94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol., 12 June 2020

Sec. Fungi and Their Interactions

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01043

Benzothiazole (BT) has a strong inhibitory effect on the growth and development of a wide spectrum of fungi and insects, such as Botrytis cinerea and Bradysia odoriphaga, that cause serious losses in agriculture. To investigate the underlying antifungal and insecticidal mechanisms of BT, RNA-seq analysis was performed for B. cinerea after BT treatment for 12, 24, and 48 h and for B. odoriphaga after BT treatment for 6 and 24 h. In B. cinerea, the pectin degradation process was inhibited, suggesting a low utilization of carbohydrate sources. As the treatment time was extended, the cell walls of B. cinerea thickened, and increases in melanin synthesis and ion transport were observed. In B. odoriphaga, signaling pathways including MAPK, insulin, adipocytokine, forkhead box class O, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor were activated at 6 h, and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase was the core gene in the signal transduction pathways that responded to BT; digestive system and melanogenesis genes were obviously altered at 24 h. In addition, we identified several insecticidal target genes, such as trypsin, aminopeptidase N, and tyrosinase. Benzothiazole significantly affected nutrient metabolism, especially carbohydrate metabolism, in both species, and the pentose and glucuronate interconversions pathway was shared by both species, although the individual genes were different in each species. Overall, our results suggested that BT was a melanogenesis disrupter for the insect but an activator for the fungus. Our findings are helpful for deeply exploring the genes targeted by BT and for developing new pesticide compounds with unique mechanisms of action.

Benzothiazole (BT) is a volatile compound with a privileged bicyclic ring system that exists in many microorganisms (e.g., Aspergillus clavatus and Bacillus subtilis) (Seifert and King, 1982; Liu et al., 2009b) and natural plant products (e.g., grapes, tea leaves, and cranberries) (Ferrandino et al., 2012; Keri et al., 2015). It is known in the field of medicine that BT derivates have a wide spectrum of pharmacological activities (Ali and Siddiqui, 2013). Benzothiazole is a structure with an inherent affinity for different biological receptors and provides an ideal source of core scaffolds for targeted molecules in the design of new active compounds (Keri et al., 2015). Numerous therapeutic agents have been synthesized based on the BT nucleus, and this chemical family has attracted the attention of medicinal chemists. The primary results obtained in our research group have indicated that BT exhibits strong inhibition of a wide spectrum of fungi (e.g., Botrytis cinerea, Fusarium oxysporum, and Colletotrichum capsici) and insects (e.g., Bradysia odoriphaga and Tribolium castaneum) (Zhao et al., 2011). These results suggested that BT also has strong activity against fungi and pests in agriculture. Therefore, understanding the novel compound BT is important for synthesizing and developing other effective fungicides or insecticides.

Among the species that we tested with BT, the fungus B. cinerea and the insect B. odoriphaga were the most sensitive (Zhao et al., 2011). B. cinerea is the second most important plant pathogenic fungus in the world (Dean et al., 2012) and affects more than 200 plant species at the pre- and postharvest stages, resulting in massive losses during growth, transport, storage, and commercialization (Williamson et al., 2007). Benzothiazole has no cross-resistance with several fungicides currently used to control B. cinerea, such as carbendazim, procymidone, and pyrimethanil (Cui et al., 2017), suggesting that BT has a unique mechanism of action. B. odoriphaga is the most important pest attacking the Chinese chive (Allium tuberosum) and also affects other crops such as cabbage (Brassica oleracea), garlic (Allium sativum), and shallot (Allium ascalonicum) (Mei et al., 2003). Its larvae feed on roots, bulbs, and young stems, resulting in 30–80% production losses. Chen et al. (2014) verified that BT has strong fumigation activity against all developmental stages of B. odoriphaga. Considering that fruit and vegetable storage as well as soil fumigation may be possible applications of the volatile compound BT, choosing the pathogen B. cinerea and the insect B. odoriphaga as research subjects seemed suitable. Since BT has inhibitory activity against both B. cinerea and B. odoriphaga, the same target or mechanism of action of BT may be present in this pathogen and insect pest.

Although BT has useful antifungal and insecticidal activity, the unique mechanism of action of BT is largely unknown. Fortunately, next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based RNA-seq analysis provides efficient and rapid discovery of genes in the study of molecular biology (Schuster, 2008). Many genes involved in the inhibitory effects of exogenous compounds in fungi have been identified through transcriptome analyses (Chang et al., 2015; Lv et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019; Ren et al., 2020).

Uncovering the mechanism of action of BT is helpful for synthesizing similar active compounds in agricultural management of agricultural disease and pests. In the current study, we investigated the transcriptome responses of the fungus B. cinerea and the insect pest B. odoriphaga when exposed to BT, to identify their similarities and differences. Significantly changed pathways and potential target genes of BT were comprehensively analyzed, and the results will benefit the exploration of the potential mechanism underlying the antifungal and insecticidal activities of BT and the development of future novel pesticides.

As described in our previous study, B. cinerea is highly sensitive to BT (Cui et al., 2017). An isolate, SX-9, was selected for the following study to explore the effect of BT on B. cinerea. The B. cinerea SX-9 isolate used in this study was collected from a pepper greenhouse in Shandong Province, China, and it was obtained by the single-spore method and maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA; DifcoTM BD Diagnostics, Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States) plates. After a 24-h incubation period at 25°C in the dark (considered 0 h), B. cinerea isolate SX-9 was fumigated with 0.5 μL of BT (purity of 99%; Beijing Lark Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) in 200 mL-volume fumigation plates, to create a final concentration of 2.5 μL/L (the concentration that caused 50% inhibition given 24 h of preincubation). For comparison, PDA plates without BT were used as controls. The mycelia were collected at three specific time points (12, 24, and 48 h) and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen. Thus, six groups were subjected to RNA-seq, including the control (CON) at 12, 24, and 48 h and BT treatment at 12, 24, and 48 h. There were three biological replicates for each treatment, and mycelia collected from 10 PDA plates were pooled to form one biological replicate.

The culture of B. odoriphaga was previously described (Zhao et al., 2016a, b). The population of B. odoriphaga has been cultured in the laboratory since 2013. Fresh chive rhizomes in 1-cm pieces were used to rear the insects, which were maintained in Petri dishes at 25 ± 1°C with 70 ± 5% relative humidity and a 14:10 (light:dark) photoperiod. The newly emerged 4th instar larvae of B. odoriphaga were transferred from the Petri dishes and fumigated with the LC30 of BT (0.47 μL/L) in fumigation aquariums (10 L, 20 cm × 20 cm × 25 cm) at 25°C. After fumigation with BT for 6 h and 24 h, the live larvae in the BT and control groups were collected. Three biological replicates of 20 larvae each were frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was carried out to investigate the mechanism of action of BT on the ultrastructure of B. cinerea. Hyphae samples were collected from the edges of control and BT-treated B. cinerea colonies. The hyphae were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 2 h at 4°C. After rinsing in the same buffer several times, the samples were postfixed in 1% OsO4 in the same buffer for 2 h at 4°C, dehydrated through an ethanol series, and embedded in Epon-Araldite resin. Thick sections were prepared with an LKB ultramicrotome, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and viewed under a JEOL 1200EX transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). The thickness of the cell wall was also measured and recorded. Due to the complexity of the larval body and the lack of a predicted specific site of action of BT, we did not observe B. odoriphaga by TEM.

Total RNA was extracted from frozen B. cinerea mycelial samples using an E.Z.N.A. Fungal RNA Kit (Omega, Norcross, GA, United States). Total RNA was extracted from B. odoriphaga samples using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, United States) and treated with DNase I. The RNA integrity value was confirmed with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, United States). The concentration and purity of the RNA were determined with a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). According to the manufacturer’s (Illumina) protocol, poly-(A) messenger RNA (mRNA) was isolated using oligo-(dT) magnetic beads and fragmented into short pieces using fragmentation buffer. Random hexamer primers were used to synthesize cDNA. After purification for terminal repair and adaptor ligation, the products were amplified through PCR to create cDNA libraries. Then, the B. cinerea and B. odoriphaga libraries were sequenced on a BGISEQ-500 platform and an Illumina HiSeqTM 4000 platform, respectively, at the Beijing Genomics Institution (BGI, ShenZhen, China).

For the B. cinerea transcriptome, the raw reads from the sequencing machine were cleaned by filtering out the adaptor reads, low-quality reads (bases with quality value ≤5 accounting for more than 50% of the read), and reads with unknown bases accounting for more than 10% of the read. The clean reads were saved in FASTQ format and then mapped to the B. cinerea B05.10 genome database using HISAT (Kim et al., 2015) with no more than two base mismatches. The gene expression level was normalized and estimated by FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads) (Sims et al., 2014). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were screened between the CON and BT treatments at each time point using the NOISeq method (Tarazona et al., 2011). Genes with a combination of probability ≥ 0.8, FDR ≤ 0.001 and absolute value of log2 ratio ≥ 1 were considered DEGs.

For the B. odoriphaga transcriptome, the raw reads from the sequencing machine were cleaned by filtering out the adaptor reads, low-quality reads (bases with quality value ≤15 accounting for more than 20% of the read), and reads with unknown bases accounting for greater than 5% of the read. Trinity software (Grabherr et al., 2011) was used to perform de novo assembly with the clean reads, and the TGICL package (Pertea et al., 2003) was used to cluster the transcripts into unigenes. To obtain a comprehensive functional annotation, unigenes were determined using the BLAST program (Altschul et al., 1990) by querying against public functional databases as follows: National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) non-redundant nucleotide sequences (NT), NCBI non-redundant protein sequences (NR), Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins (COG), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and Swiss-Prot. Blast2GO (Conesa et al., 2005) with NR annotation was used to obtain the Gene Ontology (GO) annotation and InterProScan 5 (Quevillon et al., 2005) was used to obtain the InterPro annotations. Bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) was used to map the clean reads to the assembled unigenes, and RSEM (Li and Dewey, 2011) was used to obtain the read count for each unigene in each sample. The gene expression level was normalized and estimated by FPKM. Differentially expressed genes were screened between the CON and BT treatments at each time point using DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014). Genes with both an absolute value of log2 ratio ≥ 1 and an adjusted P-value ≤ 0.05 were considered DEGs.

The Blast2GO program was used to assign all the DEGs to GO categories, and WEGO software (Ye et al., 2006) was used to perform functional classification of GO terms. In addition, GO (Ashburner et al., 2000) and KEGG (Kanehisa and Goto, 2000) pathway enrichment analyses were performed on the DEGs. Gene Ontology terms with a threshold-corrected P-value ≤ 0.05 were considered significantly enriched in DEGs, and KEGG pathways that fulfilled the criterion of Q-value ≤ 0.05 were defined as significantly enriched.

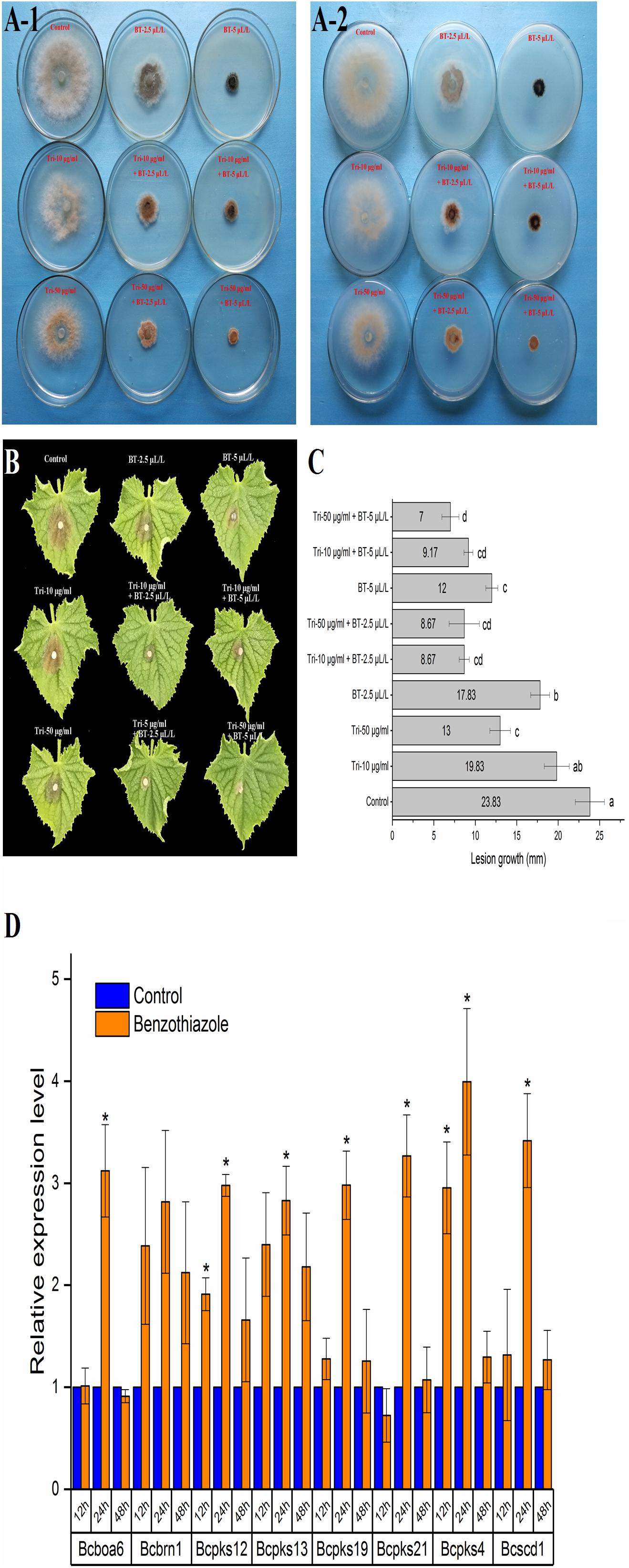

In the fumigation assay, we found, by accident, that BT may accelerate the melanization of B. cinerea. Therefore, we performed a series of tests to verify this phenomenon and investigated whether this effect could affect mycelial growth and virulence. Mycelial plugs (5 mm) from the edges of 3-day-old colonies were inoculated on the centers of PDA plates with or without tricyclazole, an inhibitor of fungal dihydroxynaphthalene (DHN) melanin biosynthesis (Zhang et al., 2015). We set three concentrations of tricyclazole at 0, 10 and 50 μg/mL. Beyond that, 0.5 or 1 μL of BT (final concentration of 2.5 or 5 μL/L) was added to each plate to build a fumigation environment. Plates without BT and tricyclazole were used as controls. Every treatment consisted of six parallel samples. The diameter of each mycelium colony was measured after two days, and a photograph of B. cinerea colony melanization was observed and recorded. Then, mycelium plugs from the edge of each B. cinerea colony in each treatment were inoculated on detached cucumber leaves (one plug per leaf) to verify the role of melanin in the virulence of B. cinerea. The infected leaves were maintained in a container with 85% relative humidity at 25°C with a photoperiod of 12 h. The lesion diameter minus 5 mm (the diameter of the mycelium plug) was considered the lesion growth diameter. There were six cucumber leaves for each treatment. In addition, we identified the expression levels of seven melanin biosynthesis-related genes using reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR).

Gene-specific primers for RT-qPCR were designed using the Beacon Designer 7.0 program, and their sequence information is listed in Supplementary Table S1. Total RNA was extracted from frozen B. cinerea mycelia and B. odoriphaga larvae samples using an E.Z.N.A. Fungal RNA Kit and TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, United States), respectively. Then, 1 μg of RNA for each sample was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA using the TransScript All-in-One First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for qPCR Kit (Transgen Biotech, Beijing, China). Reverse transcription quantitative PCR analysis was performed using TransStart® Top Green qPCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) on a Light Cycler 96 system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Each 20 μL reaction mixture contained 10 μL of 2 × TransStart® Top Green qPCR SuperMix, 0.4 μL of each forward and reverse primer, 8.2 μL of double distilled water and 1 μL of cDNA. The cycling program was 94°C for 30 s, followed by 45 cycles at 94°C for 5 s, 56°C for 15 s and 72°C for 10 s. There were three biological replicates and three technical replicates for each gene of each sample. β-tubulin and ribosomal protein S15 (RPS15; Shi et al., 2016) were used as the internal control genes for the RT-qPCR analyses of B. cinerea and B. odoriphaga, respectively. The relative gene expression level in each comparison between a BT-treated sample and its control was calculated using the 2– ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). The statistical analysis was performed with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD method (P < 0.05) via SPSS 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

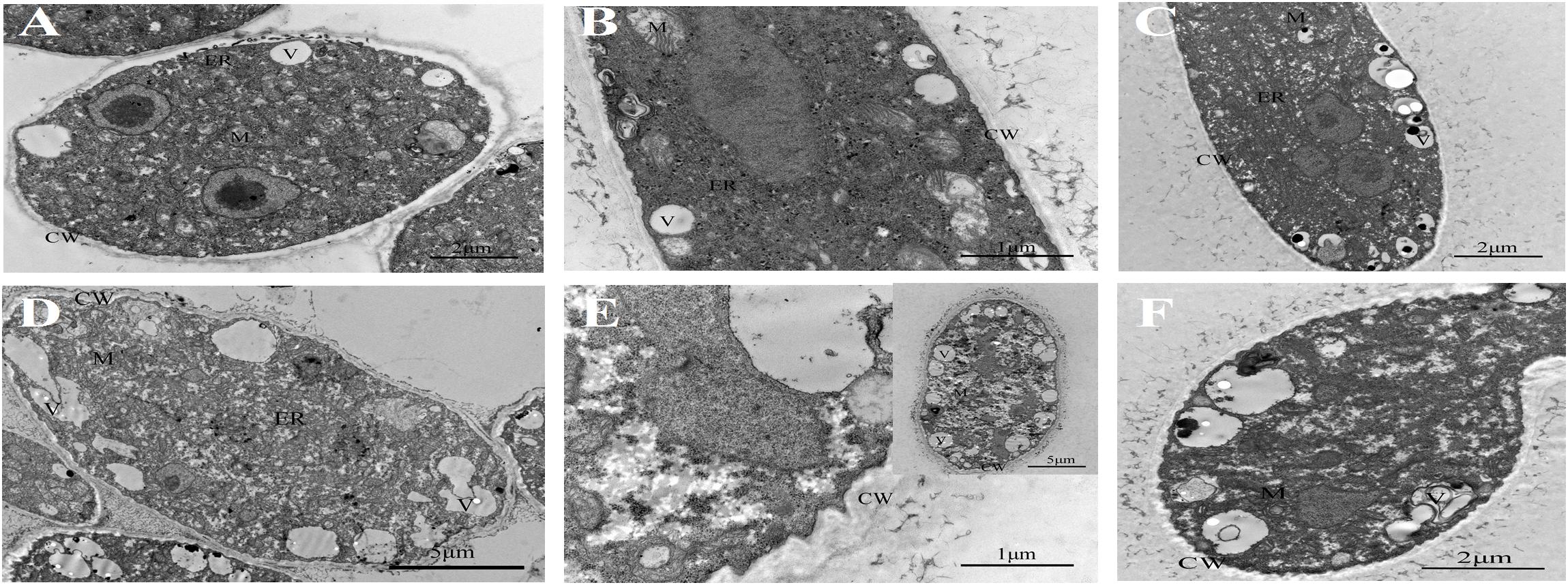

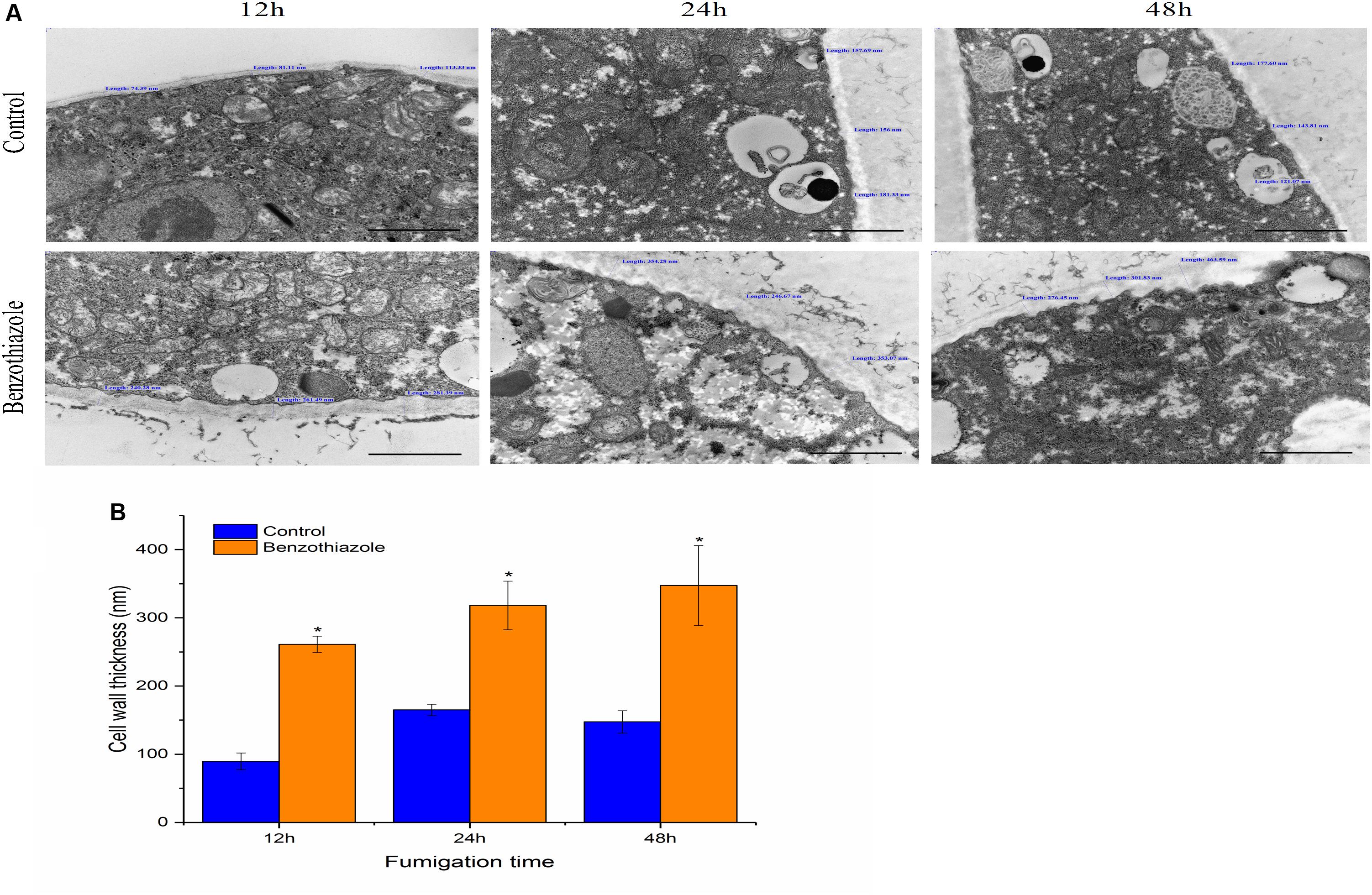

Untreated B. cinerea showed normal organelles, including regularly shaped mitochondria and rough endoplasmic reticulum (Figures 1A–C). When B. cinerea was treated with 2.5 μL/L BT for 12 h, some large, anomalous vacuoles were observed (Figure 1D). As the fumigation time was prolonged, the vacuolization increased, and the organelles became indistinguishable in the cytoplasm (Figures 1E,F). Most obviously, greatly increased cell wall thickness was observed in the BT-treated samples, and there was a positive correlation between fumigation time and cell wall thickness (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Transmission electron micrographs of Botrytis cinerea with or without benzothiazole treatment. (A–C) Untreated B. cinerea at 12, 24, and 48 h. Many organelles were observed, including the cell wall (CW), vacuole (V), mitochondria (M) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER). (D–F) B. cinerea hyphae after fumigation with benzothiazole for 12, 24, and 48 h, showing many anomalous vacuoles, significant thickening of the cell wall, and indistinguishable organelles in the cytoplasm.

Figure 2. Effects of benzothiazole on the cell wall thickness of Botrytis cinerea (scale bar = 1 μm). (A) High magnification of the cell wall of B. cinerea showing thickness measured at three different positions of the cell wall. (B) Statistical analysis of the cell wall thickness of benzothiazole-treated and control B. cinerea. The asterisk indicates a significant difference from the respective control.

Six libraries with three biological replicates per treatment were constructed. The RNA-seq analysis data were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) (SRP174462). Approximately 23 million clean reads were generated per sample, with >86% of reads mapping to the B. cinerea B05.10 genome, and an average of 81% of these reads were matched uniquely (Supplementary Table S2). The expression levels of 15,451 genes were calculated using the FPKM method.

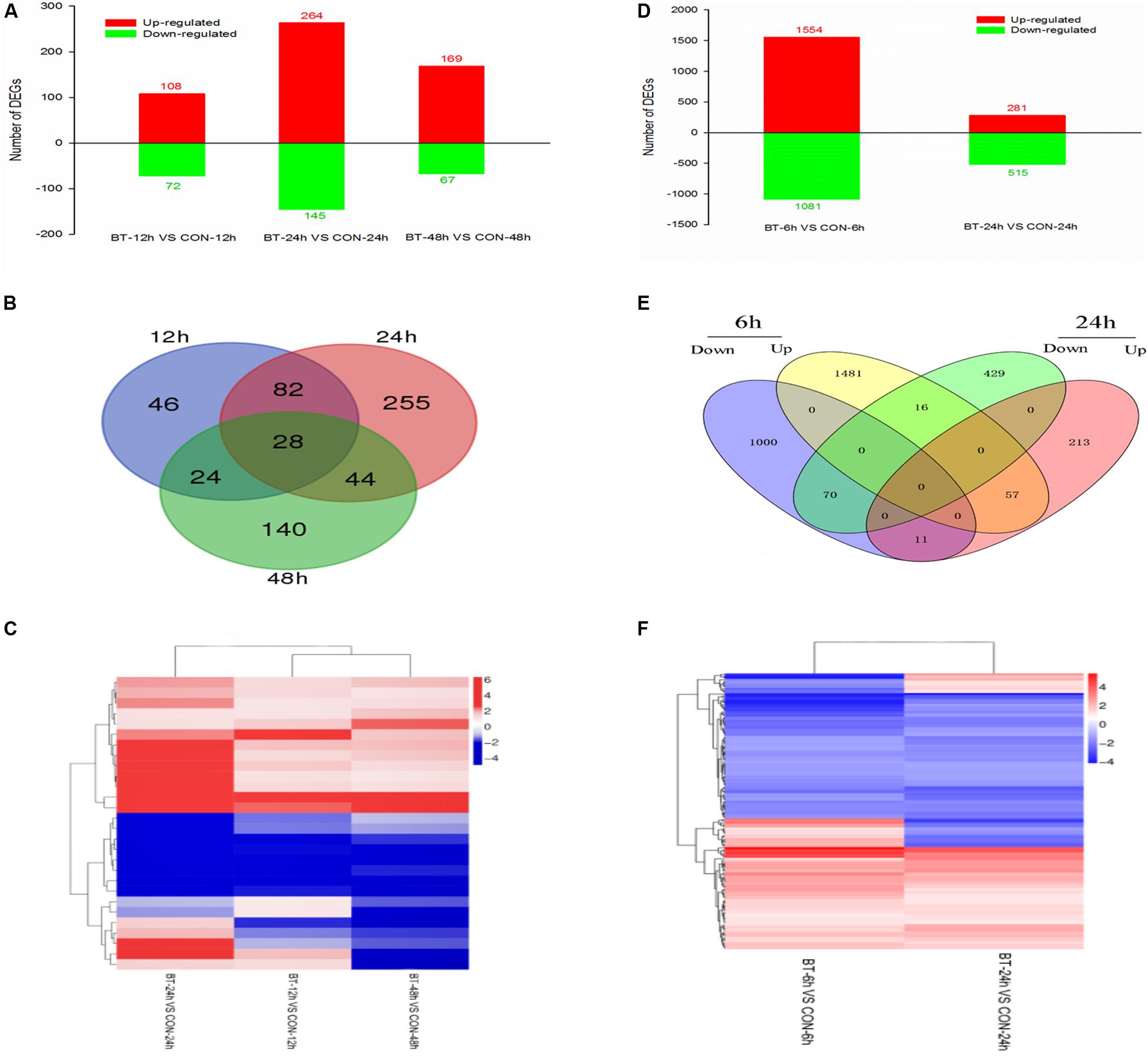

DEGs were screened with the criteria |log2 ratio| ≥ 1 and probability ≥ 0.8 when treated samples were compared to their respective controls (Supplementary Table S3). First, the maximum number of DEGs was observed at 24 h, suggesting that at the mRNA level, 24 h was the most acute time point in the response process (Figure 3A). Comparing the treatment to the control group at 12 h (CON-12 h vs BT-12 h), 180 DEGs were identified in the BT-treated group, with 108 upregulated and 72 downregulated genes; comparing BT-24 h with CON-24 h, 409 DEGs (264 upregulated and 145 downregulated) were generated. At the longest exposure time (CON-48 h vs BT-48 h), the number of DEGs was decreased; of these DEGs, 169 and 67 genes were upregulated and downregulated, respectively (Figure 3A and Supplementary Table S3). The Venn diagram in Figure 3B shows the commonly and differentially expressed DEGs at the three treatment time points. Twenty-eight core sets of DEGs (Figure 3B) were used for clustering analysis (Figure 3C), among which 13 and eight genes were consistently upregulated and downregulated during the time series transcriptome profiling, respectively (Supplementary Table S4). These 21 genes were considered important potential target genes associated with BT response in B. cinerea. However, as many of these 28 core DEGs encoded predicted or hypothetical proteins, no process or pathway analysis was performed.

Figure 3. Gene expression profiling of the (A–C) Botrytis cinerea and (D–F) Bradysia odoriphaga transcriptomes. (A,D) Numbers of DEGs in each comparison group. (B,E) Venn diagram showing the shared and specific DEGs (fold change >2) at each time point. (C,F) Heatmap of common DEGs.

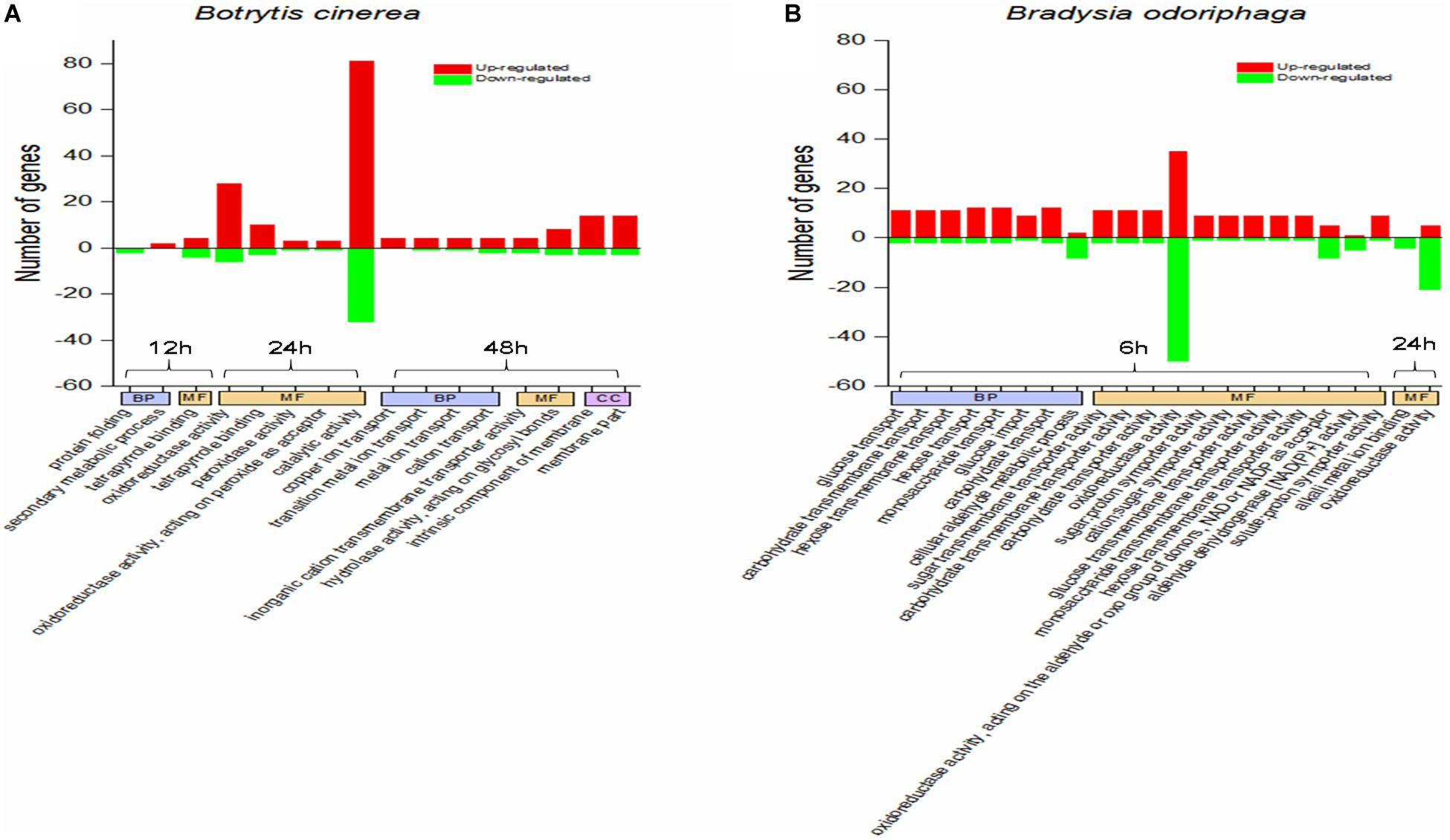

Figure 4A shows the significantly enriched GO terms (corrected P-value < 0.05). In the comparison CON-12 h vs BT-12 h, the DEGs in the biological process (BP) category were enriched in the “protein folding” (downregulated genes) and “secondary metabolic process” (upregulated genes) terms, and the main molecular function (MF) term was “tetrapyrrole binding.” At 24 h, the highly enriched MF terms were “oxidoreductase activity” and “catalytic activity.” At 48 h, obvious morphological changes had occurred, and the DEGs were mostly enriched in BP terms related to ion transport, such as “copper ion transport,” “transition metal ion transport,” “metal ion transport” and “cation transport,” The significant MF terms were “inorganic cation transmembrane transporter activity” and “hydrolase activity, acting on glycosyl bonds,”

Figure 4. GO term enrichment analysis for the DEGs in panels (A) Botrytis cinerea and (B) Bradysia odoriphaga. GO categories are functionally classified into biological process (BP), molecular function (MF), and cellular component (CC). The GO terms in the same category at the same time point are arranged from left to right in ascending order of P-values.

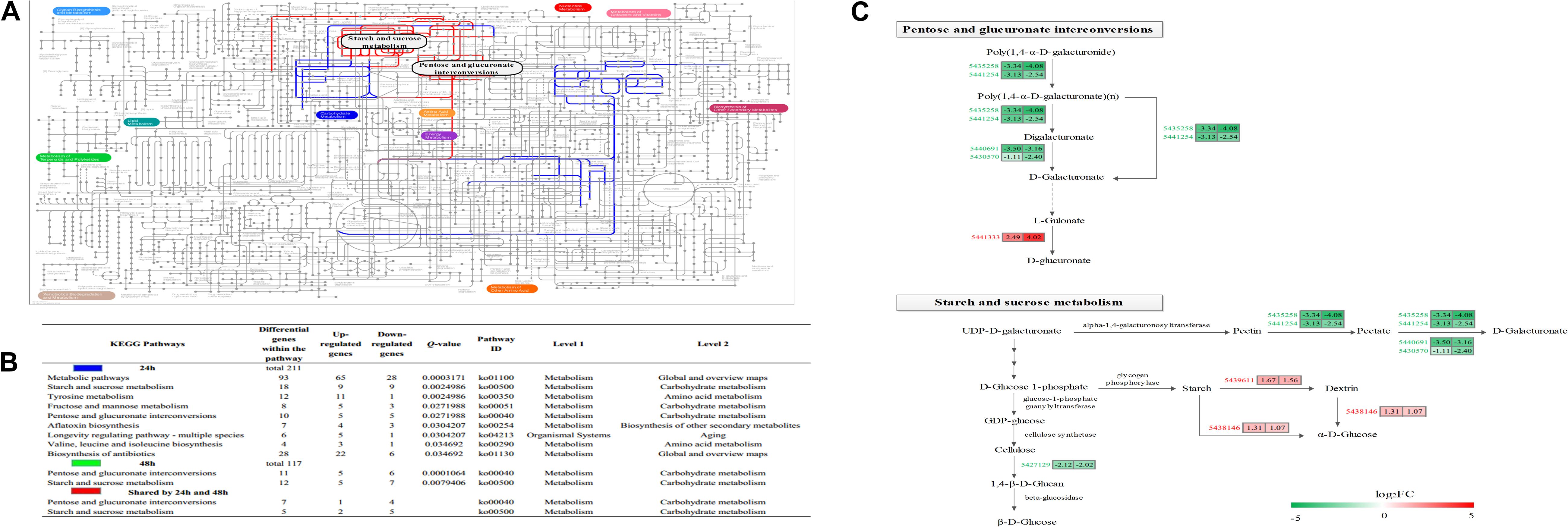

The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis results showed that 0, 9 and 2 pathways were significantly enriched at 12, 24, and 48 h, respectively (Figure 5B), while two pathways (pentose and glucuronate interconversions, starch and sucrose metabolism) were enriched at both 24 and 48 h (Figures 5A,B). There were eight common genes in the shared pathways, and the expression abundance of these genes is shown in Figure 5C and Supplementary Table S5. Interestingly, two polygalacturonases (Bcpgx1, Bcpg1) and two pectin methylesterases (PMEs; Bcpme1, Bcpme2) belonged to both the “pentose and glucuronate interconversions” and “starch and sucrose metabolism” pathways; these genes participated in pectin degradation and were downregulated in the treatment group.

Figure 5. Characterization of the Botrytis cinerea transcriptome. (A) Projection of the Botrytis cinerea transcriptome on the KEGG pathways using iPath (Letunic et al., 2008). Significant pathways at 24 and 48 h are shown in blue and green, respectively. Red lines correspond to shared pathways at 24 and 48 h. Note: Green lines are covered by red lines. (B) Detailed information about the KEGG enrichment analysis of the DEGs. (C) Abundance patterns of the genes participating in the shared pathways. Annotations of the genes are available in Supplementary Table S5.

As shown in Figure 6A, BT could stimulate B. cinerea to produce black pigment, and the DHN melanin synthesis inhibitor tricyclazole induced orange pigment production in the fungi, indicating that the black pigment was melanin. Melanin in fungi is considered protective and plays a role in fungal pathogenesis; however, we found that even with the increase in melanin, B. cinerea was less virulent after BT treatment (Figure 6B). Moreover, the addition of tricyclazole decreased the lesion growth of B. cinerea (Figures 6B,C). Based on the RT-qPCR results, we verified that the expression of melanin synthesis-related genes was increased (Figure 6D).

Figure 6. Analysis of the effect of benzothiazole on melanin production in Botrytis cinerea. (A) Melanin biosynthesis of Botrytis cinerea with or without exposure to benzothiazole and tricyclazole (a fungal dihydroxynaphthalene melanin biosynthesis inhibitor) observed from the front (A-1) and back (A-2) of the petri dishes. (B) Virulence variation resulting from different extents of melanin biosynthesis inhibition. (C) Lesion growth diameters on the cucumber leaves from panel (B). (D) Relative expression levels of melanin biosynthesis-related genes in Botrytis cinerea after fumigation with benzothiazole. The asterisk indicates a significant difference from the respective control.

As B. odoriphaga does not have a reference genome, the B. odoriphaga transcriptome was sequenced with the Illumina HiSeq platform, and de novo assembly was performed. Four libraries from 4th instar larvae of B. odoriphaga with or without BT treatment were sequenced. The Q20 (error probability of 0.01) of the clean reads for each sample was higher than 98% (Supplementary Table S6). After the de novo assembly, a total of 63,046 unigenes were generated, with a total length of 76,377,590 bp, a mean length of 1,211 bp, an N50 length of 2,091 bp, and a GC content of 37.69% (Supplementary Table S6). The raw sequencing data were deposited in the NCBI SRA database under the accession number SRP174932.

A total of 63,046 unigenes were annotated against seven public databases with an E-value cutoff of 10–5. As shown in Supplementary Table S7, 35,945 unigenes (57.01%) were annotated in at least one of the Nr, Nt, Swiss-Prot, COG, InterPro, KEGG, and GO databases. The number of unigenes annotated in specific or shared databases is presented in Supplementary Figure S1, which shows that 12,631 unigenes were annotated in all five main databases (NR, InterPro, Swiss-Prot, COG, and KEGG). The Nr database (52.68%) showed the highest sequence similarity (Supplementary Table S7). Based on the Nr annotations, the homologous species distribution is shown in Supplementary Figure S2. The sequences of B. odoriphaga were highly similar to the sequences of Aedes aegypti (10.34%), Aedes albopictus (7.39%), Culex quinquefasciatus (6.50%), Anopheles gambiae str. PEST (4.14%), Anopheles sinensis (3.40%) and Anopheles darlingi (2.63%).

Constitutive differential expression (| log2(fold change) | ≥ 1, adjusted P-value ≤ 0.05) was apparent between the BT and CON groups; 1,554 upregulated and 1,081 downregulated unigenes were identified at 6 h, and 281 upregulated and 515 downregulated unigenes were identified at 24 h (Figure 3D and Supplementary Table S8). Similar to the B. cinerea transcriptome results, a higher number of upregulated genes was detected. A total of 154 unigenes were shared by the 6 and 24 h-treatment groups, with 57 and 70 unigenes commonly upregulated and downregulated, respectively, at both time points (Figure 3E). The intersection heatmap of 154 DEGs is shown in Figure 3F.

It was obvious that BT fumigation for 6 h mainly activated BP terms associated with carbohydrate transport, including glucose transport, carbohydrate transmembrane transport, hexose transmembrane transport, hexose transport, monosaccharide transport, glucose import, and carbohydrate transport. As the duration increased to 24 h, the DEGs involved in the MF terms alkali metal ion binding and oxidoreductase activity were mainly downregulated (Figure 4B).

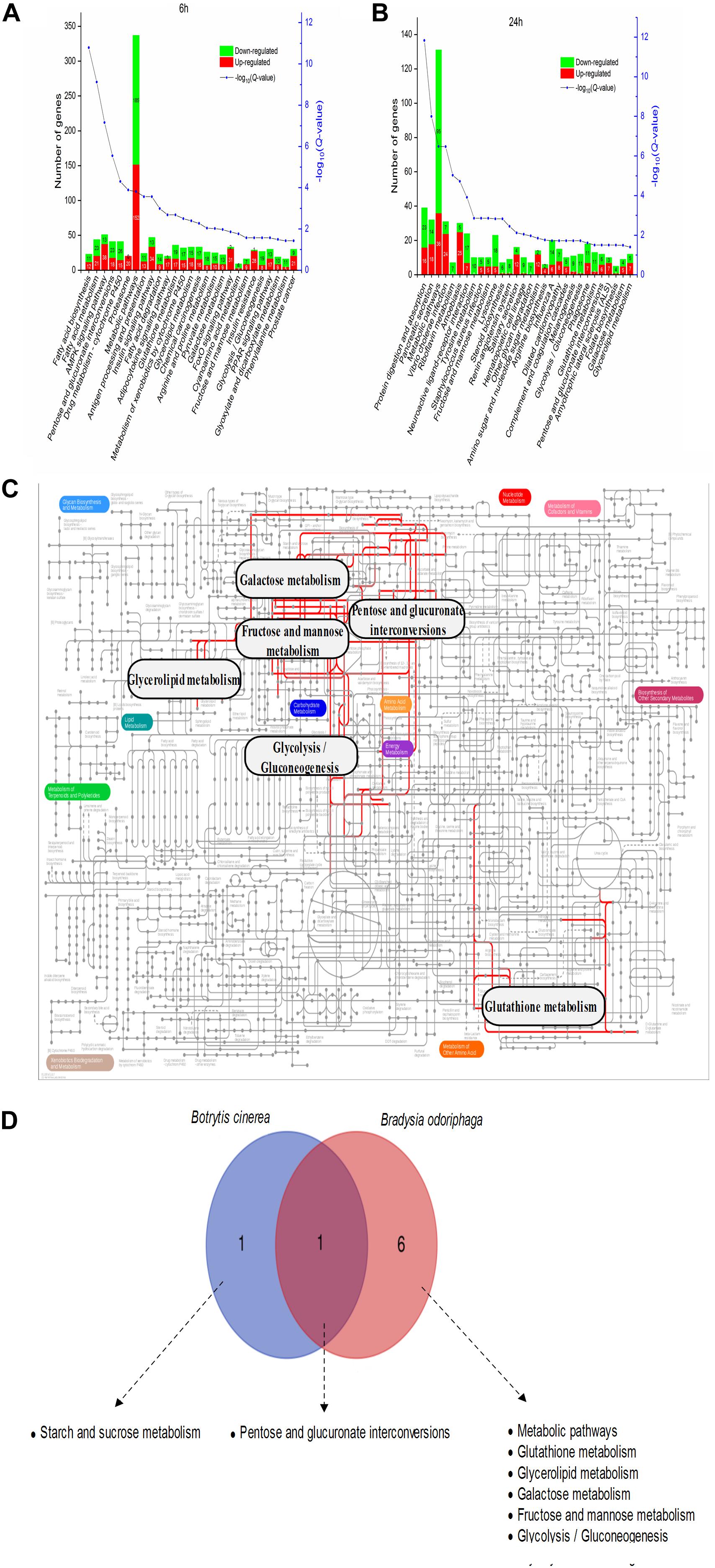

As shown in Figure 7A and Supplementary Table S9, 6 h of BT treatment activated many pathways involved in signal transduction and the endocrine system, including the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathway (51 DEGs; 38 upregulated, 13 downregulated), insulin signaling pathway (47; 34, 13), adipocytokine signaling pathway (20; 17, 3), Forkhead box class O (FoxO) signaling pathway (33; 31, 2), and (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor) PPAR signaling pathway (30; 17, 13). Notably, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) is a core gene participating in all five of these signaling pathways (Supplementary Figure S3). The six most enriched pathways were “metabolic pathways” (337 DEGs), “AMPK signaling pathway” (51), “insulin signaling pathway” (47), “fatty acid metabolism” (44), “pentose and glucuronate interconversions” (41), and “drug metabolism – cytochrome P450” (41). After a longer fumigation of 24 h, most of the DEGs were enriched in “metabolic pathways,” “protein digestion and absorption” and “pancreatic secretion” (Figure 7B). It was obvious that “glycolysis/gluconeogenesis,” “glutathione metabolism,” “tyrosine metabolism” and “melanogenesis” were mostly associated with downregulated proteins. In addition, the salivary secretion of B. odoriphaga was increased. From the genes participating in each KEGG pathway (Supplementary Table S9), we can see that the associated digestive enzymes, including trypsin, chymotrypsin, carboxypeptidase and α-amylase, were significantly altered. It is worth noting that there were 5 upregulated and 11 downregulated genes encoding trypsin, and these genes comprised a large proportion of the DEGs belonging to the pathways “protein digestion and absorption” (16 out of 39), “pancreatic secretion” (16 out of 32), “neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction” (16 out of 24) and “influenza A” (16 out of 30). In addition, 8 aminopeptidase N (APN) genes participating in the “glutathione metabolism” pathway (8 out of 13) were downregulated. Seven downregulated genes encoding tyrosinase represented a large proportion of the DEGs belonging to the pathways “tyrosine metabolism” (7 out of 10) and “melanogenesis” (7 out of 11).

Figure 7. Metabolic pathway analysis of the DEGs in Bradysia odoriphaga. (A,B) KEGG enrichment analysis of the DEGs in Bradysia odoriphaga in response to benzothiazole for 6 and 24 h. (C) Projection of the Bradysia odoriphaga transcriptome on the KEGG pathways using iPath (Letunic et al., 2008). The common significantly changed pathways shared in the 6- and 24-h groups are shown with red lines. (D) Shared and different pathways between Botrytis cinerea and Bradysia odoriphaga. A Venn diagram was drawn using the data from Figure 5B (common pathways shared at 24 and 48 h in Botrytis cinerea) and Figure 7B (common pathways shared at 6 and 24 h in Bradysia odoriphaga).

Seven pathways were enriched at both 6 and 24 h: “pentose and glucuronate interconversions,” “metabolic pathways,” “glutathione metabolism,” “glycerolipid metabolism,” “galactose metabolism,” “fructose and mannose metabolism,” and “glycolysis/gluconeogenesis” (Figure 7C).

“Pentose and glucuronate interconversions” were significantly enriched in both the B. cinerea and B. odoriphaga transcriptomes (Figure 7D).

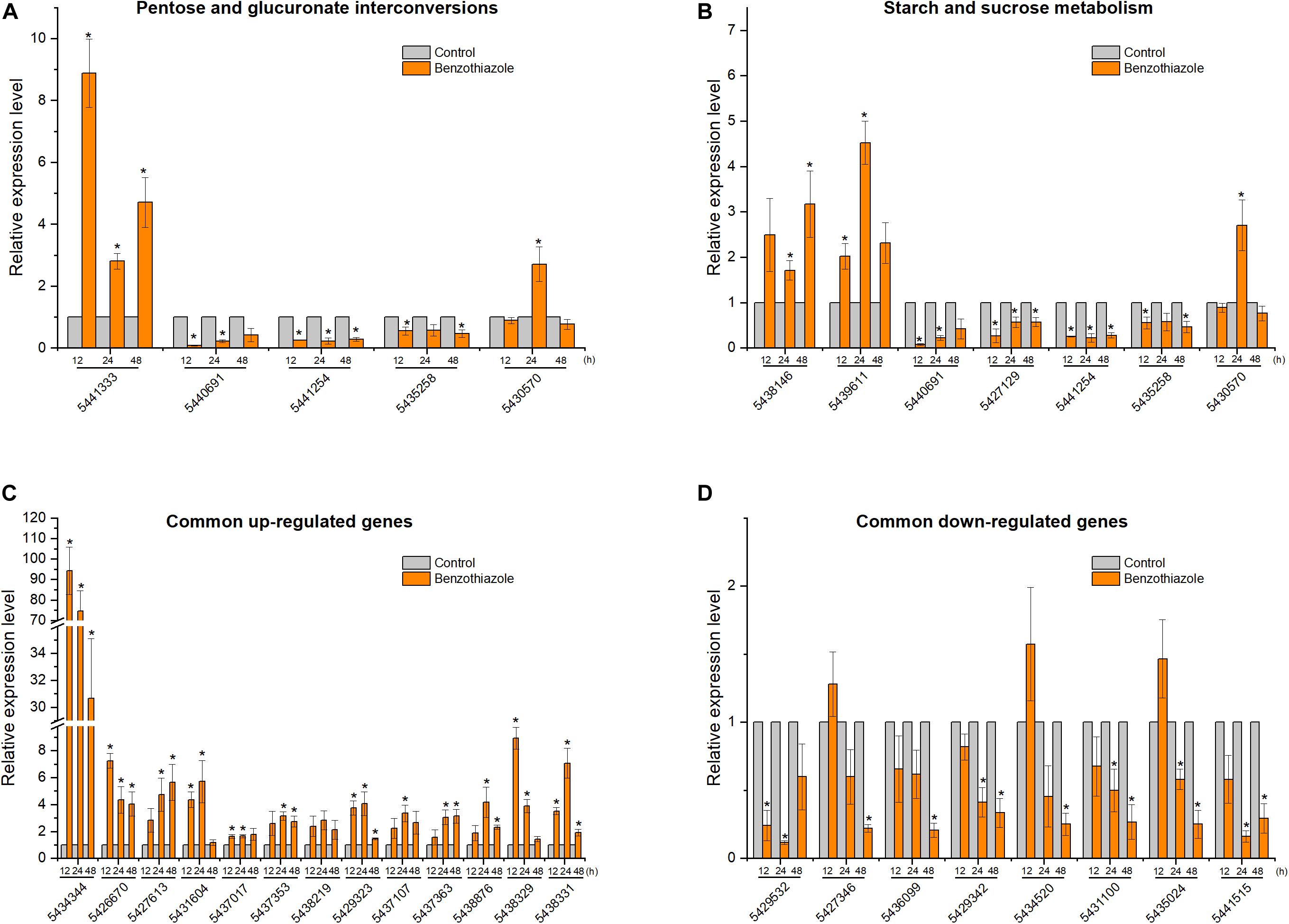

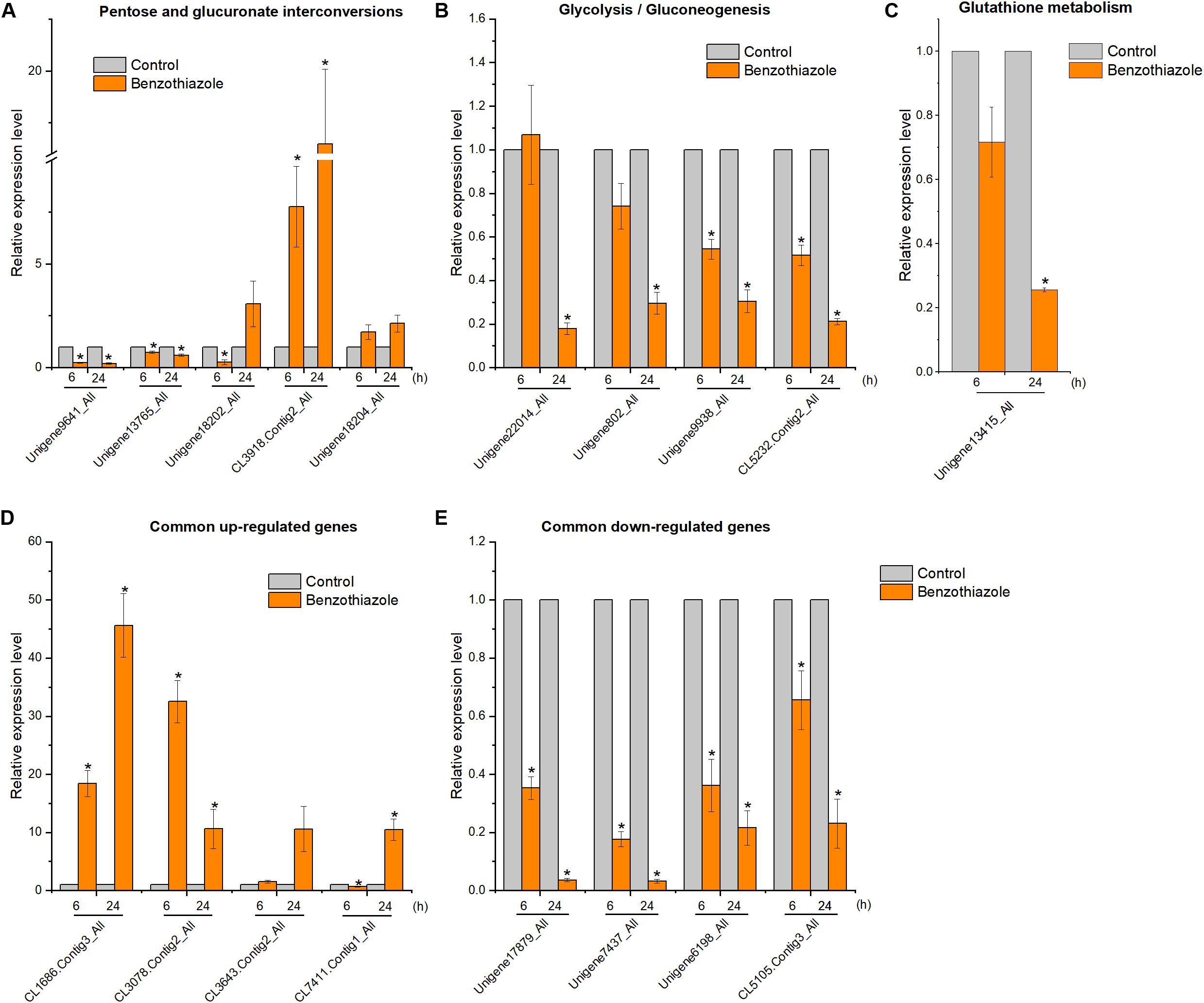

After BT treatment, 36 and 18 genes (Supplementary Table S1) for B. cinerea and B. odoriphaga, respectively, were chosen for RT-qPCR validation. Although the exact fold change ratio for the expression of each gene between the RT-qPCR and RNA-seq data was different, they showed consistent trends (Figures 8, 9). This result suggested that the RNA-seq and RT-qPCR results presented high consistency.

Figure 8. Relative expression levels of selected DEGs in Botrytis cinerea by RT-qPCR. (A) Expression of genes participating in the pentose and glucuronate interconversions pathway. (B) Expression of genes participating in the starch and sucrose metabolism pathway. (C,D) Expression of 13 common upregulated and 8 common downregulated genes at the three time points (12, 24, and 48 h). β-tubulin was used as an internal control gene for normalization. The asterisk indicates a significant difference from the respective control.

Figure 9. Relative expression levels of selected DEGs in Bradysia odoriphaga by RT-qPCR. (A) Expression profiles of genes related to the pentose and glucuronate interconversions pathway. (B) Expression profiles of genes related to the glycolysis/gluconeogenesis pathway. (C) Expression profiles of genes related to the glutathione metabolism pathway. (D,E) Expression profiles of 4 common upregulated and 4 downregulated DEGs at 6 and 24 h. Ribosomal protein S15 (RPS15) was used as an internal control gene for normalization. The asterisk indicates a significant difference from the respective control.

At the ultrastructural level, increased cell wall thickness was the most significant change caused by BT, and this change presented a concentration-responsive profile. The cell wall is the first protective barrier of B. cinerea, and this increase in cell wall thickness may be a defense response. DHN melanin is a crucial component of the extracellular matrix of B. cinerea (Zhang et al., 2015), and melanin granules are localized to the cell wall (Eisenman and Casadevall, 2012). Benzothiazole increased melanin biosynthesis, and it can reasonably be speculated that this increase in melanin synthesis may play a role in the thickening of the cell wall. However, this hypothesis requires further in-depth verification of whether there is an inevitable connection between these two processes. We have shown that inhibition of melanin attenuates B. cinerea infection, proving the importance of melanin in B. cinerea infection. Interestingly, the accumulation of melanin did not necessarily increase virulence. It has been reported that genes related to melanin synthesis, such as Bcpks13, Bcbrn1 and Bcscd1, participate in the melanization of B. cinerea but negatively regulate its virulence (Zhang et al., 2015). Therefore, we investigated seven melanin-related genes (including Bcpks13, Bcbrn1 and Bcscd1) to verify their expression levels, and the RT-qPCR results showed that these genes showed a trend toward increased expression. In addition, copper plays an important role in melanin production, likely because copper works as a required cofactor for melanin biosynthetic enzymes (Eisenman and Casadevall, 2012). Consistent with this role of copper, in the RNA-seq analysis of B. cinerea, we found that the copper ion transporter process was significantly different in the 48 h fumigation group. All the results showed that BT led to melanin accumulation at both the phenotype and transcript levels but negatively regulated the virulence of B. cinerea. Melanin is multifunctional and can improve fungal survival ability under a wide range of environmental stresses (Toledo et al., 2017). Considering that melanin accumulation in the fungal cell wall can prevent solute efflux (Liu et al., 2016), it is reasonable to speculate that melanin could avoid or reduce nutrient leakage in B. cinerea. In that case, however, why did the increase in melanin inhibit the growth and virulence of B. cinerea? We speculate that the production of melanin, a secondary metabolite, consumes many metabolic resources, thereby interfering with other normal cellular growth and development processes.

The eight commonly downregulated genes were all hypothetical or predicted genes, which made understanding their functions challenging. Nevertheless, among them, two genes (GeneID: 5,427,346 and 5,435,024) had descriptions in the KEGG database and conserved domain descriptions on NCBI, which helped us to predict their functions in response to the chemical compound BT. The hypothetical protein BC1G_14644 (5,427,346) has a conserved domain of the SIR2 superfamily of proteins, which includes silent information regulator 2 (Sir2) enzymes1. Sir2 proteins (sirtuins) act as NAD+-dependent deacetylases in all eukaryotes; with NAD+ as a cofactor, they catalyze the conversion of acetylated lysine to deacetylated lysine, nicotinamide and 2’-O-acetyl-ADP-ribose (OAADPr) (Smith and Denu, 2006). Silent information regulator 2 NAD+-dependent protein deacetylases display a variety of physiological functions, such as transcriptional silencing (Gasser and Cockell, 2001; Rusche et al., 2003), apoptosis (Luo et al., 2001), mitosis (Dryden et al., 2003), fatty acid metabolism (Starai et al., 2002), and lifespan extension (Tissenbaum and Guarente, 2001; Rogina and Helfand, 2004). Thus, the observed decrease in BC1G_14644 transcription suggested a disruption of the above cellular processes and a shortened lifespan in B. cinerea. Another hypothetical protein, BC1G_07058 (5,435,024), contains a conserved domain of glycosyl hydrolase family 71, which is a family of α-1,3-glucanases. Fungal α-1,3-glucanases attack the plant cell wall by hydrolyzing α-1,3-glucan, and the observed decrease in α-1,3-glucanase suggested weakened virulence after BT treatment, consistent with the result seen in Figure 6B.

Among the commonly increased genes, the gene 5,434,344 (ATP-binding cassette, subfamily G, member 2, SNQ2) showed the highest expression during exposure to BT, and it was the only ABC transporter gene detected in our study. It is well known that ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 2 (ABCG2) proteins can act on a broad array of xenobiotic compounds as substrates (Kusuhara and Sugiyama, 2007), and the ABC transporter plays an important role in the energy-dependent efflux of fungicides in fungi (Andrade et al., 2000; Hayashi et al., 2001). The rapid and high increase in the expression of this ABC transporter could decrease the accumulation of BT in B. cinerea. We also identified an increase in cytochrome P450 (gene 5,437,017), which plays an important role in the detoxification and metabolism of xenobiotics and drugs (Mcquarters et al., 2014). The increase in cytochrome P450 transcript level suggested a positive response to 2.5 μL/L BT. Overall, ABCG2 and cytochrome P450 were vital for the survival of B. cinerea under BT stress. Bcbrn1 (1,3,8-naphthalenetriol reductase), which is associated with melanin biosynthesis (Schumacher, 2016), was also increased throughout the experiment, suggesting possible melanization of the mycelia, and the current study has proven this hypothesis. In summary, BT activated the drug efflux, detoxification and secondary metabolite biosynthesis pathways of B. cinerea.

Phosphatidylserine decarboxylase (PSD) is responsible for the synthesis of phosphatidylethanolamine (PtdEtn) by decarboxylation of phosphatidylserine (PtdSer). Phosphatidylserine decarboxylase plays a central role in the phospholipid metabolism of prokaryotes and eukaryotes, and its catalytic product, PtdEtn, is a crucial phospholipid in mitochondria (Voelker, 1997) and plays an important role in full mitochondrial respiratory function (Birner et al., 2001; Gohil et al., 2005). Especially in the absence of fermentable carbon sources (e.g., glucose), the PtdEtn produced by PSD becomes essential (Birner et al., 2001). Thus, the increase in PSD transcription in the current study may suggest that the baseline glucose content of B. cinerea is not enough to support a defense against BT. Similarly, one gene (5,427,613) encoding a sugar transporter showed upregulation at all the exposure time points, suggesting a requirement for sugars as an energy source for B. cinerea. Overall, these results indicated that a larger energy supply was needed for B. cinerea in response to BT.

The current study indicated that BT mainly affected the metabolism of B. cinerea, especially carbohydrate metabolism. “Pentose and glucuronate interconversions” and “starch and sucrose metabolism” were potential targeted pathways in B. cinerea in response to BT, suggesting that carbohydrate metabolism was required. The most significant differences were the inhibition of pectin degradation and activation of starch decomposition. In the pectin degradation process, four pectinases, including two PMEs (Bcpme1 and Bcpme2) and two polygalacturonases (Bcpgx1 and Bcpg1), which are components of cell-wall-degrading enzymes and important virulence factors (Valette-Collet et al., 2003; Manfredini et al., 2006), were significantly downregulated in B. cinerea. It is known that pectin demethylation by PMEs is helpful for depolymerization by endopolygalacturonases (endoPGs) (Lionetti et al., 2007); thus, it is coincidental that the expression of Bcpme1, Bcpme2, and Bcpgx1 showed the same trend. The inhibition of pectin degradation suggested that BT had a major effect on the utilization of carbohydrate sources in B. cinerea.

AMPK is a metabolic sensor and is usually activated under conditions of reduced intracellular ATP production (low energy) (Mihaylova and Shaw, 2011). It has been reported that mitochondrial inhibitors (e.g., biguanides and resveratrol) and starvation could increase AMP and ADP levels, thereby activating the AMPK signaling pathway (Mihaylova and Shaw, 2011; Garcia and Shaw, 2017). The AMPK signaling pathway plays an important role in increasing glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation (Garcia and Shaw, 2017) and regulating gene transcription (Mihaylova and Shaw, 2011). It is possible that starvation caused by apastia (Zhao et al., 2016a) activated the AMPK signaling pathway, which indicated a lower energy condition and metabolic dysfunction.

The insulin signaling pathway was the second most enriched signaling pathway affected by BT; insulin is a vital metabolic hormone regulating carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in organisms. The majority of DEGs in this pathway were fatty acid synthases (FASs), indicating a dysregulation of fatty acid biosynthesis and metabolism. Other genes, such as insulin receptor (INSR), insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1), 3-phosphoinositide dependent protein kinase-1 (PDPK1), RAC serine/threonine-protein kinase (AKT) and PEPCK, were upregulated to regulate glucose homeostasis. Insulin signaling can influence feeding and locomotion behavior in insects such as Drosophila (Erion and Sehgal, 2013). Our previous study found that B. odoriphaga showed no ingestion or activity when treated with BT for 6 h (Zhao et al., 2016a). However, motivation of foraging is crucial for the survival of the insect, and insulin signaling could probably initiate starvation-induced food acquisition behavior (Zhao and Campos, 2012).

The adipocytokine signaling pathway includes the signaling cascades caused by adipocytokines (TNF-α, leptin and adiponectin), which are pivotal signaling molecules associated with insulin resistance (Borst, 2004; Zhao et al., 2013). In our study, we identified 17 upregulated genes (out of 20 total in this pathway), including IRS1 and tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 11 (SHP2), suggesting increased glucose uptake and decreased insulin resistance (Rung et al., 2009; Ogunyemi et al., 2013). Similarly, in the KEGG enrichment analysis, insulin resistance was significantly changed. Upregulation of PEPCK could promote glucose production, and upregulation of INSR and IRS could stimulate glucose uptake. The GO enrichment analysis also showed that carbohydrate transport, such as glucose transport, was significantly activated when B. odoriphaga was exposed to BT for 6 h. In summary, BT improved glucose uptake and transport in B. odoriphaga, consistent with a previous study of BT derivatives (Pasternak et al., 2014).

FoxO transcription factors are important in regulating responses to many stimuli, such as insect diapause, stress resistance, nutritional adversity and energy homeostasis (Kramer et al., 2003; Cyclase et al., 2009; Poelchau et al., 2011). The activation of the FoxO signaling pathway suggested a positive response by B. odoriphaga involving the regulation of physiological processes. The fifth most changed pathway affected by BT was the PPAR signaling pathway; PPAR acts as a fat sensor to regulate the transcription of fat-metabolizing enzymes. Notably, the AMPK signaling pathway can influence the other four signaling pathways, and FoxO and PPAR can be regulated by the insulin, AMPK and adipocytokine pathways (Suzuki et al., 2007). Overall, these five signaling pathways interact with each other and mainly regulate glucose and lipid metabolism. The activation of these signaling pathways suggested that the energy and nutrient levels in B. odoriphaga fluctuated severely under BT treatment. Previous biochemical results have shown that BT decreases the levels of three nutrient types, proteins, glucose and lipids, in B. odoriphaga (Zhao et al., 2016b). Meanwhile, the Venn diagram shown in Supplementary Figure S3 suggested an important role of PEPCK in the signal transduction of B. odoriphaga in response to BT.

Due to self-protection, B. odoriphaga refused to consume rhizomes exposed to the noxious and odorous compound BT. The above and previous results proved that low energy and glucose levels were present in B. odoriphaga after BT treatment for 6 h (Zhao et al., 2016b). In a state of starvation, insects adapt through risky behaviors, including searching for and consuming food under unfavorable conditions. We found that B. odoriphaga began to ingest the rhizomes at 24 h, thereby inducing alterations in the digestive system, including the “protein digestion and absorption,” “pancreatic secretion” and “salivary secretion” pathways. The associated digestive enzymes, especially trypsin, were greatly affected by BT, possibly leading to nutrient uptake impairment. As proteins are difficult to absorb through the lining of the small intestine, tryptic digestion is an essential component of protein absorption. Therefore, we can conclude that BT functions as a trypsin disrupter, interfering with protein absorption in B. odoriphaga.

In the glutathione metabolism pathway, we also found inhibition of 8 APN genes. In the small intestine, peptides from the hydrolysis of pancreatic and gastric proteases are finally digested with APN; therefore, the inhibition of APN again proved that BT affected protein absorption in B. odoriphaga. In addition, it has been proven that APN is a receptor for the Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin in Spodoptera litura and Helicoverpa armigera (Rajagopal et al., 2002; Sivakumar et al., 2007). Because BT is one of the secondary metabolites of B. subtilis (Liu et al., 2009a), we speculate that APN may be a potential target of BT. However, in the current study, the insect B. odoriphaga was treated with fumigation and not by feeding. Two reasons may explain these results: little BT residue was deposited on the rhizomes that were ingested by B. odoriphaga; there were still several upstream genes that regulated APN. Therefore, further studies are needed to verify this hypothesis, and we will investigate further in the future.

Furthermore, inhibition of tyrosine metabolism and melanogenesis were detected in our study, suggesting an inhibition of melanization in B. odoriphaga. Downregulation of 7 tyrosinase (also known as phenoloxidase, a rate-limiting enzyme for melanin biosynthesis) genes was responsible for the inhibition of the production of melanins, such as eumelanin. Moreover, tyrosinase is important for both developmental and defensive functions in insects, including melanization, sclerotization, wound healing, and parasite encapsulation; thus, tyrosinase inhibitors are being developed as alternative insecticides for controlling insect pests (Kim and Uyama, 2005). Given the vital role of tyrosinase in the immune defense mechanism of insects (Barnes and Siva-Jothy, 2000; Lee et al., 2008), its inhibition may cause decreased immunocompetence. Whether BT functions as a tyrosinase inhibitor still requires investigation.

The “pentose and glucuronate interconversions” pathway was altered in both the fungus B. cinerea and the insect B. odoriphaga, showing that carbohydrate metabolism was connected with the mode of action of BT in both B. cinerea and B. odoriphaga. However, the genes involved were different in the two species. In the insect B. odoriphaga, the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT; EC 2.4.1.17) and aldehyde reductase (AR; EC 1.1.1.21) genes accounted for a large percent of the DEGs participating in this pathway. UGTs are a group of phase II detoxification enzymes, and ARs are important in the accessory pathway of glucose metabolism, the polyol pathway. In contrast, in the fungus B. cinerea, the expression of pectin degradation enzyme genes such as Bcpme1 and Bcpgx1 was obviously decreased. Possible reasons for this difference are that the dose of the treatment was different (EC50 for B. cinerea; LC30 for B. odoriphaga), and the defense mechanisms of different species in response to the same exogenous compound are not necessarily the same. In summary, the most obvious commonality was that BT caused significant alterations in nutrient metabolism in both fungi and insects, and the “pentose and glucuronate interconversions” pathway was changed in both species.

One difference was that BT may act as a melanogenesis disrupter for the insect but as an activator for the fungus. In fungi, the increased melanin biosynthesis may have been based on compensation for other normal growth processes, such as carbohydrate metabolism. This may reflect the fact that an organism exposed to an exogenous compound shifts the balance among its potential physiological processes when energy conflict arises, supporting one process at the expense of another. However, melanogenesis is an immune defense mechanism in insects, and its decrease suggests an unfavorable growth condition in insects, which negatively affects the subsequent developmental process. Overall, when encountering adversity, the principles of resource allocation differ in different species.

The transcriptome profiles of the fungus B. cinerea and the insect pest B. odoriphaga, in response to BT, were compared in the current study. The evidence suggested that BT affected nutrient metabolism, especially carbohydrate transport, in both species, and the “pentose and glucuronate interconversions” pathway was altered in both species. The insect showed a more complicated response, with several signaling pathways and the digestive system functioning together to regulate glucose and lipid homeostasis. PEPCK was the core gene in the signal transduction of B. odoriphaga in response to BT. In addition, we identified several potential insecticidal target genes, such as trypsin, APN, and tyrosinase. Furthermore, BT may act as a melanogenesis disrupter for the insect but as an activator for the fungus. Exploring the specific mechanisms of action of BT is a challenging and complicated process. More studies are needed to evaluate whether a common target exists in different species.

The raw Illumina sequencing reads have been deposited in the NCBI SRA database with the accession numbers SRP174462 for Botrytis cinerea and SRP174932 for Bradysia odoriphaga.

KC, YZ, and FL conceived and designed the study. YZ, JD, and LH carried out the experiments and analyzed the data. KC, BL, and WM assisted with the bioinformatic analysis. KC and FL wrote and revised the manuscript.

This study was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2018MC019).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01043/full#supplementary-material

FIGURE S1 | Venn diagram of functional unigene annotations of the Bradysia odoriphaga transcriptome based on five major public databases (NR, InterPro, Swiss-Prot, COG, and KEGG).

FIGURE S2 | Distribution of the annotated species by BLAST analysis of Bradysia odoriphaga sequences against the Nr database.

FIGURE S3 | Venn diagram of the DEGs in five signaling pathways at 6 h in Bradysia odoriphaga, highlighting core signaling genes.

TABLE S1 | Primers used in the current study for RT-qPCR.

TABLE S2 | Summary of RNA-seq reads mapped to the Botrytis cinerea B05.10 genome.

TABLE S3 | Differentially expressed genes identified in Botrytis cinerea exposed to benzothiazole for 12, 24 and 48 h.

TABLE S4 | The 28 core genes shared by the 12, 24 and 48 h comparison groups (Figure 3B) identified in the Botrytis cinerea transcriptome.

TABLE S5 | Detailed information for the overlapping DEGs involved in the two pathways shared by the 24 and 48 h groups (Figure 5B) in the Botrytis cinerea transcriptome.

TABLE S6 | Summary statistics of the clean reads and assembled unigenes of the Bradysia odoriphaga transcriptome.

TABLE S7 | Annotations of unigenes from seven public databases.

TABLE S8 | Differentially expressed genes identified in Bradysia odoriphaga exposed to benzothiazole for 6 and 24 h.

TABLE S9 | Detailed information for the KEGG enrichment analysis of the DEGs in the Bradysia odoriphaga transcriptome.

ABC, ATP-binding cassette; AKT, RAC serine/threonine-protein kinase; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; APN, aminopeptidase N; AR, aldehyde reductase; Bcbrn1, 1,3,8-naphthalenetriol reductase; BP, biological process; BT, benzothiazole; CC, cellular component; COEs, carboxylesterases; COG, Clusters of Orthologous Groups of proteins; CON, control; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; DHN, dihydroxynaphthalene; endoPGs, endopolygalacturonases; FASs, fatty acid synthases; FoxO, forkhead box class O; FPKM, fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads; GO, Gene Ontology; GSTs, glutathione-S transferases; INSR, insulin receptor; IRS1, insulin receptor substrate 1; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; MF, molecular function; PEPCK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase; NGS, next-generation sequencing; Nr, NCBI non-redundant protein sequences; Nt, NCBI non-redundant nucleotide sequences; OAADPr, 2′-O-acetyl-ADP-ribose; P450s, cytochrome P450s; PDA, Potato dextrose agar; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; PSD, phosphatidylserine decarboxylase; PtdEtn, phosphatidylethanolamine; PtdSer, phosphatidylserine; PDPK1, 3-phosphoinositide dependent protein kinase-1; RPS15, ribosomal protein S15; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription quantitative PCR; SHP2, tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 11; SRA, Sequence Read Archive; Sir2, silent information regulator 2; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; UGT, UDP-glucuronosyltransferase.

Ali, R., and Siddiqui, N. (2013). Biological aspects of emerging benzothiazoles: a short review. J. Chem. 2013, 1–12. doi: 10.1155/2013/345198

Altschul, S., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E., and Lipman, D. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1990.9999

Andrade, A. C., Van Nistelrooy, J. G. M., Peery, R. B., Skatrud, P. L., and De Waard, M. A. (2000). The role of ABC transporters from Aspergillus nidulans in protection against cytotoxic agents and in antibiotic production. Mol. Gen. Genet. 263, 966–977. doi: 10.1007/PL00008697

Ashburner, M., Ball, C. A., Blake, J. A., Botstein, D., Butler, H., Cherry, J. M., et al. (2000). Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556

Barnes, A. I., and Siva-Jothy, M. T. (2000). Density-dependent prophylaxis in the mealworm beetle Tenebrio molitor L. (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae): cuticular melanization is an indicator of investment in immunity. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 267, 177–182. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.0984

Birner, R., Bürgermeister, M., Schneiter, R., and Daum, G. (2001). Roles of phosphatidylethanolamine and of its several biosynthetic pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 997–1007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077380

Borst, S. E. (2004). The role of TNF-alpha in insulin resistance. Endocrine 23, 177–182. doi: 10.1385/endo:23:2-3:177

Chang, P. K., Hua, S. S. T., Sarreal, S. B. L., and Li, R. W. (2015). Suppression of aflatoxin biosynthesis in Aspergillus flavus by 2-phenylethanol is associated with stimulated growth and decreased degradation of branched-chain amino acids. Toxins 7, 3887–3902. doi: 10.3390/toxins7103887

Chen, C. Y., Zhao, Y. H., Li, H., Zhang, P., Mu, W., and Liu, F. (2014). Biological activity of benzothiazole against Bradysia odoriphaga (Dipterap: Sciaridaeo) at different developmental stages. Acta Entomol. Sin. 57, 45–51. doi: 10.16380/j.kcxb.2014.01.012

Conesa, A., Götz, S., Garcíagómez, J. M., Terol, J., Talón, M., and Robles, M. (2005). Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21, 3674–3676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610

Cui, K., Huang, X., He, L., Zhai, Y., Mu, W., and Liu, F. (2017). The inhibition effect of microbial volatile compound benzothiazole on Botrytis cinerea. Sci. Agric. Sin. 50, 3714–3722. doi: 10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2017.19.008

Cyclase, A., Mattila, J., Bremer, A., Ahonen, L., Kostiainen, R., and Puig, O. (2009). Drosophila FoxO regulates organism size and stress resistance through an denylate cyclase. Mol Cell Biol. 29, 5357–5365. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00302-09

Dean, R., Van Kan, J. A. L., Pretorius, Z. A., Hammond-Kosack, K. E., Di Pietro, A., Spanu, P. D., et al. (2012). The top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13, 414–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00783.x

Dryden, S. C., Nahhas, F. A., Nowak, J. E., Goustin, A., and Tainsky, M. A. (2003). Role for human SIRT2 NAD-dependent deacetylase activity in control of mitotic exit in the cell cycle. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 3173–3185. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.9.3173

Eisenman, H. C., and Casadevall, A. (2012). Synthesis and assembly of fungal melanin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 93, 931–940. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3777-2

Erion, R., and Sehgal, A. (2013). Regulation of insect behavior via the insulin-signaling pathway. Front. Physiol. 4:353. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00353

Ferrandino, A., Carlomagno, A., Baldassarre, S., and Schubert, A. (2012). Varietal and pre-fermentative volatiles during ripening of Vitis vinifera cv Nebbiolo berries from three growing areas. Food Chem. 135, 2340–2349. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.06.061

Garcia, D., and Shaw, R. J. (2017). Review AMPK: mechanisms of cellular energy sensing and restoration of metabolic balance. Mol. Cell 66, 789–800. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.05.032

Gasser, S. M., and Cockell, M. M. (2001). The molecular biology of the SIR proteins. Gene 279, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00741-7

Gohil, V. M., Thompson, M. N., and Greenberg, M. L. (2005). Synthetic lethal interaction of the mitochondrial phosphatidylethanolamine and cardiolipin biosynthetic pathways in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 35410–35416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505478200

Grabherr, M. G., Haas, B. J., Yassour, M., Levin, J. Z., Thompson, D. A., Amit, I., et al. (2011). Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883

Hayashi, K., Schoonbeek, H. J., Sugiura, H., and De Waard, M. A. (2001). Multidrug resistance in Botrytis cinerea associated with decreased accumulation of the azole fungicide oxpoconazole and increased transcription of the ABC transporter gene BcatrD. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 70, 168–179. doi: 10.1006/pest.2001.2548

Kanehisa, M., and Goto, S. (2000). KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27

Keri, R. S., Patil, M. R., Patil, S. A., and Budagupi, S. (2015). A comprehensive review in current developments of benzothiazole-based molecules in medicinal chemistry. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 89, 207–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.10.059

Kim, D., Langmead, B., and Salzberg, S. L. (2015). HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317

Kim, Y. J., and Uyama, H. (2005). Tyrosinase inhibitors from natural and synthetic sources: structure, inhibition mechanism and perspective for the future. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62, 1707–1723. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5054-y

Kramer, J. M., Davidge, J. T., Lockyer, J. M., and Staveley, B. E. (2003). Expression of Drosophila FOXO regulates growth and can phenocopy starvation. BMC Dev. Biol. 3:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-3-5

Kusuhara, H., and Sugiyama, Y. (2007). ATP-binding cassette, subfamily G (ABCG family). Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 453, 735–744. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0134-x

Langmead, B., and Salzberg, S. L. (2012). Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923

Lee, K. P., Simpson, S. J., and Wilson, K. (2008). Dietary protein-quality influences melanization and immune function in an insect. Funct. Ecol. 22, 1052–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2008.01459.x

Letunic, I., Yamada, T., Kanehisa, M., and Bork, P. (2008). iPath: interactive exploration of biochemical pathways and networks. Trends Biochem. Sci. 33, 101–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.01.001

Li, B., and Dewey, C. N. (2011). RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323

Lionetti, V., Raiola, A., Camardella, L., Giovane, A., Obel, N., Pauly, M., et al. (2007). Overexpression of pectin methylesterase inhibitors in Arabidopsis restricts fungal infection by Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol. 143, 1871–1880. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.090803

Liu, W. W., Jing, J. I., Chao, W., Wei, M. U., and Feng, L. (2009a). Evaluation and identification of the potential nematicidal volatiles produced by Bacillus subtilis. Acta Phytopathol. Sin. 8, 855–864. doi: 10.1109/TASE.2011.2160537

Liu, W. W., Zhao, L. J., Wang, C., Wei, M., and Feng, L. (2009b). Bioactive evaluation and application of antifungal volatiles generated by five soil bacteria. Acta Phytophylacica Sin. 36, 97–105.

Liu, X. H., Xu, F., Snyder, J. H., Shi, H. B., Lu, J. P., and Lin, F. C. (2016). Autophagy in plant pathogenic fungi. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 57, 128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.03.022

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Love, M. I., Huber, W., and Anders, S. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8

Luo, J., Nikolaev, A. Y., Imai, S., Chen, D., Su, F., Shiloh, A., et al. (2001). Negative control of p53 by Sir2α promotes cell survival under stress. Cell 107, 137–148. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00524-4

Lv, C., Wang, P., Ma, L., Zheng, M., Liu, Y., and Xing, F. (2018). Large-scale comparative analysis of eugenol-induced/repressed genes expression in Aspergillus flavus using RNA-seq. Front. Microbiol. 9:1116. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01116

Manfredini, C., Sicilia, F., Ferrari, S., Pontiggia, D., Salvi, G., Caprari, C., et al. (2006). Polygalacturonase-inhibiting protein 2 of Phaseolus vulgaris inhibits BcPG1, a polygalacturonase of Botrytis cinerea important for pathogenicity, and protects transgenic plants from infection. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 67, 108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2005.10.002

Mcquarters, A. B., Wolf, M. W., Hunt, A. P., and Lehnert, N. (2014). 1958-2014: after 56 years of research, cytochrome p450 reactivity is finally explained. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 53, 4750–4752. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402404

Mei, Z. X., Wu, Q. J., Zhang, Y. J., and Hua, L. (2003). The biology, ecology and management of Bradysia odoriphaga. Entomol. Knowl. 40, 396–398.

Mihaylova, M. M., and Shaw, R. J. (2011). The AMPK signalling pathway coordinates cell growth, autophagy and metabolism. Nat. Publ. Gr. 13, 1016–1023. doi: 10.1038/ncb2329

Ogunyemi, D., Xu, J., Mahesan, A. M., Rad, S., Kim, E., Yano, J., et al. (2013). Differentially expressed genes in adipocytokine signaling pathway of adipose tissue in pregnancy. J. diabetes Mellit. 3, 86–95. doi: 10.4236/jdm.2013.32013

Pasternak, L., Meltzer-Mats, E., Babai-Shani, G., Cohen, G., Viskind, O., Eckel, J., et al. (2014). Benzothiazole derivatives augment glucose uptake in skeletal muscle cells and stimulate insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells via AMPK activation. Chem. Commun. 50, 11222–11225. doi: 10.1039/c4cc03310h

Pertea, G., Huang, X., Liang, F., Antonescu, V., Sultana, R., Karamycheva, S., et al. (2003). TIGR Gene Indices clustering tools (TGICL): a software system for fast clustering of large EST datasets. Bioinformatics 19, 651–652. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg034

Poelchau, M. F., Reynolds, J. A., Denlinger, D. L., Elsik, C. G., and Armbruster, P. A. (2011). A de novo transcriptome of the Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, to identify candidate transcripts for diapause preparation. BMC Genomics 12:619. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-619

Quevillon, E., Silventoinen, V., Pillai, S., Harte, N., Mulder, N., Apweiler, R., et al. (2005). InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 116–120. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki442

Rajagopal, R., Sivakumar, S., Agrawal, N., Malhotra, P., and Bhatnagar, R. K. (2002). Silencing of midgut aminopeptidase N of Spodoptera litura by double-stranded RNA establishes its role as Bacillus thuringiensis toxin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 46849–46851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200523200

Ren, Y., Jin, J., Zheng, M., Yang, Q., and Xing, F. (2020). Ethanol inhibits aflatoxin B1 biosynthesis in Aspergillus flavus by up-regulating oxidative stress-related genes. Front. Microbiol. 10:2946. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02946

Rogina, B., and Helfand, S. L. (2004). Sir2 mediates longevity in the fly through a pathway related to calorie restriction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 15998–16003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404184101

Rung, J., Cauchi, S., Albrechtsen, A., Shen, L., Rocheleau, G., Cavalcanti-Proença, C., et al. (2009). Genetic variant near IRS1 is associated with type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. Nat. Genet. 41, 1110–1115. doi: 10.1038/ng.443

Rusche, L. N., Kirchmaier, A. L., and Rine, J. (2003). The establishment, inheritance, and function of silenced chromatin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 481–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161547

Schumacher, J. (2016). DHN melanin biosynthesis in the plant pathogenic fungus Botrytis cinerea is based on two developmentally regulated key enzyme (PKS)-encoding genes. Mol. Microbiol. 99, 729–748. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13262

Schuster, S. C. (2008). Next-generation sequencing transforms today’s biology. Nat. Methods 5, 16–18. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1156

Seifert, R. M., and King, A. G. Jr. (1982). Identification of some volatile constituents of Aspergillus clavatus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 30, 786–790. doi: 10.1021/jf00112a044

Shi, C., Yang, F., Zhu, X., Du, E., Yang, Y., Wang, S., et al. (2016). Evaluation of housekeeping genes for quantitative real-time PCR analysis of Bradysia odoriphaga (Diptera: Sciaridae). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17:1034. doi: 10.3390/ijms17071034

Sims, D., Sudbery, I., Ilott, N. E., Heger, A., and Ponting, C. P. (2014). Sequencing depth and coverage: key considerations in genomic analyses. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 121–132. doi: 10.1038/nrg3642

Sivakumar, S., Rajagopal, R., Venkatesh, G. R., Srivastava, A., and Bhatnagar, R. K. (2007). Knockdown of aminopeptidase-N from Helicoverpa armigera larvae and in transfected Sf21 cells by RNA interference reveals its functional interaction with Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal protein Cry1Ac. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 7312–7319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607442200

Smith, B. C., and Denu, J. M. (2006). Sir2 protein deacetylases: evidence for chemical intermediates and functions of a conserved histidine. Biochemistry 45, 272–282. doi: 10.1021/bi052014t

Starai, V. J., Celic, I., Cole, R. N., Boeke, J. D., and Escalantesemerena, J. C. (2002). Sir2-dependent activation of acetyl-CoA synthetase by deacetylation of active lysine. Science 298, 2390–2392. doi: 10.1126/science.1077650

Suzuki, A., Okamoto, S., Lee, S., and Saito, K. (2007). Leptin stimulates fatty acid oxidation and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α gene expression in mouse C2C12 myoblasts by changing the subcellular localization of the α 2 form of AMP-activated protein kinase. Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 4317–4327. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02222-06

Tarazona, S., Garcíaalcalde, F., Dopazo, J., Ferrer, A., and Conesa, A. (2011). Differential expression in RNA-seq: a matter of depth. Genome Res. 21, 2213–2223. doi: 10.1101/gr.124321.111

Tissenbaum, H. A., and Guarente, L. (2001). Increased dosage of a sir-2 gene extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 410, 227–230. doi: 10.1038/35065638

Toledo, A. V., Franco, M. E. E., Yanil Lopez, S. M., Troncozo, M. I., Saparrat, M. C. N., and Balatti, P. A. (2017). Melanins in fungi: types, localization and putative biological roles. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 99, 2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2017.04.004

Valette-Collet, O., Cimerman, A., Reignault, P., Levis, C., and Boccara, M. (2003). Disruption of Botrytis cinerea pectin methylesterase gene Bcpme1 reduces virulence on several host plants. Mol. Plant. Microbe. Interact. 16, 360–367. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.4.360

Voelker, D. R. (1997). Phosphatidylserine decarboxylase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Lipids Lipid Metab. 1348, 236–244. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2760(97)00101-X

Wang, P., Ma, L., Jin, J., Zheng, M., Pan, L., Zhao, Y., et al. (2019). The anti-aflatoxigenic mechanism of cinnamaldehyde in Aspergillus flavus. Sci. Rep. 9:10499. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47003-z

Williamson, B., Tudzynski, B., Tudzynski, P., and Van Kan, J. A. L. (2007). Botrytis cinerea: the cause of grey mould disease. Mol. Plant Pathol. 8, 561–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2007.00417.x

Ye, J., Fang, L., Zheng, H., Zhang, Y., Chen, J., Zhang, Z., et al. (2006). WEGO: a web tool for plotting GO annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 293–297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl031

Zhang, C., He, Y., Zhu, P., Chen, L., Wang, Y., Ni, B., et al. (2015). Loss of bcbrn1 and bcpks13 in Botrytis cinerea not only blocks melanization but also increases vegetative growth and virulence. Mol. Plant. Microbe. Interact. 28, 1091–1101. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-04-15-0085-R

Zhao, L. J., Yang, X. N., Li, X. Y., Mu, W., and Liu, F. (2011). Antifungal, insecticidal and herbicidal properties of volatile components from Paenibacillus polymyxa Strain BMP-11. Agric. Sci. China 10, 728–736. doi: 10.1016/S1671-2927(11)60056-4

Zhao, M., Li, X. M., and Qu, H. (2013). EDdb: a web resource for eating disorder and its application to identify an extended adipocytokine signaling pathway related to eating disorder. Sci. China Life Sci. 56, 1086–1096. doi: 10.1007/s11427-013-4573-2

Zhao, X., Zhi, Q. Q., Li, J. Y., Keller, N. P., and He, Z. M. (2018). The antioxidant gallic acid inhibits aflatoxin formation in Aspergillus flavus by modulating transcription factors Farb and CreA. Toxins 10:270. doi: 10.3390/toxins10070270

Zhao, X. L., and Campos, A. R. (2012). Insulin signalling in mushroom body neurons regulates feeding behaviour in Drosophila larvae. J. Exp. Biol. 215, 2696–2702. doi: 10.1242/jeb.066969

Zhao, Y., Cui, K., Xu, C., Wang, Q., Wang, Y., Zhang, Z., et al. (2016a). Proteomic profile of the Bradysia odoriphaga in response to the microbial secondary metabolite benzothiazole. Sci. Rep. 6:37730. doi: 10.1038/srep37730

Keywords: benzothiazole, Botrytis cinerea, Bradysia odoriphaga, transcriptome, nutrient metabolism, melanogenesis, signaling pathway

Citation: Cui K, Zhao Y, He L, Ding J, Li B, Mu W and Liu F (2020) Comparison of Transcriptome Profiles of the Fungus Botrytis cinerea and Insect Pest Bradysia odoriphaga in Response to Benzothiazole. Front. Microbiol. 11:1043. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01043

Received: 07 February 2020; Accepted: 27 April 2020;

Published: 12 June 2020.

Edited by:

Raffaella Balestrini, Institute for Sustainable Plant Protection (CNR), ItalyReviewed by:

Zheng Wang, Yale University, United StatesCopyright © 2020 Cui, Zhao, He, Ding, Li, Mu and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Feng Liu, ZmxpdUBzZGF1LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.