94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 30 October 2020

Sec. Antimicrobials, Resistance and Chemotherapy

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.596942

Previous studies on vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) have mainly focused on drug resistance, the evolution of differences in virulence between VISA and vancomycin-sensitive S. aureus (VSSA) requires further investigation. To address this issue, in this study, we compared the virulence and toxin profiles of pair groups of VISA and VSSA strains, including a series of vancomycin-resistant induced S. aureus strains—SA0534, SA0534-V8, and SA0534-V16. We established a mouse skin infection model to evaluate the invasive capacity of VISA strains, and found that although mice infected with VISA had smaller-sized abscesses than those infected with VSSA, the abscesses persisted for a longer period (up to 9 days). Infection with VISA strains was associated with a lower mortality rate in Galleria mellonella larvae compared to infection with VSSA strains (≥ 40% vs. ≤ 3% survival at 28 h). Additionally, VISA were more effective in colonizing the nasal passage of mice than VSSA, and in vitro experiments showed that while VISA strains were less virulent they showed enhanced intracellular survival compared to VSSA strains. RNA sequencing of VISA strains revealed significant differences in the expression levels of the agr, hla, cap, spa, clfB, and sbi genes and suggested that platelet activation is only weakly induced by VISA. Collectively, our findings indicate that VISA is less virulent than VSSA but has a greater capacity to colonize human hosts and evade destruction by the host innate immune system, resulting in persistent and chronic S. aureus infection.

Staphylococcus aureus is a major multidrug−resistant opportunistic pathogen in healthcare settings that represents a significant public health burden (Deresinski, 2005). Acquisition of the mecA gene encoding penicillin-binding protein 2 conferring methicillin resistance (Kobayashi et al., 2002) has led to the emergence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), which is responsible for thousands of infections annually and contributes to the growing problem of hospital-acquired (HA) infections (Oliveira et al., 2002). Glycopeptides such as vancomycin are the primary treatment option for severe infections caused by Gram-positive bacteria, including MRSA and most strains of multidrug-resistant S. aureus (Walsh, 1999).

Vancomycin resistance in Gram-positive bacteria was first reported in Enterococcus faecium in 1988 (Leclercq et al., 1988). The transfer of genetic elements containing the vancomycin resistance gene vanA from E. faecalis to S. aureus was discovered in 1992 (Noble et al., 1992). In 1997, the first clinical S. aureus strain (Mu50) with decreased susceptibility to vancomycin [minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) = 8 μg/ml] was isolated in Japan (Hiramatsu et al., 1997; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002b), and was designated as vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA). At the same time, S. aureus strains exhibiting a heterogeneous (h)VISA phenotype (Mu3) were isolated from clinical specimens (Hiramatsu et al., 1997). The first completely resistant clinical isolate of S. aureus (MIC > 1,024 μg/ml) was reported in July 2002 in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2002a).

Most studies on VISA/hVISA have focused on drug resistance, and the virulence of VISA/hVISA compared to vancomycin-sensitive S. aureus (VSSA) requires further investigation, although VISA is known to have a thicker cell wall (Cui et al., 2000; Howden et al., 2006; Katayama et al., 2009). To address this issue, the present study investigated the ability of VISA and VSSA strains to infect or colonize skin and soft tissue as well as the possible determinants of chronic infection by VISA. We compared the virulence of vancomycin-resistant S. aureus and VISA strains derived from Chinese HA-MRSA lineages to that of VSSA strains of the same lineage using rodent and insect infection models and a rodent colonization model along with in vitro assays. We also carried out a comparative RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis to evaluate differences in the expression of toxin genes between VISA and VSSA.

Detailed information on each isolate used in the study is shown in Table 1. The clinical S. aureus strain SA0534 and laboratory-induced vancomycin resistance strains (SA0534-V8 and SA0534-V16) were obtained from Yuanyuan Dai at The Affiliated Provincial Hospital of Anhui Medical University (Chang et al., 2015). VS-2393 and VI-2562 strains were isolated from different patients in Xinjiang Province, while VS-1201 and VI-1130 were isolated from patients in Guangdong Province.

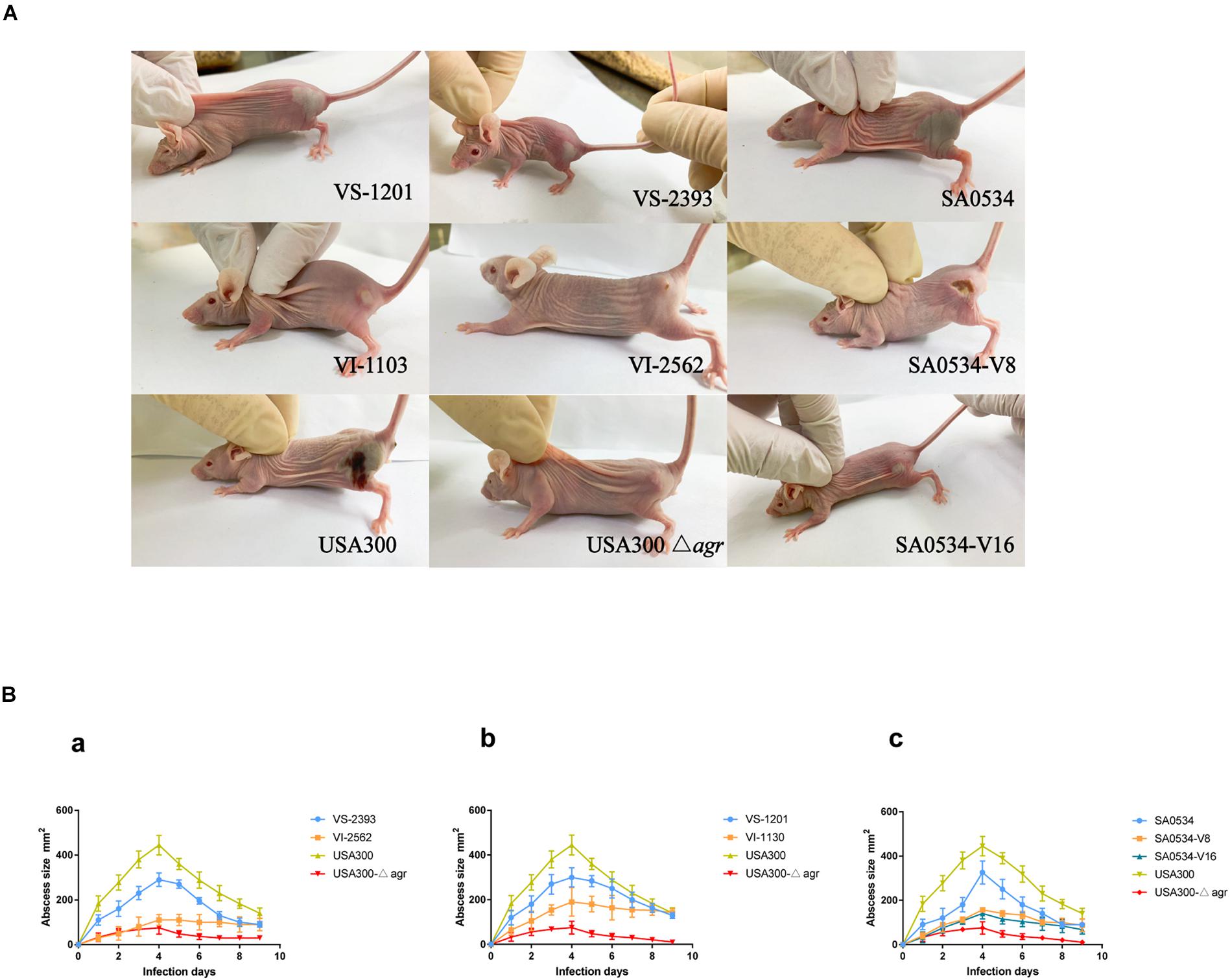

The mouse skin infection model was established as previously described (Li et al., 2010) using 6-week old female BALB/C-nude mice. The mice were housed for 1 week with free access to food and water prior to infection with S. aureus. S. aureus strains were grown for 16 h, washed 3 times with sterile NaCl solution. Then 2 × 108 bacterial cells were suspended in 100 μl NaCl solution. Mice were injected with the S. aureus suspension (100 μl) or with sterile NaCl solution as a negative control. Skin abscesses that developed in the mice were monitored daily for 9 days, and their length (L) and width (W) were measured using calipers. The abscess area was calculated as area = L × W. After all animals were euthanized, skin lesions were compared between mice infected with VISA vs. VSSA strains (n = 6 mice per group). The community-associated MRSA strain USA300_FPR3757 was used as a positive control for its high virulence, while the USA300△agr mutant served as the negative control.

S. aureus strains were inoculated on blood agar medium and cultured overnight at 37°C in a thermostatic incubator. A single clone was inoculated into 5 ml of trypticase soy broth (TSB) liquid medium. After secondary activation, cells were inoculated into TSB medium and cultured at 37°C with shaking at 220 rpm until the late stage of logarithmic growth.

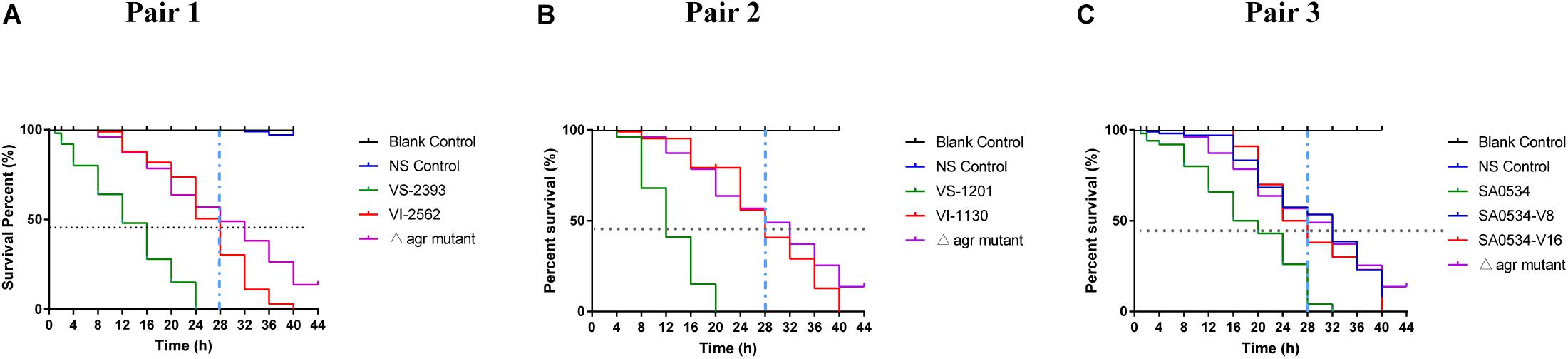

Activated VSSA and VISA strains were cultured to late logarithmic phase and then resuspended in NaCl solution at an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0. After weighing, large G. mellonella larvae were paired and grouped so that each group [VISA, VSSA, normal saline (control), and blank] was of equal quality, with an average of about 250 mg larvae per group. The concentration of bacteria in the solution injected into larvae of the VISA and VSSA groups was 1.0 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU)/100 μl; the injection site was between the second and third gastropods. Repeated injections at the same site were avoided. The treated larvae were placed in a clean, sterile plastic Petri dish in a 37°C incubator. All 4 groups were grown in the same environment. The number of dead larvae was recorded for 40 h to calculate survival rate.

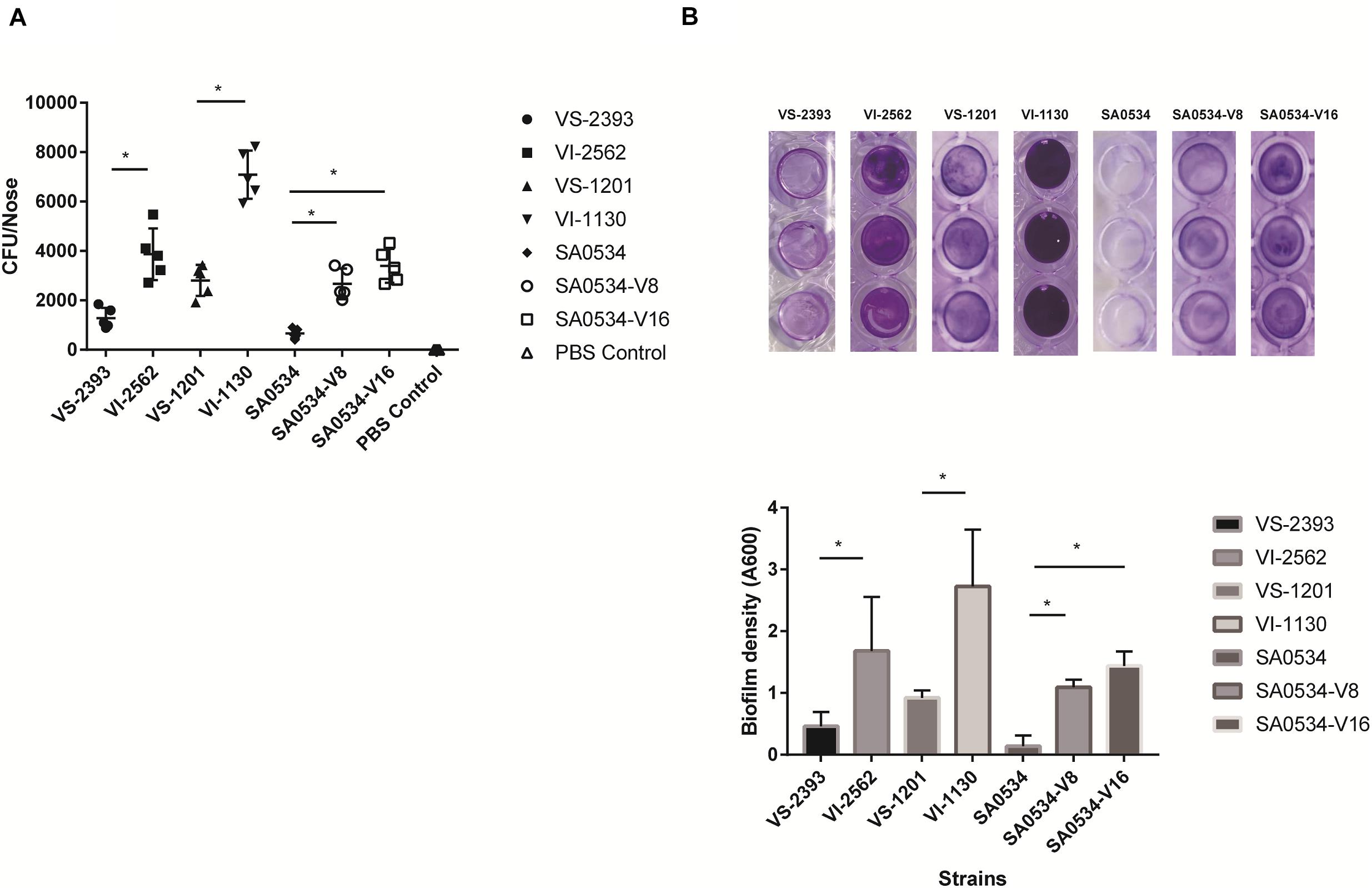

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 20 μl) containing 1 × 108 bacterial cells was introduced as a drop into the nasal cavity of mice. After 3 days, the mice were euthanized and the nose was dissected and homogenized. Total S. aureus count was determined by plating 200 μl diluted nose tissue suspension onto TS agar.

S. aureus strains were grown in a 96-well microplate in TSB containing 0.5% glucose at 37°C for 24 h. After 3 washes with PBS, the biofilm was fixed with 95% methanol and stained with 0.5% crystal violet dye for 20 min.

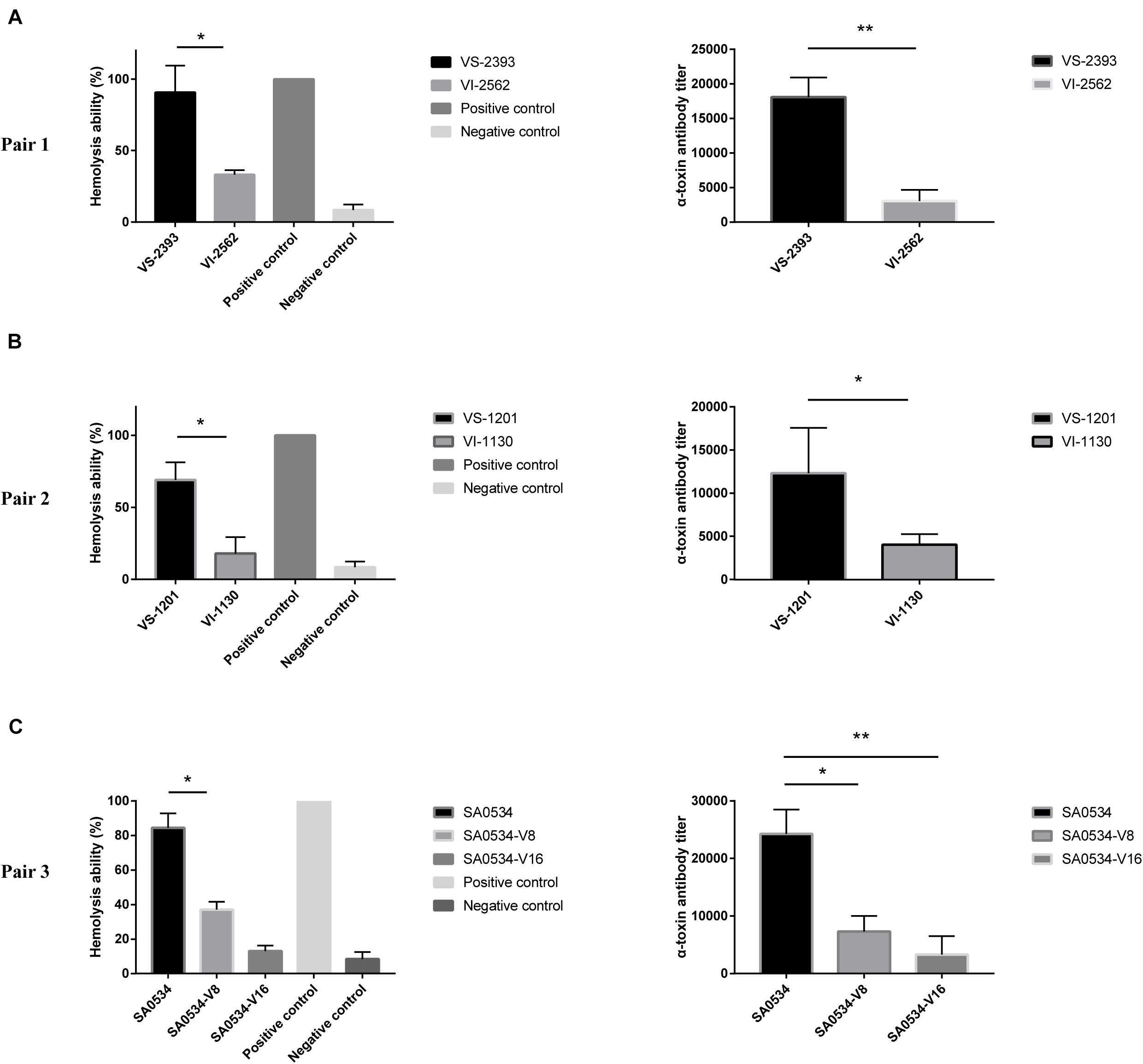

Hemolytic capacity was assessed as previously described (Jin et al., 2018). Briefly, S. aureus strains were grown in TSB at 37°C to the mid-exponential growth phase (6 h). After 6 h of incubation, the cells were centrifuged at 12,800 rpm and the supernatant was collected. Rabbit red blood cells (RRBCs) were washed 3 times with PBS (pH 7.2) and then mixed with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States) in fresh centrifuge tubes. An aliquot of supernatant was added to RRBCs, followed by incubation at 37°C for 3 h. Triton X-100 (1%) solution was used as a positive control and RRBCs resuspended in 1 × PBS served as a negative control.

Detection of α-toxin by ELISA was performed as previously described (Otto et al., 2013). Briefly, S. aureus strains were cultured overnight at 37°C. Samples were centrifuged at 12,800 rpm for 6 min. Monoclonal anti-α-hemolysin (Hla) antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) was used in sandwich-type ELISA in order to quantify the amount of α-toxin in the supernatant. Rabbit polyclonal anti-Hla antibody was used to detect the antigen–antibody complex. The linear equation y = ax + b was used to calculate the amount of α-toxin produced by each strain.

S. aureus strains were grown in TSB at 37°C to the mid-exponential growth phase (6 h). After 3 washes in sterile NaCl solution, cells were resuspended in sterile PBS (pH 7.2) at 107 CFU/ml. A 100–μl aliquot of bacterial solution was added to 10 ml heparinized blood and incubated at 37°C. To determine the survival rate of bacteria in whole blood, 100 μl of heparinized blood at different time points (0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, and 3 h) was plated on TS agar and colonies were counted.

Human neutrophils were obtained from the venous blood of healthy volunteers and mixed with heparin using a standard method (Kobayashi et al., 2002) in accordance with a protocol approved by the ethics committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, College of Medicine. Each volunteer provided informed consent before donating blood. Strains were grown for 6 h, and neutrophils were added at a 10:1 ratio (i.e., multiplicity of infection of 10), followed by incubation at 37°C for 3 h. PBS with 0.1% Triton-X-100 (100 μl) was used to as a positive control as it induces 100% lysis. Cell viability was determined using Cytotoxicity Detection KitPLUS (LDH) (Roche, Welwyn Garden City, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance of each well was measured to calculate the cytotoxicity to each strain after subtracting the background absorbance value according to the following formula:

S. aureus strains were grown at 37°C with shaking at 220 rpm. After 9 h, the cultures were centrifuged at 12,800 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a vial containing 1.5 ml of 0.1 mm zirconia silica beads. Total RNA was released by ultrasonic disruption using a Mini-Bead Beater (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK, United States). The RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions to purify RNA from each strain. RNase-free DNase I (Takara Bio, Otsu, and Japan) was used to eliminate contaminating genomic DNA and rRNA was removed prior to sequencing. RNA-seq of 3 biological replicates of SA0534 and SA0534-V16 was performed by Novogene Co. (Beijing, China) after samples were tested for purity. Differential gene expression was determined according to the following criteria: | log2 (fold change)| > 1, p < 0.05, and q < 0.05.

ELISA and hemolytic test results were analyzed with the chi-squared test. Survival rates of G. mellonella larvae infected with VSSA and VISA were determined by Kaplan–Meier analysis. Percent survival in human blood and cytotoxicity assay results were analyzed with the paired-samples t-test. Results of the quantitative analysis of nasal colonization and biofilm formation were evaluated with the t- and q-tests. Two-way factorial analysis of variance was used to assess differences in skin lesions caused by VISA and VSSA strains in mice. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism v7.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, and United States), and data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean.

All clinical S. aureus isolates were isolated in the operation room and hematology and urinary surgery wards of the hospital. VS-1201 and VI-1130 were identified as ST121-MSSA, whereas VS-2393 and VI-2562 were identified as ST239-MRSA-III-t030, which is the predominant HA–MRSA strain in China. A series of VISA strains were derived from SA0534. The isolates with MIC of vancomycin at 8 and 16 mg/l were named SA0534-V8 and SA0534-V16, respectively. We also identified SA0534 as a t030-carrying ST239 SCCmec III isolate.

We compared the infectivity of VISA and VSSA using a mouse abscess model. Skin lesions in mice caused by VISA and VSSA infection are shown in Figure 1A. In the pair 1 group, mice infected with VS-2393 had mid-sized abscesses 0.8–1.6 cm in diameter, whereas VI-2562 caused almost no abscess formation (Figure 1Ba). In the pair 2 group, mice infected with the VS-1201 strain had abscesses with a diameter 150 mm larger than those produced by VI-1130. On day 4 after injection, when the maximum range of skin lesion area was observed, the average abscess area in mice injected with the SA0534-V8 and SA0534-V16 strains was significantly smaller than that of mice infected with the SA0534 strain (Figure 1Bc). Moreover, there were no statistically significant differences between mice infected with the SA0534-V8 and SA0534-V16 strains. On day 9 after infection, the size of abscesses in mice infected with VSSA was significantly diminished. In contrast, abscesses were still observed in the VISA groups and there was no visible reduction in abscess area.

Figure 1. Results of mouse skin infection model experiments. (A) Is the photo of the comparison of abscess area of BALB/C-nude mice infected with VSSA and VISA strains. (B) Is line chart of the abscess area. Each strain injected six mice. The VS- indicates that this strain belongs to VSSA. The VI- indicates that the strain belongs to VISA. The SA0534-V8 and SA0534-V16 is VISA strains while SA0534 is a VSSA strain. Two-way analysis of variance was used to compare data for multiple groups.

The G. mellonella infection model was used in this study as a relatively rapid and potentially high-throughput in vivo assay compared to mammalian models that has been applied to investigations of S. aureus virulence (Peleg et al., 2009; Ramarao et al., 2012). Based on the results obtained with the mouse skin infection model, we compared survival rates of G. mellonella infected with VISA and VSSA strains to evaluate differences in pathogenicity. In each pair group, the percentage of surviving larvae was much higher following infection with VISA as compared to VSSA strains (p < 0.01 for each pair group) (Figure 2). The SA0534-V8 and SA0534-V16 strains had comparable effects on the survival of G. mellonella, which was similar to that of the negative (agr mutant) control (Figure 2C). The SA0534 strain was more virulent than the SA0534-V8 and SA0534-V16 strains (G. mellonella survival ≤ 52% at 12 h and ≤ 3% at 28 h). Meanwhile, the survival rates of VSSA strains VS-1130 and VI-2562 were higher than those of VISA strains.

Figure 2. Comparison of survival rates of VSSA and VISA infected with Galleria mellonella larvae. G. mellonella larvae were inoculated with 10 μl each pair at doses ranging from 1 × 104 and incubated at 37°C; the viability was assessed over 40 h. The VS- indicates that this strain belongs to VSSA. The VI- indicates that the strain belongs to VISA. The SA0534-V8 and SA0534-V16 is VISA strains while SA0534 is a VSSA strain. (A) Is the survival rates of VS-2393 and VI-2562 infected with G. mellonella larvae. (B) Is the survival rates of VS-1201 and VI-1130 infected with G. mellonella larvae. (C) Is the survival rates of SA0534, SA0534-V8, and SA0534-V16 infected with G. mellonella larvae.

S. aureus is an opportunistic pathogen that mainly colonizes healthy human nasal mucosa. The capacity of S. aureus for adhesion and colonization plays an important role in chronic infection (Rollin et al., 2017; Tan et al., 2019). We therefore compared nasal colonization by VISA and VSSA strains in BALB/c mice. All VISA strains showed a higher capacity for nasal colonization (Figure 3A) and biofilm formation (Figure 3B) than VSSA strains (both p < 0.05), reflecting a greater capacity for adhesion.

Figure 3. The comparison of nasal colonization and biofilm formation ability of VISA and VSSA strains. Values are means ± SD (three repeated different experiments). *P < 0.05. The VS- indicates that this strain belongs to VSSA. The VI- indicates that the strain belongs to VISA. The SA0534-V8 and SA0534-V16 is VISA strains while SA0534 is a VSSA strain. (A) Is the nasal colonization ability of VISA strains in mice (n = 5) compared with that of VISA strains. (B) Is the biofilm formation ability of VISA and VSSA strains.

Previous studies have shown that VISA has lower virulence than VSSA (Majcherczyk et al., 2008; Cameron et al., 2017). We compared the α-toxin activities of VISA and VSSA strains and found that in each pair group, α-toxin activity was lower in VISA than in VSSA (p < 0.05) (Figure 4). Furthermore, 74.26% (VS-1201) and 88.6% (VS-2393) of RRBCs were lysed by α-toxin, with 8.85- to 3.60-fold higher antibody titers than for VSSA strains (Figures 4A,B). The α-toxin activity of VISA strains (VI-1130 and VI-2562) led to significant reductions in the number of RRBCs (3.53 and 2.84 fold). As variability in the genetic background of VS-1201-SA1130 and VS-2393-VI-2562 could potentially contribute to the observed differences in virulence between VISA and VSSA, we further investigated the hemolytic capacity of a series of strains with induced vancomycin resistance (SA0534-V8 and SA0534-V16) in RRBCs. The α-toxin activities of strains SA0534-V8 (11.52%) and SA0534-V16 (18.46%) were lower than that of isolate SA0534 (79.26%), with a 6.53-fold lower antibody titer (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. α-toxin activity and production between VSSA and VISA strains. Spectrophotometer was used to calculated the absorbance (A600 nm) of each sample. The value of complete hemolysis group (positive control) was set as 100%. ELISA was used to semi-quantify the concentration of α-toxin. Supernatant without antibody was used as a negative control. Less than twice the value of the negative control was defined as the cut-off value. Values are means ± SD (three repeated different experiments). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. The VS- indicates that this strain belongs to VSSA. The VI- indicates that the strain belongs to VISA. The SA0534-V8 and SA0534-V16 is VISA strains while SA0534 is a VSSA strain. (A) Is the α-toxin activity and production between VS-2393 and VI-2562. (B) Is the α-toxin activity and production between VS-1201 and VI-1130. (C) Is the α-toxin activity and production among SA0534, SA0534-V8, and SA0534-V16.

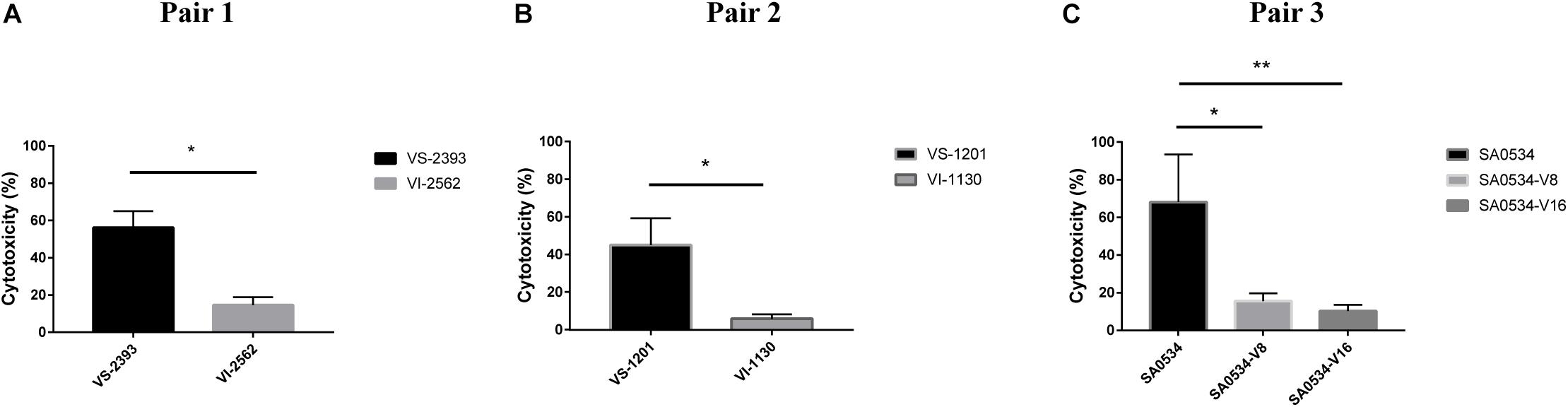

Human neutrophils are part of the innate immune system, which fights infection by pathogens. We evaluated differences in the pathogenicity of S. aureus by comparing the cytotoxicity of VISA and VSSA in vitro based on the level of reduced LDH released by damaged neutrophils after phagocytosis by S. aureus strains. The degree of cellular damage caused by VSSA (VS-1201 and VS-2393) was 3.86-fold higher than that caused by VISA strains (VS-1130 and VI-2562) (p < 0.05) (Figure 5A). We also evaluated the viability of the induced vancomycin resistance strain SA0534 and found that it caused more cellular damage than SA0534-V8 and SA0534-V16 (p < 0.05) (Figure 5B). These results indicate that VSSA is more toxic to human neutrophils than VISA.

Figure 5. Intracellular cytotoxicity of VSSA and VISA strains in human neutrophils. We performed the cytotoxicity assay, following controls. (1) Exp. value: the absorbance value of each experimental sample. (2) Low control: the absorbance value of culture medium background. (3) High control: the absorbance value of the positive control (maximum LDH release). Values are means ± SD (three repeated different experiments). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. The VS- indicates that this strain belongs to VSSA. The VI- indicates that the strain belongs to VISA. The SA0534-V8 and SA0534-V16 is VISA strains while SA0534 is a VSSA strain. (A) Is the comparison of cytotoxicity between VS-2393 and VI-2562. (B) Is the comparison of cytotoxicity between VS-1201 and VI-1130. (C) Is the comparison of cytotoxicity among SA0534, SA0534-V8, and SA0534-V16.

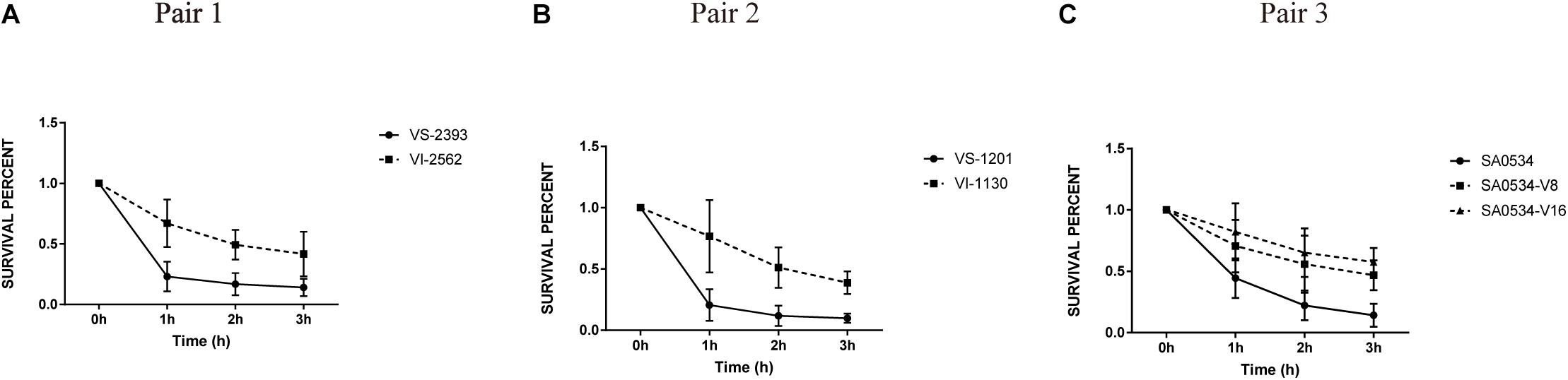

To further assess the virulence and pathogenicity of VISA, we compared the relative viabilities of VISA and VSSA strains in human blood. The percent survival of the VSSA strains VS-1201 and VS-2393 was 2.34- and 3.18-fold lower than that of the VISA strains VI-1130 and VI-2562, respectively, when cultured for 1 h (Figures 6A,B). After 3 h of culture, survival rates were lower for VSSA groups (14.28 and 9.85%) than for VSSA groups (41.73 and 33.77%); and the survival of isolates SA0534-V8 (46.82%) and SA0534-V16 (57.53%) was higher than that of isolate SA0534 (14.17%) (Figure 6C). Notably, the survival of VISA strains was inversely related to vancomycin MIC (p < 0.05). Thus, compared to VSSA, VISA has lower invasive capacity and cytotoxicity toward human neutrophils but shows enhanced ability to evade human immune surveillance. These findings are significant because clinical isolates of VISA often cause chronic and persistent infections.

Figure 6. The survival percentage in human blood between VISA strains and VSSA strains. The number of CFU was detected at the point at 0–3 h to calculate the rates of survival for three independent VSSA and VISA pairs exposed to human blood. Each test was repeated independently. Values are means ± SD (three repeated different experiments). The VS- indicates that this strain belongs to VSSA. The VI- indicates that the strain belongs to VISA. The SA0534-V8 and SA0534-V16 is VISA strains while SA0534 is a VSSA strain. (A) Is the comparison of survival percentage in human blood between VS-2393 and VI-2562. (B) Is the comparison of survival percentage in human blood between VS-1201 and VI-1130. (C) Is the comparison of survival percentage in human blood among SA0534, SA0534-V8, and SA0534-V16.

We identified 512 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the SA0534-V16 and SA0534 strains; of these, 261 were upregulated and 251 were downregulated in VISA as compared to VSSA strains (Supplementary Tables S1, S2). We selected 30 DEGs for validation by real-time quantitative PCR and found that their expression levels were consistent with the transcriptome profiles.

The gene lrgAB encoding a murein hydrolase regulator essential for cell lysis was downregulated 7.11 and 4.89-fold in VISA strains compared with VSSA, respectively; atlA, an autolysin protein-encoding gene was downregulated 8.13-fold relative to its level in the VSSA strain. AtlA induces platelet aggregation in whole blood (Binsker et al., 2018). Expression of hla encoding an S. aureus virulence factor was much lower in VISA as compared to VSSA. The agr genes (agrABCD) play an important role in regulating S. aureus virulence factors; we found here that agrA, agrB, and agrC were downregulated 6.40, 2.28, and 5.98-fold, respectively, in SA0534 relative to SA0534-V16.

The level of sbi encoding the immunoglobulin G-binding protein was decreased in the SA0534 strain compared to the SA0534-V16 strain (Table 2). Meanwhile, expression of capsular polysaccharide-associated genes (cap8B, cap8C, cap8D, cap8E, cap8F, and cap8M) was elevated in the VISA strain. These genes are part of a global transcriptional response that contributes to evasion of innate immune surveillance (Voyich et al., 2005).

Expression of Staphylococcal protein A (SpA) and clumping factor B (ClfB) was lower in the VISA strain than in the VSSA strain. Sbi promotes evasion of human neutrophil-mediated phagocytosis (Foster, 2005), while spA can bind to the Fc region of IgG to inhibit opsonophagocytosis, thus preventing activation of the classical complement pathway of the immune system and recognition by the neutrophil Fc receptor (Foster, 2005, 2009). ClfB is a major fibronectin-binding surface protein (Josefsson et al., 1998; Zhu et al., 2019) A previous study showed that the S. aureus clfB mutants were significantly attenuated in mouse sepsis models, arthritis models (McDevitt et al., 1997; O’Brien et al., 2002) and in a rat endocarditis model (Que et al., 2001). The Spl operon is unique to S. aureus, and comprises genes encoding 6 serine proteases on the νSaβ pathogenicity island. The spl operon has been implicated in localized lung damage, and spl mutants show altered expression of secreted and surface-associated proteins (Paharik et al., 2016). In this study, splA, splB, and splC levels were decreased 21.11, 9.51, and 13.83-fold, respectively. These data suggest that the production of extracellular secreted proteins encoded by hla and splABC and immune evasion proteins encoded by sbi, spa, and clfB is reduced in VISA compared to VSSA, while the opposite is true for fnbB and sdrCDE. fnbB is an important virulence gene that has been shown to contribute to S. aureus persistence on cardiac valves in experimental endocarditis (Que et al., 2005). Additionally, sdrCDE can induce staphylococcal biofilm formation and contributed to the ability of S. aureus to adhere to squamous cells (Corrigan et al., 2009; Barbu et al., 2014; Askarian et al., 2016).

Vancomycin is the first-line antibiotic for the treatment of MRSA infection. However, the excessive use of vancomycin has led to the emergence of VISA and hVISA strains worldwide. hVISA/VISA strains have a thicker cell wall compared to VSSA strains (Moreira et al., 1997; Boyle-Vavra et al., 2001), as well as lower autolytic activity (Dai et al., 2017) and altered cell wall-associated protein profile, growth rate, and Agr system function (Cui et al., 2003; Dai et al., 2017). Several studies have reported differences in pathogenicity between VISA and VSSA, with the former showing less hemolytic activity and producing less α-toxin, thus showing less cytotoxicity and virulence in an animal model (Cameron et al., 2017). VISA is associated with persistent and chronic infections such as bacteremia rather than acute clinical instability or lethal sepsis (Hegde et al., 2010). This suggests that although VISA is less virulent than VSSA, it can cause persistent infection.

The G. mellonella infection model has been widely used to compare the virulence of VISA and VSSA (Peleg et al., 2009). We used this model to determine whether VISA strains cause more persistent infection than VSSA strains. The results revealed differences in the pathogenicity of VISA and VSSA, with the latter being more lethal to G. mellonella larvae. In a mouse model of skin and soft tissue infection with S. aureus, abscess size was smaller on day 4 in mice infected with VISA as compared to VSSA. Notably, abscess formation persisted in VISA-infected mice up to day 9. These findings demonstrate that in acute skin and soft tissue infections, the invasion capacity of VISA is much lower than that of VSSA; and in chronic and persistent infections, VISA elicits innate immune system activation to a lesser extent than VSSA. This may be explained by lower or altered agr expression in VISA, as inactivating mutations in the agr gene of S. aureus have been linked to poorer outcomes in infected patients (Smyth et al., 2012; Suligoy et al., 2018).

Biofilm formation plays an important role in persistent infection, antibiotic resistance, and immune evasion by S. aureus (Archer et al., 2011). A strong ability to colonize can promote progression to chronic infection. However, findings regarding VISA biofilms are controversial. Clinical VISA strains were found to have diminished capacity for biofilm formation compared to the parent VSSA strains (Sakoulas et al., 2002), but another study showed that VISA formed thicker biofilms than VSSA (Howden et al., 2006). We found here that VISA strains had greater capacity for biofilm formation than VSSA strains, and in vivo experiments in mice demonstrated that nasal colonization by the former was most likely related to their enhanced biofilms. This was supported by the upregulation of genes (sdrCDE, fnbB, and some cell-wall related genes) associated with adhesion and biofilm formation in VISA. Fibronectin binding protein B (FnbBp) is a large multidomain protein encoded by fnbB (Xiong et al., 2015), while SdrCDE protect bacteria from host immune mechanisms and the effects of antibiotics (Barbu et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2017; Pi et al., 2020).

α-Toxin is a major virulence factor that plays an important role in skin and soft tissue infections (Kennedy et al., 2010; Kobayashi et al., 2011). Previous studies have reported that Hla is involved in skin infection (Kennedy et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016). To determine whether VISA and VSSA have comparable ability to cause skin and soft tissue infection, we evaluated α-toxin production and found that it was lower in VISA isolates, which is consistent with our findings using the mouse skin and soft tissue infection model and with the decreased expression of hla and agr, as well as the earlier observation that Hla protein expression is lower in VISA than in VSSA strains (Cameron et al., 2017).

Compared to VSSA, we found that VISA strains were less invasive and cytotoxic to human neutrophils, in accordance with their lower virulence. However, in human blood, VISA strains had higher survival rates than VSSA strains. VISA is known to have a thicker cell wall (Cui et al., 2003; Howden et al., 2006; Katayama et al., 2009). Therefore, this is likely attributable to the fact that the thicker cell wall of VISA strains comprises more peptidoglycans that confer resistance to phagocytosis by human polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocytes, thereby increasing the intracellular survival of VISA.

We carried out an RNA-seq analysis to investigate the genetic basis for the lower pathogenicity of VISA and found that the expression of hla and agrA was decreased in VISA relative to VSSA. AgrA directly regulates the expression of RNAII and RNAIII from the P2 and P3 promoters, and upregulation of RNAIII is associated with increased production of virulence factors, including α-toxin (Hla), serine proteases (SplA-F), and lipase (Geh) (Dunman et al., 2001; Cheung et al., 2011). Additionally, changes in agr transcription have been reported in hVISA/VISA strains (McGuinness et al., 2017). Thus, the decrease in the α-toxin activity is likely the result of hla gene regulation by Agr, which can also explain the fewer skin lesions associated with VISA infection.

The dysregulation of agr in S. aureus in the progression from acute to persistent infection has been reported (Smyth et al., 2012; Painter et al., 2014; Suligoy et al., 2018). In a rat osteomyelitis model, the persistence of S. aureus in bone was associated with decreased expression of agr, although agr mutation reduced the capacity of S. aureus to induce acute inflammation (Suligoy et al., 2018). Moreover, most clinical cases of S. aureus bacteremia are caused by agr-dysfunctional S. aureus. In this study, the downregulation of agr in VISA strains may be a trade-off for reduced virulence under the stress of antibiotic treatment.

Transcriptional profiling also revealed lower expression of spa, sbi, hla, clfB, and atlA and higher levels of capsular polysaccharide genes in VISA as compared to VSSA. Protein A binds to the Fc region of IgG to trigger platelet aggregation (Hawiger et al., 1972), while AtlA (Binsker et al., 2018) and Sbi (Haupt et al., 2008) are critical for platelet activation, which leads to the release of platelet microbiocidal proteins (Yeaman and Bayer, 1999). Thus, the decreased expression of spa, atlA, and sbi in VISA may result in reduced platelet activation; additionally, the lower levels of spa and sbi may modulate immune system response and promote persistent infection.

Overproduction of staphylococcal type 8 capsular polysaccharide was shown to protect bacteria against opsonophagocytic damage by human PMN leukocytes in vitro and cause persistent and chronic infection in mice (Luong et al., 2002). This suggests that transcriptional changes in capsular polysaccharide genes are an adaptation that allows VISA to persist in the human body while evading immune surveillance mechanisms. Increased expression capsular polysaccharide genes can prevent ClfB-mediated binding of staphylococci to fibrinogen and platelets (Risley et al., 2007). Notably, in our study clfB expression was much lower in VISA strains than in VSSA strains.

A limitation of our study is that we did not address the precise contribution of individual genetic mutations to the observed difference in virulence between VISA and VSSA, although mutations in agr, sbi, spa, and cap among other genes have been reported in VISA strains (Howden et al., 2006., 2011; Gardete et al., 2012; Park et al., 2012; Passalacqua et al., 2012; Hattangady et al., 2015). However, we discussed the decreased expression of these genes in VISA in the context of clinical outcomes (e.g., reduced platelet activation and chronic infections). The full complement of pathways involved in the virulence of VISA and VSSA strains remains to be elucidated in future studies.

In conclusion, we found that the virulence of VISA strains is much lower than that of VSSA strains in acute infection, consistent with the previous studies. However, in chronic and persistent infections, VISA elicits a weaker innate immune response compared to VSSA; this is associated with changes in the expression of capsule polysaccharide genes as well as spA, clfB, and Sbi, as well as Agr dysfunction. VISA strains also formed thicker biofilms than VSSA strains, which can enhance colonization. Thus, VISA is less capable of causing acute infections than VSSA; however, once in the bloodstream, VISA can cause chronic infection through strong adhesion and immune evasion despite its relatively low pathogenicity. These results provide insight into the mechanisms of virulence in drug-resistant S. aureus and can potentially explain treatment failure in cases of HA-VISA infection (chronic infection) without an associated increase in mortality (low virulence).

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, College of Medicine. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The animal study was reviewed and approved by The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, College of Medicine.

YJ, XY, and WC designed of the work and analyzed and interpreted of data for the work. BZ and YJ drafted the work and revised it critically for important intellectual content. XY provided approval for publication of the content. XK and SZ participated in the experimental design and data analysis. XY agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2017YFC1600100), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2017YFC1200203), the Mega-projects of Science Research of China (Grant No. 2018ZX10733402-004), and the Mega-projects of Science Research of China (Grant No. 2018ZX10712001-005).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Yuanyuan Dai at The Affiliated Provincial Hospital of Anhui Medical University for providing SA0534, SA0534-V8 and SA0534-V16 strains.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.596942/full#supplementary-material

Archer, N. K., Mazaitis, M. J., Costerton, J. W., Leid, J. G., Powers, M. E., and Shirtliff, M. E. (2011). Staphylococcus aureus biofilms: properties, regulation, and roles in human disease. Virulence 2, 445–459. doi: 10.4161/viru.2.5.17724

Askarian, F., Ajayi, C., Hanssen, A. M., van Sorge, N. M., Pettersen, I., Diep, D. B., et al. (2016). The interaction between Staphylococcus aureus SdrD and desmoglein 1 is important for adhesion to host cells. Sci. Rep. 6:22134. doi: 10.1038/srep22134

Barbu, E. M., Mackenzie, C., Foster, T. J., and Hook, M. (2014). SdrC induces staphylococcal biofilm formation through a homophilic interaction. Mol. Microbiol. 94, 172–185. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12750

Binsker, U., Palankar, R., Wesche, J., Kohler, T. P., Prucha, J., Burchhardt, G., et al. (2018). Secreted immunomodulatory proteins of Staphylococcus aureus activate platelets and induce platelet aggregation. Thromb. Haemost. 118, 745–757. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1637735

Boyle-Vavra, S., Carey, R. B., and Daum, R. S. (2001). Development of vancomycin and lysostaphin resistance in a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48, 617–625. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.5.617

Cameron, D. R., Lin, Y. H., Trouillet-Assant, S., Tafani, V., Kostoulias, X., Mouhtouris, E., et al. (2017). Vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus isolates are attenuated for virulence when compared with susceptible progenitors. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 23, 767–773. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.03.027

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2002a). Staphylococcus aureus resistant to vancomycin–United States, 2002. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly Rep. 51, 565–567.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2002b). Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus–Pennsylvania, 2002. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly Rep. 51:902.

Chang, W., Ding, D., Zhang, S., Dai, Y., Pan, Q., Lu, H., et al. (2015). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus grown on vancomycin-supplemented screening agar displays enhanced biofilm formation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 7906–7910. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00568-15

Chen, Y., Yeh, A. J., Cheung, G. Y., Villaruz, A. E., Tan, V. Y., Joo, H. S., et al. (2015). Basis of virulence in a panton-valentine leukocidin-negative community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain. J. Infect. Dis. 211, 472–480. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu462

Cheung, G. Y., Wang, R., Khan, B. A., Sturdevant, D. E., and Otto, M. (2011). Role of the accessory gene regulator agr in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 79, 1927–1935. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00046-11

Corrigan, R. M., Miajlovic, H., and Foster, T. J. (2009). Surface proteins that promote adherence of Staphylococcus aureus to human desquamated nasal epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 9:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-22

Cui, L., Ma, X., Sato, K., Okuma, K., Tenover, F. C., Mamizuka, E. M., et al. (2003). Cell wall thickening is a common feature of vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 5–14. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.1.5-14.2003

Cui, L., Murakami, H., Kuwahara-Arai, K., Hanaki, H., and Hiramatsu, K. (2000). Contribution of a thickened cell wall and its glutamine nonamidated component to the vancomycin resistance expressed by Staphylococcus aureus Mu50. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44, 2276–2285. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.9.2276-2285.2000

Dai, Y., Chang, W., Zhao, C., Peng, J., Xu, L., Lu, H., et al. (2017). VraR binding to the promoter region of agr inhibits its function in vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) and heterogeneous VISA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61:e002740-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02740-16

Deresinski, S. (2005). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an evolutionary, epidemiologic, and therapeutic odyssey. Clin. Infect. Dis. 40, 562–573. doi: 10.1086/427701

Dunman, P. M., Murphy, E., Haney, S., Palacios, D., Tucker-Kellogg, G., Wu, S., et al. (2001). Transcription profiling-based identification of Staphylococcus aureus genes regulated by the agr and/or sarA loci. J. Bacteriol. 183, 7341–7353. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7341-7353.2001

Foster, T. J. (2005). Immune evasion by Staphylococci. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 948–958. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1289

Foster, T. J. (2009). Colonization and infection of the human host by staphylococci: adhesion, survival and immune evasion. Vet. Dermatol. 20, 456–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2009.00825.x

Gardete, S., Kim, C., Hartmann, B. M., Mwangi, M., Roux, C. M., Dunman, P. M., et al. (2012). Genetic pathway in acquisition and loss of vancomycin resistance in a methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strain of clonal type USA300. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002505. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002505

Hattangady, D. S., Singh, A. K., Muthaiyan, A., Jayaswal, R. K., Gustafson, J. E., Ulanov, A. V., et al. (2015). Genomic, transcriptomic and metabolomic studies of two well-characterized, laboratory-derived vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus Strains derived from the same parent strain. Antibiotics 4, 76–112. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics4010076

Haupt, K., Reuter, M., van den Elsen, J., Burman, J., Halbich, S., Richter, J., et al. (2008). The Staphylococcus aureus protein Sbi acts as a complement inhibitor and forms a tripartite complex with host complement factor H and C3b. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000250. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000250

Hawiger, J., Marney, S. R. Jr., Colley, D. G., and Des Prez, R. M. (1972). Complement-dependent platelet injury by staphylococcal protein A. J. Exp. Med. 136, 68–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.136.1.68

Hegde, S. S., Skinner, R., Lewis, S. R., Krause, K. M., Blais, J., and Benton, B. M. (2010). Activity of telavancin against heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (hVISA) in vitro and in an in vivo mouse model of bacteraemia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65, 725–728. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq028

Hiramatsu, K., Aritaka, N., Hanaki, H., Kawasaki, S., Hosoda, Y., Hori, S., et al. (1997). Dissemination in Japanese hospitals of strains of Staphylococcus aureus heterogeneously resistant to vancomycin. Lancet 350, 1670–1673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07324-8

Howden, B. P., Johnson, P. D., Ward, P. B., Stinear, T. P., and Davies, J. K. (2006). Isolates with low-level vancomycin resistance associated with persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 3039–3047. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00422-06

Howden, B. P., McEvoy, C. R., Allen, D. L., Chua, K., Gao, W., Harrison, P. F., et al. (2011). Evolution of multidrug resistance during Staphylococcus aureus infection involves mutation of the essential two component regulator WalK. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002359. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002359

Jin, Y., Li, M., Shang, Y., Liu, L., Shen, X., Lv, Z., et al. (2018). Sub-inhibitory concentrations of mupirocin strongly inhibit Alpha-toxin production in high-level mupirocin-resistant MRSA by down-regulating agr, saeRS, and sar. Front. Microbiol. 9:993. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00993

Josefsson, E., McCrea, K. W., Ni Eidhin, D., O’Connell, D., Cox, J., Hook, M., et al. (1998). Three new members of the serine-aspartate repeat protein multigene family of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology 144(Pt 12), 3387–3395. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-12-3387

Katayama, Y., Murakami-Kuroda, H., Cui, L., and Hiramatsu, K. (2009). Selection of heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus by imipenem. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 3190–3196. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00834-08

Kennedy, A. D., Bubeck Wardenburg, J., Gardner, D. J., Long, D., Whitney, A. R., Braughton, K. R., et al. (2010). Targeting of alpha-hemolysin by active or passive immunization decreases severity of USA300 skin infection in a mouse model. J. Infect. Dis. 202, 1050–1058. doi: 10.1086/656043

Kobayashi, S. D., Malachowa, N., Whitney, A. R., Braughton, K. R., Gardner, D. J., Long, D., et al. (2011). Comparative analysis of USA300 virulence determinants in a rabbit model of skin and soft tissue infection. J. Infect. Dis. 204, 937–941. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir441

Kobayashi, S. D., Voyich, J. M., Buhl, C. L., Stahl, R. M., and DeLeo, F. R. (2002). Global changes in gene expression by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes during receptor-mediated phagocytosis: cell fate is regulated at the level of gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 6901–6906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092148299

Leclercq, R., Derlot, E., Duval, J., and Courvalin, P. (1988). Plasmid-mediated resistance to vancomycin and teicoplanin in Enterococcus faecium. N. Engl. J. Med. 319, 157–161. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807213190307

Li, M., Cheung, G. Y., Hu, J., Wang, D., Joo, H. S., Deleo, F. R., et al. (2010). Comparative analysis of virulence and toxin expression of global community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Infect. Dis. 202, 1866–1876. doi: 10.1086/657419

Li, M., Dai, Y., Zhu, Y., Fu, C. L., Tan, V. Y., Wang, Y., et al. (2016). Virulence determinants associated with the Asian community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineage ST59. Sci. Rep. 6:27899. doi: 10.1038/srep27899

Luong, T., Sau, S., Gomez, M., Lee, J. C., and Lee, C. Y. (2002). Regulation of Staphylococcus aureus capsular polysaccharide expression by agr and sar A. Infect. Immun. 70, 444–450. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.444-450.2002

Majcherczyk, P. A., Barblan, J. L., Moreillon, P., and Entenza, J. M. (2008). Development of glycopeptide-intermediate resistance by Staphylococcus aureus leads to attenuated infectivity in a rat model of endocarditis. Microb. Pathog. 45, 408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2008.09.003

McDevitt, D., Nanavaty, T., House-Pompeo, K., Bell, E., Turner, N., McIntire, L., et al. (1997). Characterization of the interaction between the Staphylococcus aureus clumping factor (ClfA) and fibrinogen. Eur. J. Biochem. 247, 416–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00416.x

McGuinness, W. A., Malachowa, N., and DeLeo, F. R. (2017). Vancomycin Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Yale J. Biol. Med. 90, 269–281.

Moreira, B., Boyle-Vavra, S., deJonge, B. L., and Daum, R. S. (1997). Increased production of penicillin-binding protein 2, increased detection of other penicillin-binding proteins, and decreased coagulase activity associated with glycopeptide resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41, 1788–1793. doi: 10.1128/AAC.41.8.1788

Noble, W. C., Virani, Z., and Cree, R. G. (1992). Co-transfer of vancomycin and other resistance genes from Enterococcus faecalis NCTC 12201 to Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 72, 195–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05089.x

O’Brien, L. M., Walsh, E. J., Massey, R. C., Peacock, S. J., and Foster, T. J. (2002). Staphylococcus aureus clumping factor B (ClfB) promotes adherence to human type I cytokeratin 10: implications for nasal colonization. Cell Microbiol. 4, 759–770. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00231.x

Oliveira, D. C., Tomasz, A., and de Lencastre, H. (2002). Secrets of success of a human pathogen: molecular evolution of pandemic clones of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2, 180–189. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00227-X

Otto, M. P., Martin, E., Badiou, C., Lebrun, S., Bes, M., Vandenesch, F., et al. (2013). Effects of subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics on virulence factor expression by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68, 1524–1532. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt073

Paharik, A. E., Salgado-Pabon, W., Meyerholz, D. K., White, M. J., Schlievert, P. M., and Horswill, A. R. (2016). The Spl serine proteases modulate Staphylococcus aureus protein production and virulence in a rabbit model of pneumonia. mSphere 1:e00208-16. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00208-16

Painter, K. L., Krishna, A., Wigneshweraraj, S., and Edwards, A. M. (2014). What role does the quorum-sensing accessory gene regulator system play during Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia? Trends Microbiol. 22, 676–685. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.09.002

Park, C., Shin, N. Y., Byun, J. H., Shin, H. H., Kwon, E. Y., Choi, S. M., et al. (2012). Downregulation of RNAIII in vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus strains regardless of the presence of agr mutation. J. Med. Microbiol. 61(Pt 3), 345–352. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.035204-0

Passalacqua, K. D., Satola, S. W., Crispell, E. K., and Read, T. D. (2012). A mutation in the PP2C phosphatase gene in a Staphylococcus aureus USA300 clinical isolate with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin and daptomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 5212–5223. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05770-11

Peleg, A. Y., Monga, D., Pillai, S., Mylonakis, E., Moellering, R. C. Jr., and Eliopoulos, G. M. (2009). Reduced susceptibility to vancomycin influences pathogenicity in Staphylococcus aureus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 199, 532–536. doi: 10.1086/596511

Pi, Y., Chen, W., and Ji, Q. (2020). Structural basis of Staphylococcus aureus surface protein Sdr. Biochem. C 59, 1465–1469. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00124

Que, Y. A., Francois, P., Haefliger, J. A., Entenza, J. M., Vaudaux, P., and Moreillon, P. (2001). Reassessing the role of Staphylococcus aureus clumping factor and fibronectin-binding protein by expression in Lactococcus lactis. Infect. Immun. 69, 6296–6302. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6296-6302.2001

Que, Y. A., Haefliger, J. A., Piroth, L., Francois, P., Widmer, E., Entenza, J. M., et al. (2005). Fibrinogen and fibronectin binding cooperate for valve infection and invasion in Staphylococcus aureus experimental Endocarditis. J. Exp. Med. 201, 1627–1635. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050125

Ramarao, N., Nielsen-Leroux, C., and Lereclus, D. (2012). The insect Galleria mellonella as a powerful infection model to investigate bacterial pathogenesis. J. Vis. Exp. 70:e4392. doi: 10.3791/4392

Risley, A. L., Loughman, A., Cywes-Bentley, C., Foster, T. J., and Lee, J. C. (2007). Capsular polysaccharide masks clumping factor A-mediated adherence of Staphylococcus aureus to fibrinogen and platelets. J. Infect. Dis. 196, 919–927. doi: 10.1086/520932

Rollin, G., Tan, X., Tros, F., Dupuis, M., Nassif, X., Charbit, A., et al. (2017). Intracellular survival of Staphylococcus aureus in endothelial cells: a matter of growth or persistence. Front. Microbiol. 8:1354. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01354

Sakoulas, G., Eliopoulos, G. M., Moellering, R. C. Jr., Wennersten, C., Venkataraman, L., Novick, R. P., et al. (2002). Accessory gene regulator (agr) locus in geographically diverse Staphylococcus aureus isolates with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 1492–1502. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.5.1492-1502.2002

Smyth, D. S., Kafer, J. M., Wasserman, G. A., Velickovic, L., Mathema, B., Holzman, R. S., et al. (2012). Nasal carriage as a source of agr-defective Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J. Infect. Dis. 206, 1168–1177. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis483

Suligoy, C. M., Lattar, S. M., Noto Llana, M., Gonzalez, C. D., Alvarez, L. P., Robinson, D. A., et al. (2018). Mutation of Agr is associated with the adaptation of Staphylococcus aureus to the Host during chronic osteomyelitis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 8:18. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00018

Tan, X., Coureuil, M., Ramond, E., Euphrasie, D., Dupuis, M., Tros, F., et al. (2019). Chronic Staphylococcus aureus lung infection correlates with proteogenomic and metabolic adaptations leading to an increased intracellular persistence. Clin. Infect. Dis. 69, 1937–1945. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz106

Voyich, J. M., Braughton, K. R., Sturdevant, D. E., Whitney, A. R., Said-Salim, B., Porcella, S. F., et al. (2005). Insights into mechanisms used by Staphylococcus aureus to avoid destruction by human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 175, 3907–3919. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3907

Walsh, C. (1999). Deconstructing vancomycin. Science 284, 442–443. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5413.442

Xiong, Y. Q., Sharma-Kuinkel, B. K., Casillas-Ituarte, N. N., Fowler, V. G. Jr., Rude, T., DiBartola, A. C., et al. (2015). Endovascular infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus are linked to clonal complex-specific alterations in binding and invasion domains of fibronectin-binding protein A as well as the occurrence of fnb. Infect. B Immun. 83, 4772–4780. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01074-15

Yeaman, M. R., and Bayer, A. S. (1999). Antimicrobial peptides from platelets. Drug Resist. Updat. 2, 116–126. doi: 10.1054/drup.1999.0069

Zhang, Y., Wu, M., Hang, T., Wang, C., Yang, Y., Pan, W., et al. (2017). Staphylococcus aureus SdrE captures complement factor H’s C-terminus via a novel ‘close, dock, lock and latch’ mechanism for complement evasion. Biochem. J. 474, 1619–1631. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20170085

Keywords: vancomycin-intermediate staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin-sensitive staphylococcus aureus, virulence, persistent infection, immune evasion, quorum sensing accessory gene regulator system agr

Citation: Jin Y, Yu X, Zhang S, Kong X, Chen W, Luo Q, Zheng B and Xiao Y (2020) Comparative Analysis of Virulence and Toxin Expression of Vancomycin-Intermediate and Vancomycin-Sensitive Staphylococcus aureus Strains. Front. Microbiol. 11:596942. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.596942

Received: 20 August 2020; Accepted: 12 October 2020;

Published: 30 October 2020.

Edited by:

Jørgen Johannes Leisner, University of Copenhagen, DenmarkCopyright © 2020 Jin, Yu, Zhang, Kong, Chen, Luo, Zheng and Xiao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Beiwen Zheng, emhlbmdid0B6anUuZWR1LmNu; Yonghong Xiao, eGlhb3lvbmdob25nQHpqdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.