95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Microbiol. , 10 January 2024

Sec. Infectious Agents and Disease

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1330029

Mengkai Liu1†

Mengkai Liu1† Hui Gao1†

Hui Gao1† Jinlai Miao2

Jinlai Miao2 Ziyan Zhang1

Ziyan Zhang1 Lili Zheng3

Lili Zheng3 Fei Li1

Fei Li1 Sen Zhou1

Sen Zhou1 Zhiran Zhang1

Zhiran Zhang1 Shengxin Li1

Shengxin Li1 He Liu1

He Liu1 Jie Sun1*

Jie Sun1*The global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection remains high, indicating a persistent presence of this pathogenic bacterium capable of infecting humans. This review summarizes the population demographics, transmission routes, as well as conventional and novel therapeutic approaches for H. pylori infection. The prevalence of H. pylori infection exceeds 30% in numerous countries worldwide and can be transmitted through interpersonal and zoonotic routes. Cytotoxin-related gene A (CagA) and vacuolar cytotoxin A (VacA) are the main virulence factors of H. pylori, contributing to its steep global infection rate. Preventative measures should be taken from people’s living habits and dietary factors to reduce H. pylori infection. Phytotherapy, probiotics therapies and some emerging therapies have emerged as alternative treatments for H. pylori infection, addressing the issue of elevated antibiotic resistance rates. Plant extracts primarily target urease activity and adhesion activity to treat H. pylori, while probiotics prevent H. pylori infection through both immune and non-immune pathways. In the future, the primary research focus will be on combining multiple treatment methods to effectively eradicate H. pylori infection.

Helicobacter pylori is a micro anaerobic, Gram-negative, spiral shape bacterium, which requires rigorous growth conditions (Flores-Treviño et al., 2018; Hirukawa et al., 2018). In 1983, H. pylori was first time successfully isolated from gastric mucosa biopsies of patients who had chronic antral gastritis (Isaacson and Wright, 1983). It is closely related to gastrointestinal diseases such as gastritis, gastric ulcer, and gastric cancer (Sharndama and Mba, 2022). In 2017, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer published a preliminary list of carcinogens, and H. pylori (infection) was classified as a Class I carcinogen.

The global H. pylori infection rate is extremely steep. The infection rate of H. pylori in developing countries is 85%–95%, which is significantly higher than that in developed countries (30%–50%). Similarly, the H. pylori infection rates in economically underdeveloped areas are higher than those in financially developed areas. This discrepancy may be attributed to various factors such as health conditions, socioeconomic status, race, and population density (Khoder et al., 2019). Chronic smoking, inadequate vitamin supplementation, excessive daily salt intake, and host factors can all alter the acidic environment in the stomach and increase susceptibility to H. pylori infection among this group of people (Kayali et al., 2018).

The traditional treatment for H. pylori infection is proton pump inhibitors (PPI) combined with two antibiotics and bismuth (Savoldi et al., 2018). However, the rate of antibiotic resistance has increased in recent years, which led to a decline in H. pylori eradication rates. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), antibiotic resistance rates such as clarithromycin and metronidazole have reached unacceptable levels (more than 15%; Savoldi et al., 2018). The rate of resistance to clarithromycin was 15.6% in the early 2000s, but increased to 40.0% by the 2020s. The resistance rate of metronidazole also showed an increasing trend, from 57.8% in the early 21st century to 77.5% in the 2020s (Garvey et al., 2023). However, the eradication rate of H. pylori with traditional triple therapy is already below 80% (Savoldi et al., 2018). The Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report states that triple therapy containing antibiotics should be abandoned when antibiotic resistance rates are higher than 15%. Therefore, quadruple therapy containing bismuth salts (two antibiotics, PPI, bismuth salts) can be used for first-line treatment (Alkim et al., 2017). But quadruple therapy still contains antibiotics and is not suitable for antibiotic-resistant people. Bismuth salts are also limited, so quadruple therapy containing bismuth is still not available as first-line therapy in countries where bismuth use is restricted (Goderska et al., 2018). Additionally, antibiotics may induce adverse effects on the human gastrointestinal tract, such as diarrhea, anorexia, emesis, abdominal distension and pain (Poonyam et al., 2019). Antimicrobial therapy is not recommended for the elderly, children, pregnant women and lactating women for safety reasons. As a result, there is a growing demand for alternative treatments that can effectively manage H. pylori infection. Compared with antibiotic therapy, phytotherapy and probiotics therapies produce fewer resistant strains and can reduce the side effects of antibiotics. In addition, phytotherapy and probiotics therapies are useful dietary treatments. Mozaffarian et al. point out that food is medicine (Mozaffarian et al., 2022). Foods related to plant extracts and probiotics are on the rise. These novel approaches are effective in treating H. pylori infection.

This paper provides a comprehensive review of the global prevalence, transmission routes, pathogenesis of H. pylori infection, as well as an overview of phytotherapy and probiotics therapies and emerging therapies, including their possible mechanisms against H. pylori. And aims to enhance the understanding of the transmission pathways and impact on human health caused by H. pylori infection, as well as to provide novel insights into treatment approaches and strategies for managing this pathogen.

Helicobacter pylori infection exhibits high prevalence rates in many countries, affecting nearly one-third of adults worldwide (Bruno et al., 2018). There are some geographical differences in H. pylori infection. Several report data related to the incidence of H. pylori worldwide show that the infection rate of H. pylori varies greatly among continents due to their economic development, health conditions, education level and eating habits, and the results are shown in Figure 1 (Rehnberg-Laiho et al., 2001; Bakka and Salih, 2002; Bener et al., 2006; Romero et al., 2007; Mansour et al., 2010; Adlekha et al., 2013; Alvarado-Esquivel, 2013; Bastos et al., 2013; Benajah et al., 2013; Hanafi and Mohamed, 2013; Krashias et al., 2013; Lim et al., 2013; Mana et al., 2013; Olokoba et al., 2013; Ozaydin et al., 2013; Pacheco et al., 2013; Sethi et al., 2013; Sodhi et al., 2013; Vilaichone et al., 2013; Eshraghian, 2014; Hooi et al., 2017; Zamani et al., 2018; Mezmale et al., 2020; Varga et al., 2020; Mežmale et al., 2021; Mentzer et al., 2022; Ren et al., 2022). According to available data, H. pylori prevalence is highest in Africa, followed by Asia and Europe, and lowest in the Americas and Oceania. In Africa, the infection rate of H. pylori is even as high as 90% in Libya, Egypt, Nigeria and other countries (Sathianarayanan et al., 2022). In China, a systematic analysis of H. pylori infection rate from 1990 to 2019 showed that the prevalence of H. pylori was close to 45%, and it was estimated that nearly 600 million people in China were infected with H. pylori (Ren et al., 2022). The prevalence rates of H. pylori in the northwest and east of China were the highest, accounting for 51.8 and 47.7%, respectively (Ren et al., 2022). In the United States, there are variations in H. pylori infection rates among different races and ethnicities. Notably, Hispanics exhibit the highest prevalence of H. pylori infection at 60.2% within the country. More than half of blacks are infected, while the prevalence rate of whites is only 21.9% (Peng et al., 2019). This phenomenon can potentially be attributed to factors such as local dietary patterns, living environments, and economic development.

The prevalence of H. pylori in various countries is decreasing over time as people’s living standards and eating habits have improved (Hooi et al., 2017). The prevalence of H. pylori in China dropped obviously from 58.3% in 1983–1994 to 40.0% in 2015–2019 (Ren et al., 2022). In Japan, the prevalence of older people born before the 1950s was more than 80%, and by 1990 the prevalence had decreased to less than 10%. Children born after the 21st century have an even lower prevalence (less than 2%; Inoue, 2017).

Numerous studies have shown that H. pylori infection is greatly related to age. H. pylori infection rates are very high in people over 60 (95%), whereas the infection rates is low in adolescents (35%; Shi et al., 2018). In Armenia, the prevalence of H. pylori varies with age: 18–25 years old: 13.6%; 26–45 years old: 37.9%; 46–65 years old: 61.4%; over 65 years old: 83.3% (Gemilyan et al., 2019). Therefore, we need to strengthen the research on H. pylori infection to totally eradicate H. pylori infection and prevent H. pylori recurrence.

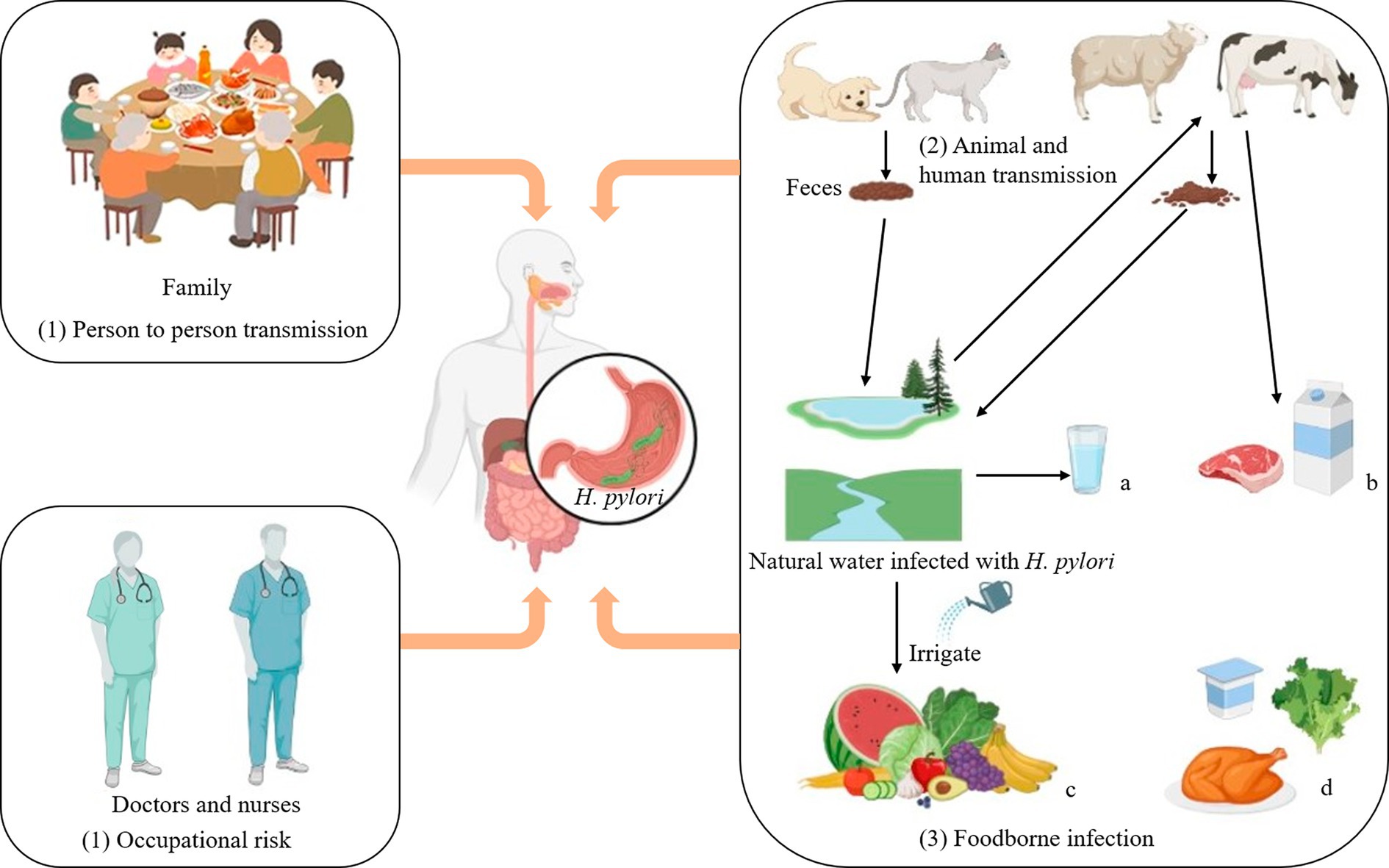

To enhance the protection of humans against H. pylori infection, it is imperative to comprehend its routes of transmission more comprehensively. H. pylori infects humans through three routes:

The transmission of H. pylori can occur through person-to-person routes, especially within families where maternal-child transmission is prevalent (Yang et al., 2023). Studies have shown that H. pylori infection can occur in clusters in families. According to clinical investigations, if parents are infected with H. pylori, their children will also be infected (Ding et al., 2022). In the medical industry, the infection rate of Helicobacter pylori among digestive tract endoscopists is 82.4%. The infection rate of digestive tract nurses is 16.8%, while that of dentists is as high as 70% (Kheyre et al., 2018). In summary, occupational factors are also an essential pathway for possible infection with H. pylori.

Animal-to-human transmission is thought to be an important route by which H. pylori infects humans. H. pylori is a pathogen that can infect both humans and animals (Duan et al., 2023). In the Tatra Mountains of Poland, the prevalence of H. pylori was particularly high among shepherds and their family members (97.6% and 86%, respectively), compared with 65.1% among farmers who were not exposed to sheep (Papież et al., 2003; Soloski et al., 2022). In addition, H. pylori has been detected in milk, meat (mutton, beef) and other fresh foods, suggesting that milk and sheep milk may be a vector for H. pylori infection in humans (Hemmatinezhad et al., 2016; Shaaban et al., 2023). A study in Japan confirmed by PCR (Polymerase chain reaction) that two dogs were infected with the same strain of H. pylori as their owners (Kubota-Aizawa et al., 2021).

Finally, it has been shown that H. pylori can be contracted through water and food infection. Fecal matter containing H. pylori can contaminate lakes, rivers and groundwater, which are important sources of drinking water, so it is likely that people contracted H. pylori through drinking water (Duan et al., 2023). Elevated levels of H. pylori detected in bottled water in Iran (up to 50%; Ranjbar et al., 2016). More recently, Monno et al. suggested through a meta-analysis that H. pylori infection was associated with dependence on external municipal water (Monno et al., 2019). There may be a risk of H. pylori infection from drinking externally contaminated water sources. Therefore, strengthening water source testing and enhancing dietary supervision can effectively interrupt the transmission of H. pylori.

If water contaminated with H. pylori is used to irrigate farmland, it will pose a significant risk of infecting fruits and vegetables, leading to food-borne infections in humans. Hemmatinezhad et al. detected 50 fruit salads by PCR, and found that H. pylori was detected in 14 samples. This may be related to direct contact with water sources, and thorough washing can mitigate the risk of infection (Hemmatinezhad et al., 2016). The 600 raw meat samples were randomly taken from slaughterhouses in different regions of Iran for detection of H. pylori. The contamination rate of mutton was as steep as 13.07%, and that of goat mutton was 11.53% (Mashak et al., 2020). Shaaban et al. detected H. pylori in 13 milk samples from farm animals infected with H. pylori, and H. pylori in 5 milk samples (Shaaban et al., 2023).

Overall, as shown as depicted in Figure 2, H. pylori infects humans through three primary routes. Human infection with H. pylori can occur via water and food sources, while contact with infected people and animals escalates the risk of transmission. Therefore, it is crucial to prioritize personal hygiene in our daily lives through washing our hands frequently and disinfecting frequently, as these measures can effectively mitigate the risk of H. pylori transmission. Consequently, rigorous water testing is conducted in daily life to eradicate the source of H. pylori infection. It is essential to thoroughly cleanse vegetables and fruits prior to consumption while minimizing the consumption of raw produce and meat products.

Figure 2. Transmission routes of Helicobacter pylori. Transmission routes of Helicobacter pylori. (1) Person to person transmission: It often spreads in families and is most likely to infect the elderly and adolescents. Occupational risk: Close contact between doctors and nurses and patients infected with Helicobacter pylorii may increase the odds of contracting the disease. (2) Animal and human transmission: Homeowners can contract Helicobacter pylori through close contact with their pets. (3) Foodborne infection: a: Fecal matter is a significant cause of contamination in most drinking water sources. b: Cattle and sheep can drink water infected with Helicobacter pylori, and their feces can in turn contaminate lakes and rivers. d: Helicobacter pylori can exist in low-acid, low-temperature, elevated humidity environments, such as chicken, raw vegetables, yogurt, and other ready-to-eat foods. Thus Helicobacter pylori can infect human through food and water.

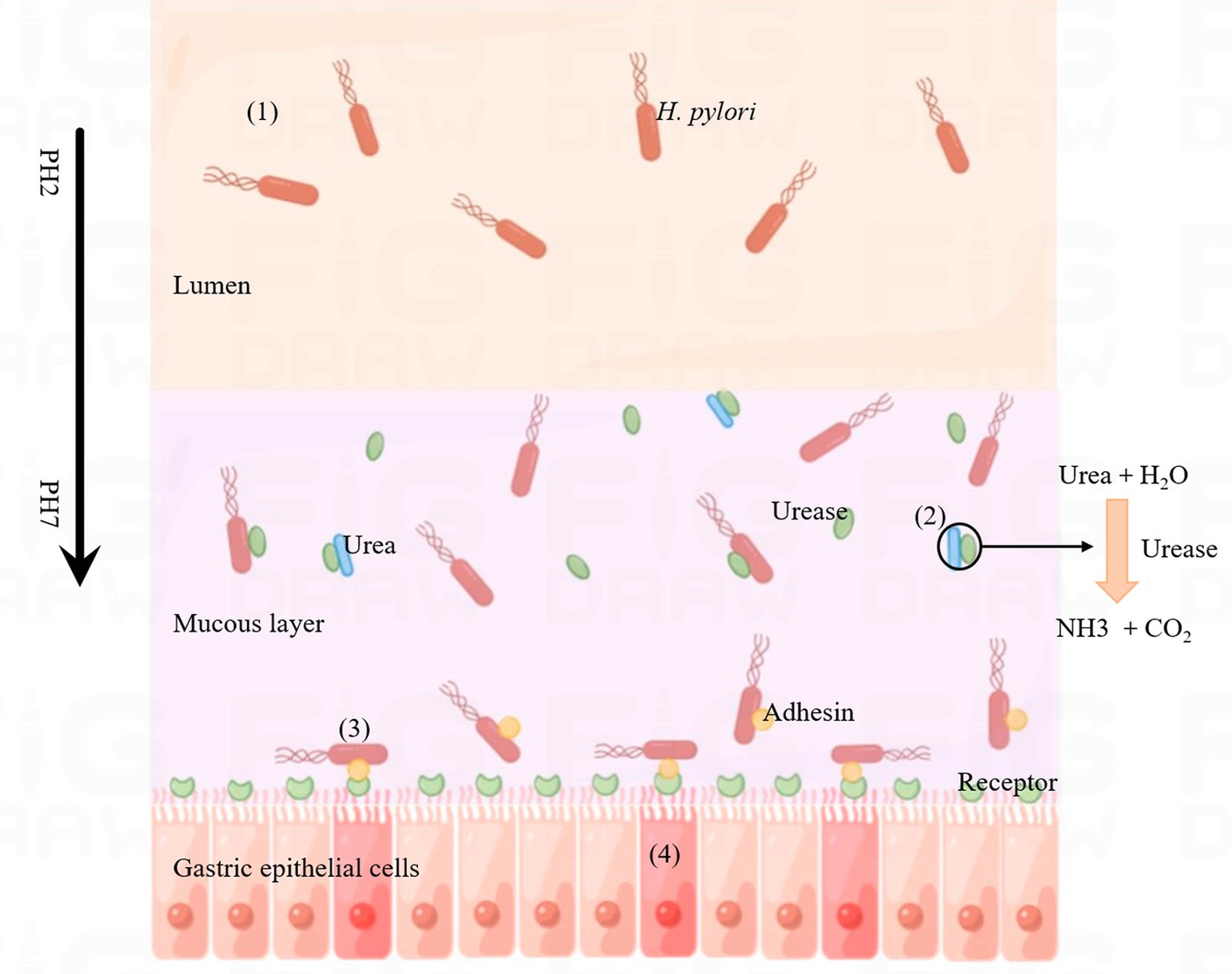

Helicobacter pylori infection can cause a variety of gastrointestinal diseases, which may be related to its distinct infection and colonization mechanisms. The pathogenic process is illustrated in Figure 3. After H. pylori invades the human stomach, it first releases urease to break down urea in the stomach to produce ammonia, which raises the pH of the stomach and provides a suitable environment for H. pylori to grow. The second step is the movement of H. pylori onto human gastric epithelial cells via flagella rotation. In the third step, H. pylori releases bacterial adhesins that can bind to specific receptors in gastric epithelial cells and colonize the host. Finally, H. pylori releases toxins, including CagA and VacA, which ultimately lead to inflammation in the gastric epithelial cells, leading to disease (Kao et al., 2016). The virulence factors CagA and VacA play a key role in the above steps.

Figure 3. Process of Helicobacter pylori infection. (1) Helicobacter pylori enters the lumen of the host stomach. (2) Helicobacter pylori releases urease, decomposes the metabolites of other microorganisms (urea) into ammonia, changes the acidic environment of the stomach, which is conducive to the growth of H. pylori. (3) Helicobacter pylori releases adhesins (such as BabA, SabA, AlpA, HopQ, HopZ and OipA) that bind to specific receptors on gastric epithelial cells. (4) Helicobacter pylori releases CagA and VacA, which invade gastric epithelial cells and cause inflammatory reactions.

CagA is a protein encoded by Cag pathogenic island (Cag PAI) in H. pylori, with a total length of about 120–145 KDa. Cag PAI is a 40 kb locus containing a variety of genes, which can encode a type IV secretory system (T4SS), in which H. pylori contains a variety of adhesion hormones, including BabA (B), SabA, AlpA (B), HopQ, HopZ, and OipA, etc. They can mediate H. pylori to adhere tightly to gastric epithelial cells and promote the formation of T4SS (Takahashi-Kanemitsu et al., 2020). T4SS can deliver CagA to the gastric epithelial cells of the host through receptors for colonization, which cause diseases (Ray et al., 2021). Translocated CagA is localized to the interior of the plasma membrane of gastric epithelial cells, followed by phosphorylation on gastric epithelial cells. If injected into the cytoplasm via T4SS, CagA can alter host cell signaling in both phosphorylation-dependent and phosphorylation-independent ways. Phosphorylated CagA binds to phosphatase SHP-2 and affects cell adhesion, diffusion, and migration (Kao et al., 2016). Almost 60% of H. pylori strains detected in some Western countries and regions are Cag PAI positive (Nejati et al., 2018). The prevalence of non-cardiac gastric adenocarcinoma (AGS) cells is also elevated in Alaska. H. pylori infection is an essential factor in gastric adenocarcinoma. Among indigenous peoples with elevated rates of stomach cancer, Miernyk et al. found that more than half of H. pylori had whole CagPAI (Miernyk et al., 2020).

Nearly all strains of H. pylori contain the VacA gene, which encodes the VacA protein. In mouse models, VacA has been reported to play an influential role in the initial colonization of the host (Chauhan et al., 2019). VacA is a key cytotoxin of H. pylori with the ability to induce cell vacuoles (Ansari and Yamaoka, 2019). After receiving a signal, VacA cleans its N-terminal and C-terminal structure, generating an N-terminal signal sequence (33 residues), a mature 88 kDa secretory toxin (p88), a short secretory peptide structure of unknown function, and a C-terminal auto-transport domain. The mature p88 is divided into two subunits (p33 and p55). p33 plays a key role in cytoplasmic membrane insertion and p55 is needed for toxins to bind to the plasma membranes. The latter part of the VacA gene signal sequence has a variable region, according to which H. pylori can be divided into s1 and s2. This variable region helps to recognize the intima receptor of the target cells. There are m1 and m2 alleles in p55. Typically, H. pylori strain s1 can secrete additional VacA, and thus genotypes with s1 / m1 combination have elevated vacuole formation capacity (Ansari and Yamaoka, 2019). Among different H. pylori strains, the strain with s1/ m1 allele is more closely associated with gastric epithelial injury and gastric ulcer (Ansari and Yamaoka, 2019). A meta-analysis in central Asia found that strains of H. pylori with the s1 / m1 combination made individuals more susceptible to stomach cancer (Liu et al., 2016). VacA antibodies have been associated with an increase in the incidence of ulcers of the digestive system, such as gastric and duodenal ulcers. The antibody has also been linked to stomach cancer (Li et al., 2016).

Helicobacter pylori secretes VacA near the plasma membrane of the target cell. VacA then binds to the plasma membrane to form anion-specific channels with low conductivity (Sharndama and Mba, 2022). These channels release mediators such as anions from the cell’s cytoplasm to support bacterial growth. Secreted toxins are slowly endocytosed, causing damage to the host cell’s organelles (endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria; McClain et al., 2017). VacA can also inhibit the activation of immune cells (T lymphocytes) and affect the normal immune response. In addition, VacA can activate the autophagy pathway and promote apoptosis in gastric gland cells (Ansari and Yamaoka, 2019; Sharndama and Mba, 2022).

Antibiotic therapy was the primary treatment method for H. pylori infection. Antibiotics commonly used to treat H. pylori include amoxicillin, clarithromycin, metronidazole, tetracycline, and others. The common treatment for H. pylori infection was a triple treatment with a PPI that reduces stomach acid production and two antibiotics (Lee et al., 2022). A meta-analysis conducted among residents of a district in Bulgaria showed that H. pylori strains were 42.0% resistant to metronidazole and 30% resistant to clarithromycin (Boyanova et al., 2023). Savoldi et al. conducted a meta-analysis of clarithromycin resistance rates in different regions of the world for H. pylori. The results showed that the resistance rate of clarithromycin in Europe was approximately 18%, and the resistance rates in Mediterranean and western Pacific were over 30% (33% and 34% respectively; Lin et al., 2023). Antibiotic resistance rates are different in developed and developing countries, as shown in Figure 4 (Boyanova et al., 2010; Binh et al., 2013; Kuo et al., 2017; Saniee et al., 2018; Savoldi et al., 2018; Maev et al., 2020; Vilaichone et al., 2020; Akar et al., 2021; Ho et al., 2022; Schubert et al., 2022; Vanden Bulcke et al., 2022). Resistance to clarithromycin and metronidazole appears to be higher than that to other antibiotics both developed and developing countries. Therefore, the use of antibiotics in the treatment of H. pylori infection should be controlled. Resistance of H. pylori to antibiotics is primarily associated with the formation of biofilms (Hou et al., 2022). There is a layer of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) on the surface of microorganisms. Biofilm is a community of microorganisms, EPS, and alternative substrates that mainly contain sugar, protein, nucleic acids, and other substances. EPS, which is negatively charged on the surface, prevents antibiotics and other drugs from getting through the biofilm into the bacteria and makes the bacteria resistant to antibiotics and other drugs. Therefore, some bacteria (forming biofilm) are 1,000 times more resistant to antibiotics than planktonic microorganisms (Shen et al., 2020; Hou et al., 2022). Thus, if antibiotics are used to treat H. pylori while biofilm is being created, antibiotics will be blocked from biofilm. As a result, it is not possible for antibiotics or drugs to enter the target cell for treatment and ultimately leads to treatment failure. In addition, the biofilm blocks immune cells from attacking H. pylori, and thus causes antibiotic resistance (Hou et al., 2022). Furthermore, under the conditions of environmental deterioration and the existence of antibiotics, H. pylori will enter a state of viable but non-culturable (VBNC) to resist environmental changes and the invasion of antibiotics (Li et al., 2021). Both the biofilm and VBNC status of H. pylori can lead to its own resistance to antibiotic. Due to the development of drug resistance, H. pylori is not treated promptly, so the infection can produce a range of complications such as bleeding in the stomach, obstruction of the outlet of the digestive system, and perforation of the stomach. In addition, taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can easily cause peptic ulcers, which can cause patients to suffer from stomach pain, loss of appetite, vomiting and abdominal swelling (Lanas and Chan, 2017). Previous studies have shown that H. pylori infection can cause indigestion in humans. After treatment in these patients successfully removed H. pylori from the body, there was a significant improvement in adverse digestive system reactions (Moayyedi et al., 2017). In addition, approximately four out of five stomach cancers caused by H. pylori are non-cardiac stomach cancers (Guevara and Cogdill, 2020). In previous studies, H. pylori positive patients were less likely to develop stomach cancer after eradication therapy (compared to placebo; Gawron et al., 2020). So finding a way to treat H. pylori without developing resistance could reduce the incidence of stomach cancer.

The drug resistance rate is higher when clarithromycin and metronidazole are used to treat H. pylori, so bismuth quadruple therapy is recommended as first-line treatment. When triple therapy fails, levofloxacin-based therapies, as well as therapies containing macrolides, may be used as an alternative treatment (Guevara and Cogdill, 2020). Bismuth quadruple therapy was used to solve the problem of antibiotic resistance, which consists of two antibiotics (tetracycline and metronidazole), bismuth and proton pump inhibitor (Harb et al., 2015). However, the quadruple therapy has some limitations. Bismuth salts are restricted in some countries because of their toxicity, and tetracycline has side effects. These reasons limit the large-scale use of quadruple therapy (Goderska et al., 2018). These antibiotics also have side effects. Examples include amoxicillin, clindamycin and tetracycline, which can cause diarrhea. Taking multiple antibiotics can also affect the normal flora in the stomach of the host, resulting in physical discomforts such as nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and rash (Salehi et al., 2018). Therefore, there is an urgent need to find non-antibiotic treatments for H. pylori infection.

Phytotherapy, also known as herbal therapy, is a method that applies the plant itself or plant extracts to medicine. Herbs can be used to treat various gastrointestinal diseases, reduce antibiotic resistance and side effects, and improve the cure rate for H. pylori (Li et al., 2023). Herbal products include raw or processed parts of plants, such as leaves, stems, flowers, roots and seeds. At present, numerous plant extracts have been reported to have therapeutic effects on H. pylori infection, such as Acacia nilotica, Calophyllum brasiliesnse, Bridelia micrantha, Allium sativum, Pistacia lentiscus, Brassica oleracea, Glycyrrhiza glabra, Camellia sinensis, Cinnamomum cassia, Evodia rutaecarpa, Impatiens balsamina and so on (Safavi et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2018; Sathianarayanan et al., 2022).

Helicobacter pylori infection can be treated by consuming certain plant products or certain fruits. These plants contain flavonoids, terpenoids, coumarins, essential oil, tannins and alkaloids, contributing to treat H. pylori infection (Abd El-Moaty et al., 2021; Guerra-Valle et al., 2022). Fahmy et al. found that flavonoids extracted from Erythrina speciosa (Fabaceae) showed strong inhibitory activity against H. pylori, with the lowest inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 31.25 μg/mL (Fahmy et al., 2020). Spósitoe et al. analyzed the components of the leaves of Casearia sylvestris Swartz and showed that the leaves contain a significant amount of terpenoids, which may be the key to its inhibition of H. pylori. Zardast et al. gave patients infected with H. pylori fresh garlic, and the levels of H. pylori in the gastric mucosa of the patients decreased significantly after 3 days (Zardast et al., 2016). The ethyl acetate part of the leaves of this plant has the best antibacterial activity, and the MIC is 62.5 μg/mL (Spósito et al., 2019). Ayoub et al. obtained the essential oil from the stem of Pimenta racemosa, which also had an excellent bactericidal activity against H. pylori, with a MIC of 3.9 μg/mL (Ayoub et al., 2022). In a mouse model, when green tea extract was administered to mice infected with H. pylori at a concentration of 2,000 ppm for 6 weeks, the prevalence was suppressed to the greatest extent. These plant extracts inhibit H. pylori infection mainly through a permeable membrane, anti-adhesion, urease inhibition and other ways (Shmuely et al., 2016). When MIC≤100 μg/mL, plant extracts were considered to have excellent antibacterial activity (Fahmy et al., 2020). As a result, plant foods can be used to treat H. pylori infection in people. They have shown great potential in eradicating H. pylori and preventing related gastric diseases caused by H. pylori.

Zojaji et al. added 500 mg vitamin C daily to 150 patients infected with H. pylori on the basis of antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin and metronidazole, bismuth and omeprazole). Finally, 79 patients in the vitamin C supplementation group were negative for rapid urease test (RUT), and the eradication rate of H. pylori was 78%. The eradication rate from antibiotic therapy alone was only 56.4 percent (Öztekin et al., 2021). In addition, Ibrahim et al. showed that the effect of Pelargonium graveolens oil combined with clarithromycin was better, and the fractional inhibitory concentration index was 0.38 mg/mL (the MIC of the essential oil was 15.63 mg/mL; Ibrahim et al., 2021). The above study shows that plants or fruits can be combined with antibiotics to enhance the therapeutic effect. As a result, the combination of plant extracts and antibiotics is beneficial to eradicate H. pylori. Therefore, plants may be one of the main forces in treating H. pylori infection in the future.

The antibacterial mechanisms of phytotherapy include inhibition of urease activity, anti-adhesion activity, DNA damage, inhibition of protein synthesis and oxidative stress, which are discussed in Table 1.

After H. pylori infects the host, it can neutralize the acidic stomach environment through the action of urease to provide a suitable environment for its growth (Woo et al., 2021). Urease can hydrolyze urea to ammonia and bicarbonate, creating an environment suitable for the growth of H. pylori (Korona-Glowniak et al., 2020). Therefore, H. pylori infection can be treated by inhibiting urease activity. When the concentration of zerumbone (from Zingiber zerumbet Smith) was 20 μM, the urease activity decreased to 73% of the control group (without zerumbone treatment), and the higher the concentration of the plant, the higher inhibited the urease activity (Woo et al., 2021). Compared with the known urease inhibitors (50% inhibition concentration is 4.56 0.41 μg/mL), the IC50 value of Zanthoxylum nitidum on urease activity of H. pylori is 1.29 0.10 mg/mL, and additional research shows that the plant can reduce the urease level by interacting with sulfhydryl groups on urease (Lu et al., 2020). Zhou et al. found that the MIC of Palmatine (from Coptis chinensis) was 75–100 μg/mL when the pH was close to five through agar dilution experiment (Zhou et al., 2017). The literature has not reported any instances of H. pylori’s resistance to plants thus far (Sathianarayanan et al., 2022). Therefore, plant extracts as excellent antibacterial agents can be used to treat H. pylori infection.

After H. pylori infects the host, it first releases urease to neutralize the acidic conditions of the stomach, and then colonizes the stomach by releasing adhesin to bind to specific receptors in the stomach. Therefore, H. pylori infection can be treated by inhibiting H. pylori adhesion (Kao et al., 2016). The low molecular sulfate polysaccharides of C. lentillifera (CLCP-1) exhibit (at a concentration of 1,000 μg/mL) reduced H. pylori adherence to AGS cells by approximately 50% compared to controls not treated with the extract, with a significant reduction in cell infection rates (Le et al., 2022). Plant polysaccharides from natural products have been reported to inhibit the adhesion of H. pylori to gastric epithelial cells, thus preventing the formation of biofilms. Such herbs can effectively inhibit the adhesion of H. pylori and improve the effective treatment rate of the drug (Moghadam et al., 2021). Gottesmann et al. extracted a highly esterified saccharide from Abelmoschus esculentus, which could hinder the adhesion of H. pylori to AGS cells. The results showed that IC50 was 550 μg/mL (Gottesmann et al., 2020). According to the report, Capsicum annum, Curcuma longa, and Abelmoschus esculentus significantly impede the adhesion of H. pylori to AGS cells, with suppression rates exceeding 10% for all three (Yakoob et al., 2017). Wheat germ extract has been shown to treat H. pylori infection through its antigens. H. pylori can release adhesins (BabA, SabA, etc.) and bind to the target cell receptor, so as to colonize the host cell. However, the structure of this extract is similar to that of the receptor, and it competes to bind to the adhesin, which results in the failure of the adhesion factor to bind to the host cell, thus reducing H. pylori infection (Sun et al., 2020). Dang et al. extracted 14 therapeutic peptides from wheat germ with binding levels of −6.0 to −7.4 and −6.0 to −7.8 kcal/mol to adhesion factors released by H. pylori, respectively. These negative values indicate that the peptide is tightly bound to the adhesion factor (Dang et al., 2022). The above study provides a new direction for the anti-adhesion mechanism of plant-derived peptides, demonstrating that plant-derived peptides are an effective alternative for the treatment of H. pylori. A previous study found that oral cranberry therapy in mice already infected with H. pylori reduced the infection rate to 20 percent after 30 days of treatment (Xiao and Shi, 2003). Black currant (Ribes nigrum L.) can inhibit the adhesion of H. pylori through arabinogalactan, which can block the binding of adhesin to gastric epithelial cell receptors, thus affecting the invasion of H. pylori into the body (Lengsfeld et al., 2004; Messing et al., 2014). Figure 5 shows the possible mechanisms of action for cranberry and black currant. In host cells, plant extracts can inhibit H. pylori adhesion to host cells and affect the formation of the T4SS system.

Recent studies have demonstrated that H. pylori can cause inflammation in gastric epithelial cells and ultimately induce ROS, resulting in DNA damage, which is also an influential factor in gastric cancer (Jain et al., 2021). Some plant extracts can inhibit H. pylori through oxidative stress. Studies have showed that 2-methoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (MeONQ) isolated from the pods of I. balsamina L. had extremely strong inhibitory activity against the growth of H. pylori. The bacteriostatic concentration of MeONQ (0.156–0.625 μg/mL) was considerably lower than metronidazole (MIC was 160–5,120 μg/mL). When MeONQ passes through the cell membrane, it is immediately metabolized by the flavoenzymes in the cell and undergoes a series of redox reactions to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) with strong oxidation. These ROS can additionally damage intracellular macromolecules and may indirectly lead to the death of H. pylori, which may be the bacteriostatic mechanism of MeONQ (Wang et al., 2011). Olive leaf extract E2 reduced ROS production by up to 33.9%, while also reducing H. pylori activity by about 2 log CFU/mL (Silvan et al., 2021). H. pylori infection induces an immune response and increases the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-8 and ROS. When gastric epithelial cells containing H. pylori were treated with resveratrol, the synthesis of IL-8 and ROS was inhibited (Wang et al., 2020). Ayse et al. extracted a phenolic compound from celery and added it to AGS cells infected with H. pylori for co-culture. It was found that the compound suppressed the increase in ROS levels in a dose-dependent manner (Günes-Bayir et al., 2017). Plants can suppress the oxidative stress produced by H. pylori, which can reduce the damage caused to the human body by H. pylori.

Studies have found that drugs with both hydrophilic and hydrophobic properties can inhibit the growth of H. pylori, and quinolone alkaloids are thought to have this advantage. The quinolone alkaloid is an amphiphilic monocyclic monoterpenoid derived from Evodia rutaecarpa. The MIC against H. pylori is less than 0.05 μg/mL, which has the same inhibitory effect as commonly used antibiotics. This derivative is strongly hydrophilic and hydrophobic. Due to its hydrophilicity, the compound diffuses to the cell wall of H. pylori through the surrounding water, while the hydrophobicity makes the compound partially bound to the plasma membrane of the cell, resulting in the loss of membrane integrity and thus affecting the growth of H. pylori (Hamasaki et al., 2000).

Harmati et al. constructed a mouse model infected with H. pylori SS1 and treated the mice with extracts from two plants (Satureja Hortensis and Origanum Vulgaris subsp). Through PCR analysis and Giemsa staining observations, it was found that only 30% of the mice were still infected with H. pylori and the rest tested negative for H. pylori (Harmati et al., 2017). Plant extracts are a valuable resource for the treatment of H. pylori. Some plant extracts can be made into health foods that have been shown to have a beneficial effect on the treatment of gastrointestinal discomfort. Compared with antibiotics and PPI treatment, most of the effective ingredients in plant therapy come from plants, fruits and spices (Liu et al., 2018), which may be relatively economical in areas with poor sanitary conditions and have strong bactericidal activity and anti-inflammatory activity. Whether it is treated alone or combined with antibiotics, the effect is safe and reliable (Shmuely et al., 2016). Various studies have demonstrated the efficacy of plant extracts in the treatment of H. pylori, thus indicating the potential incorporation of certain botanical products into conventional therapies for H. pylori infection.

In microbial therapy, probiotics are commonly used to treat H. pylori infection. Probiotics are a kind of active microorganisms that are beneficial to the host by colonizing the human body and changing the composition of the flora in a certain part of the host. Probiotics, especially Lactobacillus, can be used to treat H. pylori infection in the stomach because they grow in acidic conditions at pH 4–6. Probiotics have safety, immunomodulatory and antibacterial advantages, so they are frequently administered alone or in combination with drugs to treat certain gastrointestinal disorders (Yang and Yang, 2019a,b). They can regulate host immune function or maintain intestinal health by regulating the balance of intestinal flora. In a randomized controlled trial, a probiotic (Lactobacillus Acidophilus LA-5, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, Bifidobacterium lactis BB-12, and Saccharomyces boulardii) combined with four antibiotics (omeprazole, amoxycillin, clarithromycin, and metronidazole) was used to treat H. pylori infection. The results showed that the control group without probiotics had an 86.8 percent cure rate for H. pylori, while the experimental group with probiotics had a cure rate of 92 percent (Viazis et al., 2022). Aiba et al. treated a model mouse infected with H. pylori with L. johnsonii No. 1088. The study showed that L. johnsonii No. 1088 significantly blocked the growth of H. pylori in the stomachs of mice (Aiba et al., 2017). Therefore, probiotics are another useful alternative treatment for H. pylori infection.

Different probiotics inhibit H. pylori through different pathways, and the probiotics that can treat H. pylori are listed in Table 2. Probiotics not only inhibit the activity of urease, but also inhibit the adhesion of H. pylori to host cells, which is the key to probiotics in treating H. pylori infection (Thuy et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2023). Therefore, probiotics are potentially vital in preventing H. pylori infection. The results suggest that H. pylori infection can be treated through diet. Probiotics have been an important tool to treat H. pylori, and the future development should provide further opportunities for the use of probiotics.

The possible mechanism of probiotics to inhibit H. pylori infection is mainly through the following two ways.

(1) Probiotics can inhibit H. pylori by produce antibacterial substances. Studies have shown that probiotics can produce various antibacterial substances that affect the growth of H. pylori, such as hydrogen peroxide, organic acids and bactericin (Homan and Orel, 2015). The Bulgarian strain was found to produce an antibacterial substance with a strong anti-H. pylori effect activity, inhibiting more than 81% of H. pylori (Boyanova et al., 2017). Treatment with L. reuteri ATCC 23272 and its supernatant reduced H. pylori by 62.5 and 100%, respectively. Probiotics can also inhibit urease activity, but in a neutral environment this inhibition is removed. Thus, it is conjectured that the supernatant contains acids. To confirm this conjecture, Rezaee et al. culture H. pylori in the same environment using lactic acid and find that the level of inhibition of urease is similar to that of supernatant. It thus provides additional evidence that L. reuteri ATCC 23272 produces antibacterial acids (Rezaee et al., 2019). (2) Some probiotics prevent H. pylori from adhering to cells in the host’s gastrointestinal tract (Goderska et al., 2018). Probiotics can prevent H. pylori infection by synthesizing antimicrobial agents. In addition, probiotics can also compete with H. pylori at the junction with the host cell, reducing H. pylori adhesion. Organic acids are antibacterial substances, they can enter the body of H. pylori and reduce the pH, causing the death of the bacteria (Huang et al., 2022). Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 can block the combination of H. pylori with host cells (mainly duodenal cells). The reason may be that the probiotic contains an amidase that regulates the adhesion of H. pylori to host cells (Czerucka and Rampal, 2019). Thus, Saccharomyces boulardii holds great promise for the treatment of H. pylori. L. plantarum ZJ316 was effective in inhibiting the adhesion of H. pylori to AGS cells, reducing adhesion by 70.14% (Wu et al., 2023). When Shen et al. cultured L. acidophilus NCFM and L. plantarum Lp-115 with AGS cells (H. pylori positive), it was found that probiotics hinder the adhesion of H. pylori to host cells (Shen et al., 2023). (3) Urease is one of the indispensable factors of H. pylori colonization in the digestive system, which is composed of Ure subunits (A, B, C). The enzyme can break down urea into ammonia, which neutralizes the gastric environment. L. plantarum ZJ316 blocks the expression of the Ure gene, thereby inhibiting the synthesis of urease (Wu et al., 2023).

Different probiotics have different effects on the immune system. (1) Some probiotics also induce the production of anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-10) and inhibit the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokine (IL-6, IL-1β, INF-γ), which mediates the inflammatory response in vivo (Thuy et al., 2022; Forooghi Nia et al., 2023). Mice infected with H. pylori were fed L. rhamnosus LGG-18 and L. acidophilus Chen-08. The results showed that probiotics could significantly hinder the expression of pro-inflammatory factors related genes (NF—kappa B, TNF signaling pathway related genes; He et al., 2022). Forooghi Nia et al. treated mice positive for H. pylori with Limosilactobacillus reuteri 2892. After 5 weeks, the results showed that the secretion of cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and INF-γ decreased significantly, while the secretion of IL-10 was significantly increased (Forooghi Nia et al., 2023). (2) Probiotics can enhance both the humoral and cellular immune responses in the host by modulating phagocytes and lymphocytes (Baryshnikova et al., 2023).

In addition, the combination of probiotics and herbs not only improves the fermentation effect of live bacteria, but also treats H. pylori infection and considerably improves the gastrointestinal health of humans. Hasna et al. treated H. pylori with fenugreek extract and Bifidobacterium breve alone, and the highest IZD (inhibition zone diameter) was 16.00 ± 0.00 mm and 20.33 ± 0.58 mm, respectively. However, when the two drugs were combined to treat H. pylori, the IZD was 28.67 ± 0.58 mm (Hasna et al., 2023). As a result, the combination began to be taken seriously. However, probiotic therapy requires specific clinical data to verify its cure rate and efficacy, and thus requires further validation.

In order to deliver drugs to H. pylori colonization sites more effectively and improve the eradication rate of H. pylori, it is necessary to develop a drug delivery system to prevent the acid environment in the stomach from damaging the drug (Luo et al., 2018). Nanoparticles, usually less than 100 nm in size, are the most commonly used delivery carriers. Nanoparticles have large specific surface area and can carry additional drugs to reach the target. They are mainly bound to drugs through chemical bond interactions, adsorption, or embedding. As a result, this delivery method can protect the drug from stomach acid and reduce resistance, thus prolonging the time of action of the drug at the target and improving the therapeutic effect of the drug (Sousa et al., 2022).

Chitosan is the most commonly used carrier for nano-delivery systems. It can penetrate pores in the mucous layer to reach the surface of the gastric epithelium and deliver drugs to the infection site of H. pylori for treatment (Sun et al., 2022). Chitosan has excellent biocompatibility and adheres efficiently to the gastric mucosa system, which prolongs the administration time of the drug in the target cells (Sousa et al., 2022). The development of mucoadhesive nanoparticle delivery systems, such as the chitosan-glutamate nanoparticle system based on amoxicillin and clarithromycin, has been intensively investigated. The system encapsulates amoxicillin and clarithromycin in nanoparticles that protect the antibiotics from gastric acid destruction and adhere to the gastric mucus layer to prolong drug retention time. The production process is illustrated in Figure 6. The eradication rate of H. pylori in the system is 97.17%. The drug release time can be extended by up to 5–8 h (Ramteke et al., 2009). DHA is an unsaturated fatty acid that disrupts the structure of the cell membrane of H. pylori and has a strong bactericidal function. Chitosan is an effective carrier of nano-delivery systems that contain antibiotics to resist damage from stomach acid. Khoshnood et al. therefore designed a nanoparticle based on chitosan and alginate’s DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) -AMX (amoxicillin) for the treatment of H. pylori. Nanoparticles supplemented with 2% (v/v) DHA significantly hindered the growth of H. pylori compared to the control group (no nanoparticles added). Moreover, the inclusion rate of antibiotics increased to 76 percent after the addition of this fatty acid (Khoshnood et al., 2023). In vivo, fucus-chitosan/heparin nanoparticle delivery systems significantly increased the ability to inhibit H. pylori compared to conventional antibiotic therapy. The delivery system (containing 6.0 mg/L of berberine) had an inhibition rate approximately 25.9% ± 3.7% higher than that of the control group (Lin et al., 2015). In addition, the delivery system can encapsulate other non-antibiotic substances, such as antimicrobial peptides and phenolic compounds, to reduce the emergence of resistant strains (Zhang et al., 2015). Nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems have a promising future as they can effectively treat H. pylori infection and are commonly used in the food industry to develop foods to treat H. pylori (Sun et al., 2022).

Liposomes are another drug delivery system that has been successfully used. They have many advantages, such as high encapsulation rates, high safety and biocompatibility (Sharaf et al., 2021). When H. pylori forms a biofilm in the mucous membrane of the stomach, it develops antibiotic resistance, allowing bacteria in the mucous membrane to continue to infect (Shen et al., 2020). Berberine, a substance isolated from Coptis chinensis, has the activity of inhibiting H. pylori urease. Previous studies have confirmed that berberine in combination with antibiotics can be used in the treatment of H. pylori. In addition, the alkaloids destroy bacterial biofilms, which reduces microbial resistance. The positively charged berberine derivative (BDs) synthesized by Shen et al. did not easily pass through the negatively charged mucosa, so it was difficult to enter the H. pylori aggregation site. Shen et al. designed a BDs-Rhamnose-lipids (RHL) based nano-drug delivery system that can penetrate the mucous layer to reach bacterial aggregation points. The clustering rate of the BDs-RHL delivery system is roughly three times higher than that of the BDs delivery system. The MIC value of the system containing BDs (decocarb) was 1.56 μg/mL, while that of the BDS-RHL system was 0.78 μg/mL. The effectiveness of drug treatment also improved considerably as more of the drug reached the site of bacterial infection (Shen et al., 2020). Many nanoscale lipid carriers have been developed to deliver drugs in radical H. pylori therapy. Using liposomes to deliver hesperidin and clarithromycin has been shown to treat H. pylori infection with inhibition rates of up to 94% (Sharaf et al., 2021). A lipid carrier based on mannosylerythritol lipid-B can carry amoxicillin through the mucous layer of the stomach of mice (infected with H. pylori), eliminating the inflammation of the mucous layer (Wu et al., 2022). As shown in Table 3, these delivery systems have a suitable size range and can penetrate the viscous layer. They are also much more adhesive, thus increasing the retention time of the drug, which is effective in treating H. pylori infection. These systems, which maximize the release of drugs outside the body, promise to replace conventional therapies. As a result, nano-delivery systems can be used to treat H. pylori infection and have great promise in food, medicine and other fields.

In addition to the mentioned plant and microbial therapies, there are a number of different treatments on the rise.

Lactoferrin can bind to iron ions, inhibiting the survival of microorganisms in the absence of iron. After H. pylori entered human body, lactoferrin content in stomach increased significantly (Imoto et al., 2023). Lu et al. used animal models to investigate whether infection with H. pylori affects the lactoferrin content in the host. The results showed that the expression level of lactoferrin in the stomach infected with H. pylori was 9.3 times that of the uninfected group (Lu et al., 2021). H. pylori contains a T4SS system that delivers virulence factor (CagA) to target cells and causes inflammation in the host. Iron ions have antibacterial effects by affecting the activity of the T4SS system (Lu et al., 2021). Therefore, lactoferrin is an excellent antimicrobial. Bovine lactoferrin (concentration between 25.2–50.0 mg/mL) can completely inhibit the growth of H. pylori in vitro (Imoto et al., 2023). Previous studies have confirmed that lactoferrin alone does not eliminate bacterial colonization when used in the treatment of H. pylori infection (Imoto et al., 2023). For this reason, lactoferrin is commonly used in combination with different drugs to treat H. pylori infection. Bovine lactoferrin has an inhibitory effect on all H. pylori in vivo with a MIC of 5–20 mg/mL. When the protein was combined with antibiotics (levofloxacin) to treat H. pylori infection, the MIC value (0.31–2.5 mg/mL) decreased significantly (Ciccaglione et al., 2019). In vitro, patients infected with H. pylori were treated with antibiotics (esomeprazole, amoxicillin, levofloxacin) and bovine lactoferrin. The eradication rate of H. pylori in the antibiotic group alone was 75%, while that in the antibiotic combined with bovine lactoferrin group was 92.8% (Ciccaglione et al., 2019). Hablass et al. designed antibiotic therapy (clarithromycin + amoxicillin/metronidazole +PPI) in combination with bovine lactoferrin to treat H. pylori positive volunteers. The combined treatment group had a successful eradication rate of 85.6%, compared with 70.3% for the lactoferrin-free group, suggesting that lactoferrin may improve the efficacy of antibiotic therapy (Hablass et al., 2021). In summary, the use of lactoferrin in the treatment of H. pylori infection has been shown to be effective in increasing the success rate. The combination of lactoferrin and antibiotics may be a useful alternative to triple therapy in the future.

Phages invade bacteria, using the nucleic acid of the host cell to replicate and produce fresh phages that lyse the host cell, thus acting as antimicrobials (Sousa et al., 2022). Yahara et al. showed that about one-fifth of H. pylori contains prophage genes (Yahara et al., 2019). Using phages to treat related diseases is safer and more reliable than conventional antibiotic therapy. Numerous phages target bacteria and can specifically destroy strains. Phages do not invade animal cells or even humans, so phage therapy is considered safe (Sousa et al., 2022). Cuomo et al. demonstrated the activity of Hp (H. pylori) phage in inhibiting the growth of strains of H. pylori. In addition, they used antibacterial lactoferrin to design a nano-system based on HP phage-lactoferrin hydroxyapatite. The bacteriostatic effect of the system is better than that of the phage group alone (Cuomo et al., 2020). Therefore, phages have been shown to be beneficial in the treatment of H. pylori contamination, especially in combination with other antimicrobial agents. However, there are few studies of phage therapy, so further data and studies are needed to support this approach as a first-line treatment.

Vaccination is a powerful tool for treating patients infected with H. pylori. Univalent vaccine is not as useful as multivalent vaccine in the treatment of helicobacter pylori infection (Guo et al., 2017). Studies have designed a multivalent epitope vaccine using urease polypeptides with immune adjuvants, CagA and VacA, to evaluate the efficacy of the vaccine against H. pylori infection in mice. The results showed that the vaccine promoted the production of more specific antibodies to CagA, VacA and immune adjuvants. In addition, adding polysaccharide adjuvant to the polyvalent vaccine group significantly reduced H. pylori levels in the stomachs of mice compared to the monovalent vaccine group (Guo et al., 2019). As a result, multivalent vaccines are becoming increasingly popular in medicine. Guo et al. designed a multivalent epitope vaccine using H. pylori adhesion molecules (urease, Lpp20, HpaA and CagL) and investigated the therapeutic potential of the vaccine in animal models infected with H. pylori. The results showed that the vaccine produced additional antibodies against the adhesion molecules in the mice (Guo et al., 2017). It has been reported that inactivated H. pylori whole-cell vaccine can reduce the colonization of H. pylori in the stomach by enhancing human mucosal immunity (Zhang et al., 2022). There is also a vector vaccine that has achieved excellent results in oral immunization. Katsande et al. used spores derived from Bacillus subtilis to design a vector vaccine expressing urease subunits (A and B), which was used orally to treat an animal model of H. pylori infection. The final results showed an increase in IgA levels and a significant reduction in the amount of H. pylori colonizing the mice’s stomachs after oral treatment (Katsande et al., 2023). In addition, a nano-delivery system based on N-2-hydroxypropyl trimethyl ammonium chloride chitosan/carboxymethyl chitosan was designed and used as an immune adjuvant to treat H. pylori infection in animal models. The results showed that the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-4, etc.) in mice increased significantly after the nano-drug treatment, which indicated that the nano-system could effectively promote the occurrence of immune response (Gao et al., 2022).

Phototherapy is the use of a laser to treat a laser-sensitive substance that secretes the bacteriocidal agent ROS after being stimulated. Also, the therapy does not create resistant strains as easily as antibiotics do. And ROS produced after laser irradiation can destroy the cell membranes of bacteria, causing the pathogenic bacteria to crack and die. Therefore, this therapy is a promising treatment for H. pylori (Im et al., 2021). Some studies have designed a photosensitive substance based on 3′-sialyl lactose coupled poly (L-lysine), which was orally infected with H. pylori in mice. The mice were treated with a gastroscope laser system. The content of H. pylori in the stomach of mice was significantly reduced when the laser treatment was over 1.2 J cm−2, and it was fully inhibited when it was over 2.4 J cm−2. In addition, when mice were treated with 4 J cm−2 laser, no damage to AGS cells was observed (Im et al., 2021). Phototherapy can destroy the biofilm of H. pylori. As such, it has a positive therapeutic effect on antibiotic-resistant strains. Because the surface of biofilm contains anions, Qiao et al. developed a new microbial targeted near-infrared photosensitive substance based on guanidine (positively charged) and photosensitizer to inhibit the growth of H. pylori. After laser treatment, the bacterial biofilm density was significantly less than before laser treatment, suggesting that phototherapy can considerably damage bacterial biofilms (Qiao et al., 2023). H. pylori was treated in vitro with a blue light-emitting diode. The results showed that after 6 min of treatment, the activity of urease produced by H. pylori was inhibited. In addition, more than half of the H. pylori biofilm was damaged after phototherapy compared to the group without phototherapy (Darmani et al., 2019). Curcumin and blue light emitting diodes have been used to treat H. pylori. The results showed that the number of H. pylori was significantly suppressed in the curcumin + blue light treatment group compared to the group without blue light irradiation (Darmani et al., 2020). Xiao et al. designed an antibody nanoprobe (gold nanostar coupled acid-sensitive cis-aconite) for in vivo infection with H. pylori. The probe killed all H. pylori bacteria in mice treated with near-infrared light. All of the probes were regularly excreted 7 days after entering the mice. Gastrointestinal symptoms caused by H. pylori gradually disappear within a month (Zhi et al., 2019). This approach remains promising for the successful treatment of H. pylori infection.

Helicobacter pylori infection is currently a non-negligible problem. The bacterium can colonize the human gastrointestinal tract and significantly increase the risk of stomach cancer in humans. Previous antibiotic treatments have caused resistance to H. pylori strains around the world, so an alternative treatment is being sought. Therefore, this paper focuses on the prevention and treatment of H. pylori, encompassing an in-depth exploration of its pathogenic mechanisms, transmission routes, and emerging therapeutic interventions. Based on H. pylori studies, we summarize the current status and treatment mechanisms of seven approaches, including phytotherapy, probiotic therapy, nano-delivery therapy, lactoferrin therapy, phage therapy, vaccine, and light therapy. The safety and non-resistance properties of phytotherapy and probiotics have been demonstrated by numerous studies, rendering them the preferred choice for second-line treatment. The use of nano-systems to deliver drugs can address the short retention time of drugs in the stomach, which considerably improves drug utilization. Lactoferrin therapy itself is safe and pollution-free, and is an excellent alternative therapy. Current phage therapies and vaccines exhibit targeted efficacy, yet their clinical application necessitates further investigation due to the limited availability of clinical data. Light therapy is still in its infancy, with limited research data and certain safety risks. All emerging therapies have achieved excellent results, but additional investigations are needed due to the lack of studies on the treatment mechanisms and clinical data.

ML: Data curation, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft. HG: Formal Analysis, Software, Writing – review & editing. JM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. ZiZ: Writing – review & editing. LZ: Writing – review & editing. FL: Writing – review & editing. SZ: Writing – review & editing. ZhZ: Writing – review & editing. SL: Writing – review & editing. HL: Writing – review & editing. JS: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the Qingdao People’s Livelihood Science and Technology Plan Project (23-3-8-xdny-l-nsh and 23-2-8-xdny-6-nsh), Qingdao Natural Science Foundation project (23-2-1-180-zyyd-jch), Key project of Shandong Province (2023TZXD047, 2023TZXD078), Innovation Ability Improvement Project of Science and Technology smes in Shandong Province (2022TSGC2520 and 2023TSGC0892), the Two Hundred Talents project of Yantai City in 2020, Major agricultural application technology Innovation projects of Shandong Province in 2018, and Demonstration and promotion project of talent introduction achievements in Shandong Province in 2019.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abd El-Moaty, H. I., Soliman, N. A., Hamad, R. S., Ismail, E. H., Sabry, D. Y., and Khalil, M. M. H. (2021). Comparative therapeutic effects of Pituranthos tortuosus aqueous extract and phyto-synthesized gold nanoparticles on Helicobacter pylori, diabetic and cancer proliferation. S. Afr. J. Bot. 139, 167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2021.02.009

Abdel-Baki, P. M., El-Sherei, M. M., Khaleel, A. E., Abdel-Aziz, M. M., and Okba, M. M. (2022). Irigenin, a novel lead from Iris confusa for management of Helicobacter pylori infection with selective COX-2 and HpIMPDH inhibitory potential. Sci. Rep. 12:11457. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-15361-w

Adlekha, S., Chadha, T., Krishnan, P., and Sumangala, B. (2013). Prevalence of helicobacter pylori infection among patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in a medical college hospital in Kerala, India. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 3, 559–563. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.122109

Aiba, Y., Ishikawa, H., Tokunaga, M., and Komatsu, Y. (2017). Anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of non-living, heat-killed form of lactobacilli including Lactobacillus johnsonii no.1088. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 364:fnx102. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx102

Aiba, Y., Nakano, Y., Koga, Y., Takahashi, K., and Komatsu, Y. (2015). A highly acid-resistant novel strain of Lactobacillus johnsonii no. 1088 has antibacterial activity, including that against helicobacter pylori, and inhibits gastrin-mediated acid production in mice. Microbiology 4, 465–474. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.252

Akar, M., Aydın, F., Kayman, T., Abay, S., and Karakaya, E. (2021). Detection of Helicobacter pylori by invasive tests in adult dyspeptic patients and antibacterial resistance to six antibiotics, including rifampicin in Turkey. Is clarithromycin resistance rate decreasing? Turk J Med Sci 51, 1445–1464. doi: 10.3906/sag-2101-69

Ali, E., Arshad, N., Bukhari, N. I., Nawaz Tahir, M., Zafar, S., Hussain, A., et al. (2020). Linking traditional anti-ulcer use of rhizomes of Bergenia ciliata (haw.) to its anti-Helicobacter pylori constituents. Nat. Prod. Res. 34, 541–544. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2018.1488711

Alkim, H., Koksal, A. R., Boga, S., Sen, I., and Alkim, C. (2017). Role of bismuth in the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Am. J. Ther. 24, e751–e757. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000389

Al-Sayed, E., Gad, H. A., and El-Kersh, D. M. (2021). Characterization of four piper essential oils (GC/MS and ATR-IR) coupled to chemometrics and their anti-Helicobacter pylori activity. ACS Omega 6, 25652–25663. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c03777

Alvarado-Esquivel, C. (2013). Seroepidemiology of helicobacter pylori infection in pregnant women in rural Durango, Mexico. Int. J. Biomed. Sci. 9, 224–229. doi: 10.59566/IJBS.2013.9224

Amin, M. K., and Boateng, J. S. (2022). Enhancing stability and mucoadhesive properties of chitosan nanoparticles by surface modification with sodium alginate and polyethylene glycol for potential Oral mucosa vaccine delivery. Mar. Drugs 20:156. doi: 10.3390/md20030156

Ansari, S., and Yamaoka, Y. (2019). Helicobacter pylori virulence factors exploiting gastric colonization and its pathogenicity. Toxins 11:677. doi: 10.3390/toxins11110677

Arunachalam, K., Damazo, A. S., Pavan, E., Oliveira, D. M., Figueiredo, F., Machado, M. T. M., et al. (2019). Cochlospermum regium (Mart. Ex Schrank) Pilg.: evaluation of chemical profile, gastroprotective activity and mechanism of action of hydroethanolic extract of its xylopodium in acute and chronic experimental models. J. Ethnopharmacol. 233, 101–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.01.002

Athaydes, B. R., Tosta, C., Carminati, R. Z., Kuster, R. M., Kitagawa, R. R., and Gonçalves, R. (2022). Avocado (Persea americana mill.) seeds compounds affect Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric adenocarcinoma cells growth. J. Funct. Foods 99:105352. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2022.105352

Ayoub, I. M., Abdel-Aziz, M. M., Elhady, S. S., Bagalagel, A. A., Malatani, R. T., and Elkady, W. M. (2022). Valorization of Pimenta racemosa essential oils and extracts: GC-MS and LC-MS phytochemical profiling and evaluation of Helicobacter pylori inhibitory activity. Molecules 27:7965. doi: 10.3390/molecules27227965

Bakka, A. S., and Salih, B. A. (2002). Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic subjects in Libya. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 43, 265–268. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(02)00411-x

Baryshnikova, N. V., Ilina, A. S., Ermolenko, E. I., Uspenskiy, Y. P., and Suvorov, A. N. (2023). Probiotics and autoprobiotics for treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. World J. Clin. Cases 11, 4740–4751. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i20.4740

Bastos, J., Peleteiro, B., Barros, R., Alves, L., Severo, M., de Fátima Pina, M., et al. (2013). Sociodemographic determinants of prevalence and incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Portuguese adults. Helicobacter 18, 413–422. doi: 10.1111/hel.12061

Benajah, D. A., Lahbabi, M., Alaoui, S., el Rhazi, K., el Abkari, M., Nejjari, C., et al. (2013). Prevalence of helicobacter pylori and its recurrence after successful eradication in a developing nation (Morocco). Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 37, 519–526. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2013.02.003

Bener, A., Adeyemi, E. O., Almehdi, A. M., Ameen, A., Beshwari, M., Benedict, S., et al. (2006). Helicobacter pylori profile in asymptomatic farmers and non-farmers. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 16, 449–454. doi: 10.1080/09603120601093428

Binh, T. T., Shiota, S., Nguyen, L. T., Ho, D. D. Q., Hoang, H. H., Ta, L., et al. (2013). The incidence of primary antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Vietnam. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 47, 233–238. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182676e2b

Boyanova, L., Gergova, G., Kandilarov, N., Boyanova, L., Yordanov, D., Gergova, R., et al. (2023). Geographic distribution of antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori: a study in Bulgaria. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 70, 79–83. doi: 10.1556/030.2023.01940

Boyanova, L., Gergova, G., Markovska, R., Yordanov, D., and Mitov, I. (2017). Bacteriocin-like inhibitory activities of seven Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus strains against antibiotic susceptible and resistant Helicobacter pylori strains. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 65, 469–474. doi: 10.1111/lam.12807

Boyanova, L., Nikolov, R., Gergova, G., Evstatiev, I., Lazarova, E., Kamburov, V., et al. (2010). Two-decade trends in primary Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics in Bulgaria. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 67, 319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.03.010

Bruno, G., Rocco, G., Zaccari, P., Porowska, B., Mascellino, M. T., and Severi, C. (2018). Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric dysbiosis: can probiotics administration be useful to treat this condition? Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2018, 1–7. doi: 10.1155/2018/6237239

Cesa, S., Sisto, F., Zengin, G., Scaccabarozzi, D., Kokolakis, A. K., Scaltrito, M. M., et al. (2019). Phytochemical analyses and pharmacological screening of neem oil. S. Afr. J. Bot. 120, 331–337. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2018.10.019

Chama, Z., Titsaoui, D., Benabbou, A., Hakem, R., and Djellouli, B. (2020). Effect of Thymus vulgaris oil on the growth of Helicobacter pylori. South Asian J Exp Biol 10, 374–382. doi: 10.38150/sajeb.10(6).p374-382

Chauhan, N., Tay, A. C. Y., Marshall, B. J., and Jain, U. (2019). Helicobacter pylori VacA, a distinct toxin exerts diverse functionalities in numerous cells: an overview. Helicobacter 24:e12544. doi: 10.1111/hel.12544

Ciccaglione, A. F., Di Giulio, M., Di Lodovico, S., Di Campli, E., Cellini, L., and Marzio, L. (2019). Bovine lactoferrin enhances the efficacy of levofloxacin-based triple therapy as first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: an in vitro and in vivo study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 74, 1069–1077. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky510

Cuomo, P., Papaianni, M., Fulgione, A., Guerra, F., Capparelli, R., and Medaglia, C. (2020). An innovative approach to control H. pylori-induced persistent inflammation and colonization. Microorganisms 8:1214. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8081214

Czerucka, D., and Rampal, P. (2019). Diversity of saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745 mechanisms of action against intestinal infections. World J. Gastroenterol. 25, 2188–2203. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i18.2188

Dang, C., Okagu, O., Sun, X., and Udenigwe, C. C. (2022). Bioinformatics analysis of adhesin-binding potential and ADME/tox profile of anti-Helicobacter pylori peptides derived from wheat germ proteins. Heliyon 8:e09629. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09629

Darmani, H., Am Smadi, E., and Mb Bataineh, S. (2019). Blue light emitting diodes cripple Helicobacter pylori by targeting its virulence factors. Minerva Gastroenterol. Dietol. 65, 187–192. doi: 10.23736/S1121-421X.19.02593-5

Darmani, H., Smadi, E. A. M., and Bataineh, S. M. B. (2020). Blue light emitting diodes enhance the antivirulence effects of curcumin against Helicobacter pylori. J. Med. Microbiol. 69, 617–624. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001168

Dinat, S., Orchard, A., and Van Vuuren, S. (2023). A scoping review of African natural products against gastric ulcers and Helicobacter pylori. J. Ethnopharmacol. 301:115698. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115698

Ding, S.-Z., du, Y. Q., Lu, H., Wang, W.-H., Cheng, H., Chen, S.-Y., et al. (2022). Chinese consensus report on family-based Helicobacter pylori infection control and management (2021 edition). Gut 71, 238–253. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325630

Do, A. D., Chang, C.-C., Su, C.-H., and Hsu, Y.-M. (2021). Lactobacillus rhamnosus JB3 inhibits Helicobacter pylori infection through multiple molecular actions. Helicobacter 26:e12806. doi: 10.1111/hel.12806

Duan, M., Li, Y., Liu, J., Zhang, W., Dong, Y., Han, Z., et al. (2023). Transmission routes and patterns of helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 28:e12945. doi: 10.1111/hel.12945

Egas, V., Salazar-Cervantes, G., Romero, I., Méndez-Cuesta, C. A., Rodríguez-Chávez, J. L., and Delgado, G. (2018). Anti-Helicobacter pylori metabolites from Heterotheca inuloides (Mexican arnica). Fitoterapia 127, 314–321. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2018.03.001

Elbestawy, M. K. M., El-Sherbiny, G. M., and Moghannem, S. A. (2023). Antibacterial, antibiofilm and anti-inflammatory activities of eugenol clove essential oil against resistant Helicobacter pylori. Molecules 28:2448. doi: 10.3390/molecules28062448

Eshraghian, A. (2014). Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection among the healthy population in Iran and countries of the eastern Mediterranean region: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 17618–17625. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17618

Espinosa-Rivero, J., Rendón-Huerta, E., and Romero, I. (2015). Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori growth and its colonization factors by Parthenium hysterophorus extracts. J. Ethnopharmacol. 174, 253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.08.021

Fagni Njoya, Z. L., Mbiantcha, M., Djuichou Nguemnang, S. F., Matah Marthe, V. M., Yousseu Nana, W., Madjo Kouam, Y. K., et al. (2022). Anti-Helicobacter pylori, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activities of trunk bark of Alstonia boonei (Apocynaceae). Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 1–15. doi: 10.1155/2022/9022135

Fahmy, N. M., Al-Sayed, E., Michel, H. E., El-Shazly, M., and Singab, A. N. B. (2020). Gastroprotective effects of Erythrina speciosa (Fabaceae) leaves cultivated in Egypt against ethanol-induced gastric ulcer in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 248:112297. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.112297

Feng, S., Lin, J., Zhang, X., Hong, X., Xu, W., Wen, Y., et al. (2023). Role of AlgC and GalU in the intrinsic antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori. Infect Drug Resist 16, 1839–1847. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S403046

Flores-Treviño, S., Mendoza-Olazarán, S., Bocanegra-Ibarias, P., Maldonado-Garza, H. J., and Garza-González, E. (2018). Helicobacter pylori drug resistance: therapy changes and challenges. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12, 819–827. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2018.1496017

Forooghi Nia, F., Rahmati, A., Ariamanesh, M., Saeidi, J., Ghasemi, A., and Mohtashami, M. (2023). The anti-Helicobacter pylori effects of Limosilactobacillus reuteri strain 2892 isolated from camel milk in C57BL/6 mice. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 39:119. doi: 10.1007/s11274-023-03555-x

Gamal El-Din, M. I., Youssef, F. S., Ashour, M. L., Eldahshan, O. A., and Singab, A. N. B. (2018). Comparative analysis of volatile constituents of Pachira aquatica Aubl. And Pachira glabra Pasq., their anti-mycobacterial and anti-Helicobacter pylori activities and their metabolic discrimination using chemometrics. J Essential Oil Bear Plants 21, 1550–1567. doi: 10.1080/0972060X.2019.1571950

Gao, Y., Gong, X., Yu, S., Jin, Z., Ruan, Q., Zhang, C., et al. (2022). Immune enhancement of N-2-hydroxypropyl trimethyl ammonium chloride chitosan/carboxymethyl chitosan nanoparticles vaccine. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 220, 183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.08.073

Garcia-Castillo, V., Zelaya, H., Ilabaca, A., Espinoza-Monje, M., Komatsu, R., Albarracín, L., et al. (2018). Lactobacillus fermentum UCO-979C beneficially modulates the innate immune response triggered by Helicobacter pylori infection in vitro. Benef Microbes 9, 829–841. doi: 10.3920/BM2018.0019

Garvey, E., Rhead, J., Suffian, S., Whiley, D., Mahmood, F., Bakshi, N., et al. (2023). High incidence of antibiotic resistance amongst isolates of Helicobacter pylori collected in Nottingham, UK, between 2001 and 2018. J. Med. Microbiol. 72. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.001776

Gawron, A. J., Shah, S. C., Altayar, O., Davitkov, P., Morgan, D., Turner, K., et al. (2020). AGA technical review on gastric intestinal metaplasia-natural history and clinical outcomes. Gastroenterology 158, 705–731.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.001

Gemilyan, M., Hakobyan, G., Benejat, L., Allushi, B., Melik-Nubaryan, D., Mangoyan, H., et al. (2019). Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and antibiotic resistance profile in Armenia. Gut Pathog 11:28. doi: 10.1186/s13099-019-0310-0

Goderska, K., Agudo Pena, S., and Alarcon, T. (2018). Helicobacter pylori treatment: antibiotics or probiotics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8535-7

Gottesmann, M., Paraskevopoulou, V., Mohammed, A., Falcone, F. H., and Hensel, A. (2020). BabA and LPS inhibitors against Helicobacter pylori: pectins and pectin-like rhamnogalacturonans as adhesion blockers. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104, 351–363. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-10234-1

Guerra-Valle, M., Orellana-Palma, P., and Petzold, G. (2022). Plant-based polyphenols: anti-Helicobacter pylori effect and improvement of gut microbiota. Antioxidants 11:109. doi: 10.3390/antiox11010109

Guevara, B., and Cogdill, A. G. (2020). Helicobacter pylori: a review of current diagnostic and management strategies. Dig. Dis. Sci. 65, 1917–1931. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06193-7

Günes-Bayir, A., Kiziltan, H. S., Kocyigit, A., Güler, E. M., Karataş, E., and Toprak, A. (2017). Effects of natural phenolic compound carvacrol on the human gastric adenocarcinoma (AGS) cells in vitro. Anticancer Drugs 28, 522–530. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000491

Guo, L., Hong, D., Wang, S., Zhang, F., Tang, F., Wu, T., et al. (2019). Therapeutic protection against H. pylori infection in Mongolian gerbils by Oral immunization with a tetravalent epitope-based vaccine with polysaccharide adjuvant. Front. Immunol. 10:1185. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01185

Guo, L., Yin, R., Xu, G., Gong, X., Chang, Z., Hong, D., et al. (2017). Immunologic properties and therapeutic efficacy of a multivalent epitope-based vaccine against four Helicobacter pylori adhesins (urease, Lpp20, HpaA, and CagL) in Mongolian gerbils. Helicobacter 22:12428. doi: 10.1111/hel.12428

Hablass, F. H., Lashen, S. A., Department of Internal Medicine, University of Alexandria School of Medicine, Alexandria, Egypt, and Alsayed, E. A. (2021). Efficacy of lactoferrin with standard triple therapy or sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized controlled trial. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 32, 742–749. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2021.20923

Hadke, J., and Khan, S. (2021). Preparation of Sterculia foetida-pullulan-based semi-interpenetrating polymer network Gastroretentive microspheres of amoxicillin trihydrate and optimization by response surface methodology. Turk J Pharm Sci 18, 388–397. doi: 10.4274/tjps.galenos.2020.33341

Hamasaki, N., Ishii, E., Tominaga, K., Tezuka, Y., Nagaoka, T., Kadota, S., et al. (2000). Highly selective antibacterial activity of novel alkyl quinolone alkaloids from a Chinese herbal medicine, Gosyuyu (Wu-chu-Yu), against Helicobacter pylori in vitro. Microbiol. Immunol. 44, 9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb01240.x

Hanafi, M. I., and Mohamed, A. M. (2013). Helicobacter pylori infection: seroprevalence and predictors among healthy individuals in Al Madinah, Saudi Arabia. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 88, 40–45. doi: 10.1097/01.EPX.0000427043.99834.a4

Harb, A. H., El Reda, Z. D., Sarkis, F. S., Chaar, H. F., and Sharara, A. I. (2015). Efficacy of reduced-dose regimen of a capsule containing bismuth subcitrate, metronidazole, and tetracycline given with amoxicillin and esomeprazole in the treatment of Helicobacter Pylori infection. United Eur Gastroenterol J 3, 95–96. doi: 10.1177/2050640614560787

Harmati, M., Gyukity-Sebestyen, E., Dobra, G., Terhes, G., Urban, E., Decsi, G., et al. (2017). Binary mixture of Satureja hortensis and Origanum vulgare subsp. hirtum essential oils: in vivo therapeutic efficiency against Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 22. doi: 10.1111/hel.12350

Harsha, S. (2012). Dual drug delivery system for targeting H. pylori in the stomach: preparation and in vitro characterization of amoxicillin-loaded Carbopol® nanospheres. Int. J. Nanomedicine 7, 4787–4796. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S34312

Hasna, B., Houari, H., Koula, D., Marina, S., Emilia, U., and Assia, B. (2023). In vitro and in vivo study of combined effect of some Algerian medicinal plants and probiotics against Helicobacter pylori. Microorganisms 11:1242. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11051242