979). The estimation of the digestibility and metabolizable energy content of ruminant feedingstuffs from the gas production when they are incubated with rumen liquor in vitro. J. Agric. Sci. 93, 217–222.

Mizrahi, I., Wallace, R. J., and Moraïs, S. (2021). The rumen microbiome: balancing food security and environmental impacts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 553–566. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00543-6

Mu, Y., Qi, W., Zhang, T., Zhang, J., and Mao, S. (2022). Multi-omics analysis revealed coordinated responses of rumen microbiome and epithelium to high-grain-induced subacute rumen acidosis in lactating dairy cows. Msystems 7, e01490–e01421. doi: 10.1128/msystems.01490-21

Muetzel, S., Lawrence, P., Hoffmann, E. M., and Becker, K. (2009). Evaluation of a stratified continuous rumen incubation system. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 151, 32–43. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2008.11.001

Murphy, J., and Kennelly, J. (1987). Effect of protein concentration and protein source on the degradability of dry matter and protein in situ. J. Dairy Sci. 70, 1841–1849. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(87)80223-0

Muthia, D., Ridla, M., Laconi, E., Ridwan, R., Fidriyanto, R., Abdelbagi, M., et al. (2021). Effects of ensiling, urea treatment and autoclaving on nutritive value and in-vitro rumen fermentation of rice straw. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci 9, 655–661. doi: 10.17582/journal.aavs/2021/9.5.655.661

Pashaei, S., Razmazar, V., and Mirshekar, R. (2010). Gas production: a proposed in vitro method to estimate the extent of digestion of a feedstuff in the rumen. J. Biol. Sci. 10, 573–580. doi: 10.3923/jbs.2010.573.580

Patra, A. K., and Aschenbach, J. R. (2018). Ureases in the gastrointestinal tracts of ruminant and monogastric animals and their implication in urea-N/ammonia metabolism: a review. J. Adv. Res. 13, 39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2018.02.005

Pope, P., Smith, W., Denman, S., Tringe, S., Barry, K., Hugenholtz, P., et al. (2011). Isolation of Succinivibrionaceae implicated in low methane emissions from Tammar wallabies. Science 333, 646–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1205760

Salem, A. Z., ZHOU, C. S., TAN, Z. L., Mellado, M., Salazar, M. C., Elghandopur, M. M. M. Y., et al. (2013). In vitro ruminal gas production kinetics of four fodder trees ensiled with or without molasses and urea. J. Integr. Agric. 12, 1234–1242. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(13)60438-4

Sasson, G., Moraïs, S., Kokou, F., Plate, K., Trautwein-Schult, A., Jami, E., et al. (2022). Metaproteome plasticity sheds light on the ecology of the rumen microbiome and its connection to host traits. ISME J. 16, 2610–2621. doi: 10.1038/s41396-022-01295-8

Satter, L., and Slyter, L. (1974). Effect of ammonia concentration on rumen microbial protein production in vitro. Br. J. Nutr. 32, 199–208. doi: 10.1079/BJN19740073

Shelomi, M., Lin, S.-S., and Liu, L.-Y. (2019). Transcriptome and microbiome of coconut rhinoceros beetle (Oryctes rhinoceros) larvae. BMC Genomics 20, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-6352-3

Shin, N.-R., Whon, T. W., and Bae, J.-W. (2015). Proteobacteria: microbial signature of dysbiosis in gut microbiota. Trends Biotechnol. 33, 496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.06.011

Sissons, C., and Hancock, E. (1993). Urease activity in Streptococcus salivarius at low pH. Arch. Oral Biol. 38, 507–516. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(93)90187-Q

Spanghero, M., Nikulina, A., and Mason, F. (2018). Use of an in vitro gas production procedure to evaluate rumen slow-release urea products. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 237, 19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2017.12.017

Stewart, C. S., Duncan, S. H., and Cave, D. R. (2004). Oxalobacter formigenes and its role in oxalate metabolism in the human gut. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 230, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00864-4

Wang, B., Ma, T., Deng, K. D., Jiang, C. G., and Diao, Q. Y. (2016). Effect of urea supplementation on performance and safety in diets of Dorper crossbred sheep. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 100, 902–910. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12417

Wang, Y., Nan, X., Zhao, Y., Jiang, L., Wang, H., Zhang, F., et al. (2021). Dietary supplementation of inulin ameliorates subclinical mastitis via regulation of rumen microbial community and metabolites in dairy cows. Microbiol. Spectr. 9, e00105–e00121. doi: 10.1128/Spectrum.00105-21

Wang, M., Tang, S., and Tan, Z. (2011). Modeling in vitro gas production kinetics: derivation of logistic–exponential (LE) equations and comparison of models. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 165, 137–150. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2010.09.016

Wang, Z., Yu, Y., Li, X., Xiao, H., Zhang, P., Shen, W., et al. (2021). Fermented soybean meal replacement in the diet of lactating Holstein dairy cows: modulated rumen fermentation and ruminal microflora. Front. Microbiol. 12:625857. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.625857

Wemheuer, F., Taylor, J. A., Daniel, R., Johnston, E., Meinicke, P., Thomas, T., et al. (2020). Tax4Fun2: prediction of habitat-specific functional profiles and functional redundancy based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Environ. Microbiome 15, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s40793-020-00358-7

Xu, Y., Li, Z., Moraes, L. E., Shen, J., Yu, Z., and Zhu, W. (2019). Effects of incremental urea supplementation on rumen fermentation, nutrient digestion, plasma metabolites, and growth performance in fattening lambs. Animals 9:652. doi: 10.3390/ani9090652

Yin, X., Ji, S., Duan, C., Ju, S., Zhang, Y., Yan, H., et al. (2021). Rumen fluid transplantation affects growth performance of weaned lambs by altering gastrointestinal microbiota, immune function and feed digestibility. Animal 15:100076. doi: 10.1016/j.animal.2020.100076

Zhang, S., Cheng, L., Guo, X., Ma, C., Guo, A., and Moonsan, Y. (2016). Effects of urea supplementation on rumen fermentation characteristics and protozoa population in vitro. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 44, 1–4. doi: 10.1080/09712119.2014.978779

Zhang, M., Liang, G., Zhang, X., Lu, X., Li, S., Wang, X., et al. (2022). The gas production, ruminal fermentation parameters, and microbiota in response to Clostridium butyricum supplementation on in vitro varying with media ph levels. Front. Microbiol. 13:960623. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.960623

Zhang, Y., Wang, B., Wei, D., Guo, Y., Du, M., and Zhang, G. (2022). Supplementation of Lycium barbarum residue improves the animal performance through the interaction of rumen microbiota and metabolome of Tan sheep.

Zhao, J., Liu, H., Yin, X., Li, J., Dong, Z., Wang, S., et al. (2023). Relationships between microbial community, functional profile and fermentation quality during ensiling of hybrid Pennisetum. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 32, 447–458. doi: 10.22358/jafs/161778/2023

Zheng, H., Dietrich, C., Radek, R., and Brune, A. (2016). Endomicrobium proavitum, the first isolate of Endomicrobia class. Nov.(phylum Elusimicrobia)–an ultramicrobacterium with an unusual cell cycle that fixes nitrogen with a group IV nitrogenase. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 191–204. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12960

Zhou, S., Geng, B., Li, M., Li, Z., Liu, X., and Guo, H. (2021). Comprehensive analysis of environmental factors mediated microbial community succession in nitrogen conversion and utilization of ex situ fermentation system. Sci. Total Environ. 769:145219. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145219

Keywords: core microbiota, continuous batch culture, ammonia utilization, rumen, NH3-N utilization efficiency

Citation: Liu M, Wang T, Wang L, Xiao H, Li J, Duan C, Gao L, Liu Y, Yan H, Zhang Y and Ji S (2024) Core microbiota for nutrient digestion remained and ammonia utilization increased after continuous batch culture of rumen microbiota in vitro. Front. Microbiol. 15:1331977. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1331977

Edited by:

Anusorn Cherdthong, Khon Kaen University, ThailandReviewed by:

Benjamad Khonkhaeng, Rajamangala University of Technology Isan, ThailandRayudika Aprilia Patindra Purba, Suranaree University of Technology, Thailand

Copyright © 2024 Liu, Wang, Wang, Xiao, Li, Duan, Gao, Liu, Yan, Zhang and Ji. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hui Yan, eWFuaHVpaHVpQDEyNi5jb20=; Yingjie Zhang, Wmhhbmd5aW5namllNjZAMTI2LmNvbQ==; Shoukun Ji, amlzaG91a3VuQDE2My5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Mengyu Liu†

Mengyu Liu† Hanjie Xiao

Hanjie Xiao Hui Yan

Hui Yan Yingjie Zhang

Yingjie Zhang Shoukun Ji

Shoukun Ji