- 1Institute of Microbiology, School of Ecology and Nature Conservation, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China

- 2Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Tree Breeding by Molecular Design, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China

- 3Permanent Research Base of National Forestry and Grassland Administration, Jiangsu Vocational College of Agriculture and Forestry, Zhenjiang, China

- 4Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Helsinki, Finland

- 5University of Lorraine, INRAE, Tree-Microbes Interaction Department, Champenoux, France

Heterobasidion species are amongst the most intensively studied polypores because several species are aggressive white rot pathogens of managed coniferous forests mainly in Europe and North America. In the present study, both morphological and multilocus phylogenetic analyses were carried out on Heterobasidion samples from Asia, Oceania, Europe and North America. Three new taxa were found, i.e., H. armandii, H. subinsulare, and H. subparviporum are from Asia and are described as new species. H. ecrustosum is treated as a synonym of H. insulare. So far, six taxa in the H. annosum species complex are recognized. Heterobasidion abietinum, H. annosum, and H. parviporum occur in Europe, H. irregulare, and H. occidentale in North America, and H. subparviporum in East Asia. The North American H. irregulare was introduced to Italy during the Second World War. Species in the H. annosum complex are pathogens of coniferous trees, except H. subparviporum that seems to be a saprotroph. Ten species are found in the H. insulare species complex, all of them are saprotrophs. The pathogenic species are distributed in Europe and North America; the Asian countries should consider the European and North American species as entry plant quarantine fungi. Parallelly, European countries should consider the American H. occidentale and H. irregulare as entry plant quarantine fungi although the latter species is already in Italy, while North America should treat H. abietinum, H. annosum s.s., and H. parviporum as entry plant quarantine fungi. Eight Heterobasidion species found in the Himalayas suggest that the ancestral Heterobasidion species may have occurred in Asia.

Introduction

The polypore genus Heterobasidion Bref., which belongs to the family Bondarzewiaceae, is one of the most intensively studied basidiomycetous genera because some species of Heterobasidion are aggressive pathogens of managed coniferous forests in Europe and North America (Woodward et al., 1998). Two morphological taxa, H. annosum (Fr.) Bref. and H. insulare (Murrill) Ryvarden, had generally been accepted in Heterobasidion (Murrill, 1908; Gilbertson and Ryvarden, 1986; Ryvarden and Gilbertson, 1993; Núñez and Ryvarden, 2001). However, mating studies have revealed that both H. annosum and H. insulare are in fact species complexes (Korhonen, 1978; Dai and Korhonen, 1999; Dai et al., 2002, 2003).

Three species, Heterobasidion abietinum Niemelä and Korhonen (Eur F-group), H. annosum (Fr.) Bref. sensu stricto (Eur P-group) and H. parviporum Niemelä and Korhonen (Eur S-group), have been recognized in Europe (Niemelä and Korhonen, 1998), and two species, H. irregulare Garbel. and Otrosina (NAm P-group) and H. occidentale Otrosina and Garbel. (NAm S-group), were described from North America (Otrosina and Garbelotto, 2010). Based on mating studies, the East Asian taxon in the H. annosum species complex was considered as H. parviporum (Dai and Korhonen, 1999, 2003; Dai et al., 2006; Dai, 2012; Chen et al., 2015). Similarly, investigations based on mating tests, morphological characteristics and molecular analyses revealed several species also within the Asian H. insulare complex: H. linzhiense Y. C. Dai and Korhonen (Dai et al., 2007), H. australe Y. C. Dai and Korhonen (2009), H. ecrustosum Tokuda, T. Hatt. and Y. C. Dai, H. orientale Tokuda, T. Hatt. and Y. C. Dai (Tokuda et al., 2009), H. amyloideum Y. C. Dai, Jia J. Chen and Korhonen, H. tibeticum Y. C. Dai, Jia J. Chen and Korhonen (Chen et al., 2014) and H. amyloideopsis Saba, C. L. Zhao, Khalid and Pfister (Zhao et al., 2017). In addition, H. araucariae P. K. Buchanan from Australia and adjacent regions (Buchanan, 1988) was confirmed to be a member of the H. insulare species complex (Chen et al., 2015).

Earlier phylogenetic analyses on the H. annosum complex used sequences of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and intergenic spacer (IGS) regions of the nuclear genes, and manganese peroxidase genes, and laccase genes (Maijala et al., 2003; Asiegbu et al., 2004). Later, several attempts were made to resolve the taxonomy of the H. annosum complex or H. insulare complex using multilocus phylogenetic approaches (Johannesson and Stenlid, 2003; Ota et al., 2006; Linzer et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2014). Recently, five species in the H. annosum species complex and eight species in H. insulare species complex were also recognized and confirmed by multilocus phylogenetic approaches, and divided into three groups based on five nuclear genes and two mitochondrial genes, i.e., ITS, the large nuclear ribosomal RNA subunit (nrLSU), the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB1), the second subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB2), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), mitochondrial ATP synthase subunit 6 (ATP6), and mitochondrial small subunit rDNA (mtSSU) (Chen et al., 2015).

Several hypotheses on the evolutionary scenarios of the Heterobasidion have been put forward (Otrosina et al., 1993; Ota et al., 2006; Linzer et al., 2008). Dalman et al. (2010) proposed that the H. annosum complex originated in Laurasia, H. annosum s.s./H. irregulare arose in Eurasia, and H. parviporum/H. abietinum/H. occidentale, which occurred in eastern Asia or western North America, emerged between 45 and 60 Ma in the Palaearctic; this conclusion was based on non-coding regions of elongation factor 1-α (EFA), glutathione-S-transferase (GST1), GAPDH, and transcription factor (TF). Recently, based on more species and samples of Heterobasidion and the fossil record, molecular dating suggested that ancestral Heterobasidion species originated in Eurasia occurred mainly during the Early Miocene (Chen et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2017).

Based on a larger set of Heterobasidion samples from Asia, Oceania, Europe and North America, and using combined RPB1 and RPB2 sequence dataset, a further phylogenetic investigation on the genus is carried out. Four new taxa are detected, and three of them are described and illustrated in the present paper. Moreover, most relevant morphological characteristics of different species of Heterobasidion are compared.

Materials and Methods

Morphological Studies

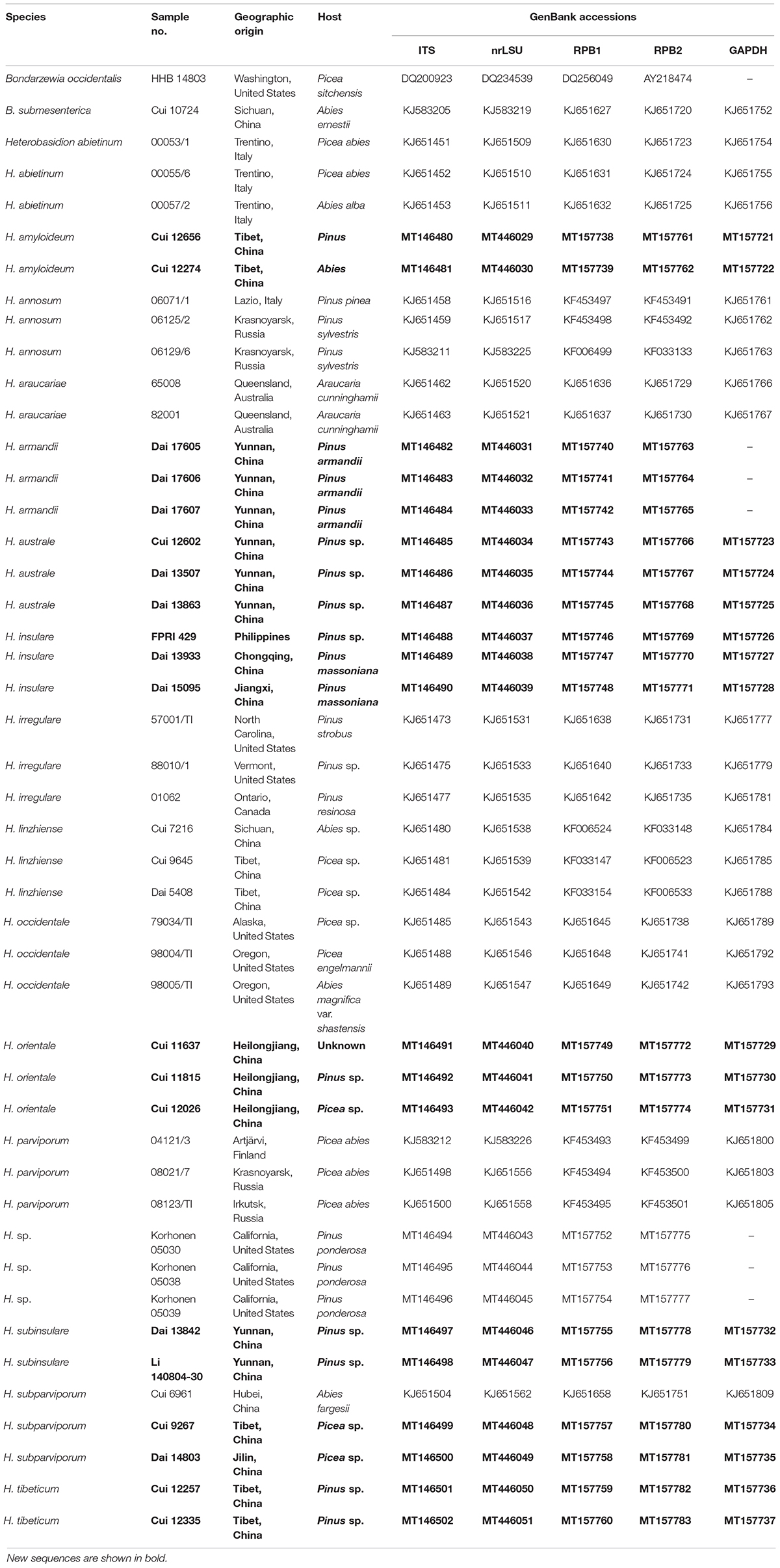

The studied specimens and cultures (Table 1) are deposited at the herbaria of Institute of Microbiology of the Beijing Forestry University (BJFC, Beijing, China), Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke, Helsinki, Finland), U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station (CFMR, Madison, WI, United States), private herbarium of J. Vlasák (JV, České Budějovice, Czechia), and Landcare Research, New Zealand (PDD, Lincoln, New Zealand). Ecology and some macromorphological characters were based on field notes. Anatomy was studied, and measurements and drawings were made from slide preparations stained with Cotton Blue. Drawings were made with the aid of a drawing tube. In presenting the variation in the size of the spores, the 5% of the measurements at each end of the range are shown in parentheses. Basidiospore spine lengths are not included in the measurements. The following abbreviations are used: IKI = Melzer’s reagent, IKI− = both non-amyloid and non-dextrinoid, IKI+ = amyloid, KOH = 5% potassium hydroxide, CB = Cotton Blue, CB+ = cyanophilous, L = mean spore length (arithmetic average of all spores), W = mean spore width (arithmetic average of all spores), Q = variation in the L/W ratios between the specimens studied, n = number of spores measured from given number of specimens. Color terms are from Petersen (1996).

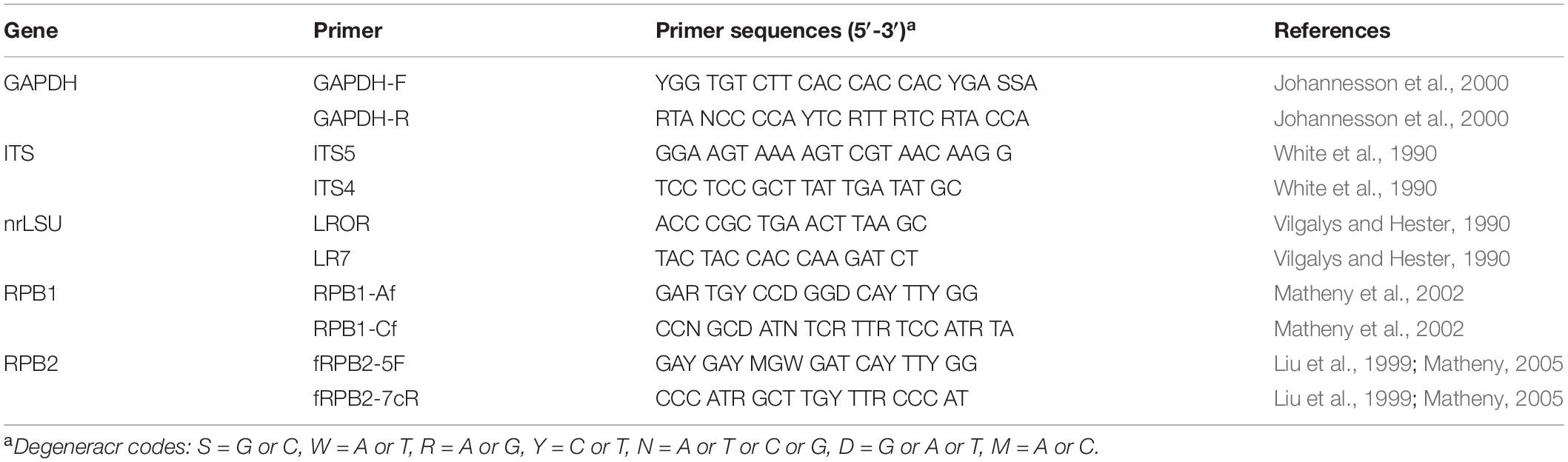

DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification and Sequencing

The Rapid Plant Genome kit based on acetyl trimethylammonium bromide extraction (Aidlab Biotechnologies Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was used to extract genomic DNA from dried fungal specimens and cultures, according to the manufacturer’s instructions with some modifications (Chen et al., 2014). The PCR primers for all genes are listed in Table 2. The PCR procedure for nrLSU was as follows: initial denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1.5 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The following PCR protocol for GAPDH, and ITS was used: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 40 s, (50°C for GAPDH, 54°C for ITS), 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR procedure for RPB1 and RPB2 followed Justo and Hibbett (2011) with slight modifications: initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min, followed by 10 cycles at 94°C for 40 s, 60°C for 40 s, 72°C for 2 min, then followed by 37 cycles at 94°C for 45 s, 55°C for 1.5 min and 72°C for 2 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were purified with a Gel Extraction and PCR Purification Combo Kit (Spin-column) in Beijing Genomics Institute, Beijing, China. The purified products were then sequenced on an ABI-3730-XL DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) using the same primers as in the original PCR amplifications. All newly generated sequences were deposited at GenBank1 and listed in Table 1.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Bondarzewia occidentalis Jia J. Chen, B. K. Cui and Y. C. Dai and B. submesenterica Jia J. Chen, B. K. Cui and Y. C. Dai were used as outgroups (Chen et al., 2015). Sequences were aligned with BioEdit (Hall, 1999) and ClustalX (Thompson et al., 1997). Sequence alignments were deposited at TreeBase2 (submission ID 25908).

Maximum parsimony (MP) analysis was applied to single-locus genealogies for ITS, nrLSU, RPB1, PPB2, and GAPDH, and combination datasets that contained the RPB1-RPB2 sequences. The tree construction procedure was performed in PAUP∗ version 4.0b10 (Swofford, 2002). All characters were equally weighted, and gaps were treated as missing data. Trees were inferred using the heuristic search option with TBR branch swapping and 1000 random sequence additions. Max-trees were set to 5000, branches of zero length were collapsed, and all parsimonious trees were saved. Clade robustness was assessed using a bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates (Felsenstein, 1985). Descriptive tree statistics tree length (TL), consistency index (CI), retention index (RI), rescaled consistency index (RCI), and homoplasy index (HI), were calculated for each maximum parsimonious tree generated. Phylogenetic trees were visualized using Treeview (Page, 1996).

MrMODELTEST2.3 (Nylander, 2004) was used to determine the best-fit evolution model for the combined dataset for Bayesian inference (BI). The BI was calculated with MrBayes 3.1.2 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003) with a general time reversible model of DNA substitution and an invgamma distribution rate variation across sites. Eight Markov chains were run from random starting tree for 1 M generations of RPB1 and RPB2 dataset, and sampled every 100 generations. The burn-in was set to discard the first 25% of the trees. A majority rule consensus tree of all remaining trees was calculated. Branches that received bootstrap values for MP and Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPP) greater than or equal to 75% (MP) and 0.95 (BPP) were considered as significantly supported.

To determine if the datasets were significantly conflicted, the partition homogeneity test option in PAUP 4.0b was used between the loci in all possible pairwise combinations using 1000 replicates and the heuristic general search option. This test randomly shuffles phylogenetically informative sites between two paired loci: if the datasets are compatible, shuffling sites between the loci should not produce summed tree lengths that are significantly greater than those produced by the observed data (Farris et al., 1994; Huelsenbeck et al., 1996).

Results

Molecular Phylogeny

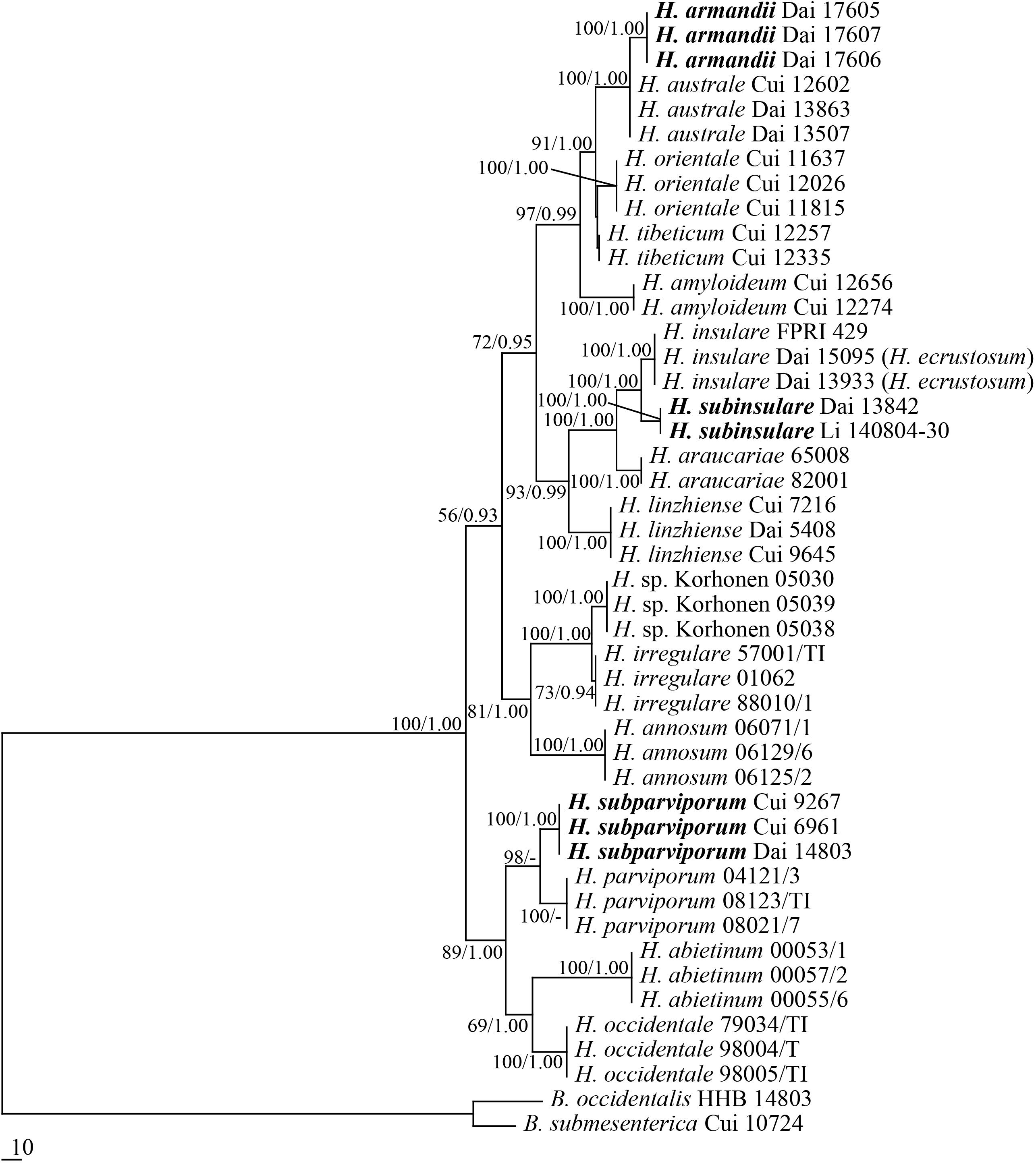

All targeted DNA loci were successfully amplified and sequenced from our Heterobasidion samples and the outgroup species. Partition homogeneity test showed no conflicts for the RPB1 and RPB2 combined loci (P = 0.019, P ≥ 0.01). Therefore, the amino acid sequences from RPB1 and RPB2 were combined into a single sequence set. The combined dataset included sequences from 46 specimens representing 18 species. The dataset had an aligned length of 2505 characters, of which 1796 characters were constant, 671 were variable and parsimony-uninformative, and 38 were parsimony-informative. The maximum parsimony analysis yielded four equally parsimonious tree (TL = 1033, CI = 0.789, HI = 0.925, RI = 0.730, RC = 0.211). The best model for the combined RPB1 + RPB2 estimated and applied in the Bayesian analysis: GTR + I + G, lset nst = 6, rates = invgamma; prset statefreqpr = dirichlet (1,1,1,1). The Bayesian analysis resulted in a topology similar to the MP analysis, with an average standard deviation of split frequencies = 0.006737, and only the MP tree was provided. Both bootstrap values (>50%) and BPPs (≥0.90) were shown at the nodes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Phylogeny of Heterobasidion and related species generated by Maximum Parsimony based on combined RPB1 + RPB2 sequences. Parsimony bootstrap values (before the slash markers) higher than 50% and Bayesian posterior probabilities (after the slash markers) more than 0.95 were indicated along branches.

Three new species, Heterobasidion armandii, H. subinsulare, and H. subparviporum formed a well-supported phylogenetic lineages, respectively (100% MP, and 1 BPPs), and phylogenetically distinct from other known species of Heterobasidion.

According to the present phylogenetic analyses, Heterobasidion spp. consists of three lineages: (1) the lineage associated to pines, firs and spruces (H. amyloideopsis, H. amyloideum, H. araucariae, H. armandii, H. australe, H. insulare, H. linzhiense, H. orientale, H. subinsulare, and H. tibeticum); (2) lineage mainly associated to pines (H. annosum s.s., H. sp. and H. irregulare); and (3) the lineage associated to firs and spruces (H. abietinum, H. occidentale, H. parviporum, and H. subparviporum).

Taxonomy

Heterobasidion armandii Y. C. Dai, Jia J. Chen and Yuan Yuan, sp. nov. Figures 2, 3

MycoBank MB 834572.

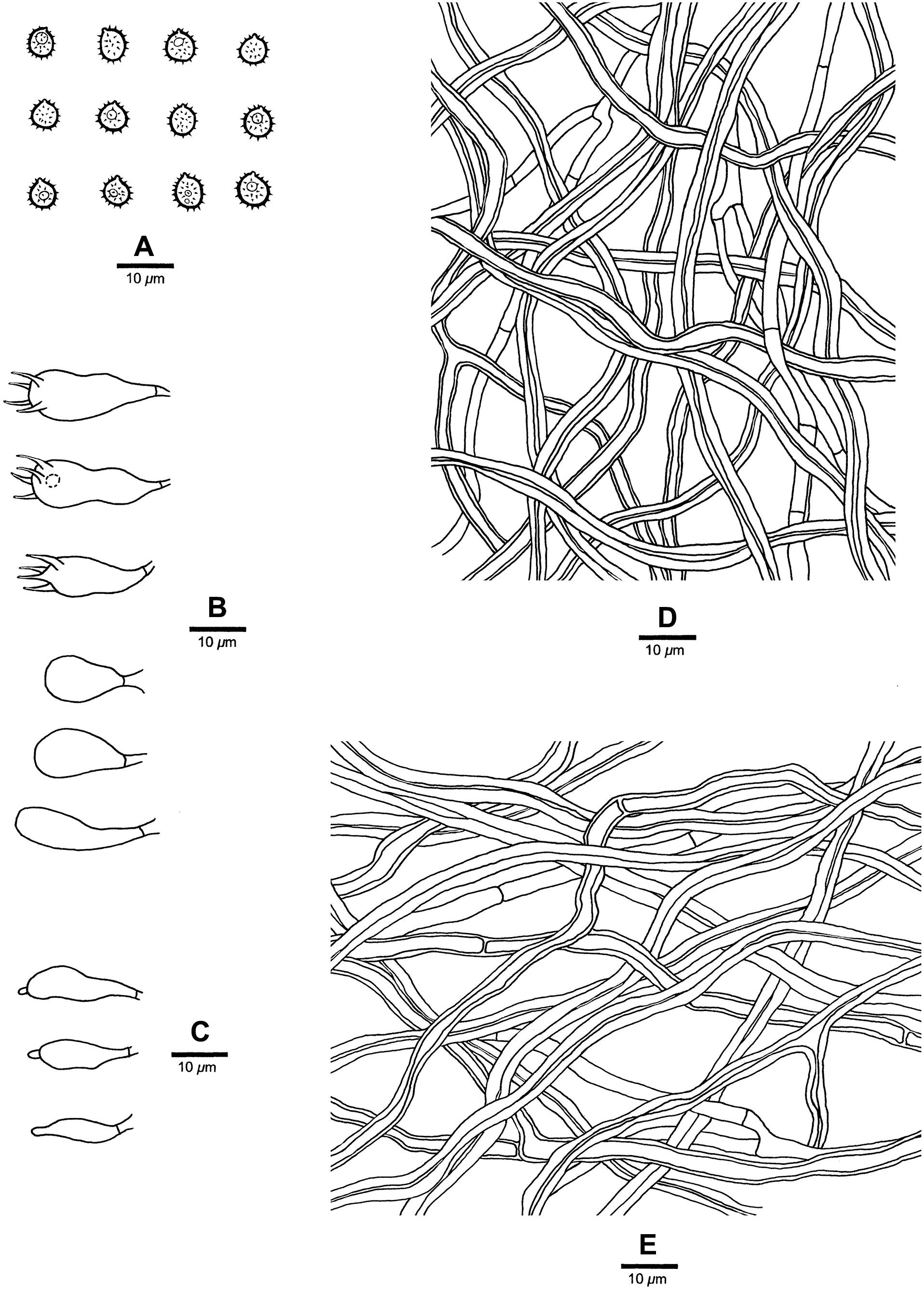

Figure 3. Microscopic structures of Heterobasidion armandii (drawn from the holotype). (A) Basidiospores; (B) Basidia and basidioles; (C) Cystidioles; (D) Hyphae from trama; (E) Hyphae from context.

Type

China, Yunnan Province, Xiping County, Mopanshan Forest Park, alt.135 m, on stump of Pinus armandii, June 15, 2017, YC Dai 17605 (BJFC025137, holotype).

Diagnosis

Differs from other Heterobasidion species by its contextual skeletal hyphae are positive in Melzer’s reagent, absence of cystidia, presence of cystidioles, and subglobose to broadly ellipsoid basidiospores measuring 4.9−5.9 × 3.9−4.5 μm.

Etymology

Armandii (Lat.): referring to the species growing on P. armandii.

Description

Basidiocarps annual, pileate, usually imbricate, leathery and without odor or taste when fresh, corky when dry. Pilei semicircular to fan-shaped, projecting up to 3 cm, 7 cm wide, and 8 mm thick at base. Pileal surface white to cream when juvenile, becoming olivaceous buff with age, at least reddish brown to dark reddish brown at base, crustose, distinctly zonate; margin cream, blunt. Pore surface white when fresh, cream when dry, not glancing; pores mostly round to angular, (3−)4−5 per mm; dissepiments thin, entire to slightly lacerate. Context cream, woody hard when dry, azonate, up to 5 mm thick, with a thin black line under crust except for the margin. Tubes cream to buff, hard corky, up to 3 mm long. Hyphal system dimitic; generative hyphae without clamp connections; tramal skeletal hyphae dextrinoid, CB+, contextual skeletal hyphae weakly IKI+, CB+; hyphae unchanged in KOH (not dissolved). Contextual generative hyphae frequently present, colorless, thin- to slightly thick-walled, frequently simple septate, occasionally branched, 3–4 mm diam; contextual skeletal hyphae dominant, colorless, thick-walled with a wide to narrow lumen, rarely branched, flexuous, interwoven, 4–5.5 mm diam. Tramal generative hyphae infrequent, hyaline, thin-walled, frequently simple septate, occasionally branched, 2–3 mm diam; tramal skeletal hyphae dominant, hyaline, thick-walled with a wide to narrow lumen, rarely branched, flexuous, strongly interwoven without orientation, 3–4 mm diam. Cystidia absent. Cystidioles present, fusiform, occasionally with an apical simple septum. Basidia clavate to ampullaceal, with a simple basal septum and four sterigmata, 14−24 × 6−8 mm. Basidioles in shape similar to basidia, but distinctly shorter. Basidiospores subglobose to broadly ellipsoid, hyaline, fairly thick-walled, asperulate, mostly bearing a small guttule, IKI−, CB+, (4.8−)4.9−5.9(−6) × (3.8−)3.9−4.5(−4.8) mm, L = 5.12 mm, W = 4.11 mm, Q = 1.24–1.25 (n = 60/2).

Additional materials (paratypes) examined

China, Yunnan Province, Xiping County, Mopanshan National Park, alt.1450 m, on stump of P. armandii, June 15, 2017, Dai 17606 (BJFC025138), Dai 17607 (BJFC025139); August 16, 2019, Dai 20410 (BJFC032078). Luquan County, Jiaozishan Forest Park, alt.2650 m, on stump of P. armandii, November 4, 2018, Dai 19258 (BJFC027726), Dai 19259 (BJFC027727), Dai 19260 (BJFC027728) and Dai 19261 (BJFC027729).

Heterobasidion subinsulare Y. C. Dai, Jia J. Chen and Yuan Yuan, sp. nov. Figures 4, 5

MycoBank MB 834573.

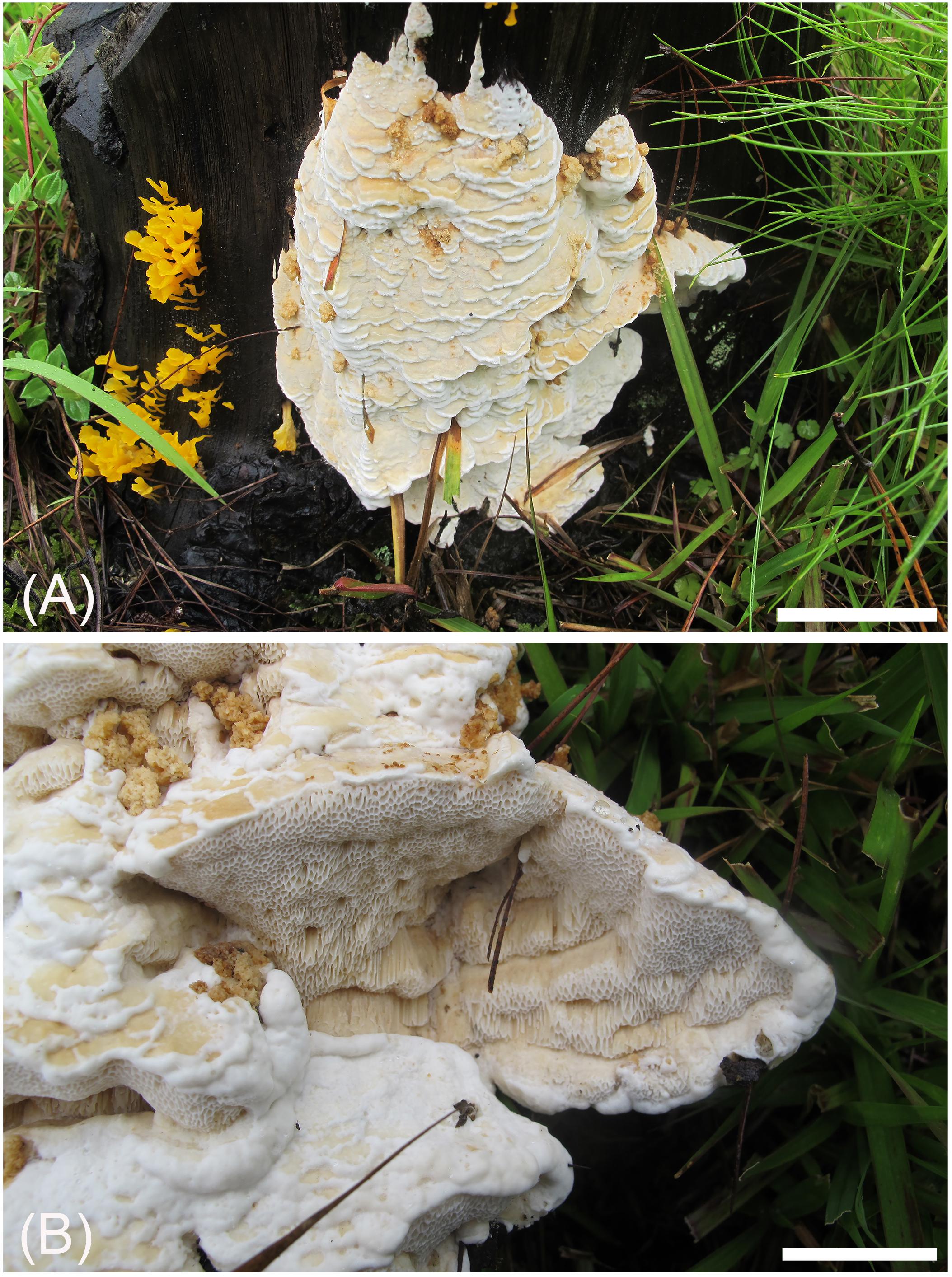

Figure 4. Basidiocarps of Heterobasidion subinsulare (holotype, Dai 13842). Bars (A) = 5 cm, (B) = 1 cm.

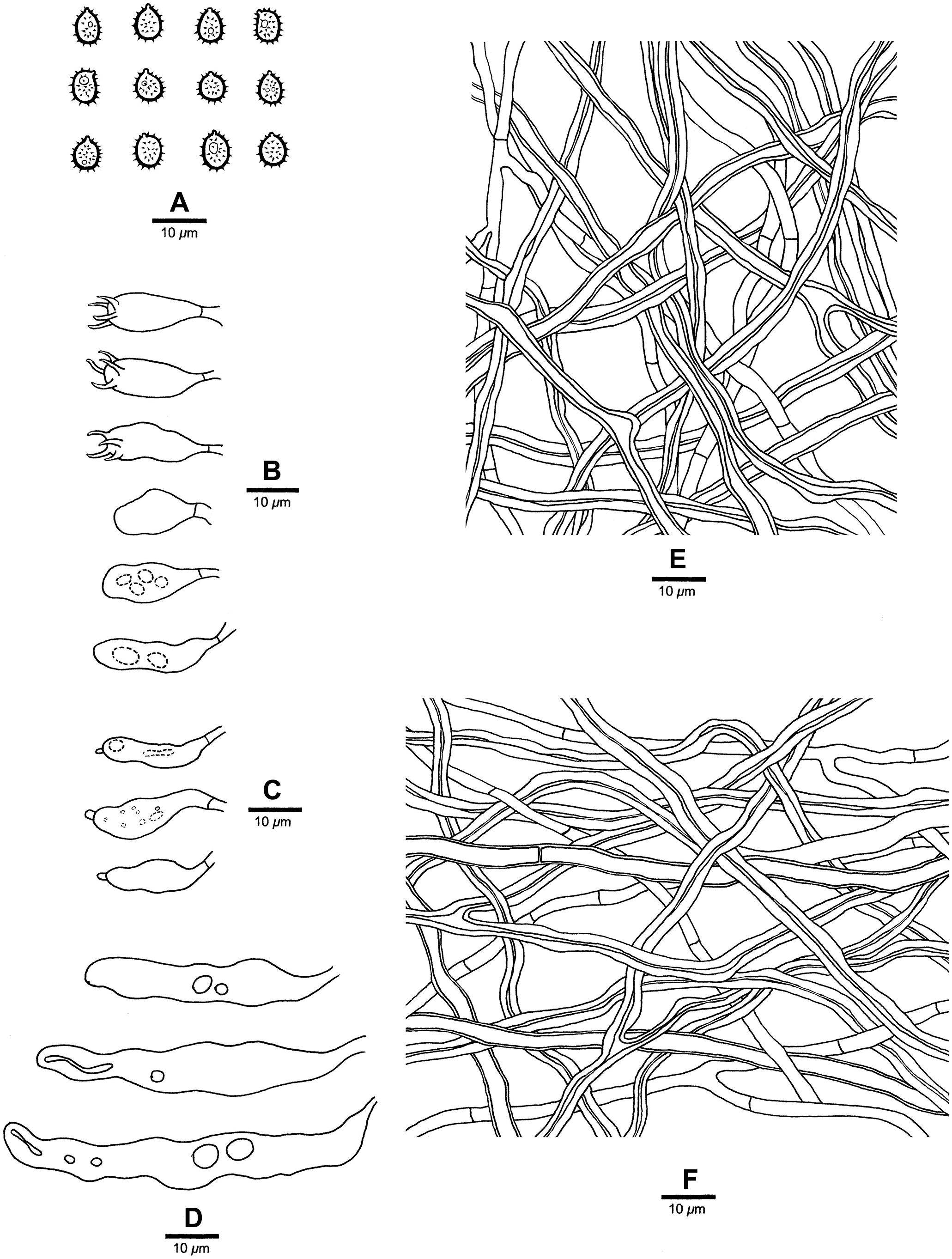

Figure 5. Microscopic structures of Heterobasidion subinsulare (drawn from the holotype). (A) Basidiospores; (B) Basidia and basidioles; (C) Cystidioles; (D) Cystidia; (E) Hyphae from trama; (F) Hyphae from context.

Type

China, Yunnan Province, Tengchong County, Shuanghe Village, on stump of Pinus sp., August 5, 2014, YC Dai 13842 (BJFC017572, holotype).

Diagnosis

Differs from Heterobasidion species by big pores (1–3 per mm), a non-glancing pore surface, its contextual skeletal hyphae are negative in Melzer’s reagent, presence of cystidia and cystidioles, and subglobose to broadly ellipsoid basidiospores measuring 5−5.7 × 3.8−5 μm.

Etymology

Subinsulare (Lat.): referring to the similarity to H. insulare.

Description

Basidiocarps annual, effused-reflexed to pileate, usually imbricate, leathery and without odor or taste when fresh, woody hard when dry. Pilei semicircular to fan-shaped, projecting up to 4 cm, 10 cm wide, and 4 cm thick at base. Pileal surface cream when dry, becoming buff to buff-yellow, crustose, azonate; margin buff-yellow to honey-yellow, blunt. Pore surface white when fresh, buff to clay-buff when dry, not glancing; pores angular to elongated, 1–3 per mm; dissepiments thin, entire to slightly lacerate. Context cream to buff-yellow, corky when dry, azonate, up to 0.5 cm thick. Tubes white to buff, hard corky, up to 3.5 cm long. Hyphal system dimitic; generative hyphae without clamp connections; skeletal hyphae CB+, dextrinoid near to the tube mouths, IKI− in other parts; hyphae unchanged in KOH (not dissolved). Contextual generative hyphae frequent, hyaline, thin- to slightly thick-walled, frequently simple septate and branched, 2–4 μm diam.; contextual skeletal hyphae dominant, hyaline, thick-walled with a wide lumen, rarely branched, flexuous, interwoven, 2.5–6 μm diam. Tramal generative hyphae frequent, hyaline, thin- to slightly thick-walled, occasionally simple septate, frequently branched, 2–3.5 μm diam; tramal skeletal hyphae dominant, hyaline, thick-walled with a wide lumen, rarely branched, flexuous, strongly interwoven without orientation, 2–5 μm diam. Cystidia present, thin-walled, clavate, moniliform or ventricose, 27−40 × 4−8 mm. Cystidioles present, thin-walled, fusiform, mostly with an apical simple septum, 22−25 × 4−8 μm. Basidia clavate to uniform, with a simple basal septum and four sterigmata, 18−28 × 4−6 μm. Basidioles in shape similar to basidia, but distinctly shorter. Basidiospores subglobose to broadly ellipsoid, hyaline, fairly thick-walled, asperulate, mostly bearing a small guttule, IKI−, CB+, (4.5−)5−5.7(−6) × (3.6−)3.8−5(−5.5) μm, L = 5.17 μm, W = 4.22 μm, Q = 1.22 (n = 30/1).

Additional material (paratype) examined

China, Yunnan Province, Tengchong County, on stump of Pinus sp., August 4, 2014, Li 140804-30 (BJFC018422).

Heterobasidion subparviporum Y. C. Dai, Jia J. Chen and Yuan Yuan, sp. nov. Figures 6, 7

MycoBank MB 834574.

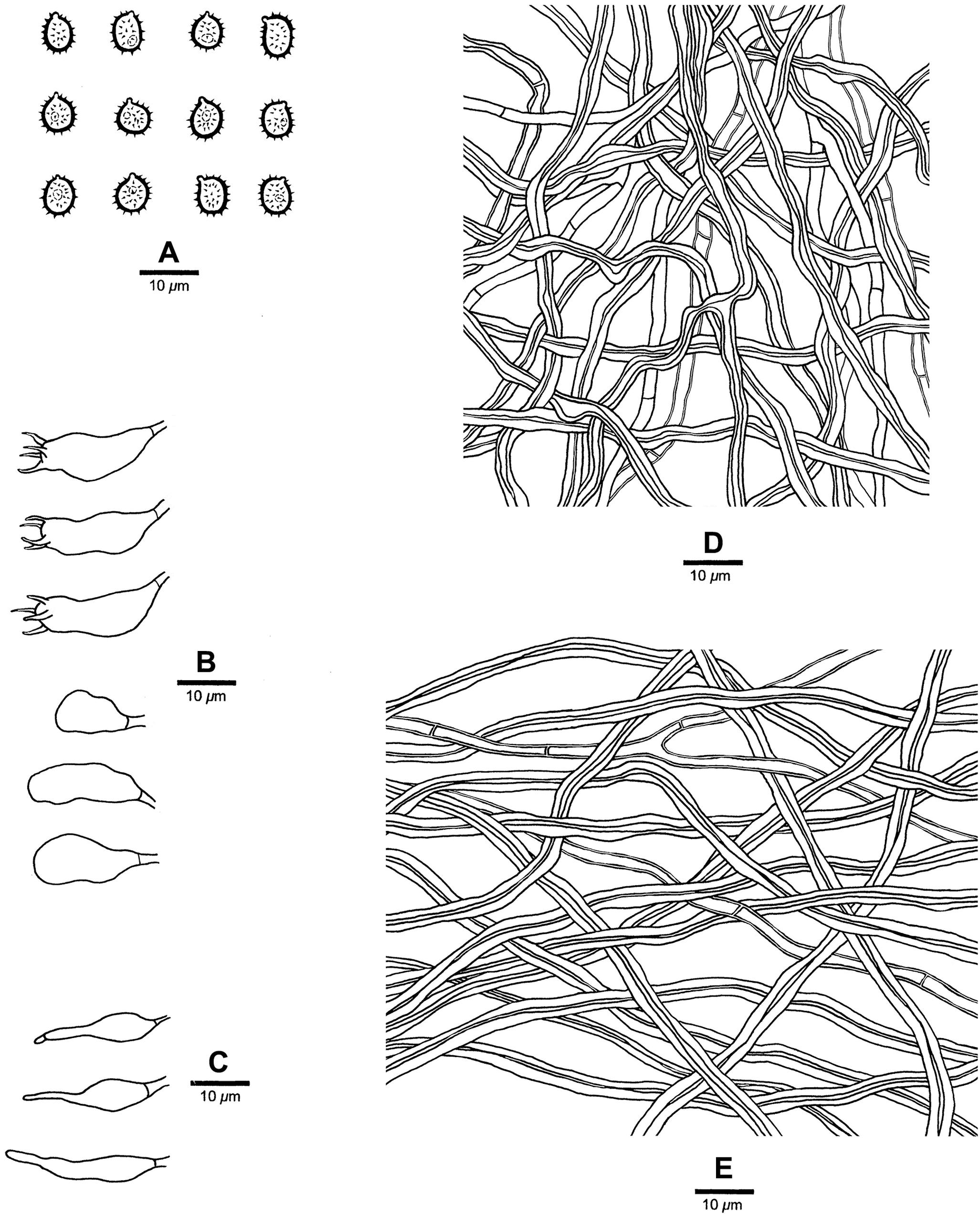

Figure 7. Microscopic structures of Heterobasidion subparviporum (drawn from the holotype). (A) Basidiospores; (B) Basidia and basidioles; (C) Cystidioles; (D) Hyphae from trama; (E) Hyphae from context.

Type

China, Hebei Province, Xinglong County, Wulingshan Nature Reserve, on fallen trunk of Larix sp., July 30, 2009, BK Cui 6961 (BJFC005448, holotype).

Diagnosis

Differs from Heterobasidion species by mostly round pores (3–5 per mm), amyloid contextual skeletal hyphae, absence of cystidia, presence of cystidioles, and subglobose to broadly ellipsoid basidiospores measuring 5−6.5 × 4−5.2 μm.

Etymology

Subparviporum (Lat.): referring to the similarity to H. parviporum.

Description

Basidiocarps perennial, pileate, usually imbricate, leathery and without odor or taste when fresh, hard corky when dry. Pilei semicircular to fan-shaped, projecting up to 6 cm, 9 cm wide, and 2.2 cm thick at base. Pileal surface buff to grayish brown or grayish dark, at least dark brown at base, crustose, distinctly zonate; margin cream to buff, dull, up to 2 mm. Pore surface white when fresh, cream to buff when dry, glancing; pores mostly round, occasionally irregular, 3–5 per mm; dissepiments thin, entire. Context buff to brown, corky when dry, azonate, up to 2 mm thick, with a thin black line under crust except for the margin. Tubes cream, hard corky, up to 20 mm long. Hyphal system dimitic; generative hyphae mostly simple septate; tramal skeletal hyphae dextrinoid, CB+; contextual skeletal hyphae IKI+, CB+, hyphae unchanged in KOH (not dissolved). Contextual generative hyphae infrequent, hyaline, thin-walled to slightly thick-walled, frequently simple septate and branched, 2–4 μm diam; contextual skeletal hyphae dominant, hyaline, thick-walled with a wide to narrow lumen, rarely branched, flexuous, interwoven, 2–4.5 μm diam. Tramal generative hyphae frequent, hyaline, thin-walled to slight thick-walled, frequently simple septate and branched, 1.7–3 μm diam; tramal skeletal hyphae dominant, hyaline, thick-walled with a narrow lumen, rarely branched, flexuous, strongly interwoven without orientation 1.5–3.5 μm diam. Cystidia absent. Cystidioles present, thin-walled, subulate, and ventricose, 13−26 × 4−6 μm, sometimes with a septum at the top. Basidia clavate to barrel-shaped, with a simple basal septum and four sterigmata, 18−24 × 4.5−8 μm. Basidioles in shape similar to basidia, but slightly smaller. Basidiospores subglobose to broadly ellipsoid, hyaline, fairly thick-walled, asperulate, IKI−, CB+, 5−6.5(−7) × (3.8−)4−5.2 μm, L = 5.65 μm, W = 4.35 μm, Q = 1.30–1.32 (n = 60/2).

Additional materials (paratypes) examined

China, Jilin Province, Antu County, Changbaishan Nature Reserve, on fallen trunk of Picea sp., September 13, 2014, Dai 14803 (BJFC017915); on living tree of Abies sp., September 21, 2019, Dai 20873 (BJFC032542). Xizang Autonomous Region (Tibet), Linzhi County, Lulang, on stump of Picea sp., September 16, 2010, Cui 9267 (BJFC008206).

Other materials examined

—Heterobasidion abietinum. Italy, on Abies sp., April 28, 2005, Dai 6557 (BJFC000943).

—Heterobasidion amyloideum. China, Xizang Auto. Reg. (Tibet), Linzhi County, Lulang, Sejila Mt., on fallen trunk of Abies sp., September 23, 2014, Cui 12274 (BJFC017155); Motuo County, on dead tree of Abies sp., September 21, 2014, Cui 12240 (BJFC017154); Milin County, Naligou, on fallen gymnosperm trunk, August 18, 2012, Li 1675 (isotype BJFC16026).

—Heterobasidion annosum. Belgium, on Betula sp., December 3, 2005, Dai 7445 (BJFC000949).

—Heterobasidion araucariae. New Zealand, March 20, 1985, PDD 49003 (PDD).

—Heterobasidion australe. China, Zhejiang Province, Jinan County, Tianmushan Nat. Res., stump of Pinus sp., October 15, 2004, Dai 6330 (paratype BJFC000979); Yunnan Province, Nanhua County, Dazhongshan Nature Reserve, on fallen trunk of Pinus sp., September 11, 2015, Cui 12602 (BJFC028381); Huaning County, September 6, 2013, Dai 13507 (BJFC014968); Kunming, Wild duck Lake, July 28, 2014, Dai 13863 (BJFC017593).

—Heterobasidion insulare. Philippines, Luzon, Mountain Province, on Pinus insularis, 1962, FPRI 429 (CFMR). China, Chongqing, Geleshan Forest Park, stump of Pinus sp., July 23, 2014, Dai 13933 (BJFC017663); Jiangxi Province, Anyuan County, Sanbaishan Forest Park, root of Pinus sp., December 19, 2014, Dai 15095 (BJFC018207).

—Heterobasidion irregulare. United States, on Pinus sp., 2004, JV0405/3-J (JV).

—Heterobasidion linzhiense. China, Xizang Auto. Reg. (Tibet), Linzhi County, Lulang, fallen trunk of Picea sp., September 24, 2010, Cui 9645 (holotype, BJFC008582).

—Heterobasidion occidentale. United States, on Abies sp., August 2001, JV0108/87 (JV).

—Heterobasidion orientale. China, Heilongjiang Province, Yichun, Liangshui Nature Reserve, on fallen gymnosperm trunk, August 26, 2014, Cui 11637 (BJFC016831); on fallen trunk of Pinus sp., August 28, 2014, Cui 11815 (BJFC016890); on dead tree of Picea, August 31, 2014, Cui 12026 (BJFC016964).

—Heterobasidion parviporum. Estonia, on Picea sp., May 13, 1995, Dai 1930 (BJFC001016).

—Heterobasidion sp. United States, California, Lassen National Forest, on Pinus ponderosa, March 2005, Korhonen 05030, Korhonen 05038 and Korhonen 05039 (LUKE).

—Heterobasidion tibeticum. China, Xizang Auto. Reg. (Tibet), Bomi County, Tongmai, on fallen trunk of Pinus sp., September 22, 2014, Cui 12257 (BJFC017171); Linzhi County, September 24, 2014, Cui 12335 (BJFC017249); July 31, 2004, Dai 5468 (paratype, BJFC000958).

Discussion

The current phylogeny considers that Heterobasidion species belong to three species complexes: the H. annosum F complex (previously treated as the H. annosum S group, Woodward et al., 1998), the H. annosum P complex and the H. insulare complex. The F complex of H. annosum includes four species which are mainly associated to true fir species (Abies Mill., Picea abies (L.) Karst. and Tsuga (Endl.) Carrière; Linzer et al., 2008; Dalman et al., 2010). H. subparviporum is mostly found on Picea in Asia, while H. parviporum is mostly associated to Picea in Europe and H. abietinum to Abies in Europe. H. occidentale is colonizing mostly Tsuga and Abies in western North America. The H. annosum P complex includes two taxa which mostly grow on pines: H. annosum s.s. in Eurasia, H. irregulare in North America (Linzer et al., 2008; Dalman et al., 2010). The H. insulare complex includes ten species which are associated to many species of Pinophyta (Abies, Araucaria Juss., Keteleeria Carr., Larix Mill., Picea, Pinus L., Pseudolarix Gordon, Pseudotsuga Carrière and Tsuga). H. araucariae, a species from Southern Hemisphere, is clustered into H. insulare complex, and is closely related to the species H. insulare and H. subinsulare (Figure 1).

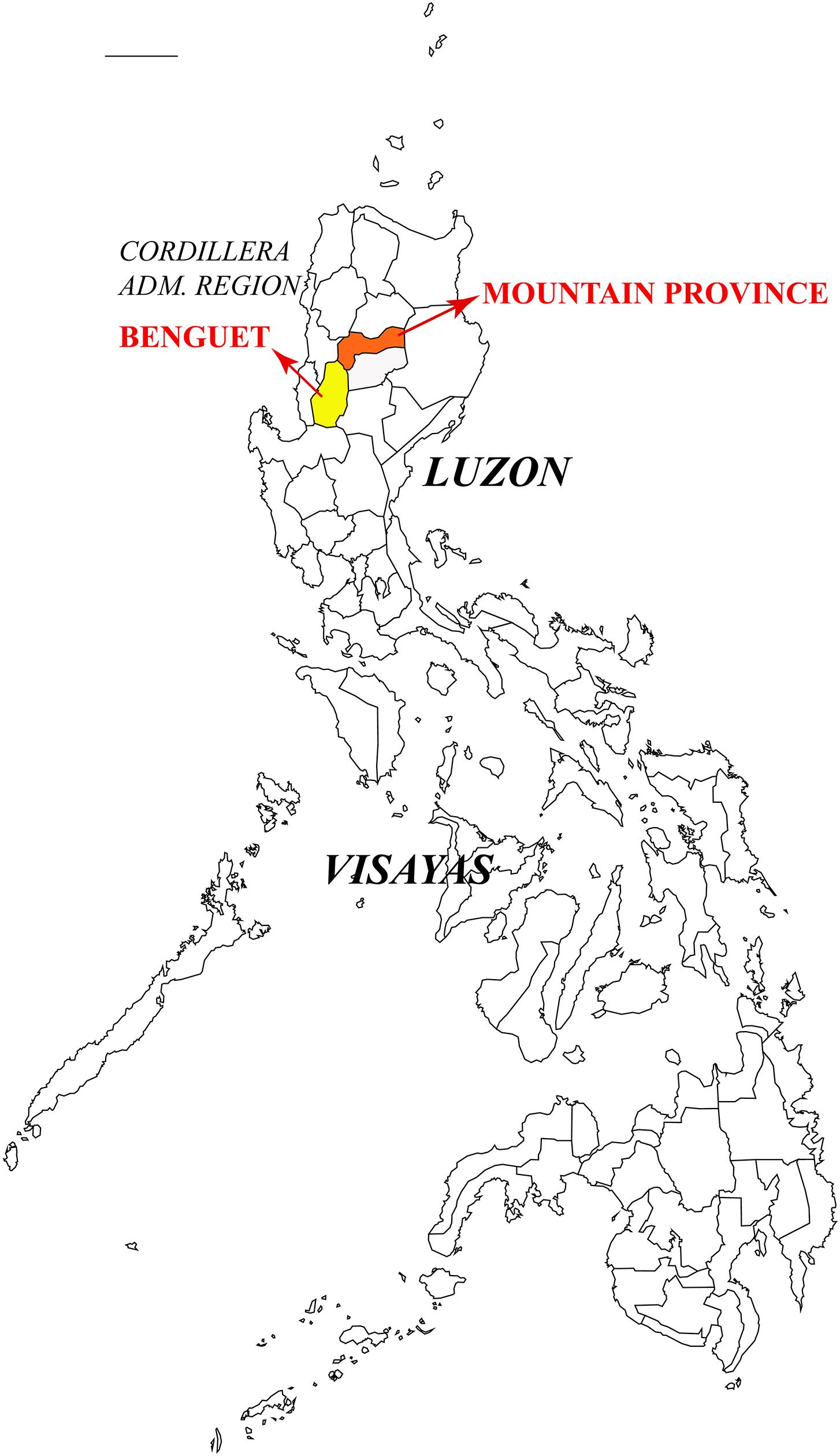

Heterobasidion insulare (=Trametes insularis Murrill) was originally described from Philippines (Murrill, 1908) and its type specimen was collected from fallen log of P. insularis in the Benguet Province, Luzon, Philippines in 1905. In 1962, Mendoza obtained the isolate FPRI-429 from P. insularis in the Mountain Province, Luzon. The Benguet Province and Mountain Province are both located in the Cordillera Administrative Region of Luzon Island (Figure 8). FPRI-429 can thus be considered as the type locality of H. insulare. The present results confirmed that FPRI-429 and representatives of H. ecrustosum are nested in the same lineage; the latter taxon was described from central Japan to Okinawa, and from southern China (Tokuda et al., 2009). We did not find any distinct morphological difference between the H. insulare type and samples of H. ecrustosum. Hence, according to the current phylogeny and morphological studies, H. ecrustosum is treated as a synonym of H. insulare.

Heterobasidion armandii is closely related to H. australe (Figure 1) and the geographical distributions of the two species are overlapped in China. However, H. australe is characterized by a glancing pore surface, lacks cystidioles, and its contextual skeletal hyphae are negative in Melzer’s reagent. Morphologically, H. armandii resembles H. amyloideum and H. tibeticum by similar pores (4–6 per mm in H. amyloideum and 3–6 per mm in H. tibeticum), basidiospores (4.9−5.8 × 3.9−4.5 μm in H. amyloideum and 4.5−6 × 3.6−5.3 μm in H. tibeticum) and amyloid contextual skeletal hyphae, but H. amyloideum and H. tibeticum differ from H. armandii by the presence of cystidia (Dai and Korhonen, 2009; Chen et al., 2014).

Heterobasidion subinsulare is closely related to H. insulare (Figure 1), but the latter lacks cystidia. H. subinsulare resembles H. amyloideum and H. tibeticum by having cystidia, but the latter two species have smaller pores (3–6 per mm) and amyloid contextual skeletal hyphae (Chen et al., 2014). H. subinsulare, H. araucariae, and H. orientale share similar pores, but H. araucariae can be distinguished from H. subinsulare by longer basidiospores (5.8–6.5 μm vs. 5–5.7 μm) and lacking of cystidia, and H. orientale differs from H. subinsulare by the sharp pileal margin, dark reddish pileal surface and lacking of cystidia. In addition, H. subinsulare is distantly related to H. amyloideum, H. tibeticum, H. araucariae, and H. orientale in our current phylogeny (Figure 1).

Heterobasidion subparviporum is closely related to H. parviporum (Figure 1), and the latter was considered as same as the former according to the mating tests (Dai and Korhonen, 1999, 2003; Dai et al., 2006; Dai, 2012). Although both taxa are compatible in laboratory, they form two distinct lineages in our phylogeny (Figure 1). Morphologically, H. subparviporum differs from H. parviporum by longer cystidia (18–24 μm vs. 13–17 μm) and bigger basidiospores (5−6.5 × 4−5.2 μm vs. 4.2−5 × 3.8−4.2 μm). In addition, H. parviporum is a pathogen on P. abies in Europe, while H. subparviporum seems to be a saprophytic species according to our investigations. Based on the above data, we suggest that this Asian taxon is a new species H. subparviporum. The situation is similar with the European taxa H. parviporum and H. abietinum. These two taxa are partly sexually compatible (Capretti et al., 1990; Stenlid and Karlsson, 1991; Woodward et al., 1998), but they do not produce hybrids in nature. So they have been accepted at the species level (Niemelä and Korhonen, 1998; Otrosina and Garbelotto, 2010; Ryvarden and Melo, 2017).

Heterobasidion irregulare was proposed by Otrosina and Garbelotto (2010), and it was originally described as Polyporus irregularis Underwood on pine log from Auburn, Alabama, eastern United States (Underwood, 1897), although P. irregularis is an illegitimate name because there was earlier a fungus named P. irregularis Pers. (Persoon, 1825). The lectotype (NY730756) of H. irregulare was selected from the type material of P. irregularis Underwood, and the epitype (UC1935442) was selected from stump of P. ponderosa in the Modoc National Forest, California, western United States. However, three isolates Korhonen 05030, Korhonen 05038, and Korhonen 05039 associated to P. ponderosa from Lassen National Forest in California formed another lineage which is closely related to H. irregulare (Figure 1). Hence it is possible that another taxon exists in western North America. We did not have the basidiocarps of isolates Korhonen 05030, Korhonen 05038, and Korhonen 05039, and no information on their ecology. For the time being we treat this possible taxon as H. sp.

Heterobasidion amyloideopsis was described from Pakistan mostly based on phylogenetic analysis (Zhao et al., 2017). We studied its ITS (KT598384, KT598385), nrLSU (KT598386, KT598387), RPB1 (KT598390, KT598391), and RPB2 (KT598388, KT598389) sequences and found some of the sequences are uncorrect, and some of these sequences were deleted by NCBI. So the status of H. amyloideopsis is ambiguous.

A comparison of these three new species and their morphological and/or phylogenetically related species is also provided in Supplementary Appendix 1. The phylogenetic analyses on single loci (ITS, nrLSU, RPB1, RPB2, and GAPDH) were shown in Supplementary Figures 1–5).

Conclusion

To date, 15 species are recorded in the genus Heterobasidion, including three new species described in the present study.

Five species, H. abietinum, H. annosum s.s., H. irregulare, H. occidentale, and H. parviporum, distributed in Europe and North America are forest pathogens. Ten Asian taxa are all saprotrophs, and the Asian countries ought to consider these five European and North American species as entry plant quarantine fungi. Parallelly, European countries should consider the American H. occidentale and H. irregulare as entry plant quarantine fungi (although the latter species is already in Italy), while North America should treat H. abietinum, H. annosum s.s. and H. parviporum as entry plant quarantine fungi. Eight Heterobasidion species found in the Himalayas suggest that the ancestral Heterobasidion species may have occurred in Asia, as was proposed also in the previous divergence and biogeographic studies on the genus.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

YY, J-JC, and Y-CD designed the research and contributed to data analysis and interpretation. YY and J-JC performed the research. Y-CD and KK collected the materials. All authors wrote and revised the manuscript, contributed to the article, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The research is supported by the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (STEP, No. 2019QZKK0503).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Bao-Kai Cui (China) for allowing us to study his collections. We express our gratitude to Dr. Daniel L. Lindner (CFMR, United States) for loan of stock, to Dr. De-Wei Li (United States) for providing some literatures and improving this manuscript, and to Chang-Lin Zhao (China) for providing sequences.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.596393/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Phylogeny of ITS.

Supplementary Figure 2 | Phylogeny of nrLSU.

Supplementary Figure 3 | Phylogeny of RPB1.

Supplementary Figure 4 | Phylogeny of RPB2.

Supplementary Figure 5 | Phylogeny of GAPDH.

Supplementary Appendix 1 | A comparison of taxa in the Heterobasidion.

Footnotes

References

Asiegbu, F. O., Abu, S., Stenlid, J., and Johansson, M. (2004). Sequence polymorphism and molecular characterization of laccase genes of the conifer pathogen Heterobasidion annosum. Mycol. Res. 108, 136–148. doi: 10.1017/S0953756203009183

Buchanan, P. K. (1988). A new species of Heterobasidion (Polyporaceae) from Australasia. Mycotaxon 32, 325–337.

Capretti, P., Korhonen, K., Mugnai, L., and Romagnoli, C. (1990). An intersterility group of Heterobasidion annosum, specialized to Abies alba. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 20, 231–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0329.1990.tb01134.x

Chen, J. J., Cui, B. K., Zhou, L. W., Korhonen, K., and Dai, Y. C. (2015). Phylogeny, divergence time estimation, and biogeography of the genus Heterobasidion (Basidiomycota, Russulales). Fungal Divers. 71, 185–200. doi: 10.1007/s13225-014-0317-2

Chen, J. J., Korhonen, K., Li, W., and Dai, Y. C. (2014). Two new species of the Heterobasidion insulare complex based on morphology and molecular data. Mycoscience 55, 289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.myc.2013.11.002

Dai, Y. C. (2012). Polypore diversity in China with an annotated checklist of Chinese polypores. Mycoscience 53, 49–80. doi: 10.1007/s10267-011-0134-3

Dai, Y. C., and Korhonen, K. (1999). Heterobasidion annosum group S identified in north-eastern China. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 29, 273–279. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0329.1999.00153.x

Dai, Y. C., and Korhonen, K. (2003). First report of Heterobasidion parviporum (S group of H. annoum sensu lato) on Tsuga spp. in Asia. Plant Dis. 87:1007. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2003.87.8.1007B

Dai, Y. C., and Korhonen, K. (2009). Heterobasidion australe, a new polypore derived from the Heterobasidion insulare complex. Mycoscience 50, 353–356. doi: 10.1007/S10267-009-0491-3

Dai, Y. C., Vainio, E. J., Hantula, J., Niemelä, T., and Korhonen, K. (2002). Sexuality and intersterility within the Heterobasidion insulare complex. Mycol. Res. 106, 1435–1448. doi: 10.1017/S0953756202006950

Dai, Y. C., Vainio, E. J., Hantula, J., Niemelä, T., and Korhonen, K. (2003). Investigations on Heterobasidion annosum s.lat. in central and eastern Asia with the aid of mating tests and DNA fingerprinting. For. Pathol. 33, 269–286. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0329.2003.00328.x

Dai, Y. C., Yu, C. J., and Wang, H. C. (2007). Polypores from eastern Xizang (Tibet), western China. Ann. Bot. Fenn. 44, 135–145.

Dai, Y. C., Yuan, H. S., Wei, Y. L., and Korhonen, K. (2006). New records of Heterobasidion parviporum in China. For. Pathol. 36, 287–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0329.2006.00458.x

Dalman, K., Olson, A., and Stenlid, J. (2010). Evolutionary history of the conifer root rot fungus Heterobasidion annosum sensu lato. Mol. Ecol. 19, 4979–4993. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04873.x

Farris, J. S., Källersjö, M., Kluge, A. G., and Bult, C. (1994). Testing significance of incongruence. Cladistics 10, 315–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.1994.tb00181.x

Felsenstein, J. (1985). Confidence intervals on phylogenetics: an approach using bootstrap. Evolution 39, 783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x

Gilbertson, R. L., and Ryvarden, L. (1986). North American Polypores 1. Abortiporus - Lindtneria. Oslo: Fungiflora, 1–433.

Hall, T. A. (1999). Bioedit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41, 95–98.

Huelsenbeck, J. P., Bull, J. J., and Cunningham, E. (1996). Combining data in phylogenetic analysis. Trends Ecol. Evol. 11, 152–158. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(96)10006-9

Johannesson, H., Renvall, P., and Stenlid, J. (2000). Taxonomy of Antrodiella inferred from morphological and molecular data. Mycol. Res. 104, 92–99. doi: 10.1017/S0953756299008953

Johannesson, H., and Stenlid, J. (2003). Molecular markers reveal genetic isolation and phylogeography of the S and F intersterility group of the wood-decay fungus Heterobasidion annosum. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 29, 94–101. doi: 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00087-3

Justo, A., and Hibbett, D. S. (2011). Phylogenetic classification of Trametes (Basidiomycota, Polyporales) based on a five-marker dataset. Taxon 60, 1567–1583. doi: 10.1002/tax.606003

Korhonen, K. (1978). Intersterility groups of Heterobasidion annosum. Commun. Inst. For. Fenn. 94:25.

Linzer, R. E., Otrosina, W. J., Gonthier, P., Bruhn, J., Laflamme, G., Bussières, G., et al. (2008). Inferences on the phylogeography of the fungal pathogen Heterobasidion annosum, including evidence of interspecific horizontal genetic transfer and of human-mediated, long range dispersal. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 46, 844–862. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.12.010

Liu, Y. J., Whelen, S., and Hall, B. D. (1999). Phylogenetic relationship among ascomycetes: evidence from an RNA polymerase II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 1799–1808. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026092

Maijala, P., Harrington, T. C., and Raudaskoski, M. (2003). A peroxidase gene family and gene trees in Heterobasidion and related genera. Mycologia 95, 209–221. doi: 10.2307/3762032

Matheny, P. B. (2005). Improving phylogenetic inference of mushrooms with RPB1 and RPB2 nucleotide sequences (Inocybe; Agaricales). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 35, 1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.11.014

Matheny, P. B., Liu, Y. J., Ammirati, J. F., and Hall, B. D. (2002). Using RPB1 sequences to improve phylogenetic inference among mushrooms (Inocybe, Agaricales). Am. J. Bot. 89, 688–698. doi: 10.3732/ajb.89.4.688

Murrill, W. A. (1908). Additional philippine polyporaceae. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 35, 391–416. doi: 10.2307/2479285

Niemelä, T., and Korhonen, K. (1998). “Taxonomy of the genus Heterobasidion,” in Heterobasidion annosum: Biology, Ecology, Impact and Control, eds S. Woodward, J. Stenlid, R. Karjalainen, and A. Hüttermann (Oxon: CAB International), 27–33. doi: 10.14492/hokmj/1381758488

Núñez, M., and Ryvarden, L. (2001). East Asian polypores 2. Polyporaceae s. lato. Syn. Fung. 14, 469–522.

Nylander, J. A. A. (2004). MrModeltest 2.2. Program Distributed by the Author. Uppsala: Uppsala University.

Ota, Y., Tokuda, S., Buchanan, P. K., and Hattori, T. (2006). Phylogenetic relationships of Japanese species of Heterobasidion – H. annosum sensu lato and an undetermined Heterobasidion sp. Mycologia 98, 717–725. doi: 10.3852/mycologia.98.5.717

Otrosina, W. J., Chase, T. E., Cobb, F. W., and Korhonen, K. (1993). Population structure of Heterobasidion annosum from North America and Europe. Can. J. Bot. 71, 1064–1071. doi: 10.1139/b93-123

Otrosina, W. J., and Garbelotto, M. (2010). Heterobasidion occidentale sp. nov. and Heterobasidion irregulare nom. nov.: a disposition of North American Heterobasidion biological species. Fungal Biol. 114, 16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2009.09.001

Page, R. D. M. (1996). Treeview: application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 12, 357–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357

Petersen, J. H. (1996). Farvekort. The Danish Mycological Society’s Color-Chart. Greve: Foreningen til Svampekundskabens Fremme.

Ronquist, F., and Huelsenbeck, J. P. (2003). MrBayes 3: bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180

Stenlid, J., and Karlsson, J. O. (1991). Partial intersterility in Heterobasidion annosum. Mycol. Res. 95, 1153–1159. doi: 10.1016/S0953-7562(09)80004-X

Swofford, D. L. (2002). PAUP∗: Phylogenetic analysis Using Parsimony (∗and other Methods), version 4.0 Beta. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer.

Thompson, J. D., Gibson, T. J., Plewniak, F., Jeanmougin, F., and Higgins, D. G. (1997). The CLUSTAL X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876

Tokuda, S., Hattori, T., Dai, Y. C., Ota, Y., and Buchanan, P. K. (2009). Three species of Heterobasidion (Basidiomycota, Hericiales), H. parviporum, H. orientale sp. nov. and H. ecrustosum sp. nov. from East Asia. Mycoscience 50, 190–202. doi: 10.1007/S10267-008-0476-7

Underwood, L. M. (1897). Some new fungi, chiefly from Alabama. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 24, 81–86. doi: 10.2307/2477799

Vilgalys, R., and Hester, M. (1990). Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 172, 4238–4246. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4238-4246.1990

White, T. J., Bruns, T., Lee, S., and Taylor, J. W. (1990). “Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics,” in PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications, eds M. A. Innis, D. H. Gelfand, J. J. Sninsky, and T. J. White (New York, NY: Academic Press), 315–322. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-372180-8.50042-1

Woodward, S., Stenlid, J., Karjalainen, R., and Hüttermann, A. (1998). “Preface,” in Heterobasidion annosum: Biology, Ecology, Impact and Control, eds S. Woodward, J. Stenlid, R. Karjalainen, and A. Huttermann (Oxon: CAB International), xi–xii.

Keywords: taxonomy, phylogeny, new taxa, Bondarzewiaceae, pathogenic fungi

Citation: Yuan Y, Chen J-J, Korhonen K, Martin F and Dai Y-C (2021) An Updated Global Species Diversity and Phylogeny in the Forest Pathogenic Genus Heterobasidion (Basidiomycota, Russulales). Front. Microbiol. 11:596393. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.596393

Received: 19 August 2020; Accepted: 30 November 2020;

Published: 07 January 2021.

Edited by:

Peter Edward Mortimer, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, ChinaReviewed by:

Jan Stenlid, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SwedenSamantha Chandranath Karunarathna, Kunming Institute of Botany, China

Copyright © 2021 Yuan, Chen, Korhonen, Martin and Dai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yu-Cheng Dai, eXVjaGVuZ2RAeWFob28uY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Yuan Yuan

Yuan Yuan Jia-Jia Chen

Jia-Jia Chen Kari Korhonen4

Kari Korhonen4 Francis Martin

Francis Martin Yu-Cheng Dai

Yu-Cheng Dai