- 1Qingdao Cancer Prevention and Treatment Research Institute, Qingdao Central Hospital, University of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences (Qingdao Central Medical Group), Qingdao, China

- 2Department of Clinical Laboratory, Qingdao Hospital, University of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences (Qingdao Municipal Hospital), Qingdao, China

- 3Medical Ethics Committee Office, Qingdao Central Hospital, University of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences (Qingdao Central Medical Group), Qingdao, China

- 4College of Life and Geographic Sciences, Key Laboratory of Biological Resources and Ecology of Pamirs Plateau in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, Kashi University, Kashi, China

- 5Institute of Evolution & Marine Biodiversity, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China

- 6Department of Oncology, Qingdao Central Hospital, University of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences (Qingdao Central Medical Group), Qingdao, China

Cancer is the most common cause of human death worldwide, posing a serious threat to human health and having a negative impact on the economy. In the past few decades, significant progress has been made in anticancer therapies, but traditional anticancer therapies, including radiation therapy, surgery, chemotherapy, molecular targeted therapy, immunotherapy and antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), have serious side effects, low specificity, and the emergence of drug resistance. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop new treatment methods to improve efficacy and reduce side effects. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) exist in the innate immune system of various organisms. As the most promising alternatives to traditional drugs for treating cancers, some AMPs also have been proven to possess anticancer activities, which are defined as anticancer peptides (ACPs). These peptides have the advantages of being able to specifically target cancer cells and have less toxicity to normal tissues. More and more studies have found that marine and terrestrial animals contain a large amount of ACPs. In this article, we introduced the animal derived AMPs with anti-cancer activity, and summarized the types of tumor cells inhibited by ACPs, the mechanisms by which they exert anti-tumor effects and clinical applications of ACPs.

1 Introduction

Cancer has emerged as a major cause of human death worldwide, which poses a serious threat to public health and have a negative impact on the economy (Deo et al., 2022). In the past few decades, our understanding of the origin of cancer has developed to a widespread acceptance that cancer is the result of an evolutionary process driven by natural selection of mutations, subsequent genetic and carcinogenic mutations (Somarelli et al., 2020). Based on statistics from the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2019, cancer is the first or second major cause of death before the age of 70 in 112 out of 183 countries, and ranks third or fourth out of 23 other countries (Sung et al., 2021). According to GLOBOCAN 2020 published by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), in 2020, there were 19.3 million new cancer cases and 9.9 million new cancer deaths worldwide (Ferlay et al., 2020). The number of cancer deaths will keep growing, with an estimated 13 million deaths by 2030 (Asasira et al., 2022). Among all the cancers, female breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer, closely followed by lung, colorectal, prostate, and gastric cancers. Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death, followed by colorectal, liver, gastric and female breast cancers (Ferlay et al., 2020). The characteristics of all types of neoplastic cells are unregulated cell growth caused by genetic mutations in a small amount of inherited or environmental stimuli, which can achieve replication immortality, avoid cell death, escape from the host immune system, and so on (Schiliro and Firestein, 2021). Well-known signaling pathways, such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), Wnt, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), Notch, Hippo, Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), Hedgehog (Hh), and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathways, as well as transcription factors, including heat shock transcription factor 1 (HSF1), hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), Snail, P53, and Twist, constitute complex regulatory networks to modulate the formation, activation, heterogeneity, metabolic characteristics and malignant phenotype of cancers (Fang et al., 2023).

The current therapeutic strategies for treating cancer, include radiation therapy, surgery, chemotherapy, molecular targeted therapy, immunotherapy and antibody-drug conjugate (ADC). For example, conventional chemotherapy, one of the most widely used cancer treatment methods, kills cancer cells by inhibiting cell growth or division. Chemotherapeutics (i.e., alkylating agents, antimetabolic agents, antineoplastic antibiotics, platinating agents, and plant-derived alkaloids) exert anti-tumor effects through direct cytotoxic effects or indirectly by affecting the cell cycle (Okunaka et al., 2021). Progress in molecular targeted drugs has prolonged survival (Li et al., 2023), particularly in patients with lung cancer harboring epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations (i.e., erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib, dacomitinib, and osimertinib) or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangement (i.e., ceritinib, alectinib, brigatinib, ensartinib, lorlatinib), and in patients with breast cancer harboring human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) amplification (i.e., trastuzumab). Furthermore, cancer immunotherapies targeting the interaction of programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) with its major ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2 are considered to usher in the era of modern oncology. Drugs that block PD-1 (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and cemiplimab) or PD-L1 (atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab) promote endogenous anti-tumor immunity and have been considered effective strategies for cancer treatment due to their broad activity spectrum (Topalian et al., 2020). It is worth noting that in recent years, ADC has become a promising cancer treatment method for solid and hematological malignancies. ADC assembles cytotoxic drugs (payloads) by covalently linking them to monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and delivering them to tumor tissues expressing their specific antigens, with the advantage of low toxicity and improved treatment rates (Fuentes-Antrás et al., 2023). Currently, the US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) has approved 13 types of ADCs for the treatment of various types of solid tumors and hematological malignancies (Maiti et al., 2023). However, there are still several obstacles that will affect and limit their curative effect. These treatment modalities have been found to have no specificity for cancer cells resulting in affecting the cell division of normal cells, thereby damaging the repair of healthy tissues (Ziaja et al., 2020). Besides, cancer patients often develop multi-drug resistance (MDR) to chemotherapeutics acquired by tumors (Ziaja et al., 2020). Thus, the development of novel tumor-targeted therapies that could effectively target tumor cells with lower/minor toxicity to normal cells and battle drug resistance is a top priority for treating cancer. In recent decades, researchers have focused on finding new anticancer strategies and have shifted their attention to antimicrobial peptides (AMPs).

AMPs are natural bioactive peptides with diverse structural properties that are produced by bacteria, fungi, plants and animals, and act as the first line of defense against invading pathogens (Wang G. et al., 2022). In 1981, the first important animal derived AMP named cecropins was identified from the Cecropia silk moth, followed by magainin from Xenopus laevis in 1987 (Steiner et al., 1981; Zasloff, 1987). After that, numerous other natural AMPs were discovered in almost all organisms (Han et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2021). Since then, more than 3000 AMPs have been deposited in the Antimicrobial Peptide Database.1 In addition to having broad-spectrum antibacterial effects, an increasing number of AMPs have been proven to have other physiological functions including antifungal, antiviral, antioxidative, antithrombotic, antihypertensive and immunomodulatory (Macedo et al., 2021; Quah et al., 2023). Importantly, many AMPs also demonstrated possess antitumor activity. Most AMPs rely on destructing cell membranes or changing cell membrane permeability to kill bacteria or cancer cells (Lyu et al., 2019), but some AMPs can also via non-membranes disruptive mechanisms exert anti-cancer effects. For instance, cecropins and LL-37 could induce apoptosis and necrosis of tumor cells (Qin et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2021), melittin could suppress tumor angiogenesis and reactivate immune cells (Zhang and Chen, 2017; Duffy et al., 2020).

Anticancer peptides (ACPs) have many unique advantages compared to chemotherapy drugs, such as biocompatibility, efficient therapeutic efficacy, low risk of drug resistance appearing in tumor cells, and limited or no toxicity against mammalian cells (Karami Fath et al., 2022; Lath et al., 2023). In addition, ACPs have immunogenicity and low difficulty in synthesis and modification, with a short half-life in vivo, making it possible for them to be put into clinical anti-cancer drug candidates (Karami Fath et al., 2022). In this review, we summarize and describe the anticancer effects and the mode of action of AMPs derived from marine and terrestrial animal sources based on their order of evolution, and we further discuss the clinical applications of ACPs.

2 The structural classifications and selective recognition to tumor cells of AMPs

Generally, the naturally produced AMPs are cationic and amphipathic, with the net charge at neutral pH ranging from + 2 to + 9 (Costa et al., 2011). Most AMPs are short in length, usually containing 10–50 L-amino acids, which are rich in lysine, arginine and large amounts of other hydrophobic residues (>30%) (Maroti et al., 2011). So why can AMPs inhibit or kill bacteria? Notably, the surfaces of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria are rich in lipopolysaccharides and teichoic acid, which result in a net negative charge generated on the cell membrane surface. Therefore, the cationic and amphipathic nature of AMPs can generate electrostatic interactions with negative charges on the surface of bacteria and interact with various hydrophilic and hydrophobic components (Luo and Song, 2021). At present, the AMPs can be classified as α-helical, β-sheet, mixed α-helical/β-sheet, as well as cyclic and unstructured (neither α-helix nor β-sheet) AMPs according to the secondary structure (Liang et al., 2020). Among them, the α-helix peptides are the most studied type of AMPs. In aqueous solution, α-helical AMPs possess a linear structure, but when come in contact with bacterial membranes or organic solvents these adopt an amphipathic helical structure, which contributes to insert into the cell membrane (Mahlapuu et al., 2016). Specifically, α-helical AMPs adhere to negatively charged bacterial membranes through electrostatic interactions, inserting their hydrophobic domains into the bacterial membrane, resulting in membrane deformation (Liang et al., 2020). The two most studied and representative peptides in this group are human LL-37 and magainin 2 (MG2) (see sections “3.2.2 ACPs derived from amphibians and 3.2.4 ACPs derived from mammals” for details). β-sheet AMPs are typically molecules composed of at least two antiparallel β-sheet, which contain 6 to 8 cysteine residues and are further stabilized by forming two or more disulfide bonds (Lewies et al., 2015). At present, defensins are the most widely studied family of β-sheet AMPs (see section “3.2.4 ACPs derived from mammals” for details). Tachyplesin I is another β-sheet AMPs which forms a uniquely rigid and stable β-hairpin with three tandem tetrapeptide repeats (Luan et al., 2021). The third type, α-helix/β-sheet mixed structure, stabilized three to four disulfide bond bridges, is another major structural motif of some AMPs. For instance, cysteine-stabilized αβ (CSαβ) defensins consist of a single α-helix and β-sheets with two or three antiparallel chains, with the length varying from 34 to 54 amino acid residues (Dias Rde and Franco, 2015). Insect heliomicin and fungi defensin eurocin are two typical representatives of CSαβ defensins. The fourth type of cyclic peptides contains one or two disulfide bonds to form this conformation. The typical representative is bacteriocins, which normally come from bacteria rather than animals. For example, plantacyclin B21AG and bacteriocins enterocin 7A are two circular bacteriocins, which display antimicrobial activity. Finally, the unstructured (neither α-helix nor β-sheet) AMPs rich in specific amino acids such as tryptophan, proline, and arginine, and typically around 15 amino acids, exhibit a linear structure (Schibli et al., 2002). This unstructured type of AMPs usually presents a disordered or loose curly structure before interaction with the lipid bilayer, and will quickly fold into active conformation once contact with the membrane (Johansson et al., 1998). Indolicidin, from cytoplasmic granules of bovine neutrophils, is a typical linear AMP rich in tryptophan and proline (Smirnova et al., 2020). LF11 is another short linear AMP based on the human lactoferrin (Zhang et al., 2022).

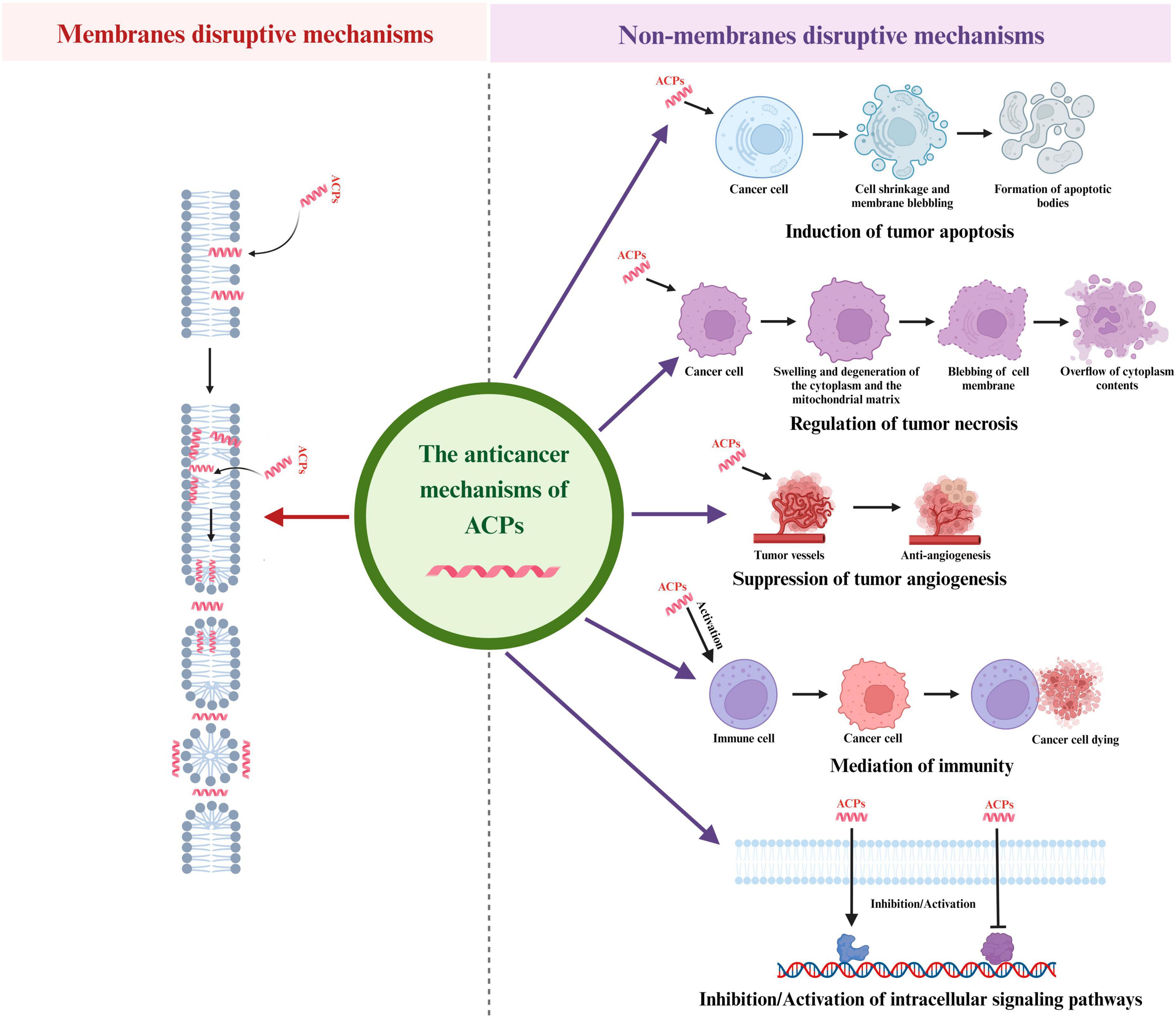

In the manner of cell membrane destruction modes, ACPs and AMPs have similar mechanisms leading to thinning, forming pores, changing the degree of curvature of the cell membrane, etc. These actions can lead to changes in the overall membrane potential of the cell membrane, and loss of membrane potential gradient, thus stopping the synthesis of ATP and the termination of cell metabolism, and ultimately leading to the death of cells (Chiangjong et al., 2020; Luan et al., 2021). There are three commonly recognized types of cell membrane destruction modes, i.e., the barrel-stave model, the toroidal model, and the carpet model (Li et al., 2021; Erdem Büyükkiraz and Kesmen, 2022). The barrel-stave model has the most extensively study. In this model, after binding to the cell membrane, ACPs/AMPs are arranged vertically with the cell membrane and aggregate with each other to form a cylindrical insertion into the cell membrane, thereby forming pores on the cell membrane. In the toroidal model, after the ACPs/AMPs combine with the cell membrane, the cell membrane bends inward to form a hole, which is composed of the hydrophilic head of the lipid bilayer and ACPs/AMPs. The carpet model has a strong destructive effect on cell membranes. In the model, ACPs/AMPs bind to the cell membrane and are parallel to the surface of the cell membrane. After reaching a certain concentration of ACPs/AMPs, the cell membrane is broken down into small particles one by one.

In the manner of non-membrane destruction modes, ACPs could display anti-tumor activity by mediating the necrosis or apoptosis of cancer cells, inhibiting angiogenesis, immune cell recruitment and activating certain regulatory functional proteins (Huan et al., 2020; Jafari et al., 2022).

Why do ACPs recognize tumor cells specifically? In this respect, the abundant presence of anions on the surface of tumor cells significantly increases the electrostatic interaction between ACPs and the surface of cancer cells. However, compared with tumor cells, healthy cell membranes have zwitterion phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin in an outer leaflet and anionic phosphatidylserine (PS) and the phosphatidylethanolamine in the inner leaflet with the asymmetric distribution (Chiangjong et al., 2020). The outer leaflet of the plasma membrane of tumor cells usually contains a large amount of negatively charged PS, which is 3–7 times more than normal cells (Haider and Soni, 2022). In addition, anionic molecules such as O-glycosylated mucins, sialylated gangliosides and heparin sulfate, which are overexpressed in tumor tissue and closely related to the occurrence and progression of tumors, also greatly increase the number of negative charges on the surface of tumor cells (Luong et al., 2020). Moreover, the differences in membrane fluidity and cell surface area between tumor cells and normal cells are also considered important reasons for the preferential action of ACPs on tumor cells. Cholesterol accumulates in a larger amount on the cell membrane of normal cells than in cancer cells, which could effectively reduce the membrane fluidity to prevent cationic peptides from inserting into the cell membrane (Norouzi et al., 2022). On the contrary, most cancer cells have lower cholesterol content on their membranes, making them more fluid than normal cells (Luan et al., 2021), leading to ACP being more prone to disrupting membrane stability. Another interesting characteristic of cancer cells is the expression of a large number of microvilli in their plasma membrane, which increases the surface area of the membrane and thus increases the affinity of ACPs to tumor cells (Luan et al., 2021).

3 Animal sources of AMPs with anticancer activity

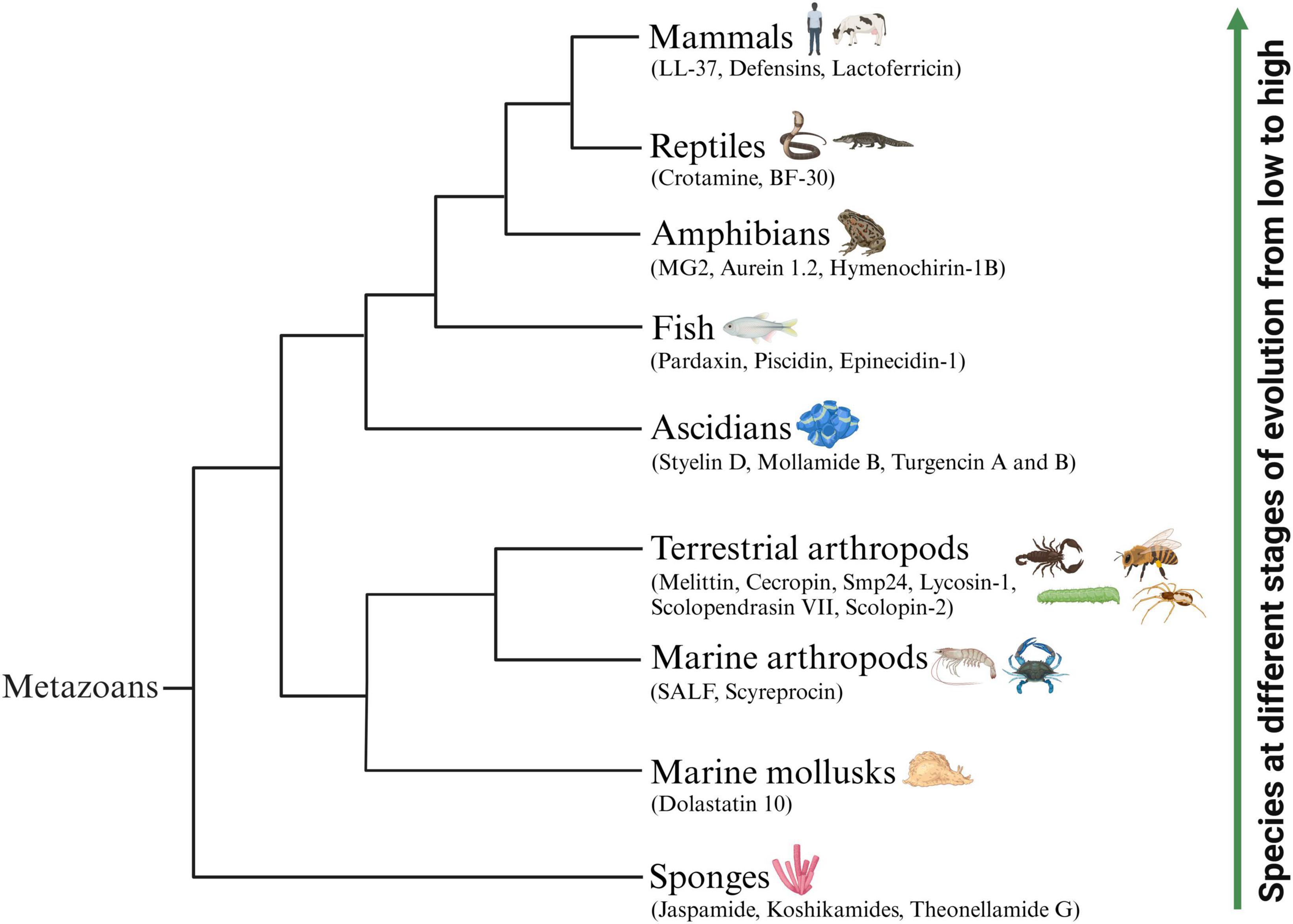

The natural environment is considered a vital source of novel therapeutic drugs. The ocean, accounting for approximately 71% of the earth’s surface area, represents more than half of the biodiversity worldwide. Marine animals are important providers of natural active peptides (Chakniramol et al., 2022). At present, many bioactive peptides with anticancer potential have been identified from various marine animals (Figure 1), mainly concentrated in sponges, mollusks, marine arthropods, ascidians and fish (Zhang et al., 2021; Chakniramol et al., 2022; Wong et al., 2023). Some known ACPs from terrestrial animals (Figure 1), including terrestrial arthropods, amphibians, reptiles and mammals, have also been proven to have broad application prospects, serving as novel anti-tumor drugs or auxiliary therapeutic measures for cancer treatment (Pan et al., 2020; Tornesello et al., 2020). In Tables 1, 2, we comprehensively classified the natural ACPs of marine and terrestrial animals based on their order of evolution to the greatest extent possible, and provided a detailed introduction to the representative ACPs among them in the following section.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of representative animal-origin ACPs according to the animal’s evolution order. Some known ACPs which have been identified from various marine animals mainly concentrated in sponges, mollusks, marine arthropods, ascidians and fish. Several representative ACPs also isolated from terrestrial animals including terrestrial arthropods, amphibians, reptiles and mammals.

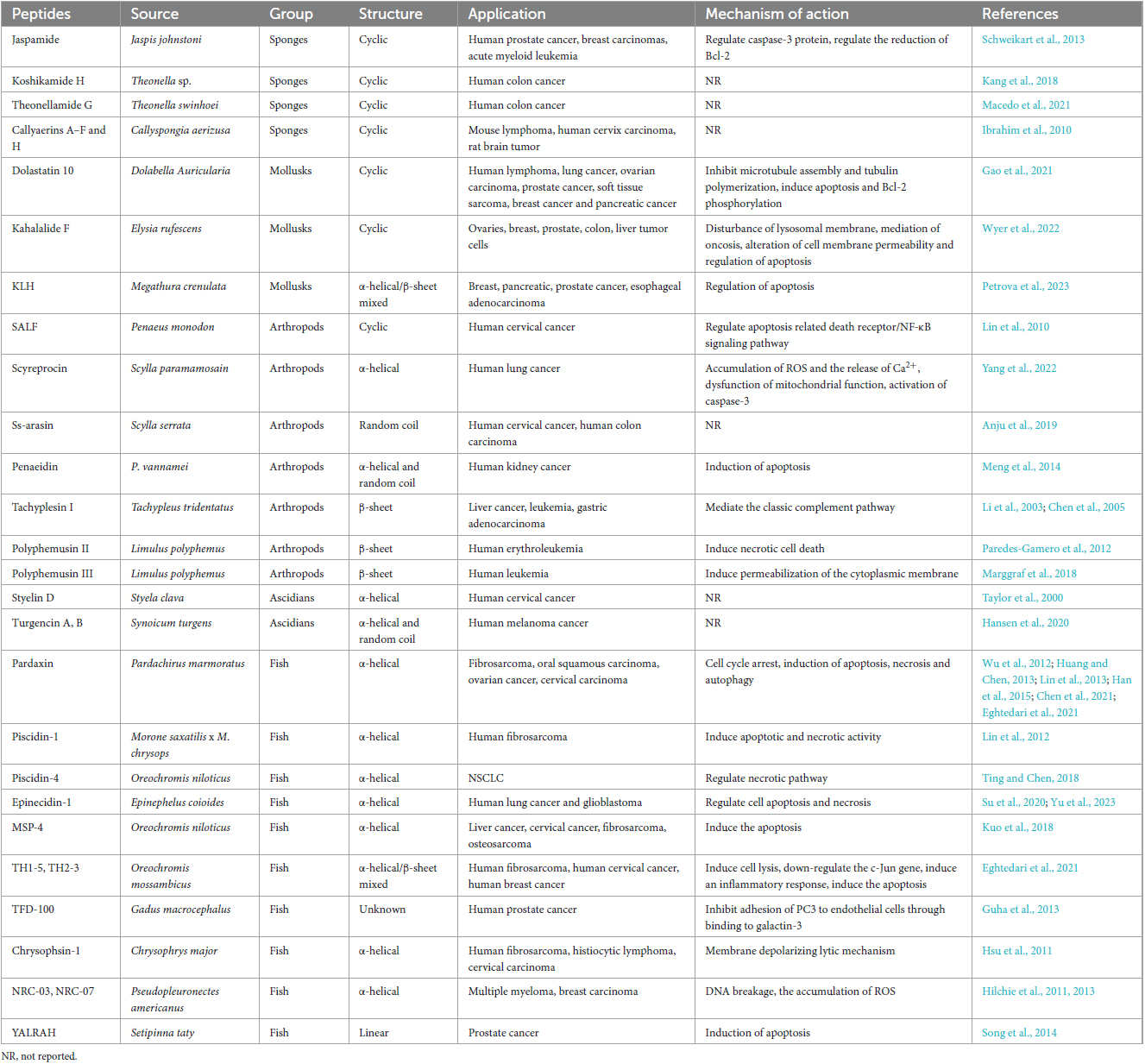

Table 1. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) with potential anticancer activity derived from marine animals, their application and mechanisms of action.

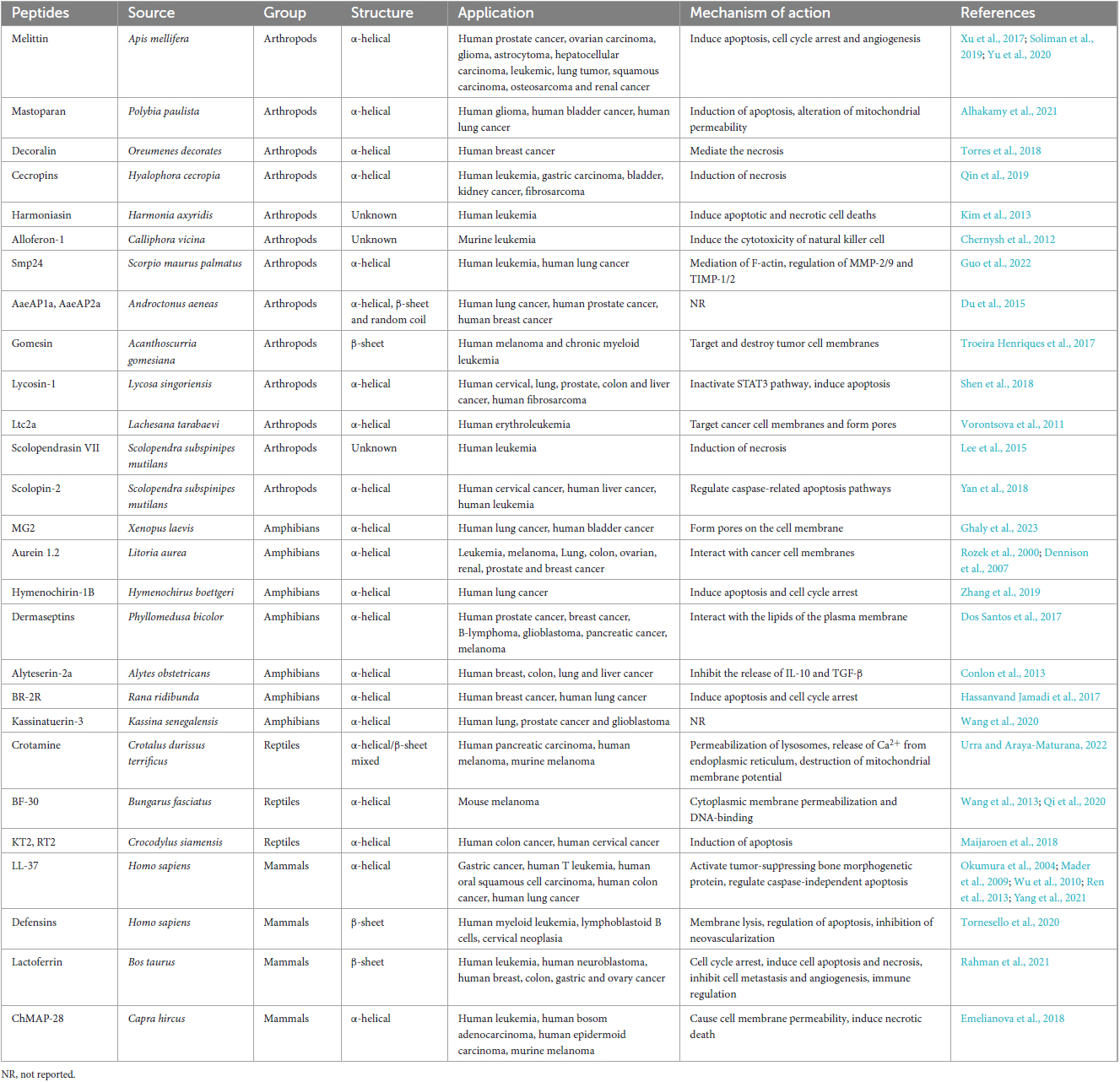

Table 2. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) with potential anticancer activity derived from terrestrial animals, their application and mechanisms of action.

3.1 ACPs isolated from marine animals

3.1.1 ACPs derived from sponges

Sponges are filter-feeding animals that cope with hazardous particles by producing neutralizing bioactive compounds such as peptides. In the past 20 years, researchers have focused on sponges-isolated peptides such as jaspamide, koshikamides, and theonellamide G, which exhibited extensive cytotoxicity to various cancer cells. These peptides with unusual amino acids or non-amino acid parts compared to other animal derived ACPs. Jaspamide and koshikamides were the special structured cyclic depsipeptides found in the genus Jaspis johnstoni and the Theonella sp. respectively, exhibiting cytotoxicity to various cancer cells, like prostate, breast carcinomas, acute myeloid leukemia and colon cancer cells (Schweikart et al., 2013; Kang et al., 2018). Whereas, theonellamide G is a glycopeptide, obtained from the Theonella swinhoei, exhibiting cytotoxic effects against HCT-16 human colon adenocarcinoma cell line (Macedo et al., 2021).

3.1.2 ACPs derived from marine mollusks

Marine mollusks rely on their physical barriers and innate immune systems to resist the most diverse pathogens, due to the adaptive immunity has not yet evolved. Since the 1990s, a few marine mollusks ACPs have been identified. Dolastatin 10 was the first marine mollusk ACP identified from the Indian Ocean sea hare Dolabella Auricularia (Bai et al., 1990), and is still considered one of the most powerful anti-cancer peptides found so far. It could inhibit the proliferation of human lymphoma, lung cancer, ovarian carcinoma, prostate cancer, soft tissue sarcoma, breast cancer and pancreatic cancer by inhibiting microtubule assembly and tubulin polymerization, and inducing apoptosis and Bcl-2 phosphorylation (Gao et al., 2021). Adcetris® is an ADC drug modified from dolastatin 10, containing a CD30-specific mAb conjugated to monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE). It was approved by FDA in 2011 and became the second ADC drug to enter the oncology market (Tong et al., 2021).

3.1.3 ACPs derived from marine arthropods

Arthropods are one of the most successful animals in adapting and surviving in the marine environment, not only due to their solid shells but also because of their complete inner immunity compared to other marine animals. AMPs play a vital in the immune system. Currently, various AMPs that have been proven as ACPs in marine arthropods are mainly concentrated in shrimps and crabs. For example, shrimp anti-lipopolysaccharide factor (SALF) displayed antitumor activity against Hela cells by apoptosis related death receptor/NF-κB signaling pathway. When combined with cisplatin, the inhibitory effect on Hela cells is more pronounced (Lin et al., 2010). The novel ACPs polyphemusins from the horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus were discovered to against human cancer cells. In an anti-tumor research, polyphemusin II was examined to destroy the cell membranes of the human erythroleukemia K562 cell line by inducing necrotic cell death (Paredes-Gamero et al., 2012). Another study indicated that polyphemusin III could lead to rapid permeabilization of the cytoplasmic membrane of human leukemia cells HL-60 (Marggraf et al., 2018).

3.1.4 ACPs derived from marine ascidians

Ascidians belong to the phylum of Chordata and are the most evolved group of marine organisms. Unique cyclic and linear peptides containing unusual amino acids derived from ascidians have increased our knowledge regarding novel ACPs. Styelin D, an ACP with 32 residues containing two specific amino acids (dihydroxyarginine and dihydroxylysine) from blood cells of the ascidian Styela clava, showed significant cytotoxic and hemolytic to human cervical cancer epithelial cell line ME-180 (Taylor et al., 2000). Moreover, turgencin A and turgencin B with six cysteine residues are two novel linear ACPs, derived from the ascidian Synoicum turgens, which showed obvious anticancer activities to suppress the proliferation of melanoma cancer cell line A2058 and the human fibroblast cell line MRC-5 (Hansen et al., 2020).

3.1.5 ACPs derived from fish

Bioactive peptides are indispensable components of fish innate immune system, to prevent the invasion of pathogens from the aquatic microorganisms ecosystems. Fish ACPs mainly identified from the fish mucus, among them, pardaxin, piscidin, and epinecidin-1 are the representative beings. Pardaxin is the most widely studied ACP present in the Red Sea Moses sole (Pardachirus marmoratus). It is composed of α-helix with 33 amino acid residues and has been experimentally confirmed in several studies on different cancer cell lines to show anticancer potential through multiple mechanisms of action. For example, pardaxin could arrest the cell cycle of cancer cells in the G2/M phase, thereby interfering with the cell proliferation process (Eghtedari et al., 2021). Moreover, pardaxin has been researched for its antitumor properties via inducing apoptotic cell death in various cancer cell lines such as fibrosarcoma (Wu et al., 2012), oral squamous carcinoma (Han et al., 2015), ovarian cancer cells (Chen et al., 2021) and cervical carcinoma (Huang and Chen, 2013). Besides that, pardaxin was also demonstrated to cause cell necrosis in fibrosarcoma (Lin et al., 2013) and autophagy in ovarian cancer cells (Chen et al., 2021). Furthermore, it is particularly noteworthy that the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-targeting ability of pardaxin in cancer cells (Qin et al., 2020). The piscidin family is an important component of the innate immunity of teleost, and recent studies have shown that they have extensive antibacterial and anticancer activities. A study reported that piscidin-1 could inhibit the motility and proliferation of HT1080 (human fibrosarcoma cell line) via inducing apoptotic and necrotic activity (Lin et al., 2012). Another study observed that piscidin-4 displayed significant cytotoxicity toward non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines such as A549, NCI-H661, NCI-H1975 and HCC827 (Ting and Chen, 2018). In this research, piscidin-4 caused NSCLC cell death through the necrotic pathway rather than the apoptotic pathway. Another common peptide was epinecidin-1, a naturally occurring peptide isolated from orange-spotted grouper (Epinephelus coioides), which exhibited inhibitory activity on human lung cancer and glioblastoma by regulating the process of cell apoptosis and necrosis (Su et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2023).

3.2 ACPs isolated from terrestrial animals

3.2.1 ACPs derived from terrestrial arthropods

Terrestrial arthropods are rich sources of novel bioactive compounds, including ACPs, which are mainly derived from three main classes: Insecta, Arachnida, and Chilopoda.

Insect AMPs are critical factors of the insect immune system, and also show toxic effects on many cancer cells (Table 2). Bee venom is a kind of important insect-derived AMPs with anti-tumor effects. Melittin is an amphiphilic bioactive peptide derived from the honey bee Apis mellifera and is the most researched and representative bee venom-derived AMP. Melittin induced a variety of cell death mechanisms, such as apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and angiogenesis (Soliman et al., 2019). Experimental studies have proven that melittin exhibited anticancer activity in prostate cancer, ovarian carcinoma, glioma, astrocytoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, leukemic, lung tumor, squamous carcinoma, osteosarcoma and renal cancer cells (Xu et al., 2017; Soliman et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2020). However, the use and application of melittin in clinical experiments was limited because of its widespread cytotoxicity against both tumor cells and normal cells. Therefore, the recent research hotspots of melittin mainly focused on developing safe and stable melittin delivery systems (Wang A. et al., 2022). In addition, A classic AMP from silkworms is cecropin, which was considered as a necrosis-inducing peptide and exhibited anti-proliferation activity to leukemia cells, gastric carcinoma, bladder cancer, fibrosarcoma and HCC (Qin et al., 2019).

The ACPs in Arachnida are mainly concentrated in the venom of scorpions and spiders (Table 2). Smp24, a cationic AMP isolated from the venom gland of the Egyptian scorpion Scorpio maurus palmatus, has been proven to show potent suppressing effects on leukemic tumor cell lines (KG1-a and CCRF-CEM) and human lung cancer cell lines (A549, H3122, PC-9, and H460). Furthermore, its inhibition of the A549 cell migration ability is through the mediation of filamentous actin (F-actin) and the changes of MMP-2/9 and TIMP-1/2 protein expressions (Guo et al., 2022). Spider AMPs with anti-cancer activities have also been reviewed. Spider venom-derived peptide lycosin-1 was proven to inhibit seven cancer cell lines proliferation in vitro and effectively suppressed tumor growth in vivo. Mechanistically, it mediated the mitochondrial death pathway, making cancer cells sensitive to apoptosis, and inactivated the STAT3 pathway (Shen et al., 2018).

Centipedes are typical venomous arthropods. Lee et al. (2015) reported an ACP isolated from the Centipede, Scolopendra subspinipes mutilans called scolopendrasin VII. The results showed that scolopendrasin VII reduced the viability of the leukemia cells by inducing necrosis. Scolopin-2, a cationic AMP from centipede venoms, displayed anti-proliferation activities to tumor cell lines such as HeLa, HepG2 and K562 and did not show toxic side effects on normal cells (Yan et al., 2018).

3.2.2 ACPs derived from amphibians

The skin secretions of amphibians are composed of various bioactive peptides, and hundreds of skin AMPs have been isolated from frogs and toads (Oelkrug et al., 2015), some of which also exhibited selective cytotoxicity against cancer cells (Conlon et al., 2014). For example, MG2, isolated from Xenopus laevis skin, has demonstrated antitumor activity against human lung cancer and bladder cancer via forming pores on the cell membrane (Ghaly et al., 2023). Aurein 1.2 is a peptide found in the frog Litoria aurea, which was reported to exhibit high activity against 55 different cancer cell lines in vitro (Rozek et al., 2000; Dennison et al., 2007). Furthermore, hymenochirin-1B is a cationic α-helix peptide belonging to the hymenochirin family from the frog Hymenochirus boettgeri, and has been reported to exert antineoplastic activities against lung cancer cells NCI-H1299 and A549 by inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest through the mitochondrial pathway (Zhang et al., 2019). Additionally, many other ACPs from amphibians and their mechanisms of action are summarized in Table 2.

3.2.3 ACPs derived from reptiles

Reptile-derived ACPs mainly from the venom of snakes. Crotamine is one of the main peptides of the venom of the South American rattlesnake Crotalus durissus terrificus. It acted on the permeabilization of lysosomes, the release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum and the destruction of mitochondrial membrane potential (Urra and Araya-Maturana, 2022), then showed cytotoxicity toward various cancer cells, such as human pancreatic carcinoma cells Mia PaCa-2, human melanoma cells SK-Mel-28 and murine melanoma cells B16-F10. Another remarkable ACP containing 30 amino acids named cathelicidin-BF (BF-30) was found in the snake Bungarus fasciatus. In a study, BF-30 suppressed the growth of mouse melanoma cell B16F10 in a dose and time-dependent manner. In vivo experiments, BF-30 obviously inhibited melanoma development in B16F10 tumor-bearing mice without adverse reactions occurring (Wang et al., 2013). In addition, Qi et al. (2020) designed a BF-30 derivative, LBF-14, which exhibited significant anti-melanoma action through disrupting the cell membrane, and then binding to the genomic DNA to suppress the migration and angiogenesis of melanoma cells.

3.2.4 ACPs derived from mammals

Several representative ACPs in mammals have been extensively studied (Table 2). Among them, three of the peptides that have been extensively studied are LL-37, defensins, and lactoferricin. The human cathelicidin, LL-37, participated in the killing process of various tumor cells. For example, Wu et al. (2010) indicated that LL-37 showed cytotoxicity to gastric cancer cells by activating tumor-suppressing bone morphogenetic protein signaling via suppression of proteasome. LL-37 could also inhibit the growth of Jurkat human T leukemia cells, human oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells SAS-H1 and colon cancer cells via caspase-independent apoptosis (Okumura et al., 2004; Mader et al., 2009; Ren et al., 2013). Importantly, LL-37 has been modified to many shorter sequences to exhibit lower toxicity and higher efficiency. 17BIPHE2, the shortest modified LL-37, could induce apoptosis of human lung cancer better than LL-37 (Yang et al., 2021). Defensins, an important group of cysteine-rich and β-sheet AMPs widely presented in various mammals, have been discovered to display cytolytic activity against several cancer cell lines, such as human myeloid leukemia cell line U937, K562, lymphoblastoid B cells IM-9 and WIL-2 and cervical neoplasia. Furthermore, the anti-cancer activities of α-defensins, including the human neutrophil peptides (HNP) 1–3, have been proven through the manner of membrane lysis and apoptosis as well as inhibition of neovascularization in tumor cells (Tornesello et al., 2020). Lactoferricin is a cationic peptide identified from the acid-pepsin hydrolysis of lactoferrin in mammalian milk and exhibited cytotoxic activity against a panel of microorganisms and cancer cells. Lactoferricin mainly exerted anti-tumor effects through cell cycle arrest, inducing cell apoptosis and necrosis, inhibiting cancer cell metastasis and angiogenesis, and immune regulation (Rahman et al., 2021).

4 Mechanisms of AMPs underlying their anti-cancer effects

Due to the non-specific destruction of the plasma membrane by ACPs, they exhibit therapeutic potential for tumors that are ineffective in traditional drug therapy. Although some of the main mechanisms of action have been reported, the exact mechanisms of the toxic effect of ACPs on cancer cells remain controversial. Generally speaking, the anti-cancer effect of bioactive peptides can be achieved by regulating membrane or non-membrane mechanisms (Harris et al., 2013).

4.1 Membranes disruptive mechanisms

As mentioned in the section “2 The structural classifications and selective recognition to tumor cells of AMPs” of this article, the destruction modes of ACPs on tumor cell membranes is similar to that of AMPs induced bacterial membrane damage (Figure 2). For example, a study reported by Papo et al. (2006) indicated that a short host defense-like peptide could selectively recognize cancer cells mainly via binding with negatively charged PS on the cell surface, leading to depolarization of cell plasma membrane and cell death. Therefore, peptide-lipid interaction is the committed step to effectively destroy tumor cell membranes. Another research also demonstrated that the spider venom Ltc2a could induce tumor cell membrane blebbing, swelling, and ultimately cell death. Interestingly, this peptide interacted with the outer membrane leaflet of tumor cells, thereby inducing PS externalization. Due to the formation of membrane pores in tumor cells, their permeability to anionic molecules is stronger than that of cationic molecules, and the redistribution of PS toward the outer leaflet of the membrane was discovered in the tumor cells (Vorontsova et al., 2011). Moreover, several ACPs such as cecropins, pardaxin, magainins and melittin were proven that they induce the formation of pores in tumor cell membranes through the barrel-stave model, toroidal model and carpet model, and lead to tumor lysis and death (Ryan et al., 2013; Han et al., 2015; Kashiwada et al., 2016; Pino-Angeles et al., 2016; Zhang S. K. et al., 2016).

Figure 2. Different anticancer mechanisms of ACPs. ACPs can function through a variety of mechanisms, including induction of tumor apoptosis, regulation of tumor necrosis, suppression of tumor angiogenesis, mediation of immunity and regulation of intracellular signaling pathways.

4.2 Non-membranes disruptive mechanisms

4.2.1 Induction of tumor apoptosis

Apoptosis is a gene-directed program developed by multicellular organisms to control cell proliferation to cope with DNA damage during development or after cell stress. The characteristics of the apoptosis process are cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation and then small membrane-bound apoptotic bodies are released and swallowed by macrophages or adjacent cells. There are two major pathways of apoptosis in mammalian cells: mitochondrial-mediated endogenous pathways and death receptor-mediated exogenous pathways. In the mitochondrial-mediated endogenous pathways of apoptosis, cell apoptosis is caused by mitochondrial dysfunction and membrane damage, resulting the release of the Cytc. The Cytc-induced apoptosis is mainly initiated by the apoptotic protease (Caspase) pathway (Dave et al., 2011). The early opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) in the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) is a key reason in primary necrosis. These changes lead to extreme swelling of mitochondrial permeability, ultimately resulting in necrotic cell death (Mulder et al., 2013). In the death receptor pathway, various external factors act as promoters of cell apoptosis, and then transmit apoptotic signals through different signal transduction systems, inducing cell apoptosis. Fas and Fas ligand (FasL/CD95L) are the two most important apoptosis-inducing molecules in cancer cells (Shimoyama et al., 2015). Cell apoptosis plays a vital role in eliminating cancer cells without causing damage to normal cells or surrounding tissues. Regulating the apoptosis pathway in tumor cells will be an effective method for cancer prevention and treatment, and peptides that can induce tumor cell apoptosis (Figure 2) are gradually becoming significant candidates for the development of novel anticancer medicines. Ceremuga et al. (2020) found a dose dependent decrease of mitochondrial membrane potential in human leukemia cells treated with melittin, which confirmed the process of cell apoptosis and suggested a potential pathway related to the intrinsic mechanism that depended on mitochondria. A study in 2022 demonstrated that NRC-03 could induce apoptosis in OSCC cells through the cyclophilin D (CypD)-mPTP axis mediated mitochondrial oxidative stress (Hou et al., 2022). In terms of exogenous pathways mediated by death receptors, SALF is a typical peptide that exerted anti-tumor effects through the apoptosis-related death receptor/NF-κB signaling pathway (Lin et al., 2010). Moreover, in recent years, researchers have also found that both endogenous and exogenous apoptosis pathways were involved in ACPs induced cancer cell apoptosis. For example, MSP-4 could induce apoptosis via activation of extrinsic Fas/FasL- and intrinsic mitochondria-mediated pathways in the osteosarcoma cell line (Kuo et al., 2018). In another study, the expression of the cell apoptosis key proteins, such as Cytc, caspase-9, and caspase-3 in the endogenous mitochondrial pathway, and Fas, FasL in the exogenous death receptor pathway were significantly up-regulated after treating lung cancer cells with dermaseptin (Dong et al., 2020). In addition, Ju and co-workers found that both the caspases mediating extrinsic and mitochondria intrinsic pathways were activated in Brevinin-1RL1 induced apoptosis (Ju et al., 2021).

4.2.2 Regulation of tumor necrosis

Necrosis is defined as an unexpected, uncontrolled, and non-programmed form of cell death. Accidental necrosis is usually caused by chemical or physical damage, ultimately leading to chromatin flocculation, swelling and degeneration of the cytoplasm and the mitochondrial matrix, blebbing of the cellular membrane, and overflow of cytoplasm contents to the outside of cells (Padanilam, 2003). Necrosis inducing peptides are a group of lytic peptides that destroy cell membranes (Figure 2). Compared with traditional chemotherapy drugs, they have higher selectivity toward cancer cells and do not induce multidrug resistance, making them a promising new class of anticancer drugs (Bhutia and Maiti, 2008). For instance, Su et al. (2019) found that piscidin 4 displayed anti-tumor activity on glioblastoma cell lines via inducing mitochondrial hyperpolarization and mitochondrial dysfunction, followed by DNA damage and necrosis. A study in 2019 revealed that melittin induced cell death mostly occurred by necrosis in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells (Daniluk et al., 2019). Moreover, it was reported that decoralin could induce necrosis in cancer cells by enhancing the stiffness of the cell membrane (Mirzaei et al., 2021). It was also pointed out that cathelicidin reduced the tumor growth and regulated necrosis of cancer cells by releasing tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and granules enzymes (Mahmoud et al., 2022). Furthermore, Smp24 could induce necrosis of A549 cells through damaging the integrity of the cell membrane, mitochondrial and nuclear membranes (Guo et al., 2022).

4.2.3 Suppression of tumor angiogenesis

Angiogenesis is the process through which novel blood vessels are formed from pre-existing ones and it is a multi-step process involving endothelial cell (EC) proliferation and migration (Starzec et al., 2006). Angiogenesis plays an important role in the growth, invasion, and metastasis of tumors. Specifically, nutrition, oxygen supply, and metabolic waste excretion in tumors are regulated through a complex network of tumor microvessels (De Palma et al., 2017). Tumor angiogenesis is completed via a range of sequential steps, which further result in the development of cancer. The process of angiogenesis is mainly triggered by the tumor itself, and as malignant tumors continue to grow, tumor cells become hypoxic (Marme, 2018). Hypoxia is the basic initiating factor for tumor angiogenesis (De Palma et al., 2017). Moreover, there are many growth factors involved in tumor angiogenesis, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), angiogenin (Ang), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), TNF-α and placental growth factor (PLGF) (Al-Ostoot et al., 2021). Therefore, inhibiting angiogenesis is an effective way to hinder tumor development. Many bioactive peptides exert effective anti-angiogenic and anti-cancer effects mainly by blocking the interaction between growth factors and their receptors (Figure 2). For example, Zhang Z. et al. (2016) pointed out that melittin was capable of suppressing cathepsin S-induced angiogenesis by blocking of the VEGF-A/VEGFR-2/mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (MEK1)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (Erk1/2) signaling pathway. Moreover, it has been proved that lactoferrin could reduce the growth of blood vessels in colon cancer cells and the mechanism was validated to be associated with the inhibition of angiogenesis related pathways, including VEGFR2, vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), PI3K, Akt, and Erk1/2 (Li et al., 2017). Another study indicated that the downregulation of FGFR1 was an indication of the novel anti-angiogenic activity of dermaseptins in rhabdomyosarcoma cells (Abdille et al., 2021).

4.2.4 Mediation of immunity

Malignant tumor cells recruit multiple cell types through generating cytokines and growth factors, such as endothelial cells, inflammatory immune cells, and fibroblasts (Liotta and Kohn, 2001). These different types of cells and extracellular matrix molecules constitute the tumor microenvironment (Devaud et al., 2013). Inflammatory reactions are involved in various biological processes (Medzhitov, 2008; Wang P. et al., 2022). In the tumor microenvironment, there is a delicate balance between anti-tumor immunity and tumor-derived proinflammatory activity, which limits the progress of anti-tumor immunity (Murugaiyan and Saha, 2013). Many peptides display cytotoxicity against tumor cells by activating the human immune system, thereby achieving the goal of curing cancer (Figure 2). Research has shown that both alloferon-1 and alloferon-2 could induce the cytotoxicity of natural killer cells in mammals, such as mice and humans. In a mouse tumor transplantation model, alloferon-1 monotherapy showed moderate tumor suppression comparable to low-dose chemotherapy (Chernysh et al., 2012). Another study indicated that lactoferrin could up-regulate the components of non-specific immunity against cancer, including interferon-γ (IFN-γ), caspase-1 and interleukin-18 (IL-18). When interacting with danger associated molecules (DAMPs) derived from cancer cells, membrane components of innate immunity, such as pattern recognition receptor (PRR), trigger a response of inflammasomes, resulting in activation of caspase-1, which cleaves pro-IL18 and produces IL-18. IL-18 is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine that acts as an IFN-γ-inducer factor in NK and T cells with effector cell lysis activity on cancer cells (Cui et al., 2014). Additionally, Tang et al. (2022) designed a tumor microenvironment (TME) responsive MnO2-melittin nanoparticles (M-M NPs). The M-M NPs could activate cGAS-STING pathway and promote the maturation of antigen-presenting cells to initiate systemic anti-tumor immune response such as increasing the production of tumor-specific T cells and more pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.

4.2.5 Regulation of other intracellular signaling pathways

A more possible mechanism of cancer cell growth inhibitory activity of AMPs is associated with modulating various cell regulatory/signaling pathways intracellularly (Figure 2). Janmaat and others have demonstrated that kahalalide F exerted cytotoxic activity on cancer cells by regulating ErbB3 and the downstream PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (Janmaat et al., 2005). Another study mentioned that melittin suppressed the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, leading to an inhibition of EGF-induced breast cancer cell migration and invasion (Jeong et al., 2014). A report of Uen et al. (2019) found that pardaxin exhibited anti-cancer activity to leukemic cells via regulating toll-like receptor (TLR2)/MyD88 signaling pathway. Specifically, padaxin induced leukemia cells to differentiate into macrophages like cells with immunostimulatory functions, including phagocytic ability and production of superoxide anions, by activating MyD88 protein. Furthermore, cecropin A has been shown to down-regulate MEK/ERK phosphorylation. The MAPK/ERK signaling pathway is responsible for the regulation of cell division, cell cycle or transcription regulation in cancer cells (Zhai et al., 2019). A recent study in 2022 confirmed that melittin could inhibit the growth of osteosarcoma 143B cells, which was associated with the supression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway activity and cause apoptosis through up-regulating the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 (Xie et al., 2022).

5 Clinical applications of ACPs

Although significant progress has been made in the treatment and prevention of various cancers, one of the main issues with cancer therapies is heavy side effects. In contrast, the ACP agents exhibit cytotoxicity against cancer cells at low concentrations without toxicity to normal tissues and therefore provide new strategies for cancer treatment. In addition, the peptides also have characteristics such as small size, simple synthesis, ability to enter the cell layer, high specificity and affinity, and lower immunogenicity than chemotherapy drugs (Eghtedari et al., 2021). At last, another advantage of using peptides as therapy is that they do not accumulate in the kidney or liver, which greatly limits their toxic reactions (Marqus et al., 2017).

Several peptide anti-tumor drugs have been completed or are currently undergoing clinical trials. For instance, balixafortide is based on polyphemusin, a natural peptide from the crab. The completed results of phase I and II trials have shown that the combination of balixafortide and ibuprofen enhanced the anti-tumor effect of HER2 negative metastatic breast cancer patients and improved tolerance compared to ibuprofen alone, without producing dose limiting toxicities (Pernas et al., 2018). The blockade of the C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) pathway by balixafortide played a crucial role in inhibiting metastasis and diffusion, making tumor cells sensitive to chemotherapy, and activating the immune system in the TME. Therefore, balixafortide may show great potential for its forthcoming phase III trial (NCT03786094). LL-37 is the most studied human ACP and the completed clinical trial (NCT02225366) in 2021 evaluated the appropriate dose of LL-37 for intratumoral administration in melanoma patients (Jafari et al., 2022). Another ACP called LTX-315, a lactoferrin-derived lytic peptide, is currently undergoing a phase I multicenter study (NCT01058616) to evaluate its therapeutic efficacy against various types of transdermal accessible tumors.

In the past few decades, the USFDA has approved several ACP drugs. For example, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analog leuprolide acetate (Lupron®) was used to treat prostate cancer in 1990. It possessed immunomodulatory effects including reduction of the production of TNF-α, IL-1β and other inflammatory cytokines to exert anti-cancer function (Guzmán-Soto et al., 2016). Adcetris® is an ADC drug developed based on dolastatin 10 for the treatment of lymphoma, which was launched in 2011 and successfully overcame obstacles in the clinical application of dolastatin 10 as a single drug. Before Adcetris® was developed, dolastatin 10 failed in phase II clinical trial owing to adverse reactions such as hematological and vascular toxicities (von Mehren et al., 2004). Subsequently, researchers used ADC technology to couple monoclonal antibodies with dolastatin 10 derivatives and utilized the specificity of antibodies to transport drugs to target tissues for their anti-cancer functions. At last, Adcetris® effectively reduced the systemic toxicity and side effects.

6 Conclusion

Terrestrial and marine animals contain abundant bioactive peptides that have been successfully developed and have achieved good therapeutic effects, such as antioxidant, antibacterial, anticancer, immune regulation, etc. In this review, we summarized the main animal-origin ACPs according to the animal’s evolution order and their anti-tumor mechanisms that have been reported in the past decades. Comprehensively, ACPs exert anti-cancer activity through membrane disruptive and non-membrane disruptive mechanisms including mediation of the necrosis or apoptosis of cancer cells, inhibition of angiogenesis, recruitment of immune cells and activation of certain regulatory functional proteins. Then we reviewed the clinical applications of ACPs. Encouragingly, an increasing number of peptide anti-tumor drugs have been approved for commercialization by the USFDA or undergoing clinical trials. In all, we expect that, with the accumulation of ACPs conducted in clinical trials in the future, ACPs could become one of the novel choices for the clinical treatment of cancers.

Author contributions

BQ: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. JY: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. XL: Methodology, Writing – original draft. SZ: Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review and editing. XM: Writing – review and editing. LL: Project administration, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Shandong Province Medical and Health Technology Development Plan Project (202203100062) and Qingdao Medical and Health Research Guidance Project (2022-WJZD100).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Abdille, A. A., Kimani, J., Wamunyokoli, F., Bulimo, W., Gavamukulya, Y., and Maina, E. N. (2021). Dermaseptin B2’s anti-proliferative activity and down regulation of anti-proliferative, angiogenic and metastatic genes in rhabdomyosarcoma RD cells in vitro. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 12, 337–359. doi: 10.4236/abb.2021.1210022

Alhakamy, N. A., Ahmed, O. A. A., Md, S., and Fahmy, U. A. (2021). Mastoparan, a peptide toxin from wasp venom conjugated fluvastatin nanocomplex for suppression of lung cancer cell growth. Polymers (Basel) 13:4225. doi: 10.3390/polym13234225

Al-Ostoot, F. H., Salah, S., Khamees, H. A., and Khanum, S. A. (2021). Tumor angiogenesis: current challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 28:100422. doi: 10.1016/j.ctarc.2021.100422

Anju, A., Smitha, C. K., Preetha, K., Boobal, R., and Rosamma, P. (2019). Molecular characterization, recombinant expression and bioactivity profile of an antimicrobial peptide, Ss-arasin from the Indian mud crab, Scylla serrata. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 88, 352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.03.007

Asasira, J., Lee, S., Tran, T. X. M., Mpamani, C., Wabinga, H., Jung, S. Y., et al. (2022). Infection-related and lifestyle-related cancer burden in Kampala, Uganda: projection of the future cancer incidence up to 2030. BMJ Open 12:e056722. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056722

Bai, R., Pettit, G. R., and Hamel, E. (1990). Dolastatin 10, a powerful cytostatic peptide derived from a marine animal. inhibition of tubulin polymerization mediated through the vinca alkaloid binding domain. Biochem. Pharmacol. 39, 1941–1949. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90613-p

Bhutia, S. K., and Maiti, T. K. (2008). Targeting tumors with peptides from natural sources. Trends Biotechnol. 26, 210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.01.002

Ceremuga, M., Stela, M., Janik, E., Gorniak, L., Synowiec, E., Sliwinski, T., et al. (2020). Melittin-A natural peptide from bee venom which induces apoptosis in human leukaemia cells. Biomolecules 10:247. doi: 10.3390/biom10020247

Chakniramol, S., Wierschem, A., Cho, M. G., and Bashir, K. M. I. (2022). Physiological and clinical aspects of bioactive peptides from marine animals. Antioxidants (Basel) 11:1021. doi: 10.3390/antiox11051021

Chen, J., Xu, X. M., Underhill, C. B., Yang, S., Wang, L., Chen, Y., et al. (2005). Tachyplesin activates the classic complement pathway to kill tumor cells. Cancer Res. 65, 4614–4622. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2253

Chen, Y. P., Shih, P. C., Feng, C. W., Wu, C. C., Tsui, K. H., Lin, Y. H., et al. (2021). Pardaxin activates excessive mitophagy and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in human ovarian cancer by inducing reactive oxygen species. Antioxidants (Basel) 10:1883. doi: 10.3390/antiox10121883

Chernysh, S., Irina, K., and Irina, A. (2012). Anti-tumor activity of immunomodulatory peptide alloferon-1 in mouse tumor transplantation model. Int. Immunopharmacol. 12, 312–314. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.10.016

Chiangjong, W., Chutipongtanate, S., and Hongeng, S. (2020). Anticancer peptide: physicochemical property, functional aspect and trend in clinical application (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 57, 678–696. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2020.5099

Conlon, J. M., Mechkarska, M., Lukic, M. L., and Flatt, P. R. (2014). Potential therapeutic applications of multifunctional host-defense peptides from frog skin as anti-cancer, anti-viral, immunomodulatory, and anti-diabetic agents. Peptides 57, 67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.04.019

Conlon, J. M., Mechkarska, M., Prajeep, M., Arafat, K., Zaric, M., Lukic, M. L., et al. (2013). Transformation of the naturally occurring frog skin peptide, alyteserin-2a into a potent, non-toxic anti-cancer agent. Amino Acids 44, 715–723. doi: 10.1007/s00726-012-1395-7

Costa, F., Carvalho, I. F., Montelaro, R. C., Gomes, P., and Martins, M. C. (2011). Covalent immobilization of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) onto biomaterial surfaces. Acta Biomater. 7, 1431–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.11.005

Cui, J., Chen, Y., Wang, H. Y., and Wang, R. F. (2014). Mechanisms and pathways of innate immune activation and regulation in health and cancer. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 10, 3270–3285. doi: 10.4161/21645515.2014.979640

Daniluk, K., Kutwin, M., Grodzik, M., Wierzbicki, M., Strojny, B., Szczepaniak, J., et al. (2019). Use of selected carbon nanoparticles as melittin carriers for MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. Materials (Basel) 13:90. doi: 10.3390/ma13010090

Dave, K. R., Bhattacharya, S. K., Isabel, S. R., Anthony, D., Cameron, D., Lin, H. W., et al. (2011). Activation of protein kinase C delta following cerebral ischemia leads to release of cytochrome C from the mitochondria via bad pathway. PLoS One 6:e22057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022057

De Palma, M., Biziato, D., and Petrova, T. V. (2017). Microenvironmental regulation of tumour angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 17, 457–474. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.51

Dennison, S. R., Harris, F., and Phoenix, D. A. (2007). The interactions of aurein 1.2 with cancer cell membranes. Biophys. Chem. 127, 78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.12.009

Deo, S. V. S., Sharma, J., and Kumar, S. (2022). GLOBOCAN 2020 report on global cancer burden: challenges and opportunities for surgical oncologists. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 29, 6497–6500. doi: 10.1245/s10434-022-12151-6

Devaud, C., John, L. B., Westwood, J. A., Darcy, P. K., and Kershaw, M. H. (2013). Immune modulation of the tumor microenvironment for enhancing cancer immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2:e25961. doi: 10.4161/onci.25961

Dias Rde, O., and Franco, O. L. (2015). Cysteine-stabilized alphabeta defensins: from a common fold to antibacterial activity. Peptides 72, 64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2015.04.017

Dong, Z., Hu, H., Yu, X., Tan, L., Ma, C., Xi, X., et al. (2020). Novel frog skin-derived peptide dermaseptin-PP for lung cancer treatment: in vitro/vivo evaluation and anti-tumor mechanisms study. Front. Chem. 8:476. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00476

Dos Santos, C., Hamadat, S., Le Saux, K., Newton, C., Mazouni, M., Zargarian, L., et al. (2017). Studies of the antitumor mechanism of action of dermaseptin B2, a multifunctional cationic antimicrobial peptide, reveal a partial implication of cell surface glycosaminoglycans. PLoS One 12:e0182926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182926

Du, Q., Hou, X., Wang, L., Zhang, Y., Xi, X., Wang, H., et al. (2015). AaeAP1 and AaeAP2: novel antimicrobial peptides from the venom of the scorpion, Androctonus aeneas: structural characterisation, molecular cloning of biosynthetic precursor-encoding cDNAs and engineering of analogues with enhanced antimicrobial and anticancer activities. Toxins (Basel) 7, 219–237. doi: 10.3390/toxins7020219

Duffy, C., Sorolla, A., Wang, E., Golden, E., Woodward, E., Davern, K., et al. (2020). Honeybee venom and melittin suppress growth factor receptor activation in HER2-enriched and triple-negative breast cancer. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 4:24. doi: 10.1038/s41698-020-00129-0

Eghtedari, M., Jafari Porzani, S., and Nowruzi, B. (2021). Anticancer potential of natural peptides from terrestrial and marine environments: a review. Phytochem. Lett. 42, 87–103. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2021.02.008

Emelianova, A. A., Kuzmin, D. V., Panteleev, P. V., Sorokin, M., Buzdin, A. A., and Ovchinnikova, T. V. (2018). Anticancer activity of the goat antimicrobial peptide ChMAP-28. Front. Pharmacol. 9:1501. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01501

Erdem Büyükkiraz, M., and Kesmen, Z. (2022). Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs): a promising class of antimicrobial compounds. J. Appl. Microbiol. 132, 1573–1596. doi: 10.1111/jam.15314

Fang, Z., Meng, Q., Xu, J., Wang, W., Zhang, B., Liu, J., et al. (2023). Signaling pathways in cancer-associated fibroblasts: recent advances and future perspectives. Cancer Commun. (Lond.) 43, 3–41. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12392

Ferlay, J., Ervik, M., Lam, F., Colombet, M., Mery, L., Piñeros, M., et al. (2020). Global cancer observatory: cancer today. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer.

Fuentes-Antrás, J., Genta, S., Vijenthira, A., and Siu, L. L. (2023). Antibody-drug conjugates: in search of partners of choice. Trends Cancer 9, 339–354. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2023.01.003

Gao, G., Wang, Y., Hua, H., Li, D., and Tang, C. (2021). Marine antitumor peptide dolastatin 10: biological activity, structural modification and synthetic chemistry. Mar. Drugs 19:363. doi: 10.3390/md19070363

Ghaly, G., Tallima, H., Dabbish, E., Badr ElDin, N., Abd El-Rahman, M. K., Ibrahim, M. A. A., et al. (2023). Anti-cancer peptides: status and future prospects. Molecules 28:1148. doi: 10.3390/molecules28031148

Guha, P., Kaptan, E., Bandyopadhyaya, G., Kaczanowska, S., Davila, E., Thompson, K., et al. (2013). Cod glycopeptide with picomolar affinity to galectin-3 suppresses T-cell apoptosis and prostate cancer metastasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 5052–5057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202653110

Guo, R., Liu, J., Chai, J., Gao, Y., Abdel-Rahman, M. A., and Xu, X. (2022). Scorpion peptide Smp24 exhibits a potent antitumor effect on human lung cancer cells by damaging the membrane and cytoskeleton in vivo and in vitro. Toxins (Basel) 14:438. doi: 10.3390/toxins14070438

Guzmán-Soto, I., Salinas, E., and Quintanar, J. L. (2016). Leuprolide acetate inhibits spinal cord inflammatory response in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by suppressing NF-κB activation. Neuroimmunomodulation 23, 33–40. doi: 10.1159/000438927

Haider, T., and Soni, V. (2022). Response surface methodology and artificial neural network-based modeling and optimization of phosphatidylserine targeted nanocarriers for effective treatment of cancer: in vitro and in silico studies. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 75:103663. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2022.103663

Han, H. H., Teng, D., Mao, R. Y., Hao, Y., Yang, N., Wang, Z. L., et al. (2021). Marine peptide-N6NH2 and its derivative-GUON6NH2 have potent antimicrobial activity against intracellular Edwardsiella tarda in vitro and in vivo. Front. Microbiol. 12:637427. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.637427

Han, Y., Cui, Z., Li, Y. H., Hsu, W. H., and Lee, B. H. (2015). In vitro and in vivo anticancer activity of pardaxin against proliferation and growth of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Mar. Drugs 14:2. doi: 10.3390/md14010002

Hansen, I. K. O., Isaksson, J., Poth, A. G., Hansen, K. O., Andersen, A. J. C., Richard, C. S. M., et al. (2020). Isolation and characterization of antimicrobial peptides with unusual disulfide connectivity from the colonial ascidian Synoicum turgens. Mar. Drugs 18:51. doi: 10.3390/md18010051

Harris, F., Dennison, S. R., Singh, J., and Phoenix, D. A. (2013). On the selectivity and efficacy of defense peptides with respect to cancer cells. Med. Res. Rev. 33, 190–234. doi: 10.1002/med.20252

Hassanvand Jamadi, R., Yaghoubi, H., and Sadeghizadeh, M. (2017). Brevinin-2R and derivatives as potential anticancer peptides: synthesis, purification, characterization and biological activities. Int. J. Peptide Res. Ther. 25, 151–160. doi: 10.1007/s10989-017-9656-7

Hilchie, A. L., Conrad, D. M., Coombs, M. R., Zemlak, T., Doucette, C. D., Liwski, R. S., et al. (2013). Pleurocidin-family cationic antimicrobial peptides mediate lysis of multiple myeloma cells and impair the growth of multiple myeloma xenografts. Leuk. Lymphoma 54, 2255–2262. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.770847

Hilchie, A. L., Doucette, C. D., Pinto, D. M., Patrzykat, A., Douglas, S., and Hoskin, D. W. (2011). Pleurocidin-family cationic antimicrobial peptides are cytolytic for breast carcinoma cells and prevent growth of tumor xenografts. Breast Cancer Res. 13:R102. doi: 10.1186/bcr3043

Hou, D., Hu, F., Mao, Y., Yan, L., Zhang, Y., Zheng, Z., et al. (2022). Cationic antimicrobial peptide NRC-03 induces oral squamous cell carcinoma cell apoptosis via CypD-mPTP axis-mediated mitochondrial oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 54:102355. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102355

Hsu, J. C., Lin, L. C., Tzen, J. T., and Chen, J. Y. (2011). Characteristics of the antitumor activities in tumor cells and modulation of the inflammatory response in RAW264.7 cells of a novel antimicrobial peptide, chrysophsin-1, from the red sea bream (Chrysophrys major). Peptides 32, 900–910. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.02.013

Huan, Y., Kong, Q., Mou, H., and Yi, H. (2020). Antimicrobial peptides: classification, design, application and research progress in multiple fields. Front. Microbiol. 11:582779. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.582779

Huang, T. C., and Chen, J. Y. (2013). Proteomic analysis reveals that pardaxin triggers apoptotic signaling pathways in human cervical carcinoma HeLa cells: cross talk among the UPR, c-Jun and ROS. Carcinogenesis 34, 1833–1842.

Ibrahim, S. R., Min, C. C., Teuscher, F., Ebel, R., Kakoschke, C., Lin, W., et al. (2010). Callyaerins A-F and H, new cytotoxic cyclic peptides from the Indonesian marine sponge Callyspongia aerizusa. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 18, 4947–4956. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.06.012

Jafari, A., Babajani, A., Sarrami Forooshani, R., Yazdani, M., and Rezaei-Tavirani, M. (2022). Clinical applications and anticancer effects of antimicrobial peptides: from bench to bedside. Front. Oncol. 12:819563. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.819563

Janmaat, M. L., Rodriguez, J. A., Jimeno, J., Kruyt, F. A., and Giaccone, G. (2005). Kahalalide F induces necrosis-like cell death that involves depletion of ErbB3 and inhibition of Akt signaling. Mol. Pharmacol. 68, 502–510. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.011361

Jeong, Y. J., Choi, Y., Shin, J. M., Cho, H. J., Kang, J. H., Park, K. K., et al. (2014). Melittin suppresses EGF-induced cell motility and invasion by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in breast cancer cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 68, 218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.03.022

Johansson, J., Gudmundsson, G. H., Rottenberg, M. E., Berndt, K. D., and Agerberth, B. (1998). Conformation-dependent antibacterial activity of the naturally occurring human peptide LL-37. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 3718–3724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3718

Ju, X., Fan, D., Kong, L., Yang, Q., Zhu, Y., Zhang, S., et al. (2021). Antimicrobial peptide brevinin-1RL1 from frog skin secretion induces apoptosis and necrosis of tumor cells. Molecules 26:2059. doi: 10.3390/molecules26072059

Kang, H. K., Choi, M. C., Seo, C. H., and Park, Y. (2018). Therapeutic properties and biological benefits of marine-derived anticancer peptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:919. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030919

Karami Fath, M., Babakhaniyan, K., Zokaei, M., Yaghoubian, A., Akbari, S., Khorsandi, M., et al. (2022). Anti-cancer peptide-based therapeutic strategies in solid tumors. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 27:33. doi: 10.1186/s11658-022-00332-w

Kashiwada, A., Mizuno, M., and Hashimoto, J. (2016). pH-dependent membrane lysis by using melittin-inspired designed peptides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 14, 6281–6288. doi: 10.1039/c6ob01002d

Kim, I. W., Lee, J. H., Kwon, Y. N., Yun, E. Y., Nam, S. H., Ahn, M. Y., et al. (2013). Anticancer activity of a synthetic peptide derived from harmoniasin, an antibacterial peptide from the ladybug Harmonia axyridis. Int. J. Oncol. 43, 622–628. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1973

Kuo, H. M., Tseng, C. C., Chen, N. F., Tai, M. H., Hung, H. C., Feng, C. W., et al. (2018). MSP-4, an antimicrobial peptide, induces apoptosis via activation of extrinsic Fas/FasL- and intrinsic mitochondria-mediated pathways in one osteosarcoma cell line. Mar. Drugs 16:8. doi: 10.3390/md16010008

Lath, A., Santal, A. R., Kaur, N., Kumari, P., and Singh, N. P. (2023). Anti-cancer peptides: their current trends in the development of peptide-based therapy and anti-tumor drugs. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 39, 45–84. doi: 10.1080/02648725.2022.2082157

Lee, J. H., Kim, I. W., Kim, S. H., Kim, M. A., Yun, E. Y., Nam, S. H., et al. (2015). Anticancer activity of the antimicrobial peptide scolopendrasin VII derived from the centipede, Scolopendra subspinipes mutilans. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 25, 1275–1280. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1503.03091

Lewies, A., Wentzel, J. F., Jacobs, G., and Du Plessis, L. H. (2015). The potential use of natural and structural analogues of antimicrobial peptides in the fight against neglected tropical diseases. Molecules 20, 15392–15433. doi: 10.3390/molecules200815392

Li, H. Y., Li, M., Luo, C. C., Wang, J. Q., and Zheng, N. (2017). Lactoferrin exerts antitumor effects by inhibiting angiogenesis in a HT29 human colon tumor model. J. Agric. Food Chem. 65, 10464–10472. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b03390

Li, M. S. C., Mok, K. K. S., and Mok, T. S. K. (2023). Developments in targeted therapy & immunotherapy-how non-small cell lung cancer management will change in the next decade: a narrative review. Ann. Transl. Med. 11:358. doi: 10.21037/atm-22-4444

Li, Q. F., Ou-Yang, G. L., Peng, X. X., and Hong, S. G. (2003). Effects of tachyplesin on the regulation of cell cycle in human hepatocarcinoma SMMC-7721 cells. World J. Gastroenterol. 9, 454–458. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i3.454

Li, S., Wang, Y., Xue, Z., Jia, Y., Li, R., He, C., et al. (2021). The structure-mechanism relationship and mode of actions of antimicrobial peptides: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 109, 103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.01.005

Liang, Y., Zhang, X., Yuan, Y., Bao, Y., and Xiong, M. (2020). Role and modulation of the secondary structure of antimicrobial peptides to improve selectivity. Biomater. Sci. 8, 6858–6866. doi: 10.1039/d0bm00801j

Lin, H. J., Huang, T. C., Muthusamy, S., Lee, J. F., Duann, Y. F., and Lin, C. H. (2012). Piscidin-1, an antimicrobial peptide from fish (hybrid striped bass morone saxatilis x M. chrysops), induces apoptotic and necrotic activity in HT1080 cells. Zoolog. Sci. 29, 327–332. doi: 10.2108/zsj.29.327

Lin, M. C., Hui, C. F., Chen, J. Y., and Wu, J. L. (2013). Truncated antimicrobial peptides from marine organisms retain anticancer activity and antibacterial activity against multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Peptides 44, 139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2013.04.004

Lin, M. C., Lin, S. B., Chen, J. C., Hui, C. F., and Chen, J. Y. (2010). Shrimp anti-lipopolysaccharide factor peptide enhances the antitumor activity of cisplatin in vitro and inhibits HeLa cells growth in nude mice. Peptides 31, 1019–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.02.023

Liotta, L. A., and Kohn, E. C. (2001). The microenvironment of the tumour-host interface. Nature 411, 375–379. doi: 10.1038/35077241

Luan, X., Wu, Y., Shen, Y., Zhang, H., Zhou, Y., Chen, H., et al. (2021). Cytotoxic and antitumor peptides as novel chemotherapeutics. Nat. Prod. Rep. 38, 7–17. doi: 10.1039/D0NP00019A

Luo, Y., and Song, Y. (2021). Mechanism of antimicrobial peptides: antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and antibiofilm activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22:11401. doi: 10.3390/ijms222111401

Luong, H. X., Thanh, T. T., and Tran, T. H. (2020). Antimicrobial peptides-Advances in development of therapeutic applications. Life Sci. 260:118407. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020

Lyu, C., Fang, F., and Li, B. (2019). Anti-tumor effects of melittin and its potential applications in clinic. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 20, 240–250. doi: 10.2174/1389203719666180612084615

Ma, X. X., Yang, N., Mao, R. Y., Hao, Y., Yan, X., Teng, D., et al. (2021). The pharmacodynamics study of insect defensin DLP4 against toxigenic Staphylococcus hyicus ACCC 61734 in vitro and vivo. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11:638598. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.638598

Macedo, M. W. F. S., Cunha, N. B. d., Carneiro, J. A., Costa, R. A. d., Alencar, S. A. d., Cardoso, M. H., et al. (2021). Marine organisms as a rich source of biologically active peptides. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:667764. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.667764

Mader, J. S., Mookherjee, N., Hancock, R. E., and Bleackley, R. C. (2009). The human host defense peptide LL-37 induces apoptosis in a calpain- and apoptosis-inducing factor-dependent manner involving Bax activity. Mol. Cancer Res. 7, 689–702. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0274

Mahlapuu, M., Hakansson, J., Ringstad, L., and Bjorn, C. (2016). Antimicrobial peptides: an emerging category of therapeutic agents. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 6:194. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00194

Mahmoud, M. M., Alenezi, M., Al-Hejin, A. M., Abujamel, T. S., Aljoud, F., Noorwali, A., et al. (2022). Anticancer activity of chicken cathelicidin peptides against different types of cancer. Mol. Biol. Rep. 49, 4321–4339. doi: 10.1007/s11033-022-07267-7

Maijaroen, S., Jangpromma, N., Daduang, J., and Klaynongsruang, S. (2018). KT2 and RT2 modified antimicrobial peptides derived from Crocodylus siamensis Leucrocin I show activity against human colon cancer HCT-116 cells. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 62, 164–176. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2018.07.007

Maiti, R., Patel, B., Patel, N., Patel, M., Patel, A., and Dhanesha, N. (2023). Antibody drug conjugates as targeted cancer therapy: past development, present challenges and future opportunities. Arch. Pharm. Res. 46, 361–388. doi: 10.1007/s12272-023-01447-0

Marggraf, M. B., Panteleev, P. V., Emelianova, A. A., Sorokin, M. I., Bolosov, I. A., Buzdin, A. A., et al. (2018). Cytotoxic potential of the novel horseshoe crab peptide polyphemusin III. Mar. Drugs 16:466. doi: 10.3390/md16120466

Marme, D. (2018). Tumor angiogenesis: a key target for cancer therapy. Oncol. Res. Treat. 41:164. doi: 10.1159/000488340

Maroti, G., Kereszt, A., Kondorosi, E., and Mergaert, P. (2011). Natural roles of antimicrobial peptides in microbes, plants and animals. Res. Microbiol. 162, 363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.02.005

Marqus, S., Pirogova, E., and Piva, T. J. (2017). Evaluation of the use of therapeutic peptides for cancer treatment. J. Biomed. Sci. 24:21. doi: 10.1186/s12929-017-0328-x

Medzhitov, R. (2008). Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature 454, 428–435. doi: 10.1038/nature07201

Meng, M. X., Ning, J. F., Yu, J. Y., Chen, D. D., Meng, X. L., Xu, J. P., et al. (2014). Antitumor activity of recombinant antimicrobial peptide penaeidin-2 against kidney cancer cells. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technolog. Med. Sci. 34, 529–534. doi: 10.1007/s11596-014-1310-4

Mirzaei, S., Fekri, H. S., Hashemi, F., Hushmandi, K., Mohammadinejad, R., Ashrafizadeh, M., et al. (2021). Venom peptides in cancer therapy: an updated review on cellular and molecular aspects. Pharmacol. Res. 164:105327. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105327

Mulder, K. C., Lima, L. A., Miranda, V. J., Dias, S. C., and Franco, O. L. (2013). Current scenario of peptide-based drugs: the key roles of cationic antitumor and antiviral peptides. Front. Microbiol. 4:321. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00321

Murugaiyan, G., and Saha, B. (2013). IL-27 in tumor immunity and immunotherapy. Trends Mol. Med. 19, 108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.12.002

Norouzi, P., Mirmohammadi, M., and Houshdar Tehrani, M. H. (2022). Anticancer peptides mechanisms, simple and complex. Chem. Biol. Interact. 368:110194. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2022.110194

Oelkrug, C., Hartke, M., and Schubert, A. (2015). Mode of action of anticancer peptides (ACPs) from amphibian origin. Anticancer Res. 35, 635–643.

Okumura, K., Itoh, A., Isogai, E., Hirose, K., Hosokawa, Y., Abiko, Y., et al. (2004). C-terminal domain of human CAP18 antimicrobial peptide induces apoptosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma SAS-H1 cells. Cancer Lett. 212, 185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.04.006

Okunaka, M., Kano, D., Matsui, R., Kawasaki, T., and Uesawa, Y. (2021). Comprehensive analysis of chemotherapeutic agents that induce infectious neutropenia. Pharmaceuticals 14:681. doi: 10.3390/ph14070681

Padanilam, B. J. (2003). Cell death induced by acute renal injury: a perspective on the contributions of apoptosis and necrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 284, F608–F627. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00284.2002

Pan, X., Xu, J., and Jia, X. (2020). Research progress evaluating the function and mechanism of anti-tumor peptides. Cancer Manag. Res. 12, 397–409. doi: 10.2147/cmar.S232708

Papo, N., Seger, D., Makovitzki, A., Kalchenko, V., Eshhar, Z., Degani, H., et al. (2006). Inhibition of tumor growth and elimination of multiple metastases in human prostate and breast xenografts by systemic inoculation of a host defense-like lytic peptide. Cancer Res. 66, 5371–5378. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4569

Paredes-Gamero, E. J., Martins, M. N., Cappabianco, F. A., Ide, J. S., and Miranda, A. (2012). Characterization of dual effects induced by antimicrobial peptides: regulated cell death or membrane disruption. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1820, 1062–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.02.015

Pernas, S., Martin, M., Kaufman, P. A., Gil-Martin, M., Gomez Pardo, P., and Lopez-Tarruella, S. (2018). Balixafortide plus eribulin in HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer: a phase 1, single-arm, dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol. 19, 812–824. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30147-5

Petrova, M., Vlahova, Z., Schröder, M., Todorova, J., Tzintzarov, A., and Gospodinov, A. (2023). Antitumor activity of bioactive compounds from Rapana venosa against human breast cell lines. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 16:181. doi: 10.3390/ph16020181

Pino-Angeles, A., Leveritt, J. M., and Lazaridis, T. (2016). Pore structure and synergy in antimicrobial peptides of the Magainin family. PLoS Comput. Biol. 12:e1004570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004570

Qi, J., Wang, W., Lu, W., Chen, W., Sun, H., and Shang, A. (2020). Design and biological evaluation of novel BF-30 analogs for the treatment of malignant melanoma. J. Cancer 11, 7184–7195. doi: 10.7150/jca.47549

Qin, B., Yuan, X., Jiang, M., Yin, H., Luo, Z., Zhang, J., et al. (2020). Targeting DNA to the endoplasmic reticulum efficiently enhances gene delivery and therapy. Nanoscale 12, 18249–18262. doi: 10.1039/d0nr03156a

Qin, Y., Qin, Z. D., Chen, J., Cai, C. G., Li, L., Feng, L. Y., et al. (2019). From antimicrobial to anticancer peptides: the transformation of peptides. Recent Pat. Anticancer Drug Discov. 14, 70–84. doi: 10.2174/1574892814666190119165157

Quah, Y., Tong, S. R., Bojarska, J., Giller, K., Tan, S. A., Ziora, Z. M., et al. (2023). Bioactive peptide discovery from edible insects for potential applications in human health and agriculture. Molecules 28:1233. doi: 10.3390/molecules28031233

Rahman, R., Fonseka, A. D., Sua, S. C., Ahmad, M., Rajendran, R., Ambu, S., et al. (2021). Inhibition of breast cancer xenografts in a mouse model and the induction of apoptosis in multiple breast cancer cell lines by lactoferricin B peptide. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 25, 7181–7189. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.16748

Ren, S. X., Shen, J., Cheng, A. S., Lu, L., Chan, R. L., Li, Z. J., et al. (2013). FK-16 derived from the anticancer peptide LL-37 induces caspase-independent apoptosis and autophagic cell death in colon cancer cells. PLoS One 8:e63641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063641

Rozek, T., Wegener, K. L., Bowie, J. H., Olver, I. N., Carver, J. A., Wallace, J. C., et al. (2000). The antibiotic and anticancer active aurein peptides from the Australian Bell Frogs Litoria aurea and Litoria raniformis the solution structure of aurein 1.2. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 5330–5341. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01536.x

Ryan, L., Lamarre, B., Diu, T., Ravi, J., Judge, P. J., Temple, A., et al. (2013). Anti-antimicrobial peptides: folding-mediated host defense antagonists. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 20162–20172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.459560

Schibli, D. J., Epand, R. F., Vogel, H. J., and Epand, R. M. (2002). Tryptophan-rich antimicrobial peptides: comparative properties and membrane interactions. Biochem. Cell Biol. 80, 667–677. doi: 10.1139/o02-147