95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 17 November 2022

Sec. Food Microbiology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.997940

This article is part of the Research Topic Probiotics for Nutrition Research in Health and Disease View all 15 articles

Oxidative stress is caused by an imbalance between prooxidants and antioxidants, which is the cause of various chronic human diseases. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) have been considered as an effective antioxidant to alleviate oxidative stress in the host. To obtain bacterium resources with good antioxidant properties, in the present study, 113 LAB strains were isolated from 24 spontaneously fermented chili samples and screened by tolerance to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Among them, Lactobacillus plantarum GXL94 showed the best antioxidant characteristics and the in vitro antioxidant activities of this strain was evaluated extensively. The results showed that L. plantarum GXL94 can tolerate hydrogen peroxide up to 22 mM, and it could normally grow in MRS with 5 mM H2O2. Its fermentate (fermented supernatant, intact cell and cell-free extract) also had strong reducing capacities and various free radical scavenging capacities. Meanwhile, eight antioxidant-related genes were found to up-regulate with varying degrees under H2O2 challenge. Furthermore, we evaluated the probiotic properties by using in vitro assessment. It was showed that GXL94 could maintain a high survival rate at pH 2.5% or 2% bile salt or 8.0% NaCl, live through simulated gastrointestinal tract (GIT) to colonizing the GIT of host, and also show higher abilities of auto-aggregation and hydrophobicity. Additionally, the usual antibiotic susceptible profile and non-hemolytic activity indicated the safety of the strain. In conclusion, this study demonstrated that L. plantarum GXL94 could be a potential probiotic candidate for producing functional foods with antioxidant properties.

Probiotics are defined as “live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts, confer health benefits to the host” (Hill et al., 2014). The majority of probiotics belong to the lactic acid bacteria (LAB) group. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are a diverse group of gram-positive bacteria that widely exist in nature including plants, animals and fermented foods, which was generally recognized as safe (GRAS) microorganisms, have a wide range of industrial applications, such as food fermentation, pharmaceutical, chemical and other industries (Feng and Wang, 2020). Lactobacillus, Bifidobacteria, and Streptococcus are the most famous genera that are described (Kiani et al., 2021). Lactobacillus is a fundamental group of LAB and is generally regard as safe. It is also the most common LAB strains in fermented foods (Das et al., 2016). The therapeutic effect of Lactobacillus fermented milk on gastrointestinal diseases has been found for a long time, and increasing experimental evidences in recent years have also made human understanding of Lactobacillus to a new height (Kok and Hutkins, 2018). Numerous studies have shown that some Lactobacillus strains benefit the host by improving balancing intestinal microbiota (Schnupf et al., 2018; He et al., 2020), regulating immunity (Galdeano and Perdigón, 2006; Håkansson et al., 2019), reducing cholesterol (Ebel et al., 2014; Fuentes et al., 2016), alleviating diabetes (Lee et al., 2013; Li et al., 2019), regulating lactase activity (Hajare and Bekele, 2017), and producing vitamins (Greppi et al., 2017; Li et al., 2017). As a symbiotic organism, it may play an important role in the host health maintenance and disease control. Oral Lactobacillus to support physiological and physical functions, thereby reducing the risk of disease or shortening the duration or severity of disease, has become an important means of treatment or prevention of disease. There are numerous preclinical and clinical studies confirming the gastrointestinal benefits of Lactobacillus in healthy individuals and in a wide range of both minor and serious health conditions (de Simone, 2019). As a result, sales of probiotic-based health products, including pharmaceuticals, dietary supplements, and functional foods, are growing rapidly. Meanwhile, Lactobacillus has become the most common probiotic preparation in the market, with good development prospects (Mazzantini et al., 2021).

Adverse environments such as high or low temperature, low pH, bile salts, oxygen, or limited nutrition can cause stress inducing that affect LAB survival during processing and storage, as well as survival, proliferation, and function in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT; Bron and Kleerebezem, 2011; Mills et al., 2011). Among them, oxidative stress is critical important, which can greatly affect the survival ability of LAB. High oxygen levels can lead to the formation and accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide anions (O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (HO•), and cause cell damage, affecting their physiological functions (Amaretti et al., 2013). Therefore, improving the oxidative stress ability of LAB cells is crucial to ensure high bacterial activity in storage and gastrointestinal tract (Feng and Wang, 2020).

In addition, a great quantity of researches reported that some LAB strains have good antioxidant potential in recent years and can be used as a high-quality natural antioxidant (Mishra et al., 2015). Ingestion of these probiotics and their fermented products can help remove ROS from the host gut, reduce the risk of oxidative damage to host cells and the incidence of chronic diseases (Amaretti et al., 2013). For instance, pretreatment with L. plantarum ZLP001 could protected IPEC-J2 cells against H2O2-induced oxidative damage as indicated by cell viability assays and significantly alleviated apoptosis elicited by H2O2 (Wang et al., 2021). Therefore, the antioxidant capacity of LAB is gradually attracting people’s attention. Various methodologies have been used to assess the antioxidative properties of LAB in vitro and in vivo. The common assays in vitro were based on determining O2 tolerance (Li et al., 2010), resistance to H2O2 (Bchmeier et al., 1997), the reducing power (Tang et al., 2017), radical production and scavenging capacity including ABTS scavenging assay, DPPH scavenging assay (Mu et al., 2019), superoxide radical scavenging assay (Balcazar et al., 2007), hydroxyl radical scavenging assay (Gao et al., 2013), and oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) assay (Persichetti et al., 2014). The in vivo experiments involved establishing animal models, such as the D-galactose-induced aging mouse model (Tang et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2018) and UV-irradiated hairless mouse model (Ishii et al., 2014), and were based on determining physiological and biochemical indexes of experimental animal blood or tissues to evaluate the antioxidants’ AOCs. At present, plenty of LAB strains with antioxidant effects through these experiments was screened out, such as L. plantarum 21, Lactobacillus sp. SBT-2028, L. fermentum ME-3, L. plantarum AR113 and L. casei KCTC 3260 (Kaizu et al., 1993; Lee et al., 2005; Ou et al., 2009; Achuthan et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2020). However, the antioxidant mechanisms of probiotic LAB are complex, and different strains use different mechanisms. It has been suggested that LAB may play antioxidant roles through scavenging ROS, chelating metals, increasing antioxidant enzymes levels, and modulating the microbiota (Feng and Wang, 2020). It is necessary to study the antioxidant properties of different strains for systematically revealing the antioxidant mechanism of LAB.

L. plantarum strain GXL94 with potential antioxidant capacity was isolated by hydrogen peroxide tolerance assay of 113 LAB strains obtained from fermented food. In the present study, we report the in vitro evaluation of probiotic properties and antioxidant activity of this isolate. The purpose of this research was to screen the functional LAB with good quality and lay a foundation for rational development and utilization of LAB.

Twenty-four samples of traditional fermented chili were collected from the domestic producers in Guangxi province in China. These samples were transferred to the laboratory and stored at refrigerator 4°C. The samples were enriched by adding 1% volume to 50 ml of sterile de Man Rogosa Sharpe (MRS) broth and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. 100 μl of each sample were spread over solidified MRS medium and incubated 24 h at 37°C. Then, five single colonies with distinct morphology were picked from each sample and subjected to initial morphological and biochemical tests. One hundred and thirteen cultures were obtained in total and they were identified using the 16S rDNA sequences. The genomic DNA of the strain was extracted and then performed PCR amplification with universal primers. Finally, the PCR product was recovered and sequenced. The sequencing results came from the Changsha Qingke Biological Co., Ltd. Sequencing results were compared on the NCBI website for homology comparison. All strains were stored in de Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) broth with 40% glycerol at −80°C and isolated on MRS agar plates. Before all experiment, they were transferred three times for high activity in MRS broth after activated at 37°C for 16 h.

The previously reported method was used with some modifications (Bchmeier et al., 1997). The overnight cultures were adjusted to the same bacterial concentration and inoculated at 1% v/v into MRS broth containing 13 mM H2O2. After incubation at 37°C for 2 h, the cultures were plated onto MRS agar and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. The bacterial colonies were counted.

Three LAB strains were harvested by centrifugation after cultured for 18 h. GXL94, GXL50, SCL43 cells were resuspended and cultivated at 37°C for 2 h in fresh sterilized MRS broth containing different concentrations of H2O2 (0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, and 22 mM) after adjusted OD600 to 0.80. Plate count method was used to count the LAB cells immediately after cultivated. The survival rate was calculated according to Guo et al. (2009).

To analyze the biomass proliferation, pure cultures were inoculated (3%, v/v) into MRS broth supplemented with different concentrations of H2O2 (1.0, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 mM) and incubated at 37°C for 60 h. The control medium contained no H2O2. Every 1 h, the plate was shaken briefly, and the OD600 was measured by microplate reader.

Lactobacillus plantarum GXL94 activated was inoculated (3%, v/v) in MRS broth containing different concentrations of H2O2 (0, 2.0, and 3.0 mM), and the LAB cells were harvested at different phase (lag phase, mid-logarithmic phase, primary stationary phase or middle-stationary phase) for RNA extraction. The total RNA of LAB cells were extracted and reversed into cDNA. These cDNAs were used as the template for determined antioxidant related gene expression level. The primers used were according to previous reported (Tang et al., 2017) and 16S rRNA was used as a house-keeping gene. The real-time PCR data was analyzed by using the 2−ΔΔCT assay and expressed as n-fold change relative to the experimental control (0 mM H2O2).

GXL94 was cultured in MRS broth at 37°C and the intact cells and fermented supernatant were harvested by centrifugation (6,000 g for 10 min at 4°C) after incubation for 18 h. The cells were washed three times with isotonic saline (0.9%) and resuspended in an equal volume of isotonic saline. The cell pellet was adjusted to 1 × 1010 CFU/ml. Cell-free extracts were obtained from cell suspensions containing 1 × 1010 CFU/ml that were subjected to ultrasonic disruption (ten 5-s strokes at 0°C with 5-s intervals, 10 min; Scientz-IID, China) and centrifuged (6,000 g for 10 min at 4°C) to remove the cell debris. In vitro antioxidative activities of these bacterial samples were evaluated in terms of the scavenging rates of 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH•), superoxide anion, 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid; ABTS•), hydroxyl radicals and superoxide anion radical as described (Tang et al., 2017; Mu et al., 2019). The total reducing power assay was performed according to a reported method (Tang et al., 2017), and ascorbic acid was used as the standard to determine the reducing activity.

The LAB strains were inoculated (2%, v/v) into MRS broth and the cells were harvested by centrifugation after cultured for 18 h. Then the collected cells were treated with different initial pH (2.5, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0), various bile concentration (0.3%–2%, w/v) or various sodium chloride (NaCl) concentration (2.0%–8.0%, w/v) for 3 h, the survival rates were measured after treatments. The viable count before incubation was measured as control (CK).

Survival to simulated gastrointestinal tract (GIT) conditions was evaluated according to the previous study (Lin et al., 2018). Intact cells (OD600 = 1.0) were resuspended in simulated gastric juice (SGJ:25 mM NaCl, 7 mM KCl, 45 mM NaHCO3, 3 g/l pepsin, pH 3.0) and incubated at 37°C for 3 h at 200 rpm. SGJ-treated cells were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 ×g for 5 min at 4°C), resuspended in equal volume of simulated pancreatic juice (0.15 g/100 ml bile salt, 1 g/L trypsin, pH 8.0), and incubated at 37°C for 3 h at 200 rpm. The cells incubated in normal saline were used as controls. The survivors were counted by pour plating on MRS agar (incubation at 37°C for 48 h).

The auto-aggregation ability was performed according to Lin et al. (2020). The stain of LAB cultured for 18 h were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 10 min at 4°C). The sediment was re-suspended in sterile normal saline and adjusted to 109 CFU/ml after washed thrice with sterile normal saline. Next, the suspensions of LAB were incubated at 37°C for 5 h. The optical density at 600 nm of upper layer suspension was measured at 0, 1, and 5 h by a UV spectrophotometer without hanging the microbial suspension. Auto-aggregation ability was calculated as follows: Auto-aggregation ability (%) = (1 − At/A0) × 100%.

Where At is OD600 at 1, 3, or 5 h, and A0 is OD600 at 0 h.

The co-aggregation ability was performed according to Lin et al. (2020) with modifications. The strain of LAB and E. coli O157: H7 were harvested as described above. The LAB and E. coli O157:H7 cells were adjusted to 0.25 and 0.60 at OD600 after washed three times with normal saline, respectively. Equal volumes (5 ml) of different LAB and E. coli cells suspension were mixed together by vortexing for 10 s. The absorbance (Amix) of upper layer of the suspension at 600 nm was measured after incubation at 37°C for 5 h. The percentage of co-aggregation was calculated as follows:

Where A1 and A2 represent absorbance of the two strains at 0 h, respectively. Amix represent absorbance of the mixture after 5 h of incubation.

The cell surface hydrophobicity of LAB was determined according to previous report with some modifications. The method for preparing the cell suspensions was the same as that in auto-aggregation assay. The mixture of LAB cells and xylene in equal volumes (2 ml) was incubated at room temperature (25°C) for 30 min after mixed by vortexing for 3 min. The adherence of LAB to hydrocarbons was calculated as follows:

Where A0 is OD600 before treatment with xylene, and At is the OD600 of the aqueous phase after treatment with xylene.

Antibiotic susceptibility of LAB strains was evaluated using the disk diffusion method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (Ahire et al., 2021). Susceptibility to the following 10 antibiotics was measured: 5 mcg of ciprofloxacin, and rifampicin; 10 mcg of ampicillin, gentamicin, and penicillin G; 15 mcg of erythromycin; 30 mcg of tetracycline, chloramphenicol, vancomycin, and kanamycin. LAB strains (1 × 108 CFU/ml) were spread on MRS agar plate, and antibiotic disks were placed on these plates under sterile conditions. After incubation at 37°C for overnight, the diameter of clear zones surrounding the disks was measured in millimeters (mm).

Hemolytic activity was performed as described by Ahire et al. (2021) with some modifications. Overnight grown culture of L. plantarum GXL94 was streaked on 7% defibrinated sheep blood agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. After incubation, the plates were observed for α-hemolysis (dark and greenish zones), β-hemolysis (lightened-yellow or transparent zones), and γ-hemolysis (no change or no zones).

The results were expressed as mean ± standard error. All experiments were carried out in triplicate. The procedure univariate in SAS was used to analyze data on relative expression value of each gene between different treatments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student’s t test were used to test the significant differences (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001) of means.

In this study, three cultures exhibited a moderate-to-strong resistance to H2O2. L. plantarum GXL94 and GXL50 was the most resistant strain against H2O2 with more than 100 CFU in the plate. Lactobacillus pentosus SCL43 was less tolerance than GXL94 and GXL50, however it also showed a certain tolerance to H2O2 (Table 1). Thus, these three strains were chosen to examine the tolerance to different concentration of H2O2.

The tolerate ability of GXL94, GXL50 and SCL43 to different concentrations of H2O2 were presented in Table 2. The survival rate of three strains were decreased with the concentration of H2O2 increasing. The survival rates were over 50% at 14 mM H2O2 for GXL94 or GXL50 and at 12 mM H2O2 for SCL43. When concentration of H2O2 up to 22 mM, there was still a survival rate of 19.64% for GXL94. However, at the same concentration of H2O2, there was no viable LAB colonies for GXL50 and SCL43 after cultivated for 2 h. This result indicated that strain GXL94 possessed a stronger antioxidant property.

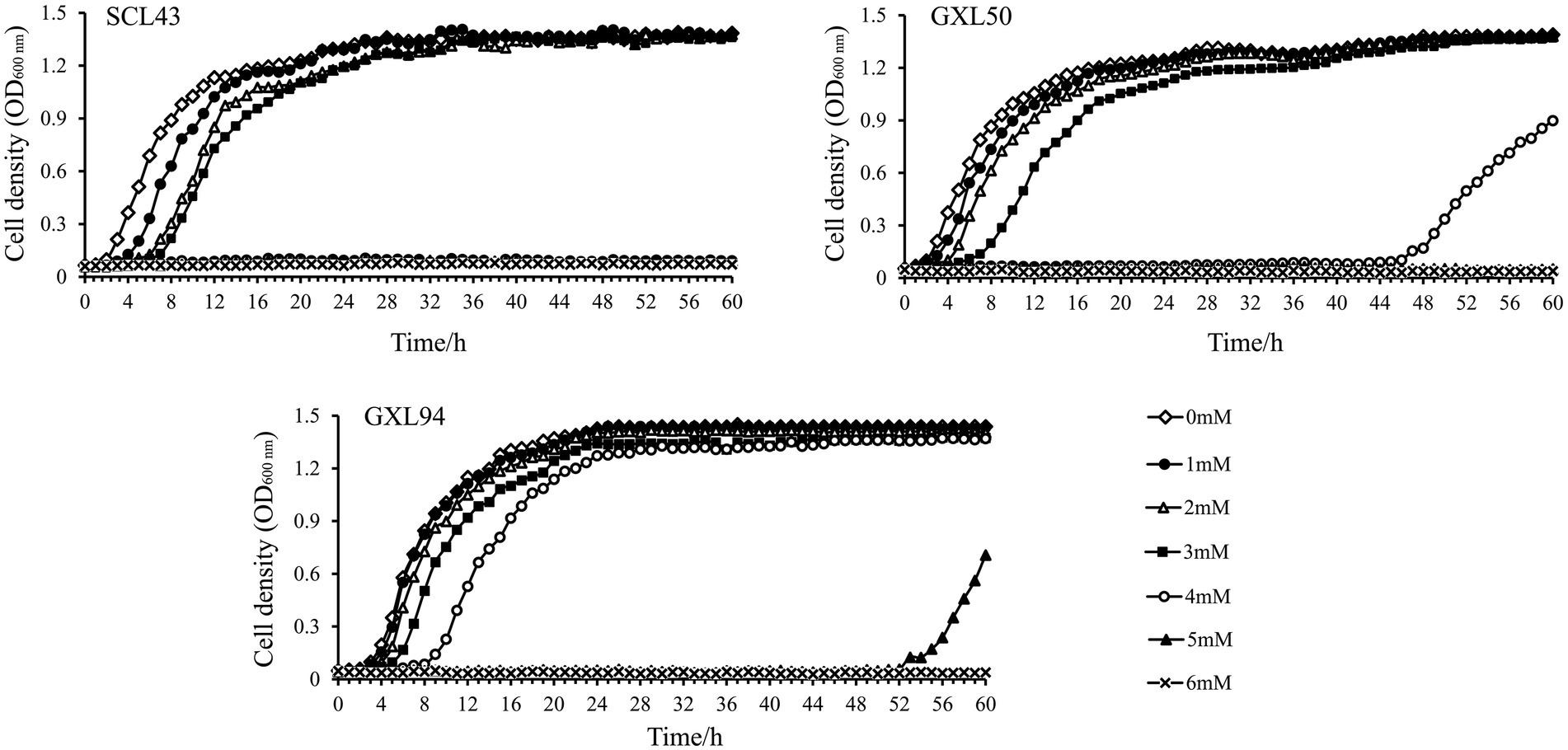

As mentioned above, H2O2 could induced oxidative stress of LAB. The growth of SCL43, GXL50 and GXL94 was inhibited by H2O2 as shown in Figure 1. The addition of H2O2 inhibited the growth and the lag phase was obviously elongated with the concentration of H2O2 increasing, which indicating that the presence of H2O2 cause bacterial oxidative damage. The further results showed that the growth inhibition of GXL94 in the range from 0 to 5 mM, and the growth was ceased as concentration amount to 6 mM H2O2. These results showed that GXL94 could survived the challenge of H2O2 up to 5 mM, higher than SCL43, GXL50 and other strains reported before.

Figure 1. Growth density of Lactobacillus pentosus SCL43, Lactobacillus plantarum GXL50 and GXL94 under oxidative stress. Experiments were conducted in MRS containing different concentrations of H2O2 (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 mM).

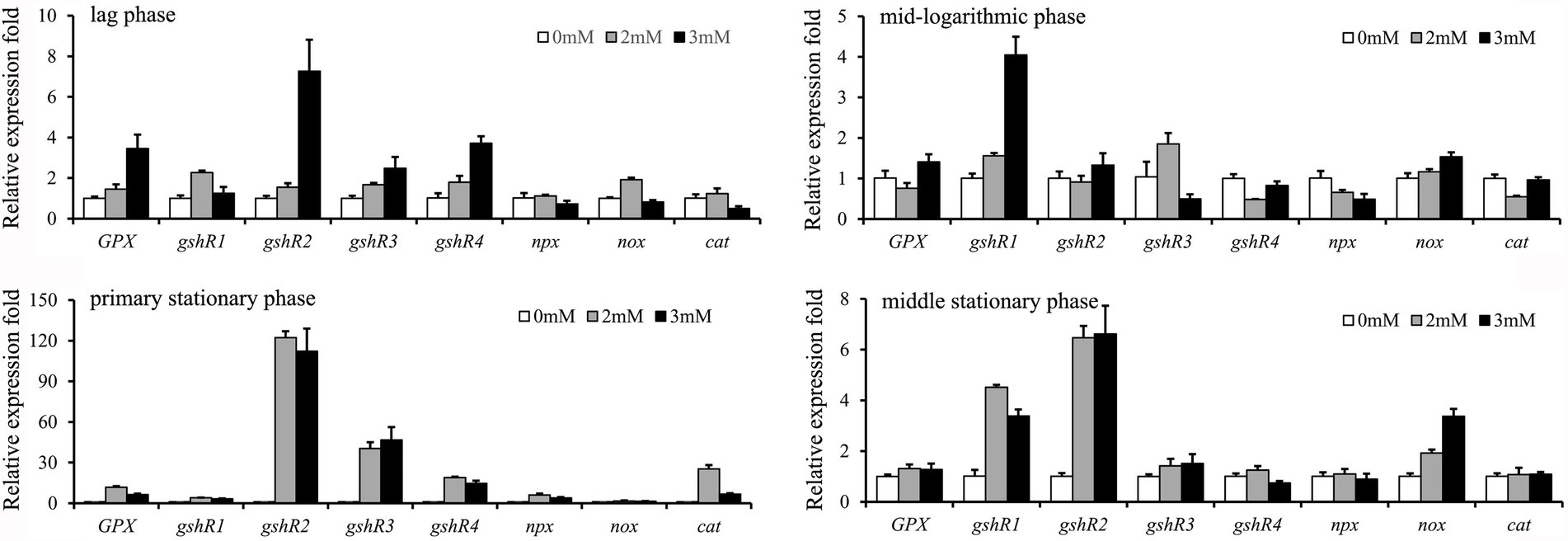

Relative expression levels of eight antioxidant-related genes were detected when exposed to different concentrations of H2O2 (Figure 2). The result showed that the expression levels of four genes including GPX, gshR2, gshR3, and gshR4 in GXL94 at lag phase were increased with increasing of H2O2 concentration, and shown positive correlation, however gshR1, npx, cat, and nox gene with no apparent correlation between H2O2 and expression levels. The expression levels of gshR1 and nox at the mid-logarithmic phase were positive correlation with the increasing of H2O2 concentration, while the genes expression levels of npx was decreased with the increasing H2O2 concentration, moreover there are no apparent correlation between H2O2 and mRNA level of other six genes. At primary stationary phase, all of eight antioxidant-related genes were significantly upregulated with H2O2 treatment, but they were no apparent correlation. At middle stationary phase, the expression level of gshR1, gshR3 and nox were significantly induced, while only the gene nox expression level showed an apparent correlation with H2O2 concentration.

Figure 2. Effects of the addition of hydrogen peroxide on the expression of 8 antioxidant-related genes in Lactobacillus plantarum GXL94. The graphs show the relative mRNA levels of 8 genes of cells grown in MRS medium with different concentrations of hydrogen peroxide at the lag phase, mid-logarithmic phase, primary stationary phase and middle stationary phase.

Among the induced transcription of eight genes related to antioxidation at primary stationary phase, expression of GPX was increased by 11.73-fold and 6.26-fold under 2.0 mM and 3.0 mM H2O2 challenge, respectively. Expression level of gshR1 was increased by 3.99-fold and 3.22-fold under 2.0 mM and 3.0 mM H2O2 challenge, respectively. The expression level of gshR2 was increased by 122.28-fold and 112.22-fold treated with 2.0 mM and 3.0 mM H2O2, respectively. In addition, gshR3 and gshR4 mRNA expression was elevated by 40.32-fold/18.86-fold and 46.71-fold/14.67-fold in response to the treatment with 2.0 mM and 3.0 mM H2O2. The cumulative values of the eight genes’ expression at primary stationary phase were largest of the four cultivation stages, which indicate that GXL94 exhibited higher antioxidant activity in the primary stationary, the GSH system was supposed to have played a major role in antioxidant activity.

The antioxidant mechanisms of probiotic LAB are complex, and different strains use different mechanisms. Various approaches have to be combined in order to identify and characterize the antioxidant activity of LAB. In this study, five commonly used antioxidant indexes of GXL94 in vitro were analyzed (Table 3).

Reducing activity of different samples of the fermentate of GXL94 was measured and expressed as an equivalent amount of ascorbic acid. The cell-free extract exhibited the stronger reducing activity (262.88 ± 12.30 μmol/L ascorbic acid equivalent) than the intact cells (185.66 ± 5.94 μmol/L ascorbic acid equivalent).

Scavenging of DPPH free radical is attributed to the hydrogen donating ability of antioxidants and is routinely used for antioxidant assay. Experiment result indicated that the fermented supernatant (95.98% ± 1.59%) and intact cells (83.82% ± 0.71%) of L. plantarum GXL94 exhibited more stronger DPPH scavenging ability compared to the cell-free extract (38.84% ± 1.93%; p < 0.05).

ABTS radical cation-scavenging activity was also an important index for antioxidant capacity analysis. In this study, ABTS scavenging ability was evaluated, and the result showed that the intact cells and cell-free extract exhibited a high scavenging activity, with ratios at 89.47% ± 0.36% and 89.61% ± 0.31%, respectively (Table 2). However, which were still slightly weaker than fermented supernatant (94.63% ± 0.54%).

Fenton reaction was used to measure the scavenging activities of hydroxyl radicals. The fermented supernatant (88.47% ± 0.32%) and cell-free extract (86.01% ± 0.28%) demonstrated a significantly higher scavenging capacity, compared to that of intact cells (61.43% ± 0.82%)(p < 0.05).

Through the improved pyrogallol autoxidation method, it was found that all of samples exhibited •O2−-scavenging activity, and the clearance rate of fermentation supernatant was highest, reached 34.41% ± 1.4%. In conclusion, L. plantarum GXL94 has a great antioxidant activity in vitro, and has promising antioxidant potentials in therapeutic benefits for human health.

Tolerances to low acid and high bile stresses are significant properties for any potential probiotic bacteria. The abilities of LAB to tolerate the pH and bile salt were presented in Figure 3. The gradual decreased survival of L. plantarum GXL94 (pH 5.0 98.07%; pH 4.0 98.04%; pH 3.0 97.8%; pH 2.5 96.7%) was noticed when the cells were incubated at different pHs as compared with control (Figure 3A). Moreover, a similar decreased pattern (97.34%; 97.09%; 95.37%; 95.09%) was observed with the concentration of bile salt treatment increases. Besides this, the viable cells of GXL94 was increased under the condition of 2% NaCl due to proliferation, but decreased significantly as osmotic pressure increasing (4%: 97.4%; 6%: 96.5%; 8%: 95.4%) as compared with the control (Figure 3). These results indicated that GXL94 has good tolerance to low acid and high concentration of bile salts and NaCl treatment.

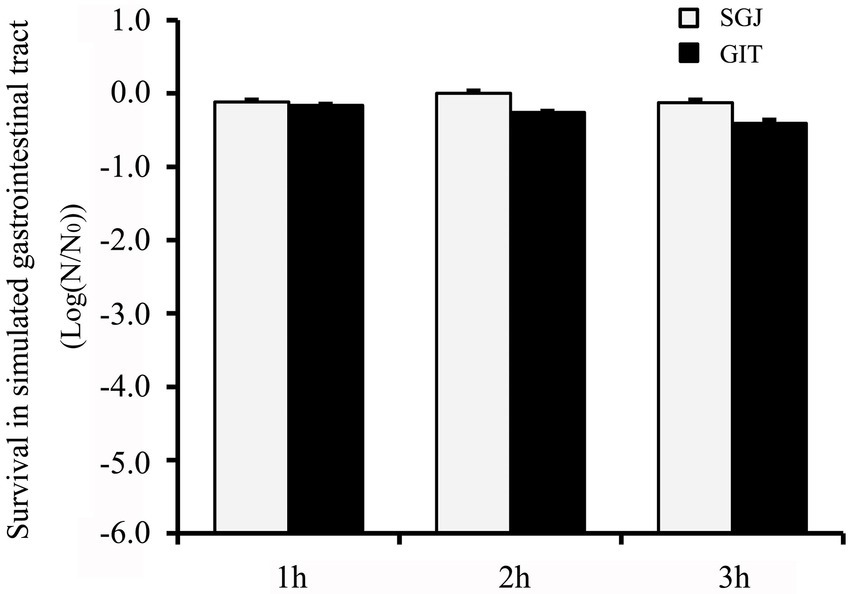

The isolates were further subjected to survival in simulated gastrointestinal tract (GIT) conditions, and the survivors (log N/N0) to SGJ and simulated GIT juices are shown in Figure 4. GXL94 showed good survival percentage in both conditions for 3 h, with the survival rate above 99% in 3 h in SGJ and above 95% in 3 h in GIT juices. Comparatively, GXL94 exhibited the strongest resistance to gastric treatment, but the lowest survival to pancreatic juice. Thus, the intact cells of GXL94 could live through simulated GIT in colonizing the GIT of the host.

Figure 4. Tolerance of simulated gastrointestinal tract (GIT) transit of the cells of Lactobacillus plantarum GXL94. Survival was expressed as reduction of log (N/N0) cycles, where N0 and N are the number of viable cells, respectively, before and after exposure to stress; standard error bars are shown.

Bacterial adhesion to hydrocarbon was evaluated, and as shown in Table 4, the percentage hydrophobicity for GXL94 cells showed 33.01 ± 3.65% for xylene. The co-aggregation ability of GXL94 with the pathogen E. coli O157:H7 was only 30.87% ± 0.21% after incubation at 37°C for 5 h. In addition, GXL94 showed an auto-aggregation percentage of 10.63%, 29.48%, and 50.45% after 1, 3, and 5 h of incubation, respectively.

Tolerance of the strain GXL94 to 10 kinds of antibiotics was shown in Table 5. As is known to all, the susceptibility and resistance of LAB to various antibiotics are variable depending on the species (Li et al., 2020). L. plantarum GXL94 showed sensitivity toward antibiotics belonging to the class of β lactam, macrolactams, nitrobenzenes (Table 5). Meanwhile, GXL94 was resistant to quinolones, aminocyclitol glycosides, polyketide, glycopeptides, aminoglycosides class of tested antibiotics (Table 5). Besides this, GXL94 also was found intermediary sensitive to macrolides. Our results indicated that this LAB strain exhibited a good antibiotic susceptibility.

In addition, GXL94 showed no zone of hemolysis when streaked onto sheep blood agar plates, which was indicative of γ-hemolytic activity (non-hemolytic). And these result further confirmed the biosafety of this strain.

H2O2 is a weak oxidant, but can permeate the cell membrane and form more active ROS, such as hydroxyl radicals, via the Fenton reaction, auto-oxidation and other reactions thereby causing oxidative damage subsequently (Mishra et al., 2015). It is worth mentioning that lactic acid bacteria are regarded as catalase-negative microorganisms used to produce fermented foods (Mokoena et al., 2021). In recent years, a plenty of LAB strains resistant to hydrogen peroxide have been reported. For instance, L. plantarum KCC-24 showed moderate resistance to H2O2 as which can grow normally under the condition of 1.5 mM hydrogen peroxide (Vijayakumara et al., 2015). L. plantarum Y44 had a higher survival rate (>55%) when exposed to 1.0 mM hydrogen peroxide (Mu et al., 2018). Moreover, the latest research confirms that L. plantarum AR113 could tolerance against 8.0 mM H2O2, and it turned into exponential phase at 48 h under 3.5 mM H2O2 (Lin et al., 2020). In this study, we confirmed that L. plantarum GXL94 has a stronger hydrogen peroxide resistance than these antioxidant strains mentioned above, as it can tolerate up to 22 mM hydrogen peroxide concentration.

Most antioxidant evaluation methods based on reactive species can be applied to probiotics, including intact cells, cell-free extracts and cell lysates or their metabolic products to evaluate their antioxidant capacity in vitro (Lin and Chang, 2000; Zolotukhin et al., 2018; Noureen et al., 2019). In this study, we evaluated the antioxidant effects of this three GXL94 samples in vitro respectively, and found both fermented supernatant and intact cells have a good antioxidant potential capacity. Previous research results show that antioxidant activity of LAB strains could be attributed to their production of cell-surface active compounds including proteins, lipoteichoic acid or extracellular polysaccharides (Li et al., 2012; Polak-Berecka et al., 2013), carotenoids (Kim et al., 2019), ferulic acid (Bhathena et al., 2008), or histamine (Azuma et al., 2001). Therefore, whether GXL94 can produce antioxidant molecules to improve its antioxidant performance remains to be further verified.

Antioxidant enzymes including SOD and catalase, thioredoxin, NADH oxidase-NADH peroxidase system, and glutathione system are regarded as three main enzymatic defense mechanisms against oxidative stress in LAB (Serrano et al., 2007; Feng and Wang, 2020). Catalase plays an important role in reducing oxidative stress by decomposing H2O2. LAB have been classified for a long time as unable to produce catalase because of the lack of heme (Ricciardi et al., 2018). However, several researches in recent years have demonstrated that at least some LAB strains are able to synthesis a heme-containing catalase, such L. plantarum CNRZ 1228, L. sakei YSI8, L. brevis CGMCC1306 (Abriouel et al., 2004; An et al., 2010; Lyu et al., 2016). The presence of this gene can significantly improve LAB antioxidant activity. We also cloned heme-containing catalase gene (cat) in strain GXL94, and the transcription of this gene was elevated by 25.3-fold and 6.8, when treated with 2 mM and 3 mM H2O2 at primary stationary phase, respectively. Coupled NADH oxidase—NADH peroxidase system was a common oxidative stress resistance mechanism found in LAB. In these coupled reactions, intracellular oxygen is first used to oxidize NADH into NAD+ by NADH oxidase, thereby releasing H2O2. Subsequently, H2O2 is reduced to H2O by NADH peroxidase (Miyoshi et al., 2003). In this study, we found that two key genes (npx and nox) of these system were present in GXL94, and the npx gene was significantly up-regulated 3.8–6.1-fold at primary stationary phase stage in the presence of hydrogen peroxide. To some extent, the antioxidant capacity of bacteria is related to the biosynthesis or accumulation of glutathione. Bacteria with fully operational glutathione system can directly detoxify or eliminate H2O2 and lipid peroxyl radicals, and thus have defense against H2O2 accumulation (Kullisaar et al., 2010). Previously, it was thought that gram-positive bacteria cannot synthesize GSH and thus do not have the GSH-glutaredoxin system. However, later studies revealed that some LAB, such as and Lactobacillus fermentum E3 and E18, naturally synthesize GSH at a high level (Kullisaar et al., 2002). Whereafter, a fully functional GSH system comprising both GSH peroxidase and GSH reductase in L. fermentum strain ME-3 was first time discovered by Kullisaar and colleagues (Kullisaar et al., 2010). We also identified a functional GSH system in GXL94 in present study. It was noteworthy that the transcription of the four gshR genes were elevated by 3.22-112-fold when GXL94 was challenged with high concentration of H2O2 (3.0 mM). Moreover, GPX function as a H2O2 receptor and redox transducer, which can directly detoxify or eliminate hydrogen peroxide and peroxyl radicals (Kullisaar et al., 2010). Our results also confirmed that the gene was significantly up-regulated under hydrogen peroxide stress. Therefore, we speculate that the GSH system played a major role to ensure the survival of GXL94 under hydrogen peroxide pressure. In recent years, some researchers have used omics studies to reveal the molecular mechanism of the antioxidant performance of L. plantarum. The results showed that various metabolic pathways such as base excision repair system, recombinational DNA repair pathway, pyruvate metabolism, carbon metabolism, trichloroacetic acid cycle, amino acid metabolism, and microbial metabolism were closely related to these antioxidant properties (Zhai et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2022). In future studies, we can use these methods to further explore the molecular mechanism of GXL94 antioxidant properties.

Lactic acid bacteria mainly play a probiotic role in the intestinal tract. After oral ingestion, it needs to experience adverse survival factors in the gastrointestinal tract, such as low pH of gastric acid, bile salts, digestive enzymes, etc. Tolerance to gastrointestinal tract is an important indicator for screening and evaluating effective probiotics. Lactobacillus paracasei FM-LP-4 could survive pH 2.5 for 3 h, but the log CFU/ml was greatly reduced from initial 9 to 7 after 3 h and also showed tolerance to 0.5% bile (Wang et al., 2016). Adesulu-Dahunsi et al. (2018) reported the survival rate of L. plantarum strain OF101 was 98.4% and 96.9% at pH 2.5% and 0.3% bile, respectively. The results of probiotic characteristic tests showed that MA2 could survive at pH 2.5% and 0.3% bile salt for 3 h and maintained a survival of 70% (Tang et al., 2017). In addition, commercial probiotic L. casei Zhang showed survival of 82.7%/97.4% in simulated gastric juice or intestinal juice (Guo et al., 2009). In another study, the survival percentage of L. plantarum AR113 in simulated fluids were only 86.7% (Lin et al., 2018). In view of these reports, our isolate GXL94 were found to show better performance in terms of survival in GIT.

The adhesion ability of lactic acid bacteria to host intestinal cells is another important indicator to evaluate its probiotic property. Auto-aggregation, co-aggregation and adhesion to solvents are the measures to estimate bacterial ability to colonize the intestinal wall. In present study, the auto-aggregation percentage observed with the strain GXL94 (50.45%, 5 h) was higher as compared with the L. plantarum AR113 (30.1%), 1KMT (45.63%), 4 BC (39.56%; Kaktcham et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2020). The adhesion of GXL94 to xylene was comparatively higher than L. plantarum strains UBLP40 (20.4%) and 1KMT (23.71%) reported for xylene adhesion in 1 h (Kaktcham et al., 2018; Ahire et al., 2021). These results indicate that our strain are capable of adhering to epithelial cells and mucosal surfaces. Moreover, GXL94 also showed 30.87% co-aggregation with E. coli. Co-aggregation of probiotic LAB strains with pathogenic bacteria enables them to form a barrier that may facilitate the colonization of the pathogen in the gastrointestinal tract. Low levels of co-aggregation may play an important role in preventing the formation of biofilms and preventing the persistence of pathogenic species in the GIT (Todorov et al., 2017).

One of the important characteristic of probiotic is the safety for human consumption and the absence of acquired and transferable antibiotic resistance. In this study, we observed that L. plantarum GXL94 showed sensitive to ampicillin, penicillin G, tetracycline, rifampicin, chloramphenicol and erythromycin, which was similar to the recent finding of Lin et al. (2020). Some researchers have tested the drug-resistant phenotypes of selected probiotics and found that most LABs are intrinsic resistant to kanamycin, gentamicin, streptomycin, vancomycin and ciprofloxacin (Li et al., 2020). Our result corroborate well with these results. Actually, some probiotic strains with intrinsic antibiotic resistance can help restore the intestinal microbiota after antibiotic treatment (Gueimonde et al., 2013). Some Lactobacillus strains could acquired tetracycline resistance through horizontal gene transfer (Campedelli et al., 2019). GXL94 showed moderate tetracycline resistance in this study, therefore, we need to evaluate whether there are mobile genetic elements with horizontal transfer potential on both sides of tetracycline resistance related genes in future studies. In addition, the hemolytic activity was also evaluated as a criteria for selecting probiotic strains. Our result indicated that GXL94 showed γ-hemolytic or no hemolytic activity, and that it is consistent with found in previous studies (Bhushan et al., 2021). Overall, based on the antibiotic susceptibility profile and hemolytic activity in vitro, GXL94 could fulfill the primary requirements of a probiotic and make this strain a safe candidate for further validation in future probiotic studies in vivo.

Oxidative stress is the cause of various chronic human diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, cataract, and aging (Mishra et al., 2015). Antioxidants are molecules that interact with free radicals generated in cells and terminate the chain reaction to relieve this oxidative stress before damage is done to the vital molecules. However, in the process, antioxidants are themselves oxidized. Thus, there is a constant need to replenish antioxidant resources as one antioxidant molecule can react with only a single free radical (Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1990). Consequently, it is essential to search for and develop natural nontoxic antioxidants to protect the human body from free radicals and slow the progress of many chronic diseases. LABs have been considered as an emerging source of effective antioxidants in recent years due to their long tradition of safe use and potential intestinal benefits (Nardone et al., 2010). It is a general consensus that LAB supplementation can regulate intestinal microbiota, and this microbiota composition reconstruction has the potential to improve the host redox state (Qiao et al., 2012; Xin et al., 2014). Therefore, it is important to consume dietary supplements or fermented foods that contain high antioxidant activity lactic acid bacteria to delay the development of chronic diseases. In view of its good antioxidant properties and beneficial properties, we believe that GXL94 has a good prospect in the application of functional foods with antioxidant properties.

In this study, a LAB strain demonstrated good in vitro antioxidative effect was screened out through a series of experimental evaluation. L. plantarum GXL94 showed good tolerance to high concentration of hydrogen peroxide pressure and strong scavenging capacities to various free radical. After analyzing the eight antioxidant related genes, GPX and gshR were found to up-regulated greatly after H2O2 treated, which may provide the evidence for revealing the molecular mechanism of antioxidant activity of GXL94. Besides this, GXL94 also exhibited promising survivability to acid-, bile salt-, osmotic-, gastric juice-, intestinal juice-tolerance tests, and high auto-aggregation. The non-hemolytic activity and antibiotic susceptibility profile of the strain indicated the safety of probiotic for use. Overall, based on the above analysis for antioxidative and probiotic properties, the strain L. plantarum GXL94 could be considered as potential antioxidant probiotic for commercial use.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

YZ, WG, CXi, and YP were responsible for the study design, supervision, and manuscript preparation. CXu and ZZ were responsible for the experiment and analysis. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was supported by Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program of China (CAAS-ASTIP-2022-IBFC), China Agriculture Research System for Bast and Leaf Fiber Crops (no. CARS-16), and Training Program for Excellent Young Innovators of Changsha (kq2106095).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abriouel, H., Herrmann, A., Stärke, J., Yousif, N. M. K., Wijaya, A., Tauscher, B., et al. (2004). Cloning and heterologous expression of Hematin-dependent catalase produced by lactobacillus plantarum CNRZ 1228. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 603–606. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.603-606.2004

Achuthan, A. A., Duary, R. K., Madathil, A., Panwar, H., Kumar, H., Batish, V. K., et al. (2012). Antioxidative potential of lactobacilli isolated from the gut of Indian people. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39, 7887–7897. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1633-9

Adesulu-Dahunsi, A. T., Jeyaram, K., Sanni, A. I., and Banwo, K. (2018). Production of exopolysaccharide by strains of lactobacillus plantarum YO175 and OF101 isolated from traditional fermented cereal beverage. PeerJ 6:e5326. doi: 10.7717/peerj.5326

Ahire, J. J., Jakkamsetty, C., Kashikar, M. S., Lakshmi, S. G., and Madempudi, R. S. (2021). In vitro evaluation of probiotic properties of lactobacillus plantarum UBLP40 isolated from traditional indigenous fermented food. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 13, 1413–1424. doi: 10.1007/s12602-017-9312-8

Amaretti, A., Nunzio, M., Pompei, A., Raimondi, S., Rossi, M., and Bordoni, A. (2013). Antioxidant properties of potentially probiotic bacteria: in vitro and in vivo activities. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97, 809–817. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4241-7

An, H., Zhou, H., Huang, Y., Wang, G. H., Luan, C. G., Mou, J., et al. (2010). High-level expression of Heme-dependent catalase gene kata from lactobacillus Sakei protects lactobacillus Rhamnosus from oxidative stress. Mol. Biotechnol. 45, 155–160. doi: 10.1007/s12033-010-9254-9

Azuma, Y., Shinohara, M., Wang, P.-L., Hidaka, A., and Ohura, K. (2001). Histamine inhibits chemotaxis, phagocytosis, superoxide anion production, and the production of TNFα and IL-12 by macrophages via H2-receptors. Int. Immunopharmacol. 1, 1867–1875. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00112-6

Balcazar, J. L., de Blas, I., Ruiz-Zarzuela, I., Vendrell, D., Girones, O., and Muzquiz, J. L. (2007). Enhancement of the immune response and protection induced by probiotic lactic acid bacteria against furunculosis in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 51, 185–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00294.x

Bchmeier, N., Bossie, S., Chen, C. Y., Fang, F. C., Guiney, D. G., and Libby, S. J. (1997). SlyA, a transcriptional regulator of salmonella typhimurium, is required for resistance to oxidative stress and is expressed in the intracellular environment of macrophages. Infect. Immun. 65, 3725–3730. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3725-3730.1997

Bhathena, J., Kulamarva, A., Martoni, C., Urbanska, A. M., and Prakash, S. (2008). Preparation and in vitro analysis of microencapsulated live lactobacillus fermentum 11976 for augmentation of feruloyl esterase in the gastrointestinal tract. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 50, 1–9. doi: 10.1042/BA20070007

Bhushan, B., Sakhare, S. M., Narayan, K. S., Kumari, M., Mishra, V., and DicksL, M. T. (2021). Characterization of riboflavin-producing strains of lactobacillus plantarum as potential probiotic candidate through in vitro assessment and principal component analysis. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 13, 453–467. doi: 10.1007/s12602-020-09696-x

Bron, P. A., and Kleerebezem, M. (2011). Engineering lactic acid bacteria for increased industrial functionality. Bioeng. Bugs 2, 80–87. doi: 10.4161/bbug.2.2.13910

Campedelli, I., Mathur, H., Salvetti, E., Clarke, S., Rea, M. C., Torriani, S., et al. (2019). Genus-wide assessment of antibiotic resistance in lactobacillus spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 85, e01738–e01718. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01738-18

Das, P., Khowala, S., and Biswas, S. (2016). In vitro probiotic characterization of lactobacillus casei isolated from marine samples. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 73, 383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.06.029

de Simone, C. (2019). The unregulated probiotic market. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 809–817. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.01.018

Ebel, B., Lemetais, G., Beney, L., Cachon, R., Sokol, H., Langella, P., et al. (2014). Impact of probiotics on risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 54, 175–189. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.579361

Feng, T., and Wang, J. (2020). Oxidative stress tolerance and antioxidant capacity of lactic acid bacteria as probiotic: a systematic review. Gut Microbes 12:1801944. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2020.18019442020

Fuentes, M. C., Lajo, T., Carrión, G. M., and Cuñé, J. (2016). A randomized clinical trial evaluating a proprietary mixture of lactobacillus plantarum strains for lowering cholesterol. Med. J. Nutrition Metab. 9, 125–135. doi: 10.3233/MNM-160065

Galdeano, C. M., and Perdigón, G. (2006). The probiotic bacterium lactobacillus casei induces activation of the gut mucosal immune system through innate immunity. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 13, 219–226. doi: 10.1128/CVI.13.2.219-226.2006

Gao, D., Gao, Z., and Zhu, G. (2013). Antioxidant effects of lactobacillus plantarum via activation of transcription factor Nrf2. Food Funct. 4, 982–989. doi: 10.1039/c3fo30316k

Greppi, A., Hemery, H., Berrazaga, I., Almaksour, Z., and Humblot, C. (2017). Ability of lactobacilli isolated from traditional cereal-based fermented food to produce folate in culture media under different growth conditions. LWT-food. Sci. Technol. 86, 277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2017.08.007

Gueimonde, M., Sanchez, B., De Los Reyes-Gavilán, C. G., and Margolles, A. (2013). Antibiotic resistance in probiotic bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 4:202. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00202

Guo, Z., Wang, J. C., Yan, L. Y., Chen, W., Liu, X. M., and Zhang, H. P. (2009). In vitro comparison of probiotic properties of lactobacillus casei Zhang, a potential new probiotic, with selected probiotic strains. LWT-food. Sci. Technol. 42, 1640–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2009.05.025

Hajare, S. T., and Bekele, G. (2017). Effect of probiotic strain lactobacillus acidophilus (LBKV-3) on fecal residual lactase activity in undernourished children below 10 years. J. Immunoassay Immunochem. 38, 620–628. doi: 10.1080/15321819.2017.1372475

Håkansson, A., Aronsson, C. A., Brundin, C., Oscarsson, E., Molin, G., and Agardh, D. (2019). Effects of lactobacillus plantarum and lactobacillus paracasei on the peripheral immune response in children with celiac disease autoimmunity: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutrients 11:1925. doi: 10.3390/nu11081925

Halliwell, B., and Gutteridge, J. M. (1990). The antioxidants of human extracellular fluids. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 280, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90510-6

He, Q. W., Hou, Q. C., Wang, Y. J., Shen, L. L., Sun, Z. H., Zhang, H. P., et al. (2020). Long-term administration of lactobacillus casei Zhang stabilized gut microbiota of adults and reduced gut microbiota age index of older adults. J. Funct. Foods 64:103682. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.103682

Hill, C., Guarner, F., Reid, G., Gibson, G. R., Merenstein, D. J., Pot, B., et al. (2014). Expert consensus document: the international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 506–514. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66

Ishii, Y., Sugimoto, S., Izawa, N., Sone, T., Chiba, K., and Miyazaki, K. (2014). Oral administration of Bifidobacterium breve attenuates UV-induced barrier perturbation and oxidative stress in hairless mice skin. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 306, 467–473. doi: 10.1007/s00403-014-1441-2

Kaizu, H., Sasaki, M., Nakajama, H., and Suzuki, Y. (1993). Effect of antioxidative lactic acid bacteria on rats fed a diet deficient in vitamin. J. Dairy Sci. 76, 2493–2499. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(93)77584-0

Kaktcham, P. M., Temgoua, J.-B., Zambou, F. N., Diaz-Ruiz, G., Wacher, C., and Pérez-Chabela, M. L. (2018). In vitro evaluation of the probiotic and safety properties of bacteriocinogenic and non-bacteriocinogenic lactic acid bacteria from the intestines of nile tilapia and common carp for their use as probiotics in aquaculture. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 10, 98–109. doi: 10.1007/s12602-017-9312-8

Kiani, A., Nami, Y., Hedayati, S., Komi, D. E. A., Goudarzi, F., and Haghshenas, B. (2021). Application of Tarkhineh fermented product to produce potato chips with strong probiotic properties, high shelf-life, and desirable sensory characteristics. Front. Microbiol. 12:657579. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.657579

Kim, M., Seo, D. H., Park, Y. S., Cha, I. T., and Seo, M. J. (2019). Isolation of lactobacillus plantarum subsp. plantarum producing C30 carotenoid 4, 4′-diaponeurosporene and the assessment of its antioxidant activity. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 29, 1925–1930. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1909.09007

Kok, C. R., and Hutkins, R. (2018). Yogurt and other fermented foods as sources of health-promoting bacteria. Nutr. Rev. 76, 4–15. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuy056

Kullisaar, T., Songisepp, E., Aunapuu, M., Kilk, K., Arend, A., Mikelsaar, M., et al. (2010). Complete glutathione system in probiotic lactobacillus fermentum ME-3. Appl. Biochem. Microb. 46, 481–486. doi: 10.1134/S0003683810050030

Kullisaar, T., Zilmer, M., Mikelsaar, M., Vihalemm, T., Annuk, H., Kairane, C., et al. (2002). Two antioxidative lactobacilli strains as promising probiotics. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 72, 215–224. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(01)00674-2

Lee, J., Hwang, K., Chung, M. Y., Chao, D. H., and Park, C. S. (2005). Resistance of lactobacillus casei KCTC 3260 to reactive oxygen species (ROS): role for a metal ion chelating effect. J. Food Sci. 70, m388–m391. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.tb11524.x

Lee, B.-H., Lo, Y.-H., and Pan, T.-M. (2013). Anti-obesity activity of lactobacillus fermented soy milk products. J. Funct. Foods 5, 905–913. doi: 10.1039/c5fo00531k

Li, Q., Chen, Q., Ruan, H., Zhu, D., and He, G. (2010). Isolation and characterisation of an oxygen, acid and bile resistant Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis Qq08. J. Sci. Food Agric. 90, 1340–1346. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3942

Li, P., Guo, Q., Yang, L. L., Yu, Y., and Wang, Y. J. (2017). Characterization of extracellular vitamin B 12 producing lactobacillus plantarum strains and assessment of the probiotic potentials. Food Chem. 234, 494–501. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.05.037

Li, S. Q., Qi, C., Zhu, H. L., Yu, R. Q., Xie, C. L., Peng, Y. D., et al. (2019). Lactobacillus reuteri improves gut barrier function and affects diurnal variation of the gut microbiota in mice fed a high-fat diet. Food Funct. 10, 4705–4715. doi: 10.1039/C9FO00417C

Li, T., Teng, D., Mao, R. Y., Hao, Y., Wang, X. M., and Wang, J. H. (2020). A critical review of antibiotic resistance in probiotic bacteria. Food Res. Int. 136:109571. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.05.004

Li, S. Y., Zhao, Y. J., Zhang, L., Zhang, X., Huang, L., Li, D., et al. (2012). Antioxidant activity of lactobacillus plantarum strains isolated from traditional Chinese fermented foods. Food Chem. 135, 1914–1919. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.06.048

Lin, M. Y., and Chang, F. J. (2000). Antioxidative effect of intestinal bacteria Bifidobacterium longum ATCC 15708 and lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356. Dig. Dis. Sci. 45, 1617–1622. doi: 10.1023/a:1005577330695

Lin, X., Xia, Y., Wang, G., Xiong, Z., Zhang, H., Lai, F., et al. (2018). Lactobacillus plantarum AR501 alleviates the oxidative stress of D-galactose-induced aging mice liver by upregulation of Nrf2-mediated antioxidant enzyme expression. J. Food Sci. 83, 1990–1998. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.14200

Lin, X. N., Xia, Y. J., Yang, Y. J., Wang, G. Q., Zhou, W., and Ai, L. Z. (2020). Probiotic characteristics of lactobacillus plantarum AR113 and its molecular mechanism of antioxidant. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 126:109278. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109278

Lyu, C. J., Sheng, H. S., Huang, J., Luo, M. Q., Lu, T., Mei, L. H., et al. (2016). Contribution of the activated catalase to oxidative stress resistance and γ-aminobutyric acid production in lactobacillus brevis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 238, 302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.09.023

Mazzantini, D., Calvigioni, M., Celandroni, F., Lupetti, A., and Ghelardi, E. (2021). Spotlight on the compositional quality of probiotic formulations marketed worldwide. Front. Microbiol. 12:693973. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.693973

Mills, S., Stanton, C., Fitzgerald, G. F., and Ross, R. P. (2011). Enhancing the stress responses of probiotics for a lifestyle from gut to product and back again. Microb. Cell Fact. 10:S19. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-10-S1-S19

Mishra, V., Shah, C., Mokashe, N., Chavan, R., Yadav, H., and Prajapati, J. (2015). Probiotics as potential antioxidants: a systematic review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 63, 3615–3626. doi: 10.1021/jf506326t

Miyoshi, A., Rochat, T., Gratadoux, J. J., Le Loir, Y., Oliveira, S. C., Langella, P., et al. (2003). Oxidative stress in Lactococcus lactis. Genet. Mol. Res. 2, 348–359.

Mokoena, M. P., Omatola, C. A., and Olaniran, A. O. (2021). Applications of lactic acid bacteria and their bacteriocins against food spoilage microorganisms and foodborne pathogens. Molecules 26:7055. doi: 10.3390/molecules26227055

Mu, G. Q., Gao, Y., Tuo, Y. F., Li, H. Y., Zhang, Y. Q., Qian, F., et al. (2018). Assessing and comparing antioxidant activities of lactobacilli strains by using different chemical and cellular antioxidant methods. J. Dairy Sci. 101, 10792–10806. doi: 10.3168/jds.2018-14989

Mu, G., Li, H., Tuo, Y., Gao, Y., and Zhang, Y. (2019). Antioxidative effect of lactobacillus plantarum Y44 on 2,2′-azobis (2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride (ABAP)—damaged Caco-2 cells. J. Dairy Sci. 102, 6863–6875. doi: 10.3168/jds.2019-16447

Nardone, G., Compare, D., Liguori, E., Di Mauro, V., Rocco, A., Barone, M., et al. (2010). Protective effects of lactobacillus paracasei F19 in a rat model of oxidative and metabolic hepatic injury. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 299, G669–G676. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00188.2010

Noureen, S., Riaz, A., Arshad, M., and Arshad, N. (2019). In vitro selection and in vivo confirmation of the antioxidant ability of lactobacillus brevis MG000874. J. Appl. Microbiol. 126, 1221–1232. doi: 10.1111/jam.14189

Ou, C. C., Lu, T. M., Tsai, J. J., Yen, J. H., Chen, H. W., and Lin, M. Y. (2009). Antioxidative effect of lactic acid bacteria: intact cells vs. intracellular extracts. J. Food Drug Anal. 17, 209–216.

Persichetti, E., De Michele, A., Codini, M., and Traina, G. (2014). Antioxidative capacity of lactobacillus fermentum LF31 evaluated in vitro by oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay. Nutrition 30, 936–938. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.12.009

Polak-Berecka, M., Wasko, A., Szwajgier, D., and Chomaz, A. (2013). Bifidogenic and antioxidant activity of exopolysaccharides produced by lactobacillus rhamnosus E/N cultivated on different carbon sources. Pol. J. Microbiol. 62, 181–188. doi: 10.33073/pjm-2013-023

Qiao, Y., Sun, J., Ding, Y., Le, G., and Shi, Y. (2012). Alterations of the gut microbiota in high-fat diet mice is strongly linked to oxidative stress. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97, 1689–1697. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4323-6

Ricciardi, A., Ianniello, R. G., Parente, E., and Zotta, T. (2018). Factors affecting gene expression and activity of heme-and manganese-dependent catalases in lactobacillus casei strains. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 280, 66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.05.004

Schnupf, P., Gaboriau-Routhiau, V., and Cerf-Bensussan, N. (2018). Modulation of the gut microbiota to improve innate resistance. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 54, 137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2018.08.003

Serrano, L. M., Molenaar, D., Wels, M., Teusink, B., Bron, P. A., de Vos, W. M., et al. (2007). Thioredoxin reductase is a key factor in the oxidative stress response of lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1. Microb. Cell Fact. 6:29. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-6-29

Tang, W., Xing, Z. Q., Hu, W., Li, C., Wang, J. J., and Wang, Y. P. (2016). Antioxidative effects in vivo and colonization of lactobacillus plantarum MA2 in the murine intestinal tract. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100, 7193–7202. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7581-x

Tang, W., Xing, Z. Q., Li, C., Wang, J. J., and Wang, Y. P. (2017). Molecular mechanisms and in vitro antioxidant effects of lactobacillus plantarum MA2. Food Chem. 221, 1642–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.10.124

Tian, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, N., Xiao, M. M., Zhang, J., Xing, X. Y., et al. (2022). Antioxidant mechanism of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum KM1 under H2O2 stress by proteomics analysis. Front. Microbiol. 13:897387. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.897387

Todorov, S. D., Holzapfel, W., and Nero, L. A. (2017). In vitro evaluation of beneficial properties of Bacteriocinogenic lactobacillus plantarum ST8Sh. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 9, 194–203. doi: 10.1007/s12602-016-9245-7

Vijayakumara, M., Ilavenila, S., Kim, D. H., Arasu, M. V., Priya, K., and Choi, K. C. (2015). In-vitro assessment of the probiotic potential of lactobacillus plantarum KCC-24 isolated from Italian rye-grass (Lolium multiflorum) forage. Anaerobe 32, 90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.01.003

Wang, J., Zhang, W., Wang, S. X., Wang, Y. M., Chu, X., and Ji, H. F. (2021). Lactobacillus plantarum exhibits antioxidant and cytoprotective activities in porcine intestinal epithelial cells exposed to hydrogen peroxide. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021:8936907. doi: 10.1155/2021/8936907

Wang, Y., Zhou, J. Z., Xia, X. D., Zhao, Y. C., and Shao, W. L. (2016). Probiotic potential of lactobacillus paracasei FM-LP-4 isolated from Xinjiang camel milk yoghurt. Int. Dairy J. 62, 28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2016.07.001

Xin, J., Zeng, D., Wang, H., Ni, X., Yi, D., Pan, K., et al. (2014). Preventing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease through lactobacillus johnsonii BS15 by attenuating inflammation and mitochondrial injury and improving gut environment in obese mice. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 6817–6829. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5752-1

Zhai, Z. Y., Yang, Y., Wang, H., Wang, G. H., Ren, F. Z., Li, Z. G., et al. (2020). Global transcriptomic analysis of lactobacillus plantarum CAUH2 in response to hydrogen peroxide stress. Food Microbiol. 87:103389. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2019.103389

Keywords: lactic acid bacteria, Lactobacillus plantarum, antioxidant activity, probiotic, hydrogen peroxide

Citation: Zhou Y, Gong W, Xu C, Zhu Z, Peng Y and Xie C (2022) Probiotic assessment and antioxidant characterization of Lactobacillus plantarum GXL94 isolated from fermented chili. Front. Microbiol. 13:997940. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.997940

Received: 19 July 2022; Accepted: 25 October 2022;

Published: 17 November 2022.

Edited by:

Evandro L. de Souza, Federal University of Paraíba, BrazilReviewed by:

Patrícia Tette, Universidade Federal de Goiás, BrazilCopyright © 2022 Zhou, Gong, Xu, Zhu, Peng and Xie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunliang Xie, eGllY2h1bmxpYW5nQGNhYXMuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.