- 1Department of Medicinal Chemistry and Natural Medicine Chemistry, College of Pharmacy, Harbin Medical University, Harbin, China

- 2Key Laboratory of Gut Microbiota and Pharmacogenomics of Heilongjiang Province, College of Pharmacy, Harbin Medical University, Harbin, China

- 3The Third Affiliated Hospital of Heilongjiang University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Harbin, China

Cyclodepsipeptides are a large family of peptide-related natural products consisting of hydroxy and amino acids linked by amide and ester bonds. A number of cyclodepsipeptides have been isolated and characterized from fungi and bacteria. Most of them showed antitumor, antifungal, antiviral, antimalarial, and antitrypanosomal properties. Herein, this review summarizes the recent literatures (2010–2022) on the progress of cyclodepsipeptides from fungi and bacteria except for those of marine origin, in order to enrich our knowledge about their structural features and biological sources.

Introduction

Cyclodepsipeptides are an important group of polypeptides, which contain one or more amino acids replaced by a hydroxy acid, resulting in at least one ester bond in the core ring structure (Lemmens-Gruber et al., 2009; Buckton et al., 2021). Cyclodepsipeptides exhibit a broad spectrum of biological activities including antitumor, antifungal, antiviral, antimalarial, and antitrypanosomal activities (Moore, 1996; Nihei et al., 1998; Du et al., 2014). Due to their unique structural and biological properties, cyclodepsipeptides have emerged as promising lead structures for crop protection and human and veterinary medicine (Sivanathan and Scherkenbeck, 2014).

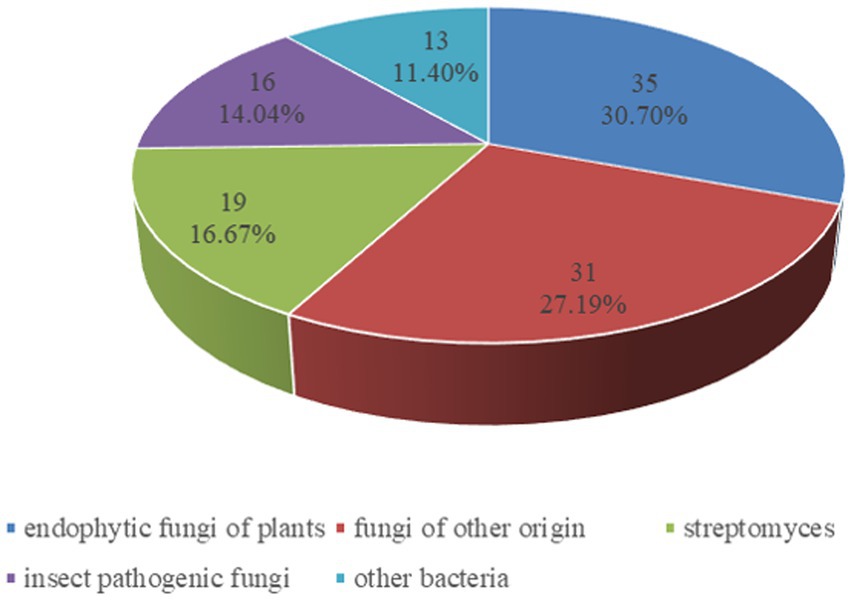

The dominant sources of cyclodepsipeptides are fermentations of various fungi and bacteria. In addition, abundant cyclodepsipeptides have been isolated from algae, plants and marine organism (Sivanathan and Scherkenbeck, 2014; Negi et al., 2017). Because several reports have summarized the progress of the marine cyclodepsipeptides (Zeng et al., 2023), our review focused on the recent advances of cyclodepsipeptides from bacteria and fungi from plants, insects or soil except for marine organism. As a result, from 2010 to the present, 114 cyclodepsipeptides have been isolated and identified through an extensive literature search, including Web of Science, SciFinder, and PubChem tools. Included in the list of search terms were “cyclodepsipeptides,” “endophytic fungi,” and “insect pathogenic fungi” as well as “streptomyces,” “fungi,” “bacteria.” As shown in Figure 1, the major producers of cyclodepsipeptides are endophytic fungi of plants, which made up 30.70%, followed by fungi of other origin (27.19%), streptomyces (16.67%), insect pathogenic fungi (14.04%), and other bacteria (11.40%).

Biologically active cyclodepsipeptides

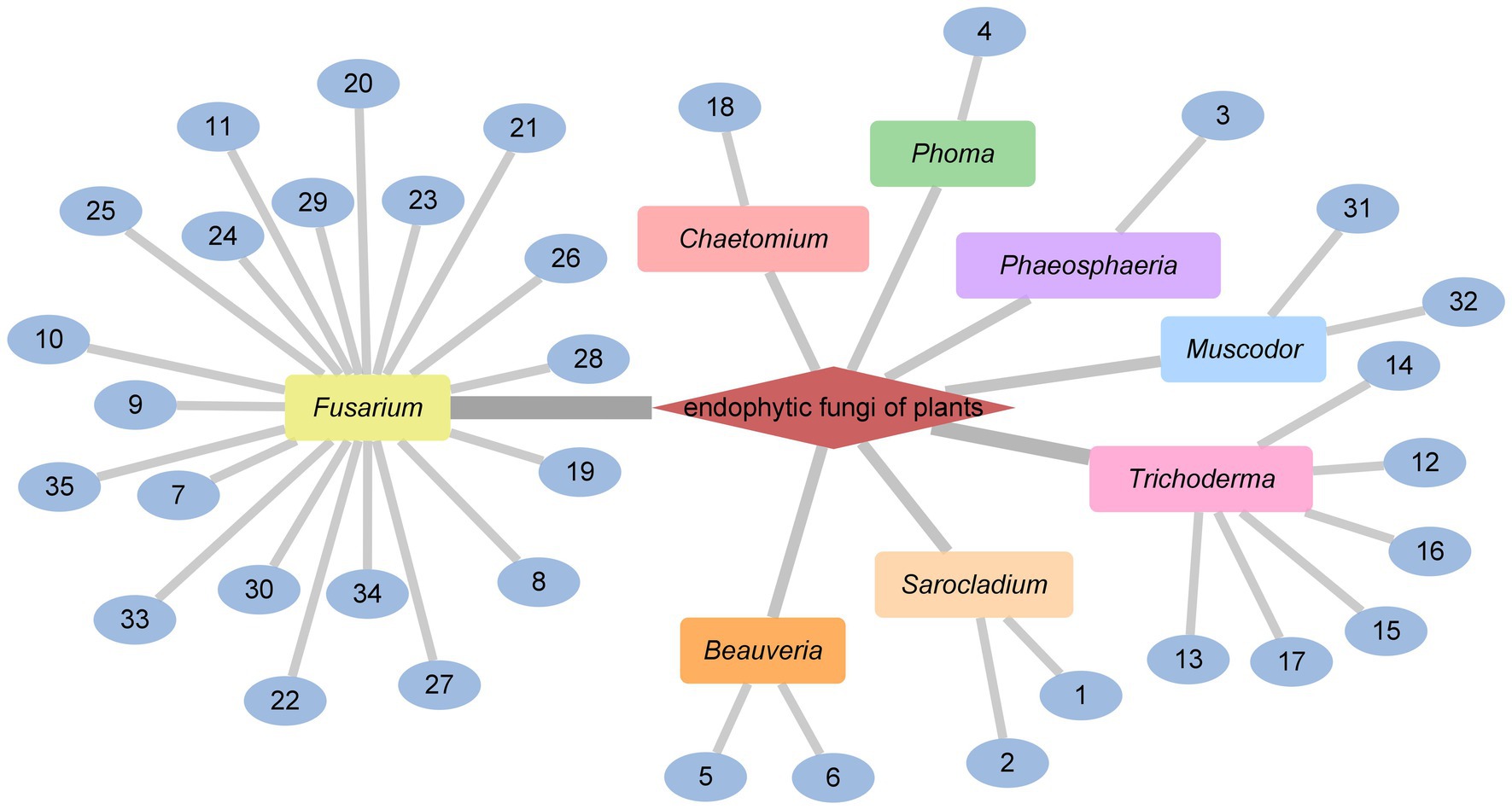

Cyclodepsipeptides from endophytic fungi of plants

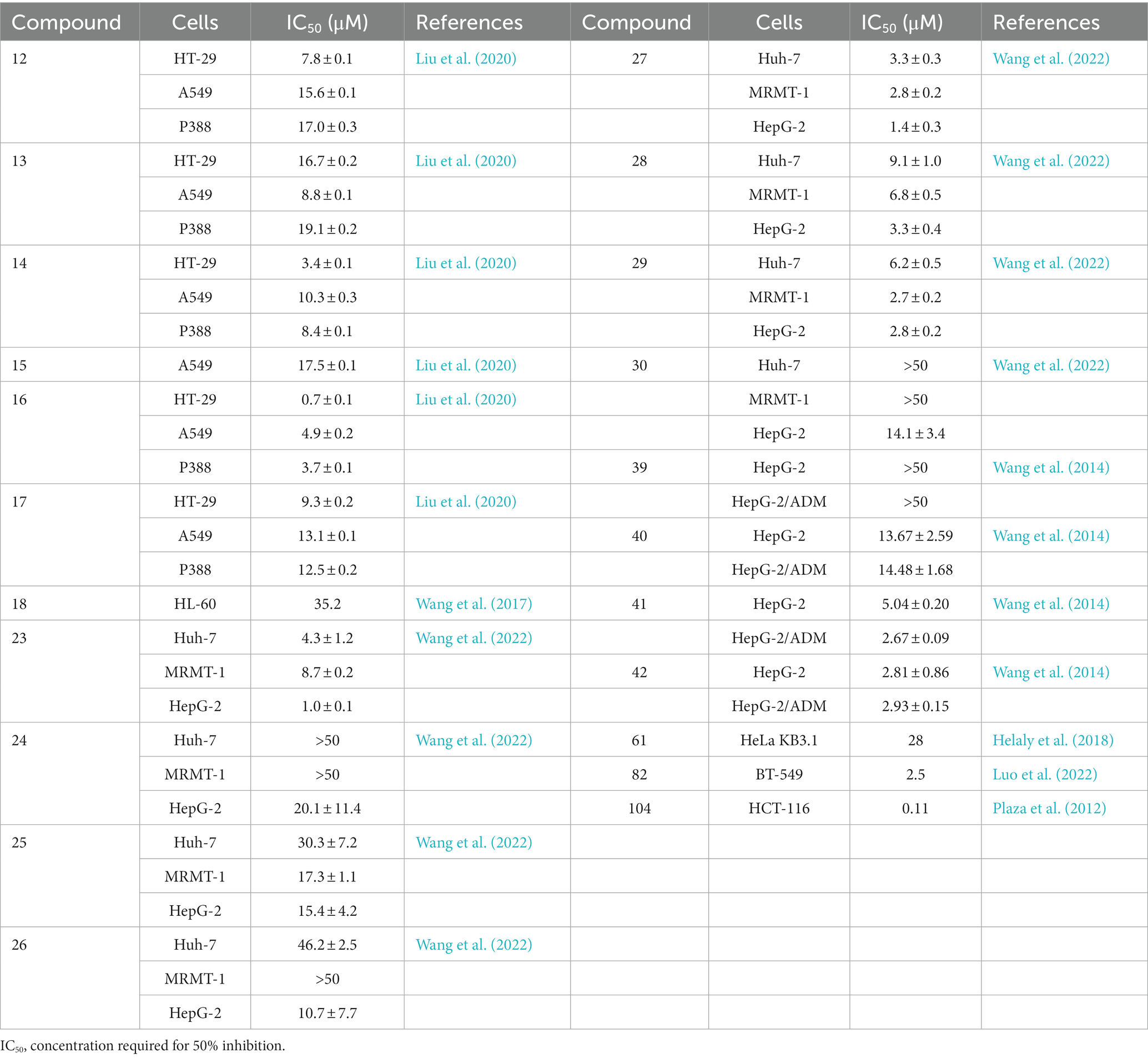

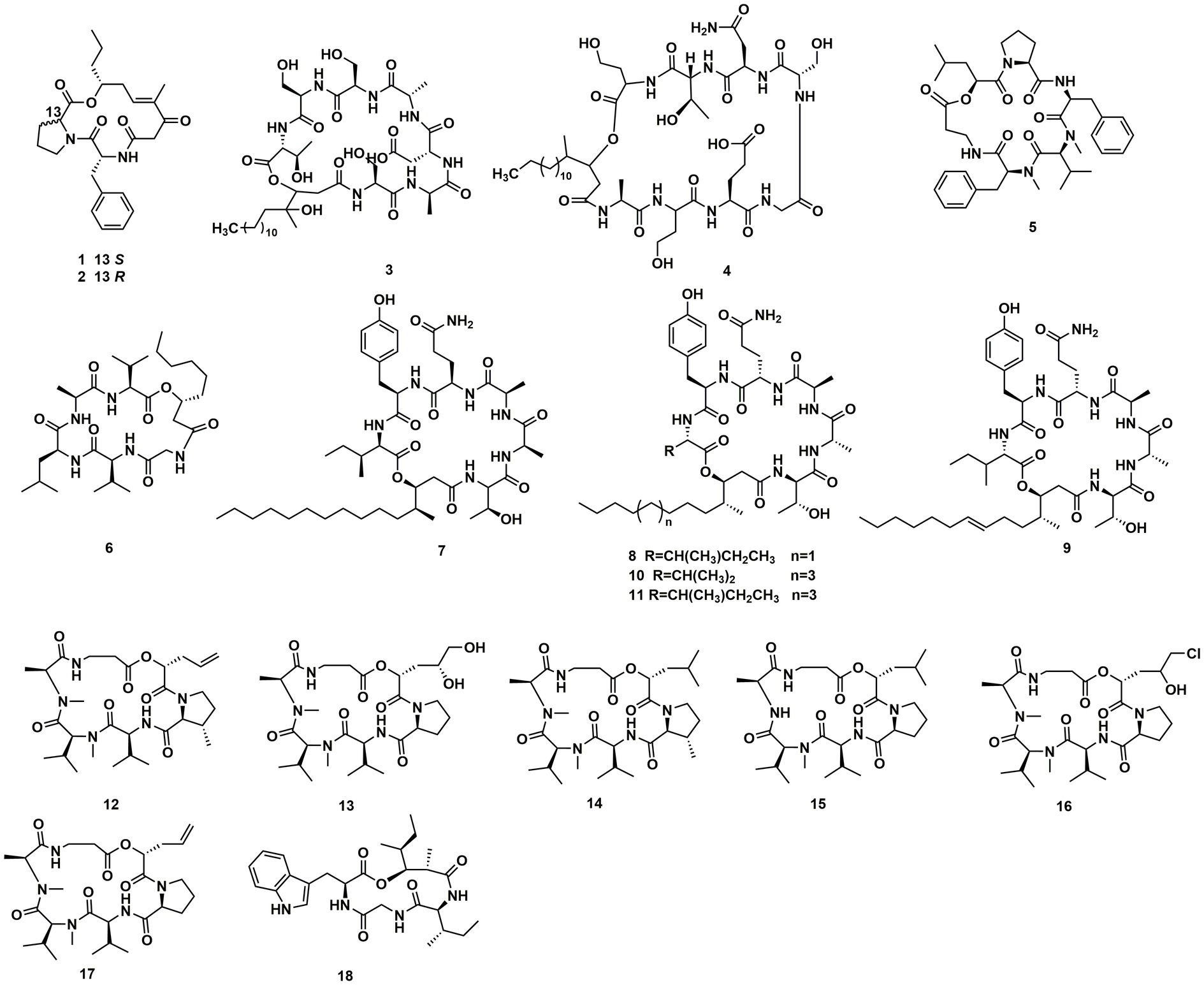

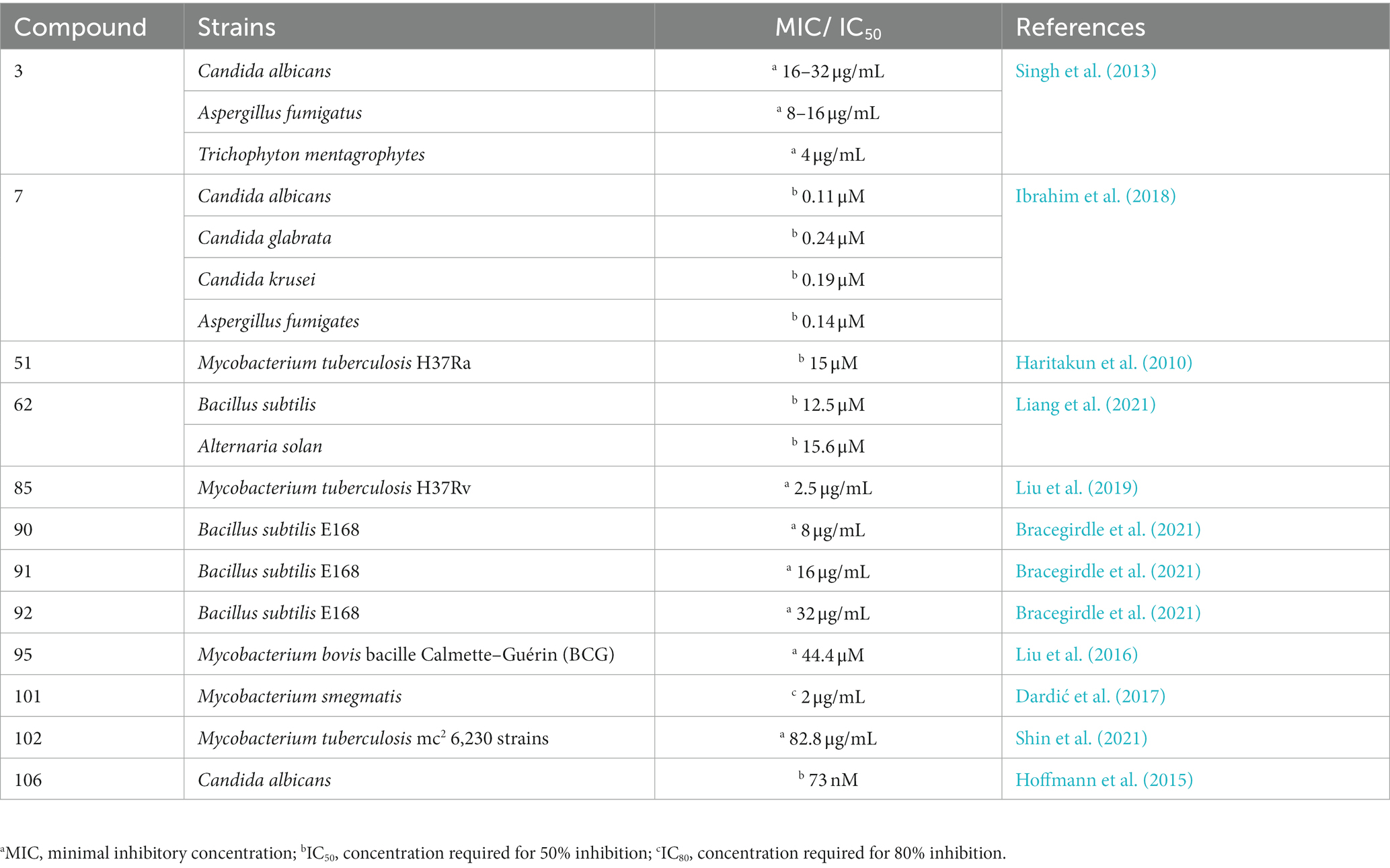

The endophytic fungi from Fusarium and Tricholderma genus were the main producers of cyclodepsipeptides. Chemical investigation on the fungus Sarocladium kiliense HDN11-112 from mangroves, led to the characterization of saroclide A (1) and saroclide B (2), two cyclic depsipeptides with 7-hydroxy-4-methyl-3-oxodec-4-enoic acid (HMODA) unit. They were a couple of epimerides with different L-and D-Pro configurations of the proline units. Saroclide A (1) exhibited a lowering blood lipid effect, while saroclide A (1) and B (2) were invalid for four pathogenic microorganisms and five cancer cell lines (Guo et al., 2018). Using a genome-wide Candida albicans fitness test, a new cyclodepsipeptide phaeofungin (3) containing a β,γ-dihydroxy-γ-methylhexadecanoic acid (DHMHDA) unit and seven amino acids, was isolated from Phaeosphaeria sp. Using the same method, another structurally different cyclodepsipeptide, phomafungin (4), was isolated from Phoma sp. 3 showed good antifungal activity to Aspergillus fumigatus with the MIC value at 8–16 μg/mL and Trichophyton mentagrophytes with the MIC value at 4 μg/mL (Singh et al., 2013). Isaridins A (5) and B (6) were isolated from Beauveria sp. Lr89, which was isolated from the roots of Maytenus hookeri Loes (Li et al., 2011). Fusaripeptide A (7), a novel cyclodepsipeptide, obtained from the culture of the plant endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. 7 showed significant antifungal activity against A. fumigates, Candida glabrata, Candida albicans and Candida krusei (IC50 0.11–0.24 μM). In addition, it exhibited potent anti-malarial activity against Plasmodium falciparum (IC50 0.34 μM) (Ibrahim et al., 2018). W493 C (8) and W493 D (9), two novel cyclic depsipeptides, as well as two known cyclic depsipeptides, W493 A (10) and W493 B (11), were isolated from the mangrove plant Ceriops tagal endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. 8 and 9 showed antifungal activity toward Cladosporium cladosporiodes (Lv et al., 2015). Bioassay-guided isolation and purification yielded four new cyclodepsipeptides, trichodestruxins A (12), B (13), C (14) and D (15), as well as two known cyclodepsipeptides, destruxin E2 chlorohydrin (16) and destruxin A2 (17), isolated from the fungus Trichoderma harzianum. 14 and 16 were evaluated for their cytotoxicity against HT-29, A549, and P388 cell lines with IC50 values at 0.7–10.3 μM (Liu et al., 2020; Table 1). Chaetomiamide A (18), a rare cyclodepsipeptide, was isolated from the fungus Chaetomium sp. from the root of Cymbidium goeringii, it also exhibited weak cytotoxicity toward HL-60 cell line with IC50 values of 35.2 μM (Wang et al., 2017; Figure 2).

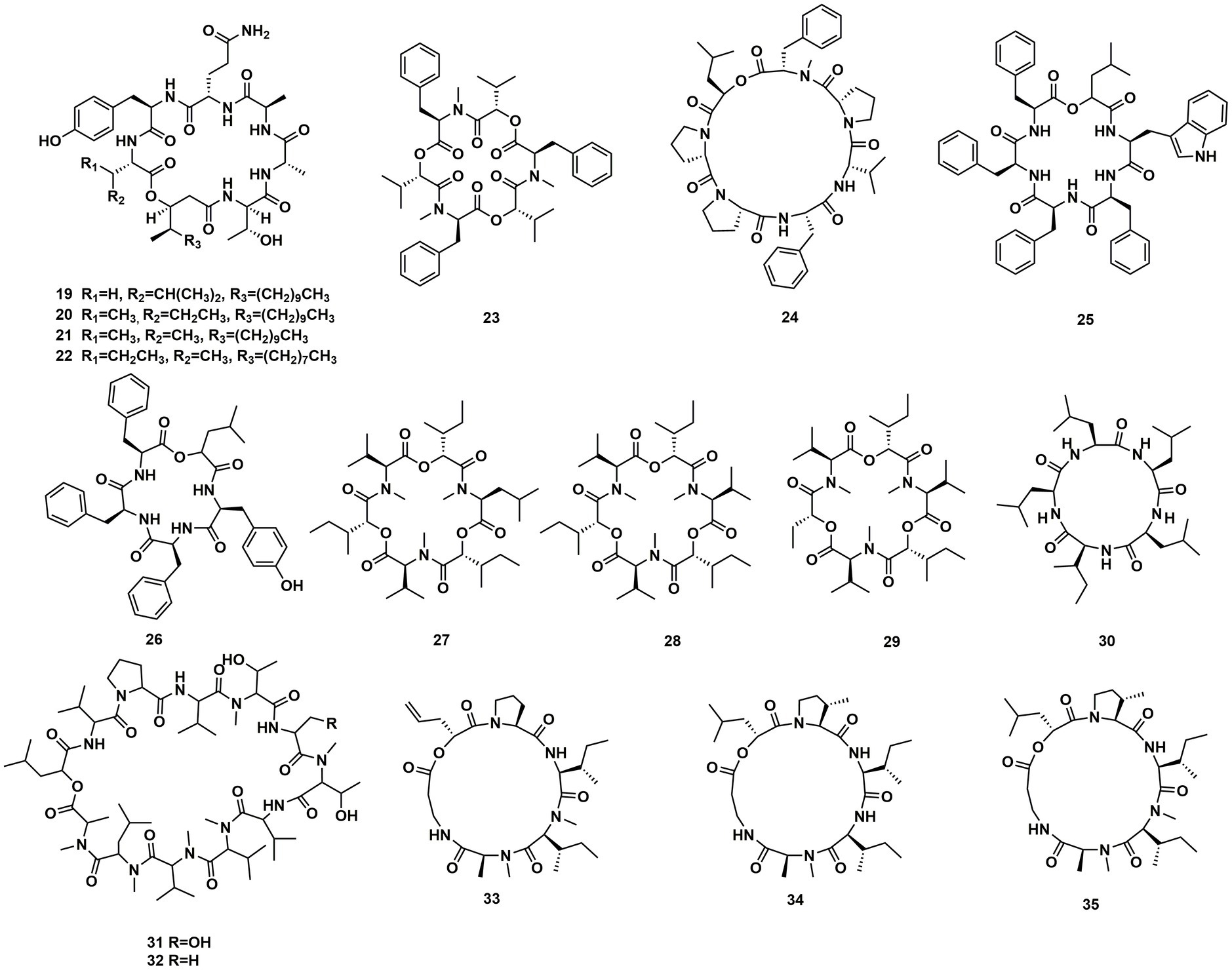

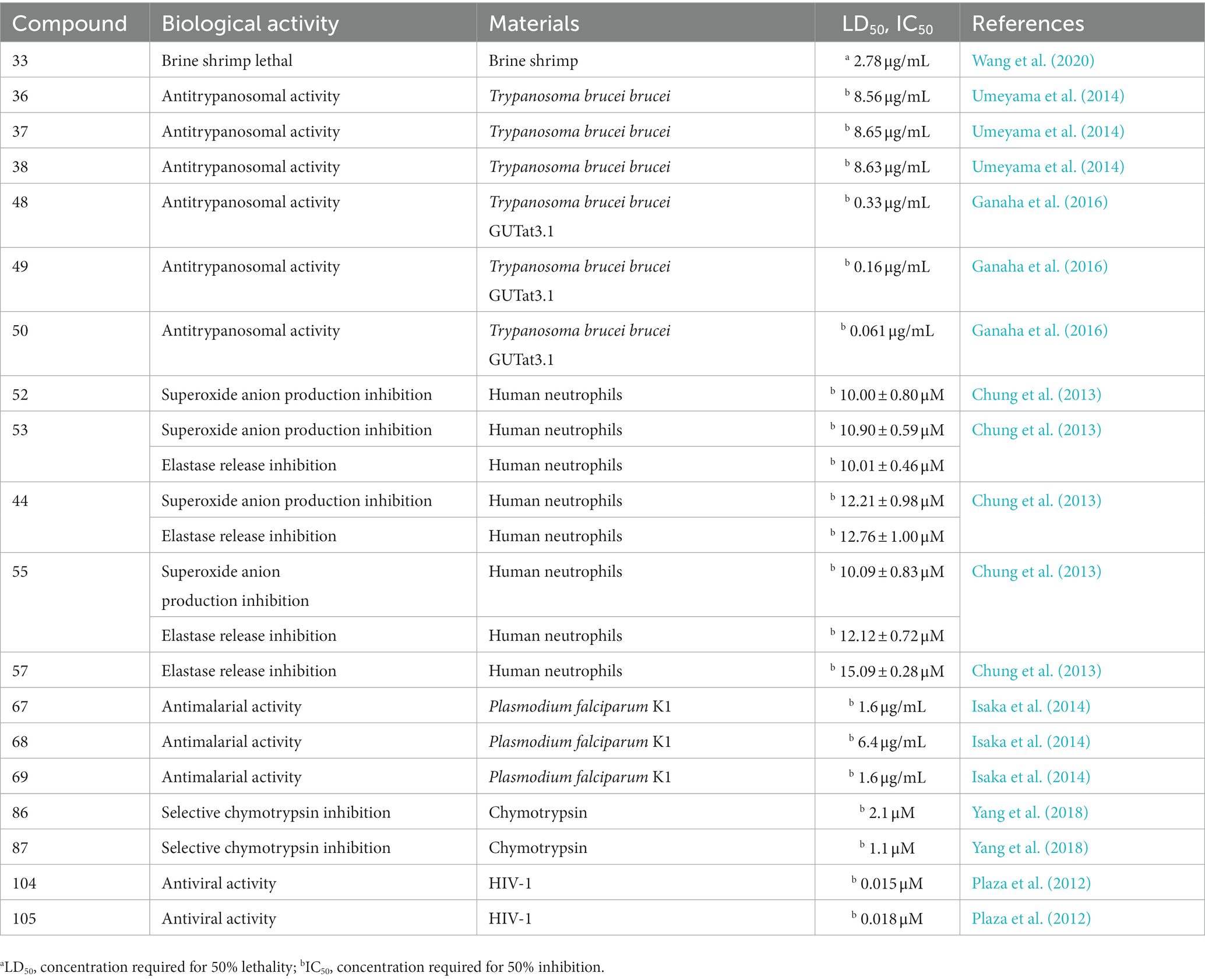

A Celtis sinensis-derived Fusarium sp. HU0174, produced acuminatums A–D (19–22), as well as beauvericin (23). Acuminatum D (22) was a novel cyclic depsipeptide. 19–22 exhibited potent inhibitory activity against Penicillium digitatum and Curvularia lunata using the AGAR disc diffusion methods (Li et al., 2021). Cultivation of the plant endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. led to the isolation of four novel compounds, fusarihexins C (24), D (25), E (26), and enniatin Q (27), together with the known beauvericin (23), MK1688 (28), enniatin I (29), viscumamide (30). The cytotoxic activities of these compounds were tested using MRMT-1, HepG-2, and Huh-7 cell lines, respectively (Table 1). 27–29, and 23 exhibited strong cytotoxic activities (Wang et al., 2022; Figure 3). Two depsipeptides named xylariaceins A–B (31–32) were isolated and identified from endophytes Xylariaceae BSNB-0294. Both xylariaceins A (31) and B (32) inhibited the growth of Fusarium oxysporum (Barthélemy et al., 2021). In addition, three cyclohexadepsipeptides, destruxin A4 (33), trichomide B (34) and homodestcardin (35), isolated from the endophytic fungus Fusarium chlamydosporum, were found to be lethal to brine shrimp, 33 showed significant activity with LD50 at 2.78 μg/mL. It was even better than the positive control (7.75 μg /mL) (Wang et al., 2020).

In conclusion, the genus Fusarium and Trichoderma were the main producers of cyclodepsipeptides in endophytic fungi. In addition, the genus Beauveria, Sarocladium, Muscodor, Chaetomium, Phoma, Phaeosphaeria could produce diverse cyclodepsipeptides as well (Figure 4).

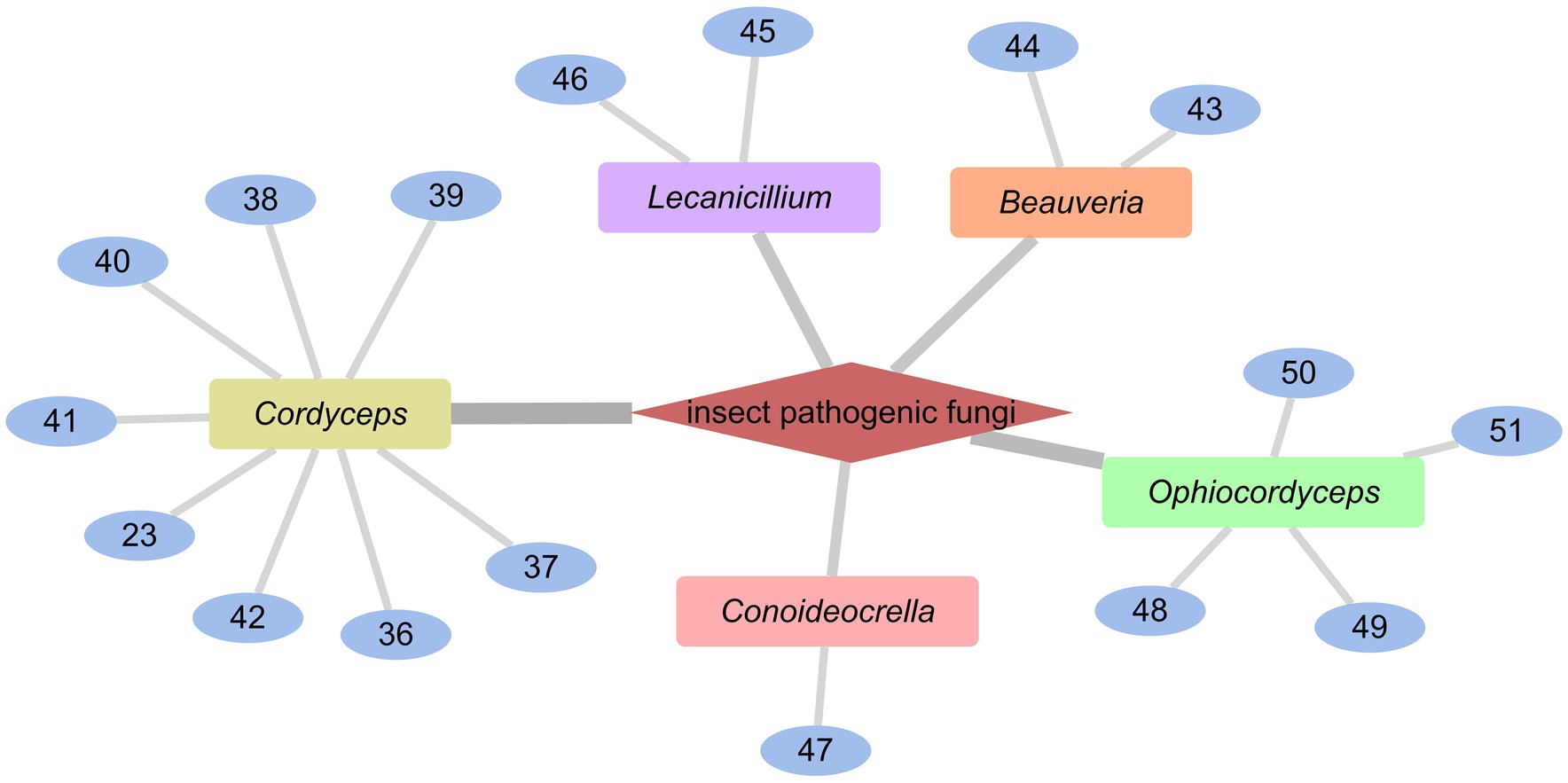

Cyclodepsipeptides from insect pathogenic fungi

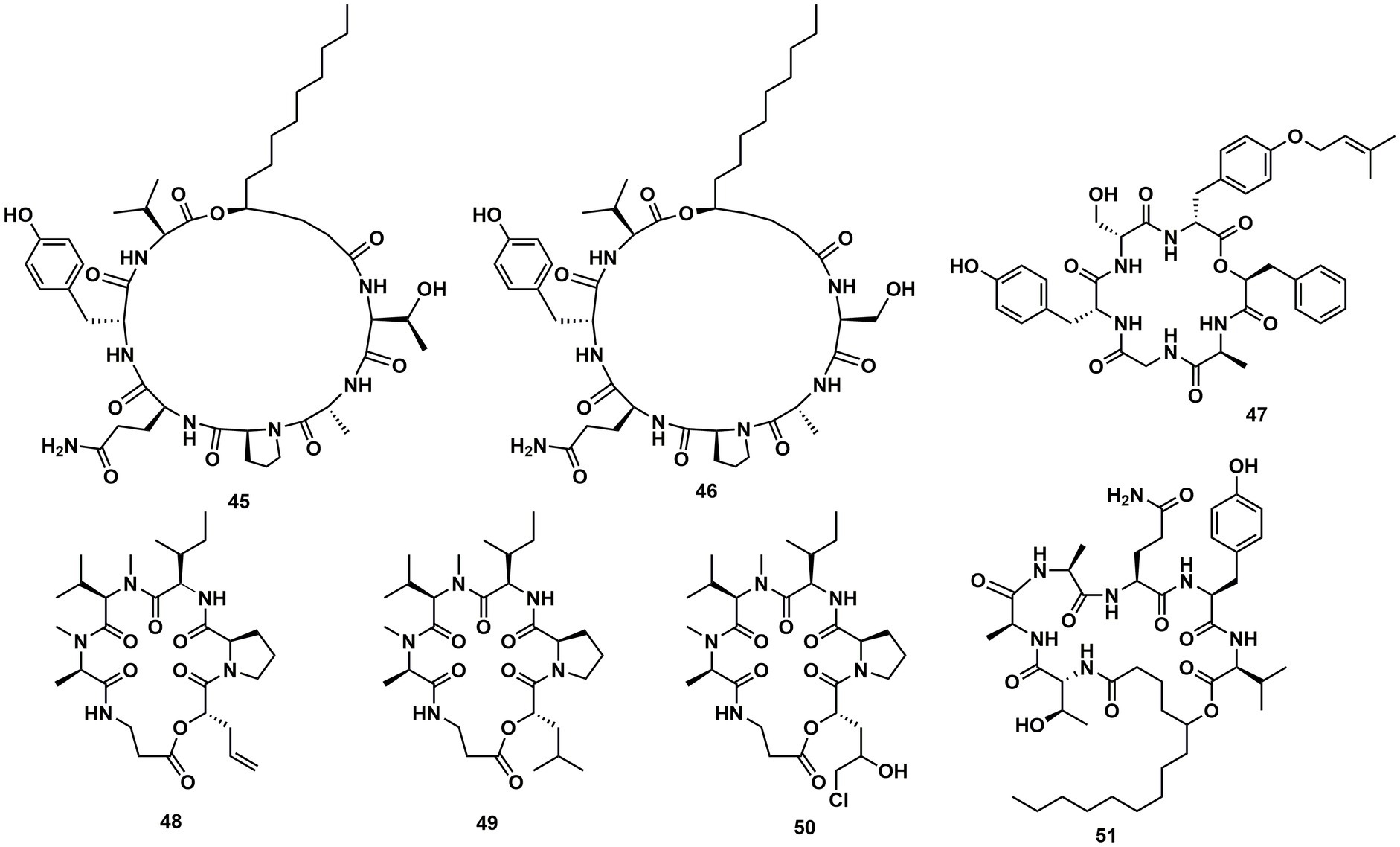

Cordyceps cardinalis NBRC 103832, the insect pathogenic fungus, yielded a class of new depsipeptides, cardinalisamides A (36), B (37), C (38). The bioactivity results indicated that 36–38 exhibited in vitro antitrypanosomal activity against Trypanosoma brucei brucei with IC50 values of 8.56, 8.65 and 8.63 μg/mL, respectively (Umeyama et al., 2014). Cordycecin A (39), a new cyclodepsipeptide, together with beauvericin E (40), beauvericin J (41), beauvericin (23) and beauvericin A (42), were isolated from the fungus Cordyceps cicadae, which was a fungus parasitic on the larvae of Cicada flammat as the host insect (Wang et al., 2014). Compounds 23, 40–42 exhibited cytotoxicity toward HepG2 and HepG2/ADM cells with IC50 values at 2.40–14.48 μM. The insect pathogenic fungus Beauveria felina yielded iso-isariin B (43) and isaridin E (44) (Langenfeld et al., 2011; Figure 5).

Verlamelins A (45) and B (46) were isolated from insect pathogenic fungus Lecanicillium sp. HF627. 45 showed broad antifungal activity against plant pathogenic fungi (Ishidoh et al., 2014). Conoideocrellide A (47) was a new cyclodepsipeptide isolated from the entomopathogenic fungus Conoideocrella. tenuis BCC 18627. Unfortunately, tests showed that 47 had no biological activity in protocols for antiplasmodial and antiviral properties as well as cytotoxicity against a number of cancer cell lines (Isaka et al., 2011). The isolation of entomopathogenic fungus Ophiocordyceps coccidiicola NBRC 100683 mutant strain IU-3 provided three cyclodepsipeptides, destruxins A (48), B (49), and destruxin E chlorohydrin (50). The in vitro antitrypanosomal activity exhibited that the IC50 values for 48–50 against T. b. brucei GUTat3.1 were 0.33, 0.16 and 0.061 μg/mL (Ganaha et al., 2016). The entomopathogenic fungus Ophiocordyceps communis BCC 16475 yielded a new cyclodepsipeptide, cordycommunin (51). 51 was demonstrated to have growth inhibitory effect on Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra (MIC 15 μM) (Haritakun et al., 2010; Figures 6, 7; Table 2).

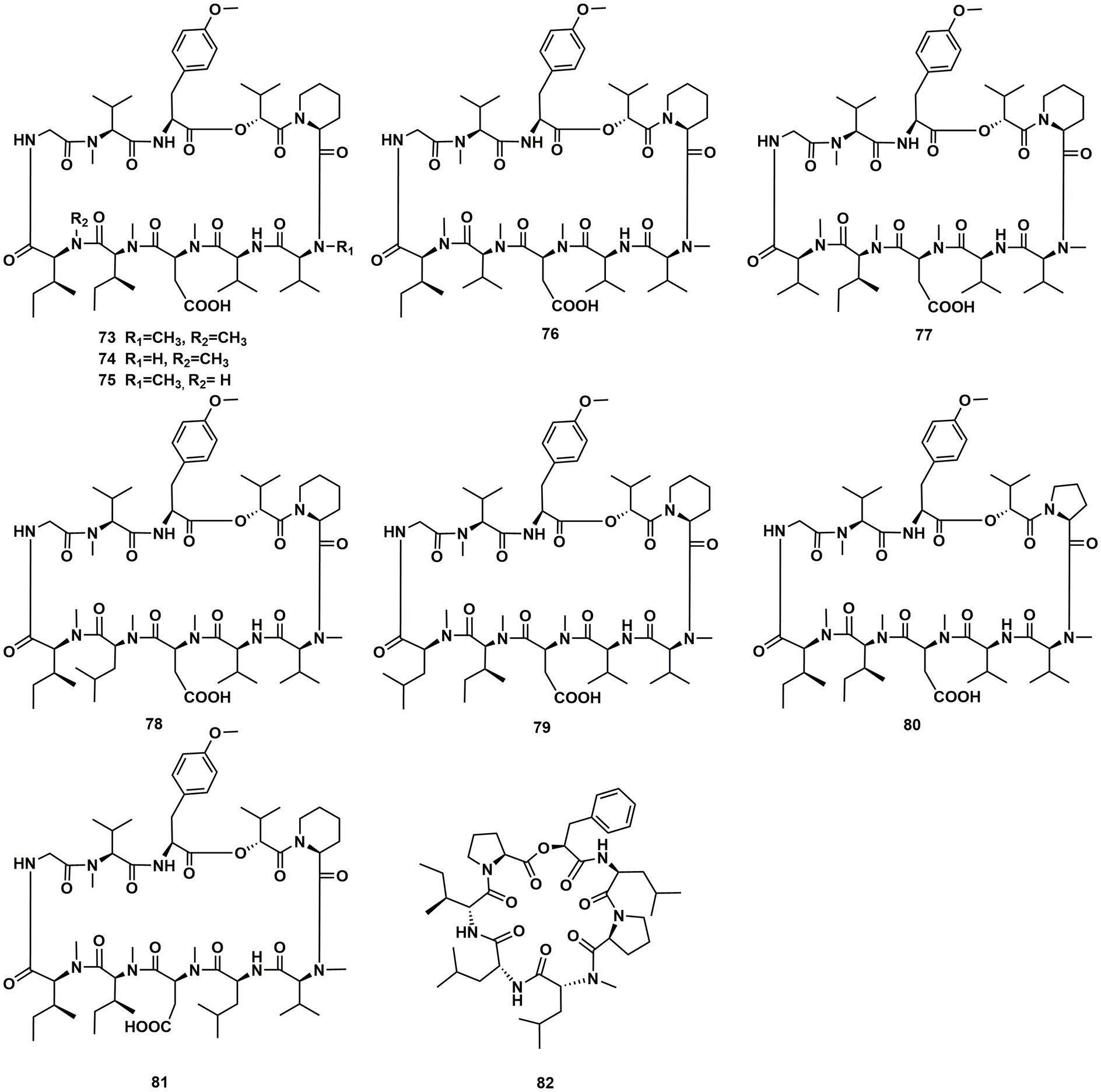

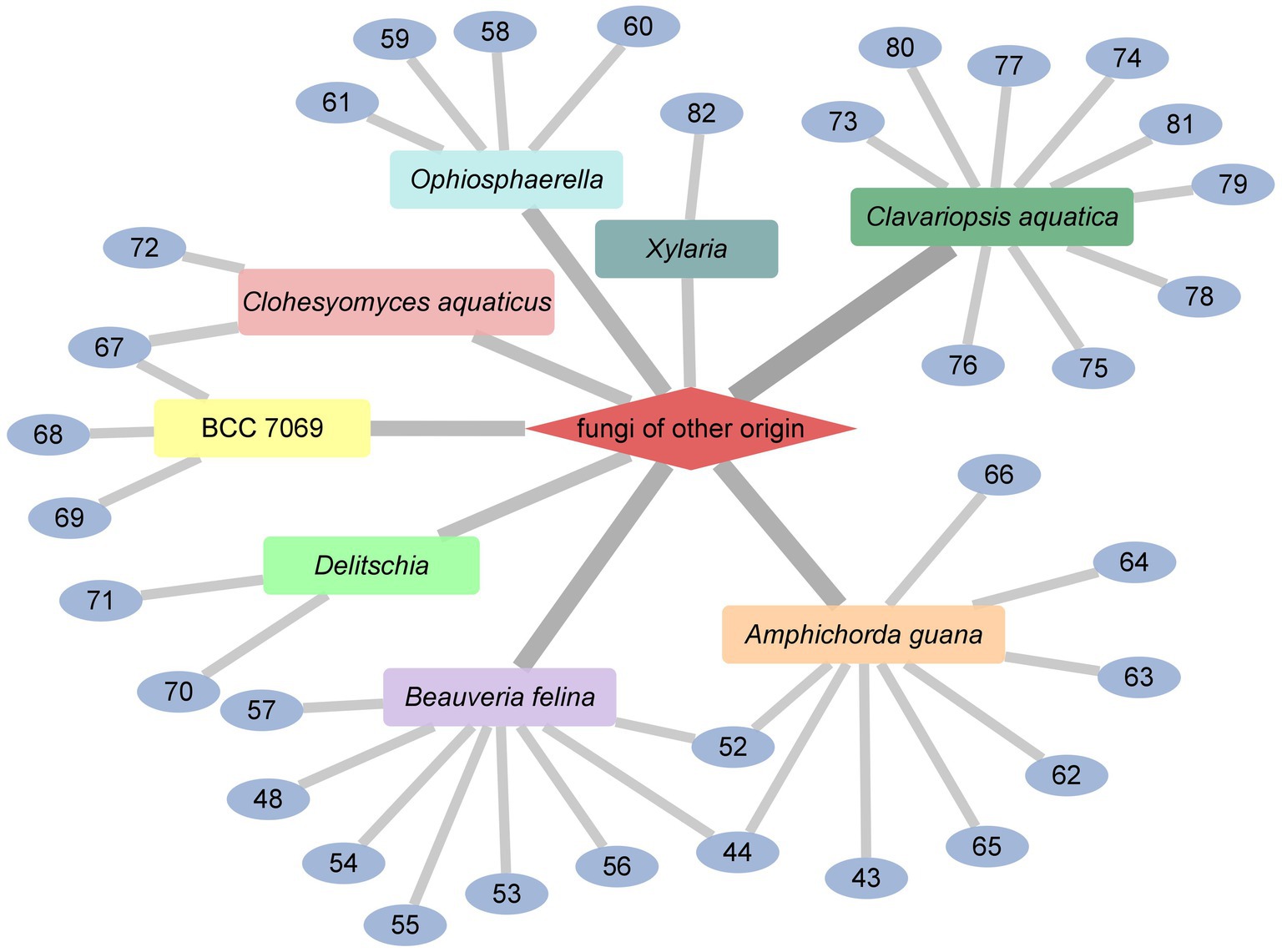

Cyclodepsipeptides from fungi of other origin

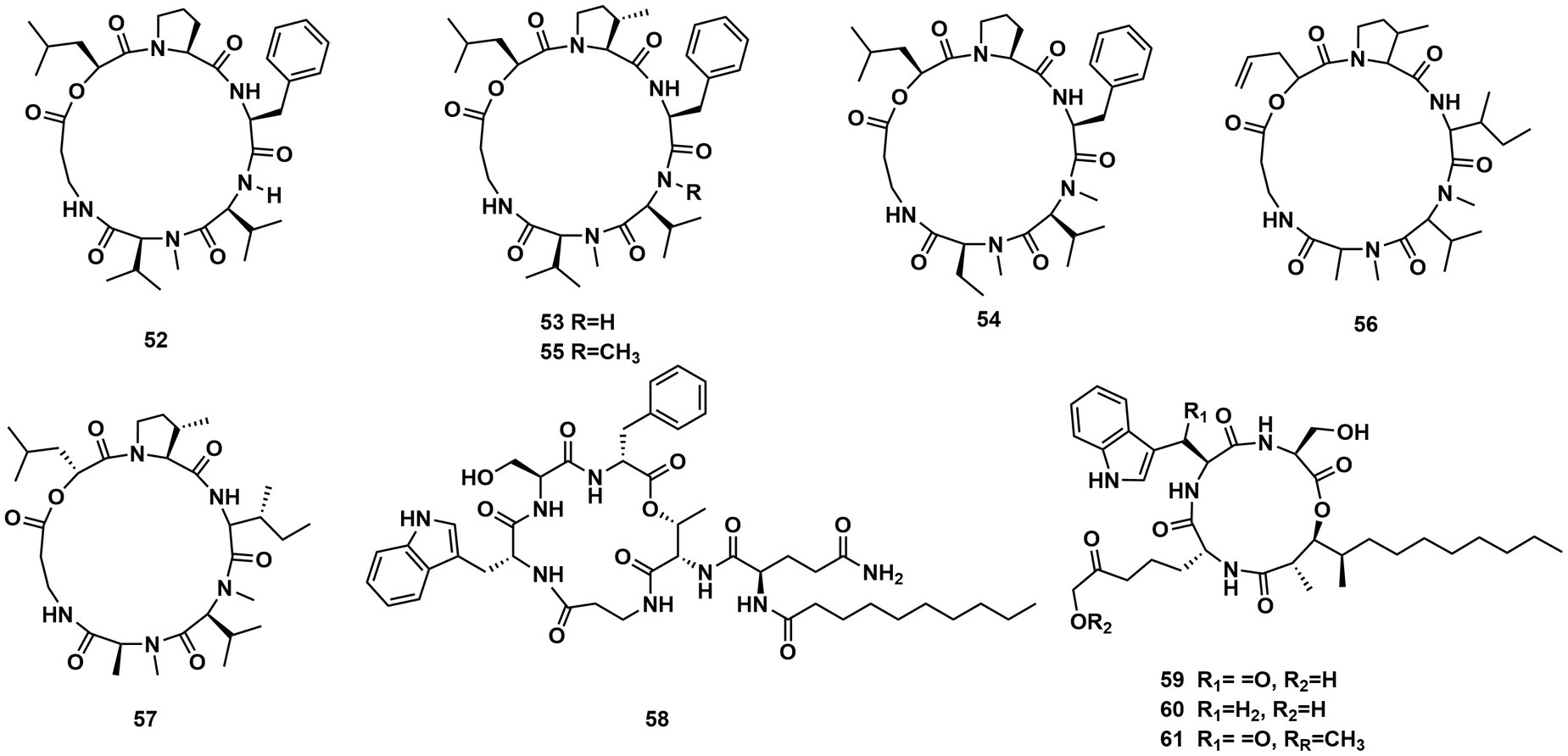

Desmethylisaridin E (52), desmethylisaridin C2 (53), isaridin F (54) and isaridin E (44), isaridin C2 (55), destruxin A (48), resetoxin B (56), and roseocardin (57) were collected from hefilamentous fungus Beauveria felina. On the elastase release in neutrophils and the FMLP-induced superoxide anion generation, 52 and 53 showed specific inhibitory action. Compound 52 demonstrated particular inhibition on superoxide anion generation with an IC50 at 10.0 μM, while 53 exhibited specific activity on elastase release with an IC50 at 10.01 μM (Chung et al., 2013). A fungus linked with nematodes that shared affinities with the genus Ophiosphaerella, produced ophiotine (58), along with two new derivatives arthrichitin (59) and arthrichitin B (60) as well as one known compound arthrichitin C (61). Only 61 exhibited a low level of cytotoxicity, with an IC50 value of 28 μM against HeLa cells KB3.1 (Helaly et al., 2018; Figure 8).

A new cyclodepsipeptide isaridin H (62), as well as known compounds isariin A (63), isariin E (64), nodupetide (65), iso-isariin D (66) and iso-isariin B (43) isaridin E (44), desmethylisaridin E (52) were identified from Amphichorda guana. Based on the bioassay, the novel cyclodepsipeptide isaridin H (62) exhibited suppression of Bacillus subtilis at 12.5 μM and displayed potent antifungal activities toward Alternaria solan (IC50 15.6 μM) (Liang et al., 2021). A new class of cyclodepsipeptides SCH 217048 (67), SCH 218157 (68), together with pleosporin A (69) were collected from an elephant dung fungus BCC 7069. With IC50 values of 1.6, 6.4, and 1.6 µg/mL, respectively, all three compounds demonstrated antimalarial efficacy against P. falciparum K1 (Isaka et al., 2014). Artrichitin (70) and lipopeptide 15G256ε (71) were isolated from freshwater ascomycetes (Delitschia sp.). Under hypoxic conditions, the African American prostate cancer cell line (E006AA-hT) was resistant to the antiproliferative effects of both 70 and 71 (Rivera-Chávez et al., 2019). Two known cyclodepsipeptides named SCH 378161 (72) and SCH 217048 (67) were isolated from organic extracts of axenic Clohesyomyces aquaticus (Dothideomycetes) (El-Elimat et al., 2017; Figure 9).

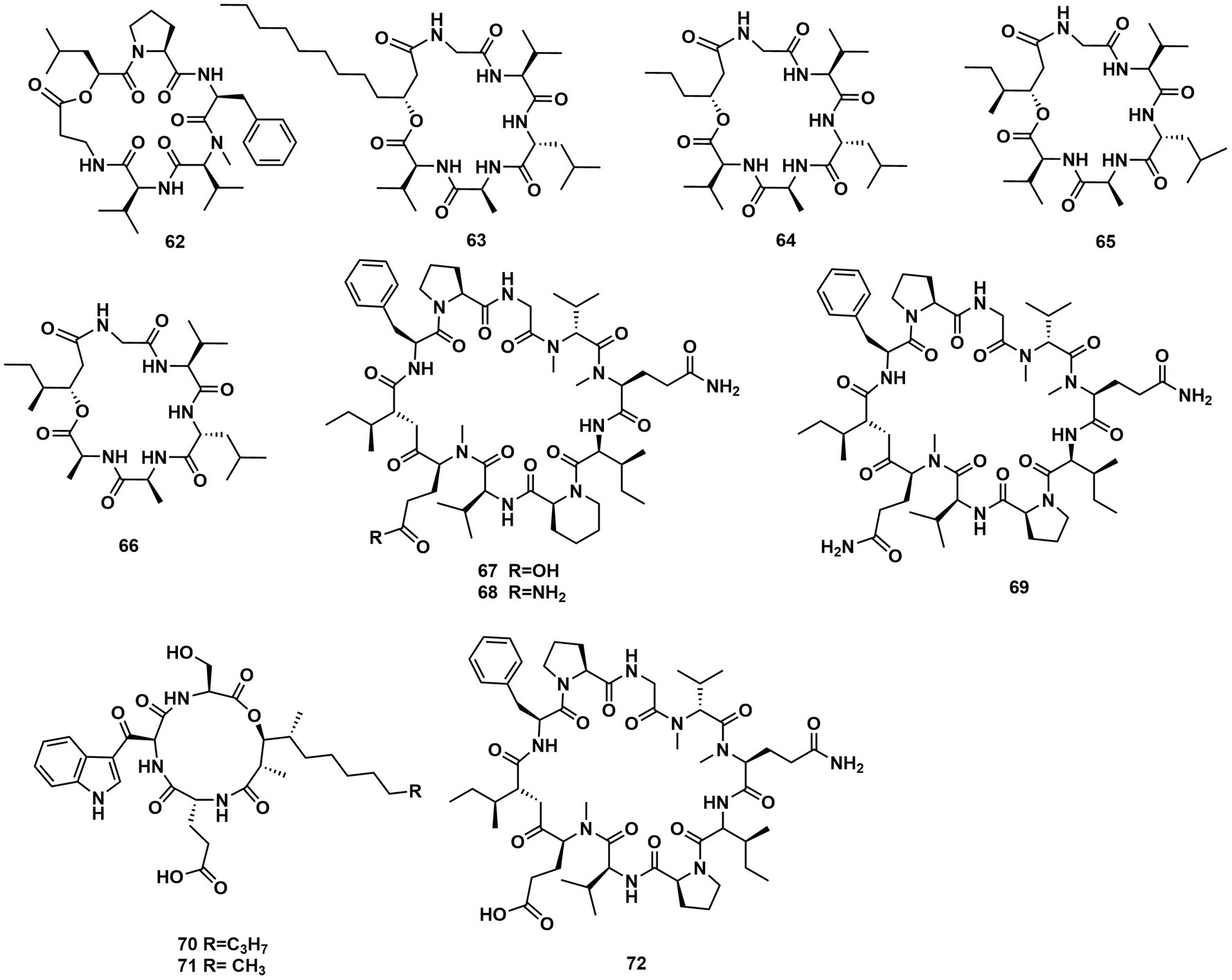

The cyclic depsipeptides clavariopsins A–I (73–81) were found through fractions of the extract of the aquatic hyphomycete Clavariopsis aquatica. They provided significant or moderate antifungal activity toward primarily multihost plant pathogens (Soe et al., 2019). Xylaroamide A (82), a cyclic depsipeptide, was isolated from an endolichenic Xylaria sp. Following a series of biological tests, it was discovered that 82 had an IC50 value of 2.5 μM and had the most powerful impact on the human triple-negative epithelial breast cancer cell line, BT-549. In addition, 82 strongly induced cell cycle arrest in G0/G1 phase in BT-549 cells by using cycle distribution analysis (Luo et al., 2022; Figures 10, 11).

Cyclodepsipeptides from streptomyces

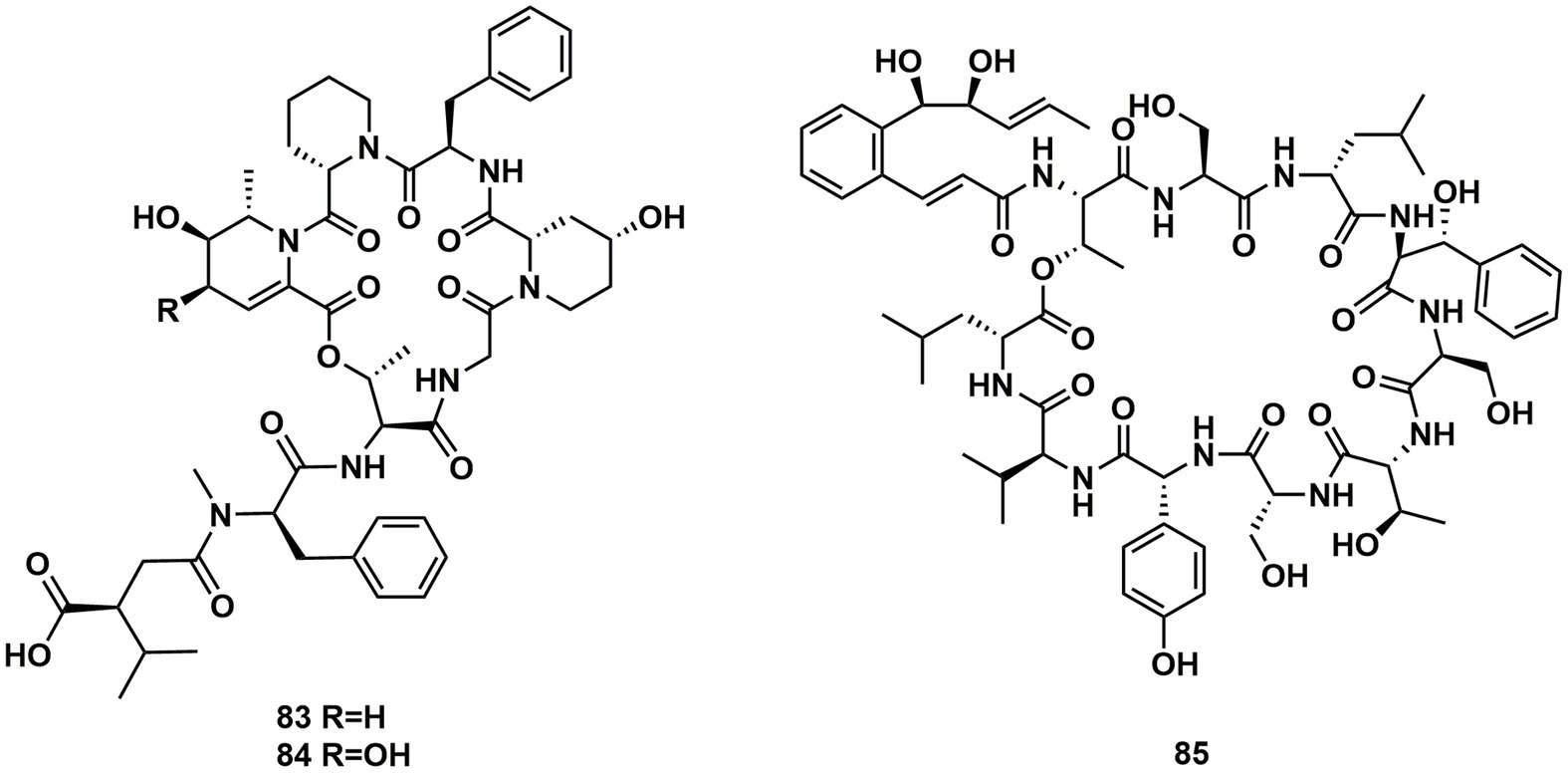

Ulleungamides A (83) and B (84), two new cyclic depsipeptides, were found in terrestrial cultured strains Streptomyces sp. Only Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella typhimurium showed growth inhibition by ulleungamide A (83) without cytotoxicity. Besides, Comparing 83 to 84, the selective antibacterial activity showed that the hydroxy group at position C-4 significantly lowered the activity (Son et al., 2015). Atrovimycin (85), featuring a novel vicinal-hydroxylated cinnamic acylchain, was a cyclodepsipeptide separated from Streptomyces atrovirens LQ13. A series of biological assays revealed that 85 showed a significant activity toward F. oxysporum and antitubercular activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv both in vitro (with MIC of 2.5 μg/mL) and in vivo (Liu et al., 2019; Figure 12).

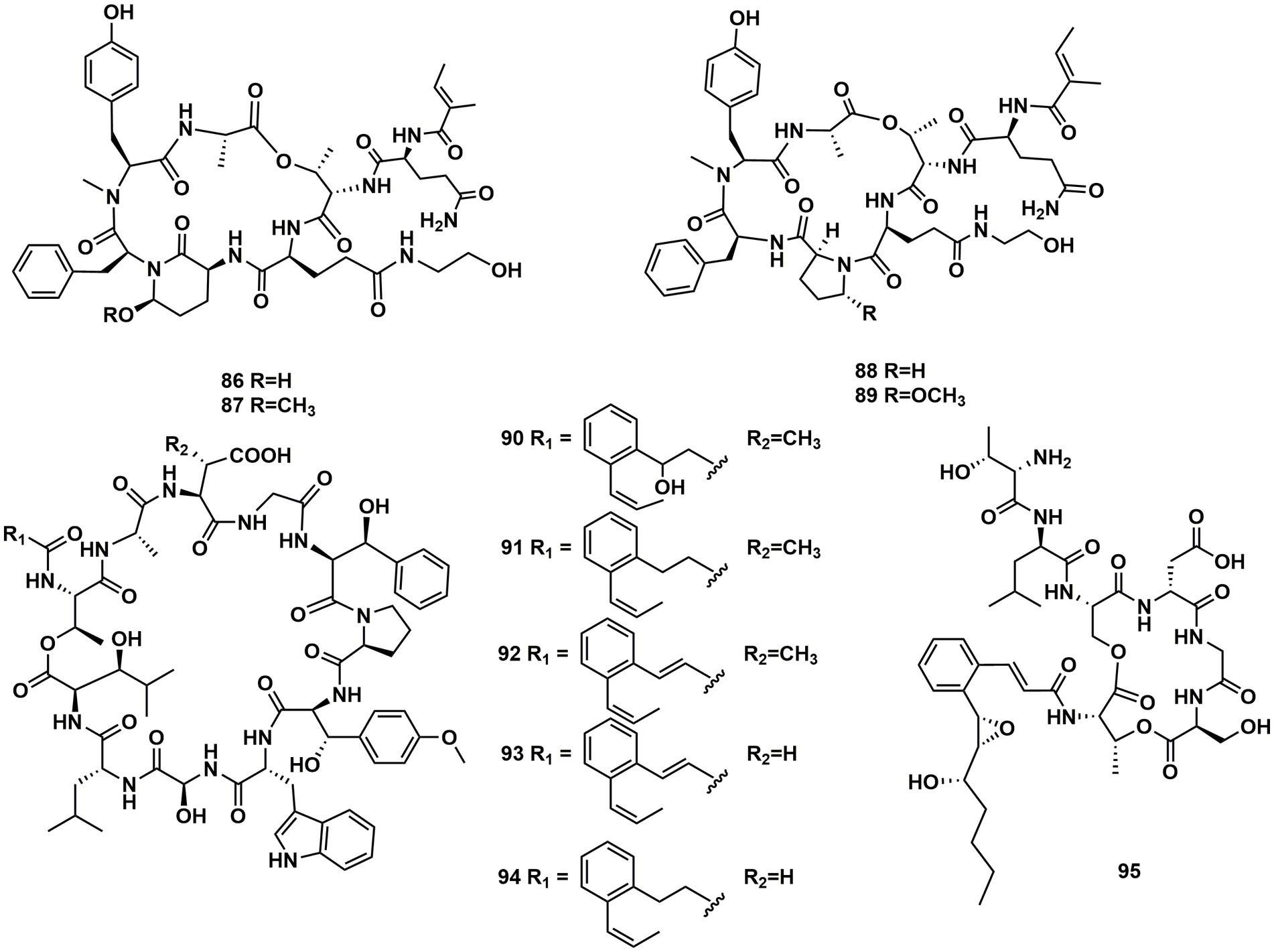

From cultures of the soil-derived Streptomyces sp., dinghupeptins A–D (86–89) were isolated. The 3-amino-6-hydroxypiperidone unit-containing compounds 86 and 87 demonstrated selective chymotrypsin inhibitory action, with IC50 values of 2.1 and 1.1 μM, respectively (Yang et al., 2018). Skyllamycins D (90) and E (91) were isolated from Lichen-sourced Streptomyces sp. KY11784, as well as three known ones skyllamycins A − C (92–94). Antibacterial tests showed that (Table 2), in comparison to previously reported congeners, skyllamycin D (90) had better activity against Bacillus. subtilis E168 (Bracegirdle et al., 2021). NC-1 (95), a cyclodepsipeptide containing a cinnamoyl side chain, was discovered in Streptomyces sp. FXJ1.172 that originated in red soil. 95 was evaluated to show moderate antimicrobial activity against Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) (Liu et al., 2016; Figure 13).

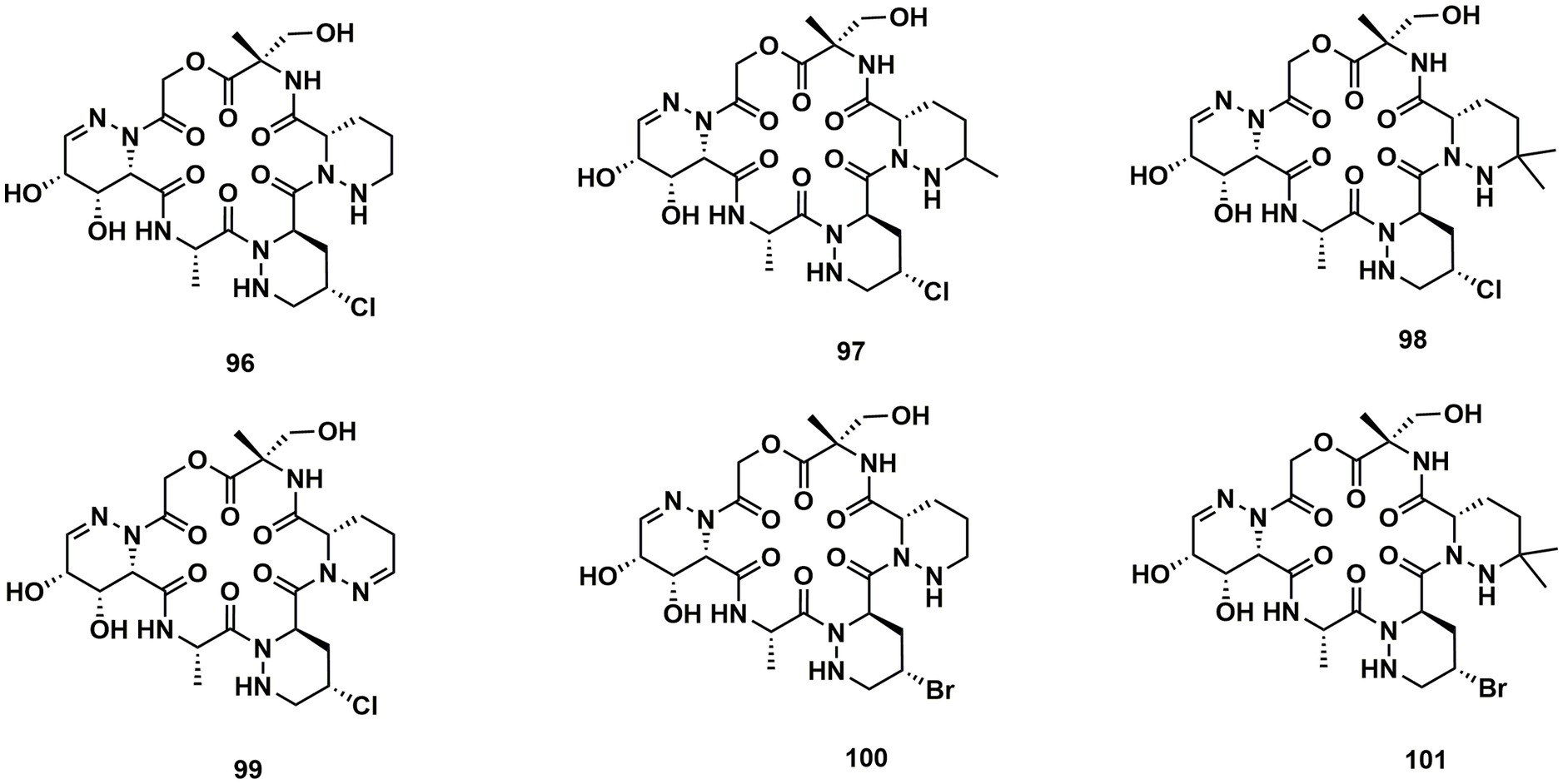

A group of cyclodepsipeptides that included piperazic acid, svetamycins A (96), B (97), C (98), D (99), F (100) and G (101), were separated from Streptomyces sp. DSM14386. With an IC80 value of 2 μg/mL, 101, the strongest antibacterial compound in this group of substances, prevented the development of Mycobacterium smegmatis (Dardić et al., 2017; Figure 14).

Cyclodepsipeptides from other bacteria

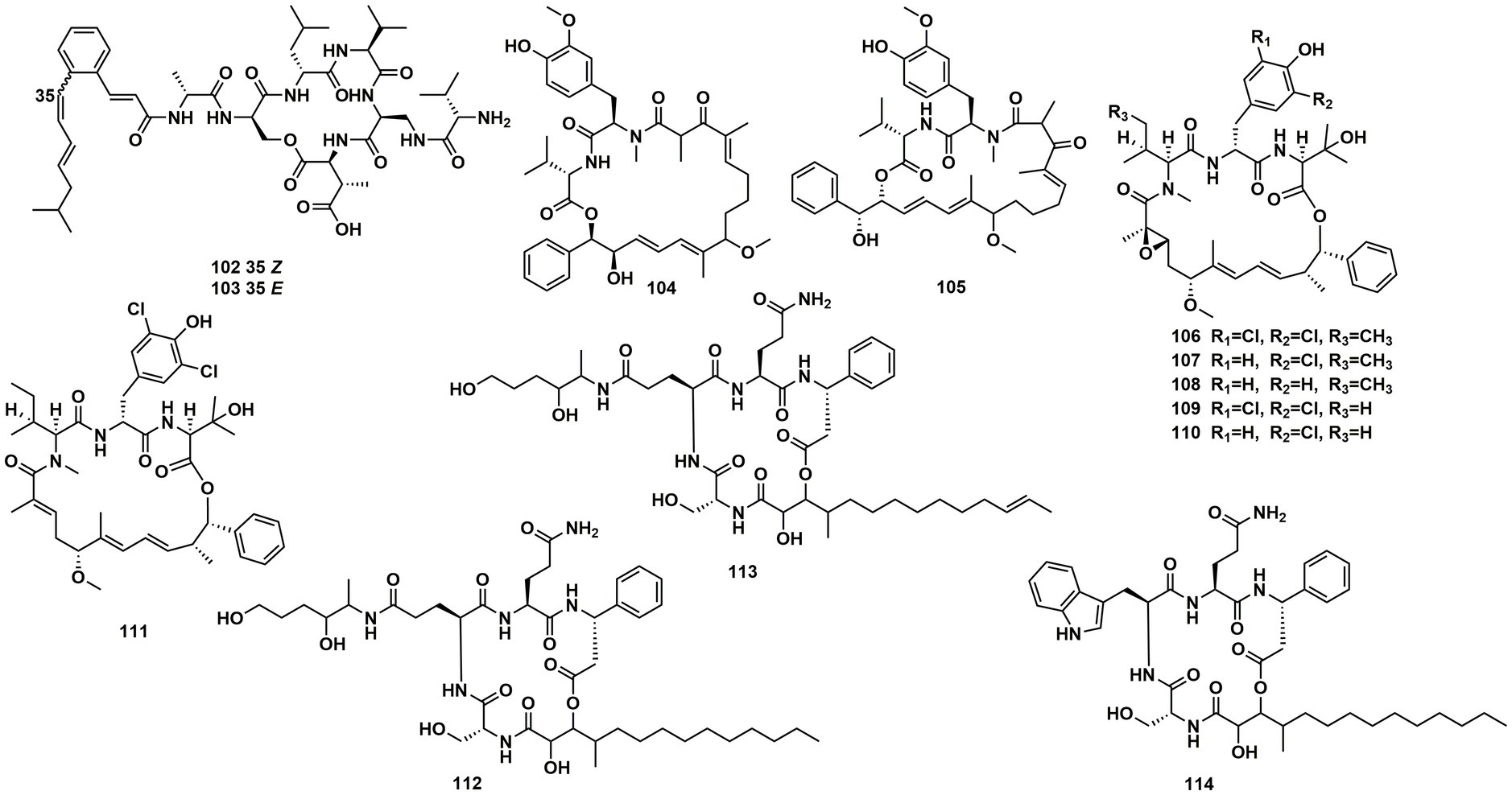

Spectroscopic analysis elucidated structures of two new compounds, coprisamides C and D (102 and 103), discovered from a dung beetle gut bacterium, Micromonospora sp. UTJ3. 102 exhibited a moderate inhibitory effect on the Mycobacterium tuberculosis mc2 6,230 strain (Shin et al., 2021). Aetheramides A (104), and B (105), which had IC50 values of 0.015 and 0.018 μM, respectively, showed strong inhibitory effects against HIV-1 (Table 3). Furthermore, 104 displayed cytotoxic activity with an IC50 value of 0.11 μM against the human HCT-116 (Plaza et al., 2012; Figure 15). Nannocystin A (106) was discovered from a myxobacterial genus, Nannocystis sp. The IC50 value for compound 106, which inhibited the growth of C. albicans, was 73 nM, indicating a strong antifungal activity. Besides 106, Nannocystis sp. also yielded nannocystin A1 (107), nannocystin A0 (108), nannocystin B (109), nannocystin B1 (110) and nannocystin Ax (111) (Hoffmann et al., 2015; Krastel et al., 2015). Alveolaride A (112), alveolaride B (113) and alveolaride C (114) were isolated from Microascus alveolaris strain PF1466. Alveolaride A (112) exhibited a potent inhibitory effect on the plant pathogens Zymoseptoria tritici, Ustilago maydis, and Pyricularia oryzae. Alveolaride C (114) was solely effective toward U. maydis, but alveolaride B (113) was effective toward both U. maydis and Z. tritici under in vitro conditions (Fotso et al., 2018; Figure 15).

Discussions

The chemical structures of cyclodepsipeptides, especially the absolute configurations, were complicated and difficult to determine, different methods were needed. Among them, Marfey’s method, modified Mosher’s method, and X-Ray diffraction analysis besides 1D-NMR and 2D-NMR (Wang et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022) were the best choices for determination of the configurations for those compounds. Moreover, the MS–MS fragment analysis was also of great use for judging its sequence of the amino acids (Chung et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2020).

As expected, an abundance of fungi and bacteria-derived cyclodepsipeptides were isolated, and most of them showed significant cytotoxic activities. It was suggested that the cyclic depsipeptide structure was of great importance for the biological activity, because in cytotoxicity assay, the linear homologs of the cyclohexadepsipeptide paecilodepsipeptide A were inactive (Hamann et al., 1996). In addition, the scope of bioactivity of cyclodepsipeptides spanned a range from cytotoxity, and anti-bacterial to anti-malarial activity. Thus, it was suggested that cyclodepsipeptides were desirable chemical species, and could be further applied as leading compounds in drug research.

Although most of the fungi and bacteria have been shown to be a rich source for discovering cyclodepsipeptides, the number of new cyclodepsipeptides was still limited. Conventional isolation method was time-consuming and inefficient, it was necessary to develop a more effective method to explore cyclodepsipeptide candidates. Fortunately, some studies have illustrated that the biosynthesis of cyclodepsipeptides were accomplished nonribosomally by cyclodepsipeptide synthetases (Bills et al., 2014; Du et al., 2014; Aleti et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2015), thus, targeted discovery of cyclodepsipeptides by genomic analysis became possible. By use of targeted isolation methods, such as genome mining as well as molecular networking method (Duncan et al., 2015; Paulo et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2021; Clements-Decker et al., 2022), should be paid more attention in the future in order to obtain those bioactive compounds more efficiently.

In addition, due to the small amount of cyclodepsipeptides from natural products, investigations on in vivo effects and on the detailed mechanism of the bioactivities were limited. To solve this problem, sufficient compound material was however required. Facing the problem, total synthesis and heterologous expression of genes or gene clusters in microbial hosts were two better ways, which were keys to access industrially and pharmaceutically relevant compounds in an economically affordable and sustainable manner (Stolze and Kaiser, 2013; Doi, 2014; Roderich et al., 2015).

Conclusion

In conclusion, this review gave an overview of as many as 114 natural cyclodepsipeptides isolated and identified from fungi and bacteria since 2010, among them, endophytic fungi of plant were the largest group of producers. The review enriched our knowledge about structural features of cyclodepsipeptides and their biological sources.

Author contributions

S-XL: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. S-YO-Y: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Y-FL: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. C-LG: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. S-YD: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. CL: Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. T-YY: Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Y-HP: Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aleti, G., Sessitsch, A., and Brader, G. (2015). Genome mining: prediction of lipopeptides and polyketides from Bacillus and related firmicutes. Comput. Struct. Biotec. 13, 192–203. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2015.03.003

Barthélemy, M., Elie, N., Genta-Jouve, G., Stien, D., Touboul, D., and Eparvier, V. (2021). Identification of antagonistic compounds between the palm tree Xylariale endophytic fungi and the phytopathogen Fusarium oxysporum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69, 10893–10906. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c03141

Bills, G., Li, Y., Chen, L., Yue, Q., Niu, X. M., and An, Z. Q. (2014). New insights into the echinocandins and other fungal non-ribosomal peptides and peptaibiotics. Nat. Prod. Rep. 31, 1348–1375. doi: 10.1039/C4NP00046C

Bracegirdle, J., Hou, P., Nowak, V. V., Ackerley, D. F., Keyzers, R. A., and Owen, J. G. (2021). Skyllamycins D and E, non-ribosomal cyclic depsipeptides from lichen-sourced Streptomyces anulatus. J. Nat. Prod. 84, 2536–2543. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c00547

Buckton, L. K., Rahimi, M. N., and McAlpine, S. R. (2021). Cyclic peptides as drugs for intracellular targets: the next frontier in peptide therapeutic development. Chemistry 27, 1487–1513. doi: 10.1002/chem.201905385

Chung, Y. M., El-Shazly, M., Chuang, D. W., Hwang, T. L., Asai, T., Oshima, Y., et al. (2013). Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, induces the production of anti-inflammatory cyclodepsipeptides from Beauveria felina. J. Nat. Prod. 76, 1260–1266. doi: 10.1021/np400143j

Clements-Decker, T., Rautenbach, M., Khan, S., and Khan, W. (2022). Metabolomics and genomics approach for the discovery of serrawettin W2 lipopeptides from Serratia marcescens NP2. J. Nat. Prod. 85, 1256–1266. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c01186

Dardić, D., Lauro, G., Bifulco, G., Laboudie, P., Sakhaii, P., Bauer, A., et al. (2017). Svetamycins A–G, unusual Piperazic acid-containing peptides from Streptomycessp. J. Org. Chem. 82, 6032–6043. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.7b00228

Doi, T. (2014). Synthesis of the biologically active natural product cyclodepsipeptides apratoxin a and its analogues. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 62, 735–743. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c14-00268

Du, Y. H., Wang, Y. M., Huang, T. T., Tao, M. F., Deng, Z. X., and Lin, S. J. (2014). Identification and characterization of the biosynthetic gene cluster of polyoxypeptin A, a potent apoptosis inducer. BMC Microbiol. 14, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-30

Duncan, K. R., Crüsemann, M., Lechner, A., Sarkar, A., Li, J., Ziemert, N., et al. (2015). Molecular networking and pattern-based genome mining improves discovery of biosynthetic gene clusters and their products from Salinispora species. Chem. Biol. 22, 460–471. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.03.010

El-Elimat, T., Raja, H. A., Day, C. S., McFeeters, H., McFeeters, R. L., and Oberlies, N. H. (2017). α-Pyrone derivatives, tetra/hexahydroxanthones, and cyclodepsipeptides from two freshwater fungi. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 25, 795–804. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.11.059

Fotso, S., Graupner, P., Xiong, Q., Gilbert, J. R., Hahn, D., Avila-Adame, C., et al. (2018). Alveolarides: antifungal peptides from microascus alveolaris active against phytopathogenic fungi. J. Nat. Prod. 81, 10–15. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00337

Ganaha, M., Yoshii, K., Ōtsuki, Y., Iguchi, M., Okamoto, Y., Iseki, K., et al. (2016). In vitro antitrypanosomal activity of the secondary metabolites from the mutant strain IU-3 of the insect pathogenic fungus Ophiocordyceps coccidiicola NBRC 100683. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 64, 988–990. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c16-00220

Guo, W. Q., Wang, S., Li, N., Li, F., Zhu, T. J., Gu, Q. Q., et al. (2018). Saroclides A and B, cyclic depsipeptides from the mangrove-derived fungus Sarocladium kiliense HDN11-112. J. Nat. Prod. 81, 1050–1054. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00644

Hamann, M. T., Otto, C. S., Scheuer, P. J., and Dunbar, D. C. (1996). Kahalalides: bioactive peptides from a marine mollusk Elysia rufescens and its algal diet Bryopsis sp. J. Org. Chem. 61, 6594–6600. doi: 10.1021/jo960877+

Haritakun, R., Sappan, M., Suvannakad, R., Tasanathai, K., and Isaka, M. (2010). An antimycobacterial cyclodepsipeptide from the entomopathogenic fungus Ophiocordyceps communis BCC 16475. J. Nat. Prod. 73, 75–78. doi: 10.1021/np900520b

Helaly, S. E., Ashrafi, S., Teponno, R. B., Bernecker, S., Dababat, A. A., Maier, W., et al. (2018). Nematicidal cyclic lipodepsipeptides and a xanthocillin derivative from a phaeosphariaceous fungus parasitizing eggs of the plant parasitic nematode Heterodera filipjevi. J. Nat. Prod. 81, 2228–2234. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.8b00486

Hoffmann, H., Kogler, H., Heyse, W., Matter, H., Caspers, M., Schummer, D., et al. (2015). Discovery, structure elucidation, and biological characterization of nannocystin a, a macrocyclic myxobacterial metabolite with potent antiproliferative properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 10145–10148. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411377

Ibrahim, S. R., Abdallah, H. M., Elkhayat, E. S., Al Musayeib, N. M., Asfour, H. Z., Zayed, M. F., et al. (2018). Fusaripeptide a: new antifungal and anti-malarial cyclodepsipeptide from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 20, 75–85. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2017.1320989

Isaka, M., Palasarn, S., Komwijit, S., Somrithipol, S., and Sommai, S. (2014). Pleosporin a, an antimalarial cyclodepsipeptide from an elephant dung fungus (BCC 7069). Tetrahedron Lett. 55, 469–471. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.11.063

Isaka, M., Palasarn, S., Supothina, S., Komwijit, S., and Luangsa-ard, J. J. (2011). Bioactive compounds from the scale insect pathogenic fungus Conoideocrella tenuis BCC 18627. J. Nat. Prod. 74, 782–789. doi: 10.1021/np100849x

Ishidoh, K., Kinoshita, H., Igarashi, Y., Ihara, F., and Nihira, T. (2014). Cyclic lipodepsipeptides verlamelin A and B, isolated from entomopathogenic fungus Lecanicillium sp. J. Antibiot. 67, 459–463. doi: 10.1038/ja.2014.22

Krastel, P., Roggo, S., Schirle, M., Ross, N. T., Perruccio, F., Aspesi, P. Jr., et al. (2015). Nannocystin A: an elongation factor 1 inhibitor from myxobacteria with differential anti-cancer properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 10149–10154. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505069

Langenfeld, A., Blond, A., Gueye, S., Herson, P., Nay, B., Dupont, J., et al. (2011). Insecticidal cyclodepsipeptides from Beauveria felina. J. Nat. Prod. 74, 825–830. doi: 10.1021/np100890n

Lemmens-Gruber, R., Kamyar, M., and Dornetshuber, R. (2009). Cyclodepsipeptides-potential drugs and lead compounds in the drug development process. Curr. Med. Chem. 16, 1122–1137. doi: 10.2174/092986709787581761

Li, J. T., Fu, X. L., Zeng, Y., Wang, Q., and Zhao, P. J. (2011). Two cyclopeptides from endophytic fungus Beauveria sp. Lr89 isolated from Maytenus hookeri. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 23, 667–669.

Li, X. J., Li, F. M., Xu, L. X., Li, L., and Peng, Y. H. (2021). Antifungal secondary metabolites of endophytic Fusarium sp. HU0174 from Celtis sinensis. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 33, 943–950.

Liang, M., Lyu, H. N., Ma, Z. Y., Li, E. W., Cai, L., and Yin, W. B. (2021). Genomics-driven discovery of a new cyclodepsipeptide from the guanophilic fungus Amphichorda guana. Org. Biomol. Chem. 19, 1960–1964. doi: 10.1039/D1OB00100K

Liu, M. H., Liu, N., Shang, F., and Huang, Y. (2016). Activation and identification of NC-1: a cryptic cyclodepsipeptide from red soil-derived Streptomyces sp. FXJ1. 172. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 3943–3948. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201600297

Liu, Q., Liu, Z. Y., Sun, C. L., Shao, M. W., Ma, J. Y., Wei, X. Y., et al. (2019). Discovery and biosynthesis of atrovimycin, an antitubercular and antifungal cyclodepsipeptide featuring vicinal-dihydroxylated cinnamic acyl chain. Org. Lett. 21, 2634–2638. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00618

Liu, Z. G., Sun, Y., Tang, M. Y., Sun, P., Wang, A. Q., Hao, Y. Q., et al. (2020). Trichodestruxins A–D: cytotoxic Cyclodepsipeptides from the endophytic FungusTrichoderma harzianum. J. Nat. Prod. 83, 3635–3641. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00808

Liu, J., Wang, B., Li, H. Z., Xie, Y. C., Li, Q. L., Qin, X. J., et al. (2015). Biosynthesis of the anti-infective marformycins featuring pre-NRPS assembly line N-formylation and O-methylation and post-assembly line C-hydroxylation chemistries. Org. Lett. 17, 1509–1512. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00389

Luo, M. N., Chang, S. S., Li, Y. H., Xi, X. M., Chen, M. H., He, N., et al. (2022). Molecular networking-based screening led to the discovery of a cyclic heptadepsipeptide from an endolichenic Xylaria sp. J. Nat. Prod. 85, 972–979. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c01108

Lv, F., Daletos, G., Lin, W., and Proksch, P. (2015). Two new cyclic depsipeptides from the endophytic fungus Fusarium sp. Nat. Prod. Commun. 10, 1667–1670. doi: 10.3390/molecules23010169

Moore, R. (1996). Cyclic peptides and depsipeptides from cyanobacteria: a review. J. Ind. Microbiol. 16, 134–143. doi: 10.1007/BF01570074

Negi, B., Kumar, D., and Rawat, D. S. (2017). Marine peptides as anticancer agents: a remedy to mankind by nature. Curr. Protein. Pept. Sc. 18, 885–904. doi: 10.2174/1389203717666160724200849

Nihei, K., Itoh, H., Hashimoto, K., Miyairi, K., and Okuno, T. (1998). Antifungal cyclodepsipeptides, W493 A and B, from Fusarium sp.: isolation and structural determination. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 62, 858–863. doi: 10.1271/bbb.62.858

Paulo, B. S., Sigrist, R., Angolini, C. F., and De Oliveira, L. G. (2019). New cyclodepsipeptide derivatives revealed by genome mining and molecular networking. ChemistrySelect 4, 7785–7790. doi: 10.1002/slct.201900922

Plaza, A., Garcia, R., Bifulco, G., Martinez, J. P., Hüttel, S., Sasse, F., et al. (2012). Aetheramides A and B, potent HIV-inhibitory depsipeptides from a myxobacterium of the new genus “Aetherobacter”. Org. Lett. 14, 2854–2857. doi: 10.1021/ol3011002

Rivera-Chávez, J., El-Elimat, T., Gallagher, J. M., Graf, T. N., Fournier, J., Panigrahi, G. K., et al. (2019). Delitpyrones: α-Pyrone derivatives from a freshwater Delitschia sp. Planta Med. 85, 62–71. doi: 10.1055/a-0654-5850

Roderich, D. S., Thomas Schweder, S., Sophia, Z., and Jana, K. (2015). Bacillus subtilis as heterologous host for the secretory production of the non-ribosomal cyclodepsipeptide enniatin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99, 681–691. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-6199-0

Shin, Y. H., Ban, Y. H., Kim, T. H., Bae, E. S., Shin, J., Lee, S. K., et al. (2021). Structures and biosynthetic pathway of coprisamides C and D, 2-alkenylcinnamic acid-containing peptides from the gut bacterium of the carrion beetle Silpha perforata. J. Nat. Prod. 84, 239–246. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00864

Singh, S. B., Ondeyka, J., Harris, G., Herath, K., Zink, D., Vicente, F., et al. (2013). Isolation, structure, and biological activity of phaeofungin, a cyclic lipodepsipeptide from a Phaeosphaeria sp. using the genome-wide Candida albicans fitness test. J. Nat. Prod. 76, 334–345. doi: 10.1021/np300704s

Sivanathan, S., and Scherkenbeck, J. (2014). Cyclodepsipeptides: a rich source of biologically active compounds for drug research. Molecules 19, 12368–12420. doi: 10.3390/molecules190812368

Soe, T. W., Han, C., Fudou, R., Kaida, K., Sawaki, Y., Tomura, T., et al. (2019). Clavariopsins C–I, antifungal cyclic depsipeptides from the aquatic hyphomycete Clavariopsis aquatica. J. Nat. Prod. 82, 1971–1978. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b00366

Son, S., Ko, S. K., Jang, M., Lee, J. K., Ryoo, I. J., Lee, J. S., et al. (2015). Ulleungamides a and B, modified α, β-dehydropipecolic acid containing cyclic depsipeptides from Streptomyces sp. KCB13F003. Org. Lett. 17, 4046–4049. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01969

Stolze, S. C., and Kaiser, M. (2013). Case studies of the synthesis of bioactive cyclodepsipeptide natural products. Molecules 18, 1337–1367. doi: 10.3390/molecules18021337

Umeyama, A., Takahashi, K., Grudniewska, A., Shimizu, M., Hayashi, S., Kato, M., et al. (2014). In vitro antitrypanosomal activity of the cyclodepsipeptides, cardinalisamides A–C, from the insect pathogenic fungus Cordyceps cardinalis NBRC 103832. J. Antibiot. 67, 163–166. doi: 10.1038/ja.2013.93

Wang, F. Q., Jiang, J., Hu, S., Ma, H. R., Zhu, H. C., Tong, Q. Y., et al. (2017). Secondary metabolites from endophytic fungus Chaetomium sp. induce colon cancer cell apoptotic death. Fitoterapia 121, 86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2017.06.021

Wang, Y. J., Liu, C. Y., Wang, Y. L., Zhang, F. X., Lu, Y. F., Dai, S. Y., et al. (2022). Cytotoxic cyclodepsipeptides and cyclopentane derivatives from a plant-associated fungus Fusarium sp. J. Nat. Prod. 85, 2592–2602. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.2c00555

Wang, J., Zhang, D. M., Jia, J. F., Peng, Q. L., Tian, H. Y., Wang, L., et al. (2014). Cyclodepsipeptides from the ascocarps and insect-body portions of fungus Cordyceps cicadae. Fitoterapia 97, 23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.05.010

Wang, Z. F., Zhang, W., Xiao, L., Zhou, Y. M., and Du, F. Y. (2020). Characterization and bioactive potentials of secondary metabolites from Fusarium chlamydosporum. Nat. Prod. Res. 34, 889–892. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2018.1508142

Wei, Q., Bai, J., Yan, D. J., Bao, X. Q., Li, W. T., Liu, B. Y., et al. (2021). Genome mining combined metabolic shunting and OSMAC strategy of an endophytic fungus leads to the production of diverse natural products. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 11, 572–587. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.07.020

Yang, L., Li, H. X., Wu, P., Mahal, A., Xue, J. H., Xu, L. X., et al. (2018). Dinghupeptins A–D, chymotrypsin inhibitory cyclodepsipeptides produced by a soil-derived Streptomyces. J. Nat. Prod. 81, 1928–1936. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b01009

Keywords: cyclodepsipeptide, fungi, bacteria, antimicrobial, biological activity

Citation: Liu S-X, Ou-Yang S-Y, Lu Y-F, Guo C-L, Dai S-Y, Li C, Yu T-Y and Pei Y-H (2023) Recent advances on cyclodepsipeptides: biologically active compounds for drug research. Front. Microbiol. 14:1276928. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1276928

Edited by:

Guangshun Wang, University of Nebraska Medical Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Fengyu Du, Qingdao Agricultural University, ChinaShivankar Agrawal, Indian Council of Medical Research, India

Copyright © 2023 Liu, Ou-Yang, Lu, Guo, Dai, Li, Yu and Pei. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chang Li, bGljaGFuZzY2MUAxMjYuY29t; Tian-Yi Yu, dGlhbm9vMzAwMEAxNjMuY29t; Yue-Hu Pei, cGVpeXVlaEB2aXAuMTYzLmNvbQ==

Si-Xuan Liu

Si-Xuan Liu Si-Yi Ou-Yang1

Si-Yi Ou-Yang1 Chang Li

Chang Li Yue-Hu Pei

Yue-Hu Pei