- 1Department of Breast Surgery, Guangxi Medical University Cancer Hospital, Nanning, China

- 2Department of Breast Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Hainan Medical University, Haikou, China

- 3Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Hainan Medical University, Haikou, China

Background: The relationship between gut microbiota and breast cancer has been extensively studied; however, changes in gut microbiota after breast cancer surgery are still largely unknown.

Materials and methods: A total of 20 patients with breast cancer underwent routine open surgery at the First Affiliated Hospital of Hainan Medical College from 1 June 2022 to 1 December 2022. Stool samples were collected from the patients undergoing mastectomy for breast cancer preoperatively, 3 days later, and 7 days later postoperatively. The stool samples were subjected to 16s rRNA sequencing.

Results: Surgery did not affect the α-diversity of gut microbiota. The β-diversity and composition of gut microorganisms were significantly affected by surgery in breast cancer patients. Both linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis and between-group differences analysis showed that surgery led to a decrease in the abundance of Firmicutes and Lachnospiraceae and an increase in the abundance of Proteobacteria and Enterobacteriaceae. Moreover, 127 differential metabolites were screened and classified into 5 categories based on their changing trends. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis showed significant changes in the phenylalanine metabolic pathway and exogenous substance metabolic pathway. Eight characterized metabolites were screened using ROC analysis.

Conclusion: Our study found that breast cancer surgery significantly altered gut microbiota composition and metabolites, with a decrease in beneficial bacteria and an increase in potentially harmful bacteria. This underscores the importance of enhanced postoperative management to optimize gut microbiota.

Introduction

Breast cancer is a common malignant tumor, with an increasing incidence year by year (Azamjah et al., 2019). According to the latest data released by the World Health Organization, there are approximately 2.3 million new cases of breast cancer globally each year, with women accounting for 99.5%. An estimated 685,000 women died from breast cancer in 2020 (Arnold et al., 2022). The incidence rate and mortality rate of breast cancer in some developed countries and regions are relatively high, which may be related to lifestyle and eating habits (Yap et al., 2019). Meanwhile, many challenges exist in developing countries and regions, including insufficient medical resources and outdated technology, which further exacerbate the impact of breast cancer (Ghoncheh et al., 2016).

Mastectomy is a surgical procedure that primarily aims to preserve the appearance and function of the breast while removing the tumor and its surrounding tissue (ElSherif et al., 2023). Breast preservation surgery is indicated for patients with early-stage breast cancer and typically requires a combination of radiation and chemotherapy to reduce the risk of recurrence. Although mastectomy is an effective treatment for breast cancer, patients may experience postoperative depression, which can stem from several reasons, including changes in body image, fear of the disease, pain, and discomfort (Wu et al., 2023). Additionally, during radical breast cancer surgery, if the aseptic operation is not strictly followed or if the patient’s own body resistance is relatively poor, postoperative sequelae such as wound infection and prolonged wound healing may occur (Jorgensen et al., 2023). If the patient’s condition is relatively serious and the pectoralis major muscle is injured during the operation, muscle abnormalities may occur, and vitamin B1 and vitamin B12 supplementation are necessary (Punchai et al., 2017). Therefore, post-mastectomy patients are required to pay special attention to multiple aspects, including wound care, psychological adjustment, and dietary adjustment.

The gut microbiota plays an important role in maintaining host health (Yang et al., 2023). The prevalence of bacterial infection in patients with breast cancer is typically characterized by reduced microbial diversity and changes in microbial composition (Alvarez-Mercado et al., 2023; Caleca et al., 2023). The gut microbiota can produce a multitude of metabolites that interact with the host, including vitamins B12, 5-hydroxytryptamine, and phenylalanine (Kiecka et al., 2023). A clinical study revealed a significant change in the total number of fecal bacteria and the absolute counts of Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria in breast cancer patients (Toumazi et al., 2021). It has been shown that gut microbes are involved in estrogen metabolism, determine estrogen levels in the circulatory system, and may also be responsible for the development of breast cancer (Feng et al., 2021; Marino et al., 2022).

However, there is a lack of knowledge regarding the impact of mastectomy on the gut microbiota and its metabolites in breast cancer patients. The aim of this paper is to investigate the alterations in the diversity and composition of the gut microbiota of breast cancer patients after surgery, as well as to analyze the changes in microbial metabolites using the metabolome technique.

Materials and methods

Patients

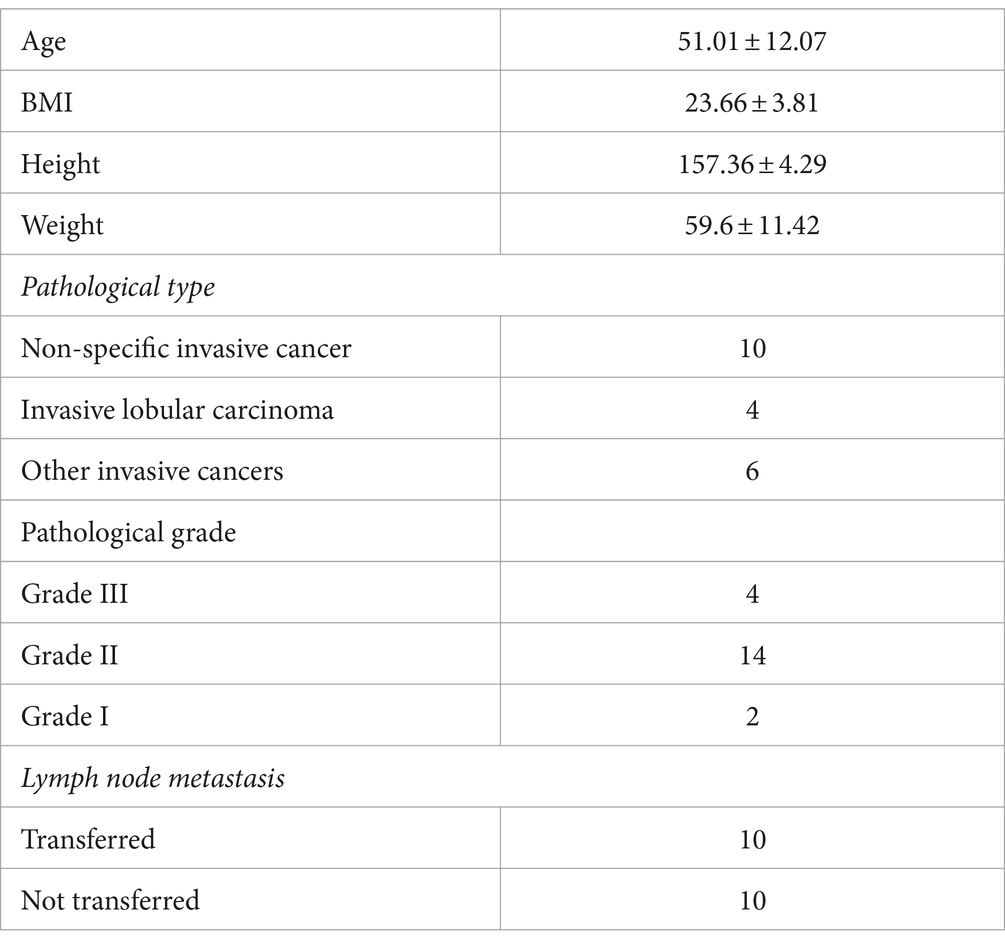

A total of 20 patients with breast cancer underwent open surgery at the First Affiliated Hospital of Hainan Medical College between 1 June 2022 and 1 December 2022. The patients ranged in age from 38 to 76 years, with a mean age of 52.01, and their BMI ranged from 18.2 to 33.3, with a mean value of 24.16 (Table 1). Prior to sampling, none of the patients had received antibiotic treatment for at least a month.

Fecal samples were collected from patients undergoing mastectomy for breast cancer preoperatively (KF0 group), 3 days later (KF3 group), and 7 days later (KF7 group) postoperatively. A total of 60 samples were collected, each containing 5 g. After collection, the stool samples were quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and transferred to a refrigerator at −80°C for storage.

DNA extraction and 16s rRNA sequencing

The DNA of the sample was extracted using the CTAB method. The concentration of the DNA was measured using a NanoDrop 2000. A suitable amount of the sample was taken into a centrifuge tube and diluted with sterile water to a concentration of 1 ng/ul. The primers for the 16S rDNA V4 region were as follows: 515F: GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA; 806R: GGACTACNNGGGGTATCTAAT. A library was constructed using the TruSeqR DNA PCR Free Sample Preparation Kit. The library was quantified using a Life Invitrogen Qubit 3.0 and library assay. The sequencing was performed on a HiSeq2500 platform after passing the assay.

Analysis of 16s rRNA sequencing data

All analyses of the data were performed on the Majorbio platform.1 Sequence splicing between bipartite pairs was conducted using the Flash software. The abundance tables for each taxonomy were generated using QIIME software and calculated using beta diversity distances. The OTU statistics were performed using Usearch. The rRNA database comparison annotation was performed by Greengenes. Intergroup difference analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Bacterial taxa with significant differences in abundance from phylum to genus level between groups were identified using the linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) (LDA > 2, p < 0.05).

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 21.0 and Excel. Data were expressed as means ± standard deviations and compared using an independent sample t-test. A one-way ANOVA was used to compare multiple groups, with p-values set at <0.05. The Chi-square test was used for counting information, with p-values set at <0.05.

Results

Effect of mastectomy on the α-diversity of gut microbiota in breast cancer patients

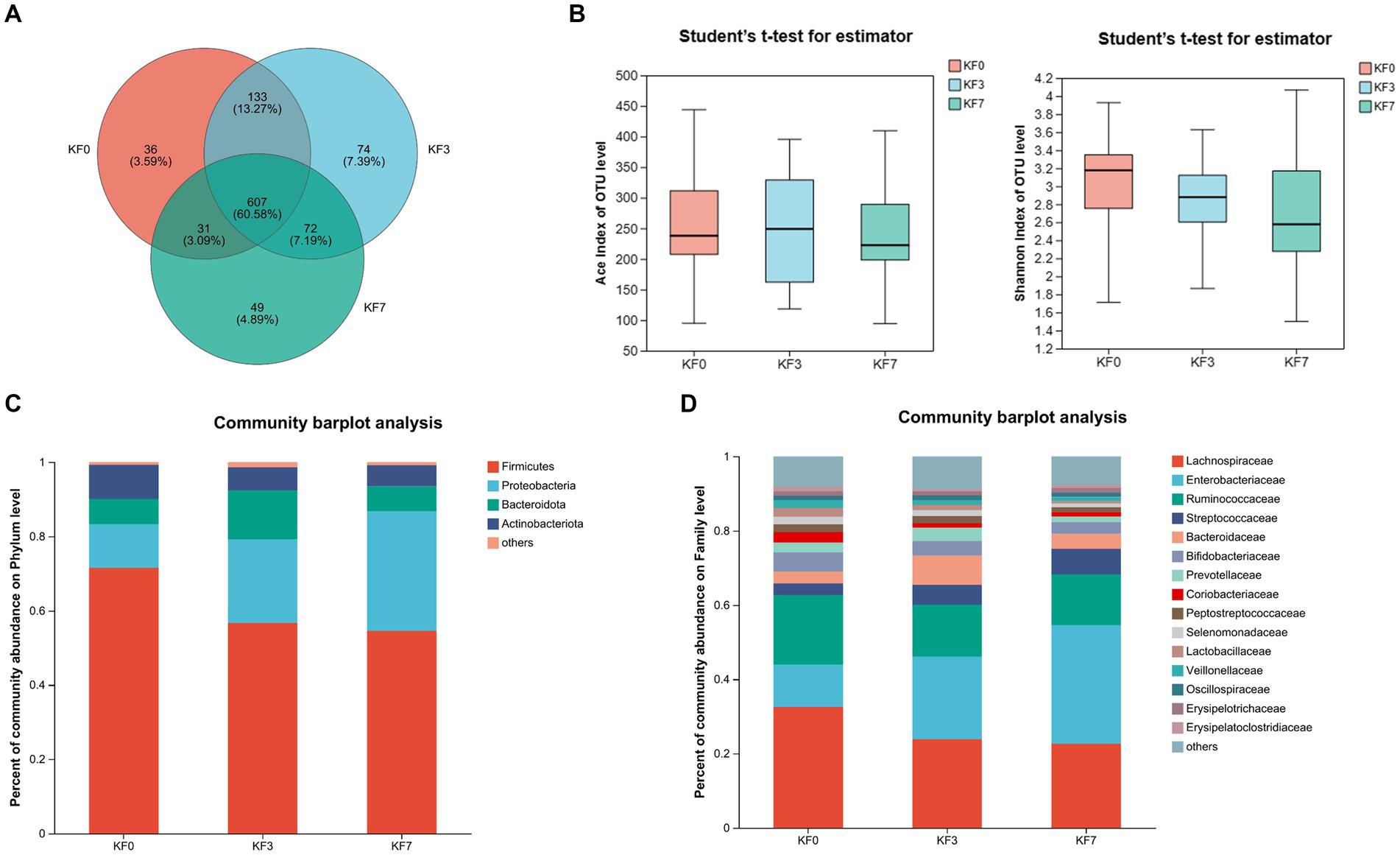

To study the effect of mastectomy on the gut microbiota of breast cancer patients, fecal samples from patients before and after surgery were collected and analyzed using 16s rRNA sequencing. The operational taxonomic unit (OTU) analysis showed that there were 807, 886, and 759 OTUs in the KF0, KF3, and KF7 groups, respectively (Figure 1A). The α-diversity analysis of the gut microbiota of patients 3 and 7 days after surgery showed that the ACE index and Shannon index were not significantly different among groups (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Changes in the α-diversity and composition of the gut microbiota of patients after open surgery in breast cancer patients. (A) Venn diagram of gut microbiota composition analysis. (B) Alpha diversity analysis, including the ACE index and Shannon index. Gut microbiota composition at (C) phylum level and (D) family level.

Effect of mastectomy on the composition of gut microbiota in breast cancer patients

The composition of the intestinal microbiota community of the patients was further analyzed. The dominant bacteria at the phylum level were Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroides, and Actinobacteria (Figure 1C). The abundance of Firmicutes and Proteobacteria accounted for 83.31% of the total phyla. Moreover, Lachnospiraceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and Ruminococcaceae were the dominant families, with the abundance of these three families accounting for more than 60% of the total (Figure 1D).

To analyze the effect of surgery on the β-diversity of the gut microbiota of breast cancer patients, the Partial Least-Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) was performed. The KF0, KF3, and KF7 groups were partially overlapping and could be distinguished from each other (Supplementary Figure S1).

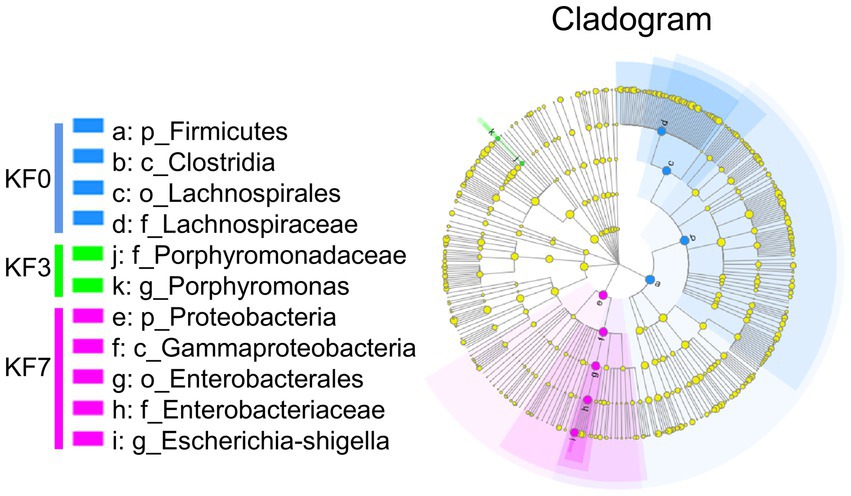

Screening of characteristic bacteria using the LEfSe analysis led to the identification of two groups of significantly different bacteria in abundance, including p_Firmicutes-c_Clostridia-o_Lachnospirale-f_Lachnospiraceae and p_Proteobacteria-c_Gammaproteobacteria-o_Enterobacterales-f_Enterobacteriaceae (Figure 2).

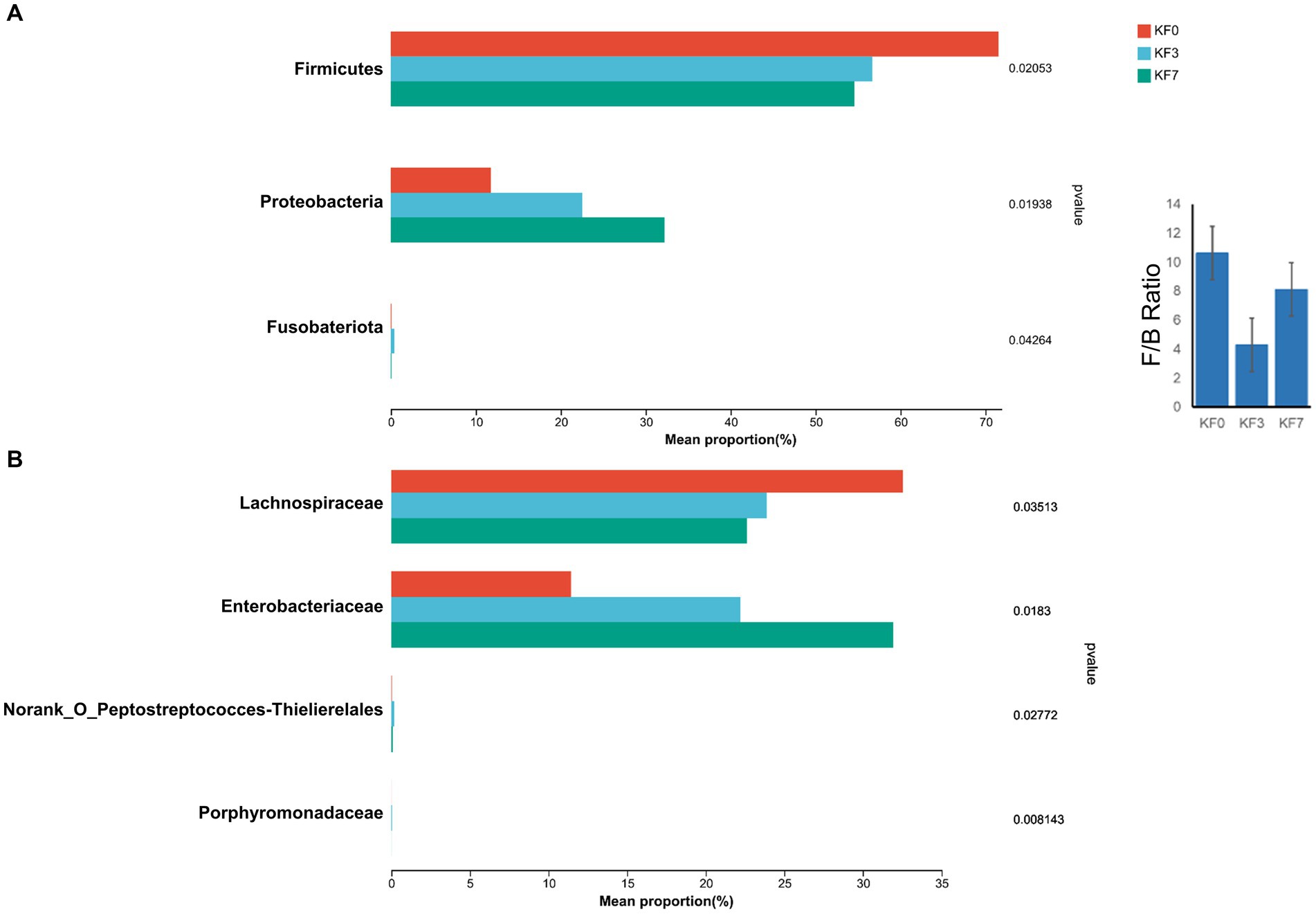

To identify bacteria with significant differences, the Kruskal–Wallis H-test analysis was performed. Significant differences were found in three bacterial phyla. Firmicutes were significantly decreased, while Proteobacteria and Fusobacteriotes were significantly increased (Figure 3A). Additionally, the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroides was significantly lower in the KF3 and KF7 groups than the KF0 group. At the family level, the abundance of Lachnospiraceae was significantly decreased, while that of Enterobacteriaceae and Norank_O_Peptostreptococces-Thielierelales was significantly increased (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Differential bacterial analysis after open surgery in breast cancer patients. (A) Phylum level and (B) Family level after open surgery.

Effect of mastectomy on the metabolism of gut microbiota in patients with breast cancer

As shown in Supplementary Figure S2, significant differences in metabolite concentrations between groups were demonstrated using volcano plots. In the positive ion mode, 102 different metabolites were identified between KF0 and KF3, while 91 different metabolites were observed between KF0 and KF7. In the negative ion mode, 25 different metabolites were observed in KF3, and 54 different metabolites were found in KF7, compared to KF0.

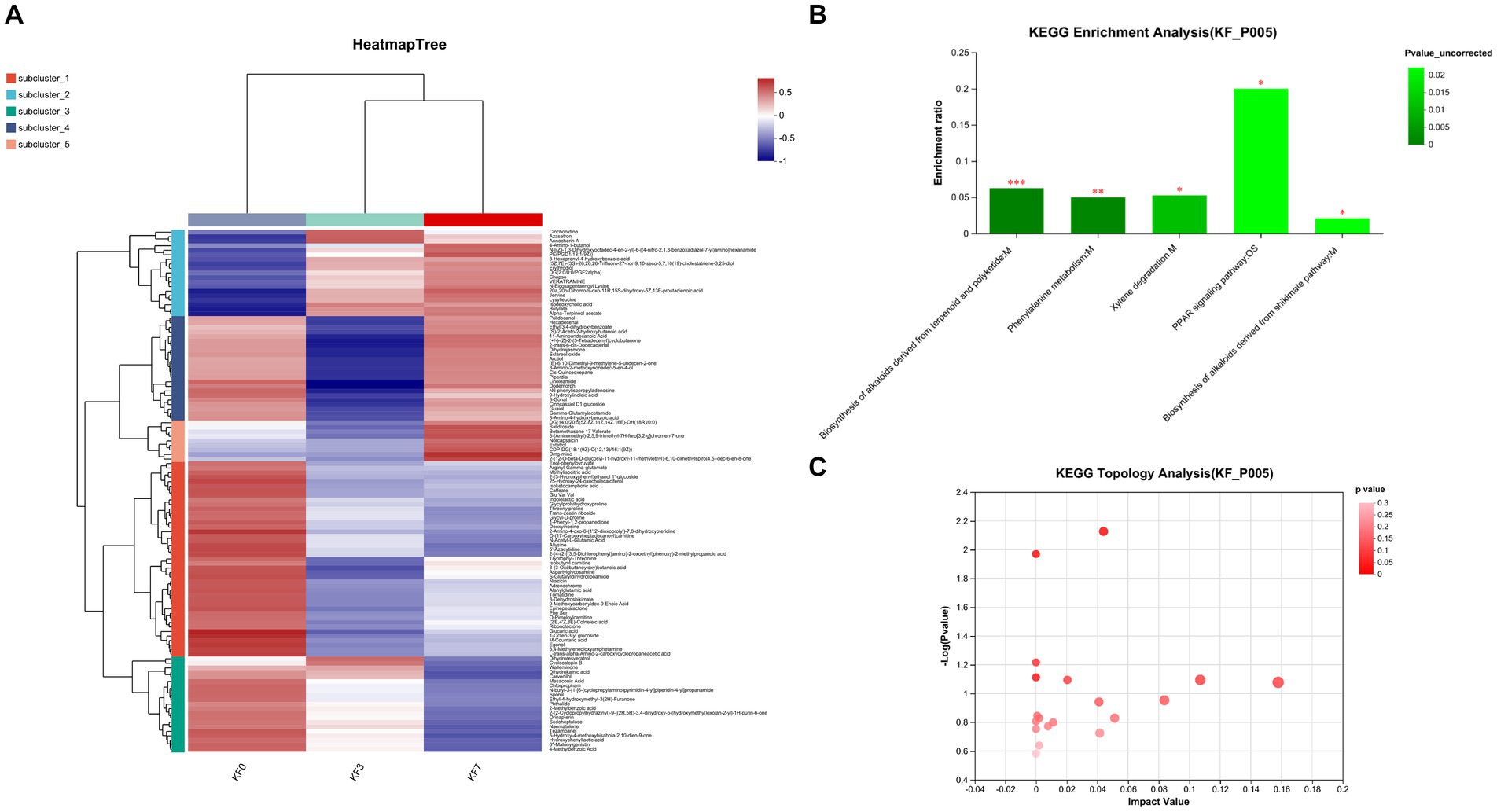

As shown in Figure 4A, the clustering analysis of differential metabolites can be divided into five clusters. Cluster 1 consisted of 43 metabolites, including phenylpyruvic acid enol, arginine γ-glutamic acid, methylisocitric acid, 2-(3-hydroxyphenyl)ethanol 1′-glucose, and 25-hydroxy-24-oxocholecalciferol, whose abundance decreased after surgery. Cluster 2 consisted of 19 metabolites, including cinchonidine, lysine leucine, isodeoxycholic acid, butyl ester, and alpha-pinoresinol acetate, whose abundance increased after surgery. Cluster 3 consisted of 21 metabolites, including phthalates, dihydroresveratrol, 2-methylbenzoic acid, and 4-methylbenzoic acid, whose abundance decreased with postoperative time. Cluster 4 consisted of 23 metabolites, including 9-hydroxylinoleic acid, γ-glutamyl acetamide, and linoleic acid amide, whose abundance decreased significantly at 3 days postoperatively and returned to preoperative levels at 7 days postoperatively. Cluster 5 consisted of 9 metabolites, including rhodiola rosea glycosides and desmethyl capsaicin, which significantly increased in abundance 7 days postoperatively.

Figure 4. Changes in the metabolites of gut microbiota after open surgery in breast cancer patients. (A) Differential metabolite clustering analysis. (B) KEGG functional pathway enrichment analysis and (C) KEGG topology analysis.

The analysis of the KEGG functional pathway indicated that five significant signaling pathways were enriched, namely the biosynthesis of terpene and polyketide alkaloids, phenylalanine metabolism, xylene degradation, the PPAR signaling pathway, and the mangiferic acid alkaloid biosynthesis pathway (Figure 4B). The topology analysis also showed significant changes in the phenylalanine metabolism and xylene degradation pathways (Figure 4C).

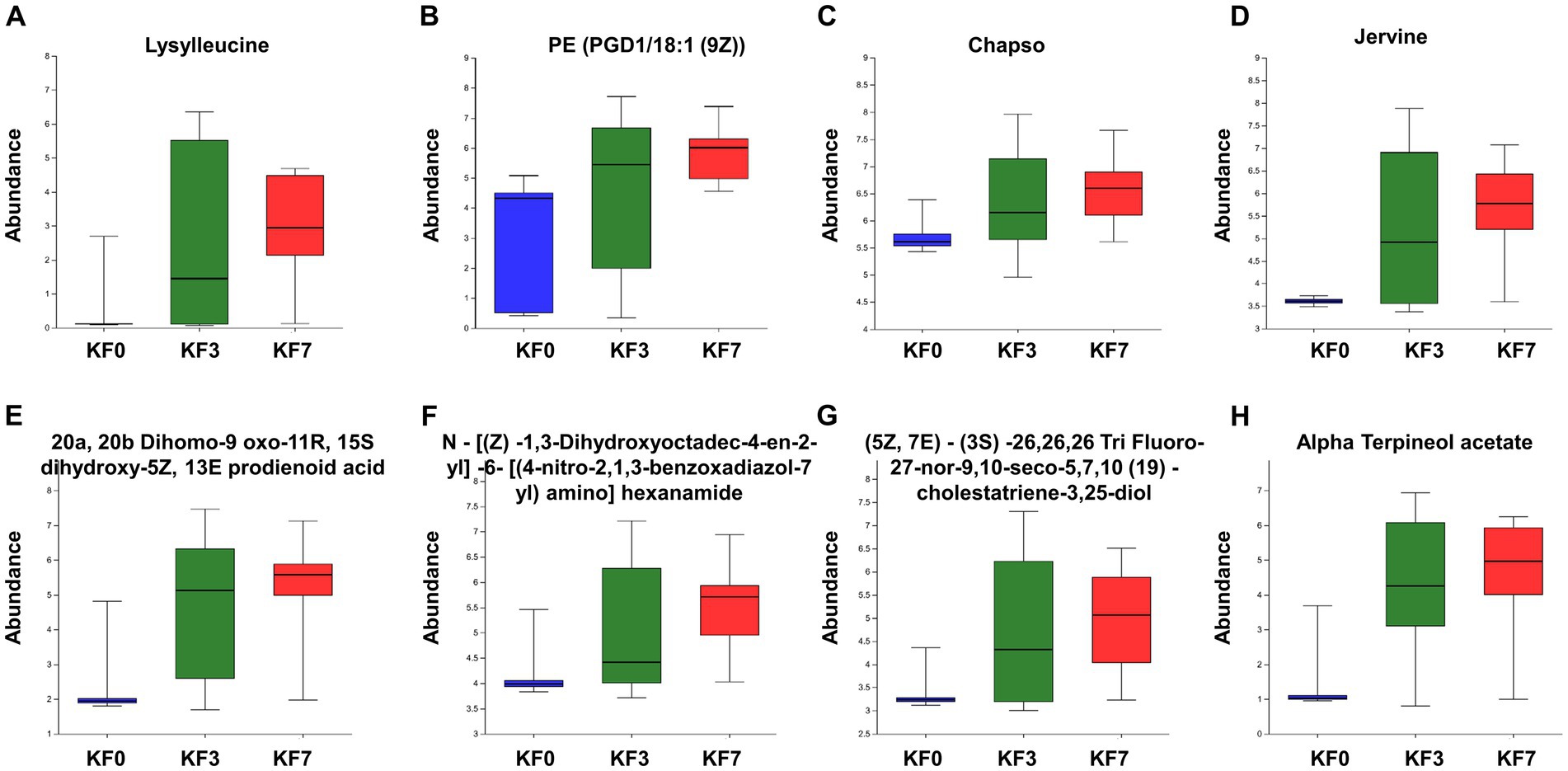

The ROC analysis identified eight important differential metabolites (Supplementary Figure S3), namely Lysylleucine, PE(PGD1/18:1 (9Z)), 20a,20b-dihomo-9-oxo-11R,15S-dihydroxy-5Z,13E-prodienoid acid, N-[(Z)-1,3-dihydroxyoctadec-4-en-2-yl]-6-[(4-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-7-yl)amino]hexanamide, Jervine, (5Z,7E)-(3S)-26,26,26-tri-fluoro-27-nor-9,10-seco-5,7,10 (19)-cholestatriene-3,25-diol, Chapso, and Alpha-terpineol acetate. The abundance of these eight differential metabolites gradually increased at 3 and 7 days after surgery, compared to before surgery (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Abundance of characteristic metabolites. (A) Lysylleucine, (B) PE(PGD1/18:1(9Z)), (C) 20a,20b-dihomo-9-oxo-11R,15S-dihydroxy-5Z,13E-prostadienoic acid, (D) N-[(Z)-1,3-dihydroxyoctadec-4-en-2-yl]-6-[(4-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-7-yl)amino]hexanamide, (E) Jervine, (F) (5Z,7E)-(3S)-26,26,26-trifluoro-27-nor-9,10-seco-5,7,10(19)-cholestatriene-3,25-diol, (G) Chapso, and (H) Alpha-terpineol acetate.

Discussion

Several studies have demonstrated a correlation between the gut microbiota and breast cancer. These studies have demonstrated that the microbiota can enhance the metabolism of estrogen and induce inflammation (Bodai and Nakata, 2020; Arnone and Cook, 2022). The aim of this study is to analyze the changes in the gut microbiota and its metabolite abundance in patients with breast cancer following mastectomy.

A limited number of studies have analyzed changes in the microbiota after surgical treatment for oncologic diseases (Tong et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2022; Hajjar et al., 2023). Research has shown that the microbial community after surgery is similar to that of healthy individuals, which can promote the recovery of tumor patients (Wolfe and Markey, 2022). A follow-up study found that changes in the gut microbiota can be considered potential biomarkers for tumor recurrence and can be used to stratify the risk of recurrence (Peters et al., 2019; Huo et al., 2022). It has also been shown that surgical procedures lead to higher rates of infection and are an important factor affecting the gut microbiota (Mu et al., 2019). Clinical trials have reported an increase in potential pathogenic bacteria after surgery (Mu et al., 2019). An animal study showed that cecum suturing induced postoperative intestinal obstruction, postoperative bacterial dysbiosis, and changes in β-diversity in guinea pigs (Wang et al., 2019). In the present study, α-diversity had no significant change, while the PLS-DA analysis showed that the KF3 and KF7 groups were significantly different from the KF0 group. Therefore, this study highlights that mastectomy for breast cancer can affect the diversity of the gut microbiota.

Firmicutes and Bacteroides are the two primary phyla of the gut microbiota in healthy adults, representing approximately 90% of the known gut microbiota (Sun et al., 2022). Firmicutes is crucial for maintaining human homeostasis, and dietary fiber is a significant factor influencing the abundance of Firmicutes in the intestine (Sun et al., 2022). Firmicutes can directly or indirectly utilize dietary fiber and produce metabolites such as acetic acid, butyric acid, and lactic acid during proliferation (James et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2022). Firmicutes can affect the host’s inflammatory response, intestinal permeability, glucose metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, and tryptophan metabolism (Sun et al., 2022). The Firmicutes–Bacteroides ratio was significantly lower in patients with breast cancer than in healthy controls (An et al., 2023). Lachnospiraceae can hydrolyze starch and other sugars, producing butyrate and other SCFAs (Zhang et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023). The reduced abundance of Lachnospiraceae and the resulting low butyrate production may be important in triggering the recurrence of colitis (Sasaki et al., 2019). Lachnospiraceae is positively correlated with the serum level of docosahexaenoic acid, which may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease death and breast cancer development (Toya et al., 2020; Memili et al., 2023). In the present study, the abundance of Firmicutes was significantly reduced in the KF3 and KF7 groups, along with a significant decrease in the Firmicutes–Bacteroides ratio. Meanwhile, the abundance of Lachnospiraceae decreased after surgery. Therefore, postoperative dietary modifications, such as dietary fiber intake, can be an important means to regulate the gut microbiota and promote the postoperative recovery of patients.

Proteobacteria is a widespread, harmful phylum that is associated with the development of various diseases (Rizzatti et al., 2017). Proteobacteria is more prevalent in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and it is an important causative agent of liver injury (Suppli et al., 2021). Proteobacteria are positively associated with intestinal inflammation (Lin et al., 2023). Levels of Proteobacteria are elevated in mice with colitis (Liu et al., 2023). Enterobacteriaceae is a family of Gram-negative bacteria that contains multiple species that are resistant to carbapenems, which can lead to an increase in mortality rates for various diseases, such as septic shock, bacteremia, endophthalmitis, and liver abscesses (Santos-Marques et al., 2022). Enterobacteriaceae was significantly increased in the type 2 diabetes group (Penckofer et al., 2020). In the present study, Proteobacteria and Enterobacteriaceae were significantly increased in the KF3 and KF7 groups. Therefore, intervention to suppress intestinal pathogenic bacteria may be a challenge for breast cancer surgery as well.

It has been observed that some patients with breast cancer exhibit emotional changes after undergoing surgery, including depressive symptoms (Wu et al., 2023). Breast cancer surgery is a major physical trauma for the patient, and coupled with the fear of cancer and uncertainty about their future, they are prone to mood fluctuations. Gut microbes are involved in the synthesis and metabolism of neurotransmitters such as phenylalanine, serotonin, and dopamine (Xu et al., 2022). Phenylalanine is a precursor of the catecholamines epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine. A recent study showed that phenylalanine may be involved in regulating the mental health of patients (Akimitsu et al., 2013). It has been shown that phenylalanine is significantly reduced in depressed patients (Sharman et al., 2012). In this study, the metabolomic analysis revealed that the phenylalanine metabolic pathway was significantly inhibited. Therefore, rational modification of the postoperative diet, such as increasing amino acid levels such as phenylalanine, might be a viable option to regulate the postoperative mental status of patients with breast cancer.

Conclusion

In summary, our results indicated that the diversity and composition of a patient’s gut microbiota were significantly affected 3 and 7 days after breast cancer surgery. Decreases in p_Firmicutes and f_Lachnospiraceae might result in decreased SCFA production. Increases in p_Proteobacteria and f_Enterobacteriaceae might be associated with disease and antibiotic resistance. Moreover, a significant number of metabolites changed significantly after breast cancer surgery. Therefore, it is necessary to further strengthen multimodal postoperative management, particularly the improvement of the gut microbiota.

Data availability statement

The data presented in the study are deposited in the SRA (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/) repository, accession number PRJNA1110396.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Hainan Medical College (2022llzm1175). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The manuscript presents research on animals that do not require ethical approval for their study.

Author contributions

PF: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LD: Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GD: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation. CW: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province (821MS0830 to PF). The funding organization had no role in the study design, data collection analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1269558/full#supplementary-material

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S1 | PLS-DA analysis was performed to analyze the effect of surgery on the β-diversity of gut microbiota of breast cancer patients.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S2 | Metabolite differences between groups were demonstrated by volcano plots.

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S3 | ROC analysis to screen characteristic metabolites and their expression. (A) Lysylleucine, (B) PE(PGD1/18:1(9Z)), (C) 20a,20b-dihomo-9-oxo-11R,15S-dihydroxy-5Z,13E-prostadienoic acid, (D) N-[(Z)-1,3-dihydroxyoctadec-4-en-2-yl]-6-[(4-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-7-yl)amino]hexanamide, (E) Jervine, (F) (5Z,7E)-(3S)-26,26,26-Trifluoro-27-nor-9,10-seco-5,7,10(19)-cholestatriene-3,25-diol, (G) Chapso, (H) alpha-terpineol acetate.

Footnotes

References

Akimitsu, O., Wada, K., Noji, T., Taniwaki, N., Krejci, M., Nakade, M., et al. (2013). The relationship between consumption of tyrosine and phenylalanine as precursors of catecholamine at breakfast and the circadian typology and mental health in Japanese infants aged 2 to 5 years. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 32:13. doi: 10.1186/1880-6805-32-13

Alvarez-Mercado, A. I., Del Valle, C. A., Fernandez, M. F., and Fontana, L. (2023). Gut microbiota and breast Cancer: the dual role of microbes. Cancers (Basel) 15:443. doi: 10.3390/cancers15020443

An, J., Kwon, H., and Kim, Y. J. (2023). The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio as a risk factor of breast Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 12:62216. doi: 10.3390/jcm12062216

Arnold, M., Morgan, E., Rumgay, H., Mafra, A., Singh, D., Laversanne, M., et al. (2022). Current and future burden of breast cancer: global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast 66, 15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2022.08.010

Arnone, A. A., and Cook, K. L. (2022). Gut and breast microbiota as endocrine regulators of hormone receptor-positive breast Cancer risk and therapy response. Endocrinology 164:bqac177. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqac177

Azamjah, N., Soltan-Zadeh, Y., and Zayeri, F. (2019). Global trend of breast cancer mortality rate: a 25-year study. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prevent. 20, 2015–2020. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.7.2015

Bodai, B. I., and Nakata, T. E. (2020). Breast Cancer: lifestyle, the human gut microbiota/microbiome, and survivorship. Perm. J. 24:24. doi: 10.7812/TPP/19.129

Caleca, T., Ribeiro, P., Vitorino, M., Menezes, M., Sampaio-Alves, M., Mendes, A. D., et al. (2023). Breast Cancer survivors and healthy women: could gut microbiota make a difference?-"BiotaCancerSurvivors": a case-control study. Cancers (Basel) 15:594. doi: 10.3390/cancers15030594

Chen, C., Shen, J., Du, Y., Shi, X., Niu, Y., Jin, G., et al. (2022). Characteristics of gut microbiota in patients with gastric cancer by surgery, chemotherapy and lymph node metastasis. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 24, 2181–2190. doi: 10.1007/s12094-022-02875-y

ElSherif, A., Cocco, D., Bernard, S., Djohan, R., Tu, C., and Valente, S. A. (2023). Simultaneous contralateral prophylactic mastectomy compared to unilateral nipple-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer surgical treatment: are complications higher? Am. J. Surg. 225, 527–531. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2022.12.007

Feng, Z. P., Xin, H. Y., Zhang, Z. W., Liu, C. G., Yang, Z., You, H., et al. (2021). Gut microbiota homeostasis restoration may become a novel therapy for breast cancer. Investig. New Drugs 39, 871–878. doi: 10.1007/s10637-021-01063-z

Ghoncheh, M., Mahdavifar, N., Darvishi, E., and Salehiniya, H. (2016). Epidemiology, incidence and mortality of breast cancer in Asia. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 17, 47–52. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2016.17.S3.47

Hajjar, R., Gonzalez, E., Fragoso, G., Oliero, M., Alaoui, A. A., Calve, A., et al. (2023). Gut microbiota influence anastomotic healing in colorectal cancer surgery through modulation of mucosal proinflammatory cytokines. Gut 72, 1143–1154. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2022-328389

Huo, R. X., Wang, Y. J., Hou, S. B., Wang, W., Zhang, C. Z., and Wan, X. H. (2022). Gut mucosal microbiota profiles linked to colorectal cancer recurrence. World J. Gastroenterol. 28, 1946–1964. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i18.1946

James, M. M., Pal, N., Sharma, P., Kumawat, M., Shubham, S., Verma, V., et al. (2022). Role of butyrogenic Firmicutes in type-2 diabetes. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 21, 1873–1882. doi: 10.1007/s40200-022-01081-5

Jorgensen, M. G., Gozeri, E., Petersen, T. G., and Sorensen, J. A. (2023). Surgical-site infection is associated with increased risk of breast Cancer-related lymphedema: a Nationwide cohort study. Clin. Breast Cancer 23, e296, e304e2–e304.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2023.03.016

Kiecka, A., Macura, B., and Szczepanik, M. (2023). Modulation of allergic contact dermatitis via gut microbiota modified by diet, vitamins, probiotics, prebiotics, and antibiotics. Pharmacol. Rep. 75, 236–248. doi: 10.1007/s43440-023-00454-8

Li, Z., Zhou, E., Liu, C., Wicks, H., Yildiz, S., Razack, F., et al. (2023). Dietary butyrate ameliorates metabolic health associated with selective proliferation of gut Lachnospiraceae bacterium 28-4. JCI Insight 8:166655. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.166655

Lin, X., Wang, M., He, Z., and Hao, G. (2023). Gut microbiota mediated the therapeutic efficiency of Simiao decoction in the treatment of gout arthritis mice. BMC Complement Med Ther. 23:206. doi: 10.1186/s12906-023-04042-4

Liu, N., Zou, S., Xie, C., Meng, Y., and Xu, X. (2023). Effect of the beta-glucan from Lentinus edodes on colitis-associated colorectal cancer and gut microbiota. Carbohydr. Polym. 316:121069. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.121069

Marino, M. M., Nastri, B. M., D'Agostino, M., Risolo, R., De Angelis, A., Settembre, G., et al. (2022). Does gut-breast microbiota Axis orchestrates Cancer progression? Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 22, 1111–1122. doi: 10.2174/1871530322666220331145816

Memili, A., Lulla, A., Liu, H., Shikany, J. M., Jacobs, D. R. Jr., Langsetmo, L., et al. (2023). Physical activity and diet associations with the gut microbiota in the coronary artery risk development in Young adults (CARDIA) study. J. Nutr. 153, 552–561. doi: 10.1016/j.tjnut.2022.12.019

Mu, J., Chen, Q., Zhu, L., Wu, Y., Liu, S., Zhao, Y., et al. (2019). Influence of gut microbiota and intestinal barrier on enterogenic infection after liver transplantation. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 35, 241–248. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2018.1470085

Penckofer, S., Limeira, R., Joyce, C., Grzesiak, M., Thomas-White, K., and Wolfe, A. J. (2020). Characteristics of the microbiota in the urine of women with type 2 diabetes. J. Diabetes Complicat. 34:107561. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2020.107561

Peters, B. A., Hayes, R. B., Goparaju, C., Reid, C., Pass, H. I., and Ahn, J. (2019). The microbiome in lung Cancer tissue and recurrence-free survival. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 28, 731–740. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0966

Punchai, S., Hanipah, Z. N., Meister, K. M., Schauer, P. R., Brethauer, S. A., and Aminian, A. (2017). Neurologic manifestations of vitamin B deficiency after bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 27, 2079–2082. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2607-8

Rizzatti, G., Lopetuso, L. R., Gibiino, G., Binda, C., and Gasbarrini, A. (2017). Proteobacteria: a common factor in human diseases. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017:9351507. doi: 10.1155/2017/9351507

Santos-Marques, C., Ferreira, H., and Goncalves, P. S. (2022). Infection prevention and control strategies against carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae – a systematic review. J. Infect. Prev. 23, 167–185. doi: 10.1177/17571774211066762

Sasaki, K., Inoue, J., Sasaki, D., Hoshi, N., Shirai, T., Fukuda, I., et al. (2019). Construction of a model culture system of human colonic microbiota to detect decreased Lachnospiraceae abundance and Butyrogenesis in the feces of ulcerative colitis patients. Biotechnol. J. 14:e1800555. doi: 10.1002/biot.201800555

Sharman, R., Sullivan, K., Young, R. M., and McGill, J. (2012). Depressive symptoms in adolescents with early and continuously treated phenylketonuria: associations with phenylalanine and tyrosine levels. Gene 504, 288–291. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.05.007

Sun, Y., Zhang, S., Nie, Q., He, H., Tan, H., Geng, F., et al. (2022). Gut firmicutes: relationship with dietary fiber and role in host homeostasis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 63, 12073–12088. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2022.2098249

Suppli, M. P., Bagger, J. I., Lelouvier, B., Broha, A., Demant, M., Konig, M. J., et al. (2021). Hepatic microbiome in healthy lean and obese humans. JHEP Rep. 3:100299. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2021.100299

Tong, J., Zhang, X., Fan, Y., Chen, L., Ma, X., Yu, H., et al. (2020). Changes of intestinal microbiota in ovarian cancer patients treated with surgery and chemotherapy. Cancer Manag. Res. 12, 8125–8135. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S265205

Toumazi, D., El Daccache, S., and Constantinou, C. (2021). An unexpected link: the role of mammary and gut microbiota on breast cancer development and management (review). Oncol. Rep. 45:8031. doi: 10.3892/or.2021.8031

Toya, T., Corban, M. T., Marrietta, E., Horwath, I. E., Lerman, L. O., Murray, J. A., et al. (2020). Coronary artery disease is associated with an altered gut microbiome composition. PLoS One 15:e0227147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227147, Whole-Vine Products (Santa Rosa, CA) and Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN) to AL. This does not alter our adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials

Wang, W., Du, Y., Yang, S., Du, X., Li, M., Lin, B., et al. (2019). Bacterial extracellular Electron transfer occurs in mammalian gut. Anal. Chem. 91, 12138–12141. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b03176

Wolfe, A. E., and Markey, K. A. (2022). The contribution of the intestinal microbiome to immune recovery after HCT. Front. Immunol. 13:988121. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.988121

Wu, X., Zhang, W., Zhao, X., Zhang, L., Xu, M., Hao, Y., et al. (2023). Investigating the relationship between depression and breast cancer: observational and genetic analyses. BMC Med. 21:170. doi: 10.1186/s12916-023-02876-w

Xu, H., Liu, L., Xu, F., Liu, M., Song, Y., Chen, J., et al. (2022). Microbiome-metabolome analysis reveals cervical lesion alterations. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. Shanghai 54, 1552–1560. doi: 10.3724/abbs.2022149

Yang, Q., Wang, B., Zheng, Q., Li, H., Meng, X., Zhou, F., et al. (2023). A review of gut microbiota-derived metabolites in tumor progression and Cancer therapy. Adv Sci (Weinh). 10:e2207366. doi: 10.1002/advs.202207366

Yap, Y.-S., Lu, Y.-S., Tamura, K., Lee, J. E., Ko, E. Y., Park, Y. H., et al. (2019). Insights into breast cancer in the east vs the west: a review. JAMA Oncol. 5, 1489–1496. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0620

Keywords: breast cancer, surgery, gut microbiota, metabolites, 16s rRNA

Citation: Fan P, Ding L, Du G and Wei C (2024) Effect of mastectomy on gut microbiota and its metabolites in patients with breast cancer. Front. Microbiol. 15:1269558. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1269558

Edited by:

Eva Maria Weissinger, Hannover Medical School, GermanyReviewed by:

Iram Maqsood, University of Maryland, United StatesSara Federici, Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel

Copyright © 2024 Fan, Ding, Du and Wei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guankui Du, ZHVndWFua3VpQDE2My5jb20=; Changyuan Wei, Y2hhbmd5dWFud2VpQGd4bXUuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Pingming Fan

Pingming Fan Linwei Ding

Linwei Ding Guankui Du

Guankui Du Changyuan Wei

Changyuan Wei