Abstract

Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) enzyme is ubiquitously present in all life forms and plays a variety of roles in diverse organisms. Higher eukaryotes mainly utilize GGT for glutathione degradation, and mammalian GGTs have implications in many physiological disorders also. GGTs from unicellular prokaryotes serve different physiological functions in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. In the present review, the physiological significance of bacterial GGTs has been discussed categorizing GGTs from Gram-negative bacteria like Escherichia coli as glutathione degraders and from pathogenic species like Helicobacter pylori as virulence factors. Gram-positive bacilli, however, are considered separately as poly-γ-glutamic acid (PGA) degraders. The structure–function relationship of the GGT is also discussed mainly focusing on the crystallization of bacterial GGTs along with functional characterization of conserved regions by site-directed mutagenesis that unravels molecular aspects of autoprocessing and catalysis. Only a few crystal structures have been deciphered so far. Further, different reports on heterologous expression of bacterial GGTs in E. coli and Bacillus subtilis as hosts have been presented in a table pointing toward the lack of fermentation studies for large-scale production. Physicochemical properties of bacterial GGTs have also been described, followed by a detailed discussion on various applications of bacterial GGTs in different biotechnological sectors. This review emphasizes the potential of bacterial GGTs as an industrial biocatalyst relevant to the current switch toward green chemistry.

Introduction

The enzyme γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT; E.C.2.3.3.2) is conserved throughout all three domains of life, ranging from single-celled prokaryotes to multicellular higher eukaryotes (Rawlings et al., 2010). It belongs to the N-terminal nucleophile hydrolase superfamily and exists as a heterodimer of a large and a small subunit (Nash and Tate, 1984; Suzuki et al., 1989; Brannigan et al., 1995). It is a two-substrate enzyme catalyzing the transfer of γ-glutamyl moiety from donor substrates, such as glutathione/glutamine, to an acceptor substrate, which can be water (hydrolysis) or other amino acids/small peptides (transpeptidation) or the donor itself (autotranspeptidation) (Thompson and Meister, 1977; Tate and Meister, 1981). Here, the GGT is commonly referred to by its old name as “gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase;” however, according to the Nomenclature Committee of International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular biology, its accepted name is γ-glutamyltransferase (Balakrishna and Prabhune, 2014).

Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase enzyme was first reported in mammals, such as sheep and rat (Hanes et al., 1952; Tate and Meister, 1976). It is worldwide recognized as a diagnostic marker for many physiological diseases in humans (Yamada et al., 1991; Whitfield, 2001; Grundy, 2007). Although its existence in the living world was known for a long time, only after its discovery in prokaryotes led to a profound understanding of its structure–function relationship and also suggested its application in the synthesis of various γ-glutamyl compounds. Presently, it finds biotechnological significance in the synthesis of various bioactive γ-glutamyl compounds for application in food and pharmaceutical sectors (Suzuki et al., 2004a; Wang et al., 2008; Shuai et al., 2010; Saini et al., 2017; Mu et al., 2019).

Mammalians GGTs have already been extensively reviewed (Tate and Meister, 1981; Taniguchi and Ikeda, 1998; Chikhi et al., 1999; Whitfield, 2001). Microbial GGTs, covering the structure–function relationship of the protein and their biotechnological significance, have been reviewed by Castellano and Merlino (2012) and subsequently by Balakrishna and Prabhune (2014).

The current review focuses mainly on bacterial GGTs with emphasis on their physiological significance, structural and molecular aspects, autoprocessing, and enzyme catalysis along with their relevance in biotechnology and biomedicine sectors.

Diversity of Bacterial GGTs

Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidases diversity ranging from microbes to mammals has been described by Verma et al. (2015) through a phylogenetic tree, including 47 diverse GGT sequences. This phylogenetic tree had two main branches and various clades (Verma et al., 2015). The tree also showed some interesting evolutionary relationships of prokaryotic and eukaryotic GGTs, as it grouped pathogenic bacterial GGTs including Escherichia coli GGT with eukaryotic ones, instead of their nonpathogenic bacterial homologues. This suggests high sequence similarity between pathogens and their hosts. Glutathione hydrolysis by E. coli and most of the pathogenic GGTs represents a functional similarity to mammalian GGTs. However, in Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis, the presence of two types of GGT enzymes – the canonical GGT placed in close association to other Bacillus GGTs and GGT-like protein YwrD grouped with archaeal and extremophilic GGTs – suggest the horizontal transfer of YwrD protein to the mesophilic Bacillus strains from some other archaea or extremophiles. Thus, the diversification of GGT proteins gives intriguing insights into the evolutionary history of this ubiquitously conserved protein. Besides, GGT proteins were also classified into two distinct groups based on the presence or absence of a 12-residue long structural sequence known as lid loop. Accordingly, GGTs from eukaryotes and Gram-negative organisms have been termed as lid-loop positive and GGTs from Bacillus species, archaea, and extremophiles as lid-loop negative.

Physiological Significance of Bacterial GGT

Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase protein shows widespread conservation, but its physiological role is not very clear yet (Balakrishna and Prabhune, 2014). Mammalian GGTs are involved in glutathione metabolism; on the other hand, prokaryotic GGTs are known to have diverse physiological functions stemming from the fact that the glutathione is not found among all prokaryotes (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| GGT group and associated organisms | Expression and localization | Putative Physiological role |

| 1. Glutathione degrading GGT – mainly present in glutathione producing Gram-negative bacteria | ||

| E. coli | Periplasmic expression | Glutathione utilization as a source of amino acid and nitrogen under nutrient limiting conditions |

| Proteus mirabilis | Localized on the outer cytoplasmic membrane facing the periplasm | |

| 2. GGT as virulence factor – mainly present in pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria | ||

| Helicobacter pylori | Periplasmic expression | Utilization of host’s glutathione and glutamine as a source of glutamate; Inhibition of T-cell proliferation in host |

| Campylobacter jejuni | ND# | |

| Fransicella tularensis | ND | Utilization of cytosolic glutathione and γ-glutamyl cysteine peptides present in host cytosol for cysteine acquisition |

| Neisseria meningitidis | Expressed on the inner cytoplasmic membrane facing cytoplasm | Utilization of cytosolic γ-glutamyl cysteine peptides for cysteine acquisition |

| 3. PGA hydrolyzing GGT – mainly present in PGA producing Gram-positive bacteria | ||

| Bacillus subtilis (natto) | Extracellular secretion | Degradation of PGA into glutamate as a source of nitrogen under nutrient-starved conditions |

| Bacillus licheniformis | Extracellular secretion | |

| Bacillus anthracis* | Membrane-bound expression | Covalent anchorage of PDGA to peptidoglycan layer to maintain capsule integrity; Depolymerization of PDGA inside the cytoplasm |

Classification of bacterial gamma-glutamyl transpeptidases (GGTs) into different physiological groups.

#Not determined.*Bacillus anthracis is also a pathogenic strain and GGT is involved in its virulence; however, it has been placed in the third group as it is a Gram-positive Bacillus with PDGA as a virulence factor.

Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase was first reported in some Gram-negative proteobacteria, such as Proteus mirabilis and E. coli, as a periplasmic protein along with glutathione as the most abundant thiol (Fahey et al., 1978; Nakayama et al., 1984; Suzuki et al., 1986; Masip et al., 2006). In these organisms, deletion or inhibition of the GGT enzyme led to increased extracellular leakage of glutathione (Nakayama et al., 1984; Suzuki et al., 1986). Further studies indicated its possible role in the cleavage of glutathione in periplasmic space to provide cysteine and glycine in Gram-negative bacteria, similar to mammalian GGTs. Another report on E. coli GGT indicated its ability to uptake an exogenous supply of γ-glutamyl peptides and glutathione as the source of amino acids (Suzuki et al., 1993). For Pseudomonas species, periplasmic localization of GGT has been reported, but its involvement in glutathione metabolism could not be elucidated (Kushwaha and Srivastava, 2014).

In some Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria such as Helicobacter pylori, Fransicella tularensis, Neisseria meningitidis, and Campylobacter jejuni, the expression of GGT has been linked to their pathophysiology, and GGT has been ascribed as a formidable virulence factor (Ling, 2013). The pathogenicity mechanism in H. pylori, which causes gastritis, gastric ulcers, and cancers in humans, has been studied extensively. H. pylori cells colonize gastric mucosa of mammalian gut involving several virulence factors including GGT for the establishment of infection (Ling, 2013; Ricci et al., 2014). During colonization, constitutive periplasmic expression of H. pylori GGT (HpGGT) allowed metabolism of extracellular glutathione and glutamine present in the host cytosol as a source of glutamate by H. pylori cells (Chevalier et al., 1999; Shibayama et al., 2007). This has been suggested to be the key physiological role played by HpGGT resulting in profuse growth of the pathogen in the gastric mucosa (Gong and Ho, 2004). HpGGT has also been reported to induce apoptosis of gastric epithelial cells under oxidative stress aided by scavenging glutathione from the gastric environment (Shibayama et al., 2003; Gong et al., 2010; Flahou et al., 2011). It has also been demonstrated to have an immunosuppressive effect on the host, as it inhibits the proliferation of T cells resulting in persistent colonization and infection (Schmees et al., 2007). Higher activity of HpGGT from peptic ulcer patients corroborates its clinical relevance as a virulence factor in the diagnosis of gastric-related diseases caused by H. pylori (Gong et al., 2010; Franzini et al., 2014). A similar physiological function of GGT was reported in another pathogen C. jejuni, closely related to H. pylori. GGT from C. jejuni assisted in the inhibition of T-cell proliferation, thus promoting persistent colonization of gastric epithelial cells in mammals and avian gut (Barnes et al., 2007; Floch et al., 2014).

Fransicella tularensis, a facultative intracellular pathogen, causes tularemia by mainly infecting phagocytic macrophages (Clemens et al., 2004). The role of GGT in its pathogenesis was demonstrated by mutational disruption of ggt gene that resulted in drastic defects in its intracellular growth and its replication in macrophage cell lines and caused an attenuated virulence in mice. Here, GGT was reported to be responsible for utilization of glutathione and γ-glutamyl cysteine pools of host as a source of cysteine, essential in intracellular multiplication of pathogen (Alkhuder et al., 2009). In fact, ggt deletion mutant of a highly virulent F. tularensis SCHU S4 strain has been reported as a potential vaccine candidate; patent was granted in 2013 (United States 8,609,108B2) (Ireland et al., 2011; Le Butt et al., 2013). Another Gram-negative bacteria N. meningitidis, the causative agent of a deadly brain disease, meningitis, has also been reported to utilize GGT for cysteine acquisition from an extracellular pool of γ-glutamyl cysteine peptides (Takahashi et al., 2004, 2018). It was located in association with the inner membrane toward the cytoplasmic side, suggesting easy accessibility to extracellular peptides (Takahashi and Watanabe, 2004).

Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase has been reported in other prokaryotes as well, such as in Gram-positive bacilli including B. subtilis, B. licheniformis, Bacillus anthracis (a pathogen), and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, and in extremophiles such as Geobacillus thermodentrificans, Deinococcus radiodurans, and Thermus thermophilus and archaea like Picrophilus torridus. In Gram-positive bacilli, many studies on the putative physiological role of GGTs have ruled out their involvement in glutathione degradation for amino acid utilization, as these bacteria cannot synthesize glutathione (Fahey et al., 1978), although they can hydrolyze it under in vitro conditions (Minami et al., 2003b). In another report, when glutathione was supplemented externally as a nitrogen source, the cysteine and glycine auxotrophic mutants of B. subtilis could not grow owing to their inability in utilizing glutathione as a source of these amino acids (Xu and Strauch, 1996). However, B. subtilis GGT has shown efficacy in cleaving γ-glutamyl bond of glutathione to release cysteinylglycine as a sulfur source instead (Minami et al., 2004). GGT in Bacillus species is secreted extracellularly during the onset of the stationary phase, suggesting its role in stationary phase physiology (Xu and Strauch, 1996). Many Bacillus species produce poly-γ-glutamic acid (PGA) at the onset of the stationary phase, which is utilized as a nitrogen source during the late stationary phase under nutrient-starved conditions (Ashiuchi and Misono, 2002). The involvement of B. subtilis (natto) GGT in the hydrolysis of PGA was investigated for the first time by Kimura et al. (2004). Here, GGT knockout mutant was shown to produce an increased amount of medium-sized PGA fragments (1 × 105 Da) as compared to the wild-type strain, in which both the amount and the size of PGA fragments (5 × 103 Da) decreased considerably. They suggested that the large PGA fragments must have first got hydrolyzed to medium-sized fragments by an endopeptidase YwtD (now known as PgdS) (Suzuki and Tahara, 2003); B. subtilis GGT may have acted later as an exopeptidase catalyzing the cleavage of glutamate (both L-and D-forms) residue from amino-terminal of the medium-sized PGA fragments (Kimura et al., 2004). In another report, a double knockout of pgdS and ggt gene resulted in twofold enhanced production of PGA in B. subtilis 168 strain; however, single-gene knockout of pgdS or ggt did not improve PGA yields (Scoffone et al., 2013). Moreover, among the three mutants, the pgdS single mutant produced PGA with the highest molecular weight, which could be attributed to hampered endo-peptidase activity. Contrasting results were obtained in a recent report of pgdS and ggt knockout mutants of B. licheniformis RK14-46 strain. The single pgdS gene knockout, as well as the double knockout of pgdS and ggt gene, resulted in a drastic reduction in PGA production, while the single ggt gene knockout improved PGA production due to lesser degradation (Ojima et al., 2019). This suggests that GGT is crucial for PGA hydrolysis by Bacillus species, and these GGT-producing Gram-positive bacilli can be classified as PGA degraders.

In addition to GGT, Bacillus species like B. subtilis and B. licheniformis also code for another GGT-like protein named YwrD, expressed intracellularly and shares only 27% sequence similarity with well-described GGTs (Grundy and Henkin, 2001). However, this protein has not been assigned any role yet (Minami et al., 2004).

Another GGT-producing Gram-positive bacterium known to be a deadly pathogen, B. anthracis, produces capsular poly-γ-D-glutamic acid (PDGA) as a virulence factor to evade off immune response (Wu et al., 2009). It expresses a virulent protein named capsule depolymerase (CapD), which is located on the cellular surface in association with bacterial envelope (Candela and Fouet, 2005). CapD is considered to be a part of the GGT family, as it, respectively, shares 31 and 27% sequence similarity to E. coli and B. subtilis GGTs and exhibits similar autoprocessing steps (Uchida et al., 1993; Minami et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2009). CapD has been mainly reported to catalyze the covalent anchoring of PDGA to peptidoglycan for maintaining the integrity of the capsule (Richter et al., 2009). CapD minus B. anthracis mutant showed no capsule layer after heat and chemical treatment and was reported to have an attenuated virulence in mice models (Candela and Fouet, 2005). Apart from its anchoring function, CapD has also been suggested to carry out depolymerization of PDGA in the cell cytoplasm (Richter et al., 2009).

Recently, the role of B. subtilis GGT (BsGGT) as a novel virulence factor in the pathogenesis of bone resorption similar to mammalian GGT (Niida et al., 2004) has been demonstrated in a cell culture study (Kim et al., 2016). It was reported that the large subunit of BsGGT enhanced osteoclastogenesis activity, independent of enzymatic activity. Further molecular study in the presence of BsGGT large subunit showed that the induction of osteoclastogenesis was related to upregulation of an osteoclast differentiation factor receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL), which interacted with surface receptors of precursor osteoblast cells and promoted the formation of osteoclast cells. In addition, there was an enhancement in the messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2). Based on these findings, GGT has been hypothesized to act as a virulence factor in bone destruction, caused by periodontopathic bacteria (Kim et al., 2016).

The physiological significance of GGT in extremophilic microbes has not been elucidated yet. The reason could be the extreme cultural conditions required during cultivation and also the difficulty in the genetic manipulation of such strains.

Structural and Functional Aspects of Bacterial GGTs

Structural and Topological Features

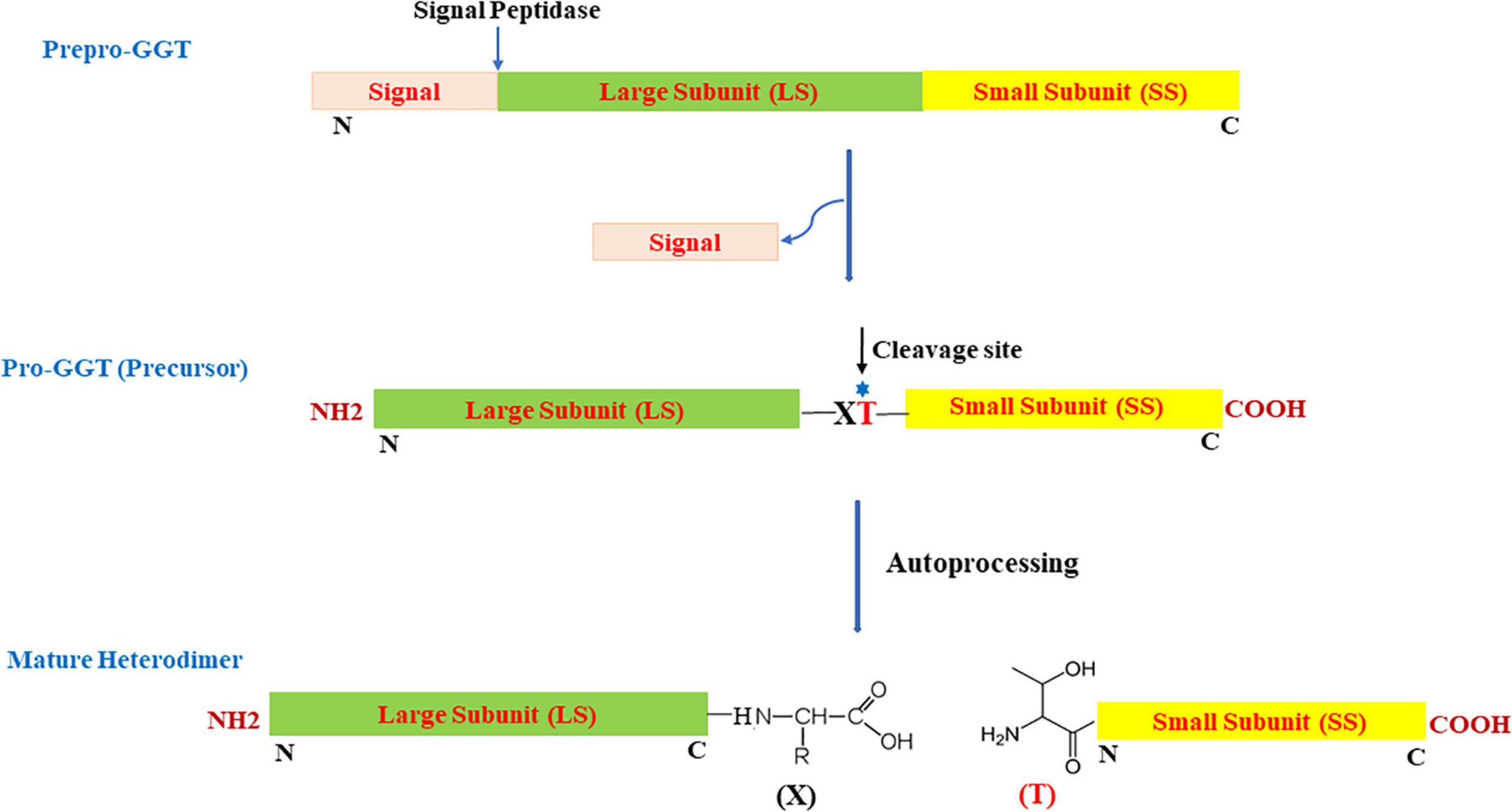

Most microbial GGTs are synthesized as prepro-GGT with N-terminal signal peptide (Figure 1) sequence for extracellular secretion. After the signal is cleaved, the resulting unique precursor pro-GGT is modified through a self-proteolytic cleavage event termed autoprocessing, forming an active mature heterodimer of large and small subunits (Tate and Meister, 1981; Lo et al., 2007). Autoprocessing involves a conserved nucleophile threonine positioned subcentric inclined toward C-terminal (Balakrishna and Prabhune, 2014). Post autoprocessing, resulting C- and N-terminal, respectively, form large and small subunits; with conserved threonine as the first residue in smaller subunit to serve as a nucleophile for carrying out enzymatic reaction (Inoue et al., 2000; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Schematic view of organization and two-step maturation of bacterial gamma-glutamyl transpeptidases (GGTs); the cleavage site represents the site of autoprocessing. T, conserved threonine; X, residue preceding the conserved threonine; N, N-terminus; C, C-terminus.

Primary structure analysis of various microbial GGTs has shown that the intact polypeptide is generally composed of 500 ± 100 amino acid residues (Supplementary Figure 1). GGTs from mesophilic organisms like E. coli (EcGGT), H. pylori (HpGGT), Pseudomonas, and Bacillus species contain around 24–35-residue long N-terminal signal peptide, while some extremophilic organisms like Geobacillus thermodenitrificans (GtGGT), Thermus hermophiles (TtGGT), D. radiodurans (DrGGT), etc., lack any signal peptide and are thus intracellular. Primary sequence comparison also reveals >25% sequence similarities among different species, including mammalian GGT from Homo sapiens (HsGGT). Further, putative cleavage site for autoprocessing occupied by threonine [T391 in EcGGT; T380 in HpGGT; T399 in B. licheniformis GGT (BlGGT)] and two glycine residues (G483/G484 in EcGGT; G481/G482 in BlGGT), constituting oxyanion hole for stabilizing tetrahedral enzyme intermediate during catalysis, is invariably conserved. Large subunit is less conserved and consists of 300–405 residues, while 170–195 amino acid long small subunit is relatively conserved and contains active site residues (Tate and Ross, 1977; Castonguay et al., 2003). These subunits are highly intertwined, mainly by noncovalent hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding (Castellano and Merlino, 2012). The first crystal structure to be elucidated was of E. coli GGT (EcGGT) in 2006; in fact, three different structures of EcGGT (PDB IDs: 2DBU, 2D5G, 2DBX) were determined simultaneously (Table 2; Okada et al., 2006). Thereafter, GGT structures from a variety of microbes such as H. pylori (HpGGT), B. subtilis (BsGGT), B. licheniformis (BlGGT), B. anthracis (BanGGT; CapD), Bacillus halodurans (BhGGT), Pseudomonas nitoreducens (PnGGT), and Thermoplasma acidophilum (TaGGT) were determined (Boanca et al., 2007; Okada et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2009; Wada et al., 2010; Ida et al., 2014; Pica et al., 2016; Kumari et al., 2017; Table 2). Although the mammalian GGTs were the first to be described in detail, heavy glycosylation and membrane-bound localization made it difficult to determine their structure; the first crystal structure of human GGT was solved in 2013 (West et al., 2013).

TABLE 2

| Enzyme | PDB ID | Resolution | Structural form | GGT molecules in the asymmetric unit |

| EcGGT | 2DBU | 1.95 | Ligand free form | Heterotetramer – two heterodimeric molecules containing two large and two small subunits |

| 2DG5 | 1.60 | In complex with hydrolyzed glutathione (substrate) | ||

| 2DBX | 1.70 | In complex with glutamate (substrate) | ||

| 2DBW | 1.80 | Acyl-enzyme intermediate | ||

| 2E0Y | 2.02 | Samarium derivative | ||

| 2E0X | 1.95 | Monoclinic form (Se-Met GGT) | ||

| 2Z8K | 1.65 | In complex with acivicin (inhibitor) | ||

| 2Z8J | 1.65 | In complex with azaserine (inhibitor) | ||

| 2Z8I | 2.05 | In complex with azaserine in dark | ||

| 2E0W | 2.55 | T391A mutant | Dimer – two identical precursor molecules | |

| HpGGT | 2NQO | 1.90 | Ligand free form | Heterotetramer – two heterodimeric molecules containing two large and two small subunits |

| 2QMC* | 1.55 | T380A mutant in complex with S-(nitrobenzyl)glutathione | ||

| 2QM6 | 1.60 | In complex with glutamate | ||

| 3FMN | 1.70 | In complex with acivicin | ||

| 5BPK | 1.49 | − | ||

| BsGGT | 2V36 | 1.85 | Ligand free form | Heterotetramer – two heterodimeric molecules containing two large and two small subunits |

| 3A75 | 1.95 | In complex with glutamate | ||

| 3WHS | 1.80 | In complex with acivicin | Heterodimer – one large and small subunit | |

| 3WHQ | 1.58 | Soaked in acivicin for 0 min | ||

| 3WHR | 1.85 | Soaked in acivicin for 3 min | ||

| BlGGT | 4OTT | 2.98 | Ligand free mature form | Heterodimer – one large and small subunit |

| 4OTU# | 3.02 | In complex with glutamate | ||

| 5XLU | 1.45 | In complex with acivicin | ||

| 4Y23 | 2.89 | T399A precursor mutant | Monomer – one molecule of precursor | |

| PnGGT | 5ZJG | 1.70 | In complex with Gly–Gly | Heterotetramer – two heterodimeric molecules containing two large and two small subunits |

| BhGGT (cephalosporin acylase) | 2NLZ | 2.70 | Ligand free form | Heterotetramer – two heterodimeric molecules containing two large and two small subunits |

| BanGGT (CapD) | 3G9K | 1.79 | Ligand free form | Heterotetramer – two heterodimeric molecules containing two large and two small subunits |

| 3GA9 | 2.30 | Ligand free form | ||

| TaGGT | 2I3O | 2.03 | Ligand free form | Heterotetramer – two heterodimeric molecules containing two large and two small subunits |

List of crystal structures available for prokaryotic gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGTs).

*Crystal of an inactive but processed T380A mutant using a bicistronic construct expressing large and small subunit separately.#Presence of Mg2+ ion crucial for crystal formation.

It has also been demonstrated that in various GGTs, the content of secondary structures formed of α-helices and β-sheets is nearly identical, resulting in similar tertiary and quaternary structural folding (Lin et al., 2014). A highly conserved tetralamellar α/ββ/α fold forms core of the enzyme appearing sandwich-like, made of two tightly packed antiparallel β-sheets, one from each subunit, surrounded by two α-helices (Okada et al., 2006). This fold is characteristic of the N-terminal nucleophile (Ntn) hydrolase superfamily (Brannigan et al., 1995). Most members of this family including penicillin G acylase (Hewitt et al., 2000), cephalosporin acylase (Kim et al., 2000), glycosylasparaginase (Guo et al., 1998), etc., are synthesized as inactive precursors, which undergo autocatalytic processing to form an active mature protein. The activated protein acquires either a nucleophile serine, threonine, or cysteine as its first residue at the newly formed N-terminus with suggested role in catalysis and autoprocessing. Similarly, in case of GGT enzyme, the mechanism of autoprocessing and catalysis also involves a conserved threonine; GGT is therefore considered to be a member of the Ntn hydrolase superfamily.

Molecular Mechanism of Autoprocessing

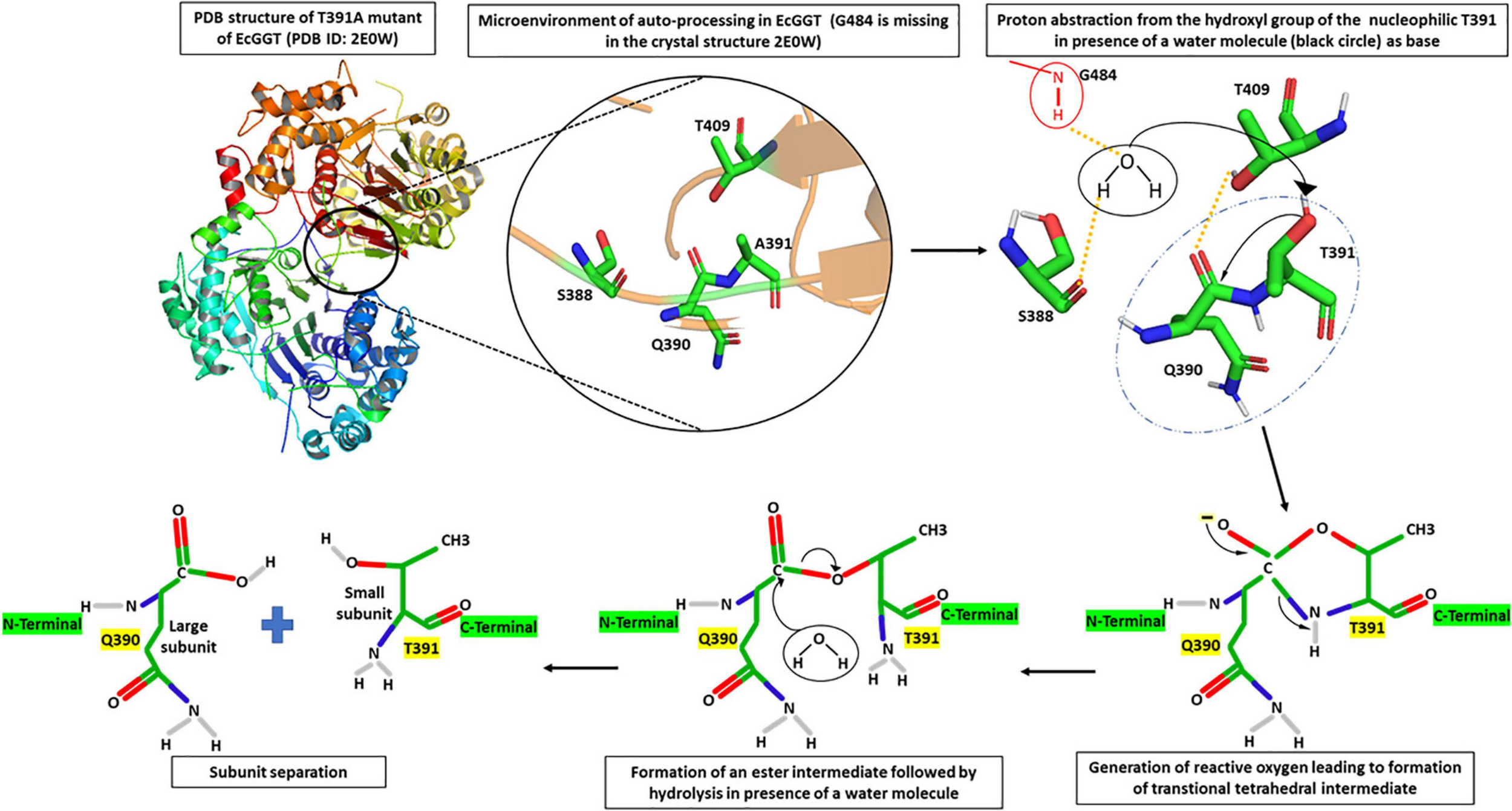

Through several mutational and crystallography studies, it was demonstrated for the first time in EcGGT that the processing was an autocatalytic event rather than a, earlier hypothesized, protease-dependent occurrence (Kuno et al., 1984). Suzuki and Kumagai (2002) proposed a molecular mechanism of autoprocessing of EcGGT based on its similarity to the Ntn hydrolase superfamily. They suggested that the hydroxyl group of Thr391 (in EcGGT) acts as a nucleophile for proteolytic cleavage of scissile peptide bond with the preceding residue Gln390; the presence of a base abstracts proton from the hydroxyl group of Thr391, generating a reactive oxyanion (Figure 2). The reactive oxygen at gamma position (OG) atom attacks the carbonyl carbon of Gln390 to form a transitional tetrahedral intermediate. The C–N bond later gets cleaved via protonation of nucleophile threonine’s amino group, leading to an ester intermediate (N–O acyl shift) which is hydrolyzed further into two subunits with Thr391 as the new N-terminal residue of small subunit (Suzuki and Kumagai, 2002).

FIGURE 2

Microenvironment for autocatalytic processing of Escherichia coli gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (EcGGT) and its detailed molecular mechanism. Crystal structure of T391A precursor mutant of EcGGT (PDB ID: 2E0W) has been used for studying autocatalytic environment. A391 in the structure has been replaced by T391 to show hydrogen bonding (yellow dashed lines) and nucleophilic attack (black arrow) by T391 during autoprocessing. A water molecule (black circle) and amide bond of G484 (red circle) have been drawn to show bonding. The structures are prepared using PyMOL2 software.

Further analysis of the crystal structure of mature E. coli GGT (PDB Id: 2DBU), as well as its mutated T391A precursor (PDB ID: 2E0W), provided more mechanistic details of autoprocessing. A water molecule in the close vicinity of Gln390 hydrogen bonded to the hydroxyl group of Ser388 and α-amino group of Gly484 has been reported to enhance nucleophilicity of OG atom of Thr391 that appears crucial in autoprocessing (Figure 2; Okada et al., 2006, 2007). Accordingly, it was reported that substituting conserved threonine in HpGGT (Thr380) and BlGGT (Thr399) with alanine led to complete inhibition of autoprocessing (Boanca et al., 2006; Lyu et al., 2009). Similarly, the cysteine mutant (T399C) of BlGGT remained unprocessed, indicating the importance of the hydroxyl group in cleaving peptide bond (Lyu et al., 2009). Serine mutants of both BlGGT (T399S) and HpGGT (T380S) showed a dramatic decrease in the processing rate; the mutants were, however, processed completely after prolonged incubation. For HpGGT, the role of the methyl group present in the side chain of nucleophile threonine has been suggested for properly positioning the hydroxyl group during the nucleophilic attack (Boanca et al., 2006).

Similar autoprocessing behavior was observed in GtGGT from an extremophilic organism G. thermodenitrificans where a homotetrameric precursor is initially produced, which underwent autocatalysis after incubation at 45°C for 48 h (Castellano et al., 2010). The alanine mutant (T353A) of its conserved threonine 353 was also expressed as an inactive unprocessed homotetramer (Castellano et al., 2010).

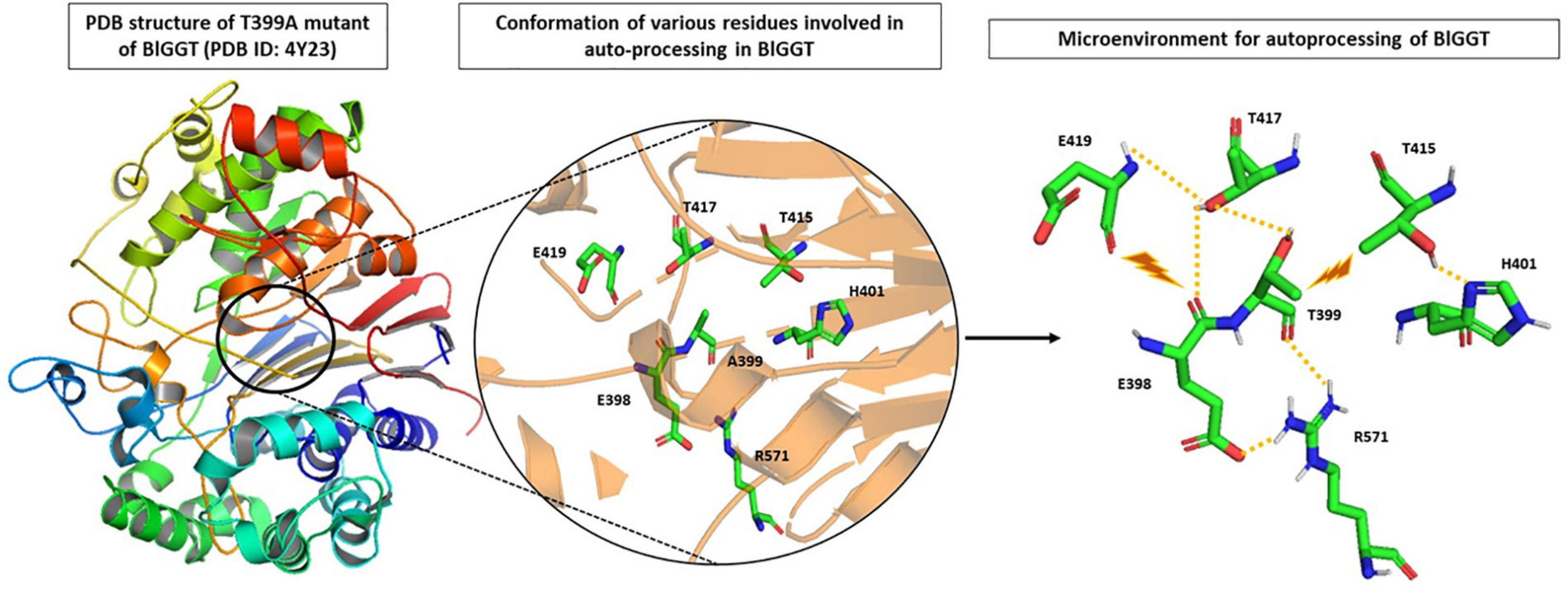

Analysis of the recently solved crystal structure of the T399A precursor mimic of BlGGT gave interesting insights; Pica et al. (2016) explored the microenvironment required for autocatalytic processing and proposed a slightly different mechanism of autoprocessing. They suggested that in BlGGT, Thr399 is activated by the OG atom of another Thr417 in lieu of a water molecule as is the case of EcGGT (Figure 3). This leads to a six-membered transition state involving two hydroxyl groups of Thr399 and Thr417 and one carbonyl group of Gln398. Following this, a transient tetrahedral intermediate is formed, and later, hydrolysis of ester bond yields two subunits. Contribution of some other residues, namely, His401, Thr415, Thr417, E419, and Arg571, reported to be important for proper positioning of Gln398 and Thr399, was also assessed by the same group (Figure 3). They generated alanine mutants of each of the five residues and characterized them concerning autoprocessing. Mutants E419A and R571A could process completely, while H401A and T417A showed 60–70% processing in a time-dependent fashion, and T415A mutant persisted as an inactive precursor. Similar maturational defects were observed in EcGGT when the corresponding residue Thr407 (Thr415 in BlGGT) was mutated to aspartate (T407D), lysine (T407K), and serine (T407S) (Lo et al., 2007). In another report from BlGGT, its T417S mutant could process considerably with time, while T417K mutant led to complete blockage of maturation, suggesting the importance of hydroxyl group of Thr417 for proper autoprocessing (Lyu et al., 2009). In HpGGT, mutation of the same threonine residue at position 398 to serine (T398S) and alanine (T398A) resulted in comparable processing rates with respect to native HpGGT (Boanca et al., 2007). Thus, despite being highly conserved among microbial as well as mammalian GGTs, the role of this threonine residue in autoprocessing is still controversial.

FIGURE 3

Microenvironment for autocatalytic processing of Bacillus licheniformis gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (BlGGT). Crystal structure of T399A precursor mutant of BlGGT (PDB ID: 4Y23) has been used for studying autocatalytic environment. A399 is replaced by T399 to show hydrogen bonding (yellow dashed lines) and steric hindrance (brown lightning bolt) experienced by T399 for its proper positioning during autoprocessing. The structures are prepared using PyMOL2 software.

The role of residues present in the immediate vicinity of the cleavage site during autoprocessing was also explored. The residue preceding conserved nucleophile threonine was variable among microbial GGTs (Supplementary Figure 1). After autoprocessing, it acquired the last position of the newly formed C-terminus of the large subunit and was occupied by Gln390 in EcGGT and Glu398 in BlGGT. Analysis of four mutants, viz E398A, E398D, E398R, and E398Q of BlGGT, suggested that the C-terminal of the large subunit was indeed critical for autoprocessing of BlGGT (Chi et al., 2012). Among these, in three mutants, except E398Q, autoprocessing was hampered, which did not improve even after prolonged in vitro incubation. On the contrary, in EcGGT, replacement of the corresponding residue Q390 with alanine (Q390A) did not affect autoprocessing, indicating the insignificance of the large subunit C-terminus of EcGGT in autoprocessing (Hashimoto et al., 1995). The obtained contradictory results also possibly explain the low conservation of this residue among prokaryotic GGTs. Later, Chi et al. (2014) demonstrated the role of a 14-residue long extra sequence, exclusively present in Bacillus GGTs at the C-terminus of the large subunit, in autoprocessing, structural stability, and catalysis of BlGGT. They constructed six progressive deletion mutants within the extra sequence region with altered autoprocessing capabilities and variable catalytic activities (Chi et al., 2014). Further, the N-terminal of the small subunit, constituting a highly conserved TTH motif, was also investigated for its role in autoprocessing. The role of the first threonine residue, constituting the conserved nucleophile, in autoprocessing has been established well for many bacterial GGTs (Suzuki and Kumagai, 2002; Pica et al., 2012, 2016). In EcGGT, replacement of the second and third residue, respectively, with alanine (T392A) and glycine (H393G) impaired autoprocessing, suggesting that the small subunit N-terminus is more crucial than the large subunit C-terminus during autoprocessing (Hashimoto et al., 1995).

Apart from this, N- and C-termini of the intact polypeptide chain (prepro-GGT) of bacterial GGTs were also studied for their importance in autoprocessing. Truncation in the N-terminal region, including the signal peptide, of EcGGT and BlGGT demonstrated that signal peptide is critical for proper enzyme folding and processing (Lin et al., 2008; Lo et al., 2008). For EcGGT, truncation beyond 17 amino acids was found detrimental for maturation, indicating the crucial role of the last nine amino acids of the signal peptide in functional expression of the enzyme (Lo et al., 2008), while in BlGGT, all the truncated mutants except the native enzyme resulted in partial or complete loss of processing, emphasizing again on the importance of signal peptide in the enzyme’s folding and maturation (Lin et al., 2008). This is contradictory to the reports showing functional heterologous expression, with efficient autoprocessing, of EcGGT and BlGGT that lack signal peptide sequence (Lin et al., 2006; Yao et al., 2006). Similarly, N-terminal truncation in BpGGT up to 95 residues did not affect autoprocessing, but functional activity was lost with truncation beyond 63 residues (Murty et al., 2012). The importance of the C-terminus in autoprocessing has also been elucidated and was first demonstrated in EcGGT. Two arginyl residues present at the C-terminus of EcGGT were mutated with alanine (R513A) and glycine (R571G), resulting in a complete blockage of autocatalytic processing (Hashimoto et al., 1992). Further in HpGGT, the formation of salt bridges among four highly conserved residues, viz Glu515/Arg547 and Arg502/Asp562 at C-terminus, suggested their importance in enzyme processing. Disrupting salt bridges by mutating residue Glu515 (E515Q) and Arg502 (R502L) led to impaired autoprocessing and activity (Williams et al., 2009). C-terminal truncation in BlGGT revealed that deletion beyond V576, at ninth position from C-terminus, was detrimental for autoprocessing and activity (Chang et al., 2010).

Effect of Autoprocessing on Structure and Function of GGT

Structural analysis of EcGGT and HpGGT crystal structures showed that the new termini formed post autoprocessing are approximately 35 Å apart, which is quite distant, suggesting significant conformational changes during autoprocessing (Okada et al., 2006; Morrow et al., 2007). Further, comparing the overall structure of the mature and T391A precursor of EcGGT demonstrated that backbone atoms in the core regions of both the proteins remain unchanged, while significant conformational changes occurred proximal to the active site (Okada et al., 2007). Particularly after autoprocessing, the large subunit C-terminus (denoted as P-segment) flips out and is replaced by a flexible lid loop located in the smaller subunit. Adoption of an extended conformation by the P-segment has been suggested significant in forming binding pocket. However, these conformational changes do not occur in all microbial GGTs owing to the absence of lid loop as seen in Bacillus species. Analysis of the mature structures of BsGGT and BlGGT demonstrated that the C-terminus of large subunit possesses an extra sequence region located close to the N-terminus of the small subunit, suggesting no significant conformational changes upon autoprocessing (Wada et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2014). The extra sequence in BlGGT has been reported as important for autoprocessing and enzyme activity (Chi et al., 2014). Apart from structural implications, the correlation of autoprocessing with catalytic activity has also been well documented. Analysis of in vitro processing of native and mutant precursors of EcGGT and BlGGT, as a function of time, suggests that the extent of autoprocessing correlates well with increased enzyme activity (Suzuki and Kumagai, 2002; Lin et al., 2008). In GGTs like EcGGT, HpGGT, and BpGGT, uncoupling of autoprocessing and enzymatic activity has been attempted. Hashimoto et al. (1995) demonstrated that the coexpression of large and small subunit (using separate expression plasmid for each subunit) of EcGGT could result in reconstitution of two subunits under both in vivo and in vitro conditions. The retained activity was very less, indicating that only few molecules of the two subunits could fold properly and give rise to an active form (Hashimoto et al., 1995). In contrast, for HpGGT and BpGGT, coexpression of both the subunits in pET-DUET vector resulted in a fully active heterodimeric enzyme with comparable and enhanced activities (Boanca et al., 2006; Murty et al., 2012). This indicated that different bacterial GGTs can adopt different conformations; use of different expression systems can also effect both folding and active conformation of GGT, as uncoupling autoprocessing from enzymatic activity was successful for HpGGT and BpGGT but not for EcGGT.

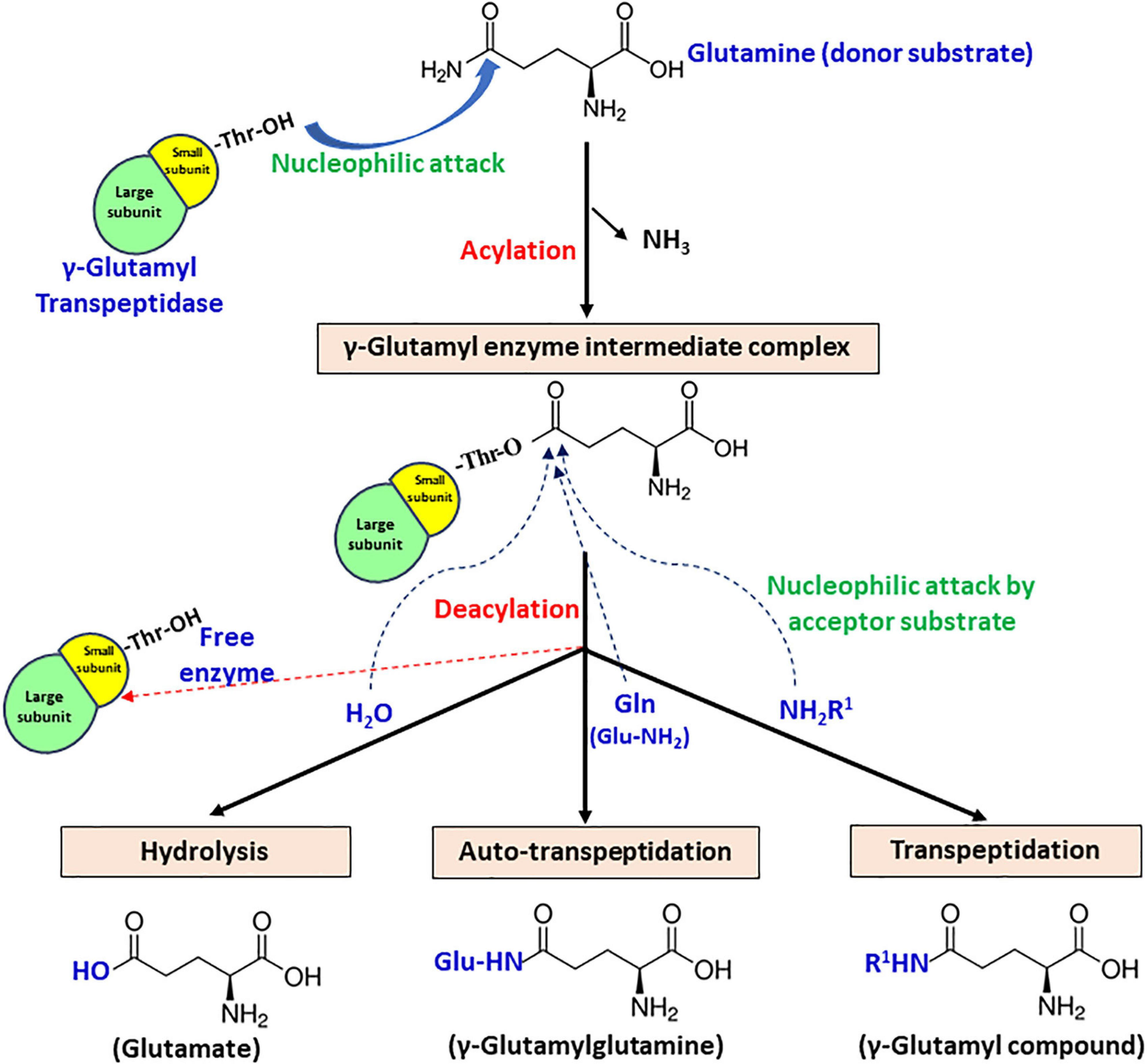

Catalysis Mediated via Nucleophile Threonine

Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase enzyme catalyzes a two-step reaction, involving cleavage of γ-glutamyl bond present in γ-glutamyl compounds like glutathione and glutamine subsequently, followed by transfer of γ-glutamyl moiety to a water molecule or another amino acid or short peptide (Tate and Meister, 1981). The first step is termed acylation, in which donor substrate donates γ-glutamyl moiety to the enzyme, forming an acyl-enzyme intermediate. In the second step termed deacylation, an acceptor substrate accepts γ-glutamyl moiety to form final end product (Figure 4). Based on the end product formation, GGT mediates three types of reactions.

FIGURE 4

Schematic representation of the proposed catalytic mechanism of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) with glutamine as the γ-glutamyl moiety donor.

-

1.

Hydrolysis – acceptor is a water molecule, with end-product glutamate.

-

2.

Transpeptidation – acceptor is an amine group containing compound that can be any amino acid or short peptide, and the end-product formed is a γ-glutamyl compound.

-

3.

Autotranspeptidation – acceptor is the donor molecule itself, and the end-product is γ-glutamylated donor.

The formation of an acyl-enzyme intermediate during catalysis has been substantiated by both kinetic and crystallographic studies. Stop-flow kinetics performed under presteady-state conditions using rat kidney GGT revealed a biphasic pattern of enzyme catalysis, confirming its ping-pong mechanism (Keillor et al., 2004). Based on the observation, it has been interpreted that the acylation step is faster, while the deacylation step is rate limiting (Keillor et al., 2005). For bacterial GGTs, further examination of the X-ray crystal structure of EcGGT soaked in glutathione for varying time intervals also demonstrated the formation of γ-glutamyl enzyme intermediate, indicating that the second step is much slower than the first (Okada et al., 2006). Further analysis of EcGGT in complex with substrate analogs, acivicin and azaserine, revealed that they formed a tetrahedral adduct (structurally analogous to transient acyl-enzyme intermediate) with the enzyme (Wada et al., 2008).

Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase-mediated reactions are known to be catalyzed by nucleophilic attack on the donor substrate. The N-terminal threonine residue of small subunit responsible for autoprocessing has also been reported as the relevant nucleophile in enzyme catalysis (Inoue et al., 2000). Inhibition of GGT activity by treatment with certain inhibitors like 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (DON) and serine–borate complex suggested the involvement of the hydroxyl group of either a serine or a threonine residue (Tate and Meister, 1977, 1978). However, Inoue et al. (2000) were the first group to identify that the conserved Thr391 is indeed the catalytic nucleophile for EcGGT. They employed mechanism-based affinity labeling to modify the putative active site of GGT using 2-amino-4-(fluorophosphono) butanoic acid (1), a γ-phosphonic acid monofluoride derivative of glutamic acid. The compound phosphonylated the putative catalytic nucleophile, and subsequent liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) and MS/MS analysis revealed that the small subunit N-terminal threonine is the catalytic nucleophile. Moreover, the structure of EcGGT in complex with glutathione clearly illustrates the formation of a covalent bond between the OG atom of Thr391 and carbonyl carbon of γ-glutamyl moiety of glutathione (Okada et al., 2006).

Analysis of the crystal structure of HpGGT also demonstrated the role of a second threonine (T398) residue in increasing nucleophilicity of the catalytic threonine (T380) (Boanca et al., 2007). It has been reported to be highly conserved among bacterial GGTs and suggested to interact with the hydroxyl group of the catalytic threonine, resulting in the formation of a TT dyad. Besides, the nucleophilicity of catalytic threonine has also been proposed to increase through interaction with its own α-amino group, which can act as a base to activate catalytic nucleophile threonine (Michalska et al., 2005; Boanca et al., 2007). The contribution of T398 in the activation of T380 in HpGGT was investigated by site-directed mutagenesis. Replacement of T398 with alanine (T398A) and serine (T398S) resulted in a complete and nearly fivefold reduction of enzymatic activity, respectively, with no maturational defects, suggesting the importance of TT dyad in efficient catalysis. A plausible explanation given for the same was the presence of a methyl group in T398, likely required for precise positioning of its side chain hydroxyl group for interaction with catalytic threonine (Boanca et al., 2007). Similarly, the replacement of the corresponding second threonine residue T417 with lysine, serine, and alanine in BlGGT also resulted in a dramatic decrease in activity as well as autoprocessing rate, indicating its functional significance in both autoprocessing and catalysis (Lyu et al., 2009).

Substrate Binding Pocket

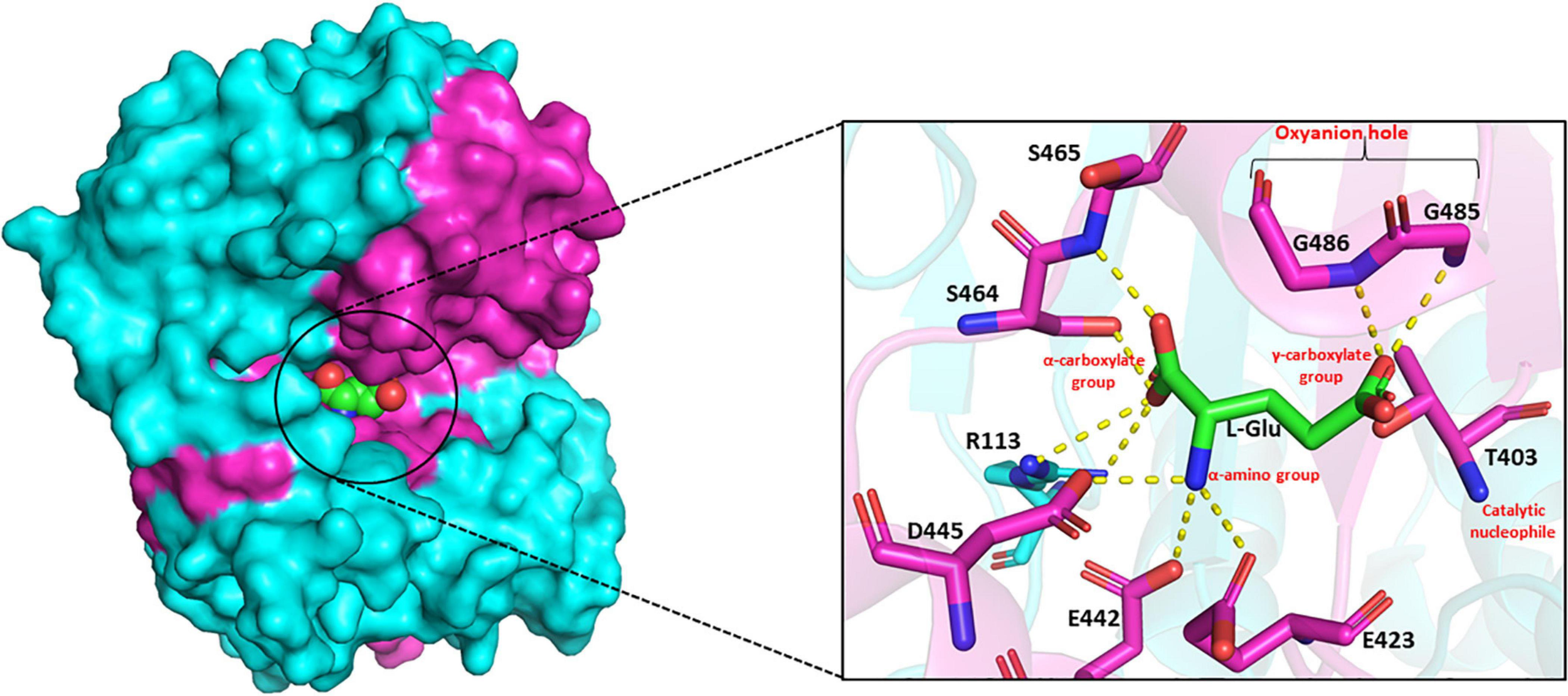

The substrate-binding pocket of GGT can be divided into two parts – the donor binding site and the acceptor binding site. The donor binding site interacts with γ-glutamyl moiety in the donor molecule, while the presence of a discrete acceptor binding site is still ambiguous. In mammalian GGTs, these sites have been reported to be largely overlapping (Thompson and Meister, 1977). However, in bacterial GGTs, the donor binding site has been determined to be highly conserved, while the acceptor binding site is reported highly variable. Analysis of the crystal structures of EcGGT, HpGGT, BsGGT, and BlGGT in complex with glutamate demonstrated that the catalytic pocket is enclosed within the shallow groove at the interface of both large and small subunits (Okada et al., 2006; Morrow et al., 2007; Wada et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2014). The binding pocket resides the catalytic threonine at the bottom of the groove on one of the central β-sheets, and it further extends into the enzyme, appearing as a finger-like projection. The γ-glutamyl moiety of the donor molecule is bound to the active site at the bottom of the pocket by an extensive network of hydrogen bonds and salt bridges formed mainly with the residues present in the small subunit (Okada et al., 2006). In BsGGT, the α-carboxylate group of the bound glutamate interacts with Arg113, Ser464, and Ser465, and the α-amino group interacts with Glu423, Glu442, and Asp445 (Figure 5; Wada et al., 2010). The glutamate carbonyl carbon is covalently bonded to the OG atom of threonine, while the carbonyl oxygen is hydrogen bonded to the main chain amino group of two glycine residues, Gly485 and Gly486. Arg113 is reported to be the only residue from, respectively, the large subunit involved in binding pocket formation. Residues forming the binding-pocket of mesophilic GGTs are mostly conserved, except differences of one or two residues, suggesting rigidity of the binding pocket: in EcGGT, Asn411 and Gln430 while Glu423 and Glu442 in BsGGT. On the contrary, GGTs from extremophiles exhibit variability in their catalytic residues with respect to their mesophilic counterparts as has been revealed by multiple sequence alignment (Supplementary Figure 1). For example, the highly conserved arginine residue (R107 in BlGGT; R113 in BsGGT; R114 in EcGGT), present in the large subunit of mesophilic GGTs, is replaced by serine (S68 in PtGGT and S85 in GtGGT) in extremophiles. Likewise, the two consecutive serine residues (Ser462/Ser463 in EcGGT) of small subunit are replaced by histidine and threonine (414His/415Thr in GtGGT) in GGTs from extremophiles. The different nature of these residues is suggested to be responsible for the differences in catalytic properties of mesophilic and extremophilic GGTs (Castellano et al., 2011).

FIGURE 5

Side view of surface drawing of Bacillus subtilis gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (BsGGT) (PDB ID: 3A75) showing the binding pocket groove and interaction of L-glutamic acid (L-Glu) with active site residues of BsGGT. Cyan color highlights large subunit, pink color highlights small subunit, and L-Glu is represented as a sphere in the surface drawing. Hydrogen bonding is represented as yellow dashed lines. The structures are prepared using PyMOL2 software.

Recent crystallographic studies on L-Glu-bound BlGGT demonstrated that its active site channel constitutes two extensive pockets at the intersubunit interface lined mainly by hydrophobic residues. In addition, substrate binding resulted in significant structural changes in BlGGT; particularly, there is a reordering of six residues at the C-terminus of the large subunit with suggested role in enzyme catalysis (Lin et al., 2014).

As GGT catalysis follows a ping-pong mechanism, it is assumed that it sequentially binds donor and acceptor molecules. It has been suggested that the acceptor molecule occupies the same site where initially the leaving group of the donor molecule binds, but nothing has been conclusively proven yet (Taniguchi and Ikeda, 1998). Hu et al. (2012) threw some light on the acceptor binding residues and their mode of interaction by computational and mutational studies performed using CapD protein from B. anthracis and HsGGT (Homo sapiens). Analysis of the structures of CapD and HsGGT suggested that the putative acceptor binding site is proximal to the donor binding site, located in the deep groove, and is highly variable and flexible as compared to the conserved and rigid donor binding site. Further, the putative acceptor binding site of HsGGT has been suggested to be formed by some polar residues like Asp46, Asn79, His81, Ser82, Tyr403, Gln476, and Lys562, while in CapD, Arg423 and Arg520 are substituted in place of Gln476 and Lys562. Both the residues Arg423 and Arg520 have been suggested to play a role in acceptor binding and imparting broader stereospecificity to CapD in accepting both L- and D-forms of amino acids as acceptors.

Interestingly, Pseudomonas nitroreducens GGT (PnGGT) exhibits higher hydrolytic activity than transpeptidase activity despite high sequence similarity with EcGGT (Imaoka et al., 2010). Recent crystallographic studies on PnGGT in complex with Gly–Gly acceptor demonstrated that the binding mode of Gly–Gly in the active site is probably the reason for its reduced activity as an acceptor (Hibi et al., 2019). The terminal amino group of Gly–Gly is oriented opposite to the nucleophilic active center. Moreover, tight packaging of three aromatic residues Trp385, Phe417, and Trp525 around the Gly–Gly binding pocket has been suggested to be advantageous for its binding; side chains of these residues are involved in the recognition of acceptor substrate. Phe417 is located in the lid loop, while Trp385 and Trp525 have been suggested to form side walls of the putative acceptor binding site. However, the hydrophobic pocket formed by the three aromatic residues has been suggested to shield the catalytic nucleophile from bulk solvent and activating hydrolysis. The functional significance of the putative acceptor site of PnGGT including Trp385, Phe417, and Trp525 has also been explored by mutational studies. Substitution of three aromatic residues with threonine (W385T), tyrosine (F417Y), and alanine (W525A), present at the corresponding positions in EcGGT, resulted in enhanced transpeptidase activity for all three mutants, while a 5–14% decrease in hydrolytic activity was observed. Likewise, in another report from Picrophilus torridus GGT (PtGGT), the replacement of an aromatic residue tyrosine at position 327 by asparagine (corresponding residue in EcGGT) introduced significant transpeptidase activity in PtGGT, while the native enzyme exhibited only hydrolytic activity (Rajput et al., 2013). Comparative docking of the acceptor ligand Gly–Gly in the structural model of PtGGT and its Y327N mutant identified some residues with suggested importance in acceptor recognition and binding. The acceptor Gly–Gly interacted with five residues (L87, E90, Y305, N327, S348) and perfectly docked in the binding pocket of Y327N.

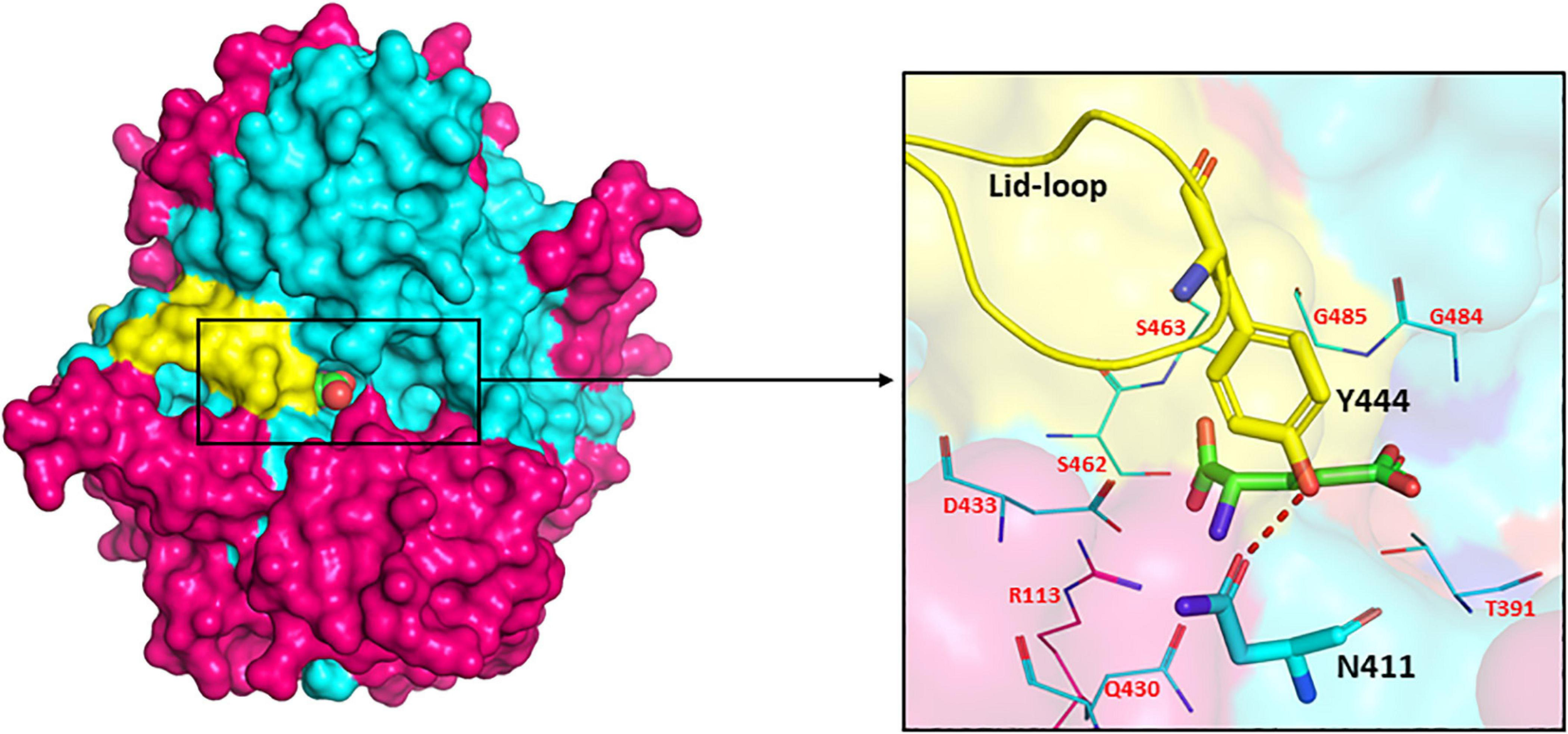

Importance of Lid Loop in Catalysis

The presence of a unique lid-loop region in the small subunit of GGT of different bacterial and mammalian homologues as shown in multiple sequence alignment (Supplementary Figure 1) has structural and functional significance. Analysis of substrate-bound crystal structures of EcGGT and HpGGT demonstrated that the otherwise flexible lid loop acquires a well-defined position after binding of the substrate and extends over the binding site pocket, shielding it from the solvent molecule (Okada et al., 2006). The lid-loop spanning segment from Pro438 to Gly449 in EcGGT contains an aromatic residue tyrosine (Try444), which has been reported to form a hydrogen bond with conserved residue Asn411 by its side chain hydroxyl group (Figure 6). The hydrogen bond has been suggested to act as a gate, restricting entry of the solvent molecule into the active site and also regulating access of the substrate to the active site cleft that results in a rigid structural conformation around the binding pocket. A similar hydrogen bond has been reported between Tyr433 of the lid loop and Asn400 in HpGGT (Morrow et al., 2007). The shielding likely occludes water molecules from entering the active site, facilitating transpeptidation. However, human GGT exhibits higher transpeptidase activity, likely associated with higher mobility of its lid loop allowing rapid switch of its structural conformation from open to close resulting in faster product release (Hu et al., 2012). Analysis of recently determined crystal structure of human GGT also confirms high mobility of the lid loop (West et al., 2013). The probable explanation ascribed is the replacement of tyrosine with phenylalanine (Phe444), causing a lack of stabilizing hydrogen bond. In HpGGT, substitution of Try433 with Phe (Y433F) had no effect on the catalytic activity, but mutation with alanine (Y433A) resulted in a dramatic decrease in activity; substrate binding was, however, not affected (Morrow et al., 2007).

FIGURE 6

Surface drawing of Escherichia coli gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (EcGGT) (PDB ID: 2DBX) showing the arrangement of lid-loop around substrate-binding pocket. Pink color highlights large subunit, cyan color highlights small subunit, and L-Glu is represented as a sphere in the surface drawing. Hydrogen bonding between residues Asn411 and Tyr444 is shown by the red dotted line. The active site residues surrounding the bound substrate L-Glu are pictorially shown as lines. The structures are prepared using PyMOL2 software.

Several microbial GGTs including BsGGT, BlGGT, GtGGT, TaGGT, PtGGT, DnGGT, and TtGGT lack the lid-loop segment. Structural analysis of BsGGT and BlGGT demonstrated that their binding pocket is solvent exposed, as they lack lid loop or any of that sort to cover the active site. They are thus suggested to have an open active site cleft to accommodate hydrolysis of large polymeric substrates like PGA (Wada et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2014). Based on this correlation between the absence of lid loop and hydrolysis of higher molecular weight substrates, it has been proposed that lid loop containing enzymes would not be able to utilize polymeric substrates due to closed catalytic pocket. In an interesting study by Calvio et al. (2018), the role of lid loop in substrate selection was investigated where they constructed a mutant BsGGT by inserting the lid loop from EcGGT. On comparing the activities of EcGGT (lid loop), BsGGT (no lid loop), and mutant BsGGT (lid loop), they concluded that entry of substrate into the active site was regulated by the lid loop depending on molecular weight. Both EcGGT and mutant BsGGT could efficiently utilize glutamine than bulky PGA. Moreover, the presence of the lid loop in mutant BsGGT enhanced its transpeptidation activity as compared to EcGGT and BsGGT (Calvio et al., 2018).

Mutations in Binding Pocket

Site-directed mutagenesis of the active site residues of microbial GGTs has contributed significantly in determining their functional role and also in the development of catalytically efficient variants (Table 3). As already mentioned, the only residue of the large subunit reported to participate in catalysis is the conserved arginine (Arg114 in EcGGT, Arg113 in BsGGT, Arg109 in BlGGT). This residue has been reported to form a weak interaction with the α-carboxylate group of donor substrate (Ikeda et al., 1993; Okada et al., 2006). However, the role of this residue has been elucidated in substrate recognition and binding rather than direct involvement in catalysis. In BlGGT, replacement of this arginine with another positively charged residue lysine (R109K) resulted in significant enhancement of activity (Bindal et al., 2017), whereas in EcGGT (R114K) and BsGGT (R113K), similar mutation resulted in 93 and 22% residual activities, respectively (Minami et al., 2003a; Ong et al., 2008). Substitutions with amino acids of different functional nature such as Leu, Met, Asp, Glu, Phe, etc., were detrimental (Table 3). R109M and R109L mutants of BlGGT exhibited only hydrolytic activity (Bindal et al., 2017).

TABLE 3

| Residue | Mutation | Effect | References | Suggested functional role |

| Arg113 in large subunit of EcGGT* | ||||

| Arg114 (EcGGT) | R114K | 93% activity retained | Ong et al., 2008 | Substrate recognition and binding |

| R114L | No detectable activity | |||

| R114D | No detectable activity | |||

| Arg113 (BsGGT) | R113K | Reduced activity by 78% | Minami et al., 2003a | |

| Arg109 (BlGGT) | R109K | 2-fold enhancement in activity | Bindal et al., 2017 | |

| R109S | 85% activity retained | |||

| R109L | Abolished transpeptidase activity; 5% hydrolytic activity retained | |||

| R109M | Abolished transpeptidase activity; 4% hydrolytic activity retained | |||

| R109F | No detectable activity | |||

| R109E | No detectable activity | |||

| Thr391 at small subunit N-terminal of EcGGT | ||||

| Thr391 (EcGGT) | T391A | No autoprocessing and detectable activity | Suzuki and Kumagai, 2002 | Catalytic nucleophile crucial for both autoprocessing and activity |

| T391S | Impaired autoprocessing and activity (values not mentioned) | |||

| T391C | Impaired autoprocessing and activity (values not mentioned) | |||

| Thr380 (HpGGT) | T380A | No autoprocessing and detectable activity | Boanca et al., 2006 | |

| T380S | Impaired autoprocessing; reduced activity by 92% | |||

| Thr399 (BlGGT) | T399A | No autoprocessing and detectable activity | Lyu et al., 2009 | |

| T399S | Impaired autoprocessing; reduced activity by 89% | |||

| T399C | No autoprocessing and detectable activity | |||

| Thr353 (GtGGT) | T353A | No autoprocessing; retained some activity (values not mentioned) | Castellano et al., 2010 | |

| Asp433 in small subunit of EcGGT | ||||

| Asp445 (BsGGT) | D445A | Abolished transpeptidase activity; 40% hydrolytic activity retained | Minami et al., 2003a | Substrate binding and its affinity |

| D445E | Reduced activity by 86% | |||

| D445N | Reduced activity by 90%; cephalosporin acylase activity increased by 55-fold | |||

| D445Y | Reduced activity by 91% | |||

| E423Y/E442Q/D445N | Cephalosporin acylase activity enhanced by 963-fold | Suzuki et al., 2010 | ||

| Asp433 (EcGGT) | D433N | Abolished transpeptidase activity 82% hydrolytic activity retained; introduced cephalosporin acylase activity | Suzuki et al., 2004c | |

| D433N/Y444A/G484A | Cephalosporin activity enhanced by 50-fold | Yamada et al., 2008 | ||

| Gly484 and Gly485 in small subunit of EcGGT | ||||

| Gly481 (BlGGT)# | G481A | 80% autoprocessed with 78% activity retained | Chi et al., 2018 | Stabilization of oxyanion hole during catalysis; crucial for both autoprocessing and catalysis |

| G481R | Complete loss of autoprocessing and activity | |||

| G481E | 60% autoprocessed with 13% activity retained | |||

| Gly482 (BlGGT)# | G482A | 95% processed; retained 70% activity | ||

| G482R | 20% processed; no detectable activity | |||

| G482E | 80% processed; significant loss in activity (4% left) | |||

| PLSSMXP motif in small subunit of EcGGT (Pro460, Leu461, Ser462, Ser463, Met464, Pro466) | ||||

| P458 (BlGGT) | P458A | 25% increase in activity | Chi et al., 2019b | Crucial for both autoprocessing and catalysis |

| L459 (BlGGT) | L459A | No effect on activity | ||

| S460 (BlGGT) | S460A | 2.1-fold enhancement in activity | ||

| S461 (BlGGT) | S461A | 2.4-fold enhancement in activity | ||

| S463 (EcGGT) | S463T | Reduced activity by 40% | Hsu et al., 2009 | |

| S463K | No autoprocessing and detectable activity | |||

| S463D | No autoprocessing and detectable activity | |||

| M462 (BlGGT) | M462A | 37% increase in activity | Chi et al., 2019b | |

| M464 (EcGGT) | M464E | No autoprocessing and detectable activity | Lo et al., 2007 | |

| M464K | No autoprocessing and detectable activity | |||

| M464L | Reduced activity by 50% | |||

| P464 (BlGGT) | P464A | Reduced activity by 53% | Chi et al., 2019b | |

| Deletion mutants (BlGGT) | △M462 | No autoprocessing and detectable activity | Chi et al., 2019b | |

| △S460-M462 | ||||

| △S461-M462 | ||||

| △P464 | ||||

| Asp452 residue in small subunit of EcGGT | ||||

| Asn450 (BlGGT)† | N450Q | 41% increase in transpeptidase activity | Lin et al., 2016 | Substrate binding and catalysis |

| N450A | 3.5-fold enhancement in transpeptidase activity | |||

| N450D | 3.6-fold enhancement in transpeptidase activity | |||

| N450K | Reduced activity by 27% | |||

List of mutations performed in conserved and catalytically important residues of bacterial gamma-glutamyl transpeptidases (GGTs) and their effect on autoprocessing and activity.

*The residues have been numbered according to their corresponding position in E. coli GGT for ease in reading the table. The activities mentioned in the table are transpeptidase activities measured in presence of both donor and acceptor; hydrolytic activity wherever mentioned is measured only with donor without the addition of any acceptor substrate.#The transpeptidase activity was recorded after an incubation of 21 days at 4°C.†Transpeptidase and hydrolytic activities were recorded after 10 days of incubation at 4°C.

Another active site residue of the small subunit (Asp445 in BsGGT) reported to interact with the α-amino group of donor substrate has also been suggested to have a putative role in substrate binding (Minami et al., 2003a). Replacement of Asp445 by alanine (D445A) resulted in a hydrolytic variant with 40% retained activity and complete abolishment of transpeptidase activity with respect to native BsGGT (Minami et al., 2003a). Likewise, substitution of the corresponding residue Asp433 with asparagine (D433N) in EcGGT abolished its transpeptidase activity, and the hydrolytic variant evolved retained almost 82% activity (Suzuki et al., 2004c). D433N mutant could catalyze deacylation of glutaryl-7-aminocephalosporanicacid (GL-7-ACA) producing 7-aminocephalosporanic acid, a starting material for the synthesis of semisynthetic cephalosporins. GGTs share 30% sequence homology with class IV cephalosporin acylases (CAs) that synthesize semisynthetic cephalosporins. The conserved Asp433 residue of EcGGT is replaced by asparagine in class IV CAs; point mutation (D433N) introduced CA activity in EcGGT, although the acylase activity was quite low; introduction of two random mutations of Y444A and G484A to D433N resulted in up to 50-fold increase in catalytic efficiency for GL-7-ACA substrate (Yamada et al., 2008). Similarly, a triple mutant E423Y/E442Q/D445N of BsGGT was also developed with enhanced acylase activity (Suzuki et al., 2010).

The functional role of two fully conserved tandem glycine repeats reported to form the oxyanion hole has also been explored (Chi et al., 2018). In BlGGT, substituting residues Gly481 and Gly482, respectively, with arginine (G481R) and lysine (G481K) led to impaired autoprocessing as well as catalytic activity, while alanine substitution was not detrimental (Table 3). It has been suggested that proper positioning of the glycine residues is critical for both autoprocessing and catalysis (Chi et al., 2018).

Recently, a highly conserved 458PLSSMXP464 motif present in the small subunit of BlGGT containing the two catalytic serine residues has been studied by deletion and alanine scanning mutagenesis (Chi et al., 2019b). All the deletion mutants showed complete loss of processing and activity. However, alanine substituent of four residues Pro458 (P458A), Ser460 (S460A), Ser461 (S461A), and Met462 (M462A) exhibited a significant increase in catalytic activity with no maturational defects (Table 3). Interestingly, S460A and S461A displayed about twofold enhancement in activity; the role of catalytic Ser463 in EcGGT corresponding to Ser461 in BlGGT was also investigated by mutating it to aspartate (S463D), lysine (S463K), and threonine (S463T). Variants S463D and S463K of EcGGT showed no detectable activities with considerable maturational defects (Hsu et al., 2009), while S463T mutant displayed 40% loss in activity without affecting autoprocessing, indicating that presence of hydroxyl group is required for autoprocessing and addition of charged residues at this position is detrimental for both processing and activity. The same phenomenon was observed for Met464 residue in EcGGT (Met462 in BlGGT) wherein M464E and M464K were maturationally blocked mutants, while M464L exhibited no loss in autoprocessing but had a 50% loss in activity (Lo et al., 2007).

Analysis of the L-Glu-bound crystal structure of BlGGT (PDB ID: 4OTU) suggested importance for another highly conserved residue, Asn450, located close to the binding pocket, in proper substrate orientation (Lin et al., 2016). Replacement of Asn450 by glutamine (N450Q), aspartate (N450D), and alanine (N450A) showed a significant increase in transpeptidase activity up to 3.6-fold enhancement and minor maturational defects, suggesting significant contribution of this residue in substrate binding and catalysis.

Based on mutations in catalytically conserved residues of bacterial GGTs, it was observed that contradictory results were obtained for similar mutations in different bacterial GGTs concerning autoprocessing and catalytic activities (Table 3). The possible reason for the same may be attributed to minor differences in the autoprocessing microenvironments and active structural conformations of different bacterial GGTs. For example, the presence of the lid loop in EcGGT can also influence its catalysis in comparison to Bacillus GGTs lacking the lid-loop region.

Physicochemical Properties of Bacterial GGTs

Wild strains like E. coli and Bacillus species produced very low titers of GGT, as it is a stress-related enzyme (Suzuki et al., 1987; Minami et al., 2003b). Further, cultivation of extremophilic organisms like G. thermodenitrificans, D. radiodurans, etc., is rather difficult; therefore, bacterial GGTs have been largely expressed heterologously in E. coli and B. subtilis via conventional methods for their biochemical and biophysical characterization (Table 4).

TABLE 4

| S. No. | Enzyme Source | Expression Host | Purification | Specific activity (U/mg) | Remarks | References |

| 1. | E. coli K-12 | GGT deficient E. coli K-12 | Two-step; ammonium sulfate precipitation and chromatofocusing | 3.0 | 37-fold enhanced expression; 4.4-fold purification with 42% yield | Suzuki et al., 1988 |

| 2. | E. coli Novablue | E. coli M15 | One-step; Ni-NTA affinity chromatography utilizing N-terminal His6 tag | 4.25 | 32.7-fold purification with 83% yield | Yao et al., 2006 |

| 3. | Bacillus licheniformis ATCC 27811 | E. coli M15 | One-step; Ni-NTA affinity chromatography utilizing N-terminal His6 tag | 185. 6 | 29-fold purification with 26 mg/L yield | Lin et al., 2006 |

| 4. | Geobacillus thermodenitrificans NG80-2 | E. coli BL21 (DE3) | One-step; Ni-NTA affinity chromatography utilizing C-terminal His6 tag | 0.36 (hydrolytic) | 10 mg/L purification yield; no transpeptidase activity | Castellano et al., 2010 |

| 5. | Pseudomonas nitroreducens IFO12694 | E. coli Rosetta-gami B (DE3) | Two-step; DEAE cellulofine and Butyl FF column chromatography | 30.2 (hydrolytic); 2.98 (transpeptidase) | 70-fold enhanced expression; high hydrolytic activity | Imaoka et al., 2010 |

| 6. | Thermus thermophilus | E. coli BL21 (DE3) | One-step; Ni-NTA affinity chromatography utilizing C-terminal His6 tag | 0.151 (hydrolytic) | No transpeptidase activity | Castellano et al., 2011 |

| 7. | Deinococcus radiodurans | E. coli BL21 (DE3) | One-step; Ni-NTA affinity chromatography utilizing C-terminal His6 tag | 0.060 (hydrolytic) | No transpeptidase activity | Castellano et al., 2011 |

| 8. | E. coli | E. coli BL21 (DE3) | One-step; Ni-NTA affinity chromatography utilizing N-terminal His6 tag | 51.41 (U/ml) | High transpeptidase activity; high purification yield of 62 mg/L | Wang et al., 2011 |

| 9. | Bacillus pumilus KS12 | E. coli BL21 (DE3) | One step; Ni-NTA affinity chromatography utilizing C-terminal His6 tag | 1.82 (hydrolytic); 4.35 (transpeptidase) | High hydrolytic activity | Murty et al., 2012 |

| 10. | Picrophilus torridus DSM 9790 | E. coli Rosetta | One-step; Ni-NTA affinity chromatography utilizing C-terminal His6 tag | 18.92 (hydrolytic) | Addition of 2% hexadecane enhanced production ∼10 times; no transpeptidase activity | Rajput et al., 2013 |

| 11. | Bacillus licheniformis ER-15 | E. coli BL21 (DE3) | Two-step; acetone precipitation and Q-sepharose anion exchange chromatography | 4.58 | 10.2-fold purification with 28.8 % yield | Bindal and Gupta, 2014 |

| 12. | Pseudomonas protegens Pf-5 | E. coli BL21 (DE3) | One-step; Ni-NTA affinity chromatography utilizing C-terminal His6 tag | 31.06 (hydrolytic); 4.28 (transpeptidase) | High hydrolytic activity | Kushwaha and Srivastava, 2014 |

| 13. | Pseudomonas fluorescence PfT-1 | E. coli BL21 (DE3) | One-step; Ni-NTA affinity chromatography utilizing C-terminal His6 tag | 36.67 (hydrolytic); 5.45 (transpeptidase) | High hydrolytic activity | Kushwaha and Srivastava, 2014 |

| 14. | Pseudomonas syringae | E. coli Rosetta-gami B (DE3) | Two-step; DEAE cellulofine and Butyl toyopearl column chromatography | 0.92 (transpeptidase) | Low purification yield (1.83%) due to protein instability | Prihanto et al., 2015a |

| 15. | Bacillus licheniformis | E. coli BL21 (DE3) | One-step; Ni-NTA affinity chromatography utilizing N-terminal His6 tag | − | High protein yield of 150–200 mg/2 L | Kumari et al., 2017 |

| 16. | Bacillus licheniformis ER-15 | E. coli BL21 (DE3) | − | 9000 U/L (extracellular activity); 3000 U/L (intracellular activity) | 75–80% extracellular translocation using native signal of the enzyme | Bindal et al., 2018 |

| 17. | Bacillus subtilis 168 | Sporulation-deficient B. subtilis 168 | Two-step; Gigapite and SOURCE 15Q PE column chromatography | 7.49 (hydrolytic); 100 (transpeptidase) | 15-fold higher expression; 30% purification yield | Minami et al., 2003b |

| 18. | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SMB469 | B. subtilis KCTC 3135 | − | 24.7 (U/ml) | 23 times higher expression | Lee et al., 2017 |

| 19. | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens BH072 | B. subtilis 168 | One-step; Ni-NTA affinity chromatography utilizing His6 tag | 55 | Use of dual signal peptide enhanced secretion to 1.6 times; high purification yield of 90 mg/L | Mu et al., 2019 |

| 20. | Bacillus pumilus ML413 | B. subtilis 168 | Two-step; acetone precipitation and Ni-NTA affinity chromatography utilizing His6 tag | 18.65 (U/ml) | Addition of poly(T/A) tail to ggt mRNA and coexpression of PrsA lipoprotein resulted in 60% high GGT production and 2-fold enhanced extracellular expression | Yang T. et al., 2019 |

Heterologous expression of prokaryotic gamma-glutamyl transpeptidases (GGTs).

Bacterial GGTs are distantly related to plant and mammalian GGTs in terms of their biochemical characteristics (Castellano and Merlino, 2012), but large variations exist among bacterial homologues; for example, Bacillus GGTs are 20–35 times catalytically more efficient than EcGGT (Lyu et al., 2009). Extremophilic bacterial GGTs exhibit only hydrolytic activity suggesting them to be the ancient progenitors that evolved earliest with only hydrolytic activity, and later, transpeptidase activity was imparted to other mesophilic bacterial and eukaryotic GGTs (Castellano et al., 2010, 2011).

Biochemical properties of prokaryotic GGTs are not very diverse, and they optimally function at alkaline pH ranging from 8.0 to 11.0 with different pH optima for hydrolysis and transpeptidation reactions (Balakrishna and Prabhune, 2014; Morelli et al., 2014). Most bacterial GGTs are stable over a wide pH range (6.0–11.0) with maximum stability at alkaline pH range (Shuai et al., 2011; Murty et al., 2012; Bindal and Gupta, 2014; Mu et al., 2019); this is due to the alkaline pKa of GGT substrates, which is above pH 9.0. Moreover, the enzyme can be controlled to catalyze hydrolysis, transpeptidation, or autotranspeptidation simply by adjusting reaction pH (Morelli et al., 2014). Bacterial GGTs exhibit highly variable thermal stability (Castellano et al., 2010) and are reported to optimally catalyze reactions between 37 to 60°C (Castellano and Merlino, 2012). Inhibition in enzyme activity after addition of amino-acid-specific inhibitors like N-bromosuccinimide and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride suggested crucial involvement of a tryptophan and serine/threonine residue (Suzuki et al., 1986; Shuai et al., 2011; Bindal and Gupta, 2014). Cysteine-protease inhibitors like β-mercaptethanol, dithiothreitol, and iodoacetamide show only marginal inhibition due to lack of sulfhydryl groups (Moallic et al., 2006; Rajput et al., 2013). GGT-specific substrate analogs like DON and azaserine show complete inhibition (Bindal and Gupta, 2014; Kushwaha and Srivastava, 2014). Metal chelating agents ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA) exhibit moderate inhibition, suggesting contribution of a metal ion in the active conformation of enzyme. The catalytic activity of some bacterial GGTs is reported to enhance with divalent cations such as Mg2++ and Ca2+; however, GGT is not considered to be a metallopeptidase and is sensitized by most of the heavy metal ions like Zn2+, Cd2+, Hg2+, and Pb2+ (Lin et al., 2006; Yao et al., 2006; Shuai et al., 2011; Kushwaha and Srivastava, 2014).

The determination of salt tolerance capacity of bacterial GGTs also characterizes them as halophilic and nonhalophilic. GtGGT is considered the most halotolerant, as it retains more than 90% of its hydrolytic activity in 4 M NaCl, followed by BsGGT retaining 86% of its hydrolytic activity at 3 M NaCl, while EcGGT lost 90% of its hydrolytic activity at the same salt concentration (Wada et al., 2010; Pica et al., 2013). BlGGT has also been reported to tolerate 4 M NaCl concentration without significant effect on its activity (Yang et al., 2011). The underlying mechanism for halotolerance has been reported to be associated with the presence of a relatively large number of negatively charged residues (aspartate and glutamate) on the solvent-exposed surfaces of GtGGT and BsGGT structures even at high salt concentrations resulting in increased water binding capacity, thus increasing solvation of the protein and preventing self-aggregation. EcGGT has also been reported to have acidic residues patches on its surface; however, they are not maintained at the surface under hypersaline conditions (Wada et al., 2010).

Bacterial GGTs exhibit broad substrate specificity for amino acids and other amine-group containing compounds like ethylamine, taurine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) as acceptors and can thus synthesize a variety of γ-glutamyl compounds utilized in food and pharmaceutical industries. Dipeptides like glycyl glycine and glycyl-L-alanine are fairly good acceptors for bacterial GGTs, with the former being the best (Ogawa et al., 1991; Moallic et al., 2006). Monomeric L-arginine and L-lysine seem to be good acceptors, while L-alanine, L-serine, L-glutamine, and L-glutamic acids have been reported to be poor acceptors (Lee et al., 2017); the propensity of hydrophobic and aromatic amino acids like L-methionine, L-phenylalanine, and L-DOPA is quite good compared to branched acceptors (Suzuki et al., 1986; Ogawa et al., 1991; Shuai et al., 2011). Interestingly, EcGGT poorly accepts D-amino acids, while Bacillus GGTs can accept both L- and D-isomers, thus showing relaxed stereoselectivity at the acceptor site (Ogawa et al., 1991; Hu et al., 2012).

Biophysical characterization of bacterial GGTs has been done to understand the molecular basis of enzyme stability. Temperature- and guanidine hydrochloride (GdnHCl)-induced unfolding of mature and precursor mimic (T399A mutant) forms of BlGGT using CD and emission fluorescence revealed that the mature form was structurally more stable and that both forms displayed an irreversible two-state pattern of thermal unfolding (Hung et al., 2011). A similar analysis showed that EcGGT was more sensitive toward thermal and chemical denaturation than BlGGT, which was more salt stable also (Yang et al., 2011). On the other hand, mature and precursor mutant (T353A) of GtGGT behaved differently; the thermal unfolding of both forms interestingly showed a three-state model including a stable intermediate species, and they exhibited remarkable temperature stability owing to strong electrostatic interactions but were sensitive toward GdnHCl (Pica et al., 2012). In another report, Ho et al. (2013) showed that heat-denatured EcGGT was renatured into active conformation upon incubation at 4°C, while BsGGT showed no such renaturation. They have suggested, based on biophysical characterization and native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) analysis, that EcGGT dissociated into individual subunits upon heat treatment, which reassembled into active conformation at 4°C (Ho et al., 2013).

Immobilization of Bacterial GGTs

Immobilization of industrially relevant enzymes has been suggested to offset the cost of the process utilizing such enzymes and in circumventing problems of enzyme destabilization (Mohamad et al., 2015). Bacterial GGTs like EcGGT, BsGGT, and BlGGT have been extensively explored for their potential as industrial biocatalysts in the synthesis of a wide variety of γ-glutamyl compounds like L-theanine, γ-glutamyl taurine, γ-D-glutamyl-l-tryptophan, etc., with huge biotechnological applicability (Suzuki et al., 2002a, 2004a; Wang et al., 2008; Bindal and Gupta, 2014). Thus, immobilization has been mainly focused on these three enzymes using various techniques ranging from simple entrapment method to covalent linkage with a suitable support matrix (Table 5) to reduce enzyme production cost and to increase enzyme reusability and stability. However, there are only a few reports of GGT enzyme immobilization that might be attributed to the heterodimeric composition of the enzyme that makes it difficult to remain in the active conformation after immobilization.

TABLE 5

| S. No. | Enzyme | Immobilization matrix | Immobilization method | Cross-linking agent | Loading capacity/immobilization efficiency | Recyclability | Storage stability | Comments* | References |

| 1. | EcGGT | Ca-alginate-k-carrageenan beads | Entrapment | − | 1.5 mg enzyme/g of alginate | ∼55% activity retained after 6 cycles | 50% residual activity after 35 days of storage | Improve thermal stability at 40°C; improved storage stability | Hung et al., 2008 |

| 2. | BlGGT | Ca-alginate beads | Entrapment | − | 40–45% activity recovered; 0.02 U/mg of beads | >90% activity retained after three cycles | Not mentioned | Improve thermal stability at 60°C with >80% residual activity after 15 min | Bindal and Gupta, 2014 |

| 3. | BlGGT | Amino silane coated iron magnetic nanoparticles | Covalent linkage | Glutaraldehyde | 32.4 mg/g of support; 52.4% activity recovered | ∼36% activity retained after 10 cycles | 82% residual activity rafter 30 days of storage | Comparable thermal and storage stability | Chen et al., 2013 |

| 4. | BlGGT | HBPAA-modified magnetic nanoparticles | Covalent linkage | NHS/EDC | 16.2 mg/g of support; 47.4% activity recovered | ∼32% activity retained after 10 cycles | 98% residual activity after 63 days of storage | Slightly improved pH stability in alkaline pH range; comparable thermal and storage stability | Juang et al., 2014 |